Abstract

The phaC1 gene codes for the medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoate (mcl PHA) synthase of Pseudomonas oleovorans GPo1, which produces mcl PHA when grown in an excess of carbon source and under nitrogen limitation. In this work, we have demonstrated, by constructing a recombinant P. oleovorans strain carrying a phaC1::lacZ reporter system, that the phaC1 gene is expressed efficiently in the presence of octanoic acid while its expression is repressed when glucose or citrate is used as the carbon source. Moreover, a P. oleovorans GPo1 mutant (strain GPG-Tc6) expressing higher levels of the reporter gene than the wild-type strain in the presence of glucose or citrate has been generated by mini-Tn5 insertional mutagenesis. Characterization of this mutant allowed us to conclude that phaF, a gene located downstream of the pha gene cluster, was knocked out in this strain. P. oleovorans GPG-Tc6 regained the ability to control phaC1 gene expression when complemented with the phaF wild-type gene. Sequencing data revealed the presence of three complete open reading frames (ORFs) in this region: ORF1 and phaI and phaF genes. The amino acid sequences of the phaI gene product and the N-terminal half of the PhaF protein showed a significant degree of similarity. Furthermore, the primary structure of the PhaF C terminus identifies this protein as a member of the histone H1-like group of proteins. Northern blot analysis showed two transcription units containing phaF, i.e., phaF and phaIF transcripts. Expression of the phaIF operon is more efficient in the presence of octanoic acid and is enhanced by the lack of the PhaF protein. In addition, it has also been demonstrated that both PhaF and PhaI proteins are bound to PHA granules produced by P. oleovorans. A model for the role of PhaF in regulating PHA synthesis is presented.

Pseudomonas strains accumulate medium-chain-length poly(R)-3-hydroxyalkanoate (PHA) as carbon and energy source under conditions of limiting nutrients in the presence of an excess of carbon source (4). This bacterial storage material, mainly formed of monomers of 6 to 14 carbon atoms, has potential as a renewable and biodegradable plastic (33). Pseudomonas oleovorans GPo1 accumulates PHA only when alkanes or alkanoic acids are provided as carbon sources, in contrast to Pseudomonas putida KT2442 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, which are able to produce PHA not only from fatty acids but also from substrates such as glucose, citrate, or gluconate (13, 32).

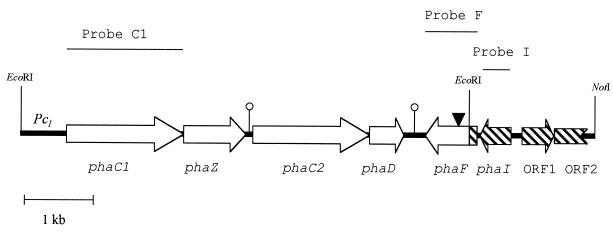

The pha gene cluster of P. oleovorans GPo1, which encodes the proteins involved in PHA metabolism, consists of four open reading frames (ORFs) transcribed in the same direction (Fig. 1): phaC1 and phaC2 genes, which encode PHA synthases (or PHA polymerases); the phaZ gene, which codes for a PHA depolymerase; and the phaD gene, which encodes a peptide of unknown function (15). A homologous pha cluster showing similar gene organization has also been found in P. aeruginosa (32). So far, very little is known about the regulatory system which drives the expression of the pha genes in these two Pseudomonas species. In the case of P. oleovorans GPo1, it has been reported that there are two promoters, both located upstream of the phaC1 gene, which resemble the consensus sequences for ς70- and ς54-dependent promoters (15, 33). The corresponding transcriptional start sites are located respectively 198 and 112 bp upstream of the ribosomal binding site (RBS) of the phaC1 gene (33). Nevertheless, it is not known whether this promoter region (designated PcI in Fig. 1) drives the expression of only the phaC1 gene or of the whole pha cluster as an operon. In this sense, two putative transcription terminators have been found downstream of the phaZ and phaD genes (Fig. 1) (15). Concerning P. aeruginosa, the existence of a promoter region upstream of phaC1 has been experimentally demonstrated. Moreover, PHA production from gluconate requires the intact RpoN ς factor (ς54), while PHA accumulation from octanoate was only partially abolished in ς54 mutants. In addition, Timm and Steinbüchel have suggested that PHA metabolism in P. aeruginosa is regulated at the level of gene expression, and they have described a putative truncated pha regulatory gene (ORF4), located downstream of the phaC1ZC2D gene cluster, which appears to encode a histone H1-like protein (32). Members of this group resemble eukaryotic histones based on their amino acid composition, abundance, and tight association with chromosomal DNA (6, 20). It has been demonstrated that histone H1-like proteins can induce changes in DNA topology, influencing gene expression (3). Interestingly, a homologous truncated gene (designated phaF in Fig. 1) has also been found downstream of the pha structural genes in P. oleovorans GPo1 (Fig. 1) (33).

FIG. 1.

Molecular organization of the pha gene cluster (15). C1, Z, C2, D, F, and I represent the names of the pha genes. Arrows indicate the directions of gene transcription. White arrows indicate the EcoRI DNA fragments characterized previously (15). Hatched arrows indicate the DNA region cloned in this work. Incomplete arrow indicates truncated gene. PcI means the promoter region upstream of the phaC1 gene. ▾ indicates the position of the insertion of the minitransposon in P. oleovorans GPG-Tc6. Loops show the positions of putative transcriptional terminators as previously proposed (15). The C1, F, and I probes used for this work are indicated as thin lines at the top of the figure.

To better understand the regulation of the expression of the pha genes and the principal role of PhaF, we assessed the effects of different growth conditions on the expression of pha genes of P. oleovorans GPo1 and identified the regulatory proteins involved in the regulation of pha gene expression. We have demonstrated, by isolation and characterization of a P. oleovorans phaF-negative strain, that the phaF gene of P. oleovorans GPo1 codes for a regulatory protein which is associated with PHA granules and controls the expression of the phaC1 gene and phaI gene, the latter coding for a newly identified granule-associated protein (GAP).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

Table 1 lists the bacterial strains and plasmids used and constructed in this study.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids with relevant genotype and phenotype

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype or phenotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| P. oleovorans | ||

| GPo1 | OCT, PHA+ | 30 |

| GPG132 | GPo1 derivative, PcI::lacZ, Kmr | This study |

| GPG-Tc6 | GPG132 derivative, Tcr, Kmr, phaF::mini-Tn5Tc | This study |

| GPG-Tc661 | GPG-Tc6 derivative, lacIq-Ptrc::phaF, Tcr, Kmr, Telr | This study |

| E. coli | ||

| DH10B | Host for E. coli plasmids | 10 |

| CC1118(λpir) | Host for pUT-derived plasmids | 12 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pVTR-B | lacIq, Cmr, pSC101 derivative | 22 |

| pUC18 | Apr; cloning vector | 38 |

| pUC18Not | Apr, pUC18 derivative, NotI-flanking MCSa | 12 |

| pUJ9 | Apr; promoterless lacZ vector | 1 |

| pUT-Km | Apr; mini-Tn5 delivery plasmid with Kmr | 1 |

| pUT-Tc | Apr; mini-Tn5 delivery plasmid with Tcr | 1 |

| pJMT6 | Apr; mini-Tn5 delivery plasmid with Telr | 27 |

| pGEc405 | phaC1, pJRD215 derivative, Apr, Smr, Kmr | 14 |

| pPG13 | Apr pUJ9 derivative, PcI::lacZ | This study |

| pPG132 | Apr Kmr pUT-Km derivative, PcI::lacZ | This study |

| pNO6 | Apr, Tcr, pUC18Not derivative; 13-kb NotI cassette containing pha cluster and flanking regions from P. oleovorans GPG-Tc6 phaF::mini-Tn5Tc | This study |

| pPF1 | Apr, pUC18Not derivative; 12.5-kb NotI cassette containing pha locus and flanking regions from P. oleovorans GPo1 | This study |

| pPF3 | Apr, pUC18Not derivative phaF, phaI, ORF1, ORF3, and truncated ORF2 | This study |

| pPF4 | Apr, pUC18 derivative, phaF | This study |

| pPF6 | Cmr, pVTR-B derivative, lacIq-Ptrc::phaF | This study |

| pPF61 | Apr Telr, pJMT6 derivative, lacIq-Ptrc::phaF | This study |

MCS, multiple cloning site.

DNA and RNA manipulations.

DNA and RNA manipulations and other molecular biology techniques were essentially performed as described (26). Transformation of Escherichia coli cells was carried out by using the RbCl method or by electroporation (Gene Pulser; Bio-Rad) (5). To amplify the PcI promoter region by PCR, 10 ng of plasmid pGEc405 (Table 1) and the following primers were used: PolEcoRI (5′-AATCCAGGGGAATTCCTGCGCGTGCACTC-3′) and PolBamHI (5′-AACGACGGGATCCATCTACGACGCTCCGTTGTCC-3′). Original RBS and start codon are indicated in boldface letters. The engineered BamHI site is underlined. Insertion of minitransposon elements into the chromosome of the target strains was done with the filter-mating technique (12). Northern blot, Southern blot, and colony hybridization analyses were performed as previously described (26) by using, as a probe, DNA fragments labeled with digoxigenin with a Dig Luminescent Detection kit or PCR DIG Probe Synthesis kit (Boehringer Mannheim). The name of each probe indicates the name of the gene for which the DNA fragment of the probe codes. Probe C1 (Fig. 1) was generated by PCR amplification by using chromosomal DNA of P. oleovorans GPo1 as template and the primers NC1 (5′-GATCGATCGGATCCCGGTACTCGTCTCAGGACAACGGAGCGTCGTAGATG-3′) and CC1 (5′-GATCGATCGGTACCTGAAATGAACACCGTGGCGTCCCGCAGGTGGC C-3′). Probe DF was prepared by digesting pNO6 plasmid (Table 1) with BbsI and isolating the 1.3-kb generated fragment. Probe F (Fig. 1) contained a 0.86-kb XhoI fragment of pPF3. Probe I (Fig. 1) was generated by using the plasmid pPF3 as template and the primers E3 (5′-TCCTGCTCTCCTTATGGTTTGTGC-3′) and E5 (5′-ATGAAGACTCGCGACCGTATCCTC-3′).

Nucleotide sequences were determined directly from plasmids by using the Taq DNA polymerase-initiated cycle sequencing reactions with fluorescence-labeled primers and dideoxynucleotide terminators in a LICOR automated DNA sequencer with BaseImagIR version 2.3 software (MWG, Biotech). Templates for sequencing were obtained by deletion subcloning. DNA fragments were purified by standard procedures with Gene Clean (BIO 101, Inc.). Protein sequence similarity searches and sequence alignments were carried out with the Baylor College of Medicine-Human Genome Center server.

Batch fermentation media.

Unless otherwise stated, bacteria were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (26) at 30°C with vigorous shaking. The appropriate selection markers kanamycin (50 μg/ml), streptomycin (50 μg/ml), tetracycline (12.5 μg/ml), ampicillin (100 μg/ml), and tellurite (60 μg/ml) were added when needed. E2 minimal medium supplemented with 0.1% (vol/vol) MT microelement solution (17) containing 7.5 mM octanoic acid or 10 mM glucose as the carbon source was used for β-galactosidase measurements. For PHA production and PHA granule isolation, cells were cultured overnight under nitrogen-limited conditions by using 0.1 N E2 minimal medium plus 15 mM octanoic acid (14).

Continuous culture conditions and media.

For chemostat cultures a 3-liter reactor was used with a working volume of 1 liter and equipped as described previously (37). The cells were precultured overnight at 30°C in 500-ml Erlenmeyer flasks containing 100 ml of E2 minimal medium supplemented with 10 mM citric acid and kanamycin. The preculture was used to inoculate 1 liter of continuous culture medium containing 8.35 mM (NH4)2SO4, 7.4 mM KH2PO4, 1 mM MgSO4, 10 μM FeSO4, and 0.1% (vol/vol) MT microelement solution (11). The carbon sources and carbon/nitrogen (C/N) ratio were varied as indicated. The standard culture conditions were pH 7 at 30°C with an agitation of 1,500 rpm constantly and air supplied at a rate of 1.4 liters min−1. The pH was automatically controlled by adding 4 N sodium hydroxide. The dissolved oxygen tension (DOT) was monitored with an in situ amperometric polarographic Ingold oxygen sensor (Mettler Toledo) with an “S”-type membrane (silicon) and was always maintained above 30% saturation. After inoculation, the culture was grown in batch mode to a density of 1.0 g liter−1 and was then switched to continuous operation at a dilution rate of 0.2 h−1. Steady state was assumed when the optical density of the culture at 450 nm and the DOT were constant for at least three mean residence times.

Analytical procedures.

Cell densities expressed as milligrams of cell dry weight (CDW) per milliliter were determined gravimetrically by using tared 0.2-μm-pore-size filters (Corning, Acton, Mass.) (36). Residual biomass is defined as PHA-free CDW. Residual nitrogen concentration in the culture broth was determined by using a CADAS 30 photometer and LCK 304 kit (Dr. Lange GmbH). The citric acid concentration was monitored spectrometrically with the Boehringer Mannheim citric acid determination kit (Boehringer Mannheim). The octanoic acid concentration was determined by gas chromatography (5890 series II plus gas chromatograph; Hewlett-Packard) on a Permabond CW20M column (Macherey-Nagel) with butyric acid used as an internal standard. For PHA content determination, about 4 mg of lyophilized cells was analyzed by the method of Lageveen et al. (17). A CP-Sil 5CB column (Chrompack) was applied to identify the methanolized PHA monomers by gas chromatography. Assay of β-galactosidase activity was performed as described previously (21). One unit of β-galactosidase activity is defined as 1 μmol of o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (ONPG) hydrolyzed per mg of residual biomass per min.

Granule isolation and analysis of GAP.

PHA granules were isolated on a sucrose gradient as reported before (16). Samples of purified granules were mixed 1:1 (vol/vol) with sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) loading buffer, and the bound proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE as described (26). The proteins were directly electroblotted from an SDS-PAGE gel onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The amino-terminal sequences were determined by Edman degradation with a Hewlett-Packard G 1000 A automated protein sequencer.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence reported in this work has been submitted to the GenBank/EMBL databank (accession no. AJ010393).

RESULTS

Construction of PcI::lacZ translational fusion.

To construct a translational fusion of the phaC1 promoter region (designated PcI in Fig. 1) and the lacZ reporter gene, a 577-bp DNA fragment containing the upstream phaC1 gene region of P. oleovorans GPo1 was amplified by PCR. The amplification primers were designed to conserve the start codon of the phaC1 gene and the original RBS (see Materials and Methods). The amplified fragment was cut with EcoRI and BamHI endonucleases and ligated into the promoterless lacZ vector pUJ9, to create the plasmid pPG13 (Table 1). The PcI::lacZ translational fusion in pPG13 was verified by sequence analysis. Plasmid pPG132 (Table 1) was constructed by subcloning the NotI cassette of pPG13 into the mini-Tn5 delivery plasmid pUT-Km (Table 1) and used for the stable insertion of the PcI::lacZ fusion into the chromosome of P. oleovorans GPo1. One of the transconjugant colonies, referred to hereinafter as P. oleovorans GPG132 (Table 1), was further analyzed.

Influence of carbon sources and nitrogen limitation on the expression driven by PcI.

The P. oleovorans GPG132 strain carrying a chromosomal PcI::lacZ translational fusion showed a blue phenotype when cultured in E2 minimal medium plates supplemented with the indicator X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) and 7.5 mM octanoic acid as the sole carbon and energy source. In contrast, when 10 mM citrate or glucose was supplied by addition to the medium, the colonies showed a white phenotype. These results strongly suggested that the expression driven by the PcI promoter region is not constitutive in the original host strain. As pointed out before, PHA production in P. oleovorans is dependent on nutrient-limited growth conditions and on the type of carbon source supplied. To determine whether these growth factors influence the expression driven by the PcI promoter region, P. oleovorans GPG132 was grown in chemostat culture (at a dilution rate of 0.2 h−1) on mineral salts containing a fixed amount of nitrogen (230 mg liter−1) and concentrations of carbon source to give C/N ratios varying from 4 to 15 (Table 2). The β-galactosidase activity and PHA content were determined for every steady-state condition and compared. According to the results shown in Table 2, the presence of octanoic acid in the culture medium led to an activation or derepression of the PcI promoter region. In contrast, the reporter fusion was repressed when citrate was supplied in the culture medium. Dual nitrogen and carbon limitation (C/N ratio of 10) with octanoic acid as the carbon source increased the β-galactosidase activity produced by P. oleovorans GPG132 1.5-fold. This effect could be due to the double stress situation or to nitrogen limitation only. The data obtained when the cells were cultured only under nitrogen-limiting conditions (C/N ratio of 15) confirmed that the activity driven by the PcI promoter region is slightly susceptible to nitrogen-limited growth conditions. As described previously (17), the cellular PHA content is strictly dependent on the presence of octanoic acid and increases under nitrogen-limited conditions (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Induction of PcI::lacZ fusion and PHA production by P. oleovorans GPG132 and GPG-Tc6 in continuous culture

| Strain | Carbon source | C/N ratio | Biomass (g · liter−1) | Residual nitrogen (mg · liter−1) | Residual carbon (mg · liter−1) | β-Galactosidase (U) | PHA (% of CDW) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPG132 | Citrate | 4 | 0.66 ± 0.07 | 126 ± 3 | <0.01 | 75 ± 5 | <0.01 |

| GPG132 | Octanoate | 4 | 0.85 ± 0.05 | 108 ± 5 | <0.01 | 306 ± 9 | 4 ± 0.5 |

| GPG132 | Octanoate | 10 | 1.90 ± 0.08 | <0.5 | <0.01 | 462 ± 45 | 19 ± 10 |

| GPG132 | Octanoate | 15 | 2.10 ± 0.10 | <0.5 | 570 ± 10 | 502 ± 23 | 43 ± 20 |

| GPG-Tc6 | Citrate | 4 | 0.67 ± 0.30 | 169 ± 4 | <0.01 | 380 ± 1 | <0.01 |

| GPG-Tc6 | Octanoate | 4 | 0.88 ± 0.03 | 128 ± 3 | <0.01 | 373 ± 5 | 5 ± 1 |

| GPG-Tc6 | Octanoate | 15 | 1.66 ± 0.50 | <0.5 | 880 ± 10 | 525 ± 1 | 15 ± 8 |

Isolation and characterization of the phaF mutant of P. oleovorans GPG132.

To characterize genes involved in the regulation of the expression of the pha gene cluster, a mini-Tn5 insertional mutagenesis was carried out by using Escherichia coli CC118(λpir)(pUT-Tc) and P. oleovorans GPG132 as donor and recipient strains, respectively (Table 1). The selection of mutants was based on the inability of P. oleovorans GPG132 to activate PcI::lacZ expression when grown in the presence of citric acid. This approach allowed us to isolate P. oleovorans GPG-Tc6 showing a blue phenotype when cultured with X-Gal independently of the carbon source supplied to the medium.

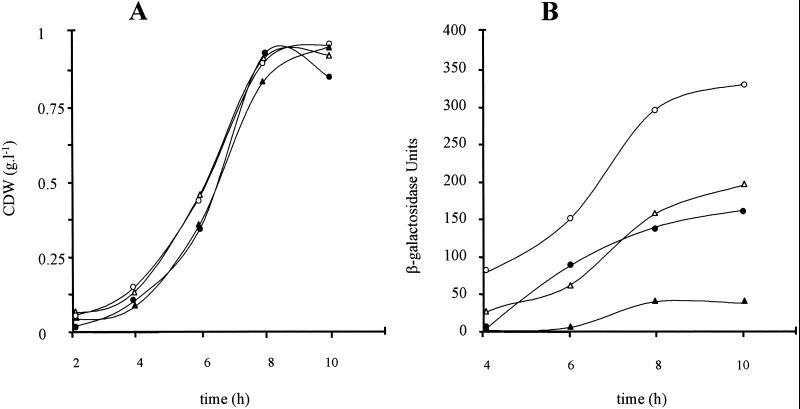

Several genomic libraries of P. oleovorans GPG-Tc6 constructed in pUC18Not (Table 1) were transformed in E. coli DH10B (Table 1), and the transformants were screened for tetracycline resistance. By this approach the plasmid pNO6 containing a 13-kb NotI fragment was isolated. Partial sequencing with a primer which hybridized just downstream of the I end of mini-Tn5Tc allowed us to localize the mobile element of the pUT-Tc plasmid inserted 675 bp downstream of the phaD gene (Fig. 1), knocking out the phaF reading frame. The effect of disruption of the phaF gene on PcI::lacZ expression in P. oleovorans GPG-Tc6 was analyzed by comparing the β-galactosidase activity produced by this strain and that of P. oleovorans GPG132 when grown in E2 minimal medium supplemented with octanoic acid or glucose. Preliminary experiments performed with the GPG132 strain showed large differences in generation time when cells were exposed to nitrogen limitation in the presence of various carbon sources. Therefore, in order to compare cultures at similar phases of growth, we performed the analysis under non-nitrogen starvation conditions in which the cells grew at similar rates (Fig. 2A). Figure 2 clearly shows that the expression of the reporter gene controlled by the PcI promoter region is enhanced in the P. oleovorans GPG-Tc6 strain lacking a functional phaF gene.

FIG. 2.

Expression of PcI::lacZ translational fusion and phaC1 mRNA analysis in P. oleovorans GPG132 and GPG-Tc6. (A) Growth curves of GPG132 strain in E2 medium plus 7.5 mM octanoic acid (•) or 10 mM glucose (▴) and GPG-Tc6 strain in 7.5 mM octanoic acid (○) or 10 mM glucose (▵). (B) β-Galactosidase levels of GPG132 growing in octanoic acid (•) or glucose (▴) and GPG-Tc6 strain growing on octanoic acid (○) or glucose (▵). (C) phaC1 mRNA levels analyzed by Northern blot probing with C1 DNA fragment (see Materials and Methods). Positions of RNA size markers (in kilobases) are shown. Cells were harvested from exponentially growing cultures after 7 h of growth. Each slot was loaded with 10 μg of total RNA isolated from the following: lane 1, GPG-Tc6 grown on glucose; lane 2, GPG-Tc6 cultured on octanoic acid; lane 3, GPG132 grown on glucose; lane 4, GPG132 grown on octanoic acid.

PhaC1 mRNA levels were analyzed by Northern blot using probe C1 (see Materials and Methods and Fig. 1) to assess whether the β-galactosidase levels determined in this experiment reflected the transcriptional state of the corresponding PcI transcript(s) (Fig. 2). Probing for transcript of phaC1 revealed a major hybridization band of approximately 2 kb, a weak band of 2.7 kb, and a large smear indicating mRNA degradation. Our mRNA analysis data showed no transcripts larger than 3 kb, suggesting that phaC1, phaZ, phaC2, and phaD do not form part of the same transcription unit, although an mRNA processing event cannot be completely excluded. The 2.7-kb transcript was also detected when a probe containing an internal fragment of the phaZ gene was used for hybridization, whereas the 2-kb band was detected only when probed with C1 DNA fragment (data not shown). According to these data phaC1 and phaZ might be transcribed in the same unit as reported for the homologous system of P. aeruginosa (32). Thus, part of the transcript stops at the end of the phaC1 gene (2-kb band), while part continues to the end of phaZ (2.7-kb band). The intensities of both hybridization bands were clearly increased in P. oleovorans GPG-Tc6 when compared to that of GPG132, so that phaZ expression might also be affected in the GPG-Tc6 strain.

PHA content was determined by culturing the mutant and the parental strains under nitrogen limitation in 0.1 N E2 minimal medium with octanoate for 20 h. Under these conditions the amounts of PHA produced by both GPG132 and GPG-Tc6 strains were similar (33 to 35% of CDW). Furthermore, the observation of PHA granules in both strains by phase-contrast microscopy did not show significant differences in number and size (data not shown). Considering all results obtained in batch fermentation, we can conclude that the lack of the phaF gene derepresses the expression of the phaC1 gene in the exponential phase under nonlimited growth conditions but does not affect final PHA production when nitrogen limitation is applied.

The expression of the reporter fusion in GPG-Tc6 strain was also analyzed in continuous culture (Table 2). When citric acid was used as the carbon source, this strain produced higher levels of β-galactosidase than GPG132, supporting the results obtained in batch fermentation (Fig. 2). However, the phaF mutant produced approximately threefold less PHA than the GPG132 strain when the cells were exposed to nitrogen limitation and excess of octanoic acid, despite the fact that the PcI::lacZ expression level was not affected (Table 2).

Cloning and sequencing of the complete phaF gene and flanking regions.

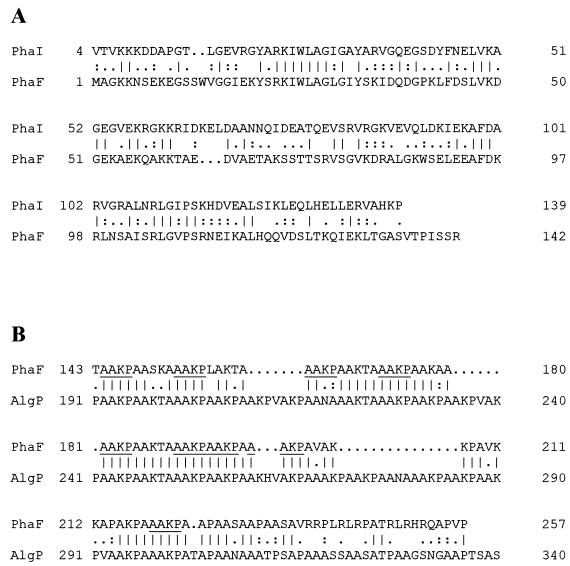

To clone the complete wild-type phaF gene, various gene libraries of chromosomal DNA of P. oleovorans GPo1 were constructed in pUC18Not. The recombinant plasmid pPF1 containing a 12.5-kb NotI DNA fragment was identified by colony blot hybridization by using probe DF for detection (see Materials and Methods). A 2.38-kb NotI-MunI DNA fragment was subcloned into the pUC18Not plasmid cut with NotI and EcoRI restriction endonucleases, resulting in the plasmid pPF3 (Table 1). To characterize the phaF gene, the 2.38-kb insert of plasmid pPF3 was sequenced. Computer analysis of this sequence revealed the presence of three complete ORFs (phaF, phaI, and ORF1) and the truncated ORF2 and phaD gene. The phaF and phaI genes code for two putative proteins with deduced molecular masses of 26.3 and 15.4 kDa, respectively. The genes are separated by 10 nucleotides and the putative RBS of phaF overlaps with the stop codon of the phaI gene. The proposed putative transcriptional terminator (ΔG = −80 kcal) for the phaD gene (15) (Fig. 1) is the only palindromic sequence found downstream of the phaF gene, and it might also act as a transcriptional terminator for this gene.

The alignments shown in Fig. 3 suggest that the PhaF protein is organized in two different domains. The C-terminal half contains the AAKP motifs that characterize the members of the histone H1-like family of proteins (20). It is similar to the AlgP protein, which is the best-studied member of this prokaryotic protein family (2). Due to the particular composition of this C-terminal domain, the amino acid composition of the total protein is unusual because it contains high levels of lysine (15%), alanine (25%), and proline (8.2%). Comparison of the nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences in the 5′-terminal region of the phaF gene product with those deposited in different databanks did not reveal a significant overall similarity to any other gene or protein sequence. A similar result for deduced protein sequence was observed for the phaI-encoded protein. Surprisingly, comparison of the deduced amino acid sequences of phaI and phaF gene products showed 58.6% similarity (Fig. 3B), suggesting that these proteins are related.

FIG. 3.

Amino acid sequence alignment of PhaF protein. (A) Alignment of the PhaF N-terminal half with PhaI protein. (B) Alignment of PhaF C-terminal half with the last 150 residues of the C-terminal domain of AlgP of P. aeruginosa (2). AAKP repeat units of PhaF are underlined. Alignments were done with the BESTFIT program.

ORF1 codes for a protein of 132 residues and is transcribed in orientation opposite to that of phaF and phaI. The amino acid sequence of the ORF1-derived protein is not similar to any sequence described so far. In contrast, the truncated ORF2 codes for a peptide which is 71% identical to the UbiE protein of E. coli (176 amino acids were compared), a methyltransferase involved in the synthesis of ubiquinone and menaquinone (18). Since ORF1 and ORF2 are separated by only 19 bp they could form part of the same transcription unit. Interestingly, an additional ORF3 (data not shown) is located at the same position as ORF1 but on the complementary strand, and it could also code for a putative protein. The amino acid sequence deduced from this ORF3 is also not similar to any other known protein. Whether all these putative proteins are involved in PHA biosynthesis has to be demonstrated.

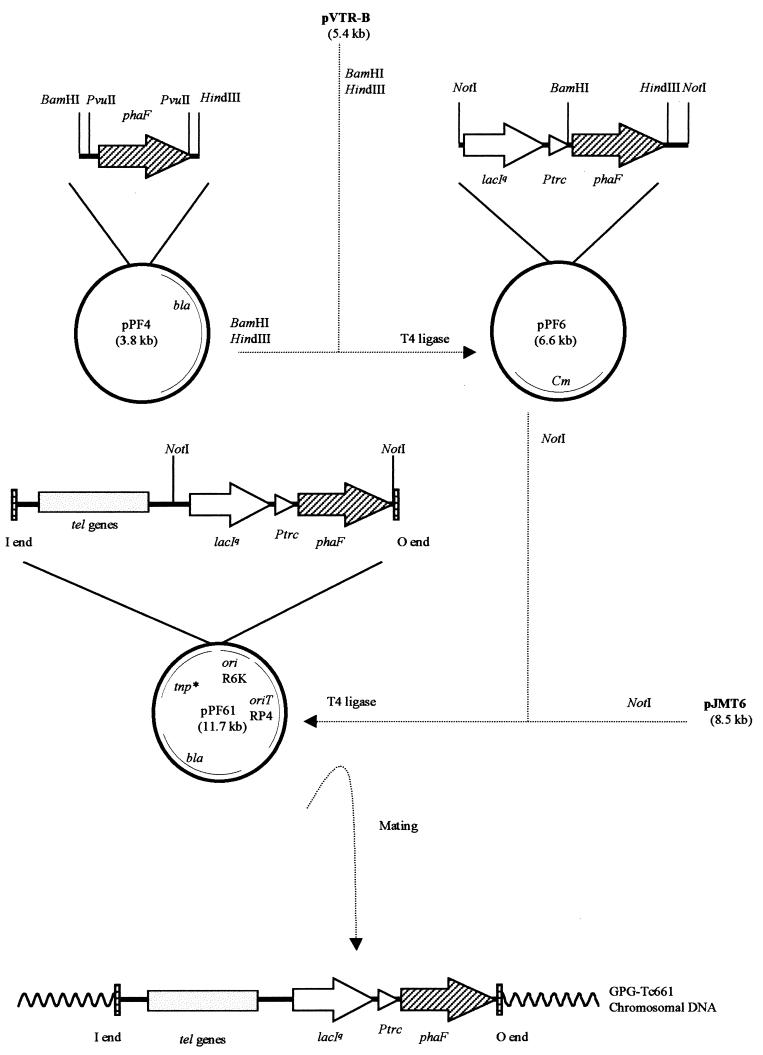

Expression of wild-type phaF gene in strain GPG-Tc6.

To demonstrate that phaF encodes a regulatory protein involved in the expression of phaC1 and that the phenotype observed in the mutant was not due to a polar mutation, we generated the new strain, GPG-Tc661, which is a derivative of GPG-Tc6 (Table 1, Fig. 4) but with a single copy of the complete wild-type phaF gene in the chromosome. The aims of this experiment were to analyze the expression of the reporter lacZ fusion in GPG-Tc661 after complementation with the phaF gene and to ascertain whether this new recombinant regains the phenotype of the parental strain, GPG132. The complementation of GPG-Tc6 was performed as follows (Fig. 4). First, we constructed plasmid pPF4 (Table 1) by subcloning into pUC18 (Table 1) a 1.16-kb PvuII DNA fragment containing only the phaF gene from plasmid pPF3. The new plasmid pPF4 was then digested with BamHI and HindIII endonucleases and ligated to the pVRT-B expression vector (Table 1). The resulting plasmid, pPF6, contained a NotI cassette in which the phaF gene was expressed under the control of the trc promoter (Table 1). The cassette was further subcloned into the mini-Tn5 delivery plasmid pJMT6, resulting in plasmid pPF61 (Table 1). The latter was then used to transfer by mating a monocopy of the wild-type phaF gene into the chromosome of P. oleovorans GPG-Tc6 (Fig. 4). As expected, the generated strain GPG-Tc661 regained the ability to silence the PcI promoter region when glucose was supplied as the carbon source (Table 3). The β-galactosidase levels determined when the cells were growing on octanoic acid were similar to those of the GPG132 strain, confirming that PhaF is involved in the regulation of phaC1 gene expression.

FIG. 4.

Construction of P. oleovorans GPG-Tc661 strain. Abbreviations: tel, tellurite resistance genes; bla, ampicillin resistance; Cm, chloramphenicol resistance; Ptrc, trc promoter; tnp*, Tn5 transposase. The 19-bp I and O Tn5 ends, the oriT RP4 and the ori R6K are indicated.

TABLE 3.

Complementation studies of P. oleovorans GPG-Tc6

| Strain | phaF | C source | CDW (mg/ml) | β-Galactosidasea (U) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPG132 | + | Octanoate | 0.88 | 142 ± 4 |

| Glucose | 0.74 | 39 ± 4 | ||

| GPG-Tc6 | − | Octanoate | 0.88 | 298 ± 12 |

| Glucose | 0.75 | 158 ± 0.6 | ||

| GPG-Tc661 | + | Octanoate | 0.86 | 195 ± 4 |

| Glucose | 0.75 | 21 ± 5 |

Cells were cultured for 8 h (CDW = 0.8 mg/ml) before β-galactosidase activity assay was performed.

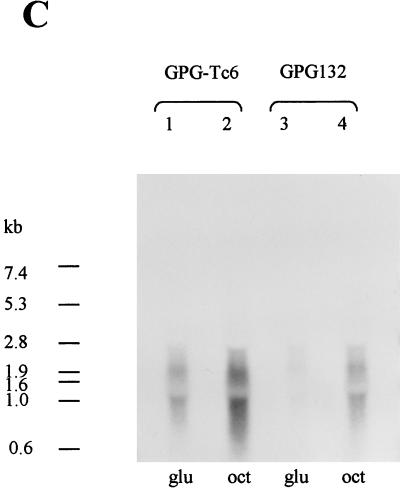

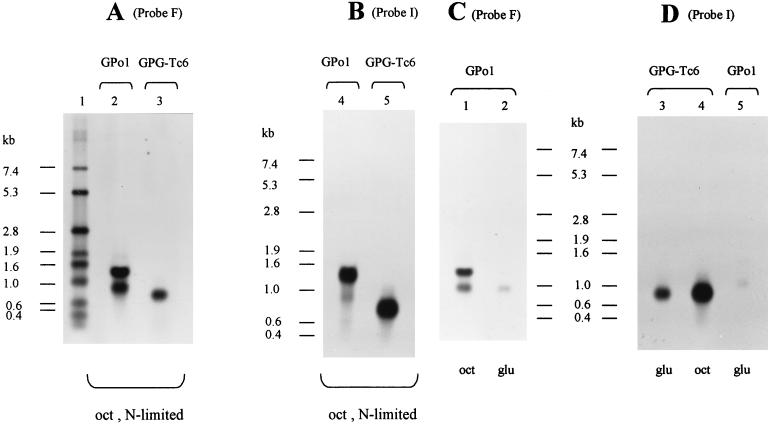

mRNA analysis of phaF and phaI genes.

The genetic arrangement of the phaI and phaF sequences suggested a possible cotranscription of these genes. The expression of these genes was investigated by Northern blot analysis of total RNA extracted from P. oleovorans GPo1 and GPG-Tc6 strains (Fig. 5). First, we analyzed total RNA isolated from exponentially growing cultures in 0.1 N E2 minimal medium supplied with an excess of octanoic acid (Fig. 5A and B). Northern blots were probed with the DNA fragments F and I, which contain internal DNA regions of the phaF and phaI genes, respectively (see Materials and Methods and Fig. 1). Two transcripts of 1.35 and 0.9 kb were detected when the RNA extracted from GPo1 was probed with fragment F (Fig. 5A, lane 2). The hybridizing band of 1.35 kb perfectly matches a transcription unit encompassing the phaIF genes, whereas the 0.9-kb transcript may correspond to phaF mRNA. This hypothesis was confirmed by probing the membranes with fragment I (Fig. 5B, lane 4). In this case, the band corresponding to the phaIF transcript of 1.35 kb was much more intense than the band of 0.9 kb. The weak 0.9-kb band seen with probe I could be interpreted as a weak hybridization between probe I and phaF mRNA due to the nucleotide sequence identity between the phaI and phaF genes. The lengths of both transcription units are in agreement with the existence of a putative transcriptional terminator located downstream of the phaF gene (Fig. 1). These results suggest the possible presence of two promoters, one located upstream of the phaI gene and the other located upstream of phaF. However, no sequences resembling a consensus promoter have been found upstream of phaF or phaI, and as long as the existence of these two active promoters is not shown experimentally, the possibility that the smallest band is the result of RNA degradation or processing cannot be ruled out. Regarding the phaF mutant, the expected corresponding bands were detected when total RNA from GPG-Tc6 was analyzed (Fig. 5A, lane 3, and Fig. 5B, lane 5). Since the mini-Tn5Tc contains a transcriptional terminator at each end (1), i.e., transcription stops at the insert, the 0.75-kb band should correspond to the truncated phaIF (phaIF::mini-Tn5Tc) transcript. These results were confirmed by probing the Northern blots with fragment I (Fig. 5B, lane 5).

FIG. 5.

Transcription of phaIF operon under different conditions of growth. Membranes were hybridized with F probe (A) and I probe (B). Each well was loaded with 10 μg of RNA. Total RNAs were isolated from exponentially growing cells after 7 h of growth in 0.1 N E2 medium (N-limited) plus 15 mM octanoic acid from GPo1 strain (lanes 2 and 4) and from GPG-Tc6 (lanes 3 and 5). Northern blot probed with F (C) and I (D) DNA fragments by using 10 μg of RNA isolated from cells of GPo1 (lanes 1, 2, and 5) or GPG-Tc6 (lanes 3 and 4) grown 7 h in E2 medium supplemented with 7.5 mM octanoic acid (lanes 1 and 4) or 10 mM glucose (2, 3, and 5). Positions of RNA size markers (in kilobases) are shown.

Transcription of the phaIF operon under non-limited conditions.

We have shown above that the expression of the phaC1 gene is dependent on the carbon source supplied in the medium. Moreover, phaF seems to repress the expression of the PcI promoter region. Hence, phaF should be expressed when carbon sources like glucose or citric acid are used. In order to study the transcription of the phaF gene under repressing conditions, we determined by Northern blot analysis the presence of phaIF and phaF transcripts in cells growing in glucose under non-limited conditions (Fig. 5C and D). The hybridization patterns of total RNA from GPo1 cells grown in octanoic acid with and without nitrogen limitation were identical (Fig. 5). However, when GPo1 was cultured in glucose, only a weak signal from the small phaF transcript was detected (Fig. 5C, lane 2, and Fig. 5D, lane 5). These data suggest the existence of a separate regulatory system for each transcription unit. Surprisingly, when expression of the phaIF transcript in GPG-Tc6 was determined, the band corresponding to the phaIF::miniTn5Tc transcript was detected when glucose was used as the sole carbon source (Fig. 5D, lane 3). These data strongly suggested that in the experiments with GPo1 the expression of the phaIF operon is repressed by PhaF.

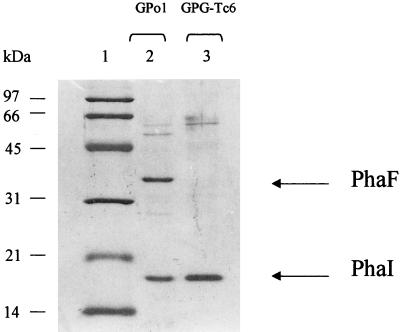

Identification of PhaI and PhaF as GAP.

Although no data have been reported for the function of PhaF, indications that it could be associated with the PHA granules came from the N-terminal sequencing of PHA GAP of P. putida KT2442 (21a, 32a). In fact, the N-terminal domain of a P. putida 36-kDa GAP showed significant similarity with the P. oleovorans PhaF protein. To confirm the presence of PhaF in the granules, two different preparations containing PHA granules from P. oleovorans GPo1 and GPG-Tc6 were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 6). The protein pattern observed in the granule preparation of the wild-type strain resembles the characteristic protein pattern described previously by Wieczorek et al. (35) for the predominant GAP in P. oleovorans of 18 and 35 kDa. The 35-kDa protein was not detected in the granule suspension of GPG-Tc6, suggesting that it could correspond to PhaF or to another protein, the production of which could be affected by the lack of phaF. By determining the N-terminal amino acid sequence of the two major proteins, we found that the 35-kDa protein N-terminal sequence was identical to the PhaF sequence deduced from the nucleotide data and that the 18-kDa band corresponded to PhaI protein. The high content of charged amino acids in PhaF could explain the discrepancy observed between the molecular mass value calculated by SDS-PAGE and the data deduced from the nucleotide sequence analysis. Such discrepancies have been observed previously for other histone-like proteins (3, 28).

FIG. 6.

SDS-PAGE analysis of purified PHA granules of P. oleovorans GPo1 and GPG-Tc6 strains. Proteins from the purified inclusion bodies were separated on SDS–12% PAGE gels. Cells were cultured for 20 h in 0.1 N E2 medium supplied with 15 mM octanoic acid. Lane 1, molecular weight markers; lane 2, GAP of P. oleovorans GPo1; lane 3, GAP of P. oleovorans GPG-Tc6. The positions of the PhaI and PhaF proteins are indicated. The molecular masses of the marker proteins are shown in kilodaltons.

DISCUSSION

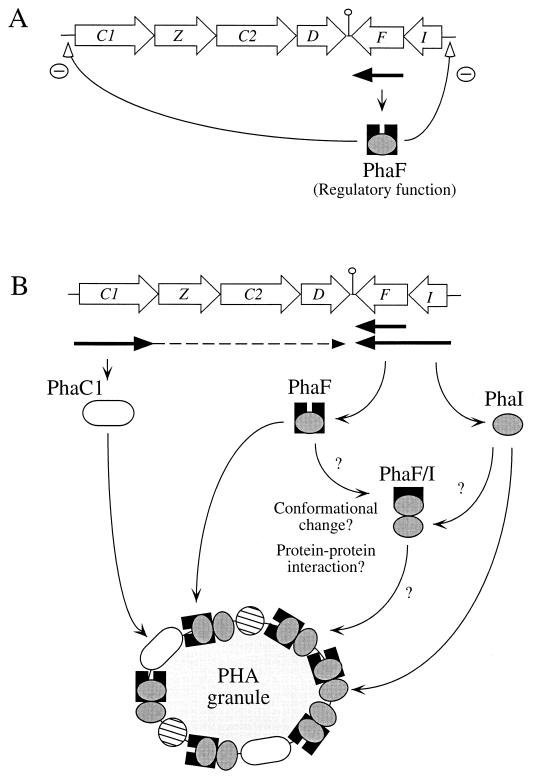

A novel and peculiar regulatory protein from P. oleovorans GPo1 has been identified in this study. First, we studied the environmental conditions that influence the expression driven by the PcI promoter region and concluded that, besides nitrogen limitation, activation of the PcI promoter region is susceptible to the carbon source present in the medium. When citric acid or glucose is used as the carbon source, PcI is less active than in the presence of octanoic acid. This response could have evolved as a mechanism of defense against the wasteful production of PHA-associated proteins in the absence of an appropriate substrate, since P. oleovorans can accumulate PHA only in the presence of fatty acids, alkanes, or other PHA-monomer-related substrates. Disruption of the phaF gene leads to an increase of the expression rate of the phaC1 gene (Fig. 2), suggesting that this protein behaves as a negative regulator of phaC1 gene expression. The primary structure of the PhaF protein appears to be organized in two domains. The regulatory function of PhaF is likely related to the C-terminal domain, which contains nine copies of an AAKP repeating unit, the consensus motif characteristic of prokaryotic histone H1-like proteins (Fig. 3). Of several examples (8, 9, 28), the best-characterized naturally occurring member of this group of proteins is the AlgP regulatory protein of P. aeruginosa (2, 3, 20). AlgP is considered to be part of a complex mechanism which regulates alginate production in P. aeruginosa in response to certain environmental signals. Those signals are the same as those which promote PHA accumulation in bacteria, such as nitrogen availability (2, 32). Our data suggest that PhaF is a histone H1-like protein which represses the expression of phaC1, phaI, and its own transcription. Whether this regulator forms part of a complex regulatory system similar to that of alginate synthesis in P. aeruginosa remains to be investigated. The N-terminal domain of PhaF showed a significant degree of similarity with the PhaI protein (Fig. 3A). Since both proteins are attached to PHA granules, we suggest that the ability to bind to PHA granules could be ascribed to the N-terminal domain of PhaF. Three major classes of GAP have been identified in bacteria: PHA synthases, PHA depolymerases, and phasins (7, 31, 35). The latter have been identified in Ralstonia eutropha (34), Chromatium vinosum D (19), Rhodococcus ruber (23, 24) and Acinetobacter spp. (29), and they usually represent the major components of the GAP. These proteins appear to have a function similar to that of oleosins in triacylglycerol inclusions in seeds and pollen of plants, forming a protein layer at the surface of the granules as part of the interface between the hydrophilic cytoplasm and the hydrophobic core of the PHA inclusion (31). Strains lacking phasins usually are leaky PHA mutants which produce PHA granules altered in their number and size (34). The lack of the PhaF protein in P. oleovorans GPG-Tc6 did not affect the PHA content and granule formation when the cells were cultivated in batch fermentation under nitrogen-limited growth conditions. However, in continuous culture under nitrogen limitation, the PHA content of GPG-Tc6 was reduced threefold in comparison to that of GPG132. In contrast to the later stages of PHA formation in batch fermentation, cells are dividing while PHA is formed in continuous cultures. How granules are generated in newly formed cells under these conditions is still an open question. We cannot exclude the possibility that the lack of PhaF could affect granule formation. In addition, the lack of the PhaF protein could cause other effects which might affect the PHA biosynthesis pathway in GPG-Tc6, promoting an increase in depolymerase production or modifying phaC2 expression.

Taking together these observations and the fact that the deduced amino acid sequences of PhaF and PhaI proteins did not show significant similarities to any other phasin described so far, we cannot be certain that PhaI and PhaF play a structural role in granule formation. However, our data do not exclude the possibility that they could have an additional function apart from the regulatory role of PhaF.

Our findings are summarized in a model depicted in Fig. 7. The phaF gene can be transcribed to generate two different mRNAs, one containing exclusively phaF and the other containing both phaI and phaF genes. The phaF transcript can be observed in the wild-type strain even when glucose is used as the substrate (Fig. 7). Expression of the phaIF transcript appears to be dependent on the presence of octanoic acid in the culture medium. This regulatory system implies a permanent presence of PhaF in the cells (Fig. 7). When glucose or citrate is supplied as the carbon source, PhaF is not attached to granules simply because they are never generated from such substrates in P. oleovorans (13, 25). Under those conditions, PhaF could bind to DNA, turning off the expression of phaC1 (or phaC1Z) and phaIF transcription units (Fig. 7). Although the DNA binding ability of peptides containing AAKP repeats has been sufficiently demonstrated (20), there is no evidence about direct binding of PhaF to the DNA promoter regions of phaC1 or phaIF. Thus, an indirect regulatory effect of PhaF on the expression of the pha genes cannot be excluded. In the presence of octanoic acid PhaF is attached to the granule (Fig. 7) and the transcription rates of phaC1, phaI, and phaF increase significantly. PhaC1 and then also PhaI associate with PHA granules. PhaC1 synthesizes PHA, leading to growth and formation of new granules. The role of PhaI is not yet clear. The crucial feature of this control circuit might reside in the dual properties of the regulator PhaF, namely, that it can prevent transcription and can bind to the granule. The question of whether PHA granules, octanoic acid, or even PhaI protein (Fig. 7) plays an inducer role and changes the conformation of PhaF to a form that is released from the DNA and binds to the granule awaits further research.

FIG. 7.

Hypothetical model for the regulation of pha genes. C1, Z, C2, D, F, and I represent the names of the pha genes. White arrows indicate the directions of transcription of the genes. The phaC1, phaF, and phaIF transcripts are marked as thick black arrows. Discontinuous arrows denote unproved events. The hatched circles bound to the granules denote PhaC2 and PhaZ proteins. (A) Repression of the expression of the phaC1 gene and the phaIF operon when P. oleovorans is cultured in medium containing citrate or glucose as the carbon source. Under these growth conditions phaF is transcribed. (B) Induction of the expression of phaC1, phaI, and phaF genes in the presence of octanoic acid and association with PHA granule.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jose L. García and E. Diaz for helpful comments. We are indebted to P. James for his support in protein sequencing. We also thank M. Röthlisberger and H.-J. Feiten for excellent technical assistance. We are grateful to J. M. Sanchez-Romero, Q. Ren, and S. Panke for some plasmids and strains used in this work.

M. A. Prieto was the recipient of an EMBO long-term fellowship.

REFERENCES

- 1.de Lorenzo V, Herrero M, Jakubzik U, Timmis K N. Mini-Tn5 transposon derivatives for insertion mutagenesis, promoter probing, and chromosomal insertion of cloned DNA in gram-negative eubacteria. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6568–6572. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6568-6572.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deretic V, Konyecsni W M. A procaryotic regulatory factor with a histone H1-like carboxy-terminal domain: clonal variation of repeats within algP, a gene involved in regulation of mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:5544–5554. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.10.5544-5554.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deretic V, Hibler N S, Holt S C. Immunocytochemical analysis of AlgP (Hp1), a histonelike element participating in control of mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:824–831. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.3.824-831.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Smet M J, Eggink G, Witholt B, Kingma J, Wynberg H. Characterization of intracellular inclusion formed by Pseudomonas oleovorans during growth on octane. J Bacteriol. 1983;154:870–878. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.2.870-878.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dower W J, Miller J F, Ragsdale C W. High efficiency transformation of Escherichia coli by high voltage electroporation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:6127. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.13.6127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drlica K, Rouviere-Yaniv J. Histonelike proteins of bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1987;51:301–319. doi: 10.1128/mr.51.3.301-319.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuller R C, O’Donnel J P, Saulnier J, Redlinger T E, Foster J, Lenz J W. The supramolecular architecture of the polyhydroxyalkanoate inclusions in Pseudomonas oleovorans. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1992;103:279–288. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goyard S. Identification and characterization of BpH2, a novel histone H1 homolog in Bordetella pertussis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3066–3071. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.11.3066-3071.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hackstadt T, Brickman T J, Barry III C E, Sager J. Diversity in the Chlamydia trachomatis histone homologue Hc2. Gene. 1993;132:137–141. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90526-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanahan D. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmid. J Mol Biol. 1983;166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hazenberg W M. Production of poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates) by Pseudomonas oleovorans in two-liquid-phase media. Ph.D. thesis. Zürich, Switzerland: ETH; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herrero M, de Lorenzo V, Timmis K N. Transposon vector containing non-antibiotic resistance selection markers for cloning and stable chromosomal insertion of foreign genes in gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6557–6567. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6557-6567.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huijberts G N M, Eggink G, de Waard P, Huisman G W, Witholt B. Pseudomonas putida KT2442 cultivated on glucose accumulates poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates) consisting of saturated and unsaturated monomers. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:536–544. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.2.536-544.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huisman G W, Wonink E, de Koning G J M, Preusting H, Witholt B. Synthesis of poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates) by mutant and recombinant Pseudomonas strains. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1992;38:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huisman G W, Wonink E, Meima R, Kazemier B, Terpstra P, Witholt B. Metabolism of poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates) (PHAs) by Pseudomonas oleovorans. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:2191–2198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kraak M N, Smits T H M, Kessler B, Witholt B. Polymerase C1 levels and poly(R-3-hydroxyalkanoate) synthesis in wild-type and recombinant Pseudomonas strains. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4985–4991. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.16.4985-4991.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lageveen R G, Huisman G W, Preusting H, Ketelaar P, Eggink G, Witholt B. Formation of polyesters by Pseudomonas oleovorans: effect of substrates on formation and composition of poly-(R)-3-hydroxyalkanoates and poly-(R)-3-hydroxyalkenoates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:2924–2932. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.12.2924-2932.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee P T, Hsu A Y, Ha H T, Clarke C F. A C-methyltransferase involved in both ubiquinone and menaquinone biosynthesis: isolation and identification of the Escherichia coli ubiE gene. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1748–1754. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.5.1748-1754.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liebergesell M, Schmidt B, Steinbüchel A. Isolation and identification of granule-associated proteins relevant for poly(3-hydroxyalkanoic acid) biosynthesis in Chromatium vinosum D. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;99:227–232. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90031-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Medvedkin V N, Permyakov E A, Klimenko L V, Mitin Y V, Matsushima N, Nakayama S, Kretsinger R H. Interactions of (Ala*Ala*Lys*Pro)n and (Lys*Lys*Ser*Pro)n with DNA. Proposed coiled-coil structure of AlgR3 and AlgP from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Protein Eng. 1995;8:63–70. doi: 10.1093/protein/8.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 21a.Passarge, M., and F. van der Leij. Unpublished data.

- 22.Perez-Martin J, de Lorenzo V. VTR-expression cassettes for the engineering conditional phenotypes in Pseudomonas: activity of the Pu promoter of the TOL plasmid under limiting concentrations of the XylR activator protein. Gene. 1996;172:81–86. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00193-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pieper-Fürst U, Madkour M H, Mayer F, Steinbüchel A. Purification and characterization of a 14-kilodalton protein that is bound to the surface of polyhydroxyalkanoic acid granules in Rhodococcus ruber. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4328–4337. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.14.4328-4337.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pieper-Fürst U, Madkour M H, Mayer F, Steinbüchel A. Identification of the region of a 14-kilodalton protein of Rhodococcus ruber that is responsible for the binding of this phasin to the polyhydroxyalkanoic acid granules. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2513–2523. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.9.2513-2523.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Preusting H, Kingma J, Huisman G, Steinbüchel A, Witholt B. Formation of polyester blends by a recombinant strain of Pseudomonas oleovorans: different poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates) are stored in separates granules. J Environ Polym Degrad. 1993;1:11–21. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanchez-Romero J M, Diaz-Orejas R, de Lorenzo V. Resistance to tellurite as a selection marker for genetic manipulations of Pseudomonas strains. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:4040–4046. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.4040-4046.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scarlato V, Arico B, Goyard S, Ricci S, Manetti R, Prugnola A, Manetti R, Polverino-De-Laureto P, Ullmann A, Rappuoli R. A novel chromatin-forming histone H1 homologue is encoded by a dispensable and growth-regulated gene in Bordetella pertussis. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:871–881. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schembri M A, Woods A A, Bayly R C, Davies J K. Identification of a 13-kDa protein associated with the polyhydroxyalkanoic acid granules from Acinetobacter spp. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;133:277–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwartz R D, McCoy C J. Pseudomonas oleovorans hydroxylation-epoxidation system: additional strain improvements. Appl Microbiol. 1973;26:217–218. doi: 10.1128/am.26.2.217-218.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steinbüchel A, Aerts K, Babel W, Föllner C, Liebergesell M, Madkour M H, Mayer F, Pieper-Fürst U, Pries A, Valentin H E, Wieczorek R. Considerations of the structure and biochemistry of bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoic acid inclusions. Can J Microbiol. 1995;41:94–105. doi: 10.1139/m95-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Timm A, Steinbüchel A. Cloning and molecular analysis of the poly(3-hydroxyalkanoic acid) gene locus of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Eur J Biochem. 1992;209:15–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32a.Valentin, H. E. Personal communication.

- 33.van der Leij F R, Witholt B. Strategies for the sustainable production of new biodegradable polyesters in plants: a review. Can J Microbiol. 1995;41:222–238. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wieczorek R, Pries A, Steinbüchel A, Mayer F. Analysis of a 24-kilodalton protein associated with the polyhydroxyalkanoic acid granules in Alcaligenes eutrophus. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2425–2435. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.9.2425-2435.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wieczorek R, Steinbüchel A, Schmidt B. Occurrence of polyhydroxyalkanoic acid granule-associated proteins related to the Alcaligenes eutrophus H16 GA24 protein in other bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;135:23–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb07961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Witholt B. Method for isolating mutants overproducing nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide and its precursors. J Bacteriol. 1972;109:350–364. doi: 10.1128/jb.109.1.350-364.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wubbolts M G, Favre-Bulle O, Witholt B. Biosynthesis of synthons in two-liquid-phase media. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1996;52:301–308. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19961020)52:2<301::AID-BIT10>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]