Abstract

We report the case of an 80 year-old woman who developed bilateral lower extremity purpura and renal impairment with proteinuria a few days after a transient fever (day 0). High levels of both anti-streptolysin-O antibody (ASO) and anti-streptokinase antibody (ASK), as well as low levels of coagulation factor XIII in serum were noted. Skin biopsy was performed and showed a leukocytoclastic vasculitis with deposition of IgA and C3 in the cutaneous small vessels, indicating IgA vasculitis in the skin. After initiation of oral prednisolone, the skin lesions showed significant improvement. However, renal function and proteinuria gradually worsened from day 12. Kidney biopsy was performed on day 29, which demonstrated a necrotizing and crescentic glomerulonephritis with mesangial deposition of IgA and C3. In addition, the deposition of galactose-deficient IgA1 (Gd-IgA1) was positive on glomeruli and cutaneous small vessels, indicating that the purpura and glomerulonephritis both shared the same Gd-IgA1-related pathogenesis. In addition, the association between the acute streptococcal infection and the IgA vasculitis was confirmed by the deposition of nephritis-associated plasmin receptor (NAPlr) in glomeruli. The patient was treated with steroid pulse and intravenous cyclophosphamide, in addition to the oral prednisolone treatment. Renal function and proteinuria gradually improved, but did not completely recover, as is typically seen with courses of IgA vasculitis in the elderly. In this case, the streptococcal infectionrelated IgA vasculitis was confirmed pathologically by the deposition of both NAPlr and Gd-IgA1 in glomeruli, as well as Gd-IgA1 in the cutaneous small vessels.

Keywords: Gd-IgA1, IgA vasculitis, NAPlr, Streptococcal infection

Introduction

IgA vasculitis is classified as one of the immune complex types of vasculitis within the category of small vessel vasculitis based on the size of the affected vessels. The clinical manifestations of IgA vasculitis are typically triggered by upper respiratory tract infections and present as palpable purpura, mainly on the lower extremities, accompanied by abdominal pain, arthralgia, and renal involvement. Histologically, IgA vasculitis typically demonstrates a leukocytoclastic vasculitis in skin, as well as a proliferative glomerulonephritis (GN) in the kidney with IgA deposition [1, 2]. Recently, galactose-deficient IgA1 (Gd-IgA1), which is recognized by rat anti-Gd-IgA1 monoclonal antibody, KM55, has been found to be deposited in IgA vasculitis in the skin as well as in the kidney [3]. Though some triggers such as viral or bacterial infections are known to induce abnormal IgA autoimmune reactions in IgA vasculitis patients, streptococcal infection is thought to be one of the major causes of IgA vasculitis. Although the exact relationship between IgA vasculitis with nephritis and streptococcal infection remains unclear [1], 30% of IgA vasculitis patient in childhood were shown to be positive of nephritis-associated plasmin receptor (NAPlr), which is a group A streptococcal antigen, in glomeruli [4].

We report a case of streptococcal infection-associated IgA vasculitis in skin and kidney. Both kidney and skin tissues obtained from this patient with IgA vasculitis were positive for Gd-IgA1 in glomeruli as well as small vessels in the skin. In addition, before purpura and urinary abnormalities developed, transient fever was present, and the causative streptococcal infection was confirmed by positive staining for NAPlr in glomeruli. As far as we know, this case is the first report of utilizing immunofluorescence using both NAPlr and Gd-IgA1, which demonstrated pathologically that a streptococcal infection was directly associated with IgA vasculitis in the skin and kidney.

Case report

The case of an 80 year-old female with notable past medical history including bilateral osteoarthritis, cholecystitis, bronchial asthma (asymptomatic, no inhalers), and Hashimoto’s disease was considered. Her medications included mirtazapine, tramadol, mosapride, and acetaminophen.

The clinical time course is shown in Fig. 1. The patient visited her local doctor because of fever 38 °C, back pain, and general fatigue. Acetaminophen was prescribed, and the fever and back pain were noted to have improved the next day. That evening, however ,the patient developed palpable purpura on both lower legs, and she was referred to the dermatology department of our hospital. The purpura rapidly progressed across her bilateral lower extremities, and she was admitted as the clinical diagnosis of IgA vasculitis. In laboratory findings, a serum IgA concentration was noted to be within normal range. Anti-streptolysin-O antibody (ASO) and anti-streptokinase antibody (ASK) were both elevated (570 IU/ml ASO and 10,240 titer ASK) (Table 1). There was no decrease in complement titer, C3 and C4, which are typically decreased in acute glomerulonephritis after streptococcal infection. Anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) and anti-glomerular basement membrane (GBM) antibody were also negative. D-dimer was high at 90 µg/ml. There was no evidence of pulmonary embolism or deep vein thrombosis on contrast-enhanced CT. Serum coagulation factor XIII activity was low. Laboratory findings also showed elevated serum creatinine (sCr) 1.5 mg/dl, low levels of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR: 27 ml/min/1.73m2), and positive hematuria (2+) and proteinuria (4+), suggesting IgA vasculitis induced nephritis. CRP was 6.3 mg/dl (Fig. 1). In the Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score (BVAS) [5], the BVAS new/worse was 14 points (purpura 2 points, renal 12 points), and BVAS persistent was 0 point. On the day of admission, a skin biopsy was performed from the palpable purpura on the left lower leg.

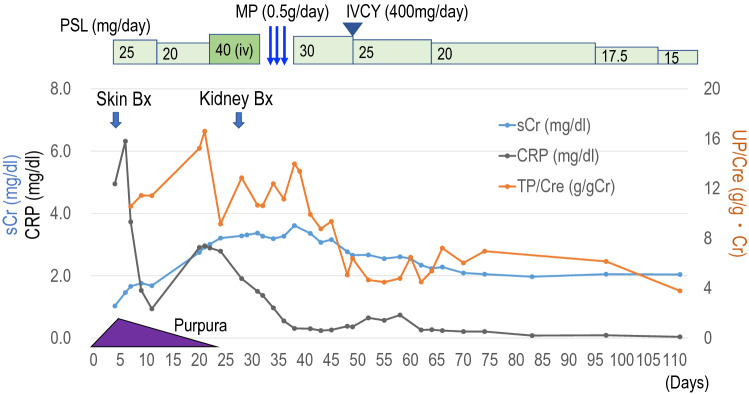

Fig. 1.

The clinical time course. The serum creatinine (sCr, mg/dl: blue line), the serum CRP (mg/dl: black line), and urinary protein (UP/Cre: orange line) were shown. PSL (prednisolone), MP (methyl prednisolone), IVCY (intravenous cyclophosphamide), and UP/Cre (urinary protein/creatinine, g/gCr)

Table 1.

Data at second admission on day 21 for kidney biopsy

| WBC | 9,500/µL | Glucose | 148 mg/dl | Urinalysis | |

| Neut | 93.4% | Hb A1c | 6 % | pH | 5.5 |

| Lymph | 4.1% | CRP | 3 mg/dl | SG | 1.023 |

| RBC | 373 × 104/µL | IgG | 872 mg/dl | Protein | (4+) |

| Hemoglobin | 11.5 g/dl | IgA | 305 mg/dl | TP/Cre | 16.6 g/g Cr |

| Platelet | 17.3 × 104/µL | IgM | 62 mg/dl | Occult blood | (3+) |

| AST | 22 IU/L | IgE | 1518 mg/dl | RBC | 30–49/HPF |

| ALT | 14 IU/L | C3 | 94 mg/dl | Red blood cell cast | (−) |

| LDL-C | 179 mg/dl | C4 | 36 mg/dl | Poikilocyte | (−) |

| TG | 289 mg/dl | C1q | < 1.5 U/ml | NAG | 85.2 U/l |

| TP | 5.1 g/dl | ANA | < 40 titer | β2MG | 252 µg/l |

| Albumin | 2.2 g/dl | PR3-ANCA | < 0.5 IU/ml | ||

| BUN | 64.2 mg/dl | MPO-ANCA | < 0.5 IU/ml | ||

| Cre | 2.9 mg/dl | Anti-GBM Ab | (−) | ※ data on day 6 | |

| Uric acid | 6.9 mg/dl | HBs Ag | (−) | CRP | 6.3 mg/dl |

| Na | 137 mEq/l | HBc Ab | (−) | ASO | 570 IU/ml |

| K | 4.2 mEq/l | HIV | (−) | ASK | 10,240 titer |

| Cl | 107 mEq/l | TPLA | (−) | Coagulation factor XIII activity | |

| Ca | 7.3 mg/dl | 57% (70–140) | |||

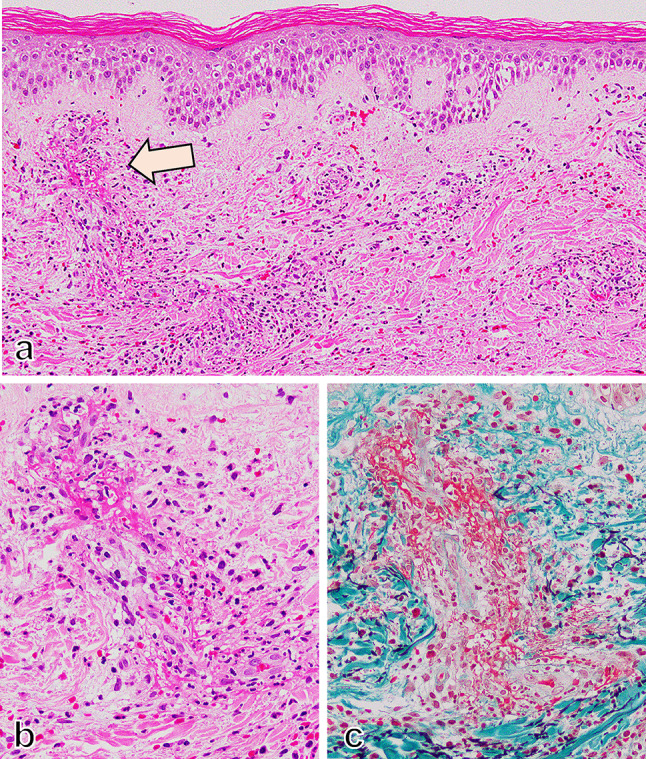

Histological findings showed polymorphonuclear leukocytes and hemorrhage around small blood vessels in the upper dermis, indicating leukocytoclastic vasculitis (Fig. 2). The immunofluorescence using paraffin-embedded specimens showed deposition of IgA and C3 on the small vessels (Fig. 3a, b). In addition, the deposition of Gd-IgA1 which was recognized by rat anti-Gd-IgA1 monoclonal antibody (KM55, Immuno-Biological Laboratories, Fujioka, Japan), was also noted on small vessels in the upper dermis (Fig. 3c–e). After the biopsy, oral prednisolone (PSL) 20 mg/day was started (Fig. 1). The purpura was noted to improve after initiation of oral PSL, and the patient was discharged on hospital day 6. At the time of discharge, the BVAS had been reduced to BVAS new/worse: 6 points (renal), and BVAS persistent: 3 points (purpura 1 point, renal 2 points). 10 days after discharge however, edema developed on both legs, along with declining renal function and increased proteinuria. At the time of readmission, bilateral leg edema was prominent and chest and abdominal CT showed bilateral pleural effusions and ascites. Subjectively, the patient also endorsed new mild dyspnea with exertion. Laboratory findings noted a rising sCr 2.9 mg/dl, serum albumin 2.2 g/dl, urinary protein 6.3 g/day, as well as severe hematuria, indicating acute renal dysfunction and nephrotic syndrome (Table 1). CRP was slightly increased to 3.0 mg/dl. The BVAS showed BVAS new/worse: 10 points (renal), and BVAS persistent: 3 points (renal). Intravenous PSL infusion at a dose of 40 mg/day was started due to malabsorption secondary to diffuse edema caused by the nephrotic syndrome.

Fig. 2.

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis in the skin. Leucocytoclastic vasculitis was developed in small vessels in the upper dermis of the skin (a HE staining, × 200). (b) and (c) are serial sections with HE staining (b × 600) and EMG staining (c × 600) indicated by the arrow in (a), showing infiltration of neutrophils with fine nuclear dusts into the vessel wall and perivascular area and fibrin exudation and hemorrhage

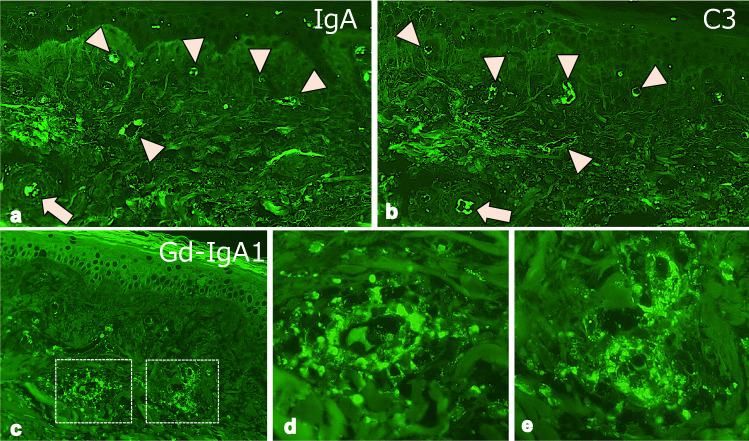

Fig. 3.

Immunofluorescence findings of the skin. Immunofluorescence for IgA, C3, and galactose-deficient IgA1 (Gd-IgA1) was performed using pronase-digested paraffin specimens. The deposition of IgA (a × 200) and C3 (b × 200) were detected on the small vessels (arrowheads) in the dermis. The Gd-IgA1 was immunostained by KM55 antibody (c × 200). (d) (× 600) and (e) (× 600) were the high magnification view of the dotted square in (c). The deposition of Gd-IgA1 was detected on small vessels in the upper dermis

A renal biopsy was performed on day 9 of readmission and 29 days after the original transient fever. Light microscopy revealed a necrotizing lesion in glomeruli with fibrin deposition and surrounding cellular crescent formation, indicating an acutely active glomerular lesion (Fig. 4a, b). PAS staining showed severe segmental mesangial proliferative changes (Fig. 4c). In addition to these findings, endocapillary proliferative changes with infiltration of neutrophils were also seen (Fig. 4d). The immunofluorescence study showed that IgA and C3 were positive in the segmental mesangial region (Fig. 5). The deposition of Gd-IgA1 was also noted in glomeruli (Fig. 5c–e). From the renal biopsy, pathological diagnosis was mesangial and endocapillary proliferative GN and 75% of glomeruli with necrotizing and cellular crescentic lesions, IgA vasculitis (Henoch-Schönlein purpura), International Study of Kidney Disease in Children (ISKDC) grade IV. To clarify the relationship between the streptococcal infection and proliferative GN in the kidney, NAPlr staining was performed using frozen tissue samples and fluorescein-conjugated mouse monoclonal anti-NAPlr antibody (Yamasa Corporattion, Tokyo, Japan), and the deposition of NAPlr was confirmed in the glomeruli (Fig. 5h). Because of these findings, an mPSL pulse (500 mg/day) and intravenous cyclophosphamide (400 mg/day) were started (Fig. 1). After these interventions, CRP was almost completely improved (Fig. 1). The BVAS had been reduced to BVAS new/worse: 0 point, and BVAS persistent: 5 points (renal). Also, sCr, and proteinuria both gradually improved (Fig. 1), although never fully recovered to baseline. The patient has been under outpatient observation for about a year now, and her renal function has remained stable.

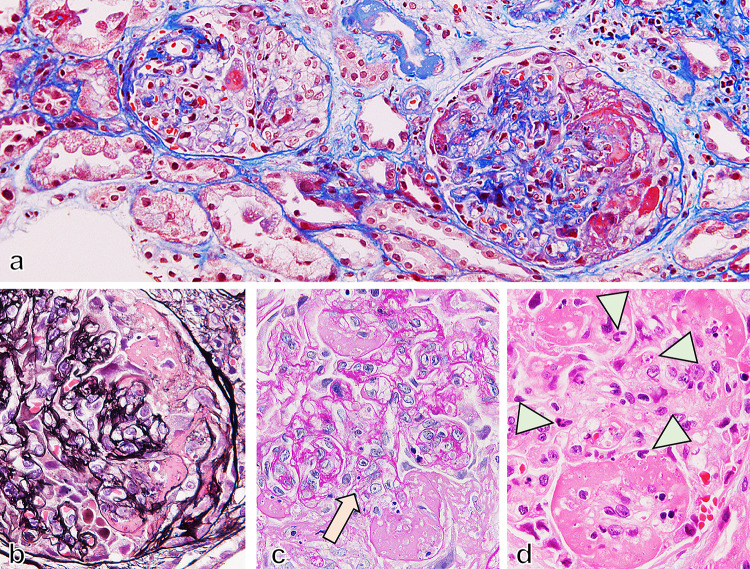

Fig. 4.

Necrotizing and crescentic glomerulonephritis in IgA vasculitis with nephritis. Necrotizing and crescentic lesions developed in glomeruli with fibrin deposition and cellular crescent formation (a Masson staining, × 200). Mesangial proliferation was developed (arrow in b PAM staining, × 600 and arrow in c PAS staining, × 600) with fibrin exudation. In necrotizing glomerular lesion, prominent infiltration of neutrophils (arrowhead in d HE staining, × 600) also developed

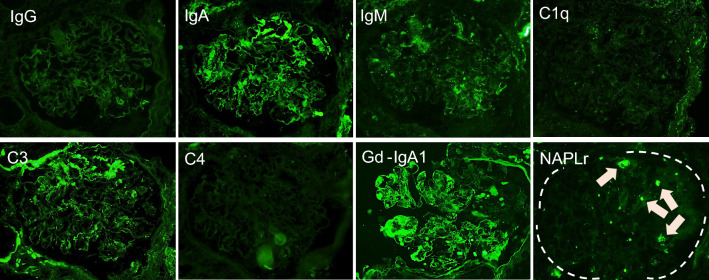

Fig. 5.

Immunofluorescence findings of the kidney. Immunofluorescence findings in frozen specimens of the IgG (a × 400), IgA (b × 400), IgM (c × 400), C1q (d × 400), C3 (e × 400), and C4 (f × 400) showed segmental deposition of IgA and C3 in the mesangial area. The deposition of Gd-IgA1 in paraffin specimens (g × 400) was noted on the mesangial and the glomerular capillary walls. The deposition of NAPlr in glomeruli was detected in frozen specimens (h × 400) that might be positive on infiltrated neutrophils (arrowhead) and mesangial areas (arrow)

Discussion

IgA vasculitis is classified as one of the immune complex types of small vessel vasculitis. The clinical manifestations include palpable purpura mainly on the lower limbs, gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain, vomiting, bloody stool, anemia, joint swelling and pain, as well as acute kidney injury [1]. Bacterial infections such as streptococcus, mycoplasma, and salmonella, as well as viral infections including measles, rubella, varicella, and erythema infectiosum are known to trigger the development of IgA vasculitis [1]. In this case, the patient developed a transient fever followed by palpable purpura on both legs. Subsequent biopsy of these lesions demonstrated an IgA vasculitis. Because of high ASO and ASK levels, it was thought that the preceding streptococcal infection prompted the IgA vasculitis. Although the patient had no overt signs of clinical infection aside from fever, an asymptomatic streptococcal infection is not rare [6]. The histological findings from the renal biopsy in this case showed necrotizing and crescentic GN with mesangial and endocapillary proliferative lesions with IgA and C3 deposits, suggesting IgA vasculitis with nephritis, IgA nephropathy, or IgA dominant infectious GN [7]. It has been known that the pathogenetic bacteria of IgA dominant infectious GN was mainly staphylococcus and gram-negative bacteria in the elderly population, and streptococcal infection is rare [8]. Most recently, a rare case of IgA dominant infectious GN was reported to be double positive for NAPlr and Gd-IgA1 in glomeruli [9].

To investigate whether the streptococcal infection is related to this GN, IF staining with anti-NAPlr antibody was performed, and it was confirmed to be positive in glomeruli. The NAPlr is the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) of group A streptococcus and well known as a specific marker of acute GN after streptococcal infection (APSGN). All of the tissue from renal biopsies of APSGN patients 2 weeks after onset of symptoms showed deposition of NAPlr [10]. As the nephritogenic antigens responsible for APSGN, NAPlr and streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin B (SPEB) are well known. It was reported that double staining of NAPlr and SPEB showed a similar distribution in the glomeruli of APSGN [11]. GAPDH of streptococcus, NAPlr, can trap plasmin by functioning as a plasmin receptor and cause APSGN [11], and it was reported that the distribution of NAPlr deposits coincided with the distribution of plasmin activity [12]. Oda et al. found that NAPlr glomerular deposition are also seen in other glomerular diseases such as dense deposit disease (DDD), C3GN, and IgA vasculitis with nephritis [11], as well as streptococcal infection-related nephritis (SIRN). In the present case, the NAPlr deposition in glomeruli along with the high serum ASO and ASK titers indicated that IgA vasculitis was induced by a streptococcal infection. It has been reported that 30% of IgA vasculitis with NAPlr deposition in glomeruli were seen in the pediatric population [4]. However, to our knowledge there are no reports of NAPlr deposition in an elderly patient.

The Gd-IgA1 is the IgA1 which lacks galactose in the O-glycan chain, which is produced by abnormal regulation of post-translational modifications in mucosal secreting cells due to a gene–microbe interaction [3]. In the present case, the NAPlr caused by streptococcal infection may have been involved, probably through the modification of mucosal immunity after streptococcal infection. However, the causal relationship between NAPlr deposition and Gd-IgA1 deposition is still unknown in the present study. It is well known that Gd-IgA1 is specifically deposited in the glomeruli in IgA nephropathy and IgA vasculitis nephritis [13]. In this case of IgA vasculitis, the deposition of Gd-IgA1 was noted in both the small vessels in the skin as well as the glomeruli in the kidney. The pathology from both the skin and kidney showed similar findings, including neutrophil infiltration and extravasation of red blood cells in leukocytoclastic vasculitis in the skin and endocapillary proliferative and crescentic GN in the kidney. These findings might indicate that the development of GN and purpura in IgA vasculitis may share a Gd-IgA1 related pathogenesis.

In the serum Gd-IgA1 levels in IgA vasculitis, it has been reported that the patients with systemic symptoms due to IgA vasculitis, such as nephritis and gastrointestinal symptoms in addition to purpura had higher Gd-IgA1 levels in serum than patients with localized IgA vasculitis with only purpura [3]. In addition, IgA vasculitis with nephritis patient had higher Gd-IgA1 levels than healthy control, although there was no significant difference between IgA vasculitis without nephritis and healthy control [14]. These studies indicated that, although our case did not measure the serum Gd-IgA1 levels, high levels of serum Gd-IgA1 in IgA vasculitis may be indicated in systemic IgA vasculitis, such as the present case.

In conclusion, palpable purpura and renal impairment occurred after transient fever, and high ASO and ASK levels in serum led us to the suspicion of IgA vasculitis caused by streptococcal infection. The deposition of NAPlr in glomeruli indicated that the streptococcal infection was associated with the occurrence of GN in IgA vasculitis, pathologically. In addition, the deposition of Gd-IgA1, which is thought to be involved in the pathogenesis of IgA vasculitis, was confirmed in both the kidney and skin, indicating that the pathogenesis of purpura and GN shares the Gd-IgA1-related pathogenic mechanisms. The streptococcal infection-associated IgA vasculitis was confirmed pathologically by the deposition of NAPlr in glomeruli, and Gd-IgA1 in glomeruli and cutaneous small vessels.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mr. Takashi Arai, Ms. Kyoko Wakamatsu, and Ms. Naomi Kuwahara for their technical assistance.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Research involving human and animal participation

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient described.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sugino H, Sawada Y, Nakamura M. IgA vasculitis: etiology, treatment, biomarkers and epigenetic changes. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 doi: 10.3390/ijms22147538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hastings MC, Rizk DV, Kiryluk K, Nelson R, Zahr RS, Novak J, et al. IgA vasculitis with nephritis: update of pathogenesis with clinical implications. Pediatr Nephrol. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s00467-021-04950-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neufeld M, Molyneux K, Pappelbaum KI, Mayer-Hain S, von Hodenberg C, Ehrchen J, et al. Galactose-deficient IgA1 in skin and serum from patients with skin-limited and systemic IgA vasculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(5):1078–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Masuda M, Nakanishi K, Yoshizawa N, Iijima K, Yoshikawa N. Group A streptococcal antigen in the glomeruli of children with Henoch-Schönlein nephritis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41(2):366–370. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2003.50045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yumura W, Kobayashi S, Suka M, Hayashi T, Ito S, Nagafuchi H, et al. Assessment of the Birmingham vasculitis activity score in patients with MPO-ANCA-associated vasculitis: sub-analysis from a study by the Japanese Study Group for MPO-ANCA-associated vasculitis. Mod Rheumatol. 2014;24(2):304–309. doi: 10.3109/14397595.2013.854075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim S, Lee NY. Asymptomatic infection by Streptococcus pyogenes in schoolchildren and diagnostic usefulness of antideoxyribonuclease B. J Korean Med Sci. 2005;20(6):938–940. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2005.20.6.938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nasr SH, D’Agati VD. IgA-dominant postinfectious glomerulonephritis: a new twist on an old disease. Nephron Clin Pract. 2011;119(1):c18–c25. doi: 10.1159/000324180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nasr SH, Fidler ME, Valeri AM, Cornell LD, Sethi S, Zoller A, et al. Postinfectious glomerulonephritis in the elderly. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(1):187–195. doi: 10.1681/asn.2010060611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han W, Suzuki T, Watanabe S, Nakata M, Ichikawa D, Koike J, et al. Galactose-deficient IgA1 and nephritis-associated plasmin receptors as markers for IgA-dominant infection-related glomerulonephritis: a case report. Medicine. 2021;100(5):e24460. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000024460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamakami K, Yoshizawa N, Wakabayashi K, Takeuchi A, Tadakuma T, Boyle MD. The potential role for nephritis-associated plasmin receptor in acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis. Methods. 2000;21(2):185–197. doi: 10.1006/meth.2000.0990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oda T, Yoshizawa N, Yamakami K, Sakurai Y, Takechi H, Yamamoto K, et al. The role of nephritis-associated plasmin receptor (NAPlr) in glomerulonephritis associated with Streptococcal infection. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012;2012:417675. doi: 10.1155/2012/417675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oda T, Yamakami K, Omasu F, Suzuki S, Miura S, Sugisaki T, et al. Glomerular plasmin-like activity in relation to nephritis-associated plasmin receptor in acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(1):247–254. doi: 10.1681/asn.2004040341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suzuki H, Yasutake J, Makita Y, Tanbo Y, Yamasaki K, Sofue T, et al. IgA nephropathy and IgA vasculitis with nephritis have a shared feature involving galactose-deficient IgA1-oriented pathogenesis. Kidney Int. 2018;93(3):700–705. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang M, Zhang X, Li X, Lei L, Zhang H, Ling C, et al. Serum levels of galactose-deficient IgA1 in Chinese children with IgA nephropathy, IgA vasculitis with nephritis, and IgA vasculitis. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2021;25(1):37–43. doi: 10.1007/s10157-020-01968-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]