Abstract

Background

Dental caries is a highly prevalent chronic disease which affects the majority of people. It has been postulated that the consumption of xylitol could help to prevent caries. The evidence on the effects of xylitol products is not clear and therefore it is important to summarise the available evidence to determine its effectiveness and safety.

Objectives

To assess the effects of different xylitol‐containing products for the prevention of dental caries in children and adults.

Search methods

We searched the following electronic databases: the Cochrane Oral Health Group Trials Register (to 14 August 2014), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library, 2014, Issue 7), MEDLINE via OVID (1946 to 14 August 2014), EMBASE via OVID (1980 to 14 August 2014), CINAHL via EBSCO (1980 to 14 August 2014), Web of Science Conference Proceedings (1990 to 14 August 2014), Proquest Dissertations and Theses (1861 to 14 August 2014). We searched the US National Institutes of Health Trials Register (http://clinicaltrials.gov) and the WHO Clinical Trials Registry Platform for ongoing trials. No restrictions were placed on the language or date of publication when searching the electronic databases.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials assessing the effects of xylitol products on dental caries in children and adults.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently screened the results of the electronic searches, extracted data and assessed the risk of bias of the included studies. We attempted to contact study authors for missing data or clarification where feasible. For continuous outcomes, we used means and standard deviations to obtain the mean difference and 95% confidence interval (CI). We used the continuous data to calculate prevented fractions (PF) and 95% CIs to summarise the percentage reduction in caries. For dichotomous outcomes, we reported risk ratios (RR) and 95% CIs. As there were less than four studies included in the meta‐analysis, we used a fixed‐effect model. We planned to use a random‐effects model in the event that there were four or more studies in a meta‐analysis.

Main results

We included 10 studies that analysed a total of 5903 participants. One study was assessed as being at low risk of bias, two were assessed as being at unclear risk of bias, with the remaining seven being at high risk of bias.

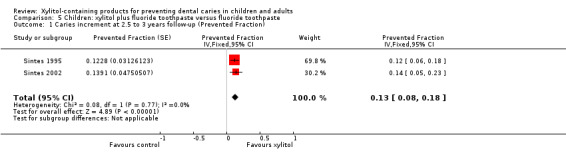

The main finding of the review was that, over 2.5 to 3 years of use, a fluoride toothpaste containing 10% xylitol may reduce caries by 13% when compared to a fluoride‐only toothpaste (PF ‐0.13, 95% CI ‐0.18 to ‐0.08, 4216 children analysed, low‐quality evidence).

The remaining evidence on children, from small single studies with risk of bias issues and great uncertainty associated with the effect estimates, was insufficient to determine a benefit from xylitol products. One study reported that xylitol syrup (8 g per day) reduced caries by 58% (95% CI 33% to 83%, 94 infants analysed, low quality evidence) when compared to a low‐dose xylitol syrup (2.67 g per day) consumed for 1 year.

The following results had 95% CIs that were compatible with both a reduction and an increase in caries associated with xylitol: xylitol lozenges versus no treatment in children (very low quality body of evidence); xylitol sucking tablets versus no treatment in infants (very low quality body of evidence); xylitol tablets versus control (sorbitol) tablets in infants (very low quality body of evidence); xylitol wipes versus control wipes in infants (low quality body of evidence).

There was only one study investigating the effects of xylitol lozenges, when compared to control lozenges, in adults (low quality body of evidence). The effect estimate had a 95% CI that was compatible with both a reduction and an increase in caries associated with xylitol.

Four studies reported that there were no adverse effects from any of the interventions. Two studies reported similar rates of adverse effects between study arms. The remaining studies either mentioned adverse effects but did not report any usable data, or did not mention them at all. Adverse effects include sores in the mouth, cramps, bloating, constipation, flatulence, and loose stool or diarrhoea.

Authors' conclusions

We found some low quality evidence to suggest that fluoride toothpaste containing xylitol may be more effective than fluoride‐only toothpaste for preventing caries in the permanent teeth of children, and that there are no associated adverse‐effects from such toothpastes. The effect estimate should be interpreted with caution due to high risk of bias and the fact that it results from two studies that were carried out by the same authors in the same population. The remaining evidence we found is of low to very low quality and is insufficient to determine whether any other xylitol‐containing products can prevent caries in infants, older children, or adults.

Plain language summary

Can xylitol used in products like sweets, candy, chewing gum and toothpaste help prevent tooth decay in children and adults?

Review question

This review has been produced to assess whether or not xylitol, a natural sweetener used in products such as sweets, candy, chewing gum and toothpaste, can help prevent tooth decay in children and adults.

Background

Tooth decay is a common disease affecting up to 90% of children and most adults worldwide. It impacts on quality of life and can be the reason for thousands of children needing dental treatment under general anaesthetic in hospital. However, it can easily be prevented and treated by good oral health habits such as brushing teeth regularly with toothpaste that contains fluoride and cutting down on sugary food and drinks. If left undisturbed, the unhelpful bacteria in the mouth ‐ which cause decay ‐ multiply and stick to the surfaces of teeth producing a sticky film. Then, when sugar is eaten or drank, the bad bacteria in the film are able to make acid resulting in tooth decay.

Xylitol is a natural sweetener, which is equally as sweet as normal sugar (sucrose). As well as providing an alternative to sugar, it has other properties that are thought to help prevent tooth decay, such as increasing the production of saliva and reducing the growth of bad bacteria in the mouth so that less acid is produced.

In humans, xylitol is known to cause possible side effects such as bloating, wind and diarrhoea.

Study characteristics

Authors from the Cochrane Oral Health Group carried out this review of existing studies and the evidence is current up to 14 August 2014. It includes 10 studies published from 1991 to 2014 in which 7969 participants were randomised (5903 of whom were included in the analyses) to receive xylitol products or a placebo (a substitute without xylitol) or no treatment, and the amount of tooth decay was compared. One study included adults, the others included children aged from 1 month to 13 years. The products tested were the kind that are held in the mouth and sucked (lozenges, sucking tablets and sweets) or slowly released through a dummy/pacifier, as well as toothpastes, syrups, and wipes.

Key results

There is some evidence to suggest that using a fluoride toothpaste containing xylitol may reduce tooth decay in the permanent teeth of children by 13% over a 3 year period when compared to a fluoride‐only toothpaste. Over this period, there were no side effects reported by the children. The remaining evidence we found did not allow us to conclude whether or not any other xylitol‐containing products can prevent tooth decay in infants, older children, or adults.

Quality of the evidence

The evidence presented is of low to very low quality due to the small amount of available studies, uncertain results, and issues with the way in which they were conducted.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Xylitol toothpaste versus control toothpaste for preventing dental caries.

| Xylitol toothpaste compared with control toothpaste for preventing dental caries | ||||||

|

Patient or population: children with permanent teeth Settings: schools Intervention: fluoride toothpaste containing 10% xylitol Comparison: fluoride toothpaste | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Xylitol | |||||

|

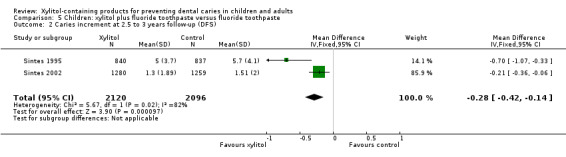

Caries: increment (DFS) prevented fraction (PF) at 2.5 to 3 years follow‐up (higher DFS score indicates worse caries) |

The (weighted) mean caries increment for control groups was 2.1 | The mean caries increment in the xylitol groups was 0.28 lower (0.42 to 0.14 lower) |

PF¹ = 0.13 (0.08 to 0.18) | 4216 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low² |

The PF of 0.13 means that there was a 13% reduction in caries in the xylitol group There is no compelling evidence, from other comparisons in this systematic review, to support the use of xylitol products. The body of evidence for all other comparisons and caries outcomes is rated as being low to very low quality. This is because they are single studies with imprecision mostly due to very small sample sizes, and most of which have a high risk of bias |

| Adverse effects | Both studies reported that there were no adverse effects in either the xylitol or control group | |||||

| CI: Confidence interval; DFS: decayed filled surfaces; PF: prevented fraction | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

¹ The prevented fraction (PF) is calculated as follows: the mean increment in the controls minus the mean increment in the treated group divided by the mean increment in the controls

² Downgraded due to high risk of bias in the included studies (due to high attrition) and both studies were conducted by the same authors in the same population

Background

Description of the condition

Dental caries affects 60% to 90% of children as well as the majority of adults (Petersen 2003). The condition is a chronic disease caused by the consumption of free sugars (Moynihan 2013; Sheiham 2014) in the presence of indigenous cariogenic bacteria (Sato 1996). Although a variety of bacteria have been implicated in the caries process, Streptococcus mutans (S. mutans) ‐ a gram‐positive bacteria ‐ has been identified as the primary pathogen (Marsh 1992). The development of dental caries is a dynamic process, and four factors need to be present simultaneously (Qualtrough 2005):

a fermentable carbohydrate (dietary sugars);

bacteria (in dental plaque/biofilm);

a susceptible tooth surface;

sufficient time for the preceding factors to interact.

If there is time (due to inadequate oral hygiene measures) then bacteria in the oral cavity will build up, adhere to tooth surfaces and interact with saliva to form a biofilm (Reese 2007). Acid is subsequently derived from the metabolic processes within this biofilm (the main driver for this is the availability of dietary free sugars such as sucrose, glucose and fructose) leading to a reduction in pH; mineral (calcium, phosphate) is then lost from the tooth surface (demineralisation). As the availability of dietary sugars depletes and the pH increases, remineralisation occurs as minerals dissolved in the saliva are re‐incorporated into the tooth structure (Manji 1991). The net result of this is the maintenance of an intact tooth. However, the frequent intake of dietary sugars leads to an imbalance in demineralisation and remineralisation in favour of the former; this leads to the formation of a carious lesion (Bowen 1978). The diagnosis of dental caries is based on clinical and, where appropriate, radiographic examination.

An estimation of the depth of demineralisation (extent of the carious lesion) and a judgement of whether the lesion is active dictates its management (Nyvad 1997). Management may be operative or non‐operative (preventive) (Pitts 2004).

Operative management consists of removal of demineralised dental tissue and replacement with a synthetic material to prevent the continuation of the carious process. This restorative procedure can result in the repeated need for repair and/or replacement of the restoration, and with each intervention greater tooth loss inevitably occurs. Eventually the tooth may become unrestorable leading to its loss. This has been referred to as the restorative staircase (Sharif 2010).

Prevention of caries can avoid the initiation of this process. Preventive strategies are focused on reducing one or all of the four factors required for the development of dental caries (listed above). Several Cochrane reviews have evaluated the effectiveness of antimicrobial therapy, dental floss, fissure sealants, dietary advice and fluorides in the prevention of dental caries (Harris 2012; Hiiri 2010; Pereira‐Ceni 2009; Sambunjak 2011). The most widely reported preventive measure has been the use of fluorides (Benson 2004; Marinho 2003; Marinho 2009; Walsh 2010). Fluoride inhibits demineralisation when it is present as a solution; it also aids remineralisation and has been reported to be a bacteriostatic agent (Featherstone 1999).

Description of the intervention

Sugar alcohols (or polyols) are sweet tasting organic compounds that occur naturally and can be used to replace sucrose (table sugar). There are many sugar alcohols used in the food industry; for example, maltitol, lactitol, sorbitol, mannitol, erythritol and xylitol.

Xylitol is a 5‐carbon sugar alcohol of crystalline structure, found in many fruits and plants (Jones 1979). It achieves equal sweetness to sucrose without resulting in a physiological requirement for insulin production as it is not absorbed in the small intestine. Consequently xylitol is used as a sucrose substitute in many diabetic food products (Brunzell 1978). The main reported adverse side effect of xylitol is its laxative effect (Wang 1981).

Xylitol has been produced in a variety of preparations including chewing gum, syrup, lozenges, sprays, mouthwashes, gels, toothpaste, candies, and varnishes (Alanen, Gutmann 2000; Ly 2006; Makinen 1982; Milgrom, Rothen 2009; Pereira‐Ceni 2009).

How the intervention might work

There are three ways in which products containing xylitol may reduce caries. The first is by a passive substitution of cariogenic free sugars (for example, sucrose ‐ table sugar). The sugar alcohols have been shown from in‐vitro, animal and in‐vivo cariogenicity tests to be either non‐acidogenic or hypo‐acidogenic, and therefore extremely low or non‐cariogenic (van Loveren 2004). If cariogenic sugars are replaced by non‐cariogenic sugar alcohols, this will reduce the incidence of caries. For the purpose of this review, studies where known cariogenic sugars were substituted with xylitol were not eligible.

The second method by which xylitol containing products may reduce caries is by saliva stimulation. Chewing or sucking on a non‐cariogenic pastille or lozenge will stimulate saliva secretion. Saliva itself inhibits caries in four ways; 1) mechanical cleansing or flushing action, 2) delivering calcium, phosphate and fluoride ions for the remineralisation of enamel, 3) by acting as a buffer to plaque acids via carbonate, phosphate and protein and 4) by specific anti‐bacterial properties (Dowd 1999; Lamanda 2007; Ruhl 2012). Studies comparing xylitol to a non‐placebo control were therefore eligible for this review to allow investigation of this effect.

Thirdly, there may be a specific anti‐caries effect attributable to xylitol. Of the non‐cariogenic sugar alcohols, xylitol has received the most attention in caries prevention studies, because it has also been shown to inhibit the growth of oral bacteria. This may be the mechanism by which it reduces the occurrence of acute otitis media in children up to the age of 12 years (Azarpazhooh 2011).

Xylitol cannot be used for energy production by the primary bacteria responsible for the dental caries process – S. mutans (Marsh 1992; Vadeboncoeur 1983). Instead, S. mutans metabolises xylitol to xylitol–5–phosphate, which then represses the normal metabolism of glucose to lactate (plaque acid) by inhibition of glycolytic enzymes. This results in reduced plaque acid production, and S. mutans entering an energy wasting cycle which inhibits its growth (Miyasawa 2003; Trahan 1985; Trahan 1995).

However, the anti‐S. mutans effect of xylitol in‐vivo over the long term is unclear, because through natural selection, S. mutans becomes resistant to xylitol in habitual users (Trahan 1987); and glucose metabolism and lactate production appear to recover to normal levels, even in the presence of xylitol‐5‐phosphate (Assev 2002; Takahashi 2011). It has been suggested that the xylitol resistant strain of S. Mutans may be less cariogenic due to reduced adherence to tooth surfaces and formation of a less sturdy plaque biofilm (Lee 2012; Söderling 2010; Tanzer 2006; Trahan 1985).

The intra‐oral environment contains a complex ecosystem of multi‐species cariogenic plaque bacteria, interacting with saliva and fluoride over time. Although xylitol shows promising properties in the laboratory, it remains to be seen whether xylitol has active anti‐caries properties over the long term, in‐vivo. Clinical studies which can answer this question require xylitol to be compared to a non‐cariogenic placebo, and these studies were also eligible for this review.

Why it is important to do this review

The dental caries process and its management has the potential to cause pain, infection, and in young children can lead to the development of dental anxiety, especially if treatment requires extraction of teeth under general anaesthetic in hospital (Hosey 2006). In addition, caries can be costly to treat (Skaret 1998; Stephen 1978). Experience of dental caries has been shown to adversely affect oral health related quality of life outcomes (Chen 1996).

Xylitol remains a controversial topic in the prevention of caries. In the US, xylitol is incorporated into many public and private preventive dental programs based on its recommendation in several clinical guidelines, for both adults and children (AAPD 2010; AAPD 2013; ADA 2011). However, its use is not mentioned at all in UK guidelines on caries prevention (DBOH 2014; SIGN 2014), and although the xylitol studies first originated in Europe, European researchers and clinicians have tended to be hesitant in recommending the use of xylitol for caries prevention (Fontana 2012; Söderling 2009). This variation in recommendation is due to conflicting results in the literature concerning its effectiveness, caused by poorly designed studies, inadequate sample sizes, inconsistent use of outcome measures, and widely varying (and often very low) doses of xylitol (Twetman 2009).

Objectives

To assess the effects of different xylitol‐containing products on preventing dental caries in children and adults.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including cluster randomised trials but excluding cross‐over trials. Cross‐over trials are inappropriate for studies with caries as an outcome due to the potential for a carry‐over effect.

Types of participants

Inclusion criteria: children and adults.

Exclusion criteria: studies in which the majority of participants were undergoing fixed or removable orthodontic treatment; the intervention was provided for less than one year; or participants were selected on the basis of having underlying health conditions.

Types of interventions

We compared xylitol‐containing products with placebo or no intervention (which includes routine care). We also included trials comparing one xylitol‐containing product with another. The interventions had to be provided for at least 1 year.

Comparators considered appropriate were non‐cariogenic placebos without claims of active anti‐caries properties, or no intervention. For example, sorbitol is hypo‐acidogenic and generally considered non‐cariogenic, but not anti‐cariogenic (Hogg 1991; Birkhed 1984). Whereas it has been suggested that erythritol possesses similar anti‐caries properties to xylitol (Mäkinen 2005; Mäkinen 2011). Known cariogenic sweeteners (sucrose, glucose and fructose), were considered to be inappropriate comparators.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Change in dental caries increment (dental caries is defined as clinical or radiographic lesions or both recorded at the dentine level), determined by change from baseline in the following: decayed‐filled teeth/surfaces (DFT/DFS) or decayed‐missing‐filled teeth/surfaces (DMFT/DMFS) for permanent teeth; or dmfs/d(e)fs and dmft/d(e)ft for deciduous teeth (where the 'e' indicates an extracted tooth). Data on permanent and deciduous teeth were to be analysed separately. The summary statistics for the indices were those for all permanent and deciduous teeth erupted at the start and erupting over the course of the study.

Number of participants with and without dental caries increment.

Secondary outcomes

Quality of life (QOL)

Patient satisfaction

Cost (including use of health service resources, such as visits to dental care units, length of dental treatment time)

Adverse effects (e.g. gastrointestinal complaints, discolouration of teeth, pain and discomfort)

Search methods for identification of studies

For the identification of studies to be included or considered for this review, we developed detailed search strategies for each database searched. These were based on the search strategy developed for MEDLINE (Appendix 3) but revised appropriately for each database to take account of differences in controlled vocabulary and syntax rules. The subject search used a combination of controlled vocabulary and free text terms.

The search strategy combined the subject search with the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy (CHSSS) for identifying reports of randomised controlled trials (2008 revision;as published in box 6.4.c in theCochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, version 5.1.0, updated March 2011) (Higgins 2011).

Language

We did not place any restrictions on language or date of publication when searching the electronic databases. Any non‐English papers identified were translated and assessed for eligibility.

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases:

the Cochrane Oral Health Group's Trials Register (to 14 August 2014) (see Appendix 1);

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library, 2014, Issue 7) (see Appendix 2);

MEDLINE via OVID (1946 to 14 August 2014) (see Appendix 3);

EMBASE via OVID (1980 to 14 August 2014) (see Appendix 4);

CINAHL via EBSCOhost (1980 to 14 August 2014) (see Appendix 5);

Web of Science Conference Proceedings (1990 to 14 August 2014) (see Appendix 6);

ProQuest Dissertations and Theses (1861 to 14 August 2014) (see Appendix 7).

Searching other resources

Handsearching

Only the results of handsearching done as part of the Cochrane Worldwide Handsearching Programme and uploaded to CENTRAL were included. See the Cochrane Masterlist for details of the journal issues searched to date.

Unpublished studies

We searched the following databases for ongoing trials:

US National Institutes of Health Trials Register (http://clinicaltrials.gov) (to 14 August 2014) (see Appendix 8);

The WHO Clinical Trials Registry Platform (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/default.aspx) (to 14 August 2014) (see Appendix 9).

To identify possible unpublished or ongoing studies, we contacted experts and organisations known in this field.

We examined the reference lists of included clinical trials were to help identify additional studies not identified by the electronic searches.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed the abstracts of retrieved studies. We obtained full text copies of studies deemed to be relevant, potentially relevant or for which there was insufficient information in the title and abstract to make a clear decision. Two review authors independently assessed the full text papers and any disagreements on the eligibility of studies were resolved through discussion and consensus. If necessary, a third review author was consulted.

We excluded any studies not fulfilling the inclusion criteria and the reasons for exclusion are noted in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Data extraction and management

As highlighted in a previous Cochrane review (Marinho 2013), dental caries increment can be reported differently in different trials. We adopted the set of a priori rules developed by the authors of that review to choose the primary outcome data for analysis from each study: data on surface level were chosen over data on tooth level, decayed‐filled tooth surfaces (DFS) data were to be chosen over decayed‐missing‐filled tooth surfaces (DMFS) data; data for 'all surface types combined' were chosen over data for 'specific types' only; data for 'all erupted and erupting teeth combined' were chosen over data for 'erupted' only, and these over data for 'erupting' only; data from 'clinical and radiological examinations combined' were chosen over data from 'clinical' only, and these over 'radiological' only; data for dentinal or cavitated caries lesions were chosen over data for enamel or non‐cavitated lesions; net caries increment data was chosen over crude (observed) increment data; and follow‐up nearest to three years (often the one at the end of the treatment period) was chosen over all other lengths of follow‐up, unless otherwise stated. When no specification was provided with regard to the methods of examination adopted, diagnostic thresholds used, groups of teeth and types of tooth eruption recorded, and approaches for reversals adopted, the primary choices described above were assumed.

Study details and outcomes data were collected independently and in duplicate by two review authors using a predetermined form designed for this purpose. We entered study details into Characteristics of included studies tables and outcome data into additional tables or forest plots in Review Manager (RevMan) (RevMan 2014). We discussed any disagreements and, if necessary, we consulted a third review author to resolve any inconsistencies.

We extracted the following details.

Trial methods: (a) method of allocation; (b) masking of participants and outcomes; (c) exclusion of participants after randomisation and proportion of losses at follow‐up.

Setting and when the trial was conducted.

Participants: (a) country of origin; (b) sample size; (c) age; (d) gender; (e) inclusion and exclusion criteria (symptoms and duration, information on diagnosis verification).

Intervention and control: type and procedural information.

Outcomes: primary and secondary outcomes are outlined in the Types of outcome measures section of the review. We reported the longest term data available.

If stated, the sources of funding of any of the included studies were recorded.

This information was utilised to assess the clinical diversity and generalisability of any included trials.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed the risk of bias of the included studies using a simple contingency form following the domain‐based evaluation described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We subsequently compared and discussed our independent evaluations, and resolved any disagreements through discussion. If necessary, we consulted a third review author to resolve any disagreements.

We assessed the following domains:

sequence generation (selection bias);

allocation concealment (selection bias);

blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias);

blinding of outcome assessors (detection bias);

incomplete outcome data (attrition bias);

selective outcome reporting (reporting bias);

other bias.

We reported the assessments for each included study in the corresponding sections of the risk of bias tables.

We also categorised the overall risk of bias of individual studies. Individual studies were categorised as being at: low, high or unclear risk of bias according to the following:

low risk of bias (plausible bias unlikely to seriously alter the results) if all domains were at low risk of bias;

unclear risk of bias (plausible bias that raises some doubt about the results) if one or more domains had an unclear risk of bias; or

high risk of bias (plausible bias that seriously weakens confidence in the results) if one or more domains were at high risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

The following section has been taken from the Cochrane review on fluoride varnishes as it was considered appropriate for this review (Marinho 2013).

Dental caries outcomes

The chosen measure of treatment effect was the prevented fraction (PF), which is the mean increment in the controls minus the mean increment in the treated group divided by the mean increment in the controls. For an outcome such as dental caries increment (where discrete counts are considered to approximate to a continuous scale and are treated as a continuous outcome) this measure is considered more appropriate than the mean difference or standardised mean difference since it allows combination of different ways of measuring dental caries increment and a meaningful investigation of heterogeneity between trials. It is also simple to interpret.

Other outcomes

For dichotomous outcomes (for example, with/without caries increment), the estimate of effect of an intervention was expressed as a risk ratio (RR) together with 95% confidence interval (CI). For continuous outcomes, means and standard deviations were used to summarise the data for each group using mean differences and 95% CIs.

Unit of analysis issues

We used mean dental caries increments which were calculated for each patient. We included cluster randomised trials and used the methods outlined in section 16.3.4 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions to take the clustering into account if the published report did not do so. This involves using an intra‐class correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.05 (this was the value used in a similar Cochrane review of fluoride varnishes for preventing caries (Marinho 2013)) to estimate the design effect. This was then used to adjust the sample size of the control and intervention groups (and also the number of events in the case of dichotomous data).

Dealing with missing data

We contacted trial authors to retrieve missing data when necessary/feasible. If an agreement could not be reached then data was excluded until clarification was available. For missing standard deviations relating to caries increments we intended to use the approach adopted in the topical fluoride reviews (Marinho 2013): these were to be imputed through linear regression of log standard deviations on log mean caries increments where appropriate. This is a suitable approach for dental caries prevention studies since, as they follow an approximate Poisson distribution, dental caries increments are closely related (similar) to their standard deviations (van Rijkom 1998). Otherwise, methods in section 7.7.3 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions were used to estimate missing standard deviations (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of heterogeneity

If a sufficient number of studies were included in any meta‐analyses, clinical heterogeneity would have been assessed by examining the characteristics of the studies, and the similarity between the types of participants, the interventions and the outcomes as specified in the criteria for included studies. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using a Chi² test and quantified using the I² statistic, where I² values over 50% indicated moderate to high heterogeneity (Higgins 2003). Heterogeneity was considered statistically significant if the P value was less than 0.10 for the Chi² test.

Assessment of reporting biases

If a sufficient number of studies were included in any meta‐analyses, publication bias was to be assessed according to the recommendations on testing for funnel plot asymmetry (Egger 1997) as described in section 10.4.3.1 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). If asymmetry was identified, other possible causes would have been assessed.

Data synthesis

Meta‐analysis was conducted only if there were studies of similar comparisons reporting the same outcome measures.

Dental caries increments

The meta‐analysis was conducted using inverse variance weighted averages. Variances were estimated using the formula presented in Dubey 1965, which is more suitable for use in a weighted average and should provide a reasonable approximation for large sample sizes. A fixed‐effect model was used as there were less than four studies in the meta‐analysis. Random‐effects models were to be used if there were four or more studies in a meta‐analysis.

Other outcomes

Risk ratios were to be combined for dichotomous data, and mean differences for continuous data, using random‐effects models if there were at least four studies in a meta‐analysis;fixed‐effect models would have been used if there were less than four studies.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

The following subgroup analyses were planned for the dental caries increments.

Preparation type (toothpastes, mouthrinses, chewing gum, etc)

Age

Doses and concentration of preparations

Deciduous and permanent teeth

Sensitivity analysis

If a sufficient number of studies were included in any meta‐analyses, sensitivity analyses would have been undertaken to assess the robustness of the results by excluding studies with an unclear or high risk of overall bias.

Presentation of main results

We aimed to develop a summary of findings table for each comparison and for the main outcomes of this review following GRADE methods (GRADE 2004), and using GRADEPro software. The quality of the body of evidence was assessed with reference to the overall risk of bias of the included studies, the directness of the evidence, the inconsistency of the results, the precision of the estimates, and the risk of publication bias. We categorised the quality of the body of evidence for each of the main outcomes for each comparison as high, moderate, low or very low.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

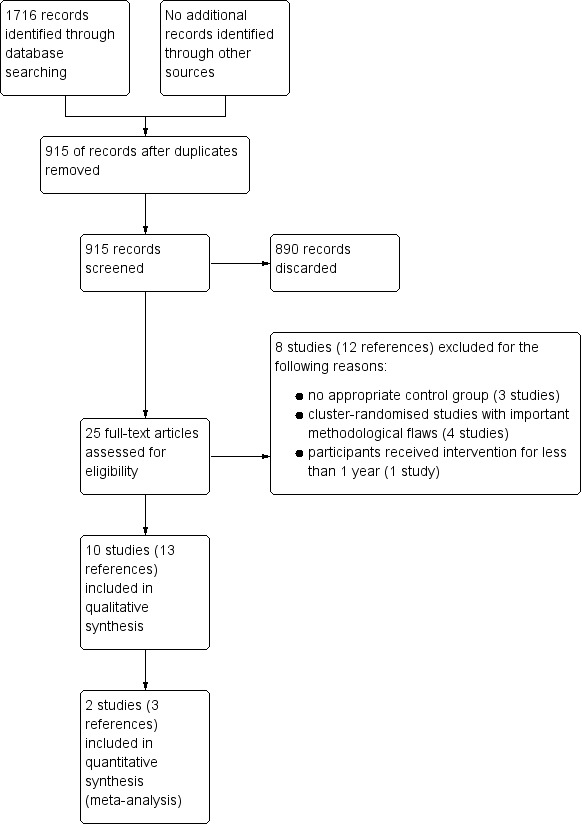

The electronic searches retrieved 1716 references to studies. After removing duplicates, this figure was reduced to 915. We examined the titles and abstracts of these references and discarded all but 25 with no further assessment. We obtained full‐text copies of these 25 potentially relevant studies and we excluded 8 of them at this stage (12 references). Ten studies (13 references) met the inclusion criteria for this review. We present this process as a flow chart in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Ten studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in this review (see Characteristics of included studies tables).

Characteristics of the trial designs and settings

Eight studies were of parallel design, with the remaining two studies using the cluster‐randomised design (Honkala 2014; Lenkkeri 2012). Of the eight parallel studies, three were multicentre (Bader 2013; Sintes 1995; Sintes 2002), three were conducted at single centres (Oscarson 2006; Petersson 1991; Zhan 2012), and two were unclear in this regard (Milgrom 2009; Taipale 2013). The studies were conducted in the USA (Bader 2013; Zhan 2012), Finland (Lenkkeri 2012; Taipale 2013), Sweden (Oscarson 2006; Petersson 1991), Costa Rica (Sintes 1995; Sintes 2002), Estonia (Honkala 2014), and the Republic of the Marshall Islands (Milgrom 2009). Four studies were carried out in a dental clinical setting (Bader 2013; Oscarson 2006; Petersson 1991; Zhan 2012), two studies in a school setting (Sintes 1995; Sintes 2002), and two studies were carried out in a combination of schools (where the intervention was given) and dental clinics (where the clinical examinations took place) (Honkala 2014; Lenkkeri 2012). The remaining two studies were carried out in a community setting (Milgrom 2009) and a healthcare centre setting (Taipale 2013).

Eight studies performed sample size calculations (Bader 2013; Honkala 2014; Lenkkeri 2012; Milgrom 2009; Petersson 1991; Sintes 1995; Taipale 2013; Zhan 2012). However, in two of these studies, the calculation was based on an outcome which was not of interest in this review (Taipale 2013; Zhan 2012). One study only carried out a post‐investigation sample size analysis (Oscarson 2006), and the remaining study did not mention sample size calculations (Sintes 2002).

Two studies only stated that they had received non‐industry funding (Bader 2013; Oscarson 2006). Three studies stated that they received non‐industry funding but that industry supplied the interventions (Milgrom 2009; Taipale 2013; Zhan 2012). Four studies were clearly industry funded, in other words industry provided economical support (Honkala 2014; Petersson 1991; Sintes 1995; Sintes 2002). The remaining study only stated that industry provided the interventions (Lenkkeri 2012).

Characteristics of the participants

There were 7969 participants randomised to interventions (including only the intervention groups relevant to this review), of which 5903 were included in the studies' analyses. One study investigated the effects of xylitol in adults (Bader 2013), whilst the remaining studies only included children. Five of these studies included children ranging from 8 to 13 years of age (Honkala 2014; Lenkkeri 2012; Petersson 1991; Sintes 1995; Sintes 2002), with the remaining four studies including younger children ranging from 1 month to 3 years of age (Milgrom 2009; Oscarson 2006; Taipale 2013; Zhan 2012). Approximately two thirds of the participants were females in the study on adults (Bader 2013), whilst the other studies all had roughly equal proportions of males and females.

Characteristics of the interventions and comparisons

Four studies involved the use of xylitol products (defined as lozenges, sucking tablets and candies) which were to be sucked (Bader 2013; Honkala 2014; Lenkkeri 2012; Oscarson 2006). A further study also involved xylitol tablets, but they were administered using a slow‐release pacifier/dummy, or crushed on a spoon if the child would not accept a pacifier (Taipale 2013). Three studies investigated xylitol‐containing fluoride toothpastes (Petersson 1991; Sintes 1995; Sintes 2002). One study tested a xylitol syrup (Milgrom 2009), whilst the remaining study tested xylitol wipes (Zhan 2012).

The dosage of xylitol ranged from 200 to 600 mg per day to 8 g per day. The total daily dosage was unclear in the three toothpaste studies, as it was reported as a percentage of xylitol, at 3% (Petersson 1991), or 10% (Sintes 1995; Sintes 2002). Of the four studies including younger children (baseline mean age ranging from 1 month to 2 years), two used very low daily doses of 200 to 600 mg (Taipale 2013), and 1 g (Oscarson 2006), whilst two used higher daily doses of 4.2 g (Zhan 2012), and 8 g (Milgrom 2009). In two studies with older children (baseline mean age ranging from 8 to 10 years), the daily dose was 7.5 g (Honkala 2014), and 4.7 g (Lenkkeri 2012), and in the adult study, the dose was 5 g per day (Bader 2013). The duration of the intervention ranged from 1 to 3 years. In three studies, the final follow‐up occurred after the participants had ceased to receive the intervention: 1.5 years of intervention with follow‐up at 2 years (Oscarson 2006), and 2 years of intervention with follow‐up at 4 years (Lenkkeri 2012; Taipale 2013).

Xylitol products, with their sweet flavour, cause extra saliva to be produced, especially with lozenges/candies/sucking tablets that are sucked over a period of time. Therefore it is difficult to distinguish how much of any effect is due to the xylitol or the extra saliva that is produced. Thus it would be desirable for studies to have both a control arm using a placebo product and a no treatment control arm. Sorbitol is frequently used as a placebo in xylitol studies as it is neither considered to cause or prevent caries We did not consider any products which are thought to prevent caries (e.g. erythritol) or those which are known to cause caries (e.g. sucrose) as appropriate placebos. Two studies used no treatment in the control arm (Lenkkeri 2012; Oscarson 2006). Two studies used sorbitol which we treated as a placebo control arm (Honkala 2014; Taipale 2013). Two studies stated that they used a placebo, one of which used sucralose as the sweetening agent in the lozenges (Bader 2013), whilst the other used wipes containing no xylitol (Zhan 2012). The three toothpaste studies used entirely appropriate placebos, in that all participants either used a toothpaste with or without xylitol (Petersson 1991; Sintes 1995; Sintes 2002). The remaining study used a lower dose of xylitol for the control group, which was demanded by the internal review committee of the Secretary of Health, but the authors cited evidence that the lower dose (2.67 g per day) would not have an effect on caries incidence (Milgrom 2009).

Characteristics of the outcomes

All ten studies assessed the effects of xylitol products on caries, which was our primary outcome. Five studies reported continuous data in the form of caries increment: three reporting decayed filled surfaces (DFS) (Bader 2013; Sintes 1995; Sintes 2002), and two reporting decayed missing filled surfaces on deciduous teeth (dmfs) (Oscarson 2006), and permanent teeth (DMFS) (Lenkkeri 2012). The latter two studies also reported caries as a dichotomous outcome, in other words whether or not there was an increment (change in caries). Two studies only reported caries as a dichotomous outcome (dmfs increment: yes/no) (Taipale 2013; Zhan 2012). The remaining three studies reported the mean number of decayed primary teeth (Milgrom 2009), the mean number of DFS (Petersson 1991), and the mean number of dmfs (Honkala 2014). One of those studies did not report measures of variance (e.g. standard deviation), which would preclude its inclusion in any meta‐analysis (Petersson 1991). Another study combined deciduous and permanent teeth, which we considered inappropriate (Honkala 2014). If the authors had presented the results as the mean incremental change, the results would show a large reduction in caries.

Thresholds for diagnosis of caries varied between the studies, with different scoring systems used. Two studies defined caries to include non‐cavitated enamel lesions (Taipale 2013; Zhan 2012). Four studies defined caries as a visible breakdown in the enamel wall (Bader 2013; Oscarson 2006; Sintes 1995; Sintes 2002). One study reported enamel and dentine caries separately (Honkala 2014), and one study reported only dentine caries (Lenkkeri 2012). One study defined caries as cavitated lesions, but did not specify if this included enamel or dentine (Milgrom 2009), and one reported combined "initial and gross caries," but it is unclear how this relates to either enamel or dentine lesions (Petersson 1991).

Three studies did not mention adverse/side effects (Oscarson 2006; Petersson 1991; Taipale 2013). Of the seven studies that did mention adverse effects, two did not present the data in a usable format (Lenkkeri 2012; Milgrom 2009), one reported raw data on a publicly accessible website (Bader 2013), and the remaining four just stated that there were none observed or reported (Honkala 2014; Sintes 1995; Sintes 2002; Zhan 2012). Adverse effects include sores in the mouth, cramps, bloating, constipation, flatulence, and loose stool or diarrhoea.

No other secondary outcomes of this review were reported.

Excluded studies

We excluded eight studies from this review (see Characteristics of excluded studies tables). Of four excluded cluster‐randomised studies, two were excluded because some of the clusters were selectively allocated rather than randomly allocated (Alanen 2000b; Kandelman 1990), and two were excluded because there were not enough clusters per treatment arm, which we considered an inappropriate design (Chi 2014; Machiulskiene 2001). Three studies had no appropriate control group: one used sucrose which causes caries (Scheinin 1975), one compared xylitol used for two years with xylitol used for three years against fissure sealants (Alanen 2000), and one used an extra toothbrushing after lunch with fluoride toothpaste (Kovari 2003). The remaining study appeared to be eligible from the trials record on ClinicalTrials.gov, but when the author kindly provided us with a prepublication copy, it became clear that the intervention was not given for a minimum of one year (Lee 2014).

Risk of bias in included studies

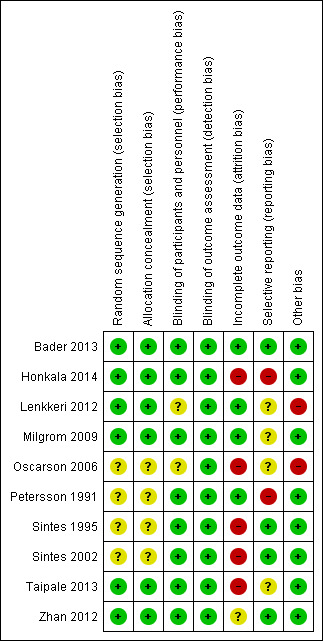

Allocation

Six studies gave adequate descriptions of both the method of random sequence generation and of allocation concealment, so we rated them as having a low risk of bias for both domains and therefore overall for selection bias (Bader 2013; Honkala 2014; Lenkkeri 2012; Milgrom 2009; Taipale 2013; Zhan 2012). The remaining four studies did not describe the methods used for random sequence generation or for allocation concealment, so we rated them as having an unclear risk of bias for both domains and overall for selection bias (Oscarson 2006; Petersson 1991; Sintes 1995; Sintes 2002).

Blinding

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias)

Two studies used no treatment for the control group and therefore it was not possible to blind the participants or personnel (Lenkkeri 2012; Oscarson 2006). Whilst this could not impact upon the outcome assessment (which was blinded in all cases and caries outcomes were not assessed by the participants), we could not rule out that there might have been an effect on behaviour of the participants or their carers or both, which could potentially affect the outcome. We assessed these two studies as having an unclear risk of bias. The remaining eight studies were all adequately blinded through the use of active controls which were unidentifiably different, and we assessed them as having a low risk of bias.

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias)

All 10 studies involved blinded outcome assessment and we rated them as having a low risk of bias.

Incomplete outcome data

We assessed four studies as being at low risk of bias for this domain because attrition was low and was roughly equal between groups, with similar reasons (Bader 2013; Lenkkeri 2012; Milgrom 2009; Petersson 1991). We assessed one study as having an unclear risk of bias for this domain because, although all participants were included in the analysis on an intention‐to‐treat basis, this involved the use of imputation rules and the attrition was appreciably higher in one group (Zhan 2012). The remaining five studies were assessed as having a high risk of bias because either the attrition was appreciably higher in one group (Oscarson 2006), or there was a very high overall rate of attrition which we felt may have led to a distortion of the effect estimate (Honkala 2014; Sintes 1995; Sintes 2002; Taipale 2013). We appreciate that cut‐off points for attrition decisions may be considered to be subjective and therefore we acknowledge that readers of the review may wish to interpret the risk of bias for this domain differently.

Selective reporting

We assessed four studies as being at low risk of bias for this domain because they either presented outcomes in the study report in a way amenable to meta‐analysis (Sintes 1995; Sintes 2002; Zhan 2012), or on a publicly accessible website (Bader 2013). The authors of the latter study also kindly provided us with the exact data we requested. We rated two studies as having a high risk of bias for the reason that we were unable to use the data for the primary outcome of caries in a meta‐analysis (Honkala 2014; Petersson 1991). We rated the remaining four studies as having an unclear risk of bias because we would expect studies of xylitol products to fully assess adverse/side effects, but they either did not mention them (Oscarson 2006; Taipale 2013), or they mentioned them but did not provide data that could be used in a meta‐analysis (Lenkkeri 2012; Milgrom 2009).

Other potential sources of bias

Eight studies were considered to be free of any other potential sources of biases and we rated them as having a low risk of bias. We rated the remaining two studies as having a high risk of bias because of confounding, in that they did not use a placebo, and therefore we could not exclude the possibility that some of the effects would be due to salivary stimulation as a result of sucking the products (Lenkkeri 2012; Oscarson 2006).

Overall risk of bias

One study was at low overall risk of bias (Bader 2013).

Two studies were at unclear overall risk of bias (Milgrom 2009; Zhan 2012).

Seven studies were at high overall risk of bias (Honkala 2014; Lenkkeri 2012; Oscarson 2006; Petersson 1991; Sintes 1995; Sintes 2002; Taipale 2013).

We present the results of the risk of bias assessments graphically in Figure 2.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Adults

Xylitol lozenges versus control lozenges

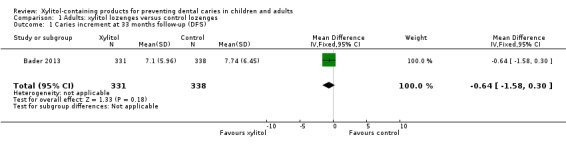

One study, at low risk of bias and analysing 669 participants, compared xylitol (5 g per day) lozenges with control lozenges over 33 months (Bader 2013). There was no difference in caries increment for DFS (mean difference (MD) ‐0.64, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐1.58 to 0.30, P value = 0.18) (Analysis 1.1). This translates to a non‐significant prevented fraction (PF) of 8% in favour of the xylitol group (Table 2).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Adults: xylitol lozenges versus control lozenges, Outcome 1 Caries increment at 33 months follow‐up (DFS).

1. Prevented fractions (PF) for caries incremental data.

| Comparison (number) | Increment (Study) | PF (95% CI) | Notes |

| Adults | |||

| Xylitol lozenges versus control lozenges (1.1) | 33‐month caries increment (Bader 2013) | 0.08 (–0.03 to 0.20) | 8% reduction in caries in test group |

| Children | |||

| Xylitol lozenges versus no treatment (2.1) | 4 year caries increment (Lenkkeri 2012) |

‐0.10 (‐0.59 to 0.39) | 10% increase in caries in test group compared to control |

| Xylitol topical oral syrup versus control syrup (3.1) | Caries in primary teeth over 1 year follow‐up (Milgrom 2009) | 0.58 (0.33 to 0.83) | 58% reduction in caries in test group |

| Xylitol sucking tablets versus no treatment (4.1) | 2 year caries increment (Oscarson 2006) | 0.53 (0.001 to 1.04) | 53% reduction in caries in test group |

| Xylitol plus fluoride toothpaste versus fluoride toothpaste (5.1) | 2.5 to 3 year caries increment (Sintes 1995) | 0.12 (0.06 to 0.18) | 12% reduction in caries in test group |

| 2.5 to 3 year caries increment (Sintes 2002) | 0.14 (0.05 to 0.23) | 14% reduction in caries in test group | |

CI = confidence interval

Patterns of adverse effects (sores in the mouth, cramps, bloating, constipation, flatulence, and loose stool or diarrhoea) were similar for both groups.

Children

Xylitol candy versus control (sorbitol) candy

One study, at high risk of bias and analysing 252 children, compared xylitol (7.5 g per day) candy with control (sorbitol) candy over 36 months (Honkala 2014). We were unable to use the data in our analyses as the authors combined the primary/deciduous and permanent teeth and reported the mean number of decayed missing filled surfaces. We would require them to report the mean increment and standard deviation for either primary or permanent teeth in order to use the data in a meta‐analysis.

The authors reported that there were no adverse effects for either group.

Xylitol lozenges versus no treatment

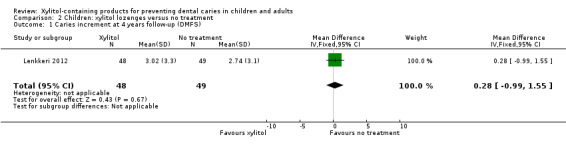

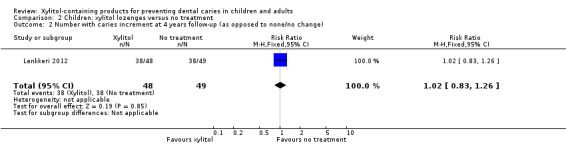

One study, at high risk of bias and analysing 200 children, compared xylitol (4.7 g per day) lozenges with no treatment over 24 months, with 48 month follow‐up (Lenkkeri 2012). There was no difference in caries increment for DMFS(MD 0.28, 95% CI ‐0.99 to 1.55, P value = 0.67) (Analysis 2.1). This translates to a non‐significant PF of 10% in favour of the no treatment group (Table 2). There was also no difference in the number of children with a caries increment, in other words those with caries occurring between baseline and final follow‐up (risk ratio (RR) 1.02, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.26, P value = 0.85) (Analysis 2.2).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Children: xylitol lozenges versus no treatment, Outcome 1 Caries increment at 4 years follow‐up (DMFS).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Children: xylitol lozenges versus no treatment, Outcome 2 Number with caries increment at 4 years follow‐up (as opposed to none/no change).

There were no usable data presented for adverse effects.

Xylitol syrup versus control (low‐dose xylitol) syrup

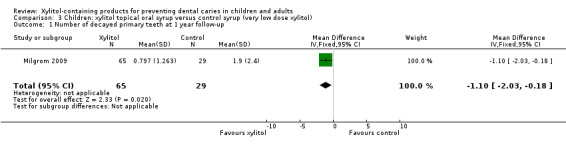

One study, with an unclear risk of bias and analysing 94 infants, compared xylitol (8 g per day) syrup with low‐dose xylitol (2.67 g per day) syrup over 12 months (Milgrom 2009). The higher dose of xylitol syrup resulted in a statistically significant reduction in the mean number of decayed primary teeth (MD ‐1.10, 95% CI ‐2.03 to ‐0.18, P value = 0.02) (Analysis 3.1). Using PF, this translates to a 58% reduction in caries (Table 2).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Children: xylitol topical oral syrup versus control syrup (very low dose xylitol), Outcome 1 Number of decayed primary teeth at 1 year follow‐up.

Adverse effects were not reported in a usable format but the reported rates of loose stools and diarrhoea were very similar. There were no serious adverse effects experienced during the study.

Xylitol sucking tablets versus no treatment

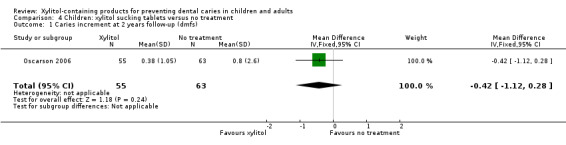

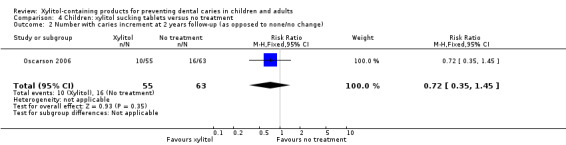

One study, at high risk of bias and analysing 118 infants, compared xylitol (1 g per day) sucking tablets with no treatment over 18 months, with a 24 month follow‐up (Oscarson 2006). There was no difference in caries increment for dmfs (MD ‐0.42, 95% CI ‐1.12 to 0.28, P value = 0.24) (Analysis 4.1), although when this was converted into PF it was marginally statistically significant, and equated to a 53% reduction in caries in favour of the xylitol group (Table 2). There was also no difference in the number of infants with a caries increment (RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.35 to 1.45, P value = 0.35) (Analysis 4.2).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Children: xylitol sucking tablets versus no treatment, Outcome 1 Caries increment at 2 years follow‐up (dmfs).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Children: xylitol sucking tablets versus no treatment, Outcome 2 Number with caries increment at 2 years follow‐up (as opposed to none/no change).

No other outcomes were considered in this study.

Xylitol toothpaste versus control toothpaste

Three studies, all at high risk of bias, compared fluoride toothpastes containing xylitol with fluoride‐only toothpastes over 30 to 36 months (Petersson 1991; Sintes 1995; Sintes 2002). One of the studies, analysing 248 children, compared low‐fluoride plus 3% xylitol (daily dosage unclear) with low‐fluoride, and normal‐level fluoride plus 3% xylitol with normal‐level fluoride (Petersson 1991). The authors did not report data in a usable format, but found no difference in the number of DFS between any group. The study did not consider any other outcomes.

We were able to pool the data from the other two studies in a meta‐analysis, which revealed that fluoride toothpaste containing 10% xylitol (daily dosage unclear) resulted in a 13% reduction in caries increment for DFS (PF ‐0.13, 95% CI ‐0.18 to ‐0.08, P value < 0.00001, 4216 children analysed) (Analysis 5.1; Analysis 5.2).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Children: xylitol plus fluoride toothpaste versus fluoride toothpaste, Outcome 1 Caries increment at 2.5 to 3 years follow‐up (Prevented Fraction).

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Children: xylitol plus fluoride toothpaste versus fluoride toothpaste, Outcome 2 Caries increment at 2.5 to 3 years follow‐up (DFS).

Both studies reported that there were no adverse effects in either group.

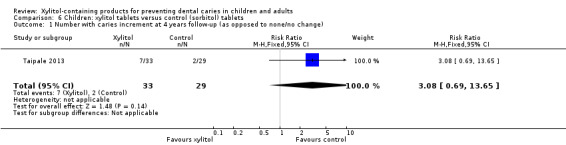

Xylitol tablet versus control (sorbitol) tablet

One study, at high risk of bias and analysing 62 infants, compared xylitol (200 to 600 mg per day) tablets administered via a slow‐release pacifier/dummy or crushed up on a spoon with control (sorbitol) tablets administered in the same way over 24 months, with a 48 month follow‐up (Taipale 2013). There was no difference in the number of infants with a caries increment for dmfs (RR 3.08, 95% CI 0.69 to 13.65, P value = 0.14) (Analysis 6.1).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Children: xylitol tablets versus control (sorbitol) tablets, Outcome 1 Number with caries increment at 4 years follow‐up (as opposed to none/no change).

No other outcomes were considered in this study.

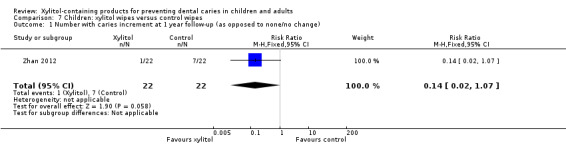

Xylitol wipes versus control wipes

One study, at unclear risk of bias and analysing 44 infants, compared xylitol (4.2 g per day) wipes with control wipes over 12 months (Zhan 2012). There was no difference in the number of infants with a caries increment for dmfs (RR 0.14, 95% CI 0.02 to 1.07, P value = 0.06) (Analysis 7.1).

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Children: xylitol wipes versus control wipes, Outcome 1 Number with caries increment at 1 year follow‐up (as opposed to none/no change).

The authors reported that there were no adverse effects for either group.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We included 10 studies which met the inclusion criteria for this review. For each comparison and outcome considered in the review, we assessed the quality of the body of evidence using the GRADE method, which takes into account the risk of bias of the included studies, the directness of the evidence, the consistency of the results (heterogeneity), the precision of the effect estimates, and the risk of publication bias (GRADE 2004). We only present a 'Summary of findings' table where we were able to perform a meta‐analysis. This was only possible for xylitol toothpastes, and our assessment is provided in the Table 1.

There is low quality evidence that fluoride toothpastes containing xylitol may reduce caries in children when compared to fluoride‐only toothpastes. There is also a very small body of low quality evidence, consisting of one small study, that a high dose of xylitol syrup reduces caries in infants when compared to a low dose. We considered the evidence on xylitol syrups insufficient to make any conclusions.

There was insufficient evidence, from single studies (mostly with small sample sizes), to determine a difference in caries between the following groups, and thus the uncertainty associated with the effect estimates resulted in them being compatible with both a reduction and an increase in caries associated with xylitol.

Xylitol lozenges versus control lozenges in adults (low quality body of evidence)

Xylitol lozenges versus no treatment in children (very low quality body of evidence).

Xylitol sucking tablets versus no treatment in infants (very low quality body of evidence).

Xylitol tablets versus control (sorbitol) tablets in infants (very low quality body of evidence).

Xylitol wipes versus control wipes in infants (low quality body of evidence).

We did not rate the body of evidence for xylitol candy versus control (sorbitol) candy because we did not agree with the combining of caries scores for primary and permanent teeth.

Four studies reported that there were no adverse effects from any of the interventions. Two studies reported similar rates of adverse effects between study arms. The remaining studies either mentioned adverse effects but did not report any usable data, or did not mention them at all. Adverse effects include sores in the mouth, cramps, bloating, constipation, flatulence, and loose stool or diarrhoea.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

There is limited available evidence on the effects of xylitol products. It was surprising that there were no eligible randomised trials testing xylitol chewing gums against either no treatment or a non‐cariogenic control. We were only able to pool two studies in a meta‐analysis (both of toothpastes with and without xylitol) and these two studies were carried out by the same researchers in the same study population (school children in the same area of Costa Rica). Therefore the results may not have much external validity. Interestingly, the children were instructed to rinse thoroughly with water after brushing, a practice which is not generally recommended for toothbrushing, and which would reduce the effects of both the fluoride and the xylitol (DBOH 2014).

The rest of the included studies involved different xylitol products, comparators, and outcomes, and therefore none were similar enough to combine their results in a meta‐analysis. It was disappointing that no studies have been replicated in different populations and settings in order to allow more robust conclusions to be made. Furthermore, there is little evidence from eligible randomised controlled trials of the effects of xylitol in adults.

Sugar‐free gums, sweets, mints and other products are well known for their gastrointestinal side effects (e.g. bloating/wind, diarrhoea, etc) and therefore we would expect all studies to report this as an outcome, and in a usable format for meta‐analysis (i.e. by group/intervention and at the participant level, rather than double‐counting people who may have experienced several adverse events). Unfortunately, reporting of adverse effects was generally poor and we did not obtain much usable data.

The dosage of xylitol in the included studies varied from 200 to 600 mg per day to 8 g per day, or 3% to 10% in the toothpaste studies. It has been suggested in the xylitol literature that there may be a daily dose "threshold" of 5 to 6 g per day, divided between three or more daily doses, below which xylitol is not effective against S. Mutans and therefore would be unlikely to reduce caries levels (Fontana 2012; Milgrom 2006; Söderling 2009b). There were three studies included in this review that administered daily doses of 5 g or more (Bader 2013; Honkala 2014; Milgrom 2009). Only one of these studies was among the three studies that showed a positive preventive effect (Milgrom 2009; Sintes 1995; Sintes 2002). The dose in the Milgrom 2009 syrup study was indeed the highest of the reviewed studies, at 8 g per day. The toothpaste studies both used 10% xylitol (Sintes 1995; Sintes 2002), but it is unclear what this would equate to as a daily dose, as it would depend on the amount of toothpaste used.

Considering the three possible ways in which xylitol may reduce caries (substitution of cariogenic free sugars, saliva stimulation, and a possible active anti‐caries effect), it was surprising to see trials that did not include a placebo arm (Oscarson 2006; Lenkkeri 2012). Without a placebo arm, it is impossible to conclude that there are any specific anti‐caries effects of xylitol over and above sugar substitution and saliva stimulation. Whilst there is value in sugar substitution and saliva stimulation compared to no treatment as a public health measure; this is not what the studies are investigating when they discuss specific anti‐caries effects, and effective dosages of one sugar alcohol over another.

Quality of the evidence

The body of evidence that we identified does not allow for any robust conclusions about the effects of xylitol to be made. Although we included 10 studies, which analysed a total of 5903 participants, the majority of the participants (4216) were included in the two meta‐analysed toothpaste studies, with the remainder falling into several single‐study comparisons which provided no clear evidence. One study was assessed as being at low risk of bias, two had an unclear risk of bias, and seven were assessed as being at high risk of bias. When such risk of bias issues were considered alongside the fact that the studies in each comparison/outcome were either single small studies (leading to serious imprecision) or had 95% confidence intervals including both an effect favouring the intervention and the control (or both of these issues), this resulted in us rating the evidence as low to very low quality. These GRADE ratings can be interpreted as meaning that there is a lack of confidence in the effect estimates and further research is highly likely to change the estimates, and our confidence in them. The body of evidence on xylitol‐containing fluoride toothpaste did not have the problem of imprecision due to large sample sizes, but instead was affected by high risk of bias and being conducted by the same authors in the same population/setting.

Potential biases in the review process

Searching of multiple databases, with no language or date restrictions, was intended to limit bias by including all relevant studies. Some studies did not have usable data, and this introduces bias into the review as it distorts our overall view of the effects of xylitol. Our subjective assessments of what constitutes a high attrition rate could also be interpreted by some readers as bias. However, we have presented all the information, rationale, and our assessments, with the intention of transparency and to allow the reader to reach a different interpretation.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Several recent reviews have considered the caries‐preventive effect of xylitol. Their inclusion criteria differ from the inclusion criteria of this review in that they all included non randomised controlled clinical trials. However, only one out of four concluded any benefit from xylitol.

The most positive systematic review compared xylitol containing gums to no gum (Deshpande 2008). The authors carried out a meta‐analysis of six studies and found a PF of 58.66% (95% confidence interval 35.42 to 81.90). Four of these studies were not randomly allocated, and the two studies that were randomised trials were excluded from this review due to inappropriate randomisation procedures (Alanen 2000b; Machiulskiene 2001). The authors concluded that "research evidence supports the use of polyol‐containing gum as part of a normal oral hygiene routine to prevent dental caries."

A non‐systematic literature review of sugar alcohols (van Loveren 2004) found there to be "no evidence for a caries‐therapeutic effect" from xylitol, and that any caries‐preventive effects were probably due to saliva stimulation. None of the studies were eligible for inclusion in this review as they were either not randomised trials, or compared used known cariogenic sweeteners as the comparator (e.g. sucrose (Scheinin 1975)).

A systematic review concerning the preventive effects of xylitol candies and lozenges included three studies, two of which showed a benefit (Antonio 2011). Two were not eligible for inclusion in our review as the control and intervention groups were not chosen randomly, and the third was excluded as described above (Alanen 2000b). The authors concluded that more "well designed randomized studies" are needed as the three trials did not provide strong evidence.

A non‐systematic literature review of the clinical evidence for polyol efficacy (Milgrom 2012) found that "many questions remain on the efficacy of polyols," and that higher quality studies are required.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

We found some low quality evidence to suggest that fluoride toothpaste containing xylitol may be more effective than fluoride‐only toothpaste for preventing caries in the permanent teeth of children, and that there are no associated adverse effects from such toothpastes. The effect estimate should be interpreted with caution due to high risk of bias and the fact that it results from two studies that were carried out by the same authors in the same population. The remaining evidence we found is of low to very low quality and is insufficient to determine whether any other xylitol‐containing products can prevent caries in infants, older children, or adults.

Implications for research.

The fact that we are not able to make any clear conclusions as to the effects of xylitol on caries, or any other outcome, demonstrates that more randomised controlled studies are needed. Future studies should be planned and carried out according to SPIRIT 2013 guidelines, and reported according to CONSORT 2010 guidelines. Trial protocols should be registered in order to reduce the risk of publication bias and duplication of effort. Studies should also be led by independent researchers with no influence from industry.

Authors should decide if they are testing a public health intervention of a sugar‐free chewing gum, lozenge or pastille compared to no intervention, or if they are wishing to make specific claims about any specific anti‐caries effects attributable to xylitol. In the latter case, studies require a placebo arm. This is because we cannot be sure about how much of any reduction in caries is due to the increased production of saliva or the xylitol product.

We recommend that authors continue to test a range of vehicles to deliver xylitol, and at a range of doses, to further investigate the possible importance of a 5 to 6 g per day threshold dose.

Studies should report mean caries increment (using surface rather than tooth level) for each intervention, along with a measure of dispersion such as the standard deviation or standard error of the mean increment. Adverse effects should also be clearly reported at the participant level per group.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Mohammad O Sharif for his help with the protocol and search results screening. We would also like to thank the Cochrane Oral Health Group editorial team and external referees (Professor James D Bader and Mr Derek Richards) for their help in conducting this systematic review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Cochrane Oral Health Group Trials Register Search Strategy

1 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Tooth Demineralization 2 ((teeth and (cavit* or caries or carious or decay* or lesion* or deminerali* or reminerali*)):ti,ab) AND (INREGISTER) 3 ((tooth and (cavit* or caries or carious or decay* or lesion* or deminerali* or reminerali*)):ti,ab) AND (INREGISTER) 4 ((dental and (cavit* or caries or carious or decay* or lesion* or deminerali* or reminerali*)):ti,ab) AND (INREGISTER) 5 ((enamel and (cavit* or caries or carious or decay* or lesion* or deminerali* or reminerali*)):ti,ab) AND (INREGISTER) 6 ((dentin and (cavit* or caries or carious or decay* or lesion* or deminerali* or reminerali*)):ti,ab) AND (INREGISTER) 7 ((root and (cavit* or caries or carious or decay* or lesion* or deminerali* or reminerali*)):ti,ab) AND (INREGISTER) 8 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Dental Plaque Index 9 ((("dental plaque" or DMF or DFS or DFT or DMFT) and (index or indices)):ti,ab) AND (INREGISTER) 10 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Dental Plaque 11 (((dental or tooth or teeth) and plaque):ti,ab) AND (INREGISTER) 12 (#1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or #9 or #10 or #11) AND (INREGISTER) 13 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Sugar Alcohols 14 (("sugar alcohol*" or polyol*):ti,ab) AND (INREGISTER) 15 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Sweetening Agents 16 (sweetener*:ti,ab) AND (INREGISTER) 17 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Xylitol 18 (xylitol:ti,ab) AND (INREGISTER) 19 (#13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 or #18) AND (INREGISTER) 20 (#12 and #19) AND (INREGISTER)

Appendix 2. Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Clinical Trials (CENTRAL) search strategy

#1 [mh "Tooth demineralization"] #2 (tooth near/5 (cavit* or caries or carious or decay* or lesion or deminerali* or reminerali*)) #3 (teeth near/5 (cavit* or caries or carious or decay* or lesion* or deminerali* or reminerali*)) #4 (dental near/5 (cavit* or caries or carious or decay* or lesion* or deminerali* or reminerali*)) #5 (enamel near/5 (cavit* or caries or carious or decay* or lesion* or deminerali* or reminerali*)) #6 (dentin near/5 (cavit* or caries or carious or decay* or lesion* or deminerali* or reminerali*)) #7 (root near/5 (cavit* or caries or carious or decay* or lesion* or deminerali* or reminerali*)) #8 [mh "Dental plaque index"] #9 (("dental plaque" or DMF or DFS or DFT or DMFT) near/3 (index or indices)) #10 [mh "Dental plaque"] #11 ((dental or tooth or teeth) and plaque) #12 {or #1‐#11} #13 [mh "Sugar alcohols"] #14 ("sugar alcohol*" or polyol*) #15 [mh ^"Sweetening agents"] #16 sweetener* #17 [mh Xylitol] #18 xylitol #19 {or #13‐#18} #20 #12 and #19

Appendix 3. MEDLINE (OVID) search strategy

1. (teeth adj5 (cavit$ or caries or carious or decay$ or lesion$ or deminerali$ or reminerali$)).mp. 2. (tooth adj5 (cavit$ or caries or carious or decay$ or lesion$ or deminerali$ or reminerali$)).mp. 3. (dental adj5 (cavit$ or caries or carious or decay$ or lesion$ or deminerali$ or reminerali$)).mp. 4. (enamel adj5 (cavit$ or caries or carious or decay$ or lesion$ or deminerali$ or reminerali$)).mp. 5. (dentin adj5 (cavit$ or caries or carious or decay$ or lesion$ or deminerali$ or reminerali$)).mp. 6. (root adj5 (cavit$ or caries or carious or decay$ or lesion$ or deminerali$ or reminerali$)).mp. 7. exp TOOTH DEMINERALIZATION/ 8. Dental plaque index/ 9. (("dental plaque" or DMF or DFS or DFT or DMFT) adj2 (index or indices)).mp. 10. Dental plaque/ 11. ((dental or tooth or teeth) adj3 plaque).mp. 12. or/1‐11 13. exp Sugar Alcohols/ 14. ("sugar alcohol$" or polyol$).mp. 15. Sweetening Agents/ 16. sweetener$.mp. 17. Xylitol/ 18. xylitol.mp. 19. or/13‐18 20. 12 and 19

The above search will be linked with the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy (CHSSS) for identifying reports of randomised controlled trials (2008 revision) (as published in box 6.4.c in theCochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, version 5.1.0, updated March 2011) (Higgins 2011).

1. randomized controlled trial.pt. 2. controlled clinical trial.pt. 3. randomized.ab. 4. placebo.ab. 5. drug therapy.fs. 6. randomly.ab. 7. trial.ab. 8. groups.ab. 9. or/1‐8 10. exp animals/ not humans.sh. 11. 9 not 10

Appendix 4. EMBASE (Ovid) search strategy

1. (teeth adj5 (cavit$ or caries or carious or decay$ or lesion$ or deminerali$ or reminerali$)).mp. 2. (tooth adj5 (cavit$ or caries or carious or decay$ or lesion$ or deminerali$ or reminerali$)).mp. 3. (dental adj5 (cavit$ or caries or carious or decay$ or lesion$ or deminerali$ or reminerali$)).mp. 4. (enamel adj5 (cavit$ or caries or carious or decay$ or lesion$ or deminerali$ or reminerali$)).mp. 5. (dentin adj5 (cavit$ or caries or carious or decay$ or lesion$ or deminerali$ or reminerali$)).mp. 6. (root adj5 (cavit$ or caries or carious or decay$ or lesion$ or deminerali$ or reminerali$)).mp. 7. Dental caries/ 8. (("dental plaque" or DMF or DFS or DFT or DMFT) adj2 (index or indices)).mp. 9. Tooth plaque/ 10. ((dental or tooth or teeth) adj3 plaque).mp. 11. or/1‐10 12. exp Sugar Alcohol/ 13. ("sugar alcohol$" or polyol$).mp. 14. exp Sweetening Agent/ 15. sweetener$.mp. 16. Xylitol/ 17. xylitol.mp. 18. or/12‐17 19. 11 and 18

The above subject search was linked to the Cochrane Oral Health Group filter for identifying RCTs in EMBASE via OVID:

1. random$.ti,ab. 2. factorial$.ti,ab. 3. (crossover$ or cross over$ or cross‐over$).ti,ab. 4. placebo$.ti,ab. 5. (doubl$ adj blind$).ti,ab. 6. (singl$ adj blind$).ti,ab. 7. assign$.ti,ab. 8. allocat$.ti,ab. 9. volunteer$.ti,ab. 10. CROSSOVER PROCEDURE.sh. 11. DOUBLE‐BLIND PROCEDURE.sh. 12. RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL.sh. 13. SINGLE BLIND PROCEDURE.sh. 14. or/1‐13 15. (exp animal/ or animal.hw. or nonhuman/) not (exp human/ or human cell/ or (human or humans).ti.) 16. 14 NOT 15

Appendix 5. CINAHL (EBSCO) search strategy

S19 (S12 or S13 or S14 or S15 or S16 or S17) AND (S11 AND S18) S18 S12 or S13 or S14 or S15 or S16 or S17 S17 xylitol S16 (MH Xylitol) S15 sweetener* S14 (MH "Sweetening agents") S13 ("sugar alcohol*" or polyol*) S12 (MH "Sugar alcohols") S11 S1 or S2 or S3 or S4 or S5 or S6 or S7 or S8 or S9 or S10 S10 ((dental or tooth or teeth) and plaque) S9 (("dental plaque" or DMF or DFS or DFT or DMFT) and (index or indices)) S8 (MH "Dental Plaque") S7 (root and (cavit* or caries or carious or decay* or lesion* or deminerali* or reminerali*)) S6 (dentin and (cavit* or caries or carious or decay* or lesion* or deminerali* or reminerali*)) S5 (enamel and (cavit* or caries or carious or decay* or lesion* or deminerali* or reminerali*)) S4 (dental and (cavit* or caries or carious or decay* or lesion* or deminerali* or reminerali*)) S3 (teeth and (cavit* or caries or carious or decay* or lesion* or deminerali* or reminerali*)) S2 (tooth and (cavit* or caries or carious or decay* or lesion or deminerali* or reminerali*)) S1 (MH "Tooth demineralization+")

Appendix 6. Web of Science Conference Proceedings search strategy