Abstract

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a serious threat to human health lack of effective treatment. There is an urgent need for both real-time tracking and precise treatment of the SARS-CoV-2 infected cells to mitigate and ultimately prevent viral transmission. However, selective triggering and tracking of the therapeutic process in the infected cells remains challenging. Here, we reported a main protease (Mpro)-responsive, mitochondrial-targeting, and modular-peptide-conjugated probe (PSGMR) for selective imaging and inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 infected cells via enzyme-instructed self-assembly and aggregation-induced emission (AIE) effect. The amphiphilic PSGMR was constructed with tunable structure and responsive efficiency, and validated with recombinant proteins, cells transfected with Mpro plasmid or infected by SARS-CoV-2, and Mpro inhibitor. By rational construction of AIE luminogen (AIEgen) with modular peptides and Mpro, we verified that the cleavage of PSGMR yielded gradual aggregation with bright fluorescence and enhanced cytotoxicity to induce the mitochondrial interference of the infected cells. This strategy may have value for selective detection and treatment of the SARS-CoV-2-infected cells.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, main protease, peptide-conjugated AIEgen, mitochondrial targeting, virus theranostics

Graphical Abstract

A Mpro-responsive peptide-conjugated mitochondrial-targeting AIEgen PSGMR for selective imaging and inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 infected cells is presented. Combining with SARS-CoV-2 replication characteristics, EISA and AIE, PSGMR might be significant benefit to better understanding of viral progression and management of current epidemic situation. The rational construction, catalytic efficiency, tunable structural changes, and intracellular distribution of PSGMR are exploited with the infected cells and inhibitor.

INTRODUCTION

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and its variants continue to spread worldwide, causing millions of cumulative cases and deaths.1, 2 Despite the availability of accurate screening and reliable vaccines, there is still lack of effective therapies for this disease.3-6 Several antiviral therapies, targeting the transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2) and/or cell surface angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) are under study. Some of them have emergency use authorization or are in clinical trials to prevent infection of host cells via protease inhibitors, therapeutic antibodies, engineered aptamers, and cross-linking peptides.7-12 Upon infection with SARS-CoV-2, cells produce several key proteases through the coronavirus RNA genome for viral replication.13 Among them, main protease (Mpro, also known as 3CLpro) is an essential non-structural protein that can effectively cleave the viral precursor polyprotein at specific sites to form functional proteins. Mpro becomes an attractive biomarker and promising target for virus detection and inhibition.14-17 Monitoring Mpro activity has attracted broad interest due to its potential value in identifying infected cells and monitoring inhibitors, which lead to the development of green fluorescent protein (GFP)-derived FlipGFP reporters, fluorescence (or Förster) resonance energy transfer-based probes, and colorimetric sensing platforms.18-20 Beyond detection, systems that offer both selective imaging and inhibition of SARS-CoV-2-infected cells could improve the management of current epidemic situation and understanding of viral progression.

Enzyme-instructed self-assembly (EISA) has been a paradigm shift in cancer therapy, and can be leveraged separately and in combination with existing therapies.21-25 Indeed, the controlled formation and accumulation of supramolecular nanostructures can affect the behavior and fate of targeted cells. By jointly utilizing overexpressed proteases, responsive peptides, and self-assembling precursors, the tunable aggregates can be precisely constructed and selectively inhibit target cancer cells or even to the specific organelles without damaging normal cells.26-28 This similar strategy has been applied to combat inflammatory cells and kill bacteria.29, 30 On the other hand, in order to accurately monitor treatment by EISA, various contrast agents have been developed for real-time and long-term tracking of delivery process.31-36 In particular, fluorescent probes offer rapid signal, high sensitivity, and easy labeling can monitor the treatment process and enhance aggregate formation via hydrophobic aromatic cyclic hydrocarbon dyes.37-41 However, the fluorescence intensity of conventional fluorophores is often quenched at high concentrations because of the notorious aggregation-caused quenching (ACQ) effect.42 As an alternative, aggregation-induced emission (AIE) luminogens (AIEgens) with bright fluorescence, large Stokes shift, and superior photostability have been widely used for optical devices, luminescent sensors, and imaging systems.43 Notably, the fluorescent intensity of AIEgens can be regulated by the customized sequences of peptides, nucleic acids, and glycans via changes in molecular aggregation state without self-quenching.44 Especially, the modular-peptide-conjugated AIEgens show many advantages for cell-selective imaging, targeted gene delivery, and synergistic therapy.45-48 At least four typical principles can be used to activate AIEgen fluorescence via functional peptides – these all restrict intramolecular motion: (1) trapping AIEgens into a confinement groove of specific proteins with ligands;45 (2) delivering numerous AIEgens into a narrow space of organelles with targeted peptides;46 (3) cleaving the hydrophilic peptides from AIEgens with proteases to enhance hydrophobic aggregation;47 and (4) creating AIEgen assemblies with self-assembling peptides.37 Therefore, combining EISA and the AIE effect can be a feasible method to selectively image and kill cells of interest. To the best of our knowledge, no study has yet reported this approach for effective treatment of SARS-CoV-2-infected cells through rational construction of peptide-conjugated AIEgens.

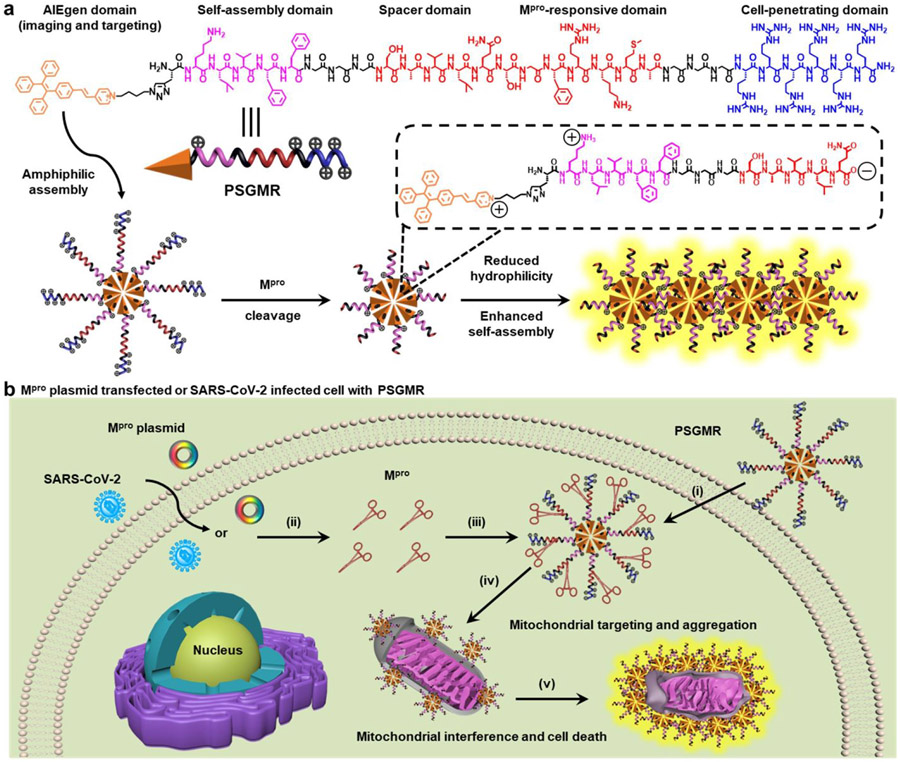

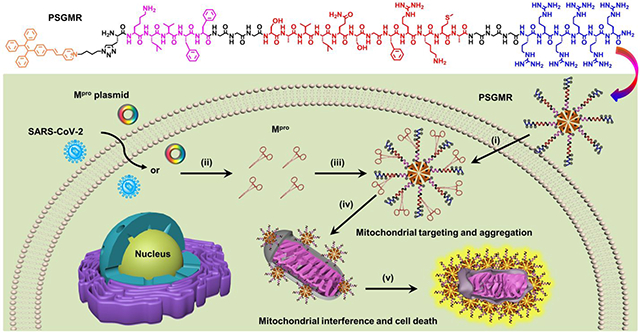

Herein, we report a Mpro-responsive, modular-peptide-conjugated, and mitochondrial-targeting AIEgen (PSGMR) for selective imaging and inhibition of the SARS-CoV-2-infected cells (Scheme 1). PSGMR consists of five segments: The first is an AIEgen (PyTPE, P for short in PSGMR). PyTPE as a typical AIEgen with pyridinium moiety has bright fluorescence, excellent biocompatibility, and good photostability for biomarker detection and mitochondrial-targeting imaging.49, 50 Second, the self-assembling peptide (KLVFF, S) is a β-sheet-forming peptide derived from β-amyloid (Aβ) protein.51, 52 KLVFF can spontaneously self-assemble into amyloid fibrils and kill cells when aggregated into insoluble fibrils through the intermolecular interactions in the absence of additional hydrophilic residues.53-55 Third, the spacer trimylglycine (GGG, G) is designed to enhance probe flexibility and reduce steric hindrance for Mpro-substrate interactions.56, 57 The fourth component is the Mpro-responsive peptide (SAVLQ/SGFRKMA, M), which can be cleaved by Mpro after LQ sequence.58, 59 The fifth is a positive charged hexamolyarginine (RRRRRR, R) that increases both the solubility and cell-penetrating ability of PSGMR, and shields self-assembly capability of PyTPE and KLVFF.60-63 These five components were covalently coupled through a Fmoc-based solid-phase peptide synthesis and a copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne click reaction. In the absence of Mpro, PSGMR as an amphiphilic molecule with highly water-soluble and electrostatic repulsion can form loose nanoparticles with limited fluorescence in an aqueous solution (Scheme 1a). It shows the positive charged hexamolyarginine residues on the surface and the hydrophobic core of PyTPE. After being cleaved by Mpro, the hydrophilic hexamolyarginine is separated from PSG, and the self-assembling peptides with C-terminal carboxyl are exposed to the surface of smaller nanoparticles. Finally, the decreasing hydrophilicity and increasing self-assembly of KLVFF as well as electrostatic attraction led to PSG gradual aggregation with strong fluorescence (Scheme S1). Thus, after incubation with PSGMR, the cells transfected with Mpro plasmid or infected by SARS-CoV-2 to produce Mpro can induce the PSG aggregation inside the mitochondria, and selectively inhibit the growth of the cells to prevent virus replication (Scheme 1b). This theranostic probe will provide a controllable avenue for selective imaging and inhibition of the SARS-CoV-2-infected cells.

Scheme 1. Structure and function of PSGMR.

(a) Molecular structure and schematic illustration of PSGMR with main protease (Mpro). (b) PSGMR is used for Mpro-responsive mitochondrial imaging and selective inhibition of Mpro plasmid transfected or SARS-CoV-2 infected cells. i) PSGMR effectively crosses the cell membrane; ii) Mpro plasmid transfected or SARS-CoV-2-infected cells can produce Mpro; iii) Mpro binds and cleaves the substrate of PSGMR; iv) After being cleaved by Mpro, PSG fragments decrease in size and targeted deliver to the mitochondria; v) The PSG aggregation induces mitochondrial interference and selectively inhibits the growth of SARS-CoV-2-infected cells with strong fluorescence. The potentially charged amino acids are labeled with the charge symbol after Mpro cleavage.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Design, synthesis and characterization of PSGMR and its derivatives.

PSGMR and its derivatives were designed based on the requirements of EISA and AIE effect via an Mpro trigger. Importanly, SAVLQ/SGFRKMA as a substrate for Mpro cleavage can regulate the ratio of hydrophobicity and hydrophilicity and surface potential. This sequence has an area of high enzyme-digestion efficiency located in the center. After the Mpro cleavage, it was divided into the hydrophobic SAVLQ and hydrophilic SGFRKMA. For the proper arrangement of these segments, the hydrophobic PyTPE and KLVFF were located at the N-terminal while the hydrophilic hexamolyarginine part was placed at the C-terminal. Trimylglycine was added at both ends of the Mpro substrate to leave enough space for enzyme and substrate binding. All peptide domains were covalently linked via Fmoc-based solid-phase peptide synthesis. Propargylglycine (Pra) was used as a linker to couple with azide-functionalized PyTPE under the mild conditions via a copper-catalyzed click reaction. Two control probes without spacer (PSMR) and self-assembling peptide (PMR) were synthesized to verify Mpro accessibility and self-assembly of the probes.

All the probes were synthesized according to previous reports with minor improvement (Schemes S2-S5, Table S1), characterized by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) to confirm their purity (at least 95%) and chemical structures (Figures S1-S9). We also tested the high-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) to verify the accuracy of multiple charge peaks of PSMR in the ESI-MS (Figures S3 and S5). Taking PSGMR for example, Figure S7 showed a strong peak at 768.2742 attributed to the [M+5H]5+ ion of PSGMR (calculated, 767.8326); a strong peak at 640.3345 attributed to the [M+6H]6+ ion of PSGMR (calculated, 640.0285); a strong peak at 549.0886, attributed to the [M+7H]7+ ion of PSGMR (calculated, 548.7398); and a strong peak at 480.9327 attributed to the [M+8H]8+ ion of PSGMR (calculated, 480.2733). The mass data of PSMR and PMR also matched well with the calculated data. These data indicated that PSGMR, PSMR, and PMR were synthesized successfully.

Responsiveness to enzyme in solutions.

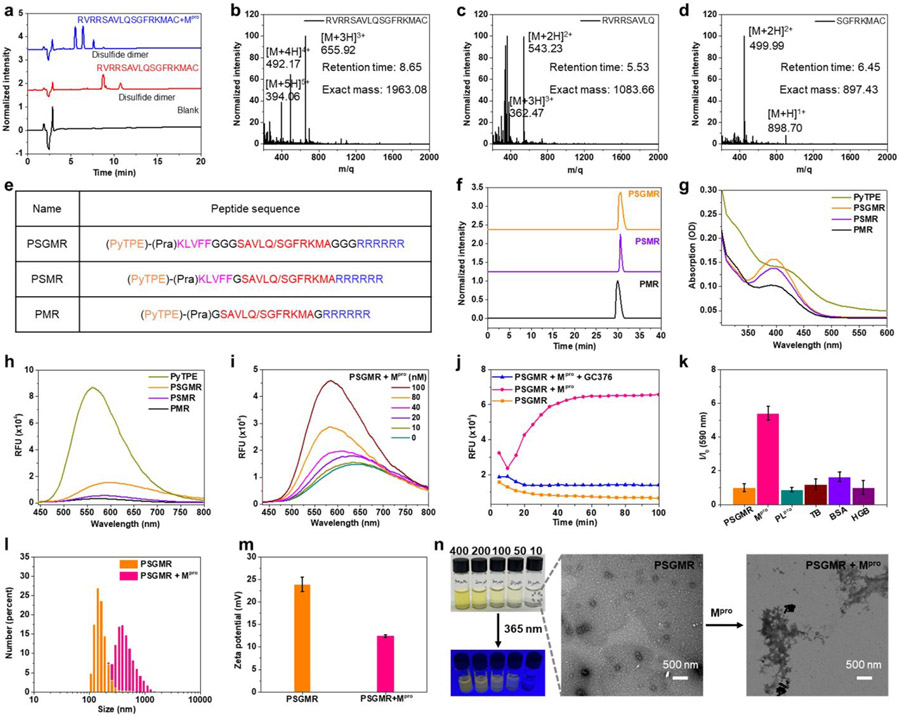

We first evaluated whether the peptides and probes can be specifically cleaved by recombinant Mpro as predicted. We found that the specially customized peptides CGAVLQDDD and AVLQFFVLKC were not cleaved by Mpro, but RVRRSAVLQSGFRKMAC and CGKLVFFGTSAVLQSGFRGDDD were cleaved by Mpro between Q and S (Figures 1a-1d, and S10-S12). The docking scores of Mpro with different peptides also showed the enhanced binding abilities among them (Figure S13). HPLC and ESI-MS analysis also confirmed that PSGMR and PMR but not PSMR can be cleaved by Mpro between Q and S after incubation for 1 h at 37 °C in 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) (Figures 1e-1f, and S14-S17). With 24 h of incubation, PSGMR was fully cleaved by Mpro while PSMR remained intact. These data suggest that the hydrophobic peptide or PyTPE prevent Mpro from binding to the substrate. While the trimylglycine spacer can improve the digestion efficiency of Mpro for this substrate (SAVLQ/SGFRKMA).

Figure 1. Characteristics of PSGMR and its derivatives.

(a) high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and (b-d) Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) results of the designed peptide incubation with Mpro. (e) Molecular composition, (f) HPLC, (g) absorption, and (h) fluorescence spectra of PSGMR, PSMR and PMR showed the good purity and solubility enhancement with the decreased fluorescence intensity. (i) Fluorescence spectra and (j) kinetics of PSGMR with different concentration of Mpro and 10 μM GC376 at 590 nm showed the fluorescence increase because of Mpro. (k) Probe specificity of PSGMR with 200 nM different proteins including Mpro, papain-like protease (PLpro), thrombin (TB), bovine serum albumin (BSA), and hemoglobin (HGB). (l) Hydrodynamic sizes, (m) zeta potential values, (n) photographs and transmission electron microscope (TEM) images of PSGMR with Mpro. In panel j, vials contained 10, 50, 100, 200, and 400 μM PSGMR solutions under UV light (365 nm, 16 W). 10 μM of PSGMR, PSMR, PMR, and PyTPE were dissolved in Tris-HCl buffer with 1% DMSO with λex = 405 nm.

We then explored the spectral properties of PyTPE, PSGMR, PSMR, and PMR. They showed absorption spectral profiles at 350-450 nm in the Tris-HCl buffer with 1% DMSO at room temperature (Figure 1g); 405 nm was chosen as optimal excitation wavelength. The fluorescence spectral profiles of PyTPE, PSGMR, PSMR, and PMR were 500–750 nm (Figure 1h). The fluorescence intensity of PSGMR, PSMR, and PMR decreased after being modified with hydrophilic peptides. The critical micelle concentrations (CMC) values of PSGMR and PSGMR after incubation with 200 nM Mpro decreased from 8.95 μM to 2.06 μM (Figure S18). The fluorescence changes of PSGMR and PMR incubation were monitored upon incubation with Mpro in different media: 10 μM offered the significant fluorescence enhancement and was used for subsequent experiments (Figures S19-S21). Particularly, the fluorescence intensity of PMR and PSMR after incubation with Mpro was much weaker than that of PSGMR because the lack of self-assembling peptide and spacer.

To validate the enzyme digestion efficiency, PSGMR was incubated with different concentrations of Mpro. The fluorescence intensity of PSGMR gradually enhanced with increasing Mpro concentration (Figure 1i). When PSGMR was incubated with more Mpro (from 100 nM to 400 nM), the fluorescence intensity of PSGMR enhanced but not as much as the PyTPE at the same concentration (Figure S22). This is because of some hydrophilic residues (K, S, and Q) still linked with PyTPE. Subsequent kinetic studies were performed by incubating PSGMR with 200 nM Mpro and 10 μM Mpro inhibitor GC376 over time.18, 19 In the absence of GC376, the fluorescence intensity of PSGMR at 590 nm obviously increased with time and plateaued within 40 min with Mpro incubation (Figure 1j). No increase in the fluorescence was detected in the presence of the GC376, thus showing that the fluorescence increase was due to Mpro-mediated peptide cleavage. PSGMR was also treated under identical conditions with several commercial proteins to investigate probe specificity: papain-like protease, thrombin, bovine serum albumin (BSA), and hemoglobin. The fluorescence intensity of PSGMR was clearly enhanced selectively with Mpro (Figure 1k). The fluorescence intensity of PyTPE was only slightly elevated when BSA was added (Figure S23). BSA has a low isoelectric point, and thus it or other negatively charged proteins may cause PyTPE and PSGMR to aggregate due to the positively charged pyridinium and hexamolyarginine.

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) tests, transmission electron microscopy (TEM), circular dichroism (CD) spectra of PSGMR were performed to determine the change of particle size, surface potential distribution, and secondary structure after incubation with Mpro. The average hydrodynamic size of PSGMR increased from 142 nm to 396 nm (Figure 1l), and the mean zeta potential value decreased from 23.97 mV to 12.46 mV (Figure 1m), suggesting nanoparticle aggregation and a reduction of arginine on the nanoparticle surface. The morphology change of PSGMR before and after incubation with Mpro was confirmed by TEM (Figure 1n). The β-sheet structure of PSGMR but not Tris-HCI buffer and PMR was observed after incubation with Mpro or at high concentrations (Figures S24-S27). These data proved that PSGMR is responsive to Mpro leading to aggregation state changes and fluorescence enhancement.

Mitochondrial imaging and imaging comparison of HeLa cells with PyTPE, PSGMR and PMR.

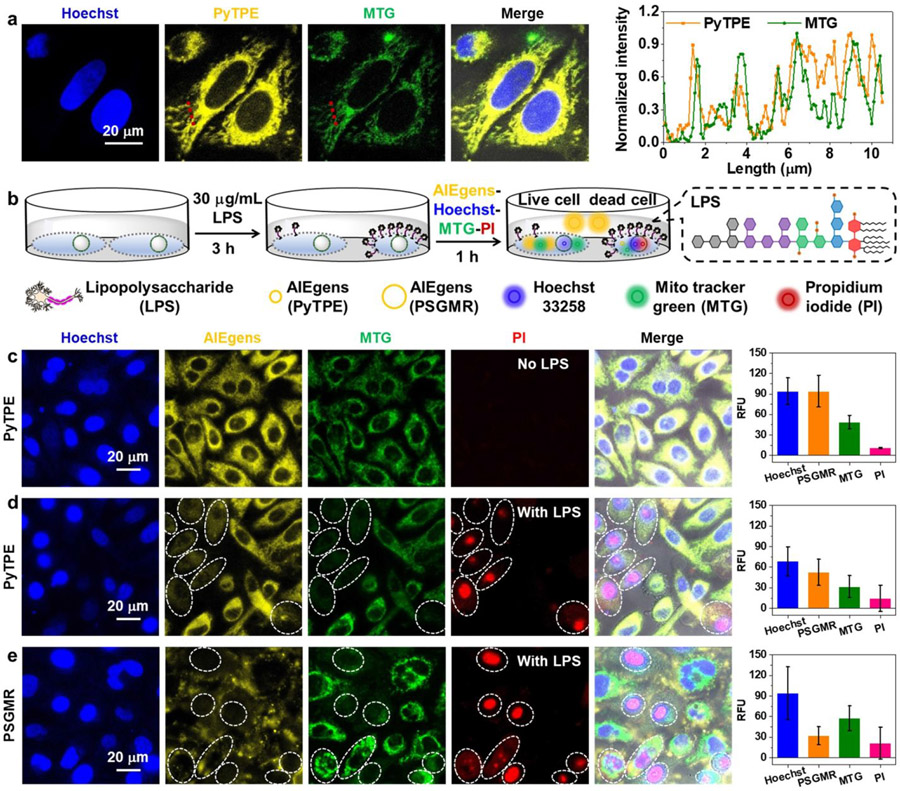

The mitochondrial targeting capability of PyTPE was tested via HeLa cells co-localization imaging. HeLa cells were co-cultured with commercial dyes Mito tracker green (MTG), Hoechst 33258 (nucleus staining of all cells), and propidium iodide (PI, nucleus staining of dead cells) for confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) observation. First, the photobleaching results showed that PyTPE, PSGMR, and PMR had better photostability than MTG (Figure S28). HeLa cells were incubated with different concentrations of PyTPE for 3 h, and 1 μM MTG and 5 μM Hoechst 33258 for 1 h (Figure S29). The yellow fluorescence of PyTPE overlapped well with the green fluorescence of MTG with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 81.71 % (5 μM) to 85.09 % (10 μM). High-resolution cell imaging and fluorescence intensities of PyTPE and MTG showed exact overlap on each other along the red line, thus confirming that PyTPE can target to mitochondria with high specificity (Figure 2a). Prior work showed that positively charged pyridinium units and hydrophobic alkyl chain of PyTPE can target mitochondria based on the hydrophobic effect and electrostatic interactions.49, 50, 64, 65 Versus the fluorescence of PyTPE with PSGMR and PMR at 5 μM concentration, PSGMR and PMR displayed weak fluorescence and poor overlap with MTG because of the hydrophilic polypeptides (Figure S30). The strong yellow fluorescence of 10 μM PSGMR was seen inside the HeLa cells due to nonspecific aggregation. This phenomenon is more clear in the Z-stack imaging for PyTPE and PSGMR (Figure S31).

Figure 2. Mitochondrial imaging of HeLa cells with PyTPE and PSGMR.

(a) Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) images and the normalized fluorescence intensities based on the red dotted lines of HeLa cells with Hoechst 33258, PyTPE and a commercial dye Mito tracker green (MTG) for co-localization imaging. (b) The experimental scheme of HeLa cells after incubation with LPS for 3 h, and PyTPE, PSGMR, Hoechst 33258, and PI. The enlarged portion shows the chemical construction of LPS. CLSM images and average fluorescence intensities of HeLa cells with (c) PyTPE, Hoechst 33258, and PI, (d) LPS, PyTPE, Hoechst 33258, and PI, (e) LPS, PSGMR, Hoechst 33258, and PI. The MTG is activated for mitochondria in the green channel. The PI is activated in the red channel when cells are dead.

To study the crowding effects that might happen during apoptosis already induce the fluorescence, HeLa cells were incubated with 30 μg/mL lipopolysaccharide (LPS, known as endotoxin) for 3 h. We then added PyTPE (or PSGMR), Hoechst 33258, and PI for 1 h (Figure 2b). The yellow and green fluorescence had good overlap but no red fluorescence was seen in the HeLa cells without LPS incubation, suggesting the cells were alive (Figure 2c). After pretreatment with LPS, some of HeLa cells were dead, and showed red fluorescence for both PyTPE and PSGMR incubation (Figures 2d and 2e). The yellow and green fluorescence in dead cells was weaker than in living cells, especially for the PSGMR which had obvious extracellular yellow fluorescence. We found that a stronger red fluorescence of dead cells implied a lower yellow and green fluorescence. The membrane potential decreased after cell death and prevented the macromolecule PSGMR from interacting with the cells. Similarly, small molecule dyes PyTPE and MTG could not enter the cells because of the negatively charged LPS and its toxicity.

Imaging and inhibition of Mpro plasmid-transfected HEK 293T cells with PSGMR and Mpro reporter.

To image Mpro in living cells, HEK 293T cells were transfected with an Mpro plasmid, influenza virus protein (PR8) plasmid, and Mpro-related FlipGFP reporter plasmid to produce proteins of interest.18, 19 (Figure 3a). The Mpro-related FlipGFP reporter plasmid was co-transfected into Mpro plasmid or PR8 plasmid-transfected cells to assess Mpro expression in plasmid transfected HEK 293T cells. The green fluorescence of the FlipGFP reporter only activates after cleavage by Mpro. The transfected cells were further incubated with PSGMR and PI for CLSM cell imaing. First, to examine the cytotoxicity and optimized concentration of probes for cell imaging, different concentrations between 1 and 40 μM of PyTPE, SGMR, PSGMR, and PMR were incubated with HEK 293T cells for 48 h under standard cell culture conditions (Figure S32). PSGMR showed negligible toxicity to HEK 293T cells with almost 100% cell viability at low concentrations (1 to 10 μM). While high concentration of PyTPE (> 5 μM) and PSGMR (> 40 μM) can cause significant cytotoxicity. Compared with the cell viability of Mpro plasmid transfected HEK 293T cells, over 50% cells were dead with 10 mM PSGMR incubation unlike than 5 mM PSGMR. According to the CLSM images of cells for 3 h incubation, blue fluorescence of Hoechst 33258 was observed in the nucleus, and yellow fluorescence of PSGMR appeared at higher concentrations (≥ 5 μM), leading to strong background signals (Figure S33). Most of HEK 293T cells with a high concentration (20 μM) of PSGMR had red fluorescence from PI, indicating that high concentrations of PSGMR could cause significant cytotoxicity due to the mitochondrial-targeting damage by PyTPE. Therefore, to avoid nonspecific aggregation and non-specific cleavage by proteolytic enzymes in the complex cellular microenvironment, 5 μM of probe was used for Mpro imaging for 30 min incubation; 10 μM probes for cell inhibition experiments.

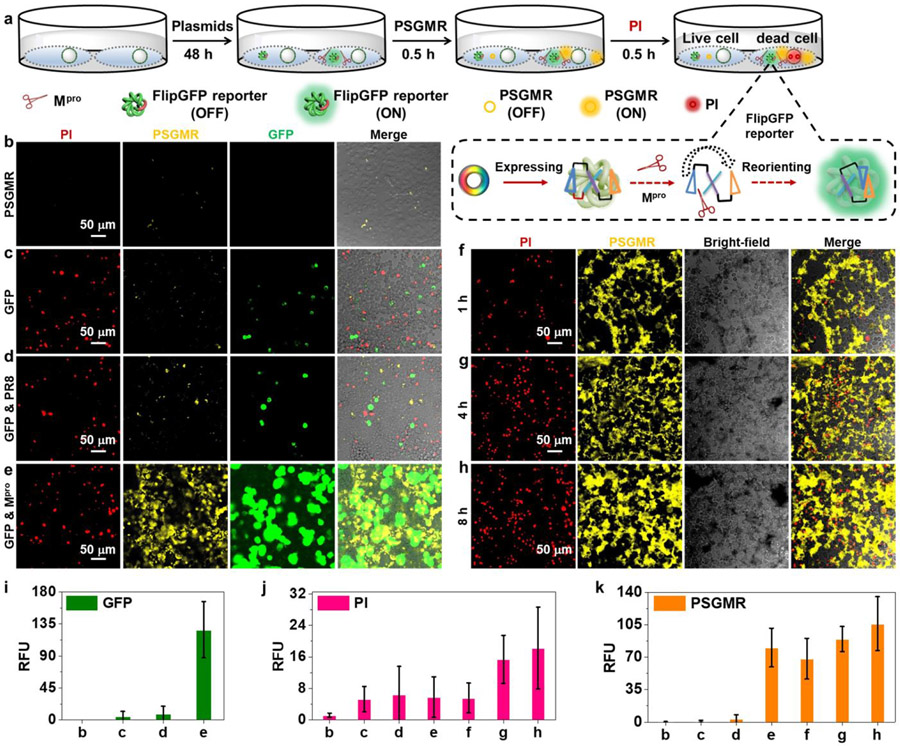

Figure 3. Validation of PSGMR via plasmids and reporter.

(a) The experimental scheme of different plasmids transfected HEK 293T cells after incubation with PI, and PSGMR. The enlarged portion shows the imaging mechanism of FlipGFP. CLSM images of the HEK 293T cells with (b) PSGMR, (c) Mpro-related FlipGFP reporter plasmid and PSGMR, (d) Mpro-related FlipGFP reporter plasmid, PR8 plasmid and PSGMR, (e) Mpro-related FlipGFP reporter plasmid, Mpro plasmid and PSGMR, and Mpro plasmid and PSGMR for (f) 1h, (g) 4h, and (h) 8h. Average fluorescence intensities of (i) GFP, (j) PI and (k) PSGMR in each panel. The FlipGFP and PSGMR are activated in the green and yellow channel when cells are transfected with the Mpro plasmid. The PI is activated in the red channel when cells are dead.

The untransfected HEK 293T cells showed almost no yellow fluorescence just for 1 h incubation with 5 μM PSGMR (Figure 3b). Only weak green and yellow fluorescence was observed in the FlipGFP reporter plasmid-transfected and PR8 plasmid & FlipGFP reporter plasmid co-transfected HEK 293T cells (Figures 3c and 3d). Notably, the transfection agent was toxic to cells and led to the red fluorescence.66, 67 Strong green, yellow and red fluorescence was observed in the cells that were co-transfected with Mpro plasmid & FlipGFP reporter plasmid (Figures 3e and 3j). Only co-transfection of Mpro and FlipGFP plasmids produced strong fluorescence signal of PSGMR, FlipGFP, and PI, thus indicating that Mpro and FlipGFP reporter were functional in these cells, and more cells were dead because of PSGMR. The flow cytometric results showed higher fluorescence intensities of FlipGFP and PI in the Mpro & FlipGFP plasmids co-transfected HEK 293T cells than the control experiments (Figure S34). We further investigated the FlipGFP reporter and PSGMR independent for Mpro sensing. Both approaches could be used for intracellular Mpro imaging (Figure S35). While the corresponding plasmid needed to be transfected into cells and expressed to FlipGFP reporter, which would take a long-time incubation (24 to 48 h) and complicated operation with limited yield.18 PSGMR not only can be easy to enter into the cells for Mpro imaging with good photostability, but it also killed the targeted cells (Figure S36). We clearly observe the aggregation of PSGMR with increasing fluorescence inside the cells. The yellow fluorescence was first displayed from the cytoplasm to near the nucleus, and then to near the cell membrane (Figures 37).

To validate the cell inhibitory effect of probes, 10 μM PSGMR was incubated with Mpro plasmid transfected cells for 1 h, 4 h, and 8 h (Figures 3f-3h). In particular, compared with the fluorescence of HeLa cells incubation with LPS and PSGMR, there was strong yellow fluorescence inside the Mpro plasmid-transfected HEK 293T cells but not in the culture medium. The red and yellow fluorescence intensities were markedly enhanced with the prolong incubation time (Figures 3j and 3k). We further confirmed that PSGMR overlapped well with MTG with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 85.26 % in the Mpro plasmid transfected HEK 293T cell (Figure S38). All these data proved that PSGMR can be used for selective mitochondrial imaging and inhibition of Mpro plasmid transfected cells.

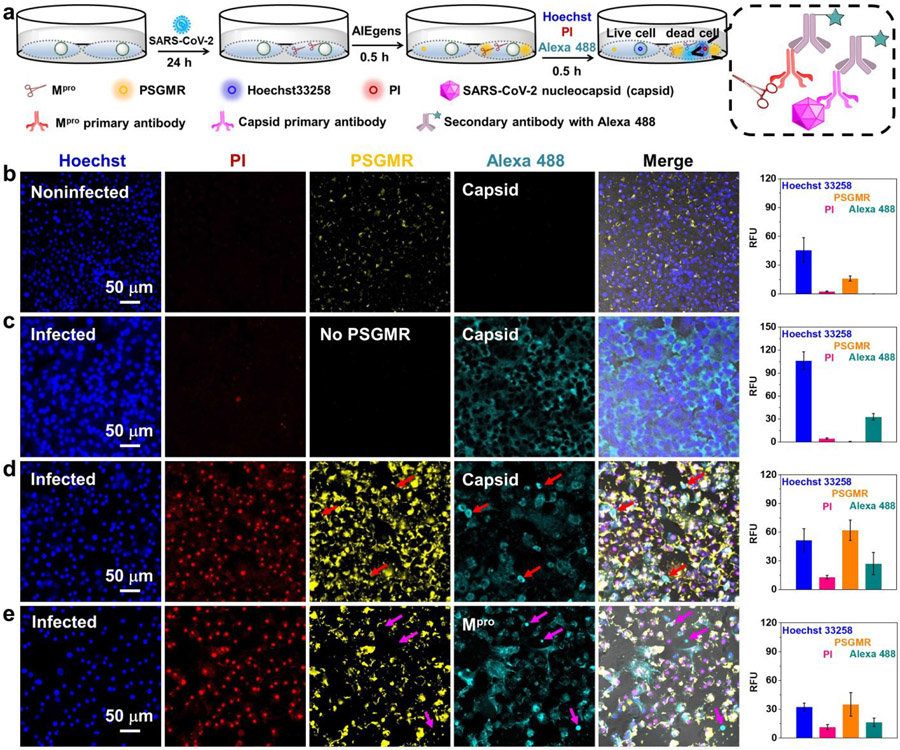

Imaging and inhibition of SARS-CoV-2-infected TMPRSS2-Vero cells with PSGMR and GC376.

After validating that PSGMR could selectively image and induce cytotoxicity in Mpro plasmid transfected HEK 293T cells, we then examined whether PSGMR could similarly image and kill SARS-CoV-2-infected cells. Thus, TMPRSS2-Vero cells were infected with SARS-CoV-2 (USA-WA1/2020) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.02 for 24 h before adding the PSGMR, Hoechst 33258, and PI. These cells were further labeled by staining viral proteins using fluorescent antibodies after cells were fixed including anti-SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid (Capsid) primary antibody and anti-SARS-CoV-2 Mpro primary antibody; AlexaFluor 488-labeled secondary antibody (Alexa 488) was used for both (Figure 4a). At 24 h post-infection, these probes were separately incubated with the noninfected and infected TMPRSS2-Vero cells for cell imaging. Cyan fluorescence of Alexa488 (either Capsid or Mpro) was observed in infected cells but not in uninfected cells, thus confirming that these cells were infected by SARS-CoV-2 and produced Mpro (Figures 4b and 4c). This result has been also confirmed with Western blot analysis in our previous work.19 In addition, strong yellow and red fluorescence was displayed only in infected cells treated with PSGMR rather than the uninfected cells with PSGMR or infected cells without PSGMR, thus showing that PSGMR can selectively kill SARS-CoV-2-infected cells (Figures 4d and 4e). The Pearson correlation coefficient of co-localization between PSGMR and Alexa 488 for Capsid or Mpro increased from 33.56 % to 61.57 % (Figure S39). Alexa 488-labeled secondary antibody for Mpro can bind to Mpro which is mainly in the cytoplasm. PSGMR can targeted to mitochondria and be cleaved by Mpro but not bind to Mpro. This leads to a low Pearson correlation coefficient of colocalization between PSGMR and Alexa 488. Upon increasing PSGMR concentration to 10 μM, the yellow and red fluorescence of the infected cells was significantly enhanced (Figure S40). When infected cells with 10 μM PMR, the yellow and red fluorescence intensities were weaker than that of PSGMR because of the absence of self-assembling peptide (Figure S41).

Figure 4. Selective imaging and inhibition of SARS-CoV-2-infected TMPRSS2-Vero cells with PSGMR.

(a) The experimental scheme of SARS-CoV-2 infected TMPRSS2-Vero cells incubation with PSGMR, anti-SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid (Capsid) primary antibody, anti-SARS-CoV-2 Mpro primary antibody, and AlexaFluor 488-labeled secondary antibody (Alexa 488). The enlarged portion shows the imaging mechanism of Alexa 488. CLSM images and average fluorescence intensities of (b) noninfected cells with PSGMR, (c) infected cells with capsid primary antibody/Alexa 488, (d) infected cells with capsid primary antibody/Alexa 488 and PSGMR, and (e) infected cells with Mpro primary antibody/Alexa 488 and PSGMR. The PI is activated in the red channel when cells are dead. The PSGMR and Alexa 488 are respectively activated in the yellow and cyan channel when cells are infected by SARS-CoV-2. The red and pink arrows show clear fluorescence only from Alexa 488, which is caused because PSGMR represented the protease activity, and the Alexa 488-labeled Capsid or Mpro antibody showed the protein location.

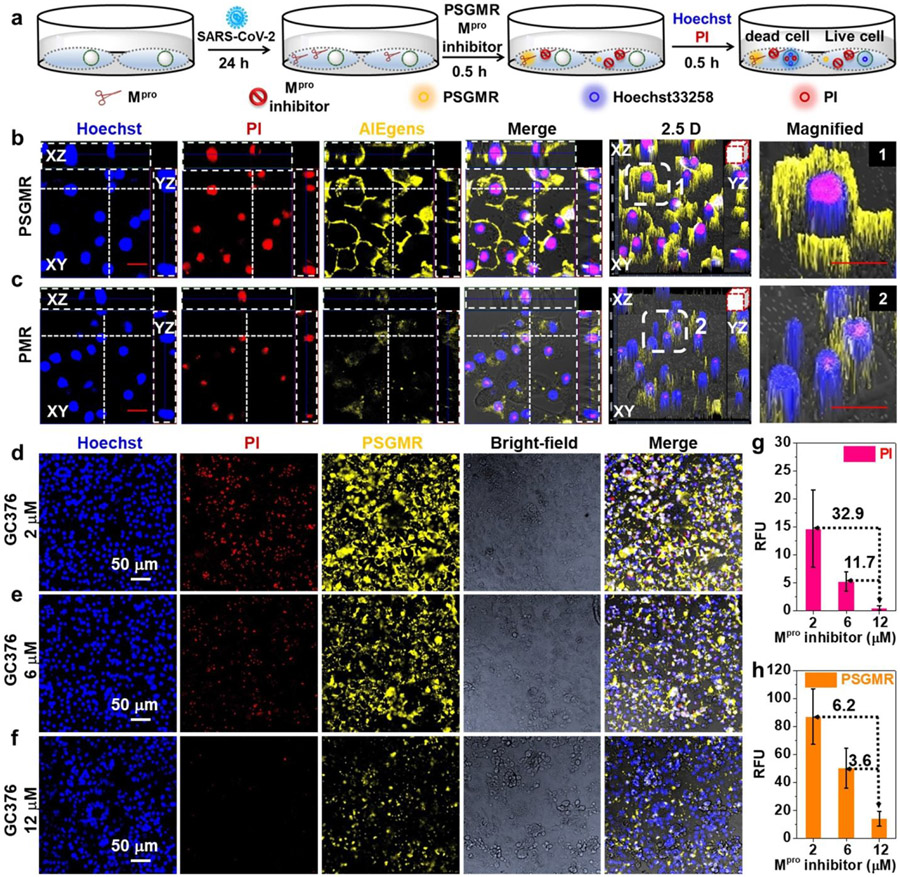

Further exploration of the intracellular distribution of probes in infected cells can help study the mechanism of action of these probes in inducing cell death (Figure 5a). As can be seen in Figure S42, the blue and red fluorescence overlapped well in the nucleus, and the yellow fluorescence of PSGMR was close to the cell membrane. During cell apoptosis, the decreased mitochondrial membrane potential could result in the diffusion of AIEgens from intracellular mitochondria to cytosol and extracellular medium due to the concentration gradient.49. 68 Importantly, the cyan fluorescence of Alexa 488 for Capsid was mainly located in the cell membrane and nucleus (Movies S1 and S2). While the cyan fluorescence of Alexa488 for Mpro was displayed in cell membrane and cytoplasm (Movies S3 and S4). This result clearly revealed the different locations of each protein in the infected cells. Moreover, compared with the differences between PSGMR and PMR in the noninfected and infected cells, the noninfected cells with PSGMR had weak red and yellow fluorescence with normal cell morphology (Figure S43). While the infected cells with PSGMR showed bright red and yellow fluorescence with obvious cell morphologic dilatation. The red and yellow fluorescence as well as cell morphology change of infected cells with PMR was less than the infected cells with PSGMR (Figures 5b and 5c). The average red and yellow fluorescence intensities of infected cells with PSGMR were 600% and 569% higher than the infected cells with PMR (Figures S43 and S44). These results confirmed that PSGMR was superior to PMR at selectively imaging and killing the SARS-CoV-2-infected TMPRSS2-Vero cells.

Figure 5. Imaging and inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 infected TMPRSS2-Vero cells with PSGMR and Mpro inhibitor.

(a) The experimental scheme of SARS-CoV-2 infected TMPRSS2-Vero cells with PSGMR and Mpro inhibitor. CLSM images of SARS-CoV-2 infected cells with (b) 10 μM PSGMR, (c) 10 μM PMR, 10 μM PSGMR with (d) 2 μM GC376, (e) 6 μM GC376, (f) 12 μM GC376. Mean fluorescence intensity of (g) PI and (h) PSGMR in infected cells incubation with 10 μM PSGMR and different concentrations of GC376. The number on the dotted line represents the fold-enhanced of fluorescence intensity versus the 12 μM Mpro inhibitor. In b and c, the transverse and vertical dotted line denotes the XZ and YZ plane cutting line of Z-stack images. The white boxes in the 2.5 D images are magnified. Red scale bar = 20 μm.

We then evaluated the inhibitory effect of infected cells with PSGMR and GC376. After 24 h post-infection, 10 μM PSGMR and different concentrations (2 μM, 6 μM, and 12 μM) of GC376 were incubated with the infected cells. Both red and yellow fluorescence markedly decreased with increasing concentrations of GC376 (Figures 5d-5f). Their average red and yellow fluorescence intensities decreased from 32.9 to 11.7 times and 6.2 to 3.6 times, respectively (Figures 5g and 5h). These data suggested that PSGMR can measure Mpro inhibition, and the cytotoxicity of PSGMR can be regulated by GC376. PSGMR and GC376 could be a combination therapy to prevent virus replication and track the treatment process.

CONCLUSIONS

Mpro is a vital protease only expressed in the infected cells for coronavirus replication. Mpro related substrate is applied to accurately detect the SARS-CoV-2 and quickly screen protease inhibitors to stop the epidemic. Take advantage of this particular property of Mpro and its substrate, we anticipate to design a series of Mpro-responsive probes to selective image and even kill the SARS-CoV-2-infected cells as well as achieve precision treatment through the long-term fluorescence change. The key issue is to construct an efficient and controllable integrated probe for diagnosis and treatment of the SARS-CoV-2-infected cells rather than the normal cells.

In summary, this work exploited the potential advantages of the EISA and AIE effect for selective detection and treatment of the SARS-CoV-2-infected cells. When combined with SARS-CoV-2 replication characteristics, a Mpro-responsive and modular-peptide-conjugated mitochondrial-targeting AIEgen PSGMR offered selective imaging and inhibition of the Mpro plasmid transfected HEK 293T cells and SARS-CoV-2-infected TMPRSS2-Vero cells. We utilized the mitochondrial-targeting function of the PyTPE to realize both mitochondrial selective delivery and long-term tracking. Versus control probes without spacers (PSMR) and self-assembling peptides (PMR), PSGMR can be more effectively cleaved by Mpro and form aggregates in the mitochondria of targeted cells with bright yellow fluorescence. Importantly, the formation process and therapeutic effect of aggregation were controlled by the rational composition of the modular-peptides, and visualized by the fluorescence change. We verified the theranostic property of PSGMR and PMR with Mpro-related FlipGFP reporter, PI, Alexa 488 staining of SARS-CoV-2 Capsid and Mpro, and Mpro inhibitor GC376. Under the combined influence of AIEgens and self-assembling peptides, 10 μM PSGMR fragments had significant toxicity on cells but only in the presence of Mpro. This strategy for protease-responsive organelle-targeting, modular-peptide-conjugated probes could lead to effective theranostic agents against SARS-CoV-2 and other emerging diseases. In addition, using AIEgens that absorb or emit light in the NIR window with multiple-responsive peptides can achieve deeper tissue optical imaging with higher signal-to-background ratios and better spatial resolution as well as accurate targeted delivery for precise diagnosis and treatment.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Chemistry methods and characterization.

The synthesis protocols and details are provided in the supplementary information.

Enzymatic assay with PSGMR, PSMR, and PMR.

The stock solution of PyTPE, PSGMR, PSMR, and PMR in 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH = 8.0) was diluted with Mpro assay buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) with 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, and 5 % glycerol) to make 5 and 10 μM working solutions. Recombinant Mpro was added into the working solution and then diluted to a total of 100 μl or 200 μl with deionized water. The reaction mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h for UV-Vis absorption and photoluminescence (PL) measurement. The solution was excited at 405 nm, and the emission was collected from 430 nm to 800 nm.

Determination of critical micelle concentration (CMC) of PSGMR and PSGMR after incubation with Mpro.

PSGMR solutions with or without pretreatment with 200 nM Mpro for 1 h were tested. The fluorescence intensity of PyTPE was analyzed as a function of the PSGMR concentration (Ex = 405 nm, Em = 590 nm). When extrapolating the intensity of PSGMR concentration region, the CMC values are determined as crossing points.

Cell culture and plasmid transfection.

HEK 293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal calf serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin streptomycin (PS, 10000 IU penicillin and 1000 μg/mL streptomycin, multicell) in a cell culture plates at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. For plasmid transfection, cells were treated with 100 μL to 1000 μL poly-L-lysine for 20 min before being seeded with HEK 293T cells. After 24 h incubation, Opti-MEM, plasmids (1 μg/μl to 3 μg/μl), and TransIT-LT (Mirus) were successively mixed and incubated at room temperature for 15 min before being added to cells dropwise according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Incubation living cells with probes.

For confocal laser scanning microscopy imaging, HEK 293T cells or the plasmid transfected HEK 293T cells were seeded into cell culture dishes at a density of 2.0 × 105 in growth medium (DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 200 mL). After overnight incubation, the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) three times. A solution of the indicated probe in medium or PBS was then added, and the cells were incubated in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C for further use. Hoechst 33258, PI, and AlexaFluor 488 were subsequently added for probe incubation. The supernatant was then discarded, and the cells were washed gently twice with PBS and fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at room temperature for 20 min prior to optical imaging.

Viral infection.

SARS-CoV-2 isolate WA1 (USA-WA1/2020, BEI NR-52281) was passaged once through primary human bronchial epithelial cells differentiated at air-liquid interface to select against Furin site mutations. Virus was then expanded by one passage through TMPRSS2-Vero cells. Supernatants were clarified and stored at −80 °C, and titers were determined by fluorescent assay on TMPRSS2-Vero cells. TMPRSS2-Vero cells were infected with a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.02 FFU per cell 24 h before incubation with probes. The SARS-CoV-2 noninfected and infected TMPRSS2-Vero cells were washed with Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) to remove FBS-containing media, then incubated with 5 or 10 μM probes for 30 min and fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 30 min. Cells were then stained using the nucleocapsid antibody or SARS-CoV-2 Mpro antibody and 5 μM Hoechst 33258. All work with SARS-CoV-2 was conducted in Biosafety Level-3 conditions at the University of California San Diego.

Immunofluorescence.

Fixed cells were washed with PBS and then with PBS including 1% BSA and 0.1% TritonX-100. Cells were incubated with primary antibody against SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein (1:2000, GeneTex, GTX135357) or Mpro (1:100, Cell Signaling Technology #51661) in PBS including 1% BSA and 0.1% TritonX-100 overnight at 4 °C. Cells were washed and incubated with Alexa 488 goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in PBS including 1% BSA for 1 h at room temperature followed by 3x PBS washes.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy.

The fluorescence signals of cells were detected using a Zeiss LSM880 confocal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss), equipped with a 63/1.42 numerical aperture oil-immersion objective lens. A 405-nm laser was chosen for the excitation of Hoechst 33258, the emission was collected at 420–460 nm. A 405 nm laser was chosen for the excitation of AIEgens and the emission was collected at 550–620 nm. A 488 nm laser was chosen for the excitation of GFP, the emission was collected at 500–530 nm. A 488 nm laser was chosen for the excitation of PI and the emission was collected at 595–650 nm. A 488 nm laser was chosen for the excitation of AlexaFluor 488, the emission was collected at 500–550 nm. All fluorescence images were analyzed with Zeiss Image software (Zeiss).

Cytotoxicity assay.

The cytotoxic potential of PyTPE, SGMR, PSGMR, and PMR were assessed using the HEK 293T cells for 48 h incubation in quadruplicate in a 96-well plate. The fluorescence of Resazurin solution at 690 nm using an excitation wavelength of 560 nm was recorded by a Synergy H1 microplate reader (BioTek) with standard operation procedures.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Nicholas S. Heaton for SARS-CoV-2 Mpro plasmid, Mpro-related FlipGFP reporter plasmid, and influenza virus protein (A/PR8/1834 NP) plasmid. The authors thank internal funding from the UC Office of the President (R00RG2515) and the National Institutes of Health (R01 DE031114, R21 AI157957, and R21 AG065776-01S1) for financial support. This work was supported in part by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program under Grant No. DGE-1650112. This research was supported by NIH grant (K08 AI130381) and Career Award for Medical Scientists from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund to AFC. The following reagent was deposited by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and obtained through BEI Resources, NIAID, NIH: SARS-Related Coronavirus 2, Isolate USA-WA1/2020, NR-52281.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at Supplementary Schemes S1 – S5, Table S1, and Figures S1 – S44: Molecular design, imaging mechanism and Mpro peptide sequence. Peptide sequences used in this study. Synthesis and characterization of PSGMR, PSMR, and PMR. Synthetic route, ESI-MS, HR-MS, and HPLC results of PSGMR, PSMR, and PMR. Time-dependent fluorescence spectra of PSGMR, PSMR, and PMR incubation with Mpro. CMC, TEM images, and hydrodynamic sizes results of different concentrations of PSGMR and PMR incubation with Mpro. CLSM images, Z-stack images, Pearson correlation coefficient of co-localization, and flow cytometric results of HeLa cells, plasmid-transfected HEK 293T cells, TMPRSS2-Vero cells, and SARS-CoV-2-infected TMPRSS2-Vero cells incubated with PyTPE, PSGMR, PMR, Hoechst 33258, Alexa 488, and PI. (PDF)

Supplementary Movies S1 – S4: SARS-CoV-2 infected TMPRSS2-Vero cells incubated with PSGMR, Hoechst 33258, PI, and Alexa 488 for nucleocapsid (Turn around X-axis). (AVI)

SARS-CoV-2 infected TMPRSS2-Vero cells incubated with PSGMR, Hoechst 33258, PI, and Alexa 488 for nucleocapsid (Z-axis scanning). (AVI)

SARS-CoV-2 infected TMPRSS2-Vero cells incubated with PSGMR, Hoechst 33258, PI, and Alexa 488 for Mpro (Turn around X-axis). (AVI)

SARS-CoV-2 infected TMPRSS2-Vero cells incubated with PSGMR, Hoechst 33258, PI, and Alexa 488 for Mpro (Z-axis scanning). (AVI)

The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- (1).Lu R; Zhao X; Li J; Niu P; Yang B; Wu H; Wang W; Song H; Huang B; Zhu N; Bi Y; Ma X; Zhan F; Wang L; Hu T; Zhou H; Hu Z; Zhou W; Zhao L; Chen J; Meng Y; Wang J; Lin Y; Yuan J; Xie Z; Ma J; Liu WJ; Wang D; Xu W; Holmes EC; Gao GF; Wu G; Chen W; Shi W; Tan W Genomic Characterisation and Epidemiology of 2019 Novel Coronavirus: Implications for Virus Origins and Receptor Binding. The Lancet 2020, 395 (10224), 565–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Cai Y; Zhang J; Xiao T; Lavine CL; Rawson S; Peng H; Zhu H; Anand K; Tong P; Gautam A; Lu S; Sterling SM; Walsh RM Jr; Rits-Volloch S; Lu J; Wesemann DR; Yang W; Seaman MS; Chen B Structural Basis for Enhanced Infectivity and Immune Evasion of SARS-CoV-2 Variants. Science 2021, 373 (6555), 642–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Kevadiya BD; Machhi J; Herskovitz J; Oleynikov MD; Blomberg WR; Bajwa N; Soni D; Das S; Hasan M; Patel M; Senan AM; Gorantla S; McMillan J; Edagwa B; Eisenberg R; Gurumurthy CB; Reid SPM; Punyadeera C; Chang L; Gendelman HE Diagnostics for SARS-CoV-2 Infections. Nat. Mater 2021, 20 (5), 593–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Shin MD; Shukla S; Chung YH; Beiss V; Chan SK; Ortega-Rivera OA; Wirth DM; Chen A; Sack M; Pokorski JK; Steinmetz NF COVID-19 Vaccine Development and a Potential Nanomaterial Path Forward. Nat. Nanotechnol 2020, 15 (8), 646–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Iwasaki A; Omer SB Why and How Vaccines Work. Cell 2020, 183 (2), 290–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Chauhan G; Madou MJ; Kalra S; Chopra V; Ghosh D; Martinez-Chapa SO Nanotechnology for COVID-19: Therapeutics and Vaccine Research. ACS. Nano 2020, 14 (7), 7760–7782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Ai X; Wang D; Honko A; Duan Y; Gavrish I; Fang RH; Griffiths A; Gao W; Zhang L Surface Glycan Modification of Cellular Nanosponges to Promote SARS-CoV-2 Inhibition. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2021, 143 (42), 17615–17621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Sun M; Liu S; Wei X; Wan S; Huang M; Song T; Lu Y; Weng X; Lin Z; Chen H; Song Y; Yang C Aptamer Blocking Strategy Inhibits SARS-CoV-2 Virus Infection. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2021, 60 (18), 10266–10272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Hoffmann M; Kleine-Weber H; Schroeder S; Kruger N; Herrler T; Erichsen S; Schiergens TS; Herrler G; Wu NH; Nitsche A; Muller MA; Drosten C; Pohlmann S SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell 2020, 181 (2), 271–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Avanzato VA; Matson MJ; Seifert SN; Pryce R; Williamson BN; Anzick SL; Barbian K; Judson SD; Fischer ER; Martens C; Bowden TA; de Wit E; Riedo FX; Munster VJ Case Study: Prolonged Infectious SARS-CoV-2 Shedding from an Asymptomatic Immunocompromised Individual with Cancer. Cell 2020, 183 (7), 1901–1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Fedry J; Hurdiss DL; Wang C; Li W; Obal G; Drulyte I; Du W; Howes SC; Kuppeveld F. J. M. v.; Förster F; Bosch B-J Structural Insights into The Cross-Neutralization of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 by The Human Monoclonal Antibody 47D11. Sci. Adv 2021, 7 (23), eabf5632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Zhao H; To KKW; Lam H; Zhou X; Chan JF; Peng Z; Lee ACY; Cai J; Chan WM; Ip JD; Chan CC; Yeung ML; Zhang AJ; Chu AWH; Jiang S; Yuen KY Cross-Linking Peptide and Repurposed Drugs Inhibit both Entry Pathways of SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Commun 2021, 12 (1), 1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Meyer B; Chiaravalli J; Gellenoncourt S; Brownridge P; Bryne DP; Daly LA; Grauslys A; Walter M; Agou F; Chakrabarti LA; Craik CS; Eyers CE; Eyers PA; Gambin Y; Jones AR; Sierecki E; Verdin E; Vignuzzi M; Emmott E Characterising Proteolysis during SARS-CoV-2 Infection Identifies Viral Cleavage Sites and Cellular Targets with Therapeutic Potential. Nat. Commun 2021, 12, 5553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Arafet K; Serrano-Aparicio N; Lodola A; Mulholland AJ; Gonzalez FV; Swiderek K; Moliner V Mechanism of Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 M(pro) by N3 Peptidyl Michael Acceptor Explained by QM/MM Simulations and Design of New Derivatives with Tunable Chemical Reactivity. Chem. Sci 2020, 12 (4), 1433–1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Zhang L; Lin D; Sun X; Curth U; Drosten C; Sauerhering L; Becker S; Rox K; Hilgenfeld R Crystal Structure of SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease Provides a Basis for Design of Improved α-Ketoamide Inhibitors. Science 2020, 368 (6489), 409–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Ansari N; Rizzi V; Carloni P; Parrinello M Water-Triggered, Irreversible Conformational Change of SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease on Passing from the Solid State to Aqueous Solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2021, 143 (33), 12930–12934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Iketani S; Forouhar F; Liu H; Hong SJ; Lin FY; Nair MS; Zask A; Huang Y; Xing L; Stockwell BR; Chavez A; Ho DD Lead Compounds for The Development of SARS-CoV-2 3CL Protease Inhibitors. Nat. Commun 2021, 12, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Froggatt HM; Heaton BE; Heaton NS Development of a Fluorescence-Based, High-Throughput SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro Reporter Assay. J. Virol 2020, 94 (22), e01265–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Cheng Y; Borum RM; Clark AE; Jin Z; Moore C; Fajtova P; O'Donoghue AJ; Carlin AF; Jokerst JV A Dual-Color Fluorescent Probe Allows Simultaneous Imaging of Main and Papain-Like Proteases of SARS-CoV-2-lnfected Cells for Accurate Detection and Rapid Inhibitor Screening. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2022, 61 (9), e202113617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Jin Z; Mantri Y; Retout M; Cheng Y; Zhou J; Jorns A; Fajtova P; Yim W; Moore C; Xu M; Creyer MN; Borum RM; Zhou J; Wu Z; He T; Penny WF; O'Donoghue AJ; Jokerst JV A Charge-Switchable Zwitterionic Peptide for Rapid Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2022, 61 (9), e202112995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Zhou J; Xu B Enzyme-Instructed Self-Assembly: A Multistep Process for Potential Cancer Therapy. Bioconjug. Chem 2015, 26 (6), 987–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Feng Z; Wang H; Chen X; Xu B Self-Assembling Ability Determines The Activity of Enzyme-Instructed Self-Assembly for Inhibiting Cancer Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139 (43), 15377–15384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Wang H; Feng Z; Xu B Instructed Assembly as Context-Dependent Signaling for The Death and Morphogenesis of Cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58 (17), 5567–5571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).He H; Tan W; Guo J; Yi M; Shy AN; Xu B Enzymatic Noncovalent Synthesis. Chem. Rev 2020, 120 (18), 9994–10078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Feng Z; Zhang T; Wang H; Xu B Supramolecular Catalysis and Dynamic Assemblies for Medicine. Chem. Soc. Rev 2017, 46 (21), 6470–6479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Yang ZM; Xu KM; Guo ZF; Guo ZH; Xu B Intracellular Enzymatic Formation of Nanofibers Results in Hydrogelation and Regulated Cell Death. Adv. Mater 2007, 19 (20), 3152–3156. [Google Scholar]

- (27).Feng Z; Wang H; Wang S; Zhang Q; Zhang X; Rodal AA; Xu B Enzymatic Assemblies Disrupt The Membrane and Target Endoplasmic Reticulum for Selective Cancer Cell Death. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140 (30), 9566–9573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Kumar S; Henning-Knechtel A; Magzoub M; Hamilton AD Peptidomimetic-Based Multidomain Targeting Offers Critical Evaluation of Abeta Structure and Toxic Function. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140 (21), 6562–6574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Yang Z; Liang G; Guo Z; Guo Z; Xu B Intracellular Hydrogelation of Small Molecules Inhibits Bacterial Growth. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2007, 46 (43), 8216–8219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Cheng Y; Dai J; Sun C; Liu R; Zhai T; Lou X; Xia F An Intracellular H2O2 - Responsive AIEgen for The Peroxidase-Mediated Selective Imaging and Inhibition of Inflammatory Cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2018, 57 (12), 3123–3127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Gao Y; Shi J; Yuan D; Xu B Imaging Enzyme-Triggered Self-Assembly of Small Molecules inside Live Cells. Nat. Commun 2012, 3, 1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).He H; Wang J; Wang H; Zhou N; Yang D; Green DR; Xu B Enzymatic Cleavage of Branched Peptides for Targeting Mitochondria. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140 (4), 1215–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Yan R; Hu Y; Liu F; Wei S; Fang D; Shuhendler AJ; Liu H; Chen HY; Ye D Activatable NIR Fluorescence/MRI Bimodal Probes for in Vivo Imaging by Enzyme-Mediated Fluorogenic Reaction and Self-Assembly. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141 (26), 10331–10341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Zhang XH; Cheng DB; Ji L; An HW; Wang D; Yang ZX; Chen H; Qiao ZY; Wang H Photothermal-Promoted Morphology Transformation in Vivo Monitored by Photoacoustic Imaging. Nano. Lett 2020, 20 (2), 1286–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Wang Y; Weng J; Wen X; Hu Y; Ye D Recent Advances in Stimuli-Responsive in Situ Self-Assembly of Small Molecule Probes for in Vivo Imaging of Enzymatic Activity. Biomater. Sci 2021, 9 (2), 406–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).He H; Guo J; Xu J; Wang J; Liu S; Xu B Dynamic Continuum of Nanoscale Peptide Assemblies Facilitates Endocytosis and Endosomal Escape. Nano. Lett 2021, 21 (9), 4078–4085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Han A; Wang H; Kwok RT; Ji S; Li J; Kong D; Tang BZ; Liu B; Yang Z; Ding D Peptide-Induced AIEgen Self-Assembly: A New Strategy to Realize Highly Sensitive Fluorescent Light-Up Probes. Anal. Chem 2016, 88(7), 3872–3878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Wu D; Sedgwick AC; Gunnlaugsson T; Akkaya EU; Yoon J; James TD Fluorescent Chemosensors: The Past, Present and Future. Chem. Soc. Rev 2017, 46 (23), 7105–7123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Zhao Y; Zhang X; Li Z; Huo S; Zhang K; Gao J; Wang H; Liang XJ Spatiotemporally Controllable Peptide-Based Nanoassembly in Single Living Cells for a Biological Self-Portrait. Adv. Mater 2017, 29 (32), 1601128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Pascal S; David S; Andraud C; Maury O Near-Infrared Dyes for Two-Photon Absorption in The Short-Wavelength Infrared: Strategies towards Optical Power Limiting. Chem. Soc. Rev 2021, 50 (11), 6613–6658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Li J; Fang Y; Zhang Y; Wang H; Yang Z; Ding D Supramolecular Self-Assembly-Facilitated Aggregation of Tumor-Specific Transmembrane Receptors for Signaling Activation and Converting Immunologically Cold to Hot Tumors. Adv. Mater 2021, 33(16), e2008518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Kwok RT; Leung CW; Lam JW; Tang BZ Biosensing by Luminogens with Aggregation-Induced Emission Characteristics. Chem. Soc. Rev 2015, 44 (13), 4228–4238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Mei J; Leung NL; Kwok RT; Lam JW; Tang BZ Aggregation-Induced Emission: Together We Shine, United We Soar! Chem. Rev 2015, 115 (21), 11718–11940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Xia F; Wu J; Wu X; Hu Q; Dai J; Lou X Modular Design of Peptide- or DNA-Modified AIEgen Probes for Biosensing Applications. Acc. Chem. Res 2019, 52 (11), 3064–3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Shi H; Liu J; Geng J; Tang BZ; Liu B Specific Detection of Integrin ανβ3 by Light-Up Bioprobe with Aggregation-Induced Emission Characteristics. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134 (23), 9569–9572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Cheng Y; Sun C; Liu R; Yang J; Dai J; Zhai T; Lou X; Xia F A Multifunctional Peptide-Conjugated AIEgen for Efficient and Sequential Targeted Gene Delivery into The Nucleus. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58 (15), 5049–5053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Yuan Y; Zhang CJ; Gao M; Zhang R; Tang BZ; Liu B Specific Light-Up Bioprobe with Aggregation-Induced Emission and Activatable Photoactivity for The Targeted and Image-Guided Photodynamic Ablation of Cancer Cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2015, 54 (6), 1780–1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Yang J; Dai J; Wang Q; Cheng Y; Guo J; Zhao Z; Hong Y; Lou X; Xia F Tumor-Triggered Disassembly of a Multiple-Agent-Therapy Probe for Efficient Cellular Internalization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2020, 59 (46), 20405–20410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Situ B; Chen S; Zhao E; Leung CWT; Chen Y; Hong Y; Lam JWY; Wen Z; Liu W; Zhang W; Zheng L; Tang BZ Real-Time Imaging of Cell Behaviors in Living Organisms by a Mitochondria-Targeting AIE Fluorogen. Adv. Fund. Mater 2016, 26 (39), 7132–7138. [Google Scholar]

- (50).Zheng X; Wang D; Xu W; Cao S; Peng Q; Tang BZ Charge Control of Fluorescent Probes to Selectively Target The Cell Membrane or Mitochondria: Theoretical Prediction and Experimental Validation. Mater. Horiz 2019, 6 (10), 2016–2023. [Google Scholar]

- (51).Lowe TL; Strzelec A; Kiessling LL; Murphy RM Structure-Function Relationships for Inhibitors of β-Amyloid Toxicity Containing The Recognition Sequence KLVFF. Biochemistry. 2001, 40 (26), 7882–7889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Cheng DB; Zhang XH; Gao YJ; Ji L; Hou D; Wang Z; Xu W; Qiao ZY; Wang H Endogenous Reactive Oxygen Species-Triggered Morphology Transformation for Enhanced Cooperative Interaction with Mitochondria. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141 (18), 7235–7239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Hamley IW; Krysmann MJ Effect of PEG Crystallization on The Self-Assembly of PEG/Peptide Copolymers Containing Amyloid Peptide Fragments. Langmuir. 2008, 24 (15), 8210–8214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Zhang L; Jing D; Jiang N; Rojalin T; Baehr CM; Zhang D; Xiao W; Wu Y; Cong Z; Li JJ; Li Y; Wang L; Lam KS Transformable Peptide Nanoparticles Arrest HER2 Signaling and Cause Cancer Cell Death in Vivo. Nat. Nanotechnol 2020, 15 (2), 145–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Ren H; Zeng XZ; Zhao XX; Hou DY; Yao H; Yaseen M; Zhao L; Xu WH; Wang H; Li LL A Bioactivated in Vivo Assembly Nanotechnology Fabricated NIR Probe for Small Pancreatic Tumor Intraoperative Imaging. Nat. Commun 2022, 13, 418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Chen X; Zaro JL; Shen WC Fusion Protein Linkers: Property, Design and Functionality. Adv. Drug. Deliv. Rev 2013, 65 (10), 1357–1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Reddy Chichili VP; Kumar V; Sivaraman J Linkers in The Structural Biology of Protein-Protein Interactions. Protein. Sci 2013, 22 (2), 153–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).El-Baba TJ; Lutomski CA; Kantsadi AL; Malla TR; John T; Mikhailov V; Bolla JR; Schofield CJ; Zitzmann N; Vakonakis I; Robinson CV Allosteric Inhibition of The SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease: Insights from Mass Spectrometry Based Assays. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2020, 59 (52), 23544–23548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Jin Z; Du X; Xu Y; Deng Y; Liu M; Zhao Y; Zhang B; Li X; Zhang L; Peng C; Duan Y; Yu J; Wang L; Yang K; Liu F; Jiang R; Yang X; You T; Liu X; Yang X; Bai F; Liu H; Liu X; Guddat LW; Xu W; Xiao G; Qin C; Shi Z; Jiang H; Rao Z; Yang H Structure of M(pro) from SARS-CoV-2 and Discovery of Its Inhibitors. Nature 2020, 582 (7811), 289–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Futaki S. Membrane-Permeable Arginine-Rich Peptides and The Translocation Mechanisms. Adv. Drug. Deliv. Rev 2005, 57 (4), 547–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Perret F; Nishihara M; Takeuchi T; Futaki S; Lazar AN; Coleman AW; Sakai N; Matile S Anionic Fullerenes, Calixarenes, Coronenes, and Pyrenes as Activators of Oligo/Polyarginines in Model Membranes and Live Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127 (4), 1114–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Wender PA; Galliher WC; Goun EA; Jones LR; Pillow TH The Design of Guanidinium-Rich Transporters and Their Internalization Mechanisms. Adv. Drug. Deliv. Rev 2008, 60 (4-5), 452–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Peraro L; Kritzer JA Emerging Methods and Design Principles for Cell-Penetrant Peptides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2018, 57 (37), 11868–11881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Zhang W; Kwok RTK; Chen Y; Chen S; Zhao E; Yu CYY; Lam JWY; Zhang Q; Tang BZ Real-Time Monitoring of The Mitophagy Process by a Photostable Fluorescent Mitochondrion-Specific Bioprobe with AIE Characteristics. Chem. Commun 2015, 51 (43), 9022–9025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Luo GH; Xu TZ; Li X; Jiang W; Duo YH; Tang BZ Cellular Organelle-Targeted Smart AIEgens in Tumor Detection, Imaging and Therapeutics. Coordin. Chem. Rev 2022, 462, 214508. [Google Scholar]

- (66).Lv H; Zhang S; Wang B; Cui S; Yan J Toxicity of Cationic Lipids and Cationic Polymers in Gene Delivery. J. Control. Release 2006, 114 (1), 100–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Grimaldi N; Andrade F; Segovia N; Ferrer-Tasies L; Sala S; Veciana J; Ventosa N Lipid-Based Nanovesicles for Nanomedicine. Chem. Soc. Rev 2016, 45 (23), 6520–6545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Samanta S; He Y; Sharma A; Kim J; Pan W; Yang Z; Li J; Yan W; Liu L; Qu J; Kim JS Fluorescent Probes for Nanoscopic Imaging of Mitochondria. Chem. 2019, 5 (7), 1697–1726. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.