Abstract

Unlike classically defined insertion sequence (IS) elements, which are delimited by their inverted terminal repeats, some IS elements do not have inverted terminal repeats. Among this group of atypical IS elements, IS116, IS900, IS901, and IS1110 have been proposed as members of the IS900 family of elements, not only because they do not have inverted terminal repeats but also because they share other features such as homologous transposases and particular insertion sites. In this study, we report a newly identified IS sequence, IS1547, which was first identified in a clinical isolate of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Its structure, insertion site, and putative transposase all conform with the conventions of the IS900 family, suggesting that it is a new member of this family. IS1547 was detected only in isolates of the M. tuberculosis complex, where it had highly polymorphic restriction fragment length polymorphism patterns, suggesting that it may be a useful genetic marker for identifying isolates of the M. tuberculosis complex and for distinguishing different strains of M. tuberculosis. ipl is a preferential locus for IS6110 insertion where there are eight known different insertion sites for IS6110. Surprisingly, the DNA sequence of ipl is now known to be a part of IS1547, meaning that IS1547 is a preferential site for IS6110 insertion.

Bacterial insertion sequences (ISs) are genetic entities which are able to translocate to new genetic locations either within a replicon or between different replicons in the host cell. Typically, IS elements are 0.7 to 2.5 kb in length and end in perfect or nearly perfect inverted terminal repeats, which are proposed to play a role in transposition and in the selection of insertion targets. ISs encode only proteins related to their transposition activity, such as transposases. With few exceptions, IS elements generate a duplication of the DNA sequence at the insertion site on transposition; thus, after insertion, the duplication borders the IS element as a direct repeat (for a review, see reference 7).

Unlike classically defined IS elements, which are delimited by their inverted terminal repeats, some IS elements, for example, IS900 identified in Mycobacterium paratuberculosis (8) and IS901 and IS1110 from Mycobacterium avium (10, 12), do not have these repeats. Other IS elements without inverted terminal repeats include IS1000 from Thermus thermophilus (2), IS116 from Streptomyces clavuligerus (14), IS117 from Streptomyces coelicolor (9), and HBSI from Bradyrhizobium japonicum (11). Among these atypical IS elements, IS116, IS900, IS901, and IS1110 have been proposed as members of a group of closely related IS elements, designated the IS900 family, not only because they do not have inverted terminal repeats but because they share other features as well, such as homologous transposases and particular insertion sites (10). Since inverted terminal repeats are believed to be important in the selection of target sites and in the mechanics of transposition of IS elements (7), greater understanding of this group of atypical IS elements is important for the elucidation of transposition and the evolution of insertion sequences.

ipl is a hot spot for IS6110 insertion in the genome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (EMBL, GenBank, and DDBJ database accession no. X95799 [5]). At this locus we have extended the DNA sequence of ipl on each side to 2732 nucleotides (nt) in clinical isolate M. tuberculosis 151, an isolate which does not harbor an IS6110 copy in ipl. Analysis of this DNA sequence revealed several open reading frames (ORFs), and translation products of these were used in searches of protein databases with BLAST (1). One of the translated amino acid sequences, ORF1, showed significant homology to several peptide sequences, most of which were transposases, such as those from IS116 (BLAST score of more than 1.1 × 10−16) from S. clavuligerus, IS1110 (4.2 × 10−10) from M. avium, IS901 (2.3 × 10−10) from M. avium, IS900 (1.6 × 10−10) from M. paratuberculosis, and IS110 (5.6 × 10−9) from S. coelicolor. Consequently, along with having other features (see below), the translation product of ORF1 is proposed to be the transposase of a new IS element, designated IS1547.

Two different insertion sites of IS1547 from two clinical isolates were identified and sequenced. Sequence comparison of the DNAs from these two insertion sites, together with ORF1 peptide sequence common to both of these two sites (see below), revealed that IS1547 is 1351 nt in length without terminal inverted repeats but with target direct repeats (CCTT) in Y13470 and imperfect direct repeats (CCTT/CCTC) in Y16254. These two insertion sites were also found in the genome of M. tuberculosis H37Rv, which is being sequenced (14a).

Two large ORFs, ORF1 and ORF2, were identified in the DNA sequence of IS1547. ORF1 has no stop codon within the DNA sequence of IS1547. The predicted translation product of ORF1 of IS1547 itself was considered the peptide sequence which is common to the ORF1s of IS1547 at the two insertion sites. This gave a 380-amino-acid peptide of about 41 kDa in mass. In accession no. Y13470, ORF1 was 1182 nt long with a stop codon outside the IS1547 sequence, giving three extra amino acid residues at the C terminus of the peptide; ORF1 of IS1547 in Y16254 was even longer. The use of flanking DNA sequences to provide the stop codon for an ORF has also been observed in IS1110 of M. avium (10) and in IS870 of Agrobacterium vitis, which uses its specific insertion site (CTAG) to generate the stop codon (6). The use of external stop codons to terminate ORFs of IS elements is thus not uncommon and is not limited to the IS900 family of elements; however, the reason for this strategy is not clear.

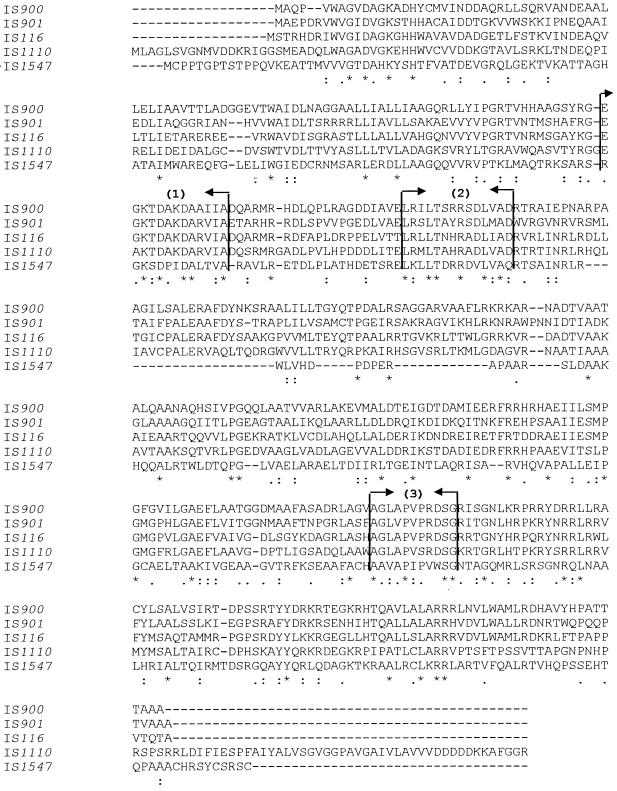

The transposases of the IS900 family of elements have been reported to have two conserved peptide regions, one of which is a motif found in reverse transcriptases (region 1 in Fig. 1) (12), the other of which shows homology to a motif involved in inverting DNA (region 3 in Fig. 1) (10). Comparison of the sequences of the IS1547 ORF1 peptide and the transposases of the other members of the IS900 family revealed the presence of both of these conserved peptide regions in the IS1547 ORF1 peptide. In addition, the comparison disclosed a third conserved region (region 2 in Fig. 1) with the consensus sequence L--LT--R--L-A. This consensus sequence did not significantly match sequences in the motif database PROSITE (released in November 1995; Amos Bairoch, Medical Biochemistry Department, University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland). These three motifs further support the function of ORF1 as the transposase of IS1547.

FIG. 1.

Amino acid sequence alignment of the translation product of IS1547 ORF1 and the transposases of the IS elements of the IS900 family, derived via program Clustal W (version 1.7). The ∗ symbols in the conservation line indicate the positions where there are identical residues across all the amino acid sequences; colons indicate strongly conserved residues, and period indicate weakly conserved residues (16). The three regions indicated by numbers and delimited with bent arrows are conserved regions in the IS900 family, one of which (region 1) was found to contain the motif in reverse transcriptase and the other of which (region 3) has the motif involving DNA inversion (Kunze et al. [12] and Hernandez Perez et al. [10]). See the text for more details.

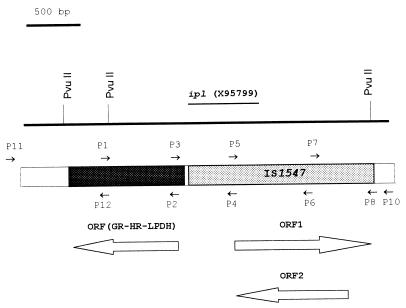

A second large ORF, ORF2, of IS1547 is on the DNA strand complementary to and overlapped by ORF1, and these two ORFs share their third codon positions (Fig. 2). It is predicted that ORF2 encodes a peptide of 296 amino acids (Y13470:e339203) with a molecular mass of about 32 kDa. A second ORF is also found in IS900 and IS116, both of which are again on the strand complementary to ORF1, while this ORF is not found in IS1110 (8, 10). The IS1547 ORF2 translation product showed only 45% similarity and 23% identity to IS900 ORF2, suggesting little similarity between these peptides. In addition, a protein database search of the IS1547 ORF2 translation product did not recover any significantly similar peptides.

FIG. 2.

Schematic illustration of the IS1547 insertion site in accession no. Y13470, restriction map of the DNA sequence (EMBL, GenBank, and DDBJ accession no. Y13470), and location of ipl (EMBL, GenBank, and DDBJ accession no. X95799). The smaller arrows represent primers used in this study, while the larger, open arrows indicate locations of the ORFs. There are three restriction sites for PvuII within this DNA fragment, as presented in the line, and there are 17 sites for AluI, but there are no restriction sites for AsnI, DraI, and HindIII. GR, glutathione reductase; HR, mercuric reductase; LPDH, dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase.

IS1547 shares several features with members of the IS900 family of elements; one of them is that they tend to insert into the promoter regions of genes (10). In the sequences flanking the two IS1547 copies, ORFs were identified on the complementary strand at the 5′ end of the IS1547 copies, with their direction of expression opposite to that of the putative transposase of IS1547 (Fig. 2). The ORF in accession no. Y16254 encoded a peptide of 172 amino acids (Y16254:e1240541) which had no significant matches in protein database searches. However, the ORF in Y13470 encoded a 499-amino-acid peptide (Y13470:e3215020) which showed strong homology (BLAST scores of more than 10−28) to enzymes of the pyridine nucleotide-disulfide oxidoreductase class I family, including seven mercuric reductases, four glutathione reductases, and four dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase, all from different species.

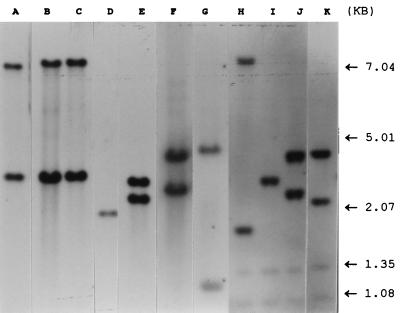

To examine the distribution of IS1547 in mycobacteria, a digoxigenin-labelled IS1547 probe was applied to Southern blots of PvuII-digested genomic DNAs of the following isolates: 61 isolates of M. tuberculosis, including strain H37Ra and IS6110 restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) reference strain Mt14323; 3 isolates of M. bovis; 2 vaccine strains of M. bovis BCG (Glaxo and Copenhagen) and 3 clinical isolates of M. bovis BCG; 2 isolates of Mycobacterium africanum; 3 isolates of M. avium; and 1 isolate each of M. paratuberculosis, Mycobacterium malmoense, Mycobacterium fortuitum, Mycobacterium marinum, and Mycobacterium kansasii. The results suggest the following. (i) Hybridizing DNA fragments were found in all of the isolates of M. tuberculosis, M. bovis, M. bovis BCG, and M. africanum (Fig. 3) but not in any of the M. avium, M. paratuberculosis, M. malmoense, M. fortuitum, M. marinum, or M. kansasii isolates. IS1547 may therefore be useful as a genetic marker in distinguishing the M. tuberculosis complex from other mycobacterial species. (ii) Within the isolates of the M. tuberculosis complex, many different IS1547 RFLP patterns were observed; for example, three clinical isolates of M. bovis BCG had two IS1547 copies with the same banding pattern (Fig. 3, lane B), while the vaccine strains of M. bovis BCG (Glaxo and Copenhagen) had a slightly different banding pattern (Fig. 3, lane A versus lane B). Unlike in M. bovis, the IS1547 banding patterns in M. africanum and M. tuberculosis exhibited a totally different picture.

FIG. 3.

Autoradiograph of a Southern blot of PvuII-digested chromosomal DNA of mycobacterial isolates probed with a digoxigenin-labelled IS1547 probe. Lane A, M. bovis BCG (Glaxo); lane B, clinical isolate 8189/96 of M. bovis BCG; lane C, clinical isolate B1 of M. bovis; lane D, clinical isolate L2523 of M. africanum; lane E, clinical isolate 11804/93 of M. africanum; lane F, type strain H37Ra of M. tuberculosis; lane G, IS6110 RFLP reference strain mtb14323 of M. tuberculosis; lanes H to K, clinical isolates 9407, 9212, 9308, and 9101 of M. tuberculosis. Faint bands in lanes H to K are internal size standards.

ipl was identified as a preferential locus in the genome of M. tuberculosis for IS6110 insertions (5). In addition to the six different insertion sites (ipl-1::IS6110 to ipl-6::IS6110) described previously, two more have since been found: ipl-7::IS6110 (Y14613) and ipl-8::IS6110 (Y14614). It is now apparent that the original ipl locus is in fact in the DNA sequence of IS1547 and is located at nt 1718 to 2370 of sequence Y13470 (Fig. 3) and that there are two such sites in the genomes of many M. tuberculosis isolates. That is to say, IS1547 is a preferential site for IS6110 insertion. Interactions between IS elements have also been observed in other bacteria, although they have been poorly studied. For instance, IS53 from a plasmid of Pseudomonas syringae subsp. savastanoi was found to insert into IS51 (15) and the target of ISRm3 transposition in Rhizobium meliloti is the insertion sequence ISRm5 (13). Recently, the genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12 (3) revealed that two IS911-related sequences (IS911A and IS911B) had been interrupted by IS30 and IS600. Further investigations are being carried out to clarify the basis of the interaction between IS1547 and IS6110 and its implications for transposition and strain similarity assessments based on these elements.

Nucleotide and peptide sequence accession numbers.

DNA fragments sequenced in this study have been deposited in the EMBL, GenBank, and DDBJ data banks under accession no. Y13470, Y14613, Y14614, and Y16254. Predicted peptide sequences have been deposited in TREMBL data bank under accession no. Y13470:e3215020 and Y13470:e339203.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Rayner and G. Harris at the Scottish Mycobacteria Reference Laboratory for bacteriological assistance, P. Carter, and K. Reay for DNA sequencing and synthesis of the oligonucleotide primers. DNA sequence analysis benefited from SEQNET, the SERC facility (Daresbury, United Kingdom).

This study was financially supported by the Department of Health, the Scottish Office; Chest, Heart and Stroke Scotland; and a Milner Scholarship from the University of Aberdeen.

Footnotes

Present address: Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Bradford, Bradford, West Yorkshire, BD7, 1DP, United Kingdom.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashby M K, Bergquist P L. Cloning and sequence of IS1000, a putative insertion sequence from Thermus thermophilus HB8. Plasmid. 1990;24:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(90)90020-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blattner F R, Plunkett III G, Bloch C A, Perna N T, Burland V, Riley M, Collado-Vides J, Glasner J D, Rode C K, Mayhew G F, Gregor J, Davis N W, Kirkpatrick H A, Goeden M A, Rose D J, Mau B, Shao Y. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science. 1997;277:1453–1474. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butler W R, Haas W H, Crawford J T. Automated DNA fingerprinting analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis using fluorescent detection of PCR products. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1801–1803. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.7.1801-1803.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fang Z, Forbes K J. A Mycobacterium tuberculosis IS6110 preferential locus (ipl) for insertion into the genome. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:479–481. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.2.479-481.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fournier P, Paulus F, Otten L. IS870 requires a 5′-CTAG-3′ target sequence to generate the stop codon for its large ORF1. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3151–3160. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.10.3151-3160.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galas D J, Chandler M. Bacterial insertion sequences. In: Berg D E, Howe M M, editors. Mobile DNA. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1989. pp. 939–958. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Green E P, Tizard M L, Moss M T, Thompson J, Winterbourne D J, McFadden J J, Hermon-Taylor J. Sequence and characteristics of IS900, an insertion element identified in a human Crohn’s disease isolate of Mycobacterium paratuberculosis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:9063–9073. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.22.9063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henderson D J, Lydiate D J, Hopwood D A. Structural and functional analysis of the mini-circle, a transposable element of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:1307–1318. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hernandez Perez M, Fomukong N G, Hellyer T, Brown I N, Dale J W. Characterization of IS1110, a highly mobile genetic element from Mycobacterium avium. Mol Microbiol. 1994;12:717–724. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Judd A K, Sadowsky M J. The Bradyrhizobium japonicum serocluster 123 hyperreiterated DNA region, HRS1, has DNA and amino acid sequence homology to IS1380, an insertion sequence from Acetobacter pasteurianus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:1656–1661. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.5.1656-1661.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kunze Z M, Wall S, Appelberg R, Silva M T, Portaels F, McFadden J J. IS901, a new member of a widespread class of atypical insertion sequences, is associated with pathogenicity in Mycobacterium avium. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:2265–2272. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb02157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laberge S, Middleton A T, Wheatcroft R. Characterization, nucleotide sequence, and conserved genomic locations of insertion sequence ISRm5 in Rhizobium meliloti. Comp Appl Biosci. 1995;3:239–241. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.11.3133-3142.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leskiw B K, Mevarech M, Barritt L S, Jensen S E, Henderson D J, Hopwood D A, Bruton C J, Chater K F. Discovery of an insertion sequence, IS116, from Streptomyces clavuligerus and its relatedness to other transposable elements from actinomycetes. J Gen Microbiol. 1990;136:1251–1258. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-7-1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14a.Sanger Centre Website. 1997, copyright date. [Online.] Sanger Centre, Wellcome Trust Genome Campus, Hinxton, Cambridge, United Kingdom. http://www.sanger.ac.uk. [December 1997, last date accessed.]

- 15.Soby S, Kirkpatrick B, Kosuge T. Characterization of an insertion sequence (IS53) located within IS51 on the iaa-containing plasmid of Pseudomonas syringae pv. savastanoi. Plasmid. 1993;29:135–141. doi: 10.1006/plas.1993.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence-weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]