Abstract

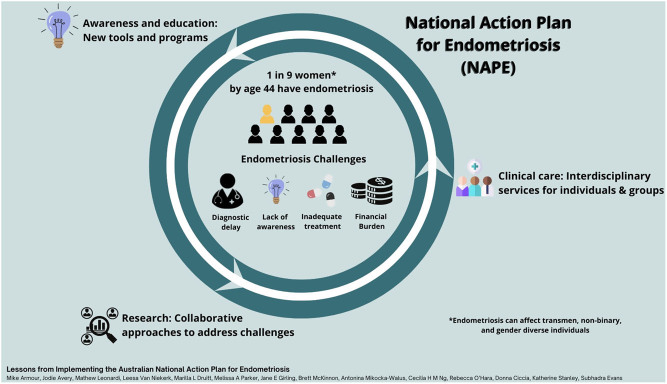

Graphical abstract

Abstract

Endometriosis is a common yet under-recognised chronic disease with one in nine (more than 830,000) women and those assigned female at birth diagnosed with endometriosis by the age of 44 years in Australia. In 2018, Australia was the first country to develop a roadmap and blueprint to tackle endometriosis in a nationwide, coordinated manner. This blueprint is outlined in the National Action Plan for Endometriosis (NAPE), created from a partnership between government, endometriosis experts and advocacy groups. The NAPE aims to improve patient outcomes in the areas of awareness and education, clinical management and care and research. As researchers and clinicians are working to improve the lives of those with endometriosis, we discuss our experiences since the launch of the plan to highlight areas of consideration by other countries when developing research priorities and clinical plans. Historically, major barriers for those with endometriosis have been twofold; first, obtaining a diagnosis and secondly, effective symptom management post-diagnosis. In recent years, there have been calls to move away from the historically accepted ‘gold-standard’ surgical diagnosis and single-provider specialist care. As there are currently no reliable biomarkers for endometriosis diagnosis, specialist endometriosis scans and MRI incorporating artificial intelligence offer a novel method of visualisation and promising affordable non-invasive diagnostic tool incorporating well-established technologies. The recognised challenges of ongoing pain and symptom management, a holistic interdisciplinary care approach and access to a chronic disease management plan, could lead to improved patient outcomes while reducing healthcare costs.

Lay summary

Endometriosis is a chronic disease where tissue like the lining of the uterus is found in other locations around the body. For the 830,000 people living with endometriosis in Australia, this often results in an immense burden on all aspects of daily life. In 2018, Australia was the first country to introduce a roadmap and blueprint to tackle endometriosis in a nationwide coordinated manner with the National Action Plan for Endometriosis. This plan was created as a partnership between government, endometriosis experts and advocacy groups. There are several other countries who are now considering similar plans to address the burden of endometriosis. As researchers and clinicians are working to improve the lives of those with endometriosis, we share our experiences and discuss areas that should be considered when developing these national plans, including diagnostic pathways without the need for surgery, and building new centres of expertise in Endometriosis and Pelvic Pain.

Key Words: diagnosis, Australia, endometriosis, expertise, ultrasound

Introduction

As researchers and clinicians are working to improve the lives of those with endometriosis, this piece aims to highlight the significant financial burden experienced by the large number of affected individuals in our communities. We focus on the National Action Plan for Endometriosis (NAPE) (Australian Government Department of Health 2018), developed as an initiative by endometriosis advocacy organisations (Australian Coalition for Endometriosis (ACE) 2018), with government support, to help support new advances in diagnosis and treatment. We outline the successes thus far and suggest approaches to help tackle the still ongoing health inequalities experienced by those with endometriosis that may be useful both to those in Australia and to the number of countries that have announced an intention to develop a similar plan for endometriosis.

Pelvic pain is an umbrella term for a multitude of conditions related to the bladder, bowel, reproductive organs, musculoskeletal and peritoneal spaces of the pelvis. Under this umbrella sits endometriosis, a condition where tissue similar to the lining of the uterus is found in various locations outside the uterus (Johnson et al. 2017). Endometriosis affects around one in nine women, transgender, non-binary and gender-diverse people assigned female at birth in Australia by the age of 44 (Rowlands et al. 2021), with an estimated diagnostic delay of between 6.4 and 8 years (Armour et al. 2020b, O’Hara et al. 2020). Box 1 outlines the care pathway for those with endometriosis in Australia. The disease can negatively impact all aspects of an individual’s life, including work, education, sexual and social relationships, self-identity and body image (Moradi et al. 2014, Melis et al. 2015, Armour et al. 2020b, Van Niekerk et al. 2021). Endometriosis has been associated with a loss of productivity in the workplace (Armour et al. 2019a), and it is not uncommon for people with endometriosis to have to work reduced hours due to their symptoms; over one in ten people with endometriosis have reported losing their job because of the disease (Armour et al. 2020b).

Box 1 The Australian Healthcare System and care pathway for those with endometriosis

While there is variation across the different states and territories in Australia (including if the individual is living in an urban, rural or remote area), in general, gynaecologists typically lead the care for endometriosis in Australia, while the condition is monitored by general practitioners (GPs) (Young et al. 2016). However, this varies depending on access to gynaecology services, and in some rural or remote locations, the majority of care may be provided by the GP. There is currently a lack of information on the pathways via which those with endometriosis access the Australian healthcare system but people with endometriosis report often having to see several general practitioners and gynaecologists prior to getting diagnosis and treatment for their endometriosis (Armour et al. 2020b , Evans et al. 2021, Hawkey et al. 2022).

Australia’s national healthcare scheme called Medicare provides access to free health services in a public hospital setting. Australian residents can opt to pay out of pocket for private health insurance with 44.9% of the population choosing this additional private health cover as of December 2021 (Australian Prudential Regulation Authority 2022). When purchasing private health insurance, consumers have the option to purchase hospital cover only, ‘extras’ or combined hospital and ‘extras’ cover. This ‘extras’ cover usually includes cover for allied health services such as physiotherapists, dieticians and acupuncture, which is otherwise not normally covered by the Medicare system. Private health cover, irrespective of the level of cover, provides access to private hospitals and ‘upgraded’ facilities in public hospitals such as access to single-occupant rooms.

Some gynaecologists and GPs charge no out-of-pocket fees (so called ‘bulk billing’); however, most will levy a fee or surcharge on top of the Medicare rebate. In general, when seeing a health professional who does not offer bulk billing, the consumer pays the full fee upfront and then the Medicare rebate portion is then refunded directly into their bank account.

The costs of endometriosis

The cost of illness burden associated with endometriosis, calculated using the WERF EndoCost tool is approximately AUD $9.6 billion per year or roughly $30,000 per person with endometriosis per year (Armour et al. 2019a). Like other countries (Nnoaham et al. 2011), the majority of these costs reflect lost productivity (Armour et al. 2019a). However, there are also a large number of out-of-pocket expenses reflecting the costs of pharmaceutical medications, investigations, surgery, carer support, fertility treatment (such asin vitro fertilisation) and allied health and complementary therapies including dietary changes and medicinal cannabis (Armour et al. 2019a, 2021c, Sinclair et al. 2019, O’Hara et al. 2020). Consequently, those with endometriosis have to contend not only with reduced income (e.g., part-time work, use of sick leave, missed opportunities) but also considerable expenses related to disease management. The financial issues are highlighted in several articles written by those with endometriosis discussing the ‘crippling’ financial consequences (Aubusson 2019, Burke 2021, Maslen 2021). Box 2 outlines the experiences of some of the endometriosis support and advocacy organisations in Australia. Despite the significant evidence demonstrating the financial and personal burdens of endometriosis in Australia (Moradi et al. 2014, Armour et al. 2019a, 2020b, O’Hara et al. 2020), funding targeted at this disease is still insufficient. While the Australian Government has released approximately AUD $22.5 million in funding as of September 2021 (Australian Government Department of Health 2021d) as part of the NAPE (Australian Government Department of Health 2018), this seems insufficient given the cost of illness burden is estimated at over AUD $20 million per day. Indeed, when compared to diseases with a similar prevalence and cost of illness burden such as diabetes and heart disease (Simoens et al. 2012), endometriosis receives a fraction of this funding (NHMRC 2021).

While health economics are compelling, it is the qualitative research that captures the lived experiences and concerns of people and allows exploration of unexpected findings that quantitative surveys may not reveal. Qualitative studies have documented the quality-of-life issues associated with endometriosis (Hawkey et al. 2022), pointing to disruptions in education and employment; these studies also highlight the prohibitive costs associated with endometriosis management, which span difficulties paying for additional supplies of tampons and sanitary pads to expensive out-of-pocket surgeries and infertility treatments (Moradi et al. 2014, Roomaney & Kagee 2018). We have recently collected qualitative data via an open-ended survey question from a community sample of 133 Australians aged 18–50 years with self-reported endometriosis (unpublished data). We asked participants to describe (i) the financial impact of endometriosis and (ii) how workplaces might better support them. The main financial concerns identified included costs of surgery, work productivity, healthcare and complementary treatment provider appointments, tampons/pads and pain medication. Participants described being burdened by excessive debt and even having to sell their homes to pay for treatment. The financial burden often extended to family and friends, with participants owing family members tens of thousands of dollars. Many women felt that debt related to pain medication and treatment was an investment in their future financial lives:

I recently had a very expensive excision surgery that I could not have afforded without family support. Since this surgery, I feel I am capable of working, but the pain was a large contributor to me not having a job before surgery.

Workplaces have a substantial role in ameliorating this burden (Armour et al. 2021a ), with participants commenting that supportive workplaces with flexible work arrangements, paid sick leave and female staff that understand menstrual health helped to offset financial concerns. Such support is imperative when considering the physical and mental health problems arising from such gendered poverty and economic distress:

It’s very isolating. To be left with impossible medical costs not covered by Medicare or health insurance. To work my absolute hardest but not bring in enough money to fully cover my medical and living costs. It’s lonely. It’s demoralising.

Further in-depth qualitative research is needed to understand how the economic inequalities facing people with endometriosis can be best addressed and where support is needed most.

Box 2 What are the experiences of people in endometriosis support and advocacy groups?

The Endo Help Foundation holds monthly Talking Endo support group meetings across Geelong and the Bellarine (near Melbourne, Victoria, Australia) for those with Endometriosis and other pelvic pain conditions. A regular topic of discussion is the cost of endometriosis and the extra stress and burden that creates. It has been noted across several meetings that many attendees do not own houses, and some live with their parents to cover the high cost of treatment. Many in our group talk about not having the money to go out or socialise because they spend all their money on medication and other treatments, so they can maintain a good enough quality of life to continue to work. Very long wait times on public hospital lists have meant that many women have also cashed in their superannuation to pay for surgery by a private surgeon. Many have spoken about feeling pressure to not complain about the financial burden that they endure, as they are the lucky ones, able to cash in their super, or live with their parents to get the care they need through the private system. The financial burden of this disease is impacting women’s ability to work and live to their full potential and means many will not be able to retire securely.

In a recent discussion in the Endometriosis Australia closed patient forum, people overwhelmingly shared their number one concern was how significantly endometriosis impacted their ability to work. Having their employment and earning potential inhibited by the disease feeds into a vicious cycle of affordability of living with endometriosis. Overall, the community felt it was a combination of outgoing expenses, including the cost of surgery, specialist and general practitioner appointments, allied and complementary health appointments, medications, private health insurance, and lifestyle health considerations, that compounded the overall expense of living with endometriosis. Coupling these significant outgoing costs with limits put on their earning potential, it is a real challenge for patients to survive and thrive when living with this insidious disease.

The changing landscape of diagnosis

While the time to diagnosis in Australia is decreasing (Armour et al. 2020b), most likely due to the publication of clinical guidelines and increased awareness, diagnosing endometriosis remains a significant challenge for healthcare providers. Historically, direct visualisation at the surgery with histological confirmation has been the gold standard method of diagnosing endometriosis (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE] 2017). However, surgery is one of the most expensive diagnostic tools that exist; it is also potentially risky, less accessible than other traditional diagnostic methods such as imaging and subject to significant operator knowledge and skill. The combination of risk and an inability to readily access surgery as a diagnostic tool may be a significant factor in the ~6–8 year diagnostic delay (Armour et al. 2020b, O’Hara et al. 2020) and has led to significant research effort aiming to find means by which individuals can be diagnosed based on clinical symptoms and physical examination findings. However, most patients are aware that surgery is the gold standard method and may not consider an alternative method truly diagnostic (Leonardi et al. 2021). This can exacerbate the diagnostic delay for patients with endometriosis, contributing to the ongoing costs for the patient and the healthcare system. Additional costs are incurred when surgery is intended to be diagnostic and therapeutic, but the therapeutic element is abandoned (Leonardi et al. 2019b). This regularly occurs when the endometriosis stage is more severe than anticipated and the surgeon does not have the necessary skill and/or the patient is inadequately consented for the necessary procedure.

Besides surgery, other methods for diagnosis have been evaluated. Over 15,000 papers appraising non-invasive endometriosis diagnostic tests were systematically reviewed and found that the diagnostic accuracy of endometriosis biomarkers in blood, urine and endometrial tissues was too low for an effective clinical tool (Liu et al. 2015, Gupta et al. 2016, Nisenblat et al. 2016a, b, c. The diagnostic tools with the most potential were found to be specialist endometriosis ultrasounds (eTVUS) and MRI (eMRI); however, using these individually were not found to be sufficient to replace surgery. Currently, in Australia, laparoscopy costs AUD $6500 whereas an eTVUS scan costs AUD $260 and an eMRI costs AUD $440.

Researchers have been researching novel strategies to overcome the current limitations of more rapid and affordable non-invasive diagnosis. These include devising ways to visualise the most difficult to diagnose superficial endometriosis and to combine the diagnostic potential of eTVUS and eMRIs, using artificial intelligence to create an algorithm that predicts the probability of a diagnosis of endometriosis (Leonardi et al. 2019a, 2020). This hopes to alleviate some of the risks and accessibility issues faced by many people trying to obtain a timely diagnosis (Surrey et al. 2020). A new combined imaging tool may offer a lower-cost gateway to diagnosis and a more efficient clinical workflow. Considerable cost savings will ensue for the Australian Healthcare system and those with endometriosis. This tool may also be enhanced by adding other diagnostic, clinical information and demographics, which may be derived from large disease registries such as the National Endometriosis Clinical and Scientific Trials (NECST) Registry (see below).

In young women, early screening of menstrual disturbance with tools such as the Period ImPact and Pain Assessment (PIPPA) tool (Parker et al. 2021) and a stepped pathway of first-line treatment and emphasis on healthy lifestyle measures provides a lower-cost diagnostic pathway for the early management of painful periods and possible endometriosis. Given that over 50% of young women in Australia report regular non-menstrual pelvic pain (Armour et al. 2020a), early screening and subsequent diagnosis, if warranted, are vital. There are several initiatives to help improve menstrual health literacy amongst the general population including the EndoZone project (www.endozone.org.au), a digital health platform and gateway to endometriosis research and evidence-based information and Menstruation Matters (www.menstruationmatters.com.au), an online resource that includes the PIPPA tool to help screen for problematic symptoms and evidence-based self-care advice.

Challenges with the current clinical management of endometriosis in Australia

The historical paradigm through which endometriosis is managed adds to the cost burden. Still considered a single disease, unified through the histological presentation of cells within tissue excised from the peritoneal cavity, the heterogeneity in patient presentations, symptoms, lesion appearance and eventual outcomes is seldom recognised when designing patient management pathways (Colgrave et al. 2021). This results in a trial-and-error approach to settle on the clinical management acceptable to the patient (Poulos et al. 2019). The prevailing model of endometriosis care in Australia reflects this westernised biomedical approach, with a single provider caring for a person living with the disease. The solo-provider model has been associated with persisting symptoms, long delays in diagnosis, repeated surgeries and low care satisfaction (Agarwal et al. 2021). As few as 24% of Australian women with endometriosis are satisfied with the management of their condition, with barriers to accessing interdisciplinary care that addresses functioning beyond infertility and pain one of the main reasons for dissatisfaction (Evans et al. 2021).

A blinkered view of endometriosis as the sole cause of pelvic pain means that coinciding and comorbid conditions are left unrecognised and untreated, with the misconception that previously treated endo ‘is back’. This can lead to the unnecessary risks and cost burden of repeat surgeries that do not treat myofascial pain or microbiome issues, as examples. The complexity of endometriosis increases the imperative for comprehensive screening and appropriate, affordable treatment options.

Issues with funding and reimbursement are also significant barriers to adequate and affordable endometriosis care. In Australia, individuals diagnosed with endometriosis may be eligible to access a general practitioner-led chronic disease management plan (CDMP) (Australian Government 2021), designed to facilitate coordinated care for people with chronic diseases. As part of the CDMP, individuals can access up to five Medicare-subsidised visits to a range of allied health services (e.g., physiotherapy, psychology, dietitian). Although endometriosis meets the criteria for a chronic disease in Australia (O’Hara et al. 2018), only 15.4% of surveyed endometriosis patients reported having a CDMP (O’Hara et al. 2020). Although this may initially appear to indicate a significant untapped opportunity for those with endometriosis to access interdisciplinary care, the availability of CDMPs may not remove the financial barrier to accessing affordable treatment for many. General practitioners remain the gateway to accessing allied health services, as the coordinators of the plan, and require a knowledge of available qualified allied health practitioners. Furthermore, the availability of five sessions, across all allied health fields, may limit the individual’s ability to access regular effective management due to financial burden as the subsidy provided is often ~50% or less of the total cost. The inclusion of various treatment providers in the CDMP promotes an interdisciplinary approach where the care team consists of individual providers, across multiple treatment locations, rather than one co-located care team. The inclusion of individual treatment providers may not facilitate the shared care arrangement that facilitates effective and coordinated treatment.

In the Australian public healthcare system, gynaecology clinics have historically focussed on investigations for endometriosis, offering hormones and surgery, rather than interdisciplinary care. This is likely in part due to the structure of the Medicare Benefits schedule (MBS) in Australia, which is a list of the medical services for which the Australian Government will pay a rebate to provide patients with financial assistance towards the costs of their medical services. The MBS does not adequately fund interdisciplinary pain management and rewards doctors for performing surgery over talking to their patients. For example, in gynaecology, MBS rebate amounts are 200 times more for surgery vs consulting (Australian Government Department of Health 2021a). Gender inequality issues are also present in the current MBS structure, impacting people with endometriosis. For example, the pelvic ultrasound rebate amount (Item 55065) is less than one to scan a scrotum (Item 55048) and no MRI rebate exists for the investigation of a woman’s pelvic pain.

Self-management for endometriosis symptoms

Given the ongoing challenges of pain and symptom management, it is perhaps unsurprising that many people are choosing to engage in self-management (Armour et al. 2019c, O’Hara et al. 2020) with as many as 89% of Australian women with endometriosis using complementary and self-care approaches to manage pain (Evans et al. 2021). People with endometriosis often need to seek regular care from general practitioners, medical specialists (e.g. gynaecologists), allied health providers (e.g. mental health practitioners and physiotherapists) and complementary therapists (e.g., massage therapists and acupuncturists) (O’Hara et al. 2020). Similarly, McKay et al. (2021) found that individuals with symptomatic endometriosis reported engaging in multiple management options including pelvic physiotherapy (26%) and psychology (24%), with only 8% of the sample indicating that they were not engaged in active treatment (McKay et al. 2021). In addition to seeking out support from health professionals, many of those with endometriosis are also self-managing by changing diets (Armour et al. 2021c) or using cannabis medicinally (Sinclair et al. 2019). All of these self-management options come with a cost (Malik et al. 2022), further adding to the cost burden on individuals and their families.

The blueprint for tackling this disease

The NAPE, officially launched in July 2018, is Australia’s roadmap and blueprint to tackle endometriosis (Australian Government Department of Health 2018). It is the first of its kind under the Commonwealth Health Portfolio, and since then, a further 12 National Action Plans have been published (e.g. heart disease and stroke, pain management, stillbirth, arthritis, kidney disease, macular disease, rare diseases, inflammatory bowel disease to name a few) (Australian Government Department of Health 2021c). The Action Plan was borne from the advocacy of a group of passionate patients and consumer groups, clinicians, researchers, and parliamentarians who came together to shine a light on endometriosis. The National Action Plan represents a coordinated, nationwide approach to improve patient outcomes and reduce the cost burden; the aspirational goal of the NAPE is to achieve prevention and cure. The Plan also aims to provide a better coordinated, targeted and accountable way to spend health dollars.

Three priority areas incorporate goals to address the knowledge gaps related to endometriosis and to improve outcomes for people living with the disease in Australia:

Awareness and education

Clinical management and care

Research

The National Action Plan in 2021 awareness and education

In the education sphere, the Pelvic Pain Education Program (PPEP) Talk® has been developed by the Pelvic Pain Foundation of Australia (The Pelvic Pain Foundation of Australia 2021b ), the programme is targeted at secondary-school-aged children and delivers content about menstrual periods and what constitutes ‘normal’. This education programme is not gender-specific and is tailored to all, ensuring that those who may be carers or supporters of endometriosis patients in the future will also understand the burden and impact of living with such a condition.

The National Action Plan in 2021 clinical management and care

The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG) was tasked to develop Australia’s first set of evidence-based Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Endometriosis; these guidelines were published in May 2021 (RANZCOG 2021). These guidelines were developed following a similar process used for the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Guidelines for Endometriosis (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE] 2017) where a combination of evidence-based recommendations and an expert consensus was used for guideline development. The overall treatment recommendations from the 2021 RANZCOG guidelines are similar to those in the most recent 2022 ESHRE guidelines (Members of the Endometriosis Guideline Core Group et al. 2022) and report similar levels of uncertainty of benefit for many of the interventions. Additionally, RANZCOG worked with expert gynaecologists, general practitioners, pain medicine specialists, fertility specialists, emergency physicians and nurses to create the Raising Awareness Tool for Endometriosis (RATE) (RANZCOG 2020). This is an online resource to help health professionals and their patients identify and assess endometriosis and its related symptoms. The Australian College of Nursing has introduced a unit of study for nurses and midwives aiming to help improve the care and management of those living with endometriosis and pelvic pain (Australian College of Nursing (ACN), Undated).

The National Action Plan in 2021 research

The NECST Network was established in 2018 (www.necstnetwork.org.au). This national collaborative initiative brings together clinicians, healthcare providers (e.g. allied and complementary health), researchers and endometriosis advocates to guide and undertake the research that will address the identified knowledge gaps in endometriosis care. It formalises the multi- and interdisciplinary clinical and scientific streams and addresses research in not only endometriosis but also adenomyosis and other endometriosis-related conditions (e.g. chronic pelvic pain in those without a diagnosis of endometriosis).

In addition to those resources and programmes that are supported by the National Action Plan, clinicians are also developing innovative solutions to address the shortcomings with the solo-provider model. Evaluation of a Queensland-based clinic for women with persistent pelvic pain demonstrated a nearly 20% reduction in emergency department presentations over 12 months as well as shorter hospital stays, reduced clinic presentations and a drop in the use of opiates (Wilkinson et al. 2021).

The way forward

The following are the authors recommendations and are based on the principles of the NAPE and the National Strategic Action Plan for Pain Management (Australian Government Department of Health 2021b) and include changes to the MBS system, the establishment of Centres of Expertise and pain education for healthcare providers and the community:

Clinical management and care

Endometriosis-related pain needs to be recognised as a complex condition for the purposes of MBS rebates. Currently, the MBS provides the chronic disease management plan, which can be used to access pelvic physiotherapy and other allied healthcare services, and the Mental Health Treatment Plan, which can be used to access 20 psychology sessions in a year to support the mental health needs of people with endometriosis. In addition to these, a new MBS item is needed for pain education by medical, nursing or allied health practitioners, similar to the diabetes educator model which is already funded under the MBS (Australian Government Department of Health 2021b). This item could be used to support patients to access individual services and group services, to be delivered by an interdisciplinary team, with telehealth services available. In addition, MBS rebates need to incentivise gynaecologists to provide biopsychospiritual care to patients, rather than incentivising surgery alone.

Centres of Expertise should be established, where evidence-based interdisciplinary treatment of pelvic pain and endometriosis is offered by trained and experienced pain specialists (Australian Government Department of Health 2018). Such Centres offer advantages to healthcare providers and patients, such as financial incentives by increasing cost efficiencies and the provision of world -lass care by attracting expert clinicians who use innovative tools and techniques to improve patient outcomes, ultimately performing to a higher standard than traditional settings (Elrod & Fortenberry 2017). Centres of Expertise can also offer telehealth to support the needs of individuals in rural and remote communities. Given the financial burden of presentations and hospitalisations for acute and chronic pelvic pain and endometriosis in Australia (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2019), Centres of Expertise for endometriosis represent the logical next step.

Most healthcare professionals, including medical students, are offered minimal training in pain medicine (Shipton et al. 2018). To support the requirements of Centres of Expertise, specialised training in endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain is required. Currently, training models are being offered by The Australian College of Nursing in pelvic pain and endometriosis (Australian College of Nursing (ACN), Undated) and the Pelvic Pain Foundation of Australia provides training via seminars to all health professionals (The Pelvic Pain Foundation of Australia 2021a). The Faculty of Pain Medicine within the Australian and New College of Anaesthetists also offers Pain Medicine fee-based online training for all health professionals consistent with the National Strategic Action Plan for Pain Management (Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists 2021). All health practitioners and carers should be trained in pain management to improve their understanding of pain and associated care plans and practices. Part of the challenge is increasing awareness of these options for health professionals.

Research

While improved access to expert clinicians and interdisciplinary teams is vital, so too are collaborations between universities, research organisations, governments, and businesses in Australia to undertake highly innovative and potentially transformational research. The founding of an Australian Research Council Centre for Excellence or an NHMRC funded Centre for Research Excellence would support interdisciplinary, collaborative approaches to address the most challenging and significant research problems. While such Centres exist for other reproductive health conditions including polycystic ovary syndrome, no such Centres exist for Endometriosis and Pelvic Pain.

Awareness and education

Finally, while awareness of endometriosis and its symptoms is increasing amongst the general population, and this appears to be contributing to the reduction in diagnostic delay (Armour et al. 2020b), overall menstrual health literacy is still relatively low in Australia (Armour et al. 2021b). Therefore, school programmes such as PPEP Talk® are vital, ensuring that parents, a very common source of information on menstruation (Armour et al. 2019b), also have access to accurate, culturally appropriate information so that they can pass this on to their children. In addition, the use of simple screening tools such as PIPPA may encourage young people to seek medical help when needed, rather than feeling their pain is ‘normal’.

Conclusion

The NAPE is an important milestone in the diagnosis and management of endometriosis in Australia however much is left to be done. While the diagnostic delay in Australia is decreasing over time, the emphasis on the need for laparoscopic visualisation as the sole source of diagnosis may be hindering access to vital treatment. Imaging, especially via ultrasound and in the future with artificial intelligence assistance, maybe a key technology that can be enlisted to help reduce this delay. Once diagnosed, access to Centres of Expertise, with highly trained professionals, adequately subsidised by the MBS, and providing interdisciplinary care are crucial steps forward. Given the significant outofpocket cost that endometriosis already exerts, access to adequate symptom management is an important equity issue. Finally, new tools such as PIPPA, and programmes such as PPEP Talk® may help reduce the diagnostic delay further by improving menstrual health literacy and encouraging health-seeking behaviour.

Declaration of interest

Mathew Leonardi is an Associate Editor of Reproduction and Fertility. Mathew Leonardi was not involved in the review or editorial process for this paper, on which he is listed as an author. M A is the Chair of endometriosis Australia’s Research Committee and incoming Chair of the Endometriosis Australia Clinical advisory board. They do not receive any renumeration for this role. L V N is a member of Endometriosis Clinical advisory board. They do not receive any renumeration for this role. M L has received grants from the Australian Women and Children’s Research Foundation and AbbVie, and speaking/writing honoraria from GE Healthcare, Bayer, AbbVie and TerSera, unrelated to the current work. M D is a councillor for the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (RANZCOG). They do not receive any renumeration for this role.

Funding

This work did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sector.

Author contribution statement

All authors were involved in the conceptualisation of the study, M A and S E led the writing of the manuscript with all authors contributing to the first draft, and all authors contributed to, and agreed upon the final manuscript.

References

- Agarwal SK, Antunez-Flores O, Foster WG, Hermes A, Golshan S, Soliman AM, Arnold A, Luna R.2021Real-world characteristics of women with endometriosis-related pain entering a multidisciplinary endometriosis program. BMC Women’s Health 21 19. ( 10.1186/s12905-020-01139-7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armour M, Lawson K, Wood A, Smith CA, Abbott J.2019aThe cost of illness and economic burden of endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain in Australia: a National Online Survey. PLoS ONE 14 e0223316. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0223316) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armour M, Parry K, Al-Dabbas MA, Curry C, Holmes K, MacMillan F, Ferfolja T, Smith CA.2019bSelf-care strategies and sources of knowledge on menstruation in 12,526 young women with dysmenorrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 14 e0220103. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0220103) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armour M, Sinclair J, Chalmers KJ, Smith CA.2019cSelf-management strategies amongst Australian women with endometriosis: a national online survey. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine 19 17. ( 10.1186/s12906-019-2431-x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armour M, Ferfolja T, Curry C, Hyman MS, Parry K, Chalmers KJ, Smith CA, MacMillan F, Holmes K.2020aThe prevalence and educational impact of pelvic and menstrual pain in Australia: a national online survey of 4202 young women aged 13–25 years. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology 33511–518. ( 10.1016/j.jpag.2020.06.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armour M, Sinclair J, Ng CHM, Hyman MS, Lawson K, Smith CA, Abbott J.2020bEndometriosis and chronic pelvic pain have similar impact on women, but time to diagnosis is decreasing: an Australian survey. Scientific Reports 10 16253. ( 10.1038/s41598-020-73389-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armour M, Ciccia D, Stoikos C, Wardle J.2021aEndometriosis and the workplace: lessons from Australia’s response to COVID-19. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 62164–167. ( 10.1111/ajo.13458) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armour M, Hyman MS, Al-Dabbas M, Parry K, Ferfolja T, Curry C, MacMillan F, Smith CA, Holmes K.2021bMenstrual health literacy and management strategies in young women in Australia: a national online survey of young women aged 13–25 years. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology 34135–143. ( 10.1016/j.jpag.2020.11.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armour M, Middleton A, Lim S, Sinclair J, Varjabedian D, Smith CA.2021cDietary practices of women with endometriosis: a cross-sectional survey. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 27771–777. ( 10.1089/acm.2021.0068) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubusson 2019Staring down the barrel of pain and debt: endometriosis’ untold cost. (available at: https://www.smh.com.au/healthcare/staring-down-the-barrel-of-pain-and-debt-endometriosis-untold-cost-20190604-p51ujj.html) [Google Scholar]

- Australian Coalition for Endometrios is (ACE) 2018The Australian coalition for endometriosis. (available at: https://www.acendo.com.au) [Google Scholar]

- Australian College of Nursing (ACN) Undated. Endometriosis and pelvic pain. (available at: https://www.acn.edu.au/education/single-unit-of-study/endometriosis-pelvic-pain) [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government 2021Chronic disease GP management plans and team care arrangements. (available at: https://www.servicesaustralia.gov.au/organisations/health-professionals/topics/education-guide-chronic-disease-gp-management-plans-and-team-care-arrangements/33191) [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government Department of Health 2018National action plan for endometriosis. (available at: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/endometriosis) [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government Department of Health 2021aMBS online. (available at: http://www.mbsonline.gov.au/internet/mbsonline/publishing.nsf/Content/Home) [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government Department of Health 2021bNational strategic action plan for pain management. (available at: https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2021/05/the-national-strategic-action-plan-for-pain-management-the-national-strategic-action-plan-for-pain-management.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government Department of Health 2021cPublications – national action plan. (available at: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications?search_api_views_fulltext=national+action+plan) [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government Department of Health 2021dWhat we’re doing about endometriosis. (available at: https://www.health.gov.au/health-topics/chronic-conditions/what-were-doing-about-chronic-conditions/what-were-doing-about-endometriosis) [Google Scholar]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2019Endometriosis in Australia: prevalence and hospitalisations. (Retrieved from Canberra https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-disease/endometriosis-prevalence-and-hospitalisations) [Google Scholar]

- Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists 2021Pain medicine training program. (available at: https://www.anzca.edu.au/education-training/pain-medicine-training-program) [Google Scholar]

- Australian Prudential Regulation Au thority 2022Quarterly Private Health Insurance Membership Trends. Australia, Sydney: APRA. [Google Scholar]

- Burke2021The cost of endo. (available at: https://www.endometriosisaustralia.org/post/the-cost-of-endo) [Google Scholar]

- Colgrave EM, Keast JR, Bittinger S, Healey M, Rogers PAW, Holdsworth-Carson SJ, Girling JE.2021Comparing endometriotic lesions with eutopic endometrium: time to shift focus? Human Reproduction 362814–2823. ( 10.1093/humrep/deab208) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elrod JK, Fortenberry JL.2017Centers of excellence in healthcare institutions: what they are and how to assemble them. BMC Health Services Research 17 (Supplement 1) 425. ( 10.1186/s12913-017-2340-y) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans S, Villegas V, Dowding C, Druitt M, O’Hara R, Mikocka-Walus A.2021Treatment use and satisfaction in Australian women with endometriosis: a mixed-methods study. Internal Medicine Journal In press. ( 10.1111/imj.15494) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta D, Hull ML, Fraser I, Miller L, Bossuyt PM, Johnson N, Nisenblat V.2016Endometrial biomarkers for the non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 4CD012165. ( 10.1002/14651858.CD012165) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkey A, Chalmers KJ, Micheal S, Diezel H, Armour M.2022‘A day to day struggle’: a comparative qualitative study on experiences of women with endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain. Feminism and Psychology In press. ( 10.1177/09593535221083846) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson NP, Hummelshoj L, Adamson GD, Keckstein J, Taylor HS, Abrao MS, Bush D, Kiesel L, Tamimi R, Sharpe-Timms KL, et al. 2017World endometriosis society Sao Paulo. Human Reproduction 32315–324. ( 10.1093/humrep/dew293) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonardi M, Espada M, Lu C, Stamatopoulos N, Condous G.2019aA novel ultrasound technique called saline infusion SonoPODography to visualize and understand the pouch of Douglas and posterior compartment contents: a feasibility study. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine 383301–3309. ( 10.1002/jum.15022) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonardi M, Martin E, Reid S, Blanchette G, Condous G.2019bDeep endometriosis transvaginal ultrasound in the workup of patients with signs and symptoms of endometriosis: a cost analysis. BJOG 1261499–1506. ( 10.1111/1471-0528.15917) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonardi M, Robledo KP, Espada M, Vanza K, Condous G.2020SonoPODography: a new diagnostic technique for visualizing superficial endometriosis. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology 254124–131. ( 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.08.051) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonardi M, Rocha R, Tun-Ismail AN, Robledo KP, Armour M, Condous G.2021Assessing the knowledge of endometriosis diagnostic tools in a large, international lay population: an online survey. BJOG 1282084–2090. ( 10.1111/1471-0528.16865) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu E, Nisenblat V, Farquhar C, Fraser I, Bossuyt PM, Johnson N, Hull ML.2015Urinary biomarkers for the non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 12CD012019. ( 10.1002/14651858.CD012019) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik A, Sinclair J, Ng CHM, Smith CA, Abbott J, Armour M.2022Allied health and complementary therapy usage in Australian women with chronic pelvic pain: a cross-sectional study. BMC Women’s Health 22 37. ( 10.1186/s12905-022-01618-z) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslen2021‘No financial safety net’. The Crippling Cost of Endometriosis. (available at: https://www.moneymag.com.au/crippling-cost-of-endometriosis) [Google Scholar]

- McKay KJ, Van Niekerk LM, Matthewson ML.2021. An exploration of dyadic relationship approach-avoidance goals and relationship and sexual satisfaction in couples coping with endometriosis. Archives of Sexual Behavior 511, 637–1646. ( 10.1007/s10508-021-02150-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melis I, Litta P, Nappi L, Agus M, Melis GB, Angioni S.2015Sexual function in women with deep endometriosis: correlation with quality of life, intensity of pain, depression, anxiety, and body image. International Journal of Sexual Health 27175–185. ( 10.1080/19317611.2014.952394) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- M embers of the Endometriosis Guideline Core Group, Becker CM, Bokor A, Heikinheimo O, Horne A, Jansen F, Kiesel L, King K, Kvaskoff M, Nap A, Petersen K, et al. 2022. ESHRE guideline: endometriosis. Human Reproduction Open 2022hoac009. ( 10.1093/hropen/hoac009) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moradi M, Parker M, Sneddon A, Lopez V, Ellwood D.2014Impact of endometriosis on women’s lives: a qualitative study. BMC Women’s Health 14 123. ( 10.1186/1472-6874-14-123) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE] 2017Endometriosis: diagnosis and management. (available at: nice.org.uk/guidance/ng73) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NHMRC 2021Research funding statistics and data. (available at: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/funding/data-research/research-funding-statistics-and-data) [Google Scholar]

- Nisenblat V, Bossuyt PM, Farquhar C, Johnson N, Hull ML.2016aImaging modalities for the non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2CD009591. ( 10.1002/14651858.CD009591.pub2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisenblat V, Bossuyt PMM, Shaikh R, Farquhar C, Jordan V, Scheffers CS, J Mol BM, Johnson N, Hull ML.2016bBlood biomarkers for the non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 5CD012179. ( 10.1002/14651858.CD012179) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisenblat V, Prentice L, Bossuyt PM, Farquhar C, Hull ML, Johnson N.2016cCombination of the non-invasive tests for the diagnosis of endometriosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 7CD012281. ( 10.1002/14651858.CD012281) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nnoaham KE, Hummelshoj L, Webster P, d’Hooghe T, de Cicco Nardone F, de Cicco Nardone C, Jenkinson C, Kennedy SH, Zondervan KT. & World Endometriosis Research Foundation Global Study of Women ’ s Health consortium 2011Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and work productivity: a multicenter study across ten countries. Fertility and Sterility 96366, .e8–373.e8. ( 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.05.090) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara R, Rowe H, Roufeil L, Fisher J.2018Should endometriosis be managed within a chronic disease framework? An analysis of national policy documents. Australian Health Review 42627–634. ( 10.1071/AH17185) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara R, Rowe H, Fisher J.2020Managing endometriosis: a cross-sectional survey of women in Australia. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology . ( 10.1080/0167482X.2020.1825374) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker MA, Kent AL, Sneddon A, Wang J, Shadbolt B.2021. The menstrual disorder of teenagers (MDOT) study no. 2: period impact and pain assessment (PIPPA) tool validation in a large population-based cross-sectional study of australian teenagers. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology 3530–38. ( 10.1016/j.jpag.2021.06.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulos C, Soliman AM, Renz CL, Posner J, Agarwal SK.2019Patient preferences for endometriosis pain treatments in the United States. Value in Health 22728–738. ( 10.1016/j.jval.2018.12.010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RANZCOG 2020Raising awareness tool for endometriosis (RATE). (available at: https://ranzcog.edu.au/womens-health/patient-information-guides/other-useful-resources/rate) [Google Scholar]

- RANZCOG 2021Australian clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of endometriosis. (available at: https://ranzcog.edu.au/RANZCOG_SITE/media/RANZCOG-MEDIA/Women%27s%20Health/Statement%20and%20guidelines/Clinical%20-%20Gynaecology/Endometriosis-clinical-practice-guideline.pdf?ext=.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- Roomaney R, Kagee A.2018Salient aspects of quality of life among women diagnosed with endometriosis: a qualitative study. Journal of Health Psychology 23905–916. ( 10.1177/1359105316643069) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowlands IJ, Abbott JA, Montgomery GW, Hockey R, Rogers P, Mishra GD.2021Prevalence and incidence of endometriosis in Australian women: a data linkage cohort study. BJOG 128657–665. ( 10.1111/1471-0528.16447) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipton EE, Bate F, Garrick R, Steketee C, Visser EJ.2018Pain medicine content, teaching and assessment in medical school curricula in Australia and New Zealand. BMC Medical Education 18 110. ( 10.1186/s12909-018-1204-4) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoens S, Dunselman G, Dirksen C, Hummelshoj L, Bokor A, Brandes I, Brodszky V, Canis M, Colombo GL, DeLeire T, et al. 2012The burden of endometriosis: costs and quality of life of women with endometriosis and treated in referral centres. Human Reproduction 271292–1299. ( 10.1093/humrep/des073) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair J, Smith CA, Abbott J, Chalmers KJ, Pate DW, Armour M.2019Cannabis use, a self-management strategy among Australian women with endometriosis: results from a national online survey. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada 42256–261. ( 10.1016/j.jogc.2019.08.033) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surrey E, Soliman AM, Trenz H, Blauer-Peterson C, Sluis A.2020Impact of endometriosis diagnostic delays on healthcare resource utilization and costs. Advances in Therapy 371087–1099. ( 10.1007/s12325-019-01215-x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Pelvic Pain Foundation of Australia 2021aHealth practitioner training seminars. (available at: https://www.pelvicpain.org.au/health-practitioner-pelvic-pain-training-seminars/) [Google Scholar]

- The Pelvic Pain Foundation of Australia 2021bPPEP talk. (available at: https://www.pelvicpain.org.au/ppep-talk-schools-program/) [Google Scholar]

- Van Niekerk LM, Schubert E, Matthewson M.2021Emotional intimacy, empathic concern, and relationship satisfaction in women with endometriosis and their partners. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology 4281–87. ( 10.1080/0167482X.2020.1774547) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson R, Wynn-Williams M, Jung A, Berryman J, Wilson E.2021Impact of a persistent pelvic pain clinic: emergency attendances following multidisciplinary management of persistent pelvic pain. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 61612–615. ( 10.1111/ajo.13358) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young K, Fisher J, Kirkman M.2016Endometriosis and fertility: women’s accounts of healthcare. Human Reproduction 31554–562. ( 10.1093/humrep/dev337) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a