Abstract

The performance of high-yielding sows is directly related to the productivity of pig farming. Fetal development mainly occurs during the last month of pregnancy, and the aggressive metabolic burden of sows during this stage eventually leads to systemic oxidative stress. When affected by oxidative stress, sows exhibit adverse symptoms such as reduced feed intake, hindered fetal development, and even abortion. In addition, milk synthesis during the lactation period causes a severe metabolic burden. The biological response to oxidative stress during this period is associated with a decrease in milk production, which further affects the growth of piglets. Understanding the nutritional strategies to alleviate oxidative stress in sows is crucial to maintain their reproduction and lactation performance. Recently, advances have been made in the field of nutrition to relieve oxidative stress in sows during late pregnancy and lactation. This review highlights the nutritional strategies to relieve oxidative stress in sows reported within the last 20 years.

Keywords: Sow, Oxidative stress, Nutritional strategy, Plant extract, Selenium, Vitamin E

1. Introduction

During the late pregnancy and lactation stages, sows start suffering oxidative stress induced by severe metabolic burden and do not fully recover until the weaning period (Berchieri-Ronchi et al., 2011; Toy et al., 2009). This process is characterized by the accumulation of active oxygen, including superoxide (O2−) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), produced by the placenta and mammary glands (Esther et al., 2003), which negatively regulates reproductive performance and lactation performance. Excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) prevents the oocyte maturation, inhibits fertilization of sperm and egg cells, and increases the risk of prenatal death (Karowicz-Bilińska et al., 2002; Toy et al., 2009). Oxidative stress in sows decreased reproductive performance such as total litter size, live litter size and litter weight gain (Zhang et al., 2020, Zhang et al., 2020, Zhang et al., 2020). Furthermore, oxidative stress caused decreased feed intake of sows during lactation, which leads to prolonged negative energy balance and greater loss of body condition and reduced milk production (Black et al., 1993; Dima et al., 2009).

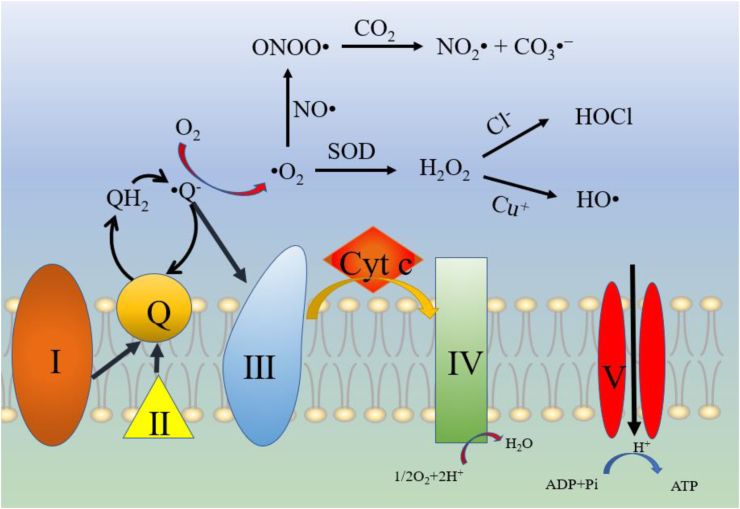

Oxidative stress is due to the amount of ROS produced exceeding the neutralization ability of antioxidants. Multiple external or environmental factors are proposed to trigger the generation of ROS, such as ultraviolet radiation, ionizing radiation, toxins, chemicals, extreme hot environments (the key factor causing heat stress in actual production) and other adverse conditions. Excessive ROS leads to oxidative damage to proteins, lipids and DNA and eventually destroys cell function. Cellular metabolism is accompanied by the production of ROS. These metabolic byproducts include O2−, H2O2, hydroxyl radicals (∙OH) and alkoxy radicals (RO). Under the process of aerobic respiration, cells oxidize and decompose nutrients to produce substances with high reducing forces that are transmitted along the mitochondrial electron transport chain. The production of mitochondrial ROS mainly occurs at two sites in the electron transport chain, namely, complex I (NADH dehydrogenase) and complex III (ubiquinone-cytochrome reductase). When electrons from complex I or II are transferred to coenzyme Q (ubiquinone), unstable intermediates in the coenzyme Q cycle lead to the formation of superoxide by transferring electrons directly to molecular oxygen (Finkel et al., 2000). Nitric oxide (NO) is a free radical molecule formed by a variety of cells, including airway and vascular smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells and epithelial cells (Ricciardolo et al., 2004). Reactive nitrogen species (RNS) are produced by the reaction of nitric oxide with reactive oxygen species (Fig. 1). These RNS include nitroxyl (HNO), nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and peroxynitrite (ONOO−) (Bove et al., 2006).

Fig. 1.

Main production process of ROS/RNS. Complex Ⅲ is the main source of mitochondrial ROS production. The electrons are transferred to coenzyme Q. Unstable coenzyme Q intermediates will directly transfer electrons to O2 to generate ∙O2, which in turn will generate lots of ROS and RNS. Excessive ROS/RNS will have a variety of damage to the cells. SOD = superoxide dismutase; ROS = reactive oxygen species; RNS = reactive nitrogen species.

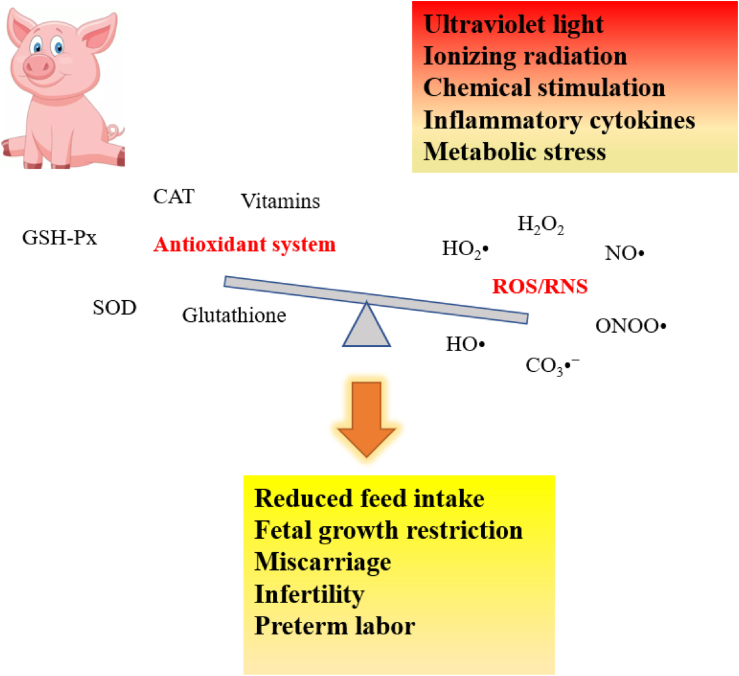

The detrimental or beneficial effects of ROS and RNS depend on their cellular concentrations (Valko et al., 2006). The beneficial effects of ROS occur at low or medium concentrations and are involved in resistance to pathogens and the regulation of many cellular signaling systems (Pizzino et al., 2017). Furthermore, ROS also play a physiological role in the cell's response to hypoxia (Valko et al., 2007). However, at high concentrations, the amounts of ROS/RNS exceed the neutralization abilities of enzymatic and nonenzymatic antioxidants. Excessive reactive oxygen species destroy cellular lipids, proteins or DNA and inhibit their corresponding biological functions, which could lead to decreases in lactation and reproductive performance, ultimately shortening sow life (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Causes of oxidative stress. Oxidative stress is caused by an imbalance between production and accumulation of ROS/RNS in cells and the ability of a biological system to detoxify these reactive products. Oxidative stress is reported to be involved in a variety of pregnancy complications, such as preterm labor, infertility fetal growth restriction and miscarriage. CAT = catalase; SOD = superoxide dismutase; GSH-Px = glutathione peroxidase; ROS = reactive oxygen species; RNS = reactive nitrogen species.

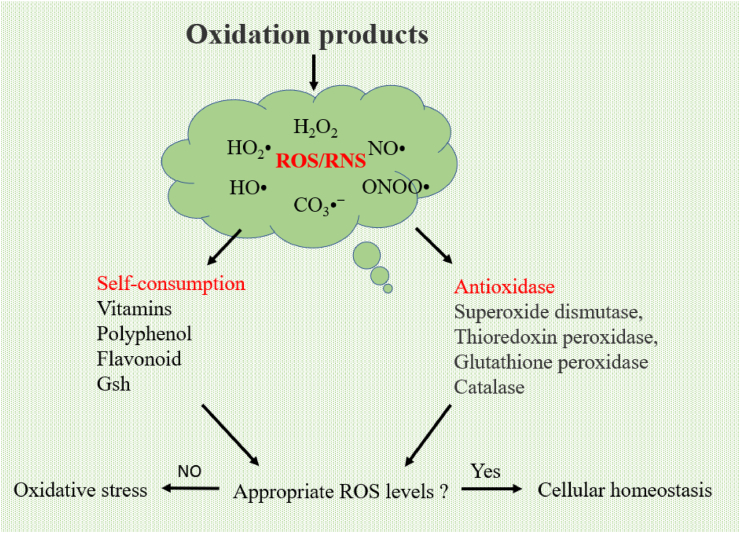

To eliminate excessive free radicals, cells develop a series of defense mechanisms during the process of evolution (Cadenas, 1997). These defense mechanisms are mainly composed of antioxidant enzymes and nonenzymatic antioxidants. Antioxidant enzymes mainly include superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), and catalase (CAT). Nonenzymatic antioxidants are represented by ascorbic acid (vitamin C), α-tocopherol (vitamin E), glutathione (GSH), carotenoids, flavonoids, etc (Fig. 3). Under normal conditions, there is a dynamic balance between the antioxidant system and free radicals, which is essential for the survival and health of organisms (Valko et al., 2006).

Fig. 3.

Metabolic pathways of ROS/RNS. ROS = reactive oxygen species; RNS = reactive nitrogen species.

In actual production, as heat stress can induce oxidative stress, using wet curtain ventilation system and installing spray device to control the temperature of the pigsty is an effective way to alleviate the oxidative stress in sows. In addition, genetic selection for a breed with stronger tolerance to oxidative stress is an alternative method for alleviating the detrimental conditions. The application of nutritional strategies to reduce the effects of oxidative stress is also an effective and economical way to reduce oxidative stress and is also more suitable for the current intensive farming model (Cottrell et al., 2015). Recently, a number of antioxidants such as vitamins, minerals and plant extracts have been shown to be effective in alleviating oxidative stress in sows in the late pregnancy and lactation stages. In this review, these antioxidants are categorized in reference to their origins and active ingredients, such as plants and extracts, microbial additives, vitamins, and other additives.

2. Plants and plant extracts

Plant-derived feed is a natural feed additive that includes herbs, spices, or food flavoring agents. Plant feed additives are usually added as whole beads or as extracts of plant-derived substances. Compared to antibiotics, they are reported to be natural, less toxic, residue-free, and desirable animal feed additives. It has been clarified that plant feed is rich in crude fiber and substances with reductive activity, such as terpenes, phenols, glycosides, saccharides, aldehydes, esters, and alcohols (Reyes-Camacho et al., 2020). These active ingredients are proposed to activate the immune system, stimulate the secretion of digestive juice, enhance antioxidant activity, and regulate the intestinal flora (Durmic et al., 2012). In addition, herbs are also reported to improve fetal development by increasing fetal blood glucose and growth hormone levels (Takei et al., 2007). Importantly, many reports have shown that the addition of plant components to sow feed can alleviate oxidative stress and has beneficial effects on the growth of piglets during the late pregnancy and lactation stages (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effects of plants and plant extracts on antioxidant state, reproductive and lactation performance of sows.

| Breed, feeding time, replicate number, condition of experiment and products | Antioxidant state of sows and piglets | Reproductive and lactation performance | Other effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breed: Landrace × Yorkshire Period: G90 to G114 Product: Pennisetum purpureum (5% to 10%) Replicate number: 150 |

Sow serum (G100): ↓ MDA; ↑ T-AOC, T-SOD, CAT, serum equol Sow serum (G114): ↑ T- AOC, T-SOD, CAT, serum equol; ↓ MDA |

Sow serum (G100): ↑IgA, IgG, IgM Microbes: modify gut microbiota of sows on d 100 of gestation especially increase the abundance of Coriobacteriaceae |

Huang et al., 2021, Huang et al., 2021 | |

| Breed: (♀ Large White × Hybrid (Large White × Pietrain) × ♂ Talent, mainly Duroc) Period: G104 to L21 Product: hemp seed (G104 to 114, 2%), (L1 to L21, 5%) Replicate number: 5 sows/group, 8 piglets/group |

Sow serum (farrowing): ↑TAC; ↓TBARS Sow serum (L7): ↓ROS, TBARS; ↑TAC Sow serum (L21): ↑CAT, SOD, GSH-Px Piglet serum (farrowing): ↑TAC, NO, CAT, SOD Piglet serum (L7): ↓TBARS; ↑TAC, SOD Piglet serum (L21): ↓TBARS, GSH-Px |

Mihai et al. (2019) | ||

| Breed: Landrace backup sows Period: G100 to G114 Product: Moringa oleifera (8%) Replicate number: 15 sows/group |

Sow serum (G60): ↑T-AOC, CAT Sow serum (G90): ↑T-AOC; ↓MDA Sow serum (L10): ↑T-AOC, GSH-Px; ↓MDA Piglet serum (weaning): ↑CAT |

Reproduction: ↓stillborn, farrowing length; ↑colostrum protein | Sun et al. (2020) | |

| Breed: Landrace × large white Period: G85 to L21 Product: enzymatically-treated Artemisia annua L. (EA) at 1.0 g/kg Replicate number: 45 sows/group Experimental condition: Sows in the control group were housed at control rooms with temperature 27.12 ± 0.18 °C and temperature-humidity index (THI) 70.90 ± 0.80. Sows in the heat stress + EA groups fed 1.0 g/kg EA, and reared at heat stress rooms (temperature: 30.11 ± 0.16 °C, THI: 72.70 ± 0.60). |

Sow serum (G114): ↓MDA; ↑T-AOC, SOD Sow serum (L14): ↓MDA; ↑T-AOC Sow serum (L21): ↑T-AOC Piglet serum (L0): ↑T-AOC, T-SOD; ↓MDA Piglet serum (L21): ↑T-AOC |

Reproduction: ↑litter weight, individual piglet weight Colostrum: ↑yield, T-AOC, T-SOD; ↓MDA Milk (L14): ↑T- AOC, SOD |

Wenfei et al. (2020) | |

| Breed: Large White Period: G1 to G114 Product: Konjac flour (2.2%) Replicate number: 25 sows/group |

Sow serum (L1): ↓8-OHdG, ROS; ↑GSH-Px Sow serum (L3): ↓ROS |

Sow (G109): ↓HOMA-IR; ↑HOMA-IS Sow (L3): ↓HOMA-IR, TNF-α; ↑HOMA-IS |

Tan et al. (2016) | |

| Breed: Landrace × Yorkshire sows Period: G108 to weaning Product: Silymarin (40 g/day) Replicate number: 55 sows/group |

Sow serum (L18): ↑CAT Sow serum (L7): ↑GSH-Px |

Reproduction: ↓farrowing duration; ↑ADFI during lactation, average piglet birth weight Colostrum: ↑yield, Lactose Milk (L18): ↑protein, urea |

Sow serum (L7): ↓TNF-α, TBA; ↑PRL | Xiaojun et al. (2020) |

| Breed: Landrace × Yorkshire Period: G80 to G109 Product: Inulin (1.6%) Replicate number: 44 sows/group |

Sow serum (farrowing): ↑T- AOC, T-SOD, GSH-Px | Reproduction: ↑sow ADFI, piglet BW at birth, piglet ADG, piglet BW at weaning, weaning survival rate; ↓farrowing duration, the rate of dead fetuses | Sow serum (farrowing): ↑TC, FFA | Li et al. (2020) |

| Breed: Yorkshire (average parity 4.4) Period: 20 d after breeding to weaning Product: Resveratrol (300 mg/kg) Replicate number: 20 sows/group |

Finishing pigs (longissimus thoracis): ↑SOD, mRNA expression of SOD2; ↓MDA | Finishing pigs: ↑Backfat thickness | Meng et al. (2020) | |

| Breed: Landrace × Yorkshire Period: during gestation and lactation Product: Phytogenic actives (1 g/kg) Replicate number: 27 sows/group |

Sow serum (G35): ↑CAT, TBARS, NO, TAC; ↓SOD Piglet plasma (at birth): ↑CAT, TBARS Piglet plasma (postweaning d 7): ↑SOD, GSH-Px Piglet plasma (L20): ↑CAT, SOD |

Colostrum: ↑protein Milk (L20): ↑Fat |

Suckling pigs (on the 20th day) Expression of ↓CLDN4, ANPEP; ↑IL-10, IDO |

David et al. (2020) |

| Breed: Yorkshire × Landrace Period: G107 to weaning Product: soybean isoflavone (SI) and astragalus polysaccharide mixture (APS) (200 mg/kg) (SI:APS = 1:5) Replicate number: 13 sows/group |

Sow serum (L1): ↑IGF-1, PRL, GH, SOD, T-AOC, GSH-Px; ↓MDA Sow serum (L10): ↑IGF-1, PRL, GH, CAT, SOD, T-AOC, GSH-Px; ↓MDA |

↑Sow ADFI, total lactation yield | Sow serum (L10): ↑IL-2, TNF-α, IgG, IgA Sow serum (L21): ↑IL-2, TNF-α, IgG, IgA |

Hongzhi et al. (2021) |

| Breed: Large White × Landrace Period: G80 to L21 Product: grape seed polyphenols (200 to 300 mg/kg) Replicate number: 16 sows/group |

Sow serum (G110): ↑SOD, T-AOC, GSH-Px; ↓MDA | Reproduction: ↓fetal death rate; ↑farrowing survival, preweaning survivability | Sow serum (G110): ↑IgG, IgM, progesterone, estradiol | Wang et al. (2019) |

| Breed: Large White × Landrace Period: G85 to parturition Product: chitosan oligosaccharide (30 mg/kg) Replicate number: 8 sows/group |

Sow serum (G110): ↑SOD, GSH-Px; ↓MDA Sow placenta: ↑expression of Cuznsod, CAT (1 to 2) |

Sow placenta: expression of ↓IL-6, IL-8; ↑VEGF-A | Xie et al. (2016) | |

| Breed: Landrace × Yorkshire Period: G1 to weaning Product: inulin (1.5%) Replicate number: 15 sows/group |

Sow serum (G90): ↑SOD; ↓MDA Sow serum (L0): ↑GSH-Px; ↓MDA Sow serum (L21): ↑SOD, GSH-Px; ↓MDA Piglet plasma (at birth): ↑GSH-Px; ↓MDA Piglet plasma (at weaning): ↑SOD; ↓MDA |

↓Within-litter birth weight coefficient of variation | ↓Sow BW gain during gestation, lactation BW loss | Wang et al. (2016) |

| Breed: Landrace × Large White Period: mating to G40 Product: Catechins (200 mg/kg) Replicate number: 12 sows/group |

Sow serum (Farrowing): ↑CAT, SOD; ↓MDA, H2O2 | Reproduction: ↑the number of piglets born alive, piglet born healthy; ↓stillborn | Fan et al. (2015) | |

| Breed: Yorkshire × Landrace Period: G85 to L18 Product: glycitein (15, 30, or 45 mg/kg; 45 mg/kg is the best) Replicate number: 56 sows/group Experimental condition: The experiment was conducted between July and October 2012, when monthly averages for maximum and minimum temperature (°C) were (33, 25), (33, 25), (31, 23), and (29, 21). |

Sow serum (L1): ↑SOD, T-AOC; ↓MDA | Reproduction: ↑weaned BW per litter, ADG of piglets at lactation period Colostrum: ↑SOD, GSH-Px; ↓MDA Milk(D7): ↑SOD, GSH-Px, fat, protein; ↓MDA |

Hu et al. (2015) | |

| Breed: Large white Period: gestation and lactation Product: oregano essential oil (15 mg/kg) Replicate number: 30 sows/group |

Sow serum: ↑GSH-Px on G60; ↓8-OHdG on G90 Sow serum (L1): ↑GSH-Px; ↓TBARS, 8-OHdG, ROS |

Reproduction: ↑piglet mean BW at d 21, ↑piglet ADG during lactation | Sow faeces bacterial counts (G109): ↓Escherichia coli, Enterococcus; ↑Lactobacillus |

Tan et al., 2015, Tan et al., 2015 |

G = gestation day; L = lactation day; MDA = malondialdehyde; T-AOC = total antioxidant capacity; T-SOD = total superoxide dismutase; CAT = catalase; GSH-Px = glutathione peroxidase; 8-OHdG = 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine; HOMA-IR = insulin resistance; HOMA-IS = insulin secretion index; TNF-α = tumor necrosis factor-α; TC = total cholesterol; FFA = free fatty acid; CLDN4 = recombinant claudin 4; ANPEP = alanyl aminopeptidase; IL-10 = interleukin 10; IDO = indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1; IGF-1 = insulin like growth factor 1; PRL = prolactin; GH = growth hormone; IL-2 = interleukin 2; IgG = immunoglobulin G; IgA = immunoglobulin A; GSH-Px 3 = glutathione peroxidase 3; VEGF-A = vascular endothelial growth factor A; TBARS = thiobarbituric acid reactive substances; BW = body weight.

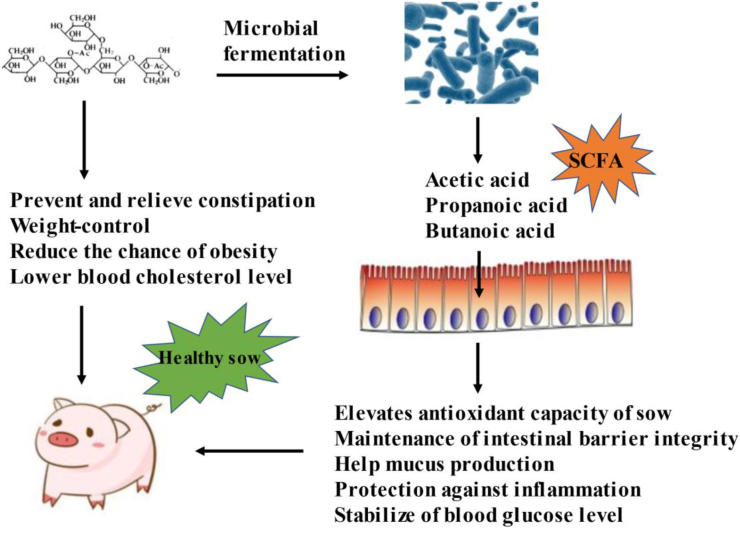

2.1. Plant-derived fiber

The composition and structure of intestinal microorganisms undergo profound changes during pregnancy (Koren et al., 2012). Plant-derived fiber affects the diversity of the intestinal microbial community and plays an active role in maintaining intestinal health (Fig. 4). Adding Pennisetum (5% to 10%) increases the concentration of serum equol and elevates the antioxidant capacity and immune function of sows in late pregnancy by modifying the gut microbiota (increasing the abundance of Coriobacteriaceae) (Huang et al., 2021, Huang et al., 2021). In addition, higher activities of GSH-Px and insulin secretion index sensitivity in the serum of sows and lower concentrations of ROS and 8-hydroxy-2 deoxyguanosine were observed when sows were fed 2.2% konjac flour compared with the control (Tan et al., 2016). Konjac flour mainly contains konjac glucomannan (Chen et al., 2006), which has been shown to alter the fecal microbiota composition of sows (Tan et al., 2015, Tan et al., 2015) and to increase the plasma concentration of total short-chain fatty acids (SCFA). SCFA regulate insulin sensitivity by reducing fatty acid flow (Fernandes et al., 2011) and increasing fetal birth weight (Anderson et al., 2009). In addition, SCFA play an important role in the fermentation of equol (Decroos et al., 2005). These findings may partially explain why fiber regulates oxidative stress. Consistent with these findings, direct supplementation with inulin (a soluble fiber) also regulates the antioxidant capacity. Adding 1.6% inulin to sow feed from 80 to 109 days of pregnancy can increase the serum total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC), total superoxide dismutase (T-SOD), and GSH-Px activities of sows, leading to an optimal sow oxidative status. The concentrations of free fatty acid and total cholesterol in the serum of the sows fed inulin were also higher than those of the control group, indicating that the sow fed inulin had enhanced fat mobilization ability during delivery (Li et al., 2020), which could provide energy for sow delivery, thus shortening the delivery time and improving the birth survival rate of piglets. Chitosan oligosaccharide is another natural polysaccharide with good water solubility and can be used as an immunostimulant, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant (Xiong et al., 2014). Dietary chitosan oligosaccharide supplementation (30 mg/kg) in sows may promote placental nutrient transport by activating the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway, protect sows from oxidative stress and reduce inflammatory factors in serum (Xie et al., 2016).

Fig. 4.

The crude fiber is beneficial to health of sows. The fee rich in crude fiber can improve that body condition of the sow, improve the reproductive performance of the sow, and effectively solve the problem of constipation of pregnant sows and less lactation after delivery. Furthermore, short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) are the main metabolites produced by the microbiota in the large intestine through the anaerobic fermentation of dietary fiber and resistant starch, which help maintain that integrity of the intestinal barrier mucus production, prevent inflammation, etc.

It worth noting that soluble fiber seems to deliver more antioxidant capacity than insoluble fiber. A large part of soluble fiber belongs to functional oligosaccharide. On one hand, soluble fiber adsorbs harmful microorganisms to reduce their colonization in the intestinal mucosa (Sweeney et al., 2012). On the other hand, soluble fiber could also be fermented by microorganisms in the hindgut to generate SCFA (acetate, propionate, and butyrate), which not only directly provide nutrition for intestinal cells, but also improve the intestinal morphology and integrity. More importantly, SCFA (especially butyrate) can alleviate oxidative stress. Butyrate protects against H2O2-induced DNA damage in rat or human colitis cells (Toden et al., 2007; Rosignoli et al., 2001). Besides, acetic acid and butyric acid esters were proved to inhibit the oxidative stress of mesangial cells induced by high glucose and lipopolysaccharide (Huang et al., 2017). Mechanistically, SCFA could exert antioxidant functions by regulating oxidoreductases (Knapp et al., 2013; Ebert et al., 2003; Yano and Tierney, 1989). For example, butyric acid enhanced glutathione-s-transferase activity in human colon cancer HT-29 cells (Ebert et al., 2003) and CAT activity in rat arterial smooth muscle cells (Yano and Tierney, 1989). Moreover, nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 (Nrf2), a critical transcription factor to protect against oxidative stress, is also a target for butyric acid (Wang et al., 2020).

2.2. Plant-derived antioxidants

Some plants are rich in antioxidants, including phenols, flavonoids, proanthocyanidins, flavonols, vitamin C, vitamin E, beta-carotene, zinc, and selenium, which have been shown to have antioxidant potential (Jain et al., 2008). Feeding sows diets containing plant-derived natural bioactive compounds (1 g/kg) during gestation and lactation improved the protein concentration in colostrum and increased the resistance of milk to Bacillus subtilis and Staphylococcus aureus. In addition, the antioxidant status of sows is enhanced, with effects such as significant elevations of GSH-Px and SOD in the serum (Reyes-Camacho et al., 2020). Among these antioxidants, polyphenol is the most common substances and a well-known natural antioxidant in plants. Polyphenols are derived from flowers, vegetables, fruits, essential oils and tea (Zhang et al., 2016). Their antioxidant effect is comparable to that of vitamin E (Iqbal et al., 2015). A previous study showed that adding glucose polyphenols (200 to 300 mg/kg) from the 85th day of gestation to delivery improved reproductive performance, increased serum progesterone and estradiol levels and elevated the contents of IgM and IgG in the colostrum of sows, which could lead to an increase in the survival rate of piglets before weaning. In addition, malondialdehyde (MDA) levels were decreased and GSH-Px and T-AOC levels were increased when sows were treated with glucose polyphenols (Wang et al., 2019). Similarly, catechin, a plant polyphenol component, was also reported as an antioxidant plant extract (Uzun et al., 2010). Supplementation of the feed of pregnant sows with catechin (200 mg/kg) enhanced their antioxidant capacity and reproductive performance (Fan et al., 2015). Oregano essential oil, which is separated from oregano, is mainly composed of carvacrol and thymol (Sivropoulou et al., 1996). On the one hand, the structure of sow intestinal microbes was found to be altered with the oregano essential oil diet (OEO) (15 mg/kg), with an increased number of Lactobacilli in sow feces and decreased the numbers of Enterococcus and Escherichia coli. On the other hand, feeding OEO was shown to increase the insulin sensitivity of sows, thus increasing the feed intake of sows during lactation. Besides OEO diet significantly reduced sow serum thiobarbituric acid reactive substances and 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine concentrations after delivery (Tan et al., 2015, Tan et al., 2015). Soybean isoflavone is a type of polyphenol that is also a natural active phytoestrogen (Moon et al., 2006). It has a similar structure to mammalian estrogen (Yuan et al., 2012), which promotes the testosterone and prolactin secretion of lactating sows and increases lactation yield. The addition of the mixture of soybean isoflavone and astragalus polysaccharide (200 mg/kg) to sow feed improved the serum prolactin, growth hormone and Insulin-like growth factor 1 contents of lactating sows, resulting in increased sow lactation. At the same time, this mixture increased the serum antioxidant levels of sows with increasing serum SOD and GSH-Px contents during lactation (Wu et al., 2021). Silymarin extracted from Silybum marianum plants contains various flavonoids (silybin as the main component), which have antioxidation, liver protection, blood lipid reduction, blood pressure reduction, anti-diabetes and anti-obesity functions (Surai, 2015). Silymarin supplementation (40 g/day) during late pregnancy and lactation in sows was found to increase circulating concentrations of serum prolactin, reduce oxidative stress (elevated serum composition of CAT and GSH-Px during lactation) and reduce insulin resistance and inflammatory responses (decreases in tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-1 β, as well as increase feed intake in sows, resulting in the improved growth performance of their offspring (Jiang et al., 2020). This might be because silymarin prevents the formation of free radicals by activating some nonenzymatic antioxidants and antioxidant enzymes through the Nrf2 and nuclear factor-kB (NF-kB) pathways (Surai, 2015).

In addition to directly using polyphenols, feeding sows with plant-enriched polyphenols also alleviates their oxidative stress. A recent study showed that the addition of Moringa oleifera (8%) improved the reproductive performance of sows and had positive impacts on the serum antioxidant indexes of sows and piglets, such as significant increases in serum T-AOC at 60 and 90 days in pregnant sows. In addition, the addition of M. oleifera was shown to significantly increase the protein level in colostrum (Sun et al., 2020). M. oleifera contains phenol and other effective antioxidant substances, which could alleviate oxidative stress in animals (Osman et al., 2012). Therefore, we speculated that the antioxidant effect of M. oleifera is partially derived from its antioxidant substances. Similarly, dietary supplementation of enzymatically treated Artemisia annua L. at 1.0 g/kg was shown to result in significant elevations in the serum T-AOC levels of sows and piglets during pregnancy and lactation, and the serum MDA level was found to be decreased. In addition, enzymatically treated Artemisia annua L. was found to promote the intestinal barrier integrity of piglets (Zhang et al., 2020, Zhang et al., 2020, Zhang et al., 2020). The beneficial effect of Artemisia annua L supplementation might be due to its enrichment in sesquiterpenes (artemisinin), volatile oils, alkaloid phenols and flavonoids (Zhang et al., 2020, Zhang et al., 2020, Zhang et al., 2020), which can resist oxidation and enhance immunity (Ferreira et al., 2010). Hemp seeds are rich in polyphenols, polyunsaturated fatty acids, and other bioactive compounds (Callaway, 2004). Supplementing hemp seeds (2% to 5%) in the late pregnancy and lactation stages of sows was found to effectively reduce the levels of serum thiobarbituric acid reactive substances of sows and piglets and increase the levels of antioxidant enzymes such as total antioxidant capacity (TAC) and SOD (Palade et al., 2019).

In summary, plant-derived feed rich in polyphenols (such as M. oleifera, Artemia annua L. and hemp seeds) have been shown to be effective in improving the antioxidant capacity of sows. However, the direct addition of plants usually has low active ingredients. Direct addition of high-dose plant active ingredients (such as grape polyphenols, catechin, silymarin, oregano essential oil and soybean isoflavones) might produce better results. Compared with administration with an extract of polyphenols, feeding sows additives enriched in fiber or polysaccharides (such as pennisetum, konjac flour, chitosan oligosaccharide and inulin) might play a more prominent role in regulating the structure of the intestinal flora of sows, maintaining intestinal health, and reducing constipation.

3. Selenium and vitamin E

Selenium is a necessary micronutrient for animals, which is proposed to maintain growth, support muscle activity, promote reproductive organ development, and regulate the immune system (Schwarz et al., 2009; Tóth et al., 2018). Both inorganic selenium, such as selenite or selenate, and organic selenium, such as yeast selenium or DL-selenomethionine (Se-Met), are used as selenium supplements in animal husbandry. With the advancement of research, it has been gradually recognized that there are some limitations for the use of inorganic selenium. Firstly, compared with organic selenium, inorganic selenium is less efficiently retained, and most of which are excreted via the urine. Pharmacokinetic studies showed that the absorption rate of Se-Met (98%) was superior to that of sodium selenite (84%). In addition, excretion of Se-Met (15%) was lower than that of sodium selenite (35%) (Duntas et al., 2014). Blodgett et al. (1989) reported a sevenfold increase in sodium selenite levels in sow feed only resulted in modest increases in selenium concentrations in blood and colostrum. In addition, inorganic selenium easily interacts with other minerals to reduce their absorption efficiency (Surai, 2006).

The addition of organic selenium has beneficial effects on pregnant sows and their offspring. For example, addition of selenium (1 mg/kg organic Se) was found to increase the concentrations of serum GSH-Px, SOD, GSH and T-AOC in sows during lactation, reflecting that the sow is in a good antioxidant state at this stage. In addition, the antioxidant properties and nutrient content of milk were also shown to be improved (Zhang et al., 2020, Zhang et al., 2020, Zhang et al., 2020). Similarly, sow fed Se-enriched yeast (0.3 Se mg/kg diet) were shown to have improved antioxidant capacity in the serum and milk of sows compared with sows fed inorganic selenium (Chen et al., 2016). Collectively, there were two main benefits of organic selenium for pregnant sows (Table 2). First, organic selenium can build up a reserve of selenium in the form of Se-Met in tissues, mainly muscles, that can be used under stress conditions to improve antioxidant defense (Surai, 2006). Second, organic selenium in the form of Se-Met can efficiently transport selenium from sows to fetuses and newborn piglets via placenta, colostrum, and milk (Stewart et al., 2013).

Table 2.

Effects of selenium, vitamin E, vitamin C and yeast culture on antioxidant state, reproductive and lactation performance of sows.

| Breed, feeding time, replicate number, condition of experiment and products | Antioxidant state of sows and piglets | Reproductive and lactation performance | Other effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period: Piglets: birth to 38 d of age Sow: (G84 to weaning) Product: Se-Met 0.26 and 0.43 mg Se/kg Or Na–Se 0.40 and 0.60 mg Se/kg Replicate number: 31 sows/group |

Piglet plasma (Se-Met groups) ↑GSH-Px 3 at birth and d 5 after parturition |

Reproduction: ↑piglet body weight (Se-Met groups at d 24) | Se-Met-groups at d 38 ↑Se-concentrations in plasma and had a dose–response effect |

Falk et al. (2020) |

| Breed: Landrace × Yorkshire Period: G85 to L35 Product: yeast culture (YC) and organic selenium (Se), 10 g/kg YC + organic Se (1 mg/kg Se) Replicate number: 40 sows/group |

Sow serum (L1): ↑SOD, T-AOC, GSH Sow serum (L25): ↑GSH-PX |

Colostrum: ↑GSH-Px, T-SOD; ↓MDA Milk (d 4): ↑fat |

Zhang et al., 2020, Zhang et al., 2020, Zhang et al., 2020 | |

| Period: G90 to weaning Product: only vitamin E or vitamin E and Proviox polyphenols Gestation diets: Proviox polyphenols (50 mg/kg), vitamin E (50 mg/kg) Lactation diets: Proviox polyphenols (75 mg/kg), vitamin E (75 mg/kg) Replicate number: 13 sows/group |

Sow serum (Farrowing): ↑GSH-Px, T-SOD, TAS Sow serum (Weaning): ↑GSH-Px, T-SOD, TAS Piglet serum (d 21 of age): ↑GSH-Px, T-SOD, TAS |

Reproduction: ↑litter weight at birth and weaning | Piglet serum (d 21 of age): ↑α-Tocopherol, retinol | Lipiński et al. (2019) |

| Breed: Yorkshire mixed-parity sows Period: G85 to L21 Product: N-carbamylglutamate and vitamin C (both 0.05%) Replicate number: 13 sows/group |

Sow serum (weaning): ↓MDA | Reproduction: ↑initial litter weight, average birth weight, weaning litter weight, average weaning weight | Sow: ↓Respiration; ↑teed intake Sow serum (weaning): ↑blood IgG |

Feng et al. (2017) |

| Breed: Large White × Landrace Period: G107 to L21 Product: vitamin E (250 IU/kg) Replicate number: 24 sows/group |

Piglet serum (L21): ↑T-AOC, CAT | Reproduction: ↑piglet weight at weaning, d 0 to21 ADG Colostrum: ↑tocopherol, fat, IgG, IgA Milk: ↑tocopherol, fat, IgG, IgA |

Piglet serum (L21): ↑tocopherol, IgG, IgA Sow serum (At parturition): ↑tocopherol, IgG, IgA Sow serum (L21): ↑tocopherol, IgG, IgA |

Lin et al. (2017) |

| Period: G21 to weaning Product: selenium (0.30 mg/kg) and vitamin E (90 IU/kg) Replicate number: 60 sows/group |

Sow serum (60-d post-coitus): ↑T-AOC, SOD Sow serum (11-d postpartum): ↑T-AOC, SOD, GSH-Px, GSH; ↓MDA |

Colostrum: ↑T-AOC, SOD, GSH-Px, GSH; ↓MDA Milk (d 11): ↑T-AOC, SOD, GSH-Px, GSH; ↓MDA |

Chen et al. (2016) | |

| Breed: Landrace × Yorkshire Period: G85 to L35 Product: yeast culture (10 g/kg) + organic Se (1 mg/kg). Replicate number: 40 sows/group |

Sow serum (d 1 postpartum): ↑T- AOC, T-SOD, GSH Sow serum (d 25 postpartum): ↑GSH-Px |

Colostrum: ↑T-SOD, GSH-Px; ↓MDA Milk (d 4): ↑fat |

Zhang et al., 2020, Zhang et al., 2020, Zhang et al., 2020 |

G = gestation day; L = lactation day; MDA = malondialdehyde; T- AOC = total antioxidant capacity; T-SOD = total superoxide dismutase; CAT = catalase; GSH-Px 3 = glutathione peroxidase 3; GSH = glutathione; IgA = immunoglobulin A.

It worth noting that even though Pig Nutrition Requirement (National Research Council, 2012) recommends 0.15 mg/kg selenium in feed for pregnant and lactating sows, the optimal level of selenium in sow feed is still controversial. Some scientists found selenium supplementation beyond the prescribed dose can interfere with insulin homeostasis and thus negatively affect pig performance (Pinto et al., 2012). However, high dose selenium supplementation (above the upper limit of 0.5 mg/kg of selenium according to Chinese standards) has also been reported to have beneficial effects on animals (Meyer et al., 2011; Chauhan et al., 2014; Stewart et al., 2013). We speculated that this might be due to the partial transfer of selenium to piglets through the placenta, which not only reduced the accumulation of selenium in sows, but also had a beneficial effect on piglets. The optimum level of selenium addition still needs to be further studied.

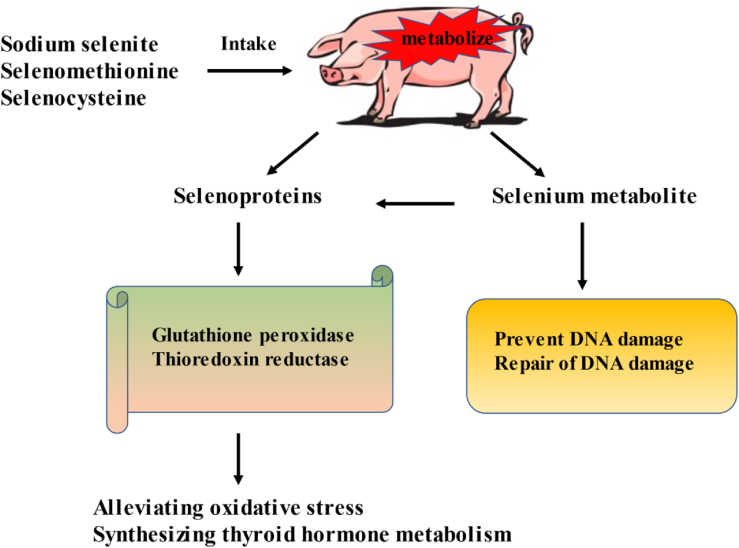

At the molecular level, according to previous studies, selenium is metabolized into various small molecular weight seleno-compounds, such as hydrogen selenide and methylated selenium compounds, that affect cellular processes such as DNA repair and epigenetics (Grealish et al., 2000; Bera et al., 2013). Among them, hydrogen selenide ultimately synthesizes various selenoproteins through a series of complex biochemical reactions. The common selenoproteins are glutathione peroxidase and thioredoxin reductase, which are involved in alleviating oxidative damage and synthesizing thyroid hormone metabolism, respectively (Hoffmann, 2007) (Fig. 5). In view of these results, the addition of selenium to sow feed is beneficial and could improve the antioxidant capacity of the sow. The biological value of the organic form of selenium is much higher, and 1 mg/kg organic selenium is recommended for sows.

Fig. 5.

Nutrition function of selenium. The selenium in the feed is absorbed by the sows and metabolized to produce small molecular weight seleno-compounds and some others participate in the synthesis of selenoprotein, thereby improving the antioxidant performance of the sows, regulating the energy metabolism of the sows, and reducing cell DNA damage.

Vitamin E is an effective antioxidant present in the cell membrane that maintains the normal function of cells by capturing free radicals and their oxidizing substances (Halliwell, 2012), counteracting lipid peroxidation in cells. From the 107 d of gestation to 21 d of lactation, adding 250 IU/kg vitamin E to sows' diets was found to significantly improve the weaning weight of piglets, stimulate the activity of antioxidant enzymes in the red blood cells of sows, and significantly affect the nutrient composition and immunoglobulin level of colostrum (Wang et al., 2017). Similarly, sows fed vitamin E and polyphenols were shown to have improved antioxidant status, higher GSH-Px and SOD activities, and upregulated serum retinol levels (Lipinski et al., 2019). It is worth noting that when sows were fed a low dose of vitamin E (90 or 30 IU/kg), their antioxidant status and reproductive performance did not appear to be improved (Chen et al., 2016). Therefore, this evidence indicates that adding sufficient vitamin E to sows’ diets during late pregnancy can alleviate the oxidative stress state and that its effect is closely related to the dosage. The recommended amount of vitamin E for sows is (150 to 250 IU/kg). Similar to vitamin E, as an important antioxidant, vitamin C helps remove excess ROS from the body. The combined addition of N-carbamylglutamate and vitamin C reduces the levels of malondialdehyde and cortisol in sow serum and increases the level of IgG (Feng et al., 2017). In terms of reproduction, previous researchers have reported that the reproductive performance of sows fed vitamin E or vitamin C was significantly affected by the duration of supplementation. For example, short-term vitamin E or C supplementation to peripartum sows does not affect reproductive performance such as litter size, birth weight and number of stillbirths (Sosnowska et al., 2011; Mahan et al., 2000). In contrast, vitamin E and vitamin C supplementation significantly improved sow reproductive performance when tested during extended periods of gestation (Mavromatis et al., 1999; Lechowski et al., 2016). Mechanistically, vitamin C supplementation resulted in elevated plasma levels of β-estradiol that favored reproductive organ development (Coffey et al., 1993). In addition, decreased body fat consumption in lactating sows after vitamin C supplementation indicated that vitamin C helped maintain a stable level of body weight and backfat thickness, thereby reducing metabolic stress in lactating sows (Kolb et al., 2001; Zhao et al., 2002).

4. Microbial additives

Probiotics produce a favorable response in the host by improving the microbial balance in the intestine (Afrc, 1989). They promote or inhibit the growth of certain intestinal microorganisms and thus have a beneficial effect on the host (Table 3). Recent studies have reported that the perinatal intestinal flora of sows is associated with oxidative stress (Hayakawa et al., 2016). Clostridium butyricum regulates the balance of intestinal microecology, promoting the reproduction of bifidobacteria and inhibiting the proliferation of E. coli. It is worth noting that probiotics have been reported to improve the antioxidant capacity of sows and piglets (Xie et al., 2016).

Table 3.

Effects of microbial additive on antioxidant state, reproductive and lactation performance of sows.

| Breed, feeding time, replicate number, condition of experiment and products | Antioxidant state of sows and piglets | Reproductive and lactation performance | Other effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breed: Large White sows Period: G85 to L21 Product: dietary yeast extract (10 g/kg) Replicate number: 20 sows/group |

Decrease oxidative stress of weaned piglets | Reproduction: ↑ADFI of sows on L1, the number of weaned piglets per litter | The concentration of 5′-monophosphate nucleotides and total nucleotides in milk increased linearly with the increase of yeast extract in diet | Cqta et al. (2021) |

| Breed: Landrace × Yorkshire Period: G90 to L21 Product: Bacillus subtilis PB6 (4 × 108 CFU/kg) Replicate number: 16 sows/group |

Sow serum (parturition): ↑T-AOC; ↓MDA Sow serum (L21): ↑CAT Piglet serum: ↓Cortisol concentrations |

Reproduction: During lactation: ↑born alive rate, litter weight gain, piglet survival rate Farrowing: ↓duration of farrowing, piglet birth interval Colostrum: ↑fat |

Sow serum: ↓Endotoxin on L14 and L21 | Zhang et al., 2020, Zhang et al., 2020, Zhang et al., 2020 |

| Breed: Large White × Landrace Period: G1 to Weaning Product: isomaltooligosaccharide and Bacillus Replicate number: 26 sows/group |

Sow placental: ↓MDA, GSH-Px, CAT; ↑T-AOC | Reproduction: ↑average piglet BW, placental efficiency | Umbilical venous serum: ↑INS, IgG, GH; ↓IgM | Gu et al. (2019) |

| Breed: Landrace × York Period: G90 to L21 Product: Clostridium butyricum (0.2% to 0.4% and 0.4% is better) Replicate number: 45 sows/group |

Sow serum (at parturition): ↓MDA Sow serum (L14): ↓MDA; ↑T- AOC, T-SOD Sow serum (L21): ↑CAT; ↓GSH-Px, Endotoxin Piglet serum (L14): ↓MDA, Endotoxin, Cortisol; ↑T- AOC Piglet serum (L21): ↑T- AOC; ↓Endotoxin, Cortisol |

Reproduction: ↑litter weight gain; ↓duration of farrowing, estrous interval Colostrum: ↑protein, IgM Milk: ↑protein, IgM |

Clostridium butyricum 0.2% increased the relative abundance of Bacteroides, but decreased the relative abundance of Proteus, Bifidobacterium, Actinomycetes, Acid Bacteria, Verrucous Microorganism and Mycelia/Bacteroides. | Cao et al. (2019) |

G = gestation day; L = lactation day; MDA = malondialdehyde; T- AOC = total antioxidant capacity; T-SOD = total superoxide dismutase; CAT = catalase; GSH-Px = glutathione peroxidase; IgM = immunoglobulin M; IgG = immunoglobulin G; INS = serum insulin.

Yeast and yeast extracts have been widely used in animal husbandry. Yeast extract contains nucleotides, vitamins, and β-glucans (Vieira et al., 2016), which might be beneficial to pig growth, metabolism, and health. Previous studies have shown that 5′-inosinate disodium enhances the flavor and palatability of feed. Yeast cell wall components (e.g., mannan and β-glucan) inhibit the growth of porcine intestinal pathogenic microorganisms to improve their growth performance by improving intestinal health (Shen et al., 2009). The sows provided with yeast derivatives (2 g/kg) is found to have more beneficial microbes (Roseburia, Parprevotella, Eubacterium), and less opportunistic pathogens (Proteus, Vibrio desulfurization, E. coli, and Helicobacter) in their feces (Shah et al., 2018). Adding 10 g/kg yeast extract to the sows' diets increases their feed intake during lactation and the number of weaned piglets per litter and reduces the oxidative stress of weaned piglets (Cqta et al., 2021). In addition, the serum T-AOC and GSH-Px of weaned piglets were higher than those of the control, while the blood thiobarbituric acid reactive substances level was decreased (Tan et al., 2021). Another study found that the addition of yeast extract (10 g/kg) and selenium to sows' diets increased the neonatal weight and the average daily gain during the lactation period of piglets. In addition, the contents of SOD and GSH-Px in colostrum were also increased, accompanied by a decrease in MDA (Zhang et al., 2020, Zhang et al., 2020, Zhang et al., 2020). Similarly, serum antioxidant enzyme activities, especially glutathione peroxidase, were significantly higher in weaned piglets when fed directly with 4% yeast-derived protein than in control-fed piglets (Liang et al., 2014).

B. subtilis can be used as growth promoter. It inhibits the reproduction of pathogens and promotes the degradation of nutrients in feed, thereby improving the utilization rate of feed. When B. subtilis (4 × 108 CFU/kg) was added to sows’ daily rations, they exhibited better physical strength during delivery, and the birth interval of the piglets was shortened (Zhang et al., 2020, Zhang et al., 2020, Zhang et al., 2020). Concentrations of MDA, endotoxin in sow serum and cortisol in piglet serum were also found to be reduced (Zhang et al., 2020, Zhang et al., 2020, Zhang et al., 2020). Another study showed that the combination of isomaltooligosaccharide and B. subtilis increased the growth hormone (GH) concentration in umbilical vein serum, increased the concentration of placental T-AOC and reduced the concentration of MDA, thus improving the placental efficiency of sows (Gu et al., 2019). B. subtilis (2 × 109 CFU/kg) cultures have also been reported to be effective in attenuating zearalenone-induced oxidative stress (ameliorating serum SOD, and MDA levels) and organ apoptosis in pregnant sows (Zhou et al., 2020). Compared with other economic animals, the pigs are more vulnerable to the influence of deoxynivalenol (DON), and the pig fed with the DON (4 mg/kg) polluted feed showed the activity of inhibiting SOD, GSH-Px, GSH and T-AOC (Liao et al., 2020). However, these DON-induced oxidative stresses were partially counteracted by the administration of sow B. subtilis ASAG 216 (1 × 108, 0.1%), as evidenced by increased serum GSH-Px and SOD activities and decreased MDA and H2O2 contents (Ru et al., 2021). The addition of 0.2% C. butyricum to sow feed reduced the concentration of MDA in sow serum at delivery and increased the concentration of T-AOC, thereby reducing the time interval to litter. Furthermore, the lactose and protein contents in the milk were increased with the supplementation of 0.2% C. butyricum (Cao et al., 2019).

In summary, probiotic supplementation during pregnancy could regulate the intestinal microbial structure of sows, improve intestinal health, and enhance the antioxidant capacity of sows.

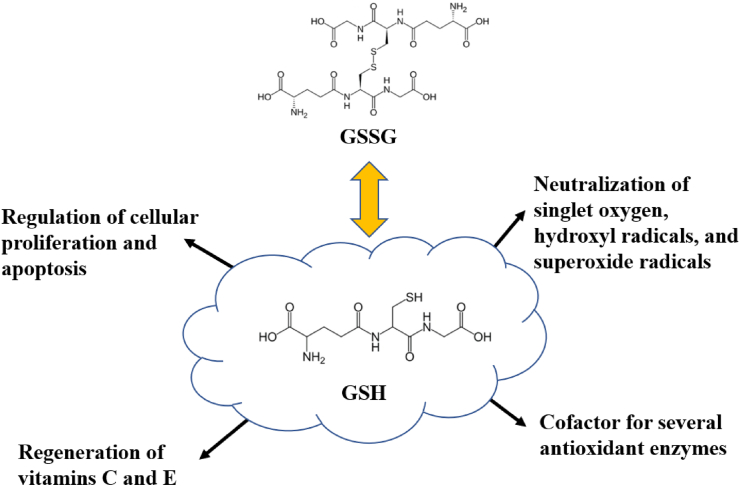

5. Other nutritional strategies

In addition to the nutrients mentioned above, the effects of other additives on the antioxidant performance of sows are summarized in Table 4. Glutathione, a ubiquitous thiol-containing tripeptide made from the amino acids glycine, cysteine, and glutamine acid, plays a pivotal role in reducing oxidative stress (Jefferies et al., 2003). Cysteamine (CS) is a precursor of GSH, which is an important endogenous antioxidant (Fig. 6). Mechanistically, cysteamine promotes the transport of cysteine into cells for GSH synthesis, thereby achieving cell redox homeostasis (Besouw et al., 2013). Dietary CS (100 to 500 mg/kg) supplementation could partially improve the antioxidant status of sows and their offspring, increase the mean birth weight of piglets (from 1.4 to 1.6 kg), and reduce stillbirth (from 12% to 6%) (Huang et al., 2021, Huang et al., 2021). It is also possible to increase GSH levels in the sow's placenta and increase the placental vascular density, which is beneficial to the growth and survival of the embryo (Huang et al., 2021, Huang et al., 2021). The potential mechanisms by which CS protects cells against oxidative stress are listed as follows. First, cysteamine undergoes a sulfhydryl–dithio exchange reaction to eliminate oxidized substances in the cells (Ozaki et al., 2007). Second, cysteamine inhibits the nucleotide-containing pyridine domain in the γ-ribosome to improve the redox state of the maternal placenta (Luo et al., 2019). It is worth noting that high doses of CS could attenuate glutathione peroxidase activity. N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is a similar product to CS. The addition of NAC (500 mg/kg) to the sow diet was also found to significantly reduce serum and placental inflammatory cytokine levels and increase placental NO production and the gene expression levels of vascular endothelial growth factor and hypoxia inducible factor-1α by inhibiting the NOD-like receptor protein 3 inflammasome and to increase the numbers of lactic acid bacteria and bifidobacteria in the sow hindgut (Luo et al., 2019).

Table 4.

Effects of other nutritional strategies on antioxidant state, reproductive and lactation performance of sows.

| Breed, feeding time, replicate number, and products | Antioxidant state of sows and piglets | Reproductive and lactation performance | Other effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breed: Landrace × York sow Period: G85 to L21 Product: cysteamine (100 to 500 mg/kg) of CS, but 100 mg/kg is the best. Replicate number: 21 sows/group |

Sow serum (L0) ↑GSH Sow Placenta (parturition): ↑T-AOC Piglet serum (at birth): ↑GSH |

Colostrum: ↑GSH Reproduction: ↓Stillbirth rates, Invalid piglet rates; ↑Placental efficiency |

Huang et al., 2021, Huang et al., 2021 | |

| Breed: Landrace × Large White Period: G85 to delivery Product: n-acetyl-cysteine (500 mg/kg) Replicate number: 9 sows/group |

Sow serum (parturition): ↑GSH-Px, SOD, T-AOC; ↓H2O2, MDA Sow Placenta (parturition): ↑GSH-Px, NO; ↓SOD, MDA |

Sow serum (at parturition): ↓IL-1β, IL-18 Sow Placenta (at parturition): ↑IGF-1, IGF-2, E-cadherin |

Luo et al. (2019) | |

| Breed: Landrace × Yorkshire Period: G90 to parturition Product: β-carotene (30 or 90 mg/kg but 90 mg/kg is better) Replicate number: 16 sows/group |

Sow serum (parturition): ↑GSH-Px, NO | β-carotene may increase NO production by up-regulating the relative abundance of Corynebacterium | Xupeng et al. (2020) | |

| Breed: Landrace × Large white Period: G1 to L21 Product: L-carnitine at 100 mg/kg from G1 to G90, and 200 mg/kg from G91 to L21. Replicate number: 30 sows/group |

Sow serum (G110): ↑GSH-Px, GSH; ↓MDA Sow serum (L1): ↑T-SOD, GSH-Px, GSH; ↓MDA Sow serum (L21): ↑T-SOD, GSH-Px, GSH; ↓MDA Piglet serum (at birth): ↑T-SOD, GSH-Px, GSH; ↓MDA Piglet serum (Weaning): ↑T-SOD, GSH-Px, GSH; ↓MDA Piglet Liver (Weaning): ↑T-SOD, GSH-Px, GSH; ↓MDA |

Reproduction: ↑Initial litter weight, Average birth weight, Weaning litter weight, Average weaning weight | Wei et al. (2019) | |

| Breed: Landrace × Yorkshire Period: G1 to weaning Product: methyl donor (3 g/kg) Replicate number: 14 sows/group |

Umbilical cord blood (at birth): ↑SOD, CAT, GSH-Px Piglet serum (at birth): ↑SOD, GSH-Px, T-AOC; ↓MDA Piglet Liver (at birth): ↑CAT, GSH-Px, T-AOC |

In chorioallantois (at birth): ↑CAT, GSH-Px, SOD, ASA, NOS | Mou et al. (2018) |

G = gestation day; L = lactation day; MDA = malondialdehyde; T- AOC = total antioxidant capacity; T-SOD = total Superoxide dismutase; CAT = catalase; GSH = glutathione; GSH-Px = glutathione peroxidase; IL-1 β = interleukin-1 β; IL-2 = interleukin 2; IGF-1 = insulin like growth factor 1; IGF-2 = insulin like growth factor 2.

Fig. 6.

Glutathione and its role in cellular functions. GSH = glutathione; GSSG = glutathione oxidized.

Beta-Carotene, a common plant pigment, is generally considered to be the precursor of vitamin A. One study showed that β-carotene (30 or 90 mg/kg) significantly increased serum GSH-Px in sows. In addition, β-carotene may increase NO production by upregulating the relative abundance of Corynebacterium (Yuan et al., 2020). According to previous studies, an increase in homocysteine levels leaded to an increase in ROS levels (Agarwal et al., 2005). Prenatal supplementation with maternal methyl donors (3 g/kg) in sow feed significantly reduced serum homocysteine concentrations in sows at d 35 and 110 of pregnancy. The supplementation increased the activity of antioxidant enzymes such as SOD, CAT and GSH-Px in chorioallantoic acid, piglet plasma, and liver, thereby enhancing maternal, placental, and offspring antioxidant capacity (Mou et al., 2018). The main function of L-carnitine is to help long-chain fatty acids cross the mitochondrial inner membrane for β-oxidative degradation. The results determined in vitro indicated that L-carnitine was an effective antioxidant (Wei et al., 2019). L-Carnitine supplementation (100 to 200 mg/kg) in sow diets increased the survival number and weaning body weight of weaned piglets, decreased plasma MDA levels in sows, and alleviated DDGS-induced oxidative stress in sows (Wei et al., 2019).

6. Conclusions

Further in-depth study on the mechanism of oxidative stress in sows will help us develop more effective additives to reduce losses due to oxidative stress. Based on the current research, we have reached the following conclusions: plant additives rich in polyphenols can effectively alleviate the oxidative stress of sows during the late pregnancy and lactation stages. These additives are probably the most effective antioxidant products available because they are more effective in improving oxidative stress indicators in sows (Table 1). And products with high crude fiber and additives rich in soluble sugar can effectively regulate the structure of the gut microbiota of sows and affect microbial diversity to maintain the intestinal health of sows. For vitamin products (such as vitamin E and vitamin C), a high concentration (>100 IU/kg) is required to exert an efficient antioxidant effect. Microbial preparations tend to promote the growth of beneficial flora. The addition of B. subtilis and C. butyricum has been proven to be effective. It has also been proven to be effective to add some substances involved in body metabolism to the sows’ feed, such as L-carnitine and methyl donors. In addition, the types of additives, the addition stage, and the dosage affect the expected antioxidant function. Therefore, reasonably considering the use of products with different combinations and repeating experiments in production practice are required to identify the most suitable product for specific livestock farms.

7. Outlook

At present, most studies only focus on evaluating the effects of individual additives, and the effects of products with different active components remain to be determined in future studies. In addition, the specific scavenging mechanism of active components in various additives on free radicals is still unclear and remains to be studied. Furthermore, it worth noting that oxidative stress could reduce the lactational feed intake. However, it is still unclear whether nutritional strategies such as increasing nutrient density, and changing the Lys-to-energy ratio could eliminate the negative effects from oxidative stress. As described in this review, MDA is widely used as a marker of lipid oxidation. However, polyphenols and vitamin products could directly react with MDA, which might affect the oxidative stress status of sows. Thus, a better biomarker of oxidative stress might need to be identified in the future. It is interesting to note that most of the additives stimulate the synthesis of antioxidant enzymes in sows, suggesting that their pathway of activating antioxidant enzymes might be similar to that of ROS, which is also worth studying. Currently, the alleviation of sow oxidative stress by nutritional means is mainly focused on improving the concentration of antioxidant substances or the activity of antioxidant enzymes in the sow. However, there are few studies on how to reduce ROS production from the source and repair injuries caused by oxidative stress. Finally, a growing number of studies have shown that appropriate concentrations of ROS play an important role in maintaining animal health. The priority is now to determine the ranges in which ROS levels in sows in the late pregnancy and lactation stages are most beneficial for their productive performance.

Conflict of interest

We declare that we have no financial and personal relationships with other people or organizations that can inappropriately influence our work, there is no professional or other personal interest of any nature or kind in any product, service and/or company that could be construed as influencing the content of this paper.

Acknowledgment

This study was financially supported by National Natural Science Foundation of the P. R. of China (No. 31872364 and No. 31802067) and Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (No. 2021A1515010440).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Association of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine.

Contributor Information

Wutai Guan, Email: wutaiguan1963@163.com.

Shihai Zhang, Email: zhangshihai@scau.edu.cn.

References

- Afrc R.F. Probiotics in man and animals. J Appl Bacteriol. 1989;66:365–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal A., Gupta S., Sharma R.K. Role of oxidative stress in female reproduction. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2005;3:28. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-3-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J.W., Baird P., Davis R.H., Jr., Ferreri S., Knudtson M., Koraym A., et al. Health benefits of dietary fiber. Nutr Rev. 2009;67:188–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2009.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bera S., De Rosa V., Rachidi W., Diamond A.M. Does a role for selenium in DNA damage repair explain apparent controversies in its use in chemoprevention? Mutagenesis. 2013;28:127–134. doi: 10.1093/mutage/ges064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berchieri-Ronchi C.B., Kim S.W., Zhao Y., Correa C.R., Yeum K.J., Ferreira A.L. Oxidative stress status of highly prolific sows during gestation and lactation. Animal. 2011;5:1774–1779. doi: 10.1017/S1751731111000772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besouw M., Masereeuw R., Van Den Heuvel L., Levtchenko E. Cysteamine: an old drug with new potential. Drug Discov Today. 2013;18:785–792. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black J.L., Mullan B.P., Lorschy M.L., Giles L.R. Lactation in the sow during heat stress. Livest Prod Sci. 1993;35:153–170. [Google Scholar]

- Blodgett D.J., Schurig G.G., Kornegay E.T., Meldrum J.B., Bonnette E.D. Failure of an enhanced dietary selenium concentration to stimulate humoral immunity in gestating swine. Nutr Rep Int. 1989;40:543–550. [Google Scholar]

- Bove P.F., Van Der Vliet A. Nitric oxide and reactive nitrogen species in airway epithelial signaling and inflammation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;41:515–527. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadenas E. Basic mechanisms of antioxidant activity. Biofactors. 1997;6:391–397. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520060404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaway J.C. Hempseed as a nutritional resource: an overview. Euphytica. 2004;140:65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Cao M., Li Y., Wu Q.J., Zhang P., Li W.T., Mao Z.Y., et al. Effects of dietary Clostridium butyricum addition to sows in late gestation and lactation on reproductive performance and intestinal microbiota1. J Anim Sci. 2019;97:3426–3439. doi: 10.1093/jas/skz186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan S.S., Celi P., Leury B.J., Clarke I.J., Dunshea F.R. Dietary antioxidants at supranutritional doses improve oxidative status and reduce the negative effects of heat stress in sheep. J Anim Sci. 2014;92:3364–3374. doi: 10.2527/jas.2014-7714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H.L., Cheng H.C., Liu Y.J., Liu S.Y., Wu W.T. Konjac acts as a natural laxative by increasing stool bulk and improving colonic ecology in healthy adults. Rev Nutr. 2006;22:1112–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Han J.H., Guan W.T., Chen F., Wang C.X., Zhang Y.Z., et al. Selenium and vitamin E in sow diets: I. Effect on antioxidant status and reproductive performance in multiparous sows. J Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2016;221:111–123. [Google Scholar]

- Coffey M.T., Britt J.H. Enhancement of sow reproductive performance by β-carotene or Vitamin A. J Anim Sci. 1993;71:1198–1202. doi: 10.2527/1993.7151198x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottrell J.J., Liu F., Hung A.T., Digiacomo K., Chauhan S.S., Leury B.J., et al. Nutritional strategies to alleviate heat stress in pigs. Anim Prod Sci. 2015;55:1391–1402. [Google Scholar]

- Cqta B., Jyl A., Ycj A., Yyy A., Xcz A., Mxc A., et al. Effects of dietary supplementation of different amounts of yeast extract on oxidative stress, milk components, and productive performance of sows. J Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2021;274:114648. [Google Scholar]

- David R.-C., Ester V., Francisco P.J., Tobias A., Lourdes C., Mihai P.L., et al. Phytogenic actives supplemented in hyperprolific sows: effects on maternal transfer of phytogenic compounds, colostrum and milk features, performance and antioxidant status of sows and their offspring, and piglet intestinal gene expression. J Anim Sci. 2020;98 doi: 10.1093/jas/skz390. skz390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decroos K., Vanhemmens S., Cattoir S., Boon N., Verstraete W. Isolation and characterisation of an equol-producing mixed microbial culture from a human faecal sample and its activity under gastrointestinal conditions. Arch Microbiol. 2005;183:45–55. doi: 10.1007/s00203-004-0747-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dima S., Fira S., Nissim S. Acute heat stress brings down milk secretion in dairy cows by up-regulating the activity of the milk-borne negative feedback regulatory system. BMC Physiol. 2009;9:13. doi: 10.1186/1472-6793-9-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duntas L.H., Benvenga S. Selenium: an element for life. Endocrine. 2014;48:756–775. doi: 10.1007/s12020-014-0477-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durmic Z., Blache D. Bioactive plants and plant products: effects on animal function, health and welfare. J Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2012;176:150–162. [Google Scholar]

- Ebert M.N., Klinder A., Peters W.H., Schaferhenrich A., Sendt W., Scheele J., et al. Expression of glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) in human colon cells and inducibility of GSTM2 by butyrate. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:1637–1644. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgg122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esther C. E V F. Iron and oxidative stress in pregnancy. J Nutr. 2003;133:1700S–1708S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.5.1700S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk M., Bernhoft A., Reinoso-Maset E., Salbu B., Lebed P., Framstad T., et al. Beneficial antioxidant status of piglets from sows fed selenomethionine compared with piglets from sows fed sodium selenite. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2020;58:126439. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2019.126439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Z., Xiao Y., Chen Y., Wu X., Zhang G., Wang Q., et al. Effects of catechins on litter size,reproductive performance and antioxidative status in gestating sows. Anim Nutr. 2015;1:271–275. doi: 10.1016/j.aninu.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng T., Bai J., Xu X., Guo Y., Huang Z., Liu Y. Supplementation with N-carbamylglutamate and vitamin C: improving gestation and lactation outcomes in sows under heat stress. Anim Prod Sci. 2017;58:1854–1859. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes J., Vogt J., Wolever T.M. Inulin increases short-term markers for colonic fermentation similarly in healthy and hyperinsulinaemic humans. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2011;65:1279–1286. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2011.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira J.F., Luthria D.L., Sasaki T., Heyerick A. Flavonoids from Artemisia annua L. as antioxidants and their potential synergism with artemisinin against malaria and cancer. Molecules. 2010;15:3135–3170. doi: 10.3390/molecules15053135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel T., Holbrook N.J. Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature. 2000;408:239–247. doi: 10.1038/35041687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grealish L., Lomasney A., Whiteman B. Foot massage. A nursing intervention to modify the distressing symptoms of pain and nausea in patients hospitalized with cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2000;23:237–243. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200006000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu X.L., Li H., Song Z.H., Ding Y.N., He X., Fan Z.Y. Effects of isomaltooligosaccharide and Bacillus supplementation on sow performance, serum metabolites, and serum and placental oxidative status. Anim Reprod Sci. 2019;207:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2019.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B. Free radicals and antioxidants: updating a personal view. Nutr Rev. 2012;70:257–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2012.00476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa T., Masuda T., Kurosawa D., Tsukahara T. Dietary administration of probiotics to sows and/or their neonates improves the reproductive performance, incidence of post-weaning diarrhea and histopathological parameters in the intestine of weaned piglets. Anim Sci J. 2016;87:1501–1510. doi: 10.1111/asj.12565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann P.R. Mechanisms by which selenium influences immune responses. Arch Immunol Ther Exp. 2007;55:289–297. doi: 10.1007/s00005-007-0036-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hongzhi W., Ji Y., Sibo W., Xin Z., Jinwang H., Fei X., et al. Effects of soybean isoflavone and Astragalus polysaccharide mixture on colostrum components, serum antioxidant, immune and hormone levels of lactating sows. Animals. 2021;11:132. doi: 10.3390/ani11010132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y.J., Gao K.G., Zheng C.T., Wu Z.J., Yang X.F., Wang L., et al. Effect of dietary supplementation with glycitein during late pregnancy and lactation on antioxidative indices and performance of primiparous sows. J Anim Sci. 2015;93:2246–2254. doi: 10.2527/jas.2014-7767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W., Guo H.L., Deng X., Zhu T.T., Xiong J.F., Xu Y.H., et al. Short-chain fatty acids inhibit oxidative stress and inflammation in mesangial cells induced by high glucose and lipopolysaccharide. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2017;125:98–105. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-121493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang P.F., Mou Q., Yang Y., Li J.M., Xu M.L., Huang J., et al. Effects of supplementing sow diets during late gestation with Pennisetum purpureum on antioxidant indices, immune parameters and faecal microbiota. Vet Med Sci. 2021;7:1347–1358. doi: 10.1002/vms3.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S., Wu Z., Hao X., Huang Z., Zhang L., Hu C., et al. Maternal supply of cysteamine during late gestation alleviates oxidative stress and enhances angiogenesis in porcine placenta. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2021;12:91. doi: 10.1186/s40104-021-00609-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal Z., Kamran Z., Sultan J.I., Ali A., Ahmad S., Shahzad M.I., et al. Replacement effect of vitamin E with grape polyphenols on antioxidant status, immune, and organs histopathological responses in broilers from 1-to 35-d age. J Appl Poultry Res. 2015;24:127–134. [Google Scholar]

- Jain P.K., Ravichandran V., Agrawal R.K. Antioxidant and free radical scavenging properties of traditionally used three Indian medicinal plants. Curr Trends Biotechnol Pharm. 2008;2:538–547. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferies H., Coster J., Khalil A., Bot J., Mccauley R.D., Hall J.C. Glutathione. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73:517–522. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-1433.2003.02682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X., Lin S., Lin Y., Fang Z., Xu S., Feng B., et al. Effects of silymarin supplementation during transition and lactation on reproductive performance, milk composition and haematological parameters in sows. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr. 2020;104:1896–1903. doi: 10.1111/jpn.13425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karowicz-Bilińska A., Suzin J., Sieroszewski P. Evaluation of oxidative stress indices during treatment in pregnant women with intrauterine growth retardation. Med Sci Mon Int Med J Exp Clin Res. 2002;8:CR211–CR216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp B.K., Bauer L.L., Swanson K.S., Tappenden K.A., Fahey G.C., Jr., De Godoy M.R. Soluble fiber dextrin and soluble corn fiber supplementation modify indices of health in cecum and colon of Sprague-Dawley rats. Nutrients. 2013;5:396–410. doi: 10.3390/nu5020396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb E., Seehawer J. Stress in pigs. II. The influence of vitamins. Tierärztliche Umsch. 2001;56:90–96. [Google Scholar]

- Koren O., Goodrich J.K., Cullender T.C., Spor A., Laitinen K., Bäckhed H.K., et al. Host remodeling of the gut microbiome and metabolic changes during pregnancy. Cell. 2012;150:470–480. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechowski J., Kasprzyk A., Tyra M., Trawińska B. Effect of ascorbic acid as a feed additive on indicators of the reproductive performance of Pulawska breed gilts. Med Weter. 2016;72:378–382. [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Liu Z., Lyu H., Gu X., Song Z., He X., et al. Effects of dietary inulin during late gestation on sow physiology, farrowing duration and piglet performance. Anim Reprod Sci. 2020;219:106531. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2020.106531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang H., Che L., Su G., Yue X., Wu D. The inclusion of yeast-derived protein in weanling diet improves growth performance, anti-oxidative capability and intestinal health of piglets. Czech J Anim Sci. 2014;59:327–336. [Google Scholar]

- Liao P., Li Y., Li M., Chen X., Xu K. Baicalin alleviates deoxynivalenol-induced intestinal inflammation and oxidative stress damage by inhibiting NF-κB and increasing mTOR signaling pathways in piglets. Food Chem Toxicol. 2020;140:111326. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2020.111326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W., Xiaodong X., Ge S., Baoming S., Anshan S. High concentration of vitamin E supplementation in sow diet during the last week of gestation and lactation affects the immunological variables and antioxidative parameters in piglets. J Dairy Res. 2017;84:8–13. doi: 10.1017/S0022029916000650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski K., Antoszkiewicz Z., Mazur-Kusnirek M., Korniewicz D., Kotlarczyk S. The effect of polyphenols on the performance and antioxidant status of sows and piglets. Ital J Anim Sci. 2019;18:174–181. [Google Scholar]

- Luo Z., Xu X., Sho T., Luo W., Zhang J., Xu W., et al. Effects of n-acetyl-cysteine supplementation in late gestational diet on maternal-placental redox status, placental NLRP3 inflammasome, and fecal microbiota in sows1. J Anim Sci. 2019;97:1757–1771. doi: 10.1093/jas/skz058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahan D.C., Kim Y.Y., Stuart R.L. Effect of vitamin E sources (RRR- or all-rac-alpha-tocopheryl acetate) and levels on sow reproductive performance, serum, tissue, and milk alpha-tocopherol contents over a five-parity period, and the effects on the progeny. J Anim Sci. 2000;78:110–119. doi: 10.2527/2000.781110x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavromatis J., Koptopoulos G., Kyriakis S.C., Papasteriadis A., Saoulidis K. Effects of alpha-tocopherol and selenium on pregnant sows and their piglets' immunity and performance. J Vet Med. 1999;46:545–553. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0442.1999.00244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Q., Sun S., Bai Y., Luo Z., Li Z., Shi B., et al. Effects of dietary resveratrol supplementation in sows on antioxidative status, myofiber characteristic and meat quality of offspring. Meat Sci. 2020;167:108176. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2020.108176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer A.M., Reed J.J., Neville T.L., Thorson J.F., Maddock-Carlin K.R., Taylor J.B., et al. Nutritional plane and selenium supply during gestation affect yield and nutrient composition of colostrum and milk in primiparous ewes. J Anim Sci. 2011;89:1627–1639. doi: 10.2527/jas.2010-3394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihai P.L., Mihaela H., Eliza M.D., Sanda C.V., Cecilia P.G., Alexandru G.I., et al. Effect of dietary hemp seed on oxidative status in sows during late gestation and lactation and their offspring. Animals. 2019;9:194. doi: 10.3390/ani9040194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon Y.J., Wang X., Morris M.E. Dietary flavonoids: effects on xenobiotic and carcinogen metabolism. Toxicol Vitro. 2006;20:187–210. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2005.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mou D., Wang J., Liu H., Chen Y., Che L., Fang Z., et al. Maternal methyl donor supplementation during gestation counteracts bisphenol A-induced oxidative stress in sows and offspring. Nutrition. 2018;45:76–84. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2017.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council . Nutrient requirements of swine (11th revised edition) National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Osman M.H., Shayoub E.M., Babiker M.E. The effect of Moringa oleifera leaves on blood parameters and body weights of albino rats and rabbits. Jordan J Biol Sci. 2012;5:147–150. [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki T., Kaibori M., Matsui K., Tokuhara K., Tanaka H., Kamiyama Y., et al. Effect of thiol-containing molecule cysteamine on the induction of inducible nitric oxide synthase in hepatocytes. JPEN - J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2007;31:366–371. doi: 10.1177/0148607107031005366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palade L.M., Habeanu M., Marin D.E., Chedea V.S., Pistol G.C., Grosu I.A., et al. Effect of dietary hemp seed on oxidative status in sows during late gestation and lactation and their offspring. Animals. 2019;9(4):194. doi: 10.3390/ani9040194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto A., Juniper D.T., Sanil M., Morgan L., Clark L., Sies H., et al. Supranutritional selenium induces alterations in molecular targets related to energy metabolism in skeletal muscle and visceral adipose tissue of pigs. J Inorg Biochem. 2012;114:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzino G., Irrera N., Cucinotta M., Pallio G., Mannino F., Arcoraci V., et al. Oxidative stress: harms and benefits for human health. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:8416763. doi: 10.1155/2017/8416763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Camacho D., Vinyeta E., Perez J.F., Aumiller T., Criado L., Palade L.M., et al. Phytogenic actives supplemented in hyperprolific sows: effects on maternal transfer of phytogenic compounds, colostrum and milk features, performance and antioxidant status of sows and their offspring, and piglet intestinal gene expression. J Anim Sci. 2020;98 doi: 10.1093/jas/skz390. skz390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricciardolo F.L., Sterk P.J., Gaston B., Folkerts G. Nitric oxide in health and disease of the respiratory system. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:731–765. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00034.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosignoli P., Fabiani R., De Bartolomeo A., Spinozzi F., Agea E., Pelli M.A., et al. Protective activity of butyrate on hydrogen peroxide-induced DNA damage in isolated human colonocytes and HT29 tumour cells. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:1675–1680. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.10.1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ru J.A., Fas B., Wl C., Lc A., Zs A. Protective effects of Bacillus subtilis ASAG 216 on growth performance, antioxidant capacity, gut microbiota and tissues residues of weaned piglets fed deoxynivalenol contaminated diets. Food Chem Toxicol. 2021;148:111962. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2020.111962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz K., Foltzs C.M. Selenium as an integral part of factor 3 against dietary necrotic liver degeneration. Nutr Rev. 2009;36:338–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah H., Sami J., Olli P., Lars P., Annina L., Juhani V., et al. Dietary supplementation with yeast hydrolysate in pregnancy influences colostrum yield and gut microbiota of sows and piglets after birth. PLoS One. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y.B., Piao X.S., Kim S.W., Wang L., Liu P., Yoon I., et al. Effects of yeast culture supplementation on growth performance, intestinal health, and immune response of nursery pigs. J Anim Sci. 2009;87:2614–2624. doi: 10.2527/jas.2008-1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivropoulou A., Papanikolaou E., Nikolaou C., Kokkini S., Lanaras T., Arsenakis M. Antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities of Origanum Essential oils. J Agric Food Chem. 1996;44:1202–1205. [Google Scholar]

- Sosnowska A., Kawecka M., Jacyno E., Kolodziej-Skalska A., Kamyczek M., Matysiak B. Effect of dietary vitamins E and C supplementation on performance of sows and piglets. Acta Agr Scand A-An. 2011;61:196–203. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart W.C., Bobe G., Vorachek W.R., Stang B.V., Pirelli G.J., Mosher W.D., et al. Organic and inorganic selenium: IV. passive transfer of immunoglobulin from Ewe to lamb. J Anim Sci. 2013;91:1791–1800. doi: 10.2527/jas.2012-5377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J.-J., Wang P., Chen G.-P., Luo J.-Y., Xi Q.-Y., Cai G.-Y., et al. Effect of Moringa oleifera supplementation on productive performance, colostrum composition and serum biochemical indexes of sow. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr. 2020;104:291–299. doi: 10.1111/jpn.13224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surai P.F. Nottingham University Press; Nottingham: 2006. Selenium in nutrition and health. [Google Scholar]

- Surai P. Silymarin as a natural antioxidant: an overview of the current evidence and perspectives. Antioxidants. 2015;4:204–247. doi: 10.3390/antiox4010204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney T., Collins C.B., Reilly P., Pierce K.M., Ryan M., O'doherty J.V. Effect of purified beta-glucans derived from Laminaria digitata, Laminaria hyperborea and Saccharomyces cerevisiae on piglet performance, selected bacterial populations, volatile fatty acids and pro-inflammatory cytokines in the gastrointestinal tract of pigs. Br J Nutr. 2012;108:1226–1234. doi: 10.1017/S0007114511006751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takei H., Iizuka S., Yamamoto M., Takeda S., Yamamoto M., Arishima K. The herbal medicine Tokishakuyakusan increases fetal blood glucose concentrations and growth hormone levels and improves intrauterine growth retardation induced by N(omega)-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester. J Pharmacol Sci. 2007;104:319–328. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fp0070224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan C., Wei H., Sun H., Ao J., Long G., Jiang S., et al. Effects of dietary supplementation of oregano essential oil to sows on oxidative stress status, lactation feed intake of sows, and piglet performance. BioMed Res Int. 2015;2015:525218. doi: 10.1155/2015/525218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan C.Q., Wei H.K., Sun H.Q., Long G., Ao J.T., Jiang S.W., et al. Effects of supplementing sow diets during two gestations with konjac flour and Saccharomyces boulardii on constipation in peripartal period, lactation feed intake and piglet performance. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2015;210:254–262. [Google Scholar]

- Tan C., Wei H., Ao J., Long G., Peng J. Inclusion of konjac flour in the gestation diet changes the gut microbiota, alleviates oxidative stress, and improves insulin sensitivity in sows. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2016;82:5899–5909. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01374-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan C.Q., Li J.Y., Ji Y.C., Yang Y.Y., Zhao X.C., Chen M.X., et al. Effects of dietary supplementation of different amounts of yeast extract on oxidative stress, milk components, and productive performance of sows. J Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2021;274:114648. [Google Scholar]