Abstract

Background

This study explored dog owners’ concerns and experiences related to accessing veterinary healthcare during the COVID‐19 pandemic.

Methods

Data were obtained through two cross‐sectional owner‐completed surveys conducted in May (first nationwide lockdown) and October 2020 and owner‐completed diaries (April‐November 2020). Diaries and relevant open‐ended survey questions were analysed qualitatively to identify themes. Survey responses concerning veterinary healthcare access were summarised and compared using chi‐square tests.

Results

During the initial months of the pandemic, veterinary healthcare availability worried 32.4% (n = 1431/4922) of respondents. However, between 23 March and 4 November 2020, 99.5% (n = 1794/1843) of those needing to contact a veterinarian managed to do so. Delays/cancellations of procedures affected 28.0% (n = 82/293) of dogs that owners planned to neuter and 34.2% (n = 460/1346) of dogs that owners intended to vaccinate. Qualitative themes included COVID‐19 safety precautions, availability of veterinary healthcare and the veterinarian‐client relationship.

Conclusion

Veterinary healthcare availability concerned many owners during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Access to veterinary healthcare for emergencies remained largely available, but prophylactic treatments were delayed for some dogs.

Keywords: canine, COVID‐19, dog, veterinary, veterinary healthcare

INTRODUCTION

As part of the UK's COVID‐19 pandemic management, a range of lockdown measures were introduced across the UK nations for the first time on 23 March 2020. Further local restrictions and lockdowns followed throughout 2020/2021. In addition to restrictions on non‐essential travel and exercise outside of home, closure of non‐essential shops and other businesses, a ban on socialisation with people from outside of one's household and restrictions on the work of veterinary practices were introduced. Guidelines for veterinary work were published by the British Veterinary Association (BVA), outlining that for the period 23 March to 14 April 2020, only ‘urgent treatment and emergency healthcare’ were permitted. 1 The guidelines were subsequently amended; from 14 April, essential work beyond urgent and emergency healthcare was allowed. 2 As a consequence of BVA guidelines, some veterinary practices closed, 3 while others restricted their services. During the early stages of the first national lockdown, an 80%–90% reduction in veterinary consultations was observed, 4 with caseload being reduced throughout the rest of 2020, 5 although they reportedly returned to near‐normal from September 2020 onwards. 3

Although the guidelines specified that a short delay and disruption in the provision of non‐urgent healthcare was unlikely to affect the long‐term welfare of dogs, some veterinarians expressed concerns that even a brief disruption could influence owners’ long‐term healthcare‐seeking behaviour, in particular in relation to prophylactic treatment, such as vaccinations. 6 In reflection of this, a cross‐sectional industry‐issued survey administered across four countries (Brazil, USA, France and UK) between September and October 2020 showed that 28% of 608 pet owners had delayed or avoided contacting their veterinary practice since the beginning of the pandemic and 16% missed routine prophylactic treatment, such as vaccines. 6 Of those who delayed or avoided contact with veterinary practices, 41% believed that visiting a veterinarian is a non‐essential task. 6 A decrease in veterinary practice presentation for some life‐threatening conditions was also noted from the onset of the lockdown‐related restrictions, 7 possibly due to owners being more reluctant or unable to seek veterinary healthcare, mirroring human healthcare seeking. 8 Research conducted prior to COVID‐19 identified additional barriers for pet owners accessing veterinary healthcare, including finances and transportation. 9 Further evidence suggests that people with disabilities may be at greater risk of encountering these barriers and that the pandemic has further jeopardized the affordability and accessibility of veterinary services among this population. 10

Social distancing measures introduced to reduce COVID‐19 transmission changed how consultations were conducted and consequently how owners communicated with veterinarians. For example, owners were often not allowed to accompany their dogs into consulting rooms and needed to wear protective clothing when permitted inside. 6 Visiting clients at home, including at‐home euthanasia procedures, was discouraged. 11 Most veterinary practices began to rely, at least partially, on telemedicine for a range of healthcare issues. 4 Given the importance of good communication between veterinarians and pet owners for client satisfaction, 12 we hypothesise that COVID‐19‐related changes to veterinary service delivery may have affected dog owners’ attitudes towards and experiences of healthcare seeking during the pandemic, which this study explores.

Previous studies have analysed dog owners’ experiences in relation to healthcare seeking during the initial months of the pandemic using one‐off, cross‐sectional surveys 13 but the impact of COVID‐19 over time is unexplored as of yet. Therefore, focusing on the first 8 months of the COVID‐19 pandemic, this study aimed to 1) explore dog owners’ concerns and experiences related to accessing veterinary healthcare and 2) describe owner‐reported access to veterinary services. We hypothesise that access to veterinary services has been affected during the pandemic, with routine treatments likely to have been delayed. As data collection for this research is ongoing, future studies will focus on the longer‐term impact of the pandemic on dog owners’ experiences.

The findings of this study are discussed within the COM‐B model of human behaviour change, 14 as it lends itself to developing recommendations for how to maintain and improve engagement with veterinary healthcare. The COM‐B model suggests that behaviour (such as seeking relevant veterinary healthcare) is shaped by one's capability, opportunity and motivation. 14 Psychological capability describes a person's knowledge, skills and psychological strength and physical capability refers to their physical ability. 14 Opportunity captures a number of physical and social factors that make the behaviour possible (such as location, resources or social norms 14 ). Finally, motivation refers to both reflective and automatic processes that lead to a behaviour (e.g., conscious planning but also one's impulses, desires and emotions 14 ). Motivation is also shaped by one's capability and opportunity. 14

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data were obtained through two owner‐completed surveys and two electronic diaries (completed by members of the general public and participants of “Generation Pup”, an ongoing cohort study 15 ).

Surveys

Both surveys were hosted on the online survey platform SmartSurvey. A combination of closed‐ and open‐ended questions was used. The closed‐ended questions inquired about dogs’ daily routines, behaviour 16 and concerns regarding access to veterinary healthcare. An open‐ended question asked owners to discuss any concerns related to dog ownership during this time. In response to this question, many owners discussed concerns regarding access to veterinary healthcare and experiences related to veterinary access. 17 Sampling for the first survey was based on the following eligibility criteria: survey participants were required to be at least 18 years of age and to live in the UK. The follow‐up survey was administered to the respondents of the first survey who had agreed to be contacted about a follow‐up questionnaire.

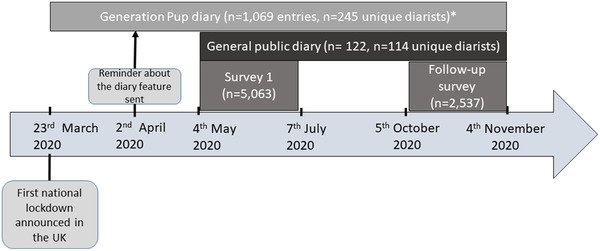

The second survey included similar questions to those included in the first survey and questions regarding access to veterinary healthcare for emergency and non‐emergency issues, access to preventative healthcare services (i.e., neutering, vaccination, worming treatments and nail care) and open‐ended questions about concerns related to dog ownership and experiences of accessing veterinary healthcare during the pandemic. Availability of both surveys is summarised in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Availability and number of respondents for survey 1, follow‐up survey and Generation Pup diary. *The diary feature was already available to Generation Pup participants before the pandemic; however, they were reminded of this feature in an email sent on 2 April 2020

The first survey was promoted via Dogs Trust's social media channels, a Dogs Trust e‐newsletter to supporters, an article in New Scientist magazine and emails to dog owners participating in the Generation Pup study or the Dogs Trust Post Adoption study. Participants in a previous survey administered by the Dogs Trust research team who had consented to be contacted about further research opportunities were also invited to participate. Participants of the first survey who had consented to be contacted about further research opportunities were invited by direct email to complete the follow‐up survey.

Electronic diaries

In addition to the two surveys, dog owners were able to complete one of two electronic diaries (for the timeline of diaries’ availability, see Figure 1). The general public diary entries were collected using an online survey platform (SmartSurvey); the Generation Pup diary was built into the participants’ online dashboard. 15 In both cases, an open‐ended question asked participants to describe if and how their dog's life in general and their relationship with their dog(s) had been impacted by the lockdown. Several prompts were provided to help participants think about how the lockdown may have affected them and their dog(s). 17 Owners were able to make one‐off or multiple entries. The diaries were analysed qualitatively, as explained below. The electronic diary was promoted to the general public in the same ways as the first survey.

The minimum age to participate in the general public electronic diary study was 18 years and participants were required to live in the UK. Participants could take part in the general public diary study even if they did not own a dog at the time of participation but wanted to share their thoughts and experiences regarding dogs during the pandemic (e.g., prospective owners seeking to acquire a dog). To take part in the Generation Pup study, owners need to be at least 16 years old, live in the UK or Republic of Ireland (ROI) and have a dog aged under 16 weeks (or 21 weeks if entering the country via a quarantine) at the time of enrolment. Further methodological details regarding the Generation Pup study are described elsewhere. 15

An informed consent statement was provided on the first page of the survey/diary study that outlined the study objectives, explained that participation in the study was completely voluntary, and provided instructions on how to withdraw from the study. Generation Pup participants provided informed consent at the point of registration. 15

Data Analysis

Mixed‐method (qualitative and quantitative) analysis was carried out, as it allows both confirmatory and exploratory questions to be answered. For example, whereas quantitative analysis helps to describe the pattern of access to veterinary healthcare through numbers, percentages and statistical tests, qualitative analysis enables exploring reasons for these patterns by identifying key themes. 18 This approach helps to make the results more robust by allowing triangulation of data collection and enabling a discussion based on separate analyses of data on the topic of access to veterinary healthcare. 18 , 19

Quantitative analysis

Summary statistics were used to describe responses to the survey. The statistical analysis focused on the data relating to the proportion of neutering, vaccinations, worming and nail trimming procedures/treatments among those for whom a given procedure or treatment was relevant. The outcomes (i.e., ‘occurred as planned’, ‘delayed’, ‘did not occur’) were analysed using chi square statistics and, where relevant, Fisher's exact tests with simulated p values, using 5000 simulations. Quantitative analysis was carried out in R software (version 4.0.2). 20

Qualitative analysis

Responses to open‐ended survey questions and diary entries were imported into NVivo (v.12, QSR) and analysed using thematic analysis. 21 Coding followed an inductive approach, whereby codes and themes were guided by the content of the responses. Each response was independently coded by one of six authors (Katharine L. Anderson, Katrina E. Holland, Lauren Harris, Rebecca Mead, Sara C. Owczarczak‐Garstecka, Lauren Samet) who met regularly to discuss the assigned codes and ensure consistency. Codes were applied to represent the content described by respondents. Codes were then organised into potential themes and subthemes, which were reviewed and discussed between the coders to agree on the names and definitions. Responses, or sections of responses, could be coded under multiple themes. Finally, we organised similar themes into meta‐themes to provide an overview of the topics and issues identified. Here, we present the themes concerning access to veterinary services and related experiences.

RESULTS

Description of the study population

The first survey was answered by 5063 respondents, of whom 3425 consented to follow‐up contact and 50.1% (n = 2582) completed the follow‐up survey. A total of 1069 and 122 diary entries (completed by 245 and 114 respondents) were completed by the Generation Pup and general public respondents, respectively. Of the general public diarists, the majority (98.2%, n = 112) were dog owners, with only two respondents reporting not owning a dog. The demographic characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1. The majority of participants were female (89.0% of the sample), and the most common age group was 55‐64 years of age. More details about the characteristics (including demographic data for the owned dogs) of a sample of survey 1 and Generation Pup diary respondents are described in previous work. 16

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics of respondents who completed general public diaries, Generation Pup diaries or Survey 2 (n, %)

| General public diarists | Generation Pup diarists | Survey 2 respondents | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n, (%) | n, (%) | n, (%) | sample n, (%) |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 103 (91.2) | 225 (93.0) | 2283 (88.6)c | 2611 (89.0) |

| Male | 10 (8.8) | 17 (7.0) | 243 (9.4)c | 270 (8.2) |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18‐24a | 7 (3.1) | 7 (2.7) | 62 (2.4) | 76 (2.8) |

| 25‐34 | 14 (10.9) | 33 (12.7) | 255 (9.9) | 302 (11.1) |

| 35‐44 | 19 (14.1) | 39 (15.1) | 272 (10.6) | 330 (12.2) |

| 45‐54 | 20 (23.4) | 64 (24.7) | 699 (27.1) | 783 (28.9) |

| 55‐64 | 31 (31.3) | 77 (29.7) | 704 (27.3) | 812 (29.9) |

| 65‐74b | 16 (12.5) | 39 (15.1) | 356 (13.8) | 411 (15.1) |

| 75‐84 | 6 (4.7) | n/a | 66 (2.6) | n/a |

| 85+ | 1 (1.6) | n/a | 3 (0.1)d | n/a |

This age category was defined as 16−24 in the Generation Pup Electronic Diary.

The oldest age category in the Generation Pup Electronic Diary was age 65+.

In addition, 0.4% (n = 11) of respondents chose to self‐identify (e.g., as gender fluid or nonbinary); 0.7% (n = 17) preferred not to say and 0.9% (n = 23) did not answer this question.

A small number, 0.2% (n = 5), of respondents chose not to disclose this information.

Veterinary healthcare seeking during the COVID‐19 pandemic

The availability of veterinary healthcare during the pandemic was a concern for 32.4% (n = 1431/4922) of respondents to the first survey. Responses to the follow‐up survey revealed that 22.2% (n = 563/2537) of respondents had experienced a consultation that was carried out remotely (i.e., by telephone, video or email) at any time since the start of lockdown. The vast majority of respondents to the follow‐up survey who sought contact with their veterinary practice were able to have their dogs seen (Table 2), although many experienced delays (Table 3). The experiences related to these changes are discussed in more detail in the subsequent section.

TABLE 2.

Results from the follow‐up survey on owners’ contact with their veterinary practice for emergency and non‐emergency health issues during the COVID‐19 pandemic (since the start of lockdown on 23 March 2020)a

| Able to be seen by veterinary practice | Unable to be seen by veterinary practice | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n, (%) | n, (%) | n, (%) | |

| Needed to contact veterinary practice | n/a | n/a | 1965/2537 (77.5) |

| Sought a nonemergency appointment | 1439/1480 (97.2) | 41/1480 (2.8) | 1480/1965 (75.3) |

| Sought an emergency appointment | 315/323 (97.5) | 8/323 (2.5) | 323/1965 (16.4) |

| Made an emergency visit without an appointment | 40/40 (100) | n/a | 40/1965 (2.0) |

It was possible to select multiple predefined responses to this question; for example, respondents were able to report seeking care for both nonemergency and emergency issues.

TABLE 3.

Results from the follow‐up survey on the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on routine healthcare treatments

| Neutering (n, %) | Worming (n, %) | Vaccination (n, %) | Nail trimming (n, %)a | Chi Square statistic [df] (p value) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | |||||

| Procedure/treatment was due, planned or required | 293 d (12.1) | 2220 c (91.7) | 1346 (55.4) | 1459 (56.9) | 3107.8 [3] (< 0.0001) |

| Procedure/treatment not due, planned or required | 2131 c (87.9) | 202 d (8.3) | 1084 (44.6) | 1107 (43.1) | |

| Total | 2424 | 2422 | 2430 | 2566 | |

| Outcome where procedure was due, planned or required | |||||

| The procedure/treatment did not take place due to COVID‐19 | 52 c (17.8) | 58 (2.6) | 141 (10.5) | 34 (2.3) | 1529.2 b [12] (< 0.0001) |

| The procedure/treatment did not take place for reasons not related to COVID‐19 | 104 (35.5) | 79 (3.6) | 36 (2.7) | 28 (1.8) | |

| The procedure/treatment took place as planned | 101 d (34.5) | 1978 (89.1) | 842 (62.6) | 1397 (91.8) d | |

| The procedure/treatment took place but was delayed due to COVID‐19 | 30 (10.2) | 88 (4.0) | 319 (23.7) | 34 (2.2) | |

| The procedure/treatment took place but was delayed for reasons not related to COVID‐19 | 6 (2.1) | 17 (0.8) | 8 (0.6) | 28 (1.8) | |

| Total | 293 | 2220 | 1346 | 1521 | |

Abbreviation: df, degrees of freedom.

aMultiple choices in response to the question about nail trimming were enabled. Nails were trimmed by a household member: 559/1459 (37.7%); by veterinary staff: 227/1459 (15.6%); and by a groomer: 611/1,459 (41.9%).

One cell included expected value < 5. Fisher's exact test with simulated p value p < 0.0001.

Standardised residuals ≥10.

Standardised residuals ≤10.

Impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on routine healthcare procedures/treatments

Restrictions on non‐emergency healthcare impacted standard preventative healthcare procedures by leading to delays and cancellations; however, most respondents who sought to access a veterinarian for neutering, worming, vaccination or nail trimming were able to do so (Table 3). Among the dogs for whom a particular procedure/treatment was relevant (i.e., due, planned or required), compared to other procedures, neutering was significantly less likely than expected by chance to take place as planned and more likely not to take place for COVID‐19 and non‐COVID‐19 reasons (Table 3). Compared to other procedures, vaccination was also significantly less likely to take place as planned and was more likely to have not taken place or been delayed due to COVID‐19. Compared to other procedures, both worming and nail trimming were more likely than expected by chance to take place as planned and less likely to be delayed due to COVID‐19 (but there did not seem to be an increase in these not taking place).

Survey free‐text and diaries analysis

Analysis of open‐ended questions and diary entries was performed to better understand dog owners’ concerns and experiences related to veterinary healthcare during the pandemic. Three meta‐themes were identified that relate to different aspects of owners’ concerns and experiences. Themes and illustrative quotes are presented in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

Common themes relating to experiences or concerns about accessing veterinary healthcare during the COVID‐19 pandemic

| Meta‐theme | Theme | Subtheme | Example quotation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. COVID‐19 safety precautions at veterinary practice | COVID‐19 safety precautions in place | “Very helpful and they have reorganised their building and procedures to take account of Covid.” (Survey) | |

| Contactless ordering, payment or collection of medication | “We contact the vets for [dog name]’s worm/flea treatment. We phone them on arrival they put his medication in a box and we receive it with no contact.” (Survey) | ||

| “Fortunately, the veterinarian was able to do the consultation by video call, and I was able to pay for and collect the protective cone and medication in a contactless fashion.” (General public diary) | |||

| Socially distanced consultations | Telemedicine | “The consultation was video web based call with vet.” (Survey) | |

| “The combination of technology between the [name of the] app and the use of phone and text message‐ including a google maps link for directions allowed truly effective care to be given to [dog's name] and I am very grateful for this.” (Generation Pup diary) | |||

| Car park consultations | “We have attended the vets for her annual vaccinations and for diagnosis of her leg injury (…) it was strange to be expected to stand in the street whilst waiting, rather than go in the examination room with [dog name], and then to have a conversation in the street about her treatment.” (General public diary) | ||

| “When we decided to put him to sleep they brought him out to the car park and administered the drug through a long line so they were 2 metres away from us, they enabled us to be with him at the end.” (Survey) | |||

| Difficulties communicating effectively | “Frustrating as weren't allowed in the surgery during the consultation so couldn't truly get to the bottom of a couple of small issues with [dog name].” (Survey) | ||

| Inability to accompany dog inside practice | (Owner's dissatisfaction) | ||

| “We truly dislike being unable to be with them during appointments.” (Survey) | |||

| “Although absolutely necessary, the process felt alien and unsettling. It felt like being at checkpoint on the border to an emerging dystopia.” (Generation Pup diary) | |||

| (Dog's experience or perspective) | |||

| “Owner is not allowed in to [sic] the surgery and this has caused [dog name] anxiety/lots of howling.” (Survey) | |||

| “[Dog's name] enjoys going to the vet and is quite happy going into the vets while I wait outside” (Survey) | |||

| (Fear of and experience of dog being euthanised without the owner) | |||

| “Although we were unable to be with [dog's name] when he went to sleep our vet was extremely good and very compassionate and we were able to spend time with [dog's name] in the garden at the vets.” (Survey) | |||

| “We had [dog's name] put to sleep (…) [in] May. It was very upsetting as we could not go into the vets surgery because of covid 19 restrictions.” (Generation Pup diary) | |||

| Delaying seeking veterinary healthcare | “The fear of [dog name] needing to be put to sleep without me being there (i.e., at the emergency vet where I'm not allowed in) has delayed me getting help when she has needed it in the night.” (Survey) | ||

| “She has definitely not missed having her check up or injections which were due in April! The vet (…) was prepared to do them but the regulations said only emergencies and as several members of staff were off sick we thought it safer to stay away, [w]e[‘](sic) are both over 75.” (Generation Pup diary) | |||

| 2. Availability of veterinary healthcare | Issues accessing veterinary healthcare | Difficulties or delays accessing veterinary healthcare | “The access to vets has been difficult. We were not allowed to come in but no one is ever picking up the phone and they only occasionally reply to emails. This has been very difficult to use as [dog name] is (…) in need of daily medication that we struggle to get” (Survey) |

| “My dog truly needed to be seen by a vet earlier. Her follow up appointments were cancelled because of COVID and it turned out she had cancer.” (Survey) | |||

| Limitations on veterinary healthcare available | “[Dog name]’s vets are still only open for emergencies so he hasn't been able to have a health check or booster.” (Survey) | ||

| Owner‐related barriers to access | “We haven't been able to get flea/worming treatment whilst in isolation so this is now overdue.” (Survey) | ||

| “I knew I couldn't afford a huge vet bill, so I chose to take [dog name] home and monitor him closely overnight…” (Generation Pup diary) | |||

| Owner performing veterinary care themselves | “His nails are done by me with a dremel.” (Survey) | ||

| “[Dog name] did get an abscess following a wound that got infected and I thought she should have antibiotics but vet was only seeing emergencies and it wasn't that bad so I treated it myself with antiseptic solutions that I had in stock and it healed after a few days.” (Survey) | |||

| No issues accessing veterinary healthcare | Easy to make appointments or to attend | “No problem at all obtaining appointment at usual vets.” (Survey) | |

| “I have been able to have any vet appointments I have needed for my dogs.” (Survey) | |||

| Concerns around the availability of veterinary healthcare should they need it | “Have a slight concern over the provision of veterinary care if needed.” (Survey) | ||

| “If they get poorly and a vet isn't available.” (Survey) | |||

| 3. Veterinarian‐client relationship | Dog's relationship with veterinary staff | “As [dog's name] loves going to the vet, it will be a real treat for her one day when this is all over.” (Generation Pup diary) | |

| “[Dog name] required a veterinary appointment during lockdown this went as well as possible due to restrictions, but increased her stress as owners [sic] unable to calm her down going inside & had to hand her over to essentially a stranger even though it was a vet.” (General public diary) | |||

| Owner's relationship with veterinary staff | “(…) very pleased with care and compassion from vet.” (Generation Pup diary) | ||

| “I truly trust our veterinary team.” (Survey) | |||

| “He was apparently distressed and was muzzled for the vaccinations by a vet I did not know.” (Survey) | |||

| Seeking veterinary healthcare elsewhere | “We have changed vets to one that will allow routine check ups and for us to be present (with social distancing).” (Survey) | ||

| “My vets practice is small and we are still unable to attend with our dogs inside. As my dogs don't truly like strangers I am going to have to change vets to a newer one with larger rooms so I can go in with them. I am truly disappointed as I love my vet, but I guess that's just a safety issue they can't help at the moment.” (Survey) | |||

| Quality of healthcare | Positive experiences | “The vet practice that I use have been brilliant throughout lockdown. They were always available.” (Survey) | |

| “I also had a couple of phone calls with them for minor grazes to her ankles and they were truly kind and helpful.” (General public diary) | |||

| Negative experiences | “our other dog needed to be seen by the vert (sic) for a suspicious lump (…). but because of Covid we couldn't go in to the vert (sic) with her. when the vet examined her they couldn't find it and said there was nothing wrong with her but the lump is still there.” (Survey) | ||

| “Concerned that the practice is not running as efficiently as it should, resulting in difficulties and delays.” (Generation Pup diary) |

Meta‐theme 1, ‘COVID‐19 safety precautions at veterinary practice’, is characterised by descriptions of how COVID‐19‐related measures have led to changes in veterinary service delivery. For instance, personal protective equipment was commonly used, and social distancing was also seen in practices. In many cases, owners were collecting medication without seeing a veterinary professional (in particular, repeat prescriptions and flea/worming treatment). Many veterinary practices employed telemedicine as a way of running consultations: owners described consultations on the phone/through emails and specialist apps. Many participants were satisfied with this service; however, some said it was hard to ask questions and to understand the veterinarian. Participants also described consultations taking place in a car park instead of inside the clinic building. For some, this was a welcome change, as they thought their dog was worried by being inside the clinic, while others complained about a lack of privacy (in particular, when their dog was euthanised in the car park). Many described that their dog was seen without the owner being present. Most owners described this as stressful, explaining that they wished to be with their dog during the consultation to provide reassurance. Some also mentioned that not being with the dog during the consultation further hindered communication with the veterinarian, which they perceived in some cases led to missed diagnoses or further health complications. Being unable to be with the dog during the consultation was particularly stressful for owners who were considering euthanasia, owners of dogs with behavioural issues and those who owned elderly dogs.

Meta‐theme 2, ‘Availability of veterinary healthcare’, comprised data referring to attitudes about the availability of veterinary healthcare and issues accessing veterinary healthcare where it was sought. Some respondents were uncertain whether healthcare would be available, should it be needed, or if they would be able to access it, for instance, if they were isolating. Others reported on experiences of attempting to obtain veterinary healthcare. While some respondents stated that they had no difficulty doing so, others expressed difficulty making appointments for non‐emergency reasons. Some respondents were unable to even contact their practice. Most owner‐reported barriers to accessing veterinary healthcare or advice were related to the veterinary practice's adoption of COVID‐19‐related restrictions, and in particular, asking owners not to accompany their dogs into the practice, but some respondents also cited personal health, transport or financial reasons.

Meta‐theme 3, ‘Veterinarian‐client relationship’, covers aspects of responses that refer to the pandemic's impact on a respondent's (and/or their dog's) relationship with their veterinarian. This included references to an owner's or dog's familiarity with staff at their veterinary practice. This meta‐theme follows closely from meta‐theme 2, as the respondents often explained that their relationship with veterinarians was strengthened or undermined by the availability of healthcare, which also impacted the ‘Quality of Healthcare’. In some cases, respondents suggested that relationships had been terminated or were at risk of this, as some owners reported seeking veterinary healthcare elsewhere during the pandemic.

DISCUSSION

This study explored the experiences and concerns of UK and ROI dog owners related to veterinary healthcare during the COVID‐19 pandemic, including the likelihood of obtaining relevant veterinary healthcare during this period.

The availability of veterinary healthcare during the initial months of the pandemic was a worry for over one‐third of survey participants. Similar concerns about the availability of veterinary healthcare during the pandemic have been reported by owners in the UK 22 as well as other countries, including Spain, the US, Canada and Australia. 13 , 22 , 23 , 24 Despite these concerns, the vast majority of this study's respondents who needed to access veterinary services since the lockdown began were able to do so. Nonetheless, delays in access to preventative healthcare were reported. Interpreting these findings within the COM‐B model of human behaviour change, they demonstrate that while the opportunity to seek help did not disappear, it was restricted and plausibly impacted upon owners’ motivation to seek treatments for their dogs.

Both the statistical analysis performed in this study and the qualitative subtheme ‘Limitations on veterinary healthcare available’ show that, in particular, neuter/spay procedures were less likely than other procedures to take place as planned and more likely not to take place due to COVID‐19. In addition, over one‐third of owners who planned to neuter or spay their dogs were unable to do so for reasons unrelated to COVID‐19. Insights from the qualitative analysis suggest that this could have been a result of dogs coming into season shortly before the planned procedure. Vaccinations were also more likely than other procedures to be delayed or not to take place as planned due to the ongoing pandemic. However, statistical analysis showed that worming and nail trimming were not affected by the neutering and vaccination procedures. This may be because owners may have already had supplies at home, were able to purchase non‐prescription worming treatments or collect and administer medication themselves without seeing a veterinarian. Even prior to the pandemic, many practices allow owners to collect repeat worming medication without appointment, providing the dog is under their care and has been seen by a veterinarian within a given period (e.g., in the previous 12 months). This means that opportunities to provide dogs with worming treatments that did not require face‐to‐face contact were already in place before the pandemic, so administering this treatment did not require behaviour change from dog owners. This was reflected in survey free‐text responses and diary entries coded as ‘Contactless ordering, payment or collection of medication’. Compared to other procedures, a greater number of owners required nail trimming for their dogs. It is possible that this is because nail trimming needs to be carried out regularly throughout a dog's life (if a dog does not wear their nails down on walks), whereas other procedures are conducted once (neutering) or with a lesser frequency. The high likelihood of nail trimming taking place as planned during the pandemic may be partly explained by findings from this study's qualitative data, which indicates that some owners began performing this task themselves or obtaining this service from other sources, such as dog groomers. In other words, for many owners, nail trimming was not disrupted in the same way as other veterinary treatments or procedures.

The qualitative analysis in this study provides further insights into the experiences of owners seeking veterinary healthcare during the pandemic. Responses assigned to the meta‐theme ‘Availability of veterinary healthcare’ highlighted that while some owners were able to book an appointment easily, others experienced difficulties. For many owners, appointment booking required more effort than prior to the pandemic, particularly for non‐emergency issues, which may have affected owners’ capability and motivation to engage with veterinary healthcare. The reasons for the reported diversity in owner experiences of attempting to seek veterinary healthcare during the pandemic are likely complex but may include the health status of veterinary practice staff, as well as the prevalence rate of COVID‐19 in different geographical areas throughout this time. Environmental and physical factors, such as the practice layout and availability of suitable outside space, may have also played a role in how practices responded to the guidelines, potentially leading to different experiences between owners attending different practices.

A small number of participants believed that delays in the availability of consultations negatively impacted the health or welfare of their dog. The delays in getting an appointment may have meant that those waiting for a consultation had to wait longer, with some owners speculating that delays led to a deterioration of their dog's health. Some participants thought that delays and rushed “catch up” consultations contributed to a lower quality of healthcare. It is also possible that the quality of consultations remained the same, but the perception of quality was altered, as previous research has highlighted that consultations experienced as rushed are often believed to be of worse quality than consultations where owners thought they had time to ask questions. 25

While short‐term delays in the provision of preventative healthcare, such as vaccinations, are unlikely to impact the health of most dogs, the very young or elderly population may be negatively affected due to being immunocompromised. 26 In addition, delays to vaccinations of puppies could have affected their socialisation opportunities, increasing the risk of behavioural problems later in life. 27 , 28 Difficulties in accessing non‐emergency appointments and complementary therapies (e.g., hydrotherapy) may have also had a negative impact on dogs living with chronic health issues, who may be more dependent on regular check‐ups and access to diagnostic tests to monitor their health and welfare.

Previous research identified that an owner's inability to be present with their dog during veterinary consultations was a major concern for owners during the initial months of the pandemic. 13 This aligns with our findings, as many of the qualitative responses were related to owners’ dissatisfaction about being unable to accompany their dog inside the veterinary practice. This led some participants to delay seeking veterinary healthcare (including euthanasia) until they were allowed to be present with their dog. This shows that being unable to accompany a dog into the practice affects the owner's motivation to seek help, at least when owners believe that veterinary intervention can be delayed. As owners usually choose to be present during euthanasia, 29 being unable to do so is potentially distressing and may have a significant impact on owners’ mental health, 30 which warrants further research. Some owners described seeking veterinary healthcare from an alternative practice operating with more relaxed procedures. These findings illustrate that many participants consider accompanying a dog to the veterinarian an important practice for maintaining human‐dog relationships. 13 Owners’ capability, here reflected in their emotional capacity to cope with being separated from the dog during a treatment, and the dog's (perceived) capability to go into the veterinary practice unacompanied by the owner shaped owners’ decisions around seeking veterinary care.

Our survey identified that one‐fifth of respondents had experienced a remote consultation during the pandemic, illustrating the extent to which this technology provided opportunities for veterinary staff to deliver care when in‐person consultations were restricted. Other evidence indicates that more consultations were conducted using telemedicine in the initial weeks following 23 March 2020 than before the pandemic. 4 Although this was not often mentioned in the analysed data, teleconsultations may have been of particular importance to dog owners who were shielding or experiencing COVID‐19 symptoms or unable to physically access a veterinarian for other reasons. Telemedicine may have therefore improved some owners’ opportunity to obtain veterinary advice during the pandemic. However, an owner's physical presence may shape their perception of veterinary diagnosis and quality of healthcare, helping to develop and maintain their relationship with the veterinarian. Previous research suggests the importance of owner‐veterinarian dialogue and owner engagement in the process of diagnosing a pet, for example, by referring to the owner's own medical history and experience but also observing a veterinarian examining the dog or interpreting diagnostic tests. 31 Therefore, being present during consultations may be important for reaching a diagnosis and owners’ understanding of and possibly compliance with veterinary advice. Unsurprisingly, therefore, the main reasons why owners reported feeling concerned about the efficacy of telemedicine were the veterinarian being unable to see the dog and perform a physical examination, as well as difficulties in understanding the veterinarian and asking questions. Owners unfamiliar or uncomfortable with technologies used to conduct teleconsultations and those with disabilities may have been especially affected. 10 As adopting a relationship‐centred approach to communication may improve veterinary‐related outcomes (e.g., the uptake of veterinary advice), 32 future telemedicine practice should consider how to use technology to bring the owner back into the veterinary consult room and involve them in the diagnostic process.

Given the emphasis on the veterinarian‐dog owner relationship identified in our qualitative data and in light of our study's exclusive focus on dog owners, a comment on how the pandemic has impacted veterinarians themselves is warranted. Previous research suggests that veterinary staff have experienced an increased frequency of ethically challenging situations at work during the pandemic. 33 While not all challenging situations were a result of the pandemic, uncertainty about what can be defined as an “essential” service and whether potentially coming into contact with a client is needed added to veterinary team members’ concerns. 33 As the experience of veterinary professionals was beyond the scope of this study, future studies are required to further understand the impact of the pandemic on this population.

Strengths and limitations

The survey/diary results of this study are based on data obtained from a large sample of dog owners. The study results were also triangulated by using more than one approach to data collection (surveys and diaries) and applying different types of analysis (qualitative and quantitative), which improves the rigour of this study. 19 However, this study is limited by potential sampling bias due to the self‐selection of participants. Self‐selection may have resulted in overrepresentation of owners interested in or motivated towards good welfare for their dogs and thus perhaps more likely to seek veterinary healthcare, despite perceived barriers. In addition, this study's participants were mostly females. While this reflects previous studies of human‐pet relationships, 13 , 16 , 34 future research should attempt to recruit more male respondents to minimise this bias, increase the generalisability of findings to a wider population of dog owners and investigate whether owner gender affects veterinary healthcare‐seeking attitudes and behaviour. Moreover, the number of respondents who reported seeking veterinary services for emergency or nonemergency health issues does not equate to the number of respondents who said that they needed veterinary services for any issue. This is possibly due to respondents seeking veterinary services remotely (e.g., through telemedicine); however, due to the structure of questions in the survey, we were unable to determine this.

Data collection for this research project is ongoing, and in this study, we have not explored owner‐related factors (e.g., gender; age; COVID vulnerability status; geographical location) or dog factors (e.g., breed; age) as confounding variables associated with access to veterinary healthcare. We hope to expand on the quantitative analysis in the future when the data collection is complete.

CONCLUSION

These findings are consistent with our hypothesis that dog owners’ access to veterinary care was affected by the pandemic. This study provides evidence that in the UK and ROI, prophylactic treatments for some dogs were delayed during the COVID‐19 pandemic, affecting opportunities to seek help, but access to veterinary healthcare for emergencies remained largely available. Nonetheless, this study's qualitative insights illustrate owners’ concerns and worries about the potential availability of veterinary healthcare. The findings also suggest that experiences of owner‐veterinarian‐dog encounters were often affected by COVID‐19 safety precautions that typically prohibited owners from accompanying their dog within the veterinary practice. This affected some owners’ capability and motivation to seek help, which resulted in some owners delaying seeking veterinary healthcare, potentially adding to health concerns, while others sought help from a different practice. Therefore, the pandemic resulted in additional perceived barriers to seeking veterinary healthcare for owners. Difficulties in booking appointments, greater effort needed to book them and inability for owners to be present with their dog during the veterinary encounter may impact owners’ healthcare‐seeking behaviour.

Our findings suggest the need for a review of communication from veterinary professionals to pet owners regarding their intentions to remain open to urgent issues or emergencies to mitigate owners’ fears. Furthermore, as future lockdown and veterinary services disruptions are possible, steps to improve veterinarian‐owner communication while practicing social distancing should be encouraged, with a particular focus on involving the dog owner in the diagnostic process even when not physically present during the consult. Postconsultation follow‐ups with owners may provide an opportunity to clarify any misunderstandings. In addition, further effort is needed to remove possible technological barriers associated with teleconsultations, which may disproportionally affect owners unfamiliar or uncomfortable with such technologies and those with disabilities. Finally, socialising dogs to veterinary facilities and formal veterinary handling early in life could encourage owners to seek veterinary care promptly, even when unable to accompany a dog into the practice, by improving a dog's capability to enter the veterinary practice unaccompanied and their owner's confidence in this.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research received no external funding. Both surveys and the electronic diary open to the public were supported by Dogs Trust. The ‘Generation Pup’ study was initially funded by the Dogs Trust Canine Welfare Grant and now Dogs Trust funds ‘Generation Pup’.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors are all employees of Dogs Trust, the UK's largest dog welfare charity. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualisation: Sara C. Owczarczak‐Garstecka, Katrina E. Holland; methodology: Sara C. Owczarczak‐Garstecka, Katrina E. Holland, Robert M. Christley; questionnaire development: all authors; formal analysis: Sara C. Owczarczak‐Garstecka, Katrina E. Holland, Katharine L. Anderson, Robert M. Christley, Lauren Harris, Rebecca Mead, Lauren Samet; data curation: Rebecca Mead, Robert M. Christley; writing—original draft preparation, Sara C. Owczarczak‐Garstecka, Katrina E. Holland; writing—review and editing, all authors; visualisation, Sara C. Owczarczak‐Garstecka. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Dogs Trust Ethical Review Board (Reference Number: ERB036). Generation Pup has ethical approval from the University of Bristol Animal Welfare Ethical Research Board (UIN/18/052), the Social Science Ethical Review Board at the Royal Veterinary College (URN SR2017‐1116) and the Dogs Trust Ethical Review Board (ERB009).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank all respondents who took part in this study. We are grateful to Emma Buckland and Naomi Harvey for comments on the survey design. We would like to thank Andy Stanton for creating the online version of the Generation Pup survey and Adam Williams for his assistance with data extraction. We are grateful to the Dogs Trust Communications Team for assistance in promoting the survey.

Owczarczak‐Garstecka SC, Holland KE, Anderson KL, Casey RA, Christley RM, Harris L, et al. Accessing veterinary healthcare during the COVID‐19 pandemic: A mixed‐methods analysis of UK and Republic of Ireland dog owners’ concerns and experiences. Vet Rec. 2022;e1681. 10.1002/vetr.1681

Sara C. Owczarczak‐Garstecka and Katrina E. Holland should be considered joint first authors.

Contributor Information

Sara C. Owczarczak‐Garstecka, Email: sara.owczarczak-garstecka@dogstrust.org.uk.

Katrina E. Holland, Email: katrina.holland@dogstrust.org.uk.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors. The data are not publicly available due to ethical approval of participant informed consent that included survey respondents being informed that we would remove all personally identifiable information before sharing data with universities and/or research institutions.

REFERENCES

- 1. British Veterinary Association . Guidance for veterinary practices in assessing emergency and urgent care during the COVID‐19 pandemic. https://www.bva.co.uk/coronavirus/coronavirus-advice-for-veterinary-professionals/ (2020). Accessed 13 April 2022.

- 2. British Veterinary Association . Updated guidance for UK veterinary practices on working safely during COVID‐19. https://www.bva.co.uk/media/3500/bva‐updated‐guidance‐for‐veterinary‐practices‐on‐working‐safely‐during‐covid‐19‐final‐28‐may‐2020.pdf (2020). Accessed 28 May 2020.

- 3. Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons . Coronavirus: economic impact on veterinary practice. https://www.rcvs.org.uk/news‐and‐views/publications/coronavirus‐economic‐impact‐on‐veterinary‐practice/ (2020). Accessed 3–7 Apr 2020.

- 4. Small Animal Veterinary Surveillance Network . Impact of COVID‐19 on companion animal veterinary practice (Report 1, 20 April 2020). https://www.liverpool.ac.uk/savsnet/covid‐19‐veterinary‐practice‐uk/? (2020). Accessed 20 Apr 2020.

- 5. Robinson D, Vanderleyden J. RCVS COVID‐19 survey 2020. Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons. https://www.rcvs.org.uk/news‐and‐views/publications/rcvs‐covid‐19‐survey‐2020/ (2020). Accessed 01 Sept 2020.

- 6. Pegasus . Pet Owner Survey‐United Kingdom findings. https://www.healthforanimals.org/resources/newsletter/articles/survey‐of‐pet‐owners‐shows‐impacts‐of‐covid‐19‐pandemic‐on‐veterinary‐care/ (2020) Accessed 13 April 2022.

- 7. Small Animal Veterinary Surveillance Network . Impact of COVID‐19 on companion animal veterinary practice (Report 3, 5 June 2020). https://www.liverpool.ac.uk/savsnet/covid‐19‐veterinary‐practice‐uk/ (2020). Accessed 16 Dec 2020.

- 8. Hughes HE, Hughes TC, Morbey R, Challen K, Oliver I, Smith GE, et al. Emergency department use during COVID‐19 as described by syndromic surveillance. Emerg Med J. 2020;37(10):600–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wiltzius AJ, Blackwell MJ, Krebsbach SB, Daugherty L, Kreisler R, Forsgren B, et al. Access to veterinary care: barriers, current practices, and public policy. https://trace.tennessee.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1016&context=utk_smalpubs (2018). Accessed 16 Dec 2020.

- 10. Wu H, Bains RS, Morris A, Morales C. Affordability, feasibility, and accessibility: companion animal guardians with (Dis) Abilities’ access to veterinary medical and behavioral services during COVID‐19. Animals. 2021;11(8):2359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. British Veterinary Association . Coronavirus frequently asked questions. https://www.bva.co.uk/coronavirus/frequentlyasked‐questions/ (2020). Accessed 16 Dec 2020.

- 12. Coe J, Adams C, Eva K, Desmarais S, Bonnett B. Development and validation of an instrument for measuring appointment‐specific client satisfaction in companion‐animal practice. Prev Vet Med. 2010;93(2–3):201–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kogan LR, Erdman P, Bussolari C, Currin‐McCulloch J, Packman W. The initial months of COVID‐19: dog owners' veterinary‐related concerns. Front Vet Sci. 2021;8:629121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Michie S, Van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Murray JK, Kinsman RH, Lord MS, Da Costa REP, Woodward JL, Owczarczak‐Garstecka SC, et al. ‘Generation Pup’–protocol for a longitudinal study of dog behaviour and health. BMC Vet Res. 2021;17(1):1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Christley RM, Murray JK, Anderson KL, Buckland EL, Casey RA, Harvey ND, et al. Impact of the first COVID‐19 lockdown on management of pet dogs in the UK. Animals. 2021;11(1):5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Holland KE, Owczarczak‐Garstecka SC, Anderson KL, Casey RA, Christley RM, Harris L, et al. “More attention than usual”: a thematic analysis of dog ownership experiences in the UK during the first COVID‐19 lockdown. Animals. 2021;11(1):240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL, Gutmann ML, Hanson WE. Advanced mixed methods research designs. In: Tashakkori A, Teddlie C, editors. Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research. California, USA: Sage; 2003. p. 209–40. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Carter N, Bryant‐Lukosius D, DiCenso A, Blythe J, Neville AJ, editors. The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2014;41(5):545–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Team RC. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Braun V, Clarke V. What can “thematic analysis” offer health and wellbeing researchers? Int J Qual Stud Health Well‐Being. 2014;16(9):26152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shoesmith E, Shahab L, Kale D, Mills DS, Reeve C, Toner P, et al. The influence of human–animal interactions on mental and physical health during the first COVID‐19 lockdown phase in the U.K.: a qualitative exploration. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(3):976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bowen J, García E, Darder P, Argüelles J, Fatjó J. The effects of the Spanish COVID‐19 lockdown on people, their pets, and the human‐animal bond. J Vet Behav. 2020;40:75–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bussolari C, Currin‐McCulloch J, Packman W, Kogan L, Erdman P. “I couldn't have asked for a better quarantine partner!”: experiences with companion dogs during COVID‐19. Animals. 2021;11(2):330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Belshaw Z, Robinson NJ, Dean RS, Brennan ML. “I always feel like I have to rush…” pet owner and small animal veterinary surgeons’ reflections on time during preventative healthcare consultations in the United Kingdom. Vet Sci. 2018;5(1):20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ford RB, Larson LJ, McClure KD, Schultz RD, Welborn LV. AAHA canine vaccination guidelines. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2017;53(5):243–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Puurunen J, Hakanen E, Salonen MK, Mikkola S, Sulkama S, Araujo C, et al. Inadequate socialisation, inactivity, and urban living environment are associated with social fearfulness in pet dogs. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):3527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. González‐Martínez A, Martínez MF, Rosado B, Luño I, Santamarina G, Suárez ML, et al. Association between puppy classes and adulthood behavior of the dog. J Vet Behav. 2019, 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dickinson GE, Roof PD, Roof KW. A survey of veterinarians in the US: euthanasia and other end‐of‐life issues. Anthrozoös. 2011;24(2):167–74. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Adrian JAL, Stitt A. There for you: attending pet euthanasia and whether this relates to complicated grief and post‐traumatic stress disorder. Anthrozoös. 2019;32(5):701–13. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hobson‐West P, Jutel A. Animals, veterinarians and the sociology of diagnosis. Sociol Health Illn. 2020;42(2):393‐406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bard AM, Main DC, Haase AM, Whay HR, Roe EJ, Reyher KK. The future of veterinary communication: Partnership or persuasion? A qualitative investigation of veterinary communication in the pursuit of client behaviour change. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0171380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Quain A, Mullan S, McGreevy PD, Ward MP. Frequency, stressfulness and type of ethically challenging situations encountered by veterinary team members during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Front Vet Sci. 2021;8:647108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Diverio S, Boccini B, Menchetti L, Bennett PC. The Italian perception of the ideal companion dog. J Vet Behav. 2016;12:27–35. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors. The data are not publicly available due to ethical approval of participant informed consent that included survey respondents being informed that we would remove all personally identifiable information before sharing data with universities and/or research institutions.