Abstract

Lactobacillus plantarum C11 produces plantaricin E/F (PlnE/F) and plantaricin J/K (PlnJ/K), two bacteriocins whose activity depends on the complementary action of two peptides (PlnE and PlnF; PlnJ and PlnK). Three of the individual Pln peptides possess some antimicrobial activity, but the highest bacteriocin activity is obtained by combining complementary peptides in about a one-to-one ratio. Circular dichroism was used to study the structure of the Pln peptides under various conditions. All four peptides were unstructured under aqueous conditions but adopted a partly alpha-helical structure in the presence of trifluoroethanol, micelles of dodecylphosphocholine, and negatively charged dioleoylphosphoglycerol (DOPG) liposomes. Far less structure was induced by zwitterionic dioleoylglycerophosphocholine liposomes, indicating that a net negative charge on the phospholipid bilayer is important for a structure-inducing interaction between (positively charged) Pln peptides and a membrane. The structuring of complementary peptides was considerably enhanced when both (PlnE and PlnF or PlnJ and PlnK) were added simultaneously to DOPG liposomes. Such additional structuring was not observed in experiments with trifluoroethanol or dodecylphosphocholine, indicating that the apparent structure-inducing interaction between complementary Pln peptides requires the presence of a phospholipid bilayer. The amino acid sequences of the Pln peptides are such that the alpha-helical structures adopted upon interaction with the membrane and each other are amphiphilic in nature, thus enabling membrane interactions.

Many bacteria secrete ribosomally synthesized antimicrobial polypeptides, termed bacteriocins. The bacteriocins produced by gram-positive bacteria are normally membrane-permeabilizing cationic peptides with less than 60 amino acid residues (1, 22, 23, 25, 26, 31). These peptide bacteriocins may be classified into two major groups: the posttranslationally modified bacteriocins (group I), often called lantibiotics, and the unmodified bacteriocins (group II). The latter group includes bacteriocins such as lactococcin G (24), lactacin F (3), thermophilin 13 (18), and plantaricin S (14, 30), whose activity depends on or is augmented by the interaction between two peptides of 25 to 40 residues each. Maximum bactericidal activity is obtained when the two peptides are present in approximately equal amounts, consistent with their genes being next to each other on the same operon (22, 23).

Plantaricin E/F (PlnE/F) and plantaricin J/K (PlnJ/K) are two recently identified two-peptide bacteriocins, both of which are produced by Lactobacillus plantarum C11 (4). The antimicrobial activity of PlnE/F depends on the complementary action of the two peptides PlnE and PlnF, whose genes are located next to each other on the plnEFI operon (4, 8). Likewise, the activity of PlnJ/K depends on the two peptides PlnJ and PlnK, whose genes are located next to each other on the plnJKLR operon (4, 8). The interaction between complementary peptides is specific; neither PlnE nor PlnF is able to function together with either PlnJ or PlnK (4). PlnE, PlnF, PlnJ, and PlnK are all cationic, and they contain 33, 34, 25, and 32 amino acid residues, respectively. All four peptides have regions, 18 to 24 amino acid residues in length, that will become amphiphilic if they adopt an α-helical secondary structure (4).

To permit studies of the activity, structure, and mode of action of the various Pln peptides, they were synthesized by solid-phase peptide synthesis and subsequently purified (4; this study). These synthetic peptides retain biological activity, and they have been used for assessment of the (different) target cell specificities of PlnE/F and PlnJ/K (4). In the present study, PlnE/F and PlnJ/K have been characterized with respect to their secondary structure under various conditions. Furthermore, possible structure-inducing interactions between complementary peptides were investigated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Synthesis, purification, and analysis of peptides.

PlnE, PlnF, PlnJ, and PlnK, were synthesized according to the amino acid sequences reported earlier (4, 8) and solubilized in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid. For purification, PlnE was first applied to a Mono S HR 5/5 cation-exchange column (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) equilibrated with 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 5.3) containing 20% (vol/vol) 2-propanol and 6 M urea by using the fast protein liquid chromatography system (Pharmacia Biotech). The peptide was eluted from the column with a linear 0.0 to 0.3 M NaCl gradient containing 20% (vol/vol) 2-propanol and 6 M urea. PlnE was then applied to a PepRPC HR 5/5 C2/C18 reverse-phase column (Pharmacia Biotech) equilibrated with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid by using the fast protein liquid chromatography system. The peptide was eluted from the reverse-phase column with a linear 20 to 45% 2-propanol gradient containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid. The chromatography fraction containing the peptide was then diluted four- to fivefold with H2O containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid and rechromatographed on the reverse-phase column. The latter step was repeated two to three times until a homogeneous fraction of PlnE was obtained. PlnJ and PlnK were purified similarly, except that the first cation-exchange chromatography step was omitted. PlnF was commercially synthesized and purified by Joe Gray, Newcastle University Facility for Molecular Biology. The primary structures and purity (greater than 90%) of the four peptides were confirmed by protein sequencing (Applied Biosystems automatic sequencer with an on-line 120A phenylthiohydantion amino acid analyzer), matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectroscopy analysis (HP 2025A), and by analytical reverse-phase chromatography using a μRPC SC 2.1/10 C2/C18 column on the SMART system (Pharmacia Biotech).

Bacteriocin assay.

Bacteriocin activity was determined essentially as described earlier (24), by using a microtiter plate assay. Twofold dilutions of bacteriocin were made in MRS broth (Oxoid); indicator cells (L. plantarum 965) from a fresh overnight culture (diluted in MRS broth) were added to a final optical density at 600 nm of ∼0.001 and a total volume per well of 200 μl. The microtiter plate cultures were incubated for 10 to 15 h at 30°C, after which growth inhibition of the indicator organism was measured spectrophotometrically at 600 nm by use of a Dynatech microplate reader.

Determination of peptide concentration.

The A280 was measured, and the peptide concentration was calculated by using molar extinction coefficients at 280 nm deduced from the amino acid composition of the peptides.

Liposome preparation.

Single-bilayer phospholipid vesicles were prepared essentially in accordance with the procedure of Batzri and Korn (5). Eight micromoles of dioleoyl-l-α-phosphatidyl-dl-glycerol (DOPG; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) or dioleoyl-l-α-phosphatidylcholine (DOPC, Sigma) dissolved in chloroform was carefully dried under a stream of ultrapure nitrogen. The dried lipids were redissolved in 1 volume of absolute ethanol and dried again. Subsequently, the lipids were redissolved in 200 μl of absolute ethanol and, slowly (approximately 100 μl/min) and at constant speed, injected into 4 ml of 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 5.3) at room temperature. Ethanol was removed by dialysis against 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 5.3).

CD.

Circular dichroism (CD) spectra were recorded by using a Jobin-Yvon autodichrograph Mark IV spectropolarimeter calibrated with epiandrosterone. Measurements were performed at 25°C by using a quartz cuvette with a path length of 0.05 or 0.5 cm. Most measurements were done by using the 0.05-cm cuvette, and this is the cuvette used unless stated otherwise. Measurements using the 0.05-cm cuvette were done with a peptide concentration of 0.15 mg/ml of 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 5.3). For the 0.5-cm cuvette, a 20-times lower peptide concentration was used. Measurements in the 0.5-cm cuvette were primarily done to investigate the concentration dependency of structure induction. For all of the conditions used in this study, structure induction was independent of peptide concentration.

Samples were scanned four to eight times at 20 nm/min with a time constant of 2 s and a slit width of 2 nm, usually over a wavelength range 183 to 245 nm. The data were averaged, and the spectrum of a protein-free control sample was subtracted, thus giving the mean residual ellipticity of the peptide. The α-helical contents of the peptides under the various solvent conditions were calculated, from the mean residual ellipticity at 222 nm ([θ]222), by using the following formula: ƒH = [θ]222/[−40,000(1 − 2.5/n)], where ƒH represents the α-helical content and n represents the number of peptide bonds (27). All measurements were conducted at least twice. Crucial measurements were repeated several times, and standard deviations in the percentage of helicity were below 2%.

RESULTS

Amounts of complementary peptides necessary to attain antagonistic activity.

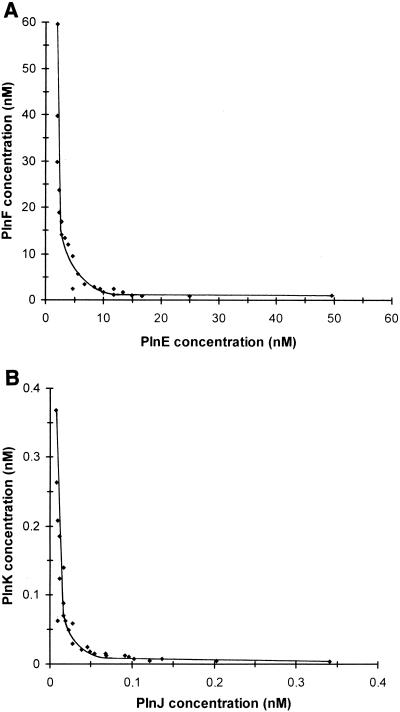

Concentrations of complementary peptides (PlnE together with PlnF and PlnJ together with PlnK) which, in combination, inhibited the growth of the indicator organism by 50% are plotted in Fig. 1. These plots (i.e., isobolograms; see reference 6) reveal that the highest activity-to-peptide ratio was obtained when complementary peptides were present in approximately equal amounts: between 5 and 10 nM for each of the PlnE/F peptides (Fig. 1A) and between 0.02 and 0.05 nM for each of the PlnJ/K peptides (Fig. 1B). Complementary peptides could, nevertheless, partly substitute for each other; the curvature in the isobolograms shows that a reduction in the concentration of one peptide could, to some extent, be compensated for by an increase in the concentration of the complementary peptide (i.e., activity lost upon decreasing the concentration of one Pln peptide could, to some extent, be regained by increasing the concentration of the complementary peptide) (Fig. 1). In fact, the isobologram for PlnE/F intersects the y axis at about 5,000 nM PlnF (data not shown), and the isobologram for PlnJ/K intersects both the x and y axes at about 20 nM PlnJ and 200 nM PlnK, respectively (data not shown). Thus, PlnF, PlnJ, and PlnK individually exerted antagonistic activity at concentrations of, respectively, 5,000, 20, and 200 nM. These concentrations are more than 103 times greater than the concentrations at which these peptides exerted antagonistic activity in the presence of their complementary peptides. PlnE alone had no antagonistic activity at the highest concentration tested (13 μM).

FIG. 1.

Isobolograms showing amounts of PlnE and PlnF in combination (A) and amounts of PlnJ and PlnK in combination (B) that inhibited the growth of the indicator strain (L. plantarum 965) by 50%.

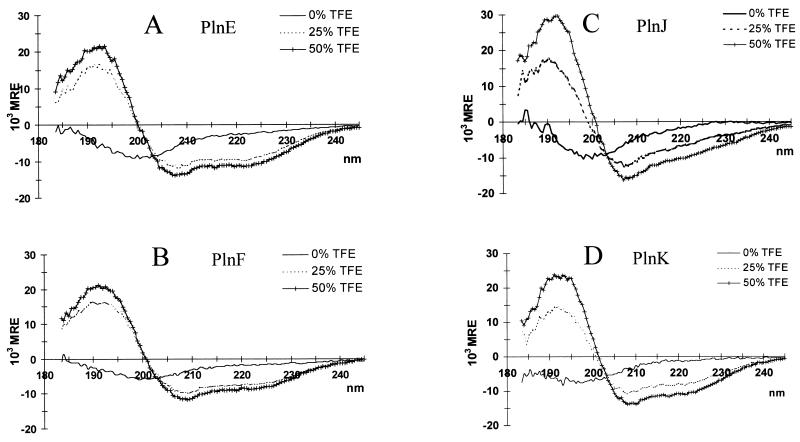

TFE titrations show that PlnE/F and PlnJ/K have an intrinsic tendency to adopt α-helical structure.

The CD spectra of PlnE, PlnF, PlnJ, and PlnK in aqueous solution (pH 5.3) were all characteristic of nonstructured conformations (random coil, with α-helical contents of less than about 5%), irrespectively of whether peptides were measured individually (Fig. 2) or whether complementary peptides were combined (data not shown). Trifluoroethanol (TFE) induces and stabilizes α-helical structure in polypeptides that have an intrinsic tendency to adopt this kind of secondary structure (13, 17, 29). In the presence of TFE, all four peptides yielded CD spectra typical for partly α-helical peptides. At 50% TFE, calculated helicities were 31, 23, 26, and 29% for PlnE, PlnF, PlnJ, and PlnK, respectively. No further increase in these percentages was observed when the TFE concentration was increased to 65% (results not shown). The spectra of two complementary peptides together in TFE were similar to the calculated average of the spectra of individual peptides in TFE (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

CD spectra of PlnE (A), PlnF (B), PlnJ (C), and PlnK (D) (0.15 mg of peptide per ml of 20 mM sodium phosphate, pH 5.3) exposed to various concentrations of TFE. MRE, mean residual ellipticity.

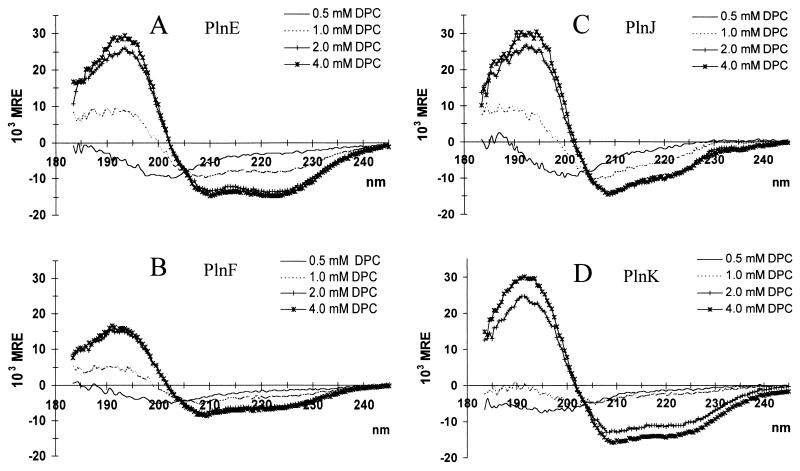

Micelles induce α-helical structure in PlnE/F and PlnJ/K.

CD spectra of PlnE, PlnF, PlnJ, and PlnK were recorded in the presence of dodecylphosphocholine (DPC) at concentrations ranging from 0.5 mM (which is below the critical micelle concentration (CMC) of 1.1 mM [15] to 8 mM (which is above the CMC). No significant structuring of the peptides occurred at DPC concentrations below the CMC (Fig. 3; Table 1). However, helical structure was induced in all of the peptides once the DPC concentration exceeded the CMC, and maximal helical contents (varying from 17 to 41% [Table 1]) were attained at 2 to 4 mM DPC (Fig. 3). A further increase in the DPC concentration to 8 mM did not result in additional structuring (data not shown). At 1 mM DPC, a transition state was observed, where the helical contents were between those in aqueous solutions and those attained at higher DPC concentrations (Fig. 3; Table 1). As was the case in TFE, the spectra of two complementary peptides together in DPC were similar to the calculated average of the spectra of individual peptides (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

CD spectra of PlnE (A), PlnF (B), PlnJ (C), and PlnK (D) (0.15 mg of peptide per ml of 20 mM sodium phosphate, pH 5.3) exposed to various concentrations of DPC. MRE, mean residual ellipticity.

TABLE 1.

Helical contents of Pln peptides under various solvent conditions

| Solvent and concn (mM) | Helical content (%)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PlnE | PlnF | PlnJ | PlnK | |

| DPC | ||||

| 0.0 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 0.5 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 1.0 | 21 | 7 | 11 | 4 |

| 2.0 | 37 | 16 | 25 | 30 |

| 4.0 | 41 | 17 | 24 | 38 |

| DOPG, 1.4 | 36 | 22 | 34 | 28 |

| DOPC, 1.4 | 15 | 4 | 6 | 2 |

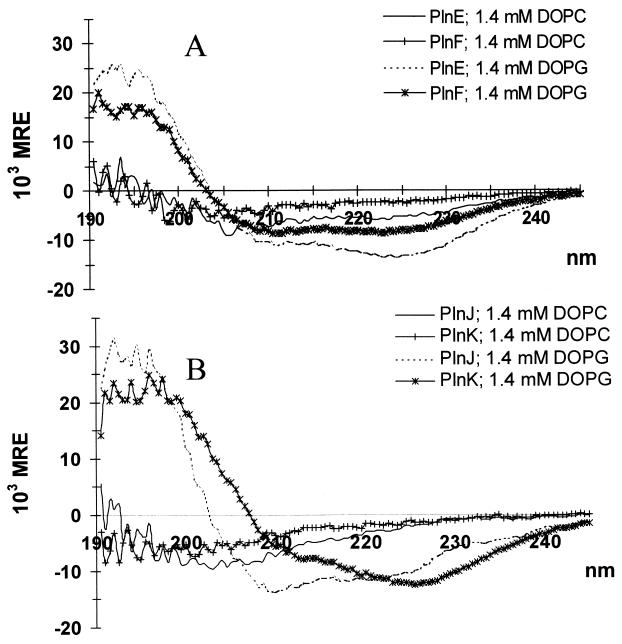

Complementary peptides interact and induce structure in each other upon exposure to anionic liposomes.

All four peptides adopted a partly helical structure when exposed to anionic DOPG liposomes (Fig. 4; Table 1). Zwitterionic DOPC liposomes, however, were poor structure inducers compared to the anionic DOPG liposomes (Fig. 4; Table 1). Liposomes containing DOPG and DOPC in equal amounts induced amounts of structuring similar to those induced by pure DOPG liposomes, whereas liposomes containing 90% DOPC and 10% DOPG induced structuring which was intermediate between the amounts induced by pure DOPG and pure DOPC liposomes (results not shown). Measurements were conducted by using a molar lipid-to-peptide ratio between 20:1 and 40:1. At these ratios, maximal structure induction was obtained, as illustrated by the fact that increasing the lipid-to-peptide ratio 10- to 20-fold had no significant effect on the CD spectra (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

CD spectra of PlnE and PlnF (A) and PlnJ and PlnK (B) (0.15 mg of peptide per ml of 20 mM sodium phosphate, pH 5.3) exposed to liposomes (1.4 mM either DOPG or DOPC). MRE, mean residual ellipticity.

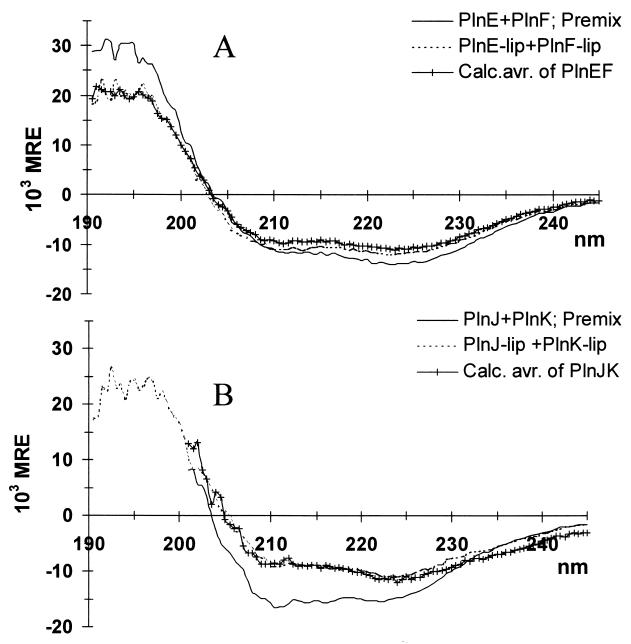

To investigate possible structure-inducing interactions between complementary peptides, two types of samples were prepared for the CD measurements. (i) Complementary peptides were premixed before adding liposomes, and (ii) liposomes containing one peptide were mixed with liposomes containing the complementary peptide. When the peptides were premixed, helical contents of 38 and 42% were obtained for PlnE/F and PlnJ/K, respectively, which are 9 and 12% higher than the contents calculated on the basis of the spectra for the individual peptides (Fig. 5; Table 2). Thus, the peptides induced additional α-helical structure in each other and must, therefore, interact in some way. The extent of additional structuring obtained upon simultaneous addition of complementary Pln peptides to DOPG liposomes did not depend on the peptide concentration in the range of 0.0075 to 0.15 mg/ml (data not shown). Remarkably, a similar induction of additional structure was obtained neither when liposomes containing one peptide were mixed with liposomes containing the complementary peptide (Fig. 5; Table 2) nor when the peptides were added to the liposomes consecutively instead of simultaneously (for PlnEF, Table 2).

FIG. 5.

CD spectra of PlnE combined with PlnF (A) and PlnJ combined with PlnK (B) in 20 mM sodium phosphate, pH 5.3, containing DOPG liposomes (1.4 mM DOPG). Premix indicates that complementary peptides were mixed prior to addition of liposomes. PlnE-lip and PlnF-lip indicate mixtures of liposomes with PlnE and PlnF, respectively. The spectrum labeled Calc. avr. is the calculated average of the spectra obtained for the individual peptides in the presence of DOPG liposomes. Analogous terminology is used for PlnJ and PlnK in panel B. Equimolar mixtures of PlnE and PlnF were measured by using a total peptide concentration of 0.15 mg/ml and a 0.05-cm cuvette. Equimolar mixtures of PlnJ and PlnK were measured by using a total peptide concentration of 0.0075 mg/ml and a 0.5-cm cuvette. MRE, mean residual ellipticity.

TABLE 2.

Helical contents of Pln peptides upon combination of complementary peptides in DOPG liposomes

| Mixing procedure | Helical content (%) of peptide combination

|

|

|---|---|---|

| PlnE + PlnF | PlnJ + PlnK | |

| Mixing two peptides before adding liposomes | 38 | 42 |

| Mixing two liposome-peptide solutions | 32 | 30 |

| Calculated avg of two peptides based on individual measurements | 29 | 30 |

| Sequential addition of PlnF and then PlnE | 28 | |

| Sequential addition of PlnE and then PlnF | 25 | |

DISCUSSION

PlnE/F and PlnJ/K are both clearly two-peptide bacteriocins, although three of the four Pln peptides (PlnF, PlnJ, and PlnK) had some bacteriocin activity when tested individually. However, they were 103 times more active when combined with their complementary peptide (PlnE together with PlnF and PlnJ together with PlnK) than they were individually, optimal activity being obtained when two complementary peptides were present in approximately equal amounts (Fig. 1). Accordingly, genes encoding complementary peptides are located next to each other on the same transcriptional unit (8) and are thus transcribed to the same extent. Both PlnE/F and PlnJ/K resemble the two-peptide bacteriocins lactacin F (3), thermophilin 13 (18), and plantaricin S (14) in that one or both of the complementary peptides have some activity alone. They differ from the two-peptide bacteriocin lactococcin G, for which the individual peptides are totally inactive (21).

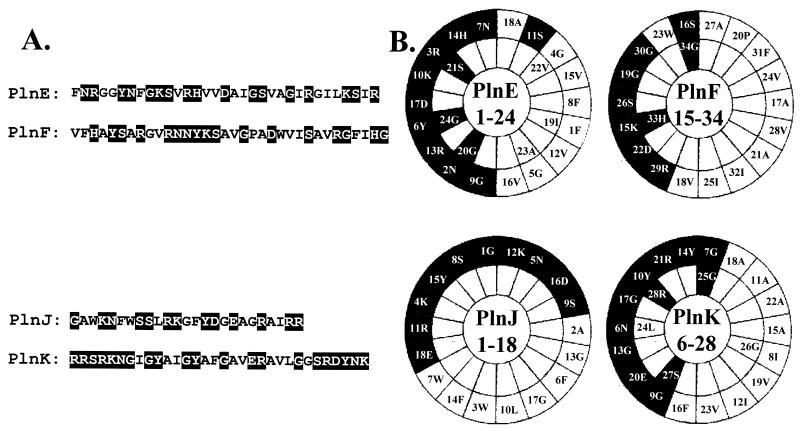

The CD studies showed that PlnE, PlnF, PlnJ, and PlnK are unstructured in phosphate buffer (aqueous conditions). Studies with TFE and DPC clearly showed, however, that all four peptides have an intrinsic tendency to adopt a partly α-helical structure in more-hydrophobic environments. Structuring induced by DPC occurred only at concentrations above the CMC, indicating that an interaction with micelles, rather than with free DPC molecules, induced structure. Alpha-helical structures were also adopted when the peptides were allowed to interact with anionic DOPG liposomes, which are the most natural of the membrane-mimicking agents used in this study. Although it is not known which parts of the peptides become helical, it is very likely that the helices that are formed have an amphiphilic character. The amino acid sequences in regions covering about 70% of PlnE, PlnF, PlnJ, and PlnK are such that the polar residues would end up on one side and the nonpolar residues would end up on the other side, if an α-helical structure was adopted (Fig. 6). Two-peptide bacteriocins—such as lactococcin G (20, 21), lactacin F (2, 7), and thermophilin 13 (18)—whose mode of action has been studied, have been shown to kill cells by permeabilizing the cell membrane. Taken together, these results and observations strongly indicate that the bactericidal action of PlnE/F and PlnJ/K involves the formation of amphiphilic α-helices, which enables the peptides to interact with and permeabilize the target cell membrane.

FIG. 6.

Sequences of PlnE, PlnF, PlnJ, and PlnK (A) and helical-wheel representation of regions that may form an amphiphilic α-helix (B). Residues: 1 to 24 in PlnE, 15 to 34 in PlnF, 1 to 18 in PlnJ, and 6 to 28 in PlnK. The black and white boxes indicate polar and nonpolar residues, respectively. Glycine is included in both black and white boxes as it is treated as being neutral with respect to polarity.

Zwitterionic liposomes induced much less structure in the various peptides than did anionic liposomes. This observation may reflect the importance of electrostatic interactions of the cationic peptides with the negative charge on vesicles. This is consistent with the hypothesis that the cationic character of nearly all membrane-interacting antimicrobial peptides enables interaction with the negatively charged phospholipids that are predominant in bacterial membranes (10, 12, 16, 19, 25, 28, 32).

The synergistic effects observed when combining two complementary peptides may be due to (i) the two peptides interacting individually and independently with target cells, each peptide exerting effects which individually result in little, if any, toxicity, but which are toxic when combined, or (ii) the two peptides interacting with each other, forming a complex that functions more efficiently than either peptide does alone. The results showing that the complementary Pln peptides interact and induce additional helical structuring in each other when combined in the presence of liposomes—and similar results obtained with the two peptides constituting the two-peptide bacteriocin lactococcin G (12)—are consistent with the latter of these two models. For all three of these two-peptide bacteriocins (PlnE/F, PlnJ/K, and lactococcin G), it thus appears that upon arrival at the target membrane, complementary peptides interact with each other and with the membrane in a structure-inducing manner, resulting in the formation of a membrane-associated peptide complex with amphiphilic α-helical structure. Whereas the lactococcin G peptides seem to interact and form complexes only in an approximately one-to-one ratio, the PlnE/F and PlnJ/K peptides may possibly interact and form complexes also in non-one-to-one ratios. This appeared to be the case, because complementary Pln peptides could partly substitute for each other; the activity lost when the concentration of one Pln peptide was decreased could, to some extent, be regained by increasing the concentration of the complementary peptide. This is not the case for lactococcin G, as even a great increase in the amount of one of the complementary peptides beyond a one-to-one ratio does not increase the activity (21).

In contrast to liposomes, neither TFE nor DPC micelles triggered complementary peptides to interact and induce additional helical structuring in each other. The shape and/or size of the DPC micelles may, possibly, not permit the formation of a functional multimer complex of complementary peptides. It should be noted that the structure-inducing interaction between complementary peptides attained upon simultaneous exposure to liposomes was observed neither when liposomes containing one peptide were mixed with liposomes containing the complementary peptide nor when the peptides were added to the liposomes consecutively instead of simultaneously. Similar results have been obtained with the two peptides constituting the two-peptide bacteriocin lactococcin G (12). Apparently, the individual peptides rapidly associated with the membrane in a virtually irreversible manner that makes them inaccessible for interaction with the complementary peptide.

The formation of a complex between complementary peptides upon contact with or insertion into liposomes appears to occur at a much faster rate than the association of individual peptides with liposomes, since the extent of additional structuring obtained upon simultaneous addition of complementary peptides to liposomes did not depend on the peptide concentration. This also indicates that in the presence of liposomes, the equilibrium between the individual peptides and the complexed peptides seems to lie far to the right.

The amphiphilic α-helix is generally considered to be a structural motif that enables interaction with and permeabilization of cell membranes. The motif is found in several different types of membrane-permeabilizing eukaryotic antimicrobial peptides (10, 19, 25), as well as in the two-peptide bacteriocins lactococcin G (12), PlnE/F, and PlnJ/K; the pediocin-like bacteriocin leucocin A (9); and the bacteriocin-like pheromone plantaricin A (11). For the 22-mer plantaricin A, it seems that formation of an amphiphilic helix per se is sufficient for the peptide to exert strain-specific antagonistic activity (11). This activity is based on permeabilization of target cells through a nonchiral interaction with the cell membrane (11). Unraveling further structural details of the permeabilization process and identification of the structural features underlying the marked target cell specificities often observed for membrane-permeabilizing amphiphilic helical peptides are important challenges for further research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Norwegian Research Council.

We thank Bjørg Egelandsdal at The Norwegian Food Research Institute, Ås, Norway, for making a CD spectrometer available to us.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abee T. Pore-forming bacteriocins of Gram-positive bacteria and self-protection mechanisms of producer organisms. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;129:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(95)00137-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abee T, Klaenhammer T R, Letellier L. Kinetic studies of the action of lactacin F, a bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus johnsonii that forms poration complexes in the cytoplasmic membrane. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:1006–1013. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.3.1006-1013.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allison G E, Fremaux C, Klaenhammer T R. Expansion of bacteriocin activity and host range upon complementation of two peptides encoded within the lactacin F operon. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2235–2241. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.8.2235-2241.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderssen E L, Diep D B, Nes I F, Eijsink V G H, Nissen-Meyer J. Antagonistic activity of Lactobacillus plantarum C11: two new two-peptide bacteriocins, plantaricin EF and JK, and the induction factor plantaricin A. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:2269–2272. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.6.2269-2272.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Batzri S, Korn E D. Single bilayer liposomes prepared without sonication. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1973;298:1015–1019. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(73)90408-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berenbaum M C. Criteria for analyzing interactions between biologically active agents. Adv Cancer Res. 1981;34:269–335. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60912-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruno M E C, Montville T J. Common mechanistic action of bacteriocins from lactic acid bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:3003–3010. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.9.3003-3010.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diep D B, Håvarstein L S, Nes I F. Characterization of the locus responsible for bacteriocin production in Lactobacillus plantarum C11. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4472–4483. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.15.4472-4483.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallagher N L F, Sailer M, Niemczura W P, Nakashama T T, Stiles M E, Vederas J C. Three-dimensional structure of lactocin A in trifluoroethanol and dodecylphosphocholine micelles: spatial location of residues critical for biological activity in type IIa bacteriocins from lactic acid bacteria. Biochemistry. 1997;36:15062–15072. doi: 10.1021/bi971263h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hancock R E W. Peptide antibiotics. Lancet. 1997;349:418–422. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)80051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hauge H H, Mantzilas D, Moll G N, Konings W N, Driessen A J M, Eijsink V G H, Nissen-Meyer J. Plantaricin A is an amphiphilic α-helical bacteriocin-like pheromone which exerts antimicrobial and pheromone activities through different mechanisms. Biochemistry. 1998;37:16026–16032. doi: 10.1021/bi981532j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hauge H H, Nissen-Meyer J, Nes I F, Eijsink V G H. Amphiphilic α-helices are important structural motifs in the α and β peptides that constitute the bacteriocin lactococcin G: enhancement of helix formation upon α-β interaction. Eur J Biochem. 1998;251:565–572. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2510565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jasanoff A, Fersht A R. Quantitative determination of helical propensities from trifluoroethanol titration curves. Biochemistry. 1994;33:2129–2135. doi: 10.1021/bi00174a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiménez-Diaz R, Ruiz-Barba J L, Cathcart D P, Holo H, Nes I F, Sletten K H, Warner P. Purification and partial amino acid sequence of plantaricin S, a bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus plantarum LPCO10, the activity of which depends on the complementary action of two peptides. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:4459–4463. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.12.4459-4463.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lauterwein J, Bösch C, Brown L R, Wüthrich K. Physicochemical studies of the protein-lipid interactions in melittin-containing micelles. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1979;556:244–264. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(79)90046-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lehrer R I. Defensins: antimicrobial and cytotoxic peptides of mammalian cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 1993;11:105–128. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.000541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lehrman S R, Tuls J L, Lund M. Peptide α-helicity in aqueous trifluoroethanol: correlations with predicted α-helicity and the secondary structure of the corresponding regions of bovine growth hormone. Biochemistry. 1990;29:5590–5596. doi: 10.1021/bi00475a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marciset O, Jeronimus-Stratingh M C, Mollet B, Poolman B. Thermophilin 13, a nontypical antilisterial poration complex bacteriocin, that functions without a receptor. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:14277–14284. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.22.14277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin E, Ganz T, Lehrer R I. Defensins and other endogenous peptide antibiotics of vertebrates. J Leukocyte Biol. 1995;58:128–136. doi: 10.1002/jlb.58.2.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moll G, Hauge H H, Nissen-Meyer J, Nes I F, Konings W N, Driessen A J M. Mechanistic properties of the two-component bacteriocin lactococcin G. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:96–99. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.1.96-99.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moll G, Ubbink-Kok T, Hauge H H, Nissen-Meyer J, Nes I F, Konings W N, Driessen A J M. Lactococcin G is a potassium ion-conducting, two-component bacteriocin. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:600–605. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.3.600-605.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nes I F, Diep D B, Håvarstein L S, Brurberg M B, Eijsink V G H, Holo H. Biosynthesis of bacteriocins in lactic acid bacteria. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 1996;70:113–128. doi: 10.1007/BF00395929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nissen-Meyer J, Hauge H H, Fimland G, Eijsink V G H, Nes I F. Ribosomally synthesized antimicrobial peptides produced by lactic acid bacteria: their function, structure, biogenesis, and their mechanism of action. Recent Res Dev Microbiol. 1997;1:141–154. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nissen-Meyer J, Holo H, Håvarstein L S, Sletten K, Nes I F. A novel lactococcal bacteriocin whose activity depends on the complementary action of two peptides. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5686–5692. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.17.5686-5692.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nissen-Meyer J, Nes I F. Ribosomally synthesized antimicrobial peptides: their function, structure, biogenesis, and mechanism of action. Arch Microbiol. 1997;167:67–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sahl H G, Jack R W, Bierbaum G. Biosynthesis and biological activities of lantibiotics with unique post-translational modifications. Eur J Biochem. 1995;230:827–853. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scholtz J M, Qian H, York E J, Stewart J M, Baldwin R L. Parameters of helix-coil transition theory for alanine-based peptides of varying chain lengths in water. Biopolymers. 1991;31:1463–1470. doi: 10.1002/bip.360311304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Selsted M E, Ouellette A J. Defensins in granules of phagocytic and non-phagocytic cells. Trends Cell Biol. 1995;5:114–119. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)88961-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sönnichsen F D, van Eyk J E, Hodges R S, Sykes D B. Effect of trifluoroethanol on protein secondary structure: an NMR and CD study using a synthetic actin peptide. Biochemistry. 1992;31:8790–8798. doi: 10.1021/bi00152a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stephens S K, Floriano B, Cathcart D P, Bayley V F W, Jiménez-Diaz R, Warner P J, Ruiz-Barba J L. Molecular analysis of the locus responsible for production of plantaricin S, a two-peptide bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus plantarum LPCO 10. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1871–1877. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.5.1871-1877.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Venema K, Venema G, Kok J. Lactococcal bacteriocins: mode of action and immunity. Trends Microbiol. 1995;3:299–304. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)88958-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.White S H, Wimley W C, Selsted M E. Structure, function, and membrane integration of defensins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1995;5:521–527. doi: 10.1016/0959-440x(95)80038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]