Abstract

Blue cone monochromacy (BCM) is a congenital vision disorder affecting both middle-wavelength (M) and long-wavelength (L) cone photoreceptors of the human retina. BCM results from abolished expression of green and red light-sensitive visual pigments expressed in M- and L-cones, respectively. Previously, we showed that gene augmentation therapy to deliver either human L- or M-opsin rescues dorsal M-opsin dominant cone photoreceptors structurally and functionally in treated M-opsin knockout (Opn1mw−/−) mice. Although Opn1mw−/− mice represent a disease model for BCM patients with deletion mutations, at the cellular level, dorsal cones of Opn1mw−/− mice still express low levels of S-opsin, which are different from L- and M-cones of BCM patients carrying a congenital opsin deletion. To determine whether BCM cones lacking complete opsin expression from birth would benefit from AAV-mediated gene therapy, we evaluated the outcome of gene therapy, and determined the therapeutic window and longevity of rescue in a mouse model lacking both M- and S-opsin (Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/−).

Our data show that cones of Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− mice are viable at younger ages but undergo rapid degeneration. AAV-mediated expression of human L-opsin promoted cone outer segment regeneration and rescued cone-mediated function when mice were injected subretinally at 2 months of age or younger. Cone-mediated function and visually guided behavior were maintained for at least 8 months post-treatment. However, when mice were treated at 5 and 7 months of age, the chance and effectiveness of rescue was significantly reduced, although cones were still present in the retina. Crossing Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− mice with proteasomal activity reporter mice (UbG76V–GFP) did not reveal GFP accumulation in Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− cones eliminating impaired degradation of ubiquitinated proteins as stress factor contributing to cone loss. Our results demonstrate that AAV-mediated gene augmentation therapy can rescue cone structure and function in a mouse model with a congenital opsin deletion, but also emphasize the importance that early intervention is crucial for successful therapy.

Keywords: blue cone monochromacy, cone opsin, cone dystrophy, AAV, gene therapy, opsin knockout mice

INTRODUCTION

Blue cone monochromacy (BCM) is an X-linked congenital vision disorder, which manifests as severe reduction or complete loss of both long-wavelength (L) and middle-wavelength (M) cone functions, resulting from mutations in the OPN1LW/OPN1MW gene cluster. BCM almost exclusively affects males with an incidence of 1 in 100,000 individuals.1–5 BCM patients carrying deletion mutations have abolished expression of both L- and M-opsin, the main structural components and visual pigments for L- and M-cones, respectively.

BCM patients exhibit severely diminished color discrimination from birth and suffer from reduced visual acuity, myopia, pendular nystagmus, and photoaversion.6,7 Studies using Adaptive Optics Scanning Laser Ophthalmoscopy (AOSLO) demonstrate that BCM patients also have a disrupted foveal cone mosaic with a reduced number of cones. Although these remaining cones display significantly shortened outer segments, which contain fewer disk membranes, the overall residual structure suggests that a population of BCM cones remain viable despite their lack of opsin expression, making them a potentially viable target for gene therapy.8–10

Previously, we showed that gene augmentation therapy promoted regrowth of cone outer segments and rescued M-cone function in the treated M-opsin knockout (Opn1mw−/−) dorsal retina.11,12 Although the Opn1mw−/− mouse represents a disease model for BCM patients with deletion mutations and dorsal cones of Opn1mw−/− mice structurally resemble BCM cones with significantly shortened outer segments, there are two disadvantages of studying gene therapy using Opn1mw−/− mice. First, the majority of mouse cones coexpress both M- and S-opsin in a dorsal–ventral gradient, with dorsal cones predominantly expressing M-opsin and ventral cones predominantly expressing S-opsin.13,14 This expression pattern is different from human cones that express only one type of opsin per cone.15–18 While L- and M-cones from BCM patients lack complete opsin expression, dorsal M-opsin dominant cones of Opn1mw−/− mice still express low levels of S-opsin. Therefore, it is entirely possible that these low levels of S-opsin expression could potentially prolong the lifespan of dorsal cones and not reflect the true pathophysiology of BCM cones. Second, since Opn1mw−/− mice have normal S-cone structure and function, AAV-mediated expression of L/M-opsin in S-cones of Opn1mw−/− mice also generates long/middle wavelength electroretinography (ERG) signals that make it more difficult to interpret the outcome of gene therapy.

Deletion of both M-opsin (Opn1mw) and S-opsin (Opn1sw) results in complete loss of cone opsin expression in all cone photoreceptors of the Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− mouse retina. As a result, Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− mice completely lack photopic ERG responses, signifying that any observed increases in visual function are a direct reflection of functional rescue after gene therapy. In this study, we evaluated the outcome of AAV-mediated gene therapy in Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− mice treated at different ages and characterized the longevity of rescue. Our results provide proof of concept that gene augmentation can rescue function and structure in cones with congenital opsin deletion. However, our results also emphasize that early treatment may be crucial to achieve better therapeutic effect for BCM patients carrying deletion mutations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− mice were generated by crossing Opn1mw−/−12 and Opn1sw−/−14 mice. Genotyping of Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− mice was performed as described previously. The RhoP23H/P23H mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (stock # 017628). Transgenic mice heterozygously expressing the UbG76V–GFP (a fusion of ubiquitin with GFP containing a G76V mutation in the linker) reporter19 were obtained from the colony maintained by Dr. Ekaterina Lobanova (University of Florida, Gainesville, FL).

All animals used in this study were maintained in the University of Florida Health Science Center Animal Care Service Facilities in a dim light room 24/7. All animals were maintained under standard laboratory conditions (18–23°C, 40–65% humidity) with food and water available ad libitum. All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Florida and conducted in accordance with the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and National Institutes of Health regulations.

AAV vectors

The AAV vector expressing human OPN1LW driven by PR2.1 promoter (PR2.1-hOPN1LW) was described previously.20 This vector was packaged in AAV serotype 5 and was purified according to previously published methods.21

Subretinal injection

Before injection, 1% atropine drops (Akorn, Inc., Lake Forest, IL) and 2.5% phenylephrine HCl solution (Paragon BioTeck, Portland, OR) were applied to mouse eyes for dilation. Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal (IP) injection using xylazine (10 mg/kg) and ketamine (80 mg/kg) in sterile ringer buffer solution. Initially, a small hole is introduced at the edge of the cornea using a 30-gauge needle. Next, a transcorneal subretinal injection is performed using a 5 μL Hamilton syringe mounted with a 33-gauge blunt needle. Through the small entry hole in the cornea, the 33-gauge blunt needle is inserted and 1 μL of viral vector at a concentration of 1 × 1010 vector genomes per microliter mixed with fluorescein dye (0.1% final concentration) is injected into the subretinal space.22,23

The injection bleb was visualized by a fluorescence-positive subretinal signal. Only one eye per animal was injected, whereas the contralateral eye served as an uninjected control. Following injection, atropine eye drops and neomycin/polymyxin B/dexamethasone ophthalmic ointment (Bausch & Lomb, Inc., Tampa, FL) were applied. To reverse anesthesia after injection, antisedan (Orion Corporation, Espoo, Finland) was injected intramuscularly.

Electroretinography

Scotopic ERG and photopic ERG responses were analyzed using a UTAS Visual Diagnostic System with a Big Shot Ganzfeld dome (LKC Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD). Before ERG testing, mice were anesthetized with an IP injection of ketamine (72 mg/kg)/xylazine (4 mg/kg) and pupils were dilated using 1% atropine and 2.5% phenylephrine HCl drops.

For scotopic ERG, following overnight dark adaptation, each mouse was recorded at three stimulus light intensities (−1.6, −0.6, and 0.4 log cd·s/m2), 10 scotopic ERGs were recorded and averaged for each light intensity. For photopic ERG, mice were exposed to 30 cd/m2 white light for 5 min before performing photopic ERGs to suppress rod function. Cone-mediated ERG responses were recorded by stimulation with red channel long wavelength light (630 nm) at intensities of −0.6, 0.4, and 1.4 log cd·s/m2, followed by green channel middle wavelength light (530 nm) at intensities of −0.6, 0.4, and 1.4 log cd·s/m2, then short channel wavelength light (360 nm) at intensities of −0.6 and 0.4 log cd·s/m2.

Twenty-five recordings were averaged for each light intensity. Stimulation with long and middle wavelengths produced similar ERG results, and responses from red light were used to plot the figure and for statistical analysis. ERG data are presented as average ± SEM (standard error of the mean). Statistics were performed with one-way ANOVA with the Tukey's multiple comparisons test. Significance is defined as p < 0.05.

Visually guided behavior testing

The optokinetic reflexes of treated and untreated Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− mouse eyes were measured under photopic conditions (70 cd/m2) with Optometry (Cerebral Mechanics, Inc.) using a two-alternative forced choice paradigm as described previously.24,25 To test the sensitivity of individual eyes from the same animal we took advantage of the fact that mouse vision has minimal binocular overlap and that the left eye is more sensitive to clockwise rotation and the right to counterclockwise rotation.26 In our “randomize-separate” protocol, the response of each eye was determined separately and simultaneously through stepwise functions for correct responses in both the clockwise and counterclockwise directions. The highest spatial frequency (100% contrast) yielding a threshold response was identified. The initial stimulus was 0.200 cycles per degree sinusoidal pattern with a fixed 100% contrast. Measurements were taken from both eyes of each mouse twice over a period of 1 week. Age-matched wild-type mice were included as controls. Visual acuity is presented as average ± SEM. Statistics were performed with one-way ANOVA with the Tukey's multiple comparisons test. Significance is defined as p < 0.05.

Preparation of retinal whole mounts and peanut agglutinin staining

After mice were humanely euthanized, a cautery tool (Braintree Scientific, Braintree, MA) was used to burn a mark on the cornea at the dorsal position. Following enucleation, a small hole was poked on the edge of the cornea and the eyes were fixed for 2 h with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at room temperature. To prepare flat mounts, the cornea and lens were subsequently removed and the retina was meticulously dissected from the eyecup. Next, four radial cuts were made from the dorsal, temporal, nasal, and ventral edges of the retina toward the central retina. Flat mounts were then blocked for 2 h in 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS. Retinal flat mounts were then labeled overnight with biotinylated peanut agglutinin (PNA) (1:500 dilution; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) in 1X PBS. The following day, retinal flat mounts were washed three times in PBS before incubating for 2 h at room temperature with Fluorescein Avidin D (Vector Laboratories) at a 1:500 dilution in PBS.

Finally, flat mounts were flattened onto slides using a fine brush and VECTASHIELD Mounting Medium for Fluorescence (H-1400; Vector Laboratories) was added before covering the flat mount with a coverslip. To image the flat mounts, a Leica Fluorescence Microscope LAS X Widefield System was utilized. A total of four images were taken for each retinal flat mount, including two from the ventral area and two from the dorsal area. From each individual image, cells positively labeled for PNA were counted in an area equivalent to 0.01 mm2 of retina using the counting tool in Adobe Photoshop. Counts of 12 images from both the dorsal and ventral regions of 6 different mice (3 males, 3 females) were then averaged and the standard deviation was calculated. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons test to compare difference among each group for dorsal or ventral regions. Significance was defined as a p-value of <0.05.

Frozen retinal section preparation and immunohistochemistry

After euthanasia, a cautery tool (Braintree Scientific, Braintree, MA) was used to burn a mark on the cornea at the 12 o'clock position. Eyes were subsequently enucleated at ambient light conditions, and a small hole was made at the cornea using an 18-gauge needle. Eyes were then incubated in 4% PFA in PBS for 2 h at room temperature before the cornea and lens were carefully removed. Eyecups were then washed with 1 × PBS and left to incubate in 30% sucrose overnight at 4°C for cryoprotection. The following day, eyecups were embedded and frozen in Tissue-Tek O.C.T compound (Sakura Finetek USA, Inc., Torrance, CA) and stored at −80°C. Samples were sectioned perpendicularly at 12 μm thickness from the dorsal to the ventral region using a cryostat. For immunohistochemistry applications, retinal cross-sections were hydrated in 1 × PBS and incubated for 1 h in blocking buffer containing 3% BSA and 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS at room temperature. Following blocking, sections were incubated in primary antibodies overnight at 4°C.

The following primary antibodies were used: anti-cone arrestin (a gift from Dr. Clay Smith at University of Florida), anti-L/M-opsin (1:1,000 dilution, AB5405; MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA), anti-S-opsin (1:1,000 dilution, AB5407; MilliporeSigma), anti-L/M-opsin (1:1,000, EJH006; Kerafast, Inc., Boston, MA), anti-PDE6α′ (1:200, AP9728c; ABgene, Portsmouth, NH), anti-cone transducin alpha subunit (GNAT2 I-20, 1:500, sc-390; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas TX), and anti-cone transducin γ subunit (a gift from Dr. Arshavsky's laboratory, Duke University). Next, slides were washed three times in 1 × PBS and incubated for 2 h at room temperature in Alexa-594 or Alexa-488 IgG secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) at a 1:500 dilution in PBS. PNA labeling was performed with biotinylated PNA (1:500 dilution; Vector Laboratories) in 1 × PBS overnight, followed by incubation with Fluorescein Avidin D (Vector Laboratories) at a 1:500 dilution in PBS. After three final washes in PBS, VECTASHIELD Mounting Medium for Fluorescence (H-1400; Vector Laboratories) was added, and sections were coverslipped. Slides were imaged using a Leica Fluorescence Microscope LAS X Widefield System.

An accumulation of UbG76V-GFP reporter in Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/−/UbG76V-GFP and RhodopsinP23H/WT/UbG76V-GFP mice and controls was assessed in 10 μm-thick frozen retinal sections. Cones were labeled with PNA (Rhodamine, RL-1072-5; Vector Laboratories). Outer segments of the rods were stained with Wheat Germ Agglutinin (Alexa Fluor 555 Conjugate, W32464). Sections were imaged on Leica TCS SP8 confocal microscope. Some Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/−/UbG76V-GFP and control slides were also costained with an anti-GFP antibody (ab13970; Abcam) and imaged using the same settings.

Western blot analysis

Three retinas from each injection group (untreated, treated, and wild-type) were carefully dissected and homogenized by sonication in buffer containing 0.23 M sucrose, 5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), and cOmplete™ protease inhibitors (Millipore Sigma, Burlington, MA). Retinal lysate was then centrifuged and divided into aliquots containing equal protein concentrations (50 μg). Each aliquot of retinal extract was analyzed by gel electrophoresis on a 4–15% polyacrylamide–SDS (sodium dodecyl sulfate) gel (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA). Next, proteins were transferred to an Immobilon-FL membrane (MilliporeSigma). Membranes were blocked with blocking buffer before being probed with an anti-red/green opsin antibody (AB5405; MilliporeSigma) and an anti-a-tubulin antibody (ab4074; Abcam), which served as an internal loading control. An Odyssey Infrared Fluorescence Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) was used to image membranes and visualize specific bands.

RESULTS

Characterizing the structure and morphology of the Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− retina

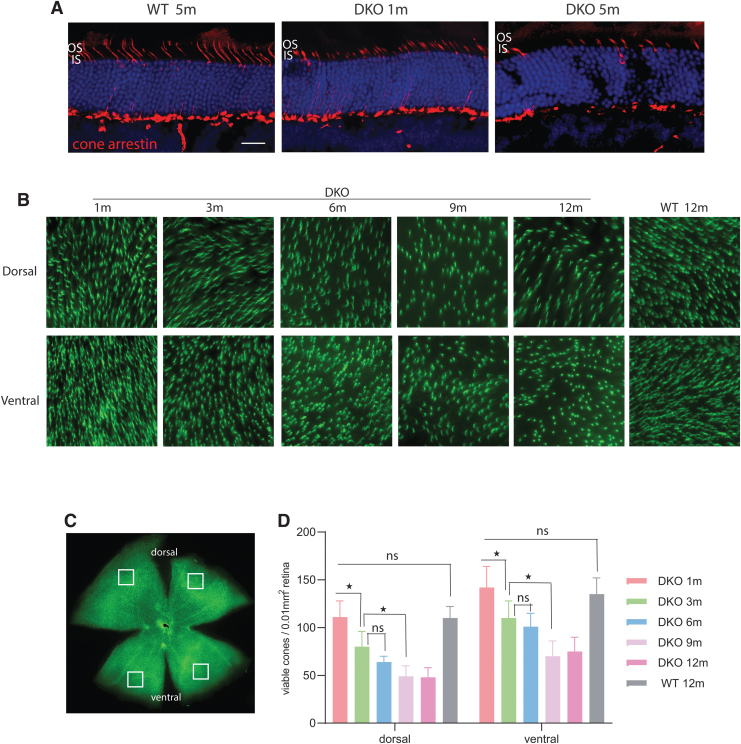

We first examined the cone structure of Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− knockout mice at 1 and 5 months of age by cone arrestin staining (Fig. 1A). Cone arrestin staining was only observed in synaptic terminals, axons, cell bodies, and inner segments. No staining was observed in cone outer segments, consistent with no or significantly shortened cone outer segments in Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− eyes. Furthermore, fewer numbers of cone arrestin-positive cells were visualized in 5-month-old compared with 1-month-old Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− eyes. In contrast, cone arrestin staining in wild-type eyes extends from synaptic terminals all the way into outer segments.

Figure 1.

Cone outer segments are not developed and cones degenerate early in Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− DKO mice. (A) Retinal cross-sections from wild-type and DKO retinas demonstrate that cone arrestin staining is absent from cone outer segments in DKO retinas, which have no or significantly shortened cone outer segments. Scale bar: 20 μm. (B–D) A time course of cone degeneration in DKO mice by PNA staining (green) of retinal flat mounts. (B) Representative images of retinal flat mounts taken from dorsal and ventral regions of WT and DKO retinas at different ages (1, 3, 6, 9, 12 months) stained with PNA (green). (C) Cone density was analyzed in four different regions from flat mounts, as indicated by the overlaid squares. (D) Quantification of cone density from dorsal and ventral regions of DKO and WT control retinas at different ages. Each bar represents PNA-positive signals counted in 0.01 mm2 of surface area of retina from 12 images taken from 6 different mice. Data show average ± SD. *p < 0.001; ns, no significance. DKO, double knockout; IS, inner segments; OS, outer segments; PNA, peanut agglutinin; SD, standard deviation; WT, wild-type.

We then investigated the rate of cone degeneration by PNA staining of retinal whole mounts in 1-, 3-, 6-, 9-, and 12-month-old Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− mice (Fig. 1B–D). PNA specifically binds to extracellular glycoprotein matrix of cone outer and inner segment sheaths and is an indicator of cone viability.27 From our previous study as well as from other reports,13,14,28,29 it has been shown that the cone density is between 10,000 and 14,000 cones/mm2 of retina, and there is no statistical difference in cone densities between young and aged wild-type mice. We show in this study that at 1 month of age, the cone density in the dorsal and ventral regions of the Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− retina is very similar to wild type (n = 6 mice, p > 0.05) (Fig. 1D).

At 3 months, the dorsal and ventral regions of Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− retinas contain significantly fewer viable cones compared with wild type, with a 28% reduction of viable cones in the dorsal region and 23% reduction in the ventral region of the retina (p < 0.001 for both dorsal and ventral). By 6 months of age, the number of viable cones in the dorsal and ventral regions of Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− retinas is reduced by 43% and 30%, respectively. While cones do continue to degenerate after 6 months of age, the remaining viable cones in the Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− retina do become stabilized by 9 months of age.

Furthermore, rod function and morphology were examined in aged Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− mice, both of which appear to be normal and preserved at all tested ages. Scotopic ERG measurements show no significant b-wave amplitude reduction in 9-month-old Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− mice (Supplementary Fig. S1A). In consistency, optical coherence tomography measurements showed no obvious reduction of retinal thickness (Supplementary Fig. S1B) and bright field fundus imaging showed no obvious morphology defects at 7 months of age (Supplementary Fig. S1C).

Assessing gene therapy outcome in Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− mice injected at different ages

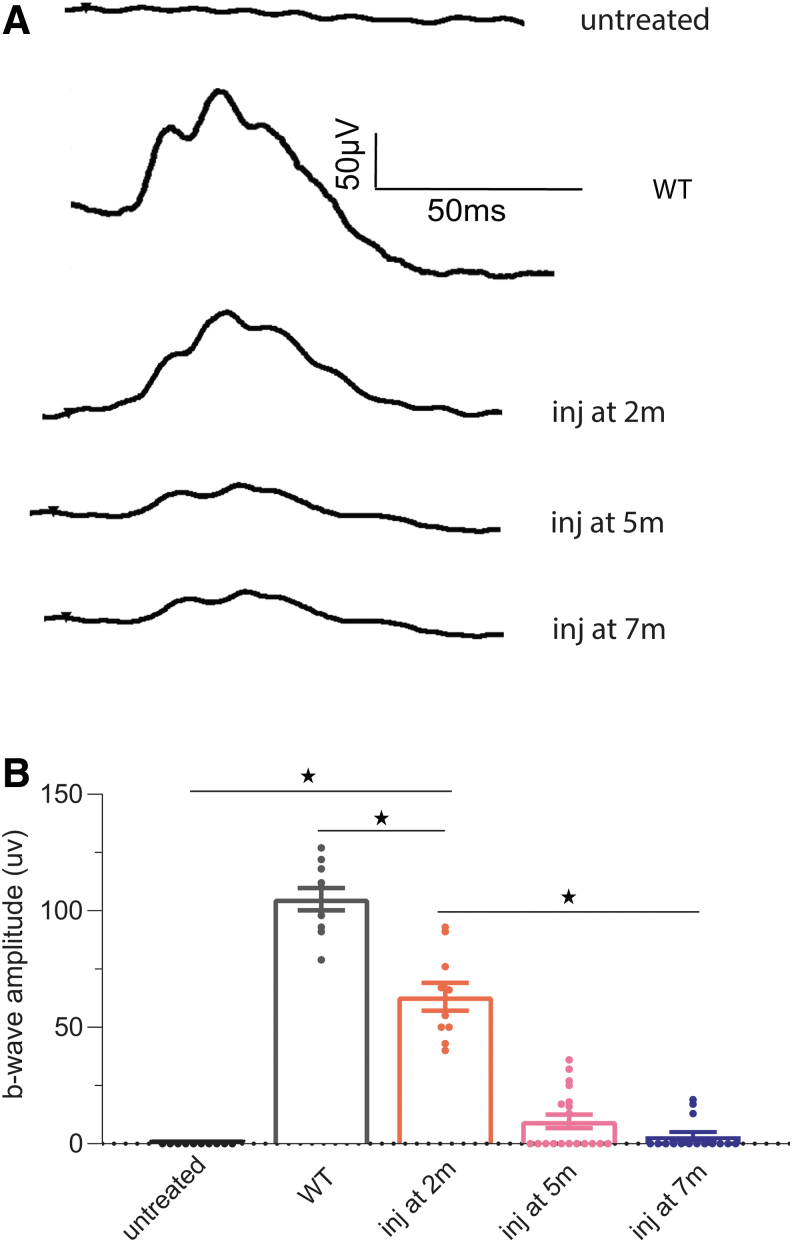

Cones of Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− mice lack opsin expression from birth, have no or significantly shortened cone outer segments, and do not generate photopic ERG responses. To investigate whether Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− cones are capable of being rescued and the rescue efficacy at different ages, we injected an AAV5 vector expressing OPN1LW driven by the cone-specific human promoter PR2.130 at 2, 5, and 7 months of age. The AAV vector was injected subretinally in one eye, with the contralateral eye remaining uninjected as a control. ERG was performed 4 weeks postinjection. Untreated Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− eyes lack middle-, long-, and short-wavelength-mediated photopic ERG responses. We found that when injected at 2 months of age, all injected eyes demonstrated significantly improved both middle- and long-wavelength-mediated ERG responses (Fig. 2). At light intensity of 1.4 log cd·s/m2, the averaged maximum b-wave amplitude measured at a long light wavelength of 630 nm was 63 ± 6 μV (n = 10, average ± SEM), significantly higher than the undetectable ERGs from contralateral uninjected eyes (p < 0.0001), and was 60% of wild-type ERG responses (105 ± 4 μV, n = 10, average ± SEM, p < 0.0001).

Figure 2.

(A) Representative long-wavelength ERG traces from untreated Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− retinas at 1-month-old, Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− eyes treated at 2, 5, and 7 months of age, as well as wild-type controls at light intensity of 1.4 log cd·s/m2. (B) Averaged long-wavelength-mediated ERG responses in Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− mice treated at different ages. ERG was performed 4 weeks after injection. The number of mice from each group are: untreated Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− (n = 10), Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− eyes treated at 2 months (n = 10), 5 months (n = 19), and 7 months (n = 15), WT controls (n = 10). Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of cone mediated b-wave amplitudes recorded at 630 nm at 1.4 log cd·s/m2. *p < 0.0001. ERG, electroretinography; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Alternatively, when Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− mice were injected at older ages, the rescue rate significantly decreased. ERG responses from mice injected at 5 and 7 months of age were both significantly lower than those treated at 2 months of age (p < 0.0001). When injected at 5 months of age, only 42% (8 out of 19) of injected Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− eyes showed measurable ERG rescue, with the averaged b-wave amplitude from those rescued eyes being 23 ± 8 μV (1.4 log cd·s/m2, n = 8, average ± SEM). When injected at 7 months of age, only 20% (3 out of 15) of treated eyes showed discernable improvements to photopic ERG response, with average b-wave amplitudes from rescued eyes only reaching 16 ± 9 μV (1.4 log cd·s/m2, n = 3, average ± SEM). ERG responses measured at 0.4 log cd·s/m2 showed similar results (Supplementary Fig. S2). Our results demonstrate that although ∼50% of cones are still present in Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− retinas at 7 months, these remaining cones are unable to be rescued in the majority of the mice investigated.

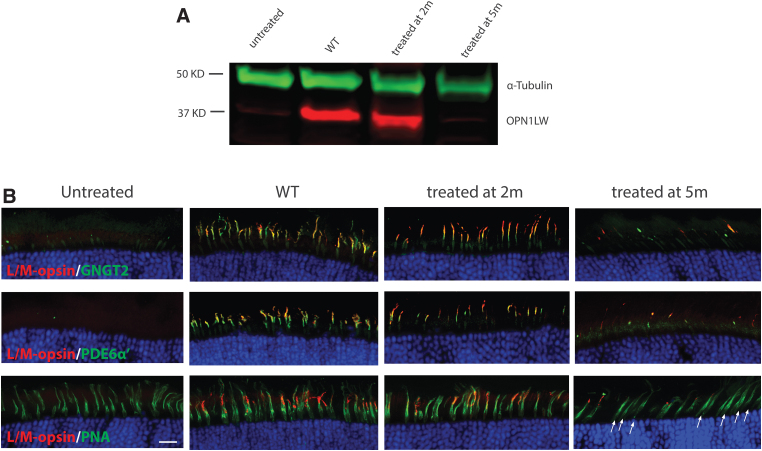

Western blot analysis was performed to evaluate the levels of AAV-mediated OPN1LW expression in Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− eyes treated at different ages using an antibody recognizing both human OPN1LW and mouse OPN1MW (Fig. 3A). Untreated eyes showed no endogenous OPN1MW expression (a very faint band was observed at the same size as OPN1MW most likely due to nonspecific binding since no M-opsin staining was observed in untreated Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− eyes by immunohistochemistry using the same antibody). AAV-mediated OPN1LW expression was clearly detectible in Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− eyes injected at 2 months of age, while expression was barely observed in eyes injected at 5 months of age.

Figure 3.

Expression levels and subcellular localization of AAV-mediated OPN1LW expression in Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− retinas treated at different ages. Retinas, which demonstrated ERG rescue were pooled 1 month postinjection from mice treated at different ages. (A) Western blot of OPN1LW expression (red) in Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− eyes injected at different ages and analyzed 4 weeks postinjection. An anti-α-tubulin (green) antibody was used as loading control. (B) Immunohistochemistry of retinal cross-sections from untreated and Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− eyes treated at different ages stained with antibodies against OPN1LW (red) together with cone outer segment-specific proteins GNGT2 (green, top row), PDE6α′ (green, middle row), or PNA (bottom row). Scale bar: 20 μm.

We also performed immunohistochemistry to analyze transgene expression at the subcellular level and examine cone outer segment structure in mice treated at different ages (Fig. 3B). In untreated Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− retinal sections, neither OPN1SW, OPN1MW, nor the cone outer segment-specific proteins cone transducin γ subunit (GNGT2) or phosphodiesterase α′ subunit (PDE6C or PDE6α′) were detected (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. S3). In eyes treated at 2 months of age, AAV-mediated OPN1LW expression spanned across each entire retina. OPN1LW expression was detected specifically in cone outer segments, where it colocalized with GNGT2 (Fig. 3B, top panel) and PDE6α′ (Fig. 3B, middle panel), suggesting that treatment restored cone outer segment growth.

OPN1LW expression was also localized at the tip of PNA staining (Fig. 3B, bottom panel). In eyes treated at 5 months of age, only a small fraction of cones showed the same expression pattern of OPN1LW, GNGT2, and PDE6α′ compared with eyes treated at 2 months of age. More importantly, although there were plenty of viable cones (indicated by PNA staining) in 5-month-old Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− retinas (Fig. 3B, bottom, fourth column), the majority of these cones demonstrated lack of OPN1LW, GNGT2, or PDE6α′ staining. This absence of staining suggests that most of these cones are barely rescuable at this age.

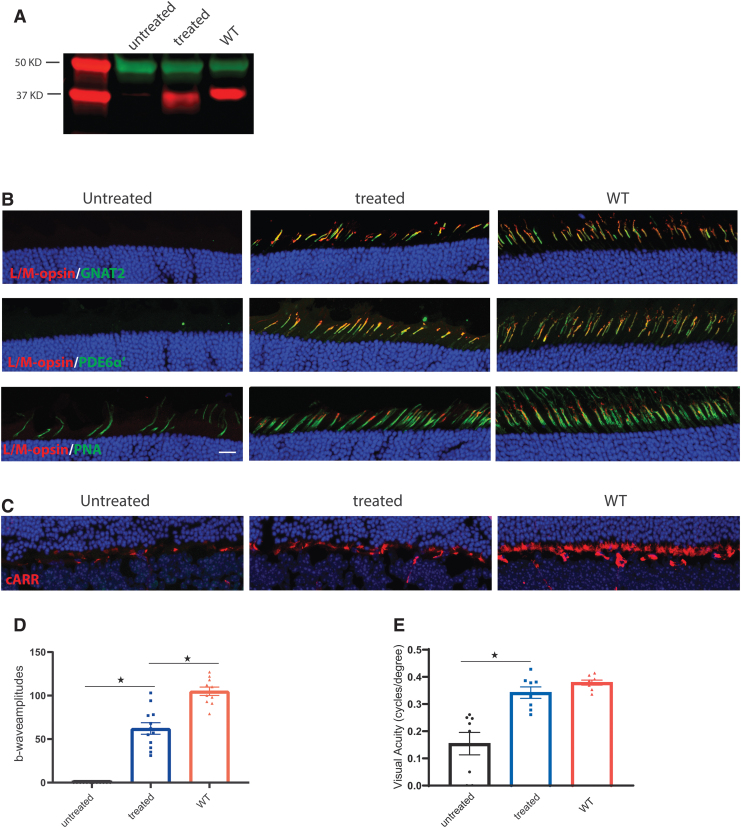

Visual function is maintained for at least 8 months post-treatment

We next assessed the long-term therapeutic effect of AAV in Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− mice treated before 2 months of age. Transgene expression, cone cellular structure, and visual function were analyzed 8 months after treatment. Western blot analysis showed that OPN1LW was still abundantly expressed at this age (Fig. 4A). Immunohistochemistry showed cone outer segment-specific expression of AAV-mediated OPN1LW and cone transducin alpha subunit (GNAT2) (Fig. 4B, top panel) and PDE6α′ (Fig. 4B, middle panel). In contrast to treated eyes, there were significantly fewer cones in contralateral untreated eyes by this age as indicated by PNA staining, suggesting that treatment at 2 months of age halted cone degeneration (Fig. 4B, bottom panel). Cone arrestin staining also showed that cone synapses degenerate with age, but treatment preserves cone synapses (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Cone-mediated function and visually guided behavior was maintained for at least 8 months post-treatment. All animals were injected at 2 months of age and analyzed 8 months postinjection. (A) Western blot analysis of OPN1LW expression (red) in Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− eyes. An anti-α-tubulin (green) antibody was used as loading control. (B) Immunohistochemistry analysis of subcellular localization of AAV-mediated OPN1LW from retinal cross-sections of Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− eyes stained with antibodies against OPN1LW (red) together with cone transducin α subunit GNAT2 (green, top row), PDE6α′ (green, middle row), or PNA (green, bottom row). Scale bar: 20 μm. (C) Immunohistochemistry analysis of cone synapses from retinal cross-sections of Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− eyes stained with antibody against cone arrestin (cARR, red). (D) Averaged long-wavelength-mediated ERG responses in Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− mice. The number of mice from each group are: untreated Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− eyes (n = 12), Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− eyes treated at 2 months and analyzed 8 months postinjection (n = 12) and WT controls (n = 10). Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of cone mediated b-wave amplitudes recorded at 630 nm at 1.4 log cd·s/m2. *p < 0.0001. (E) Optomotor analysis of visually guided behavior in Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− mice. Data show average values of spatial frequency thresholds in untreated Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− eyes (n = 8), Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− eyes treated at 2 months and analyzed 8 months postinjection (n = 8), WT controls (n = 8). Each bar represents the mean ± SEM, *p < 0.001.

ERG analysis (Fig. 4D) of Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− eyes 8 months postinjection demonstrated an averaged b-wave amplitude of 62 ± 7 (n = 12, average ± SEM), not significantly different from b-wave amplitude measured 1 month postinjection (63 ± 6 μV n = 10, average ± SEM), significantly higher than untreated eyes (n = 12, average ± SEM, p < 0.0001), yet significantly lower than wild-type mice (105 ± 5, n = 10, average ± SEM, p < 0.0001).

Optomotor analysis was performed to assess cone-mediated visual behavior at 8 months post-treatment (Fig. 4D). We observed that treated Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− eyes had significantly higher spatial frequency thresholds than untreated eyes under photopic conditions. Untreated eyes have a value of 0.1545 ± 0.0412 cycles per degree (n = 8, average ± SEM), while treated eyes had a value of 0.3421 ± 0.0211 cycles per degree, significantly better than untreated eyes (n = 8, average ± SEM, p < 0.001). The spatial frequency thresholds in treated eyes were not significantly different from wild-type controls (0.414 ± 0.009, n = 8, p > 0.05). The significant improvement of cone-mediated visually guided behavior in treated eyes is consistent with the photopic ERG results.

UbG76V-GFP is not accumulated in Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− cones

To investigate the possibility of extending cone survival and treatability, we study the molecular mechanism underlying cone death in our Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− mouse model. Previous studies found impaired clearance of ubiquitin proteasomal reporter (UbG76V-GFP mice) in mice lacking rod photoreceptor-specific opsin (rhodopsin).31 Similar to rhodopsin knockout mice, the double cone opsin knockout mice (Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/−) have problems with building of outer segments. Therefore, proteins, which normally reside in the cone outer segments, would need to be continuously degraded potentially leading to ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal stress and cone death.

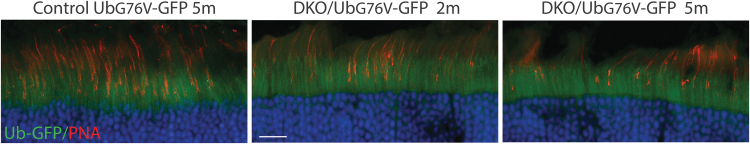

To test this hypothesis, we crossed Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− mice with mice expressing UbG76V-GFP reporter. GFP signal was assessed at several time points either directly with a 488 nm excitation wavelength on a confocal microscope or indirectly by immunohistochemistry with an anti-GFP antibody. However, no GFP signal above background levels was observed in cones examined with either method eliminating ubiquitin-proteasomal stress as a factor contributing to cone loss in Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− mice at least as assessed by this method (Fig. 5). Accumulation of UbG76V-GFP in RhodopsinP23H/WT mice was used as a positive control (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Figure 5.

Accumulation of UbG76V-GFP is not observed in Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− double knockout (DKO) cones. Representative images of UbG76V-GFP reporter fluorescence (green) in retinal cross-sections from control UbG76V-GFP mice (5-month-old), and DKO mice crossed with UbG76V-GFP mice at 2 and 5 months of age. Cones were labeled with PNA conjugated with rhodamine (red). Scale bar: 20 μm.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we generated and characterized an improved genetic mouse model for BCM—a Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− double knockout mouse, whose cones lack complete opsin expression from birth. Moreover, we demonstrate that Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− cones are capable of being rescued when injected at a young age (2 months) and the rescue lasts for at least 7 months after injection. Our results provide convincing evidence that cone outer segments lacking their key structural protein opsin can be regenerated to restore visual function.

AAV-mediated OPN1LW expression in Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− retina appears promising when mice are injected early. However, our data from animals injected later in life underline the importance of early intervention, which appears to be crucial for a better therapeutic outcome. Although some cones are still present in Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− retina when injected at 7 months of age, the majority of animals showed no significant improvement in cone function, with only 20% (3 out of 15) of these mice demonstrating any measurable functional rescue. This result is in stark contrast to our previous study, which shows that dorsal cone function and outer segment structure can still be rescued in aged Opn1mw−/− mice when treatment was initiated at 15 months of age.32 The hardiness of cones in Opn1mw−/− mice may be explained by the fact that most cones coexpress both M-opsin and S-opsin.13,14,33,34 Moreover, knocking out one type of cone opsin (either M- or S-opsin) leads to a higher expression level of the other.12,14 Therefore, it is likely that the residual expression of S-opsin in dorsal cones of Opn1mw−/− mice contributes to cone survival and treatability.

An important factor to consider when approaching BCM gene therapy is the fragile structure of the fovea cones in these patients. It is likely that an intravitreal injection of AAV vector with a higher penetrating property would be a better choice for BCM gene therapy, compared with an AAV administered by subretinal injection, which may cause more damage to the central retina due to injection-related retinal detachment. However, as the transgene expression levels in photoreceptors is still much lower when administered by intravitreal injection, even with higher penetrating AAVs, one important question remaining is what is the minimal level of cone opsin protein expression required for cones to generate light responses. Studies in S-opsin knockout mice provide evidence that stable, functional cone outer segments can form when opsin levels are 20% or lower of that relative to normal expression.14

Furthermore, knockin mice whose rhodopsin has been replaced by mouse M-opsin demonstrate that expression of M-opsin at a level of 11% that of rhodopsin supports formation of outer segments that are electrically light responsive.35 In a similar study, expression of S-opsin in Rho−/− rods at a level of ∼13% that of rhodopsin was shown to promote outer segment growth and cell survival, while also restoring their ability to respond to light.36

Another equally important question, which remains, is regarding the minimum number of cones required to maintain visual acuity. Prior studies have suggested that the relationship between visual acuity and foveal cone spacing are weakly correlated.37 Patients with retinal degeneration did not suffer significant reduction of visual acuity even after losing the majority (<90%) of cone photoreceptors.38 Recent studies using AOSLO to measure cone spacing near the fovea in eyes with retinal degeneration have demonstrated that roughly 50% of cones can degenerate before visual acuity declines below 20/25.39,40 These results suggest that large numbers of functional cones are not an absolute requisite for detection and discrimination.

To continue to develop and enhance effectiveness of BCM gene therapy, with the primary goal of extending cone survival and treatability, an important and logical next step in this project would be to study the molecular mechanism underlying cone death in our Opn1mw−/−/Opn1sw−/− mouse model. Interestingly, we found that in contrast to Rho−/− rods lacking their major opsin, cones of mice lacking both opsins do not accumulate ubiquitin proteasomal UbG76V-GFP reporter. This finding indicates differences in pathological stress responses between cones and rods.

A previous study has shown that the cell death mechanisms of rods and cones are intrinsically distinct with cones undergoing necrotic changes, including massive destruction of their intracellular contents and late caspase 7 activation, while rods undergo apoptosis, caspase 3 and Parp1 activation.41–43 In animal models where cones die first, cones have high levels of receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 (RIP1) and receptor-interacting protein kinase 3 (RIP3) kinases, key regulators of necroptotic cell death. Moreover, cone cell death can be substantially suppressed by RIP3 deficiency or the RIP kinase inhibitor.44 Our finding calls for further studies of mechanisms causing cone death in double opsin knockout mice.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, our current study provides proof of concept that AAV-mediated gene augmentation therapy can promote regeneration of cone outer segments and rescue cone-mediated function and visually guided behavior in a mouse model carrying a congenital cone opsin deletion. Our results also highlight the importance of early intervention for BCM patients carrying deletion mutations.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Edward N. Pugh (Eyepod Imaging Laboratory, Department of Cell Biology and Human Anatomy, University of California Davis) for providing Opn1sw−/− mice. They thank Ling Yin for counting PNA-positive cells from retinal wholemounts.

AUTHOR DISCLOSURE

No competing financial interests exist.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 EY030056 to Wen-Tao Deng, R01 EY08123 to Wolfgang Baehr, R01 EY024280 to Shannon E. Boye, and R01 EY030043 to Ekaterina Lobanova), West Virginia University startup fund to Deng, National Eye Institute (EY014800-039003, core grant to the Department of Ophthalmology, University of Utah), unrestricted grants to the Departments of Ophthalmology at the University of Florida and the University of Utah from Research to Prevent Blindness (RPB; New York), and SIG grant National Institutes of Health (1S10OD028476 to Department of Ophthalmology, University of Florida).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

REFERENCES

- 1. Buena-Atienza E, Ruther K, Baumann B, et al. De novo intrachromosomal gene conversion from OPN1MW to OPN1LW in the male germline results in Blue Cone Monochromacy. Sci Rep 2016;6:28253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gardner JC, Michaelides M, Holder GE, et al. Blue cone monochromacy: causative mutations and associated phenotypes. Mol Vis 2009;15:876–884. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kazmi MA, Sakmar TP, Ostrer H. Mutation of a conserved cysteine in the X-linked cone opsins causes color vision deficiencies by disrupting protein folding and stability. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1997;38:1074–1081. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nathans J, Davenport CM, Maumenee IH, et al. Molecular genetics of human blue cone monochromacy. Science 1989;245:831–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Smallwood PM, Wang Y, Nathans J. Role of a locus control region in the mutually exclusive expression of human red and green cone pigment genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002;99:1008–1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Michaelides M, Johnson S, Simunovic MP, et al. Blue cone monochromatism: a phenotype and genotype assessment with evidence of progressive loss of cone function in older individuals. Eye (Lond) 2005;19:2–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Michaelides M, Hunt DM, Moore AT. The cone dysfunction syndromes. Br J Ophthalmol 2004;88:291–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Carroll J, Dubra A, Gardner JC, et al. The effect of cone opsin mutations on retinal structure and the integrity of the photoreceptor mosaic. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2012;53:8006–8015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cideciyan AV, Hufnagel RB, Carroll J, et al. Human cone visual pigment deletions spare sufficient photoreceptors to warrant gene therapy. Hum Gene Ther 2013;24:993–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Carroll J, Rossi EA, Porter J, et al. Deletion of the X-linked opsin gene array locus control region (LCR) results in disruption of the cone mosaic. Vision Res 2010;50:1989–1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Deng WT, Li J, Zhu P, et al. Human L- and M-opsins restore M-cone function in a mouse model for human blue cone monochromacy. Mol Vis 2018;24:17–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhang Y, Deng WT, Du W, et al. Gene-based therapy in a mouse model of Blue Cone Monochromacy. Sci Rep 2017;7:6690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Applebury ML, Antoch MP, Baxter LC, et al. The murine cone photoreceptor: a single cone type expresses both S and M opsins with retinal spatial patterning. Neuron 2000;27:513–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Daniele LL, Insinna C, Chance R, et al. A mouse M-opsin monochromat: retinal cone photoreceptors have increased M-opsin expression when S-opsin is knocked out. Vision Res 2011;51:447–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Curcio CA, Allen KA, Sloan KR, et al. Distribution and morphology of human cone photoreceptors stained with anti-blue opsin. J Comp Neurol 1991;312:610–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Curcio CA, Sloan KR, Kalina RE, et al. Human photoreceptor topography. J Comp Neurol 1990;292:497–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hofer H, Carroll J, Neitz J, et al. Organization of the human trichromatic cone mosaic. J Neurosci 2005;25:9669–9679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mustafi D, Engel AH, Palczewski K. Structure of cone photoreceptors. Prog Retin Eye Res 2009;28:289–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lindsten K, Menendez-Benito V, Masucci MG, et al. A transgenic mouse model of the ubiquitin/proteasome system. Nat Biotechnol 2003;21:897–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mancuso K, Hauswirth WW, Li Q, et al. Gene therapy for red-green colour blindness in adult primates. Nature 2009;461:784–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zolotukhin S, Potter M, Zolotukhin I, et al. Production and purification of serotype 1, 2, and 5 recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors. Methods 2002;28:158–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pang JJ, Boye SL, Kumar A, et al. AAV-mediated gene therapy for retinal degeneration in the rd10 mouse containing a recessive PDEbeta mutation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2008;49:4278–4283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pang JJ, Chang B, Kumar A, et al. Gene therapy restores vision-dependent behavior as well as retinal structure and function in a mouse model of RPE65 Leber congenital amaurosis. Mol Ther 2006;13:565–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Alexander JJ, Umino Y, Everhart D, et al. Restoration of cone vision in a mouse model of achromatopsia. Nat Med 2007;13:685–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Umino Y, Solessio E, Barlow RB. Speed, spatial, and temporal tuning of rod and cone vision in mouse. J Neurosci 2008;28:189–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Douglas RM, Alam NM, Silver BD, et al. Independent visual threshold measurements in the two eyes of freely moving rats and mice using a virtual-reality optokinetic system. Vis Neurosci 2005;22:677–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Blanks JC, Johnson LV. Selective lectin binding of the developing mouse retina. J Comp Neurol 1983;221:31–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jeon CJ, Strettoi E, Masland RH. The major cell populations of the mouse retina. J Neurosci 1998;18:8936–8946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Williams GA, Jacobs GH. Cone-based vision in the aging mouse. Vision Res 2007;47:2037–2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li Q, Timmers AM, Guy J, et al. Cone-specific expression using a human red opsin promoter in recombinant AAV. Vision Res 2008;48:332–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lobanova ES, Finkelstein S, Skiba NP, et al. Proteasome overload is a common stress factor in multiple forms of inherited retinal degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013;110:9986–9991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Deng WT, Li J, Zhu P, et al. Rescue of M-cone function in aged Opn1mw-/- mice, a model for late-stage Blue Cone Monochromacy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2019;60:3644–3651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lyubarsky AL, Falsini B, Pennesi ME, et al. UV- and midwave-sensitive cone-driven retinal responses of the mouse: a possible phenotype for coexpression of cone photopigments. J Neurosci 1999;19:442–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nikonov SS, Kholodenko R, Lem J, et al. Physiological features of the S- and M-cone photoreceptors of wild-type mice from single-cell recordings. J Gen Physiol 2006;127:359–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sakurai K, Onishi A, Imai H, et al. Physiological properties of rod photoreceptor cells in green-sensitive cone pigment knock-in mice. J Gen Physiol 2007;130:21–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shi G, Yau KW, Chen J, et al. Signaling properties of a short-wave cone visual pigment and its role in phototransduction. J Neurosci 2007;27:10084–10093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Geller AM, Sieving PA, Green DG. Effect on grating identification of sampling with degenerate arrays. J Opt Soc Am A 1992;9:472–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Geller AM, Sieving PA. Assessment of foveal cone photoreceptors in Stargardt's macular dystrophy using a small dot detection task. Vision Res 1993;33:1509–1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Foote KG, Loumou P, Griffin S, et al. Relationship between foveal cone structure and visual acuity measured with adaptive optics scanning laser ophthalmoscopy in retinal degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2018;59:3385–3393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ratnam K, Carroll J, Porco TC, et al. Relationship between foveal cone structure and clinical measures of visual function in patients with inherited retinal degenerations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2013;54:5836–5847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chang GQ, Hao Y, Wong F. Apoptosis: final common pathway of photoreceptor death in rd, rds, and rhodopsin mutant mice. Neuron 1993;11:595–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cho KI, Haque M, Wang J, et al. Distinct and atypical intrinsic and extrinsic cell death pathways between photoreceptor cell types upon specific ablation of Ranbp2 in cone photoreceptors. PLoS Genet 2013;9:e1003555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Murakami Y, Ikeda Y, Nakatake S, et al. Necrotic cone photoreceptor cell death in retinitis pigmentosa. Cell Death Dis 2015;6:e2038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Viringipurampeer IA, Shan X, Gregory-Evans K, et al. Rip3 knockdown rescues photoreceptor cell death in blind pde6c zebrafish. Cell Death Differ 2014;21:665–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.