Dodig et al 1 show electron micrographs to document infection of skeletal muscle by SARS‐CoV‐2 in biopsy samples of patients with COVID‐19, and report on their findings in a Brief Communication entitled “COVID‐19‐Associated Critical Illness Myopathy with Direct Viral Effects.” The putative virus particles are termed “coronavirus‐like particles” or “virus‐like particles.”

However, the images provided by Dodig et al 1 do not show virus particles. Most of the particles assigned as (corona)viruslike particles represent coated vesicles (Figure 1K–O and 2J–M), whereas Figure 1 R shows an unidentifiable structure that does not reveal sufficient features of coronavirus particles. Confusion of coated vesicles with coronavirus happened frequently because of the clathrin coat at the outer surface of the membrane, which resembles, at first sight, the spikes of a coronavirus. However, spikes of coronaviruses show a globular head group, are less evenly distributed at the particle surface, and appear less dense than the clathrin coat of coated vesicles (Figure 1). Moreover, coronavirus particles must show additional structural features such as a granular interior, representing the ribonucleoprotein, and a correct location within membrane‐bound compartments. 2 The (corona)viruslike particles in Figure 1K–O and 2J–M reveal a bright interior and are localized in the cytoplasm, which is, considering the overall sufficient preservation of membrane‐bound compartments shown by Dodig et al, not the correct location for coronavirus particles in infected cells. 3 Figure 1R shows a particle profile that is localized within a membrane‐bound compartment, but that is too wide in diameter (>200nm) and that reveals no surface structures (ie, spikes) and a rather unusual interior granularity.

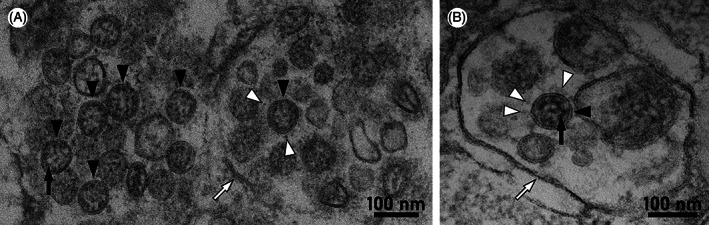

FIGURE 1.

Ultrastructure of coronavirus particles in autopsy lung. Well‐preserved coronavirus (CV) particles are highlighted by black arrowheads. The most characteristic feature of CV particles in thin section electron microscopy is the electron dense appearance and granular substructure due to presence of ribonucleoprotein (black arrows), whereas “spikes” reveal a faint contrast with a prominent globular head (white arrowheads). Intracellular CV particles are enclosed in membrane‐bound compartments (white arrows) that may be ruptured, like in image (A), due to, for example, autolysis, thus also limiting cell type assessment. See Krasemann et al. 5 for detailed recommendations of CV particle identification and information on the sample. Digitized thin sections and regions of autopsy lung are available online for open access pan‐and‐zoom analysis (www.nanotomy.org). 5

As for any other subcellular object identified by thin section electron microscopy, typical ultrastructural features must be demonstrated by using images of sufficient quality and information. Despite the publication of several comments (eg, Miller and Brealey, 3 Dittmayer et al 4 ) and more extended papers (eg, Bullock et al 2 ) on the difficulties of recognition of SARS‐CoV‐2 particles by electron microscopy in patient material, continuously more scientific papers with highly questionable coronavirus detection appear. In addition, false‐positive electron microscopy data have often been used to validate other in situ virus detection methods such as immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization, which detect virus molecules rather than the intact virus particle and can provide nonspecific results. A recent, unreviewed analysis of the literature found that at least 116 of 122 journal publications demonstrate clearly wrong subcellular structures as virus or provide only insufficient proof (ie, images) for the presence of coronaviruses. 5 To avoid further misinterpretations or false‐positive results, we strictly refer to the detailed recommendations on coronavirus identification and searching strategies.2, 5

Author Contributions

C.D. and M.L. wrote the manuscript and analyzed the data.

Potential Conflicts of Interest

Nothing to report.

References

- 1. Dodig D, Tarnopolsky MA, Margeta M, et al. COVID‐19‐associated critical illness myopathy with direct viral effects. Ann Neurol 2022;91:568–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bullock HA, Goldsmith CS, Zaki SR, et al. Difficulties in differentiating coronaviruses from subcellular structures in human tissues by electron microscopy. Emerg Infect Dis 2021;27:1023–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Miller SE, Brealey JK. Visualization of putative coronavirus in kidney. Kidney Int 2020;98:231–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dittmayer C, Meinhardt J, Radbruch H, et al. Why misinterpretation of electron micrographs in SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected tissue goes viral. Lancet 2020;396:e64–e65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Krasemann S, Dittmayer C, v Stillfried S, et al. Assessing and improving the validity of COVID‐19 autopsy studies—a multicenter approach to establish essential standards for immunohistochemical and ultrastructural analyses. medRxiv 2022: 10.1101/2022.01.13.22269205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]