Abstract

Screening tests are done to diagnose asymptomatic disease in apparently healthy people with the aim to reduce mortality and morbidity from the disease. Certain criteria need to be fulfilled before we adopt population-level screening for any disease. Several biases exist in evaluating screening studies, and the ideal study design would be a randomized trial with hard endpoints such as mortality and morbidity.

Keywords: Diagnosis, mass screening, research methodology

WHAT IS SCREENING?

A “screening test” refers to a medical test or procedure (often a laboratory or radiological test but can be a specific clinical examination or questionnaire) on a defined population of asymptomatic apparently healthy persons to sort them into those who probably have a disease and those who probably do not. The screening test is not always intended to be diagnostic, and those screened “positive” often need another confirmatory procedure or test.

Some common examples of screening are as follows: blood sugar measurement for early detection of diabetes/prediabetes, mammography for early detection of breast cancer, prostate-specific antigen measurement for prostate cancer, stool occult blood testing or colonoscopy for colon cancer, cholesterol level measurement to detect those at increased risk of cardiovascular disease, audiometric screening of newborn babies for hearing impairment, and antenatal ultrasound in pregnant women for the detection of fetal neural tube defect.

The rationale for screening is that if the disease or its precursor is identified early (before the manifestation of symptoms), then it may be possible to institute earlier treatment which in turn may lead to a cure or improved survival or better quality of life.

CRITERIA FOR SCREENING

The introduction of a screening test in a population, though it may intuitively appear beneficial, often poses some challenges, such as the potential risk of a false-positive test result leading to unnecessary further testing, treatment and potential harm, and of additional cost, and is thus a subject of debate. Wilson and Jungner,[1,2] in a landmark publication in 1968, stated 10 principles that have stood the test of time in guiding the discussion and decisions about the benefits, harm, costs, and ethics of screening programs (See Box 1).

Box 1.

Wilson and Jungner’s principles of screening

| 1. The condition should be an important health problem |

| 2. There should be an accepted treatment for patients with recognized disease |

| 3. Facilities for diagnosis and treatment should be available |

| 4. There should be a recognizable latent or early symptomatic phase |

| 5. There should be a suitable test or examination |

| 6. The test should be acceptable to the population |

| 7. The natural history of the condition, including development from latent to declared disease, should be adequately understood |

| 8. There should be an agreed policy on whom to treat as patients |

| 9. The cost of case-finding (including a diagnosis and treatment of patients diagnosed) should be economically balanced in relation to possible expenditure on medical care as a whole |

| 10. Case-finding should be a continuous process and not a “once and for all” project |

QUALITIES OF A TEST FOR USE AS A SCREENING TEST

An ideal test would perfectly separate those who have the condition from those who do not. However, in real life, no test is perfect, resulting in some healthy people having an abnormal or positive test result (false positive) and some people with the condition having a normal or negative screening result (false negative). We have discussed the performance characteristics of diagnostic tests, including sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value in previous pieces in this series.[3,4,5]

It is important to note that since the prevalence of the disease among those screened is likely to be lower than in a clinic setting, the positive predictive values tend to be lower, and the number of false positives is higher in screening programs. It is therefore important to ensure that those who test positive on the screening test undergo further confirmatory testing.

The initial screening test should have a high sensitivity, besides being safe and cheap. By contrast, the confirmatory test should have a very high specificity. For instance, for colon cancer, fecal occult blood testing is used as a screening test, and those who test positive are then subjected to confirmation using colonoscopy and biopsy of any lesion that may be detected. Other examples include mammography, followed by tissue biopsy for breast cancer, serum prostate-specific antigen measurement, followed by image-guided prostatic biopsies.

ASSESSMENT OF EFFICACY/EFFECTIVENESS OF SCREENING

For a screening test to prove effective, it must not merely diagnose more cases of the disease of interest or diagnose cases earlier, but ultimately improve the outcome. For instance, screening for breast cancer using mammography must not merely diagnose more breast cancers or diagnose them at an early stage when treatment is possible, but it should reduce deaths due to breast cancer.

Ideally, the assessment of the value of a screening program requires a randomized controlled trial. An example would be the comparison of groups of women randomized to undergo mammography or clinical breast examination screening or otherwise, with the reduction in breast cancer-specific mortality as the expected endpoint.[6] However, such trials of screening programs need a large number of subjects and/or prolonged follow-up, making these quite challenging to do. Therefore, clinicians often resort to cohort studies (comparing outcomes of those who enroll for a screening program vs. those who do not) and, at times, case–control studies (i.e., comparison of cancers diagnosed as part of a screening program [cases of interest] and of cancers diagnosed as a part of routine clinical care [comparator or the controls]). However, these observational studies often exaggerate the benefits of the screening test due to a variety of biases.

BIASES IN OBSERVATIONAL STUDIES ON SCREENING PROGRAMS

The biases inherent in the use of observational studies for assessing the effectiveness of screening programs are multifold; each of these is discussed in brief below. Of these lead time bias, length bias and detection (overdiagnosis) bias are forms of information bias and volunteer bias is a type of selection bias. These biases have been most well studied in relation to the use of screening tests for cancers.

Lead time bias

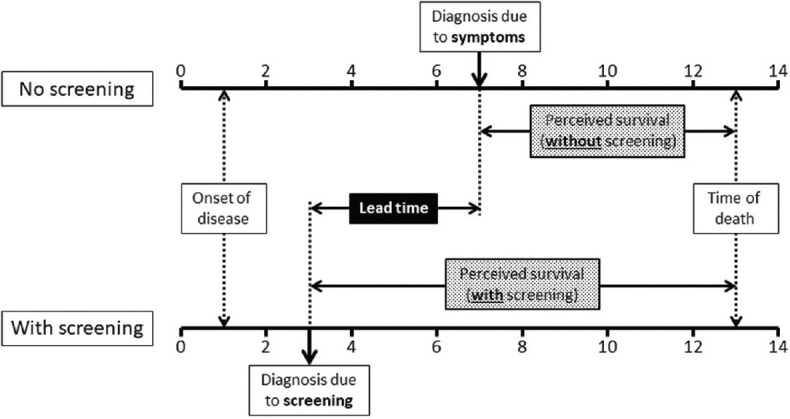

Lead time bias occurs because a screening test detects the disease at an earlier time point than when it would have been if it had been diagnosed by its clinical appearance. The difference between the two-time points (i.e., the time interval from diagnosis at screening to that of the likely detection after the occurrence of symptoms), during which the disease is asymptomatic, is referred to as “lead-time.” If in the persons whose disease is diagnosed during screening, survival time is measured from the time of such diagnosis, then the apparent increased survival time in the screened as compared with the control group may in truth be an artifactual difference [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Lead time bias. X-axis represents time in years. Two scenarios, namely where the disease is diagnosed in the usual clinical situation (after the occurrence of symptoms; top) and when the disease is diagnosed by screening (bottom), have been compared. Even though there is no real change in survival following early detection of disease by screening, the perceived duration of survival is increased, due to a lead time effect

Let us assume two women (A and B) who both have similar and small breast cancers that they are unaware of. Both are offered screening mammography in January 2022. Woman “A” decides to forego screening, the cancer remains undetected, finally being diagnosed in 2024 after becoming symptomatic and she lives till 2027. By comparison, the woman “B” undergoes mammography and is diagnosed immediately, receives treatment, and also dies in 2027. If the survival period is calculated in both cases from the respective time of diagnosis, it would seem to be longer for B (2022–2027, or 5 years) than for A (2024–2027, or 3 years). However, both the women lived the same amount of time and there has been no real gain in survival. Instead, screening appears to have resulted in falsely improved outcomes.

Length bias

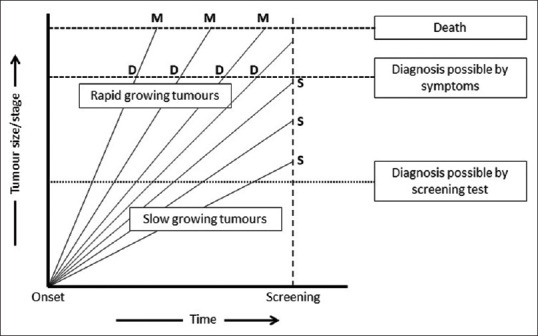

This bias relates to the variability in the “length” of presymptomatic period for the disease (say breast cancer) that the screening test is intended to diagnose. All cancers are not identical, with some being aggressive and rapidly progressing, whereas others are indolent and slow-growing. Because the latter type has a longer presymptomatic period, they are likely to be overrepresented among the cancers picked up by screening.

This preferential picking up of the slower-growing tumors by the screening tests thus leads to an exaggeration of the apparent benefit [Figure 2]. This risk is even more likely when screening is done in older persons who are more likely to have slower-growing tumors and to die of competing causes.[7]

Figure 2.

Length bias. X-axis represents time. Y-axis represents tumor size or stage. The disease onset is at zero and each oblique line represents tumor growth in an individual, with lines on the left for persons with rapid tumor growth and those on the right and bottom for those with slower tumor growth. The persons with rapid growth are diagnosed based on symptoms (D) and die (M) rapidly. By comparison, the individuals with slower growth are more likely to be diagnosed where they get screened (S), and they would live longer

Detection or overdiagnosis bias

This form of bias relates to an extreme form of “length bias,” whereby screening diagnoses a larger number of tumor cases that grow so slowly that these would not be expected to cause symptoms or death in a person's lifetime. Thus, even though screening leads to a large increase in the number of tumors diagnosed, it does not lead to an improvement in the overall outcome. This is best exemplified by screening for thyroid cancer, where the US Preventive Services Task Force found no substantial change in survival despite a massive increase in the number of diagnosed cases, leading it to issue a recommendation against such screening.[8]

Referral/volunteer bias (selection bias)

This form of bias relates to the possibility that persons who volunteer for screening differ from those who do not volunteer. It is likely that those who volunteer for screening are also more likely to be health conscious in other ways, and therefore more likely to have better overall health outcomes than those who do not. These differences, such as in their health status and behavioral factors, may influence the outcome of their diseases, leading to an apparent difference in survival rates in the screened and nonscreened cohorts.

OTHER CONSIDERATIONS

As indicated above, a randomized controlled trial comparing groups of healthy persons offered screening and not offered screening is the best design to assess the benefits of a screening program. This design not only (almost) eliminates the risk of the several biases discussed above, but can also take into account compliance, i.e., the willingness to undergo a screening test in the first place. If a large part of the target population is unwilling to undergo a particular screening test, the latter would be expected to have very little impact. For example, in screening for colon cancer, the fecal occult blood test may, despite its lower sensitivity, be a more effective screening test because of a higher compliance rate, than colonoscopy which is a test with excellent sensitivity but low acceptability.

It has been argued that even in randomized controlled trials, it may be better to compare all-cause mortality, rather than disease-specific mortality. This is because the determination of the cause of death can be fickle/subjective. Let us consider a screening test for early cancer, which leads to treatment with an effective anticancer drug that is also cardiotoxic. If a proportion of those diagnosed early dies of drug toxicity, the group assigned to screening may appear to be benefited with fewer deaths attributed to cancer than the group not receiving screening though the total number of deaths may be unchanged, with the difference being accounted for by a greater number of cardiac deaths. However, the sample size required to demonstrate reduced overall mortality is likely to be unrealistically high, and very few screening trials have been done with that as the primary endpoint. A reasonable compromise would be to use disease-related mortality (which would also include treatment-related deaths) and use an independent blinded observer to attribute the cause of death.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wilson J, Junger G. Principles and Practice of Screening for Disease. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1968. [Last accessed on 2022 Apr 27]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/37650/WHO_PHP_34.pdf ?sequence=17 . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Increase Effectiveness, Maximize Benefits and Minimize Harm. Copenhagen: : WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2020. [Last accessed on 2022 Apr 27]. Screening Programmes: A Short Guide. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/330829/9789289054782-eng.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ranganathan P, Aggarwal R. Common pitfalls in statistical analysis: Understanding the properties of diagnostic tests – Part 1. Perspect Clin Res. 2018;9:40–3. doi: 10.4103/picr.PICR_170_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ranganathan P, Aggarwal R. Understanding the properties of diagnostic tests – Part 2: Likelihood ratios. Perspect Clin Res. 2018;9:99–102. doi: 10.4103/picr.PICR_41_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aggarwal R, Ranganathan P. Understanding diagnostic tests – Part 3: Receiver operating characteristic curves. Perspect Clin Res. 2018;9:145–8. doi: 10.4103/picr.PICR_87_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mittra I, Mishra GA, Dikshit RP, Gupta S, Kulkarni VY, Shaikh HKA, et al. Effect of screening by clinical breast examination on breast cancer incidence and mortality after 20 years: Prospective, cluster randomised controlled trial in Mumbai. BMJ. 2021;372:n256. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berry DA, Baines CJ, Baum M, Dickersin K, Fletcher SW, Gøtzsche PC, et al. Flawed inferences about screening mammography's benefit based on observational data. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:639–40. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.9341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.US Preventive Services Task Force. Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Barry MJ, Davidson KW, et al. Screening for thyroid cancer: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2017;317:1882–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.4011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]