Abstract

Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) has emerged as a significant public health issue, in Canada and elsewhere. Health experts increasingly acknowledge that the disproportionate impact of FASD on indigenous people is driven by social and historical contexts, especially in settler colonial states like Canada. However, they generally frame FASD as preventable through abstinence and the effects of FASD as manageable through provision of appropriate medical and legal protection to affected offspring. Drawing from Marxist, anticolonial and anti-imperial theories and applying a Critical Discourse Analysis approach, we identify the (re) production of colonial and capitalist dominance in the expert literature. We show that dominant narratives depoliticize FASD by conceptualizing settler colonialism as a past event, ignoring ongoing, contemporary forms of settler colonial dispossession and resituating FASD within an expert language that locates solutions to FASD within affected individuals and communities. In so doing, these narratives legitimize, and contribute to perpetuating, existing disease inequities, prevent the formulation of policies that address the very real and as yet unmet needs of FASD affected individuals, families and communities and erase from the public discourse discussions about changes that could truly address FASD inequities at their root. We conclude by elaborating on the implication of these narratives for policy, practice and equity, in Canada and other settler colonial states.

Keywords: discourse analysis, health policy, race, ethnicity and health, social inequalities in health, theory

Introduction

Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD), an umbrella term describing a range of signs and symptoms in an individual whose mother drank during pregnancy (CAMH, n.d.), has emerged as a significant public health issue, in Canada and elsewhere (Badry and Felske, 2013). Central to FASD is why it affects indigenous communities disproportionately and to what extent this disproportionate impact is driven by the intergenerational effects of residential schooling, cultural disenfranchisement and child apprehension (Badry and Felske, 2013; Tait, 2003a). Disagreements around rates and distribution aside, indigenous leaders in Canada have expressed concern about the impact of FASD on their communities (Salmon, 2011; Tait, 2003a). Health professionals share the concern and increasingly acknowledge that socio-historical contexts matter, especially in settler-colonial states like Canada (PHAC, 2006e). Nevertheless, experts generally frame FASD as preventable by supporting mothers-to-be to recover from alcohol addiction or refrain from drinking while pregnant (CAMH, n.d.).

The social determinants of health literature and indigenous scholarship warn that public health approaches to FASD prevention that emphasize abstention downplay socio-political contexts and blame the victim, as they encourage mothers-to-be to take responsibility for theirs and their offspring’s health under circumstances over which they have little control (Godderis and Stephenson, 2017). These research traditions note that devolution of responsibility, alongside hegemonic conceptions of good mothering, present indigenous communities as the source of their own problems and indigenous mothers as the site of intervention on these problems (Salmon, 2011). While mainstream public health has heeded on this warning, acknowledging socio-historical drivers, evidence indicates that actual policies and practices still focus overwhelmingly on individual behavioural change, at best neglecting, at worst ignoring, past and, critically, continuing processes of settler-colonial-capitalist dispossession.

Building on the work of decolonizing scholarship (Barker, 2012; Veracini, 2011; Wolfe, 2006), we apply a Critical Discourse Analysis approach (Fairclough, 1993) to appraise how expert narratives on FASD in Canada frame and address FASD and whether and how they challenge or reproduce settler colonial dominance and in so doing influence the health and well-being of indigenous women and communities. Our inquiry is informed by theories of settler colonialism (Alfred, 2005; Coulthard, 2014; Veracini, 2010) and Marxist theories of health (Navarro, 2009; Waitzkin and Jasso-Aguilar, 2015) that seek to identify narratives that serve privileged minorities and challenge them by carving out spaces of resistance in discourse and practice (Chaufan, 2006; Fairclough, 2013).

Background

Foetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) refers to conditions – Foetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS), Partial FAS (pFAS) and Alcohol Related Neurodevelopmental Disorders (ARND) – that result from alcohol exposure during foetal development (Chudley et al., 2005) and vary in severity with levels of alcohol exposure (Health Canada, 2006). The effects of FASD ‘may include physical, mental, behavioural, and/or learning disabilities’ (CAMH, n.d.). If left untreated, secondary disabilities may eventually develop, resulting in significant social and economic costs to individuals, families and society (Health Canada, 2006).

Abundant evidence links Canada’s colonial history and its legacy – social and cultural disruption, structural violence and geographical dislocation – to substance use in indigenous communities (MacDonald and Steenbeek, 2015; Tait, 2003a). Gendered experiences of violence and trauma, including sexual assault and femicide, disproportionally affecting indigenous women, have also been identified as determinants of FASD (NWAC, 2010) and substance abuse (Shahram et al., 2017). Collectively, these experiences, rooted in (neo) colonial policies, practices and ideologies (Barker et al., 2016; Coulthard, 2014), hint at the role of alcohol in the development of the settler-capitalist character of the Canadian state, to which we now turn.

A state is born: Alcohol and Canadian settler-capitalism

Alcohol marked a critical juncture among settlers and indigenous peoples at the birth of Canada’s colonial-capitalist project. Historians note that most indigenous societies living within current Canadian territory lacked brewing traditions prior to colonial contact, that most were introduced to alcohol by settlers, and that the introduction of alcohol was key to settler’s takeover of indigenous modes of production (Steckley and Cummins, 2001). The fur trade introduced both alcohol (Tait, 2003a) and mercantile economies to indigenous societies (Warburton and Scott, 1985). To lure indigenous fur trappers and secure trade, settlers prepared potent distillations of alcohol, presenting it as a ‘highly sought-after trade item’ (Tait, 2003b: 193). The abundance of alcohol exacerbated violence against indigenous women (Tait, 2003b), whose status was already downgraded by a fur trade depending on wage-labour favouring men and enabling men preferential access to European goods. These practices jointly led to women’s marginalization (Devens, 1992), with repercussions on their wellbeing to this day.

Alcohol was also used to justify a racialized form of social control that promoted Canada’s development as a settler-capitalist state. As part of advancing colonial dominance, medical experts hypothesized race-based predispositions to addiction and slower rates of alcohol metabolism (Tait, 2003a). Settler colonial laws further legitimized the biopolitical control of indigenous peoples, not only punishing intoxication (Tait, 2003b) but also making alcohol possession by indigenous persons contingent on Canadian citizenship, while simultaneously establishing that indigenous persons had to demonstrate sobriety to be eligible for Canadian citizenship, a practice established by the Indian Act in 1976 and lasting through 1985 (Campbell, 2008). Therefore, ‘liquor laws governed racial status as much as, and perhaps more effectively than, they governed drinking’ (Valverde, 1998: 164). In an interesting contemporary twist, today provincial liquor stores are often the closest, and even the only, place to cash income assistance payments for some indigenous people on reserves (J Rodriguez, 2019, personal communication). While it could be argued that having liquor stores as the only place to cash checks encourages rather than forbids alcohol consumption, unlike the Indian Act did, we note that both manipulate alcohol to control indigenous communities.

The point we wish to make is that these processes jointly illustrate how the economic, legal, social and political management of alcohol is deeply intertwined with the development and consolidation of Canada as both a settler and a capitalist state. Importantly for our purpose, state-sponsored policies and practices require a self-renovating ideology to legitimize indigenous dispossession, thus the need to identify this ideology and assess how it has developed, from Canada’s birth as an independent nation state, up to its current status as junior partner of the US-led global capitalist empire (Gindin and Panitch, 2012).

Canadian state and settler colonialism: Elimination, assimilation, recognition

Early settlement patterns in Canada were marked by land expropriation, disruption of indigenous economies, proletarianization and chattel slavery. A policy of elimination informed the years of the fur trade, replacing traditional production based on exchange of use values with commodity exchange marked by war, disease and territorial dispossession (Daschuk, 2013). Modes of capital appropriation included settlers advancing credit to indigenous fur trappers and indebting them through the sale of European goods (Warburton and Scott, 1985). Once Canada became a settler state, settlers accumulated wealth by coercing indigenous peoples into chattel slavery (Neeganagwedgin, 2012), controlling their food supplies and forcing them into treaties or subjecting them to mass hangings in order to expropriate their lands (Daschuk, 2013).

An ostensibly less aggressive, albeit similarly destructive, policy of elimination through assimilation of indigenous peoples into the settler model prevailed through the late 19th century, marked by ‘paternalism, segregation and violence’ (Barker et al., 2016: 153). The Indian Act became the primary political instrument of the Canadian state to define and enforce ‘reserve lands’ and supplant indigenous governance with band councils (Barker et al., 2016). The state held the monopoly of violence through the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, which encroached into traditional territories, and through the ‘Indian Agent’, which controlled the everyday lives of indigenous people (Barker et al., 2016). However, the most notable example of elimination through assimilation is the well-documented Indian Residential School system, that sought to ‘civilize’ indigenous people by severing intergenerational bonds and erasing indigenous culture (Chrisjohn et al., 2003). This era also marked the beginning of a genocidal public health practice, the forcible sterilization of indigenous women – even girls, such that ‘any child who was “socially or morally defective”’ was sterilized at puberty (Pegoraro, 2015), a practice occurring as recently as 2018 (Zingel, 2019). The long-standing effects of genocidal laws, policies and practices have resulted in staggeringly poor and seemingly refractory to intervention social and health outcomes that continue to this day (MacDonald and Steenbeek, 2015).

The late 20th century marked a change in the balancer of power between settlers and indigenous peoples: relations were no longer maintained through coercion or assimilation but through ‘the asymmetrical exchange of mediated forms of state recognition’ of indigenous rights (Coulthard, 2014: 15). Put another way, even as the practice of state-supported appropriation of indigenous land has since continued, the discourse of indigenous-settler relations has become ‘couched in the vernacular of “mutual recognition”’ (Coulthard, 2014: 3), stifling indigenous resistance against colonial formations (Barker et al., 2016; Coulthard, 2014). Recognition, hailed as the solution to historical abuses, has promoted reconciliation through forgiveness for past abuses, yet has left the ‘structure of colonial rule [and capital accumulation] largely unscathed’ (Coulthard, 2014: 22). An example is Bill C-69 mandating that when extracting non-renewable resources indigenous communities must be consulted and compensated. However, compensation depends on these communities forfeiting traditional territories, so their consent allows them to manage their poverty at best, at worst locks them into debt traps that coerce them to open their land to resource exploitation. Not only does compensation erase the struggle for land, it has also served to transform traditional relations between indigenous communities and their land into relations of capitalist private property (Coulthard, 2014). While indigenous communities have often resisted the settler colonial project, historically and in current times, the project has largely been successful in squashing this resistance – either ignoring it, misrepresenting it, co-opting it or, when necessary, violently suppressing it (Coulthard, 2014).

We suggest that the continuing renovation of settler colonial ideology, as it emerged from the ashes of the Golden Age of capitalism and from the 1960s decolonizing struggles in the Global South, has contributed to the neoliberal reconstruction of the Canadian state launched in the 1970s. This ideology is now becoming institutionalized through state-sponsored corporate projects that co-opt or suppress indigenous resistance. These projects span the history of Canadian settler colonialism, from the building of a railroad system that connected settlers, indigenous labour and resources to the opening of indigenous territories to fracking and pipeline development in the current era (Barker et al., 2016), allowing ‘corporate profits to evade indigenous resistance’ (p. 158), occupy indigenous land and impact health outcomes.

Finally, indigenous dispossession has also been firmly accomplished through overt state-violence – through the military, targeting indigenous leaders, discipling the population and often expelling them from their land (Alfred, 2005). Examples abound: during the 1990 Oka Crisis land dispute, Canadian forces removed protesting Mohawks from their land to build a private golf course. More recently, RCMP officers removed the Wet’suwet’en from theirs to prepare for the liquified natural gas pipeline (Morin, 2020). State-violence is part of the ‘slow industrial genocide’ of indigenous nations in Canada (Barker et al., 2016: 161) and has led to predictably poor social and health outcomes – such as high rates of FASD – refractory to intervention despite significant influxes of public monies (Huseman and Short, 2012).

Theoretical and methodological considerations

Following a Marxian tradition in health studies (Navarro, 2009; Waitzkin and Jasso-Aguilar, 2015), we assume that health is political, that in hierarchical societies dominant narratives, that is, accounts of the social world disseminated by key institutions and thought leaders, tend to conceal the political nature of health, and that the task of critical health scholarship is to challenge these narratives in order to identify and help to transcend structures of domination in support of better health, social justice and human emancipation (Chaufan, 2006). We also assume that dominant narratives dominate because they are persuasive, and that they persuade because they are simple, that is, they present social problems as ultimately amenable to technical fixes; ostensibly benign, that is, they appear committed to the public good whatever they do in practice; and authoritative, that is, they are upheld by authorities with the power to selectively include or exclude what voices should be heard (Chaufan and Saliba, 2019). In sum, dominant narratives promote a ‘common sense’ that manufactures consent (Gramsci, 2011) by discouraging, or legitimizing the repression of, challenges to the status quo (Herman and Chomsky, 1988).

In accordance with this tradition we also assume that dominant narratives are most serviceable to so-called liberal democracies, forms of political governance that normatively condemn the use of naked power to repress dissent and allow ample room for diverse viewpoints, yet in practice dramatically limit the space for questioning capitalist social relations (Chaufan and Saliba, 2019). Narratives are amenable to critical appraisal through Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA), a method of inquiry that allows critical scholars to identify how discourse is used to legitimize or challenge relations of domination (Fairclough, 2013).

Our data consisted of publicly available documents that we treated as ‘social facts’, that is, organized to reflect actual power relations and convey meanings (Bowen, 2009). Our goal was to identify documents representing dominant narratives on alcohol consumption in Canadian society, that focus on, and inform, conceptualizations, policies and practices concerning FASD. To inform our study of government discussions and legislation on FASD we searched for Parliamentary debates on FASD in Our Commons. Additionally, we searched the websites of Health Canada, the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) and government sponsored organizations, such as the Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder Ontario Network of Expertise. To ensure that we would consider a wide range of perspectives we also examined publications from indigenous health organizations that collaborate with the Canadian government to inform public health campaigns. These included the National Aboriginal Health Organization Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health, National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health, the Ontario Federation of Indigenous Friendship Centres and the Native Women’s Association of Canada. To map the gaze of health professionals we searched the websites of leading journals (e.g. Canadian Journal of Public Health and Canadian Medical Association Journal). Finally, to map the legal perspective we retrieved court cases from the Canadian Legal Information Institute. Because we focussed on current narratives on FASD, we only included documents from 2000 to 2018 retrieved through the following search terms, alone or in combination: ‘alcohol’, ‘substance use’, ‘drink’, ‘pregnancy’, ‘prenatal’, ‘fetus’, ‘mother’, ‘fetal alcohol spectrum disorder’ and ‘fetal alcohol syndrome’ (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Data selection strategy.

We selected documents that included information on at least one of the following: (a) diagnostic criteria and prevalence of FASD; (b) causes, prevention and treatment of FASD; (c) health, social and economic consequences for mothers, FASD affected individuals and society; (d) recommendations for mothers-to-be; and (e) legal treatment of the foetal-mother relationship, parental fitness of defendants of court cases, extent of judicial scrutiny on women who give birth to children with FASD, and context of court cases concerning child apprehension. The search generated over 200 documents – government publications, public health campaigns, refereed articles and legal proceedings or court cases – that we narrowed down to 68 documents on alcohol consumption during pregnancy (Tables 1).

Table 1.

Documents assessed per community of discourse.

| Community of discourse | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Public policy | 38 | 56 |

| Academic health care | 20 | 29 |

| Legal | 10 | 15 |

| Total | 68 | 100 |

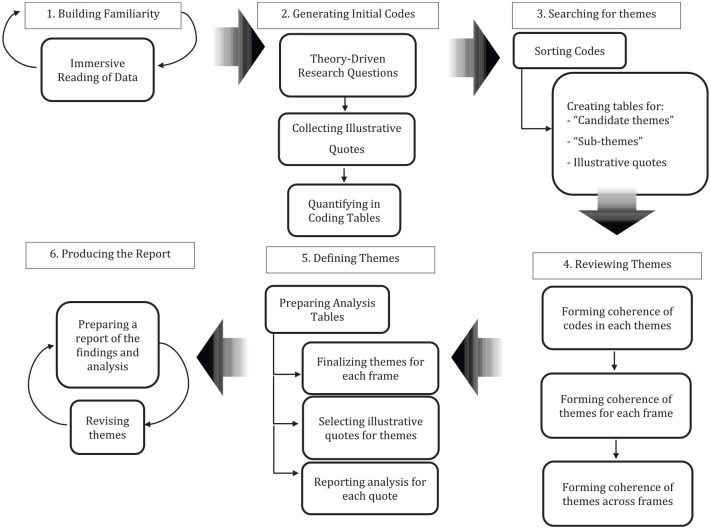

We organized documents in sets representing ‘communities of discourse’, the discursive manifestation of a community defined by its expertise on a specific matter (Chaufan, 2006), and conceptualized three such communities as centres of expertise informing official knowledge and practice concerning FASD: (1) the Canadian state/policymakers; (2) health professions and institutions; and (3) legal professions and institutions. We then performed a thematic analysis which included immersion in the data to gain familiarity, close reading of documents to determine messages on FASD and indigeneity using guiding questions (e.g. ‘what causes FASD?’, ‘what are the best ways to address FASD/differences in rates of FASD in populations?’; ‘who is responsible for what in preventing or treating FASD?’); constructing codes and identifying themes to map trends, selecting quotations to illustrate the identified themes; and finally, interpreting how messages reproduced or challenged extant power relations (Braun and Clarke, 2006). We met periodically to refine research goals, discuss findings and interpretation, revise drafts and resolve disagreements by consensus (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Data analysis strategy.

As with all qualitative research, we are aware that we have played a significant role in the overall research process – from framing our research questions, to choosing theoretical lenses and methodological approaches, to selecting and interpreting the data we identify (Baxter and Jack, 2008). With that being said, we have reproduced the steps of our inquiry to the best of our ability so that other investigators can assess our findings and interpretations. The use of publicly available documents did not require Ethics Review Board approval.

Findings and analysis

The salient feature of dominant messages was how they individualized FASD. Despite acknowledgment of its complexity, FASD appeared ultimately simple – caused by drinking during pregnancy, among other unhealthy behaviours. Recommended interventions followed reasonably: mothers-to-be shouldn’t drink. Persuasively, dominant messages were benign, often warning against shaming victims and pointing to their environments – social forces beyond the control of any single policy, institution or individual. Moreover, interventions were always proposed for the benefit of the disadvantaged, and many such interventions indeed were – who would argue against more and better psychological support, medical treatment and educational opportunities? Oftentimes sources acknowledged quite explicitly that the overrepresentation of poor and indigenous women and children whose mothers drank during pregnancy results from histories of colonialism, dispossession and ongoing disempowerment. Finally, dominant messages – authoritative by definition as they were conveyed by experts in major social institutions – often deployed their authority beyond their narrow scope of expertise by engaging in subtle moralizing and selectively choosing who deserved to be heard on the matter of FASD.

Notably, while selected features of these narratives, such as acknowledging complexity, colonialism and so on, made them appear ‘political’, the thrust of the message individualized FASD, therefore depoliticizing it. Mechanisms included relegating ‘colonialism’ to the past, downplaying or omitting neocolonial dispossession, or discursively transforming systemic abuses into features of affected individuals or their loved ones (e.g. ‘lack of awareness’), who were subsequently offered behavioural and psychological advice and encouraged to become ‘empowered’ even when their chances to succeed were slim. By depoliticizing FASD and calling instead for its liberal acknowledgement (more on this point later), dominant messages legitimized existing disease inequities, limited the interventions that could address the many unmet needs of FASD affected populations – of proper housing, healthy nutrition, drinkable water, quality healthcare – discouraged anti-imperial approaches able to tackle FASD inequities at their root, and contributed to reproducing FASD inequities. In the following section we organize these messages according to their simple, benign and authoritative nature and illustrate them with quotations as we interpret their ideological work on the body politic.

The causes of, and solutions to, FASD and FASD inequities are simple

A majority of the articles across all communities of discourse located the root causes of FASD in the mother – her physiology, behaviours or psychology. As described by the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC):

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) is a term that describes a range of disabilities that may affect people whose birth mothers drank alcohol while they were pregnant [. . .] The only way someone can get FASD is if their birth mother drank alcohol when she was pregnant [. . .]. Alcohol causes brain damage in the developing baby (PHAC, 2005a: 2–3)

The take-away is simple: the behaviour of the mother-to-be is, if not the only, the most critical source of FASD-related ‘damage’ to the health of her child. The proposed intervention followed reasonably: ‘If you are pregnant, or planning to become pregnant in the near future, do not drink alcohol’ (Health Canada, 2006: 2).

While this matter-of-fact language to define FASD makes the article appear objective, authors never mentioned longstanding critiques linking drinking to sociopolitical determinants of FASD (Golden, 1999; Hunting and Browne, 2012). Thus routinely, public health initiatives advised women to seek professional assistance to support behavioural changes and prompted loved ones to gently prod mothers-to-be to not drink. The process was compellingly captured in a poster on the FASD Ontario Network of Expertise website portraying an image of racially diverse pregnant women: the painted message on their exposed pregnant abdomens, reinforced by enthusiastic verbal messages about the importance of abstinence during pregnancy, urged all women to ‘Think B4 U Drink’ (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

‘Think Before You Drink’.

Source: https://fasdontario.ca.

Another salient feature was the simplification of the political context engendering alcohol consumption. For example, two public health articles discussed briefly the socio-historical drivers of the disproportionate substance use among indigenous women yet presented them as triggers to the real causes – lifestyles and genetics. Thus, the very reports that acknowledged the structural causes of FASD – including the very few that explicitly alluded to colonialism – conveyed the message that these factors only exacerbated the problem, proposing abstention as the common-sense solution to FASD and its inequitable impact. Indeed, not a single article acknowledged the ongoing, neocolonial dynamics as cause of FASD. Even the most sympathetic authors relegated colonialism to Canada’s history. An example by Health Canada follows:

Having been stripped of political agency on the nation level because of colonial attitudes of dominance and paternalism, First Nations and Inuit, families, and communities find themselves with decreased levels of self-sufficiency [. . .] Furthermore, an intergenerational cycle of physical, psychological, sexual abuse, and loss of spiritual practices has sprung from this history of devaluation and control [. . .], providing fertile soil for addictions, alcoholism, and substance abuse (FAS/FAE Technical Working Group, 2001: 4).

At first glance, the quotation links FASD to settler colonialism. However, it subsequently depoliticizes it: firstly, while describing the process of colonialism the authors do not tell readers who has ‘stripped’ indigenous communities of political agency, nor who holds ‘attitudes of dominance and paternalism’. Put another way, they do not name the colonizer. Next, the authors place ‘First Nations and Inuit, families, and communities’ as the subject of the sentence, performing the action of finding themselves ‘with decreased levels of self-sufficiency’, as if they were the perpetrators, rather than the victims, of an unnamed, therefore invisible, colonial process. In this and similar examples, the erasure of the colonial agent through grammatical acrobatics absolved the state from responsibility for not only past but also the ongoing structural violence that leads to poor social and health outcomes among indigenous communities.

Finally, no document acknowledged ongoing settler-colonial dispossession as driving substance use. Rather, they framed current coping behaviours among indigenous persons as the lingering effect of colonial histories characterized almost entirely by one single institution: residential schools, a process dubbed as ‘hiding behind the ethnic cleanser’, whereby the settler state condemns the past genocide while concealing its role in promoting ‘the conditions of its production’ (Veracini, 2010: 14). Similarly, current social, economic, and political marginalization were presented not as ongoing but as effects of ‘intergenerational’ trauma passed down through defective parenting or cultures, as if settler-colonial violence were perpetrated by indigenous peoples upon themselves.

Dominant approaches to FASD are ostensibly benign

As mentioned earlier, across communities of discourse the manifest goal of dominant messages was to promote the best interest of women by, for instance, encouraging them to seek treatment to cope with the trauma leading to substance use, and calling for more and better funded alcohol treatment services. For instance, Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) recommended that the government, policymakers and the public health community:

Make funding available to incorporate childcare and children’s programming into women’s substance abuse treatment services. Promote policies that require priority admission for pregnant women to substance abuse treatment. [. . .] Promote the development of respectful, flexible, comprehensive and harm reduction-oriented programming for pregnant women with substance use issues. [. . .] Promote outreach and intensive case coordination for moderate- and high-risk pregnant women and mothers. (PHAC, 2006e: 70)

In principle, addiction treatment and educational awareness campaigns are good public health policy. However, the details of these policies invariably implied that women themselves – their behaviours, attitudes and mental health states – are the appropriate targets of interventions. As health researchers, we note that better services for individuals of all backgrounds experiencing substance use are long overdue (Young and Manion, 2017). However, as critical health researchers, we note that when dominant messages fail to even name the state-sponsored and societal sources of trauma, these messages become hard to endorse. In sum, dominant messages advocated for better ways to manage traumas while giving short shrift to their structural roots.

Occasionally, dominant messages grounded the locus of change outside of mothers, calling instead for changes in the service professionals. For instance, the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) noted that health and other social institutions should:

Increase Public and Professional Awareness and Understanding of FASD [. . .] to help prevent FASD in a non-judgmental and ethno-culturally sensitive manner. [. . .] Ensuring that up-to-date information is readily accessible—information that is gender appropriate and ethno-culturally sensitive, and that encompasses the complex factors that contribute to alcohol use during pregnancy—is vital to effective prevention. Equally important is improving the understanding among the myriad professionals in health, education, justice, law enforcement, corrections, child welfare and social services of how this multi-faceted disability affects individuals and families. (PHAC, 2005b: 11)

Clearly, who would argue against cultural sensitivity training for service professionals, which at least could empower them to challenge dominant discourses? However, many such professionals – especially front-line workers – are themselves oppressed (Jefferies et al., 2018) – openly racialized and overwhelmingly female – and can do little individually. Moreover, the authors not only sanitize the ongoing process of settler-colonial violence by promoting instead the safer, more politically acceptable and expedient approach of professional training, they also frame the violence as resulting from professionals’ ‘poor judgement’ and ‘ethno-cultural insensitivity’, itself likely the predictable outcome of settler-colonial ideology.

The legal community of discourse offered a compelling case of the persuasiveness of dominant narratives and their power to reproduce social hierarchies. As they discussed the well-being of children considered for removal from homes where parents used alcohol, documents underscored that all else equal children are better off with their parents and in their cultures, and reassured audiences that parents could regain custody if they complied with court-mandated treatment (e.g. parenting workshops). Simultaneously, most court cases reinforced settler-colonial power, for instance, when defining the most beneficial interventions for parents and children:

The mother must understand that this was not an easy case [. . .] and with the history of abuse and neglect, the social workers were not wrong in treating the protection issue seriously. This court has made a finding of need of protection. However, this metamorphosis in the life of the mother has led to her having more [. . .] parental capacity and [. . .] to my decision to allow S.C. to return home. If the mother falls off the wagon, she must understand that the likely outcome is that the child will be removed, and a future continuing custody order would not be unlikely. I encourage the mother to continue using her current supports and learning more about the special needs of S.C. so that she will be better able to address those needs. (Director of Family and Child Services v. M.B., 2003)

This quotation illustrates well a seemingly benevolent narrative: in considering whether the child should be raised by the mother or apprehended into foster care, the law sympathized with parents’ fear of losing their children, while concealing state power through the use of third person and torturous grammar – ‘this court has made a finding for need of protection’ rather than ‘we have decided to protect the child our way’ – and passive voice – the child ‘will be removed’. Readers are told that the law means well, despite the message that unless the mother learns ‘more about the special needs of S.C’. to be ‘better able to address those needs’ [according to the court], the state will take the child away – end of discussion.

Finally, messages across all communities of discourse repeatedly emphasized the importance of building trust with indigenous communities by including indigenous voices in decision-making processes. For instance, several public-health initiatives and state-funded indigenous organizations called for consultation with indigenous communities when designing research and treatment programmes, recommending that these programmes be informed by indigenous philosophies. As the Ontario Federation of Indigenous Friendship Centres (OFIFC), who partners with Canadian governments, corporations and non-profits, states:

Developing trust in Native communities means allowing the person to come to the teaching rather than imposing the teaching on the person [. . .] The recovery of our cultures has in fact been shown to have great positive effects for individuals, families and communities coping with FASD. These cultural ways may well be our best resources. (OFIFC, 2008: 11)

Surely, including indigenous traditions in designing interventions is an improvement over assimilationist approaches. We note however three problems: first, indigenous traditions can afford a façade of legitimacy to capitalist exploitation, such as when pharmaceutical companies use patents to transform centuries of indigenous knowledge into private property (Mgbeoji, 2006); second, the quotation gives the illusion that institutions can make capitalism more ‘inclusive’ by adding a few indigenous faces; and finally, it orients policy towards a discourse of reconciliation that centres the indigenous population as the object of study, while diverting attention away from the ongoing violence of land dispossession and resource appropriation. We, like other scholars, take issue with ‘inclusive’ approaches that co-opt resistance and suppress anti-imperial struggles (Coulthard, 2014; Navarro, 2009; Waitzkin, 2017).

Dominant approaches to FASD are authoritative

Finally, as mentioned earlier, all communities of discourse were authoritative by definition in that they conveyed the perspective of socially recognized authorities, confidently communicated, albeit with scant empirical evidence, that behavioural change on a mass scale can achieve prenatal sobriety:

On November 18, 2008, the Canadian Executive Council on Addictions, the Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health and BC Mental Health & Addiction Services announced the development of a new strategic initiative focused on a national treatment strategy for those with substance use problems [emphasis added]. In the interest of prevention of FASD, a consistent approach to the problematic use of alcohol within society is critical. (PHAC, 2010b: 9)

While the authoritative nature of these narratives is to be expected, this and similar messages hardly ever drew from critical scholarship calling attention to the socio-historical factors impinging upon mothers who drink (Golden, 1999) made no mention of research that challenges behavioural change as a health promotion strategy (Chaufan et al., 2012), or drew attention to how all too often it is the social system – not the affected population – that requires change to tackle the multiple unmet needs of FASD affected individuals, families and communities. Instead, the focus of research and interventions was invariably about changing substance users (or their communities), thus dominant messages individualized, and legitimized individual responsibility for, the problem. The document thus continued:

Due to the diversity of programs across Canada, this group recommends a “Tiered Model of Services and Supports” that recognizes “acuity, chronicity and complexity of substance use risks and harms, and their corresponding intensity.” This report is raising a critical discourse on the need to address issues of consistency relevant to approaches to substance use treatment from a national perspective. (PHAC, 2010b: 9) (italics added).

Obscure, technocratic language was an effective depoliticizing tool, and a salient feature of public health campaigns leading readers to imagine armies of experts working tirelessly behind the scenes to meet community needs. Expert voices recommended ‘critical’ changes without even a nod to a true transformation of social hierarchies. These quotations illustrate well how, as the politics of the settler-colonial state is buried in bureaucratic details, ongoing relations and structures shaping health inequities are deemed unworthy of further scrutiny and framed as ‘technical’ problems better dealt by experts (Navarro, 1984).

Yet another source of authoritativeness, especially in public health documents, was the seemingly apolitical numerical language through which, for instance, public health experts communicated the costs of FASD-affected individuals on society – in health services, services for special-needs children and youth, subsidized housing, long-term care and losses to the economy (Popova et al., 2016). These documents appeared strikingly factual:

The costs totaled approximately $1.8 billion (from about $1.3 billion as the lower estimate up to $2.3 billion as the upper estimate). The highest contributor to the overall FASD-attributable cost was the cost of productivity losses due to morbidity and premature mortality, which accounted for 41% ($532 million–$1.2 billion) of the overall cost. The second highest contributor [. . .] was the cost of corrections, accounting for 29% ($378.3 million). The third highest contributor was the cost of health care at 10% ($128.5–$226.3 million). (Popova et al., 2016: 367)

Indeed, this quotation offers seemingly unassailable evidence on the cost of FASD. Upon closer examination, however, assumptions are questionable: concerns with ‘productivity loss’ take for granted that it is critical for human beings to produce exchange-value, so it follows that persons with disabilities are both ‘unproductive’ and ‘costly’ – a societal burden. This framing guarantees that anything approaching ‘radical social interventions’ – guaranteed housing, food or health care to meet the needs of FASD affected populations – is at best optional, at worst wasteful. While drawing readers’ attention to the cost of the interaction of the FASD population with the criminal system, the quotation selectively, and with no argument justifiable by expertise, ignores the significant profits yielded by outsourced services feeding into this system, as well as the ‘functional’ benefits for the better off of the criminalization of poverty (Gans, 1972).

A final, very effective tool of depoliticizing FASD was not what these documents included but what they omitted, omissions that can only be identified searching beyond dominant narratives. To mention a few, omissions included the societal costs of the destruction of indigenous food systems, of corporate theft of water from unceded territories and of fracking and pipeline construction, in addition to costs incurred by the health effects of these actions. Not to mention the taxpayer costs of corporate subsidies that often outweigh whatever ‘productivity losses’ may be incurred by individuals, a telling example being the multibillion-dollar oil and gas industry bailout that the federal government is preparing as we write (Fife et al., 2020). In sum, seemingly nonideological cost of illness calculations convey the very ideological notion that state-sponsored activities are neutral and have the public good at heart – despite the substantial evidence against this notion (Chartrand, 2019) and while redirecting the public’s attention to FASD individuals and away from the costly omitted factors.

Discussion

Our investigation of messages on FASD overall and at its intersection with indigeneity identified three key themes: (1) FASD can be addressed if ‘we’, that is, experts supported by affected communities and society at large, can persuade women during their fertile years not to drink; (2) experts informing policy have the best interest of FASD-affected communities at heart; and (3) experts are the best informants of evidence-based policies. Our interpretation is supported by the lack of evidence for attempts to incorporate FASD affected individuals or their families as agents in formulating policy and by the many basic needs that remain unmet to this day – needs such as proper housing, access to water, adequate nutrition, income support to compensate for the significant costs of raising FASD affected children (Finkel, 2005) – that clearly cannot be satisfied through psychological or behavioural interventions.

Be that as it may, this simple, ostensibly benign and authoritative message set invisible yet effective boundaries to which policies were considered worthy of debate, whether they involved providing support to the ‘damaged lives of the people who currently suffer from FASD and their families’ (Finkel, 2005: 327) or reached beyond them to challenge the institutional status quo. Mentions of socio-historical contexts turned colonial subjects into agents of their own oppression, often suggesting that mothers who drink merely maladapt to adversity, concealing neocolonial and capitalist social relations under a veneer of benevolence and promoting interventions overwhelmingly aimed at correcting affected individuals, families and communities – their beliefs, their emotions, their behaviours – effectively guaranteeing the reproduction of FASD inequities.

We also note that the narratives we identified convey a clear ideological message to audiences who, even as they are prodded to sympathize with indigenous people, develop a ‘common sense’ of FASD as a feature of indigeneity rooted in the responsibility of women or, at best, their communities. This ‘common sense’ allows the settler-colonial state to perpetrate capitalist exploitation with a façade of benevolence, seemingly promoting the ‘development’ of indigenous peoples, while rendering unintelligible the continuing high incarceration rates, poor health and education outcomes and ‘intergenerational’ trauma ostensibly refractory to evidence-based interventions (Chartrand, 2019; Huseman and Short, 2012).

With that being said, we do not intend to blame individuals who may have drafted the analysed documents, who likely have the best intentions regarding the wellbeing of mothers-to-be, their offspring and their communities. Nor do we deny some positive dimensions of these narratives – denouncing the stigmatization of mothers-to-be, calling for culturally competent services and promoting professional training to recognize experiences of oppression. Rather, we intend to analyse the objective consequences of social practices, including discourses, that is, the latent functions of social action regardless of what the manifest functions, that is, the implicit or explicit intentions of social actors, may be (Chaufan and Saliba, 2019; Gans, 1972; Merton, 1957). As such we argue that dominant discourses convey ostensibly progressive messages that reproduce settler-colonial relations with the blessings of the public and, oftentimes, the colonized.

We conclude that almost 50 years after FASD was diagnosed as a medical condition, and experienced definitional transitions between a medical diagnosis, a public health concern, a moral failure of mothers, a defect of certain communities, a footnote in the lives of dangerous criminals or varying combinations of all these (Golden, 1999), dominant framings of FASD and indigeneity disable the better off from imagining policies capable of meeting the predictable material, emotional and economic needs of those who are left behind by a profit-driven, hierarchical social system. The inability of this system to meet even the most basic needs of billions in the midst of an increasing and dramatic concentration of wealth (Hardoon et al., 2016; World Bank, 2016), has only been exacerbated, albeit not created, by COVID-19 (Navarro, 2021).

So how could and should those of us who enjoy the privilege of conducting research on, reading or promoting policies concerning FASD address such needs? A modest beginning would involve calling for not only counselling services to address women’s drinking habits – however helpful these may be – but actually providing these women, families and communities the myriad unmet needs (Finkel, 2005) – basic social determinants of health such as housing, good nutrition, equitable access to quality health services and ‘compensation for the extra expenses incurred in raising a special needs child’ (Golden, 1999: 286). We raise however a word of caution at attempts to reform the capitalist, settler-colonial state: even under best-case scenarios, settler-colonial relations cannot offset the inequities that these relations produce, relations that can, and often do, stand in the way of anti-colonial and revolutionary transformation (Waitzkin, 2017). As Lorde (1984) teaches us, ‘The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change’ (p. 111).

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-hea-10.1177_13634593211038527 for ‘Think before you drink’: Challenging narratives on foetal alcohol spectrum disorder and indigeneity in Canada by Nora Yousefi and Claudia Chaufan in Health:

Author biographies

Nora Yousefi, MA MPP (Health Policy), is a researcher of Health Policy and Global Health at York University and a past Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council Scholar. Her research interests include the social and health implications of settler colonialism, capitalism, and imperialism.

Claudia Chaufan, MD PhD (Sociology/Philosophy), is Associate Professor of Health Policy and Global Health at York University, past US Fulbright Scholar, past Health Graduate Program Director, and current Special Advisor to the Health Dean in Curriculum Internationalization. Prof. Chaufan’s research is grounded in the tradition of Marxist critical social studies. She has published widely, in academic and popular outlets, is editorial board member of leading peer-reviewed journals, and is actively involved with organizations working on antiwar, anti-colonial and anti-imperialist struggles.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Nora Yousefi  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1347-4649

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1347-4649

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Alfred (2005) Wasáse: Indigenous Pathways of Action and Freedom. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Badry D, Felske AW. (2013) An examination of the social determinants of health as factors related to health, healing and prevention of foetal alcohol spectrum disorder in a northern context – the brightening our home fires project, Northwest Territories, Canada. International Journal of Circumpolar Health 72(1): 21140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker AJ. (2012) Locating settler colonialism. Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History 13(3). [Google Scholar]

- Barker AJ, Rollo A, Battell Lowman E. (2016) Settler colonialism and the consolidation of Canada in the twentieth century. In: Veracini L, Cavanagh E. (eds) The Routledge Handbook of the History of Settler Colonialism. London: Taylor & Francis, pp.173–188. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter P, Jack S. (2008) Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. The Qualitative Report 13(4): 544–559. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen GA. (2009) Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal 9(2): 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V. (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2): 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- CAMH (n.d.) Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD). Available at: https://www.camh.ca/en/health-info/mental-illness-and-addiction-index/fetal-alcohol-spectrum-disorder (accessed 1 January 2020).

- Campbell RA. (2008) Making sober citizens: The legacy of indigenous alcohol regulation in Canada, 1777-1985. Journal of Canadian Studies 42(1): 105–126. [Google Scholar]

- Chartrand V. (2019) Unsettled times: Indigenous incarceration and the links between colonialism and the penitentiary in Canada. Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice 61: 67–89. [Google Scholar]

- Chaufan C. (2006) Sugar Blues: Issues and Controversies Concerning the Type 2 Diabetesepidemic. Santa Cruz, CA: University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Chaufan C, Constantino S, Davis M. (2012) ‘It’s a full time job being poor’: Understanding barriers to diabetes prevention in immigrant communities in the USA. Critical Public Health 22(2): 147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Chaufan C, Saliba D. (2019) The global diabetes epidemic and the nonprofit state corporate complex: Equity implications of discourses, research agendas, and policy recommendations of diabetes nonprofit organizations. Social Science & Medicine 223: 77–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrisjohn RD, Young S, Maraun M. (2003) The Circle Game: Shadows and Substance in the Indian Residential School Experience in Canada. Penticton, BC: Theytus Books. [Google Scholar]

- Chudley AE, Conry J, Cook JL, et al. (2005) Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: Canadian guidelines for diagnosis. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal 172(5 Suppl.): S1–S21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulthard GS. (2014) Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Daschuk JW. (2013) Clearing the Plains: Disease, Politics of Starvation, and the Loss of Aboriginal Life, vol. 65. Regina: University of Regina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Devens C. (1992) Countering Colonization: Native American Women and Great Lakes Missions, 1630-1900. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Director of Family and Child Services v. M.B. (2003) No. 53324 Provincial Court of British Columbia, 11 December. Available at: http://canlii.ca/t/1g7cm (accessed 6 October 2019).

- Fairclough N. (1993) Critical discourse analysis and the marketization of public discourse: The universities. Discourse & Society 4(2): 133–168. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough N. (2013) Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- FAS/FAE Technical Working Group (2001) It takes a community: Framework for the First Nations and Inuit fetal alcohol syndrome and fetal alcohol effects initiative. Ottawa, ON: Health Canada, First Nations and Inuit Health Branch. [Google Scholar]

- Fife R, Graney E, Cryderman K. (2020) Ottawa prepares multibillion-dollar bailout of oil and gas sector. The Globe and Mail, 20 March. Available at: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/politics/article-ottawa-prepares-multibillion-dollar-bailout-of-oil-and-gas-sector/ (accessed 21 March 2020).

- Finkel A. (2005) Review of message in a bottle: The making of fetal alcohol syndrome [Review of Review of message in a bottle. The Making of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome, by J. Golden]. Labour/Le Travail 56: 325–328. [Google Scholar]

- Gans HJ. (1972) The positive functions of poverty. American Journal of Sociology 78(2): 275–289. [Google Scholar]

- Gindin S, Panitch L. (2012) The Making of Global Capitalism. London: Verso Books. [Google Scholar]

- Godderis R, Stephenson Z. (2017) Preventing tragedy in Canada? Risk and responsibility in government discourses about alcohol consumption and pregnancy. Journal of Women Politics & Policy 38(3): 276–297. [Google Scholar]

- Golden J. (1999) “An argument that goes back to the womb”: The demedicalization of fetal alcohol syndrome, 1973-1992. Journal of Social History 33(2): 269–298. [Google Scholar]

- Gramsci A. (2011) Prison Notebooks, Volumes 1-3. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hardoon D, Fuentes-Nieva R, Ayele S. (2016) An Economy for the 1%: How Privilege and Power in the Economy Drive Extreme Inequality and How This Can Be Stopped. Oxford: Oxfam International. [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada (2006) It’s Your Health: Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder. Ottawa: Government of Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Herman ES, Chomsky N. (1988) Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media. New York, NY: Pantheon Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hunting G, Browne AJ. (2012) Decolonizing policy discourse: Reframing the ‘Problem’ of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Available at: https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/handle/1807/32417 (accessed 11 June 2019).

- Huseman J, Short D. (2012) ‘A slow industrial genocide’: Tar sands and the indigenous peoples of northern Alberta. The International Journal of Human Rights 16(1): 216–237. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferies K, Goldberg L, Aston M, et al. (2018) Understanding the invisibility of black nurse leaders using a black feminist poststructuralist framework. Journal of Clinical Nursing 27(15–16): 3225–3234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorde A. (1984) The Master’s tools will never dismantle the Master’s house. In: Lorde A. (ed.) Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, 2007th edn. New York, NY: Crossing Press, pp.110–114. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald C, Steenbeek A. (2015) The impact of colonization and western assimilation on health and wellbeing of Canadian aboriginal people. International Journal of Regional and Local History 10(1): 32–46. [Google Scholar]

- Merton RK. (1957) Manifest and Latent Functions. Social Theory and Social Structure. Glencoe: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mgbeoji I. (2006) Global Biopiracy: Patents, Plants, and Indigenous Knowledge. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morin B. (2020) Canada at “tipping point” over Wet’suwet’en land dispute. Aljazeera, 21 February. Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/2/21/canada-at-tipping-point-over-wetsuweten-land-dispute (accessed 21 February 2020).

- Navarro V. (1984) A critique of the ideological and political positions of the Willy Brandt report and the WHO Alma Ata declaration. Social Science & Medicine 18(6): 467–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro V. (2009) What we mean by social determinants of health. International Journal of Health Services 39(3): 423–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro V. (2021) Why Asian countries are controlling the pandemic better than the United States and Western Europe. International Journal of Health Services 51(2): 261–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neeganagwedgin E. (2012) “Chattling the Indigenous Other” A historical examination of the enslavement of aboriginal peoples in Canada. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 8(1): 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- NWAC (2010) What Their Stories Tell Us: Research Findings From the Sisters In Spirit Initiative. Ohsweken: Native Women’s Association of Canada. [Google Scholar]

- OFIFC (2008) FASD TOOL KIT for Aboriginal Families. Toronto: OFIFC. [Google Scholar]

- Pegoraro L. (2015) Second-rate victims: The forced sterilization of indigenous peoples in the USA and Canada. Settler Colonial Studies 5(2): 161–173. [Google Scholar]

- PHAC (2005. a) Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD). Available at: https://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.item?id=H39-4-20-2003-eng&op=pdf&app=Library (accessed 20 September 2019).

- PHAC (2005. b) Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD): A Framework for Action. Ottawa: Health Canada. [Google Scholar]

- PHAC (2006. e) Research Update: Alcohol Use and Pregnancy: An Important Canadian Public Health and Social Issue (Dell CA, Roberts G, eds). Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada. [Google Scholar]

- PHAC (2010. b) Assessment and Diagnosis of FASD Among Adults: A National and International Systematic Review. Public Health Agency of Canada. Available at: http://ra.ocls.ca/ra/login.aspx?inst=centennial&url=https://www.deslibris.ca/ID/227953 [Google Scholar]

- Popova S, Lange S, Burd L, et al. (2016) The economic burden of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder in Canada in 2013. Alcohol and Alcoholism 51(3): 367–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon A. (2011) Aboriginal mothering, FASD prevention and the contestations of neoliberal citizenship. Critical Public Health 21(2): 165–178. [Google Scholar]

- Shahram SZ, Bottorff JL, Oelke ND, et al. (2017) Mapping the social determinants of substance use for pregnant-involved young aboriginal women. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being 12(1): 1275155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steckley J, Cummins BD. (2001) Full Circle: Canada’s First Nations. Toronto: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Tait CL. (2003. a) Fetal Alcohol Syndrome Among Aboriginal People in Canada: Review and Analysis of the Intergenerational Links to Residential Schools. Ottawa: Aboriginal Healing Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Tait CL. (2003. b) “The Tip of the Iceberg” The “Making” of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome in Canada. Montreal: McGill University. [Google Scholar]

- Valverde M. (1998) Diseases of the Will: Alcohol and the Dilemmas of Freedom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Veracini L. (2010) Settler Colonialism: A Theoretical Overview. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Veracini L. (2011) Introducing: Settler colonial studies. Settler Colonial Studies 1(1): 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Waitzkin H. (2017) Revolution now. Monthly Review 69(6): 18. [Google Scholar]

- Waitzkin H, Jasso-Aguilar R. (2015) Imperialism’s health component. Monthly Review 67(3): 114. [Google Scholar]

- Warburton R, Scott S. (1985) The fur trade and early capitalist development in British Columbia. The Canadian Journal of Native Studies 5(1): 27. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe P. (2006) Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native. Journal of Genocide Research 8(4): 387–409. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank (2016) Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2016: Taking on Inequality. Washington, DC: World Bank Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Young MG, Manion K. (2017) Harm reduction through housing first: An assessment of the emergency warming centre in Inuvik, Canada. Harm Reduction Journal 14(1): 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zingel A. (2019) Indigenous Women Come Forward With Accounts of Forced Sterilization, Says Lawyer. CBC, 18 April. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-hea-10.1177_13634593211038527 for ‘Think before you drink’: Challenging narratives on foetal alcohol spectrum disorder and indigeneity in Canada by Nora Yousefi and Claudia Chaufan in Health: