Abstract

Background:

Evidence supports endovascular coiling for ruptured intracranial aneurysms (RIAs). However, in some cases, it is difficult to achieve complete occlusion by coiling, such as with wide-neck aneurysms. We report our experience with intentional staged RIA treatment using targeted endovascular coiling at the rupture point in the acute phase, followed by delayed stent-assisted coiling, flow diverter stenting, or surgical clipping.

Methods:

Consecutive patients with RIAs treated between April 2015 and June 2021 were retrospectively investigated. Clinical characteristics, treatment complications, and patient outcomes data were collected.

Results:

Among 108 RIAs treated in our hospital, 60 patients underwent initial coiling; 10 patients underwent staged treatment. The aneurysm locations were the anterior communicating artery (n = 5), internal carotid-posterior communicating artery (n = 3), internal carotid-paraclinoid (n = 1), and vertebral artery-posterior inferior cerebellar artery (n = 1). The mean ± standard deviation aneurysmal diameter was 9.6 ± 5.4 mm and the mean aspect ratio was 1.2 ± 0.7. As the second treatment to obliterate blood flow to the neck area, we performed five stent-assisted coiling, two flow-diverter stentings, and three surgical clippings. Only one minor perioperative complication occurred. The median duration between the first and second treatments was 18 days (range, 14– 42 days). Good clinical outcome (modified Rankin scale score 0–2) at 90 days was achieved in 5 (50%) cases. The median follow-up duration was 6.5 months (range, 3–35 months); no rerupture occurred.

Conclusion:

Intentional staged treatment with a short time interval for RIA was effective and feasible.

Keywords: Coil embolization in acute phase, Ruptured intracranial aneurysm, Staged treatment

INTRODUCTION

Surgical clipping for ruptured intracranial aneurysms (RIA) is a well-established treatment.[2,14,27,28] However, difficulty performing the procedure due to issues such as brain swelling and obscured natural planes by blood, and a certain degree of morbidity has been reported.[3,9,20] In particular, intraoperative aneurysmal rupture is the most concerning and catastrophic complication for neurosurgeons and is a complication that may cause intraoperative death.

Evidence supporting endovascular coiling for RIA has been established.[22-24] Over 10 years of follow-up, patients in the endovascular treatment group were more likely to be alive and independent than were patients in the clipping group.[23] The safety and efficacy of endovascular coiling for RIA as a primary choice have also been reported.[1,6] In our country, the use of neck bridge stent or flow diverter (FD) for coil embolization in the acute stage of rupture is not permitted, and basically balloon-assisted embolization is required. However, cases often exist in which it is difficult to achieve complete occlusion by coiling, such as wide-neck aneurysms.[18]

Although stent-assisted coil embolization is effective in wide-neck aneurysms, there is no good evidence supporting stent-assisted coiling in RIA due to the high complication rate, especially thromboembolic complications under an insufficient effect of antiplatelet agents.[5,7] In these situations, the efficacy of stenting, including neck bridge stents and FD stents with or without coils, after initial coiling of acutely ruptured wide-neck intracranial aneurysms, so-called staged treatment, has been reported recently.[8,11,21] However, there is a paucity of data regarding staged treatment with a short time interval for RIA. In this study, we report a consecutive series of intentional staged treatment of RIA with targeted coiling mainly in the ruptured point in the acute phase to reduce the early rebleeding risk followed by surgical clipping, stent-assisted coiling, or FD stenting in the subacute phase.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of our institution and was performed in accordance with the committee’s guidelines (Approval number: 18025). All patients provided consent. Using a prospectively collected neurovascular database, consecutive patients with RIAs managed at our hospital between April 2015 and June 2021 were retrospectively investigated. All patients who underwent intentional staged treatment for RIAs with targeted endovascular embolization at the ruptured point in the acute phase followed by a second treatment with stent-assisted embolization, FD stenting, or surgical clipping were enrolled in this study. In all cases, operations were performed under general anesthesia and patients were kept under severe sedation for a few days after initial embolization to prevent rerupture, as we considered that thromboses of the aneurysms were occurred during those days. The second treatment was selected based on imaging evaluation at the time of presentation. The patients’ clinical characteristics were collected, namely, age, sex, location of the aneurysm, World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies (WFNS) grade, treatment complications, days between the two treatments, and final modified Rankin scale (mRS) score.

RESULTS

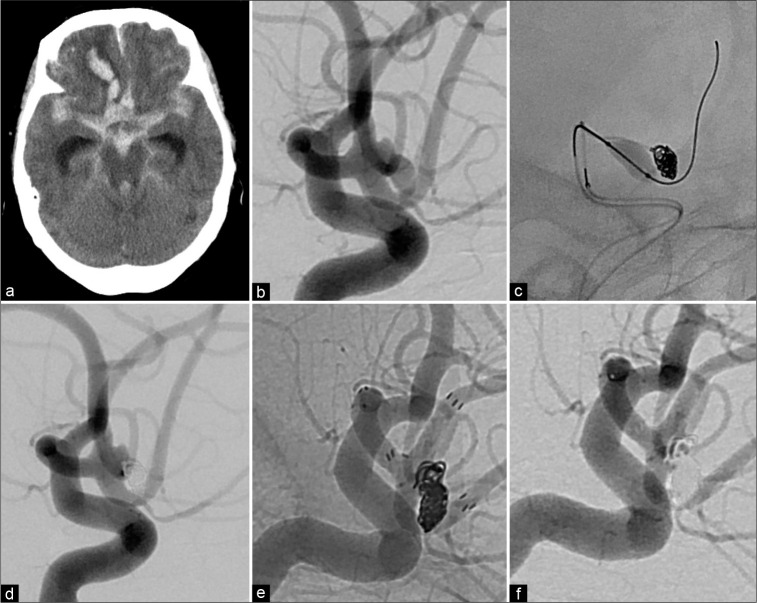

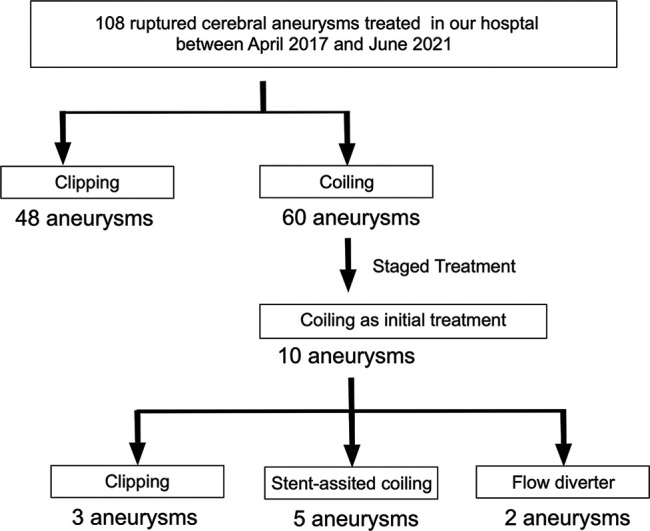

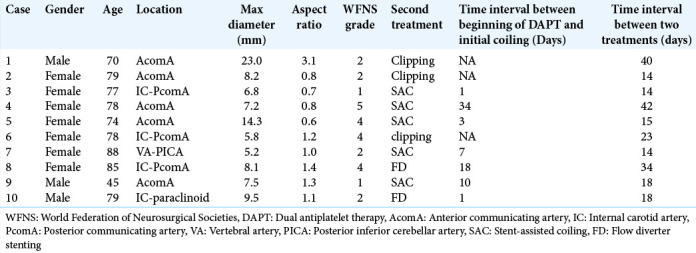

Between April 2015 and June 2021, 108 RIAs were treated in our hospital. Sixty patients were treated with coil embolization, and 10 of these patients underwent staged treatment [Figure 1]. The patients’ characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The mean age was 75.3 ± 11.8 years, and seven patients were female. The aneurysm locations were the anterior communicating artery (AcomA) (n = 5), internal carotid-posterior communicating artery (IC-PcomA) (n = 3), IC-paraclinoid (n = 1), and vertebral artery-posterior inferior cerebellar artery (n = 1). The mean aneurysmal diameter was 9.6 ± 5.4 mm, the mean dome-to-neck ratio was 1.6 ± 1.0, and the mean aspect ratio was 1.2 ± 0.7.

Figure 1:

Flowchart of the patient selection.

Table 1:

Summary of clinical characteristics in patients treated with staged treatment.

Treatment, complications, and clinical outcomes

As the second treatment to obliterate blood flow to the neck area, five stent-assisted coil embolization, three surgical clippings, and two FD stentings were performed. In the 20 treatment procedures (10 cases undergoing two procedures), only one perioperative complication occurred. Specifically, intraparenchymal hemorrhage occurred about 10 h after stent-assisted coil embolization for an AcomA aneurysm; however, the patient was discharged with an mRS score of 1. The median duration between the first and second treatments was 18 days (range, 14–42 days). Rerupture between these treatments did not occur. Good clinical outcome, defined as an mRs score of 0–2, at 90 days, was achieved in 5 (50%) cases. The median follow-up duration was 6.5 months (range, 3–35 days), with no rerupture. Recanalization occurred in one case 8 months after stent-assisted coil embolization for an AcomA aneurysm. Additional embolization was performed successfully, and the patient has been free from complications.

Representative cases

Case 4

A 78-year-old female patient was brought to our hospital because of impaired consciousness. Computed tomography (CT) and CT angiography showed subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) due to rupture of a 4 mm AcomA aneurysm; the WFNS grade was 5 [Figure 2a]. The aneurysm was treated on the day of presentation with balloon-assisted coil embolization [Figures 2b and c]. We judged that coiling the neck region of the aneurysm without a stent would be associated with a high risk of coils protruding into the parent artery; thus, we decided to perform staged treatment [Figure 2d]. Dual antiplatelet therapy was started 34 days after the initial embolization, and stent-assisted coil embolization was performed 42 days after the initial embolization without complications [Figures 2e and f]. Rerupture of the aneurysm did not occur during hospitalization. The patient was transferred to a rehabilitation hospital with an mRS score of 4.

Figure 2:

Representative case. (a) Computed tomography image showing diffuse subarachnoid hemorrhage and intraparenchymal hemorrhage in the right frontal lobe. (b) Working projection of the initial angiogram. (c) Working projection of the angiogram obtained during the first treatment showing coil embolization with balloon-assisted coil embolization. (d) Three-dimensional reconstruction image of the final angiogram of the first treatment showing obstruction of the aneurysmal dome except for the neck region. (e) Working projection of the final angiogram (native image) of the definitive treatment showing obstruction of the entire aneurysmal dome. (f) Working projection of the final angiogram of the definitive treatment showing obstruction of the entire aneurysmal dome.

Case 6

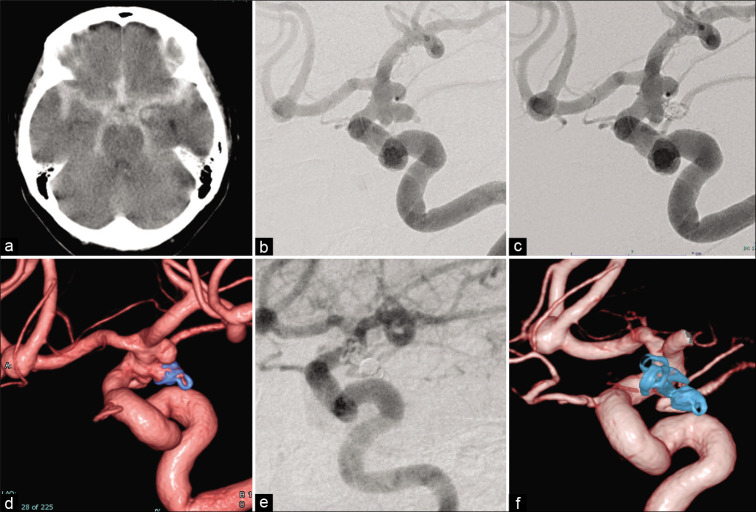

A 78-year-old female was brought to our hospital because of impaired consciousness. CT and CT angiography showed SAH due to rupture of a 6.5 mm left IC-PcomA aneurysm; the WFNS grade was 4 [Figure 3a]. Endovascular treatment was performed on the day of presentation. Because the PcomA originated from the neck of the aneurysm, it was difficult to completely embolize with the balloon-assisted technique [Figure 3b]. Therefore, we decided to perform staged treatment [Figures 3c and d]. The patient had another aneurysm located at the bifurcation of the left IC and anterior choroidal artery. This aneurysm was difficult to coil owing to its small size. To treat both aneurysms, surgical clipping was performed 24 days after the initial coiling, without complications [Figures 3e and f]. Rerupture of the aneurysm did not occur during hospitalization, and she was transferred to a rehabilitation hospital with an mRS score of 4.

Figure 3:

Representative case. (a) Computed tomography showing diffuse subarachnoid hemorrhage. (b) Working projection of the initial angiogram. The arrow shows the aneurysmal bleb (presumed rupture point). (c) Working projection of the final angiogram of the first treatment showing obstruction of the aneurysmal dome except for the neck region. (d) Three-dimensional reconstruction image of the final angiogram of the first treatment showing obstruction of the aneurysmal dome except for the neck region. (e) Working projection of the final angiogram of the definitive treatment showing obstruction of the entire aneurysmal dome. (f) Three-dimensional reconstruction image of the final angiogram of the definitive treatment showing obstruction of the entire aneurysmal dome.

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrated the feasibility and efficacy of intentional staged treatment for RIA with targeted endovascular embolization at the rupture point in the acute phase followed by a second treatment comprising stent-assisted embolization, FD stenting, or surgical clipping.

Surgical clipping is a well-established treatment for RIAs;[2,14,27,28] however, intraoperative aneurysmal rupture is the most concerning complication and causes substantial mental stress for neurosurgeons, especially when the operation is performed solitary during a night sift. Although the inclusion criteria vary, not infrequently, the reported incidence of intraoperative aneurysmal rupture ranges from 6% to 20%.[4,12,13,17]

The International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial concluded that the survival rate and favorable outcome (mRS score: 0–2) rate 10 years after SAH treated with coil embolization are higher than those obtained after surgical clipping.[23] Since these results were published, a growing number of SAH patients have been treated with coil embolization.[1,29] However, physicians often encounter cases in which it is difficult to achieve complete occlusion by endovascular coiling, such as with wide-neck aneurysms.[18] A subgroup analysis using the barrow ruptured aneurysm trial data concluded that the aneurysm obliteration rate was lower, and the retreatment rate was higher, in the coiling group compared with that in the clipping group, with ruptured wide-neck aneurysms.[18] In these situations, rerupture after coil embolization is a problem that must be considered. Regarding the acute phase, the cerebral aneurysm rerupture after treatment study demonstrated that the degree of aneurysmal occlusion was strongly related to rerupture. Aneurysms that were <70% occluded had a 17.6% rerupture rate with a median time to rerupture of 3 days.[16] Notably, Jartti et al. reported that the early rebleeding rate of 8.8% among incompletely coiled ruptured aneurysms could be decreased to 2.0% with neck remnant occlusion.[15] For this reason, we try to embolize as far as possible up to the neck remnant in the initial embolization.

Considering previous findings, staged treatment of ruptured wide-neck aneurysm by placing coils as safely as possible without stents in the acute phase and treating the remaining area around the aneurysmal neck by clipping, stent-assisted coiling, or FD stenting might be an effective treatment concept.[8,11,21,30] Mine et al. evaluated the strategy of staged endovascular treatment of RIAs, including coiling, in the acute phase with complementary stenting with or without coiling in the subacute phase in 23 cases.[18] No rebleeding occurred during the mean delay of 24.3 days between the initial coiling and stenting.[21] Feng et al. evaluated the same strategy in 47 cases.[17] No rebleeding occurred during the median interval of 4.2 weeks between the initial coiling and stenting.[11] Brinjikji et al. evaluated the strategy of staged endovascular treatment of RIAs with coiling in the acute phase followed by delayed FD stenting in 27 cases.[16] One case of aneurysmal rebleeding occurred during the mean interval of 16 weeks between the initial coiling and FD stenting.[8] The time interval between the initial coiling and definitive treatment might be important. In the present study, the median time between intentional partial coiling and definitive treatment was 18 days. Excluding three surgical clipping cases as definitive treatment, patients received dual antiplatelet therapy in the acute phase. None of the patients experienced rebleeding in the time between the intentional partial coiling and definitive treatment. Our study suggests a possible beneficial effect of staged treatment in a shorter period than that reported previously.

Using vessel wall magnetic resonance imaging, wall enhancement of a cerebral aneurysm has been revealed as a characteristic of ruptured aneurysms.[10,19,25] Omodaka et al. investigated the vessel wall imaging of ruptured and unruptured intracranial aneurysms using three-dimensional T1-weighted fast spin echo sequence images.[30] The authors found that the bleb of the aneurysm, which was likely to be the ruptured site, was locally enhanced in some cases. The authors suggested that a thrombus or the platelet plug within or around the ruptured site might be enhanced in these cases.[26] With research developments in imaging of the aneurysmal wall, the ruptured point of the aneurysm might be identified more specifically in the near future, and staged treatment comprising intentional partial coiling around the ruptured point followed by delayed definitive treatment could be performed more safely and effectively.

Limitations

The most critical limitation of this study is its retrospective nature, which may have resulted in selection bias. However, there were no failed cases among the intentional staged treatment cases. In addition, this study reviewed patients over an approximately 5-year period, during which new therapeutic devices and techniques were developed, particularly FD stents. Considering this limitation, treatment bias could not be avoided. Finally, this case series is limited by its small sample size. There were only a few aneurysms in each location, and the appropriate second treatment method and our conclusions require a large prospective study for confirmation.

CONCLUSION

Intentional staged treatment of RIAs with coil embolization in the acute phase followed by a second treatment with stent-assisted embolization, FD stenting, or surgical clipping was effective and feasible with a short time interval. This strategy could be an option for cases in which both surgical clipping and primary coil embolization are challenging.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Early-Career Scientists from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science to 18K16582.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jane Charbonneau, DVM, from Edanz (https://jp.edanz.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Footnotes

How to cite this article: Yamazaki H, Fujinaka T, Ozaki T, Kidani T, Nishimoto K, Taki K, et al. Staged treatment for ruptured wide-neck intracranial aneurysm with intentional partial coiling in the acute phase followed by definitive treatment. Surg Neurol Int 2022;13:322.

Contributor Information

Hiroki Yamazaki, Email: blue.1201.3@gmail.com.

Toshiyuki Fujinaka, Email: fujinaka@nsurg.med.osaka-u.ac.jp.

Tomohiko Ozaki, Email: tomohikoozaki@gmail.com.

Tomoki Kidani, Email: kkkkidani@ybb.ne.jp.

Keisuke Nishimoto, Email: 24mo10kei@gmail.com.

Kowashi Taki, Email: k.taki0303@gmail.com.

Naoki Nishizawa, Email: n.nishizawa44@gmail.com.

Keijiro Murakami, Email: keijiroxyz@gmail.com.

Yonehiro Kanemura, Email: yonehirok@gmail.com.

Shin Nakajima, Email: amijakan212@yahoo.co.jp.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Grant-in-Aid for Early-Career Scientists from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (18K16582).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.AlMatter M, Bhogal P, Aguilar Pérez M, Hellstern V, Bäzner H, Ganslandt O, et al. Evaluation of safety, efficacy and clinical outcome after endovascular treatment of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage in coil-first setting. A 10-year series from a single center. J Neuroradiol. 2018;45:349–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neurad.2018.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Auer LM. Acute operation and preventive nimodipine improve outcome in patients with ruptured cerebral aneurysms. Neurosurgery. 1984;15:57–66. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198407000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ayling OG, Ibrahim GM, Drake B, Torner JC, Macdonald RL. Operative complications and differences in outcome after clipping and coiling of ruptured intracranial aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 2015;123:621–8. doi: 10.3171/2014.11.JNS141607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Batjer H, Samson D. Intraoperative aneurysmal rupture: Incidence, outcome, and suggestions for surgical management. Neurosurgery. 1986;18:701–7. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198606000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bechan RS, Sprengers ME, Majoie CB, Peluso JP, Sluzewski M, van Rooij WJ. Stent-assisted coil embolization of intracranial aneurysms: Complications in acutely ruptured versus unruptured aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2016;37:502–7. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berro DH, L’Allinec V, Pasco-Papon A, Emery E, Berro M, Barbier C, et al. Clip-first policy versus coil-first policy for the exclusion of middle cerebral artery aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 2019;133:1–8. doi: 10.3171/2019.5.JNS19373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Billingsley JT, Hoh BL. Stent-assisted coil embolization. J Neurosurg. 2014;121:1–2. doi: 10.3171/2013.11.JNS132203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brinjikji W, Piano M, Fang S, Pero G, Kallmes DF, Quilici L, et al. Treatment of ruptured complex and large/giant ruptured cerebral aneurysms by acute coiling followed by staged flow diversion. J Neurosurg. 2016;125:120–7. doi: 10.3171/2015.6.JNS151038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bulters DO, Santarius T, Chia HL, Parker RA, Trivedi R, Kirkpatrick PJ, et al. Causes of neurological deficits following clipping of 200 consecutive ruptured aneurysms in patients with good-grade aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2011;153:295–303. doi: 10.1007/s00701-010-0896-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edjlali M, Gentric JC, Régent-Rodriguez C, Trystram D, Hassen WB, Lion S, et al. Does aneurysmal wall enhancement on vessel wall MRI help to distinguish stable from unstable intracranial aneurysms? Stroke. 2014;45:3704–6. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.006626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng Z, Zuo Q, Yang P, Li Q, Zhao R, Hong B, et al. Staged stenting with or without additional coils after conventional initial coiling of acute ruptured wide-neck intracranial aneurysms. World Neurosurg. 2017;108:506–12. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giannotta SL, Oppenheimer JH, Levy ML, Zelman V. Management of intraoperative rupture of aneurysm without hypotension. Neurosurgery. 1991;28:531–5. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199104000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Houkin K, Kuroda S, Takahashi A, Takikawa S, Ishikawa T, Yoshimoto T, et al. Intra-operative premature rupture of the cerebral aneurysms. Analysis of the causes and management. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1999;141:1255–63. doi: 10.1007/s007010050428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inagawa T. Effect of early operation on cerebral vasospasm. Surg Neurol. 1990;33:239–46. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(90)90042-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jartti P, Isokangas JM, Karttunen A, Jartti A, Haapea M, Koskelainen T, et al. Early rebleeding after coiling of ruptured intracranial aneurysms. Acta Radiol. 2010;51:1043–9. doi: 10.3109/02841851.2010.508172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnston SC, Dowd CF, Higashida RT, Lawton MT, Duckwiler GR, Gress DR, et al. Predictors of rehemorrhage after treatment of ruptured intracranial aneurysms: The cerebral aneurysm rerupture after treatment (CARAT) study. Stroke. 2008;39:120–5. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.495747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jomin M, Lesoin F, Lozes G. Prognosis with 500 ruptured and operated intracranial arterial aneurysms. Surg Neurol. 1984;21:13–8. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(84)90393-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mascitelli JR, Lawton MT, Hendricks BK, Nakaji P, Zabramski JM, Spetzler RF. Analysis of wide-neck aneurysms in the barrow ruptured aneurysm trial. Neurosurgery. 2019;85:622–31. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyy439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matouk CC, Mandell DM, Günel M, Bulsara KR, Malhotra A, Hebert R, et al. Vessel wall magnetic resonance imaging identifies the site of rupture in patients with multiple intracranial aneurysms: Proof of principle. Neurosurgery. 2013;72:492–6. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e31827d1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McLaughlin N, Bojanowski MW. Early surgery-related complications after aneurysm clip placement: An analysis of causes and patient outcomes. J Neurosurg. 2004;101:600–6. doi: 10.3171/jns.2004.101.4.0600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mine B, Bonnet T, Vazquez-Suarez JC, Ligot N, Lubicz B. Evaluation of clinical and anatomical outcome of staged stenting after acute coiling of ruptured intracranial aneurysms. Interv Neuroradiol. 2020;26:260–7. doi: 10.1177/1591019919891602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Molyneux A, Kerr R, Stratton I, Sandercock P, Clarke M, Shrimpton J, et al. International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) of neurosurgical clipping versus endovascular coiling in 2143 patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms: A randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360:1267–74. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11314-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Molyneux AJ, Birks J, Clarke A, Sneade M, Kerr RS. The durability of endovascular coiling versus neurosurgical clipping of ruptured cerebral aneurysms: 18 year follow-up of the UK cohort of the International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) Lancet. 2015;385:691–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60975-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Molyneux AJ, Kerr RS, Yu LM, Clarke M, Sneade M, Yarnold JA, et al. International subarachnoid aneurysm trial (ISAT) of neurosurgical clipping versus endovascular coiling in 2143 patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms: A randomised comparison of effects on survival, dependency, seizures, rebleeding, subgroups, and aneurysm occlusion. Lancet. 2005;366:809–17. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67214-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagahata S, Nagahata M, Obara M, Kondo R, Minagawa N, Sato S, et al. Wall enhancement of the intracranial aneurysms revealed by magnetic resonance vessel wall imaging using three-dimensional turbo spin-echo sequence with motion-sensitized driven-equilibrium: A sign of ruptured aneurysm? Clin Neuroradiol. 2016;26:277–83. doi: 10.1007/s00062-014-0353-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Omodaka S, Endo H, Niizuma K, Fujimura M, Inoue T, Sato K, et al. Quantitative assessment of circumferential enhancement along the wall of cerebral aneurysms using MR imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2016;37:1262–6. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spetzler RF, McDougall CG, Zabramski JM, Albuquerque FC, Hills NK, Nakaji P, et al. Ten-year analysis of saccular aneurysms in the Barrow Ruptured Aneurysm Trial. J Neurosurg. 2019;132:771–6. doi: 10.3171/2018.8.JNS181846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spetzler RF, Zabramski JM, McDougall CG, Albuquerque FC, Hills NK, Wallace RC, et al. Analysis of saccular aneurysms in the barrow ruptured aneurysm trial. J Neurosurg. 2018;128:120–5. doi: 10.3171/2016.9.JNS161301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steklacova A, Bradac O, de Lacy P, Lacman J, Charvat F, Benes V. “Coil mainly” policy in management of intracranial ACoA aneurysms: Single-centre experience with the systematic review of literature and meta-analysis. Neurosurg Rev. 2018;41:825–39. doi: 10.1007/s10143-017-0932-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waldau B, Reavey-Cantwell JF, Lawson MF, Jahshan S, Levy EI, Siddiqui AH, et al. Intentional partial coiling dome protection of complex ruptured cerebral aneurysms prevents acute rebleeding and produces favorable clinical outcomes. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2012;154:27–31. doi: 10.1007/s00701-011-1214-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]