Abstract

Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is a troublesome hygienic problem that afflicts the female population and is associated with extracellular matrix (ECM). Herein, we investigated the effects of microRNA (miR)-34a on ECM metabolism in fibroblasts of SUI via mediating nicotinamide phosphoribosyl transferase (Nampt/NAmPRTase) and hope to find novel insights in the treatment of SUI. Firstly, the anterior vaginal wall tissues of SUI patients and the female vaginal wall fibroblasts (FVWFs) of non-SUI subjects were collected and identified. Then, FVWFs were treated with 10 ng/mL of interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β) to establish SUI cell models. Subsequently, miR-34a and Nampt expressions in both types of cells were detected via RT-qPCR. It was found that miR-34a was poorly expressed, while Nampt was highly expressed in SUI. Subsequently, IL-1β-treated FVWFs were transfected with miR-34a-mimic and pcDNA3.1-Nampt, respectively. Thereafter, RT-qPCR and Western blot detected that miR-34a overexpression increased COL1A, ACAN, and TIMP-1; decreased MMP-2 and MMP-9; and elevated LC3 II/I ratio, Beclin-1 expression, and the autophagosome number in IL-1β-treated FVWFs, while Nampt upregulation reversed the above outcomes. Then, dual-luciferase reporter gene assay detected that Nampt is a downstream target of miR-34a. Together, miR-34a overexpression promoted autophagy, inhibited ECM degradation in IL-1β-treated FVWFs, and ameliorated SUI via suppressing Nampt.

Keywords: Stress urinary incontinence, Extracellular matrix metabolism, Autophagy, miR-34a, Nampt, Fibroblast

Introduction

Stress urinary incontinence (SUI), as the primary type of urinary incontinence, is defined as an uncontrolled leakage of urine caused by high pressure in the intra-abdomen, such as laughing or coughing (Capobianco et al. 2018). Women in pregnancy, delivery, or menopause are the susceptible group to SUI, and SUI adversely influences the life quality and mental state of the above groups, making them unhandy for work and even isolated from social contact (Sangsawang and Sangsawang 2013; Aoki et al. 2017; Wu et al. 2021). So far, the rehabilitation exercise of the pelvic floor is the most recommended method for SUI treatment, as it benefits muscle recovery and strengthening (Preda and Moreira 2019). Our study aimed to find viable biomarkers to improve the efficacy of SUI treatment and to the quality of life of SUI patients.

Extracellular matrix (ECM) is classified as a macromolecular network with a three-dimensional structure consisting of collagens, elastin, and other glycoproteins (Theocharis et al. 2016). ECM is a pivotal regulator of a broad range of the biological processes of eukaryotic cells, affecting cell survival, growth, and differentiation through signal transduction (Theocharis et al. 2016; Walma and Yamada 2020). The impairment of functional ECM in connective tissues of SUI patients has been recognized as a pivotal change in the pathophysiology of SUI (Huang et al. 2013). ECM maintains its functions through connective tissue-mediated metabolism, and the impairment or disturbance of ECM would weaken the supporting structures of the periurethral, resulting in uncontrolled leakage of urine (Huang et al. 2013). In this study, we further explored the potential interaction between ECM metabolism and SUI.

MicroRNAs (miRs), defined as a type of small and non-coding RNAs, can bind with 3′-untranslated region (UTRs) of mRNAs to restrict mRNA translation or induce mRNA degradation, thereby suppressing gene expression at the post-transcription level (Lu and Rothenberg 2018). Several differentially expressed miRs have been identified in the periurethral vaginal wall tissue of SUI patients (X. Liu et al. 2019). Previous studies showed that miR-29 can suppress elastin to mitigate pelvic floor dysfunction, and miR-93 participates in ECM remodeling in fibroblasts in SUI via regulating coagulation factor III (Jin et al. 2016; Wang et al. 2021). It is noteworthy that miR-34a is related to tubulointerstitial fibrosis, and the osteogenesis in necrosis induced by steroids in the femoral head (X. Jiang et al. 2021a, b; Xue et al. 2018). Furthermore, Zhang et al. reported that miR-34a is involved in cardiac fibroblast proliferation and ECM deposition (C. Zhang et al. 2018). However, no study has been done to explore the mechanism of miR-34a in SUI.

Autophagy has been described as an effective intracellular recycling system due to its degradation function that delivers certain cytoplasmic materials into the lysosome, playing an indispensable role in cellular maintenance and survival (Parzych and Klionsky 2014). A recent study illustrated that atorvastatin limits TNF-α-induced matrix degradation through activating autophagy (Chen et al. 2021), and the autophagy mediated by TGF-β in fibroblasts of the urethra is involved in traumatic urethral strictures (Feng et al. 2021). In this study, the specific roles of autophagy in SUI were explored.

As a regulator of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (Nampt/NAmPRTase) modulates cell aging and metabolism (Garten et al. 2015). Prior studies suggested that Nampt expression has a controlling effect on ECM degradation by modulating the activity of NLRP3 inflammasomes in nucleus pulposus cells (Y. Huang et al. 2020a, b) and affects autophagy in ischemia/reperfusion-induced damage (T. Li et al. 2020). Moreover, the study we previously conducted revealed that Nampt participates in ECM degradation in SUI through regulating autophagy (H. Zhang et al. 2022). Of note, miR-34a is known to target Nampt to play a crucial role in obesity- and aging-related diseases (Choi et al. 2013; Pi et al. 2021). However, whether miR-34a/Nampt functions in ECM degradation in SUI remains undiscovered.

In this present work, we sought to study the mechanism of the miR-34a/Nampt axis in ECM metabolism in fibroblasts of SUI, which may provide a promising theoretical direction for SUI treatment.

Materials and methods

Clinical specimens

From December 2018 to December 2020, we recruited 30 women diagnosed with SUI according to the suggestions of the International Continence Society (ICS) of Zhengzhou Central Hospital of Zhengzhou University (Haylen et al. 2010) and received (Tension-free vaginal tape) TVT operation for this study. The control groups consisted of 30 subjects who did not have SUI or pelvic organ prolapse (POP) but received intravaginal cystectomy for treating vaginal wall cysts or received radical hysterectomy for treating stage I cervical cancer. The exclusion criteria for the control group were as follows: reception of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) within 3 months; primary symptoms of urinary infection; diseases related to estrogen (myoma, endometriosis, or functional ovarian carcinoma); clinical evidence of (≥ Grade 2) POP and urge UI. All participants were diagnosed through examinations of case history and gynecology as well as assays of urine pressure, ultrasonography, and urodynamics (POP-Q test involved). The anterior vaginal wall biopsy specimens were collected at 1–2 cm from the cervix, including tunica mucosa, submucosa, muscularis, and adventitia. The anterior vaginal wall tissues were immediately frozen at − 80 °C for the subsequent real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR). All experiments were conducted with the approval of the Ethical Committee of Zhengzhou Central Hospital of Zhengzhou University, and all patients signed the written informed consent.

Cell culture

Female vaginal wall fibroblasts (FVWFs) were prepared from the fresh vaginal wall tissues of a single control subject. The tissues were rinsed 3 to 5 times using phosphate buffer saline (PBS) containing 1% double antibiotic solution to remove subcutaneous blood and necrotic tissues, and then were cut into 1 mm3 sections. The sections were heated using 1% collagenase I (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 3 h, digested using 0.25% trypsin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 5 min, and then 2 mL fetal bovine serum (FBS) was added to stop the digestion. The Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 15% FBS was slowly poured into the culture flask, and the medium was changed every 2 days. When FVWF density reached 70%, cell passage was performed. Stable primary FVWFs were harvested after about 15 days, and subsequent experiments were conducted using FVWFs of the 4th generation.

Identification of FVWFs

The stable FVWFs removed from the wall tissues were placed on a slide, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sinopharm Chemical Reagents Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) at 4 °C for 15 min, and then permeated with 0.5% Triton X-1000 (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) at 4 °C for 20 min. After washing with PBS, FVWFs were blocked with 5% goat serum at room temperature for 30 min, incubated overnight with rabbit anti-vimentin (1:500; ab92547; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) and mouse anti-cytokeratin 19 (1:500; ab7754; Abcam) at 4 °C, and then incubated with Alexa Fluor® 488 fluorescent-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:200; ab150077; Abcam) and Alexa Fluor® 594 fluorescent-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:200; ab150116; Abcam) for 1 h. The cells were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Beyotime) at room temperature for 5 min. Last, cell fluorescence was observed using a fluorescence microscope (Olympus BX53; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Cell treatment

Refereeing to the methods we carried out previously (H. Zhang et al. 2022), FVWFs were treated with different doses (0, 0.5, 1, 5, and 10 ng/mL) of IL-1β for 24 h, and FVWFs treated with 0 ng/mL IL-1β were served as the blank control. And 100 nM each of miR-34a and pcDNA3.1-Nampt as well as the corresponding negative controls were transfected into FVWFs based on the instructions of Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Maryland, USA) (Yang et al. 2018). All plasmids were obtained from Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). After transfection for 48 h, FVWFs were subjected to stimulation for 24 h using 10 ng/mL IL-1β for the following experiments.

Cell counting kit-8 assay

CCK-8 assay was carried out to detect cell viability, according to the previous methods (Fu et al. 2021). After IL-1β stimulation, FVWFs in the logarithmic phase were seeded in 96-well plates at 1 × 104 cells/well. Then, 10 µL CCK-8 solution (Sigma) was added to each well and the cells were incubated for 2 h. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm using an Epoch Microplate spectrophotometer (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA) to quantify cell viability.

RT-qPCR

The total RNA content was collected from FVWFs and the anterior vagina wall tissues via TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). The amount of extracted RNA was quantified by measuring the absorbance at 260 nm using a UV-3100PC nanodrop, and the RNA purity was measured by calculating the absorbance ratio at 260 nm and 280 nm. RNA (1 μg) was reverse-transcribed into cDNA by a PrimeScript RT kit (Applied Biosystem, Foster City, CA, USA). qPCR was conducted on the ABI prism 5700 Sequence Detection system (Applied Biosystems). Total liquid with 25 μL and TaqMan qPCR Master Mix reagent were used for amplification. RT-qPCR underwent 35 circles using LightCycler 480 machine (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). mRNA expression was identified using the 2-step cycles method. ABI Prism 5700 SDS software (Applied Biosystem) was adopted for data analysis. The primer sequences are shown in Table 1. U6 (L. Jiang et al. 2021a, b) and GAPDH were served as internal references for miR and mRNA detection, respectively, and the data were analyzed using the 2−△△Ct method.

Table 1.

qPCR primers

| Forward Primer (5′-3′) | Reverse Primer (5′-3′) | |

|---|---|---|

| miR-34a | GCCGAGGGCCAGCTGTGA | CTCAACTGGTGTCGTGGA |

| Nampt | CGGCCCGAGATGAATCCT | TCATAAAGCCTAATGATG |

| COL1A | GGTCTAGACATGTTCAGC | GGAGGGAGTTTACAGGAA |

| ACAN | AGGTGAACTATGACCACT | AAGCTCTTCTCAGTGGGC |

| TIMP-1 | GAACCCACCATGGCCCCC | GGGCAGGATTCAGGCTAT |

| MMP-2 | ACCTAGCACATGCAATAC | AGGGCCAGCTCAGCAGCC |

| MMP-9 | GCCCTCACCATGAGCCTC | ACGGGAGCCCTAGTCCTC |

| U6 | GTGCTCGCTTCGGCAGCA | AAAATATGGAACGCTTCA |

| GAPDH | CTCAACTACATGGTTTAC | CCAGGGGTCTTACTCCTT |

Western blot

Western blot was conducted based on previously published methods (Fu et al. 2021). Total protein of the anterior vagina wall tissues and FVWFs was extracted using RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime), and then, the protein concentration was determined using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) method. The extracted protein samples (40 μg) were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), shifted to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (Beyotime), and blocked with 5% skim milk for 1 h. The membrane was incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-Nampt, anti-collagen type I (COL1A; 1:1000; ab96723; Abcam), anti-aggrecan (ACAN; 1:1000; ab3778; Abcam), anti-tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1; 1:1000; ab211926; Abcam), anti-matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2; 1:1000; ab92536; Abcam), anti-matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9; 1:1000; ab76003; Abcam), anti-microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 (LC3) II/I (1:2000; ab192890; Abcam), anti-Beclin-1 (1:2000; ab207612; Abcam), and anti-β-actin (1:5000; ab6276; Abcam). Then, the membrane was incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit second antibody IgG (1:2000; ab6721; Abcam) and HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:2000; ab6789; Abcam) for 1 h. With β-actin as the internal reference, the protein bands were measured using the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) method, and the gray values of the bands were analyzed using ImageJ software 1.48U (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Transduction of mCherry-GFP-LC3 adenovirus and autophagy test

Autophagy flux was detected via the transduction of mCherry-GFP-LC3 adenovirus (Guan et al. 2019). FVWFs were seeded in 24-well plates at 1 × 105 cells/well in a humid environment at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and 95% air. mCherry-GFP-LC3 adenovirus was transduced into the cells at 40 multiplicity of infection (MOI) for 24 h. After transduction, the cells were cultured using the fresh medium at 37 °C for 24 h. Three regions were randomly selected for the calculation of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) number and the mCherry point number in each cell through a fluorescence microscope (Olympus).

Bioinformatics

The downstream genes of miR-34a and the predicating intersection were predicated via databases TargetScan (http://www.targetscan.org/vert_72/) (Agarwal et al. 2015), Starbase (https://starbase.sysu.edu.cn) (J. H. Li et al. 2014) and miRTarbase (http://carolina.imis.athena-innovation.gr/diana_tools/web/index.php?r=tarbasev8%2Findex) (H. Y. Huang et al. 2020a, b). Thereafter, the binding sites between miR-34a and Nampt were predicted via Starbase.

Dual-luciferase reporter gene assay

We performed dual-luciferase reporter gene assay according to a preceding study (Chen et al. 2017). The binding sites between miR-34a and Nampt were predicted via Starbase. The wild-type and mutant-type 3’UTR sequences of Nampt were provided by GenePharma (Shanghai, China) and sub-cloned into the pGL3 promoter vector (Promega, Madison, USA) containing luciferase reporter genes to construct Nampt-WT and Nampt-MUT, respectively. When FVWFs in 24-well plates reached 70% confluence, the above plasmids were co-transfected into FVWFs with miR-34a-mimic or mimic-NC based on the manufacturer’s protocol. After 48 h, the luciferase activity of the cells was verified via luciferase assay kits (Beyotime).

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 8.0 statistical software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) was used for statistical analysis and data mapping. Measurement data were indicated as mean ± standard deviation. The data between two groups were compared using t-test; one-way ANOVA or two-way ANOVA was used for comparisons among multiple groups; Tukey’s test was used for the post-hoc test; p < 0.05 indicated that the difference was statistically significant.

Results

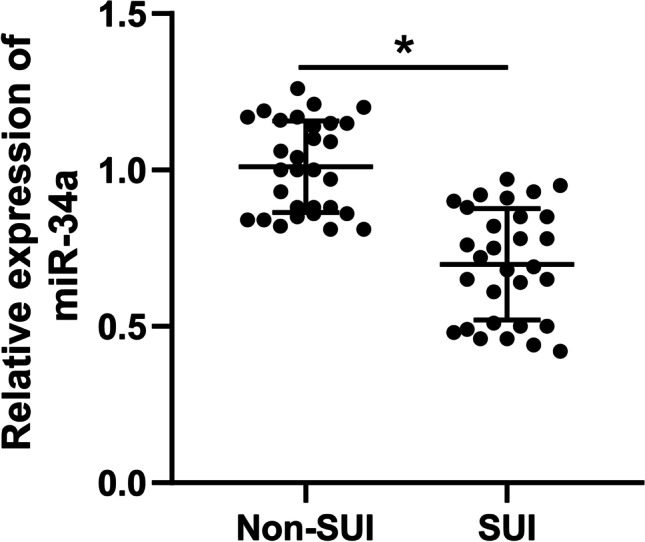

Decline of miR-34a in SUI patients

To explore the possible mechanism of miR-34a in SUI, we collected the anterior vaginal wall tissues of SUI patients and non-SUI subjects to examine miR-34a expression. RT-qPCR results revealed that miR-34a expression in the tissues of SUI patients was notably lower than that of non-SUI subjects (p < 0.05; Fig. 1), which confirmed that miR-34a was under-expressed in SUI patients.

Fig. 1.

Decline of miR-34a in SUI patients. RT-qPCR was used to examine miR-34a expression in the anterior vaginal wall tissues of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) patients and non-SUI subjects (N = 30). The data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation; data in panels were verified using t-test; * p < 0.05

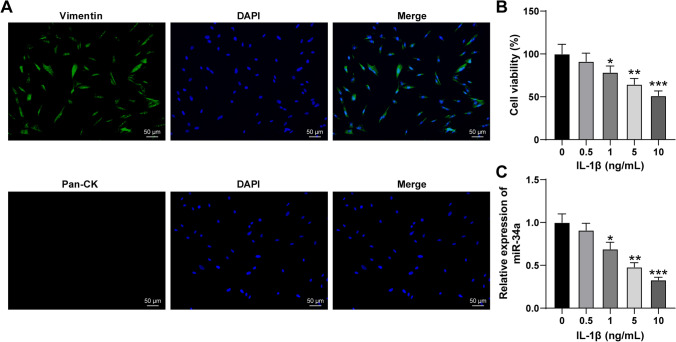

Decline of miR-34a in IL-1β-treated FVWFs

To further probe miR-34a expression in FVWFs, we isolated FVWFs from non-SUI subjects and cultured FVWFs for the following experiments. Immunofluorescence assay was conducted to identify FVWFs, and showed that vimentin in FVWFs was positively expressed while keratin was negatively expressed (p < 0.05; Fig. 2A). Next, we treated FVWFs with different concentrations of IL-1β and found that the stronger the concentration of IL-1β, the greater its effect of it on cell viability. Of note, when the concentration of IL-1β reached 10 ng/mL, the cell viability decreased to half of the original level, which meant that the IC50 of IL-1β was 10 ng/mL (p < 0.05; Fig. 2B). RT-qPCR was used to verify miR-34a expression, which showed that miR-34a was downregulated in IL-1β-treated FVWFs and decreased with the increase of IL-1β concentration (p < 0.05; Fig. 2C). And IL-1β at a concentration of 10 ng/mL was chosen for subsequent tests.

Fig. 2.

Decline of miR-34a in IL-1β-treated FVWFs. The female vaginal wall fibroblasts (FVWFs) were isolated from non-SUI subjects. A Immunofluorescence assay was conducted to verify the expressions of vimentin and keratin in cells. Then, FVWFs were treated with interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β; 0.5, 1, 5, or 10 ng/mL) for the establishment of SUI models, with FVWFs treated with 0 ng/mL IL-1β as the blank control. B The cell viability of IL-1β-treated FVWFs was verified via CCK-8 assay; C RT-qPCR was used to identify miR-34a expression in IL-1β-treated FVWFs. The cell experiment was repeated 3 times independently; data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Data in panels B and C were analyzed using one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. *A comparison with 0 ng/mL IL-1β, p < 0.05; **A comparison with 0 ng/mL IL-1β, p < 0.001; ***A comparison with 0 ng/mL IL-1β, p < 0.0001

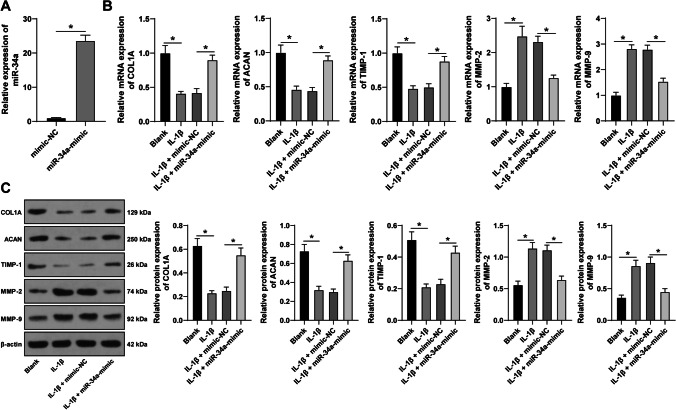

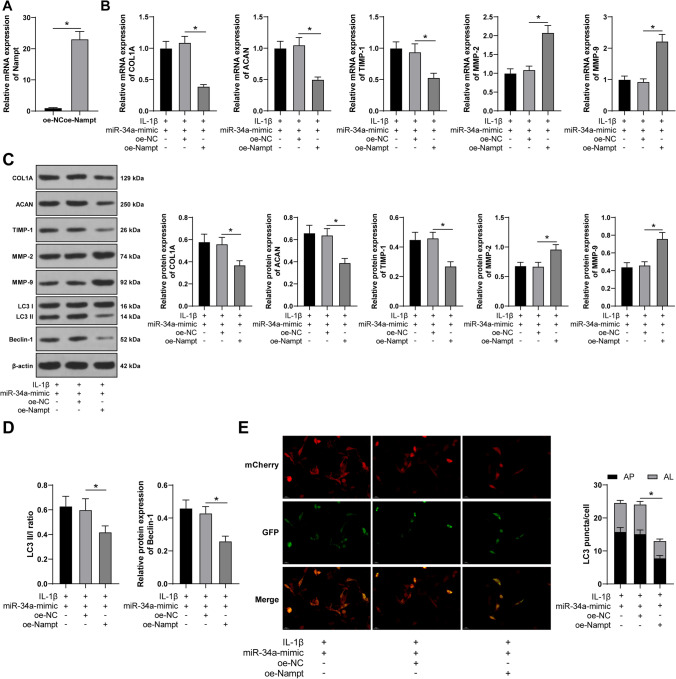

miR-34a overexpression attenuates ECM degradation in IL-1β-treated FVWFs

To investigate the roles of miR-34a on ECM degradation in SUI, miR-34a in FVWFs was overexpressed (p < 0.05; Fig. 3A), and combined with 10 ng/mL IL-1β-treated FVWFs for a joint experiment. After IL-1β treatment, ECM-related proteins were detected. The expressions of COL1A, ACAN, and TIMP-1 in IL-1β-treated FVWFs were declined, whereas the expressions of MMP-2 and MMP-9 were increased (p < 0.05; Fig. 3B, C). After miR-34a expression, COL1A, ACAN, and TIMP-1 were increased, while MMP-2 and MMP-9 were decreased (p < 0.05; Fig. 3B, C). The above findings revealed that miR-34a overexpression could suppress ECM degradation in IL-1β-treated FVWFs.

Fig. 3.

miR-34a overexpression attenuates ECM degradation in IL-1β-treated FVWFs. Plasmid miR-34a-mimic was transfected into FWVFs, with mimic-NC as a control. A The transfection efficacy was detected via RT-qPCR. Then the transfected FWVFs were treated with 10 ng/mL interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β). RT-qPCR (B) and Western blot (C) were conducted to identify the expressions of ECM-related proteins collagen type I (COL1A), aggrecan (ACAN), tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1), matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2), and matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9). The cell experiment was repeated 3 times independently; data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Data in panel A were verified using t-test; data in panels B and C were analyzed using one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test; *p < 0.05. FVWFs female vaginal wall fibroblasts

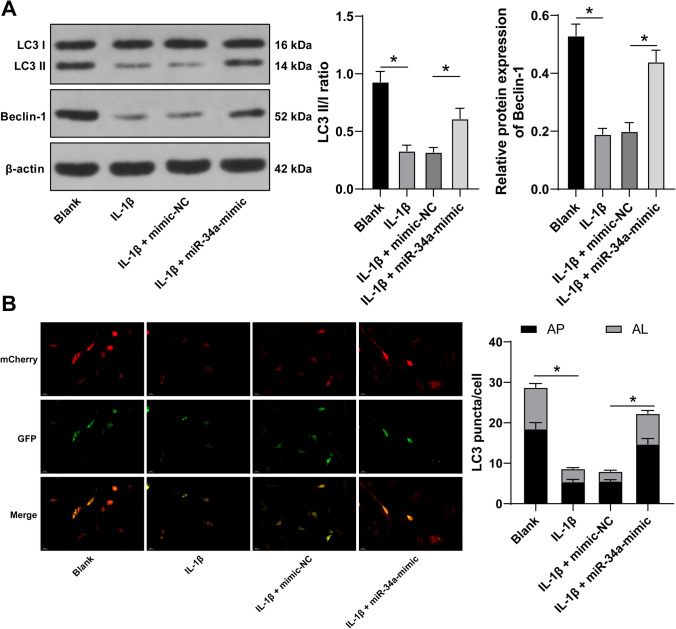

miR-34a overexpression induces autophagy in IL-1β-treated FVWFs

miR-34a can induce autophagy while autophagy can affect ECM degradation (Chen et al. 2021; F. Liu et al. 2019a, b). Hence, we speculated that miR-34a can affect ECM degradation by regulating autophagy. The changes in autophagy in IL-1β-treated FVWFs were detected, and the testing results showed that the microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 (LC3) II/I ratio and Beclin-1 expression were declined (p < 0.05; Fig. 4A), and the number of autophagosomes was reduced (p < 0.05; Fig. 4B). However, after miR-34a overexpression, the LC3 II/I ratio and Beclin-1 expression were elevated (p < 0.05; Fig. 4A), and the autophagosome number was increased (p < 0.05; Fig. 4B). The above results suggested that miR-34a overexpression induced autophagy in IL-1β-treated FVWFs.

Fig. 4.

miR-34a overexpression induces autophagy in IL-1β-treated FVWFs. A Western blot was performed to identify the autophagy marker microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 (LC3) II/I ratio and Beclin-1 expression. B Transduction of mCherry-GFP-LC3 adenovirus was conducted to detect autophagosome number in the cells (notes for the merge image: the yellow spots (AP) represent autophagosomes; the red spots (AL) represent autolysosome). The cell experiment was repeated 3 times independently; data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Data in panel A were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and data in panel B were analyzed using two-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test; * p < 0.05. IL-1β interleukin 1 beta

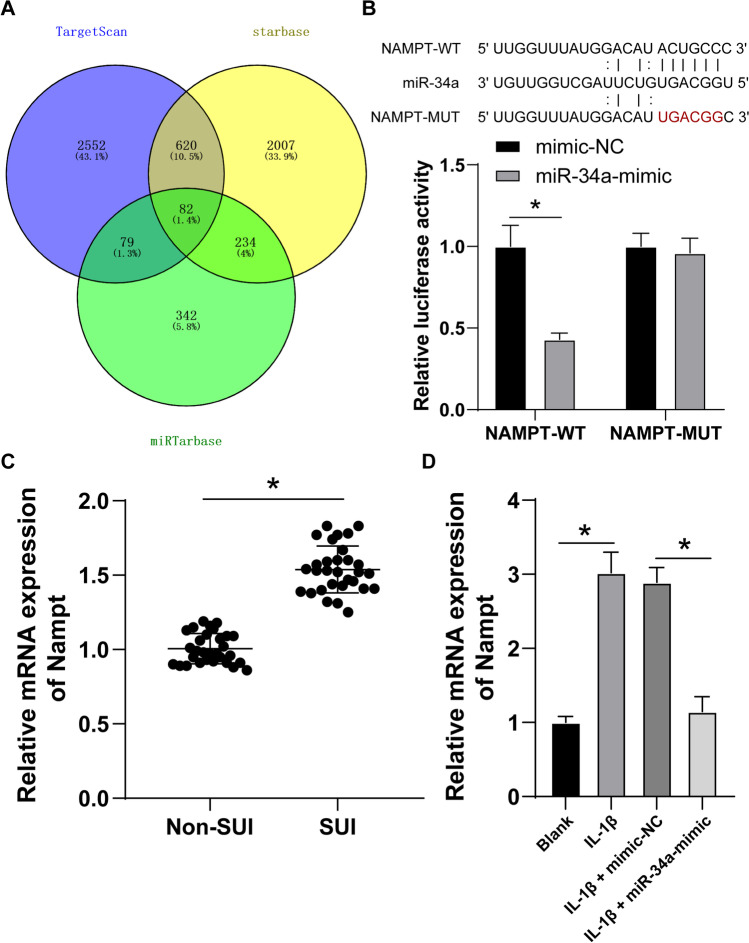

Nampt is a downstream target of miR-34a

Next, we validated the downstream mechanism of miR-34a in ECM degradation. The Starbase, miRTarBase, and TargetScan were used to predict and screen the downstream genes of miR-34a (p < 0.05; Fig. 5A). As we concluded in a previous study, Nampt can promote ECM degradation of fibroblasts in SUI (H. Zhang et al. 2022), and hence, we decided to investigate the underlying interaction between miR-34a and Nampt. Thereafter, the binding relation between Nampt and miR-34a was verified through dual-luciferase reporter gene assay (p < 0.05; Fig. 5B). Then, RT-qPCR was used to examine Nampt expression in SUI patients and IL-1β-treated FVWFs, and the testing results displayed that the mRNA level of Nampt in the anterior vaginal wall tissues of SUI patients was higher than that of in non-SUI subjects (p < 0.05; Fig. 5C), and Nampt mRNA was elevated in IL-1β-treated FVWFs while decreased after miR-34a overexpression (p < 0.05; Fig. 5D). The above findings indicated that miR-34a targeted Nampt transcription.

Fig. 5.

Nampt is a downstream target of miR-34a. A The downstream genes of miR-34a were predicted and screened via online databases; B Dual-luciferase reporter gene assay was adopted to examine the binding relationship; RT-qPCR was used to verify the mRNA level of Nampt in the anterior vaginal wall tissues (C) and FVWFs (D); C N = 30. Data in panels B and D were repeated 3 times independently; data in panel C were verified using t-test; data in panel B were analyzed using two-way ANOVA and data in panel D were analyzed using one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test; *p < 0.05. SUI stress urinary incontinence, IL-1β interleukin 1 beta, FVWFs female vaginal wall fibroblasts

Nampt overexpression inhibits autophagy induced by miR-34a overexpression and facilitates ECM degradation in IL-1β-treated FVWFs

Subsequently, we investigated the involvement of Nampt in the regulation of miR-34a-induced autophagy on ECM degradation. Overexpressing plasmid pcDNA3.1-Nampt was used to overexpress Nampt in FVWFs (p < 0.05; Fig. 6A), followed by a joint experiment with IL-1β-treated FVWFs overexpressing miR-34a. The results showed that after Nampt overexpression, COL1A, ACAN, and TIMP-1 in FVWFs were declined; MMP-2 and MMP-9 were elevated (p < 0.05; Fig. 6B, C); the LC3 II/I ratio and Beclin-1 expression were reduced (p < 0.05; Fig. 6D); and autophagosome number was declined (p < 0.05; Fig. 6E). The above results suggested that Nampt overexpression inhibited miR-34a overexpression-induced autophagy and facilitated ECM degradation in IL-1β-treated FVWFs.

Fig. 6.

Nampt overexpression inhibits autophagy induced by miR-34a overexpression and facilitates ECM degradation in IL-1β-treated FVWFs. FWVFs were transfected with pcDNA3.1-Nampt (oe-Nampt) with pcDNA3.1-NC (oe-NC) as a control. A The transfection efficacy was detected via RT-qPCR. The transfected cells were combined with miR-34a-mimic. B, C RT-qPCR and Western blot were conducted to identify the expressions of ECM-related proteins collagen type I (COL1A), aggrecan (ACAN), tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1), matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2), and matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9); D Western blot was performed to identify the autophagy marker microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 (LC3) II/I ratio and Beclin-1 expression. E Transduction of mCherry-GFP-LC3 adenovirus was conducted to detect autophagosome number in the cells (notes for the merge image: the yellow spots (AP) represent autophagosomes; the red spots (AL) represent autolysosome). The cell experiment was repeated 3 times independently; data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation; data in panel A were analyzed using t-test; data in panels B–D were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and data in panel E were analyzed using two-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test; *p < 0.05. IL-1β interleukin 1 beta, FVWFs female vaginal wall fibroblasts

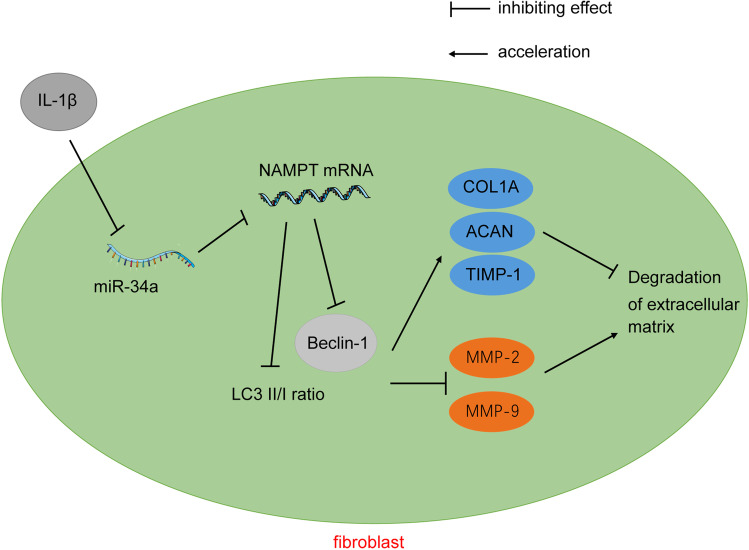

Discussion

The impairment of ECM in connective tissues is one hallmark of SUI progression, and ECM change is closely related to the urethra mechanism under pressure (Goepel and Thomssen 2006; Huang et al. 2013). Notably, preceding studies showed that IL-1β is a trigger of ECM degradation in cells such as nucleus pulposus cells and chondrocytes (Gao et al. 2020; Y. Zhang et al. 2019). And, miRs are known to modulate ECM dysregulation and certain miRs have been found in disorders related to ECM disruption or breakdown (Akbari Dilmaghnai et al. 2021). Herein, we proved for the first time that miR-34a inhibited ECM degradation and induced autophagy in IL-1β-treated FVWFs in SUI via targeting Nampt (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Mechanism diagram. miR-34a modulates ECM metabolism of FVWFs in SUI via Nampt-mediated autophagy. miR-34a was poorly expressed in SUI, and IL-1β treatment inhibited miR-34a expression in FVWFs, and miR-34a inhibit Nampt transcription to accelerate autophagy, thus suppressing ECM degradation

A previously reported study showed that monocrotaline-induced miR-34a can suppress ECM accumulation (F. Li et al. 2021). Besides, differentially expressed miR-34a has impacts on fibroblasts in different disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis, lung fibrosis, and diabetic cardiomyopathy (Cui et al. 2017; Deng et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2021). In this work, the anterior vaginal wall tissues of SUI and non-SUI subjects were harvested to identify miR-34a expression. The detection result of RT-qPCR illustrated poor miR-34a expression in SUI patients. Then, we isolated FVWFs from non-SUI subjects and treated FVWFs with various concentrations of IL-1β. We found that miR-34a expression was suppressed in IL-1β-treated FVWFs. At last, FVWFs treated with 10 ng/mL IL-1β were chosen for subsequent experiments.

Dysregulated miR-34a is associated with Gleason grade and alters the levels of ECM-related proteins and regulates ECM (Lichner et al. 2015). In this work, FVWFs overexpressing miR-34a underwent a joint experiment with 10 ng/mL IL-1β-treated FVWFs. After miR-34a overexpression, COL1A, ACAN, and TIMP-1 were elevated while MMP-2 and MMP-9 were declined in IL-1β-treated FVWFs. Existing studies reported that low-intensity pulsed ultrasound expedites ECM synthesis with the elevation of ACAN, TIMP-1, and Col-II (X. Zhang et al. 2016), and irigenin hampers ECM degradation in nucleus pulposus cells that are stimulated by TNF-α via repressing MMP-2/3/9/13 but elevating ACAN and Col-II (He et al. 2021). Through literature review, we found that miR-34a can indirectly modulate ECM deposition via regulating c-Ski expression (C. Zhang et al. 2018). Additionally, in rats with monocrotaline triggered-pulmonary arterial hypertension, elevated miR-34a is accompanied by decreased levels of MMP-9 and MMP-2, and eventually decreases ECM accumulation (F. Li et al. 2021). The above results indicated that miR-34a overexpression could suppress ECM degradation induced by IL-1β-treated FVWFs.

miR-34a mediates autophagy to possess a protective effect on cells to prevent cells from damage (Ni et al. 2020; Zhu et al. 2019). Furthermore, Liu et al. concluded that isorhamnetin suppresses liver fibrosis through limiting autophagy and repressing ECM formation (N. Liu et al. 2019a, b), and autophagy induced by high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) has an impact on ECM degradation (B. Fu et al. 2020). Herein, we examined autophagy levels in IL-1β-treated FVWFs and found that the LC3 II/I ratio and Beclin-1 expression were declined, and the number of autophagosomes was reduced. However, miR-34a overexpression reversed the above results. miR-34a overexpression reversed the suppression of autophagy induced by SNHG7 elevation while miR-34a knockdown hampered autophagy in osteoarthritis cells (Tian et al. 2020), and autophagy enhancement ameliorated matrix degradation (Hong et al. 2020). The above findings indicated that miR-34a overexpression induced autophagy in IL-1β-treated FVWFs.

Afterwards, we determined to explore the downstream mechanisms by which miR-34a affected ECM degradation. Through the predictions of databases, we focused on Nampt. Nampt is related to replicative senescence in fibroblasts (Sanokawa-Akakura et al. 2016). And, Nampt targeted by miR-127-5p is involved in cell proliferation and inflammation and ECM degradation of chondrocytes in osteoarthritis (C. Liu et al. 2021). Then, we confirmed the binding relation between miR-34a and Nampt and detected that the mRNA level of Nampt was notably elevated in SUI patients and IL-1β-treated FVWFs but declined after miR-34a overexpression. The above findings indicated that miR-34a targeted and suppressed Nampt transcription.

Furthermore, amounting studies illustrated the negative relation between miR-34a and Nampt (Collier and Schnellmann 2020; Pi et al. 2021). Later, Nampt in FVWFs was overexpressed and subjected to a joint experiment with IL-1β-treated FVWFs overexpressing miR-34a. We disclosed that Nampt overexpression facilitated ECM degradation and limited autophagy. Moreover, in our previous study, we confirmed that Nampt knockdown facilitates autophagy of fibroblasts in SUI and further suppresses ECM degradation (H. Zhang et al. 2022). Additionally, a previous study documented that Nampt upregulation promotes cell growth arrest and ECM degradation in IL-1β-treated chondrocytes (Fu et al. 2021). These above-mentioned findings greatly supported the result we obtained that Nampt upregulation reversed the effects of miR-34a overexpression on autophagy and ECM degradation.

To sum up, we proved the mechanism of the miR-34a/Nampt axis in ECM metabolism in fibroblasts of SUI for the first time. Specifically, miR-34a upregulation inhibited Nampt transcription to accelerate autophagy to suppress ECM degradation, thus attenuating SUI. Nonetheless, we only selected 30 specimens for experiments, and we failed to investigate whether miR-34a could regulate other cell functions or target other downstream genes to influence ECM degradation. Going forwards, we will prepare more specimens, probe the roles of miR-34a in other matrices in SUI, and choose more downstream targets of it for in-depth investigation.

Abbreviations

- microRNA-34a

MiR-34a

- SUI

Stress urinary incontinence

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- Nampt/NAmPRTase

Nicotinamide phosphoribosyl transferase

- FVWFs

Female vaginal wall fibroblasts

- IL-1β

Interleukin 1 beta

- ICS

International Continence Society

- TVT

Tension-free vaginal tape

- POP

Pelvic organ prolapse

- HRT

Hormone replacement therapy

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- PBS

Phosphate buffer saline

- FBS

Fetal bovine serum

- DAPI

4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole

- CCK-8

Cell counting kit-8

- RT‑qPCR

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- ECL

Enhanced chemiluminescence

- MOI

Multiplicity of infection

- GFP

Green fluorescent protein

Author contribution

Conceptualization: YZ; validation, research, resources, data reviewing, and writing: HL; review and editing: LW. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

2/23/2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1007/s12192-023-01329-w

Contributor Information

Hongjuan Li, Email: lhj666777@163.com.

Lu Wang, Email: Wanglu091534@163.com.

References

- V Agarwal GW Bell JW Nam DP Bartel 2015 Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs Elife 410.7554/eLife.05005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Akbari Dilmaghnai N, Shoorei H, Sharifi G, Mohaqiq M, Majidpoor J, Dinger ME, Taheri M, Ghafouri-Fard S. Non-coding RNAs modulate function of extracellular matrix proteins. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;136:111240. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki Y, Brown HW, Brubaker L, Cornu JN, Daly JO, Cartwright R. Urinary incontinence in women. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17042. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capobianco G, Madonia M, Morelli S, Dessole F, De Vita D, Cherchi PL, Dessole S. Management of female stress urinary incontinence: a care pathway and update. Maturitas. 2018;109:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Yan J, Li S, Zhu J, Zhou J, Li J, Zhang Y, Huang Z, Yuan L, Xu K, Chen W, Ye W. Atorvastatin inhibited TNF-alpha induced matrix degradation in rat nucleus pulposus cells by suppressing NLRP3 inflammasome activity and inducing autophagy through NF-kappaB signaling. Cell Cycle. 2021;20:2160–2173. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2021.1973707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Li Q, Wang J, Jin S, Zheng H, Lin J, He F, Zhang H, Ma S, Mei J, Yu J. MiR-29b-3p promotes chondrocyte apoptosis and facilitates the occurrence and development of osteoarthritis by targeting PGRN. J Cell Mol Med. 2017;21:3347–3359. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SE, Fu T, Seok S, Kim DH, Yu E, Lee KW, Kang Y, Li X, Kemper B, Kemper JK. Elevated microRNA-34a in obesity reduces NAD+ levels and SIRT1 activity by directly targeting NAMPT. Aging Cell. 2013;12:1062–1072. doi: 10.1111/acel.12135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier JB, Schnellmann RG. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 regulates NAD metabolism during acute kidney injury through microRNA-34a-mediated NAMPT expression. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2020;77:3643–3655. doi: 10.1007/s00018-019-03391-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui H, Ge J, Xie N, Banerjee S, Zhou Y, Antony VB, Thannickal VJ, Liu G. miR-34a inhibits lung fibrosis by inducing lung fibroblast senescence. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2017;56:168–178. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0163OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y, Chen D, Gao F, Lv H, Zhang G, Sun X, Liu L, Mo D, Ma N, Song L, Huo X, Yan T, Zhang J, Luo Y, Miao Z. Silencing of long non-coding RNA GAS5 suppresses neuron cell apoptosis and nerve injury in ischemic stroke through inhibiting DNMT3B-dependent MAP4K4 methylation. Transl Stroke Res. 2020;11:950–966. doi: 10.1007/s12975-019-00770-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng H, Huang X, Fu W, Dong X, Yang F, Li L, Chu L. A Rho kinase inhibitor (Fasudil) suppresses TGF-beta mediated autophagy in urethra fibroblasts to attenuate traumatic urethral stricture (TUS) through re-activating Akt/mTOR pathway: an in vitro study. Life Sci. 2021;267:118960. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu B, Lu X, Zhao EY, Wang JX, Peng SM. HMGB1-induced autophagy promotes extracellular matrix degradation leading to intervertebral disc degeneration. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2020;13:2240–2248. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu S, Fan Q, Xu J, Yu S, Sun M, Ji Y, Liu D. Circ_0008956 contributes to IL-1beta-induced osteoarthritis progression via miR-149-5p/NAMPT axis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;98:107857. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao F, Wang Y, Wu M. Teneligliptin inhibits IL-1beta-induced degradation of extracellular matrix in human chondrocytes. J Cell Biochem. 2020;121:4450–4457. doi: 10.1002/jcb.29662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garten A, Schuster S, Penke M, Gorski T, de Giorgis T, Kiess W. Physiological and pathophysiological roles of NAMPT and NAD metabolism. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;11:535–546. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2015.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goepel C, Thomssen C. Changes in the extracellular matrix in periurethral tissue of women with stress urinary incontinence. Acta Histochem. 2006;108:441–445. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan G, Yang L, Huang W, Zhang J, Zhang P, Yu H, Liu S, Gu X. Mechanism of interactions between endoplasmic reticulum stress and autophagy in hypoxia/reoxygenationinduced injury of H9c2 cardiomyocytes. Mol Med Rep. 2019;20:350–358. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2019.10228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haylen BT, de Ridder D, Freeman RM, Swift SE, Berghmans B, Lee J, Monga A, Petri E, Rizk DE, Sand PK, Schaer GN. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21:5–26. doi: 10.1007/s00192-009-0976-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He M, Hu L, Bai P, Guo T, Liu N, Feng F, Zhang J. LncRNA PCNAP1 Promotes hepatoma cell proliferation through targeting miR-340-5p and is associated with patient survival. J Oncol. 2021;2021:6627173. doi: 10.1155/2021/6627173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong J, Li S, Markova DZ, Liang A, Kepler CK, Huang Y, Zhou J, Yan J, Chen W, Huang D, Xu K, Ye W. Bromodomain-containing protein 4 inhibition alleviates matrix degradation by enhancing autophagy and suppressing NLRP3 inflammasome activity in NP cells. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235:5736–5749. doi: 10.1002/jcp.29508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang HY, Lin YC, Li J, Huang KY, Shrestha S, Hong HC, Tang Y, Chen YG, Jin CN, Yu Y, Xu JT, Li YM, Cai XX, Zhou ZY, Chen XH, Pei YY, Hu L, Su JJ, Cui SD, Wang F, Xie YY, Ding SY, Luo MF, Chou CH, Chang NW, Chen KW, Cheng YH, Wan XH, Hsu WL, Lee TY, Wei FX, Huang HD. miRTarBase 2020: updates to the experimentally validated microRNA-target interaction database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:D148–D154. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q, Jin H, Xie Z, Wang M, Chen J, Zhou Y. The role of the ERK1/2 signalling pathway in the pathogenesis of female stress urinary incontinence. J Int Med Res. 2013;41:1242–1251. doi: 10.1177/0300060513493995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Peng Y, Sun J, Li S, Hong J, Zhou J, Chen J, Yan J, Huang Z, Wang X, Chen W, Ye W. Nicotinamide phosphoribosyl transferase controls NLRP3 inflammasome activity through MAPK and NF-kappaB signaling in nucleus pulposus cells, as suppressed by melatonin. Inflammation. 2020;43:796–809. doi: 10.1007/s10753-019-01166-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L, Shi X, Wang M, Chen H. Study on the mechanism of miR-34a affecting the proliferation, migration, and invasion of human keloid fibroblasts by regulating the expression of SATB1. J Healthc Eng. 2021;2021:8741512. doi: 10.1155/2021/8741512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Jiang X, Chen W, Su H, Shen F, Xiao W, Sun W. Puerarin facilitates osteogenesis in steroid-induced necrosis of rabbit femoral head and osteogenesis of steroid-induced osteocytes via miR-34a upregulation. Cytokine. 2021;143:155512. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2021.155512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin M, Wu Y, Wang J, Ye W, Wang L, Yin P, Liu W, Pan C, Hua X. MicroRNA-29 facilitates transplantation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells to alleviate pelvic floor dysfunction by repressing elastin. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2016;7:167. doi: 10.1186/s13287-016-0428-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Wang D, Wang H, Chen L, Sun X, Wan Y. Inhibition of HDAC1 alleviates monocrotaline-induced pulmonary arterial remodeling through up-regulation of miR-34a. Respir Res. 2021;22:239. doi: 10.1186/s12931-021-01832-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JH, Liu S, Zhou H, Qu LH, Yang JH. starBase v2.0: decoding miRNA-ceRNA, miRNA-ncRNA and protein-RNA interaction networks from large-scale CLIP-Seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D92–97. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Yu SS, Zhou CY, Wang K, Wan YC. MicroRNA-206 inhibition and activation of the AMPK/Nampt signalling pathway enhance sevoflurane post-conditioning-induced amelioration of myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion injury. J Drug Target. 2020;28:80–91. doi: 10.1080/1061186X.2019.1616744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichner Z, Ding Q, Samaan S, Saleh C, Nasser A, Al-Haddad S, Samuel JN, Fleshner NE, Stephan C, Jung K, Yousef GM. miRNAs dysregulated in association with Gleason grade regulate extracellular matrix, cytoskeleton and androgen receptor pathways. J Pathol. 2015;237:226–237. doi: 10.1002/path.4568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Cheng P, Liang J, Zhao X, Du W. Circular RNA circ_0128846 promotes the progression of osteoarthritis by regulating miR-127-5p/NAMPT axis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2021;16:307. doi: 10.1186/s13018-021-02428-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Zhang G, Lv S, Wen X, Liu P. miRNA-301b-3p accelerates migration and invasion of high-grade ovarian serous tumor via targeting CPEB3/EGFR axis. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120:12618–12627. doi: 10.1002/jcb.28528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N, Feng J, Lu X, Yao Z, Liu Q, Lv Y, Han Y, Deng J, Zhou Y. Isorhamnetin inhibits liver fibrosis by reducing autophagy and inhibiting extracellular matrix formation via the TGF-beta1/Smad3 and TGF-beta1/p38 MAPK Pathways. Mediators Inflamm. 2019;2019:6175091. doi: 10.1155/2019/6175091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Miao Y, Zhang L, Xu X, Luan Q. MiR-211 protects cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury by inhibiting cell apoptosis. Bioengineered. 2020;11:189–200. doi: 10.1080/21655979.2020.1729322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu TX, Rothenberg ME. MicroRNA. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141:1202–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni T, Lin N, Lu W, Sun Z, Lin H, Chi J, Guo H. Dihydromyricetin prevents diabetic cardiomyopathy via miR-34a suppression by activating autophagy. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2020;34:291–301. doi: 10.1007/s10557-020-06968-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parzych KR, Klionsky DJ. An overview of autophagy: morphology, mechanism, and regulation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20:460–473. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pi C, Ma C, Wang H, Sun H, Yu X, Gao X, Yang Y, Sun Y, Zhang H, Shi Y, Li Y, Li Y, He X. MiR-34a suppression targets Nampt to ameliorate bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell senescence by regulating NAD(+)-Sirt1 pathway. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12:271. doi: 10.1186/s13287-021-02339-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preda A, Moreira S (2019) Stress urinary incontinence and female sexual dysfunction: the role of pelvic floor rehabilitation. Acta Med Port 32:721–726. 10.20344/amp.12012 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sangsawang B, Sangsawang N. Stress urinary incontinence in pregnant women: a review of prevalence, pathophysiology, and treatment. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:901–912. doi: 10.1007/s00192-013-2061-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanokawa-Akakura R, Akakura S, Tabibzadeh S. Replicative senescence in human fibroblasts is delayed by hydrogen sulfide in a NAMPT/SIRT1 dependent manner. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0164710. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theocharis AD, Skandalis SS, Gialeli C, Karamanos NK. Extracellular matrix structure. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2016;97:4–27. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian F, Wang J, Zhang Z, Yang J. LncRNA SNHG7/miR-34a-5p/SYVN1 axis plays a vital role in proliferation, apoptosis and autophagy in osteoarthritis. Biol Res. 2020;53:9. doi: 10.1186/s40659-020-00275-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAC Walma KM Yamada 2020 The extracellular matrix in development Development 14710.1242/dev.175596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wang L, Wang Y, Xiang Y, Ma J, Zhang H, Dai J, Hou Y, Yang Y, Ma J, Li H. An in vitro study on extracellular vesicles from adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells in protecting stress urinary incontinence through microRNA-93/F3 axis. Front Endocrinol (lausanne) 2021;12:693977. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.693977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Lou C, Gao J, Zhang X, Du Y. Corrigendum to LncRNA SNHG16 reverses the effects of miR-15a, 16 on LPS-induced inflammatory pathway [Biomed. Pharmacother. 106 (2018)1661–166. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;133:110894. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Zheng X, Yi X, Lai P, Lan Y. Electromyographic biofeedback for stress urinary incontinence or pelvic floor dysfunction in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv Ther. 2021;38:4163–4177. doi: 10.1007/s12325-021-01831-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Wang JJ. CircRNA hsa_circ_0005105 upregulates NAMPT expression and promotes chondrocyte extracellular matrix degradation by sponging miR-26a. Cell Biol Int. 2017;41:1283–1289. doi: 10.1002/cbin.10761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue M, Li Y, Hu F, Jia YJ, Zheng ZJ, Wang L, Xue YM. High glucose up-regulates microRNA-34a-5p to aggravate fibrosis by targeting SIRT1 in HK-2cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;498:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang SJ, Wang J, Xu J, Bai Y, Guo ZJ. miR-93mediated collagen expression in stress urinary incontinence via calpain-2. Mol Med Rep. 2018;17:624–629. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.7910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Zhang Y, Zhu H, Hu J, Xie Z. MiR-34a/miR-93 target c-Ski to modulate the proliferaton of rat cardiac fibroblasts and extracellular matrix deposition in vivo and in vitro. Cell Signal. 2018;46:145–153. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2018.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Wang L, Xiang Y, Wang Y, Li H. Nampt promotes fibroblast extracellular matrix degradation in stress urinary incontinence by inhibiting autophagy. Bioengineered. 2022;13:481–495. doi: 10.1080/21655979.2021.2009417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Hu Z, Hao J, Shen J. Low intensity pulsed ultrasound promotes the extracellular matrix synthesis of degenerative human nucleus pulposus cells through FAK/PI3K/Akt pathway. Spine Phila Pa 1976. 2016;41:E248–254. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, He F, Chen Z, Su Q, Yan M, Zhang Q, Tan J, Qian L, Han Y. Melatonin modulates IL-1beta-induced extracellular matrix remodeling in human nucleus pulposus cells and attenuates rat intervertebral disc degeneration and inflammation. Aging Albany NY. 2019;11:10499–10512. doi: 10.18632/aging.102472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Qian X, Li J, Lin X, Luo J, Huang J, Jin Z. Astragaloside-IV protects H9C2(2–1) cardiomyocytes from high glucose-induced injury via miR-34a-mediated autophagy pathway. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2019;47:4172–4181. doi: 10.1080/21691401.2019.1687492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]