Abstract

A new hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) sensor is fabricated based on a multiwalled carbon nanotube-modified glassy carbon electrode (MWCNT-GCE) and reactive blue 19 (RB). The charge transfer coefficient, α, and the charge transfer rate constant, ks, of RB adsorbed on MWCNT-GCE were calculated and found to be 0.44 ± 0.01 Hz and 1.9 ± 0.05 Hz, respectively. The catalysis of the electroreduction of H2O2 by RB-MWCNT-GCE is described. The RB-MWCNT-GCE shows a dramatic increase in the peak current and a decrease in the over-voltage of H2O2 electroreduction in comparison with that seen at an RB modified GCE, MWCNT modified GCE, and activated GCE. The kinetic parameters such as α and the heterogeneous rate constant, k′, for the reduction of H2O2 at RB-MWCNT-GCE surface were determined using cyclic voltammetry. The detection limit of 0.27μM and three linear calibration ranges were obtained for H2O2 determination at the RB-MWCNT-GCE surface using an amperometry method. In addition, using the newly developed sensor, H2O2 was determined in real samples with satisfactory results.

Keywords: amperometry, electroreduction, hydrogen peroxide, reactive blue 19

1. Introduction

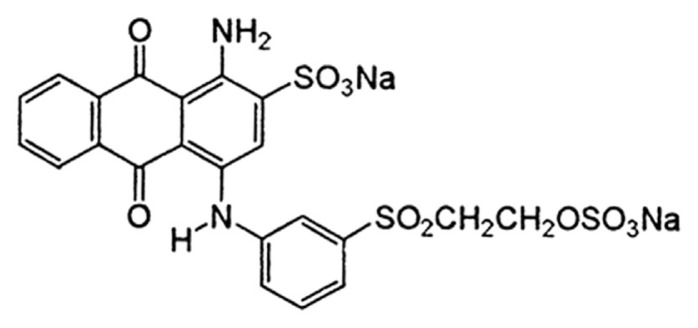

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is an essential mediator used in many fields of practice such as food, pharmaceutical, clinical, diagnostic, environmental protection, and in industries [1]. Indeed, H2O2 has wide applications in industrial processes as a universal oxidant and is a very important intermediate agent in environmental and biological reactions. It has also emerged as an important by-product of enzymatic reactions in biosensing processes, because it is released during the oxidation of substrates in the presence of oxygen [2,3]. Monitoring H2O2 with a reliable, rapid, and economical method is of great significance for numerous processes. The determination of H2O2 has been an important project over the past century. This is still something to accomplish, especially with the recent realizations about the existence of H2O2 in environmental samples. Various techniques including fluorimetry [4], titrimetry [5], chemiluminescence [6], spectrophotometry [7], photometry [8], and electrochemistry [9–11] have been developed for this purpose. Among these techniques, electrochemistry based on simple and low-cost electrodes has been extensively used to determine H2O2 [12]. It has been a preferred technique due to its quick response, low cost, simple instrumentation, high sensitivity, and possibility of miniaturization [13]. A number of enzyme electrodes reported for H2O2 determination are used due to their simplicity, high sensitivity, and selectivity [14]. Although, many enzymatic H2O2 assays possess good sensitivity and selectivity, native enzymes gradually lose their catalytic activity after repeated measurements and they are comparatively expensive. Therefore, the development of enzyme-free H2O2 sensors with a low detection limit and a wide responding range is preferred. However, the direct electrochemistry of H2O2 requires a higher over-potential and slow electrode kinetics on many electrode materials. Electrodes modified with different electroactive materials have the ability to detect H2O2 at low potentials. In recent years, various kinds of electrochemical sensors based on detection of different compounds in the food industry have been developed [15–18]. The study of electrochemical biosensors has been in progress to improve the speed, selectivity, sensitivity, and cost of producing chemical compounds. Immobilization of mediators in charge of electron transfer to electrode surfaces is a key step for the design, fabrication, and performance of sensors and biosensors [19]. Quinones are excellent electron mediators that efficiently reduce the working potentials and eliminate the effects of various electroactive substances in real samples; they have been successfully used in numerous biosensors to detect H2O2 [20,21]. Reactive blue 19 (RB) is a derivative of quinone (see its structure in Scheme 1). Owing to the good reactivity of quinone derivative mediators, it seems that the use of RB as a modifier could be important to yield some new information about the catalyzation of slow reactions. In this work, for the first time, RB is introduced as a catalytic compound for electroreduction of H2O2, then its electrochemical behavior and kinetic parameters are investigated. Cyclic voltammetry and amperometry were used to investigate the electrochemical properties and electrocatalytic activity of the modified electrode for determination of H2O2.

Scheme 1.

Structure of reactive blue 19.

2. Methods

2.1. Reagents and apparatus

H2O2, dimethyl formamide, and the other chemicals used to produce the buffer solution were obtained from Merck Company (Darmstadt, Germany) and used as received. RB was obtained from Sigma–Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs; with a diameter of 10–20 nm, length of 5–20 μm, and purity of 95%) were purchased from NanoLab Inc. (Waltham, MA, USA). All chemical reagents were of analytical grade. Phosphate buffer solutions (0.1M) were prepared with H3PO4, the pH was adjusted with 2.0M NaOH. All solutions were prepared with doubly distilled water.

Electrochemical experiments were carried out with an Autolab modular electrochemical system (ECO Chemie, Utrecht, The Netherlands) equipped with a PGSTA 30 module and driven by GPES 4.9 software, in conjunction with a three-electrode cell. The cell used was equipped with an RB-MWCNT-modified glassy carbon electrode (GCE) as a working electrode, a platinum electrode (Azar Electrode Co, Tabriz, Iran) as an auxiliary electrode, and a saturated calomel electrode as a reference electrode. All potentials in the text are quoted versus this reference electrode. The pH was measured with a pH/mV meter model 827 (Metrohm, Riverview, FL, USA).

2.2. Preparation of modified electrodes

The procedure of fabricating various modified electrodes was as follows. Prior to modification, a bare GCE was polished successively with 0.05 μm Al2O3 slurry on a polishing cloth and then rinsed with doubly distilled water. To be electrochemically activated, the cleaned electrode was immersed in a 0.1M sodium bicarbonate solution and activated by a continuous potential cycling from −1.45 to 1.7 V at a sweep rate of 100 mV/s. To prepare a RB modified GCE (RB-GCE) the activated GCE (AGCE) was rinsed and placed in a 0.10mM solution of RB in a 0.1M phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). It was modified by eight cycles of potential sweep between −0.4 and 0.5 V at 20 mV/s. To fabricate MWCNT-GCE, 3 μL of dimethyl formamide-MWCNT solution (1 mg/mL) was placed directly onto the AGCE surface and dried at room temperature for 30 minutes to form a MWCNT film at the GCE surface. An RB-MWCNT-GCE was prepared by immersing the MWCNT-GCE in a 0.10mM solution of RB in a 0.1M phosphate buffer (pH 7.0; Scheme 2). It was modified using the same procedure as for RB-GCE.

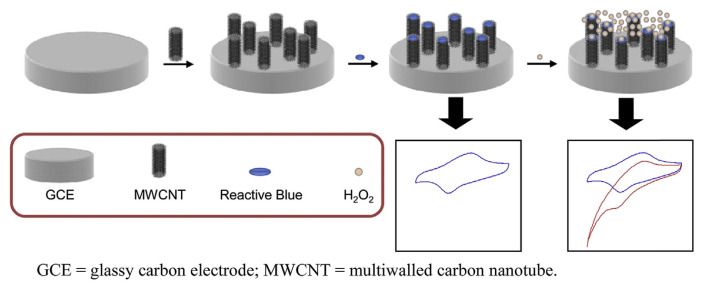

Scheme 2.

Schematic diagram for the sensor fabrication and determination of H2O2. GCE = glassy carbon electrode; MWCNT = multiwalled carbon nanotube.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Electrochemical behavior of RB-MWCNT-GCE

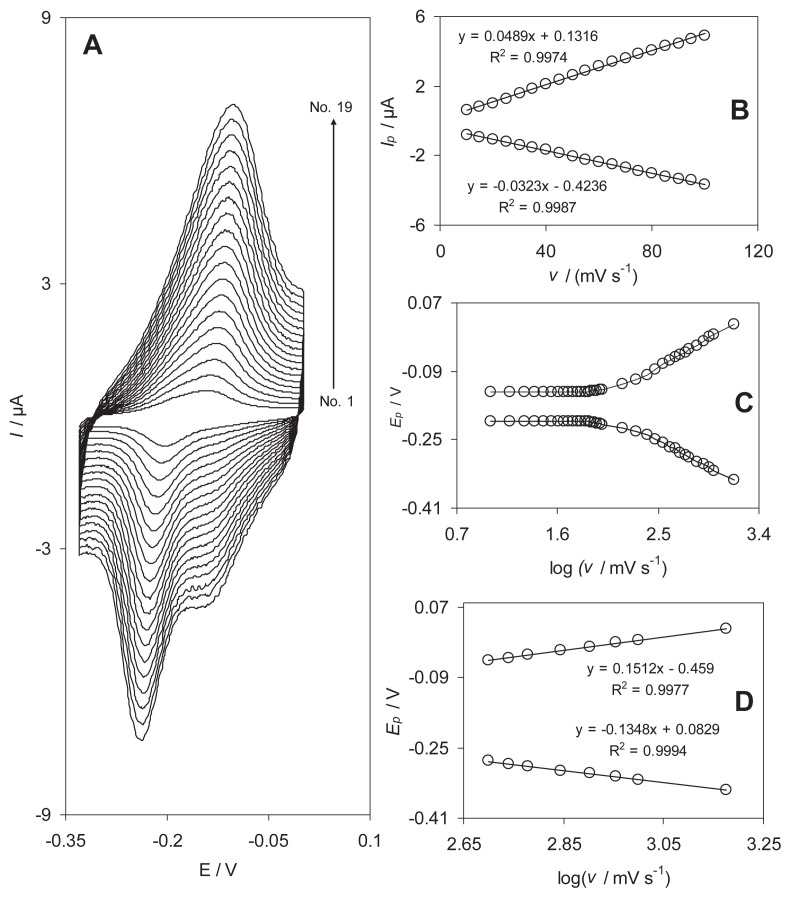

In recent years, the mechanism of electrodeposition of o- or p-hydroquinone derivatives, as modifiers, on the surface of an activated GCE has been a matter for discussion [22–25]. Fig. 1 shows the cyclic voltammograms of the RB-MWCNT-GCE in a 0.1M phosphate buffer solution (pH 7.0) at various potential scan rates. The plots of the anodic and cathodic peak currents versus the scan rate exhibit a linear relation (Fig. 1, inset B) as predicted theoretically for a surface-immobilized redox couple. This indicates the limitation arising from charge transfer kinetics. In other words, this is the range in which the reaction appears as quasir-eversible [26].

Fig. 1.

(A) Cyclic voltammograms of the reactive blue 19 multiwalled carbon nanotube-modified glassy carbon electrode in 0.1M phosphate buffer solution (pH 7.0) at different scan rates. The numbers 1–19 correspond to 15 mV/s, 20 mV/s, 25 mV/s, 30 mV/s, 35 mV/s, 40 mV/s, 45 mV/s, 50 mV/s, 55 mV/s, 60 mV/s, 65 mV/s, 70 mV/s, 75 mV/s, 80 mV/s, 85 mV/s, 90 mV/s, 95 mV/s, and 100 mV/s, respectively. (B) Plots of anodic and cathodic peak currents vs. the scan rate. (C) Variation of the peak potentials vs. the logarithm of the scan rate. (D) Magnification of the plot inset B for high scan rates.

When the potential was scanned between −330 and 0 mV, a surface-immobilized redox couple with a conditional formal potential, E0′, of −173 mV was observed. In addition, E0′ was almost independent of any potential scan rate for sweep rates ranging from 10 mV/s to 100 mV/s, suggesting facile charge transfer kinetics over this range of sweep rates. According to the method described by Laviron [27], the charge transfer coefficient, α, and the apparent heterogeneous charge transfer rate constant, ks, for the electron transfer between an MWCNT-GCE and a surface confined redox couple of RB can be evaluated in cyclic voltammetry by the variation of the anodic and cathodic peak potentials with the logarithm of scan rates.

For high scan rates, this theory predicts a linear dependence of Ep upon log ν, which can be used to extract the kinetic parameters of α and ks from the slope and intercept of such plots respectively. The results indicate that the values of the peak potentials were proportional to the logarithms of scan rates higher than 500 mV/s (Fig. 1C). Using these plots at pH 7.0, the value of α = 0.44 ± 0.01 was obtained. From the values of ΔEp corresponding to different sweep rates, an average value of ks was found to be 1.9 ± 0.05 Hz. This value of ks is comparable to those reported for other modifiers [21,24,27,28]. Since the electron transfer rate constant for the RB is about 1.9 Hz, it can be used as an excellent electron transfer mediator for electrocatalytic processes.

The effects of different experimental variables in the immobilization of RB were investigated to optimize the testing performance. In other words, the effects of the MWCNT amounts, the modifier solution pH, its concentration, the potential scan rate, and the number of potential recyclings were examined on the performance of modified electrode, and the anodic surface coverage was used as a measure of the surface deposited RB. The surface coverage (Γ) of the modified electrode was determined from the following equation, Γ = Q/nFA, where Q is the charge obtained by integrating the anodic or cathodic peak under the background correction and other symbols have their usual meanings, assuming an n value of 2. Table 1 illustrates the effect of different experimental conditions involved in the fabrication of RB-MWCNT-GCE. However, assuming that no interaction can exist between the variables, the one-at-a-time procedure [29] was used for optimization. The results in Table 1 show that the best surface coverage was obtained when the modification was carried out in a 1.0 mM RB solution with pH 7.0 (0.1M phosphate buffer) and the potential scan rate, was 20 mV/s.

Table 1.

Variations in anodic peak surface coverage, Γ, as a function of reactive blue 19 (RB) modified glassy carbon electrode multiwalled carbon nanotube (MWCNT) amounts, RB solution pH, RB solution concentration, [RB], potential scan rates, v, and number of cycles of potential scans, number of cycles, during the modification step. In all case the scan rate was 20 mV/s and the surface coverage is in 10−11 mol/cm.

| MWCNT amount (mg/cm3) | Γ | pH | Γ | [RB] (mM) | Γ | v (mV/s) | Γ | No. of cycles | Γ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.2 | 6.8 | 3 | 8.5 | 0.2 | 2.1 | 10 | 12.9 | 2 | 13.3 |

| 0.4 | 8.2 | 4 | 9.6 | 0.4 | 6.4 | 15 | 13.4 | 4 | 14.5 |

| 0.6 | 9.5 | 5 | 10.2 | 0.6 | 10.7 | 20 | 15.5 | 6 | 15.2 |

| 0.8 | 10.6 | 6 | 11.1 | 0.8 | 12.6 | 30 | 10.7 | 8 | 16.1 |

| 1.0 | 11.4 | 7 | 12.5 | 1.0 | 14.1 | 40 | 9.6 | 10 | 15.8 |

| 1.2 | 11.4 | 8 | 9.8 | 1.2 | 13.9 | 50 | 6.2 | 12 | 15.5 |

| 1.4 | 11.2 | 9 | 6.9 | 1.4 | 14.0 | 60 | 4.9 | 14 | 15.7 |

Moreover, the intraday repeatability of RB-MWCNT-GCE was tested by 10 replicate measurements in the buffer solution (pH = 7). The decrease of current signal was about 5%. Also, the long-term stability of RB-MWCNT-GCE was measured for 3 days. When cyclic voltammograms were recorded after the modified electrode was stored in at room temperature, only a 7% decrease was observed in the current response of the modified electrode. The initial decay of the current response of the voltammograms observed in both cases might be due to the release of the modifiers that are weakly bonded to MWCNT deposited on the electrode surface and can be separated somewhat easily.

3.2. Electrocatalytic reduction of H2O2 at RB-MWCNT-GCE

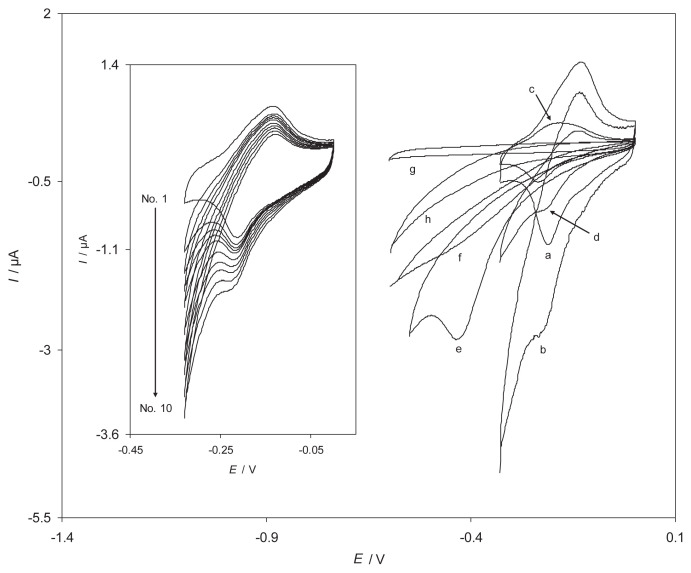

To test the electrocatalytic activity of the produced RB-MWCNT-GCE toward H2O2 reduction, cyclic voltammetric responses were obtained in a phosphate buffer solution at pH 7 in the absence and presence of H2O2 (Fig. 2). Fig. 2 indicates the cyclic voltammograms of different electrodes in a 0.1M phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) solution in the absence (a, c, g) and presence (b, d, e, f, h) of 0.40 mM H2O2. Curves a and b of Fig. 2 show the cyclic voltammograms of RB-MWCNT-GCE in the absence (a) and the presence (b) of 0.4mM of H2O2. As expected for electrocatalytic reduction, there was an increase in the cathodic peak current of RB-MWCNT-GCEred/RB-MWCNT-GCEox redox couple at the potential of −215 mV in the presence of H2O2, whereas the oxidation peak current virtually disappeared. This reflects the efficiency of the catalytic reaction. What occurred is basically because H2O2 in solution diffuses onto the electrode surface and oxidizes RB-MWCNT-GCEred into RB-MWCNT-GCEox. This process increases the cathodic peak current, while the anodic peak current is less in the absence of H2O2. Under the same experimental conditions, the cyclic voltammograms of RB-GCE were recorded in the absence (Fig. 2, curve c) and the presence of 0.40mM of H2O2 (Fig. 2, curve d). Table 2 shows the electrochemical characteristics of H2O2 reduction at various electrode surfaces. The results point to the best electrocatalytic effect for H2O2 reduction observed at RB-MWCNT-GCE. As can be seen in the case of the reduction responses of H2O2 at RB-GCE and RB-MWCNT-GCE, there is a dramatic enhancement in the cathodic peak current at RB-MWCNT-GCE as compared to the value obtained at RB-GCE. Similarly, the peak potential of H2O2 reduction at RB-MWCNT-GCE (Fig. 2, curve b) is less negative compared with that at MWCNT–GCE (Fig. 2, curve e). Also, there is no peak potential observed for H2O2 at AGCE and Reactive Blue modified Glassy Carbon Electrode (RB-GCE) (Fig. 2, curve f, h). The above results clearly show that a combination of MWCNT and RB definitely improves the characteristics of H2O2 reduction. The inset of Fig. 2 shows the dependence of the voltammetric response of RB-MWCNT-GCE on H2O2 concentration. As can be seen, with the addition of H2O2, there was an increase in the cathodic current.

Fig. 2.

Cyclic voltammograms of different electrodes in a 0.1M phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) solution in the absence (a, c, g) and presence (b, d, e, f, h) of 0.40mM H2O2: (a, b) reactive blue 19 multiwalled carbon nanotube-modified glassy carbon electrode (RB-MWCNT-GCE), (c, d) RB-GCE, (e) MWCNT-GCE, (f) acquired GCE and (g, h) BGCE. Inset shows the dependence of cyclic voltammetric response at a RB-MWCNT-GCE on H2O2 concentration in 0.1M phosphate buffer (pH 7). The numbers of 1–10 correspond to 0.0–473.7μM H2O2. In all cases the scan rate was 20 mV/s.

Table 2.

Comparison of electrocatalytic reduction of H2O2 (0.40mM) on various electrode surfaces at pH 7.0.

| Name of electrode | Reduction potential (mV) | Reduction current (μA) |

|---|---|---|

| MWCNT-GCE | −431 | −1.353 |

| RB-GCE | −221 | −0.397 |

| RB-MWCNT-GCE | −215 | −1.73 |

MWCNT-GCE = multiwalled carbon nanotube-modified glassy carbon electrode; RB–GCE = reactive blue modified glassy carbon electrode; RB-MWCNT-GCE = reactive blue multi–walled carbon nanotube-modified glassy carbon electrode.

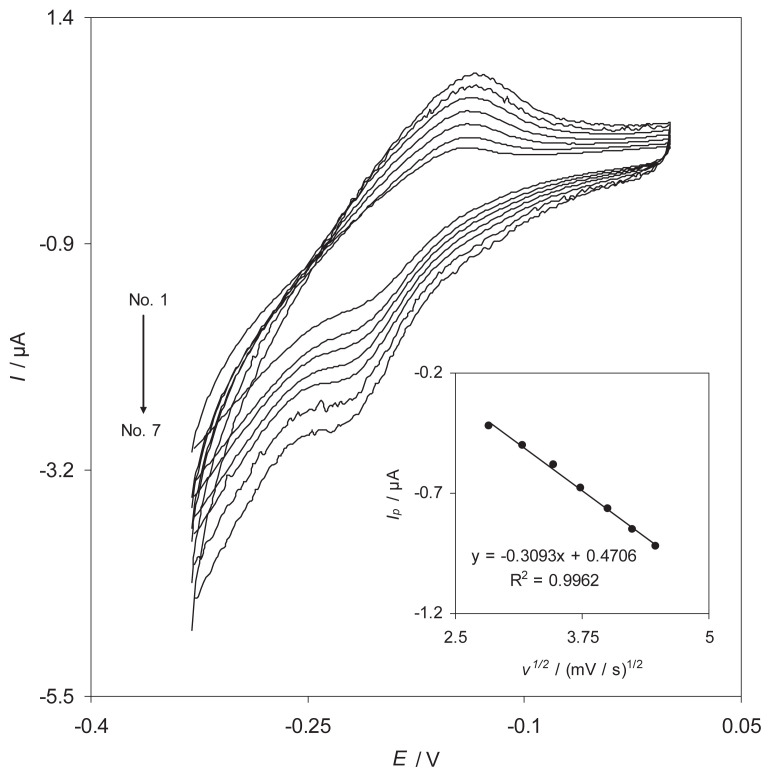

The cyclic voltammograms of a 0.40mM H2O2 solution at different sweep rates are shown in Fig. 3. The inset of Fig. 3 shows that the plot of the catalytic peak current versus the square root of the sweep rate is linear, suggesting that the reaction is diffusion limited. This is an ideal result for quantitative applications [25]. Also, the number of electrons, n, in the overall reduction reaction of H2O2 can be obtained from the plot of slope of IP versus v1/2 (inset of Fig. 3). According to the following equation for a totally irreversible diffusion controlled process:

Fig. 3.

Cyclic voltamograms of reactive blue 19 multiwalled carbon nanotube-modified glassy carbon electrode in 0.1M phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 0.40mM H2O2 at different scan rates. The numbers of 1–7 correspond to scan rates of 8 mV/s, 10 mV/s, 12 mV/s, 14 mV/s, 16 mV/s, 18 mV/s, and 20 mV/s. Inset: variation of the electrocatalytic peak current (Ip) versus the square root of sweep rate.

| (1) |

and considering (1–α)nα = 0.7 (see below), D = 2.34 × 10−6 cm2/s, Cb = 4 × 10−7 mol/cm3, and A = 0.0314 cm2, it is estimated that the total number of electrons involved in the reduction of H2O2 is n = 2.02 ~ 2. Similar values were also previously reported for the electroreduction of H2O2 [30–32].

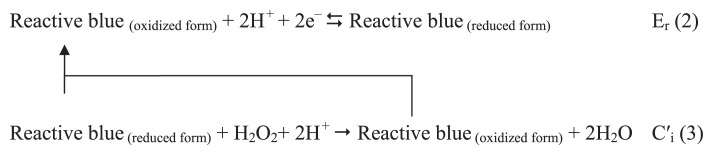

The electrocatalytic reduction of H2O2 at the modified electrode surface can be explained according to an ErCi catalytic (ErC′i) mechanism. It is shown in the following equations [25]:

|

As can be seen, H2O2 reduces by the reduced form of RB adsorbed at the MWCNT surface, RB-MWCNT-GCE (reduced form). The symbols Er and Ci imply reversible electrochemical and irreversible catalytic chemical reactions. For an ErC′i mechanism, Andrieux and Saveant [33] developed a theoretical model and derived the following equation for the relationship between the electrocatalytic peak current and the concentration of the substrate for a case of a slow scan rate, υ, and a large catalytic rate constant, k′:

| (4) |

where D and Cb are the diffusion coefficient (2.34 × 10−6 cm2/s is obtained by chronoamperometry as below) and the bulk concentration of H2O2. Low values of k′ result in coefficient values lower than 0.496 [33]. For low scan rates (8–20 mV/s), we found the value of this coefficient to be 0.3 for the modified electrode based on the slope of the plot in the inset of Fig. 3. An average value of k′= 4.6 (± 0.1) ×10−4 cm/s was calculated by such a working curve.

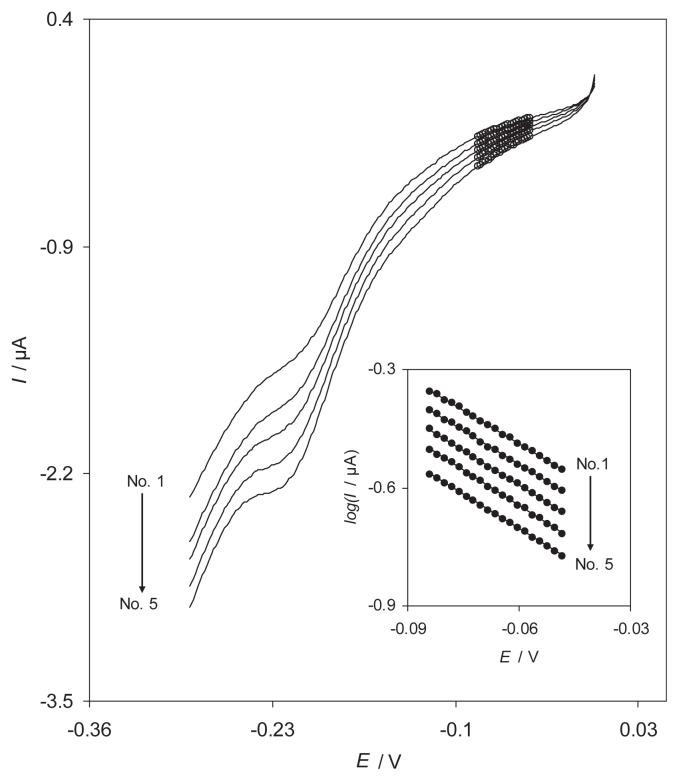

In order to obtain information about the rate-determining step, the linear sweep voltammograms of 0.40mM H2O2 were obtained at different sweep rates (Fig. 4). The inset of Fig. 4 shows the Tafel plots drawn from the data of the rising part of the current voltage curves recorded at various scan rates. This part of the voltammogram, known as Tafel region, is affected by the electron transfer kinetics between H2O2 and the surface-confined RB-MWCNT-GCE. The results of polarization studies for electroreduction of H2O2 at the modified electrode show that the average of Tafel slope of different plots agree well with the involvement of one-electron transfer process, assuming an average charge transfer coefficient of, αave = 0.3 ± 0.01. Also, the exchange current density, j0, is accessible from the intercept of the Tafel plots and the geometric area. The average valve obtained for the exchange current density of H2O2 at RB-MWCNT-GCE was found to be 3.64 ± 0.1 μA/cm2.

Fig. 4.

Linear sweep voltammogram of reactive blue 19 multiwalled carbon nanotube-modified glassy carbon electrode in 0.lM phosphate buffer solution (pH 7.0) containing 0.40 mM H2O2 at different scan rates (8–16 mV/s). Inset shows the Tafel plots derived from the linear sweep voltammograms.

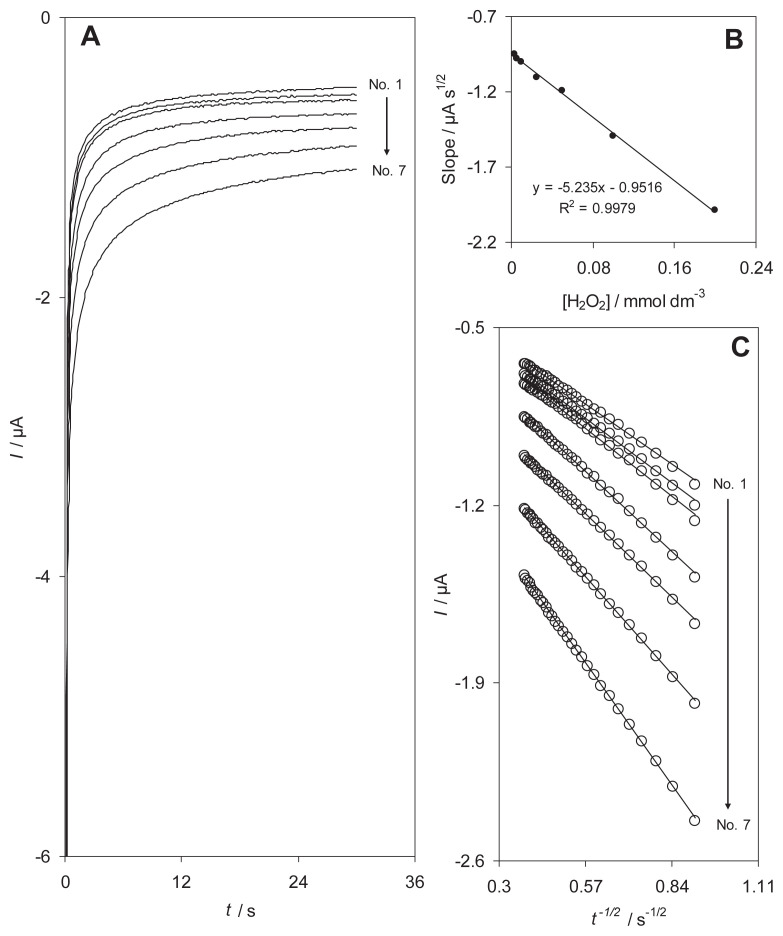

The electrocatalytic reduction of H2O2 by RB-MWCNT-GCE was also studied by chronoamperometry. The chronoamperograms obtained at the potential step of −300 mV are shown in Fig. 5. Inset A of Fig. 5 shows the experimental plots I versus t−1/2 with the best fits for different concentrations of H2O2. The slopes of the resulting straight lines were then plotted versus the H2O2 concentration (Fig. 5, inset B), from whose slope and using the Cottrell equation [25] a diffusion coefficient was calculated: 2.34 × 10−6 cm2/s.

Fig. 5.

(A) Chronoamperometric responses of reactive blue 19 multiwalled carbon nanotube-modified glassy carbon electrode in a 0.1M phosphate buffer solution (pH 7.0) at a potential step −300 mV for different concentrations of H2O2. The numbers of 1–7 correspond to 0.003–0.20mM H2O2. Insets: (B) plots of I versus t−1/2 obtained from chronoamperograms. (C) plot of the slope of straight lines against the H2O2 concentrations.

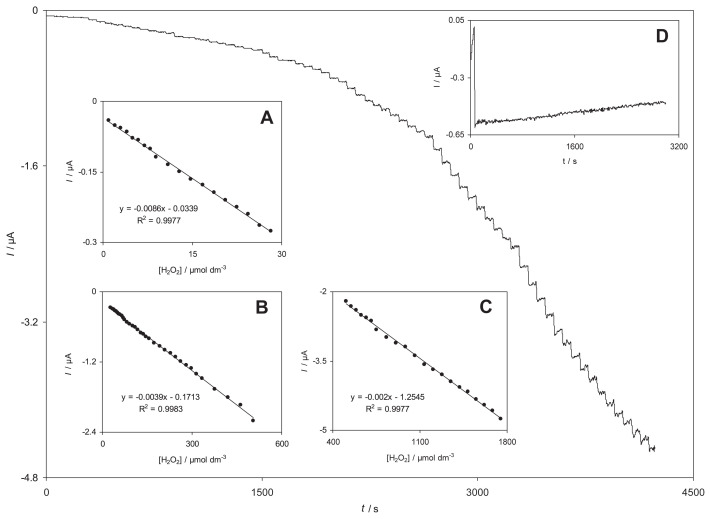

3.3. Amperometric determination of H2O2

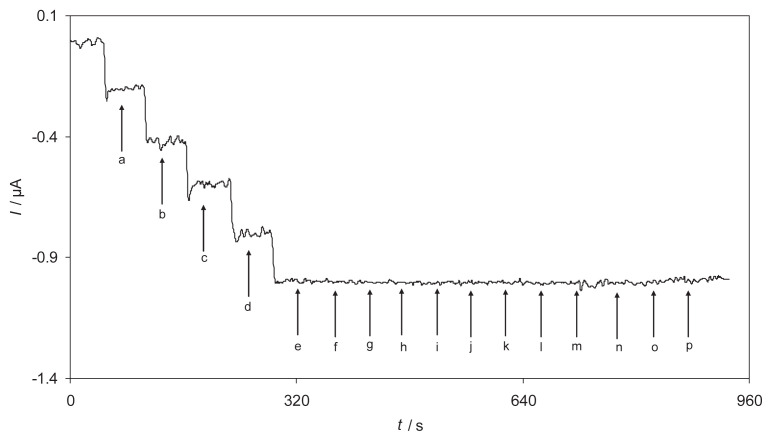

Amperometry was used to determine the linear ranges and the detection limit of H2O2 at RB-MWCNT-GCE. The use of amperometry was based on the fact that it has a much higher current sensitivity than cyclic voltammetry. Fig. 6 shows the amperograms obtained for a rotating RB-MWCNT-GCE (rotation speed 2000 rpm), under conditions where the potential was held at −300 mV in a 0.1M phosphate buffer solution (pH 7.0) containing different concentrations (0.99–1.8mM) of H2O2.

Fig. 6.

Amperometric responses at a rotating reactive blue 19 multiwalled carbon nanotube-modified glassy carbon electrode (rotation speed 2000 rpm) held at −300 mV in different concentrations of H2O2. Insets A, B, and C indicate variations of the amperometric currents vs. H2O2 concentrations in the ranges of (A) 1.99–28.2μM, (B) 282–504μM, and (C) 0.504–1.75μM. Inset D shows the stability of the response of the reactive blue 19 multiwalled carbon nanotube-modified glassy carbon electrode to 100.0μM H2O2 during 2900 seconds.

The insets shown in Fig. 6 demonstrate the linear relationship of the electrocatalytic current vs. H2O2 concentration in the three linear ranges: (A) 0.99–28μM; (B) 28–510μM; and (C) 0.51–1.8mM. The decrease of sensitivity (slope) in the second and third linear range (higher analyte concentrations) is likely to be due to electrode surface pollution.

According to the method mentioned in reference [34], the lower detection limit, Cm, was found to be 0.27μM using the equation Cm = 3sbl/m, where sbl is the standard deviation of the blank response which is obtained from 14 replicate measurements of the blank solution (0.00077 μA) and m is the slope of the calibration plot (0.0086 μA/μM). Moreover, the limit of quantitation was calculated to be 0.9μM by limit of quantitation = 10sbl/m [34]. The average amperometric peak current and the precision estimated in terms of the coefficient of variation for repeated measurements (n = 10) of 15.0μM H2O2 at RB-MWCNT-GCE were 0.167 ± 0.005 μA and 3.02% respectively. It indicated that the sensor possessed good reproducibility. Also the stability of RB-MWCNT-GCE under working conditions was investigated in the presence of 100.0μM of H2O2. Inset D of Fig. 6 indicates the response stability of RB-MWCNT-GCE to 100.0μM of H2O2 solution during 2900 seconds. As shown, the amperometric current of H2O2 reduction remained almost constant during the experiment. In Table 3, some of the response characteristics obtained for H2O2 in this study are compared to those previously reported by others [3,11,13,19,30,32]. As can be seen, the responses of the proposed modified electrode are superior in some cases as compared to the previously reported modified electrodes.

Table 3.

Comparison of analytical parameters of several modified electrodes for H2O2 determination.

| Modifier | Method | Linear range (μM) | Detection limit (μM) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mn-complex-SWCNTs | Amperometry | 1–1500 | 0.2 | [3] |

| [PFeW11O39]4− polyoxoanion | Amperometry | 10–200 | 7.4 | [11] |

| AgNPs/PMES | Amperometry | 0.6–540 | 0.18 | [13] |

| Nanonickel oxide/thionine | Amperometry | 5–20000 | 1.67 | [19] |

| Nanonickel oxide/celestine blue | Amperometry | 1–10000 | 0.37 | [19] |

| Nano-TiO2/DNA/thionin | Amperometry | 50–22300 | 50 | [30] |

| n-octylpyridinum Hexafluorophosphate | Amperometry | 20–800 | 12 | [32] |

| RB-MWCNT-GCE | Amperometry | 0.99–2.8 × 10, 2.8 × 10–5.1 × 102 5.1 × 102–1.8 × 103 | 0.27 | This work |

AgNPs/PMES = silver nanoparticles/poly(2–(N–morpholine) ethane sulfonic acid); ERGO-Ag nanocomposite = electrochemically reduced graphene oxide (ERGO)-silver nanoparticle hybrid film; Mn–complex–SWCNTs = single wall carbon nanotubes and phenazine derivative of Mn–complex; PB/Pd–Al = aluminum electrode plated by thin layer metallic palladium and modified by Prussian blue; RB-MWCNT-GCE = reactive blue multiwalled carbon nanotubes modified glassy carbon electrode.

3.4. Interference study

An important problem in determining H2O2 is the effect of potential interfering ions. A survey on the influence of various substances as potential interfering compounds on the H2O2 determination under optimum conditions at the RB-MWCNT-GCE surface was done. Fig. 7 shows the amperometric response of modified electrode during addition of 20–220μM of H2O2 and different interferences to buffer solution (pH 7). As illustrated, nearly all compounds such as ascorbic acid, uric acid, glucose, dopamine, oxalic acid, NaNO3, Mg(NO3)2, KCl, KI, NaNO2, and Na2SO4 do not interfere when present in 1.0 mM concentration. The sensor response toward H2O2 before and after interference injection is the same. The results indicate that H2O2 recovery was almost quantitative in the presence of an excess amount of possible interfering species at this sensor.

Fig. 7.

Amperometric responses at a rotating reactive blue 19 multiwalled carbon nanotube-modified glassy carbon electrode (rotation speed 2000 rpm) held at −300 mV in buffer solution (pH = 7) for successive addition of H2O2 (a–e, 20–220μM) and 1mM of (f) ascorbic acid, (g) uric acid, (h) glucose, (i) dopamine, (j) oxalic acid, (k) NaNO3, (l) Mg(NO3)2, (m) KCl, (n) KI, (○) NaNO2 and (p) Na2SO4.

3.5. Analysis of real samples

Sometimes, for the aseptic packaging of fruit juices, H2O2 is used as a chemical agent for sterilization. However, the H2O2 residues in higher concentration are skin irritants and may affect the human health. Therefore, determination of H2O2 in fruit juices is important. The maximum level of H2O2 residual allowed in the aseptic packaging in accordance with US Food and Drug Administration (21 CFR 178.1005) is 0.5 ppm (14.7μM). Since the lower linear range of the proposed sensor is 0.99–28.0μM, this sensor can be applied for determination of H2O2 in aseptic packaging.

From the results, it is apparent that RB-MWCNT-GCE possesses a high sensitivity and a good detecting capability to determine H2O2 in real samples. In order to test its practical application, the modified electrode was used to determine H2O2 in three fruit juice samples. As the electrochemical techniques are able to determine H2O2 without pretreatment, therefore the fruit juice samples were directly inserted to the experimental cell. To do the experiment, 2 μL of a fruit juice sample were diluted down to 10 μL with a 0.1 M phosphate buffer solution (pH 7.0). Then, known amounts of H2O2 were added, and their recoveries were determined using amperometric measurements. The results in Table 4 indicate that the Percentage of relative standard deviation (RSD%) and the recovery rates of the spiked samples are acceptable. Thus, RB-MWCNT-GCE can be efficiently used for H2O2 determination in different fruit juice samples. It is concluded that the matrix of fruit juice samples does not interfere in determination of H2O2 at the proposed sensor.

Table 4.

Determination and recovery of H2O2 concentration in three fruit juice samples using reactive blue multiwalled carbon nanotube-modified glassy carbon electrode.

| Samples | Added (μM) | Founda (μM) | RSD (%) | Recovery % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apple juice | – | Not detected | – | – |

| 10.0 | 10.3 | 2.7 | 103 | |

| 20.0 | 19.5 | 2.2 | 97.5 | |

| Orange juice | – | Not detected | – | – |

| 8.0 | 8.2 | 2.5 | 102.5 | |

| 16.0 | 15.7 | 2.9 | 98.1 | |

| Banana juice | – | Not detected | – | – |

| 12.0 | 12.4 | 2.8 | 103.3 | |

| 24.0 | 23.5 | 2.1 | 97.9 |

RSD = Relative Standard Deviation.

Three replicate measurements were made on the same samples. Detection limit = 0.27μM.

3.6. Conclusions

This paper demonstrates the construction of an RB-MWCNT-GCE and its application in determination of H2O2. The results of the study show that RB can be immobilized easily at the surface of MWCNT-modified GCE. Kinetic parameters such as the catalytic rate constant, ks, transfer coefficient, α, the number of electrons involved in the rate determining step, nα, and the overall number of electrons involved in the catalytic reduction of H2O2 at the modified electrode surface have also been determined using cyclic voltammetry. The diffusion coefficient of H2O2 has been found to be 2.34 × 10−6 cm2/s for experimental conditions using chronoamperometric results. RB–MWCNT–GCE exhibits three wide linear ranges of 0.99–28μM, 28–510μM, and 0.51–1.8mM for H2O2 determination by amperometry. The lower detection limit of H2O2 at the modified electrode is 0.27μM. Also, amperometry can be used as an analytical method for H2O2 determination in real samples.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Farah AM, Shooto ND, Thema FT, Modise JS, Dikio ED. Fabrication of Prussian blue/multi-walled carbon nanotubes modified glassy carbon electrode for electrochemical detection of hydrogen peroxide. Int J Electrochem Sci. 2012;7:4302–13. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Salimi A, Mahdioun M, Noorbakhsh A, Abdolmaleki A, Ghavami RA. Novel non-enzymatic hydrogen peroxide sensor based on single walled carbon nanotubes–manganese complex modified glassy carbon electrode. Electrochim Acta. 2011;56:3387–94. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Song MJ, Hwang SW, Whang D. Amperometric hydrogen peroxide biosensor based on a modified gold electrode with silver nanowires. J Appl Electrochem. 2010;40:2099–105. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Taniai T, Sakuragawa A, Okutani T. Fluorometric determination of hydrogen peroxide in natural water samples by flow injection analysis with a reaction column of peroxidase immobilized onto chitosan beads. Anal Sci. 1999;15:1077–82. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hurdis EC, Romeyn H. Accuracy of determination of hydrogen peroxide by cerate oxidimetry. Anal Chem. 1954;26:320–5. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rocha FRP, Torralba ER, Reis BF, Rubio AM, Guardia MA. portable and low cost equipment for flow injection chemiluminescence measurements. Talanta. 2005;67:673–7. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2005.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Matos C, Coelho EO, De Souza CF, Guedes FA, Matos MA. Peroxidase immobilized on Amberlite IRA-743 resin for online spectrophotometric detection of hydrogen peroxide in rainwater. Talanta. 2006;69:1208–14. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2005.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kok GL, Holler TP, Lopez MB, Nachtrieb HA, Yuan M. Chemiluminescent method for determination of hydrogen peroxide in the ambient atmosphere. Environ Sci Technol. 1978;12:1072–6. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mashazi PN, Ozoemena KI, Nyokong T. Tetracarboxylic acid cobalt phthalocyanine SAM on gold: potential applications as amperometric sensor for H2O2 and fabrication of glucose biosensor. Electrochim Acta. 2006;52:177–86. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thenmozhi K, Narayanan SS. Electrochemical sensor for H2O2 based on thionin immobilized 3-aminopropyltrimethoxy silane derived sol–gel thin film electrode. Sens Actuators B. 2007;125:195–201. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hamidi H, Shams E, Yadollahi B, Kabiri Esfahani F. Fabrication of carbon paste electrode containing [PFeW11O39] 4− polyoxoanion supported on modified amorphous silica gel and its electrocatalytic activity for H2O2 reduction. Electrochim Acta. 2009;54:3495–500. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Majidi M, Pournaghi-Azar MH, Saadatirad A, Alipour E. Simple and rapid amperometric monitoring of hydrogen peroxide at hemoglobin-modified pencil lead electrode as a novel biosensor: application to the analysis of honey sample. Food Anal Methods. 2015;8:1067–77. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang K, Zhang N, Xu J, Wang H, Wang C, Shi H, et al. Silver nanoparticles/poly(2-(N-morpholine) ethane sulfonic acid) modified electrode for electrocatalytic sensing of hydrogen peroxide. J Appl Electrochem. 2011;41:1419–23. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kalantar-Dehnavi A, Rezaei-Zarchi S, Mazaheri Gh, Negahdary M, Malekzadeh R, Mazdapour M. Designing a H2O2 Biosensor by using of modified graphite electrode with nano-composite of nafion-nile blue-peroxidase enzyme. Eur J Exp Biol. 2012;2:672–82. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Saber-Tehrani M, Pourhabib A, Husain SW, Arvand M. A simple and efficient electrochemical sensor for nitrite determination in food samples based on Pt nanoparticles distributed poly(2-aminothiophenol) modified electrode. Food Anal Methods. 2013;6:1300–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chandran S, Lonappan LA, Thomas D, Jos T, Girish K, Kumar KG. Development of an electrochemical sensor for the determination of amaranth: a synthetic dye in soft drinks. Food Anal Methods. 2014;7:741–6. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rasheed Z, Vikraman AE, Thomas D, Jagan JS, Kumar KG. Carbon-nanotube-based sensor for the determination of butylated hydroxyanisole in food samples. Food Anal Methods. 2015;8:213–21. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Raoof JB, Teymoori N, Khalilzadeh MA. ZnO nanoparticle ionic liquids carbon paste electrode as a voltammetric sensor for determination of Sudan I in the presence of vitamin B6 in food samples. Food Anal Methods. 2015;8:885–92. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Noorbakhsh A, Salimi A. Amperometric detection of hydrogen peroxide at nano-nickel oxide/thionine and celestine blue nanocomposite-modified glassy carbon electrodes. Electrochim Acta. 2009;54:6312–21. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vianello F, Zennaro L, Rigo AA. Coulometric biosensor to determine hydrogen peroxide using a monomolecular layer of horseradish peroxidase immobilized on a glass surface. Biosens Bioelectron. 2007;22:2694–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen X, Chen Z, Zh J, Xu C, Yan W, Yao C. A novel H2O2 amperometric biosensor based on gold nanoparticles/self-doped polyaniline nanofibers. Bioelectrochemistry. 2011;82:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.bioelechem.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zare HR, Nasirizadeh N, Mazloum–Ardakani M. Electrochemical properties of a tetrabromo-p-benzoquinone modified carbon paste electrode. Application to the simultaneous determination of ascorbic acid, dopamine and uric acid. J Electroanl Chem. 2005;577:25–33. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nasirizadeh N, Shekari Z, Zare HR, Makarem S. Electrocatalytic determination of dopamine in the presence of uric acid using an indenedione derivative and multiwall carbon nanotubes spiked in carbon paste electrode. Mater Sci Eng C. 2013;33:1491–7. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2012.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nasirizadeh N, Shekari Z, Zare HR, Shishehbore MR, Fakhari AR, Ahmar H. Electrosynthesis of an imidazole derivative and its application as a bifunctional electrocatalyst for simultaneous determination of ascorbic acid, adrenaline, acetaminophen, and tryptophan at a multi-wall carbon nanotubes modified electrode surface. Biosen Bioelectron. 2013;41:608–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2012.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bard AJ, Falkner LR. Electrochemical methods: fundamentals and applications. NewYork: Wiley; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Laviron E. General expression of the linear potential sweep voltammogram in the case of diffusionless electrochemical systems. J Electroanal Chem. 1979;101:19–28. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zare HR, Nasirizadeh N, Chatraei F, Makarem S. Electrochemical behavior of an indenedione derivative electrodeposited on a renewable sol–gel derived carbon ceramic electrode modified with multi-wall carbon nanotubes: application for electrocatalytic determination of hydrazine. Electrochim Acta. 2009;54:2828–36. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zare HR, Shekari Z, Nasirizadeh N, Jafari AA. Fabrication, electrochemical characteristics and electrocatalytic activity of 4-((2-hydroxyphenylimino)methyl)benzene-1,2-diol electrodeposited on a carbon nanotube modified glassy carbon electrode as a hydrazine sensor. Catal Sci Technol. 2012;2:2492–501. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller JN, Miller JC. Statistics and chemometrics for analytical chemistry. 4th ed. London: Pearson Education Ltd; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lo PH, Kumar SA, Chen SM. Amperometric determination of H2O2 at nano-TiO2/DNA/thionin nanocomposite modified electrode. Colloids Surfaces B. 2008;66:266–73. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bai YH, Du Y, Xu JJ, Chen HY. Choline biosensors based on a bi-electrocatalytic property of MnO2 nanoparticles modified electrodes to H2O2. Electrochem Commun. 2007;9:2611–6. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Haghighi B, Hamidi H, Gorton L. Formation of a robust and stable film comprising ionic liquid and polyoxometalate on glassy carbon electrode modified with multiwalled carbon nanotubes: toward sensitive and fast detection of hydrogen peroxide and iodate. Electrochim Acta. 2010;55:4750–7. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Andrieux CP, Saveant JM. Heterogeneous (chemically modified electrodes, polymer electrodes) vs. homogeneous catalysis of electrochemical reactions. J Electroanal Chem. 1978;93:163–8. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Skoog DA, Holler FJ, Nieman TA. Principles of Instrumental Analysis. 5th ed. London: Saunders College Publishing; 1998. [Google Scholar]