Abstract

This study tested an ecological model of resilience that illustrated the influence of COVID‐19‐related stressors (i.e., social and health stressors) and various socio‐ecological factors at microsystem (i.e., parent–child conflicts and couple relationship) and exo‐system levels (i.e., the utilization of community resources) on family functioning among Chinese families during COVID‐19. An anonymous telephone survey was conducted using random sampling method. The sample contained 322 respondents who were co‐habiting with their child(ren) and their partner. Hierarchical regression analysis and structural equation modelling were used to examine the differential impacts of various levels of factors and the model that were proposed. Results showed that 13.2% of the households were categorized as at‐risk of poorer family functioning. Couple relationship and stressors significantly accounted for much of the variance in family functioning. While stressors had a significant direct effect on family functioning, couple relationship, but not parent–child conflicts or utilization of community resources, significantly mediated and moderated the impact of stressors on family functioning. The findings highlighted the impacts of both individual and ecological factors on family functioning under COVID‐19. Importantly, cultural and contextual factors should be considered when adopting ecological model of resilience to examine family functioning in diverse cultural groups.

Keywords: Chinese families, couple relationship, COVID‐19, family functioning, parent–child relationship

1. INTRODUCTION

Since 2019, the coronavirus epidemic has brought unprecedented changes globally at the individual, family, societal and national levels. This public health crisis has also influenced family processes and interactions between family members (Hervalejo et al., 2020). First, the outbreak has led to economic decline in many countries resulting from disrupted business activities and lockdown of non‐essential businesses (Nelson et al., 2020), which in turn has contributed to economic strain for the general population. According to Banovcinova et al. (2014), poverty can disrupt family functioning because chronic economic stress often leads to frequent adoption of coercive and punitive parenting styles by parents, which may induce parent–child relationship problems (Prime et al., 2020). Second, the interruption of normal daily routines and temporary closure of some health care facilities can exacerbate physical and mental health problems which may affect quality of life (Zhang & Ma, 2020), especially among those family members who have chronic physical and mental problems. On the other hand, such worsening of mental and physical health conditions may result in elevated level of demands in caregiving, thus creating strains on family caregivers (Patterson & Garwick, 1994). Third, domestic violence and intimate partner violence can affect family functioning (Heru et al., 2007). Indeed, during COVID‐19, there has been increasing incidents of household violence being reported (Campbell, 2020). Lastly, addictive behaviours and substance use addiction (Dubey et al., 2020) have both been reported to surge since the outbreak of COVID‐19. Dubey et al. (2020) maintains that people engage in addictive behaviours to cope with the stressful feelings stemming from psychosocial stressors such as prolonged home confinement and the fear of contracting infection and of losing jobs.

In Hong Kong, government statistics show that the unemployment rate of 6.2% was the highest for 15 years (Census and Statistics Department, 2020). Additionally, Hong Kong residents with pre‐existing adverse health conditions suffered greatly from the disruption to daily life, with co‐occurring anxiety and depression (Lau et al., 2020). In addition, the admission of women to domestic abuse shelters increased 1.7 times over a year (Sun, 2020). Indeed, a study conducted in Hong Kong among vulnerable families also reported that many families encountered an increasing level of family stress such as mental health problems, chronic health problems and financial burden since the start of COVID‐19 (Zhuang et al., 2021).

Studies on how COVID‐19 impacts on family functioning have generated inconsistent results with some concluding deterioration (Feinberg et al., 2021; Hussong et al., 2020) and others reporting well functioning (Fernandes et al., 2020; López et al., 2020). Among Chinese populations, studies on family process during COVID‐19 are limited. The few available studies suggest that living with family and good family functioning acted as protective factors against mental health problems among medical staff and vocational school students (e.g., Pan et al., 2021). However, literature abounds to suggest that cultural values and beliefs shape how people, including families, respond to life adversities (Xie & Wong, 2021). In Chinese culture, positive family relationships and interpersonal harmony are regarded as essential characteristics of a happy family (Shek, 2002). In times of difficulties, individuals in a family, particularly parental couples in a household, usually shoulder a strong sense of responsibilities to protect the wellbeing not just for oneself but for the rest of the families. Incidentally, Chinese people may rely more on their families rather than community support when tackling daily hassles (Chen et al., 2016), and financial and unemployment issues (Lin et al., 2016). A study conducted in Hong Kong found no association between community support and family adaptation (Lin et al., 2016). This may be related to the Chinese cultural values of self‐reliance and insider/outsider differentiation (Yi & Ellis, 2000).

On the whole, the above literature review has produced equivocal findings regarding the impact of COVID‐19 on family functioning. How does one family adapt well in a crisis and another family suffers? What are the critical family factors that expose a family to or protect it from potential detrimental effects of a crisis, like the COVID‐19 pandemic? Does culture play a part in it?

2. THE CONCEPT OF FAMILY FUNCTIONING

Family functioning has been advocated as a useful index of family well‐being and family quality of life. Family functioning refers to ‘how the families satisfy their physical and psychological needs in order to maintain the family and to survive as a group’ (Georgas, 2003, p.4). Result‐oriented and process‐oriented approaches offer two approaches to conceptualizing family functioning (Dai & Wang, 2015). Result‐oriented approaches categorize families into different types. For example, Olson's Annular Mode model classifies families into adaptable, disengaged, separated, connected and enmeshed families (Olson, 2000). On the other hand, process‐oriented approaches focus on tasks that the family needs to complete. For example, the McMaster Family Functioning model highlights six tasks for successful functioning: problem‐solving, communication, role, affective responsiveness, affective involvement and behaviour control (Miller et al., 2000). In this study, since our primary aim was to examine how COVID‐19 related life stressors might influence the family process and dynamics, we chose the McMaster Process Model of Family Functioning because it is one of the most popular and frequently used model for examining the processes and outcomes in family functioning.

3. CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK OF THE ECOLOGICAL MODEL OF RESILIENCE AND ITS IMPACT ON FAMILY FUNCTIONING

Resilience is defined as a dynamic process whereby individuals bounce back despite adversities or traumas (Luthar et al., 2000). However, some scholars have proposed examining personal adaptation to adversity from a family resilience perspective because family dynamics can greatly determine individual behaviours and the ultimate adaptation of the individual and their family. The concept of family resilience highlights the risk and protective factors in the family and emphasizes the identification of effective response patterns and universal elements that facilitate a family's adaption in times of crisis (Walsh, 2016). Interestingly, despite the possible influence of family dynamics on individual resilience, most studies on resilience factors have focused on individual psychological characteristics, such as intelligence, impulse control and positive self‐concept (Meisels & Shonkoff, 2000). Such heavy emphasis on intrapersonal factors, as some scholars assert, ignores the influence of ecological and systemic factors influencing a person's resilience (Waller, 2001). Indeed, they counter‐suggest that maintaining resilience during adversity largely depends on environmental rather than individual factors and on the resources that are available and accessible to nurture and sustain the individual concerned (Ungar et al., 2013). This argument echoes the current view of an ecological perspective on family resilience, which suggests that family risk and resilience are the results of the interplay among various factors including social, psychological, economic, biological and historic factors which are played out at individual, interpersonal, family and ecosystem levels (Henry et al., 2015).

In this study, we adopted an ecological model of resilience in exploring family functioning of Chinese families under the impact of COVID‐19. This model comprised six subsystems nested within each other that include the biopsychological system, microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem and chronosystem (Bronfenbrenner & Ceci, 1994). In this study, we were particularly interested in examining the effects of certain factors at the microsystem level (i.e., parent–child conflicts and couple relationship); and the utilization of community resources at the exosystem level on family functioning under the impact of the COVID‐19‐related stressors.

3.1. Microsystem level factors affecting family functioning

At the microsystem level, the quality of family relationships plays an important role in enhancing family members' resilience. In the face of adversities, the family unit can potentially provide resources such as guidance, reassurance, attachment and integration through sharing common beliefs and providing relational and structural support (Walsh, 2016). On the other hand, adverse family relationships, such as parent–child conflicts and couple relationship problems, can greatly affect family functioning (Lavee et al., 1987).

Parent–child conflicts are seen as risk factors for family functioning. Some research has revealed a negative correlation between parent–child relationships and family functioning, such as poor problem solving and communication skills, in families with Chinese adolescents having depressive disorders (Chen et al., 2017). Moreover, among Chinese parents and adolescents, some family relationship factors such as parenting stress (Ma et al., 2011), parent–child conflict and filial piety (Li et al., 2014) may be more predictive of family functioning than socio‐demographic characteristics. Besides a possible direct causal relationship, parent–adolescent conflicts may also serve as a mediator between stressors and family functioning (Li et al., 2018).

Couple relationships also have great relevance for family functioning. Conflictual and hostile couple relationships may risk poorer family functioning (Katz & Woodin, 2002), whereas good quality marital interaction facilitates family adjustment (Yates et al., 1995). Essentially, the parental couple is the central pillar in a family unit and support and affirmation between the parents are highly relevant to the well‐being of the family unit (Sprenkle & Olson, 1978). During COVID‐19, there is potentially a greater chance of marital dispute and dissatisfaction due to financial hardship, unemployment and parent–child conflicts during confinement, which, in turn, may compromise the adaptive family functioning. Interestingly, although some research reveals deteriorating couple relationships (e.g., hostility, withdrawal and less responsive support in some couples) during COVID‐19 (Pietromonaco & Overall, 2020), other studies suggest the relationships among some couples actually improved (Günther‐Bel et al., 2020). Due to these inconclusive findings, it would be interesting to explore how couple relationship function as either a moderator or mediator under the influence of COVID‐19 stressors in Hong Kong families.

3.2. Exosystem level factors affecting family functioning

The utilization of community resources, as indicated by accessing resources and support in the neighbourhood network, friends and public service agencies in the community, is considered important exosystem factors contributing to individual resilience and psychological wellbeing (Ungar et al., 2013). Walsh (2013) argues that community efforts involving local agencies and residents are essential to meeting the challenges of a major crisis and that mutual support and collective resources from the community are important agents in promoting family resilience (Walsh, 2013). For example, individuals with strong support from spouses and employers and a positive work–life balance during the pandemic have reported less marital and parental stress than those with lower levels of support and less work–life balance (Chung et al., 2020). A Taiwanese study suggested that community support might partially mediate the relationship between the build‐up of demands and family functioning among vulnerable families (Hsiao & Riper, 2009). However, the role of community resources in enhancing family functioning during the COVID‐19 pandemic has not been well studied. Despite that families are a primary unit that individuals can rely on, Chinese culture also value neighbourhood support in dealing with people's daily lives, as reflected in the Chinese saying, ‘A good neighbor outmatches a distant relative’. (Yuan & Ngai, 2012). Therefore, it is worth exploring how the utilization of community resources might protect family functioning in Hong Kong families during the COVID‐19 pandemic.

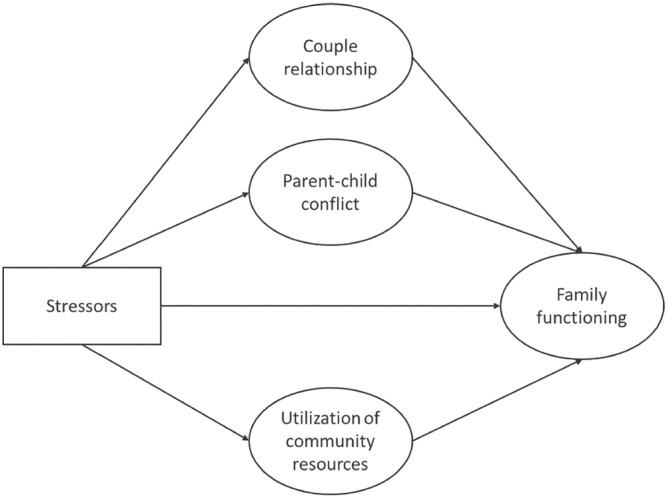

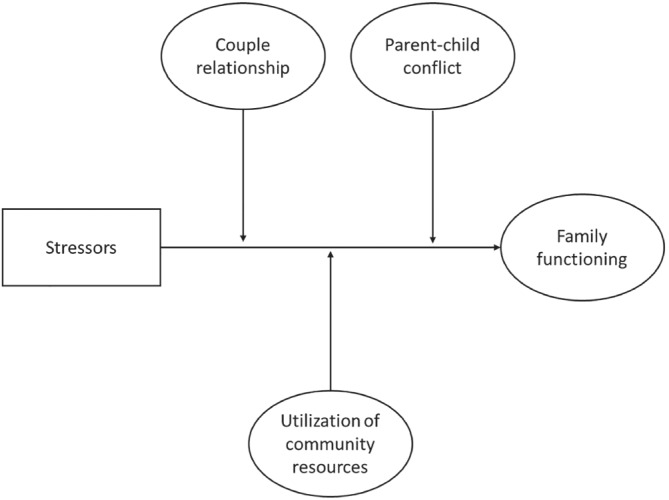

To conclude, Chinese families under the impact of COVID‐19 may be experiencing various levels of factors that were adversely affecting their family functioning. However, many of these factors have been researched separately in different studies; there has been no attempt to explore the differential impacts of these various factors on family functioning during the pandemic in a single study. In addition, there is no study that had explored and clarified the mediating and moderating roles of these ecological factors in the relationship between COVID‐19 stressors and family functioning. Using an ecological model of resilience (Ungar et al., 2013), the current study attempted to construct and test a model of family resilience that identifies the risk and protective factors influencing family functioning during the COVID‐19 pandemic and explored both the mediating and moderating effects of the ecological factors in response to COVID‐19‐related stressors (Figures 1 and 2). The findings would be of great interest to researchers and policy makers for developing strategies to enhance the resilience of families, especially during health crises such as COVID‐19.

FIGURE 1.

The conceptual diagram of tested mediated model of family functioning

FIGURE 2.

The conceptual diagram of tested moderated model of family functioning

4. RESEARCH GAPS

The preceding literature review has identified several research gaps about family functioning in Chinese families during COVID‐19. First, there is a lack of a holistic and systemic picture illustrating the multi‐level factors that influence family functioning in Chinese families. This study represents the first attempt to develop a systemic and ecological view of family resilience and explore the impacts of the various individual and family processes in influencing family functioning of Chinese families in Hong Kong. Second, the previously mentioned Chinese studies targeted specific populations, mainly young people, rather than the general population. The findings and implications of these previous studies may not be generalized to all age groups. Third, the potential risk and protective factors and their differential impacts in impeding or facilitating family adaptation to life challenges have not been examined. How families adjust and adapt to changes and adversity during COVID‐19 is an important area of research (Brock & Laifer, 2020), and we intend to use the Hong Kong Chinese families to illustrate this line of research.

5. OBJECTIVES AND HYPOTHESES

This study attempted to develop and test an ecological resilience model to illustrate how COVID‐19‐related stressors, and various factors at the microsystem and exosystem levels of a family influence family functioning. Below are the hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1

Social and health stressors stemmed from COVID‐19 pandemic including family members with chronic illness, physical and mental health problems, violence, addictive behaviours and financial problems would negatively impact perceived family functioning.Hypothesis 2a

Protective factors (couple relationship) and risk factors (parent–child conflict) from the microsystem would positively and negatively impact perceived family functioning respectively.Hypothesis 2b

Utilization of community resources as a protective exosystem factor would positively but less influential than intrafamilial factors in impacting perceived family functioning.Hypothesis 3a

Ecological factors (couple relationship, parent–child conflict and utilization of community resources) would mediate the negative effect of COVID‐19‐related stressors on perceived family functioning.Hypothesis 3b

Ecological factors (couple relationship, parent–child conflict and utilization of community resources) would moderate the negative effect of COVID‐19‐related stressors on perceived family functioning.

6. METHOD

6.1. Procedures and respondents

The survey was an anonymous telephone survey conducted using the Computer Assisted Telephone Interviews (CATI) method. The sample was drawn randomly from a list of telephone numbers based on a sampling frame generated from the Hong Kong residential directory. The telephone numbers on the final list were then randomized and selected as needed. This method provides an equal probability sample that covers unlisted and new numbers but excludes large businesses that used blocks of at least 10 numbers. For each successfully contacted residential unit with more than one eligible respondent present at the time of the telephone contact, the ‘Next Birthday’ rule was applied (i.e., household member whose birthday occurred next was selected).

The final list contained a sample frame of 22,751 telephone numbers. Respondent selection was based on the following criteria: (1) Chinese adult family member aged 18 or above; (2) able to understand Cantonese or Mandarin; and (3) permanent resident of Hong Kong. Nine thousand three hundred and nineteen did not answer the call; 4,764 were unavailable; 6,177 did not meet the eligibility criteria and the rest were business numbers (701), fax numbers (584), refusals (80) and partial responses (116). Of the 1010 respondents who completed the survey, those not living with family members, a spouse and child(ren)/parent(s) were excluded because our primary objective focused on understanding family functioning of respondents living together with their family. A final subsample of 322 respondents that included those co‐habiting with their child(ren) and their partner was extracted from this larger sample. The telephone interviews were conducted by 12 interviewers from the Social Sciences Research Centre (SSRC), an independent research centre of The University of Hong Kong between late June and late August 2020. Verbal consent was obtained from the respondents before data collection and the average interview time took 14.5 min. The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Hong Kong.

6.2. Measurements

Family Assessment Device (FAD; Epstein et al., 1983 ). The FAD is a 60‐item self‐report instrument that assesses family functioning. We used the short version of the General Functioning (GF‐6) subscale that contains six items on positive family functioning patterns to examine individuals' family functioning (Boterhoven de Haan et al., 2015) to reduce the burden on respondents in completing the full FAD on the telephone. Respondents answered on a 4‐point scale (1 = strongly agree; 4 = strongly disagree). The Chinese version of the FAD was translated and validated by Shek (2002). A higher FAD score indicates poorer family functioning and a cut‐off of 2 or above represents maladjusted family functioning (Boterhoven de Haan et al., 2015). The Cronbach's α of the FAD in this study was 0.90.

Chinese Family Resilience Assessment Scale (C‐FRAS; Li et al., 2016 ). We used the Utilizing Social Resources (USR) subscale of the C‐FRAS to measure the social resources used by a household. Three items, tapping on social resources from the community, neighbourhood and friends, were rated on a 4‐point scale (1 = strongly disagree; 4 = strongly agree). Items include ‘We ask neighbors for help and assistance’, ‘We feel people in this community are willing to help in an emergency’, ‘We know we are important to our friends’. The Cronbach's α of the subscale was 0.44 in our study.

Relationship Network Inventory—Relationship Quality Version (NIR‐RQV; Furman & Buhrmester, 1985). We adopted the Conflict Subscale of the NIR‐RQV to evaluate parent–child conflict for respondents living with a child (ren) or parent(s). The subscale comprises three items each of which is rated on a 5‐point Likert scale (1 = never; 5 = always). The items asked how often the respondent and their parents/children ‘argue with each other?’, ‘disagree and quarrel with each other?’, ‘get mad at or get in fights with each other?’. The Chinese version of the NIR‐RQV was translated and validated by Kong et al. (2012). In our study, Cronbach's α was 0.74.

The Dyadic Adjustment Scale‐7 (DAS‐7; Sharpley & Cross, 1982 ). We adopted the DAS‐7 to measure the couple relationship and adjustment. The DAS‐7 has three sub‐scales: dyadic consensus (three items), dyadic cohesion (three items) and global dyadic satisfaction (one item). The consensus and cohesion subscales are rated on a six‐point Likert‐type scales (with endpoints showing either ‘always agree’ and ‘always disagree’ or ‘all the time’ and ‘never’), and the satisfaction subscale is rated on a seven‐point scale (with endpoints of ‘extremely unhappy’ and ‘perfectly happy’). Sample items include ‘Please indicate the approximate extent of agreement or disagreement between you and your partner on philosophy of life.’ Previous studies have demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency of the DAS‐7 (α ranging from 0.78 to 0.80). The full version of the DAS was translated and validated among Chinese by Shek (1995). Our study reported Cronbach's α of 0.80.

Social and Health Statuses Scale. A self‐constructed Social and Health Statuses Scale containing six items was developed to collect information concerning psychosocial COVID‐19‐related stressors, such as financial problems, mental health problems, physical illness, chronic disease, family violence and behavioural problems such as addiction among respondents' family members. Participants responded with either ‘Yes’ or ‘No’, each positive response counting as one stressor. The number of stressors was the sum of the positive responses. Respondents were also asked to indicate if such problems had become better, worse, or remained the same since COVID‐19. Worsened condition was counted as aggravated status of stressors during COVID‐19.

Lastly, demographic variables including residential district, place of birth, the number of family members living together, the relationship with family members living together, monthly household income, respondent's gender, age, education level and employment status were collected.

6.3. Data analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS‐26. To utilize the available data, missing data were replaced by multiple imputations using SPSS. Five imputations were done in the current study. Multiple imputation addresses the uncertainty (e.g., underestimation of standard error) in the missing data, when compared with single imputation and it is more practical than the maximum likelihood estimation method (Sinharay et al., 2001). As this was a population study, weights were applied in the correlation and regression analyses. The weights are the ratios of the age and gender distribution of the population data to those of this sample. Population data were taken from the Census and Statistics Department for end‐2019 (Census and Statistics Department, 2021). First, frequencies and descriptive statistical analysis were conducted for demographic information and the major study variables. Second, a hierarchical regression analysis was utilized to examine the relative variances of the multi‐level factors in explaining family functioning. In the first model, demographic variables including gender, age, household monthly income, education level and employment status were entered. Previous studies suggested these individual factors had association with family functioning, and they were input in the first model as covariates. In the second model, the social and health statuses (i.e., various COVID‐19‐related stressors such as financial hardship and mental and physical health of other family members) were added to test how might these stressors predict one's perceived family functioning when demographics were controlled. Guided by the ecological system theory we have proposed earlier, we made the assumption that COVID‐19‐related stressors might first impact on the outer layer of the ecological environment (i.e., exosystem factors), and then on the inner layer microsystem factors (i.e., family subsystems), and in turn, these factors shaped the functioning of the families (Bronfenbrenner & Ceci, 1994; Prime et al., 2020). Therefore, exosystem level factors, namely, the utilization of community resources, were inputted in the third model and microsystem level factors (i.e., parent–child conflict and couple relationship) were added in the fourth and fifth models, respectively. R square change and its corresponding change in F value (∆F), which are of greatest statistic interest in hierarchical regression, were reported (Wampold & Freund, 1987).

Structural equation modelling (SEM) was conducted using Mplus 8 to assess the possible direct and indirect relationships in our proposed ecological resilience model (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Measured scores on family functioning, the number of stressors, utilization of social resources, parent–child conflict and couple relationship were assessed simultaneously. Socio‐demographic variables such as gender, age and SES indices (education, income level and employment status) were included as covariates. First, a mediation model was constructed for family functioning as the outcome variable, with the number of stressors as the predictor variable and utilization of social resources, parent–child conflict and couple relationship as the mediators (Figure 1). Bootstrapping to generate 5000 bootstrap samples from the original data was performed with bias‐corrected 95% confidence intervals (BC 95% CI). A mediating effect was evident from (1) a statistically significant indirect effect with p < 0.05 and (2) BC 95% CI did not include zero. Second, different moderation models were constructed for utilization of community resources, parent–child conflict and couple relationship in response to COVID‐19‐related stressors, separately. A significant improvement in model fit for the model with interaction terms (Model 1) when compared to a model with only main effects (Model 0) indicated a significant moderating effect (Maslowsky et al., 2015). We used RMSEA, CFI, TLI and SRMR to evaluate data‐model fit. The model was accepted if SRMR and RMSEA < 0.08 and other fit indices >0.90 (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

7. RESULTS

7.1. Descriptive and correlation analyses

As shown in Table 1, the age range of the 322 respondents was 20 to 90 years, with a mean age of 52.1 years. Nearly half were female (49.6%), about half (53.3%) had a full‐time job, and 18.3% were retired; most had completed secondary education (80.1%), and the sample households had various income levels. All respondents lived with their child (ren) and spouse; the rest lived with parent(s) (5.6%), grandchild (ren) (1.4%) or sibling(s) (0.2%).

TABLE 1.

Respondents demographic information: Descriptive Statistics (N = 322)

| Variables | N | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 160 | 49.6 |

| Male | 162 | 50.4 |

| Age | 20–90 | |

| Mean (SD) | 52.10 (11.85) | |

| Employment | ||

| Full time | 172 | 53.3 |

| Part time | 37 | 11.6 |

| Housekeeper | 47 | 14.7 |

| Unemployment | 7 | 2.1 |

| Retired | 59 | 18.3 |

| Family income (HK$) | ||

| Below 10,000 | 7 | 2.2 |

| 10,001–20,000 | 31 | 9.5 |

| 20,001–30,000 | 57 | 17.6 |

| 30,001–40,000 | 43 | 13.2 |

| 40,001–50,000 | 43 | 13.2 |

| 50,001 or above | 136 | 41.8 |

| No income | 5 | 1.4 |

| Education | ||

| Grade 6 or below | 19 | 8.8 |

| Grade 7 to grade 9 | 34 | 11.1 |

| Grade 10 to grade 12 | 111 | 35.2 |

| Hong Kong diploma of secondary education/advanced level qualification | 16 | 4.5 |

| Associate degree/diploma | 10 | 3.4 |

| Degree or above | 132 | 36.9 |

| Place of birth | ||

| Hong Kong | 251 | 78 |

| Mainland China | 64 | 19.8 |

| Others | 6 | 1.8 |

| Residence | ||

| Hong Kong Island | 62 | 19.1 |

| Kowloon | 91 | 28.3 |

| New territories | 169 | 52.3 |

| Family members living together | ||

| Children | 322 | 100 |

| Parents | 18 | 5.6 |

| Grandchildren | 4 | 1.4 |

| Grandparents | 0 | 0 |

| Spouse | 322 | 100 |

| Siblings | 1 | 0.2 |

Weighted means, standardized deviations and correlations of the studied variables are presented in Table 2. Maladaptive family functioning is indicated by a mean greater than 2; the weighted mean of the sample was 1.54, reflecting an average level of family functioning. Remarkably, 13.2% of households were categorized as at risk of maladjusted family functioning.

TABLE 2.

Stressors, family functioning, risk and protective factors: Correlations and descriptive Statistics (N = 322)

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Stressors | 0.71 | 0.93 | — | |||

| 2. Family functioning | 1.54 | 0.55 | 0.279** | — | ||

| 3. Couple relationship | 22.75 | 6.15 | −0.174** | −0.473** | — | |

| 4. Parent–child conflict | 6.92 | 2.33 | 0.147** | 0.046 | 0.048 | — |

| 5. Utilization of community resources | 8.24 | 1.43 | −0.182** | −0.119* | 0.161** | −0.072 |

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

Table 3 identifies the impact of COVID‐19 on family members' health, highlighting four major stressors. These include family member(s) who had mental/emotional problems (21.4%); chronic diseases (17.5%), addiction problems (13.8%) and financial problems (10.8%). Respondents also reported whether the stressors had become more aggravated during the pandemic. 21.9%, 20.8%, 10%, 5.2% and 2.3% of respondents revealed more aggravated mental/emotional problems, financial problems, addiction problems, physical ill‐health and chronic disease respectively.

TABLE 3.

Stressors experienced by respondents (N = 322)

| Stressors | Respondents reported stressors | Respondents reported aggravated status during COVID‐19 |

|---|---|---|

| Physical ill health | 6.5% | 5.2% |

| Chronic diseases | 17.5% | 2.3% |

| Mental/emotional problems | 21.4% | 21.9% |

| Violence at home | 0.6% | 0.3% |

| Addiction | 13.8% | 10.0% |

| Financial | 10.8% | 20.8% |

7.2. Hierarchical regression analysis

The results of the weighted hierarchical regression are reported in Table 4. Most of the demographic variables (age and gender employment) did not significantly explain much variance in family functioning, except that family income was found to positively predict family dysfunction. COVID‐19‐related stressors were found to significantly predict a higher level of family dysfunction (6.8% variance explained). Meanwhile, utilization of community resources (1%) and couple relationship (17%) significantly accounted for the variance in family functioning in these families. Finally, parent–child conflict was not found to exert significant influences on family functioning. To conclude, COVID‐19‐related stressors and couple relationship in the micro‐system had much greater influence than utilization of social resources in the exosystem on family functioning of Chinese families.

TABLE 4.

Hierarchical regression analysis for risk and protective factors predicting family functioning (N = 322)

| Predictors | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | −0.060 | −0.043 | −0.047 | −0.057 | −0.059 |

| Age | 0.080 | 0.094 | 0.092 | 0.102 | 0.074 |

| Income | 0.073 | 0.102 | 0.116* | 0.120* | 0.156** |

| Education | −0.121* | −0.098 | −0.110* | −0.118* | −0.049 |

| Employment | −0.096 | −0.066 | −0.070 | −0.070 | −0.043 |

| Stressors | 0.266*** | 0.250*** | 0.241*** | 0.195*** | |

| Community resources | −0.088* | −0.086 | −0.026 | ||

| Parent–child conflict | 0.056 | 0.070 | |||

| Couple relationship | −0.442*** | ||||

| R square | 0.040 | 0.107 | 0.115 | 0.118 | 0.289 |

| R square change | 0.040 | 0.068 | 0.007 | 0.003 | 0.172 |

| F change | 2.63* | 23.85*** | 2.61* | 0.978 | 75.41*** |

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

7.3. SEM analysis

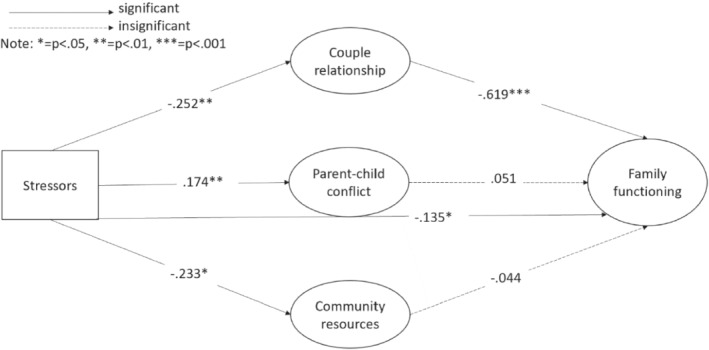

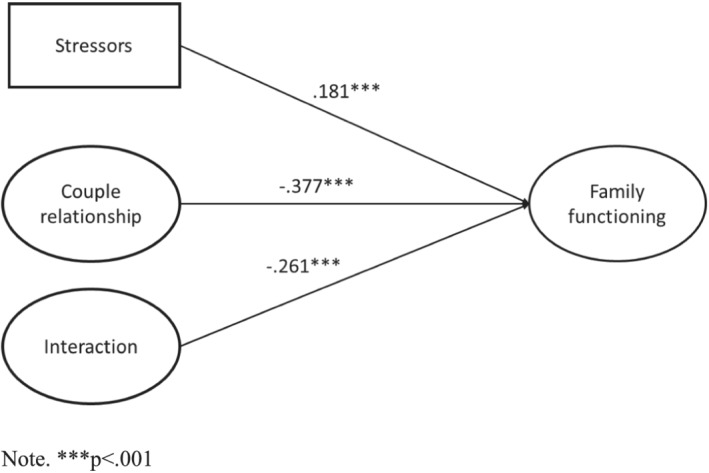

First, the SEM mediation model demonstrated good data‐model fit (χ 2 = 333.642, df = 166, p = 0.000): CFI = 0.911; TLI = 0.90; SRMR = 0.073; RMSEA = 0.056 (BC 95% CI = [0.047, 0.064]) (Figure 3). Stressors had a significant direct effect on family functioning (β = 0.135, p = 0.027), supporting Hypothesis 1. Couple relationship (β = −0.619, p = 0.000), but not parent–child conflicts (β = 0.051, p = 0.394) or utilization of community resources (β = −0.044, p = 0.587), had a significant direct impact on family functioning, partially supporting Hypothesis 2a but not Hypothesis 2b. A significant mediating role was only found for couple relationship (b = 0.156, 95%CI = [0.064, 0.248], p = 0.005), modulating the impact of stressors on family functioning. Second, SEM moderation models supported a protective buffering effect of couple relationship between stressors and effective family functioning. The main effect model (Model 0) of couple relationship demonstrated good fit indices (χ 2 = 166.609, df = 72, p = 0.000): CFI = 0.929; TLI = 0.911; SRMR = 0.081; RMSEA = 0.063 (BC 95% CI = [0.051, 0.076]). The model with interaction term (Model1) showed significantly more fit based on the log likelihood ratio test of model comparison, which supported the moderating effect of couple relationship (Figure 4). Conditional effect tests showed that when couple relationship was not satisfactory, the effect of stressors on family functioning was significant (β = 0.193 p = 0.000). However, for those who had a better couple relationship, stressors did not predict increasing levels of family dysfunction (β = −0.035, p = 0.297). Thus, Hypothesis 3a and 3b were both partially supported. To conclude, a good and healthy couple relationship may mediate the deleterious effects of stressors on family functioning of Chinese families in Hong Kong and a good couple relationship could also buffer the negative influence of COVID‐19 stressors on family functioning at the same time.

FIGURE 3.

Mediated structural equation model for family functioning (N = 322)

FIGURE 4.

Moderated structural equation model for family functioning (N = 322)

8. DISCUSSION

Enhancing resilience in families is an important policy and intervention strategy for policy‐makers and practitioners globally, especially during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Using an ecological resilience model, this study examined the relative importance of selected risk and protective factors in a family's individual, microsystem and exosystem that might impact the family functioning of Chinese families in Hong Kong. It also attempted to test a specific family resilience model that might potentially affect family functioning in these families. Our findings suggest that 13.2% of the families were at risk of poor family functioning during COVID‐19. This result is comparable to research in Western countries in which moderate family dysfunction was observed in 15.2% of Portuguese families (Fernandes et al., 2020). However, the average FAD score in our survey (weighted mean = 1.54) was lower than those of Ma et al.'s studies in Hong Kong (2009, 2011). With a mean of 2 or above signifying poorer family functioning, it appears that Hong Kong families may be adapting adequately to meeting the challenges posed by the pandemic. This finding is not at all surprising because of Hong Kong peoples' previous experiences of a similar crisis with the SARS epidemic of 2003. This might have prepared them psychologically to cope better with a public health crisis and demonstrate awareness in maintaining family and individual health under stressful events.

8.1. Demographic and COVID‐19‐related stressors influencing family functioning

In this study, demographic factors such as gender, age and education did not exert much impact on the family functioning of Chinese families in Hong Kong. However, to our surprise, family income was found to be positively associated with family dysfunction. This result alerts us to pay particular attention to middle‐class families who may be relatively more hard‐hit by economic strains under COVID‐19. It is because despite the fact that many people from different social stratifications are affected by the unemployment and underemployment, people of middle‐class status may not be well protected under social security system in many countries, such as those in Hong Kong which received little subsidies from the government to maintain their normal income and livelihood (The Hong Kong Council of Social Service (HKCSS), 2020). Indeed, reports have pointed out that middle‐class families in Hong Kong are most burdened by housing costs (Chen, 2013), and thus, economic strains during COVID‐19 may be more stressful for this group of families. These rising economic strains may affect the family functioning, intensifying the conflicts between couples and between other family members.

Our analysis suggests that the social and health statuses of individual members as ‘stressors’ exerted significant direct and indirect impacts on poorer family functioning. Respondents rated the presence of a family member with a mental health problem as the most significant stressor during COVID‐19. More than one‐fifth of respondents reported that the mental health problems of their family member (21.0%) had become much more elevated during COVID‐19. This result, coincidentally, matched similar results in other COVID‐19 studies in Hong Kong (Lau et al., 2020; Zhuang et al., 2021). Policy measures such as self‐isolation, quarantine and social‐distancing measures undoubtedly resulted in financial downturns, and unemployment. In turn, these led to the escalation of mental health problems during the pandemic. In the literature, many studies have found that the presence of a member with mental illness can create considerable stress for other family members, and can lead to adverse family relationships, including breakdown (Butterworth & Rodgers, 2008). This specific finding points towards possible increased attention and intervention to support this group of vulnerable families in times of crisis.

8.2. Microsystem level factors influencing family functioning

Couple relationship had the strongest direct effect on family functioning. Moreover, a good couple relationship was also found to mediate and moderate the negative effects of life stressors on family functioning, indicating the importance of couple relationship as a cornerstone in maintaining families' stability and well‐being. Essentially, a good couple relationship characterized by a higher sense of dyadic consensus, cohesion and satisfaction can enhance family problem solving and harmony and foster the provision of practical and emotional support to other family members.

COVID‐19 has obviously imposed challenges and strains on couple relationships. Social distancing and home confinement measures give Chinese couples and their children in Hong Kong who usually live in a tiny space no choice but to be in constant close and frequent contact with each other. Such arrangements were already sufficient to create or intensify family conflicts. However, if a couple can maintain a degree of openness to reach a consensus when resolving difficulties, and jointly participate in activities, these would greatly enhance mutual support, positive expression of feelings, better problem solving among family members. Given our findings that couple relationship is highly significant in influencing family functioning in Chinese families in Hong Kong, it is paramount to provide support to strengthen the couple subsystem to enable them to maintain mutual support and problem‐solving capabilities among family members.

Contrary to our hypothesis, our study did not yield strong evidence to support a significant direct or indirect linkage between parent–child conflict as a risk factor and family functioning. This may be related to the characteristics of our sample that comprised mainly middle‐ to older‐aged parents (e.g., 85% of the respondents aged above 40) with adult children. From a developmental perspective, conflicts tend to become less intense when the child reaches adulthood and parent–child relationships are characterized by mutual understanding and respect, negotiations, interdependence, or even distancing (Rossi & Rossi, 1990). In our sample, parents aged above 40 (M = 6.71, SD = 2.71) scored significantly lower parent–child conflict level than parents aged under 40 (M = 8.09, SD = 2.20) (t[320] = 3.882, p = 0.000). Thus, it is understandable to find a lack of influence of parent–child conflicts on family functioning among this group of Chinese families in Hong Kong. It would be interesting to observe if parent–child conflicts would be a significant predictor of family functioning among families with younger children.

8.3. Exosystem level factors influencing family functioning

The role of community network and resources appears to have less influence than the couple relationship in the microsystem and stressors in the individual system on family functioning of families in this study. To explain these findings, the specific circumstances of COVID‐19 may have contributed to reducing the impact of exosystem level factors on family functioning. Social distancing measures resulted in many community and social services running at limited capacity and neighbours and friends cannot provide immediate support to the household. On the other hand, a Chinese family may rely much more on close family members within their own household or immediate family to provide emotional and practical support for each other. Indeed, given the insider/outsider differentiation (Yi & Ellis, 2000), it is not uncommon for Chinese families to seek help from close family members for social and instrumental support rather than external resources and support for dealing with difficulties and crises in a family. As one study suggests, support within one's own family, but not outside instrumental support, was associated positively with family functioning in Chinese families with members with a chronic illness (Jiang et al., 2015).

In the final analysis, our study supports an ecological model of family resilience, highlighting the impact of the ecological and systemic factors that influence family functioning. However, our findings do not fully concur with Ungar et al.'s (2013, p.350) assertion that ‘… in adversity (e.g. exposure to violence, poverty, disability) the more the child's resilience depends on the quality of the environment (rather than individual qualities) and the resources that are available and accessible to nurture and sustain well‐being’. Our findings suggest that individual‐level factors (i.e., perceived stressors faced by family members), contextual factors (i.e., COVID‐19 conditions) and possible cultural factors (e.g., insider‐outsider differentiation) might have greater influences than external environmental resources in impacting family functioning among Chinese families in Hong Kong. Indeed, it is necessary to include an analysis of ‘cultural and contextual factors’ when using the ecological model of family resilience to understand multi‐level factors influencing different cultural groups in a society. As Ungar et al. (2013, p. 350) admitted, ‘in studies of homogeneous populations exposed to high levels of adversity, the ethnocentricism of the researcher may unintentionally result in factors associated with resilience that are contextually and culturally embedded being overlooked’.

9. LIMITATIONS

First, the study sample was mainly comprised of middle to older aged parents (89.9% of the respondents aged above 40 and mean age is 52). This limits the generalizability of the results to families with younger children and families comprising older adults. Future research should focus on these two target groups to identify factors affecting their family functioning. Second, this study examined familial and communal factors only. Future research should examine the influence of other factors in the microsystem, mesosystem and exosystem, such as work environments and peer networks. Third, the reliability score for ‘utilization of community resources’ was relatively low, thus the results must be read with caution. This may be because that there are only three items in this scale and cover three different contexts (i.e., community, friends and neighbourhood) (Li et al., 2016). However, as Schmitt (1996) has argued, there is no golden standard on the acceptable or unacceptable level of Cronbach's α, and low reliability may not impede its use if the scale contains desirable characteristics, such as meaningful content coverage (Schmitt, 1996). Future studies may include the measure of other aspects of community resources such as informal and formal social support and community services to examine how exosystem factors can influence family functioning under the impact of COVID‐19 epidemic. Fourth, this study was a cross‐sectional study and causal effects among the variables cannot be determined. Moreover, the present study adopted a random household telephone sampling method, future studies may adopt a dual frame sampling strategy that include both household telephone numbers as well as the mobile telephones so that more younger residents can be included. Lastly, the data were collected based on the report from a single family member in a family. Multiple informant data collection method may be employed in the future to attenuate single report bias.

10. IMPLICATIONS AND CONCLUSION

This study adopted an ecological model of family resilience to conceptualize risk and protective factors influencing family functioning and acknowledged the importance of incorporating familial and communal factors affecting family functioning. This enriches our understanding of family resilience by positing the functioning of the individual household into nested systems. Our research findings reveal that microsystem factors (i.e., satisfaction in the couple relationship) might have exerted a greater impact than exosystem level factors (utilization of community resources) on family functioning. This ecological perspective on family resilience can be used to examine the differential and interaction effects of different levels of factors influencing family functioning in future studies; however, it is necessary to incorporate cultural and contextual factors into research on family resilience.

From a practice perspective, at the prevention level, social workers can develop a family functioning assessment tool to identify vulnerable families facing different stressors so that early and timely intervention can be provided to families in need. Our study also found that couple relationship is an important protective factor in family functioning. Social workers can develop prevention and intervention programs to address couple relationship issues such as dyadic cohesion, consensus and satisfaction will hopefully lead to greater satisfaction in the couple relationship which would enhance overall family functioning in Chinese families. In addition, social workers of the community‐based family services such as the Integrated Family Service Centres (IFSCs) in Hong Kong can provide family counselling, parent–child and couple relationship enhancement activities, and outreaching services for families under COVID‐19 context. Indeed, there is a need to creatively use internet‐ or digital‐ based technology to reach out to families in Hong Kong and elsewhere. In Hong Kong, projects that have been funded by the Hong Kong Jockey Club such as SMART Family‐Link Project and Family Emotional Resilience Project have developed websites, mobile phone apps and interactive video games for local social workers to use these to provide online services for families in need. Training and supervision are also provided for social workers to learn to use these online and digital resources to enhance family members' effective communication, emotional regulation and connectedness.

From a policy perspective, the government can take the lead to develop policies to promote family resilience. Such ideas are being advocated and implemented in some OECD countries (OECD, 2019). In addition, as Ungar et al. (2013) have suggested, recognition of the influence of the wider environment should inform the development of social policy to make resources available and accessible to people in need. Specifically, as our research has indicated, there is a need to dedicate funding to social service organizations to develop family resilience and couple relationship programs to strengthen the family functioning of Chinese families in Hong Kong.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

We have no known conflicts of interests to disclose.

Wong, D. F. K. , Lau, Y. Y. , Chan, H. S. , & Zhuang, X. (2022). Family functioning under COVID‐19: An ecological perspective of family resilience of Hong Kong Chinese families. Child & Family Social Work, 1–13. 10.1111/cfs.12934

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data can be accessed per request.

REFERENCES

- Banovcinova, A. , Levicka, J. , & Veres, M. (2014). The impact of poverty on the family system functioning. Procedia‐Social and Behavioral Sciences, 132, 148–153. 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.04.291 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boterhoven de Haan, K. L. , Hafekost, J. , Lawrence, D. , Sawyer, M. G. , & Zubrick, S. R. (2015). Reliability and validity of a short version of the general functioning subscale of the McMaster family assessment device. Family Process, 54(1), 116–123. 10.1111/famp.12113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brock, R. L. , & Laifer, L. M. (2020). Family science in the context of the COVID‐19 pandemic: Solutions and new directions. Family Process, 59(3), 1007–1017. 10.1111/famp.12582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. , & Ceci, S. J. (1994). Nature‐nuture reconceptualized in developmental perspective: A bioecological model. Psychological Review, 101(4), 568–586. 10.1037/0033-295X.101.4.568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterworth, P. , & Rodgers, B. (2008). Mental health problems and marital disruption: Is it the combination of husbands and wives' mental health problems that predicts later divorce? Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 43(9), 758–763. 10.1007/s00127-008-0366-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, A. M. (2020). An increasing risk of family violence during the Covid‐19 pandemic: Strengthening community collaborations to save lives. Forensic Science International: Reports, 2, 100089. 10.1016/j.fsir.2020.100089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Census and Statistics Department, HKSAR . (2020). Unemployment and underemployment statistics for August—October 2020. Retrieved from https://www.censtatd.gov.hk/press_release/4701

- Census and Statistics Department, HKSAR . (2021). Table 1A: Population by sex and age group. Retrieved from https://www.censtatd.gov.hk/en/web_table.html?id=1A

- Chen, A. (2013). Hong Kong's middle class most burdened by high housing costs. South China Morning Post. Available at https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/article/1295325/middle-class-most-burdened-high-housing-costs

- Chen, Q. , Du, W. , Gao, Y. , Ma, C. , Ban, C. , & Meng, F. (2017). Analysis of family functioning and parent‐child relationship between adolescents with depression and their parents. Shanghai Archives of Psychiatry, 29(6), 365–372. 10.11919/j.issn.1002-0829.217067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. Y. , Wong, G. H. , Lum, T. Y. , Lou, V. W. , Ho, A. H. , Luo, H. , & Tong, T. L. (2016). Neighborhood support network, perceived proximity to community facilities and depressive symptoms among low socioeconomic status Chinese elders. Aging & Mental Health, 20(4), 423–431. 10.1080/13607863.2015.1018867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung, G. , Chan, X. , Lanier, P. , & Ju, P. W. Y. (2020). Associations between workfamily balance, parenting stress, and marital conflicts during COVID‐19 pandemic in Singapore. OSF Preprints. 10.31219/osf.io/nz9s8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dai, L. , & Wang, L. (2015). Review of family functioning. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 03(12), 134–141. 10.4236/jss.2015.312014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey, M. J. , Ghosh, R. , Chatterjee, S. , Biswas, P. , Chatterjee, S. , & Dubey, S. (2020). COVID‐19 and addiction. Diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research and Reviews, 14(5), 817–823. 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, N. B. , Baldwin, L. M. , & Bishop, D. S. (1983). The McMaster family assessment device. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 9(2), 171–180. 10.1111/j.1752-0606.1983.tb01497.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg, M. E. , A Mogle, J. , Lee, J. , Tornello, S. L. , Hostetler, M. L. , Cifelli, J. A. , Bai, S. , & Hotez, E. (2021). Impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on parent, child, and family functioning. Family Process, 61, 361–374. 10.1111/famp.12649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, C. S. , Magalhães, B. , Silva, S. , & Edra, B. (2020). Perception of family functionality during social confinement by coronavirus disease 2019. Journal of Nursing and Health., 10, e20104034. [Google Scholar]

- Furman, W. , & Buhrmester, D. (1985). Children's perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Developmental Psychology, 21(6), 1016–1024. 10.1037/0012-1649.21.6.1016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Georgas, J. (2003). Family: Variations and changes across cultures. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 6(3). 10.9707/2307-0919.1061 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Günther‐Bel, C. , Vilaregut, A. , Carratala, E. , Torras‐Garat, S. , & Pérez‐Testor, C. (2020). A mixed‐method study of individual, couple, and parental functioning during the state‐regulated COVID‐19 lockdown in Spain. Family Process, 59(3), 1060–1079. 10.1111/famp.12585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry, C. S. , Sheffield Morris, A. , & Harrist, A. W. (2015). Family resilience: Moving into the third wave. Family Relations, 64(1), 22–43. 10.1111/fare.12106 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heru, A. M. , Stuart, G. L. , & Recupero, P. R. (2007). Family functioning in suicidal inpatients with intimate partner violence. Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 9(6), 413–418. 10.4088/pcc.v09n0602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hervalejo, D. , Carcedo, R. J. , & Fernández‐Rouco, N. (2020). Family and mental health during the confinement due to the COVID‐19 pandemic in Spain: The perspective of the counselors participating in psychological helpline services. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 51(3–4), 399–416. 10.3138/jcfs.51.3-4.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao, C. Y. , & Riper, M. V. (2009). Individual and family adaptation in Taiwanese families of individuals with severe and persistent mental illness (SPMI). Research in Nursing & Health, 32(3), 307–320. 10.1002/nur.20322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L. , & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong, A. , Midgette, A. , Richards, A. , Petrie, R. , Coffman, J. , & Thomas, T. (2020). COVID‐19 life events spill‐over on family functioning and adolescent adjustment. Research Square. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-90361/v1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H. , Wang, L. , Zhang, Q. , Liu, D. X. , Ding, J. , Lei, Z. , Lu, Q. , & Pan, F. (2015). Family functioning, marital satisfaction and social support in hemodialysis patients and their spouses. Stress and Health, 31(2), 166–174. 10.1002/smi.2541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz, L. F. , & Woodin, E. M. (2002). Hostility, hostile detachment, and conflict engagement in marriages: Effects on child and family functioning. Child Development, 73(2), 636–652. 10.1111/1467-8624.00428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong, Z. , Cao, F. L. , Cui, N. X. , Li, Y. , Chen, Q. Q. , & Liu, J. J. (2012). Reliability and validity of the network of relationship inventory‐relationship quality version in Chinese teacher‐student relationship. Chinese Journal of Child Health Care, 3, 221. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, B. H. , Chan, C. L. , & Ng, S. M. (2020). Resilience of Hong Kong people in the COVID‐19 pandemic: Lessons learned from a survey at the peak of the pandemic in spring 2020. Asia Pacific Journal of Social Work and Development, 31(1–2), 105–114. 10.1080/02185385.2020.1778516 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lavee, Y. , McCubbin, H. I. , & Olson, D. H. (1987). The effect of stressful life events and transitions on family functioning and well‐being. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 49(4), 857–873. 10.2307/351979 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li, L. , Bai, L. , Zhang, X. , & Chen, Y. (2018). Family functioning during adolescence: The roles of paternal and maternal emotion dysregulation and parent–adolescent relationships. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(4), 1311–1323. 10.1007/s10826-017-0968-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. , Zou, H. , Liu, Y. , & Zhou, Q. (2014). The relationships of family socioeconomic status, parent–adolescent conflict, and filial piety to adolescents family functioning in mainland China. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23(1), 29–38. 10.1007/s10826-012-9683-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. , Zhao, Y. , Zhang, J. , Lou, F. , & Cao, F. (2016). Psychometric properties of the shortened Chinese version of the family resilience assessment scale. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(9), 2710–2717. 10.1007/s10826-016-0432-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, M. , Lo, L. Y. , Lui, P. Y. , & Wong, Y. K. (2016). The relationship between family resilience and family crisis: An empirical study of Chinese families using family adjustment and adaptation response model with the family strength index. Journal of Family Psychotherapy, 27(3), 200–214. 10.1080/08975353.2016.1199770 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- López, J. , Perez‐Rojo, G. , Noriega, C. , Carretero, I. , Velasco, C. , Martinez‐Huertas, J. A. , López‐Frutos, P. , & Galarraga, L. (2020). Psychological well‐being among older adults during the COVID‐19 outbreak: A comparative study of the young–old and the old–old adults. International Psychogeriatrics, 32(11), 1365–1370. 10.1017/S1041610220000964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar, S. S. , Cicchetti, D. , & Becker, B. (2000). The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development, 71(3), 543–562. 10.1111/1467-8624.00164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J. L. , Wong, T. K. , Lau, L. K. , & Pun, S. H. (2009). Perceived family functioning and family resources of Hong Kong families: Implications for social work practice. Journal of Family Social Work, 12(3), 244–263. 10.1080/10522150903030147 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J. L. , Wong, T. K. , Lau, Y. K. , & Lai, L. L. (2011). Parenting stress and perceived family functioning of Chinese parents in Hong Kong: Implications for social work practice. Asian Social Work and Policy Review, 5(3), 160–180. 10.1111/j.1753-1411.2011.00056.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maslowsky, J. , Jager, J. , & Hemken, D. (2015). Estimating and interpreting latent variable interactions: A tutorial for applying the latent moderated structural equations method. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 39(1), 87–96. 10.1177/0165025414552301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisels, S. J. , & Shonkoff, J. P. (2000). Early childhood intervention: A continuing evolution. In Meisels S. J. & Shonkoff J. P. (Eds.), Handbook of early childhood intervention (1st ed.) (pp. 3–31). Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/CBO9780511529320.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, I. W. , Ryan, C. E. , Keitner, G. I. , Bishop, D. S. , & Epstein, N. B. (2000). The McMaster approach to families: Theory, assessment, treatment and research. Journal of Family Therapy, 22(2), 168–189. 10.1111/1467-6427.00145 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, B. W. , Pettitt, A. , Flannery, J. E. , & Allen, N. B. (2020). Rapid assessment of psychological and epidemiological correlates of COVID‐19 concern, financial strain, and health‐related behavior change in a large online sample. PLoS ONE, 15(11), e0241990. 10.1371/journal.pone.0241990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OECD . (2019). Changing the odds for vulnerable children: Building opportunities and resilience. OECD Publishing. Retrieved from 10.1787/a2e8796c-en [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olson, D. H. (2000). Circumplex model of marital and family systems. Journal of Family Therapy, 22(2), 144–167. 10.1111/1467-6427.00144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y. , Yang, Z. , Han, X. , & Qi, S. (2021). Family functioning and mental health among secondary vocational students during the COVID‐19 epidemic: A moderated mediation model. Personality and Individual Differences, 171, 110490. 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, J. M. , & Garwick, A. W. (1994). The impact of chronic illness on families: A family systems perspective. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 16(2), 131–142. [Google Scholar]

- Pietromonaco, P. R. , & Overall, N. C. (2020). Applying relationship science to evaluate how the COVID‐19 pandemic may impact couples relationships. The American Psychologist, 76, 438–450. 10.1037/amp0000714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prime, H. , Wade, M. , & Browne, D. T. (2020). Risk and resilience in family well‐being during the COVID‐19 pandemic. American Psychologist, 75(5), 631–643. 10.1037/amp0000660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, A. S. , & Rossi, P. P. H. (1990). Of human bonding: Parent child relations across the life course. Transaction Publishers. 10.4324/9781351328920 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, N. (1996). Uses and abuses of coefficient alpha. Psychological Assessment, 8(4), 350–353. 10.1037/1040-3590.8.4.350 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpley, C. F. , & Cross, D. G. (1982). A psychometric evaluation of the Spanier dyadic adjustment scale. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 44, 739–741. 10.2307/351594 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shek, D. T. (1995). The Chinese version of the dyadic adjustment scale: Does language make a difference? Journal of Clinical Psychology, 51(6), 802–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shek, D. T. (2002). Assessment of family functioning in Chinese adolescents: The Chinese family assessment instrument. International Perspectives on Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 2, 297–316. 10.1016/S1874-5911(02)80013-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sinharay, S., Stern, H. S., & Russell, D. (2001). The use of multiple imputation for the analysis of missing data. Psychological methods, 6(4), 317–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprenkle, D. H. , & Olson, D. H. (1978). Circumplex model of marital systems: An empirical study of clinic and non‐clinic couples. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 4(2), 59–74. 10.1111/j.1752-0606 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, F. (2020). Stuck at home with a monster: More reports of violence against women, children in Hong Kong since start of pandemic. South China Morning Post.

- The Hong Kong Council of Social Service (HKCSS) . (2020). Unemployment and underemployment among Hong Kong families under COVID‐19. Retrieved from https://www.hkcss.org.hk/

- Ungar, M. , Ghazinour, M. , & Richter, J. (2013). Annual research review: What is resilience within the social ecology of human development? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54(4), 348–366. 10.1111/jcpp.12025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller, M. A. (2001). Resilience in ecosystemic context: Evolution of the concept. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 71(3), 290–297. 10.1037/0002-9432.71.3.290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, F. (2013). Community‐based practice applications of a family resilience framework. In Handbook of family resilience (pp. 65–82). Springer. 10.1007/978-1-4614-3917-2_5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, F. (2016). Family resilience: A developmental systems framework. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 13(3), 313–324. 10.1080/17405629.2016.1154035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wampold, B. E. , & Freund, R. D. (1987). Use of multiple regression in counseling psychology research: A flexible data‐analytic strategy. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 34, 372–382. 10.1037/0022-0167.34.4.372 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Q. , & Wong, D. F. K. (2021). Culturally sensitive conceptualization of resilience: A multidimensional model of Chinese resilience. Transcultural Psychiatry, 58(3), 323–334. 10.1177/1363461520951306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates, B. C. , Bensley, L. S. , Lalonde, B. , Lewis, F. M. , & Woods, N. F. (1995). The impact of marital status and quality on family functioning in maternal chronic illness. Health Care for Women International, 16(5), 437–449. 10.1080/07399339509516197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi, L. M. , & Ellis, P. (2000). Insider‐outsider perspectives of Guanxi. Business Horizons, 43(1), 25–30. 10.1016/S0007-6813(00)87384-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, R. , & Ngai, S. S. Y. (2012). Social exclusion and neighborhood support: A case study of empty‐nest elderly in urban Shanghai. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 55(7), 587–608. 10.1080/01634372.2012.676613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. , & Ma, Z. F. (2020). Impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on mental health and quality of life among local residents in Liaoning Province, China: A cross‐sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(7), 2381. 10.3390/ijerph17072381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, X. , Lau, Y. Y. , Chan, W. M. H. , Lee, B. S. C. , & Wong, D. F. K. (2021). Risk and resilience of vulnerable families in Hong Kong under the impact of COVID‐19: An ecological resilience perspective. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 56(12), 2311–2322. 10.1007/s00127-021-02117-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be accessed per request.