Abstract

Vitamin K epoxide reductases (VKORs) are a large family of integral membrane enzymes found from bacteria to humans. Human VKOR, specific target of warfarin, has both the epoxide and quinone reductase activity to maintain the vitamin K cycle. Bacterial VKOR homologs, however, are insensitive to warfarin inhibition and are quinone reductases incapable of epoxide reduction. What affords the epoxide reductase activity in human VKOR remains unknown. Here, we show that a representative bacterial VKOR homolog can be converted to an epoxide reductase that is also inhibitable by warfarin. To generate this new activity, we first substituted several regions surrounding the active site of bacterial VKOR by those from human VKOR based on comparison of their crystal structures. Subsequent systematic substitutions narrowed down to merely eight residues, with the addition of a membrane anchor domain, that are responsible for the epoxide reductase activity. Substitutions corresponding to N80 and Y139 in human VKOR provide strong hydrogen bonding interactions to facilitate the epoxide reduction. The rest of six substitutions increase the size and change the shape of the substrate-binding pocket, and the membrane anchor domain stabilizes this pocket while allowing certain flexibility for optimal binding of the epoxide substrate. Overall, our study reveals the structural features of the epoxide reductase activity carried out by a subset of VKOR family in the membrane environment.

Keywords: Vitamin K epoxide reductase (VKOR), quinone reductase activity, vitamin K cycle, oxidoreductase, integral membrane enzyme

Graphical Abstract

VKORs are a family of integral membrane oxidoreductases found from bacteria to humans. Human VKOR reduces vitamin K epoxide to support blood coagulation, whereas bacterial homologs can only reduce quinones. Here, we convert a representative bacterial VKOR to epoxide reductase by merely changing eight residues (orange) and adding a membrane anchor domain found in human protein. These changes in local structure, not overall fold, determine the epoxide reductase activity.

Introduction

The VKOR family is constituted of a large number of integral membrane thiol oxidoreductases that are present in vertebrates, arthropods, plants, archaea and bacteria [1]. In humans, VKOR supports blood coagulation, bone mineralization and vascular calcium homeostasis through the vitamin K cycle [2, 3]. This cycle begins with the γ-carboxylation of coagulation factors and other vitamin K dependent proteins, a posttranslational modification required for their activities. Catalysis by the γ-carboxylase is driven by the epoxidation of vitamin K hydroquinone (KH2), which needs to be regenerated by VKOR located in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane. Human VKOR (HsVKOR) reduces vitamin K epoxide (KO) first to the quinone form (K), and then to the hydroquinone form (KH2). Each reduction step is coupled to the formation of a disulfide bond in HsVKOR, and the reducing equivalent is provided by small molecules or redox partner proteins in the ER [4–8]. In lower organisms, however, the primary function of VKOR homologs changes to catalyze the de novo generation of disulfide bond through reducing ubiquinones and menaquinones (such as vitamin K). Subsequently, these VKOR homologs exchange the disulfide bond with their redox partners, which in turn pass the disulfide bond to nascently synthesized proteins to support their oxidative folding [9–12].

Despite moderate sequence similarities, vertebrate VKORs and their bacterial homologs have different enzymatic activities and respond differently to warfarin, which targets human VKOR for anticoagulation[13]. Because vitamin K epoxide is a catalytic product of the γ-carboxylase that is not present in bacteria, most bacterial VKORs are not expected to carry the epoxide reductase activity. For instance, the VKOR homolog from Synechococcus sp. (SsVKOR) clearly lacks the epoxide reductase activity, but can reduce vitamin K quinone or ubiquinone to the corresponding hydroquinone [13]. This SsVKOR activity is inhibited by warfarin only at very high concentration (mM) [13]. Similarly, 1–10 mM warfarin is required to inhibit a VKOR homolog from Mycobacterium tuberculosis [14]. In contrast, warfarin hinders blood coagulation by effectively inhibiting (in nM range) both the epoxide and quinone reductase activities of HsVKOR [15, 16].

These key differences were taken as evidence that HsVKOR and its bacterial homologs adopt completely different structural folds [16–19]. In SsVKOR, the core structure that is homologous to HsVKOR is made of a four-transmembrane-helix bundle that forms the active site. In contrast, HsVKOR was previously proposed to contain three transmembrane helices, a controversial model with both supporting and opposing biochemical evidences [4, 18–22]. Our recent crystal structures of HsVKOR, however, clearly show that it is a four-TM protein as the bacterial homolog [23]. Nevertheless, what determines the different epoxide and quinone reductase activities in this large family of integral membrane enzymes remains unknown.

Based on the crystal structures, here we systematically replaced several regions surrounding the active site in SsVKOR with those from the HsVKOR and generated epoxide reductase activity in SsVKOR. Subsequently, we narrowed down to eight key residues and a membrane anchor domain that are responsible for this gained activity. With stabilization from the anchor domain, these key residues increase the pocket size to accommodate KO binding and provide two strong hydrogen bonds to promote the epoxide reduction. Overall, our study provides new insights into the catalytic mechanisms of a large oxidoreductase family, advancing the much-limited understanding of integral membrane enzymes.

Results

Comparison of the substrate-bound structures of SsVKOR and HsVKOR

We recently determined 11 crystal structures of HsVKOR and a VKOR-like paralog from Takifugu rubripes (TrVKORL) with substrates (KO and K) and antagonists in different redox states [23]; both VKOR and VKOR-like carry the epoxide and quinone reductase activities and their catalytic cycle is associated with redox-state changes [3]. Previously, we have also determined crystal structures of SsVKOR with bound ubiquinone in three different redox states [13, 24]. These extensive structural data allow us to select the structures of HsVKOR with bound KO (PDB 6WV5) and SsVKOR with bound ubiquinone (PDB 4NV5), captured in the same redox state, for direct comparison.

The overall architecture of HsVKOR and SsVKOR are remarkably similar (Figure 1A, B). Their active site is surrounded by a four-TM bundle and covered by a cap domain, which is made of a short helix (cap helix) followed by a loop (cap loop). Their four TMs and cap domain can be well superimposed, with a 1.8 Å RMSD (Cα-Cα). These homologous enzymes, however, differ mostly in a region after the cap domain. In SsVKOR, a β-hairpin structure connects the cap domain to TM2. This β-hairpin is not observed in HsVKOR, which instead forms a membrane anchor domain with additional sequence not found in SsVKOR (Figure 1B, C). This anchor domain is partially buried in the lipid bilayer and functions to stabilize the cap domain conformation [23]. Despite these differences, the substrates are bound at the active site of HsVKOR and SsVKOR at a similar position and in a similar orientation (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Identification of key regions responsible for epoxide reductase activity.

A, Superimposed structures of HsVKOR (PDB 6WV5) and SsVKOR (PDB 4NV5) showing high structural similarity. The transmembrane regions of HsVKOR and SsVKOR are colored in blue and dark grey, and their extramembrane domain between TM1 and TM2 colored in orange and purple, respectively. For clarity, TM5 and Trx-like domain of SsVKOR are omitted and only regions homologous to HsVKOR are shown. These figures were generated with CCP4mg [33]. B, Individual structures of SsVKOR and HsVKOR showing location of the substrate binding pocket and surrounding regions (in different colors). C, Sequence alignment of HsVKOR and SsVKOR. The identical residues are shaded in dark grey and similar residues in light grey. Regions surrounding the substrate-binding pocket are indicated above the sequences. Structural components of HsVKOR and SsVKOR are also indicated. The UniProt accession numbers of HsVKOR and SsVKOR are Q2JJF6 and Q9BQB6, respectively. Their sequence alignment was manually generated based on structural superimposition in A. D, Relative epoxide reductase activities of SsVKOR constructs (S1, S2 and S3), in which regions surrounding the substrate-binding pocket are substituted. The substitutions are indicated by grey and colored (as in B) blocks. The activities are measured by a cell-based carboxylation assay. Error bars are standard errors calculated from three repeats. E, Relative activities of the constructs with each region in S3 replaced back to the SsVKOR sequence (same colors as in D).

Gain of epoxide reductase activity in engineered SsVKOR and identification of essential regions

Because of the overall structural similarities, we postulate that the apparent different activities of HsVKOR and SsVKOR are due to the local changes around their substrate-binding pocket, which may affect the catalytic chemistry and/or the binding affinity of different substrates. Based on this postulation, we systematically analyzed the six structural regions surrounding the substrate-binding pocket (Figure 1B, C), consisting of the flexible loop connecting to TM1 (named L1); the cap domain and the following β-hairpin in SsVKOR (named CB); the additional membrane anchor domain in HsVKOR (named A); and the luminal or periplasmic portion of TM2, TM3, TM4 (named II, III, IV, respectively). We did not include the luminal portion of TM1 because it is relatively far from the substrate-binding pocket in both HsVKOR and SsVKOR structures.

Based on the above structural observation, we started by replacing the amino acid sequences of these SsVKOR regions with those from HsVKOR, and analyzed the epoxide reductase activity of the substituted constructs using a well-established cell-based assay. Two initial constructs did not show the epoxide reductase activity: substitution 1 (named S1 construct) replaced regions CB and II, III and IV of SsVKOR to HsVKOR sequence, and S2 construct replaced L1, CB, II, III and IV (Figure 1D). Remarkably, a S3 construct, with the membrane anchor domain inserted and all regions except L1 replaced, shows the epoxide reductase activity that is nearly 50% of HsVKOR activity. Because S3 gains much of the epoxide reductase activity without the L1 substitution, we concluded that this flexible loop is a nonessential component and therefore focused on regions CB, II, III, IV and membrane anchor domain thereafter. With the membrane anchor domain unchanged, we sequentially replaced region CB, II, III and IV in the S3 construct back to the SsVKOR sequence (Figure 1E). We found little activity in all these constructs, indicating that each of these regions contains certain features that are essential to the epoxide reductase activity of S3 construct.

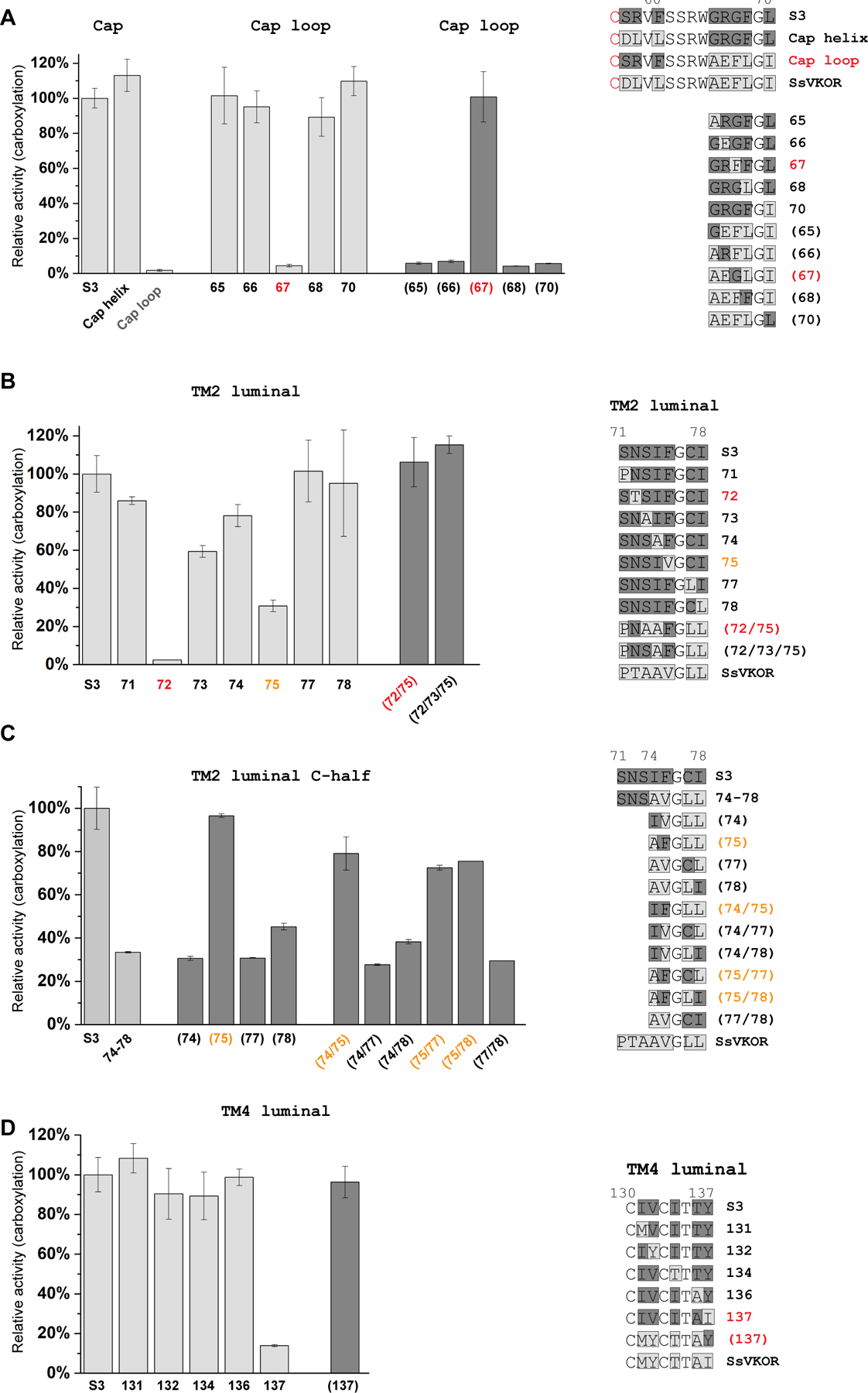

Identification of key residues in the cap domain, TM2 and TM4

To identify features critical to the gained activity, we systematically changed each residue in regions CB, II and IV from the S3 construct back to the SsVKOR sequence. The CB region (residues 57–70 in SsVKOR) can be further divided into three parts. Residues 57–60 form the cap helix; Residues 61–64 form the cap loop and is a conserved SSRW sequence between SsVKOR and HsVKOR; 65–70 form a β-hairpin in SsVKOR but is part of the cap loop and membrane anchor domain in HsVKOR (Figure 1C). Interestingly, replacing 57–60 back to the SsVKOR sequence does not decrease the epoxide reductase activity (Figure 2A), suggesting that the amino acid composition of this cap helix region is not essential to activity. In contrast, replacing 65–70 abolishes the epoxide reductase activity. To identify the essential residue(s) in this region, we sequentially mutated each nonconserved residues to the SsVKOR sequence. Remarkably, only G67F abolishes the epoxide reductase activity (Figure 2A). To confirm this observation, we first replaced the entire 65–70 in S3 with SsVKOR sequence and then mutated each residue back to the S3 (i.e., HsVKOR) sequence. In this reverse substitution experiment, only F67G substitution regains the epoxide reductase activity (Figure 2A). Taken together, within the entire CB region, a single F67G substitution is responsible for the gained epoxide reductase activity of engineered SsVKOR.

Figure 2. Identification of residues essential to the gained epoxide reductase activity in cap loop, TM2 and TM4.

A, F67G in β-hairpin is essential. The grey bars indicate substitutions of the S3 construct with SsVKOR sequence. The dark grey bars and numbers in parenthesis indicate back substitutions of SsVKOR sequence to S3 (i.e., HsVKOR sequence in this region). Sequence changes for each substituted construct are indicated on the right, with SsVKOR sequence shaded in light grey and S3 sequence in dark grey. B-C, T72N in TM2 luminal region is essential to the epoxide reductase activity and V75F contributes to this activity. D, I137Y in TM4 luminal region is essential. Substitutions of essential residues are colored in red and contributing residues in orange. Relative activities are measured and calculated as in Figure 1D. Error bars are standard errors calculated from three repeats.

Using the same strategy, we systematically mutated residues in region II (luminal portion of TM2). Only the N72T substitution to SsVKOR sequence abolishes the epoxide reductase activity of the S3 construct (Figure 2B). In addition, S73A and F75V show 60% and 30% activity compared to S3, respectively. For the reverse substitutions under SsVKOR background, T72N/V75F and T72N/A73S/V75F regain the full epoxide reductase activity (Figure 2B). To confirm the role of F75, we performed single and double substitutions on the C-terminal half of region II (residues 74–78), changing the S3 construct sequence to SsVKOR sequence (Figure 2C). The common observation for all these mutants is that, the activities are maintained at a high level (>70%) if F75 is retained. Conversely, if they carry the F75V substitution, the activities are lowered to ~30–50%. Thus, in region II, V75F contributes to the gained activity and T72N is essential.

At the luminal portion of TM4 (region IV), the Y137I substitution lowers the epoxide activity of S3 to 10%, whereas other substitutions retain most of the activity (Figure 2D). Consistently, under the SsVKOR background in region IV, a single reverse substitution, I137Y, restores to full activity (Figure 2D).

Overall, systematic mutagenesis in regions CB, II, and IV shows that generating the epoxide reductase activity in SsVKOR require three essential substitutions, F67G, T72N and I137Y, with contribution from V75F. These mutated residues correspond to G62, N80, Y139 and F83 in HsVKOR, respectively (Figure 1C).

Multiple residues in TM3 contribute to the epoxide reductase activity

In region III (luminal portion of TM3), several single substitutions (from S3 to SsVKOR sequence), S115E, L118M, I121L and L122M, lower the epoxide reductase activity to 20–40% (Figure 3A). To further investigate the relative contribution of these residues, we divided region III into two halves, 114–119 and 120–124. With SsVKOR sequence in either of these half regions, the epoxide reductase activity is nearly lost (Figure 3B), indicating that the residue composition in each half region is important.

Figure 3. Multiple substitutions in the TM3 luminal region contribute to the gained epoxide reductase activity.

A, Constructs with each of the four residues (S115/L118/I121/L122) changed from S3 to SsVKOR sequence show lowered activity (grey bars). A construct with all four residues changed from SsVKOR to HsVKOR sequence show full activity as the S3 construct (dark grey bar). B, Constructs with N- and C-half of the TM3 luminal region changed from S3 to SsVKOR sequence show low activity. Sequences of the substituted constructs are shown on the right, with SsVKOR sequence shaded in light grey and S3 sequence in dark grey (see text for interpretations). Relative activities are measured and calculated as in Figure 1D. Error bars are standard errors calculated from three repeats.

Next, we made double, triple, and quadruple substitutions at the N-terminal half of region III (residues 114–119). Double substitutions show that those involving S115E (114/115, 115/116, 115/118, 115/119) or L118M (114/118, 115/118, 116/118, 118/119) almost always exhibit low activity (Figure 4A). In particular, S115E/L118M shows nearly no activity. In contrast, retaining S115 and L118 in the sequence (114/116, 114/119 and 116/119) gives >75% activity. Similarly, triple substitutions show the highest activity in the 114/116/119 mutant (Figure 4B), where S115 and L118 are both retained. All the quadruple substitutions show low activity, in which S115 and/or L118 are mutated (Figure 4C). Consistently, S117E substitution in HsVKOR shows only 23% activity of the wildtype (Figure 4D). Taken together, E115S and M118L both contribute to the gained epoxide reductase activity.

Figure 4. Relative epoxide reductase activities of substitutions at the N- and C-half of SsVKOR TM3 luminal region and activities of HsVKOR mutants.

A-C, Double, triple and quadruple substitutions at the N-half of SsVKOR TM3 luminal region. D, HsVKOR mutants including the substitutions with small side chains (G84F and S117E), mutations of the two key hydrogen bonding residues (N80A and Y139F), and removal of the anchor domain. E-F, Double, triple and quadruple substitutions at the C-half of SsVKOR TM3 luminal region. Sequences annotations are same as in Figure 3. Relative activities are measured and calculated as in Figure 1D. Error bars are standard errors calculated from three repeats.

At the C-terminal half of region III (120–124), double substitutions with highest activity (>85%) is observed in the constructs where I121 and L122 are retained (120/123, 120/124 and 123/124) (Figure 4E). For the triple substitutions, the largest activity is observed for 120/123/124, where I121 and L122 are retained (Figure 4F). Conversely, constructs with I121 and L122 both mutated (121/122 and 120/121/122) show the lowest activity (~10%). All the quadruple substitutions show low activity (Figure 4G). Together, these data indicate that the combination of I121 and L122 is important for the activity in the C-half of region III.

Combining these 4 key substitutions in region III, we found that E115S/M118L/L121I/M122L (corresponding to S117/L120/I123/L124 in HsVKOR) show similar activity as the S3 construct (i.e., 114–124 all mutated to HsVKOR sequence) (Figure 3A). Overall, multiple residues in the TM3 luminal region contribute to the epoxide reductase activity, but there is not a single determinant of this activity. Instead, these residues in TM3 region may act together to shape the substrate-binding pocket. Consistent with this notion, the activity of 114/116 and 120/123 is ~1.2-fold higher than S3 (Figure 4A, 4E), suggesting that certain combination of the side chains may better shape the pocket for substrate binding.

An integral membrane anchor domain is required for the gained epoxide reductase activity

The membrane anchor domain in HsVKOR is amphipathic, containing an array of hydrophobic and hydrophilic residues that stabilize this domain at the membrane surface (Figure 5A). We tested whether this domain can be further minimized, aiming to identify its key features. We systematically made 2 amino acid deletions along this region in the S3 construct (Figure 5B). All these deletions show low activity in the cell-based assay, suggesting that the integrity of the membrane anchor domain is important to the gained epoxide reductase activity in SsVKOR. Next, we used various lengths of flexible linkers to replace the membrane anchor domain (Figure 5C), asking the question whether the major function of this domain is to increase the flexibility of the substrate-binding pocket. All of the replacements with flexible linkers result in low activities. Nevertheless, replacements with the longer linkers show relatively higher activity, suggesting that the flexibility of this region plays a role in the gained activity of engineered SsVKOR. To achieve high activity, however, an integral membrane anchor domain may be required to stabilize position of the cap domain and to allow local flexibility for KO to bind. Consistently, we found that deletion of the membrane anchor domain in HsVKOR decreases its activity significantly (Figure 4D).

Figure 5. Integrity of the introduced membrane anchor domain is essential to the gained epoxide reductase activity.

A, Structure of the HsVKOR anchor domain. The dashed line indicates the interface between membrane and aqueous phases. For clarity, the residues are numbered 1–15 as in B and C. This figure was generated with CCP4mg. B, Sequentially deletions in anchor domain (every two residues) result in low activity. C, Substitutions with various lengths of flexible linkers. Constructs with longer linkers show slightly recovered activity. Relative activities are measured and calculated as in Figure 1D. Error bars are standard errors calculated from three repeats.

Combination of key substitutions in SsVKOR to gain epoxide reductase activity

With the key residues identified in each of the regions, we next combined all their substitutions into a single construct. This include F67G in the β-hairpin, T72N and V75F in TM2, E115S, M118L, L121I and M122L in TM3, I137Y in TM4 (corresponding to G62, N80, F83, S117, L120, I123 and L124 in HsVKOR, respectively), and addition of the membrane anchor domain. Remarkably, this ‘minimum’ construct (named M1) shows ~50% the activity of HsVKOR, slightly higher than the initial S3 construct (Figure 6A). Next, we mutated each of these residues in the M1 construct back to the SsVKOR sequence. All mutants showed drastically lowered activity, and G67F, N72T, S115E and Y137I nearly completely abolished the activity (Figure 6B), reinstating the importance of each introduced substitution in M1 construct.

Figure 6. Minimally engineered SsVKOR show epoxide reductase activity.

A, Relative activity of the M1 construct that carries the eight key substitutions (see text) and the membrane anchor domain. B, Constructs with each substitution in M1 changed back to SsVKOR sequence show lowered activity.

Given that epoxide reductase activity is required for blood coagulation in vertebrates, but not in lower organisms, we investigated whether these key residues and anchor domain are more conserved in vertebrates. With HsVKOR sequence as the template, PSI-BLAST search against vertebrate, eukaryotic and prokaryotic database, and the data show that conservation of these key residues and the anchor domain in vertebrates (Figure 7), but not in lower organisms, which is consistent with their functional roles.

Figure 7. Conservation of key residues and anchor domain in vertebrate VKOR and VKOR-like proteins.

Letter size is proportional to amino acid frequency at each position in the sequence alignment. The blast search, sequence alignment and sequence logo plot are generated using the MPI Bioinformatics Toolkit [34]. The sequence alignment show that G62, N80 and Y139 of HsVKOR are nearly absolutely conserved, and S117, L120, I123 and L124 (i.e., residues on TM3) are highly conserved in vertebrates. The region corresponding to the membrane anchor domain has the same length in all vertebrate homologs, but their amino acid composition varies largely. On the other hand, search with the eukaryotic database shows that the 8 key residues are less conserved (e.g., N80 often changes to L and Y139 changed to H, and the length and sequence of the ‘anchor domain’ region vary largely. Search with the prokaryotic database shows that N80 is presented in many species, but also absent in many others. Y139 is less often found than W, V and L at this position. Residues in TM3 (S117, L120, I123 and L124) do not show much conservation, and G62 is not conserved. Sequence of the anchor domain is absent in most prokaryotic species.

Compared to HsVKOR, the M1 construct (as in SsVKOR) contains a naturally fused Trx-like domain, linked to the homologous VKOR domain via an additional TM5 [13]. We therefore removed TM5 and Trx-like from M1 and generated a M2 construct that contains only 4 TMs as HsVKOR does. The activity of M1 and M2 are similar (Figure 8A). Likewise, activity is retained with TM5 and Trx-like removed from the S3 construct (Figure 8A). To confirm the results from the cell-based activity assay, we purified the M1 and M2 in DDM detergent and analyzed their reductase activities with KO and K as the substrates [7, 13, 25]. Using an in vitro assay that detects the fluorescence of KH2, we found that M1 and M2 both show high activity of reducing KO to KH2 in this purified system (Figure 8B). As a control for relative activities, purified TrVKORL protein is used here because purified wildtype HsVKOR protein is unstable without bound warfarin [23], but introducing warfarin would complicate the activity assay. Because the KO to KH2 reduction requires the conversion of vitamin K quinone as the intermediate step, this assay measures the epoxide reductase and quinone reductase activities together. In other words, M1 and M2 carry both activities. Thus, TM5 and Trx-like domain are dispensable for the epoxide and quinone reduction by engineered SsVKOR.

Figure 8. The 4-TM constructs of minimally engineered SsVKOR retain epoxide reductase activity and are warfarin inhibitable.

A, Relative activities of M1 and M2 (TM5 and Trx-like domain removed) in cell-based assay. The S3 construct (Figure 1D) and S3 without TM5 and Trx-like (S3-TM5/Trx) are included for comparison. B, Relative activities of purified M1 and M2 protein. The enzymatic activity of KO to KH2 conversion is measured using a fluorometric assay. The purified VKOR-like protein from pufferfish (TrVKORL) is used for comparison here because purified HsVKOR protein is unstable without bound ligand. C, The gained epoxide activities of engineered SsVKOR constructs are inhibitable by warfarin. Left, warfarin inhibition curves. Right, comparison of warfarin IC50. Relative activities in A-C are measured and calculated as in Figure 1D. Error bars are standard errors calculated from three repeats.

Engineered SsVKOR constructs are inhibitable by warfarin

We asked whether warfarin can inhibit the gained activity of ‘minimally’ engineered SsVKOR constructs, which is another major difference between SsVKOR and HsVKOR. We found that the IC50 of warfarin inhibition against the S3 and M1 constructs are 190 nM and 400 nM, respectively, approximately 10 to 20-fold higher than that of HsVKOR (18 nM) (Figure 8C). Removal of the Trx domain from S3 and M1, however, increase warfarin IC50 to 1.11 μM (S3-TM5/Trx) and 1.87 μM (M2), respectively. Nevertheless, these engineered SsVKOR proteins become sensitive to warfarin inhibition. As a comparison, wildtype SsVKOR is inhibited by warfarin only at very high concentration [13]. Similarly, 1–10 mM warfarin is required to inhibit a VKOR homolog from Mycobacterium tuberculosis [14]. In contrast, warfarin hinders blood coagulation by effectively inhibiting (in nM range) both the epoxide and quinone reductase activities of HsVKOR [13, 21, 25]. Thus, the substitutions that favor the substrate binding also improve warfarin binding.

Structural comparison shows enlarged substrate binding pocket for epoxide reduction

To understand how the epoxide reductase activity is generated in the engineered SsVKOR, we constructed a structural model of the M2 construct (Figure 9A), for which a high activity is observed with the substitutions of the 8 key residues, the addition of membrane anchor domain, and without the potential interference from TM5 and Trx-like domain. Because the TM backbone conformations of SsVKOR and HsVKOR are essentially the same despite of many changes in their side chains (Figure 9B), we reasoned that the engineered SsVKOR should also retain this backbone conformation. In M2, 7 of the 8 key substitutions (except F67G) are on the TMs. Thus, we created the M2 structural model by directly changing these 8 sidechains on the SsVKOR crystal structure, and the conformations of these side chains follow those observed in the HsVKOR crystal structure. In addition, we added the anchor domain to this M2 model using the same conformation and same orientation relative to TM domain as in the HsVKOR crystal structure.

Figure 9. Epoxide reductase activity requires two strong hydrogen bonds and increased pocket size.

A, Structural model of the M2 construct. Owing to the high structural similarity between SsVKOR and HsVKOR (Figure 1A), the structure of the minimally substituted construct can be reliably modeled. B, The eight key substitutions around the substrate-binding pocket. The SsVKOR crystal structure (left) and model of the M2 construct (right) are compared. Carbons of the SsVKOR residues are colored in orange and those of the substitutions in dark grey. The KO substrate (from superimposed HsVKOR structure) is shown in blue. C, Key hydrogen bonds (dashed lines) and anchor domain introduced in M2. D, Comparison of the substrate-binding pocket in HsVKOR, SsVKOR and M2. The pocket is generated by CASTp and colored by hydrophobicity (orange: hydrophobic, blue: hydrophilic). Figures in A-C were generated with CCP4mg and figures in D were generated with UCSF Chimera [35].

Comparison between the structures of SsVKOR, M2, and HsVKOR shows that T72N and I137Y introduce two key hydrogen bonds that bind to the para-diketones on the naphthoquinone ring of KO (Figure 9B, C). These hydrogen bonds may increase the binding affinity of KO and/or facilitates the reduction chemistry [23, 26]. We also found that the sizes of substrate-binding pocket (Figure 9D) of HsVKOR (792 Å3) and M2 (874 Å3) are significantly larger than that of SsVKOR (685 Å3). The enlarged pocket may favor the binding of KO, whose epoxide group requires more space for binding and for avoiding direct interaction with hydrophobic side chains. In addition, mutating SsVKOR to M2 increases the hydrophobicity of the substrate binding pocket, thereby enhancing the two introduced hydrogen bonds.

Discussion

Among all the enzymes, vertebrate VKOR and VKOR-like are the only epoxide reductase known to date, an activity not even carried by their prokaryotic homologs. In this study, we have identified the key residues and structural features that determine the epoxide and quinone reductase activities in this large family of integral membrane enzymes.

The first determinant favoring the epoxide reduction is the two strong hydrogen bonds that bind the para-diketones of substrates. In HsVKOR, N80 and Y139 are located in a largely hydrophobic pocket that enhances the strength of these hydrogen bonds, and combined substitutions in the engineered SsVKOR generate a similar setting (Figure 9C). These strong hydrogen bonds increase the redox potential of the naphthoquinone[26] and stabilize charged reaction intermediates [23, 27–29] to facilitate epoxide reduction. Consistently, N80 and Y139 mutants of HsVKOR show impaired activity, and Y139 mutants accumulate a side product of KO reduction, indicating that these hydrogen bonds are important to catalysis [23, 28, 30]. The importance of these residues is also supported by their conservation in vertebrates (Figure 7), in which the epoxide reductase activity is required to maintain the vitamin K cycle. Compared to epoxide reduction, catalysis of the quinone reduction may have a lower energy barrier to cross. In support of this theory, previous study shows that DTT reduction of K is much faster than that of KO; the underlying sulfhydryl-quinone chemistry of DTT reduction is very similar to VKOR catalyzed reduction [28]. Thus, introducing these strong hydrogen bonds in engineered SsVKOR has a pronounced effect of promoting epoxide reduction.

Several residues surrounding the KO binding pocket contribute to its size and shape. The chemical structure of KO, with the epoxide group, is larger and more polar than that of K and ubiquinone. To accommodate the KO binding, the substrate pocket of HsVKOR is ~100 Å3 larger than that of SsVKOR. The pocket size of the engineered SsVKOR, calculated from the model we constructed, is increased by nearly 200 Å3, in which F67G and E115S substitutions contribute to enlarge this pocket and other key residues may further reshape the pocket for optimal KO binding. Overall, a larger and more hydrophobic substrate binding pocket is necessary to maintain the epoxide reductase activity of VKOR.

Presence of the membrane anchor domain is required for the higher epoxide reductase activity of both HsVKOR (Figure 4D) and engineered SsVKOR (Figure 5). Replacing this domain with a flexible linker recovers only a small fraction of activity, suggesting that a certain level of conformational flexibility favors KO binding. On the other hand, presence of the anchor domain may hinder dissociation of the cap domain from the transmembrane domain, thereby maintaining the integrity of KO binding pocket [23]. The dual functions of stabilizing the cap domain position and offering certain flexibility for KO binding are well compromised by the anchor domain that floats on the surface of the membrane, a notable feature of this membrane enzyme.

Despite the multiple substitutions, the gained activity of engineered SsVKOR is only 40–50% of HsVKOR activity. Thus, other unknown factors may contribute to the HsVKOR activity. For instance, interactions between TMs, including those near the cytosolic side, may stabilize the overall structure to maintain the substrate-binding pocket. Such interactions, however, have not been investigated in our current study. Compared to engineered SsVKOR, HsVKOR also contains additional structural features, such as the helical extension of TM1 [23], that we have not explored. Finally, the redox potential of catalytic cysteines in the engineered SsVKOR and HsVKOR can be different, which will result in different levels of active site cysteines in reduced state that contributes to a large portion of overall HsVKOR activity [31].

Our study here advances the understanding of a large family of membrane thiol oxidoreductases; compared to soluble enzymes, the catalytic mechanisms of integral membrane enzymes are much underexplored. VKOR homologs from bacteria to humans clearly share the same structural fold, but their epoxide and quinone reductase activities differ in the subtle differences in their sidechain interactions. Gain of epoxide reductase activity in engineered SsVKOR requires following features: two residues that provide strong hydrogen bonds to the para-diketone group of KO to facilitate its reduction, several surrounding residues that increase the size of the substrate-binding pocket and change its shape, and an amphipathic membrane anchor domain that maintains the integrity of this pocket but allows certain flexibility for optimal KO binding.

Materials and Methods

Plasmid construction

For the cell-based activity assay, SsVKOR and HsVKOR constructs were sub-cloned into the CMV multiple cloning site of an engineered pBud CE4.1 vector, which contains also a luciferase gene at the EF1α multiple cloning site. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed by Quikchange™ and the nucleotide sequences of all the constructs were verified by DNA sequencing. For activity assay using purified protein, M1 and M2 constructs of SsVKOR were cloned into PET28b expression vector. Pufferfish VKOR-like (TrVKORL) was cloned into a modified pPICZα expression vector [23]. The protein sequences of S3, S3-TM5/Trx, M1 and M2 can be found in Supplementary file 1.

Measurement of epoxide reductase activity by a cell-based activity assay

Cell-based assay of the epoxide reductase activity using a γ-carboxylation reporter were performed as previously described. Briefly, SsVKOR and HsVKOR were transfected into an established HEK293 cell line that contains a chimeric FIXgla-Protein C gene and has endogenous VKORC1 and VKORL1 genes knocked out. After 4–6 h transfection, the medium was replaced by fresh complete medium containing 5 μM vitamin K epoxide. The cells were incubated for 36–48 h. The medium was collected and 5 mM CaCl2 (final concentration) was added to the medium. To detect the carboxylation level of secreted FIXgla-PC, the ELISA plate was coated with 100 μL/well of anti FIXgla mAb (2 μg/mL GMA-001, Green Mountain Antibodies) for overnight at 4°C, and subsequently blocked by bovine serum albumin. The medium (or FIXgla-PC protein standards) were added to ELISA wells and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. The wells were washed five times with TBST buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20) containing 5 mM CaCl2. The HRP conjugated anti–human protein C IgG (SAPC-HRP, Affinity Biologicals) was added to each well (100 μL/well) and incubated for another 45 min at room temperature. After unbound antibody was washed off, ABTS substrate was added and the absorbance at 405 nm was measured with a plate reader. As the control for transfection efficiency, the activity of metridia luciferase was measured as previously described[15].

Analysis of warfarin responses in cell-based assay

To measure IC50s of warfarin in the HsVKOR and engineered SsVKOR constructs, the transfected cells were treated with 11 different concentrations of warfarin, with the concentration range optimized according to the warfarin response of each construct. The IC50 of each construct was analyzed using GraphPad Prism.

Expression and purification of M1, M2 and TrVKORL proteins

The M1 and M2 constructs were transformed into a C43(DE3) E. coli strain. The freshly transformed cells were inoculated to 6 L culture and grown at 37°C. At OD600 0.6–1, the cells were induced with 0.4 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 25°C overnight. The cells were collected by centrifugation and lysed by sonication. The lysed cells were centrifuged at 5,000 g to remove cell debris. The supernatant was centrifuged at 200,000g at 4°C to collect the membranes. Subsequently, the membrane fraction was solubilized in 1% dodecyl-D-maltopyranoside (DDM), 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 0.3 M NaCl and 10% glycerol. The detergent soluble fraction was incubated with TALON metal-affinity resin (Clontech) and washed in a buffer containing Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 0.1 M NaCl, 0.04% DDM with 20 mM imidazole. The protein was eluted with the same buffer with 0.3 M imidazole. The subsequent gel filtration chromatography was carried out in the same buffer without imidazole. The peak fractions of M1 and M2 proteins were collected and concentrated to 5 mg/mL.

TrVKORL was expressed and purified as previously described. Briefly, Pichia pastoris cells transformed with TrVKORL were grown in the buffered minimal glycerol media (1.2% glycerol, 0.34% yeast nitrogen base, 1% ammonium sulfate, 0.4 mg/ml biotin, and 100 mM potassium phosphate pH 6.0) at 30°C for 20 h. The growth media was exchanged to the media without glycerol, and the protein expression were induced with 0.7% methanol for 2 d at 25°C. The cells were frozen in liquid nitrogen and broken in a mixed mill. The cell powder was resuspended in lysis buffer (225 mM NaCl, 75 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, and 10 mg/mL DNase I) and 2% DDM (final concentration) was added to solubilize the membranes. The protein was purified with TALON metal-affinity resin (as described above). The eluted protein was applied to size exclusion chromatography (Superdex 200) in a buffer containing 0.05% lauryl maltose neopentyl glycol (LMNG), 150 mM NaCl, and 20 mM Tris pH 8.0. The peak fractions were combined and concentrated to 5 mg/mL.

Epoxide reductase activity assay of purified proteins

The reduction of KO to KH2 was measured using a fluorometric assay with the following modifications. Purified M1, M2 and TrVKORL proteins (3 μM) were mixed with in 20 μM KO in a buffer containing 100 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5 and 0.1% LMNG. The reaction was initiated by adding 50 mM reduced glutathione (final concentration)[6, 7]. The fluorescence of KH2 (250 nm excitation and 430 nm emission) was detected using a plate reader (Molecular Devices), and the reaction was followed for 1 h. The activity of M1 and M2 constructs (KH2 fluorescence over 1 h) was normalized by that of TrVKORL.

Structure modeling

The model of M2 construct was generated in the following way. The SsVKOR structure with bound ubiquinone (PDB code 4NV5) was superimposed with the HsVKOR structure with bound KO (PDB 6WV5); these substrate-bound structures are captured in the same redox state. Subsequently, the 8 key residues in SsVKOR structure (PDB code 4NV5) are substituted with the corresponding residues in HsVKOR, and their conformations are adjusted to match those in the HsVKOR structure. The membrane anchor domain was taken from the superimposed HsVKOR structure and attached (at the same conformation) to the SsVKOR model. In addition, TM5 and Trx-like domain was removed from this model. This constructed model is further energy minimized using the geometry minimization program installed in the Phenix suite tool: Phenix.refine [32].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

G.S. is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81770140, 82170133), Henan Department of Science & Technology (212102310629, 212102310877) and Henan Department of Education (2017GGJS069). M. Gao is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (31900412). W. Li is supported by NEI (R21 EY028705) and NHLBI (R01 HL121718).

Abbreviations

- VKOR

Vitamin K epoxide reductase

- HsVKOR

Homo sapiens VKOR

- SsVKOR

Synechococcus sp. VKOR

- TrVKORL

Takifugu rubripes VKOR-like

- KO

vitamin K epoxide

- K

vitamin K quinone

- KH2

vitamin K hydroquinone

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- TM

transmembrane helix

- WT

wildtype

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- IPTG

isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside

- DDM

dodecyl-D-maltopyranoside

- LMNG

lauryl maltose neopentyl glycol

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Data availability

All other relevant data are contained within the article and accompanying supporting information.

References

- 1.Goodstadt L & Ponting CP (2004) Vitamin K epoxide reductase: homology, active site and catalytic mechanism. Trends Biochem Sci 29, 2002–2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sadler JE (2004) K is for koagulation. Nature 427, 5–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stafford DW (2005) The vitamin K cycle. J Thromb Haemost 3, 1873–1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schulman S, Wang B, Li W & Rapoport Ta (2010) Vitamin K epoxide reductase prefers ER membrane-anchored thioredoxin-like redox partners. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 15027–15032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rishavy MA, Usubalieva A, Hallgren KW & Berkner KL (2011) Novel insight into the mechanism of the vitamin K oxidoreductase (VKOR): electron relay through Cys43 and Cys51 reduces VKOR to allow vitamin K reduction and facilitation of vitamin K-dependent protein carboxylation. J Biol Chem 286, 7267–7278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li S, Liu S, Liu XR, Zhang MM & Li W (2020) Competitive tight-binding inhibition of VKORC1 underlies warfarin dosage variation and antidotal efficacy. Blood Adv 4, 2202–2212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li S, Liu S, Yang Y & Li W (2020) Characterization of Warfarin Inhibition Kinetics Requires Stabilization of Intramembrane Vitamin K Epoxide Reductases. J Mol Biol 432, 5197–5208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shen G, Cui W, Zhang H, Zhou F, Huang W, Liu Q, Yang Y, Li S, Bowman GR, Sadler JE, Gross ML & Li W (2017) Warfarin traps human vitamin K epoxide reductase in an intermediate state during electron transfer. Nat Struct Mol Biol 24, 69–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li S, Shen G & Li W (2018) Intramembrane Thiol Oxidoreductases: Evolutionary Convergence and Structural Controversy. Biochemistry 57, 258–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feng W-K, Wang L, Lu Y & Wang X-Y (2011) A protein oxidase catalysing disulfide bond formation is localized to the chloroplast thylakoids. The FEBS journal 278, 3419–3430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dutton RJ, Boyd D, Berkmen M & Beckwith J (2008) Bacterial species exhibit diversity in their mechanisms and capacity for protein disulfide bond formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 11933–11938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang X, Dutton RJ, Beckwith J & Boyd D (2011) Membrane topology and mutational analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis VKOR, a protein involved in disulfide bond formation and a homologue of human vitamin K epoxide reductase. Antioxidants & redox signaling 14, 1413–1420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li W, Schulman S, Dutton RJ, Boyd D, Beckwith J & Rapoport TA (2010) Structure of a bacterial homologue of vitamin K epoxide reductase. Nature 463, 507–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dutton RJ, Wayman A, Wei JR, Rubin EJ, Beckwith J & Boyd D (2009) Inhibition of bacterial disulfide bond formation by the anticoagulant warfarin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 297–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tie JK, Jin DY, Tie K & Stafford DW (2013) Evaluation of warfarin resistance using transcription activator-like effector nucleases-mediated vitamin K epoxide reductase knockout HEK293 cells. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 11, 1556–1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tie JK & Stafford DW (2016) Structural and functional insights into enzymes of the vitamin K cycle. In, pp. 236–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sinhadri BCS, Jin DY, Stafford DW & Tie JK (2017) Vitamin K epoxide reductase and its paralogous enzyme have different structures and functions. Sci Rep 7, 17632–17632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tie J-kK, Nicchitta C, Heijne GV, Stafford DW & Von Heijne G (2005) Membrane topology mapping of vitamin K epoxide reductase by in vitro translation/cotranslocation. J Biol Chem 280, 16410–16416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tie JK, Jin DY & Stafford DW (2014) Conserved Loop Cysteines of Vitamin K Epoxide Reductase Complex Subunit 1-Like 1 (VKORC1L1) Are Involved in Its Active Site Regeneration. J Biol Chem 289, 9396–9407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen D, Cousins E, Sandford G & Nicholas J (2012) Human Herpesvirus 8 Viral Interleukin-6 Interacts with Splice Variant 2 of Vitamin K Epoxide Reductase Complex Subunit 1. Journal of Virology 86, 1577–1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tie J-K, Jin D-Y & Stafford DW (2012) Human vitamin k epoxide reductase and its bacterial homologue have different membrane topologies and reaction mechanisms. J Biol Chem 287, 33945–33955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cao Z, van Lith M, Mitchell LJ, Pringle MA, Inaba K & Bulleid NJ (2016) The membrane topology of vitamin K epoxide reductase is conserved between human isoforms and the bacterial enzyme. Biochemical Journal 473, 851–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu S, Li S, Shen G, Sukumar N, Krezel AM & Li W (2021) Structural basis of antagonizing the vitamin K catalytic cycle for anticoagulation. Science 371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu S, Cheng W, Fowle Grider R, Shen G & Li W (2014) Structures of an intramembrane vitamin K epoxide reductase homolog reveal control mechanisms for electron transfer. Nat Commun 5, 3110–3110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chu P-H, Huang T-Y, Williams J & Stafford DW (2006) Purified vitamin K epoxide reductase alone is sufficient for conversion of vitamin K epoxide to vitamin K and vitamin K to vitamin KH2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103, 19308–19313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hui Y, Chng EL, Chua LP, Liu WZ & Webster RD (2010) Voltammetric method for determining the trace moisture content of organic solvents based on hydrogen-bonding interactions with quinones. Anal Chem 82, 1928–1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silverman RB (1981) Chemical Model Studies for the Mechanism of Vitamin K Epoxide Reductase. J Am Chem Soc 103, 5939–5941. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fasco MJ, Preusch PC, Hildebrandt E & Suttie JW (1983) Formation of hydroxyvitamin K by vitamin K epoxide reductase of warfarin-resistant rats. J Biol Chem 258, 4372–4380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davis CH, Deerfield D, Wymore T, Stafford DW, Pedersen LG & Transition II (2007) A quantum chemical study of the mechanism of action of Vitamin K epoxide reductase (VKOR). J Mol Graph Model 26, 401–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee JJ & Fasco MJ (1984) Metabolism of vitamin K and vitamin K 2,3-epoxide via interaction with a common disulfide. Biochemistry 23, 2246–2252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shen G, Cui W, Cao Q, Gao M, Liu H, Su G, Gross ML & Li W (2021) The catalytic mechanism of vitamin K epoxide reduction in a cellular environment. J Biol Chem 296, 100145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Afonine PV, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Moriarty NW, Mustyakimov M, Terwilliger TC, Urzhumtsev A, Zwart PH & Adams PD (2012) Towards automated crystallographic structure refinement with phenix.refine. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 68, 352–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McNicholas S, Potterton E, Wilson KS & Noble ME (2011) Presenting your structures: the CCP4mg molecular-graphics software. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 67, 386–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alva V, Nam SZ, Soding J & Lupas AN (2016) The MPI bioinformatics Toolkit as an integrative platform for advanced protein sequence and structure analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 44, W410–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC & Ferrin TE (2004) UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem 25, 1605–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All other relevant data are contained within the article and accompanying supporting information.