Highlights

-

•

About 9 out of 10 parents in Colombia and Peru intend to vaccinate their children and adolescents against COVID-19.

-

•

Colombia: being vaccinated, 35 to 54 years old, maintaining physical distance, using masks, having economic insecurity, anxiety, and comorbidities increased the intention of vaccinating children and adolescents.

-

•

Peru: being vaccinated, female, maintaining physical distancing, using a mask, having economic insecurity, comorbidities, and have had COVID-19 increased the intention to vaccinate children and adolescents.

-

•

Peru: living in a town, village or rural area was associated with reducing the intention to vaccinate children and adolescents.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19 Vaccines, Vaccination Refusal, Vaccination, Child, Adolescent, Parents, Colombia, Peru

Abstract

We aimed to estimate the prevalence and factors associated with parents’ non-intention to vaccinate their children and adolescents against COVID-19 in Colombia and Peru. We performed a secondary analysis using a database generated by the University of Maryland and Facebook (Facebook, Inc). We Included adult (18 and over) Facebook users residing in LAC who responded to the survey between May 20, and November 5, 2021. We Included sociodemographic characteristics, comorbidities, mental health, economic and food insecurity, compliance with mitigation strategies against COVID-19, and practices related to vaccination against this disease. We estimated crude (cPR) and adjusted (aPR) prevalence ratios with their respective 95 %CI. We analyzed a sample of 44,678 adults from Colombia and 24,302 from Peru. The prevalence of parents' non-intention to vaccinate their children and adolescents against COVID-19 was 7.41 % (n = 3,274) for Colombia and 6.64 % (n = 1,464) for Peru. In Colombia, age above 35 years old, compliance with physical distancing, use of masks, having economic insecurity, anxiety symptoms, having a chronic condition or more comorbidities, and being vaccinated were associated with a higher probability of vaccinating children and adolescents against COVID-19. In Peru, female gender, compliance with physical distancing, use of masks, having economic insecurity, anxiety symptoms, having a chronic condition or more comorbidities, having had COVID-19, and being vaccinated were associated with a higher probability of vaccinating children against COVID-19. Living in a town, a village, or a rural area was associated with a higher prevalence of non-intention to vaccinate children and adolescents against COVID-19. About 9 out of 10 parents in Colombia and Peru intend to vaccinate their children and adolescents against COVID-19. This intention is associated with some factors which are similar between the two countries, as well as other factors and variations among the different regions of each country.

Introduction

The most cost-effective strategy for controlling the COVID-19 pandemic is to achieve global vaccination coverage of at least 70 to 90 % [1]. Vaccines against COVID-19 are not only safe but have also been shown to reduce hospitalizations, the use of ventilation, health care costs, mortality, as well as viral transmission [2], [3], [4], [5]. Although initially there was controversy about vaccination in the child population due to the relatively low incidence, severity, and limited spread of the disease in this age group, it is currently considered essential to achieve herd immunity [6]. Similarly, it is necessary to ensure the return to regular school learning and prevention against severe cases in children, as well as long-term consequences such as post-COVID-19 syndrome [7].

In October 2021, the Food and Drug Administration authorized the BioNTech vaccine for emergency use in children from 5 to 11 years of age [8]. Although this vaccine remains under surveillance and continuous monitoring, it has been demonstrated to be safe and effective in this population [9]. Nonetheless, investigations at a world level have suggested that some parents reject vaccination due to false information reported by the media [10], [11], leading to uncertainty regarding the safety and efficacy of the vaccines [12].

Although 9 out of 10 parents in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) intend to vaccinate their children, there are factors associated with the non-intention to vaccinate [13]. The proportion of parents who do intend to vaccinate their children is encouraging despite being one of the continents with the highest degree of misinformation and low adherence to the control recommendations of the pandemic [14]. However, this vaccination intention varies among the regions of each country, and each country has factors associated with its social determinants or its health systems.

There are differences among the regions of Peru concerning the intention of the adult population to be vaccinated against COVID-19 [15], being lower in older adults [16]. A study in Colombia showed lower vaccination acceptance in adults than in the Peruvian population [17], with important variations among its regions as in Peru [18]. These results suggest that the intention to vaccinate in different countries varies according to the sociodemographic context and age [19], [20], [21], [22], [23]. Likewise, fear, socioeconomic conditions, and institutional situations can also intervene in compliance with vaccination [24], [25].

Therefore, while some studies have evaluated the vaccination intention in LAC countries [13], there may be variations within these countries that warrant strategies to achieve adequate coverage in children and adolescents. Therefore, the objective of the present study was to evaluate the factors associated with the non-intention to vaccinate children and adolescents in Peru and Colombia and the variations of this intention among the different regions of these two countries.

Methods

Study design

We performed a secondary analysis using a database generated by the University of Maryland and Facebook (Facebook, Inc). Both institutions designed a survey to assess sociodemographic characteristics, comorbidities, mental health, economic and food insecurity, compliance with mitigation strategies against COVID-19, and practices related to vaccination against this disease. Since April 23, 2020, this survey has been carried out daily in more than 200 countries and in the primary language of the territory. The sampling frame for the random selection of participants Included daily Facebook users over 18 years of age from a particular region and country. The selection of the surveyed participants was random based on the sampling frame that was recalculated daily. If a Facebook user refused to participate, another was randomly invited within the sampling frame. Participants could only answer the survey once within an eight-week time frame. This survey has been used to develop previous studies [26], and the survey methodology has been described in greater detail elsewhere [27].

Population and sample

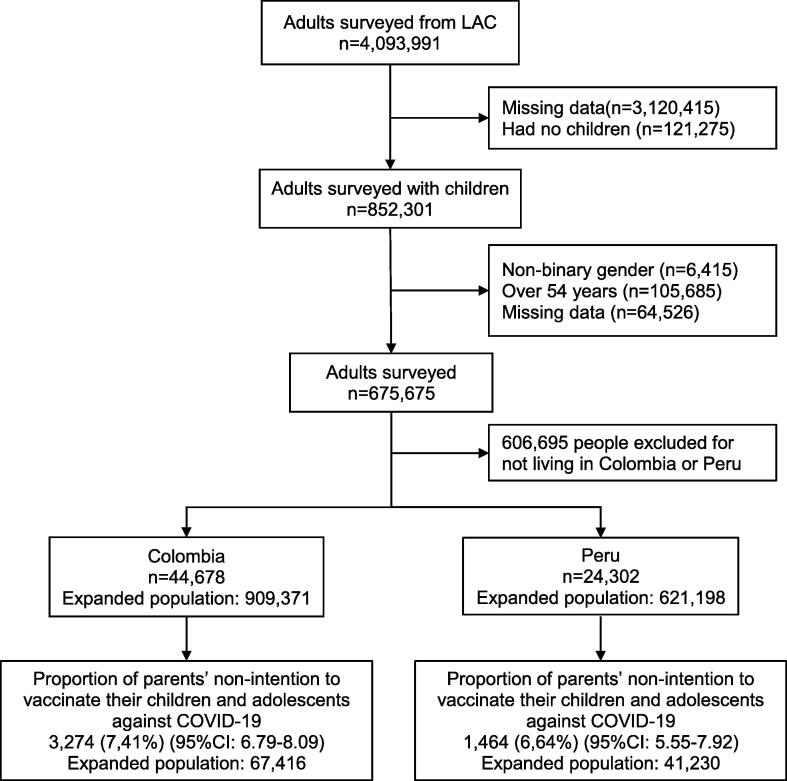

We included adult (18 and over) Facebook users residing in LAC who responded to the survey between May 20 and November 5, 2021. We excluded participants who did not have the variables of interest, who did not have children, those of non-binary gender, and those over 54 years of age. We excluded participants over 54 years of age to reduce the probability of not exclusively including parents of children under 18 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the study sample selection.

Variables and measures

Outcome variable: The outcome variable was parents’ non-intention to vaccinate their children and adolescents against COVID-19.

We evaluated the parents’ intention to vaccinate their children and adolescents against COVID-19 using the survey question: Will you choose to get a COVID-19 vaccine for your child or children when they are eligible? This question has four possible alternatives: yes, definitely; yes, probably; no, probably not; and no, definitely not. Subsequently, we dichotomized the variable considering the first two alternatives as to the parents’ intention to vaccinate their children and adolescents, while the last two were considered non-intention.

Independent variables

Sociodemographic variables

We included the following sociodemographic variables (the survey question related to the study variables and the categories considered for these variables in the study are shown in parenthesis): gender (What is your gender?; male, female), age (What is your age?; 18 to 24 years, 25 to 34, 35 to 44, 45 to 54), educational level (What is the highest level of education that you have completed?; university post-graduate degree completed/university completed/college/pre-university, secondary school completed/high school (or equivalent) completed, primary school completed/less than primary school/no formal schooling) and area of residence (Which of the following best describes the area where you currently live?; city, town, village or rural area). Town was defined as a populated area with fixed boundaries and a local self-government; city was defined as an important or a large town; and village was defined as a group of houses and other buildings, usually in the countryside, smaller than a town.

Comorbidities, personal and COVID-19 history

Participants self-reported the following comorbidities (survey question: Have you ever been told by a doctor, nurse, or another health professional that you have any of the following medical conditions?): asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or chronic bronchitis or emphysema, cancer, diabetes, high blood pressure, kidney disease, compromised or weakened immune system, heart attack or another heart disease, and obesity. We generated a variable that groups the comorbidities in 0, 1, 2, or more.

We also included self-reporting of being a smoker (yes, no), having had COVID-19 (yes, no), and having been vaccinated against COVID-19 (yes, no).

Compliance with community mitigation strategies

The community mitigation strategies included were physical distancing and mask use during the last seven days. We defined physical distancing as when a participant reported having intentionally avoided contact with other people at least at some point in the last seven days (survey question: In the past 7 days, how often did you intentionally avoid contact with other people?). In addition, the use of masks was defined if a participant reported wearing a mask in public at least at some point during the last seven days (survey question: In the past 7 days, how often did you wear a mask when in public?).

Food and economic insecurity

We assessed food insecurity with the survey question: How worried are you about having enough to eat in the next week? This question had four possible answers: very worried, somewhat worried, not too worried, and not worried at all. We considered the first three responses as food insecurity.

We defined economic insecurity using the survey question: How worried are you about your household’s finances in the next month? There were four response alternatives: very worried, somewhat worried, not too worried, and not worried at all. We defined economic insecurity using the first three responses.

Anxiety and depressive symptoms

We evaluated anxiety symptoms using the survey question: During the last seven days, how often did you feel so nervous that nothing could calm you down? This question is part of the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10), and the survey has five response alternatives: all the time, most of the time, some of the time, a little of the time, and none of the time. Therefore, we dichotomized the variable considering the first four alternatives as to the presence of anxiety symptoms.

We evaluated depressive symptoms using the survey question: How often did you feel so depressed that nothing could cheer you up in the past seven days? This question is part of the K10 and has five response alternatives: all the time, most of the time, some of the time, a little of the time, and none of the time. Therefore, we dichotomized the variable considering the first four alternatives as to the presence of depressive symptoms.

Statistical analysis

We downloaded the databases in Microsoft Excel 2016 ® format and imported them into the statistical package Stata/SE ® version 17.0 (StataCorp, TX, USA). Then, we performed the statistical analysis considering the complex sampling of the survey and the svy command.

We performed a descriptive analysis using absolute frequencies and weighted proportions with their respective 95 % confidence intervals (95 %CI). We used the Chi-square test with Rao-Scott correction to perform the bivariate analysis between the independent variables and the parents’ non-intention to vaccinate their children and adolescents against COVID-19. Two generalized linear models (crude and adjusted) of the Poisson family with a logarithmic link function were used to estimate the factors associated with the parents’ non-intention to vaccinate their children and adolescents against COVID-19. Crude (cPR) and adjusted (aPR) prevalence ratios with their respective 95 %CI were estimated. The adjustment for confounders was carried out according to an epidemiological approach based on other studies [13], after evaluating the collinearity of the associated factors included in the final adjusted model. We evaluated the possible collinearity of the associated factors included in the final adjusted model. A p-value<0.05 was considered statistically significant in all the analyses.

Ethical considerations

All participants gave their informed consent before answering the survey. This study analyzed a secondary database that collected data without identifiers and did not violate the integrity of the participants. The database is not open access; the authors of this study achieved access after obtaining a signed agreement with the University of Maryland.

Results

We analyzed a sample of 44,678 adults from Colombia and 24,302 adults from Peru (Fig. 1).

Colombia

Characteristics of the study sample in Colombia

In the Colombia study sample, 55.44 % were female, 33.19 % were between 35 and 44 years old, 53 % had completed secondary education or less, 60.88 % lived in a city, and 10.78 % reported smoking. Regarding prevention measures, 89.45 % and 92.27 % had complied with physical distancing and the use of a mask, respectively. Food insecurity was reported by 72.49 %, and 86.61 % reported having economic insecurity. In addition, 35.82 % and 42.51 % described having anxiety and depressive symptoms, respectively; 65.27 % of the participants did not report comorbidities, 47.53 % were not yet vaccinated against COVID-19, and 35.79 % had had COVID-19 at some point. In Colombia, the prevalence of parents' non-intention to vaccinate their children and adolescents against COVID-19 was 7.41 % (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive analysis of the study samples in Colombia (n = 44,678; N = 909,371) and Peru (n = 24,302; N = 621,198).

| Characteristics |

Colombia |

Peru |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute frequency of participants surveyed | Weighted proportion according to each category | Absolute frequency of participants surveyed | Weighted proportion according to each category | |||

| n | % | 95 %CI | n | % | 95 %CI | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 18,933 | 44.56 | 43.51–45.63 | 11,716 | 47.18 | 43.43–50.98 |

| Female | 25,745 | 55.43 | 54.37–56.49 | 12,586 | 52.81 | 49.02–56.57 |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 18–24 | 4,167 | 11.69 | 11.14–12.26 | 2,837 | 10.95 | 10.07–11.90 |

| 25–34 | 13,269 | 30.89 | 29.97–31.84 | 6,793 | 28.99 | 28.01–30.00 |

| 35–44 | 17,129 | 33.19 | 32.62–33.76 | 8,184 | 33.00 | 32.19–33.83 |

| 45–54 | 10,113 | 24.22 | 23.06–25.43 | 6,488 | 27.04 | 25.68–28.45 |

| Educational level | ||||||

| University post-graduate degree completed/university completed/college/pre-university | 18,796 | 36.97 | 34.74–39.26 | 13,243 | 52.00 | 47.92–55.02 |

| Secondary school completed/High school (or equivalent) completed | 22,023 | 52.99 | 51.22–54.75 | 10,402 | 45.1 | 41.49–48.77 |

| Primary school completed/Less than primary school/No formal schooling | 3,859 | 10.03 | 9.23–10.90 | 657 | 3.41 | 2.74–4.25 |

| Area of residence | ||||||

| City | 30,156 | 60.88 | 50.67–70.22 | 19,340 | 75.97 | 66.21–83.62 |

| Town | 10,578 | 28.68 | 21.63–36.95 | 2,793 | 13.24 | 8.67–19.73 |

| Village or rural area | 3,944 | 10.43 | 8.00–13.50 | 2,169 | 10.77 | 7.84–14.63 |

| Smoking | ||||||

| No | 39,321 | 89.21 | 86.37–91.53 | 21,365 | 88.60 | 87.79–89.38 |

| Yes | 5,357 | 10.78 | 8.47–13.63 | 2,937 | 11.39 | 10.62–12.21 |

| Compliance with physical distancing | ||||||

| No | 4,396 | 10.54 | 9.97–11.16 | 2,138 | 9.61 | 8.80–10.49 |

| Yes | 40,282 | 89.45 | 88.84–90.03 | 22,164 | 90.38 | 89.51–91.20 |

| Compliance with mask use | ||||||

| No | 3,188 | 7.72 | 6.99–8.52 | 1,337 | 6.06 | 5.33–6.89 |

| Yes | 41,490 | 92.27 | 91.48–93.01 | 22,965 | 93.93 | 93.11–94.67 |

| Food insecurity | ||||||

| No | 13,202 | 27.50 | 0.25–0.30 | 6,145 | 23.73 | 21.98–25.59 |

| Yes | 31,476 | 72.49 | 0.70–0.75 | 18,157 | 76.26 | 74.41–78.02 |

| Economic insecurity | ||||||

| No | 6,558 | 13.38 | 0.12–0.15 | 2,603 | 10.04 | 9.43–10.70 |

| Yes | 38,120 | 86.61 | 0.85–0.87 | 21,699 | 89.95 | 89.30–90.57 |

| Anxiety symptomatology | ||||||

| No | 28,196 | 64.17 | 0.63–0.65 | 14,040 | 57.68 | 55.88–59.47 |

| Yes | 16,482 | 35.82 | 0.35–0.36 | 10,262 | 42.31 | 40.53–44.12 |

| Depressive symptomatology | ||||||

| No | 25,303 | 57.48 | 0.56–0.59 | 12,227 | 49.99 | 48.43–51.56 |

| Yes | 19,375 | 42.51 | 0.41–0.44 | 12,075 | 50.00 | 48.44–51.57 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| No | 28,544 | 65.27 | 0.64–0.66 | 14,852 | 62.81 | 60.38–65.18 |

| Yes | 16,144 | 24.87 | 0.24–0.26 | 9,450 | 26.00 | 25.11–28.02 |

| Vaccinated | ||||||

| No | 22,311 | 47.52 | 0.46–0.49 | 13,340 | 53.70 | 50.54–56.85 |

| Yes | 22,367 | 52.47 | 0.51–0.54 | 10,962 | 46.29 | 43.15–49.46 |

| Had COVID-19 | ||||||

| No | 28,949 | 64.20 | 0.62–0.66 | 13,438 | 54.08 | 52.14–56.02 |

| Yes | 15,729 | 35.79 | 0.34–0.38 | 10,864 | 45.91 | 43.98–47.86 |

| Parents’ intention to vaccinate their children and adolescents against COVID-19 | ||||||

| Yes | 41,404 | 92.59 | 91.91–93.21 | 22,838 | 93.36 | 92.08–94.45 |

| No | 3274 | 7.41 | 6.79–8.09 | 1464 | 6.64 | 5.55–7.92 |

95 %CI: 95 % Confidence Intervals.

Prevalence of parents’ non-intention to vaccinate their children and adolescents against COVID-19 according to each region of Colombia

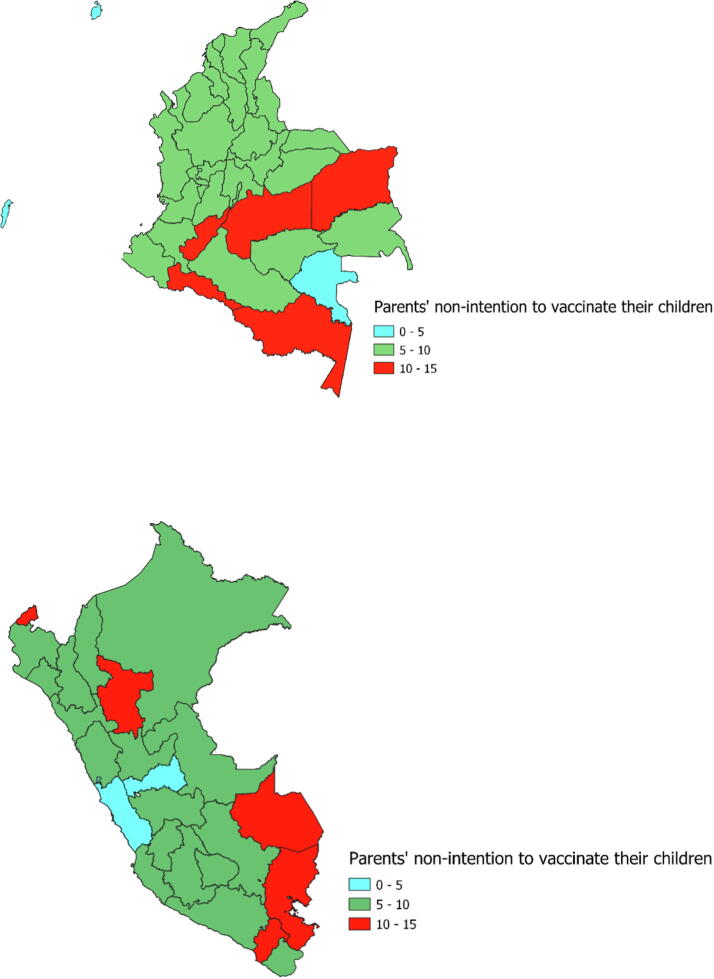

In Colombia, the regions with the highest prevalence of parentś non-intention to vaccinate children against COVID-19 were Amazonas (14.95 %), Putumayo (13.72 %), and Vichada (12.96 %), while the lowest prevalence of non-intention to vaccinate children against COVID-19 was in Vaupés (0 %), San Andrés and Providencia (0.27 %), and Bolivar (5.33 %) (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

Prevalence of parents' non-intention to vaccinate their children and adolescents against COVID-19 in the regions of Colombia and Peru.

Bivariate analysis according to parents’ non-intention to vaccinate their children and adolescents against COVID-19 in Colombia

We found statistically significant differences for age, level of education, compliance with physical distancing and use of a mask, economic insecurity, anxiety symptoms, presenting comorbidities, and having been vaccinated (Table 2).

Table 2.

Bivariate analysis of the characteristics of the study sample according to parentś intention to vaccinate their children and adolescents against COVID-19 in Colombia and Peru.

| Characteristics |

Colombia |

Peru |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Parents’ intention to vaccinate their children adolescents against COVID-19 |

Parents’ intention to vaccinate their children and adolescents against COVID-19 |

|||||||||||||

| Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

|||||||||||

| Absolute frequency of participants surveyed |

Weighted proportion according to each category |

Absolute frequency of participants surveyed |

Weighted proportion according to each category |

p-value |

Absolute frequency of participants surveyed |

Weighted proportion according to each category |

Absolute frequency of participants surveyed |

Weighted proportion according to each category |

p-value |

|||||

| n | % | 95 %CI | n | % | 95 %CI | n | % | 95 %CI | n | % | 95 %CI | |||

| Gender | 0.457 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| Male | 17,642 | 92.75 | 92.02–93.43 | 1,291 | 7.24 | 6.57–7.98 | 10,916 | 92.22 | 90.61–93.57 | 800 | 7.77 | 6.43–9.39 | ||

| Female | 23,762 | 92.44 | 91.59–93.23 | 1,983 | 7.55 | 6.77–8.41 | 11,922 | 94.38 | 93.44–95.20 | 664 | 5.61 | 4.80–6.56 | ||

| Age (years) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| 18–24 | 3,698 | 89.29 | 87.64–90.75 | 469 | 10.7 | 9.25–12.36 | 2,642 | 92.07 | 89.46–94.09 | 195 | 7.92 | 5.91–10.54 | ||

| 25–34 | 12,075 | 91.10 | 90.30–91.85 | 1,194 | 8.89 | 8.15–9.70 | 6,312 | 91.75 | 89.95–93.26 | 481 | 8.24 | 6.74–10.05 | ||

| 35–44 | 16,056 | 93.58 | 92.85–94.24 | 1,073 | 6.41 | 5.76–7.15 | 7,732 | 93.98 | 92.81–94.97 | 452 | 6.01 | 5.03–7.19 | ||

| 45–54 | 9,575 | 94.69 | 93.79–95.48 | 538 | 5.30 | 4.52–6.21 | 6,152 | 94.85 | 93.95–95.62 | 336 | 5.14 | 4.38–6.05 | ||

| Educational level | <0.001 | 0.018 | ||||||||||||

| University post-graduate degree completed/university completed/college/pre-university | 17,619 | 93.55 | 92.97–94.10 | 1,177 | 6.44 | 5.90–7.02 | 12,505 | 93.88 | 92.81–94.80 | 738 | 6.11 | 5.20–7.19 | ||

| Secondary school completed/High school (or equivalent) completed | 20,294 | 92.12 | 91.41–92.78 | 1,729 | 7.87 | 7.22–8.59 | 9,736 | 92.96 | 91.31–94.32 | 666 | 7.03 | 5.68–8.69 | ||

| Primary school completed/Less than primary school/No formal schooling | 3,491 | 91.46 | 89.50–93.09 | 368 | 8.53 | 6.91–10.50 | 597 | 90.86 | 86.78–93.78 | 60 | 9.13 | 6.22–13.22 | ||

| Area of residence | 0.054 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| City | 28,051 | 92.94 | 92.13–93.67 | 2,105 | 7.05 | 6.32–7.87 | 18,291 | 94.09 | 93.11–94.94 | 1,049 | 5.90 | 5.06–6.89 | ||

| Town | 9,735 | 91.90 | 91.03–92.69 | 843 | 8.09 | 7.31–8.97 | 2,590 | 92.41 | 91.05–93.58 | 203 | 7.58 | 6.42–8.95 | ||

| Village or rural area | 3,618 | 92.38 | 91.17–93.45 | 326 | 7.61 | 6.55–8.83 | 1,957 | 89.38 | 86.70–91.57 | 212 | 10.61 | 8.43–13.30 | ||

| Smoking | 0.104 | 0.797 | ||||||||||||

| No | 36,460 | 92.71 | 92.08–93.29 | 2,861 | 7.28 | 6.70–7.92 | 20,071 | 93.34 | 92.05–94.44 | 1,294 | 6.65 | 5.56–7.95 | ||

| Yes | 4,944 | 91.55 | 89.70–93.10 | 413 | 8.44 | 6.90–10.30 | 2,767 | 93.49 | 91.80–94.86 | 170 | 6.50 | 5.14–8.20 | ||

| Compliance with physical distancing | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| No | 3,850 | 88.10 | 86.27–89.73 | 546 | 11.89 | 10.27–13.73 | 1,817 | 84.58 | 81.22–87.44 | 321 | 15.41 | 12.56–18.78 | ||

| Yes | 37,554 | 93.11 | 92.48–93.70 | 2,728 | 6.88 | 6.30–7.52 | 21,021 | 94.29 | 93.21–95.21 | 1,143 | 5.70 | 4.78–6.79 | ||

| Compliance with mask use | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| No | 2,801 | 86.88 | 85.53–88.13 | 387 | 13.11 | 11.87–14.46 | 1,203 | 87.34 | 82.07–91.23 | 134 | 12.65 | 8.77–17.93 | ||

| Yes | 38,603 | 93.06 | 92.40–93.68 | 2,887 | 6.93 | 6.32–7.60 | 21,635 | 93.75 | 92.70–94.66 | 1,330 | 6.24 | 5.34–7.30 | ||

| Food insecurity | 0.908 | 0.004 | ||||||||||||

| No | 12,237 | 92.61 | 91.50–93.60 | 965 | 7.38 | 6.40–8.49 | 5,701 | 91.85 | 89.71–93.58 | 444 | 8.14 | 6.42–10.29 | ||

| Yes | 29,167 | 92.57 | 91.97–93.13 | 2,309 | 7.42 | 6.87–8.03 | 17,137 | 93.83 | 92.63–94.85 | 1,020 | 6.16 | 5.15–7.37 | ||

| Economic insecurity | 0.007 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| No | 5,996 | 91.39 | 89.97–92.62 | 562 | 8.60 | 7.37–10.03 | 2,341 | 89.18 | 86.50–91.39 | 262 | 10.81 | 8.61–13.50 | ||

| Yes | 35,408 | 92.77 | 92.14–93.36 | 2,712 | 7.22 | 6.64–7.86 | 20,497 | 93.82 | 92.62–94.85 | 1,202 | 6.17 | 5.15–7.38 | ||

| Anxiety symptomatology | 0.032 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| No | 25,981 | 92.29 | 91.48–93.04 | 2,215 | 7.70 | 6.96–8.52 | 13,108 | 92.53 | 90.83–93.95 | 932 | 7.46 | 6.05–9.17 | ||

| Yes | 15,423 | 93.10 | 92.42–93.73 | 1,059 | 6.89 | 6.27–7.57 | 9,730 | 94.49 | 93.52–95.32 | 532 | 5.50 | 4.68–6.48 | ||

| Depressive symptomatology | 0.575 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| No | 23,408 | 92.51 | 91.76–93.20 | 1,895 | 7.48 | 6.80–8.24 | 11,389 | 92.47 | 90.92–93.78 | 838 | 7.52 | 6.22–9.08 | ||

| Yes | 17,996 | 92.68 | 91.93–93.37 | 1,379 | 7.31 | 6.63–8.07 | 11,449 | 94.25 | 93.12–95.20 | 626 | 5.74 | 4.80–6.87 | ||

| Comorbidities | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| No | 26,216 | 91.72 | 90.92–92.46 | 2,328 | 8.27 | 7.54–9.08 | 13,832 | 92.40 | 91.02–93.50 | 1,020 | 7.59 | 6.41–8.98 | ||

| Yes | 15,188 | 94.05 | 93.13–94.87 | 946 | 5.94 | 5.13–6.87 | 9,006 | 95.12 | 94.21–95.89 | 444 | 4.87 | 4.11–5.79 | ||

| Vaccinated | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| No | 19,559 | 86.91 | 85.81–87.94 | 2,752 | 13.08 | 12.06–14.19 | 12,127 | 89.71 | 87.94–91.26 | 1,213 | 10.28 | 8.74–12.06 | ||

| Yes | 21,845 | 97.72 | 97.30–98.08 | 522 | 2.27 | 1.92–2.70 | 10,711 | 97.59 | 97.15–97.96 | 251 | 2.40 | 2.04–2.85 | ||

| Had COVID-19 | 0.467 | 0.002 | ||||||||||||

| No | 26,834 | 92.49 | 91.81–93.13 | 2,115 | 7.50 | 6.86–8.19 | 12,593 | 92.61 | 90.85–94.05 | 845 | 7.38 | 5.95–9.15 | ||

| Yes | 14,570 | 92.74 | 91.88–93.51 | 1,159 | 7.25 | 6.48–8.12 | 10,245 | 94.24 | 93.29–95.08 | 619 | 5.75 | 4.92–6.71 | ||

95 %CI: 95 % Confidence Intervals.

Factors associated with parents’ non-intention to vaccinate their children and adolescents against COVID-19 in Colombia

In the adjusted regression model, we found that age groups between 35 and 44 years old (aPR = 0.77; 95 %CI: 0.66–0.90; p = 0.001) and 45 to 54 years old (aPR = 0.78; 95 %CI: 0.65–0.95; p = 0.012) were associated with a lower prevalence of non-intention to vaccinate children against COVID-19 compared to the age group between 18 and 24 years. Likewise, compliance with physical distancing (aPR = 0.55; 95 %CI: 0.49–0.61; p < 0.001), use of masks (aPR = 0.71; 95 %CI: 0.65–0.78; p < 0.001), economic insecurity (aPR = 0.72; 95 %CI: 0.65–0.89; p < 0.001), anxiety symptoms (aPR = 0.87; 95 %CI: 0.79–0.95; p = 0.003), was associated with a lower prevalence of non-intention to vaccinate children against COVID-19. Additionally, having one or more comorbidities (aPR = 0.83; 95 %CI: 0.75–0.91; p < 0.001) and being vaccinated against COVID-19 (aPR = 0.17; 95 %CI: 0.15–0.20; p < 0.001) were associated with a lower prevalence of non-intention to vaccinate children against COVID-19 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Factors associated with parents’ non-intention to vaccinate their children and adolescents against COVID-19 in Colombia and Peru.

| Characteristics |

Colombia |

Peru |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Parents’ non-intention to vaccinate their children and adolescents against COVID-19 |

Parents’ non-intention to vaccinate their children and adolescents against COVID-19 |

|||||||||||

| Crude |

Adjusted |

Crude |

Adjusted |

|||||||||

| cPR | 95 %CI | p-value | aPR | 95 %CI | p-value | cPR | 95 %CI | p-value | aPR | 95 %CI | p-value | |

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Male | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – |

| Female | 1.04 | 0.93–1.16 | 0.452 | 1.06 | 0.94–1.10 | 0.318 | 0.72 | 0.64–0.81 | <0.001 | 0.81 | 0.71–0.93 | 0.002 |

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||

| 18–24 | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – |

| 25–34 | 0.83 | 0.74–0.93 | 0.003 | 0.92 | 0.82–1.03 | 0.178 | 1.04 | 0.84–1.28 | 0.703 | 1.15 | 0.92–1.43 | 0.218 |

| 35–44 | 0.60 | 0.51–0.70 | <0.001 | 0.77 | 0.66–0.90 | 0.001 | 0.76 | 0.61–0.95 | 0.018 | 0.92 | 0.73–1.16 | 0.488 |

| 45–54 | 0.49 | 0.40–0.61 | <0.001 | 0.78 | 0.65–0.95 | 0.012 | 0.65 | 0.52–0.81 | <0.001 | 0.96 | 0.73–0.27 | 0.776 |

| Educational level | ||||||||||||

| University post-graduate degree completed/university completed/college/pre-university | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – | |||

| Secondary school completed/High school (or equivalent) completed | 1.22 | 1.14–1.32 | <0.001 | 0.95 | 0.87–1.02 | 0.165 | 1.15 | 1.01–1.31 | 0.033 | 0.94 | 0.83–1.05 | 0.258 |

| Primary school completed/Less than primary school/No formal schooling | 1.32 | 1.11–1.58 | 0.003 | 0.92 | 0.77–1.09 | 0.320 | 1.49 | 1.07–2.07 | 0.018 | 1.06 | 0.82–1.37 | 0.635 |

| Area of residence | ||||||||||||

| City | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – |

| Town | 1.15 | 1.02–1.30 | 0.028 | 1.09 | 1.00–1.10 | 0.060 | 1.28 | 1.10–1.50 | 0.002 | 1.16 | 1.00–1.35 | 0.048 |

| Village or rural área | 1.08 | 0.92–1.26 | 0.331 | 0.94 | 0.81–1.00 | 0.426 | 1.80 | 1.51–2.14 | <0.001 | 1.0.51 | 1.26–1.80 | <0.001 |

| Smoking | ||||||||||||

| No | Reference | – | – | Not included * | Reference | – | – | Not included * | ||||

| Yes | 1.16 | 0.97–1.38 | 0.095 | 0.98 | 0.82–1.16 | 0.794 | ||||||

| Compliance with physical distancing | ||||||||||||

| No | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – |

| Yes | 0.58 | 0.51–0.66 | <0.001 | 0.55 | 0.49–0.61 | <0.001 | 0.37 | 0.32–0.42 | <0.001 | 0.45 | 0.39–0.52 | <0.001 |

| Compliance with mask use | ||||||||||||

| No | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – |

| Yes | 0.53 | 0.48–0.58 | <0.001 | 0.71 | 0.65–0.78 | <0.001 | 0.49 | 0.38–0.64 | <0.001 | 0.71 | 0.56–0.90 | 0.005 |

| Food insecurity | ||||||||||||

| No | Reference | – | – | Not included * | Reference | – | – | Not included * | ||||

| Yes | 1.01 | 0.91–1.12 | 0.907 | 0.76 | 0.64–0.90 | 0.002 | ||||||

| Economic insecurity | ||||||||||||

| No | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – |

| Yes | 0.84 | 0.74–0.95 | 0.005 | 0.72 | 0.65–0.80 | <0.001 | 0.57 | 0.49–0.66 | <0.001 | 0.66 | 0.59–0.75 | <0.001 |

| Anxiety symptomatology | ||||||||||||

| No | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – |

| Yes | 0.89 | 0.81–0.99 | 0.028 | 0.87 | 0.79–0.95 | 0.003 | 0.74 | 0.64–0.84 | <0.001 | 0.82 | 0.70–0.97 | 0.020 |

| Depressive symptomatology | ||||||||||||

| No | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – |

| Yes | 0.98 | 0.90–1.06 | 0.570 | 1.00 | 0.91–0.10 | 0.949 | 0.76 | 0.70–0.84 | <0.001 | 0.92 | 0.82–1.03 | 0.162 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||||||||

| No | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – |

| Yes | 0.72 | 0.64–0.80 | <0.001 | 0.83 | 0.75–0.91 | <0.001 | 0.64 | 0.54–0.76 | <0.001 | 0.74 | 0.63–0.86 | <0.001 |

| Vaccinated | ||||||||||||

| No | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – |

| Yes | 0.17 | 0.15–0.20 | <0.001 | 0.17 | 0.15–0.20 | <0.001 | 0.23 | 0.20–0.28 | <0.001 | 0.24 | 0.20–0.28 | <0.001 |

| Had COVID-19 | ||||||||||||

| No | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – |

| Yes | 0.97 | 0.86–1.06 | 0.462 | 0.95 | 0.87–1.03 | 0.256 | 0.78 | 0.67–0.90 | 0.001 | 0.83 | 0.73–0.94 | 0.006 |

95 %CI: 95 % confidence intervals; cPR: Crude prevalence ratio; aPR: Adjusted prevalence ratio.

Not included due to not having a statistically significant association in the crude model.

Peru

Characteristics of the study sample in Peru

In the Peruvian sample, 52.81 % were female, 33.01 % were between 35 and 44 years old, 51.48 % had at least a full university post-graduate degree completed/university completed/college/pre-university, 75.98 % lived in a city, and 11.39 % reported having smoked. In addition, 90.39 % and 93.94 % had complied with physical distancing and the use of a mask, respectively. We found that 76.26 % reported having food insecurity, while 89.95 % reported having economic insecurity. Anxiety and depressive symptoms were reported in 42.31 % and 50.01 %, respectively, and 62.81 % of the participants did not report comorbidities, 53.71 % were not yet vaccinated against COVID-19, and 45.91 % had had COVID-19 at some point. The prevalence of parentś non-intention to vaccinate their children and adolescents against COVID-19 was 6.64 % (Table 1).

Prevalence of parents’ non-intention to vaccinate their children and adolescents against COVID-19 according to each region of Peru

In Peru, the regions with the highest prevalence of non-intention to vaccinate children against COVID-19 were Moquegua (13.73 %), Madre de Dios (13.65 %), and Puno (11.83 %). On the other hand, the regions with a lower prevalence of non-intention to vaccinate children against COVID-19 were Pasco (4.10 %), Lima (4.82 %), and Piura (5.03 %) (Fig. 2b).

Bivariate analysis according to parents’ non-intention to vaccinate their children and adolescents against COVID-19 in Peru

We found statistically significant differences between the independent variables and the intention of parents to vaccinate their children and adolescents against COVID-19, except for smoking (p = 0.797) (Table 2).

Factors associated with parents’ non-intention to vaccinate their children and adolescents against COVID-19 in Peru

In the adjusted regression model, we found female gender (aPR = 0.81; 0.71–0.93; p = 0.002) compared to male gender was associated with a lower prevalence of non-intention to vaccinate children against COVID-19. Likewise, compliance with physical distancing (aPR = 0.45; 95 %CI: 0.39–0.52; p < 0.001), use of masks (aPR = 0.71; 95 %CI: 0.65–0.90; p = 0.005), economic insecurity (aPR = 0.66; 95 %CI: 0.59–0.75; p < 0.001), anxiety symptoms (aPR = 0.82; 95 %CI: 0.70–0.97; p = 0.020) were associated with a lower prevalence of non-intention to vaccinate children against COVID-19. In addition, having one or more comorbidities (aRP = 0.74; 95 %CI: 0.63–0.86; p < 0.001), being vaccinated against COVID-19 (aPR = 0.24; 95 %CI: 0.20–0.28; p < 0.001) and having had COVID-19 (aPR = 0.83; 95 %CI: 0.73–0.94; p = 0.006) were associated with a lower prevalence of non-intention to vaccinate children against COVID-19. On the other hand, living in a town (aPR = 1.16; 95 %CI: 1.00–1.35; p = 0.048) and living in a village or rural area (aPR = 1.51; 95 %CI: 1.26–1.80; p < 0.001) compared to living in the city was associated with a higher prevalence of non-intention to vaccinate children against COVID-19 (Table 3).

Discussion

Our main results show that about 9 out of 10 parents in Colombia and Peru intend to vaccinate their children and adolescents against COVID-19. In Colombia, being between 35 and 54 years old, adherent to maintaining physical distance, using masks, having economic insecurity, having symptoms of anxiety and comorbidities, and being vaccinated were associated with a higher probability of vaccinating children against COVID-19. In Peru, being female, an adherent to maintaining social distancing, using a mask, having economic insecurity, having symptoms of anxiety and comorbidities, having been vaccinated, and having had COVID-19 was associated with a lower probability of not having the intention to vaccinate children. On the contrary, living in a town or rural area was associated with a greater intention not to vaccinate.

Our results of the intention to vaccinate children and adolescents are similar to those found in the evaluation carried out between May and June 2021 in LAC [13]. This are good news in terms of public health because the Ministries of Health of Peru and Colombia have already scheduled or started vaccination against COVID-19 with different vaccines in children and adolescents [28], [29]. This acceptance is expected to be reflected in the increase in population coverage of the vaccine to achieve the rate needed to obtain herd immunity. However, variations between the regions of the countries and in the case of Peru, according to the place of residence, require individualization of the vaccination programs based on the region.

As in other LAC countries, some factors associated with the socioeconomic and psychological consequences of the pandemic reduce the non-intention of vaccination[13]. Indeed, aspects such as stress[13], economic or food insecurity as a result of the economic crisis during the pandemic and especially during the first wave [30], possibly created a state of alert and the desire for such a situation not to be repeated, being vaccination seen as an opportunity to achieve this [13]. Along the same line, adherence to community mitigation measures such as the use of masks and social distancing may reflect a higher likelihood of complying with vaccination. Similarly, the feeling of vulnerability [26] and the desire to avoid this happening to their children may foster the positive view of vaccination and reduce the probability of non-intention to vaccinate their children [13].

While some factors coincide among the different countries, some studies have shown that some factors can be explained by social determinants and socioeconomic differences between countries [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24]. Although, to date, no study has compared these differences, there may be several explanations. In a previous study by our group evaluating food insecurity in LAC in the first stage of the pandemic, it was found that food insecurity was higher in Peru than in Colombia (83.9 % vs 76.8 %, respectively), which may explain the results of the present study [30]. Similarly, the impact of the pandemic was different in the two countries, with the number of deaths registered until November 17, 2021, being more than 200 thousand in Peru [31] and about 128 thousand in Colombia [32]. These differences might suggest that the fear of having had the infection and its consequences have led to the desire of this not happening to their children and an increase in the intention to vaccinate them. On the other hand, according to the document “Distinctive features of health systems in the world, 2017″ the Colombian health system is better developed than the Peruvian [33]. Indeed, in Peru, despite the improvements, structural problems and coverage of health services in areas such as rural areas had a great impact on health care during the pandemic and could explain our present results [34], [35].

There were great variations in the intention to vaccinate among the different regions of Peru. The regions with the least intention to vaccinate were Madre de Dios, Puno, and Moquegua. In contrast, the regions of Lima and Lambayeque had the highest intention to vaccinate children and adolescents against COVID-19. The Madre de Dios and Moquegua regions presented the lowest fatality during the pandemic, which may explain the lesser feeling of fear, commented previously compared to Lambayeque, for example, which is one of the departments with the highest fatality [31]. However, the complexity of the impact of the pandemic in each region is far from being fully understood, which could explain why, in the department of Puno, a region with low mortality, the intention to vaccinate is low. However, it is likely that some aspects such as self-medication [36], knowledge about the disease [37], and the reliability of the sites where Peruvians obtain information [38] on the pandemic or the variation in prevention practices among Peruvians [39], may explain the differences in intention to vaccinate children among the different regions of Peru.

In Colombia, the departments with the highest vaccination intention were Vaupés, San Andrés, Bolívar, Guainía, and Cundinamarca, being above 94 %. Several of these regions were significantly affected by COVID-19, especially in terms of concentration of cases per inhabitant. In departments such as San Andrés, there was deep state intervention in different aspects due to the initial level of involvement of COVID, which might influence the subsequent vaccination intention. Likewise, in the department of Bolívar, where the capital, Cartagena, is located, there were also a considerable number of cases and deaths, which may influence the intention of vaccination [40]. The vaccination program in Colombia is led by a mass media campaign [41], having the support of scientific societies, such as the Colombian Association of Infectious Diseases, which promotes information based on evidence to both health personnel and the community, and this could also contribute to the intention of vaccination [42].

Our study has some limitations. Since the respondents were users of a social network, information was only obtained from people with access to the internet and social networks, which could vary between the regions of the countries evaluated and the rural population. We do not have the non-response rate, which is relevant in the context of an online survey. The variables included in this analysis were pre-established in the survey, and there could be relevant variables not included in our analysis. The data were obtained by self-reporting and, therefore, an underreporting of information is possible. Finally, due to the design of the study, our results should only be interpreted in the context of associations since causality among the variables evaluated could not be established. However, this study presents the strength of analyzing a database with a large representative sample of social network users widely used in Colombia and Peru.

Conclusion

In conclusion, about 9 out of 10 parents in Colombia and Peru intend to vaccinate their children and adolescents against COVID-19. This intention was associated with some factors which are similar between the two countries, as well as other factors and variations among the different regions of each country. This means that despite good general acceptance of vaccination against COVID-19, the health authorities of each country must propose individualized strategies depending on the context if the vaccination campaigns in this population group are to achieve their objectives. This includes not only broadening the target groups of both unvaccinated and vaccinated but also achieving high coverage with an additional booster or complementary doses. Finally, scientific evidence must be communicated to the public, including aspects that may affect confidence in vaccines, such as the new variants of concern, including the Omicron variant, among other aspects.

Declaration of interests.

Vicente A. Benites-Zapata reports article publishing charges was provided by San Ignacio de Loyola University.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions: All authors made substantial contributions to the study's conception and design, analysis and interpretation.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the University of Maryland and Facebook, Inc for conducting and making the survey dataset available. We thank the Universidad Científica del Sur and Donna Pringle for English editing support. We acknowledge the Universidad San Ignacio de Loyola for paying the article processing charge.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvacx.2022.100198.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Reference

- 1.Robinson E., Jones A., Lesser I., Daly M. International estimates of intended uptake and refusal of COVID-19 vaccines: A rapid systematic review and meta-analysis of large nationally representative samples. Vaccine. 2021;39:2024–2034. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartsch Sarah M., O'Shea Kelly J., Wedlock Patrick T., Strych Ulrich, Ferguson Marie C., Bottazzi Maria Elena, et al. The Benefits of Vaccinating With the First Available COVID-19 Coronavirus Vaccine. Am J Prev Med. 2021;60(5):605–613. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2021.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharif N., Alzahrani K.J., Ahmed S.N., Dey S.K. Efficacy, Immunogenicity and Safety of COVID-19 Vaccines: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Immunol. 2021;12:4149. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.714170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Meng, Wu Ting, Zuo Zhihong, You Yaxian, Yang Xinyuan, Pan Liangyu, et al. Evaluation of current medical approaches for COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2021;11(1):45–52. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Musha, Yuan Yue, Zhou Yiguo, Deng Zhaomin, Zhao Jin, Feng Fengling, et al. Safety of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Infect Dis Poverty. 2021;10(1) doi: 10.1186/s40249-021-00878-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dembiński Łukasz, Vieira Martins Miguel, Huss Gottfried, Grossman Zachi, Barak Shimon, Magendie Christine, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination in Children and Adolescents—A Joint Statement of the European Academy of Paediatrics and the European Confederation for Primary Care Paediatricians. Front Pediatr. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.721257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eberhardt Christiane Sigrid, Siegrist Claire‐Anne, Kalaycı Ömer. Is there a role for childhood vaccination against COVID-19? Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2021;32(1):9–16. doi: 10.1111/pai.13401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.FDA Authorizes Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine for Emergency Use in Children 5 through 11 Years of Age | FDA https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-authorizes-pfizer-biontech-covid-19-vaccine-emergency-use-children-5-through-11-years-age (accessed December 7, 2021).

- 9.Walter Emmanuel B., Talaat Kawsar R., Sabharwal Charu, Gurtman Alejandra, Lockhart Stephen, Paulsen Grant C., et al. Evaluation of the BNT162b2 Covid-19 Vaccine in Children 5 to 11 Years of Age. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(1):35–46. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2116298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldman Ran D., Staubli Georg, Cotanda Cristina Parra, Brown Julie C., Hoeffe Julia, Seiler Michelle, et al. Factors associated with parents’ willingness to enroll their children in trials for COVID-19 vaccination. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2021;17(6):1607–1611. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1834325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skjefte Malia, Ngirbabul Michelle, Akeju Oluwasefunmi, Escudero Daniel, Hernandez-Diaz Sonia, Wyszynski Diego F., et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among pregnant women and mothers of young children: results of a survey in 16 countries. Eur J Epidemiol. 2021;36(2):197–211. doi: 10.1007/s10654-021-00728-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldman RD, McGregor S, Marneni SR, Katsuta T, Griffiths MA, Hall JE, et al. Willingness to Vaccinate Children against Influenza after the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic. J Pediatr 2021;228:87-93.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Urrunaga-Pastor Diego, Herrera-Añazco Percy, Uyen-Cateriano Angela, Toro-Huamanchumo Carlos J., Rodriguez-Morales Alfonso J., Hernandez Adrian V., et al. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Parents’ Non-Intention to Vaccinate Their Children and Adolescents against COVID-19 in Latin America and the Caribbean. Vaccines. 2021;9(11):1303. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9111303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodriguez-Morales A.J., Franco O.H. Public trust, misinformation and COVID-19 vaccination willingness in Latin America and the Caribbean: today’s key challenges. Lancet Reg Heal - Am. 2021;3 doi: 10.1016/j.lana.2021.100073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herrera-Añazco Percy, Uyen-Cateriano Ángela, Urrunaga-Pastor Diego, Bendezu-Quispe Guido, Toro-Huamanchumo Carlos J., RodrÍguez-Morales Alfonso J., et al. Prevalencia y factores asociados a la intención de vacunarse contra la COVID-19 en el Perú. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2021;38(3):381–390. doi: 10.17843/rpmesp.2021.383.7446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caycho-Rodríguez T., Carbajal-León C., Vivanco-Vidal A., Saroli-Araníbar D. Intention to vaccinate against COVID-19 in Peruvian older adults. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol. 2021;56:245–246. doi: 10.1016/j.regg.2021.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alvis-Guzman N, Alvis-Zakzuk J, Paz-Wilches J, Fernandez-Mercado JC, de la Hoz-Restrepo F. Willingness to receive the COVID-19 vaccine in the population aged 80 years and older in Colombia 2021. Vacunas 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vacun.2021.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Gobierno de Colombia. Encuesta Pulso Social. Resultados décima ronda (Periodo de referencia: abril de 2021) 2021.

- 19.Malik Amyn A., McFadden SarahAnn M., Elharake Jad, Omer Saad B. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the US. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;26:100495. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin C., Tu P., Beitsch L.M. Confidence and receptivity for covid-19 vaccines: A rapid systematic review. Vaccines. 2021;9:1–32. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9010016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi S.H., Jo Y.H., Jo K.J., Park S.E. Pediatric and Parents’ Attitudes Towards COVID-19 Vaccines and Intention to Vaccinate for Children. J Korean Med Sci. 2021;36:1–12. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aldakhil H., Albedah N., Alturaiki N., Alajlan R., Abusalih H. Vaccine hesitancy towards childhood immunizations as a predictor of mothers’ intention to vaccinate their children against COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia. J Infect Public Health. 2021;14:1497–1504. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2021.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Szilagyi P.G., Shah M.D., Delgado J.R., Thomas K., Vizueta N., Cui Y., et al. Parents’ intentions and perceptions about COVID-19 vaccination for their children: Results from a national survey. Pediatrics. 2021;148 doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-052335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Escobar-Díaz F., Bibiana Osorio-Merchán M., De la Hoz-Restrepo F. Motivos de no vacunación en menores de cinco años en cuatro ciudades colombianas. Rev Panam Salud Pública. 2017;41:1. doi: 10.26633/rpsp.2017.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mangla Sherry, Zohra Makkia Fatima Tuz, Pathak Ashok Kumar, Robinson Renee, Sultana Nargis, Koonisetty Kranthi Swaroop, et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Emerging Variants: Evidence from Six Countries. Behav Sci (Basel) 2021;11(11):148. doi: 10.3390/bs11110148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Urrunaga-Pastor Diego, Bendezu-Quispe Guido, Herrera-Añazco Percy, Uyen-Cateriano Angela, Toro-Huamanchumo Carlos J., Rodriguez-Morales Alfonso J., et al. Cross-sectional analysis of COVID-19 vaccine intention, perceptions and hesitancy across Latin America and the Caribbean. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2021;41:102059. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2021.102059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barkay N, Cobb C, Eilat R, Galili T, Haimovich D, LaRocca S, et al. Weights and Methodology Brief for the COVID-19 Symptom Survey by University of Maryland and Carnegie Mellon University, in Partnership with Facebook 2020.

- 28.Ministerio de Salud. Protocolo para la vacunación contra la COVID-19 para adolescentes de 12 a 17 años. 2021.

- 29.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social. Avanza la vacunación en niños de 3-11 años. Boletín de Prensa No 1136 de 2021 2021. https://www.minsalud.gov.co/Paginas/Avanza-la-vacunacion-en-ninos-de-3-11-anos.aspx (accessed December 7, 2021).

- 30.Benites-Zapata Vicente A., Urrunaga-Pastor Diego, Solorzano-Vargas Mayra L., Herrera-Añazco Percy, Uyen-Cateriano Angela, Bendezu-Quispe Guido, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with food insecurity in Latin America and the Caribbean during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Heliyon. 2021;7(10):e08091. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ministerio de Salud. Sala situacional COVID-19 Perú [Internet]. Lima: MINSA; 2021 [accessed December 8, 2021]. Available in: https://covid19.minsa.gob.pe.

- 32.Reportes y Tableros de Control. MINSALUD [Internet]; 2021 [accessed December 8, 2021]. Available in: https://covid19.minsalud.gov.co.

- 33.Giraldo Valencia J.C., Delgado L.C., Coronado Cortés O.G., Cuadros Ruíz J.G. Rasgos distintivos de los sistemas de salud en el mundo - ACHC. Hospitalaria. 2017;2017:4–59. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mezones-Holguín E., Amaya E., Bellido-Boza L., Mougenot B., Murillo J.P., Villegas-Ortega J., et al. Health insurance coverage: The peruvian case since the universal insurance act. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2019;36:196–206. doi: 10.17843/rpmesp.2019.362.3998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peralta-Vera F.G., Castillo-Céspedes E., Galup-Leyva M., Rucoba-Ames J., Herrera-Añazco P., Benites-Zapata V.A. Factors Associated with Home Remedy Use by Adults Who Do Not Attend Health Care Facilities: Evidence from Peruvian Population-based Survey, 2019. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2021;32:2110–2124. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2021.0185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Navarrete-Mejía P.J., Velasco-Guerrero J.C., Loro-Chero L. Automedicación en época de pandemia: Covid-19. Rev Del Cuerpo Médico Del HNAAA. 2021;13:350–355. doi: 10.35434/rcmhnaaa.2020.134.762. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iglesias-Osores S., Saavedra-Camacho J.L., Acosta-Quiroz J., Córdova-Rojas L.M., Rafael-Heredia A. Percepción y conocimiento sobre COVID-19: Una caracterización a través de encuestas. Rev Del Cuerpo Médico Del HNAAA. 2021;13:356–360. doi: 10.35434/rcmhnaaa.2020.134.763. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mujica-Rodríguez I.E., Toribio-Salazar L.M., Curioso W.H. Evaluación de la confiabilidad de la información sanitaria en español sobre la Covid-19 en Google. Rev Del Cuerpo Médico Del HNAAA. 2021;14:33–40. doi: 10.35434/rcmhnaaa.2021.14sup1.1155. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fernandez-Guzman Daniel, Soriano-Moreno David, Ccami-Bernal Fabricio, Rojas-Miliano Cristhian, Sangster-Carrasco Lucero, Hernández-Bustamante Enrique A., et al. Prácticas de prevención y control frente a la infección por Sars-Cov2 en la población peruana. Rev Del Cuerpo Médico Del HNAAA. 2021;14(Sup1):13–21. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Minsalud-INS. Casos positivos de COVID-19 en Colombia | Datos Abiertos Colombia. La Plataforma Datos Abiertos Del Gob Colomb 2020. https://www.datos.gov.co/Salud-y-Protecci-n-Social/Casos-positivos-de-COVID-19-en-Colombia/gt2j-8ykr/data (accessed December 8, 2021).

- 41.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social. Plan Nacional de Vacunación contra el COVID-19. Dep Nac Planeación Minist Hacienda y Crédito Público Inst Evaluación Tecnológica En Salud 2020:95.

- 42.Saavedra Trujillo CH. Consenso colombiano de atención, diagnóstico y manejo de la infección por SARS-COV-2/COVID 19 en establecimientos de atención de la salud. Recomendaciones basadas en consenso de expertos e informadas en la evidencia. Infectio 2020;24:1. https://doi.org/10.22354/in.v24i3.851.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.