Abstract

The existence of precursor lesions for invasive cervical cancer has been recognized for more than 50 years. Our understanding of the pathobiology and behavior of cervical cancer precursors has evolved considerably over the past five decades. Furthermore, the terminology used to classify pre-invasive lesions of the cervix has frequently changed. The realization that human papillomavirus (HPV) infections constitute a morphologic continuum has prompted efforts to include them within a single classification system, specifically the squamous intraepithelial lesions (SILs) which have now been embraced by the surgical pathologists. The reduced number of specific pathological categories has made clinical decision-making more straightforward. The generic criteria for SIL have two important histological parameters: Alterations in the density of superficial epithelial cells and superficial squamous atypia. The flat condyloma or cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) I is generally associated with intermediate and high-risk HPV types as against the low-risk viruses that cause exophytic/papillary growth patterns of condylomas. The diagnosis of low-grade SIL (LSIL) (flat and exophytic condylomas) requires first excluding benign mimics of LSIL and second to confirm the characteristic cytologic atypia. For high-grade SILs (HSILs), the extent and degree of atypia generally exceed the limits of that described in flat or exophytic condylomas (LSILs). Less maturation, abnormal cell differentiation, loss of cell polarity, and increased mitotic index with abnormal mitotic figures occupying increasing thickness of the epithelium define a lesion as CIN II or CIN III. Atypical immature metaplasia associated with inflammation and atrophy is a challenge in cervical biopsy interpretation. Careful attention to the growth pattern of the epithelium, the distribution of the atypia, nuclear spacing, and the degree of anisokaryosis and the presence of enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei help in differentiating a non-neoplastic from a neoplastic process. This chapter describes in depth the diagnostic difficulties in the interpretation of cervical biopsies. It also provides useful criteria in distinguishing benign mimics from true precancerous lesions and the role of biomarkers such as the p16ink4 and Ki-67 in the differential diagnosis of precursor lesions and the reactive and metaplastic epithelium.

Keywords: Atypical Immature metaplasia, biomarkers in cervical precancers, Mitosis in cervical biopsy, pseudokoilocytes in cervical biopsies, SILs-diagnostic difficulties in cervical biopsy

INTRODUCTION AND TERMINOLOGY

It was known for long that there are epithelial abnormalities adjoining the invasive carcinoma cervix.[1] The term dysplasia came into being for cervical abnormalities which showed features midway between those of carcinoma in situ and normal cervical epithelium.[2] There have been rapid advances in research on cervical carcinoma over the past few decades. Human papillomavirus (HPV) is now known as the causative agent of cervical cancer and has been found in almost all cervical cancers.[3] The term cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) was introduced by Richart who used it to describe all lesions which were precursors of squamous cell carcinoma.[4] Cervical squamous intraepithelial neoplasia refers to all squamous alterations that occur in or near the transformation zone in association with HPV infection, thereby encompassing the terms condyloma, CIN, dysplasia, and squamous intraepithelial lesions (SILs).[5]

With better understanding of the biology and pathogenesis of these lesions, we now have categories of precancerous lesions that are fewer in number and are also very specific. These have helped us define these lesions in a better way, leading to better clinical decision-making. The most widely used, “twotiered” classification of the Bethesda System (TBS) for cervical cytology, that is, low-grade SIL (LSIL) and high-grade (HSIL), is now being used for histopathological description also.[6] The SIL terminology has gained wide acceptance, but there are still many who prefer the CIN terminology, in most instances, primarily because of customary usage. However, it is recommended to use the diagnostic terminology proposed by the LAST (Lower Anogenital Squamous Terminology) committee which is based on TBS of classification, for surgical pathology specimens. The LAST recommendations are of providing a two-part diagnosis, with SIL first and the equivalent CIN in parenthesis thereafter. LSIL will thus appear as “LSIL (CIN 1).” The distinction between CIN2 and CIN3 is arbitrary and not significant from management point of view and so both are considered under HSIL and written as “HSIL (CIN2/CIN3).”[7]

In general, while diagnosing CIN in cervical biopsies, one should focus on maturation of the squamous epithelium, an overall cellular disorganization, loss of cell polarity, presence of nuclear atypia in lower and upper layers, increased mitotic index (MI) with mitosis in upper half of the epithelium, and abnormal mitotic figures in some cases. Broadly, CIN1 is used when these features occupy the lower one-third of the cervical epithelium. CIN 2 is used when these are seen in the lower one-third to two-thirds of the epithelium and CIN 3 when two-thirds or the entire thickness of the epithelium is showing atypical basaloid cells.

LOW-GRADE SILS-LSIL (CIN1)

LSIL (CIN1) may be identified at any age following the onset of sexual activity which also marks the beginning of chances of acquiring various sexually transmitted infections, one of them being the HPV infection. The HPV causes three different types of clinical diseases – warts, dysplasia, and cancer – mostly in or around the genital area. The HPVs are highly epitheliotropic and have an affinity for the squamous epithelium of the lower genital tract, but the HR HPV types, in particular, have a tropism for the metaplastic squamous cells at the squamocolumnar junction.[8,9] This has very important consequences related to cytology screening as most precursor lesions and cancers arise at this site, which is amenable to sampling with a brush or spatula.

Clinically, “elevated warty” lesions also known as Condyloma acuminatum are less common on the cervix and are generally pure warty lesions. These are induced by the HPV-types 6 and 11 in 70–90% of the cases, but occasionally other types – such as HPV-16 and 18 are encountered. When the latter is the case, high-grade cytologic atypia is often found. Much more common are the “subclinical condylomas” that can be flat, spiked, or inverted condylomas or show simply warty atypia. These are of more concern as they are non-exophytic, and can only be identified during colposcopy as they turn white after application of 5% acetic acid. Koilocytic viral cytopathic effect is the pathognomonic feature of both exophytic and flat condylomas. Both these lesions, particularly the subclinical HPV lesions, can be (i) pure constellation of koilocytes in the middle and upper layers of the squamous epithelium or they can be (ii) pure CIN1 lesions without koilocytosis. It is doubtful whether LSIL (CIN1), as an indicator of HPV infection, can be reproducibly diagnosed in the absence of koilocytotic change. Therefore, the practice of reporting whether or not there is dysplasia within this condyloma (i.e., condyloma ± CIN1) is no longer followed.[10]

HISTOPATHOLOGY

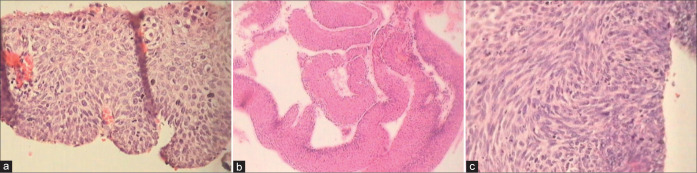

The normal cervical epithelium has a basket weave appearance with equidistant regular proliferating capillaries at the SCJ. Glands are seen beneath the squamous epithelium [Figure 1]

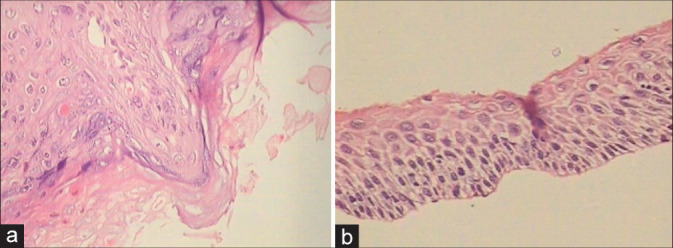

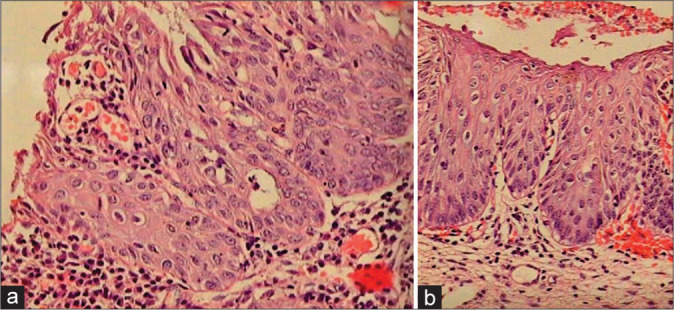

Histopathology of exophytic lesions exhibits thickening of the epithelium (acanthosis) with variable papillomatosis [Figure 2] and viral cytopathic effect. As compared to the inflamed or metaplastic cervical squamous epithelium, the proliferation rate of condyloma is higher and is particularly elevated in the presence of HR HPV types[11-13]

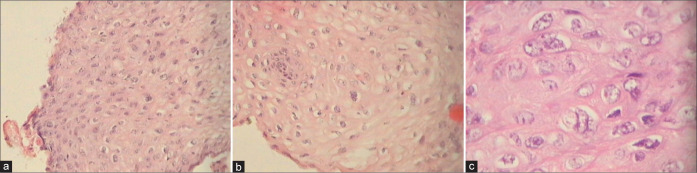

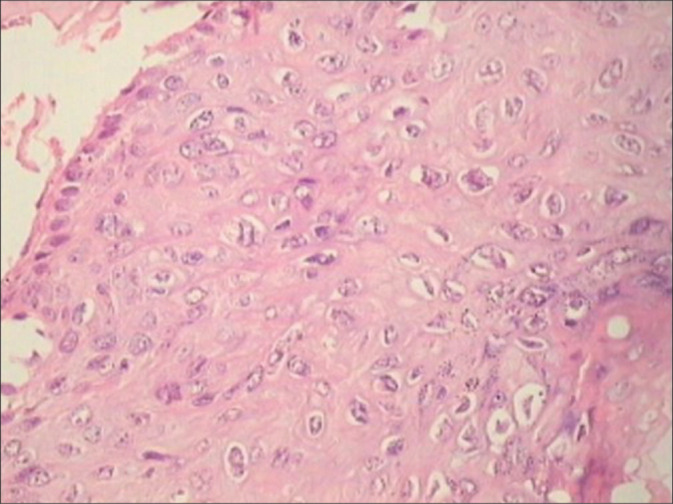

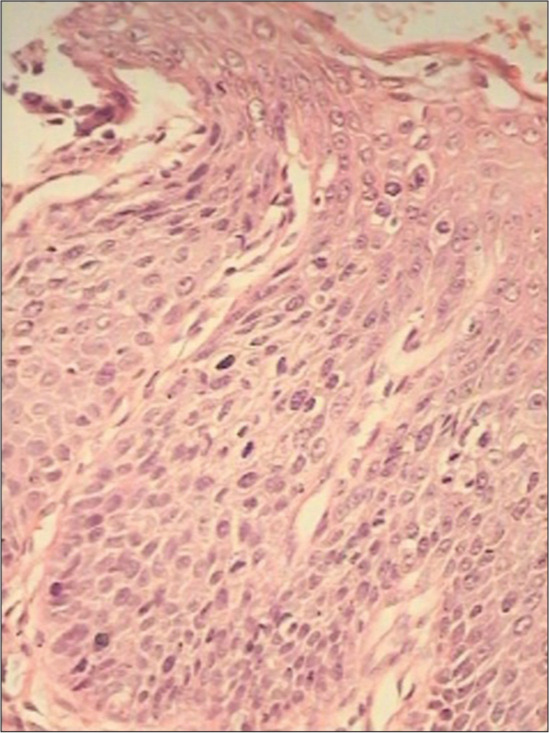

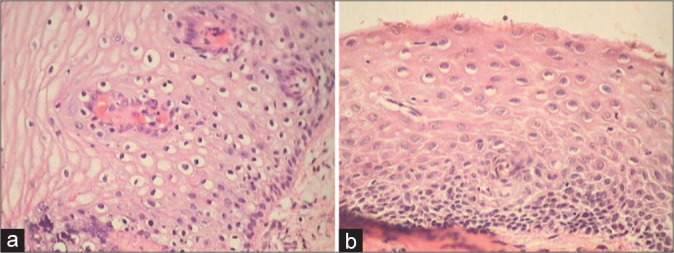

Microscopically, these clinically different lesions share the following features: Relatively normal basal cell layer, expanded or hyperplastic parabasal cell layer [Figure 3a and b], orderly maturation, mitotic activity (but few or no abnormal mitoses), and koilocytosis [Figure 4]

The abnormal maturation, abnormal cell proliferation, and atypia (in SIL) are exemplified by nuclear enlargement, hyperchromatic nuclei, increased N/C ratio, abnormal chromatin distribution with coarse chromatin, irregular and wrinkled nuclear membrane, and nuclear pleomorphism[14]

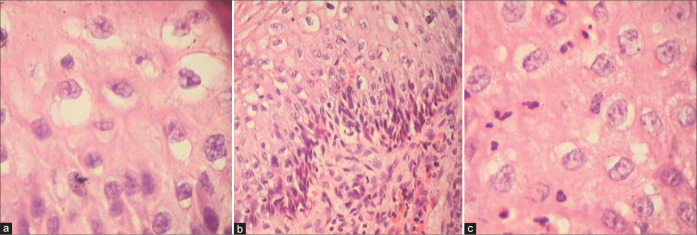

Koilocytotic atypia is seen in the middle and upper portions of the epithelium [Figure 5]. Keep in mind, the “atypia on the surface epithelium” as it avoids overdiagnosis

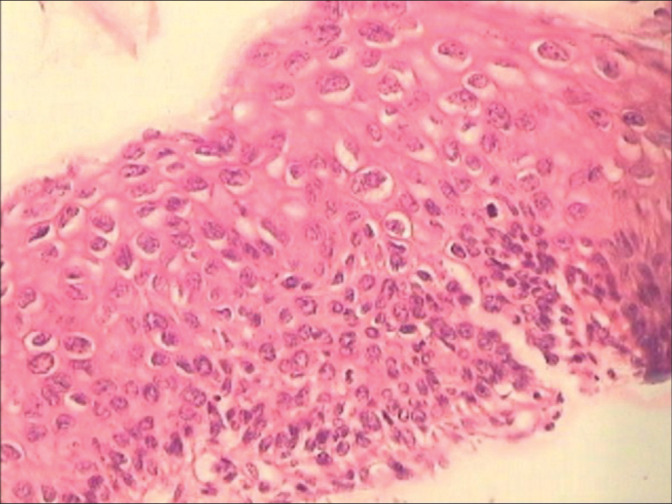

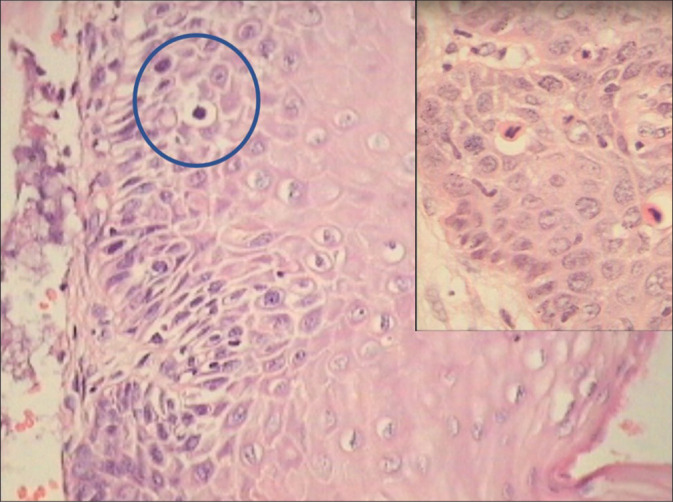

Koilocytotic atypia is a constellation of cellular changes that include marked variation in nuclear size (3 fold) and shape, wrinkled nuclei, hyperchromasia, binucleation or multinucleation, and perinuclear halos.[15] Multinucleated cells are due to changes in mitosis [Figure 6]

-

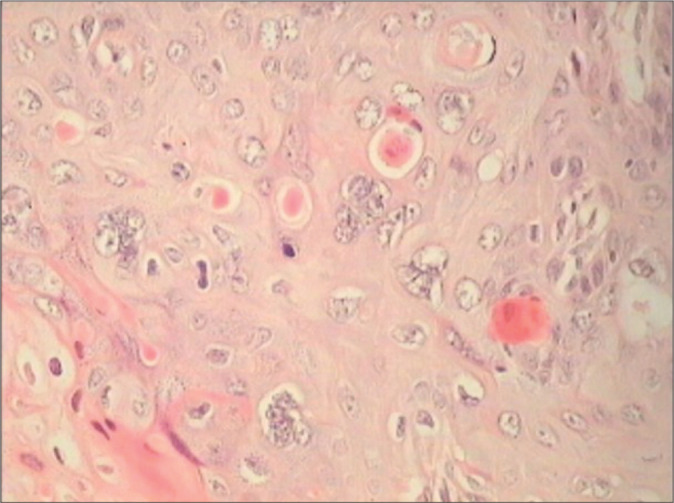

Uneven spacing of the nuclei is characteristic giving the impression of “clones” as seen in cartilage [Figure 7]

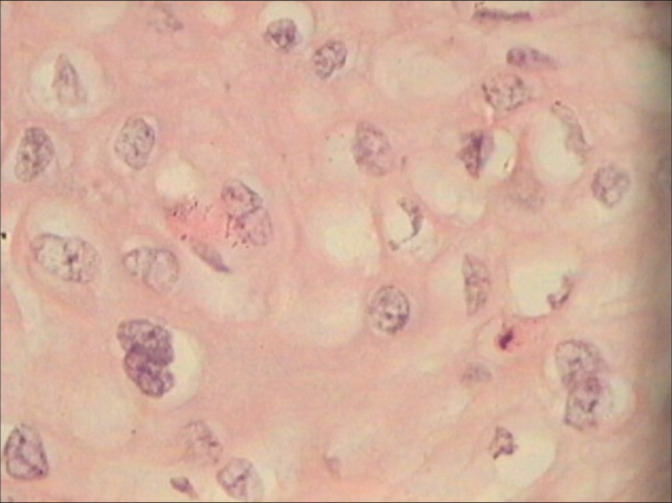

- Nuclear atypia and perinuclear halos are characteristic features of koilocytes. There is perinuclear cytoplasmic vacuolation with thickening of cytoplasmic membrane or peripheral condensation of cytoplasm. We see these perinuclear halos in the superficial layers and they are better appreciated in cytology smears

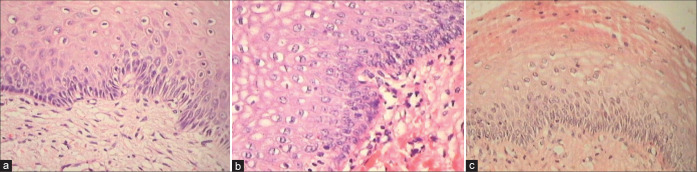

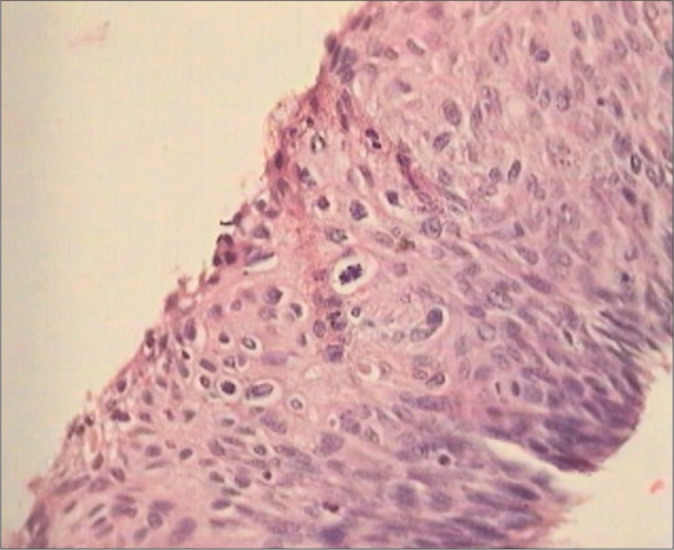

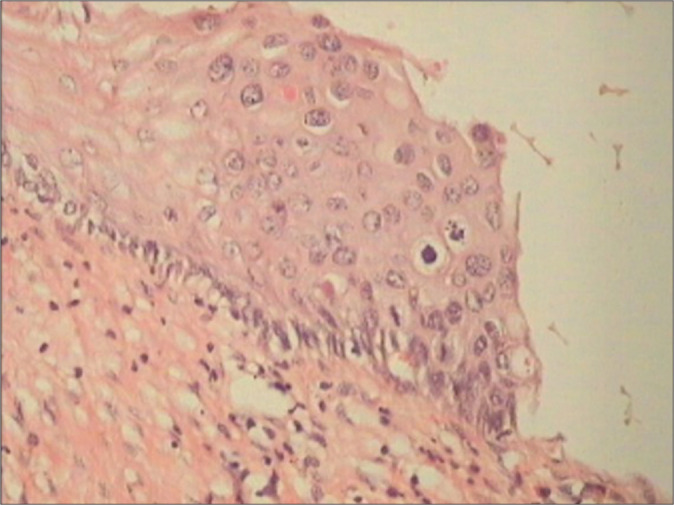

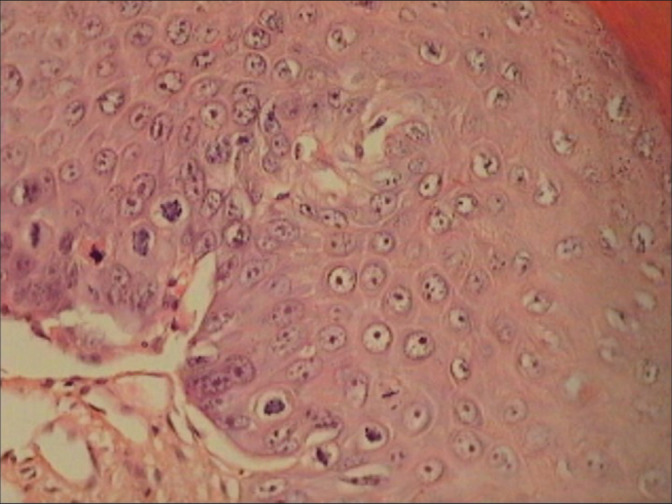

Histopathology of flat condylomata has a similar appearance but lacks the papillary architecture of an exophytic lesion [Figure 8a and b][16]

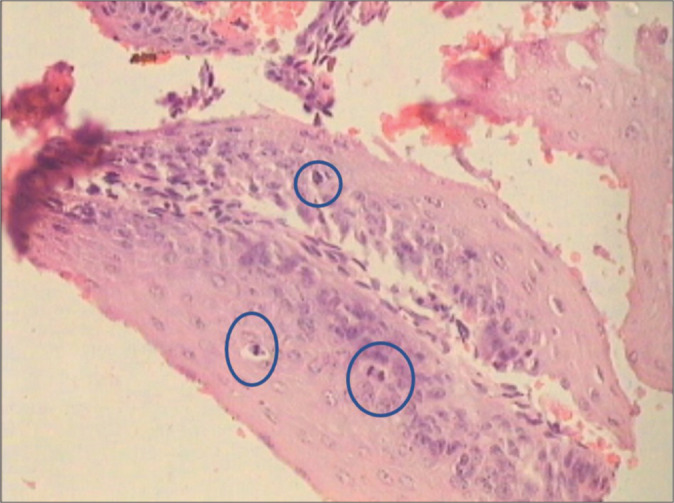

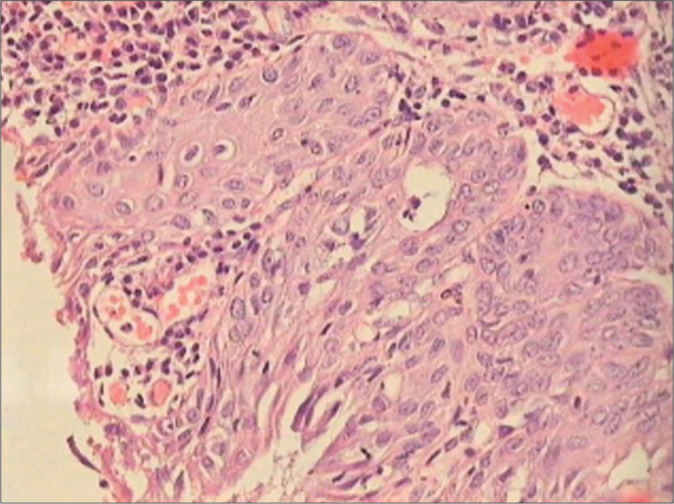

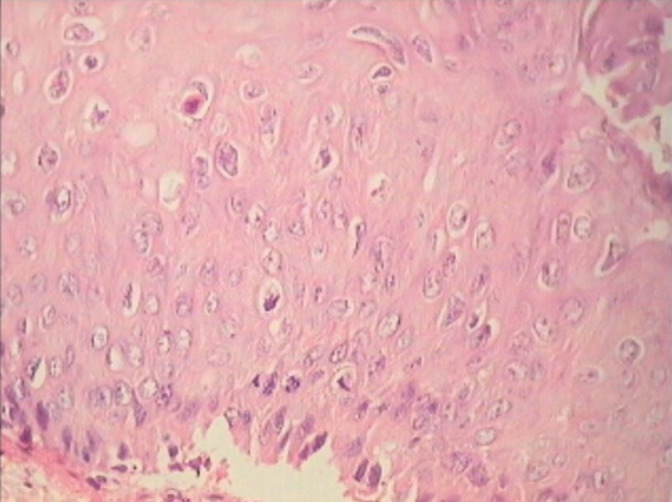

Flat lesions with features of LSILs (flat condylomata) without koilocytotic atypia, that is, pure CIN1 lesions, show mitosis in the lower one-third of the epithelium, loss of polarity of nuclei, and marked nuclear atypia and mitosis in the basal layer [Figure 9a-c]

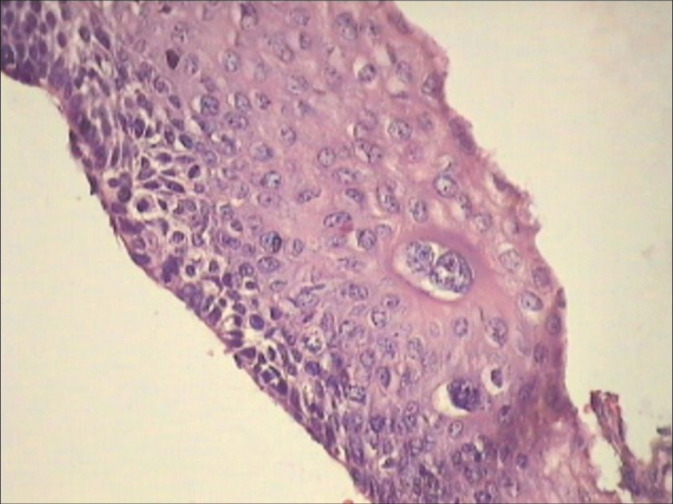

However, LSIL do not harbor many abnormal mitotic figures and therefore a lesion with high MI must be carefully evaluated to decide whether it can be upgraded to HSIL [Figure 10].

Although CIN1 is also induced by HPV infection, it takes a morphologic backseat in many cases. However, biopsies may show features of both CIN1 and HPV cytopathic effects [Figure 11]

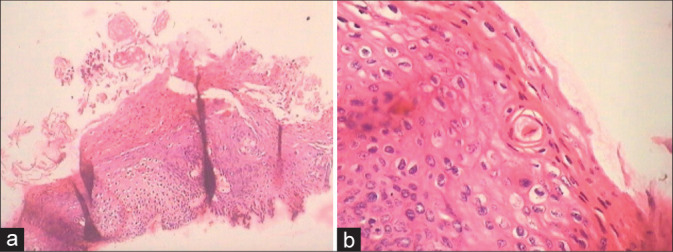

Hyperkeratosis, atypical or pleomorphic parakeratosis, individual cell keratinization, and dyskeratosis are other features of warty HPV lesions [Figure 12a and b].

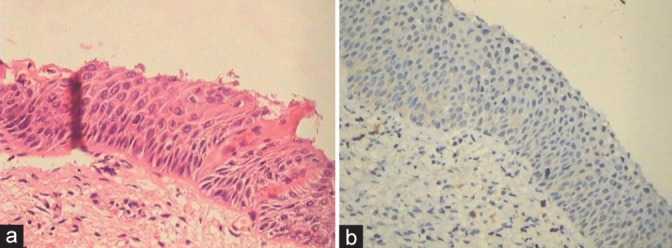

Figure 1:

Cervical biopsy – normal basket weave appearance with equidistant regular proliferating capillaries at the SCJ. Glands are seen beneath the squamous epithelium.

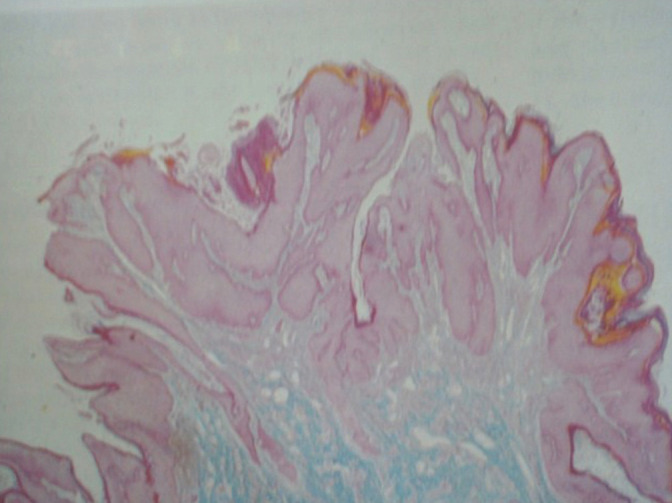

Figure 2:

Exophytic condyloma (×5) showing papillomatosis and acanthosis in a warty lesion.

Figure 3:

(a and b) Condyloma showing hyperplasia of basal layers in (a) and absence of distinct basal cell layer but focally present as seen in the lower left corner (b). Bizarre nuclei are seen within the proliferating epithelium along with orderly maturation.

Figure 4:

Cervical biopsy showing a normal basal layer with maturation and koilocytotic atypia.

Figure 5:

Cervical tissue is showing indistinct basal layer with hyperplasia of parabasal cells with minimal nuclear atypia. Koilocytosis and loss of polarity of intermediate and superficial cells are present along with significant nuclear atypia in the upper third of the epithelium.

Figure 6:

Multinucleation and single-cell dyskeratosis are seen in HPV infection.

Figure 7:

Clones of koilocytes are seen concentrated randomly throughout the epithelium. Perinuclear halos and nuclear atypia are characteristic features of koilocytes.

Figure 8:

(a and b) Spiky (a) condyloma. The surface of the spikes shows hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, and koilocytes beneath (×10). (b) Flat condyloma lacks the papillary architecture of an exophytic lesion (×10). Both these generally present as subclinical condylomas and are detected only when they turn acetowhite after application of 5% acetic acid or during colposcopy.

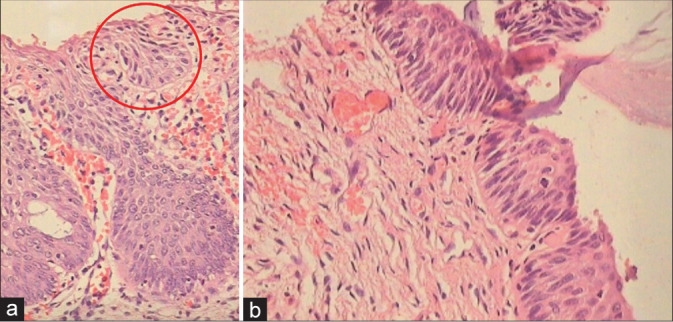

Figure 9:

(a-c) For the diagnosis of pure CIN1, it is necessary to identify alterations in the lower third of the epithelium with mitosis (a and b blue circles) ×40, loss of picket fence arrangement of the basal cells, and focal loss of polarity of atypical hyperchromatic cells, acanthosis, and mitosis ×5.

Figure 10:

CIN1 showing high mitotic index. The mitotic figures are seen in the blue circles.

Figure 11:

Cervical biopsy showing features of both CIN1 and HPV in the form of koilocytotic atypia, bizarre nuclei, and multinucleation. This patient was HPV DNA positive. Colposcopic impression was HSIL.

Figure 12:

(a and b) Cervical biopsies showing hyperkeratosis (a), atypical or pleomorphic parakeratosis, individual cell keratinization, and dyskeratosis (b).

HSIL

Clinically, HSILs, when extensive, present as an unhealthy cervix that bleeds on touch, but are best appreciated and evaluated colposcopically.

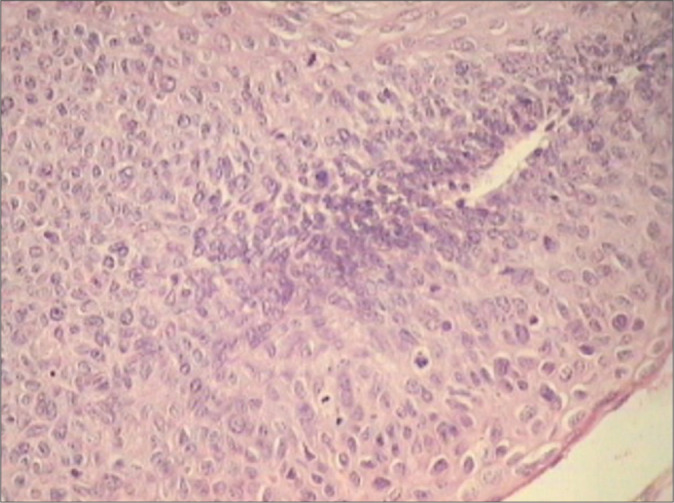

Microscopically, these lesions are distinguished from LSIL by the presence of mild to marked cytologic atypia encompassing the lower 2/3rds of the squamous epithelium

There are nuclear crowding and loss of polarity of cells

There are loss of normal maturation and thereby accumulation of primitive basaloid appearing cells. However, a variable degree of surface maturation may be observed [Figure 13]

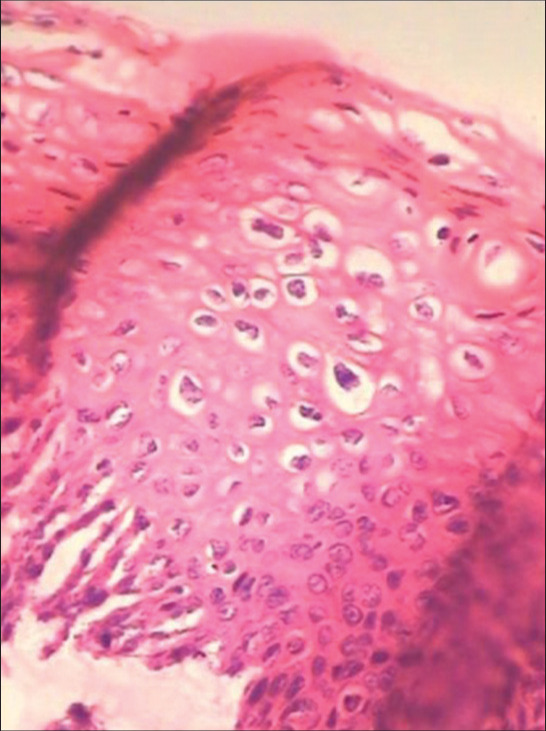

Some lesions exhibit surface koilocytotic change and epithelial maturation and make it difficult to distinguish LSIL from HSIL that corresponds to CIN II [Figure 14]. Those lesions that show little or no maturation correspond to CIN III. Basaloid (immature) cells are seen in more than one-third of the epithelium [Figure 15a]

These cells are round to oval and have an increased N: C ratio

There is nuclear atypia in the form of hyperchromasia, coarse chromatin, membrane irregularities, and variable degree of nuclear pleomorphism, which generally exceeds that of LSIL and is present in all layers of epithelium. The atypia is often bizarre

There is prominent mitotic activity and an increase in MI is seen. Atypical mitotic figures are typically present and may be seen in the upper layers of the epithelium

At times, it is required to decide whether the lesion is LSIL or HSIL. In such situations, p16 immunostaining can help resolve the dilemma. However, please remember that morphological diagnosis using H & E stain is the mainstay and adjunctive studies using p16 are useful only in selected few borderline cases. If there is strong and diffuse block positivity, a diagnosis of HSIL (CIN1/2) can be rendered.[17]

Once the pathologist has made the diagnosis of HSIL (CIN1/2) in a cervical biopsy, it is the responsibility of the gynecologist to determine the presence or absence of invasive carcinoma

Variants of HSIL keratinizing HSIL are characterized by superficial keratinization in addition to atypia

Thorough sampling and sectioning of therapeutically excised tissue help to rule in/out invasive carcinoma [Figure 15b and c]

Atypical keratinized cells may be seen in smears in some benign cellular reactions such as hyperkeratosis or parakeratosis, atypia of undetermined significance, some LSILs and HSILs, and invasive squamous cell carcinomas

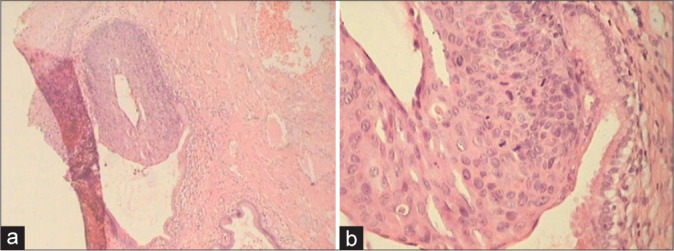

HSILs with immature metaplastic differentiation comprise immature cells which appear uniform with variable cytoplasmic differentiation and rounded or undulating epithelial stromal interface. These retain certain features of immature metaplasia [Figure 16]

In contrast to conventional metaplasia, these HSILs with a metaplastic phenotype exhibit reduced superficial cell maturation, maintain a relatively high nuclear density on the surface with hyperchromasia, and lack uniform cytoplasmic borders in these cells

Glandular crypt involvement is also a feature of HSILs with immature metaplastic differentiation [Figure 17a and b]

Figure 13:

Section from tissue obtained by LEEP is showing less maturation, higher nuclear density, and a less orderly transition from immature to mature epithelial layers ×40.

Figure 14:

Section from cervical biopsy from a HPV DNA-positive woman shows histological features of LSIL (CIN2) with surface showing koilocytotic atypia. The distinction of LSIL and HSIL is based primarily on the presence of atypia in the latter that does not fit within the spectrum of a flat or exophytic condyloma. Assessment of lower epithelial layers for hypercellularity, nuclear pleomorphism, and abnormal mitosis can help in distinguishing between these two entities with some consistency. Such lesions are referred to as mature or koilocytotic HSIL (CIN2).

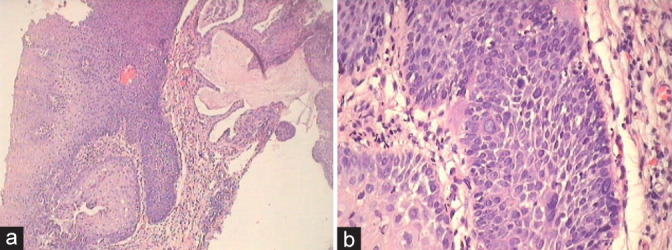

Figure 15:

(a-c) Section from tissue obtained by LEEP is showing full-thickness nuclear atypia in basaloid cells, loss of cell polarity, and a high mitotic index ×40. Thorough sampling of sufficiently excised tissue (b) is required to rule in/out invasive malignancy. (c) HSIL with a high mitotic index. Swirling of nuclei, known as the wind swept appearance, a feature of SILs is seen.

Figure 16:

HSIL with an immature metaplastic phenotype. Observe the rounded stromal-epithelial interface. Characteristic is increased nuclear density in the upper layers, the appearance of syncytium of nuclei in the superficial epithelium, nuclear hyperchromasia, and increased mitosis.

Figure 17:

(a and b) HSIL involving glandular crypts. Colposcopic diagnosis was HSIL (a) ×5 and (b) ×40.

SILS – DIAGNOSTIC DIFFICULTIES IN CERVICAL BIOPSIES

Although it is important not to miss SILs, the overdiagnosis of benign atypia also has important clinical implications and can result in undue physical and psychological distress, to both the patient and the team of doctors. However, there are instances, however, in which a clear interpretation is not possible because of cell changes that are difficult to classify.

When the histopathologic features of HPV infection (namely, koilocytosis, multinucleation, acanthosis, papillomatosis, parakeratosis, individual cell keratinization, mitosis in the lower basal third of the epithelium, hyperplasia of basal layers, and absence of distinct basal cell layer) are either less striking of SIL or are inconsistently present or they are only mildly/focally evident, such lesions result in a report of questionable importance for the treating gynecologist. Diverse nomenclature has been used like atypical squamous lesions (ASL) or atypical lesions (AL) for the subset of biopsies for which the histologic diagnosis is of unclear significance.[18,19] The biologic behavior of ASL and its relationship to HPV infections is still not well understood and also not well-defined.[20-23] The diagnosis of ASL often is used by pathologists to describe histologically borderline conditions, including neoplastic and non-neoplastic processes in the uterine cervix.[24,25] The various conditions included in the category of ASL are atypical repair or reactive changes, atrophy, atypical immature metaplasia (AIM), transitional metaplasia, and dysplasia or carcinoma with metaplastic changes. The word “atypical” is a common denominator in these terminologies meaning that which is not typical of a pathology. The term atypia may also be used by some as a defensive measure to avoid a potential legal entanglement.

From the colposcopist point of view, both, that is, AL and metaplastic/reactive lesions and SILs appear as acetowhite foci, and hence biopsied and represent one of the most frequent challenges in routine surgical pathology practice. The colposcopist takes a punch biopsy either when he wants to confirm histologically an undeniable CIN of any grade so that he can proceed with ablative procedures such as loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) or cold knife conization OR when the colposcopic findings are ambiguous. Moreover, therefore, while taking a biopsy, it requires real sufficient experience to differentiate a benign from atypical or premalignant lesion in the acetowhite spectrum of an “atypical transformation zone.”

In cytological diagnosis, the borderline category or the gray lesions of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US) of cervical lesions have been widely accepted. In contrast, leave apart the introduction of a borderline category in histological diagnosis, even the term atypia is not acceptable and is strongly criticized for several reasons.[26-28] First, everyone thinks that biopsy is the final answer to all clinical differentials and the pathologist will narrow down ambiguous results of all previous investigations. Second, there is high rate of intra- and inter-observer disagreement in distinguishing reactive lesions on one hand and pre-cancers on the other. Third, cervical reactive/metaplastic conditions and SILs can also be present adjacently, making the diagnosis all the more difficult. In addition, a clear trend to overdiagnose normal, metaplastic, or reactive cervical biopsies as HPV-associated LSIL has been reported, with therapeutic, reproductive, sexual, and social consequences.[29,30]

In the ALTS study, biopsy specimens were obtained because of a cytologic diagnosis of ASCUS or LSIL and were triaged with HPV DNA test. The biopsies were reviewed independently by five experienced pathologists. The rate of dysplasia ranged from 23% to 51%. All pathologists agreed in 28%. Point is that, in spite of the fact that straightforward criteria for reactive and precancerous lesions are clearly defined, we must accept that subjectivity is universal in reporting pre-cancers and specially LSIL (CIN1).[31]

To improve the diagnosis and management of histological AL, it would be important to identify among them those lesions that are really HPV associated and above all, that they are harboring hrHPV DNA. Continuous efforts have been made to evaluate various histologic and cytologic features in the original samples of ASL for their ability to differentiate neoplastic from non-neoplastic lesions as determined by subsequent tissue diagnoses or sufficient follow-up with multiple cytologic tests.[32,33] Attempts have been made not only to make a clear distinction between neoplastic and nonneoplastic groups but also to eliminate the ASL category, for lesions in the uterine cervix, through the application of morphologic and immunohistochemical criteria. The immunostaining patterns for p16 and Ki-67 of the original ASL samples were evaluated with an easy and clearly defined method by determining the presence or absence of positive cells in the upper two-thirds of the squamous epithelial layer. The histologic and cytologic features that potentially could separate neoplastic (or malignant) from non-neoplastic (or benign) groups in ASLs are as follows:

These criteria are most useful and also most necessary in – distinguishing LSIL from benign reactive atypia and HSIL from atrophy and immature metaplasia.

Mitosis: Any mitotic figure, normal or abnormal, present or absent, in the squamous epithelium

Nuclear appearance: Predominantly hyperchromatic (>50%) without recognizable nucleoli or predominantly vesicular (>50%) with recognizable nucleoli or nuclear grooves

Nuclear growth pattern: Predominantly horizontal (>50%) or predominantly vertical (>50%)

Perinuclear halo: Present or absent with a dense cytoplasmic rim

Cell border: Distinct or indistinct in more than 50% of the squamous cells

Primitive cells: Cells with a nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio of more than 50%, present or absent, in the upper third of the squamous cell layer

Inflammation: Neutrophils or lymphocytes present or absent, within the epithelial layer.

DIFFERENTIATING LSIL FROM REACTIVE EPITHELIAL CHANGES (NON-SPECIFIC)

-

The presence of mitosis is one of the most important histologic indicators for the neoplastic group. To eliminate subjectivity of observations – making a genuine search for mitosis is often rewarding

- In a normal cervix, the normal basal cells hardly ever show a mitotic figure and parabasal cells of a reactive epithelium may rarely show mitosis. Therefore, just the presence or absence of a normal or abnormal mitosis may be as much as necessary to label the lesion as favoring neoplastic. Although, only abnormal mitotic figures are considered indicators of CIN in some reports[15,34,35]

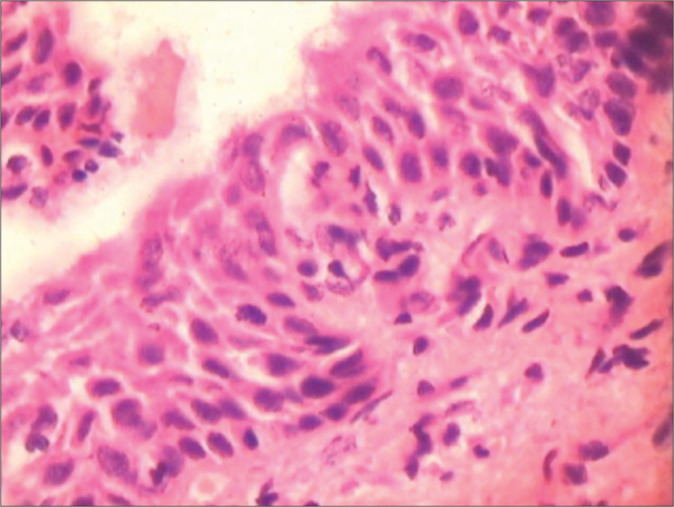

- Even if the nuclear atypia in the surrounding cells is not marked presence of many mitotic figure favors a neoplastic process [Figure 18]

- However, the atypical areas where one wants to look for mitosis sometimes are so limited in the original sections that practically it is not possible to identify and quantify the mitotic figures per microscopic field. In such situations, go ahead with serial and deep sections [Figure 19]. This way one can improve the diagnosis of LSIL in additional 20% of cases. A mitotic count of 6/10 high-power fields favors LSIL. Furthermore, taking additional or multiple biopsies during colposcopy improve significantly the detection rate of SILs[36]

- In fact, when mitotic figures are identified easily, it is recommended that such mitotically active CIN I may be upgraded to CIN II when it is positive for high-risk (HR) HPV DNA. Increasing CIN grade is associated with increasing MI [Figure 20].[37] Earlier studies have observed that the capability of pathologists to differentiate between CIN1 and CIN2 is poor and there is a school of thoughts who recommended that CIN2 should be considered among the low-grade abnormalities rather than high-grade ones. Even from natural history point of view, very few of the CIN2 lesions progress further

- Primarily differences in size and staining of intermediate and superficial cells and a combination of cytoplasmic features, nuclear features, and the growth pattern helps one distinguish nonspecific changes from SILs. In LSIL, cytoplasm is capable of maturation but nuclei retain the karyokinetic abilities of younger cells. Nucleomegaly with hyperchromasia in mature looking cells with or without perinuclear halo is what one has to look for to call it a LSIL

- The most important discriminating feature between benign and neoplastic lesion is absence of variance, in either cell size or staining intensity and nuclear abnormalities in the cell population [Figure 21]

-

Benign mimics of koilocytes or “pseudo-koilocytosis” are most troublesome and most common in acute or chronic inflammatory lesions. They are as a result of irritation of the epithelium because of variety of factors such as infections due to Candida, Trichomonas, and Gardnerella vaginalis

- Koilocytosis resulting from inflammatory cell changes may cause slight nuclear abnormalities and narrow perinuclear clear zones

- The halos are usually regular, round, and uniform in appearance, with centrally placed nuclei. Narrowness and regular appearance of the perinuclear zone along with fairly well-preserved horizontal stratification of nuclei is seen in nonneoplastic lesions. These features are at a substantial variance with classic koilocytotic atypia [Figure 23]

- Another common source of pseudo-koilocytes is the intermediate squamous cells, filled with glycogen. However, they lack the hyperchromasia, overall enlargement of size of nuclei >3 times the nuclei of corresponding normal layer, and they also lack thick rim of cytoplasm. Under higher magnification, the nuclei are vesicular and are not hyperchromatic and nuclear grooves are seen

- Vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli are most unusual of dysplastic epithelium. Nuclei showing hyperchromasia or vesicular appearance – although important – is not statistically significant in differentiating neoplastic from non-neoplastic lesions [Figures 24 and 25][19]

- The abnormalities in a true neoplastic lesion are generally striking and focal

- However, focal and few abnormalities with mild nuclear atypia may create a suspicion of CIN I. Such minor abnormalities are the source of maximum subjective variation. If these abnormalities are seen in >50% of the tissue provided, one may report it as favoring a neoplastic process or LSIL

-

The overall growth pattern of the epithelium with mild nuclear abnormalities shows a horizontal and fairly regular stratification of nuclei that favors a nonneoplastic lesion

- A vertical orientation of nuclei in more than 50% areas, in the biopsy provided, is an indication of immaturity of cells and favor a neoplastic lesion [Figure 26]

- Quite often normal slides are miscategorized as LSIL and vice versa as a result of focal loss of a regular basal layer. Hyperplasia of basal layers and absence of a distinct basal cell layer are considered as features of HPV infection. However, the converse is also reported. It is reported that a normal basal cell layer is usually maintained both in a condyloma and in CIN 1.[20]

- At times, especially in cases of atrophy, there are only one or two para basal layers with mild-to-moderate atypia and with focal absence of a distinct basal cell layer [Figure 27]

- On the other hand, it may be difficult to categorize focal basal cell hyperplasia (one of the features of HPV infection). Remember, focal basal cell hyperplasia may also be associated with the use of oral contraceptives or intrauterine device, pregnancy, healing erosions, inflammations, and infections [Figure 28a-c].

- These focal and few abnormalities with mild nuclear atypia may create a suspicion of CIN1. However, if these abnormalities are seen in >50% of the tissue provided, one may report it as favoring a neoplastic process or LSIL.

In general, in infection, considerable numbers of inflammatory cells are seen within the epithelium or in adjacent areas and this favors a reactive process [Figure 24].

Figure 18:

hrHPV DNA-positive patient with colposcopic findings that favored LSIL. Section showed mild atypia in the basal layer with mitosis figures in the blue circle.

Figure 19:

Section is showing a small focus favoring LSIL adjacent to normal epithelium. The abnormalities in a true neoplastic lesion are generally strikingly focal. The presence of a single mitosis in the light of positive hrHPV DNA and colposcopic findings favoring LSIL helped in signing it out as LSIL.

Figure 20:

Increasing CIN grade is associated with increasing mitotic index (MI). A lesion difficult to label as CIN1 as there are atypia and mitosis seen in upper two-thirds of the epithelium also. This patient was hrHPV DNA positive with colposcopic impression as HSIL.

Figure 21:

(a-c) Biopsies from both these patients (a and b) who were hrHPV DNA positive had colposcopic findings that favored LSIL. However, there is the absence of variance in size of cells and nuclei as compared to figure (c) which is an out and out LSIL. Multiple biopsies during colposcopy improve significantly the detection rate of SILs.

Figure 22:

hrHPV DNA positive. Colposcopic findings favored LSIL. Section shows frequent binucleation of large hyperchromatic nuclei in the mature squamous cells.

Figure 23:

(a and b) If slight nuclear enlargement affects a large proportion of squamous epithelium in a biopsy, it is unlikely to be neoplastic. Observe the narrowness and regular appearance of the perinuclear clear zones along with fairly well-preserved horizontal stratification of nuclei.

Figure 24:

(a) Cytoplasmic vacuolation alone should not be diagnosed as koilocytosis. A common source of pseudo-koilocytes is the intermediate squamous cells, filled with glycogen and/or reactive atypia, and is not accompanied by nuclear atypia. Under higher magnification, the nuclei are vesicular with nuclear grooves and are not hyperchromatic. (b and c) Mild degree of loss of polarity in the basal layers with mild-to-moderate atypia in upper three layers of the epithelium along with perinuclear clearing. One may be tempted to call this as a LSIL encompassing HPV infection despite the presence of inflammation in the stroma and also encroaching the squamous epithelium.

Figure 25:

Vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli are most unusual of dysplastic epithelium. Even if the nuclear atypia is not marked, the presence of many mitotic figures favors a neoplastic process. Nuclear appearance hyperchromasia or vesicular – although important – is not statistically significant in differentiating neoplastic from non-neoplastic lesions.

Figure 26:

Vertical orientation of nuclei favors a neoplastic process. hrHPV DNA was positive in this patient.

Figure 27:

Atrophic epithelium may show thinning or very few layers and also focal hyperplasia making it difficult to distinguish between a LSIL and HSIL.

Figure 28:

(a-c) Quite often normal slides are miscategorized as LSIL and vice versa as a result of focal loss of a regular basal layer. Basal cell hyper hyperplasia may be associated with the use of oral contraceptives or use of IUCD, during pregnancy, inflammation and repair and infections.

DIFFERENTIATING HSIL FROM AIM AND ATROPHY

Atypical Immature Metaplasia (AIM)

The proposed categories of AIM[22,24] and transitional metaplasia[23,25] of the uterine cervix are considered borderline lesions histologically.[42] These are fraught with two facts, one is that their biologic and clinical characteristics are yet to be determined and second is the fact that there is substantial interobserver variability in the interpretation of their histopathologic findings

Most immature squamous metaplasia have no cytologic atypia (typical immature metaplasia), while a small percentage can show mild atypia (so-called atypical immature squamous metaplasia or AIM)

The term AIM was introduced in 1983 to describe cervical lesions with uniform full-thickness basal proliferation with high nuclear density but without sufficient criteria for CIN III (now HSIL)

AIM refers to a full-thickness intraepithelial basaloid lesion in the uterine cervix that features both metaplasia and atypia and is, therefore, difficult to distinguish from CIN III

Atypical or immature metaplasia is an ill-defined histologic entity that is either benign, neoplastic ab initio, or may be a step in the development of low- or high-grade lesions of metaplastic type. Possibility of LSIL in immature or atypical metaplasia must be entertained or cannot be ruled out when the basal layers start showing all features of CIN I and there is marked atypia with mitosis. Immature metaplasia is a fertile soil for HPV infection and integration. It may evolve to both LSIL and HSIL. HPV DNA test is positive in 70–80% of cases [Figure 29a and b]

AIM represents a heterogeneous group of lesions and is characterized by absent or minimal maturation of metaplastic squamous epithelium, absent or minimal koilocytosis, and mild nuclear pleomorphism

Ancillary testing using a panel of CK17, p16ink4 may help resolve the issue. p16 is a marker for HPV-induced dysplasia. Cytokeratin (CK) 17 is a marker for cervical reserve (stem) cells, which give rise to metaplasia.

Figure 29:

(a and b) Possibility of LSIL in immature or atypical metaplasia cannot be ruled out when the basal layers start showing all features of CIN I and there is marked atypia with mitosis (a). This metaplastic epithelium in (b) is showing koilocytosis with nuclear atypia in addition to immature metaplasia.

Microscopic (histologic) description

-

To differentiate AIM from HSIL in cervical biopsies, it is recommended to make use of these three modalities:

- Appropriate selection of histologic and cytologic criteria, seven criteria described by Chisa and Ayoma [Table 1] with a determination to consistently apply them to selected lesions can resolve many of our diagnostic problems

- Second, we have the facility of HPV DNA testing to validate our findings. hrHPV DNA testing, when possible should be done as it does help to clarify the clinical significance of ASL/AIM. The presence of HR oncogenic viral types (e.g., HPV-16 and 18) would confer a different clinical importance, compared to low-risk types (e.g., HPV-6 and 11)

- Third, a host of molecular markers for tissue diagnosis is available and IHC can be helpful in differentiating benign from neoplastic lesions, for example, Ki-67+ cells (nuclear staining) usually show scattered staining and are evenly distributed throughout the squamous epithelium of neoplastic ASLs.

Table 1:

Histologic and cytologic criteria to differentiate typical immature metaplasia from AIM and HSIL

| Typical immature metaplasia | Atypical immature metaplasia | HSIL |

|---|---|---|

| Monotonous population of cells with a high N: C ratio that lacks cytoplasmic maturation in the superficial layers. Nucleoli are seen | Monotonous population of cells with a high N: C ratio that lacks cytoplasmic maturation in the superficial layers. Nucleoli may be seen | Monotonous population of cells with a high N: C ratio that lacks cytoplasmic maturation in the superficial layers Nucleoli generally not seen |

| Minimal or no cell crowding, the nuclei are evenly spaced, mild-to-moderate enlargement, minimal anisokaryosis, uniform, and vertical orientation of nuclei | cell crowding present, anisokaryosis may or may not be seen | surface atypia and nuclear crowding are observed |

| The cytoplasmic margins and desmosomal junctions are recognized | The cytoplasmic margins and desmosomal junctions are not recognized | The cytoplasmic margins and desmosomal junctions are not recognized |

| Mitoses are uncommon, if present, are typical, and confined to basal layers | Mitosis are seen and at times in the upper third of the epithelium | Mitosis are seen and at times in the upper third of the epithelium and mitotic index may be high |

| In addition, these changes will be accompanied by acute and chronic inflammatory cells and spongiosis. | Inflammation may be present in the stroma but inflammatory cells are generally seen encroaching the epithelium | Inflammatory cells are generally seen encroaching not seen within the epithelium |

| Ki67 may be negative or positive with scattered patterns | Ki67 is positive with scattered patterns | Positive and evenly distributed all cases of HG-SIL are positive for Ki67 |

| CK17 can be positive | CK17 can be positive | CK17 can be positive in immature squamous metaplasia and in some CIN |

| Typical IM and mature squamous metaplasia is consistently negative for p16 | Immunoreactivity to p16 is not seen | In contrast, immunoreactivity to p16 is seen |

| hrHPV DNA is negative | hrHPV DNA may be positive | hrHPV DNA is generally positive |

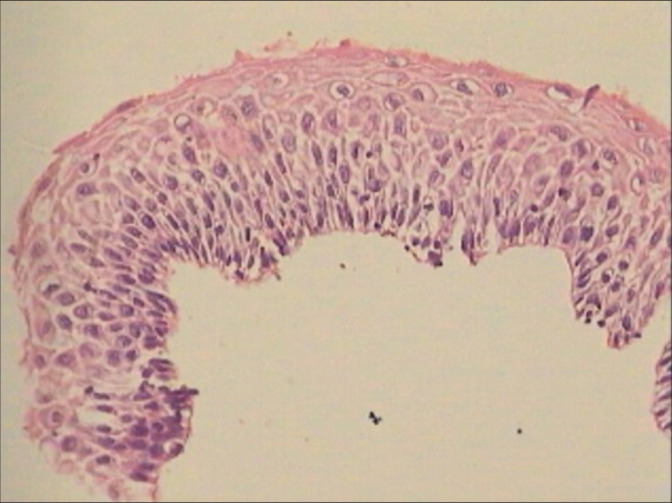

When Atypical Immature squamous metaplasia is composed of a monotonous population of cells with a high N:C ratio, cell crowding and a high mitotic index, the closest differential is HSIL. As against a typical immature metaplasia (IM), that has minimal cell crowding, the nuclei are evenly spaced with mild-to-moderate enlargement but minimal anisokaryosis and uniform and vertical orientation of nuclei are seen and the cytoplasmic margins and desmosomal junctions are recognized [Figure 30a and b].

Figure 30:

(a and b) Atypical immature metaplasia showing mild crowding of nuclei, mitosis, and rounded or undulating epithelial stromal interface. Desmosomes are not visible in the lower third of the epithelium. Maturation is seen in the upper layers. The area circled shows features of HSIL. (b) section shows variably hyperchromatic and vertically orientated nuclei with mitotic activity in upper layers clearly favor a neoplastic and a HSIL lesion. The very thin epithelium may reflect loss of upper epithelial layers because of fragility of these lesions. These cases are reminiscent of the “clinging” form of carcinoma in situ of the bladder.

Atrophy

Atrophy is exceedingly difficult to distinguish from HSIL. Features that are helpful are as follows:

Presence of hyperchromatic but generally uniform nuclei. The epithelium is thin or with very few layers of cells that are with maintained polarity. The nuclear appearance is predominantly smudgy, hyperchromatic without recognizable nucleoli and often their internal structure is no longer discernible [Figure 31]

The diagnosis is reached mainly by careful comparison of the abnormal cells with adjacent dry, but normal, squamous cells and an assessment of the relative nuclear hyperchromasia and altered nucleocytoplasmic ratio. In spite of the accumulated experience, there are situations where lingering doubts will persist as to whether an atrophic smear is benign or contains cells suspicious of cancer

In atrophy, at times, the SILs are derived from reserve or basal cells of the endocervical epithelium. It is composed of small round atypical cells which replace the epithelium lining the endocervical canal. The lesion may extend to the transformation zone located higher up in the canal and, therefore, represents a diagnostic challenge to the colposcopist. The lesion is beyond the reach of the colposcope and is often detected in the specimen of endocervical curettage [Figure 32]

In the presence of inflammation, whether this is a HSIL of the small cell type or immature metaplasia with atypia is extremely difficult to qualify

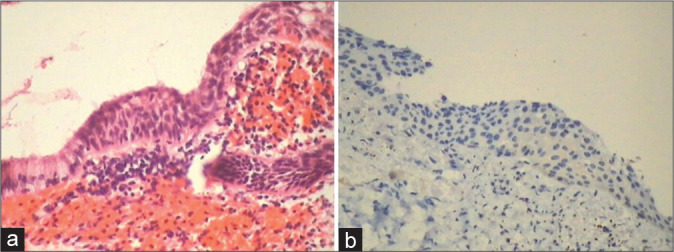

A positive p16 immunostain is of significance to differentiate between metaplasia and HSIL small cell type found high up in the canal

Morphologically atrophy also shows immature parabasal and basal cells with no differentiation. And stripping away of the fragile epithelial cells from the surface gives a false impression of HSIL, and therefore, surface maturation in AIM is not appreciated. Ki 67 is negative because overall proliferation is very low in atrophy [Figure 33a and b]

No nuclear pleomorphism or atypia is seen and there is no mitosis

p16 and Ki67 can help distinguish atrophy from HSIL. It has low Ki67 index and is negative for p16.

Figure 31:

Biopsy from a benign atrophic epithelium showing presence of hyperchromatic but generally uniform nuclei. The epithelium is thin with maintained polarity. The nuclear appearance is predominantly smudgy, hyperchromatic without recognizable nucleoli, and internal structure is no longer discernible. Colposcopic impression was HSIL.

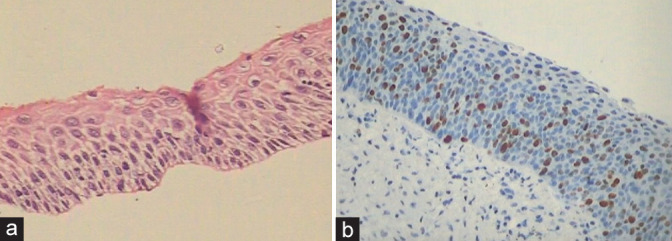

Figure 32:

(a and b) A negative p16 immunostain is of significance to differentiate between metaplasia and HSIL small cell type found high up in the canal.

Figure 33:

(a and b) Stripping away of fragile cells from the surface gives a false impression of HSIL. Ki 67 is negative because overall proliferative activity is very low in atrophy.

BIOMARKERS IN THE DIAGNOSIS OF SQUAMOUS LESIONS/ IMMUNOHISTOCHEMISTRY

Biomarkers are more helpful in identifying SILs that have a higher probability of progressing to HSIL or invasive carcinomas. It is important to remember that there is not a single biomarker on which a decision to proceed to LEEP or cone biopsy can be made. Biomarkers are less useful in sorting out minor abnormalities and more important for the confirmation of SIL that is most likely a HSIL.

p16INK4a and Ki-67 immunohistochemistry assist in the histological differential diagnosis of precursor lesions and the reactive and metaplastic epithelium[43]

Ki-67 indicates cellular multiplication and is a marker of cellular proliferation. Most LSIL will have an increased Ki-67 labeling index. Mib1 is a highly sensitive and specific marker for identifying LSIL and is helpful in verifying the diagnosis of equivocal cases. Mib 1 immunostaining as an adjunct test can be used to increase diagnostic accuracy of LSILs. Normally, only one or two parabasal layers take nuclear positivity for Ki-67 and rarely in the basal layer of the cervical squamous epithelium. A cluster of at least two stained nuclei in the upper two-thirds of the epithelial thickness is taken as an HPV-related lesion which is responsible for inducing cell cycle activity in these cells [Figure 34a-d]. [13] All Mib1-positive cases are generally HPV positive

Another marker is Pro-Ex-C, the distribution of this has been shown to be similar to Ki-67. It is less pronounced in benign proliferations and more conspicuous in many SILs with less background staining relative to p16

p16ink4, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor. Overexpression of p16 is linked with the continued expression of HPV oncogene E7 and acts as a reliable biomarker for HPV.[44,45] It is absent in normal squamous epithelium and inflammatory benign conditions

It can be increased in reactive conditions as well

It is strongly expressed in lesions associated with intermediate and HR HPV types in contrast to low-risk HPV infections

Approximately one-third of LSIL will show strong diffuse staining of the lower portion of the epithelium with p16INK4a. The presence of strong diffuse staining in the lower half of the epithelium indicates HPV and LSIL [Figure 35]. It is recommended to always correlate morphology with p16 staining

In immature metaplasia and atrophy, disparity in p16 and Ki-67 staining can occur. An explanatory note may be added taking into consideration the morphology, clinical, and colposcopic findings [Figure 36 a and b].

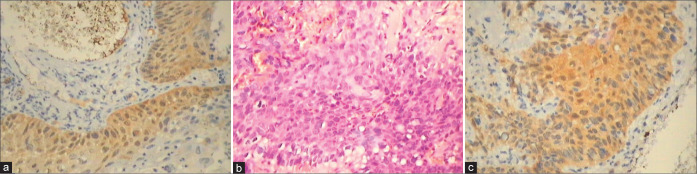

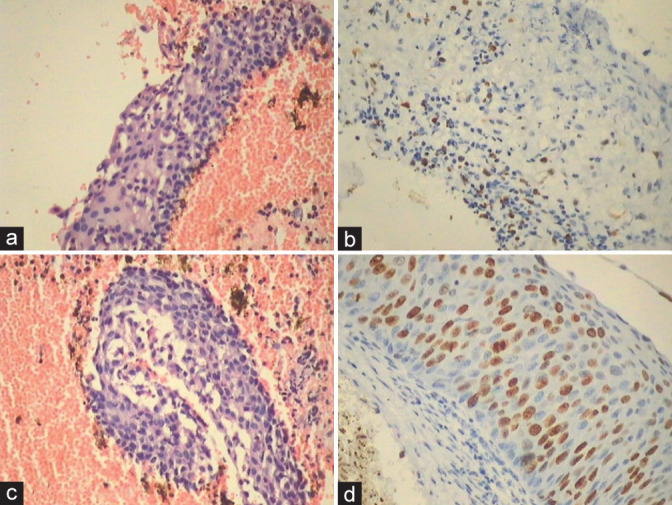

Figure 34:

(a-d) Metaplastic/reactive changes show the presence of Mib1 positive nuclei in intermediate layers along with focal positivity in AIM (a and b) as against continuous and quantitatively more positivity is seen in HSIL (c and d).

Figure 35:

(a-c) p16INK4a is a surrogate marker for HPV infection. In an uncertain or borderline condylomatous lesion, assessment of p16INK4a overexpression might be more specific for discriminating neoplastic groups of ASLs than for the detection of high-risk HPV types. p16 expression is linearly and significantly associated with the degree of dysplasia.

Figure 36:

(a and b) Ki-67 positivity may be discordant with morphology. (a) The spacing of the abnormal nuclei is more and there are no nuclear overlap creating doubts about LSIL or HSIL whereas Ki-67 is positive.

Acknowledgment

I acknowledge the help of Dr. Jasvinder Kaur Bhatia in the completion of this chapter.

Footnotes

How to cite this article: How to cite this article: Kamal M. Cervical pre-cancers: Biopsy and immunohistochemistry. CytoJournal 2022;19:38.

HTML of this article is available FREE at: https://dx.doi.org/10.25259/CMAS_03_13_2021

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In Alphabetic Order)

AIM - Atypical Immature Metaplasia

AL - Atypical lesions

ALTS - ASC-US /LSIL Triage Study

ASC - Atypical Squamous cells

ASC-US - Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance

CIN - Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia

CK – Cytokeratin

H&E - Hematoxylin & Eosin

HPV - Human papilloma virus

HPV DNA - Deoxyribonucleic acid

HR HPV - high risk Human papilloma virus

HSIL - High grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

IM - Immature Metaplasia

LAST - Lower Anogenital Squamous Terminology

LEEP - Loop Electric Excision Procedure

LSIL - Low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

MI - Mitotic index

N/C - Nuclear/Cytoplasmic ratio

SILs - Squamous intraepithelial lesions

TBS - The Bethesda System

References

- 1.St. Clair CM, Wright JD. Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia: History and Detection. The Global Library of Women's Medicine's Welfare of Women. 2009 doi: 10.3843/GLOWM.10227. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindell A. Carcinoma of the uterine cervix; incidence and influence of age; a statistical study. Acta Radiol Suppl. 1952;92:1–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, Bosch FX, Kummer JA, Shah KV, et al. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol. 1999;189:12–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199909)189:1<12::AID-PATH431>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richart RM. Natural history of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1967;10:748. doi: 10.1097/00003081-196712000-00002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marisa RN, Kenneth RL, Christopher PC. In: Diagnostic Histopathology of Tumors. 4th ed. Fletcher CD, editor. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, Saunders; 2013. Tumors of the female genital tract cervix; pp. 814–37. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alrajjal A, Pansare V, Choudhury MS, Khan MY, Shidham VB. Squamous intraepithelial lesions (SIL: LSIL, HSIL, ASCUS, ASC-H, LSIL-H) of uterine cervix and Bethesda system. Cytojournal. 2021;18:16. doi: 10.25259/Cytojournal_24_2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nuño T, García F. The lower anogenital squamous terminology project and its implications for clinical care. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2013;40:225–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herfs M, Yamamoto Y, Laury A, Wang X, Nucci MR, McLaughlin-Drubin ME, et al. A discrete population of squamocolumnar junction cells implicated in the pathogenesis of cervical cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:10516–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202684109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herfs M, Parra-Herran C, Howitt BE, Laury AR, Nucci MR, Feldman S, et al. Cervical squamocolumnar junction-specific markers define distinct, clinically relevant subsets of low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:1311–8. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182989ee2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldberg JR, Lamps LW, McKenney J, Myers JL. 11th ed. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Inc; 2018. Rosai and Ackerman's Surgical Pathology; pp. 1260–93. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mittal K, Demopoulos RI, Tata M. A comparison of proliferative activity and atypical mitoses in cervical condylomas with various HPV types. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1998;17:24–8. doi: 10.1097/00004347-199801000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mittal KR, Miller HK, Lowell DM. Koilocytosis preceding squamous cell carcinoma in situ of uterine cervix. Am J Clin Pathol. 1987;87:243–5. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/87.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mittal K, Palazzo J. Cervical condylomas show higher proliferation than do inflamed or metaplastic cervical squamous epithelium. Mod Pathol. 1998;11:780–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kersemaekers AM, Fleuren GJ, Kenter GG, Van den Broek LJ, Uljee SM, Hermans J, et al. Oncogene alterations in carcinomas of the uterine cervix: Overexpression of the epidermal growth factor receptor is associated with poor prognosis. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:577–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al Dallal H, Salih ZT. LSIL/CIN I. Available from: https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/cervixLSIL.html [Last accessed on 2022 May 18]

- 16.Wright TC, Kurman RJ, Ferenczy A. In: Blaustein's Pathology of the Female Genital Tract. Kurman RJ, editor. New York: Springer; 1994. Precancerous lesions of the cervix. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klaes R, Benner A, Friedrich T, Ridder R, Herrington S, Jenkins D, et al. p16INK4a immunohistochemistry improves interobserver agreement in the diagnosis of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:1389–99. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200211000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aoyama C, Liu P, Ostrzega N, Holschneider CH. Histologic and immunohistochemical characteristic of neoplastic and nonneoplastic subgroups of atypical squamous lesions of the uterine cervix. Am J Clin Pathol. 2005;123:699–706. doi: 10.1309/FB900YXTF7D2HE99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cabibi D, Giovannelli M, Tripodo C, Ammatuna P, Aragona F, Alletti TG. Histological features and ki-67 index in cervical atypical lesions. Am J Infect Dis. 2008;4:193–9. doi: 10.3844/ajidsp.2008.193.199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geng L, Connolly DC, Isacson C, Ronnett BM, Cho KR. Atypical immature metaplasia (AIM) of the cervix: Is it related to high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL)? Hum Pathol. 1999;30:345–51. doi: 10.1016/S0046-8177(99)90015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weir MM, Bell DA, Young RH. Transitional cell metaplasia of the uterine cervix and vagina: An underrecognized lesion that may be confused with high-grade dysplasia. A report of 59 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:510–7. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199705000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park JJ, Genest DR, Sun D, Crum CP. Atypical immature metaplastic-like proliferations of the cervix: Diagnostic reproducibility and viral (HPV) correlates. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:1161–5. doi: 10.1016/S0046-8177(99)90032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ng WK, Cheung LK, Li AS, Cheung FM, Chow JC. Transitional cell metaplasia of the uterine cervix is related to human papillomavirus: Molecular analysis in seven patients with cytohistologic correlation. Cancer. 2002;96:250–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kruse AJ, Baak JP, Helliesen T, Kjellevold KH, Bol MG, Janssen EA. Evaluation of MIB-1-positive cell clusters as a diagnostic marker for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:1501–7. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200211000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCluggage WG, Buhidma M, Tang L, Maxwell P, Bharucha H. Monoclonal antibody MIB1 in the assessment of cervical squamous intraepithelial lesions. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1996;15:131–6. doi: 10.1097/00004347-199604000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Basu P, Kamal M, Ray C, Bhat D, Ghosh I, Mittal S, et al. Interobserver agreement in the reporting of cervical biopsy specimens obtained from women screened by visual inspection with acetic acid and hybrid capture 2. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2013;32:509–15. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0b013e31827b26b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Creagh T, Bridger JE, Kupek E, Fish DE, Martin-Bates E, Wilkins MJ. Pathologist variation in reporting cervical borderline epithelial abnormalities and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:59–60. doi: 10.1136/jcp.48.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCluggage WG, Bharucha H, Caughley LM, Date A, Hamilton PW, Thornton CM, et al. Interobserver variation in the reporting of cervical colposcopic biopsy specimens: Comparison of grading systems. J Clin Pathol. 1996;49:833–5. doi: 10.1136/jcp.49.10.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pirog EC, Baergen RN, Soslow RA, Tam D, DeMattia AE, Chen YT, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of cervical low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions is improved with MIB-1 immunostaining. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:70–5. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200201000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma M, Arunamata A, Peng LF, Wise-Faberowski L, Hanley FL, McElhinney DB. Longevity of large aortic allograft conduits in tetralogy with major aortopulmonary collaterals. Ann Thorac Surg. 2021;112:1501–7. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2021.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.ASCUS/LSIL Study (ALTS) Group Human papillomavirus testing for triage of women with cytologic evidence of low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions: Baseline data from a randomized trial. The atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance/low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions triage study (ALTS) group. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:397–402. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.5.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arends MJ, Buckley CH, Wells M. Aetiology, pathogenesis, and pathology of cervical neoplasia. J Clin Pathol. 1998;51:96–103. doi: 10.1136/jcp.51.2.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jovanovic AS, McLachlin CM, Shen L, Welch WR, Crum CP. Postmenopausal squamous atypia: A spectrum including “pseudo-koilocytosis”. Mod Pathol. 1995;8:408–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zeng Z, Del PG, Cohen JM, Mittal K. MIB-1 expression in cervical Papanicolaou tests correlates with dysplasia in subsequent cervical biopsies. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2002;10:15–9. doi: 10.1097/00022744-200203000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Felix JC, Wright TC. In: Modern Surgical Pathology. Weidner N, Cote RJ, Suster S, Weiss LM, editors. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2003. Cervix; pp. 1299–305. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wentzensen N, Walker JL, Gold MA, Smith KM, Zuna RE, Mathews C, et al. Multiple biopsies and detection of cervical cancer precursors at colposcopy. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:83–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.9948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mills GC, Alperin JB, Trimmer KB. Studies on variant glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenases: G6PD Fort Worth. Biochem Med. 1975;13:264–75. doi: 10.1016/0006-2944(75)90084-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abadi MA, Ho GY, Burk RD, Romney SL, Kadish AS. Stringent criteria for histological diagnosis of koilocytosis fail to eliminate overdiagnosis of human papillomavirus infection and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 1. Hum Pathol. 1998;29:54–9. doi: 10.1016/S0046-8177(98)90390-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Franquemont DW, Ward BE, Anderson WA, Crum CP. Prediction of ''high-risk'' cervical papillomavirus infection by biopsy morphology. Am J Clin Pathol. 1989;92:577–82. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/92.5.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mittal KR, Chan W, Demopoulos RL. Sensitivity and specificity of various morphological features of cervical condylomas. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1990;114:1038–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ward BE, Burkett BA, Peterson C, Nuckols ML, Brennan C, Birch LM, et al. Cytological correlates of cervical papillomavirus infection. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1990;9:297–305. doi: 10.1097/00004347-199010000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duggan MA. Cytologic and histologic diagnosis and significance of controversial squamous lesions of the uterine cervix. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:252–60. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Keating JT, Cviko A, Riethdorf S, Riethdorf L, Quade BJ, Sun D, et al. Ki-67 (MIB-1), Cyclin E, and P16 (INK4a) are complementary surrogate biomarkers for human papilloma virus-related cervical neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:884–91. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200107000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Klaes R, Friedrich T, Spitkovsky D, Ridder R, Rudy W, Petry U, et al. Overexpression of p16(INK4A) as a specific marker for dysplastic and neoplastic epithelial cells of the cervix uteri. Int J Cancer. 2001;92:276–84. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Regauer S, Reich O. CK17 and p16 expression patterns distinguish (atypical) immature squamous metaplasia from high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN III) Histopathology. 2007;50:629–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02652.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]