Abstract

An increasing number of patients with multiple brain metastases are being treated with stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS). Manually identifying and contouring all metastatic lesions is difficult and time-consuming, and a potential source of variability. Hence, we developed a 3D deep learning approach for segmenting brain metastases on MR and CT images. 511 patients treated with SRS were retrospectively identified for this study. Prior to radiotherapy, the patients were imaged with 3D T1 spoiled-gradient MR post-Gd (T1+C) and contrast-enhanced CT (CECT), which were co-registered by a treatment planner. The gross tumor volume contours, authored by the attending radiation oncologist, were taken as the ground truth. There were 3 ± 4 metastases per patient, with volume up to 57 mL. We produced a multi-stage model that automatically performs brain extraction, followed by detection and segmentation of brain metastases using co-registered T1+C and CECT. Augmented data from 80% of these patients were used to train modified 3D V-Net convolutional neural networks for this task. We combined a normalized boundary loss function with soft Dice loss to improve the model optimization, and employed gradient accumulation to stabilize the training. The average Dice similarity coefficient (DSC) for brain extraction was 0.975 ± 0.002 (95% CI). The detection sensitivity per metastasis was 90% (329/367), with moderate dependence on metastasis size. Averaged across 102 test patients, our approach had metastasis detection sensitivity 95 ± 3%, 2.4 ± 0.5 false positives, DSC of 0.76 ± 0.03, and 95th-percentile Hausdorff distance of 2.5 ± 0.3 mm (95% CIs). The volumes of automatic and manual segmentations were strongly correlated for metastases of volume up to 20 mL (r = 0.97, p < 0.001). This work expounds a fully 3D deep learning approach capable of automatically detecting and segmenting brain metastases using co-registered T1+C and CECT.

Introduction

Brain metastases are an increasingly common neurological complication for many different types of primary cancers, with an incidence rate greater than 20% [1] [2] [3]. Whole-brain radiation therapy was standard treatment for brain metastases since the 1970s [4], but can adversely affect the patient’s cognitive function and quality of life [5]. In more recent years, stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) with highly conformal dose distributions has become the standard-of-care for many more patients [6] [7]. These treatments deliver a high dose to the targeted lesions in a small number of patient visits while sparing more healthy brain tissue. For treatment planning, the physician must manually contour the multitude of presenting lesions on co-registered, three-dimensional MR and CT images. This process is labor-intensive and prone to significant variability among physicians [8]. Furthermore, patients may now receive several courses of radiotherapy for brain metastases, which may introduce radiographic changes and make identifying lesions more difficult. An automatic and robust system for detecting and contouring brain metastases would facilitate more precise and efficient treatment delivery in the radiotherapy clinic.

While much effort has been put into applying machine learning to gliomas, brain metastases tend to be smaller, less heterogeneous, and less contrast-enhancing on imaging, which poses a harder problem for automatic segmentation. Before striving to segment a metastasis accurately, even detecting it is not guaranteed. Several approaches for automatic brain metastasis detection/segmentation have been investigated. Early methods using template matching on MRI were limited by small patient sample sizes and could only achieve moderate detection sensitivity with high false positive rates. Ambrosini et al. [9] reported 90% sensitivity with 0.22 false positives per slice per patient on a test dataset of 22 patients; Pérez-Ramírez et al. [10] reported 88% sensitivity and 6 false positives per patient on a test dataset of 22 patients. With the rise of deep learning [11] and its growing presence in the medical imaging literature, more recent works have studied the applicability of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to this problem. Several works studied the segmentation and detection performance of 2D or 3D CNNs with multimodal MR inputs including 3D T1+C [8] [12] [13] [14], while others applied similar techniques to 3D T1+C alone [15] [16] [17] [18]. These studies are generally characterized by imperfect segmentation quality, poor sensitivity for smaller metastases, and multiple false positive detections per patient.

Although Zhou et al. [19] and others have argued against the clinical applicability of models with multimodal inputs, brain metastasis cases frequently arise in clinical practice where 3D T1+C is not as effective. Cystic or necrotic lesions may appear uniformly hypointense or rim-enhancing on T1+C [20]. Meanwhile, clinical experiences have shown poor gadolinium contrast uptake for patients who were treated with angiogenesis inhibitors e.g. bevacizumab in weeks prior to brain MR imaging [21] [22]. Other helpful acquisitions in these situations include T2 FLAIR MR and contrast-enhanced CT (CECT) imaging. Charron et al. [12] performed an ablative test on the inclusion of 2D T2 FLAIR imaging in their 3D deep learning model, showing only modest improvement in detection positive-predictive-value (PPV) and segmentation quality. Since brain metastases can be smaller than 2D acquisition slice spacing, these alternative acquisitions are most helpful in 3D. One recent deep learning detection model using 3D CECT alone [23] achieved metastasis sensitivity close to 90% but suffered from a high false positive rate.

We made several novel contributions to this topic. First, most of the previous related work makes use of skull-stripping software to remove non-brain tissues (Brain Extraction Tool [24] or Freesurfer [25]), but this may fail for patients with metastases. We produced a deep learning-based brain extraction model trained specifically on patients with metastases as a part of a multi-stage approach. Additionally, we exhibit a multi-modality metastasis segmentation approach using T1+C and CECT in a 3D CNN, which we show is more accurate than using T1+C only. We were well-equipped for this task, since 3D CECT acquisition is standard-of-care for VMAT-based SRS treatment planning at our institution. Lastly, we explored how to improve the training strategies for a 3D CNN applied to brain metastases, and employed novel techniques such as large-scale data augmentation, gradient accumulation, and scheduled boundary loss optimization.

Materials and Methods

Patient Dataset

511 patients were identified who underwent stereotactic radiosurgery for brain metastases between 2016 and 2019. This retrospective study was approved by our Institutional Review Board and written consent was waived. None of these patients underwent surgical resection, but some had received prior brain radiation. The primary cancer sites of patients were: 222 lung (43%), 87 breast (17%), 61 melanoma (12%), 30 renal (6%) and 111 elsewhere (22%).

All patients received an intravenous gadolinium contrast agent before being imaged with a 3D spoiled-gradient MR sequence. The majority (87%) were imaged with GE BRAVO, an ultrafast spoiled-gradient sequence with inversion recovery [26]. All but one of the remaining patients were imaged with Philips T1-FFE, a sequence functionally equivalent to GE SPGR. The remaining one patient was imaged with Siemens MP-RAGE. We treated these sequences as clinically interchangeable and did not distinguish among them. The patients were given iodine contrast and immobilized and imaged on a CT simulator for radiation treatment planning. The CT and MR were acquired within 3 days or less for 70% of patients; the time difference was greater than two weeks for ten patients. The details of the MR and CT scanners and acquisitions may be found in Table 1. Eight patients received at least one injection of bevacizumab less than 30 days prior to MR imaging.

Table 1:

CT and MR scanners used. Standard deviation is quoted where settings were non-uniform.

| Manufacturer | CT Scanner |

Patients | Pixel spacing [mm] |

Slice spacing [mm] |

Kilovoltage peak |

mA-s | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GE Medical Systems | Discovery ST | 83 | 0.77 ± 0.12 | 1.2 | 120 | 218 ± 43 | |||

| Philips Healthcare | Brilliance Big Bore | 428 | 0.78 ± 0.16 | 1.0 | 120 | 569 ± 47 | |||

| Manufacturer | MR Scanner |

Patients | Pixel spacing [mm] |

Slice spacing [mm] |

Magnetic field [T] |

Repetition time [ms] |

Echo time [ms] |

Inversion time [ms] |

Flip angle [deg] |

| GE Medical Systems | Discovery MR750w | 236 | 0.95 ± 0.07 | 1.05 ± 0.21 | 3 | 6.8 ± 0.6 | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 450 | 12 |

| Optima MR450w | 84 | 0.96 ± 0.03 | 1.06 ± 0.44 | 1.5 | 8.2 ± 0.3 | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 450 | 12 | |

| Signa PET/MR | 62 | 0.97 ± 0.04 | 1.00 | 3 | 7.5 ± 0.9 | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 450 | 12 | |

| Signa HDxt | 31 | 0.94 ± 0.08 | 1.12 ± 0.10 | 1.5 | 9.4 ± 0.3 | 3.7 ± 0.1 | 450 | 13 | |

| Signa Architect | 19 | 0.98 ± 0.03 | 1.00 | 3 | 7.0 ± 0.9 | 2.6 ± 0.4 | 450 | 12 | |

| Signa Artist | 11 | 0.96 ± 0.03 | 1.00 | 1.5 | 8.5 ± 0.2 | 3.2 ± 0.1 | 450 | 12 | |

| Signa Excite | 1 | 0.94 | 1.50 | 1.5 | 22 | 3.0 | - | 30 | |

| Philips Healthcare | Ingenia | 66 | 0.89 ± 0.03 | 1.98 ± 0.12 | 3 | 31 | 2.0 | - | 30 |

| Siemens | Aera | 1 | 0.45 | 1.00 | 1.5 | 2000 | 4.5 | 450 | 15 |

The ground truths for the study were the radiotherapy treatment planning contours. The gross tumor volumes (GTVs) were provided by the attending radiation oncologist. The brain contour was produced using an atlas method in MIM 6 [27], then manually corrected by the treatment planner. Around 10% of patients had additional previously treated GTVs or small GTVs that were observed but not treated; those contours were provided by a radiation oncologist resident. 20% of patients (102) were randomly set aside as testing data, and the other 80% (402) were evenly divided into five cross-validation subgroups and used to train the final models.

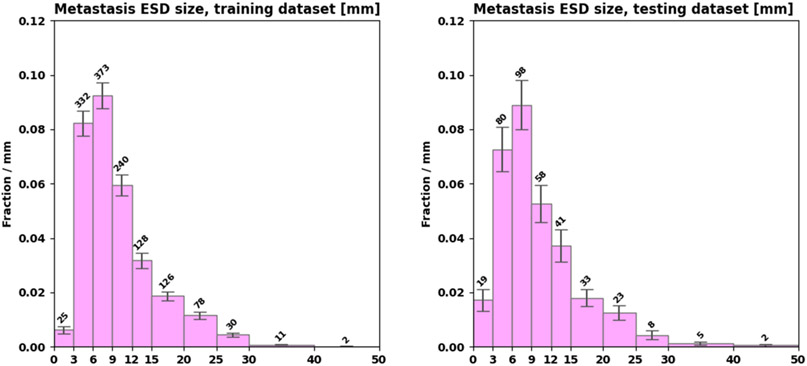

The testing dataset contained two of the patients treated with bevacizumab. The training dataset had a total of 1345 metastases with 3 ± 4 per patient (median 2, IQR [1,4]). The testing dataset had a total of 367 metastases with 4 ± 5 per patient (median 2, IQR [1,4.8]). Figure 1 shows distributions of metastasis size in the training and testing datasets.

Figure 1:

Distributions of metastasis size in the training (left) and testing (right) datasets.

Image Preprocessing

The MR and CT images were processed to remove outlier intensities and provide consistent input data to the models. The CT was linearly resampled to 1 mm isotropic voxel spacing and CT numbers were windowed between 0 and 100 Hounsfield units. The ground truth data was rasterized from RTSTRUCT DICOM files into (1 mm pixel spacing) × (CT native slice spacing) using Plastimatch [28], then resampled to the target slice spacing using nearest-neighbor interpolation. After applying the N4 bias field correction [29], the MR was resampled with linear interpolation into the final CT geometry using the rigid registration parameters obtained by the treatment planner in MIM Maestro. Lastly, the image foreground intensity histograms were statistically normalized to zero mean with variance of unity.

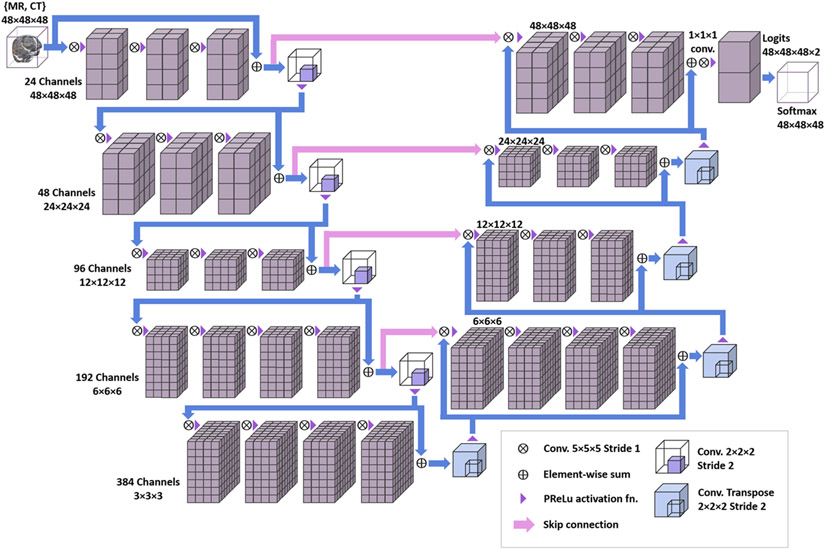

Deep Convolutional Neural Network Algorithm

A modified version of the V-Net 3D CNN algorithm was used [30]. See Figure 2 for a schematic. To analyze both T1+C and CECT, they were provided as a 3D image with two intensity channels. Compared to the popular U-Net architecture [31], the V-Net aims to learn a residual function in each stride-1 convolutional block, which improves the convergence speed and training stability. Skip connections pass forward the features extracted in the early stages of the CNN to the later stages, which amalgamates different levels of contextual detail and improves the prediction. The downsampling and upsampling convolutions are performed with stride-2 and 2×2×2 kernel, and the parametric rectified linear unit (PReLu) is used as a nonlinear activation function throughout. Batch normalization is applied after each convolutional layer. Convolution weights are initialized using Xavier initialization [32]. We made several minor modifications to tailor the V-Net for our specific applications. For segmenting metastases, to enhance the detection of small objects: the input volume was reduced to (48 mm)3; the number of feature channels produced by the input layer was increased to 24; and the number of stride-1 convolutions in each tier was increased to 3, 3, 3, 3, and 4 ordered by increasing downsampling. For extracting the brain: the input volume was much more oblate (256 × 256 × 32 mm3); the input layer produced 16 features; and the number of stride-1 convolutions per tier was 2, 2, 2, 2, and 3. The models were implemented in Python with Tensorflow [33] and trained on the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) High Performance Computing Cluster using multiple NVIDIA GTX 2080 Ti graphical processing units (GPUs) with 10 GB of memory (VRAM).

Figure 2:

Schematic of the modified V-Net 3D convolutional neural network.

Data Augmentation

One challenge in applying deep learning techniques to medical imaging is that the datasets are typically quite small compared to other applications. We employed large-scale data augmentation to increase the amount of training data and improve the model generalizability. Prior to training, fifty augmented versions of each patient in the training dataset were produced using the following CPU-intensive transformations:

T1+C MR image intensity histogram matching to another random patient [34]

Random B-spline free-form deformation (103 field points, displacement ≤ 1 cm) [35] [36]

Random 3D rotation of whole image, up to 20° [37]

For random rotations, the direction and amount of rotation were randomly chosen from uniform distributions, and the center of rotation was the centroid of a randomly-chosen metastasis label. During the development of our augmentation strategy, the output was visually inspected, and metastases which were subject to large deformations or rotations were checked to be recognizable and correctly labeled. Augmented patients with zero ground truth voxels were discarded and repeated. All 20,450 augmented patients were written to an IBM General Parallel File System [38] for subsequent distributed reading by multiple training processes. During training, these images were further augmented with random Gaussian noise (σ = 5 × 10−3) and random flips.

Loss Function

The training data exhibited extreme voxel class imbalance, with fewer than 0.1% of voxels containing metastasis ground truth. The cross-entropy loss function is not ideal in this scenario, so the soft Dice loss function [30] was used instead:

| (1) |

where is the lesion probability s computed from network parameters at spatial voxel q, and g(q) is the ground truth (1 or 0). It is “soft” by adding ϵ, a small number e.g. 10−5, so that approaches zero as both sums over q approach zero. This loss function is similar to the Dice coefficient, but provides smooth gradients for the network parameter optimization.

Alongside the soft Dice loss, we used a modified version of the boundary loss function, as described by Kervadec et al., which emphasizes accurate extraction of the truth surface [39]. Consider the signed distance map φG (q), which is the distance from voxel q to the closest ground truth voxel (and negative inside). The boundary loss is then

| (2) |

Applying gradient descent using penalizes positive predictions outside the ground truth surface, and negative predictions inside that surface. However, the raw quantity is badly behaved—it can be negative, carries a dimension of length, and can grow very large depending on the sizes of the ground truth and input volumes. Therefore, we conceived of the so-called normalized boundary loss function based on the best-case and worst-case scenarios where respectively:

| (3) |

| (4) |

It follows that . Kervadec et al. [39] found that training with only a boundary loss function can lead to a negative prediction everywhere. As originally recommended, we constructed a total loss function in which the relative contribution of the normalized boundary loss was scheduled to increase by γ after each training epoch t:

| (5) |

We refer to this as the Dice-Boundary loss. Besides these loss functions, we also conducted preliminary experiments with other loss functions such as Tversky index loss [40] and weighted cross-entropy, which produced weaker results. The model for extracting the brain was optimized using a composite version of the Dice-Boundary loss function, considering the union of multiple input volumes . Since detection was not a concern, this served to maximize the segmentation performance.

Parameter Optimization

We used adaptive moment optimization (ADAM) to update the network parameters during training according to the parameter gradients [41]. The following ADAM hyperparameters were used: α = 0.01, β1 = 0.9, β2 = 0.999, and ϵ = 10−3 (distinct from ϵ in Eqn. 1). To train the models, input volumes were randomly sampled from patient images, with 50% of volumes required to contain some GTV voxels for the metastasis model. One training epoch was defined as when a random volume was sampled from fifty augmented versions of all the training patients. Early stopping was employed in order to prevent model overfitting and control the maximum value of γt. The brain extraction models were trained for 10 epochs with γ=1%/epoch. The metastasis models were trained for 20 epochs with several values of γ. Each model took 2 to 3 days to train. Five-fold cross validation in the training dataset was used to develop our training strategies.

Model Evaluation

To evaluate the model on a patient, the entire image volume was scanned with a stride of 8 mm using several thousand overlapping input volumes, and the overlapping predictions were averaged to produce a probability map. This process took one to two minutes per patient using a GPU. To obtain binary masks, a probability threshold was applied to this probability map, followed by a connected-component (CC) analysis. The extracted brain contour was taken as the largest CC after applying a 50% probability threshold. For metastases, as we will discuss below, the choice of probability threshold is nontrivial. All predicted CCs of volume greater than 6 mL were considered as predicted metastases. GTVs with any overlap with a predicted metastasis were considered to be successfully detected.

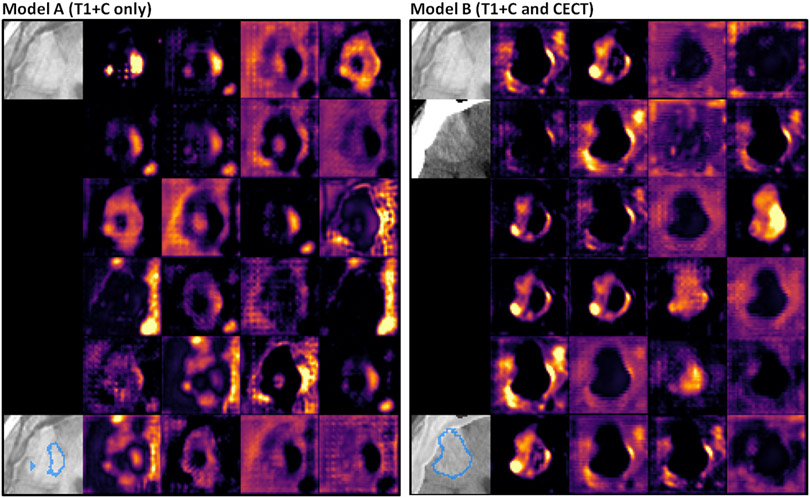

We trained several metastasis models using the same augmented data and training conditions, while varying the boundary loss contribution (γ=0%/epoch, 1%/epoch, …) and the image inputs (T1+C alone versus T1+C with CECT). From cross-validation results, we chose the best T1+C-only model (Model A) and the best model with T1+C and CECT (Model B). To examine the differences between the models qualitatively, we visually compared feature maps of the network activations just before the final 1×1×1 convolutional layer. For visualization purposes, each of the 24 feature maps were smoothed with a uniform 2×2×2 convolution filter to remove artifacts from the preceding convolutional transpose layer.

Gradient Accumulation

Even with several gigabytes of GPU VRAM, this 3D CNN model is very cumbersome in memory, in part due to batch-normalization layers, so it cannot learn simultaneously from a sizeable minibatch of input volumes. Since it is important to include both positive and negative examples in training, we found that training with a small minibatch size was unstable without an extremely small learning rate. In order to increase the minibatch size without sacrificing model complexity, we developed a gradient accumulation procedure as follows. The average of the specific Dice-Boundary loss function over a minibatch of N volumes Qi , is . The gradient of this quantity with respect to the network parameters is:

| (6) |

For each individual input volume passed to the GPU, gradient terms were obtained via backpropagation and the corresponding sum vectors were accumulated in VRAM. Then, the average gradient was applied using ADAM after a minibatch of N volumes was processed. The book-keeping for each vector term occupies additional VRAM proportional to the number of trainable parameters, but constant with N. Using this technique, the CNN models were trained with a minibatch size of N = 100.

Statistical Analysis

The quality of the brain extraction component of the ensemble model was evaluated with patient averages of the 95th-percentile Hausdorff distance (HD95) and the Dice similarity coefficient. The metastasis models’ detection performance was compared on the basis of detection sensitivity per metastasis, as well as patient-averaged quantities of detection sensitivity, false positives, and positive predictive value (PPV). Their segmentation performance was compared with patient Dice coefficient, and, for detected metastases, the specific HD95 and Dice coefficient. All HD95 and Dice coefficients were computed using the Insight Toolkit v4 [42]. Sensitivity confidence intervals were estimated using 95%-confidence Clopper-Pearson intervals. Patient-averaged quantities were compared using a two-tailed paired difference t-test. Metastasis detection sensitivities were compared using McNemar’s test [43].

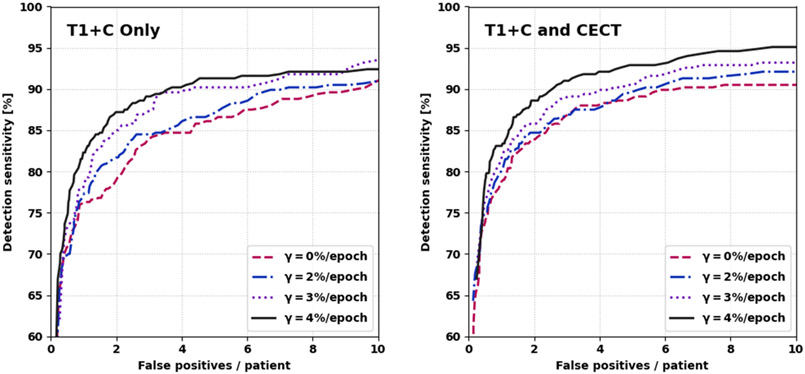

For metastasis detection performance, we performed ablative experiments to assess the incremental impact of including CECT and using the normalized boundary loss. We studied the relationship between detection sensitivity and the false positive rate using free-response receiver operating characteristic (FROC) curves; the metastasis detection threshold was varied and the corresponding sensitivities and false positive rates were computed. FROC curves were compared for different contributions of boundary loss and for different model inputs (T1+C with CECT versus without CECT).

For the purpose of a differential analysis in size, the manual and predicted metastasis sizes were defined1 as the equivalent sphere diameter (ESD) based on voxel volume (), consistent with Rudie et al. [8]. The metastasis detection sensitivity, HD95, and Dice coefficient were found to depend on metastasis size, and were stratified in size bins. For detected metastases, we evaluated differences between the manual and predicted volume with Bland-Altman analysis to facilitate comparison with Zhou et al. [19]. The correlation between manual versus predicted volume was quantified using the Pearson correlation coefficient and the Lin concordance correlation coefficient for lesions up to 20 mL volume, excluding a small number of outliers. Moreover, we performed a linear regression to quantify the relationship between these two volume measurements.

Results

Brain Extraction

Using T1+C alone, the brain extraction model component had excellent segmentation performance, and was robust in the presence of enhancing metastases and edema. The average Dice coefficient was 0.975 ± 0.002 with median 0.974 and IQR [0.973, 0.979]; the average HD95 was 9.0 ± 0.7 mm with median 8.1 and IQR [7.0, 9.9] (95% CIs). Adding CECT input produced a small but significant improvement, with average Dice coefficient of 0.985 ± 0.001 and average HD95 of 7.6 ± 0.6 mm (both p < 0.001). The distributions of Dice coefficient and HD95 are shown in Figure 3. The T1+C-only brain model was used as the skull-stripping method for comparing all metastasis models on an equal footing.

Figure 3:

Performance of brain extraction on testing data. The last HD95 bin contains overflow values.

Metastasis Detection

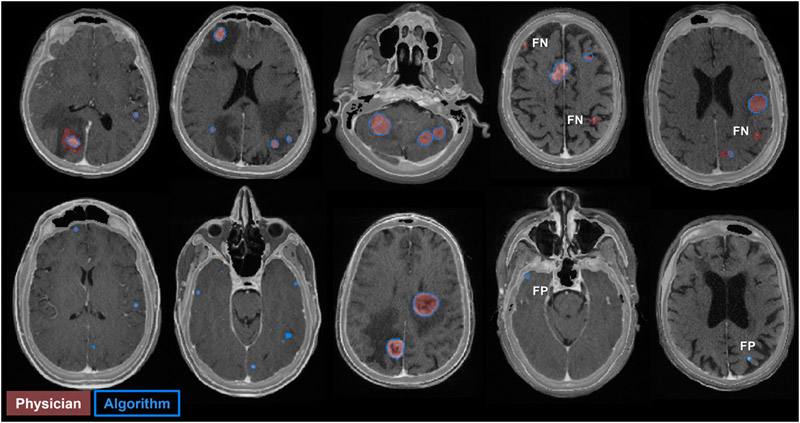

Here, we analyze the detection performance of the multiple metastasis models. In Figure 4, we show the FROC curves for different combinations of inputs and γ-values (the rate at which the boundary loss enters into the equation). Models with higher γ and CECT input generally showed better detection performance. However, we omitted models trained with γ=5%/epoch, which became unstable as γt → 100%. From these FROC curves, we chose two representative models. Model A, the best model with only T1+C input (γ=4%/epoch), had overall detection sensitivity 90% [86%, 93%], 3.4 ± 0.5 false positives per patient, and PPV 45 ± 5% at a probability threshold of 44% (95% CIs). Model B, the best model with T1+C and CECT input (γ=4%/epoch), had overall detection sensitivity 90% [86%, 93%], 2.4 ± 0.5 false positives per patient, and PPV 55 ± 5% at a probability threshold of 52% (95% CIs). Model A detected 11 metastases that model B did not detect, and vice versa. By McNemar’s test, the two models offer indistinguishable sensitivity at the chosen probability thresholds (p > 0.8). Meanwhile, the number of false positives per patient was significantly lower for Model B versus A, by the paired two-sample t-test (p < 0.001). A few examples of false positives and false negatives from Model B are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 4:

Free-response receiver operating characteristic curves for various values of the boundary loss scheduling parameter, γ. Left: only T1+C input. Right: T1+C and CECT input. γ=4%/epoch was the most performant value.

Figure 5:

Model B predictions on patients in the testing dataset. Each image is an axial slice of blended T1+C and CECT. The physician metastasis GTV contours are shaded in red and the model predictions are outlined in blue. Examples of false positives (FP) and false negatives (FN) are shown.

Metastasis Segmentation

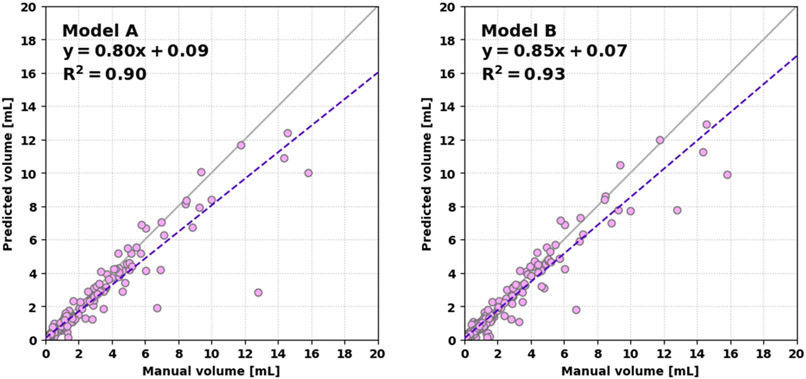

Next, we describe the overall segmentation performance. The patient-averaged Dice coefficients were: Model A, 0.71 ± 0.04 (med. 0.77, IQR [0.64, 0.87]); Model B, 0.76 ± 0.04 (med. 0.80, IQR [0.68, 0.88]) respectively (95% CIs). These were significantly different (p < 0.001). The average HD95s per metastasis were: Model A, 2.6 ± 0.3 mm; Model B, 2.5 ± 0.3 mm (95% CIs). The average Dice coefficients per metastasis were: Model A, 0.76 ± 0.02; Model B, 0.76 ± 0.02 (95% CIs). A scatter plot of the predicted versus manual volumes of detected lesions are shown in Figure 6. Using Model B, the linear regression was more consistent with a linear 1:1 relationship. Considering volumes up to 20 mL, the Pearson correlation coefficients between the predicted and manual volumes were 0.95 and 0.97 for Models A and B, respectively (each p < 0.001). The Lin concordance correlation coefficients were 0.93 and 0.96. For all models, the volume of the smallest metastases was systematically overestimated, while several larger outliers were significantly underestimated. This is illustrated well in the Bland-Altman analysis—see Figure 7. Importantly, the segmentation performance for the smallest metastases was not improved by more aggressive boundary loss scheduling with higher γ.

Figure 6:

Linear regression of the predicted volume versus manual volume for Model A (left) and Model B (right). Model B more closely follows a 1:1 relationship.

Figure 7:

Bland-Altman analysis plots for Model A (left) and Model B (right). The difference is the predicted volume minus the manual volume. Model B is slightly more consistent with 0 difference.

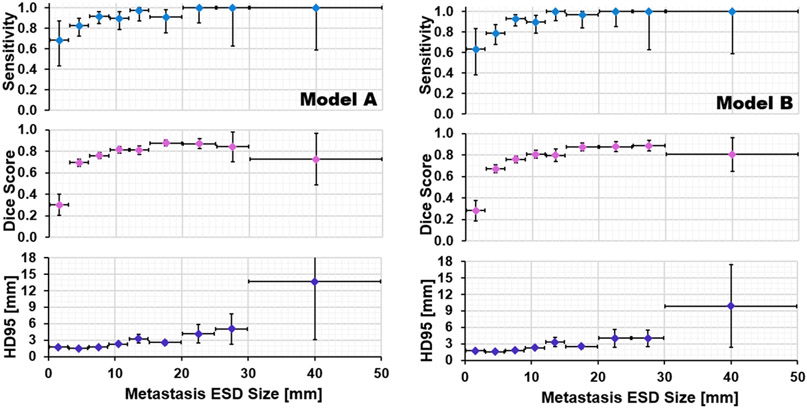

Differential Size Analysis

The metastasis detection sensitivity, average Dice coefficient, and average HD95 are shown as a function of metastasis ESD size for Models A and B in Figure 8. For very small metastases (ESD size < 3 mm), Model A and Model B reported detection sensitivities of 68% [43%, 87%] and 63% [38%, 84%] respectively. For metastases smaller than 6 mm, Model A had sensitivity 80% [71%, 87%] and model B had sensitivity 76% [66%, 84%]. For metastases larger than 6 mm, Model A had sensitivity 93% [89%, 96%] and Model B had sensitivity 95% [92%, 97%]. Despite the promising sensitivity, the Dice coefficient was very poor for sizes below 3 mm due to the aforementioned overestimation of volume. The proportion of testing dataset metastases detected by both models was 318 out of 367, of which 38 had ESD size 20 mm or greater. For these large metastases, Model B’s segmentation performance was stronger, with Dice coefficient of 0.87 versus 0.84 (p = 0.06) and HD95 of 5.1 versus 6.1 mm (p = 0.04).

Figure 8:

Performance as a function of metastasis size for Model A (left) and Model B (right).

Case Study

We visually inspected the model output and feature activations, and we observed qualitative differences between the models for some patients. A case study of a patient who received bevacizumab several days prior to T1+C imaging is shown in Figure 9. The pictured metastasis (volume 12.8 mL, ESD size 29 mm) is poorly contrasted on T1+C, but visible on CECT. It was successfully detected by both Models A and B. As shown in the figure, this metastasis was poorly segmented by Model A (Dice coefficient 0.37, Hausdorff distance 14.2 mm) but more accurately segmented by Model B (Dice coefficient 0.75, Hausdorff distance 8.1 mm). Moreover, Model B showed much sharper feature contrast at the edges of the metastasis. This is an example where multichannel input provides superior auto-segmentation performance and is clinically necessary.

Figure 9:

Case study of a patient with ovarian cancer and brain metastasis, age 75, treated with 15 mg/kg bevacizumab 11 days prior to MR acquisition. Left: Model A. Right: Model B. Each panel shows axial slices of the input images, the model prediction, and the 24 feature activations just before the last 1×1×1 convolutional layer. Model B’s prediction is overlaid on blended T1+C and CECT.

Discussion

In this work, we modified a 3D CNN with residual learning and applied it in a multi-stage model which automatically extracts the brain structure and detecting and contouring brain metastases. We undertook a large-scale data augmentation scheme using distributed computing to mitigate the limited size of our training dataset. We showed through ablative testing that the combination of T1+C and CECT images is helpful for metastasis detection and segmentation on a sample of patients at our institution. Our novel approach to boundary loss scheduling was not previously explored for brain metastases and was shown to provide a benefit in our patient sample. Our gradient accumulation strategy is applicable to any variety of memory-intensive 3D CNN architecture in this topic.

We compare our results against other published works on brain metastasis segmentation. We provide an updated version of the comparison table formulated by Zhou et al. [19] which includes our results and the recent works of Amemiya et al. [23] and Rudie et al. [8]. Before continuing, it is crucial to note that the power of any comparison below is limited by the lack of a common dataset. Each work up to this point is based on a separate dataset with a different distribution of metastasis size, primary cancer, scanner models, and scanner settings. Furthermore, even comparisons of a differential size analysis are limited by the varying ways that metastasis size is defined and the physicians’ contouring habits.

Our work showed a patient-averaged detection sensitivity of 95% for either Model A or B, which is relatively high. Unlike previous work, we achieved moderate detection performance for a limited sample of small metastases. Since we are the first to study the combination of CECT and T1+C, in order to compare approaches on an equal footing, we consider only T1+C input (Model A). In comparison with Zhou et al., our sensitivity is slightly higher (95% vs. 88%), we produced the same number of false positives per patient (3 vs. 3), and our PPV was slightly worse (45% vs. 58%) albeit large variances. For metastases under 6 mm, we report sensitivity 80% [71%, 87%] which is higher than their 68% [63%, 73%]. Meanwhile, compared to Rudie et al., we report much higher sensitivity per metastasis (90% vs. 70%) at the expense of more false positives (4 vs. 0.4). For metastases under 3 mm, we report sensitivity 68% [43%, 87%] which is higher than their 15% [9%, 22%]. Some of this difference arises from the choice of probability threshold rather than the strength of the model. Referring to Figure 4, we could increase our probability threshold and produce similar results to Rudie et al. Operating Model A at a threshold of 96%, we report per-metastasis detection sensitivity of 71% [66%, 76%], 0.4 ± 0.1 false positives per patient, and sensitivity 32% [13%, 57%] for metastases under 3 mm (95% CIs), which is indistinguishable from their result. Bousabarah et al. chose a similarly stringent working point, but a further comparison is not statistically meaningful since uncertainties were not provided. In general, we were able to achieve higher patient sensitivity than the other works listed based on T1+C or multimodal MR, at the expense of a manageable number of false positives.

Our segmentation performance was comparable to other works. For both Models A and B, the linear regression for predicted versus manual volume was slightly less consistent with a 1:1 relationship than Zhou et al. (slope 0.94, intercept 0.01). Considering the Pearson correlation and Lin concordance correlation coefficients for Model A (PCC: 0.95, LCCC: 0.93) and Model B (PCC: 0.97, LCCC: 0.96), the correlation was slightly weaker than Zhou et al. (PCC: 0.98, LCCC: 0.98) or Rudie et al. (PCC: 0.98). The results of the Bland-Altman analysis of predicted minus true volume (Model A: −0.2 ± 1.6 mL, Model B: −0.1 ± 1.3 mL) are in good agreement both with zero and Zhou et al. (−0.1 ± 0.8 mL).

With the exception of Liu et al. [15], each patient-averaged Dice coefficient in recent work falls in the high 70s to low 80s and is drawn from a non-normal distribution with significant outliers. Our work and that of others (including those with multimodal MR inputs) fail to break through the 0.90 Dice ceiling. Part of this effect is explained by interrater differences. As a part of their work, Rudie et al. set a valuable baseline for interrater reliability by comparing manual segmentations of two neuroradiologists on their testing dataset (N = 100). Their interrater patient Dice coefficient was 0.83 ± 0.02 compared to their model’s result of 0.75 ± 0.03 (95% CIs). While these were statistically distinguishable, it clearly shows the limitation of fully-supervised learning methods when provided with such variance in ground truth annotations. If we compare the patient Dice coefficients of recent work and our own to this interrater baseline, the situation is much more optimistic.

Next, we discuss the model training and inference times. The metastasis components of the models took over 2 days to train, which was comparatively somewhat longer than recent works (Grøvik et al., 15 hours; Xue et al., 23 hours; Rudie et al., 24 hours; Charron et al., 30 hours) [8] [12] [13] [18]. Meanwhile, the inference time of 2 minutes was longer compared to Xue et al. (20 seconds), Rudie et al. (25 seconds), or Grøvik et al. (1 minute) but shorter than Charron et al. (20 minutes). Note that these reported times have many contributing factors, among which are the model complexity and quantity of training data, but also the computing hardware and software implementation details.

Our work carries some other limitations. While we have shown the power of including CECT in our model, iodine contrast may be contraindicated for some patients, and CT acquisition contributes to the patient’s radiation dose. Furthermore, not all other institutions acquire CT simulation for SRS treatment planning and setup. Though we adequately segmented larger lesions, our volume analysis showed the models systematically over-contoured small lesions. The lack of dependence on the γ parameter suggests the addition of boundary loss did not contribute to this effect, but also does not ameliorate it. It is possible that the Dice-like measure used for training is inherently weighted towards larger metastases, which could introduce a bias to over-contour the smaller lesions. Though we reported very high patient-averaged sensitivity of 95%, the presence of any false positives is a hindrance that limits the possibility of a fully automatic clinical implementation. Lastly, a thorough comparison with other recent works would require evaluation on a common patient dataset.

Conclusion

In closing, we curated a dataset of 511 SRS patients and produced a multi-stage 3D CNN model to automatically detect and segment brain metastases on T1+C or co-registered CECT and T1+C. We employed data augmentation via distributed computing to enhance the model generalizability. We also performed brain extraction in the presence of metastases using a deep learning model. We showed that scheduled boundary loss optimization and the incorporation of CECT both serve to benefit this task for our patient dataset. These developments are complementary to ongoing efforts to develop better fundamental model architectures. Surveying our own testing performance after these efforts, we reported metastasis segmentation quality comparable to the recent literature, and superior detection performance for the smallest metastases. We believe our approach is powerful enough that it may begin to aid clinical practice as a diagnostic tool, with the caveat that an expert still must review and correct the metastasis candidates. Finally, it is clear that approaching this problem using isolated datasets within individual institutions is fundamentally limited. Either a multi-institutional, de-identified dataset or a federated learning approach are absolutely necessary to advance the future study of artificial intelligence for brain metastases.

Table 2:

Comparison of our work with the recent literature. Pt. = patient, met. = metastasis, SSD = single-shot detector, sens. = sensitivity, FPs = false positives. Quoted uncertainties are standard deviations.

| Work | DL Model | Inputs | Skull Stripping |

No. of Pts. (train/test) |

No.

of Mets. (train/test) |

Met. size [mm] |

Met. vol. [mL] |

Lesions /pt. |

Avg. Pt. PPV (%) |

Avg. Pt. Sens. (%) |

FPs/Pt. | Avg. Pt. Dice (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liu et al. [15] | 3D DeepMedic | T1+C | ROBEX | 225/15 | −/− | — | 0.7 ± 2 | 6 ± 9 | — | — | — | 67 ± 3 |

| Charron et al. [12] | 3D DeepMedic | T1+C | BET | 164/18 | 374/38 | 2-27 | 0.01-37 | — | — | 92 ± 24 | 11 ± 8 | 77 ± 21 |

| multi-MR | — | 93 ± 20 | 8 ± 7 | 79 ± 21 | ||||||||

| Grøvik et al. [13] | 2D GoogleNet | multi-MR | BET | 105/51 | −/856 | 2-50 | — | — | — | 83 ± 22 | 3 ± 7 (≥10 mL) | 79 ± 12 |

| Dikici et al. [16] | 3D CropNet | T1+C | No | 158 | 932 | 2-14 | 0.16 ± 0.28 | 4 ± 6 | — | 90 | 9 ± 3 | — |

| Bousabarah et al. [14] | 3D U-Net | T1+C | HD-BET | 469/40 | 1149/83 | — | — | — | — | 77-82 | — | 71 |

| Zhang et al. [17] | Faster R-CNN | T1+C | Freesurfer | 270/45 | 1565/276 | 1-30 | — | — | — | 96 ± 12 | 20 ± 13 | — |

| Xue et al. [18] | 3D FCN | T1+C | No | 1201 | −/− | 2-45 | 0.07–24 | 1-17 | — | 96 (≥6 mm) | — | 85 ± 8 (≥6 mm) |

| Zhou et al. [19] | 2D SSD + 2D FCN | T1+C | No | 748/186 | 3131/766 | 1-52 | 0.001-25 | 1-27 | 58 ± 25 | 88 ± 19 | 3 ± 3 | 85 ± 13 |

| Rudie et al. [8] | 3D U-Net | multi-MR | Yes | 463/100 | 4494/708 | — | 0.02-10 | 1-50 | 93 [91,95] | 83 | 0.35 | 73 ± 14 |

| Amemiya et al. [23] | 2D SSD | CECT | No | 91/30 | 427/243 | 1-51 | — | 1-117 | 34 [33, 38] | 88 ± 3 | 15 ± 3 | N/A |

| Hsu et al. (this work) | 3D V-Net | T1+C | DL model | 409/102 | 1345/367 | 1-62 | 0.001-57 | 1-53 | 45 ± 26 | 95 ± 14 | 3 ± 2 | 71 ± 20 |

| T1+C & CECT | 55 ± 27 | 95 ± 14 | 2 ± 2 | 76 ± 18 |

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Anyi Li and the MSKCC Medical Physics Computer Service, as well as the MSKCC High Performance Computing Group, without whom this work would not have been possible. We also thank Dr. David Gutman (MSKCC Dept. of Radiology) for multiple helpful discussions.

Funding

MSKCC Support Grant/Core Grant P30 CA008748

Footnotes

Zhou et al. [19] and other works defined size as the largest cross-sectional diameter on axial slices. This measure, the Feret diameter, and the ESD can be different for larger, non-spherical metastases.

References

- [1].Steeg PS, Camphausen KA and Smith QR, "Brain metastases as preventive and therapeutic targets," Nature Reviews Cancer, vol. 11, pp. 352–363, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Frisk G, Svensson T, Bäcklund E, Lidbrink E, Blomqvist P and Smedby K, "Incidence and time trends of brain metastases admissions among breast cancer patients in Sweden," British Journal of Cancer, vol. 106, pp. 1850–1853, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Nayak L, Lee EQ and Wen PY, "Epidemiology of Brain Metastases," Current Oncology Reports, vol. 14, pp. 48–54, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].McTyre E, Scott J and Chinnaiyan P, "Whole brain radiotherapy for brain metastasis," Surgical Neurology International, vol. 4, pp. S236–S244, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Chang EL, Wefel JS, Hess KR, Allen PK, Lang FF, Kornguth DG, Arbuckle RB, Swint JM, Shiu AS, Maor MH and Meyers CA, "Neurocognition in patients with brain metastases treated with radiosurgery or radiosurgery plus whole-brain irradiation: a randomised controlled trial," The Lancet Oncology, vol. 10, no. 11, pp. 1037–1044, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Alexander E, Moriarty TM, Davis RB, Wen PY, Fine HA, Black PM, Kooy HM and Loeffler JS, "Stereotactic Radiosurgery for the Definitive, Noninvasive Treatment of Brain Metastases," Journal of the National Cancer Institute, vol. 87, no. 1, pp. 34–40, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ballangrud Å, Kuo LC, Happersett L, Lim SB, Beal K, Yamada Y, Hunt M and Mechalakos J, "Institutional experience with SRS VMAT planning for multiple cranial metastases," Journal of Applied Clinical Medical Physics, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 176–183, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Rudie JR, Weiss DA, Colby JB, Rauschecker AM, Laguna B, Braunstein S, Sugrue LP, Hess CP and Villanueva-Meyer JE, "3D U-Net Convolutional Neural Network for Detection and Segmentation of Intracranial Metastases," Radiology: Artificial Intelligence, vol. Online preprint, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ambroisini RD, Wang P and O'Dell WG, "Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging," Computer-Aided Detection of Metastatic Brain Tumors Using Automated Three-Dimensional Template Matching, vol. 31, pp. 85–93, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Pérez-Ramírez Ú, Arana E and Moratal D, "Brain Metastases Detection on MR by Means of Three-Dimensional Tumor-Appearance Template Matching," Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, vol. 44, pp. 642–652, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].LeCun Y, Bengio Y and Hinton G, "Deep Learning," Nature, vol. 521, pp. 436–444, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Charron O, Lallement A, Jarnet D, Noblet V, Clavier J-B and Meyer P, "Automatic Detection and Segmentation of Brain Metastases on Multimodal MR Images with a Deep Convolutional Neural Network," Computers in Biology and Medicine, vol. 95, pp. 43–54, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Grøvik E, Yi D, Iv M, Tong E, Rubin D and Zaharchuk G, "Deep Learning Enables Automatic Detection and Segmentation of Brain Metastases on Multi-Sequence MRI," Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, vol. 51, no. 1, pp. 175–182, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bousabarah K, Ruge M, Brand J-S, Hoevels M, Rueß D, Borggrefe J, Hokamp NG, Visser-Vandewalle V, Maintz D, Treuer H and Kocher M, "Deep Convolutional Neural Networks for Automated Segmentation of Brain Metastases Trained on Clinical Data," Radiation Oncology, vol. 15, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Liu Y, Stojadinovic S, Hrycushko B, Wardak Z, Lau S, Lu W, Yan Y, Jian SB, Zhen X, Timmerman R, Nedzi L and Gu X, "A deep convolutional neural network-based automatic delineation strategy for multiple brain metastases stereotactic radiosurgery," PLoS One, vol. 12, no. 10, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Dikici E, Ryu JL, Demirer M, Bigelow M, White RD, Slone W, Erdal BS and Prevedello LM, "Automated Brain Metastases Detection Framework for T1-Weighted Contrast-Enhanced 3D MRI," IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics, vol. 24, no. 10, pp. 2883–2893, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Zhang M, Young GS, Chen H, Li J, Qin L, McFaline-Figueroa JR, Reardon DA, Cao X, Wu X and Xu X, " Deep-Learning Detection of Cancer Metastases to the Brain on MRI," Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, vol. 52, no. 4, pp. 1227–1236, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Xue J, Wang B, Ming Y, Liu X, Jian Z, Wang C, Liu X, Chen L, Qu J, Xu S, Tang X, Mao Y, Liu Y and Li D, "Deep learning–based detection and segmentation-assisted management of brain metastases," Neuro-Oncology, vol. 22, no. 4, pp. 505–514, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Zhou Z, Sanders JW, Johnson J, Gule-Monroe M, Chen M, Briere TM, Wang Y, Son JB, Pagel MD, Ma J and Li J, "MetNet: Computer-aided segmentation of brain metastases in post-contrast T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging," Radiotherapy and Oncology, vol. 153, pp. 189–196, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Fink KR and Fink JR, "Imaging of Brain Metastases," Surgical Neurology International, vol. 4, no. Suppl 4, pp. S209–S219, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Mathews MS, Linskey ME, Hasso AN and Fruehauf JP, "The effect of bevacizumab (Avastin) on neuroimaging of brain metastases," Surgical Neurology, vol. 70, no. 6, pp. 649–652, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Arevalo OD, Soto C, Rabiei P, Kamali A, Ballester LY, Esquenazi Y, Zhu J-J and Riascos RF, "Assessment of Glioblastoma Response in the Era of Bevacizumab: Longstanding and Emergent Challenges in the Imaging Evaluation of Pseudoresponse," Frontiers in Neurology, vol. 10, p. 460, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Amemiya S, Takao H, Kato S, Yamashita H, Sakamoto N and Abe O, "Automatic detection of brain metastases on contrast-enhanced CT with deep-learning feature-fused single-shot detectors," European Journal of Radiology, vol. 136, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Smith SM, "Fast robust automated brain extraction," Human Brain Mapping, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 143–155, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Fischl B, "FreeSurfer," NeuroImage, vol. 62, no. 2, pp. 774–781, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ellingson B et al. "Consensus recommendations for a standardized Brain Tumor Imaging Protocol in clinical trials," Neuro-Oncology, vol. 17, no. 9, pp. 1188–1198, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Nelson AS, Piper JW, JKavorek AR, P. SD A R and Lu M, "Comparison of 2 Atlas-Based Segmentation Methods for Head and Neck Cancer With RTOG-Defined Lymph Node Levels," International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics, vol. 90, no. 1, p. S882, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Sharp GC, Li R, Wolfgang J, Chen GT, ' Peroni M, Spadea MF, Mori S, Zhang J, Shackleford J and Kandasamy N, "Plastimatch – An Open Source Software Suite for Radiotherapy Image Processing," in Proceedings of the XVI’th International Conference on the use of Computers in Radiotherapy, Amsterdam, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Tustison N, Avants B, Cook P, Zheng Y, Egan A, Yushkevich P and Gee J, "N4ITK: Improved N3 Bias Correction," IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, vol. 29, no. 6, pp. 1310–1320, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Milletari F, Navab N and Ahmadi S-A, "V-Net: Fully Convolutional Neural Networks for Volumetric Medical Image Segmentation," in International Conference on 3D Vision (3DV), Stanford, CA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Ronneberger O, Fischer P and Brox T, "U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation," in International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Munich, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Glorot X and Bengio Y, "Understanding the difficulty of training deep feedforward neural networks," in 13th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, Sardinia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Abadi M et al. "TensorFlow: Large-Scale Machine Learning on Heterogeneous Distributed Systems," 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Sada A, Kinoshita Y, Shiota S and Kiya H, "Histogram-based image pre-processing for machine learning," in IEEE 7th Global Conference on Consumer Electronics (GCCE), Nara, JP, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Rueckert D, Sonoda LI, Hayes C, Hill DL, Leach MO and Hawkes DJ, "Nonrigid registration using free-form deformations: application to breast MR images," IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, vol. 18, no. 8, pp. 712–721, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Unser M, "Splines: A perfect fit for signal/image processing," IEEE Signal Processing Magazine, vol. 16, no. 6, pp. 22–38, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Shorten C and Khoshgoftaar TM, "A survey on image data augmentation for deep learning," Journal of Big Data, vol. 6, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Schmuck F and Haskin R, "GPFS: A Shared-Disk File System for Large Computing Clusters," in Proceedings of the FAST'02 Conference on File and Storage Technologies, Monterey, CA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kervadec H, Bouchtiba J, Desrosiers C, Granger É, Dolz J and Ben Ayed I, "Boundary Loss for Highly Unbalanced Segmentation," in Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Medical Imaging with Deep Learning, London, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Salehi SS, Erdogmus D and Gholipour A, "Tversky Loss Function for Image Segmentation Using 3D Fully Convolutional Deep Networks," in International Workshop on Machine Learning in Medical Imaging, Quebec City, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Kingma D and Ba J, "Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization," in 3rd International Conference for Learning Representations, San Diego, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [42].McCormick M, Liu X, Jomier J, Marion C and Ibanez L, "ITK: enabling reproducible research and open science," Frontiers in Neuroinformatics, vol. 7, p. 45, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].McNemar Q, "Note on the sampling error of the difference between correlated proportions or percentages," Psychometrika, vol. 12, pp. 153–157, 1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Smith SM, "Fast robust automated brain extraction," Human Brain Mapping, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 143–155, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]