ABSTRACT

Anaphylaxis is a serious systemic hypersensitivity reaction that is usually rapid in onset and may cause death. It is characterised by the rapid development of airway and/or breathing and/or circulation problems. Intramuscular adrenaline is the most important treatment, although, even in healthcare settings, many patients do not receive this intervention contrary to guidelines. The Resuscitation Council UK published an updated guideline in 2021 with some significant changes in recognition, management, observation and follow-up of patients with anaphylaxis. This is a concise version of the updated guideline.

KEYWORDS: anaphylaxis, adrenaline, antihistamine, corticosteroids, resuscitation

Introduction

The Resuscitation Council UK (RCUK) published an updated guideline in 2021 with some significant changes in the recognition, management, observation and follow-up of patients with anaphylaxis.1 Key updates include a greater emphasis on the use of intramuscular (IM) adrenaline, changes to the role of antihistamines and corticosteroids, the introduction of an algorithm for treating refractory anaphylaxis, and refinement of the duration of observation after anaphylaxis. This is a concise version of the updated guideline.

Anaphylaxis is a serious systemic hypersensitivity reaction that is usually rapid in onset and may cause death.2 The estimated incidence of anaphylaxis from all causes in Europe is 1.5–7.9 per 100,000 person-years, and 1 in 300 people experience anaphylaxis at some point in their lives.3 The overall prognosis of anaphylaxis is good, with a case fatality rate of <1% in those presenting to UK hospitals, and the mortality rate in the general population is <1 per million per annum.4,5 There are approximately 20–30 deaths reported each year due to anaphylaxis in the UK, but this may be a significant underestimate; approximately 10 anaphylaxis deaths each year are due to foods, and another 10 due to perioperative anaphylaxis.6

The most common triggers are food, drugs and venom.4 Food is the most common trigger in young people: teenagers and adults up to the age of 30 years appear to be at greatest risk of fatal food-induced reactions.4,5 In contrast, the rate of drug-induced anaphylaxis is highest in the elderly, probably due to the combination of comorbidities (such as cardiovascular disease) and polypharmacy (including beta-blockers and angiotensin-converting-enzyme (ACE) inhibitors).4,7 The diagnosis is supported if there is exposure to a known trigger, however, in up to 30% of cases, there may be no obvious trigger (‘idiopathic’ or ‘spontaneous’ anaphylaxis). The characteristics of anaphylaxis to the most common causes are shown in Table 1.1,8

Table 1.

Causes and characteristics of anaphylaxis1,8

| Food | Medication/iatrogenic causes | Insect/venom sting | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age distribution: anaphylaxis (all severities) | Most common in preschool children, less common in older adults | Predominantly older ages | All ages |

| Typical presentation | Breathing problems | Circulation problems (breathing problems are less common) | Circulation problems (breathing problems are less common) |

| Onset | Less rapid | Rapid | Rapid |

| History of asthma/atopy | Common | Uncommon | Uncommon |

Adapted from the 2021 Resuscitation Council UK guideline, Emergency treatment of anaphylaxis: Guidelines for healthcare providers.

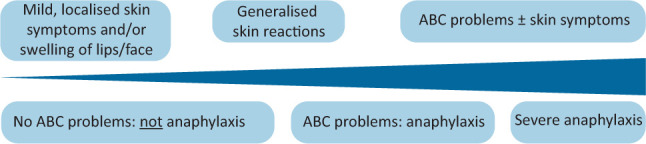

Anaphylaxis is a clinical diagnosis that lies along a spectrum of severity of allergic symptoms (Fig 1), and no symptom is entirely specific for the diagnosis.9 It is characterised by:

-

bull

sudden onset and rapid progression of symptoms

-

bull

airway and/or breathing and/or circulation (ABC) problems

-

bull

usually, skin and/or mucosal changes (urticaria, flushing or angioedema); these may be subtle or absent in 10%–20% of reactions.

Fig 1.

Spectrum of severity of anaphylaxis. Reproduced with permission from Resuscitation Council UK. ABC = airway and/or breathing and/or circulation.

Skin and/or mucosal symptoms alone are not a sign of anaphylaxis. Gastrointestinal symptoms (eg nausea, abdominal pain or vomiting) in the absence of ABC problems do not usually indicate anaphylaxis. Abdominal pain and vomiting can be symptoms of anaphylaxis due to an insect sting or bite. Different phenotypes are associated with different causes of anaphylaxis (Table 1).8

Many patients with anaphylaxis are not given the correct treatment because of failure to recognise anaphylaxis.10–13 Approximately half of anaphylaxis episodes are not treated with adrenaline, even when they occur in a healthcare setting; at the same time, adrenaline may be given to patients with non-anaphylaxis reactions that present with prominent skin features, such as urticaria or facial swelling.14–16

This updated guideline (Emergency treatment of anaphylaxis: Guidelines for healthcare providers, 2021) supersedes the 2008 RCUK guideline (annotated in 2012 with links to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance).1,17 An evidence review was undertaken by the Anaphylaxis Working Group of the RCUK, using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks for adoption, adaptation and de novo development of trustworthy recommendations, referred to as GRADE-ADOLOPMENT.18 A summary of the key recommendations is provided in Box 1.

Box 1.

Summary recommendations from 2021 Resuscitation Council UK guideline, Emergency treatment of anaphylaxis: Guidelines for healthcare providers1

| Anaphylaxis is a potentially life-threatening allergic reaction characterised by sudden onset and rapid progression of airway, breathing and circulation (ABC) problems. |

| Skin and/or mucosal changes are common but can be absent in 10%–20% of cases of anaphylaxis. |

| Correct posturing is essential in the treatment of suspected anaphylaxis: changes in posture from supine to standing are associated with cardiovascular collapse and death. |

| Intramuscular (IM) adrenaline is the most important treatment of anaphylaxis and should be given as early as possible. |

| If ABC problems persist, a second dose of IM adrenaline should be given after 5 minutes. |

| Intravenous (IV) fluids are an important adjunct in the presence of shock or poor response to an initial dose of adrenaline. |

| Refractory anaphylaxis is when ABC problems persist despite two appropriate doses of IM adrenaline. |

| A refractory anaphylaxis algorithm is provided: IV adrenaline infusions form the basis of treatment for refractory anaphylaxis; seek urgent expert help to establish a low-dose, IV adrenaline infusion. IV adrenaline should be given only by experienced specialists in an appropriate setting. |

| Antihistamines can be helpful for treating the skin features of the allergic reaction, but must not be used to treat ABC problems or delay the use of adrenaline. |

| Corticosteroids (eg hydrocortisone) are no longer advised for the routine treatment of anaphylaxis, except after initial resuscitation for refractory reactions or ongoing asthma/shock. |

| A risk-stratified approach is recommended to guide the duration of observation following treatment of anaphylaxis. |

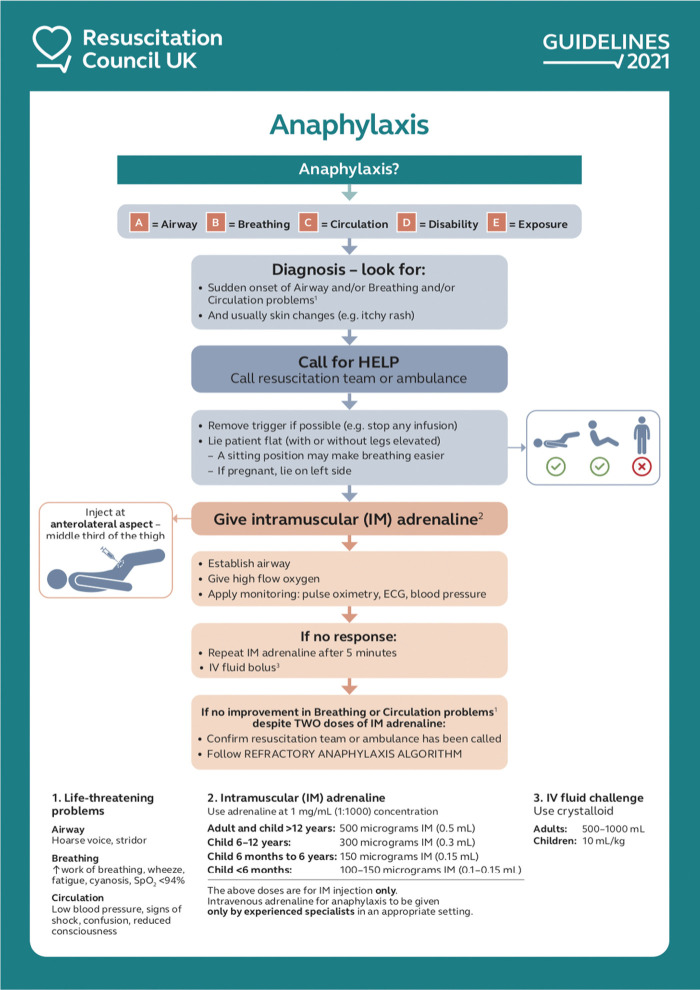

The importance of appropriate positioning in the treatment of suspected anaphylaxis

Correct posturing is essential in the treatment of anaphylaxis (note the image on the right side of the algorithm in Fig 2). Changes in posture from supine to standing are associated with cardiovascular collapse and death during anaphylaxis, due to a reduction in venous return and consequent reduced myocardial filling and perfusion.19,20 It is important to remain flat, with or without legs raised, to maximise venous return. In cases where the symptoms predominantly affect the airway or breathing, the patient may prefer to be semi-recumbent, again with or without the legs raised.

Fig 2.

Initial treatment of anaphylaxis. Reproduced with permission from Resuscitation Council UK. IM = intramuscular; IV = intravenous; SpO2 = oxygen saturation.

Emphasis on the use of IM adrenaline in the initial treatment of anaphylaxis

IM adrenaline is the first-line treatment for anaphylaxis (Fig 2). There are no randomised trials evaluating adrenaline to treat anaphylaxis, however, extensive observational data exist to support the use of adrenaline, and that delays in administration are associated with more severe outcomes and possibly death.21,22 Fatal anaphylaxis is rare but also very unpredictable, so all cases of anaphylaxis should be treated as potentially life threatening. In approximately 10% of cases, ABC problems persist despite one dose of IM adrenaline, but most respond to a second or third dose.14

Case series of out-of-hospital anaphylaxis suggest early use of adrenaline improves outcomes.23 Despite an absence of high-certainty evidence, international guidelines agree that adrenaline should be given as soon as features of anaphylaxis develop.

Up to 5% of cases exhibit biphasic anaphylaxis, where ABC features initially resolve but then recur several hours later in the absence of further exposure to the allergen.24 Several retrospective case series and a prospective cohort study have reported that delayed adrenaline administration is associated with a higher rate of biphasic anaphylaxis, supporting the emphasis on early adrenaline use.25,26

The IM route for adrenaline is the route of choice for the vast majority of healthcare providers (even if intravenous (IV) access is available). IV adrenaline should only be given by experienced specialists in an appropriate setting.

Antihistamines are considered as a third-line intervention and should not be used to treat ABC problems

The role of antihistamines in anaphylaxis is debated, but there is consensus across all guidelines that they are not a first-line treatment. There is no randomised controlled trial (RCT) or quasi-RCT evidence to support the use of antihistamines in the initial treatment of anaphylaxis, and they do not lead to resolution of the respiratory or cardiovascular features of adrenaline, or improve survival.9,23,25,27–29 The majority of patients presenting to emergency departments are treated with antihistamines, but only a minority of patients receive adrenaline.30–36 A large national prospective registry examined 3,498 cases of anaphylaxis and found that prehospital antihistamine use was associated with a lower rate of administration of more than one adrenaline dose, although this was not the case when less severe cases were excluded. Moreover, use of antihistamines is associated with occurrence of biphasic reactions, possibly due to causing delayed administration of adrenaline.37

Although antihistamines are not recommended for the initial treatment of anaphylaxis, there is a role for their use to treat skin symptoms (such as urticaria or angioedema) that may occur as part of anaphylaxis, once ABC features have resolved.38 Non-sedating antihistamines (for example, cetirizine) are preferred, as first generation antihistamines (such as chlorphenamine) can cause sedation and, if given rapidly by intravenous bolus, can precipitate hypotension.39

Corticosteroids (eg hydrocortisone) are no longer advised for the routine emergency treatment of anaphylaxis

The updated RCUK guideline advises against the routine use of corticosteroids to treat anaphylaxis. There is little evidence that corticosteroids help shorten protracted symptoms or prevent biphasic reactions.38,40 Moreover, there are emerging data to suggest that the routine use of steroids is associated with an increase in morbidity even after correcting for reaction severity.36,41 A large prospective national registry found that prehospital treatment with corticosteroids was associated with an increase in the rate of hospitalisation and/or intensive care admission.36 While this could be due to steroids being used in preference to appropriate adrenaline administration, the association between steroids and more severe outcomes remained irrespective of whether or not prehospital adrenaline was administered.36

Like antihistamines, steroids are given far more frequently than adrenaline, again raising concern that they distract from early use of adrenaline.30–36,42 A 2012 Cochrane systematic review concluded that ‘Clinicians should nonetheless be aware of the lack of a strong evidence base for the use of a glucocorticoid for the treatment of anaphylaxis’, and subsequent studies have confirmed the absence of evidence that corticosteroids reduce reaction severity or prevent biphasic reactions.25,40,42

It is important to note that there are specific scenarios in which corticosteroids may be of benefit: first, anaphylaxis occurring in the context of poorly-controlled asthma; and second, in cases of refractory anaphylaxis (defined as persistence of ABC features despite two appropriate doses of adrenaline). In these cases, the balance of risks and benefits is different and, given the uncertainty in evidence, corticosteroids may be beneficial but should not delay or replace appropriate adrenaline doses when treating anaphylaxis.

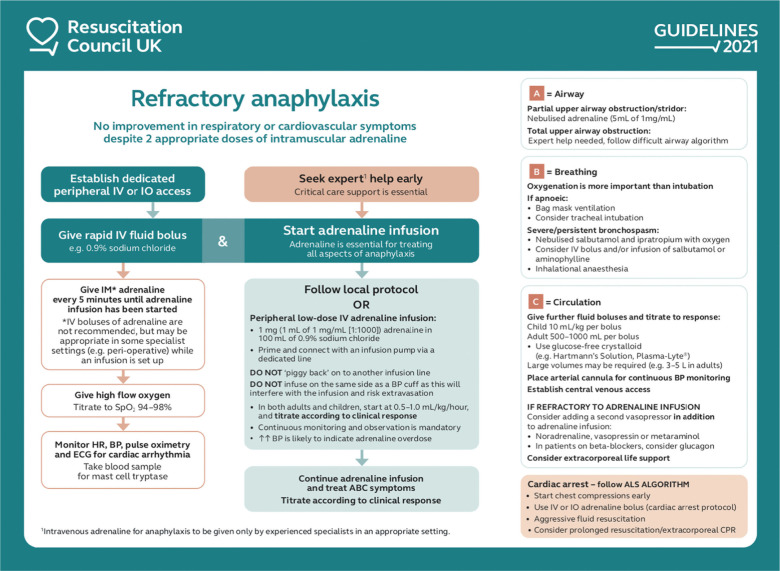

Treatment of refractory anaphylaxis

The 2021 RCUK guideline features a specific algorithm for the treatment of refractory anaphylaxis (Fig 3). There is no established definition of refractory anaphylaxis, so the RCUK has defined it as ‘anaphylaxis requiring ongoing treatment (due to persisting respiratory or cardiovascular symptoms) despite two appropriate doses of IM adrenaline.’1,43 A systematic review and meta-analysis found an estimated 3.4% of adrenaline-treated reactions have a suboptimal response to two doses of adrenaline, although most respond to three.14 Early recognition is vital, and critical care support should be sought early.

Fig 3.

Treatment of refractory anaphylaxis. Reproduced with permission from Resuscitation Council UK. ALS = advanced life support; BP = blood pressure; CPR = cardiopulmonary resuscitation; ECG = electrocardiography; HR = heart rate; IO = intraosseous; IV = intravenous; SpO2 = oxygen saturation.

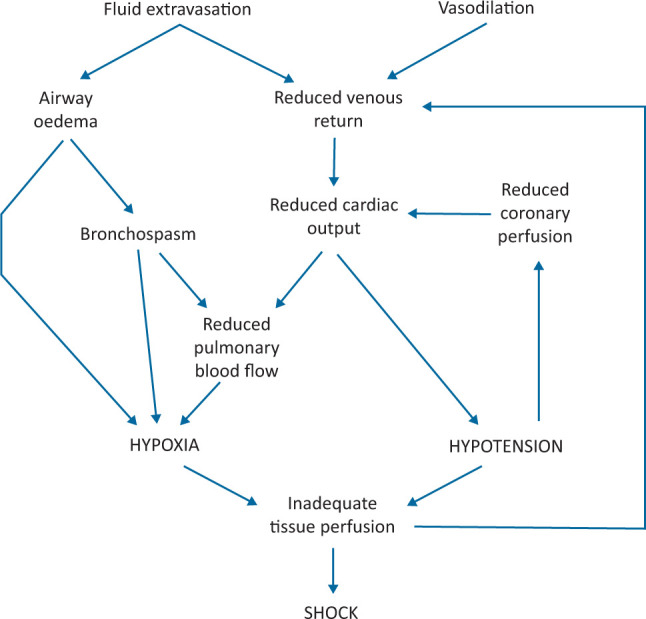

The pathophysiology of refractory anaphylaxis is likely the result of ongoing release of inflammatory mediators, insufficient circulating adrenaline (usually due to suboptimal dosing, reduced circulating blood volume or, less commonly, tachyphylaxis; Fig 4).38 Plasma extravasation equivalent to one-third of the circulating blood volume can occur within minutes in severe reactions, and venous return can be impaired even in those without clinically evident haemodynamic compromise.44,45

Fig 4.

Pathophysiological mechanisms responsible for anaphylactic shock.

The primary goal in treatment of refractory anaphylaxis is to optimise delivery of adrenaline. Intravenous fluid infusion is, therefore, crucial to treat shock and provide sufficient circulating volume to maintain cardiac output and deliver adrenaline at the tissue level.43 In cases where the ABC features of anaphylaxis persist despite two doses of IM adrenaline, a low-dose adrenaline infusion is likely to be much more effective than IM or IV boluses.46–48 As such, this along with fluid resuscitation form the basis of treatment in the 2021 guideline.

The risk of adverse effects due to IV adrenaline is much higher than with IM administration. Excessive doses can lead to tachyarrhythmias, severe hypotension, myocardial infarction, stroke and death.15,16,49–51 Therefore, IV adrenaline should only be used by clinicians who have experience in the use and titration of vasopressors in their normal practice, and in a setting where very close monitoring (including electrocardiography and blood pressure) is in place.

In cases of severe bronchospasm, an adrenaline infusion remains the cornerstone of treatment, but can be supplemented with nebulised and IV bronchodilators. Intravenous magnesium is not recommended due to the risk of significant vasodilation. In critical upper airway obstruction, nebulised adrenaline may be helpful but should not take priority over tracheal intubation.

Measurement of mast cell tryptase

Anaphylaxis is a clinical syndrome that can present in a variety of ways. There are several differential diagnoses of anaphylaxis, and measurement of an elevated mast cell tryptase can be very helpful in supporting the diagnosis of anaphylaxis over other alternatives. Tryptase is present in mast cell secretory granules: during anaphylaxis, this is released from the cells and, consequently, there may be a measurable but transient rise in the circulating level.

Tryptase measurement is not useful in the initial recognition of anaphylaxis, and measurement must not delay initial treatment and resuscitation.52 In view of the transient rise and short half-life, the timing of blood samples is important to demonstrate the rise and fall. A minimum of one sample should be obtained, ideally within 2 hours and no later than 4 hours after onset of symptoms. However, ideally three samples should be taken: the first as soon as feasible (not delaying treatment to take the sample), the second 1–2 hours (but no later than 4 hours) after onset of symptoms and a third at least 24 hours after complete resolution of symptoms. The last of these need not delay discharge, provided follow-up with an allergy clinic is arranged.

Refined guidance regarding duration of observation following anaphylaxis and timing of discharge

Patients who have been treated for suspected anaphylaxis should be observed in a clinical area with facilities for treating life-threatening ABC problems, as some patients experience further symptoms following resolution. This can be either a true biphasic reaction, or due to continued allergen exposure (for example, presence of the allergen in the gut).53 In cases of food-induced anaphylaxis, it is advisable for the patient to eat some food at least 1 hour prior to discharge to mitigate against further symptoms (due to allergen absorption in the gut) after leaving hospital.

Biphasic reactions can occur many hours after the initial reaction; published studies report a median of 12 hours (ie 50% of biphasic reactions have occurred by 12 hours after the onset of initial symptoms). The optimal duration of observation is uncertain, and the previous RCUK guideline referred to the NICE 2011 recommendation that patients over 16 years of age be observed for 6–12 hours after onset of initial symptoms, although more recent evidence suggests this may miss over 50% of biphasic reactions in the 5% of patients who experience them.24,37,54–56 Fatalities due to biphasic reactions are rare.37

Risk factors for biphasic reactions include:

-

bull

more severe initial presentation of anaphylaxis

-

bull

initial reaction requiring more than one dose of adrenaline

-

bull

delay in adrenaline administration (>30–60 minutes from onset)

-

bull

previous biphasic reaction.

Consistent with the available evidence and other guidelines, the RCUK guideline recommends a risk-stratified approach to the length of observation after anaphylaxis (Table 2).1,25,54

Table 2.

Duration of observation following anaphylaxis; reproduced with permission from the 2021 Resuscitation Council UK guideline, Emergency treatment of anaphylaxis: Guidelines for healthcare providers1

| Consider fast-track discharge (after 2 hours observation from resolution of anaphylaxis) if all or the following: | A minimum of 6 hours observation after resolution of symptoms recommended if: | Observation for at least 12 hours following resolution of symptoms if any one of the following: |

|---|---|---|

| Good response (within 10–15 minutes) to a single dose of adrenaline given within 30 minutes of onset of reaction. and Complete resolution of symptoms. and The patient already has unused adrenaline auto-injectors (AAI) and has been trained how to use them. and There is adequate supervision following discharge. |

Two doses of IM adrenaline needed to treat reaction.a or Previous biphasic reaction. |

Severe reaction requiring >2 doses of adrenaline. or Patient has severe asthma or reaction involved severe respiratory compromise. or Possibility of continuing absorption of allergen eg slow-release medicines. or Patient presents late at night or may not be able to respond to any deterioration. or Patients in areas where access to emergency care is difficult. |

In all cases, discharge must comply with National Institute for Health and Care Excellence clinical guidance CG134.54

aIt may be reasonable for some patients to be discharged after 2 hours, eg following a supervised allergy challenge in a specialist allergy setting. IM = intramuscular.

All patients should be reviewed by a senior clinician and be discharged with advice on the symptoms of anaphylaxis and what do to if anaphylaxis occurs, be provided with two adrenaline autoinjectors or have provision of replacements if they have been used, be given a demonstration of how to use the autoinjectors, and be given a written emergency treatment or action plan. All patients presenting to hospital with anaphylaxis should be referred to a specialist allergy service to investigate the cause and to help prepare the patient to manage future episodes.

Conclusion

The use of adrenaline in the initial treatment of anaphylaxis is universally accepted and has not changed in the updated RCUK guideline. However, the new guideline further emphasises the importance of positioning in the treatment of anaphylaxis, and the need to avoid interventions that might delay adequate and appropriate adrenaline administration. Antihistamines can be used as a third-line treatment to reduce skin involvement, but only after successful treatment of ABC features. Corticosteroids are not helpful and emerging evidence suggests that they might worsen outcomes when used routinely for anaphylaxis; their use is, therefore, limited to the treatment of anaphylaxis in the context of poorly-controlled asthma and refractory anaphylaxis. There is a new treatment algorithm for refractory anaphylaxis, providing an easy reference for settings where this may occur. Finally, there is more nuanced advice regarding observation following anaphylaxis, which takes into account risk factors and circumstances where delayed or recurrent symptoms may be experienced.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the following individuals for providing internal review to the updated RCUK anaphylaxis guideline and the updated recommendations. Sophie Farooque, Adam Fox, Graham Roberts and Hazel Gowland (patient advocate); and on behalf of Resuscitation Council UK: Charles Deakin, Joe Fawke, David Gabbott, Matt Griffiths, Andrew Lockey, Ian Maconochie, Jerry Nolan, Gavin Perkins and Sophie Skellett.

Working group membership: Dr Jasmeet Soar, co-chair; Dr Paul J Turner, co-chair; Dr Amy Dodd; Ms Sue Hampshire; Dr Anna Hughes; Dr Nicholas Sargant; and Dr Andrew F Whyte. For affiliations and wider consultation panel membership refer to the full guideline.1

Conflicts of interest

Andrew F Whyte is the former chair of the Adult Allergy Group of the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology.

Jasmeet Soar is the co-chair of the Anaphylaxis Working Group of the Resuscitation Council UK; editor of Resuscitation and receives payment from the publisher Elsevier; co-chair of the European Resuscitation Council Advanced Life Support (ALS) Science and Education Committee; and chair of the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation ALS Task Force.

Paul J Turner is the co-chair of the Anaphylaxis Working Group of the Resuscitation Council UK; former chair of the Paediatric Allergy Group of the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology; chair of the World Allergy Organization Anaphylaxis Committee; supported by a UK Medical Research Council Clinician Scientist award (reference MR/K010468/1) and grants from UK Medical Research Council, National Institute for Health and Care Research / Imperial Biomedical Research Centre, UK Food Standards Agency, End Allergies Together and Jon Moulton Charity Trust; personal fees and nonfinancial support from Aimmune Therapeutics, DBV Technologies and Allergenis; and personal fees and other fees from International Life Sciences Institute Europe and UK Food Standards Agency.

References

- 1.Resuscitation Council UK . Emergency treatment of anaphylaxis: Guidelines for healthcare providers. RCUK, 2021. www.resus.org.uk/library/additional-guidance/guidance-anaphylaxis/emergency-treatment [Accessed on 13 February 2022]. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lieberman P, Nicklas RA, Oppenheimer J, et al. The diagnosis and management of anaphylaxis practice parameter: 2010 update. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;126:477–80.e1-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Panesar SS, Javad S, de Silva D, et al. The epidemiology of anaphylaxis in Europe: a systematic review. Allergy 2013;68:1353–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turner PJ, Gowland MH, Sharma V, et al. Increase in anaphylaxis-related hospitalizations but no increase in fatalities: an analysis of United Kingdom national anaphylaxis data, 1992-2012. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;135:956–63.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baseggio Conrado A, Ierodiakonou D, Gowland MH, Boyle RJ, Turner PJ. Food anaphylaxis in the United Kingdom: analysis of national data, 1998-2018. BMJ 2021;372:n251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harper NJN, Cook TM, Garcez T, et al. Anaesthesia, surgery, and life-threatening allergic reactions: epidemiology and clinical features of perioperative anaphylaxis in the 6th National Audit Project (NAP6). Br J Anaesth 2018;121:159–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soar J, Pumphrey R, Cant A, et al. Emergency treatment of anaphylactic reactions–guidelines for healthcare providers. Resuscitation 2008;77:157–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turner PJ, Campbell DE. Epidemiology of severe anaphylaxis: can we use population-based data to understand anaphylaxis? Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2016;16:441–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cardona V, Ansotegui IJ, Ebisawa M, et al. World allergy organization anaphylaxis guidance 2020. World Allergy Organ J 2020;13:100472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jose R, Clesham GJ. Survey of the use of epinephrine (adrenaline) for anaphylaxis by junior hospital doctors. Postgrad Med J 2007;83:610–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Leary FM, Hokin B, Enright K, Campbell DE. Treatment of a simulated child with anaphylaxis: an in situ two-arm study. J Paediatr Child Health 2013;49:541–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lindor RA, McMahon EM, Wood JP, et al. Anaphylaxis-related malpractice lawsuits. West J Emerg Med 2018;19:693–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haymore BR, Carr WW, Frank WT. Anaphylaxis and epinephrine prescribing patterns in a military hospital: underutilization of the intramuscular route. Allergy Asthma Proc 2005;26:361–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel N, Chong KW, Yip AYG, et al. Use of multiple epinephrine doses in anaphylaxis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2021;148:1307–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnston SL, Unsworth J, Gompels MM. Adrenaline given outside the context of life threatening allergic reactions. BMJ 2003;326:589–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Macdougall CF, Cant AJ, Colver AF. How dangerous is food allergy in childhood? The incidence of severe and fatal allergic reactions across the UK and Ireland. Arch Dis Child 2002;86:236–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soar J, Guideline Development Group . Emergency treatment of anaphylaxis in adults: concise guidance. Clin Med 2009;9:181–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schünemann HJ, Wiercioch W, Brozek J, et al. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks for adoption, adaptation, and de novo development of trustworthy recommendations: GRADE-ADOLOPMENT. J Clin Epidemiol 2017;81:101–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pumphrey RSH. Fatal posture in anaphylactic shock. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003;112:451–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mullins RJ, Wainstein BK, Barnes EH, Liew WK, Campbell DE. Increases in anaphylaxis fatalities in Australia from 1997 to 2013. Clin Exp Allergy J Br Soc Allergy Clin Immunol 2016;46:1099–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Silva D, Singh C, Muraro A, et al. Diagnosing, managing and preventing anaphylaxis: Systematic review. Allergy 2021;76:1493–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ko BS, Kim JY, Seo D-W, et al. Should adrenaline be used in patients with hemodynamically stable anaphylaxis? Incident case control study nested within a retrospective cohort study. Sci Rep 2016;6:20168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muraro A, Roberts G, Worm M, et al. Anaphylaxis: guidelines from the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. Allergy 2014;69:1026–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee S, Bellolio MF, Hess EP, et al. Time of onset and predictors of biphasic anaphylactic reactions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2015;3:408–16.e1-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaker MS, Wallace DV, Golden DBK, et al. Anaphylaxis-a 2020 practice parameter update, systematic review, and Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2020;145:1082–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu X, Lee S, Lohse CM, Hardy CT, Campbell RL. Biphasic Reactions in Emergency Department Anaphylaxis Patients: A Prospective Cohort Study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2020;8:1230–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simons FER, Ebisawa M, Sanchez-Borges M, et al. 2015 update of the evidence base: World Allergy Organization anaphylaxis guidelines. World Allergy Organ J 2015;8:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dhami S, Panesar SS, Roberts G, et al. Management of anaphylaxis: a systematic review. Allergy 2014;69:168–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nurmatov UB, Rhatigan E, Simons FER, Sheikh A. H2-antihistamines for the treatment of anaphylaxis with and without shock: a systematic review. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol Off Publ Am Coll Allergy Asthma Immunol 2014;112:126–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang F, Chawla K, Järvinen KM, Nowak-We˛grzyn A. Anaphylaxis in a New York City pediatric emergency department: triggers, treatments, and outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012;129:162–8.e1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beyer K, Eckermann O, Hompes S, Grabenhenrich L, Worm M. Anaphylaxis in an emergency setting - elicitors, therapy and incidence of severe allergic reactions. Allergy 2012;67:1451–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fineman SM. Optimal treatment of anaphylaxis: antihistamines versus epinephrine. Postgrad Med 2014;126:73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ruiz Oropeza A, Lassen A, Halken S, Bindslev-Jensen C, Mortz CG. Anaphylaxis in an emergency care setting: a one year prospective study in children and adults. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2017;25:111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dubus J-C, Lê M-S, Vitte J, et al. Use of epinephrine in emergency department depends on anaphylaxis severity in children. Eur J Pediatr 2019;178:69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choi YJ, Kim J, Jung JY, Kwon H, Park JW. Underuse of epinephrine for pediatric anaphylaxis victims in the emergency department: a population-based study. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 2019;11:529–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gabrielli S, Clarke A, Morris J, et al. Evaluation of prehospital management in a Canadian emergency department anaphylaxis cohort. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019;7:2232–8.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kraft M, Scherer Hofmeier K, Ruëff F, et al. Risk factors and characteristics of biphasic anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2020;8:3388–95.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dodd A, Hughes A, Sargant N, et al. Evidence update for the treatment of anaphylaxis. Resuscitation 2021;163:86–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy . ASCIA Guidelines: Acute management of anaphylaxis. ASCIA, 2021. www.allergy.org.au/hp/papers/acute-management-of-anaphylaxis-guidelines [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alqurashi W, Ellis AK. Do corticosteroids prevent biphasic anaphylaxis? J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2017;5:1194–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Campbell DE. Anaphylaxis management: time to re-evaluate the role of corticosteroids. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019;7:2239–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choo KJL, Simons FER, Sheikh A. Glucocorticoids for the treatment of anaphylaxis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012:CD007596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sargant N, Dodd A, Hughes A, et al. Refractory anaphylaxis: treatment algorithm. Allergy 2021;76:1595–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fisher MM. Clinical observations on the pathophysiology and treatment of anaphylactic cardiovascular collapse. Anaesth Intensive Care 1986;14:17–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ruiz-Garcia M, Bartra J, Alvarez O, et al. Cardiovascular changes during peanut-induced allergic reactions in human subjects. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2021;147:633–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brown SGA, Blackman KE, Stenlake V, Heddle RJ. Insect sting anaphylaxis; prospective evaluation of treatment with intravenous adrenaline and volume resuscitation. Emerg Med J 2004;21:149–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alviani C, Burrell S, Macleod A, et al. Anaphylaxis refractory to intramuscular adrenaline during in-hospital food challenges: A case series and proposed management. Clin Exp Allergy J Br Soc Allergy Clin Immunol 2020;50:1400–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mink SN, Simons FER, Simons KJ, Becker AB, Duke K. Constant infusion of epinephrine, but not bolus treatment, improves haemodynamic recovery in anaphylactic shock in dogs. Clin Exp Allergy J Br Soc Allergy Clin Immunol 2004;34:1776–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Campbell RL, Bellolio MF, Knutson BD, et al. Epinephrine in anaphylaxis: higher risk of cardiovascular complications and overdose after administration of intravenous bolus epinephrine compared with intramuscular epinephrine. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2015;3:76–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cardona V, Ferré-Ybarz L, Guilarte M, et al. Safety of adrenaline use in anaphylaxis: a multicentre register. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2017;173:171–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Simons FE, Gu X, Simons KJ. Epinephrine absorption in adults: intramuscular versus subcutaneous injection. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001;108:871–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Francis A, Fatovich DM, Arendts G, et al. Serum mast cell tryptase measurements: Sensitivity and specificity for a diagnosis of anaphylaxis in emergency department patients with shock or hypoxaemia. Emerg Med Australas 2018;30:366–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Turner PJ, Ruiz-Garcia M, Patel N, et al. Delayed symptoms and orthostatic intolerance following peanut challenge. Clin Exp Allergy J Br Soc Allergy Clin Immunol 2021;51:696–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Anaphylaxis: assessment and referral after emergency treatment: Clinical Guideline [CG134]. NICE, 2011. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg134 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pumphrey RS, Roberts IS. Postmortem findings after fatal anaphylactic reactions. J Clin Pathol 2000;53:273–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim T-H, Yoon SH, Hong H, et al. Duration of observation for detecting a biphasic reaction in anaphylaxis: a meta-analysis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2019;179:31–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]