Abstract

Background

The Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccine may confer cross‐protection against viral diseases in adults. This study evaluated BCG vaccine cross‐protection in adults with convalescent coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19).

Method

This was a multicenter, prospective, randomized, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind phase III study (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04369794). Setting: University Community Health Center and Municipal Outpatient Center in South America. Patients: a total of 378 adult patients with convalescent COVID‐19 were included. Intervention: single intradermal BCG vaccine (n = 183) and placebo (n = 195). Measurements: the primary outcome was clinical evolution. Other outcomes included adverse events and humoral immune responses for up to 6 months.

Results

A significantly higher proportion of BCG patients with anosmia and ageusia recovered at the 6‐week follow‐up visit than placebo (anosmia: 83.1% vs. 68.7% healed, p = 0.043, number needed to treat [NNT] = 6.9; ageusia: 81.2% vs. 63.4% healed, p = 0.032, NNT = 5.6). BCG also prevented the appearance of ageusia in the following weeks: seven in 113 (6.2%) BCG recipients versus 19 in 126 (15.1%) placebos, p = 0.036, NNT = 11.2. BCG did not induce any severe or systemic adverse effects. The most common and expected adverse effects were local vaccine lesions, erythema (n = 152; 86.4%), and papules (n = 111; 63.1%). Anti–severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 humoral response measured by N protein immunoglobulin G titer and seroneutralization by interacting with the angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 receptor suggest that the serum of BCG‐injected patients may neutralize the virus at lower specificity; however, the results were not statistically significant.

Conclusion

BCG vaccine is safe and offers cross‐protection against COVID‐19 with potential humoral response modulation. Limitations: No severely ill patients were included.

Keywords: BCG, convalescence, COVID‐19, IgG, immunomodulation, neutralization, safety, SARS‐CoV‐2

Introduction

The Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccine was developed over 100 years ago to prevent severe forms of tuberculosis in children [1]. Half a century later, the effect of BCG on modulating immunity was successfully used to treat non‐muscle invasive bladder cancer [2]. As part of the Brazilian vaccination schedule, this vaccine is offered at birth [3], after which a small local lesion evolves into a vaccine scar in most cases. However, more severe local and systemic adverse events may occur [4].

Regardless of the skin test result, BCG revaccination is not recommended because of the lack of evidence on its safety but has recently attracted interest due to its off‐target effects in adults [5]. In addition, this vaccine was considered an option at the beginning of the pandemic caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) until the emergence of a specific vaccine [6].

In this trial, we first hypothesized that BCG revaccination in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) convalescent adults is safe: the healing of COVID‐19 symptoms is not prolonged, and new symptoms do not emerge. Further, we hypothesized that BCG could serve as an adjuvant to minimize damage from an already installed process, improve immune response, and enhance the efficacy of SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccination. Herein, we describe a phase III placebo‐controlled clinical trial of 378 adults with convalescent COVID‐19 randomized 1:1 to receive BCG and placebo.

Materials and methods

BATTLE clinical trial design

This study is a multicenter, prospective, randomized (1:1, www.randomization.com), double‐blind, parallel‐group, placebo‐controlled phase III clinical trial, approved by National Commission for Research Ethics (CONEP) under number 31049320.7.1001.5404. All participants signed an informed consent form authorizing the use of their data before participating in the study. This trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT04369794 (COVID‐19 BATTLE trial), and is funded by CAPES. The funders had no role in the design, conduct, analysis, or interpretation of data.

Residents of the metropolitan region of Campinas (state of São Paulo, Brazil) were invited by phone to participate in the study between October 2020 and December 2021. Eligibility criteria were individuals older than 18 years of both sexes diagnosed with COVID‐19 in the last 14 days by nasopharyngeal reverse transcription–quantitative polymerase chain reaction performed in outpatient settings of the Community Health Center (CeCom) of the State University of Campinas, UNICAMP (Campinas‐SP, Brazil), and Paulínia Municipal Hospital, HMP (Paulínia‐SP, Brazil).

Exclusion criteria included contraindications to BCG administration (pregnant; immunosuppressed, including use of corticosteroids for a period longer than 3 months; transplanted; cancer; use of immunobiological or chemotherapy), or who did not understand or agree to provide informed consent.

The established COVID‐19 BATTLE trial protocol determined T0 as the day of randomization and injection application and T1, T2, T3, and T4 as 7, 14, 21, and >40 days after application, respectively. At T0, the patients were screened, and those eligible signed the informed consent and completed the established clinical questionnaire (based on Brazilian Ministry of Health 2014 guidelines, BRASIL, 2014) stored in the database software REDCap (v5.18.1‐Vanderbilt University, USA), followed by the application of BCG or placebo.

The patients’ questionnaire included the history of current disease, symptoms, and comorbidities as follows: hypertension (systolic blood pressure >139 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure >89 mmHg), obesity (body mass index >30 kg/m2), chronic pulmonary diseases (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic asthma, interstitial lung diseases, etc.), chronic sinusitis (chronic sinus inflammation >6 months), respiratory allergies, hemoglobinopathies, and autoimmune diseases. Other chronic diseases were classified under “other” and included the following: hypothyroidism, gastritis, depression, arthrosis, dyslipidemia, glaucoma, and so on.

Administration of BCG vaccine or placebo

Either 0.1 ml of BCG vaccine, Brazilian strain (Ataulpho de Paiva Foundation, FAP, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) or Russian BCG‐I strain (Serum Institute of India PVT LTD, Hadapsar, Pune, India), or 0.1 ml of 0.9% saline solution was intradermic injected into the deltoid area on the arm without a BCG scar for better monitoring of the emerging skin reactions.

Allocation and concealment: one investigator prepared the injections and numbered them based on a predetermined list of randomized numbers. The syringes for placebo and BCG were identical, and the investigator who injected them and the patient were both blinded to the content.

Symptoms monitoring

Patients were monitored, and symptoms were characterized at day zero (randomization), 7, 14, 21, and >40 days. Symptom recovery and the emergence of new symptoms were analyzed.

Evaluation of the vaccine dermic reaction and characterization of adverse events

The standardized measurement of the dermal vaccine reaction was performed at T1, T2, T3, and T4 in millimeters using a ruler or measuring tape and recorded in a photo at a distance of 15–20 cm from the wound.

Adverse reactions to vaccination were classified according to the World Health Organization and Epidemiological Surveillance Manual of Post‐Vaccination Adverse Events [7].

Detection of immunoglobulin G anti‐SARS‐COV‐2 N protein

For immunoglobulin G (IgG) anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 N protein and neutralizing antibody detection, venous blood was collected from four BD Vacutainer spray‐coated K2EDTA tubes (12 ml) before the intervention (T0) and during the follow‐up visits (T1, T2, T3, and T4). The tubes were centrifuged, and the plasma was separated.

Detection of IgG in plasma samples was verified in 38 consecutive patients (n = 15 in the placebo group and n = 23 in the BCG group) by ELISA to detect IgG anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 N protein.

After overnight incubation at 4°C in a 96‐well microplate containing SARS‐CoV‐2 N protein (1 ug/ml) and washing with phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) 0.1% + Tween 20, the plate was blocked against nonspecific binding with PBS + 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA solution for 1 h at 37°C). After washing again, the plasma samples were diluted at 1:100 and added to the plate (100 μL/well). After incubation for 2 h at 37°C, the secondary antibody, anti‐human IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (1:30,000), was added for 1 h at 37°C. For the detection of antiviral IgG, tetramethylbenzidine (Thermo Scientific) was added, and after 3 min, the reaction was stopped with a solution of HCl (1N). The absorbance of the reaction was measured using a microplate reader at 450 nm. The assay was validated using positive (diagnosed patients) and negative (samples obtained from uninfected individuals before the pandemic) controls.

Detection of neutralizing antibodies

Plasma samples from the placebo group (n = 12) and BCG group (n = 11) were used to detect IgG at T0 and T4 to verify whether vaccination with BCG induces the production of neutralizing anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 antibodies in the long term. Neutralizing antibodies were detected using the SARS‐CoV‐2 Neutralization Antibody ELISA kit (Elabscience Biotechnology Inc., United States) precoated with recombinant human angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analysis

Study sample size: the primary outcome of our study was the evaluation of symptom resolution in patients infected with SARS‐CoV‐2. To provide 80% power to detect a symptom difference of 13% between the groups using a type‐I error of 0.05, 180 patients were required per group.

The Wilcoxon rank‐sum test (unpaired) was used to analyze continuous variables. Fisher's exact test was used for categorical analysis. A p‐value of less than 0.05 was considered significant, and each test's significance was discussed based on context. Error bars in all figures represent one standard deviation unless otherwise specified. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.1.2 (1 November 2021) on the RStudio platform version “Ghost Orchid” Release (fc9e2179, 2022‐01‐04) and using the following packages: tidyverse, ggstatsplot, and janitor.

Results

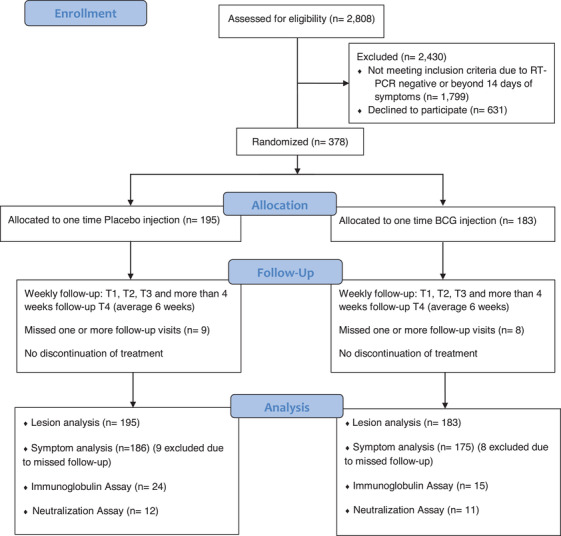

A total of 2808 patients were approached by phone, of which 381 fulfilled the inclusion criteria and agreed to participate. Three patients were excluded due to comorbidities (immunocompromised state), leaving 378 for randomization (Fig. 1). The patients were randomized 13 days after symptom onset. The BCG vaccine was administered to 183 patients, and 195 patients received a placebo.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of study inclusion, exclusion, and analysis.

Table 1 shows the characteristics and comorbidities of both groups. There were no significant differences in the symptoms at admission (T0). Most patients in both groups had BCG scars from childhood vaccination (94.5% of BCG and 93.3% of placebo, p = 0.67). In terms of comorbidities, there was a higher proportion of chronic pulmonary diseases (asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, etc.) than in the placebo group (6.6% vs. 2.1%, p = 0.039). There were no other significant differences in the comorbidities.

Table 1.

Characteristics and comorbidities of participants vaccinated with BCG or placebo

| Demographics and comorbidities | BCG (n = 183) | Placebo (n = 195) | p‐Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 39.8 ± 14.0 | 41.6 ± 12.3 | 0.12 |

| BMI (mean ± SD) | 28.3 ± 15.3 | 28.2 ± 13.8 | 0.91 |

| Female gender, no. (%) | 105 (57.4) | 123 (63.1) | 0.29 |

| Presence of old BCG scar, no. (%) | 173 (94.5) | 182 (93.3) | 0.67 |

| Physically active, no. (%) | 100 (54.6) | 98 (50.3) | 0.41 |

| Tobacco smoking, no. (%) | 15 (8.2) | 15 (7.7) | 1 |

| Regular alcohol drinking, no. (%) | 80 (43.7) | 93 (47.7) | 0.47 |

| Diabetes, no. (%) | 10 (5.5) | 12 (6.2) | 0.82 |

| Hypertension, no. (%) | 32 (17.5) | 34 (17.4) | 1 |

| Obesity, no. (%) | 15 (8.2) | 15 (7.7) | 1 |

| Chronic heart disease, no. (%) | 4 (2.2) | 1 (0.5) | 0.202 |

| Chronic kidney disease, no. (%) | 0 | 0 | ‐ |

| Chronic pulmonary disease, no. (%) | 12 (6.6) | 4 (2.1) | 0.039 |

| Chronic sinusitis, no. (%) | 27 (14.8) | 26 (13.3) | 0.76 |

| Respiratory allergies, no. (%) | 24 (13.1) | 23 (11.8) | 0.75 |

| Hemoglobinopathies, no. (%) | 1 | 0 | ‐ |

| Autoimmune disease, no. (%) | 0 | 0 | ‐ |

| Others, no. (%) | 55 (30.1) | 64 (32.8) | 0.58 |

| Symptomatology | |||

| Days symptomatic on admission (mean ± SD) | 12.8 ± 15.3 | 13.2 ± 12.3 | 0.27 |

| Cough, no. (%) | 65 (35.5) | 54 (27.7) | 0.12 |

| Fever, no. (%) | 3 (1.6) | 1 (0.5) | 0.35 |

| Fatigue, no. (%) | 56 (30.6) | 66 (33.8) | 0.51 |

| Coryza, no. (%) | 18 (9.8) | 13 (6.7) | 0.35 |

| Nasal congestion, no. (%) | 29 (15.8) | 29 (14.9) | 0.88 |

| Myalgia, no. (%) | 27 (14.8) | 34 (17.4) | 0.49 |

| Arthralgia, no. (%) | 16 (8.7) | 22 (6.2) | 0.43 |

| Headache, no. (%) | 41 (22.4) | 41 (21.0) | 0.80 |

| Sore throat, no. (%) | 21 (11.5) | 26 (13.3) | 0.64 |

| Anosmia, no. (%) | 83 (45.5) | 87 (44.6) | 0.92 |

| Ageusia, no. (%) | 70 (38.3) | 69 (35.4) | 0.59 |

| Nausea, no. (%) | 15 (8.2) | 16 (8.2) | 1 |

| Vomiting, no. (%) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | ‐ |

| Diarrhea, no. (%) | 14 (7.7) | 10 (5.1) | 0.40 |

| Dyspnea, no. (%) | 24 (13.1) | 17 (8.7) | 0.19 |

| Asymptomatic, no. (%) | 38 (20.8) | 38 (19.5) | 0.80 |

Note: Wilcoxon rank‐sum test with continuity correction.

Abbreviations: BCG, Bacillus Calmette‐Guérin; BMI, body mass index; no., number; SD, standard deviation.

Follow‐up and major events

Two patients from the BCG group and one from the placebo group were hospitalized in the first week following randomization, and one patient (BCG) died of COVID‐19 complications. Two patients (both placebo) were hospitalized at week three. No other major adverse events were observed. No tuberculosis or disseminated BCGitis was reported.

Adverse reactions

The BCG group demonstrated no systemic adverse effect. Table S1 shows details of local skin reactions following injection.

At the first visit (T1, 1 week after injection), the vast majority of patients in the BCG group presented with local erythema (n = 152, 86.4%) and some presented with papules (n = 111, 63.1%) or pustules (n = 16, 9.1%). Other reactions, such as mild pain at the injection site (n = 12, 6.8%) and local itching (n = 24, 13.6%), have also been reported. Late skin reactions (ulcers, crust, and scars) became common during the later visits.

There were very few skin reactions in the placebo group: two local erythema, one papule, and one pustule.

Symptom analysis

In the symptom analysis, we endeavored to answer two questions.

First, does BCG cause the development of new symptoms in patients infected with SARS‐CoV‐2? Second, does BCG impact the recovery time of already developed symptoms? For both questions, we excluded patients who did not fulfill all their follow‐up visits; eight (4.3%) from the BCG group and nine (4.6%) from the placebo group were excluded.

Acquiring new symptoms after injection

To answer the first question, we assessed the development of new COVID‐related symptoms in patients who did not have these symptoms at the time of injection. We counted new cases of each symptom weekly until the last follow‐up (>4 weeks; average, 6 weeks).

Table 2 shows the development of new symptoms in patients who did not show any symptoms on admission. Patients who did not have ageusia at the time of injection were significantly less likely to develop ageusia in the following weeks (seven new cases in 113 BCG recipients compared to 19 in 126 placebos, p = 0.036, number needed to treat [NNT] = 11.2). A similar pattern was observed in the development of new anosmia cases, but the difference was not statistically significant (10 new cases in 100 BCGs compared to 19 in 108 placebos, p = 0.16). In addition, there were no statistically significant differences in the development of other new symptoms between BCG and placebo.

Table 2.

Development of new symptoms

| Admission (n = patients without the symptom) | First‐week new cases | Second‐week new cases | Third‐week new cases | >4 weeks new cases | Total new cases, n (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cough | ||||||

| Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG; n = 118) | BCG = 12 | BCG = 7 | BCG = 3 | BCG = 3 | BCG = 25 (21.2) | 0.92 |

| Placebo (n = 141) | Placebo = 10 | Placebo = 4 | Placebo = 2 | Placebo = 2 | Placebo = 18 (12.8) | |

| Fatigue | ||||||

| BCG (n = 127) | BCG = 14 | BCG = 3 | BCG = 3 | BCG = 6 | BCG = 26 (20.5) | 0.42 |

| Placebo (n = 129) | Placebo = 9 | Placebo = 3 | Placebo = 2 | Placebo = 7 | Placebo = 21 (16.3) | |

| Fever | ||||||

| BCG (n = 173) | BCG = 0 | BCG = 0 | BCG = 0 | BCG = 0 | BCG = 0 | ‐ |

| Placebo (n = 188) | Placebo = 2 | Placebo = 0 | Placebo = 0 | Placebo = 0 | Placebo = 2 (1.1) | |

| Coryza | ||||||

| BCG (n = 165) | BCG = 3 | BCG = 2 | BCG = 4 | BCG = 1 | BCG = 10 (6.1) | 1 |

| Placebo (n = 182) | Placebo = 6 | Placebo = 2 | Placebo = 1 | Placebo = 2 | Placebo = 11 (6.0) | |

| Nasal congestion | ||||||

| BCG (n = 154) | BCG = 4 | BCG = 4 | BCG = 1 | BCG = 1 | BCG = 10 (6.5) | 0.46 |

| Placebo (n = 166) | Placebo = 4 | Placebo = 2 | Placebo = 0 | Placebo = 1 | Placebo = 7 (4.2) | |

| Myalgia | ||||||

| BCG (n = 156) | BCG = 8 | BCG = 2 | BCG = 3 | BCG = 3 | BCG = 16 (10.3) | 1 |

| Placebo (n = 161) | Placebo = 9 | Placebo = 4 | Placebo = 3 | Placebo = 1 | Placebo = 17 (10.6) | |

| Arthralgia | ||||||

| BCG (n = 167) | BCG = 0 | BCG = 2 | BCG = 1 | BCG = 1 | BCG = 4 (2.4) | 0.11 |

| Placebo (n = 173) | Placebo = 6 | Placebo = 2 | Placebo = 0 | Placebo = 3 | Placebo = 11 (6.4) | |

| Headache | ||||||

| BCG (n = 142) | BCG = 12 | BCG = 5 | BCG = 3 | BCG = 7 | BCG = 27 | 0.76 |

| Placebo (n = 154) | Placebo = 14 | Placebo = 5 | Placebo = 4 | Placebo = 4 | Placebo = 27 | |

| Sore throat | ||||||

| BCG (n = 162) | BCG = 5 | BCG = 1 | BCG = 0 | BCG = 0 | BCG = 6 (3.7) | 0.78 |

| Placebo (n = 169) | Placebo = 5 | Placebo = 0 | Placebo = 2 | Placebo = 1 | Placebo = 8 (4.7) | |

| Anosmia | ||||||

| BCG (n = 100) | BCG = 4 | BCG = 3 | BCG = 1 | BCG = 2 | BCG = 10 (10.0) | 0.16 |

| Placebo (n = 108) | Placebo = 14 | Placebo = 2 | Placebo = 0 | Placebo = 3 | Placebo = 19 (17.6) | |

| Ageusia | ||||||

| BCG (n = 113) | BCG = 4 | BCG = 0 | BCG = 2 | BCG = 1 | BCG = 7 (6.2) | 0.036 |

| Placebo (n = 126) | Placebo = 12 | Placebo = 4 | Placebo = 2 | Placebo = 1 | Placebo = 19 (15.1) | |

| Diarrhea | ||||||

| BCG (n = 169) | BCG = 1 | BCG = 1 | BCG = 2 | BCG = 2 | BCG = 6 (3.6) | 0.76 |

| Placebo (n = 185) | Placebo = 5 | Placebo = 0 | Placebo = 0 | Placebo = 0 | Placebo = 5 (2.7) | |

| Nausea | ||||||

| BCG (n = 168) | BCG = 2 | BCG = 1 | BCG = 0 | BCG = 1 | BCG = 4 (2.4) | 0.20 |

| Placebo (n = 179) | Placebo = 1 | Placebo = 0 | Placebo = 0 | Placebo = 0 | Placebo = 1 (0.6) | |

| Vomiting | ||||||

| BCG (n = 182) | BCG = 0 | BCG = 1 | BCG = 0 | BCG = 0 | BCG = 1 (0.5) | ‐ |

| Placebo (n = 194) | Placebo = 0 | Placebo = 0 | Placebo = 0 | Placebo = 0 | Placebo = 0 | |

| Dyspnea | ||||||

| BCG (n = 159) | BCG = 3 | BCG = 2 | BCG = 1 | BCG = 3 | BCG = 9 (5.7) | 0.81 |

| Placebo (n = 178) | Placebo = 6 | Placebo = 3 | Placebo = 0 | Placebo = 0 | Placebo = 9 (5.1) | |

Recovery from COVID‐19 symptoms after injection

To answer the second question, we analyzed patients based on their symptoms at the time of injection and compared the symptom recovery process. This calculation showed a relapsing nature, particularly in the third week. In patients who complained of fatigue on admission, we saw a relapse in fatigue during the second week in the BCG group. However, in the placebo group, relapse was observed at the last visit (>4 weeks). In both groups, there were a few cases of diarrhea relapse during the second week and sore throat relapse during the third week. Both groups had an increase in headaches, arthralgia, myalgia, nausea, and nasal congestion in the third week (Table S2).

We statistically analyzed the percentage of recovered symptoms in each group during the third week. There was no statistically significant difference in the percentage of healed cases between the two groups for any symptoms during the third week. We also compared the percentage of healed patients at the final visit for anosmia and ageusia because these two symptoms tend to heal slowly. A significantly higher number of BCG patients with anosmia and ageusia healed at the 6‐week follow‐up visit compared to placebo (anosmia: 83.1% vs. 68.7% healed, p = 0.043, NNT = 6.9; ageusia: 81.2% vs. 63.4% healed, p = 0.032, NNT = 5.6).

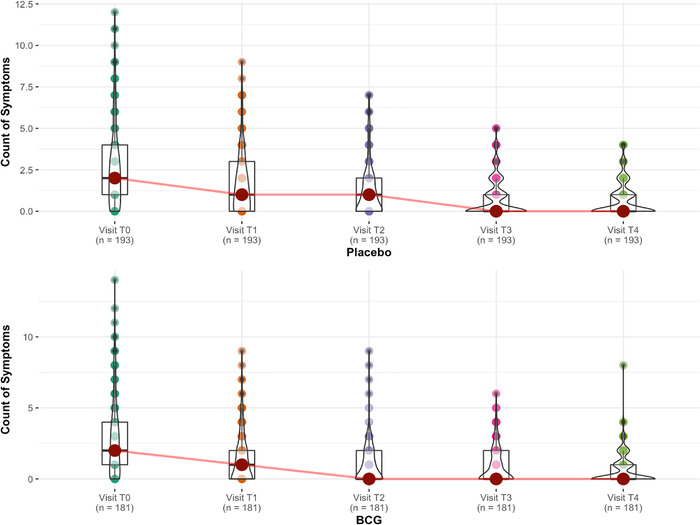

We also calculated the changes in the number of symptoms per week (Fig. 2). The counting of symptoms shows that placebo and BCG overlap almost perfectly in terms of recovery from symptoms except on the second follow‐up visit (T2, 14 days of randomization), where there was a slightly lower symptom count in the BCG group.

Fig. 2.

Symptomatic analysis of patients. Each symptom is given a number, and the count of symptoms for each patient for each visit is calculated to understand the difference in speed of recovery. For example, if the patient had headache and fatigue on visit T1, the symptom count on T1 would be 2. The graphs show no significant difference between Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) and placebo on recovery speed except for visit T2 when BCG recipients are slightly less symptomatic.

Potentially non‐COVID‐related symptoms

There were few non‐COVID‐19 symptoms.

In the first‐week visit (T1), four patients complained of mild dizziness (placebo), three of intense sweating (placebo), one of stomach pain (placebo), two of back pain (one BCG and one placebo), and one of palpitation (BCG).

At the second‐week visit (T2), two patients complained of abdominal pain (one BCG or placebo), one of general urticaria (placebo), three of back pain (one placebo and two BCG), one of photosensitivity (placebo), and three of dizziness (two placeboes and one BCG).

Third‐week visit (T3): two patients complained of dizziness (both placebo), one of loss of appetite (placebo), and four of back pain (two placeboes, two BCG).

Beyond 40 days visit (T4): two patients complained of dizziness (both placebo), two of back pains (both BCG), heartburn (BCG), two of pleuritic chest pains (both placebo), one of dysuria (placebo), and one of constipation (placebo).

IgG quantification and neutralization assay

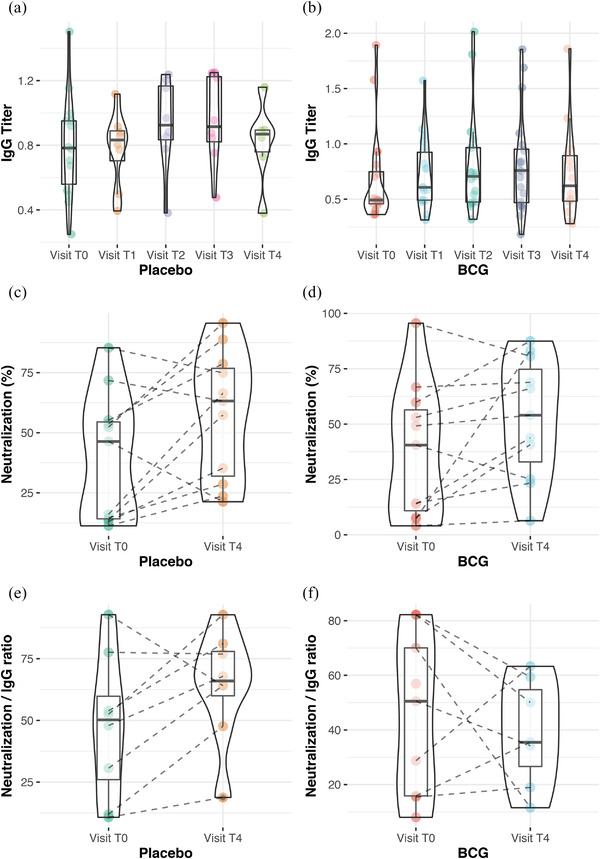

We initially performed an ELISA assay to evaluate antiviral IgG antibodies against SARS‐CoV‐2 N protein in plasma samples from 24 BCG (vaccinated approximately 12 days following symptom onset) and 15 placebo recipients that were collected during follow‐up visits on days 0, 7, 14, 21, and >40 days. Table S3 shows the characteristics and comorbidities and Table S4 shows the symptom evolution of each group.

There was a borderline difference between the two groups regarding IgG titers on day 21 (Wilcoxon rank‐sum test, p = 0.078, Fig. 3a,b). IgG fold induction was calculated as the IgG titer on the follow‐up visit divided by the IgG titer on admission. There was a borderline difference in IgG fold induction between the BCG and placebo groups (all follow‐ups compared together: Wilcoxon rank‐sum exact test, p = 0.057). Daily comparison of the two groups, however, showed no significant difference.

Fig. 3.

Serology analysis of patients. (a) and (b) show anti–severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 N protein immunoglobulin G (IgG) titer on each visit. There was no significant difference on this titer between Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) and placebo. (c) and (d) show percent neutralization of recombinant ACE2 receptor assay of patient sera. (e) and (f) are neutralization divided by IgG titer, showing a slightly lower result at T4 in BCG recipients.

There was no significant difference between the two groups in antiviral IgG levels or neutralization, which was also evaluated in these plasma samples on admission and beyond 40 days (T4) (Fig. 3c,d). However, when neutralization was normalized by IgG titer (neutralization divided by IgG titer), there was a slight difference between the two groups in T4 (Wilcoxon rank‐sum exact test, p = 0.189 and p = 0.053 after removing an outlier sample, Fig. 3e,f).

Discussion

The emergence of COVID‐19 has forced the scientific community to develop new treatments and repurpose old treatments. Previous studies have shown that BCG protects infants and children against mortality from respiratory viral infections. BCG has also been shown to modulate the immune response against viruses in multiple studies [8, 9, 10, 11, 12]. Furthermore, since the beginning of our trial, a few retrospective studies have shown the possible protection against SARS‐CoV‐2 of old or new BCG vaccination in adults [13].

A retrospective observational study of a diverse cohort of 6679 healthcare workers in Los Angeles, California, demonstrated that a history of BCG vaccination was associated with reduced COVID‐19 related clinical symptoms (p = 0.017) as well as decreased seroprevalence of anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 IgG with an odds ratio of 0.76 (95% confidence interval: 0.57–0.99; p = 0.048). In addition, a BCG vaccination history has also been associated with decreased SARS‐CoV‐2 seroprevalence across a diverse cohort of healthcare workers [14].

Using the results of this study in decision making

In the case of making decisions for an individual adult regarding BCG revaccination, our data with an adequate sample size shows that BCG is possibly safe—BCG is unlikely to cause severe adverse effects in an adult with convalescent COVID‐19 with mild symptoms. However, our data are not representative of severely ill patients or children with COVID‐19. Our data are also insufficient to make large‐scale decisions for an entire population; a sample size of 378 is adequate for individual decision making. However, rare adverse effects only emerge in large sample sizes, although BCG has been successfully used for the last 100 years. Furthermore, mortality in mild‐to‐moderate COVID‐19 is very low, approximately 1 in 1300 [15]; therefore, our study should not be used for mortality analysis.

Understanding the statistical analysis of the article

One of the limitations of this study is that it performs too many statistical tests. The issue of multiple testing is straightforward: the more tests performed, the more likely it is to acquire a wrongly significant p‐value by chance. However, our observations of anosmia and ageusia were repeated more than once in different tests, which reduced the probability of it being generated by chance. We also strongly urge the reader to have the issue of multiple testing in mind while poring through the result of the data; one easy way to adjust for this issue is to reduce the significant level of p‐value so that the overall alpha error = 1 − (1 − α)m (where m is the number of tests in the symptomatology analysis −26 tests, and α is the new significant level for p‐value) reaches an acceptable number for the reader (usually 0.05). We generally avoid having a clear cut‐off for the significance of the p‐value because statistical tests with small sample sizes are “suggestive of a trend” rather than clearly proving causality or association. Therefore, the results of each test must be carefully concluded in their context.

SARS‐CoV‐2 was mutated in the old coronavirus family in 2019. One of the specific changes resulting from mutations is the virus's high affinity and direct attack on protein/receptor ACE2, which is located in human olfactory neurons. According to previous studies, SARS‐CoV‐2 enters the body by interacting with the ACE2 receptors, causing anosmia and ageusia. Our study observed a connection between BCG vaccination and ACE2 receptors, faster recovery from anosmia and ageusia, and lower odds of developing ageusia following BCG immunization. These findings suggest that BCG reduces the chance of acquiring COVID‐19, which is corroborated by previous studies [13, 16, 17, 18, 19]. Our study included many patients who presented with anosmia, ageusia, or both at the time of intervention (160 and 130, respectively, at T0). This robust sample size showed a statistically significant difference in recovery. Furthermore, these two symptoms tend to be less subjective than other COVID‐19 symptoms.

We also explored the in vitro interaction of a recombinant SARS‐CoV‐2 protein, and the synthetic ACE2 receptor in the presence of BCG stimulated plasma. In this assay, we evaluated the neutralization potential of plasma antibodies to inhibit the interaction between the SARS‐CoV‐2 SPIKE protein and the ACE2 receptor, which mimics a viral infection. In addition, we used this neutralization assay as an indicator of the homologous anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 humoral response since the assay was monoclonal.

BCG did not significantly change the absolute antiviral IgG levels or the absolute neutralization activity in our small sample; however, we observed a trend toward reduction in the neutralization normalized by IgG level (neutralization divided by IgG titer), which may indicate that the serum of BCG‐injected patients had the same capacity to neutralize the virus. However, a higher antibody concentration was needed to achieve the same neutralization percentage. Multiple studies have shown BCG to induce “heterologous” and “trained” immunity. It enhances the immune response to pathogens other than BCG (heterologous immunity). Moreover, it changes the behavior and trains part of the immune response that was previously considered innate (nonspecific cellular immunity that lacks the ability to learn). Therefore, the antiviral response following BCG injection might not be super specialized against the target protein because BCG‐induced immune changes are nonspecific and generally shift towards the cellular response. This reduced specificity can cause a desirable outcome because secondary infections and constant mutation of the virus are the main threats to the host in SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. A small mutation in the virus can turn monoclonal antibodies blind to the virus, and if the majority of the immune system is occupied with one specific antigen, they might miss a mutated virus and opportunistic bacteria. Heterologous immune training with BCG is considered responsible for reduced mortality from different respiratory infections in BCG‐vaccinated populations [11, 12, 20, 21].

In a 2021 study by Garcia‐Beltran et al. [22], neutralization capacity was decreased in severely ill COVID‐19 patients, showing that it might be important not to lower such ability. However, it is not clear whether a lower neutralization capacity is the cause or association of poorer outcomes. In addition, the sample size for their assay was relatively small (similar to our sample) and mostly involved hospitalized or critically ill patients, compared to our sample of relatively healthy individuals.

Long‐term effects and future vaccination adjuvant

Our recruited patients are under surveillance regarding the impact of BCG on post‐COVID chronic symptoms and sequelae in the long‐term follow‐up. In the future, BCG should be used as an adjunct to vaccination to enhance the effect of the vaccine as previously shown [23, 24, 25] and protect against mutated strains; further studies with larger sample sizes are needed to analyze the effect of BCG on different types of vaccines first (mRNA vs. inactivated virus, etc.) and then proceed with analyzing the improvement of vaccine efficacy and its protection against mutated variations.

Variability in response to BCG

Several studies have shown variable host responses to BCG based on the strain of the vaccine or previous exposure to BCG vaccination and Mycobacterium species. Brazil is a tuberculosis‐endemic region, with 100% expected to be vaccinated against BCG at birth. Our study subjectively reported previous BCG vaccination in infancy by visualizing the old scar (94% had a scar). BCG vaccine has proven safe irrespective of purified protein derivative skin reactivity or the interferon gamma release assay test, which expands the safety profile of BCG; once previous exposure to Mycobacterium has been used as a formal impediment parameter for BCG rechallenge [5, 26].

Last but not least, BCG is a live vaccine made of different strains around the globe, and our study showed no significant difference when comparing Brazilian and Russian BCG‐I strains regarding clinical evolution, severe adverse events, humoral immune response, and correlation with BCG vaccine lesion in the BATTLE trial (data not shown).

Conclusions

In adults with convalescent COVID‐19, BCG rechallenge is safe and offers cross‐protection against anosmia and ageusia with potential humoral response modulation. This strategy should be further explored to evaluate the vaccine potential for other COVID‐19 variants.

Funding

Author Leonardo O. Reis received funding from Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel, CAPES, Federal Government, Brazil (grant number: 88887.506617/2020‐00), General Coordination of the National Immunization Program–CGPNI/DEIDT/SVS/MS, Ministry of Health, Brazil (official letter number 465/2020), and National Council for Scientific and Technological Development—CNPq, Research Productivity (grant number: 304747/2018‐1).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Author contributions

M. J., K. B., F. A. V. D., L. S. B. D. C., C. F. G., K. L. F., A. C. P., P. A. F. L., C. L. M., and R. Y. collected clinical data and prepared the manuscript; A. C. P. performed experiments; M. J. performed statistical analysis of the data; Q.‐D. T., M. C. B., K. G. F., and L. O. R. were responsible for manuscript critical revision and intellectual contribution; and L. O. R. was responsible for supervision and funding acquisition. All the authors approved the final submitted version.

Supporting information

Supplementary Table 1. Local skin reactions following injection (T0‐T4).

Supplementary Table 2. Patient recovery time of already developed symptoms.

Supplementary Table 3. Characteristics and comorbidities of BCG and Placebo groups undergoing IgG analysis.

Supplementary Table 4. Symptom development in BCG group (n = 24) and placebo group (n = 15) undergoing IgG analysis.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge their volunteer patients. The BATTLE trial was supported by the Community Health Center (CeCom‐UNICAMP, Campinas‐SP‐Brazil) and Paulínia Municipal Hospital (HMP‐Paulínia‐SP‐Brazil), with special support from healthcare workers Robson Pereira da Silva and Humberto Alves Ferrari from the aforementioned centers, respectively.

Jalalizadeh M, Buosi K, Dionato FAV, Dal Col LSB, Giacomelli CF, Ferrari KL, et al. Randomized clinical trial of BCG vaccine in patients with convalescent COVID‐19: Clinical evolution, adverse events, and humoral immune response. J Intern Med. 2022;00:1–13.

Mehrsa Jalalizadeh and Keini Buosi are co‐first authors

Data availability statement

The collected nonpersonal patient data and material transfer in this study are available after communication and agreement with the lead contact.

References

- 1. World Health Organization . WHO World Health Organization global tuberculosis program. 20 November 2021. www.acpjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.7326/M21‐3507 (2021). Accessed 20 Nov 2021.

- 2. Pettenati C, Ingersoll MA. Mechanisms of BCG immunotherapy and its outlook for bladder cancer. Nat Rev Urol. 2018;15:615–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ministério da Saudé . Calendário Nacional de Vacinação. https://www.gov.br/saude/pt‐br/assuntos/saude‐de‐a‐a‐z/c/calendario‐nacional‐de‐vacinacao (2021). Accessed 20 Nov 2021.

- 4. Paulo PS. Nota técnica Cidade de São Paulo: Vacinação com a vacina BCG: indicações, contraindicações, eventos adversos e condutas. 19 November 2020. https://www.prefeitura.sp.gov.br/cidade/secretarias/upload/saude/nota_tecnica_10_2020_bcg.pdf (2021). Accessed 20 Nov 2021.

- 5. Bannister S, Sudbury E, Villanueva P, Perrett K, Curtis N. The safety of BCG revaccination: a systematic review. Vaccine 2021;39:2736–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pavan Kumar N, Padmapriyadarsini C, Rajamanickam A, Marinaik SB, Nancy A, Padmanaban S, et al. Effect of BCG vaccination on proinflammatory responses in elderly individuals. Sci Adv. 2021;7:eabg7181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ministério da Saudé . Manual de vigilância epidemiológica de eventos adversos pós‐vacinação. https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/manual_vigilancia_epidemiologica_eventos_vacinacao_4ed.pdf (2020). Accessed 20 Nov 2021.

- 8. Singh DD, Parveen A, Yadav DK. SARS‐CoV‐2: emergence of new variants and effectiveness of vaccines. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:777212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. O'neill LAJ, Netea MG. BCG‐induced trained immunity: can it offer protection against COVID‐19? Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:335–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Leentjens J, Kox M, Stokman R, Gerretsen J, Diavatopoulos DA, Van Crevel R, et al. BCG vaccination enhances the immunogenicity of subsequent influenza vaccination in healthy volunteers: a randomized, placebo‐controlled pilot study. J Infect Dis. 2015;212:1930–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gursel M, Gursel I. Is global BCG vaccination‐induced trained immunity relevant to the progression of SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic? Allergy. 2020;75:1815–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fu W, Ho P‐C, Liu C‐L, Tzeng K‐T, Nayeem N, Moore JS, et al. Reconcile the debate over protective effects of BCG vaccine against COVID‐19. Sci Rep. 2021;11:8356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Amirlak L, Haddad R, Hardy JD, Khaled NS, Chung MH, Amirlak B. Effectiveness of booster BCG vaccination in preventing Covid‐19 infection. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2021;17:3913–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rivas MN, Ebinger JE, Wu M, Sun N, Braun J, Sobhani K, et al. BCG vaccination history associates with decreased SARS‐CoV‐2 seroprevalence across a diverse cohort of health care workers. J Clin Invest. 2021;131(2):e145157. 10.1172/JCI145157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Clift AK, Coupland CAC, Keogh RH, Diaz‐Ordaz K, Williamson E, Harrison EM, et al. Living risk prediction algorithm (QCOVID) for risk of hospital admission and mortality from coronavirus 19 in adults: national derivation and validation cohort study. BMJ. 2020;371:m3731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wrapp D, Wang N, Corbett KS, Goldsmith JA, Hsieh C‐L, Abiona O, et al. Cryo‐EM structure of the 2019‐nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science. 2020;367:1260–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pang NY, Pang AS, Chow VT, Wang D‐Y. Understanding neutralizing antibodies against SARS‐CoV‐2 and their implications in clinical practice. Mil Med Res. 2021;8:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen M, Shen W, Rowan NR, Kulaga H, Hillel A, Ramanathan M, et al. Elevated ACE‐2 expression in the olfactory neuroepithelium: implications for anosmia and upper respiratory SARS‐CoV‐2 entry and replication. Eur Respir J. 2020;56:2001948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Meng X, Deng Y, Dai Z, Meng Z. COVID‐19, and anosmia: a review based on up‐to‐date knowledge. Am J Otolaryngol. 2020;41:102581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jodaylami MH, Djaïleb A, Ricard P, Lavallée É, Cellier‐Goetghebeur S, Parker MF, et al. Cross‐reactivity of antibodies from non‐hospitalized COVID‐19 positive individuals against the native, B. 1.351, B. 1.617. 2, and P. 1 SARS‐CoV‐2 spike proteins. Sci Rep. 2021;11:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gonzalez‐Perez M, Sanchez‐Tarjuelo R, Shor B, Nistal‐Villan E, Ochando J. The BCG vaccine for COVID‐19: first verdict and future directions. Front Immunol. 2021;8:632478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Garcia‐Beltran WF, Lam EC, St Denis K, Nitido AD, Garcia ZH, Hauser BM, et al. Multiple SARS‐CoV‐2 variants escape neutralization by vaccine‐induced humoral immunity. Cell. 2021;184:2372–83.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Covián C, Fernández‐Fierro A, Retamal‐Díaz A, Díaz FE, Vasquez AE, Lay MK, et al. BCG‐induced cross‐protection and development of trained immunity: implication for vaccine design. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Arts RJW, Moorlag SJCFM, Novakovic B, Li Y, Wang S‐Y, Oosting M, et al. BCG vaccination protects against experimental viral infection in humans through the induction of cytokines associated with trained immunity. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;23:89–100.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Leentjens J, Kox M, Stokman R, Gerretsen J, Diavatopoulos DA, Van Crevel R, et al. BCG vaccination enhances the immunogenicity of subsequent influenza vaccination in healthy volunteers: a randomized, placebo‐controlled pilot study. J Infect Dis. 2015;212:1930–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. WHO Expert Committee on Biological Standardization . Recommendations to assure the quality, safety and efficacy of BCG vaccines. Replacement of Annex 2 of WHO Technical Report Series, No. 745, and Amendment to Annex 12 of WHO Technical Report Series, No. 771. Geneva. 2013.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1. Local skin reactions following injection (T0‐T4).

Supplementary Table 2. Patient recovery time of already developed symptoms.

Supplementary Table 3. Characteristics and comorbidities of BCG and Placebo groups undergoing IgG analysis.

Supplementary Table 4. Symptom development in BCG group (n = 24) and placebo group (n = 15) undergoing IgG analysis.

Data Availability Statement

The collected nonpersonal patient data and material transfer in this study are available after communication and agreement with the lead contact.