Abstract

The polypeptide and structural gene for a high-molecular-mass c-type cytochrome, cytochrome c553O, was isolated from the methanotroph Methylococcus capsulatus Bath. Cytochrome c553O is a homodimer with a subunit molecular mass of 124,350 Da and an isoelectric point of 6.0. The heme c concentration was estimated to be 8.2 ± 0.4 mol of heme c per subunit. The electron paramagnetic resonance spectrum showed the presence of multiple low spin, S = 1/2, hemes. A degenerate oligonucleotide probe synthesized based on the N-terminal amino acid sequence of cytochrome c553O was used to identify a DNA fragment from M. capsulatus Bath that contains occ, the gene encoding cytochrome c553O. occ is part of a gene cluster which contains three other open reading frames (ORFs). ORF1 encodes a putative periplasmic c-type cytochrome with a molecular mass of 118,620 Da that shows approximately 40% amino acid sequence identity with occ and contains nine c-heme-binding motifs. ORF3 encodes a putative periplasmic c-type cytochrome with a molecular mass of 94,000 Da and contains seven c-heme-binding motifs but shows no sequence homology to occ or ORF1. ORF4 encodes a putative 11,100-Da protein. The four ORFs have no apparent similarity to any proteins in the GenBank database. The subunit molecular masses, arrangement and number of hemes, and amino acid sequences demonstrate that cytochrome c553O and the gene products of ORF1 and ORF3 constitute a new class of c-type cytochrome.

Methylococcus capsulatus Bath is an obligate methylotroph that utilizes methane as its sole energy and carbon source. As for most other methanotrophs, methane and methanol are the only known growth substrates (6, 30). In methanotrophs, methane is oxidized via a series of two electron steps, with methanol, formaldehyde, and formate as intermediates (6, 30). The reductant for the first, energy-dependent, step is supplied by either NADH or by the respiratory chain, depending on which methane monooxygenase (MMO) is expressed (6, 15, 25, 30, 47, 54, 59, 61). The second, two-electron step, catalyzed by the methanol dehydrogenase, involves the oxidation of methanol to formaldehyde with a c-type cytochrome as an electron acceptor (6, 7, 30, 58). Formaldehyde is either assimilated via the serine or ribulose monophosphate cycle (6, 30) or oxidized to formate by either an NAD+-linked or a dye (i.e., cytochrome b)-linked formaldehyde dehydrogenase or by a tetrahydromethanopterin-methanofuran-mediated pathway (6, 13, 30, 55, 62). Lastly, formate is oxidized to carbon dioxide by an NAD+-linked formate dehydrogenase (34). With the possible exception of an electron donor to the membrane-associated methane monooxygenase (pMMO), c-type cytochromes are known to be involved only in the methanol oxidation step (6, 7, 38).

In contrast to the limited role of c-type cytochromes in the oxidation of growth substrates, methanotrophs show complex cytochrome c patterns similar to that observed in the facultative methylotrophs (6, 7, 11, 18, 30, 38, 61–65). For example, seven c-type cytochromes have been purified (5, 63–65), and the structural genes for two additional multiheme cytochromes have been identified (this study) in M. capsulatus Bath. Two of the seven have enzymatic activity; cytochrome c-peroxidase (65) and cytochrome P460 (10, 63), while the remaining five appear to function in electron transfer (5, 61, 63, 64). The complexity of the respiratory systems in methanotrophs provides suggestive evidence that the current biochemical models for methanotrophs underestimate the biochemical capabilities of these organisms. In addition to the known growth substrates, methanotrophs will oxidize or co-oxidize a variety of compounds, depending on the form of MMO expressed (14, 15, 20, 39, 52, 54, 59). Cells expressing the soluble MMO will oxidize straight-chain or branched-chain alkanes or alkenes up to eight carbons long as well as cyclic and aromatic compounds (14, 30, 51, 59). Cells expressing the pMMO will oxidize alkanes and alkenes up to five carbons long but will not oxidize cyclic or aromatic compounds (19, 30, 39, 52). With the exception of methane and, in some cases, methanol, the oxidation of other substrates does not support growth and has been termed co-oxidation. Implicit in the use of the term co-oxidation is that the oxidation provides no metabolic energy. However, some cosubstrates may generate metabolic energy. For example, both MMOs catalyze the energy-dependent oxidation of ammonia to hydroxylamine (16, 47, 63). In M. capsulatus Bath, cytochrome P460 catalyzes the four-electron oxidation of hydroxylamine to nitrite (63). This two-step oxidation of ammonia to nitrite is identical to that observed in nitrifying bacteria, although the enzymes catalyzing the steps have been shown to differ (9, 10, 63). The similar mechanisms of oxidation of ammonia in both groups of bacteria suggest that metabolic energy is obtained during ammonia oxidation in methanotrophs.

Whether the oxidation of hydroxylamine also provides reductant for ammonia (or methane) oxidation or whether all four electrons are transferred to the terminal oxidases (21, 62) via cytochrome c′ (64) and cytochrome c555 (5) has not been determined for methanotrophs. In the nitrifying bacterium Nitrosomonas europaea, the four electrons from the oxidation of hydroxylamine are transferred to the tetraheme cytochrome, cytochrome c554, which acts as a redox mediator from hydroxylamine oxidoreductase to both the ammonia monooxygenase and the terminal oxidase (17, 33). In the current study, we present the isolation of an octyl-heme cytochrome, cytochrome c553O. The structural gene for cytochrome c553O was part of a gene cluster containing two other putative high-molecular-mass multiheme cytochromes. The physiological role for these proteins is still unknown. However, one or more of these high-molecular-mass cytochromes appears to be induced by ammonia (10) and may function like cytochrome c554 in N. europaea.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culture conditions.

Culture conditions for N. europaea, M. capsulatus Bath, Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b, Methylocystis parvus OBBP, Methylobacter marinus A45, Methylomicrobium albus BG8, and Methylomonas sp. strains MN and MM2 were described previously (10, 18, 19, 61).

Isolation of cytochrome c553O.

All procedures were performed at 4°C. Cell lysis and initial separation of cytochrome c553O from other c-type cytochromes was described by Zahn et al. (65). Following the Sephadex B-75 gel-filtration step, the sample was collected and brought to 20% saturation with a concentrated solution of ammonium sulfate. The sample was loaded on a phenyl Sepharose CL-4B column (2.5 by 21 cm) previously equilibrated in 1.24 M ammonium sulfate and 20 mM Tris (pH 8). The column was washed in a sequential order with 1.5 column volumes each of buffers containing 20 mM Tris (pH 8) plus 1.24 M ammonium phosphate, 20 mM Tris (pH 8) plus 0.83 M ammonium phosphate, and 20 mM Tris (pH 8) plus 0.50 M ammonium sulfate. The cytochrome fraction remained bound to the column during the washing procedure and was eluted with 2 column volumes of a buffer containing 20 mM Tris (pH 8) plus 3% of saturation ammonium sulfate. The fraction was dialyzed by ultrafiltration into 40 mM Tris (pH 9) and concentrated with a YM-10 ultrafiltration membrane. The fraction was loaded on a Q-Sepharose fast-flow column (1.25 by 14 cm) equilibrated in 40 mM Tris (pH 9), and the column was developed with a linear gradient of 0 to 200 mM KCl plus 40 mM Tris (pH 9). Purified cytochrome c553O eluted at a salt concentration of approximately 160 mM KCl. The cytochrome had a dithionite-reduced α-band absorption maxima at 553 nm and an oxidized absorbance (A411/A280) ratio of 4.3.

Electrophoresis.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide slab gel electrophoresis was carried out by the Laemmli method on 10 to 16% polyacrylamide gels (35). Gels were stained for total protein with Coomassie brilliant blue R. Proteins with peroxidase activity in SDS-polyacrylamide gels were stained by the diaminobenzidine method (41). Preparative isoelectric focusing in a granulated gel matrix was performed with a Pharmacia Multiphor I system at 4°C with Ultrodex and 2% ampholine (pH, 3 to 10) as described by the manufacturer.

Analytical ultracentrifugation.

Sedimentation velocity experiments were performed with a Beckman Optima XL-A analytical ultracentrifuge equipped with a Beckman An-60 Ti rotor. Samples of cytochrome c553O were dialyzed against three changes of buffer containing 50 mM phosphate (pH 7) or 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) plus 150 mM KCl. The sample and reference cell assemblies were monitored with a wavelength of 410 nm. Separate sedimentation velocity experiments were performed with rotor speeds of 20,000 and 15,000 rpm. Rotor temperature was maintained at 20°C during sedimentation experiments. Partial specific volume (v) of M. capsulatus Bath cytochrome c553O was calculated from the amino acid composition by the method of Cohn and Edsall. Solution density (p) was corrected for buffer concentration by the method of Laue et al. (36).

Spectroscopy.

Optical absorption spectroscopy was performed with an SLM Aminco DW-2000 spectrophotometer in the split-beam mode.

Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra were recorded at X band on a Bruker ER 200D EPR spectrometer equipped with an Oxford Instruments ESR-900 liquid helium cryostat. Operating parameters were as listed in the figure legends. Samples were maintained at 8K during spectral acquisition.

Heme, metal, and protein determination.

The optical extinction coefficient values for cytochrome c553O were estimated by using the total protein values derived from the amino acid analysis and a subunit molecular mass of 124,350 Da. Heme composition was determined by the pyridine ferrohemochrome method (18, 26). The acid acetone method was used to determine covalent linkage of the prosthetic groups to the polypeptide (26). Cytochrome c5530 was analyzed for copper, iron, and zinc as described by Zahn et al. (64).

Amino acid analysis and sequence analysis.

Amino acid analysis was carried out with an Applied Biosystems 420A derivatizer coupled with an Applied Biosystems 130A separation system. Samples were hydrolyzed in 6 M HCl plus trace amounts of phenol in HCl vapors for 1 h and then in a vacuum at 150°C. After hydrolysis, norleucine was added as an internal standard.

Amino acid sequence analysis was performed by Edman degradation with an Applied Biosystems 477A protein sequencer coupled with a 120A analyzer.

DNA/RNA methods.

Degenerate oligonucleotide probes were prepared by the Iowa State University DNA Sequencing Facility and 5′ end labeled with [32P]ATP with T4 polynucleotide kinase (48). Longer, double-stranded probes were prepared by the random hexamer priming technique (24) by using the Prime-A-Gene kit (Promega Corporation, Madison, Wis.). To hybridize Southern blots with degenerate oligonucleotide probes, membranes were prehybridized for 1 h and hybridized overnight in 6× SSPE (1× SSPE is 0.18 M NaCl, 10 mM NaH2PO4, and 1 mM EDTA [pH 7.7]), 1× Denhardt’s solution, 0.5% SDS, and 10% polyethylene glycol (molecular mass, 8,000 Da) at 42°C (48). To hybridize Southern blots with longer probes, membranes were prehybridized for 1 h and hybridized overnight in 6× SSPE, 0.5% BLOTTO (48), and 0.5% SDS at 55°C. Southern blots were washed briefly in low-stringency buffer (1× SSPE, 0.2% SDS) at 20°C and then for 30 min in high-stringency buffer (0.1× SSPE, 0.2% SDS) at various temperatures. Southern blots were imaged by exposure to a Molecular Imager phosphorimager system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) or by standard autoradiography (48).

Primer extension mapping of transcripts.

Total RNA was isolated from a late-log-phase culture of M. capsulatus Bath by a modification of the method of Waechter-Brulla (58). Ten milliliters of culture was centrifuged briefly at 3,000 × g at 5°C, and the cell pellet was resuspended in 3.3 ml of TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 1 mM EDTA). A total of 1.3 ml of hot lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 0.2% SDS [wt/vol], 20 mM EDTA, and 200 mM NaCl) was added, and the mixture was incubated for 3 min at 70°C. The solution was then extracted three times with phenol (pH 4.3) at 70°C, once with phenol-chloroform isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1 [pH 7.5]) at 20°C, and once with chloroform isoamyl alcohol (24:1) at 20°C. RNA was precipitated by the addition of 1/10 volume of 3.0 M sodium acetate (pH 4.0) and 2 volumes of ethanol and incubation for over 12 h at 20°C, and the pellet was resuspended in water with 0.1 M EDTA.

Primer extension analysis of transcripts was performed as described by Nielsen et al. (43), using three primers, THICB (5′-GGTATTCATGGTTCCTCCAG-3′), THICA (5′-GCTTTTCTTGTTCTCGAT-3′), and TDW2 (5′-CTG-GAG-TGC-GAG-GAG-CTA-3′). Primer extension products were separated by denaturing electrophoresis alongside samples of dideoxy sequencing reactions (Sequenase 2.0 kit; United States Biochemicals, Cleveland, Ohio) performed with the same primers and visualized by autoradiography.

All other DNA/RNA techniques are described in Bergmann et al. (10).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

DNA sequences were deposited in GenBank under accession no. AF117827.

RESULTS

Purification of cytochrome c553O.

The purification of cytochrome c553O from M. capsulatus Bath cultured in nitrate mineral salts medium was performed as described in Materials and Methods. The initial purification step involved separation of cytochrome c553O, which migrates in the void volume from methanol dehydrogenase (MeDH) (approximate molecular mass, 120,000 Da) and other lower-molecular-mass c-type cytochromes (65), by using a 5 by 96 cm Sephadex G-75 column. The separation of cytochrome c553O from MeDH was well beyond the normal separation capacity of Sephadex G-75. However, this separation was obtained if the resin was degassed before the resin was poured. If the resin was not degassed, cytochrome c553O and MeDH comigrated in the void volume.

Molecular mass.

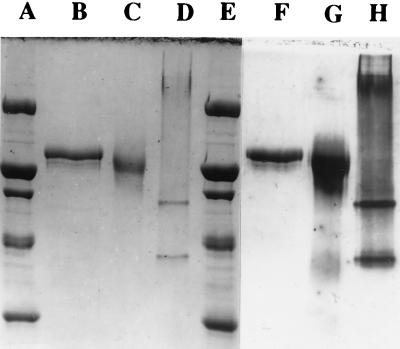

In SDS-polyacrylamide gels, cytochrome c553O migrated as a single band corresponding to a molecular mass of 142,000 Da (Fig. 1). The sample required both β-mercaptoethanol and heat treatments before being loaded on SDS-polyacrylamide gels for complete unfolding of the polypeptide chain, indicating the presence of interpeptide disulfide bonding (Fig. 1). Comparison of the subunit mass, as determined by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, with the subunit mass plus eight hemes c predicted by the gene sequence (124,350 Da) shows a discrepancy of approximately 12%. The high-charge density of the eight covalently bound hemes may be responsible for this discrepancy.

FIG. 1.

SDS-polyacrylamide slab gel electrophoresis of purified fractions of M. capsulatus Bath cytochrome c553O stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 (lanes A through E) or stained for c-type heme by the diaminobenzidine method (lanes F through H). Molecular mass standards 200,000, 116,000, 97,400, 66,000, and 45,000 kDa are shown in lane A. Lanes B and F, purified cytochrome reduced with β-mercaptoethanol and heated to 95°C for 2 min prior to loading; lanes C and G, purified cytochrome reduced with β-mercaptoethanol prior to loading; lanes D and H, purified cytochrome without the addition of β-mercaptoethanol to the sample buffer and without heating of sample prior to loading.

The molecular mass of native cytochrome c553O from M. capsulatus Bath was estimated to be 202,577 ± 2,765 Da by analytical ultracentrifugation (Table 1). The geometrical shape of ferricytochrome c553O was assigned based on the prolate ellipsoid model by using the values calculated for the partial specific volume and sedimentation values determined by sedimentation velocity experiments. The axial ratio value of approximately 15:1 (Table 1) indicates that the cytochrome has a nonuniform, highly elongated shape. The unique hydrodynamic property of cytochrome c553O is probably the reason for the large difference in the holoenzyme mass determined by sedimentation velocity (202,580 Da) and the proposed α2 dimer estimated by the translated gene sequence plus 16 hemes c (248,700 Da). The results suggest that cytochrome c553O consists of a dimer composed of two identical subunits.

TABLE 1.

Properties of cytochrome c553O from M. capsulatus Bath

| Property | Value |

|---|---|

| Molecular mass | |

| Enzyme (kDa) | 202,577 ± 2,765 |

| Sedimentation coefficient (S*20)3 (s) | 1.2139 · 10−12 |

| Diffusion coefficient (D20)3 (cm2 · s−1) | 1.9858 · 10−7 |

| Partial specific volumecalculated (mg · gm−1)2 | 0.726 |

| Frictional coefficient (f) | 6.174 · 1016 |

| Frictional coefficient for a spherical particle (f0) | 1.229 · 1017 |

| Frictional coefficient ratio (f/f0) | 1.99 |

| Prolate model axial ratio (a/b) | ≈15 |

| Subunit molecular mass (Da) | |

| SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis | 142,000 |

| Translated amino acid sequence plus 8 c-hemes | 124,350 |

| Heme c concentration (mol/mol of enzyme) | 8.2 ± 0.4 |

| Absorption maxima (nm) | |

| Oxidized | 411,527 |

| Dithionite-reduced | 421, 525, 553 |

| Ferrohemochromagen | 514, 520, 550 |

| Molar absorptivity (cm−1 · mM−1) | |

| Ferrochrome (ɛ 421 to 700 nm) | 882.1 |

| Ferrohemochromagen (ɛ 550 to 600 nm) | 837.7 |

| EPR (signals) | |

| LS 1 (≅1 heme per cytochrome) | gz = 3.66, gy = 1.8, gx = <0.7 |

| LS 2 (≅5 hemes per cytochrome) | gz = 2.97, gy = 2.26, gx = 1.49 |

| HS (≅0.1 heme per cytochrome) | 6.0, 4.3, 2.00 |

| Purity index (Abs. 411 nm/280 nm) | 4.3 |

Heme and metal components.

The prosthetic groups of cytochrome c553O were identified as c types by the acid acetone method and ferrohemochromogen spectra. Assuming a molecular mass of 124,350 Da and protein concentrations determined by amino acid analysis, cytochrome c553O was determined to contain 8.2 ± 0.4 hemes.

Elemental analysis showed the absence of nonheme iron or other transition metals in cytochrome c553O.

Spectral properties.

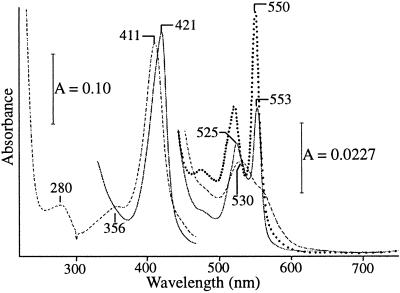

Purified preparations of cytochrome c553O exhibited a γ band/280-nm absorbance intensity ratio (411 nm/280 nm = 4.3) that fell within the range of other purified c-heme-containing cytochromes (γ band/280 nm = 4.2 to 5.6; Fig. 2) (28, 29, 65). The γ band of cytochrome c553O exhibited a broad linewidth, a feature commonly observed with other multiheme cytochromes (37). Analysis of spectra of the ferricytochrome in the near infrared region provided no evidence for the presence of a high-spin (HS) heme (≈630 nm), and there was no evidence that methionine was an axial ligand (≈695 nm) for hemes present in the cytochrome. Neither the ferricytochrome nor the ferrocytochrome was observed to react or bind the ligands carbon monoxide, cyanide, or nitric oxide.

FIG. 2.

Absorption spectra of 0.360 μM (51.19 μg of protein per ml) purified cytochrome c553O in 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8). Absorption of resting M. capsulatus Bath cytochrome c553O (–––––), following reduction with dithionite (———), and the pyridine ferrohemocytochrome of cytochrome c553O (⋯ ⋯ ⋯).

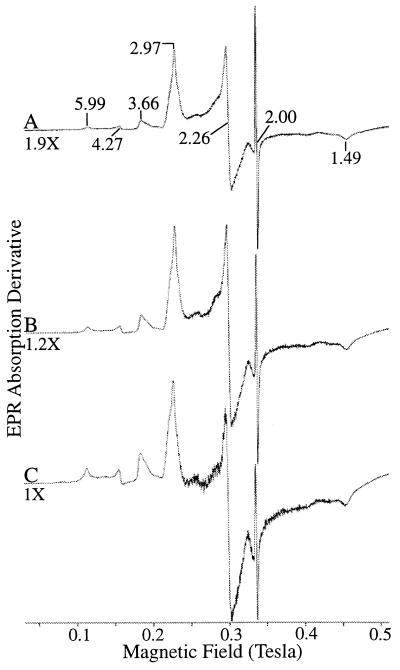

The low-temperature X band EPR spectrum of ferricytochrome c553O is shown in Fig. 3. The spectrum is complex, with at least two major low-spin (LS) ferric heme centers, designated LS species 1 (LS 1): gz = 3.66, gy = 1.8, gx = <0.7 and LS 2: gz = 2.97, gy = 2.26, gx = 1.49, a minor population of an HS species (g = 6.0), ferric iron in a rhombic environment (g = 4.27), and a free-radical signal at g = 2.00. The signal at g = 4.27 has been assigned to adventitiously bound ferric iron. While no structural assignment could be deduced for the free-radical g = 2 signal, the linewidth is identical to enzymes that employ a free radical located on an intrinsic amino acid residue as a cofactor (45). The free-radical signal appeared unrelated to the EPR signals associated with the hemes as demonstrated in the differences in power saturation characteristics (Fig. 3). At higher-microwave-power intensity, the free-radical signal was easily saturated (≈50 mW), while signals associated with the LS hemes remained unsaturated at high-microwave powers. The fast-relaxing behavior of the LS heme centers of cytochrome c553O has also been observed in the 50-kDa multi-c-heme cytochrome from Desulfuromonas acetoxidans (50). However, this property is uncommon in LS c-heme cytochromes.

FIG. 3.

EPR spectrum of purified M. capsulatus Bath cytochrome c553O in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8) at 8K at 0.2 mW (trace A), 2.0 mW (trace B), and 20 mW (trace C) power. Instrumental conditions were as follows: modulation frequency, 100 kHz; modulation amplitude, 6.25 G; microwave frequency, 9.422 GHz; receiver gain, 3.20 × 103; and time constant, 100 ms. The sample temperature was maintained at 8K during spectral analysis.

Integration of LS signals originating from LS 1 and LS 2 accounted for only six of the eight hemes present per subunit. Based on a subunit molecular mass predicted from the gene sequence plus heme groups (124,350 Da), EPR spin quantitation experiments indicate that the stoichiometry of heme species is 5 mol/subunit associated with LS 2, 1 mol/subunit associated with LS 1, and less than 0.1 mol/subunit associated with the HS species (g = 6) present in cytochrome c553O. The two hemes not directly accounted for by spin quantitation methods may be due to unassigned resonances present in the cytochrome or to the presence of EPR-silent c-heme centers in the cytochrome. The latter has been observed for other multiheme cytochromes, including hydroxylamine oxidoreductase from N. europaea (37) and a 65,000-Da cytochrome of unknown function from D. acetoxidans (46).

Unique features in the EPR spectrum of cytochrome c553O are the very large gz value and the asymmetric line shape associated with LS 1. The highly anisotropic strong-gz EPR signals have also been observed in cytochrome c554 from Bacillis halodenitrificans (50), cytochrome c554 from Achromobacter cycloclastes (49), and cytochrome c4 from Azotobacter vinelandii (27). This signal has been attributed to axial ligand field symmetry through the perpendicular alignment of the ligand planes (50). Many strong-gz EPR signals have been shown to have a methionine as a heme ligand or a methionine that is proximal to the heme-binding motif (50). Although visible absorption spectra did not support the EPR evidence for a methionine residue as a heme ligand in cytochrome c553O, analysis of the gene sequence has identified a single heme-binding motif starting at Cys 806 and containing a Met in position 813, which is expected to contribute to perpendicular alignment of the ligand planes.

Cloning and sequencing the occ gene cluster of M. capsulatus Bath.

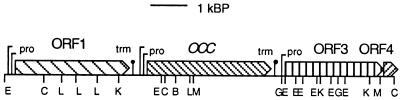

The N-terminal amino acid sequence of cytochrome c553O from M. capsulatus Bath was ASVSGSAKLDAGLGKVSVKGKTAGLAPG. This sequence was used to synthesize a degenerate oligonucleotide probe with the sequence 5′-AA (A/G)-G(A/G)I-AA(A/G)-ACI-GCI-GGI-(T/C)TI-GCI-GC-3′, where I represents inosine. The probe was used to screen 2,300 clones of a cosmid library of M. capsulatus Bath genomic DNA, which identified a single positive clone containing a 3,477-bp open reading frame (ORF), occ, encoding cytochrome c553O (Fig. 4 and 5). A second ORF, ORF1, 3,241 bp long, was located 484 bp upstream of occ, and a third, ORF3, 3,985 bp long, was 435 bp downstream from occ. A fourth ORF, ORF4, encoding an 11,100-Da putative protein, was located 22 bp downstream of ORF3. Probable ρ-independent transcription termination sequences are located 44 bp downstream of ORF1 and 59 bp downstream of occ (Fig. 4). No transcription termination sequence was observed between ORF3 and ORF4.

FIG. 4.

Map of the occ gene cluster. Restriction sites: B, BamHI; G, BglII; E, EcoRI; K, KpnI; C, SacI; L, SalI; and M, SmaI. Abbreviations: pro, transcription start site; trm, putative rho-independent transcription termination site.

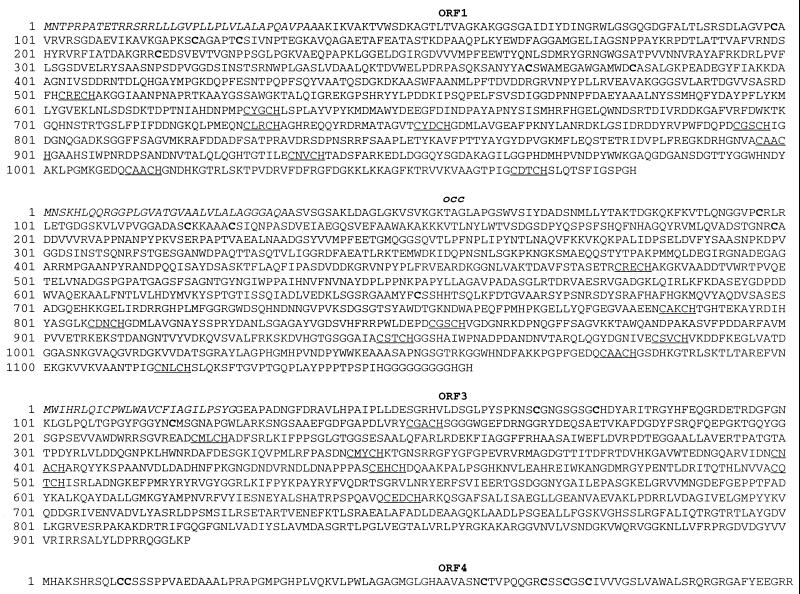

FIG. 5.

Amino acid sequence of the occ, ORF1, ORF3, and ORF4 gene cluster. Putative signal peptides are italicized; c-heme-binding motifs (CXXCH) are underlined; cysteine residues outside of c-heme-binding motifs are in bold.

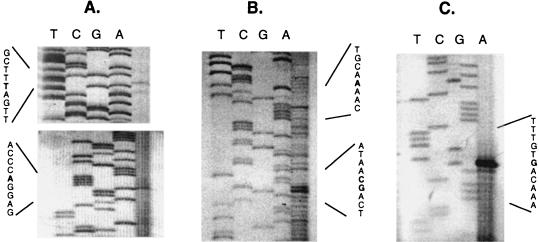

Primer extension analysis indicates that ORF1 has transcription start sites at bases 97, 118, and 119 (Fig. 6). Consensus −35 and −10 ς70 RNA polymerase promoter sequences are located upstream of the first transcription start site, while no consensus promoter sequences are upstream of the latter two sites. Another primer extension experiment indicated that occ has transcription start sites at bases 3712 and 3825 (Fig. 6). The first transcription start site is associated with −35 and −10 consensus ς70 promoter sequences, while the second is associated with consensus ς54 RNA polymerase promoter sequences. A third primer extension experiment indicated that ORF3 has a transcriptional start site at base 6782 associated with a −35 and −10 consensus ς70 promoter sequence.

FIG. 6.

Primer extension mapping of the 5′ ends of the occ, ORF1, and ORF3 transcripts with primers THICA (A), THICB (B), and TDW2 (C). Sequencing reactions with plasmid DNA template are shown on the left, with primer extension products on the right. The autoradiographs were exposed for 2 to 4 days at 22°C.

The physiological roles of cytochrome c553O and the gene products of ORF1, ORF3, and ORF4 have not been determined. However, a possible role in nitrogen metabolism is suggested by the two promoter sequences upstream of occ: an upstream promoter similar to canonical −35 and −10 sequences and a downstream promoter similar to NtrA-dependent −24 and −12 promoters in the Enterobacteriaceae (23). The results would be consistent with the earlier observation that at least one high-molecular-mass cytochrome is induced following the addition of ammonia to early-log-phase cultures of M. capsulatus Bath (10).

The nascent polypeptide encoded by occ containing the N-terminal amino acid sequence of cytochrome c553O (ASVSGSAKLDAGLGKVSVKGKTAGLAPG-) was preceded by a 33-residue signal peptide (Fig. 5). The occ polypeptide contains eight c-heme-binding motifs (CXXCH), consistent with the heme quantitation data that estimates 8.2 hemes per subunit. The processed c553O apocytochrome is predicted to have a mass of 119,408 Da, while the holocytochrome is predicted to have a mass of approximately 124,350 Da, somewhat less than the estimate of subunit mass by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Fig. 1).

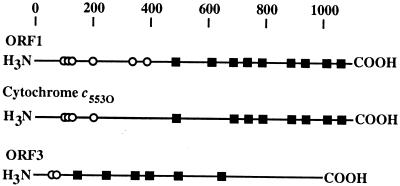

The ORF1 and ORF3 gene products are predicted to begin with putative signal peptide sequences 36 and 26 residues long, respectively. The holocytochromes encoded by ORF1 and ORF3 are predicted to have molecular masses of approximately 118,620 and 94,000 Da, respectively. The holocytochromes encoded by ORF1 and ORF3 are predicted to contain nine and seven c-heme-binding site motifs, respectively (Fig. 5 and 7).

FIG. 7.

Non-heme-associated cysteines ( ) and c-heme-binding motifs, CXXCH (■), in occ, ORF1, and ORF3. The scale at the top shows number of amino acids.

The occ and ORF1 polypeptides contain extensive regions of homology to each other, and the amino acid sequences of the two nascent polypeptides are 38.38% identical. However, a search of GenBank with the tFasta program (Genetics Computer Group, Madison, Wis.) produced no putative proteins homologous to either occ or ORF1. Eight of the nine c-heme-binding motifs in the ORF1 polypeptide are conserved in the occ polypeptide, while the second c-heme-binding motif in ORF1, CYGCH, is lacking in occ (Fig. 5 and 7). Both the occ and ORF1 polypeptides contain several cysteine residues outside of c-heme-binding site motifs (Fig. 5 and 7). The polypeptide encoded by ORF3 also has cysteine residues outside of typical c-heme-binding motifs (Fig. 5 and 7).

Southern blots.

A 3.50-kbp EcoRI-BglII fragment containing the occ gene of M. capsulatus Bath was used to probe restriction digests of genomic DNA from M. trichosporium OB3b, M. parvus OBBP, M. marinus A45, M. albus BG8, and Methylomonas sp. strains MN and MM2. In addition to hybridization with M. capsulatus restriction fragments, relatively strong hybridization was observed to restriction fragments of M. parvus OBBP DNA and M. trichosporium OB3b DNA (results not shown). No hybridization of the M. capsulatus Bath occ probe to DNA from other methanotroph species was observed. No hybridization to other species of methanotrophs was observed with a 1.5-kb BglII fragment of ORF3.

DISCUSSION

Both amino acid sequence and biochemical data indicate that cytochrome c553O belongs to a novel class of c cytochromes. The size of the polypeptide, the number and location of hemes, and the presence of cysteine residues outside of c-heme-binding motifs place cytochrome c553O, as well as the gene products of ORF1 and ORF3, outside of Ambler’s classification of c-type cytochromes (2–4). The size, sequence, and interheme distances distinguish cytochrome c553O from Ambler’s class III multiheme cytochromes as well as from other high-molecular-mass multiheme cytochromes (11, 31, 42, 44–46, 56, 60). In addition, these high-molecular-mass cytochromes show no similarities to the class IE cytochromes, which are characterized by non-heme-associated cysteine residues.

The role of cytochrome c553O remains unclear. Although redox titrations of cytochrome c553O were not performed, the fact that the cytochrome was not reduced by ascorbate suggests that all the hemes of cytochrome c553O have relatively low midpoint potentials. The fact that cytochrome c553O may be induced by ammonia indicates that cytochrome c553O may have a role in nitrogen metabolism. A role in nitrogen metabolism is also suggested by the two promoter sequences upstream of occ, an upstream promoter similar to consensus −35 and −10 sequences and a downstream promoter similar to NtrA-dependent −24 and −12 promoters in the Enterobacteriaceae (23). The presence of both −35 and −10 promoter sequences as well as −24 and −12 promoter sequences was observed in the glnA gene, which encodes glutamine synthetase, an enzyme involved in ammonia assimilation in M. capsulatus Bath (12). Although no enzymatic activity has been assigned to cytochrome c553O, the presence of a stable free-radical signal (Fig. 3; g = 2.00) indicates that the cytochrome may have catalytic properties (45). Stable protein radicals, such as tyrosyl radicals, are usually associated with active sites of enzymes (45).

Nucleic acid sequence data indicate that there are two other high-molecular-weight, multi-heme c cytochromes in M. capsulatus Bath, the gene products of ORF1 and ORF3. The ORF1 gene product has considerable homology with cytochrome c553O, yet the difference in its sequence is sufficient to indicate that it is not merely an isoenzyme. An additional c-heme-binding site motif, ORF3, has no sequence homology with occ or ORF1 but shares the structural properties of multiple heme-binding motifs, long distances between heme-binding motifs, and the cysteine residues not associated with c-heme-binding motifs (Fig. 7).

Gene probing with occ indicated that cytochromes similar to that from M. capsulatus Bath may be present in the type II methanotrophs, M. trichosporium OB3b and M. parvus OBBP, but not in the type I methanotrophs, M. marinus A45, M. albus BG8, and Methylomonas sp. strains MN and MM2. Probing results were consistent with gene probing with cyp, the structural gene for cytochrome P460 (10), but not with the phylogenetic relationships with ribosomal RNA or pMMO gene sequence data (30, 32). No hybridization to the ORF3 gene probe was observed with any of the methanotrophs or nitrifier tested. At present, it is uncertain if this class of c cytochromes is found in type I methanotrophs, since DNA from these methanotrophs does not hybridize to the M. capsulatus Bath occ or ORF3 gene probes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank B. Voss (Iowa State University) and J. Nott (Iowa State University Protein Facility) for technical assistance.

This work was supported by Department of Energy grant 02-96ER20237 (to A.D.S.).

Footnotes

This journal paper J-18099 is a contribution from the Agriculture and Home Economics Experiment Station, Ames, Iowa (project 3252).

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ambler R P. Sequence variability in bacterial cytochromes c.Biochim. Biophys Acta. 1991;1058:42–47. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(05)80266-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ambler R P. The structure and classification of cytochromes c, In: Robinson A B, Kaplan N O, editors. From cyclotrons to cytochromes. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1982. pp. 263–280. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ambler R P, Bartsch R G, Daniel M, Kamen M D, McLellan L, Meyer T E, Van Beeumen J. Amino acid sequences of bacterial cytochromes c′ and c-556.Proc. Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:6854–6857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.11.6854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ambler R P, Dalton H, Meyer T E, Bartsch R G, Kamen M D. The amino acid sequence of cytochrome c555 from the methane-oxidizing bacterium Methylococcus capsulatus. Biochem J. 1986;233:333–337. doi: 10.1042/bj2330333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anthony C. The biochemistry of methylotrophs. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anthony C. The c-type cytochromes of methylotrophic bacteria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1099:1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidmann J G, Smith J A, Struhl K. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: Wiley/Greene Publishing Associates; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bergmann D J, Hooper A B. The primary structure of cytochrome P460 of Nitrosomonas europaea: the presence of a c-heme binding motif. FEBS Lett. 1994;353:324–326. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergmann D J, Zahn J A, Hooper A B, DiSpirito A A. Cytochrome P460 genes from the methanotroph Methylococcus capsulatusBath. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6440–6445. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.24.6440-6445.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruchi M, Bertrand P, More C, Leroy G, Bonicel J, Haladijian J, Chottard G, Collock C W B R, Voordouw G. Biochemical and spectroscopic characterization of the high molecular weight cytochrome c from Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough expressed in Desulfovibrio desulfuricansG200. Biochemistry. 1992;31:3281–3288. doi: 10.1021/bi00127a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cardy D L, Murrell J C. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of the glutamine synthetase structural gene (glnA) from the obligate methanotroph M. capsulatusBath. J Gen Microbiol. 1990;136:343–352. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-2-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chistoserdova L, Vorholt J A, Thauer R K, Lidstrom M E. C1transfer enzymes and coenzymes linking methylotrophic bacteria and methanogenic archaea. Science. 1998;281:99–101. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5373.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colby J, Stirling D I, Dalton H. The soluble methane monooxygenase from Methylococcus capsulatus Bath: its ability to oxidize n-alkanes, n-alkenes, ethers, and alicyclic, aromatic, and heterocyclic compounds. Biochem J. 1977;165:395–402. doi: 10.1042/bj1650395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dalton H, Prior S D, Stanley S H. Regulation and control of methane monooxygenase. In: Crawford R L, Hanson R S, editors. Microbial growth on C1 compounds. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1984. pp. 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dalton H. Ammonia oxidation by the methane oxidizing bacterium Methylococcus capsulatusstrain Bath. Arch Microbiol. 1977;114:273–279. [Google Scholar]

- 17.DiSpirito A A, Balny C, Hooper A B. Conformational change accompanies redox reactions of the tetraheme cytochromes c554 of Nitrosomonas europaea. Eur J Biochem. 1987;162:299–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb10600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DiSpirito A A. Soluble cytochromes c from Methylomonassp. A4. Methods Enzymol. 1990;188:289–297. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)88045-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DiSpirito A A, Lipscomb J D, Lidstrom M E. Soluble cytochromes from the marine methanotroph Methylomonassp. strain A4. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:5360–5367. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.9.5360-5367.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DiSpirito A A, Gulledge J, Shiemke A K, Murrell J C, Lidstrom M E, Krema C L. Trichloroethylene oxidation by the membrane-associated methane monooxygenase in type I, type II, and type X methanotrophs. Biodegradation. 1992;2:151–164. [Google Scholar]

- 21.DiSpirito A A, Shiemke A K, Jordan S W, Zahn J A, Krema C L. Cytochrome aa3 from Methylococcus capsulatusBath. Arch Microbiol. 1994;161:258–265. [Google Scholar]

- 22.DiSpirito A A, Zahn J A, Graham D W, Kim H J, Larive C K, Cox C D, Taylor A. Copper-binding compounds from Methylosinus trichosporiumOB3b. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3606–3613. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.14.3606-3613.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dixon R. The genetic complexity of nitrogen fixation. J Gen Microbiol. 1984;130:2745–2755. doi: 10.1099/00221287-130-11-2745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feinburg A P, Vogelstein B. A technique for radiolabeling DNA restriction endonuclease fragments to high specific activity. Anal Biochem. 1983;132:6–13. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fox B J, Froland W A, Dege J E, Lipscomb J D. Methane monooxygenase from Methylosinus trichosporiumOB3b. Purification and properties of a three-component system with high specific activity from a type II methanotroph. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:10023–10033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fuhrhop J-H. Laboratory methods in porphyrin and metalloporphyrin research. New York, N.Y: Elsevier Scientific Publishers; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gadsby P M, Hartshorn R T, Moura J J, Sinclair-Day J D, Sykes A G, Thomson A J. Redox properties of the diheme cytochrome c4 from Azotobacter vinelandiiand characterization of the two hemes by NMR, MCD and EPR spectroscopy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;994:37–46. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(89)90059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilmore R, Goodhew C F, Pettigrew C F, Prazers S, Moura J J G, Mora I. The kinetics of the oxidation of cytochrome c peroxidases. Biochem J. 1994;300:907–914. doi: 10.1042/bj3000907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goodhew C F, Wilson I B H, Hunter D J B, Pettigrew G W. The cellular location and specificity of bacterial cytochrome c peroxidases. Biochem J. 1990;271:707–712. doi: 10.1042/bj2710707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanson R S, Hanson T E. Methanotrophic bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:439–471. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.2.439-471.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Higuchi M, Inaka K, Yasuoka N, Yagi T. Isolation and crystallization of high molecular weight cytochrome from Desulfovibrio vulgarisHildenborough. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1987;911:341–348. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holmes A J, Costello A, Lidstrom M E, Murrell J C. Evidence that the particulate methane monooxygenase and ammonia monooxygenase may be evolutionarily related. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;132:230–208. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(95)00311-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hooper A B, Vannelli T, Bergmann D J, Arciero D M. Enzymology of the oxidation of ammonia to nitrite by bacteria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1997;71:59–1997. doi: 10.1023/a:1000133919203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jollie D R, Lipscomb J D. Formate dehydrogenase from Methylosinus trichosporiumOB3b. Methods Enzymol. 1990;188:331–334. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)88051-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laue T M, Shah B D, Ridgeway T M, Pelletier S L. Computer-aided interpretation of analytical sedimentation data for proteins. In: Harding S E, Rowe A J, Horton J C, editors. Analytical ultracentrifugation in biochemistry and polymer science. England: Redwood Press; 1992. p. 90. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lipscomb J D, Hooper A B. Resolution of multiple heme centers of hydroxylamine oxidoreductase from Nitrosomonas. 1. Electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1982;21:3965–3972. doi: 10.1021/bi00260a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Long A R, Anthony C. Characterization of the periplasmic cytochromes c of Paracoccus denitrificans: identification of the electron acceptor for methanol dehydrogenase, and description of a novel cytochrome cheterodimer. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:415–425. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-10-2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lontoh S, Semrau J D. Methane and trichloroethylene degradation by Methylosinus trichosporiumOB3b. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1106–1114. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.3.1106-1114.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lowry O H, Rosebrough N J, Farr A L, Randall R J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McDonnel A, Staehelin L A. Detection of cytochrome f, a c-class cytochrome, with diaminobenzidine in polyacrylamide gels. Anal Biochem. 1981;117:40–44. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(81)90688-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moura I, Fayque G, LeGall J, Xavier A V, Moura J J G. Characterization of the cytochrome system of a nitrogen-fixing strain of a sulfate-reducing bacterium: Desulfovibrio desulfuricansstrain Berre-Eau. Eur J Biochem. 1987;162:547–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb10674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nielsen A K, Gerdes K, Degn H, Murrell J C. Regulation of bacterial methane oxidation: transcription of the soluble methane monooxygenase operon of Methylococcus capsulatus(Bath) is repressed by copper ions. Microbiology. 1996;142:1289–1296. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-5-1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Odom J M, Peck H D., Jr Hydrogenase, electron transfer proteins, and energy coupling in the sulfate-reducing bacteria Desulfovibrio. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1984;38:551–591. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.38.100184.003003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pedersen J Z, Finazzi-Agro A. Protein-radical enzymes. FEBS Lett. 1993;325:53–58. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81412-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pereira I A, Pacheco I, Liu M-Y, LeGall J, Xavier A V, Teixeira M. Multiheme cytochromes from the sulfate-reducing bacterium Desulfovibrio acetoxidans. Eur J Biochem. 1997;248:323–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prior S D, Dalton H. The effect of copper ions on the membrane content and methane monooxygenase activity in methanol-grown cells of Methylococcus capsulatus(Bath) J Gen Microbiol. 1985;131:155–163. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saraiva L M, Lui M Y, Payne W J, LeGall J, Moura J, Moura I. Spin-equilibrium and heme-ligand alteration in a high-potential monoheme cytochrome (cytochrome c554) from Achromobacter cycloclastes, a denitrifying organism. Eur J Biochem. 1990;189:333–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Saraiva L M, Denariaz G, Liu M Y, Payne W J, LeGall J, Moura I. NMR and EPR Studies on a monoheme cytochrome c550 isolated from Bacillus halodenitrificans. Eur J Biochem. 1992;204:1131–1139. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Semrau J D, Chistoserdov A, Lebron J, Costello A, Davagnino J, Kenna E, Holms A, Finch R, Murrell J C, Lidstrom M E. Particulate methane monooxygenase genes in methanotrophs. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3071–3079. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.11.3071-3079.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith D S, Costello A A, Lidstrom M E. Methane and trichloroethylene oxidation by an esturarine methanotroph, Methylobactersp. strain BB5.1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4617–4620. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.11.4617-4620.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Speer B S, Chistoserdova L, Lidstrom M E. Sequence of the gene for a NAD(P)-dependent formaldehyde dehydrogenase (class III alcohol dehydrogenase) from a marine methanotroph Methylobacter marinusA45. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;121:349–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stanley S H, Prior S D, Leak J D, Dalton H. Copper stress underlines the fundamental change in intracellular location of methane mono-oxygenase in methane utilizing organisms: studies in batch and continuous cultures. Biotechnol Lett. 1983;5:487–492. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stirling D I, Dalton H. Purification and properties of an NAD(P)+-linked formaldehyde dehydrogenase from Methylococcus capsulatus(Bath) J Gen Microbiol. 1978;107:19–29. doi: 10.1099/00221287-107-1-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van Rooijen G J H, Bruschi M, Voordouw G. Cloning and sequencing of the gene encoding cytochrome c553 from Desulfovibrio vularisHildenborough. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:3575–3578. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.6.3575-3578.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.von Heijne G. Membrane protein structure prediction, hydrophobicity analysis, and the positive inside rule. J Mol Biol. 1992;225:487–494. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90934-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Waechter-Brulla D, DiSpirito A A, Chistoserdova L V, Lidstrom M E. Methanol oxidation genes in the marine methanotroph Methylomonassp. strain A4. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3767–3775. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.12.3767-3775.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wallar B J, Lipscomb J D. Dioxygen activation by enzymes containing dinuclear non-heme iron clusters. Chem Rev. 1996;96:2625–2657. doi: 10.1021/cr9500489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yagi T. Purification and properties of cytochrome c553, an electron acceptor for formate dehydrogenase of Desulfovibrio vulgaris, Miyazaki. Biochim Biophys Res Commun. 1979;86:1020–1029. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(79)90190-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zahn J A, DiSpirito A A. The membrane-associated methane monooxygenase from Methylococcus capsulatusBath. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1018–1029. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.4.1018-1029.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zahn, J. A., and A. A. DiSpirito. 1998. Unpublished results.

- 63.Zahn J A, Duncan C, DiSpirito A A. Oxidation of hydroxylamine by cytochrome P460 of the obligate methylotroph Methylococcus capsulatusBath. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5879–5887. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.19.5879-5887.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zahn J A, Arciero D M, Hooper A B, DiSpirito A A. Cytochrome c′ of Methylococcus capsulatusBath. Eur J Biochem. 1996;240:664–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0684h.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zahn J A, Arciero D M, Hooper A B, DiSpirito A A. Cytochrome c peroxidase of Methylococcus capsulatusBath. Arch Microbiol. 1997;168:362–372. doi: 10.1007/s002030050510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]