Abstract

The wbp cluster of Pseudomonas aeruginosa O5 encodes a number of proteins involved in biosynthesis of the heteropolymeric and Wzy-dependent B-band O antigen, including Wzy, the O-antigen polymerase, and Wzz, the regulator of O-antigen chain length. A gene (formerly wbpF), contiguous with wzy in the wbp cluster, is predicted to encode a highly hydrophobic protein with multiple membrane-spanning domains. This secondary structure is consistent with that of Wzx (RfbX), the putative O-antigen unit translocase or “flippase.” Insertion of a Gmr cassette at two separate sites within the putative wzx gene led in both cases to the loss of B-band lipopolysaccharide (LPS) O-antigen production. To our knowledge, this is the first report of the successful generation of chromosomal wzx gene replacement mutations. Surprisingly, inactivation of wzx also led to a marked delay in production of the ATP-binding cassette–transporter-dependent, d-rhamnose homopolymer, A-band LPS. This effect on A-band LPS synthesis was alleviated by supplying multiple copies of WbpL in trans. WbpL, a WecA (Rfe) homologue, was shown recently to be essential for the initiation of both A-band and B-band LPS synthesis in P. aeruginosa O5 (H. L. Rocchetta, L. L. Burrows, J. C. Pacan, and J. S. Lam, Mol. Microbiol. 28:1103–1119, 1998). These results suggest that the delay in A-band LPS production may arise from insufficient access to WbpL when the completed B-band O unit is not successfully translocated to the periplasm. Without adequate WbpL, A-band LPS synthesis is delayed. A subset of wzx mutants appeared to have accumulated second-site mutations which either restored the normal expression of A-band LPS or abolished A-band expression completely. Complementation studies showed that all of the additional mutations affecting LPS synthesis that were characterized in this study were located within the B-band LPS genes.

Current models explaining the biosynthesis and assembly of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) O antigens invoke two separate pathways, termed the Wzy (Rfc)-dependent and the Wzy-inde-pendent–ATP-binding cassette (ABC)–transporter-depen-dent pathways (reviewed in reference 36). Wzy is the O-antigen polymerase and is involved in the biosynthesis of heteropolymeric O antigens. Two other proteins required in the Wzy-dependent pathway are Wzx (RfbX), the putative O-antigen unit translocase or “flippase,” and Wzz (Rol, Cld), the regulator of O-antigen chain length (36). Individual O-antigen sugar units are synthesized on the isoprenoid lipid carrier undecaprenol phosphate (C55P) at the cytoplasmic face of the inner membrane. Following synthesis, individual O-antigen units are thought to be translocated by an integral membrane protein, Wzx, to the periplasmic face of the cytoplasmic membrane, where they are polymerized by Wzy (25, 36). The chain length of the growing heteropolymer is controlled by the Wzz protein (3, 4, 7, 28) via an unknown mechanism. The heteropolymer is then covalently attached to the previously synthesized core lipid A by the O-antigen ligase, encoded by waaL (rfaL) in Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium.

In contrast, homopolymeric O antigens appear to be synthesized processively on C55P without an O-antigen polymerase (36). Most homopolymeric O antigens are transported via a two-component, ABC-type transporter, which moves the assembled homopolymer across the cytoplasmic membrane (19, 29, 36). Once the homopolymer has been translocated to the periplasmic face of the cytoplasmic membrane, it can be ligated to core lipid A by the O-antigen ligase. Recently, an alternative transport mechanism for the O:54 homopolymer of Salmonella enterica serovar Borreze was proposed, in which the O antigen is assembled and transported across the cytoplasmic membrane in the absence of an ABC transporter (18).

Pseudomonas aeruginosa simultaneously produces two forms of LPS, called A-band and B-band LPS. A-band LPS contains a neutral homopolymer of α-d-rhamnose (23). The A-band biosynthetic cluster has been cloned and sequenced and has been shown to contain genes encoding a typical two-component transporter system (29). B-band LPS is the O-antigen-containing form and is a heteropolymer of di- to pentasaccharides, containing uronic acids and very rare sugars, such as pseudaminic acid (20). The wbp cluster encoding the biosynthesis of the B-band O antigen of serotype O5 has been cloned and sequenced (6, 7, 24). It resembles other gene clusters encoding the synthesis of heteropolymeric O antigens in that it contains wzx, wzy, and wzz homologues. The wzy and wzz genes from serotype O5 have previously been characterized in our lab (7, 9). The start codon of the putative wzx gene (formerly wbpF) overlaps the stop codon of wzy (6). Analysis of the deduced amino acid sequence of Wzx showed that it is a hydrophobic protein with multiple membrane-spanning domains in its predicted secondary structure, similar to that of other Wzx proteins. Homologues of wzx have been identified in many bacterial species in both LPS O-antigen and capsular biosynthetic clusters (37). While the primary sequence homologies of Wzx from different bacteria can be poor, the proteins share similar secondary structures. Wzx has not been extensively studied, probably due to obstacles encountered during the cloning of the gene in isolation and creation of null mutants (25, 26). Chromosomal mutations in wzx have been described as deleterious and difficult to study (31). However, Liu and coworkers (25) were able to use a plasmid-encoded O-antigen cluster carrying a nonpolar transposon insertion in wzx to demonstrate that wzx mutants appear to accumulate O-antigen units on the cytoplasmic face of the inner membrane.

In this study, we examined the function of Wzx in P. aeruginosa O5 through the creation of chromosomal wzx knockout mutants. As far as we are aware, this is the first report of the successful generation of such mutants. Analysis of these knockout strains confirmed the involvement of Wzx in B-band LPS biosynthesis and helped define the interrelationship between the Wzy-dependent and the Wzy-independent pathways of O-antigen biosynthesis in P. aeruginosa O5.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. P. aeruginosa strains were grown either on Pseudomonas isolation agar (Difco), Luria broth and agar (Sigma), or Davis minimal medium (Fisher). E. coli strains were grown on Luria broth and agar (Sigma). Where necessary, antibiotics (all from Sigma) were added as described previously (9).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype, phenotype, or properties | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| P. aeruginosa | ||

| O5 | Strain PAO1, wild type A+ B+ | 15 |

| O5 wzxs S2 | PAO1, wzx insertion mutation at SstI; AL B− | This study |

| O5 wzxs S7 | PAO1, wzx insertion mutation at SstI; A+ B− | This study |

| O5 wzxx X10 | PAO1, wzx insertion mutation at XhoI; AL B− | This study |

| O5 wzxx X6 | PAO1, wzx insertion mutation at XhoI; A− B− | This study |

| O5 wzxx X14 | PAO1, wzx insertion mutation at XhoI; A− B− | This study |

| O5 wzxx X24 | PAO1, wzx insertion mutation at XhoI; A+ B− | This study |

| E. coli | ||

| JM109 | recA1 supE44 endA1 hsdR17 gyrA96 relA1 thi Δlac-proAB F′[traD36 proAB+ lacIqlacZΔM15] | 39 |

| SM10 | thi-1 thr leu tonA lacY supE recA RP4-2-Tc::Mu, Kmr | 35 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUCP26 | 4.9-kb pUC18-based broad-host-range vector; Tcr | 36 |

| pEX100T | Gene-replacement vector; oriT+ sacB+; Apr | 34 |

| pUCGM | Source of Gmr cassette; Apr Gmr | 31 |

| pAK1900 | 4.75-kb pGEM3Zf(+)-based vector with pRO1600 oriR, Apr | A. Kropinski |

| pFV155T | 5.2-kb HindIII insert containing wzy, wzx, hisHF, wbpG blunt-cloned in SmaI site of pEX100T | This study |

| pFV155TG | pFV155T with Gmr cassette in unique SstI site within wzx | This study |

| pFV162-26 | 3.1-kb BamHI-BglII insert containing wzx, hisHF in pUCP26 under lac promoter | 6 |

| pFV162-26G | pFV162-26 with Gmr cassette in unique XhoI site within wzx | This study |

| pFV162-26TG | Insert of pFV162-26G blunt cloned into SmaI site of pEX100T | This study |

| pFV110 | 1.4-kb HindIII-XbaI insert containing wbpL in pAK1900 | 8 |

| pFV114 | 10.5-kb SpeI insert containing wzx through wbpL in pAK1900 | This study |

DNA manipulations.

Chromosomal DNA was isolated from P. aeruginosa using the method of Goldberg and Ohman (13). Plasmid DNA was isolated by using the Qiagen midi-prep or mini-plasmid kits (Qiagen Inc.) as directed by the manufacturer. Restriction and modification enzymes were used as directed by the manufacturers.

Plasmids were introduced into E. coli by CaCl2 transformation (17) and into P. aeruginosa by electroporation using a Bio-Rad (Richmond, Calif.) Gene Pulser apparatus following the manufacturer’s protocols. Electrocompetent cells of P. aeruginosa were prepared by growing the cells to mid-log phase in Luria broth and then washing the cells twice for 5 min each in sterile 10% room temperature glycerol followed by immediate resuspension in the same solution. Cells were either used immediately or frozen at −80°C for future use. Plasmids were also introduced into P. aeruginosa by biparental mating with E. coli SM10 carrying mobilizable plasmids of interest (34).

Creation of isogenic chromosomal knockout mutants.

The gene replacement strategy of Schweizer and Hoang (33) was used for the creation of knockout mutations in wzx as described previously (8, 9). In the event that isolates were obtained in which only single crossover events had occurred, these merodiploids were plated overnight at 37°C on modified Luria medium containing 5% sucrose and no NaCl (38). This treatment selects for cells which have lost the sacB-containing vector DNA following a double crossover event that generates true recombinants. Correct gene replacement was ascertained through Southern blot analysis of chromosomal DNA isolated from gentamicin-resistant, sucrose-sensitive, carbenicillin-sensitive mutants.

A similar strategy was used to create a double knockout mutant. An AL (for A late) wzx strain, S2, was used as the background for the introduction via electroporation of a copy of wbpM (6) inactivated by a nonpolar carbenicillin resistance cassette, and cloned into the sacB-containing suicide vector pEX18Tc (pFV169-18TcCb) (16). Correct gene replacement was ascertained by Southern blot analysis of chromosomal DNA from gentamicin-resistant, carbenicillin-resistant, sucrose-sensitive, tetracycline-sensitive mutants.

Southern blot analysis.

Restriction-enzyme-digested chromosomal DNA was separated on 0.8% agarose gels, transferred to Zetaprobe nylon membrane (Bio-Rad) by capillary transfer, and crosslinked to the membrane using a Stratalinker (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). For detection of specific fragments, probe DNA was labelled with digoxigenin-dUTP (Boehringer Mannheim, Laval, Quebec, Canada), and hybridization and detection were performed according to the manufacturer’s directions.

SDS-PAGE and Western immunoblot analysis.

LPS from P. aeruginosa was prepared by the method of Hitchcock and Brown (15). The LPS preparations were separated on standard discontinuous sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–12% polyacrylamide gels and visualized by silver staining using the method of Dubray and Bezard (11). For immunoblotting, LPS separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) was transferred to nitrocellulose (5). Nitrocellulose blots were blocked with 3% skim milk followed by overnight incubation with hybridoma culture supernatants containing monoclonal antibody (MAb) MF15-4 (specific for O5 B-band LPS) (21) or MAb N1F10 (specific for A-band LPS) (22). A goat anti-mouse F(ab′)2-alkaline phosphatase second antibody conjugate (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, Pa.) was used to detect the first antibody. The blots were developed using a substrate containing 0.3 mg of Nitro Blue Tetrazolium/ml and 0.15 mg of BCIP (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate toluidine)/ml in 0.1 M bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.8).

Time course experiments.

Growth curves of strains PAO1, S2, and X10 showed that there were no significant differences in the rates of growth of the parent and mutant strains (not shown). To demonstrate the appearance of A-band LPS over time, the mutant and parent strains were grown in 50 ml of Luria broth at 37°C with 200-rpm shaking. Aliquots of 0.5 ml were removed beginning at 12 h after inoculation (early stationary phase) and then at 6- to 12-h intervals up to 60 h postinoculation, and the optical densities at 600 nm of the samples were determined. The cells were harvested and used to prepare LPS via the method of Hitchcock and Brown (15). The LPS was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western immunoblotting as outlined above.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The corrected DNA sequence of the wzx gene is available from GenBank under accession no. U50396.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Characterization of Wzx.

In a previous study (6), we reported Wzx (formerly WbpF) to be 316 amino acids (aa) long, a length inconsistent with those of other Wzx proteins, which range from approximately 400 to 500 aa. Reanalysis of the DNA sequence in the region containing wzx showed the actual size of the wzx gene to be 1,236 bp. This open reading frame is predicted to encode a protein of 411 aa, in agreement with the sizes of other Wzx proteins.

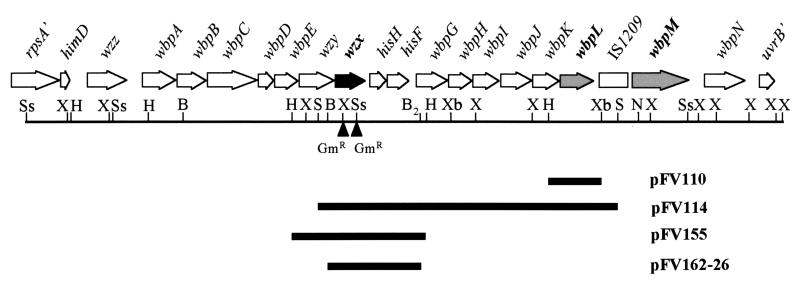

Repeated attempts to express Wzx by both in vivo and in vitro methods were not successful, although the HisH and HisF proteins encoded immediately downstream of wzx (Fig. 1) and on the same recombinant plasmid (pFV162-26) were readily expressed (6). Our observations are consistent with previous reports that the high hydrophobicity and presence of rare or modifying codons within the coding regions for Wzx and Wzy proteins make them extremely difficult to express using currently available methods (9, 26, 27).

FIG. 1.

Physical map of locations of plasmids used in this study with respect to the B-band LPS gene cluster. The individual open reading frames within the wbp cluster of serotype O5 are shown as arrows at the top of the figure. The wzx gene described in this study is shown in black, while the wbpL and wbpM genes are shown in grey. The positions of the two individual Gmr cassette insertions within the wzx gene are shown as black triangles. Mutants with an insertion at SstI are designated wzxs, while mutants with an insertion at XhoI are designated wzxx. B, BamHI; B2, BglII; H, HindIII; N, NruI; S, SalI; Ss, SstI; X, XhoI; Xb, XbaI. For clarity, only selected restriction sites are shown.

Analysis of chromosomal wzx mutants.

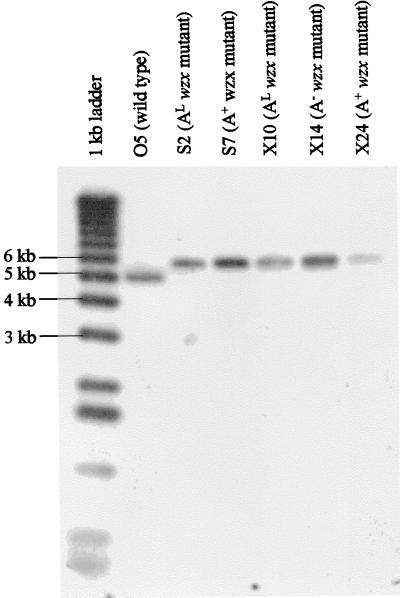

In order to demonstrate the function of Wzx in P. aeruginosa O-antigen biosynthesis, a nonpolar Gmr cassette was used to insertionally inactivate the wzx gene of serotype O5. The first set of wzx mutants constructed had a gentamicin cassette inserted at a unique SstI site located 462 bp from the 3′ end of the gene (wzxs; Fig. 1). However, there were concerns that insertion of the Gmr cassette near the 3′ end of the gene may have led to the generation of a truncated but potentially functional peptide. This consideration prompted the construction of a second set of wzx mutants. The second group, wzxx, had the nonpolar Gmr cassette inserted in a XhoI site 200 bp from the 5′ end of wzx (Fig. 1). In our hands, the yield of both types of wzx mutants compared to that obtained for other P. aeruginosa LPS genes using the same methodology was very low (6, 7, 9, 29, 30). The poor yield is consistent with the reported difficulties encountered by others during attempts to isolate such mutants (25, 26). Correct insertion of the gentamicin resistance cassette within wzx in both sets of mutants was confirmed by Southern immunoblot analysis (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Southern blot analysis of selected wzx mutants. Chromosomal DNA from representative AL (S2 and X10) and A+ (S7 and X24) wzx mutants from the wzxs and wzxx series and a representative A− (X14) wzxx mutant was digested with HindIII and separated on a 0.8% agarose gel, transferred to a nylon membrane, and probed with a dUTP-digoxigenin-labelled BamHI-BglII fragment corresponding to the insert of pFV162-26. All mutants show an increase in the size of the HindIII fragment of approximately 0.9 kb, corresponding to the size of the Gmr cassette. No gross rearrangements that could be responsible for the varied A-band LPS phenotypes of these mutants were found in this region.

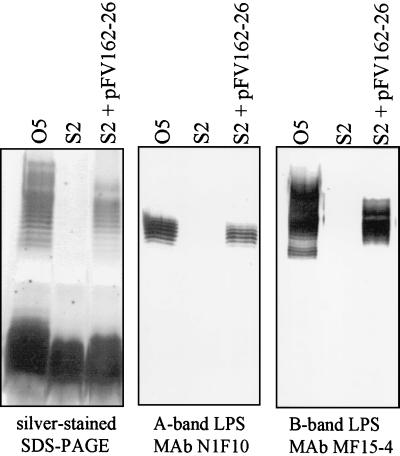

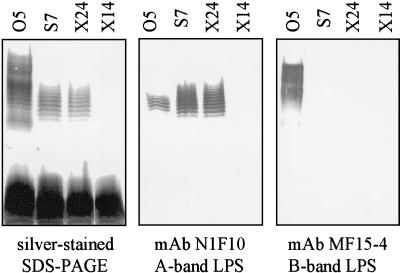

On silver-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gels, the gentamicin-resistant wzxs mutants were devoid of B-band LPS (Fig. 3). Interestingly, of 21 wzxs mutants generated, 20 also lacked the ladder-like banding pattern typical of A-band LPS on silver-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gels. This result was confirmed using MAb N1F10, which is specific for A-band LPS (Fig. 3). This is the first instance in which mutation of a wzx gene has been shown to affect synthesis of a Wzy-independent, homopolymeric polysaccharide. Similar results were obtained for the wzxx set of mutants (not shown).

FIG. 3.

Analysis of LPS from a representative AL wzxs mutant, S2. LPS isolated from 12-h cultures of the AL wzxs mutant S2 and from the O5 parent strain was analyzed with silver-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gels as well as by Western immunoblotting with LPS-specific antibodies. The mutant produced no detectable A-band or B-band LPS. Complementation with pFV162-26 (wzx, hisHF; Fig. 1) restored both A- and B-band LPS biosynthesis.

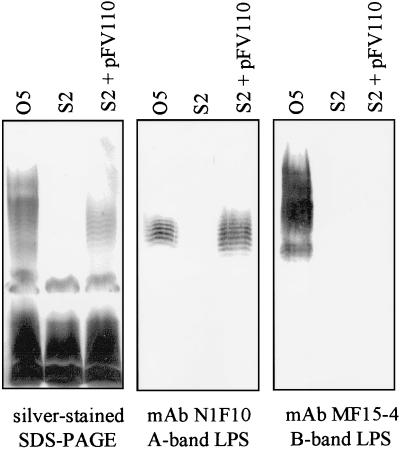

Production of A-band LPS is delayed in wzx mutants.

During analysis of the wzxs mutants, we noted that LPS preparations made from fresh overnight plates contained no detectable A-band LPS on silver-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gels or Western immunoblots. In contrast, preparations made from plates that were several days old appeared to have substantial amounts of A-band LPS. This delay in A-band LPS production was reproducible and occurred in cultures grown on solid media (both Luria agar and Pseudomonas isolation agar) as well as in broth. Strains which displayed this phenotype were designated AL to distinguish them from those which were truly A−.

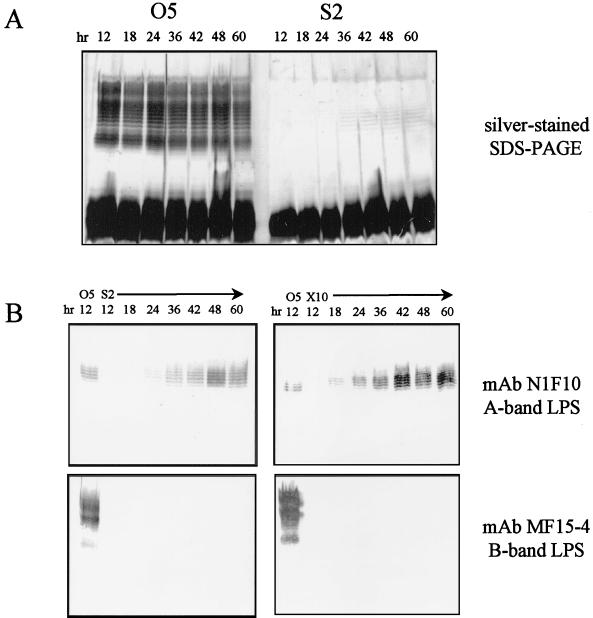

Analysis of LPS production by AL wzxs mutants over time compared with the parent strain PAO1 was performed. Comparison of the growth rates of the parent and a representative AL wzxs mutant (S2) showed no significant differences (not shown). While the parent strain had substantial amounts of both A- and B-band LPS after 12 h of growth, the S2 mutant produced only rough LPS (core-lipid A) with no detectable A band or B band (Fig. 4). After 18 to 24 h, A-band LPS became detectable in the preparations from the S2 culture (Fig. 4). In contrast, no B-band LPS could be detected at any time during the experiment.

FIG. 4.

Analysis of the production of A-band LPS over time. (A) LPS was harvested from the O5 parent strain and from the AL mutant wzxs S2 as described in Materials and Methods and analyzed on silver-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gels. While the parent strain (O5) produced substantial amounts of both A- and B-band LPS after 12 h of growth, the S2 mutant produced no perceptible amounts of either LPS after 12 h of growth. After 24 to 36 h of growth, the mutant produced sufficient A-band LPS to be detectable on silver-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gels. (B) Western immunoblot analysis of LPS from the AL wzx mutants S2 (wzxs) and X10 (wzxx) using LPS-specific MAbs. In comparison with 12-h cultures of the parent strain (O5), which contain both A- and B-band LPS, 12-h cultures of S2 and X10 contain no detectable A- or B-band LPS. A-band LPS is detectable after 18 to 24 h of growth, while no B-band LPS could be detected over the duration of the experiment. The effect of both mutations in wzx appears to be the same.

As mentioned above, our concern that production of a truncated but partially functional Wzx protein by wzxs mutants was somehow responsible for the AL phenotype was addressed through generation and analysis of the wzxx series of mutants. Analysis of the LPS produced by wzxx mutants on silver-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gels showed that of 39 mutants obtained, none produced B-band LPS, and the majority produced little or no A-band LPS after 12 h of growth. Results from a time course experiment similar to the one described above showed that, again, the amount of A-band LPS produced by a representative wzxx mutant (X10) increased over time from undetectable to substantial (Fig. 4).

Analysis of atypical A+ or A− wzx mutants.

In contrast to the AL wzx mutants described above, a subset of wzx mutants (1 of 21 wzxs and 4 of 39 wzxx mutants) produced substantial amounts of A-band LPS during all phases of growth (representative mutants are shown in Fig. 5). In addition, at least 3 of 39 wzxx mutants produced no A-band LPS at all, even upon prolonged incubation (Fig. 5). These two types of wzx mutants were designated A+ and A−, respectively. Despite the difference in A-band phenotype among the wzx mutants, Southern blot analysis of representative strains showed no gross rearrangements in ∼5 kb of DNA encompassing the site of the insertional mutation (Fig. 2). The synthesis of A-band LPS by both the AL (after prolonged growth) and the A+ wzx mutants confirmed that Wzx is not directly necessary for A-band LPS synthesis. Therefore, the mere lack of Wzx could not explain the deficiency in A-band LPS biosynthesis in AL (during early growth phases) and A− wzx mutants.

FIG. 5.

Analysis of LPS from atypical wzx mutants. LPS from representative wzx mutants which either produced A-band LPS without delay (wzxs mutant S7 and wzxx mutant X24) or produced no A-band LPS even after prolonged growth (wzxx mutants X6 and X14) was analyzed on silver-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gels and Western immunoblots using LPS-specific MAbs. The LPS from the O5 parent strain, S7, and X24 was prepared from 12-h cultures, while the LPS from the X6 and X14 cultures was prepared from 36-h cultures. None of the mutants made B-band LPS at any point during growth.

The delay in A-band LPS expression in AL strains was thought to be due to the reduction in some component required for production of both types of LPS, stemming from the interruption in B-band LPS synthesis. A-band and B-band LPS have clearly been shown to be synthesized by different pathways (7, 9, 29). However, there are components shared by both pathways. Recently, we showed that WbpL, which initiates synthesis of B-band LPS by transferring N-acetyl-6-deoxygalactosamine-1-P (Fuc2NAc-1-P) to C55P (6), is also required to initiate the synthesis of A-band LPS (30). WbpL is a homologue of E. coli WecA (Rfe), an enzyme that initiates the synthesis of enterobacterial common antigen and a variety of O antigens through the addition of N-acetylglucosamine-1-P (GlcNAc-1-P) to C55P. In the case of homopolymeric O antigens, including A-band LPS, the residue added by WecA-WbpL acts solely as a primer and does not become part of the O repeat unit (36). WbpL and WecA were both able to initiate the synthesis of A-band LPS in a wbpL::Gmr mutant of P. aeruginosa O5, likely through the addition of GlcNAc-1-P to C55P (30).

We postulated that the interruption of B-band biosynthesis after formation of the O-antigen unit, but prior to its translocation, might in some way affect the availability of WbpL. A reduction in the availability of WbpL would hinder the initiation of A-band polymer synthesis, generating the AL phenotype. Alternatively, the introduction of errors or rearrangements in the putative operon wbpG-wbpL, following the recombination events required to generate the knockout mutant, could have polar effects on the expression of wbpL. The latter prospect is less likely, since a number of individual wzx mutants with an AL phenotype, each presumably arising from unique recombination events, were isolated. In addition, Southern blot analyses of the wzy-wbpG region in which the recombination events occurred show that there are no gross rearrangements (Fig. 2), suggesting that polar effects are unlikely to be the cause of the AL phenotype.

The growth rates of AL wzx mutants (which do not appear to have acquired additional mutations affecting LPS biosynthesis) do not seem adversely affected (not shown), as one might expect of cells with insufficient free C55P to support normal peptidoglycan synthesis. However, based on the potentially deleterious nature of wzx mutations, it is possible that those mutants eventually isolated already contain compensatory mutations that permit them to grow in the presence of the wzx mutation.

The delay in A-band LPS production is alleviated by supplying WbpL in trans.

To test the hypothesis that the availability of WbpL was limiting in AL cells, we transformed AL wzxs mutant S2 with a high-copy-number plasmid carrying the serotype O5 wbpL gene under the control of the lac promoter (pFV110). If insufficient WbpL is available in AL cells, provision of excess WbpL in trans should mitigate the delay in A-band LPS expression. Analysis of LPS from S2 transformed with pFV110 (wbpL) showed that the presence of the plasmid restored the ability of S2 to produce A-band LPS without delay (Fig. 6). Interestingly, the A− wzx mutant randomly chosen for further analysis (X14) appears to have a secondary mutation affecting wbpL, since it was rendered A+ by the addition of pFV110 (wbpL) alone (see below).

FIG. 6.

Alleviation of the AL phenotype by wbpL in trans. The AL wzxs mutant S2 was transformed with pFV110, a high-copy-number plasmid containing wbpL (Fig. 1). Analysis of LPS from 12-h cultures of the transformants showed that they were producing A-band LPS without delay, suggesting WbpL was limiting in S2.

From these data, it appears that A-band biosynthesis per se is not impeded by the wzx mutation and that WbpL is expressed and functional in AL wzx mutants, since A-band LPS can eventually be detected. Typically, some WbpL molecules would initiate A-band LPS biosynthesis; however, the frequency of the initiation event likely relies upon the number of WbpL molecules available. Possible explanations for the AL phenotype include a reduction in the amount of wbpL expression in wzx mutants, a decrease in the normal rate of initiation of A-band LPS, possibly due to the presence of B-band O units on C55P, or interference with normal WbpL function or availability. We are currently analyzing the transcription of the wbpG-wbpL operon in both PAO1 and S2 to explore the first possibility. However, provision of wbpL expressed in multicopy from an unregulated promoter could overcome any of these difficulties.

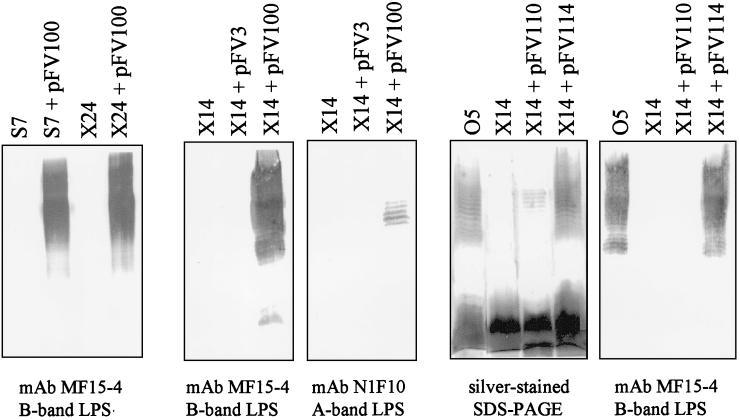

Complementation analysis of wzx A+ and A− mutants.

We thought that emergence of A+ or A− derivatives of wzx mutants could be due to the selection for strains with spontaneous secondary mutations in genes necessary for LPS biosynthesis, perhaps due to a reduction in free C55P. Liu and coworkers (25) showed that wzx mutants appeared to accumulate a single O-antigen unit on C55P. In P. aeruginosa, interruption of B-band biosynthesis after formation of the O-antigen unit, but prior to its translocation, may cause C55P to be sequestered. Removal of C55P from the cellular pool would be deleterious for other cell functions, such as peptidoglycan formation. The strong pressure to overcome the reduction in availability of C55P may lead to accumulation of second-site mutations. The most likely sites for such mutations would be in the B-band O-antigen genes or in housekeeping pathways which feed into LPS synthesis in order to prevent formation of the B-band O unit altogether. For example, a second-site mutation in the B-band cluster would prevent formation of the O-antigen unit on C55P, allowing the synthesis of A-band LPS to continue normally (A+ cells) in the presence of the wzx mutation (unless they occurred within wbpL itself).

In support of this hypothesis, a number of wzx mutants with A-band LPS expression atypical of a wzx mutant were isolated. This subset included five A+ wzx mutants and at least three A− wzxx mutants, examples of which are shown in Fig. 5. The inability to complement either A+ or A− wzx mutants using pFV162-26 (wzx) alone, a construct that rendered isogenic AL wzx strains A+B+, confirmed that A+/A− strains had likely accumulated additional mutations leading to loss of expression of A band, B band, or both.

Complementation of the atypical strains with the entire gene clusters necessary for either A- or B-band biosynthesis identified the B-band LPS genes as the site of secondary mutations. Introduction of pFV3 (23), carrying the A-band LPS biosynthetic genes, into the A− wzx mutant X14 was not able to restore A-band biosynthesis, locating its secondary mutation(s) elsewhere (Fig. 7). In contrast, pFV100 (6, 24) carrying the wbp (B-band) gene cluster could restore B-band LPS biosynthesis in both A+ and A− wzx mutants as well as A-band synthesis in the wzx A− mutant (Fig. 7). These results imply that, in these mutants, a secondary mutation(s) affecting LPS biosynthesis was in the B-band genes. Further analysis showed that the A− wzx mutant X14 could be complemented to A+B+ by pFV114 (Fig. 1), which contains both wzx and wbpL, and to A+ but not B+ by pFV110, containing wbpL (Fig. 7). Taken together, these results show that X14 contains the original wzx mutation as well as a secondary mutation in wbpL.

FIG. 7.

Complementation analysis using atypical wzx mutants. Complementation of representative A+ and A− wzx mutants with cosmid clones containing the A-band (pFV3) (23) and B-band (pFV100) (6, 24) LPS gene clusters. None of these mutants could be complemented to A+B+ by pFV162-26 (not shown). However, pFV100 complements both A-band (in the A− wzx mutant) and B-band synthesis (in all mutants), showing that these wzx::Gmr strains contain an additional mutation(s) affecting LPS synthesis that maps within the B-band genes. The A− wzx mutant X14 could be rendered A+ by pFV110 (containing wbpL) (Fig. 1), implying that it contains mutations within, or polar upon, wbpL. pFV110 cannot complement the original wzx::Gmr mutation, so the cells remain B−. Complementation of X14 with pFV114 (wzx through wbpL) (Fig. 1) restores it to A+B+.

Generation of double knockout mutants.

We attempted to replicate the phenotype of A+ wzx mutants by introducing a second knockout mutation of the B-band LPS biosynthetic genes into an AL wzx mutant, S2. We reasoned that prevention of synthesis of the first sugar of the O unit, Fuc2NAc, would prevent accumulation of any material on C55P. The highly conserved gene, wbpM, that lies at the 3′ end of the B-band LPS gene cluster is implicated in Fuc2NAc biosynthesis (6). The wbpM gene was inactivated with a nonpolar carbenicillin resistance cassette, and the resulting construct was introduced into the chromosome of the AL wzx mutant, S2.

The PAO1 parent strain, the AL wzx strain (S2), and the S2 wbpM::Cbr mutants were grown for 12 h (the time point at which S2 had no detectable A-band LPS; Fig. 4). LPS was prepared by the method of Hitchcock and Brown (15) and examined on silver-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gels and Western immunoblots with LPS-specific MAbs. Introduction of the wbpM::Cbr mutation was not able to relieve the AL phenotype of the S2 mutant (not shown). This result may mean that the atypical A+ and A− wzx mutants did not arise from an AL wzx background. Alternatively, since the function of WbpM in Fuc2NAc biosynthesis has not yet been ascertained, it may not be the appropriate target for inactivation in order to recreate the A+ wzx phenotype from an AL wzx mutant.

With the exception of ABC-type transporters (19, 29), the identification and analysis of components of the LPS transport machinery have proven to be complicated. Problems related to the low copy number and integral membrane location of transport proteins and the deleterious effects on cell growth caused by their mutation (31) have hampered elucidation of this aspect of LPS biosynthesis. Despite the precedent, we have successfully generated wzx chromosomal knockout mutants and did not experience the reported difficulties encountered during attempts to clone wzx in the absence of other LPS genes (26).

P. aeruginosa is a unique model system in which two forms of LPS with independent pathways of biosynthesis are coproduced. The only analogous system that has been studied in enterics involves the concomitant production of a homopolymeric O8 or O9 O antigen with a heteropolymeric lipid A-core-linked “capsular” exopolysaccharide in E. coli (called KLPS) (2, 10, 12). Although a wzx homologue has been identified in the K40 cluster of E. coli O8 and both polymers are WecA dependent (2), wzx mutants are not yet available (1). Therefore, it is not clear whether a wzxK40 mutation would affect production of the O8 or O9 O antigens.

This study has demonstrated that wzx is essential in the synthesis of the heteropolymeric B-band O antigen of P. aeruginosa O5 and that its mutation can affect the synthesis of the homopolymer, A band. In addition, the key role of WbpL in initiation of both A- and B-band synthesis has been reemphasized. By generating chromosomal wzx mutants, we have laid the foundation for understanding the role of Wzx in translocation of O units and the effect of wzx mutations on the activities of the initial glycosyltransferase, WbpL.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding for the study was provided to J.S.L. from the Medical Research Council of Canada (grant MT14687). L.L.B. is the recipient of a Canadian Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Fellowship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amor, P. A. Personal communication.

- 2.Amor P A, Whitfield C. Molecular and functional analysis of genes required for expression of group IB K antigens in Escherichia coli: characterization of the his-region containing gene clusters for multiple cell-surface polysaccharides. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:145–161. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5631930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bastin D A, Stevenson G, Brown P K, Haase A, Reeves P R. Repeat unit polysaccharides of bacteria: a model for polymerization resembling that of ribosomes and fatty acid synthetase, with a novel mechanism for determining chain length. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:725–734. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Batchelor R A, Alifano P, Biffali E, Hull S I, Hull R A. Nucleotide sequences of the genes regulating O-polysaccharide antigen chain length (rol) from Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: protein homology and functional complementation. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5228–5236. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.16.5228-5236.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burnette W N. “Western blotting”: electrophoretic transfer of proteins from sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gels to unmodified nitrocellulose and radiographic detection with antibody and radioiodinated protein A. Anal Biochem. 1981;112:195–203. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(81)90281-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burrows L L, Charter D F, Lam J S. Molecular characterization of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa serotype O5 B-band lipopolysaccharide gene cluster. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:481–495. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.1351503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burrows L L, Chow D, Lam J S. Pseudomonas aeruginosa B-band O-antigen chain length is modulated by Wzz (Rol) J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1482–1489. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.5.1482-1489.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dasgupta T, Lam J S. Identification of rfbA, involved in B-band lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa serotype O5. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1674–1680. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1674-1680.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Kievit T R, Dasgupta T, Schweitzer H, Lam J S. Molecular cloning and characterization of the rfc gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (serotype O5) Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:565–574. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dodgson C, Amor P, Whitfield C. Distribution of the rol gene encoding the regulator of lipopolysaccharide O-chain length in Escherichia coli and its influence on the expression of group I capsular K antigens. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1895–1902. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.7.1895-1902.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dubray G, Bezard G. A highly sensitive periodic acid-silver stain for 1,2-diol groups of glycoproteins and polysaccharides in polyacrylamide gels. Anal Biochem. 1982;119:325–329. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(82)90593-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franco A V, Liu D, Reeves P R. A Wzz (Cld) protein determines the chain length of K lipopolysaccharide in Escherichia coli O8 and O9 strains. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1903–1907. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.7.1903-1907.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldberg J B, Ohman D E. Cloning and expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa of a gene involved with the production of alginate. J Bacteriol. 1984;158:1115–1121. doi: 10.1128/jb.158.3.1115-1121.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hancock R E W, Carey A M. Outer membrane of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: heat- and 2-mercaptoethanol-modifiable proteins. J Bacteriol. 1979;140:902–910. doi: 10.1128/jb.140.3.902-910.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hitchcock P J, Brown T M. Morphological heterogeneity among Salmonella lipopolysaccharide chemotypes in silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. J Bacteriol. 1983;154:269–277. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.1.269-277.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoang T T, Karkhoff-Schweizer R R, Kutchma A J, Schweizer H P. A broad-host-range Flp-FRT recombination system for site-specific excision of chromosomally-located DNA sequences: application for isolation of unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants. Gene. 1998;212:77–86. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huff J P, Grant B J, Penning C A, Sullivan K F. Optimization of routine transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmid DNA. BioTechniques. 1990;9:570–577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keenleyside W J, Whitfield C. A novel pathway for O-polysaccharide biosynthesis in Salmonella enterica serovar Borreze. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:28581–28592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.45.28581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kido N, Torgov V I, Sugiyama T, Uchiya K, Sugihara H, Komatsu T, Kato N, Jann K. Expression of the O9 polysaccharide of Escherichia coli: sequencing of the E. coli O9 rfb gene cluster, characterization of mannosyl transferases, and evidence for an ATP-binding cassette transport system. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2178–2187. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.8.2178-2187.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knirel Y A, Kochetkov N K. The structure of lipopolysaccharides of Gram-negative bacteria. III. The structure of O-antigens: a review. Biochemistry (Moscow) 1994;59:1325–1383. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lam J S, Handelsman M Y C, Chivers T R, MacDonald L A. Monoclonal antibodies as probes to examine serotype-specific and cross-reactive epitopes of lipopolysaccharides from serotypes O2, O5, and O16 of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2178–2184. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.7.2178-2184.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lam M Y C, McGroarty E J, Kropinski A M, MacDonald L A, Pedersen S S, Høiby N, Lam J S. Occurrence of a common lipopolysaccharide antigen in standard and clinical strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:962–967. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.5.962-967.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lightfoot J L, Lam J S. Molecular cloning of genes involved with expression of A-band lipopolysaccharide, an antigenically conserved form, in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5624–5630. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.18.5624-5630.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lightfoot J L, Lam J S. Chromosomal mapping, expression and synthesis of lipopolysaccharide in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a role for guanosine diphospho (GDP)-d-mannose. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:771–782. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu D, Cole R A, Reeves P R. An O-antigen processing function for Wzx (RfbX): a promising candidate for O-unit flippase. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2102–2107. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.7.2102-2107.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Macpherson D F, Manning P A, Morona R. Genetic analysis of the rfbX gene of Shigella flexneri. Gene. 1995;155:9–17. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)00918-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morona R, Mavris M, Fallarino A, Manning P A. Characterization of the rfc region of Shigella flexneri. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:733–747. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.3.733-747.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morona R, van den Bosch L, Manning P A. Molecular, genetic, and topological characterization of O-antigen chain length regulation in Shigella flexneri. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1059–1068. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.4.1059-1068.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rocchetta H L, Lam J S. Identification and functional characterization of an ABC transport system involved in polysaccharide export of A-band lipopolysaccharide in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4713–4724. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.15.4713-4724.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rocchetta H L, Burrows L L, Pacan J C, Lam J S. Three rhamnosyltransferases responsible for assembly of the A-band d-rhamnan polysaccharide in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a fourth transferase, WbpL, is required for the initiation of both A-band and B-band lipopolysaccharide synthesis. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:1103–1119. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schnaitman C, Klena J. Genetics of lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis in enteric bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:655–682. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.3.655-682.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schweizer H P. Small broad-host-range gentamycin resistance gene cassettes for site-specific insertion and deletion mutagenesis. BioTechniques. 1993;15:831–833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schweizer H P, Hoang T T. An improved system for gene replacement and xylE fusion analysis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene. 1995;158:15–22. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00055-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simon R, Priefer U, Pühler A. A broad-host-range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram-negative bacteria. Bio/Technology. 1983;1:784–791. [Google Scholar]

- 35.West S E H, Schweizer H P, Dall C, Sample A K, Runyen-Janecky L J. Construction of improved Escherichia-Pseudomonas shuttle vectors derived from pUC18/19 and the sequence of the region required for their replication in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene. 1994;128:81–86. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whitfield C. Biosynthesis of lipopolysaccharide O-antigens. Trends Microbiol. 1995;3:178–185. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)88917-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whitfield C, Amor P A, Köplin R. Modulation of the surface architecture of Gram-negative bacteria by the action of surface polymer:lipid A-core ligase and by determinants of polymer chain length. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:629–638. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2571614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wozniak, D. Personal communication.

- 39.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]