Abstract

Indigo is a bis-indolic alkaloid that has antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects reported in literature and is a promissory compound for treating chronic inflammatory diseases. This fact prompted to investigate the effects of this alkaloid in the experimental model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. The main aim of this study was to evaluate the potential role of the indigo on oxidative stress and related signaling pathways in primary skeletal muscle cell cultures and in the diaphragm muscle from mdx mice. The MTT and Neutral Red assays showed no indigo dose-dependent toxicities in mdx muscle cells at concentrations analyzed (3.12, 6.25, 12.50, and 25.00 μg/mL). Antioxidant effect of indigo, in mdx muscle cells and diaphragm muscle, was demonstrated by reduction in 4-HNE content, H2O2 levels, DHE reaction, and lipofuscin granules. A significant decrease in the inflammatory process was identified by a reduction on TNF and NF-κB levels, on inflammatory area, and on macrophage infiltration in the dystrophic sample, after indigo treatment. Upregulation of PGC-1α and SIRT1 in dystrophic muscle cells treated with indigo was also observed. These results suggest the potential of indigo as a therapeutic agent for muscular dystrophy, through their action anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and modulator of SIRT1/PGC-1α pathway.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12192-022-01282-0.

Keywords: Indigo, Oxidative stress, Inflammatory process, Activators mitochondrial biogenesis, mdx mice

Introduction

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a genetic X-linked disease characterized by progressive muscle degeneration with a consequent loss of ambulation and severe multisystem complications (Emery 2002). This disease has an estimated incidence of one in every 6000 live male births (Crisafulli et al. 2020). There is currently no cure for DMD and the dystrophic patients live approximately until their 30s, due particularly to medical improvements in respiratory and cardiac care (Landfeldt et al. 2018).

Glucocorticoids, more precisely prednisone and deflazacort, are the main drug treatment for DMD (Gloss et al. 2016). However, their benefits are modest and their continued use causes adverse effects, with weight gain being the most common cause for discontinuing corticosteroid therapy (Moxley et al. 2010). In this sense, the search for new complementary and alternative medicine approaches, which may contribute to the improvement of the dystrophic phenotype, are necessary. Among these, the therapies that have anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties stand out (Verhaart and Aartsma-Rus 2019), since the oxidative stress and exacerbated inflammatory response effectively contribute to muscle damage in DMD (Whitehead et al. 2006).

Several natural products have pharmacological potential, especially in the treatment of inflammation and oxidative stress (Suntar et al. 2020). There are different secondary metabolites of plant origin, such as flavonoids, terpenes, quinones, catechins, and alkaloids, acting on several inflammatory and oxidative modulators (Suntar et al. 2020). Herrendorff et al. (2016) reported the discovery of several plant-derived alkaloids that are novel small bioactive molecules with a therapeutic potential for myotonic dystrophy type I.

Alkaloids are a class of amino acid-derived nitrogen-containing organic compounds with low molecular weight (Moreira et al. 2018). In plants, the alkaloids are secondary metabolites produced in response to environmental modulations and to stressful situations, which lead alkaloids to have structure diversity and relevant biological activities (Taha et al. 2009). These features make alkaloids potential candidate compounds for new drug development. Among the many alkaloids researched for new drugs is indigo (Fig. 1S and 2S in the Supplementary Information).

Indigo is a bis-indole alkaloid that occurs in Indigofera spp. (Fabaceae), and which has antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects reported in literature and is a promissory compound for treating chronic inflammatory diseases (Maugard et al. 2001; Andreazza et al. 2015; De Almeida et al. 2019). The evaluation of the indigo alkaloid in the treatment of different kinds of inflammations or in oxidative damage showed promising results (Farias-Silva et al. 2007; Chang et al. 2010). Farias-Silva et al. (2007) showed that indigo presents gastroprotective effects mediated by non-enzymatic antioxidant mechanisms and by the inhibition of polymorphonuclear neutrophil infiltration. In addition, it was also reported that the anti-inflammatory therapeutic effect of indigo occurred due to the inhibition of the tumor necrosis factor-induced vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 expression in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (Chang et al. 2010). The potential role of indigo in colitis therapy with intestinal anti-inflammatory activity in TNBS-induced colitis was evaluated. Results suggest that indigo decreased the macroscopic inflammation score, decreased weight/length ratio of the colon, and the indigo action on colitis should mainly involve inhibiting or reducing the release of inflammatory mediators such as COX-2 (De Almeida et al. 2019).

Considering the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of indigo reported in literature, we have examined, in this study, the possible role of this alkaloid on oxidative stress and related signaling pathways in primary skeletal muscle cell cultures and in the diaphragm muscle, both in mdx mice, the experimental model of DMD.

Materials and methods

Animals

C57BL/10 (C57BL/10ScCr/PasUnib) and mdx (C57BL/10-Dmdmdx/PasUnib) mice were used in all experiments. The experimental protocols were developed according to the ethical principles in animal experimentation adopted by the Brazilian College of Animal Experimentation and tested by the Ethics Committee in Animal Experimentation of UNICAMP, São Paulo (CEUA #4287-1).

In vitro studies

Primary skeletal muscle cell cultures

In order to perform primary muscle cell cultures, pelvic limb muscles were collected from 28 days old C57BL/10 and mdx mice. The protocol of primary skeletal muscle cell cultures was previously described by Rando and Blau (1994) and Mizobuti et al. (2019). In brief, the satellite cells (5×104 cells/cm2) were plated in multiwell plates and after the proliferation phase, the myotube differentiation was induced by the inclusion of a fusion medium. For the development of the cell culture, these cells were maintained in a CO2 (5%) incubator at 37°C. Three independent primary skeletal muscle cell cultures, with 5–7 days development, were used in all experiments.

Indigo treatment experimental design

The skeletal muscle cell cultures were divided into seven experimental groups: (1) ctrl (cell cultures from muscles of C57BL/10 mice, used as a control); (2) mdx (cell cultures from muscles of mdx mice without pharmacological treatment); (3) mdxprop (cell cultures from muscles of mdx mice in the presence of 0.01% propylene glycol, vehicle); (4) IND25 (cell cultures from mdx mouse muscles treated with indigo (Sigma-Aldrich) at 25.00μg/mL); (5) IND12.5 (cell cultures from muscles of mdx mice treated with indigo at 12.50μg /mL); (6) IND6.25 (cell cultures from muscles of mdx mice treated with indigo at 6.25μg/mL); and (7) IND3.12 (cell cultures from muscles of mdx mice treated with indigo at 3.12μg/mL).

While for cell viability analysis, by MTT and Neutral Red Uptake assays, the mdx muscle cells were treated with different doses of indigo (3.12, 6.25, 12.50, and 25.00 μg/mL), the live/dead cell viability assay, and the other analyses were performed in mdx muscle cells without pharmacological treatment and in cells treated with indigo at the chosen dose (25.00 μg/mL - IND25) after cell viability assays (Fig. 2S in the Supplementary Information).

Cell viability and proliferation

MTT analysis

This colorimetric analysis was performed for quantification of cell metabolic activity in response to different doses of indigo (25.00μg, 12.50 μg, 6.25 μg, and 3.12μg). The protocol of this assay was previously described by Macedo et al. (2015) and Mizobuti et al. (2019). Briefly, after the MTT incubation phase, the crystals were dissolved with isopropanol acid and the amount of formazan product was measured by a spectrophotometer (Synergy H1, Hybrid Reader, Biotek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA) at 570 nm with a 655-nm reference wavelength.

Neutral Red

This colorimetric analysis was performed to quantify membrane permeability and lysosomal cell activity in response to different doses of indigo (25μg, 12.5 μg, 6.25 μg, and 3.12 μg). The protocol of this assay was previously described by Borenfreund and Puerner (1985). Briefly, primary muscle cells were washed in PBS once and NR medium was added (250 μl) and the cells were incubated (37°C) for 3 h. After this period, the NR medium was removed, the muscle cells were washed in PBS, and desorption solution was added. A shaker was used to extract the NR from the cells and the absorbance was measured in a spectrophotometer (Synergy H1, Hybrid Reader, Biotek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA) at 540 nm.

Live/dead assay

The protocol of live/dead cell viability assay was previously described by Mizobuti et al. (2019). In brief, the ethidium homodimer-1 (EthD-1) enters cells with damaged membranes and produces a strong red fluorescence in dead cells, while the polyanionic dyecalcein-green enters live cells, generating an intense uniform green fluorescence. After exposure to EthD-1 and polyanionic dyecalcein-green, the cells were photographed using a fluorescence optical microscope (Nikon®) connected to a Nikon camcorder with 20× magnification.

Detection of H2O2

Amplex® Red assay kit (Molecular Probes, Life Technologies, California, EUA) was used to determine the H2O2 levels according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cells were kept at 37°C in Krebs Ringer solution (4.85mL) and loaded with the Amplex red probe (50μM) and horseradish peroxidase (0.1U/mL) for 30min. After this period, 100μL of the medium was collected and the fluorescence intensity determined at 530-nm excitation and 590-nm emission in a Multi-Mode Microplate Reader Model Synergy H1M equipment (Bio-Tek Instruments). As a control experiment, positive and negative controls were prepared. For the positive control, 20mM of H2O2 in a buffer solution was used. In the negative control, only the buffer solution was used. Triplicate analyzes were performed.

Western blotting

Culture cells were washed with PBS, scraped, and immediately homogenized in 300μL of buffer for homogenization (Triton X-100 1%, Tris-HCl 100mM (pH 7.4), 100mM sodium pyrophosphate, 100mM sodium fluoride, 10mM ETDA, 10mM sodium orthovanadate, 2mM PMSF, and 0.1mg/ml aprotinin). The extracts were centrifuged at 11,000rpm at 4°C for 20 min and the supernatant was used for analysis of the total extract method (BRADFORD). Protein (30μg) was applied on a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel in a Bio-Rad electrophoresis device (mini-Protean, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, CA, USA). The gel electrotransfer to the nitrocellulose membrane was performed in 90 min at 120V (constant) in a Mini Trans-Blot® transfer device (Bio-Rad). Subsequently, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight with gentle motion. To detect immunoreactive bands, membranes were exposed to Clarity Western ECL solution (Bio-Rad) for 5 min, followed by exposure in the G-Box Chamber. The quantification of optical densitometry was verified using the Gene Tools from the Syngene program. In order to normalize the obtained data, an internal control was used by incubating the samples with β-actin antibody (Sigma-Aldrich A1978).

Primary antibodies are 4-HNE (BIO-RAD AHP1251), anti-Catalase (Sigma-Aldrich C0979), anti-SOD-2 (Sigma-Aldrich SAB2501676), anti-GSR (Sigma-Aldrich SAB2108147), anti-GPx1 (Sigma-Aldrich SAB2502102), NF-kB (BIO-RAD AHP1342), TNF (Cell Signaling #3707S); PGC-1α (Abcam ab54481); SIRT1 (Cell Signaling C14H4), PPARδ (Invitrogen PA1-823A), and β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich A1978). Peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies are anti -rabbit (Promega Corporation W4011), anti-mouse (Promega Corporation W4021), and anti-goat (KPL 14-13-06).

Dosage of sulfhydryl group

The samples (obtained in the same way as the samples used for Western Blotting) were centrifuged (12,000rpm, at 4°C, for 15 min) and the supernatant diluted (1:10) in a sodium phosphate buffer (0.1M pH=7.4). Then, the absorbance measure of 100μL of the sample was performed, plus 100μL of Tris solution (1.0mM) and EDTA (0.02mM), at 412nm (A1). Next 20μL of 5.5 dithiobis (2-nitrobenzoic acid) diluted in methanol (DTNB - 0.01mM) was added and then a new measurement was taken (A2), at 412nm, after 15 min of reaction, to determine non-protein sulfhydryl groups (GSH). The concentration of sulfhydryl (thiol) groups is given by (A1-A2) × 1.57 (Faure and Lafond 1995).

In vivo studies

Indigo treatment

On the 14th day of postnatal life (the period before muscle degeneration/regeneration cycles in mdx mice), the mdx mice were weighed and treated daily until the 28th day with commercial indigo (Sigma-Aldrich 229296-25G) 3mg/kg and/or with 0.1 mL of saline solution through intraperitoneal (IP) injections. The animals were divided into two experimental groups: the mdx group (treated with saline solution; n=14) and the mdxIND group (treated with indigo at 3mg/kg; n=14). Seven animals from each group were used to determine creatine kinase dosage and histopathological analysis, while the other seven animals from each group were used for western blotting analysis and dosage of sulfhydryl groups. After the end of the treatment (24h), the animals were euthanized with a 2% xylazine hydrochloride solution (Vyrbaxyl, Virbac) and ketamine hydrochloride (Francotar, Virbac) in a 1:1 (v/v) proportion and a dose of 0.1mL/30g of body weight. After this, the diaphragm muscle (DIA) was removed, and blood samples were collected by cardiac puncture (Fig. 3S in the Supplementary Information).

Blood creatine kinase dosage

The serum obtained from the cardiac puncture of the animals was used to determine the creatine kinase (CK) activity using the Bioclin CK Nac Kinetic Crystal kit. Sample absorbances were read at 25°C using the Multi-Mode Microplate Reader Model Synergy H1M (Bio-Tek Instruments) with a wavelength of 340nm.

Histopathological analysis

The previously collected DIA muscles were kept at −25°C in the cryostat (Leica CM1860-UV) to obtain cryosection slides for the following analysis: hematoxylin and Eosin (HE), incubation with F4/80 antibody, anti-mouse IgG-FITC, incubation with dihydroethidium and lipofuscin granule count. The sections were analyzed under an optical light and/or fluorescence microscope (Nikon) connected to a video camera (Nikon) in a 20× objective, using the NIS-elements AR Advances Research software and quantified using the Image-Pro Express software (Media Cybernetic, Silver Spring, MD, USA). Results were presented as mean ± SD.

Degenerated muscle fibers

Cryosection slides were incubated with anti-mouse IgG conjugated to fluorescein for detection of degenerating fibers. The number of fibers internally stained with the antibody was counted and expressed as a percentage of the total number of fibers. To stain the necrotic fibers, the sections were fixed with acetone, washed in TBS-T 3× for 5 min, and blocked with 3% BSA for 1 h. Afterwards, they were incubated with FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody (Sigma) for 1 h. After washing, slides were mounted in DABCO (Sigma).

Regenerated muscle fibers

The slides stained with HE were observed under a light microscope to evaluate the number of fibers that presented a central nucleus—which is indication of regenerated muscle fibers (Torres and Duchen 1987), and/or fibers with a peripheral nucleus (characteristic of normal fibers). Non-overlapping images of the entire cross section were taken and tiled together using the NIS-elements AR Advances Research software (Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, NY, USA) as described previously (Mâncio et al. 2017). All fibers (normal and regenerated) were counted to estimate the total population in each muscle, allowing to obtain the percentage of normal and regenerated fibers of the animals used in the experiment.

Inflammatory area

Inflammatory areas were characterized by HE stained slides of the DIA muscle based on the nucleus morphology and cell size and analyzed as described previously (Hermes et al. 2019; Silva et al. 2021). Areas of inflammation and total muscle area were outlined as a percentage of the total area.

Minimum diameter of Feret

The minimum distance of parallel tangents at the opposite edges of the muscle fiber (Briguet et al. 2004) was analyzed by quantifying a total of one hundred muscle fiber diameters from 10 random fields at 20× magnification, as described previously (Hermes et al. 2019; Silva et al. 2021).

Macrophage infiltration

In order to detect macrophages, slides were incubated with F4/80 and the areas were counted, in μm2, containing the antibody stain. Cryosections were fixed in 9% formalin for 20 s, washed with 0.1M TBS-T 3× for 5 min, and blocked with 3% BSA diluted in TBS-T for 1 h. The sections were washed and incubated for 30 min with anti-F4/80 (AbD Serotec), 1:200, overnight, at 4°C. Slides were washed in TBS-T 0.1M 3× for 5 min and incubated with Texas Red-conjugated anti-rat secondary antibody (1:250; Vector Laboratories) for 1 h at room temperature. The sections were washed in TBS-T 0.1 M 3× for 5 min and the DABCO slides were mounted (Sigma).

ROS detection (superoxide anion radical - O2•−)

The production of ROS, specifically O2•− anion radical, was determined by incubating the histological sections with 5μl of DHE in PBS at 37°C for 30 min. The intensity of reactive DHE per section area was quantified by measuring pixels exceeding a threshold (70–255nm), which was adjusted to eliminate interference from any background fluorescence (Whitehead et al. 2008).

Lipofuscin count

Since lipofuscin is autofluorescent, cryosections of the DIA muscle were mounted directly in a DABCO mounting medium (Sigma) for fluorescence under a coverslip. The total number of lipofuscin granules was determined in relation to the total area of the cut by their thickness (number of lipofucin/μm3).

Western blotting

DIA muscles were removed and cut into small pieces and immediately homogenized in 2ml of buffer for homogenization (Triton X-100 1%, Tris-HCl 100mM (pH 7.4), sodium pyrophosphate 100mM, sodium fluoride 100mM, ETDA10mM, sodium orthovanadate 10mM, PMSF 2mM and aprotinin 0.1mg/ml) at 4°C using a Polytron PTA 20S homogenizer (model PT 10/35; Kinematica Ag) operated at full speed for 30 s. The technique used here is identical to the protocol described in the “Western blotting” section.

Dosage of sulfhydryl groups

The samples (obtained in the same way as the samples used for Western Blotting) were centrifuged (12,000rpm, at 4°C, for 15 min) and the supernatant diluted (1:10) in a sodium phosphate buffer (0.1M pH=7.4). The technique used here is identical to the protocol described in the “Dosage of sulfhydryl group” section.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Comparisons of multiple groups were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison’s test. For comparisons of two groups, the Kolmogorov and Smirnov tests were used to assess the normality of the data, and then the unpaired T test was used followed by the F test analysis to compare the treatment effects. A 5% (P≤0.05) significance level was used. The GraphPad Prims5 software package (GraphPad Software, CA, USA) was used.

Results

Indigo effects on cell viability and cell proliferation

In in vitro studies to assess the dose-dependent toxicities of indigo on dystrophic muscle cells, we used the MTT and Neutral Red assays. No significant differences were found in cell proliferation, evaluated by MTT assay, between the experimental groups (Fig. 1a). Through the analysis of Neutral Red assay (Fig. 1b), a significant increase in viability in mdx muscle cells (untreated and treated mdx cells) was observed when compared to ctrl muscle cells (22.5% for mdx; 20.6% for prop; 43.9% for IND25; 33.1% for IND12.5; 36.1% for IND6.25 and 30.2% for IND3.12 groups). In addition, the treatment with 25μg/mL of indigo showed increased viability when compared to mdx and prop groups (21.5% and 23.3%, respectively). Cell viability evaluated by live/dead showed no significant difference between the primary muscle cells from experimental mdx and mdxIND (25μg/mL indigo) groups (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

Indigo effects on cell viability and proliferation cell. In vitro studies: proliferation cell was assessed by MTT assay (a) and cell viability by Neutral Red assay (b) in the C57BL/10 muscle cells (ctrl); untreated mdx muscle cells (mdx); mdx muscle cells in the presence of propylene vehicle (prop); mdx muscle cells treated with 25.00μg/mL of indigo (IND25); mdx muscle cells treated with 12.50μg/ml of indigo (IND12.5); mdx muscle cells treated treatment with 12.50μg/ml of indigo (IND12.5); mdx muscle cells treated with 6.25μg/ml of indigo (IND6.25); and mdx muscle cells treated with 3.12μg/ml indigo (IND3.12). c Fluorescent images of the incorporation of the Live/dead reagent kit in untreated mdx muscle cells (mdx) and in mdx muscle cells treated with 25.00μg/mL of indigo (IND25). Live cells in green. Dead cells in red. Scale bar 100 μm, 20×. All experiments were performed in triplicate, analyzed after 24 h and data expressed as mean ± SD. Differs from the ctrl group: *p≤0.05; **p≤0.001; ***p≤0.0005; and ****p≤0.00001. Differs from the mdx group: #p≤0.05. Differs from the prop group: °°p≤0.001 (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test).

Indigo effects on body weight and degeneration/regeneration muscular process

In in vivo studies, there was no statistical difference in the body weight of the animals in the mdx and mdxIND groups, during the trial period (Table 1).

Table 1.

Body weights and creatine kinase (CK) levels

| Body weight (g) | Creatine kinase levels | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14th day | 28th day | (%) | (U/L) | |

| mdx | 6.18 ± 1.89 | 9.10 ± 2.79 | 47.24 | 4.84 ± 1.71 |

| mdxIND | 6.69 ± 1.86 | 10.05 ± 4.12 | 49.99 | 2.69 ± 0.52** |

Body weight (g) was measured at the beginning (start) and after 14 days (end) of indigo treatment. Creatine kinase levels were measured at the end of the experiment. All values are shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD). **P≤0.001 compared with the mdx group (unpaired T test followed by the F test analysis).

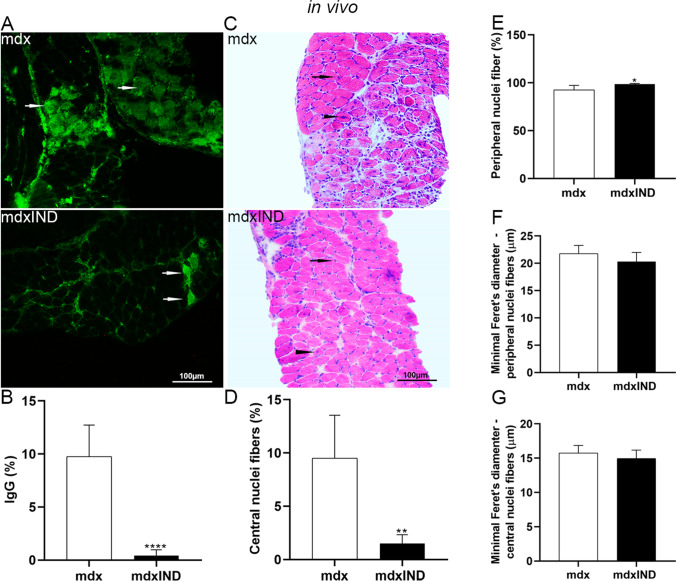

Biochemical evaluation of muscular degeneration, based on CK levels, showed a significant reduction of CK levels in the mdxIND group (by 44.3%) when compared to the mdx group (Table 1). A significant reduction (by 96.2%) in the muscular degeneration process was also observed, by morphological analysis, in the DIA muscles of the mdxIND group (Fig. 2A, B).

Fig. 2.

Indigo effects on degeneration/regeneration muscular process in mdx diaphragm muscle. In vivo studies: A Cross sections of diaphragm (DIA) muscle showing IgG staining (white arrow) in untreated mdx mice (mdx) and mdx mice treated with 3mg/kg of indigo (mdxIND). B The graph shows the IgG staining (%) in the DIA muscle in mdx and mdxIND groups. C Cross sections of DIA muscle showing fibers which central nuclei (black arrowhead) and fibers with a peripheral nucleus (black arrow) in mdx and mdxIND groups. The graphs show the percentage of fibers with central nuclei fibers (D) and fibers with peripheral nuclei (E) in the DIA muscle of mdx and mdxIND groups. The graphs show the minimal Feret’s diameter (μm) of fibers with central nuclei fibers (F) and fibers with peripheral nuclei (G) in the DIA muscle of mdx and mdxIND groups. Scale bar 100 μm, 20×. Differs from the mdx group: **p≤0.001 and ****p≤0.00001 ((Kolmogorov and Smirnov and unpaired T test, post F test)

Regarding the regenerative muscular process, morphologically evaluated by fibers with central nuclei, a significant reduction (79.5%) in the percentage of the number of fibers with central nuclei was observed in the mdxIND group when compared to the mdx group (Fig. 2C, D). At the same time, a significant increase in the percentage of the number of fibers with peripheral nuclei (by 6.3%) was observed in the mdxIND group when compared to the mdx group (Fig. 2C, E). Feret’s diameter analyses showed no statistical difference in the diameter of the fibers with central and peripheral nuclei between the experimental groups (Fig. 2F, G).

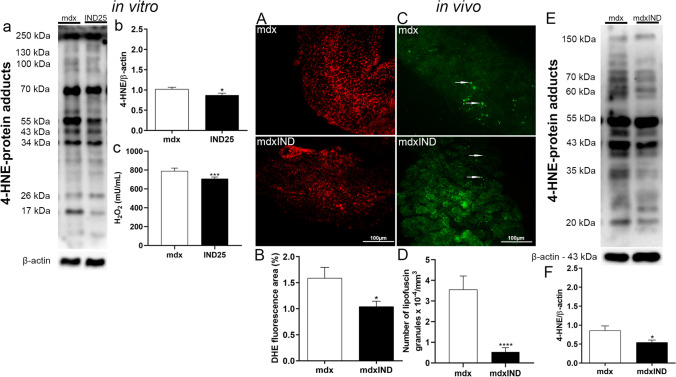

Indigo effects on oxidative stress

In in vitro studies, to evaluate the antioxidant effect of indigo in dystrophic cell cultures, the H2O2 content and the 4-HNE levels were analyzed. As seen in Fig. 3a, it is possible to observe immunoreactive bands for proteins affected by lipid peroxidation, where 4-HNE levels were significantly lower in the treated group (by 15.5%) when compared to the mdx group (Fig. 3b). In addition, muscle cells treated with 25μg/mL of indigo showed a reduction in H2O2 production (by 9.3%) when compared to the mdx group (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

Indigo effects on oxidative stress. In vitro studies: a Western Blotting analysis of 4-HNE-labeled protein adducts in untreated mdx muscle cells (mdx) and mdx muscle cells treated with 25.00μg/mL of indigo (IND25). b The graph shows the 4-HNE protein adducts levels in mdx and IND25 groups. β-actin was used as an internal control. The relative value of the band intensity was quantified and normalized by the corresponding control. c The graph shows the H2O2 production in mdx and IND25 groups. In vivo studies: A Cross sections of diaphragm (DIA) muscle showing dihydroethidium (DHE) fluorescence in untreated mdx mice (mdx) and mdx mice treated with 3mg/kg of indigo (mdxIND). B The graph shows the DHE staining area (%) in the DIA muscle in mdx and mdxIND groups. C Cross sections of DIA muscle showing autofluorescent lipofuscin granules (white arrow) in mdx and mdxIND groups. D The graph shows the number of lipofuscin granules × 10−4/μm3 in the DIA muscle of mdx and mdxIND groups. Scale bar 100 μm, 20×. E Western Blotting analysis of 4-HNE-labeled protein adducts in the DIA muscle of mdx and mdxIND groups. F The graph shows the 4-HNE protein adducts levels in mdx and mdxIND groups. β-actin was used as an internal control. The relative value of the band intensity was quantified and normalized by the corresponding control. Differs from the mdx group: *p≤0.05, ***p≤ 0.0001, and ****p≤0.00001 (Kolmogorov and Smirnov and unpaired T test, post F test)

In in vivo studies, to evaluate the antioxidant effect of indigo in dystrophic DIA muscle, the DHE fluorescence area, the number of autofluorescent lipofuscin granules, and the 4-HNE levels were analyzed. The mdx indigo-treated group showed a reduction of oxidative stress markers by significantly decreasing the DHE area (39.1%), the autofluorescent lipofuscin granules (80.8%), and the 4-HNE protein adduct levels (14.2%), in the DIA muscle (Fig. 3A–F).

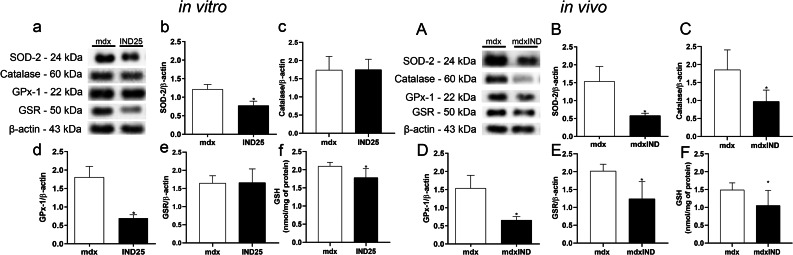

Indigo effects on antioxidant defense system

In in vitro studies, a significant reduction in the levels of SOD-2, GPX-1, and GSH in the treated group (by 36.6%, 61.4%, and 15.1%, respectively) was observed when compared to the mdx group (Fig. 4a, b, d, f). No significant differences were found in catalase and GSR levels between the experimental groups (Fig. 4a, c, e).

Fig. 4.

Indigo effects on antioxidant defense system. In vitro studies: a Western Blotting analysis of SOD-2, CAT, GPx-1, and GSR in untreated mdx muscle cells (mdx) and mdx muscle cells treated with 25.00μg/mL of indigo (IND25). The graphs show the SOD2 (b); CAT (c); GPx1 (d); and GSR (e) levels in mdx and IND25 groups. β-actin was used as an internal control. The relative value of the band intensity was quantified and normalized by the corresponding control. f Analysis of GSH content by sulfhydryl groups assay in mdx and IND25 groups. In vivo studies: A Western blotting analysis of SOD-2, CAT, GPx-1, and GSR in untreated mdx mice (mdx) and mdx mice treated with 3mg/kg of indigo (mdxIND). The graphs show the SOD2 (B); CAT (C); GPx1 (D); and GSR (E) levels in mdx and mdxIND groups. β-actin was used as an internal control. The relative value of the band intensity was quantified and normalized by the corresponding control. F Analysis of GSH content by sulfhydryl groups assay in mdx and mdxIND groups. Differs from the mdx group: *p≤ 0.05 (Kolmogorov and Smirnov and unpaired T test, post F test)

In in vivo studies, regarding the indigo effect on the antioxidant defense system in the dystrophic DIA muscle, a significant reduction in the SOD-2 (by 62.1%), CAT (by 42.3%), GPX-1 (by 57.1%), GSR (by 38.6%), and GSH (by29.3%) levels was observed in the mdxIND group when compared to the mdx group (Fig. 4A–F).

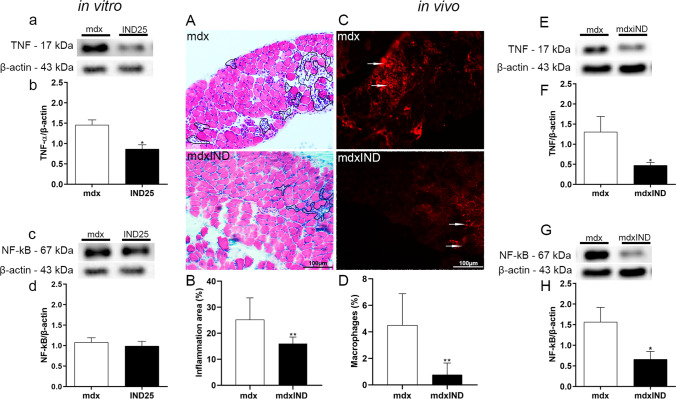

Indigo effects on inflammatory process

In in vitro studies, the effects of indigo on the inflammatory process in dystrophic muscle cells were analyzed by TNF and NF-κB levels (Fig. 5a–d). A reduction of 40.8% on TNF levels was observed in the IND25 group when compared to the mdx group (Fig. 5a, b). No significant differences were found in NF-κB levels between the experimental groups (Fig. 5c, d).

Fig. 5.

Indigo effects on inflammatory process. In vitro studies: a Western Blotting analysis of TNF and NF-κB in untreated mdx muscle cells (mdx) and mdx muscle cells treated with 25μg/mL of indigo (IND25). The graphs show the TNF (b) and NF-κB (c) levels in mdx and IND25 groups. β-actin was used as an internal control. The relative value of the band intensity was quantified and normalized by the corresponding control. In vivo studies: A The outline in cross sections of diaphragm (DIA) muscle indicates the representative area of inflammation in untreated mdx mice (mdx) and mdx mice treated with 3mg/kg of indigo (mdxIND). B The graph shows the inflammatory area (%) in the DIA muscle in mdx and mdxIND groups. C Macrophage infiltration (white arrows) was determined by F4/80 immunohistochemistry in cross sections of DIA muscle in mdx and mdxIND groups. D The graph shows the macrophage infiltration area (%) in the DIA muscle of mdx and mdxIND groups. Scale bar 100 μm, 20×. E, F Western blotting analysis of TNF and NF-κB in untreated mdx mice (mdx) and mdx mice treated with 3mg/kg of indigo (mdxIND). The graphs show the TNF (G) and NF-κB (H) levels in mdx and mdxIND groups. β-actin was used as an internal control. The relative value of the band intensity was quantified and normalized by the corresponding control. Differs from the mdx group: *p≤0.05 and **p≤0.001 (Kolmogorov and Smirnov and unpaired T test, post F test)

In in vivo studies, morphological analyses of the anti-inflammatory effect of indigo on the dystrophic DIA muscle showed a significant decrease in inflammatory area (by 36.5%) and macrophage infiltration area (by 87.2%) in the mdxIND group when compared to the mdx group (Fig. 5A–D). In addition, a significant decrease in TNF and NF-κB levels (by 63.6% and 57.9%, respectively) was observed, by Western blotting, in the dystrophic DIA muscle of the mdxIND group when compared to the mdx group (Fig. 5E–H).

Indigo effects on factors involved in mitochondrial biogenesis

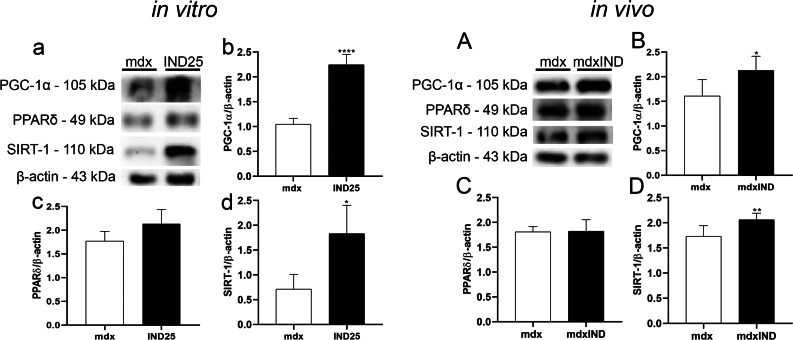

In in vitro studies, the effects of indigo on factors involved in mitochondrial biogenesis in dystrophic muscle cells were analyzed by PGC-1α, PPARδ, and SIRT-1 levels (Fig. 6a–d). A significant increase was observed in the PGC-1α and SIRT-1 levels in the IND25 group (by 95.3% and 200.3%, respectively) when compared to the mdx group (Fig. 6a, b, d). No significant differences were found in the PPARδ levels between the experimental groups (Fig. 6a, c).

Fig. 6.

Indigo effects on factors involved in mitochondrial biogenesis. In vitro studies: a Western blotting analysis of PGC-1α, PPARδ, and SIRT-1 in untreated mdx muscle cells (mdx) and mdx muscle cells treated with 25μg/mL of indigo (IND25). The graphs show the PGC-1α (b); PPARδ (c); and SIRT-1 (d) levels in mdx and IND25 groups. β-actin was used as an internal control. The relative value of the band intensity was quantified and normalized by the corresponding control. In vivo studies: AWestern blotting analysis of PGC-1α, PPARδ, and SIRT-1 in untreated mdx mice (mdx) and mdx mice treated with 3mg/kg of indigo (mdxIND). The graphs show the PGC-1α (B); PPARδ (C); and SIRT-1 (D) levels in mdx and mdxIND groups. β-actin was used as an internal control. The relative value of the band intensity was quantified and normalized by the corresponding control. Differs from the mdx group: *p≤0.05, **p≤0.001, and ****p≤0.00001 (Kolmogorov and Smirnov and unpaired T test, post F test)

In in vivo studies, a significant increase was observed in the levels of PGC-1α and SIRT-1 in the mdxIND group (by 32.3% and 19%, respectively) when compared to the mdx group (Fig. 6A, B, D). There was no statistical difference in the PPARδ levels in the mdx and mdxIND groups (Fig. 6A, C).

Discussion

Natural products and their derivatives remain an important source of therapeutic agents and structural diversity (Suntar et al. 2020). In this respect, it has been reported that the alkaloids exhibit beneficial effects by inhibiting oxidative stress via reducing lipid peroxidation products; decreasing ROS production; increasing the levels of non-enzymatic antioxidants, such as GSH; and enhancing different enzyme antioxidant activities (Rabelo Socca et al. 2014). In the present study, the alkaloid indigo showed promising beneficial effects, in vitro and in vivo, against dystrophic pathophysiological events.

The first experiment consisted of evaluating the dose-dependent toxicities of indigo in the dystrophic muscle cells, using the MTT and Neutral Red assays. The results revealed that the indigo treatment was not toxic to the mdx muscle cells at the concentrations used (3.12, 6.25, 12.50, and 25.00 μg/mL). Lin et al. (2009) also showed that 10μM indigo does not have toxic effects on human neutrophils. Also, indigo treatment at 25, 50, 100, and 200 μM concentrations has been shown to have no cytotoxicity in the hepatocyte cell culture (Ozawa et al. 2020). In addition, a significant increase in cell viability was observed after treatment with 25μg/ml indigo under our experimental conditions, leading to the choice of this dose for subsequent in vitro experiments. Regarding in vivo studies, the indigo dose was based on a previous study, which showed that indigo has no toxic effect on 1, 3, and 6mg/kg concentrations in the gastric mucosa experimental model (Farias-Silva et al. 2007).

Antioxidant activity is one of the main properties related to indigo (Farias-Silva et al. 2007) and we observed its antioxidant effect on dystrophic muscle cells and the diaphragm muscle of mdx mice. According to some authors, oxidative stress is strongly implicated in DMD pathogenesis, where the major cellular consequence of oxidant exposure is damage to proteins and lipids. (Terrill et al. 2013; Grounds et al. 2020). Previous studies showed high levels of lipidic peroxidation by 4-HNE protein adduct analysis in the dystrophic muscles of mdx mice (Silva et al. 2021; Hermes et al. 2020; Mizobuti et al. 2019). The indigo treatment was able to reduce the 4-HNE levels in the dystrophic muscle cells and diaphragm muscle. In addition, we also observed that other oxidative stress markers, such as H2O2 levels, DHE reaction, and lipofuscin granules, were significantly reduced after indigo treatment. Farias-Silva et al. (2007) correlated the indigo gastroprotective mechanism to the increase of GSH levels and to a reduction of polymorphonuclear neutrophil tissue infiltration. In the present study, differing from Farias’ work, we observed a reduction in GSH levels after indigo treatment, with a concomitant reduction also in the levels of antioxidant enzymes. Based on research that substantiates the ability of some alkaloids to act as a potent-free radical-scavenger and an antioxidant molecule, reacting with high efficiency towards a broad scope of reactive species to either prevent or retard the targeted oxidation of lipids; proteins; and nucleic acids (O’Brien et al. 2006); it is possible that indigo, under our experimental conditions, can act by directly scavenging excessive ROS. This indigo property is probably related to the indole moiety present in its structure. Research showed structural compounds with an indole moiety as a class of radical scavengers and antioxidants (Herraiz and Galisteo 2004). However, further investigations are necessary to confirm this hypothesis.

Another hypothesis is that the antioxidant effect of indigo may be related to the attenuation of the inflammatory process since oxidative stress and inflammation are closely linked in the dystrophic disease (reviewed by Grounds et al. 2020). In this respect, we observed a significant decrease in the inflammatory process identified by a reduction in TNF and NF-κB levels, in the inflammatory area; and in the macrophage infiltration, in our dystrophic sample, after indigo treatment. NF-κB is an important inflammatory regulator, modulating the transcription and expression of TNF, IL-1β, IL-6, and other inflammatory mediators (Tidball et al. 2018). NF-κB-induced inflammatory factors could further sustain and activate NF-κB which aggravates the inflammatory injury (Tidball et al. 2018). In addition, a decrease in the TNF levels in the dystrophic muscle is of particular interest, as TNF exacerbates myonecrosis and studies show that reducing the levels of TNF, using several strategies, effectively prevents myonecrosis (Hodgetts et al. 2006; Silva et al. 2021). Our findings collaborate with these studies, since concomitantly with the TNF level reduction, we also biochemically (by CK levels) and morphologically (by the reduction of IgG positive fibers and fibers with central nuclei; and by the increase of fibers with peripheral nuclei) verified a decrease in the degeneration muscular process in the dystrophic diaphragm muscle. Regarding the anti-inflammatory effects of indigo, a recent study (Yang et al. 2021), exploring the indigo mechanism in the treatment of ulcerative colitis showed that this alkaloid reduced the expression of NF-κB and inhibited the activation of TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway, reducing the TNF, IL-1β, and IL-6 levels.

Another point evaluated in the present study deals with the signaling pathway between the inflammatory process, the oxidative stress, and the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α (PGC-1α). PGC-1α is a master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis and regulates mitochondrial function in several tissues, such as those from the brain, heart, skeletal muscle, and liver (Handschin and Spiegelman 2006). PGC-1a activation is regulated by PPARs (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor), 5′ adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK), and silent mating type information regulation 2 homolog 1 (SIRT1) (Cantó and Auwerx 2009). Previous studies have shown the beneficial effects of PGC-1α upregulation in mdx mice, indicating that PGC-1α is linked to the anti-inflammatory and the antioxidant response (Suntar et al. 2020; Rommel et al. 2001; Kim et al. 2011). Low PGC-1α levels in the skeletal muscle were associated with inflammatory processes and the display of circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines (Tonon et al. 2012), while high PGC-1α levels were accompanied by lower TNF and interleukin 6 (IL-6) mRNA expressions in the skeletal muscle (Radley-Crabb et al. 2012). Recently, our research group also reported the correlation between elevated PGC-1α levels and a reduction in the TNF and NF-κB levels in the dystrophic muscle treated with antioxidant Tempol (Silva et al. 2021). In addition, the over PGC-1α levels were also linked to oxidative stress reduction (Silva et al. 2021).

Several studies have focused on the PGC-1α-activating effects of natural products derived from medicinal plants (for review Suntar et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2014). For instance, it has been reported that nutraceuticals, such as resveratrol, protect against oxidative stress and improve mitochondrial function by activating SIRT1 and PGC-1α in mouse models of neurodegenerative disease (Ljubicic et al. 2014). In addition, polyphenols, resveratrol, and epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) have demonstrated a reversion of mitochondrial dysfunction and a reduction of oxidative stress in a Down syndrome model cell, by acting through the PGC-1α/SIRT1/AMPK axis (Valenti et al. 2016). Quercetin was also found to activate SIRT1 and then PGC-1α, stimulating mitochondrial biogenesis and decreasing muscle injury in the skeletal muscles of mdx mice (Hollinger et al. 2015). Interestingly, in the present study, we also observed a PGC-1α and SIRT1 modulation (upregulation) in the dystrophic muscle cells treated with indigo, suggesting that the SIRT1/PGC-1α pathway may be one of the mechanisms by which indigo showed antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects in the dystrophic muscle.

As stated above, there is a close connection (Fig. 1S in the Supplementary Information) between inflammation, oxidative stress, and the factor regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis and function (PGC-1α); thus, the effect of natural products, such as alkaloids, on these signaling pathways is of interest.

Conclusion

The data shown here highlight the potential of indigo as a therapeutic agent for DMD through its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant action and by its modulation of the SIRT1/PGC-1α pathway. However, further investigations are required to determine the mechanism by which indigo acts on the SIRT1/PGC-1α pathway.

Supplementary information

Targets of indigo treatment in mdx muscle cells and diaphragm muscle. Indigo up-regulated; Indigo down-regulated. (PNG 51 kb)

Indigo chemical structure and experimental design of indigo treatment in vitro, groups and analyses. (PNG 29 kb)

Experimental design of indigo treatment in vivo, groups and analyses. (PNG 17 kb)

Author contribution

E.M. and M.J.S. conceived and designed the experiments. E.M. coordinated the research. D.S.M. performed the experiments and G.L.R., H.N.M.S., C.C., C.C.L., and E.C.L.P. assisted with the experiments. E.M., D.S.M, and M.J.S. participated in drafting the article. All authors read and approved of the version to be submitted.

Funding

The authors received financial support from the Coordenação de Pessoal de Nivel Superior Brasil (CAPES) – Finance Code 001, the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP, process: 15/03726-8; 13/17732-4; 20/09733-4; 21/09693-5), the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq; process #311166/2016-4; 427859/2018-2) and the FAEPEX. D.S.M, G.L.R. and C.C.L were the recipients of a CAPES fellowship. C.C. was the recipient of a CNPq fellowship. H.N.M.S. and M.J.S. are the recipient of a CNPq fellowship.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Andreazza NL, de Lourenço CC, Stefanello MÉA. Salvador, MJ (2015) Photodynamic antimicrobial effects of bis-indole alkaloid indigo from Indigofera truxillensis Kunth (Leguminosae) Lasers Med Sci. 2015;30:1315–1324. doi: 10.1007/s10103-015-1735-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borenfreund E, Puerner JA. Toxicity determined in vitro by morphological alterations and neutral red absorption. Toxicol Lett. 1985;24:119–124. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(85)90046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briguet I, Courdier-Fruh I, Foster M, Meier T, Magyar JP. Histological parameters for the quantitative assessment of muscular dystrophy in the mdx-mouse. Neuromuscul Disord. 2004;10:675–682. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantó C, Auwerx J. PGC-1alpha, SIRT1 and AMPK, an energy sensing network that controls energy expenditure. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2009;20:98–95. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e328328d0a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang HN, Pang JH, Yang SH, Hung CF, Chiang CH, Lin TY, Lin YK (2010) Inhibitory effect of indigo naturalis on tumor necrosis factor-α-induced vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 expression in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Molecules 15(9):6423–35. 10.3390/molecules15096423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Crisafulli S, Sultana J, Fontana A, Salvo F, Messina S, Trifirò G. Global epidemiology of Duchenne muscular dystrophy: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2020;15:1–20. doi: 10.1186/s13023-020-01430-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Almeida AC, De Faria FM, Dunder RJ, Manzo L, Socca EA, Souza-Brito AR, Luiz-Ferreira A. P057-intestinal anti-inflammatory activity of indigo alkaloid in TNBS-induced colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:S15. doi: 10.14309/01.ajg.0000613196.79305.a3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Emery AEH. The muscular dystrophies. Lancet. 2002;359:687–695. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07815-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farias-Silva E, Cola M, Calvo TR, Barbastefano V, Ferreira AL, De Paula Michelatto D, Alves de Almeida AC, Hiruma-Lima CA, Vilegas W, Brito AR (2007) Antioxidative activity of indigo and its preventive effects against ethanol-induced DNA damage in rat gastric mucosa. Planta Med 73:1241–1246. 10.1055/s-2007-981613 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Faure P, Lafond JL. Measurement of plasma sulfhydryl and carbonyl groups as a possible indicator of protein oxidation. In: Favier AE, Cadet J, Kalyanaraman B, Fontecave M, Pierre JL, editors. Analysis of Free Radicals in Biological Systems. Basel: Birkhäuser; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gloss D, Moxley RT, 3rd, Ashwal S, Oskoui M. Practice guideline update summary: corticosteroid treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy: Report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2016;86:465–472. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Grounds MD, Terrill JR, Al-Mshhdani BA, Duong MN, Radley-Crabb HG, Arthur PG. Biomarkers for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: myonecrosis, inflammation and oxidative stress. Dis Model Mech. 2020;13:dmm043638. doi: 10.1242/dmm.043638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handschin C, Spiegelman BM. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 coactivators, energy homeostasis, and metabolism. Endocr Rev. 2006;27:728–735. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermes TA, Mâncio RD, Macedo AB, Mizobuti DS, Rocha GL, Cagnon VHA, et al. Tempol treatment shows phenotype improvement in MDX mice. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0215590. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0215590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermes TA, Mizobuti DS, da Rocha GL, da Silva HNM, Covatti C, Pereira ECL, et al. Tempol improves redox status in MDX dystrophic diaphragm muscle. Int J Exp Pathol. 2020;101:289–297. doi: 10.1111/iep.12376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herraiz T, Galisteo J. Endogenous and dietary indoles: a class of antioxidants and radical scavengers in the ABTS assay. Free Radic Res. 2004;38:323–331. doi: 10.1080/10611860310001648167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrendorff R, Faleschini MT, Stiefvater A, Erne B, Wiktorowicz T, Kern F, et al. Identification of plant-derived alkaloids with therapeutic potential for myotonic dystrophy type I. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:17165–17177. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.710616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgetts S, Radley H, Davies M, Grounds MD. Reduced necrosis of dystrophic muscle by depletion of host neutrophils, or blocking TNF alpha function with Etanercept in mdx mice. Neuromuscul Disord. 2006;16:591–602. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollinger K, Shanely RA, Quindry JC, Selsby JT. Long-term quercetin dietary enrichment decreases muscle injury in mdx mice. Clin Nutr. 2015;34:515–522. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MH, Kay DI, Rudra RT, Chen BM, Hsu N, Izumiya Y, et al. Myogenic Akt signaling attenuates muscular degeneration, promotes myofiber regeneration and improves muscle function in dystrophin-deficient mdx mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:1324–1338. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landfeldt E, Edström J, Buccella F, Kirschner J, Lochmüller H. Duchenne muscular dystrophy and caregiver burden: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2018;60:987–996. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.13934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin YK, Leu YL, Huang TH, Wu YH, Chung PJ, Su Pang JH, Hwang TL. Anti-inflammatory effects of the extract of indigo naturalis in human neutrophils. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;125:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ljubicic V, Burt M, Lunde JA, Jasmin BJ. Resveratrol induces expression of the slow, oxidative phenotype in mdx mouse muscle together with enhanced activity of the SIRT1-PGC-1α axis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2014;307:66–82. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00357.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macedo AB, Moraes LHR, Mizobuti DS, Fogaca AR, Moraes FDSR, Hermes TA, et al. Low-level laser therapy (LLLT) in dystrophin-deficient muscle cells: effects on regeneration capacity, inflammation response and oxidative stress. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0128567. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mâncio RD, Hermes TA, Macedo AB, Mizobuti DS, Rupcic IF, Minatel E. Dystrophic phenotype improvement in the diaphragm muscle of mdx mice by diacerhein. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0182449. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maugard T, Enaud E, Choisy P, Legoy MD. Identification of an indigo precursor from leaves of Isatis tinctoria (Woad) Phytochemistry. 2001;58:897–904. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(01)00335-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizobuti DS, Fogaça AR, Moraes FDSR, Moraes LHR, Mâncio RD, Hermes TA, et al. Coenzyme Q10 supplementation acts as antioxidant on dystrophic muscle cells. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2019;24:1175–1185. doi: 10.1007/s12192-019-01039-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira R, Pereira DM, Valentão P, Andrade PB. pyrrolizidine alkaloids: chemistry, pharmacology, toxicology and food safety. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:1668. doi: 10.3390/ijms19061668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moxley RT 3rd, Pandya S, Ciafaloni E, Fox DJ, Campbell K (2010) Change in Natural History of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy With Long-term Corticosteroid Treatment: Implications for Management. J Child Neurol 25(9):1116–1129. 10.1177/0883073810371004 [DOI] [PubMed]

- O’Brien P, Carrasco-Pozo C, Speisky H. Boldine and its antioxidant or health-promoting properties. Chem Biol Interact. 2006;159:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozawa DM, Ayumu H, Toshinori S, Jin N, Yukinobu I, Mikio N, et al. Comparison of the anti-colitis activities of Qing Dai/Indigo Naturalis constituents in mice. J Pharmacol Sci. 2020;142:148–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jphs.2020.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabelo Socca EA, Luiz-Ferreira A, de Faria FM, de Almeida AC, Dunder RJ, Manzo LP, et al. Inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and cyclooxigenase-2 by Isatin: a molecular mechanism of protection against TNBS-induced colitis in rats. Chem Biol Interact. 2014;209:48–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2013.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radley-Crabb H, Terrill J, Shavlakadze T, Tonkin J, Arthur P, Grounds MD. A single 30min treadmill exercise session is suitable for ‘proof-of concept studies’ in adult MDX mice: a comparison of the early consequences of two different treadmill protocols. Neuromuscul Disord. 2012;22:170–182. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rando TA, Blau HM. Primary mouse myoblast purification, characterization, and transplantation for cell-mediated gene therapy. J Cell Biol. 1994;125:1275–1287. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.6.1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rommel C, Bodine SC, Clarke BA, Rossman R, Nunez L, Stitt TN, et al. Mediation of IGF-1-induced skeletal myotube hypertrophy by PI(3)K/Akt/mTOR and PI(3)K/Akt/GSK3 pathways. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:1009–1013. doi: 10.1038/ncb1101-1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva HNM, Covatti C, Da Rocha GL, Mizobuti DS, Mâncio RD, Hermes TA, et al. Oxidative stress, inflammation, and activators of mitochondrial biogenesis: tempol targets in the diaphragm muscle of exercise trained-mdx mice. Front Physiol. 2021;12:e649793. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2021.649793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suntar I, Sureda A, Belwal T, Sanches Silva A, Vacca RA, Tewari D, et al. Natural products, PGC-1 α, and Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020;10:734–745. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taha HS, El-Bahr MK, Seif-El-Nasr MM. In vitro studies on Egyptian Catharanthus roseus (L.). Ii. Effect of biotic and abiotic stress on indole alkaloids production. J Appl Sci Res. 2009;5:1826–1831. [Google Scholar]

- Terrill JR, Radley-Crabb HG, Iwasaki T, Lemckert FA, Arthur PG, Grounds MD. Oxidative stress and pathology in muscular dystrophies: focus on protein thiol oxidation and dysferlinopathies. FEBS J. 2013;180:4149–4164. doi: 10.1111/febs.12142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tidball JG, Welc S, Wehling-Henricks M. Immunobiology of Inherited Muscular Dystrophies. Compr Physiol. 2018;4:1313–1356. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c170052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonon E, Ferretti R, Shiratori JH, Neto HS, Marques MJ, Minatel E. Ascorbic acid protects the diaphragm muscle against myonecrosis in MDX mice. Nutrition. 2012;28:686–690. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres LF, Duchen LW. The mutant mdx: inherited myopathy in the mouse. Morphological studies of nerves, muscles and end-plates. Brain. 1987;110:269–299. doi: 10.1093/brain/110.2.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenti D, de Bari L, de Rasmo D, Signorile A, Henrion-Caude A, Contestabile A. The polyphenols resveratrol and epigallocatechin-3-gallate restore the severe impairment of mitochondria in hippocampal progenitor cells from a Down syndrome mouse model. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1862:1093–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.03.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaart IEC, Aartsma-Rus A. Therapeutic developments for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15:373–386. doi: 10.1038/s41582-019-0203-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Waltenberger B, Pferschy-Wenzig EM, Blunder M, Liu X, Malainer C, Blazevic T, Schwaiger S, Rollinger JM, Heiss EH, Schuster D, Kopp B, Bauer R, Stuppner H, Dirsch VM, Atanasov AG (2014) Natural product agonists of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ): a review. Biochem Pharmacol 92(1):73–89. 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.07.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Whitehead NP, Yeung EW, Allen DG. Muscle damage in mdx (dystrophic) mice: role of calcium and reactive oxygen species. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2006;33:657–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2006.04394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead NP, Pham C, Gervasio OL, Allen DG. N-Acetylcysteine ameliorates skeletal muscle pathophysiology in mdx mice. J Physiol. 2008;586:2003–2014. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.148338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang QY, Ma LL, Zhang C, Lin JZ, Han L, He YN, et al. Exploring the mechanism of indigo naturalis in the treatment of ulcerative colitis based on TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway and gut microbiota. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:674416. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.674416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Targets of indigo treatment in mdx muscle cells and diaphragm muscle. Indigo up-regulated; Indigo down-regulated. (PNG 51 kb)

Indigo chemical structure and experimental design of indigo treatment in vitro, groups and analyses. (PNG 29 kb)

Experimental design of indigo treatment in vivo, groups and analyses. (PNG 17 kb)