Resumo

Fundamento

A redução dos níveis de colesterol LDL é a pedra angular na redução de risco, mas muitos pacientes de alto risco não estão atingindo as metas lipídicas recomendadas, mesmo em países de alta renda.

Objetivo

Avaliar se os pacientes atendidos na rede pública de saúde da cidade de Curitiba estão atingindo as metas de colesterol LDL após infarto agudo do miocárdio (IAM).

Métodos

Esta coorte retrospectiva explorou os dados de pacientes internados com IAM entre 2008 e 2015 em hospitais públicos da cidade de Curitiba. Para avaliar o atingimento da meta de colesterol LDL, utilizamos o último valor registrado no banco de dados para cada paciente até o ano de 2016. Para aqueles que tinham pelo menos um valor de colesterol LDL registrado no ano anterior ao IAM, calculou-se o percentual de redução. O nível de significância adotado para a análise estatística foi p<0,05.

Resultados

Dos 7.066 pacientes internados por IAM, 1.451 foram acompanhados em ambiente ambulatorial e tiveram pelo menos uma avaliação de colesterol LDL. A média de idade foi 60,8±11,4 anos e 35,8%, 35,2%, 21,5% e 7,4% dos pacientes apresentavam níveis de colesterol LDL≥100, 70–99, 50–69 e <50 mg/dL, respectivamente. Destes, 377 pacientes também tiveram pelo menos uma avaliação de colesterol LDL antes do IAM. As concentrações médias de colesterol LDL foram 128,0 e 92,2 mg/dL antes e após o IAM, com redução média de 24,3% (35,7 mg/dL). Os níveis de colesterol LDL foram reduzidos em mais de 50% em apenas 18,3% dos casos.

Conclusão

Na cidade de Curitiba, pacientes do sistema público de saúde, após infarto do miocárdio, não estão atingindo níveis adequados de colesterol LDL após IAM.

Keywords: Doenças Cardiovaculares, Infarto do Miocárdio, Dislipidemias, Prevenção Secundária, Diabetes Mellitus, Colesterol LDL, Epidemiologia, Prevenção e Controle, Fatores de Risco

Introdução

As doenças cardiovasculares (DCVs) são a principal causa de óbito no Brasil e no mundo. Globalmente, reportou-se uma estimativa de cerca de 18 milhões de óbitos por DCV em 2017, 85% das quais foram atribuídas a doenças isquêmicas do coração e cerebrovasculares. 1 De acordo com as Estatísticas Cardiovasculares - Brasil, aproximadamente 388.268 pessoas morreram de DCV no país. 2 Embora a taxa de mortalidade por doença isquêmica do coração (DIC) tenha permanecido estável na década de 2000, 3 dados atuais mostram que a taxa de mortalidade por DIC padronizada por idade tem diminuído no Brasil. 2

Níveis plasmáticos elevados de colesterol LDL (lipoproteína de baixa densidade) estão intimamente relacionados com o aumento do risco cardiovascular, independentemente da faixa etária. 4 Além disso, a redução do colesterol LDL está associada à redução do risco cardiovascular: uma redução de 39 mg/dL está associada a uma redução de aproximadamente 20% no risco de eventos cardiovasculares maiores, 5 um efeito semelhante entre os sexos. 6 Em pacientes com alto risco de eventos cardiovasculares, principalmente aqueles com doença coronariana estabelecida, grandes reduções no Colesterol LDL com maiores doses de estatinas têm mostrado resultados melhores do que aquelas com doses inferiores. 7 , 8 Da mesma forma, reduções adicionais no colesterol LDL, por meio do emprego de terapias adicionais combinadas com estatinas em pacientes de alto risco nas doses máximas otimizadas também estão associadas a reduções adicionais em novos eventos. 9 , 10

Embora não se tenha identificado um nível mínimo ideal de colesterol LDL, sem risco de DCVs, os consensos e diretrizes atuais buscam estabelecer metas lipídicas para orientar o atendimento médico individualizado. 11 - 13 Essas metas podem ser expressas como valores-alvo absolutos de colesterol LDL ou como porcentagens mínimas de redução do colesterol LDL. No entanto, muitos pacientes de alto risco não estão atingindo as metas lipídicas recomendadas, 14 mesmo sob terapia hipolipemiante. 15 Este é um problema multifatorial que requer quantificação em contextos locais específicos para garantir a viabilidade local e a eficácia das soluções propostas. 16 No Brasil, embora a saúde seja considerada um dever do Estado, o acesso a estatinas mais potentes é limitado no Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS), sistema público de saúde brasileiro que atende mais de 70% da população. 17

Até o momento, alguns estudos de mundo real foram conduzidos no Brasil, mostrando que pacientes com risco cardiovascular estão atingindo as metas lipídicas recomendadas. 18 , 19 O objetivo deste estudo foi determinar a porcentagem de pacientes no sistema público de saúde da cidade de Curitiba, Brasil, que atingiram as metas de colesterol LDL após internação por infarto agudo do miocárdio (IAM), incluindo tanto o alcance dos valores-alvo de colesterol LDL quanto o percentual de redução do colesterol LDL em relação aos níveis anteriores ao IAM.

Métodos

Trata-se de um estudo de coorte retrospectivo realizado no banco de dados da Secretaria Municipal de Saúde (SMS) de Curitiba, contendo todas as informações dos pacientes internados na rede pública municipal de saúde, desde a entrada até a alta. O presente estudo foi aprovado pelo Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa (CEP) da SMS e pela instituição acadêmica envolvida.

A coorte de pacientes selecionada no banco de dados incluiu pacientes de ambos os sexos com 18 anos ou mais, internados em um hospital público da rede de saúde local com diagnóstico primário de IAM (código CID-I21) entre janeiro de 2008 e dezembro de 2015. Os resultados dos exames laboratoriais foram obtidos a partir de um segundo banco de dados e as identidades dos pacientes foram verificadas minuciosamente para evitar duplicação e discrepâncias. Casos duplicados e casos com discrepâncias foram excluídos. Pacientes sem pelo menos um valor de colesterol LDL registrado no ano seguinte ao IAM também foram excluídos. Realizou-se uma busca no banco de dados do laboratório para encontrar os pacientes (entre os pacientes incluídos, ou seja, aqueles com pelo menos um exame após o IAM) que também haviam feito pelo menos um exame de colesterol LDL no ano anterior ao IAM para calcular o percentual de redução.

Avaliação do colesterol LDL

Com base na fórmula de Friedewald, obteve-se o último valor de colesterol LDL, registrado na base de dados após o IAM, ou seja, o mais distante da data do IAM, exceto para pacientes com triglicerídeos acima de 400 mg/dL. Foram determinadas as porcentagens de pacientes que alcançaram níveis médios de colesterol LDL <50, 50–69, 70–99 ou ≥100 mg/dL.

Para determinar o percentual de redução alcançado, pesquisou-se o banco de dados em busca de pacientes com pelo menos um exame de colesterol LDL no ano anterior ao IAM. Nos casos de pacientes com mais de um exame, utilizou-se o valor de colesterol LDL mais próximo ao evento agudo. O valor de colesterol LDL mais próximo ao IAM no ano anterior ao evento foi comparado ao último valor obtido após o IAM. As porcentagens de pacientes que alcançaram reduções do colesterol LDL de 50–100% ou <50% ou aumentos <50% ou 50–100% também foram determinadas.

Análise Estatística

Realizou-se a análise estatística descritiva dos dados. Os resultados foram expressos como médias e desvios-padrão (variáveis quantitativas) ou como frequências e porcentagens (variáveis categóricas). Utilizou-se o teste t de Student pareado para comparar o colesterol LDL antes e depois do IAM. A normalidade dos dados foi analisada pelo teste de Kolmogorov-Smirnov. Definiu-se a significância estatística com p<0,05. Os dados foram analisados com o programa computacional IBM SPSS Statistics v.20.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

Resultados

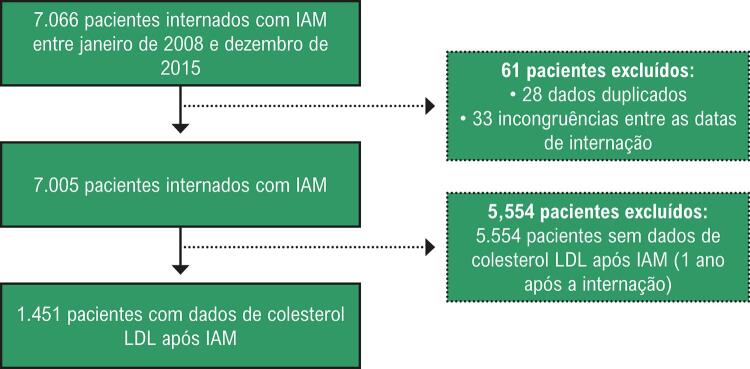

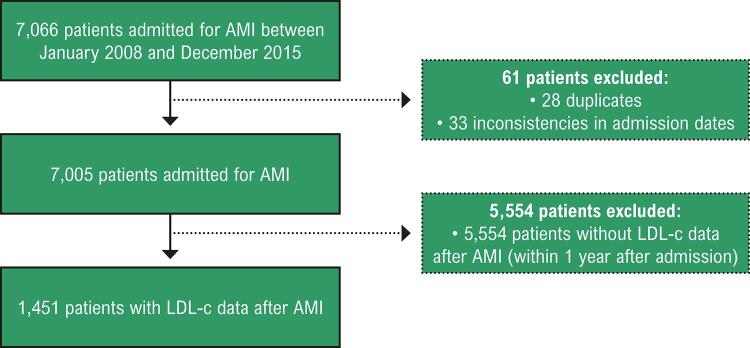

Do total de 7.066 pacientes internados por IAM entre janeiro de 2008 e dezembro de 2015, 61 foram excluídos devido a pelo menos um dos critérios de exclusão (duplicação ou discrepância entre as datas de internação). Dos 7.005 casos restantes, 5.554 foram excluídos por falta de resultados do exame de colesterol LDL após o IAM. Portanto, avaliou-se o colesterol LDL após o IAM em 1.451 casos ( Figura 1 ). Destes, 377 pacientes também realizaram pelo menos um exame no ano anterior ao IAM, o que permitiu o cálculo da variação percentual.

Figura 1. – Fluxograma das características da amostra do estudo. IAM: Infarto agudo do miocárdio; colesterol LDL: Colesterol LDL (lipoproteína de baixa densidade).

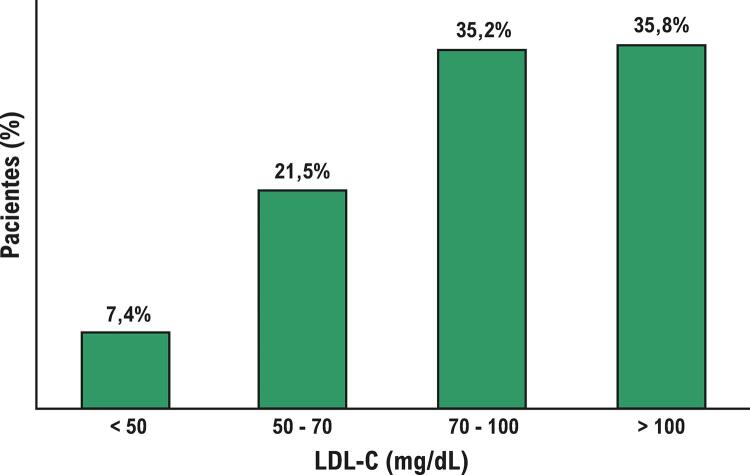

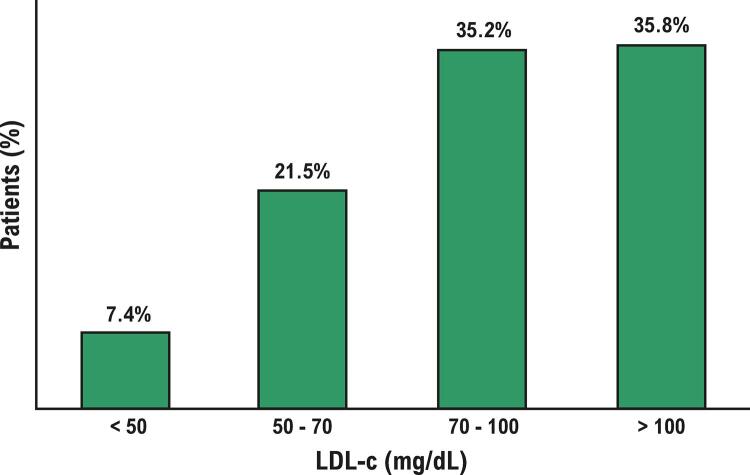

A média de idade dos 1.451 pacientes foi 60,8±11,4. A Tabela 1 mostra a média e o desvio padrão (DP) do colesterol LDL entre os 1.451 casos após o IAM. O tempo médio até o último exame de colesterol LDL realizado após o IAM foi de 32,7 meses. A Figura 2 mostra as porcentagens dos níveis de colesterol LDL dos pacientes. Assim, apenas 28,9% dos pacientes apresentaram níveis de colesterol LDL <70 mg/dL após IAM.

Tabela 1. – Média e desvio padrão do colesterol LDL, colesterol HDL, colesterol total e triglicerídeos entre os 1.451 casos após o infarto agudo do miocárdio.

| Média | DP | |

|---|---|---|

| Colesterol LDL (mg/dL) | 93,3 | 34,2 |

| Colesterol HDL (mg/dL) | 42,9 | 11,6 |

| Colesterol total (mg/dL) | 168,1 | 39,8 |

LDL: lipoproteína de baixa densidade; HDL: lipoproteína de alta densidade; DP: desvio padrão.

Figura 2. – Distribuição dos níveis de colesterol LDL (n=1.451). LDL-C: colesterol lipoproteína de baixa densidade.

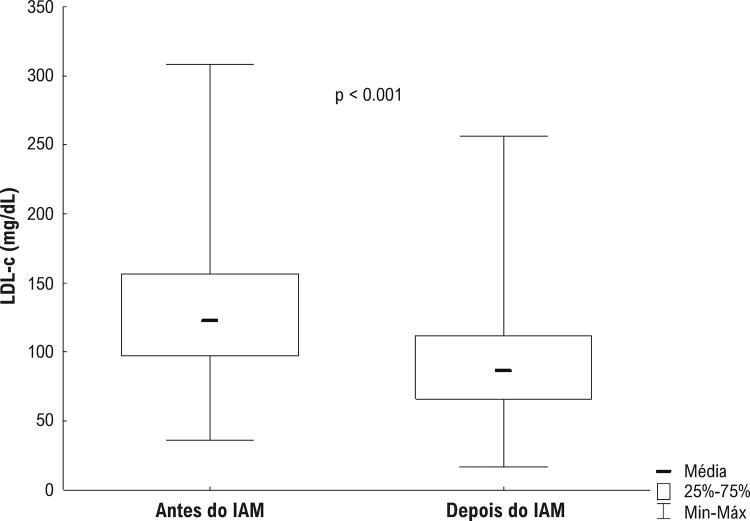

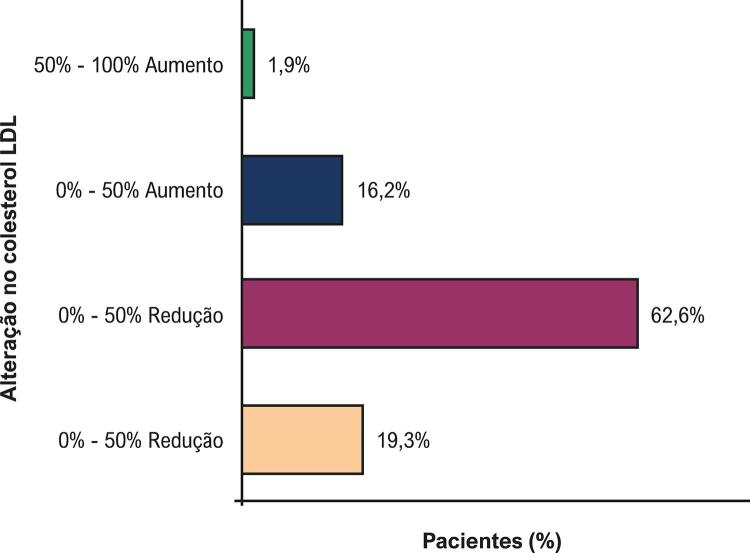

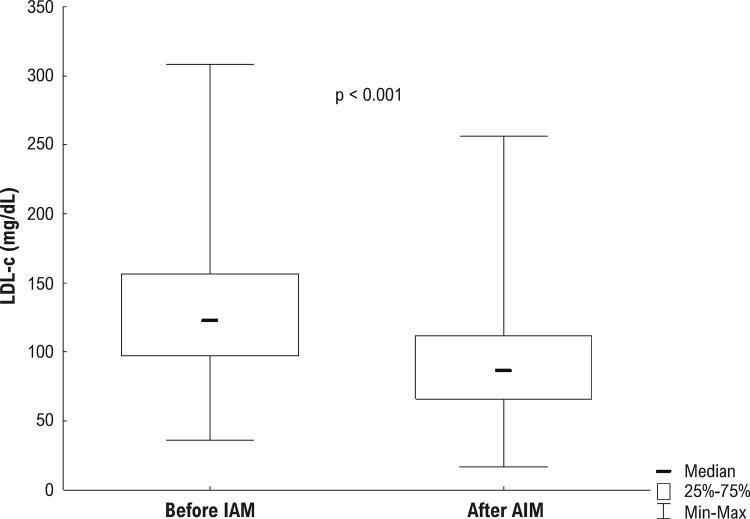

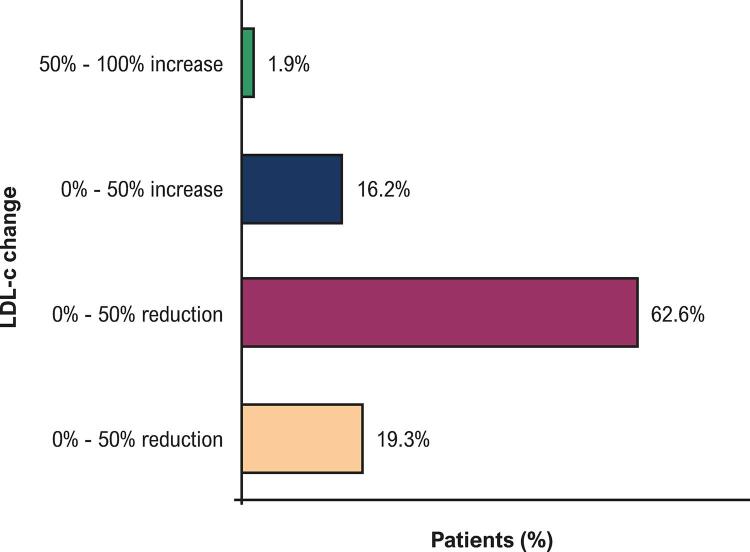

Os valores de colesterol LDL após IAM, entre os 377 pacientes com dados de colesterol LDL no ano anterior ao IAM e pelo menos um exame de colesterol LDL após o evento, foram os seguintes: na mesma faixa de antes (40,3%), em uma faixa menor do que antes (53,3%), e em uma faixa maior do que antes (6,4%) ( Tabela 2 ). O tempo médio entre os exames de colesterol LDL antes e o mais próximo ao IAM e ao evento em si foi de 4,8 meses. As concentrações médias de colesterol LDL ( Figura 3 ) foram 128,0 e 92,2 mg/dL antes e após o IAM, respectivamente ( Tabela 3 ). A Figura 4 mostra que 19,3% dos pacientes tiveram uma redução de mais de 50% nos níveis de colesterol LDL após o IAM. Além disso, aproximadamente 82% dos pacientes alcançaram algum grau de redução do colesterol LDL ( Figura 4 ).

Tabela 2. – Distribuição dos níveis de colesterol LDL antes e depois do infarto agudo do miocárdio.

| Colesterol LDL após IAM (mg/dL) | Colesterol LDL antes do IAM (mg/dL) | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| <50 | 50–69 | 70–99 | ≥100 | ||

| <50 | 1 | 6 | 8 | 11 | 26 |

| 0,3% | 1,6% | 2,1% | 2,9% | ||

| 50–69 | 2 | 6 | 29 | 56 | 93 |

| 0,5% | 1,6% | 7,7% | 14,6% | ||

| 70–99 | 2 | 4 | 31 | 93 | 130 |

| 0,5% | 1,3% | 8,2% | 24,4% | ||

| ≥100 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 115 | 128 |

| 0,0% | 0,0% | 3,7% | 30,2% | ||

| Total | 6 | 17 | 82 | 272 | 377 |

LDL: lipoproteína de baixa densidade; IAM: infarto agudo do miocárdio.

Figura 3. – Box-plot do colesterol LDL antes e depois do infarto agudo do miocárdio. Teste t de Student: p<0.05. IAM: Infarto agudo do miocárdio; colesterol LDL: Colesterol LDL (lipoproteína de baixa densidade).

Tabela 3. – Média e diminuição do colesterol de lipoproteína de baixa densidade antes e depois do infarto agudo do miocárdio entre os 377 casos.

| Variável | Média | DP | p* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antes do IAM (mg/dL) | 128,0 | 42,7 | <0,001 |

| Após IAM (mg/dL) | 92,2 | 36,9 | |

| Redução (absoluta) (mg/dL) | 35,7 | 40,1 | |

| Redução (relativa) (%) | 24,3% | 28,4% |

*Teste t de Student pareado, p<0,05. IAM: infarto agudo do miocárdio; DP: desvio padrão.

Figura 4. – Distribuição dos pacientes de acordo com a alteração no colesterol LDL antes e depois do infarto agudo do miocárdio.

LDL: Colesterol LDL (lipoproteína de baixa densidade).

Discussão

Apesar da eficácia da diminuição nas taxas de lipídios na redução de eventos cardiovasculares, muitos pacientes de alto risco não estão atingindo a meta lipídica recomendada. Este novo estudo realizado com dados de pacientes com IAM internados no sistema público de saúde de Curitiba constatou que aproximadamente 82% dos pacientes alcançaram algum grau de redução do colesterol LDL, com apenas aproximadamente 30% atingindo níveis médios <70 mg/dL e aproximadamente 20% tendo uma redução >50% em comparação com os níveis anteriores ao IAM.

Os resultados deste estudo são semelhantes aos conduzidos em contextos socioeconômicos muito diferentes. Dados recentes de 27 países europeus mostraram que, entre 8.261 pacientes coronarianos incluídos no estudo EUROASPIRE V, 80% estavam tomando estatinas e 71% tinham concentrações de colesterol LDL ≥70 mg/dL. 15 Em um estudo americano mais antigo, que também avaliou pacientes após síndrome coronariana aguda (SCA) por meio da avaliação do controle lipídico no primeiro ano após o evento, apenas 31% dos pacientes atingiram o nível alvo de colesterol LDL <70 mg/dL. 20 Os dados obtidos neste estudo são alarmantes por se tratarem de pacientes com pós-SCA, uma população de alto risco para novos eventos cardiovasculares a curto e médio prazo. O registro GRACE mostrou que aproximadamente 10% dos pacientes que receberam alta após SCA sofrerão IAM não fatal ou morte relacionada ao sistema cardiovascular em seis meses. 21 Uma subanálise mais recente de pacientes com IAM prévio incluídos no estudo FOURIER demonstrou que um IAM mais recente apresenta maior risco de um novo evento cardiovascular do que um IAM mais distante (mais de dois anos) e esses pacientes são justamente aqueles que se beneficiam de uma redução lipídica mais agressiva. 22

As metas propostas para os níveis de colesterol LDL foram extrapoladas a partir dos resultados de estudos com doses fixas de estatinas porque o primeiro estudo visando uma meta específica de colesterol LDL de 25–50 mg/dL foi conduzido apenas recentemente. 23 Portanto, em 2013, a American Heart Association e o American College of Cardiology pararam de recomendar uma meta específica de colesterol LDL e propuseram o tratamento de pacientes de alto risco com altas doses de estatinas potentes capazes de reduzir o colesterol LDL em >50% com base nos resultados estudos intervencionais randomizados conduzidos nessas populações. 24 Um estudo clínico que comparou estratégias para reduzir o risco cardiovascular (nível atingido ou porcentagem de redução) para determinar qual é o mais eficaz ainda não foi realizado, mas uma análise de dados de 13.937 pacientes dos três estudos distintos sobre prevenção secundária com estatinas sugere que uma redução de >50% reduziria o risco incrementalmente, mesmo em pacientes com níveis de colesterol LDL <70 mg/dL. 25

Na presente amostra, mais pacientes alcançaram níveis de colesterol LDL <70 mg/dL do que aqueles que alcançaram uma redução de >50%. Isso pode ser explicado pelo fato de o percentual de redução estar diretamente associado ao uso de altas doses de estatinas potentes. O acesso a esses medicamentos no sistema público de saúde brasileiro é restrito e a indisponibilidade desses medicamentos neste sistema é uma barreira reconhecida ao seu uso. 26 Há relatos de menor uso de medicamentos necessários para a prevenção secundária em países de baixa renda. Por exemplo, o estudo PURE relatou 66,5% e 3,3% do uso de estatinas para prevenção secundária em países de alta e baixa renda, respectivamente. 27

Na época em que este estudo foi realizado, a 5ª Diretriz Brasileira de Dislipidemia e Prevenção da Aterosclerose 28 recomendava metas de colesterol LDL abaixo de 70 mg/dL para pacientes com alto risco cardiovascular. Além disso, a recomendação para reduzir o colesterol LDL em pelo menos 50% aparece apenas na diretriz brasileira de 2017. 11 As evidências atuais indicam que o benefício clínico não depende do tipo de estatina usada, mas sim da extensão da redução do colesterol LDL. Mais importante ainda é avaliar o risco cardiovascular do paciente e iniciar o tratamento visando a redução adequada do risco. Para pessoas de risco muito alto, uma meta de colesterol LDL de <55 mg/dL e uma redução de ≥50% do colesterol LDL basal deve ser alcançada. 13

A American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists e o American College of Endocrinology propuseram uma meta de colesterol LDL de <55 mg/dL para uma nova categoria de risco denominada “risco extremo”. 29 Esta categoria se refere a pacientes com doença cardiovascular aterosclerótica progressiva (DCAP), incluindo angina instável que persista mesmo após o alcance de um colesterol LDL de <70 mg/dL, ou DCAP clinicamente estável com diabetes, doença renal crônica estágio 3 ou 4 e/ou hipercolesterolemia familiar heterozigótica, ou pacientes com histórico de DCAP prematura (<55 anos de idade para homens ou <65 anos de idade para mulheres). Neste estudo, apenas 7,4% dos pacientes atingiram níveis inferiores a 50 mg/dL após IAM.

Embora as diretrizes americanas recomendem a redução dos níveis de colesterol LDL em pelo menos 50% do nível basal em pacientes coronarianos, 30 as diretrizes europeias propõem uma meta de colesterol LDL de <55 mg/dL e uma redução mínima de 50% no colesterol LDL em pacientes com doença arterial coronariana (DAC) documentada. 13 As diretrizes americanas e europeias recomendam o tratamento com uma combinação de medicamentos hipolipemiantes para atingir essas metas. No entanto, a diretriz americana concorda que o foco é a redução do colesterol LDL, principalmente com base em uma redução de >50% do valor basal, em vez de atingir os níveis-alvo específicos de colesterol LDL. No entanto, é importante destacar que os inibidores da pró-proteína convertase subtilisina/kexina tipo 9 (PCSK9) e a ezetimiba são aceitáveis em pacientes com IAM considerado de risco muito alto e com colesterol LDL ≥70 mg/dL em estatina com tolerância máxima.

Os resultados do estudo IMPROVE-IT mostraram que um número significativamente maior de pacientes com DAC tratados com estatina e ezetimiba alcançaram as metas de colesterol LDL em comparação com estatinas de maneira isolada. 31

Limitações do Estudo

Esta análise tem várias limitações possíveis. Apenas uma minoria dos pacientes internados com IAM na rede pública de saúde de Curitiba realizou exame de colesterol no ano seguinte ao IAM. Muitos pacientes que receberam tratamento em Curitiba provavelmente não eram da cidade. Portanto, a perda de seguimento ambulatorial foi significativa, pois esses pacientes retornaram às suas cidades de origem para acompanhamento médico e cuidados de prevenção secundária ou até mesmo interromperam o acompanhamento. Não foram obtidos dados sobre o colesterol LDL de pacientes que não receberam seguimento ambulatorial na rede pública de saúde de Curitiba. No entanto, a coorte de análise foi representativa de uma população real de Curitiba com infarto do miocárdio que sobreviveu à hospitalização. Por fim, a maior limitação deste estudo foi a ausência de dados sociodemográficos e medicamentosos, seja quanto ao uso (ou não) de estatinas, seja quanto às doses administradas antes e após o IAM.

Conclusão

Após o IAM, uma minoria de pacientes de alto risco cardiovascular atingiu as metas de colesterol LDL recomendadas nesta coorte de pacientes internados no sistema público de saúde da cidade de Curitiba. A semelhança entre os resultados deste estudo e os de estudos realizados em países com condições socioeconômicas muito diferentes sugere que outros fatores, provavelmente relacionados aos próprios médicos e pacientes, podem estar associados a esse cenário.

Concepção e desenho da pesquisa: Bernardi A, Erbano LO, Guarita-Souza LC, Baena CP, Faria-Neto JR; Obtenção de dados: Bernardi A, Erbano LO; Análise e interpretação dos dados e Revisão crítica do manuscrito quanto ao conteúdo intelectual importante: Bernardi A, Olandoski M, Guarita-Souza LC, Baena CP, Faria-Neto JR; Análise estatística: Olandoski M, Erbano LO, Faria-Neto JR; Redação do manuscrito: Bernardi A, Faria-Neto JR.

Vinculação acadêmica

Este artigo é parte de tese de doutorado de André Bernardi pela Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Paraná.

Aprovação ética e consentimento informado

Este estudo foi aprovado pelo Comitê de Ética da Secretaria Municipal de Saúde de Curitiba sob o número de protocolo 1.647.450. Todos os procedimentos envolvidos nesse estudo estão de acordo com a Declaração de Helsinki de 1975, atualizada em 2013.

Fontes de financiamento: O presente estudo não teve fontes de financiamento externas.

Referências

- 1.Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018;392(10159):1736-88: doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32203-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Oliveira GMM, Brant LCC, Polanczyk CA, Biolo A, Nascimento BR, Malta DC, et al. Cardiovascular Statistics - Brazil 2020. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2020 Sep;115(3):308-439. doi: 10.36660/abc.20200812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Baena CP, Chowdhury R, Schio NA, Sabbag AE Jr, Guarita-Souza LS, Olandoski M, et al. Ischaemic heart disease deaths in Brazil: current trends, regional disparities and future projections. Heart 2013;99:1359-64. DOI: 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-303617 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Clarke R, Sherliker P, Emberron J, Halsey I, Emberson J, Halsey J, et al. Prospective Studies C, Lewington S, Whitlock G, et al. Blood cholesterol and vascular mortality by age, sex, and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of individual data from 61 prospective studies with 55,000 vascular deaths. Lancet 2007;370(9602):1829-39. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61778-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Cholesterol Treatment Trialists C, Baigent C, Blackwell L, et al. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376(9753):1670-81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61350-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Cholesterol Treatment Trialists C, Fulcher J, O’Connell R, et al. Efficacy and safety of LDL-lowering therapy among men and women: meta-analysis of individual data from 174,000 participants in 27 randomised trials. Lancet 2015;385:1397-405. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.LaRosa JC, Grundy SM, Waters DD, Shear C, Barter P, Fruchart JC, et al.et al. Intensive Lipid Lowering with Atorvastatin in Patients with Stable Coronary Disease. N Engl J Med.2005;352(14):1425-35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050461. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Cannon CP, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, Rader DJ, Rouleau JL, Belder R, et al. Intensive versus Moderate Lipid Lowering with Statins after Acute Coronary Syndromes. New England Journal of Medicine 2004;350:(14)1495-504. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al. Ezetimibe Added to Statin Therapy after Acute Coronary Syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(15):2387-97. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040583. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, et al. Evolocumab and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(18):1713-22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1615664 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Faludi AA, Izar MCO, Saraiva JFK, Chacra APM, Bianco HT, Afiune A Neto, et al. Atualização da Diretriz Brasileira de Dislipidemias e Prevenção da Aterosclerose – 2017. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2017 Jul;109(2 Supl 1):1-76. doi: 10.5935/abc.20170121. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Lloyd-Jones DM, Morris PB, Ballantyne CM, Birtcher KK, Daly DD Jr, De Palma AS, et al. 2017 Focused Update of the 2016 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on the Role of Non-Statin Therapies for LDL-Cholesterol Lowering in the Management of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk. A Report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on Expert Consensus Decision Pathways . J Am Coll Cardiol.2017;70(14):1785-822. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL, Koskinas KC. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur Heart J. 2019;41(1):111-88. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz455. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Waters DD, Brotons C, Chiang CW, Ferrieres J, Foody J, Wouter J, et al. Lipid treatment assessment project 2: a multinational survey to evaluate the proportion of patients achieving low-density lipoprotein cholesterol goals. Circulation 2009;120(1):28-34. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.838466 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Kotseva K, De Backer G, De Bacquer D, Ryden L, Hoes A, Grobbee D, et al. Lifestyle and impact on cardiovascular risk factor control in coronary patients across 27 countries: Results from the European Society of Cardiology ESC-EORP EUROASPIRE V registry. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2019;26(8):824-35. doi: 10.1177/2047487318825350. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Murphy A, Faria-Neto JR, Al-Rasadi K, Blom D, Catapano A, Cuevas A, et al World Heart Federation Cholesterol Roadmap. Glob Heart. 2017;12(3):179-97 e5. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2017.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Massuda A, Hone T, Leles FAG, de Castro MC, Atun R. The Brazilian health system at crossroads: progress, crisis and resilience. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3(4):e000829. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Waters DD, Brotons C, Chiang CW, Ferrières J, Foody J, Jukema JW, Santos RD, et al. Lipid Treatment Assessment Project 2 Investigators. Lipid treatment assessment project 2: a multinational survey to evaluate the proportion of patients achieving low-density lipoprotein cholesterol goals. Circulation. 2009 Jul 7;120(1):28-34. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.838466. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Lotufo PA, Santos RD, Figueiredo RM, Pereira AC, Mill JG, Alvim SM, Fonseca MJ, Almeida MC, Molina MC, Chor D, Schmidt MI, Ribeiro AL, Duncan BB, Bensenor IM. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of high low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in Brazil: Baseline of the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil). J Clin Lipidol. 2016 May-Jun;10(3):568-76. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2015.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Melloni C, Shah BR, Ou FS, Roe MT, Smith SC Jr, Pollack CV Jr, et al. Lipid-lowering intensification and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol achievement from hospital admission to 1-year follow-up after an acute coronary syndrome event: results from the Medications ApplIed aNd SusTAINed Over Time (MAINTAIN) registry. Am Heart J 2010;160:1121-9, 9 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Fox KAA, Dabbous OH, Goldberg RJ, Pieper KS, Eagle KA, Vander Werf F, et al. Prediction of risk of death and myocardial infarction in the six months after presentation with acute coronary syndrome: prospective multinational observational study (GRACE). BMJ 2006;333(7578):1091. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38985.646481.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Sabatine MS, De Ferrari GM, Giugliano RP, Huber K, Lewis BS, Ferreira J, et al. Clinical Benefit of Evolocumab by Severity and Extent of Coronary Artery Disease: An Analysis from FOURIER. Circulation 2018;138(8):756-66. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.034309. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Schwartz GG, Bessac L, Berdan LG, Bhatt DL, Bittner V, Diaz R, et al. Effect of alirocumab, a monoclonal antibody to PCSK9, on long-term cardiovascular outcomes following acute coronary syndromes: rationale and design of the ODYSSEY outcomes trial. Am Heart J 2014;168(5):682-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, Bairdy Merz CN, Blum CB, Eckel RH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63(25 Pt B):2889-934. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Bangalore S, Fayyad R, Kastelein JJ, Laskey R, Amarenco P, De Micco DA, et al. 2013 Cholesterol Guidelines Revisited: Percent LDL Cholesterol Reduction or Attained LDL Cholesterol Level or Both for Prognosis? Am J Med 2016;129(4):384-91. DOI: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Banerjee A, Khandelwal S, Nambiar L, Saxena M, Peck V, Moniruzza M, et al. Health system barriers and facilitators to medication adherence for the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. Open Heart 2016;3(2):e000438. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2016-000438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Yusuf S, Islam S, Chow CK, Rangarajavan S, Dagemais G, Diaz R, et al. et al. Use of secondary prevention drugs for cardiovascular disease in the community in high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries (the PURE Study): a prospective epidemiological survey. The Lancet 2011;378(9798):1231-43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61215-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Xavier HT, Izar MC, Faria Neto JR, Assad MH, Rocha VZ, Sposito AC, et al. et al. V Diretriz Brasileira de Dislipidemia e Prevenção da Aterosclerose. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2013 101(4 Supl1):1-22. DOI: 10.5935/abc.2013S010 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Jellinger PS. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology Management of Dyslipidemia and Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease Clinical Practice Guidelines. Diabetes Spectr 2018;31(3):234-45. doi: 10.2337/ds18-0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, Bam C, Birtcher KK, Blumenthall RS, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2019;139(25):e1082-e1143. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Bohula EA, Giugliano RP, Cannon CP, Zhou J, Murphy AS, White JÁ, et al. Achievement of dual low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein targets more frequent with the addition of ezetimibe to simvastatin and associated with better outcomes in IMPROVE-IT. Circulation 2015;132(13):1224-33. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018381. [DOI] [PubMed]