Humanity faces unprecedented challenges of the current COVID-19 pandemic, persistent health crises, demographic shifts, conflict, and unsustainable environmental demands. At the 26th annual UN climate change conference (COP26), countries pledged to protect population and planetary health through sustainable leadership for climate resilient health systems.1 Although health co-benefits from climate change actions are well evidenced, including the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), in practice climate, sustainability, and health policies are disconnected, and equity considerations remain theoretical. Population ageing is a crucible where health, sustainability, and equity interact and where alignment of agendas is crucial.2

Acting on protective and risk factors across the lifecourse is known to optimise health at all lifestages and is associated with healthy ageing. Compelling evidence of age-specific dementia reduction reinforces a recent Lancet Commission's summary that together these risk and protective factors could delay or prevent up to 40% of dementias.3, 4 Each lifestage is influenced by fiscal measures, education and employment, environmental, social and commercial; promoting, or not, health as we age.5 Further, good indoor and environmental design, as well as connected communities, lead to successful ageing and more cohesive societies.

However, exposure to factors influencing health with age is hugely unequal globally, within and across communities, reinforcing social and structural inequalities.6 This disparity leads to lower life expectancy with poorer quality of life and health for those living with disadvantage. Examples abound, and worse outcomes due to poor air quality or high alcohol intake are concentrated in lower socioeconomic groups.7, 8 Education and relative wealth, as markers of inequity, have independent effects on healthy ageing trajectories, and cumulative disadvantage due to low education and poverty impacting health persistently across lifestages.9 Healthy ageing is an equity issue, and a social justice issue.

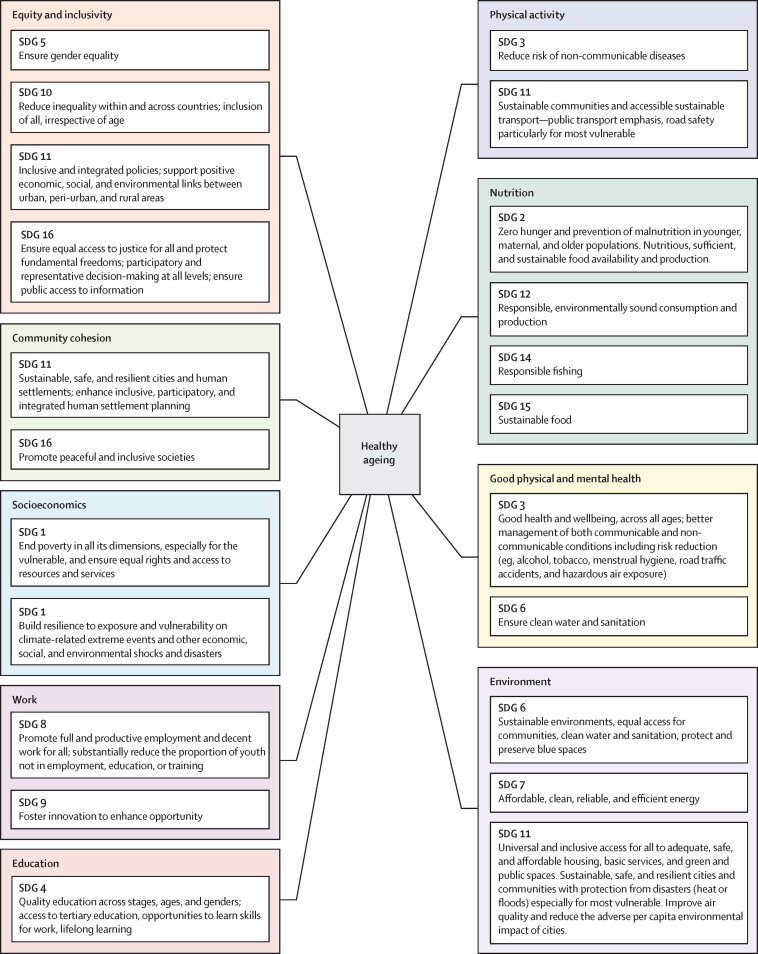

The SDGs are designed to achieve a better and more sustainable future for all.10 Explicit links between healthy ageing and SDGs have focused on SDG3: “to ensure healthy lives and promote wellbeing for all at all ages”. If ageing is to be sustainable, tangible efforts must be made well beyond this with action across the Goals. The figure provides a map of manifest, urgent, opportunities for effective cross lifecourse interdisciplinary approaches for sustainable and equitable healthy ageing.

Figure.

Sustainable development goals and targets mapped to factors that promote healthy ageing and brain health across the lifecourse

These opportunities are mutually reinforcing; adding and strengthening synergistically, offering solutions across elements that are fundamental to both. For example, the direct impacts of climate change on health will disproportionately affect older people, and SDG 11 highlights specific action to protect the most vulnerable from environmental disasters. Where the Agenda's commitment to inequality focuses on income inequality in SDG 10, healthy ageing agendas detail action on health inequalities. Unaddressed, the longer-term consequences of unmitigated environmental degradation will be on future generations' health at scale. Aligned and together, both agendas offer paths forward to address the consumptagenic systems that are harming the planet and driving poor health across the lifecourse.

The health sector has rightly been referred to as a sleeping giant on climate and sustainable action. The shape and ideologies of our health systems play a role in which an increasingly single-disease, biomedicalised approach to health is promoted, providing a compelling business narrative for major industrial players globally. Community action, active citizens, and engaged decision makers should align to scrutinise our current models of health and care to sustain health and life. SDG 12 explicitly voices the promotion of knowledge and skills to build sustainable development equitably and enable lifestyles in harmony with nature. Governments need to be held to account on their pledges if real change is to be achieved.

Healthy living and healthy ageing rely on a sustainable planet. Equally, healthier populations create healthier, sustainable worlds. The opportunity to integrate these agendas (and many others) offers tangible approaches not only to build healthier and fairer places and communities across ages, but to inspire a hope and optimism in the art of the possible—at a time when it could not be needed more.

AM is funded by a UK National Institute for Health and Care Research Doctoral Research Fellowship. All other authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2021. COP26 special report on climate change and health: the health argument for climate action. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mavrodaris A, Mattocks C, Brayne CE. Healthy ageing for a healthy planet: do sustainable solutions exist? Lancet Healthy Longev. 2021;2:e10–e11. doi: 10.1016/S2666-7568(20)30067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolters FJ, Chibnik LB, Waziry R, et al. Twenty-seven-year time trends in dementia incidence in Europe and the United States: the Alzheimer Cohorts Consortium. Neurology. 2020;95:e519–e531. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2020;396:413–446. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30367-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lafortune L, Martin S, Kelly S, et al. Behavioural risk factors in mid-life associated with successful ageing, disability, dementia and frailty in later life: a rapid systematic review. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Venkatapuram S, Ehni HJ, Saxena A. Equity and healthy ageing. Bull World Health Organ. 2017;95:791–792. doi: 10.2471/BLT.16.187609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowe B, Xie Y, Yan Y, Al-Aly Z. Burden of cause-specific mortality associated with PM2.5 air pollution in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.15834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sabia S, Guéguen A, Berr C, et al. High alcohol consumption in middle-aged adults is associated with poorer cognitive performance only in the low socio-economic group. Results from the GAZEL cohort study. Addiction106: 93–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Wu YT, Daskalopoulou C, Muniz Terrera G, et al. Education and wealth inequalities in healthy ageing in eight harmonised cohorts in the ATHLOS consortium: a population-based study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e386–e394. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30077-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.UN General Assembly Transforming our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. https://sdgs.un.org/#goal_section