Abstract

The pandemic of COVID‐19 caused worldwide concern. Due to the lack of appropriate medications and the inefficiency of commercially available vaccines, lots of efforts are being made to develop de novo therapeutic modalities. Besides this, the possibility of several genetic mutations in the viral genome has led to the generation of resistant strains such as Omicron against neutralizing antibodies and vaccines, leading to worsening public health status. Exosomes (Exo), nanosized vesicles, possess several therapeutic properties that participate in intercellular communication. The discovery and application of Exo in regenerative medicine have paved the way for the alleviation of several pathologies. These nanosized particles act as natural bioshuttles and transfer several biomolecules and anti‐inflammatory cytokines. To date, several approaches are available for the administration of Exo into the targeted site inside the body, although the establishment of standard administration routes remains unclear. As severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 primarily affects the respiratory system, we here tried to highlight the transplantation of Exo in the alleviation of COVID‐19 pathologies.

Keywords: COVID‐19, exosomes, paracrine interaction, regenerative potential, stem cell, therapeutic effects

Significance statement

Exosomes (Exo) are nanosized vesicles that are released from each cell type and can transfer therapeutic molecules to the injured sites. It has been shown that Exo therapy circumvents difficulties that are associated with whole cell‐based therapies. Due to recent advances in the field of Exo‐based therapies, the current review article highlighted recent data and the applicability of Exo during viral diseases such as COVID‐19. The mechanism action and superiority of Exo were also debated in detail.

1. BACKGROUND

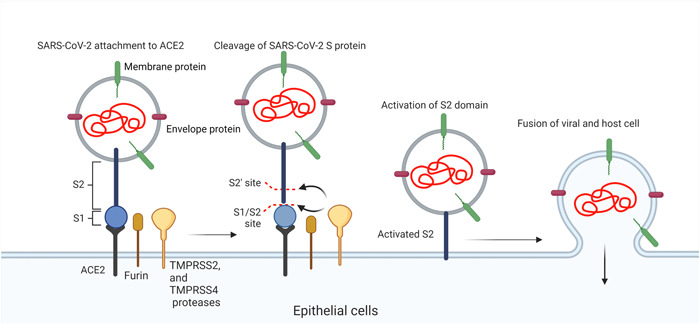

The emergence and prevalence of the COVID‐19 pandemic have challenged the healthcare community and led to serious socioeconomic impacts. 1 , 2 The cause of COVID‐19 is a virus from the Coronaviridae family namely severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2). 3 , 4 This virus harbors a single‐stranded positive‐sense RNA enclosed by nucleocapsid. An envelope with three structural proteins including membrane, spike (S), and envelope surrounds the nucleocapsid (Figure 1). 5 Of note, the attachment and viral entry into the target cells is done via a close interaction between S proteins with cell membrane‐bound angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). From molecular structure, S protein has two distinct regions S1 and S2. To maintain the physical connection between SARS‐CoV‐2 and epithelial cells, subunit S1 is activated in the early steps of infections. In later phases, the subunit S2 promotes the fusion of SARS‐CoV‐2 with the plasma membrane (Figure 1). 5 The interaction between S subunits and ACE2 leads to trihomodimerization which, in turn, provides mechanical force to push the virus forward into the cytosol. 5 It is thought that the occurrence of several mutations in the genomic structure of SARS‐CoV‐2 has changed the transmissibility and pathogenicity of the virus after nearly 3 years. From a molecular structure, the recently diagnosed variant Omicron (B.1.1.529) exhibits three deletions and one insertion mutation in S protein in comparison with the original SARS‐CoV‐2, leading to inefficiency of local and systemic neutralizing antibodies against Omicron S protein after vaccination or infection. 6 , 7 Along with changes, the fusogenic activity of Omicron S protein is enhanced because of mutation in the vicinity of the furin cleavage site, leading to the prominent tropism toward epithelium in the upper respiratory tract. 7 , 8 In support of this notion, the mutated S protein of Omicron has enhanced affinity to ACE2 compared to alpha and delta variants, leading to an accelerated viral entry to nasal epithelial cells. 9 Recent data revealed the existence of an alternative Omicron entry into the target cells using ubiquitous endosomal pathways independent of transmembrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2) protease. 9 Compared to other SARS‐CoV‐2 variants, Omicron can enter the host cells via TMPRSS2‐dependent and independent manners.

FIGURE 1.

Mechanisms of SARS‐CoV‐2 entry into target cells. Using spike proteins (S1 and S2), this virus can fuse with the host cell membrane and inject genomic materials. ACE2, angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2; SARS‐CoV‐2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; TMPRSS2 and 4, transmembrane serine protease 2 and 4.

To date, numerous therapeutic approaches have been used in COVID‐19 patients to diminish the mortality rate. 3 , 10 For example, the application of vaccines and transplantation of serum from infected individuals seems to be somewhat effective in the prevention of COVID‐19. 11 It seems that local or systemic application of commercially available neutralizing antibodies cannot be an effective strategy to prevent breakthrough infections. Direct application of antibodies is difficult and effective just a few days after the onset of clinical manifestation. 12 Of note, based on recently conducted investigations, most of the clinically used monoclonal antibodies are inactive against Omicron. 7 Even though, the existence of several variants during the COVID‐19 pandemic can contribute to the prevention of several variants of SARS‐CoV‐2 with conserved S protein except for Omicron. Recent data have indicated the efficiency of whole mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) therapy and their exosome (Exo) alone or in combination with other therapeutic approaches in the alleviation of COVID‐19‐related pathologies. 13 Here, we aimed to highlight the benefits associated with the application of Exo under the infection with SARS‐CoV‐2.

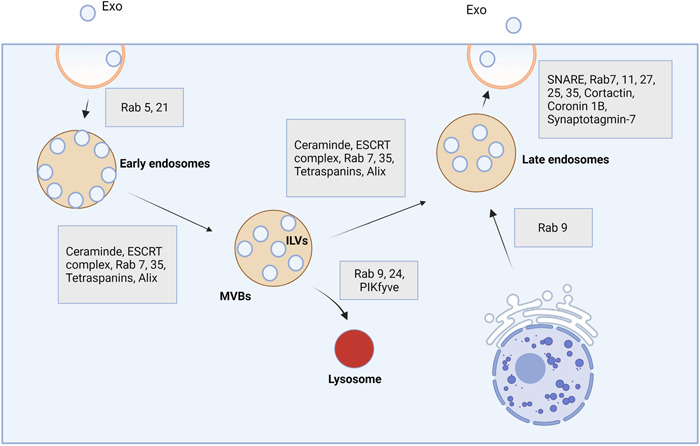

Exo are extracellular vesicles (EVs) subset and secreted by almost all cell types under physiological and pathological conditions. 14 These nanosized particles, 40–150 nm, distribute in various biofluids and participate in intercellular communication. Regarding transport activity, Exo transfer certain signaling biomolecules that may be involved in cellular hemostasis. 15 Besides garbage disposal activity, accumulating data have indicated that Exo possesses specific protein and genomic fingerprints and reflects the metabolic status of origin cells. 16 Exo are formed by the invagination of the membrane in early endosomes (Figure 2). In the next step, early endosomes generate multivesicular bodies (MVBs) where a lot of intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) are connected to the luminal surface of the lipid membrane. Later, MVBs and later endosomes are fused with the cell membrane and release ILVs into the extracellular matrix (ECM), hereafter known as Exo. 17 Molecular investigation have suggested the existence of complex biogenesis machinery for Exo production within the cytosol. 15 , 18 The process of Exo production inside the endosomal system can be done via endosomal sorting complexes required for transport machinery (ESCRT) or ESCRT‐free mechanisms. The ESCRT system is a distinct cascade composed of several signaling effectors. It has been elucidated that several membrane bonded proteins such as ESCRT‐0, I, II, III, Alix, and VPS4/VTA1 in collaboration with other factors such as flotillin, and TSG101 actively participate in the formation of ILVs in the lumen of MVBs (Figure 2). 19 In later phases, the close collaboration of other effectors such as SNARE and GTPase system leads to the fusion of later endosomes with the plasma membrane and release of ILVs into the ECM. 17

FIGURE 2.

Exo biogenesis machinery system. These particles are produced using the endosomal system and several effectors. After the formation of early endosomes, the invagination of the vesicle membrane can produce numerous intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) which are attached. Multivesicular bodies are directed toward lysosomal degradation or formed late endosomes which can fuse with the plasma membrane and release ILVS into the ECM. ILVs hereafter are known as Exo. ECM, extracellular matrix; ESCRT, endosomal sorting complexes required for transport machinery; Exo, exosomes; MVBs, multivesicular bodies.

Like other biological fluids, cumulative data have proved significant Exo levels in nasal discharge and airway mucus, indicating the putative key role of Exo in the pulmonary tract under physiological and pathological conditions. 20 Proteomic analysis of epithelium‐derived Exo has revealed the alteration in exosomal cargo after the onset of nasal polyp. 21

2. THERAPEUTIC EFFECTS OF EXO DURING INFECTION WITH SARS‐COV‐2

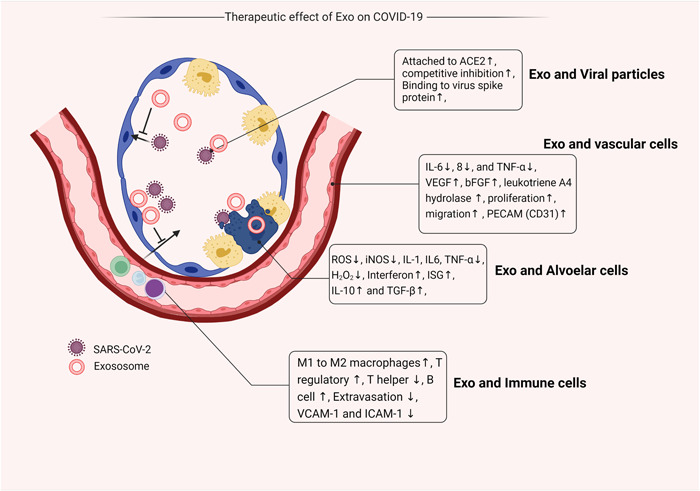

Exo are nanosized vesicles released by several cell types in response to stimuli under pathological and physiological conditions. 14 These particles can participate in intercellular paracrine activity via transferring several signaling biomolecules from donor to recipient cells. 15 Because of the existence of certain cargo types, Exo are potent enough to promote the regeneration of injured tissues, suppress the production of inflammatory cytokines, and modulate the activity of immune cells. 22 Considering their unique physicochemical properties and suitable biodistribution in biofluids, Exo can be applied locally and/or systemically after the onset of pathological conditions. In this regard, Exo has been used for different purposes like the natural delivery vehicle, detection of pathological‐associated biomarkers, and therapeutic purposes During the last decades. 23 , 24 It has been found that Exo can diminish cell death and apoptosis via engaging several mechanisms. For instance, MSCs Exo can prevent detrimental effects of oxidative stress in degenerating cells via the regulation of reactive oxygen production. 25 The production of several inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin‐1 (IL‐1) and IL‐6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)‐α in during COVID‐19 can trigger the mitochondrial injury via the production of hydrogen peroxide and inducible nitric oxide synthase. 26 Besides, nasal and pulmonary epithelium failed to produce and secret antiviral factors such as interferon at early stages after infection with SARS‐CoV‐2. 27 One reason would be that viral particles are recognized via the activation of Toll‐like receptors 3, 7, and cytoplasmic factors such as RIG‐I and MDA5, leading to activation of nuclear factor‐κB and production of types I and III interferons. 28 Exo can also increase antiviral responses in infected cells using several mechanisms. Transfer of interferon‐stimulated genes (ISGs) via Exo is touted as an effective way to increase the production and secretion of interferons. 29 A piece of evidence point to the fact that MSC‐Exo harbors notable contents of anti‐inflammatory cytokines such as IL‐10 and transforming growth factor‐β. These factors can reduce proinflammatory response and blunt uncontrolled immune cell recruitment into the pulmonary niche in response to local production of IL‐6, IL‐8, and TNF‐α coincided with the activity of leukotriene A4 hydrolase. 30 , 31 The secretion of certain growth factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor by MSC‐Exo can restore the function of the alveolar–blood barrier which can per se limit the extravasation of immune cells into the infected sites. 32 The activation of Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 in inflamed cells received MSCs‐Exo can lead to the stimulation of cell proliferation, migration, and suppression of apoptosis. Besides, this axis can promote the production of interferons during the infection of pulmonary epithelial cells with SARS‐CoV‐2. 33 The production of interferons in infected cells can stimulate the expression of ISGs in bystander cells in short and long distances, leading to relative immunity in recipient cells before the entry of the virus. 34 Shortly after the infection of epithelial cells in the pulmonary tract, superimposing and predominance of opportunistic bacteria can hamper immune cell response to a great extent. 35 Of note, postmortem biopsies from lungs infected with SARS‐CoV‐2 revealed the changes in the composition of bacteria and fungi. 36 In addition to the cytoprotective effects of Exo against viral infection, some experiments have shown considerable contents of antibacterial factors inside Exo. It is thought that Exo can exert antibacterial properties via inhibition of growth and promotion of phagocytosis by resident immune cells. 37 The secretion of several biomolecules, such as hepcidin, lipocalin 2, β‐defensin 2, and so forth, activates clearance mechanisms. In circumstances when MSCs are directly exposed to bacteria, they can regulate the dynamic growth of T lymphocytes, increase T‐regulatory cells, and trigger the phenotype shifting from M1 to M2 macrophages, leading to tissue regeneration and healing procedure (Figure 3). 38 , 39 Considering the unique microanatomical features of nasal capacity with low temperature (about 33°C), a large number of viral particles can be replicated and released into the surrounding niche soon after exposure to viral particles. In addition, these features make the nasal cavity vulnerable to both viral and bacterial infections in the early steps. 40 Therefore, it seems that the intranasal application of Exo in the early steps of COVID‐19 can reduce the replication of certain strains of SARS‐CoV‐2 and propagation into lower areas. Also, it should not be forgotten that SARS‐CoV‐2 infected epithelial cells per se produce Exo with certain proteomic signatures containing fibronectin, fibrinogen, P amyloid, and complement C1r subset which can be used as specific biomarkers for diagnosis and patients follow‐up. 41 In a recent experiment conducted by Barberis et al., 41 the interplay between the SARS‐CoV‐2 replication system and Exo biogenesis machinery was found, leading to the incorporation of viral genomic components into the Exo lumen and propagation infection to remote sites. Commensurate with these comments, one can hypothesize there is an apparent discrepancy, and the release of Exo from infected cells can lead to the rapid and progressive expansion of viral particles inside the body. The extension of SARS‐CoV‐2 to lower pulmonary sites such as lung parenchyma loosen the integrity of the alveolar‐blood barrier and diminishes gas exchanges, leading to hypoxic condition and high‐rate morbidity. To note, type II pneumocytes, and to less extent type I pneumocytes, are the main target cells infected by SARS‐CoV‐2 because of considerable contents of ACE2. 42 It is shown that pulmonary vascular endothelial cells are less prone to infect directly with SARS‐CoV‐2. However, cytokine storm and vigorous proinflammatory response make them vulnerable to pathological conditions. 43 Along with these changes, in situ production of several cytokines, promotes diffuse immune cell extravasation and significant serum protein infiltration into the alveolar space. 3 Vascular tissue injury predisposes COVID‐19 patients to the formation of thrombi. Rahbarghazi et al. successfully revealed the protective effects of bone MSCs Exo on pulmonary endothelial cells by reducing the expression of adhesion molecules such as vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 in the rat model of asthma. 44 Physiological significance of human umbilical cord MSCs Exo has been previously proved on angiogenesis potential of endothelial cells in a rat model of vessel grafting. It was suggested that intravenous administration of Exo can promote the endothelialization process via the increase of CD31+ cells on the luminal surface. The activation of certain signaling cascades such as phosphoinositide 3‐kinase/protein kinase B and mitogen‐activated protein kinase/extracellular signal‑regulated protein kinase 1/2 are critical in the angiogenesis potential of umbilical cord MSCs. 45 The precise cellular mechanisms that participate in the restoration of endothelial cell activity and vessel function are to determine in future studies. Whatever the reason, it seems the suppression of proinflammatory response and promotion of angiogenesis is the main underlying mechanisms involved in the restoration of vascular tissue function in COVID‐19 patients.

FIGURE 3.

Different therapeutic effects of Exo in pulmonary tissue infected with SARS‐CoV‐2. ACE2, angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2; bFGF, basic fibroblast growth factor; Exo, exosomes; ICAM‐1, intercellular adhesion molecule 1; IL‐6, interleukin‐6; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; ISG, interferon‐stimulated gene; PECAM, platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule;ROS, reactive oxygen species; SARS‐CoV‐2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; TGF‐β, transforming growth factor β; TNF‐α, tumor necrosis factor α; VCAM‐1, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

3. ENGINEERED EXO FOR THE INHIBITION OF VIRAL INFECTIONS

Transfer of certain viral components such as S protein can act as a natural vaccine and stimulate the production of neutralizing antibody titers. 46 , 47 It has been shown that viral protein materials such as S protein can be packed and transferred by Exo in patients with mild and severe COVID‐19. 47 These features can lead to proper activity of antigen‐presenting cells and T lymphocyte function. 47 In support of this data, the development of engineered Exo‐tagged with S protein increases the production of neutralizing antibodies in the mouse model. 46 , 48 Interestingly, El‐Shennawy et al. 48 showed the existence of circulating Exo with high levels of ACE2 in COVID‐19 patients which is closely associated with the severity of pathological conditions. In this scenario, these Exo possess a 135‐fold binding capacity in comparison with engineered Exo tagged with recombinant ACE to neutralize circulating SARS‐CoV‐2 before reaching the target sites. 48 Noteworthy, recent data have revealed the shared molecular mechanisms between the virus replication system and Exo biogenesis machinery. 49 It is thought that ligand–receptor interaction is the main mechanism involved in Exo and virus entry into cells. Therefore, the application of ACE2+ Exo isolated from COVID‐19 patients’ serum can be touted as competitive inhibition therapy in terms of viral particles using ACE for entry. 50 Scott et al. 51 designed anti‐CoV‐2‐enriched EVs tagged with CD63 which can efficiently bind to SARS‐CoV‐2 S protein. They claimed that this sophisticated system is eligible enough to prohibit the virus expansion in the early stages of infection. 51 In another experiment, engineered Exo with truncated CD9 and elevated ACE2 exhibited antiviral properties. These Exo successfully attached to viral S protein and inhibited the propagation of SARS‐CoV‐2 K18‐hACE2 mice. 52 The same strategy can be exploited to manipulate MSCs to produce secretomes with high contents of ACE2. 53 Recently, Zhang et al. 54 found structural differences between ACE2 released by EVs and exomeres (subpopulation of Exo below 50 nm) from colorectal cancer cell lines namely LIM1215 and DiFi. They showed that EVs possess full‐length glycosylated ectodomains of ACE2, while ectodomain fragments can be detected in exomeres. 54 Both short‐ and full‐length ACE2 can be recognized using neutralizing antibodies. Likewise, full‐length DPP4 ectodomain is sequestrated onto EVs while Exo is equipped with the ectodomain of this enzyme. 54 These data showed that both EVs and exomeres can efficiently bind to the S protein of SARS‐CoV‐2. Alternatively, it was suggested the secretome of MSCs overexpressing ACE2 can blunt detrimental effects of lipopolysaccharide in mammary epithelial cells via the regulation of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF‐α, IL‐Iβ, and IL‐6. 53 Results indicated that the promotion of inflammatory response in host cells can cause reduction of ACE2 presumably via an accelerated section of this factor. If so, ACE2‐tagged Exo can act as a natural decoy to trap and neutralize circulating SARS‐CoV‐2. 54 The story gets more complicated when we acknowledge that TMPRSS2, TMPRSS4, and TNF‐a converting enzyme is also secreted by EVs and exomeres. 54 Even though, the encapsulation of therapeutic agents and drugs into the Exo can also be touted as another modality to reduce or prohibit viral entry into the nasal or pulmonary tract epithelium. 55 Whether the existence of these factors can lead to viral particle priming and acceleration of infection is to be answered. Collectively, data indicate both stimulatory and inhibitory roles of Exo in the propagation of viral particles such as SARS‐CoV‐2. Whether and how Exo transfer SARS‐CoV‐2 from infected cells to bystander intact cells or exert blocking properties on circulating virus is the subject of area.

4. APPLICATION OF EXO IN VIRAL INFECTIONS

The intranasal administration of therapeutic agents is touted as a reliable delivery route during several pathological conditions. In this approach, the therapeutic agents and drug can directly enter the brain parenchyma and circumvent the blood–brain barrier while the most fractions of injected compounds are not eliminated via the gastrointestinal tract or hepatic system. 56 Interestingly, intranasal administration of Exo isolated from stem cells and other lineages is touted as a suitable noninvasive delivery route for the alleviation of pathologies within the pulmonary tract and central nervous system. 57 , 58 , 59 Unfortunately, the maximum fraction of Exo is eliminated a few hours after injection via intravenous route by trapping in the vascular bed of hepatic and pulmonary tissues. 57 Therefore, local administration of Exo into the nasal cavity during specific pathological conditions can provide sufficient Exo number to the site of injury. In terms of central nervous system disease, intranasal application of Exo is a promising therapeutic option to prohibit retrograde distribution of virus into the central nervous system and restore the function of the neurons a few days after administration. 60 Intranasal administration of Exo can lead to the reduction of repetitive behavior and improvement of mutual behavior in patients with an autism spectrum disorder. 22 Nasal cavity is the entry point of several air‐borne viruses such as SARS‐CoV‐2 and intranasal application of Exo in sensitive individuals exposed to this virus for a few hours could be an effective strategy to reduce the infection rate. 40 Along with intranasal injection of Exo, inhalation of Exo and/or stem cell secretome is an effective way to several types of lung injury and chronic pulmonary pathologies. 61 In an experiment, it was suggested that Exo inhalation reduces fibrosis in a mouse model by restoring alveolar function and structure via the reduction of type I collagen deposition and myofibroblast proliferation. 61 It is suggested that a runny nose and sore throat are the most clinical manifestation in Omicron patients. As a correlate, the application of Exo in Omicron patients seems easier and more effective because of local delivery of a low dose of Exo compared to the situation affecting lungs and bronchioles. Whether single or repeated doses of Exo are needed to alleviate Omicron‐associated injury is the subject of debate. Like many pathological conditions, therapeutic effects of Exo have been proved in patients with COVID‐19 in preclinical observations. 38 Regarding unique microanatomical properties, Exo application via intranasal dropping, and inhalation have been extensively considered in patients with lower and upper pulmonary tract inflammation. Based on an online survey related to the application of Exo in pulmonary disease recorded up to February 2022 (Table 1), Exo has been used as a biomarker, prophylactic (vaccination), and therapeutic agent for the alleviation of pulmonary disease and related cancers (available on https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=Pulmonary%2BDisease%26term=Exosomes%26cntry=%26state=%26city=%26dist=). It seems that the number of clinical trials targeting COVID‐19 patients increases by time.

TABLE 1.

List of Exo‐based clinical trials recorded up to February 2022

| Status | Study title | Conditions | Clinical phase |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recruiting | Omics sequencing of exosomes in body fluids of patients with acute lung injury | Acute lung injury | ND |

| Active, not recruiting | Early diagnosis of lung cancer using blood plasma‐derived exosome | Lung cancer | ND |

| Unknown | Combined diagnosis of CT scan and exosome in early lung cancer | Early lung cancer | ND |

| Recruiting | Molecular profiling of exosomes in the tumor‐draining vein of early‐staged lung cancer | Non‐small cell lung cancer | ND |

| Completed | Serum exosomal long noncoding RNAs as potential biomarkers for lung cancer diagnosis | Lung cancer | ND |

| Unknown | Clinical study of ctDNA and exosome combined detection to identify benign and malignant pulmonary nodules | Pulmonary nodules | ND |

| Completed | A pilot clinical study on inhalation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) exosomes treating severe novel coronavirus pneumonia | Coronavirus | I |

| Active, not recruiting | Randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of exosomes overexpressing cd24 to prevent clinical deterioration in patients with moderate or severe covid‐19 infection | COVID‐19 disease | II |

| Not yet recruiting | The use of exosomes for the treatment of acute respiratory distress syndrome or novel coronavirus pneumonia caused by covid‐19 | COVID‐19 disease | I and II |

| Recruiting | Efficacy and safety of exosome‐MSC therapy to reduce hyper‐inflammation in moderate covid‐19 patients | COVID‐19 disease | II and III |

| Recruiting | Immune modulation by MSCs‐derived exosomes in covid‐19 | COVID‐19 disease | ND |

| Recruiting | Circulating exosome RNA in lung metastases of primary high‐grade osteosarcoma | Lung metastases and osteosarcoma | ND |

| Recruiting | Evaluation of the safety of cd24‐exosomes in patients with covid‐19 infection | COVID‐19 | I |

| Active, not recruiting | Covid‐19 specific T cell‐derived Exo | COVID‐19 | I |

| Recruiting | A clinical study of MSC exosomes nebulizer for the treatment of acute respiratory distress syndrome | Acute respiratory distress syndrome | I and II |

| Enrolling by invitation | Safety and efficiency of the method of Exo inhalation in covid‐19 associated pneumonia | COVID‐19 | II |

| Completed | Evaluation of safety and efficiency of the method of exosome inhalation in SARS‑CoV‑2)‐associated pneumonia | COVID‐19 | I and II |

| Recruiting | Safety and efficacy of exosomes overexpressing cd24 in two doses for patients with moderate or severe covid‐19 | COVID‐19 | II |

| Not yet recruiting | Exosomes detection for the prediction of the efficacy and adverse reactions of anlotinib in patients with advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer | Non‐small cell lung cancer | ND |

| Completed | Trial of vaccination with tumor antigen‐loaded dendritic cell‐derived exosomes | Non‐small cell lung cancer | II |

| Completed | Extracellular vesicle infusion treatment for covid‐19 associated acute respiratory distress syndrome | COVID‐19 | II |

Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; ctDNA, circulating tumor DNA; Exo, exosomes; ND, nondetermined; SARS‑CoV‑2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Based on a great body of data, the application of crude or engineered Exo is an alternative approach to alleviate pathological changes along with conventional therapy following acute inflammatory response in the pulmonary niche. Although Exo administration is a noninvasive approach via different routes in specific types of COVID‐19 especially Omicron local delivery has superiority compared to systemic administration.

5. LIMITATIONS RELATED TO THE APPLICATION OF EXO IN THE CLINICAL SETTING

Although therapeutic intervention using Exo has led to splendid progress in the alleviation of several pathological conditions this era faces some limitation that needs further attention. 62 The lack of standard protocols and characterization systems can lead to the restricted application of Exo in in vivo conditions. 14 For example, it was shown that the morphology and integrity of Exo are changed using available purification methods. 14 In samples isolated by ultracentrifugation, contamination with serum proteins, lipoproteins, and other EVs is possible. 63 Besides, the metabolic status, culture system setting, route of injection, and proper Exo dosage are fundamental factors that can affect therapeutic efficiency. 64 Systemically administrated Exo, especially from allogeneic sources, are eliminated by the activity of splenic and hepatic macrophages, leading to a lack of appropriate Exo delivery to the target sites. 64 Sterility and the possibility of infectious agents such as viral particles and mycoplasma are other critical issues that must be carefully considered during the purification of Exo. 65

6. CONCLUSION

Administration of Exo from different cell sources, especially MSCs or development of engineered Exo has paved the way for efficient control of viral infection in the pulmonary tract. For better therapeutic outcomes, it is mandatory to redefine the dose and time of injection in the COVID‐19 patients. Despite numerous advantages associated with the Exo application, the unwanted side effects should be also considered in the context of COVID‐19.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Research reported in this publication was supported by Elite Researcher Grant Committee under award number (IR.NIMAD.REC.1397.512) from the National Institute for Medical Research Development (NIMAD), Tehran, Iran, and Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (IR.TBZMED.VCR.REC.1397.395), Tabriz, Iran.

Rezabakhsh A, Mahdipour M, Nourazarian A, et al. Application of exosomes for the alleviation of COVID‐19‐related pathologies. Cell Biochem Funct. 2022;40:430‐437. 10.1002/cbf.3720

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data generated or analyzed in the manuscript are included in this article.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bagheri HS, Karimipour M, Heidarzadeh M, Rajabi H, Sokullu E, Rahbarghazi R. Does the global outbreak of COVID‐19 or other viral diseases threaten the stem cell reservoir inside the body? Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2021;17:214‐230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Safari A, Lionetti V, Razeghian‐Jahromi I. Combination of mesenchymal stem cells and nicorandil: an emerging therapeutic challenge against COVID‐19 infection‐induced multiple organ dysfunction. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12:404. 10.1186/s13287-021-02482-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rezabakhsh A, Ala A, Khodaei SH. Novel coronavirus (COVID‐19): a new emerging pandemic threat. J Res Clin Med. 2020;8:5. [Google Scholar]

- 4. da Silva KN, Gobatto ALN, Costa‐Ferro ZSM, et al. Is there a place for mesenchymal stromal cell‐based therapies in the therapeutic armamentarium against COVID‐19? Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12:425. 10.1186/s13287-021-02502-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang M‐Y, Zhao R, Gao L‐J, Gao X‐F, Wang D‐P, Cao J‐M. SARS‐CoV‐2: structure, biology, and structure‐based therapeutics development. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10:587269. 10.3389/fcimb.2020.587269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shuai H, Chan JF‐W, Hu B, et al. Attenuated replication and pathogenicity of SARS‐CoV‐2B.1.1.529 Omicron. Nature. 2022;603:693‐699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Planas D, Saunders N, Maes P, et al. Considerable escape of SARS‐CoV‐2 Omicron to antibody neutralization. Nature 2021. 2022;602:671‐675. 10.1038/s41586-021-04389-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vihta K‐D, Pouwels KB, Peto TEA, et al. Omicron‐associated changes in SARS‐COV‐2 symptoms in the United Kingdom. medRxiv. 2022. 10.1101/2022.01.18.22269082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9. Peacock TP, Brown JC, Zhou J, et al. The SARS‐CoV‐2 variant, Omicron, shows rapid replication in human primary nasal epithelial cultures and efficiently uses the endosomal route of entry. BioRxiv. 2022.

- 10. Gurunathan S, Kang MH, Kim J‐H. Diverse effects of exosomes on COVID‐19: a perspective of progress from transmission to therapeutic developments. Front Immunol. 2021;12:716407. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.716407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Grein J, Ohmagari N, Shin D, et al. Compassionate use of remdesivir for patients with severe Covid‐19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2327‐2336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gottlieb RL, Nirula A, Chen P, et al. Effect of bamlanivimab as monotherapy or in combination with etesevimab on viral load in patients with mild to moderate COVID‐19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;325:632‐644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang SH, Shetty AK, Jin K, Chunhua Zhao R. Combating COVID‐19 with mesenchymal stem/stromal cell therapy: promise and challenges. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;8:627414. 10.3389/fcell.2020.627414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rezabakhsh A, Sokullu E, Rahbarghazi R. Applications, challenges and prospects of mesenchymal stem cell exosomes in regenerative medicine. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12:521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Heidarzadeh M, Gürsoy‐Özdemir Y, Kaya M, et al. Exosomal delivery of therapeutic modulators through the blood–brain barrier; promise and pitfalls. Cell Biosci. 2021;11:142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Elzanowska J, Semira C, Costa‐Silva B. DNA in extracellular vesicles: biological and clinical aspects. Mol Oncol. 2021;15:1701‐1714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gurunathan S, Kang M‐H, Kim J‐H. A comprehensive review on factors influences biogenesis, functions, therapeutic and clinical implications of exosomes. Int J Nanomed. 2021;16:1281‐1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gurung S, Perocheau D, Touramanidou L, Baruteau J. The exosome journey: from biogenesis to uptake and intracellular signalling. Cell Commun Signaling. 2021;19:47. 10.1186/s12964-021-00730-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wei D, Zhan W, Gao Y, et al. RAB31 marks and controls an ESCRT‐independent exosome pathway. Cell Res. 2021;31:157‐177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cha S, Seo E‐H, Lee SH, et al. MicroRNA expression in extracellular vesicles from nasal lavage fluid in chronic rhinosinusitis. Biomedicines. 2021;9:471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhou M, Tan KS, Guan W‐j, et al. Proteomics profiling of epithelium‐derived exosomes from nasal polyps revealed signaling functions affecting cellular proliferation. Respir Med. 2020;162:105871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Perets N, Hertz S, London M, Offen D. Intranasal administration of exosomes derived from mesenchymal stem cells ameliorates autistic‐like behaviors of BTBR mice. Mol Autism. 2018;9:57. 10.1186/s13229-018-0240-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kučuk N, Primožič M, Knez Ž, Leitgeb M. Exosomes engineering and their roles as therapy delivery tools, therapeutic targets, and biomarkers. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:9543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shokrollahi E, Nourazarian A, Rahbarghazi R, et al. Treatment of human neuroblastoma cell line SH‐SY5Y with HSP27 siRNA tagged‐exosomes decreased differentiation rate into mature neurons. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:21005‐21013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Xia C, Dai Z, Jin Y, Chen P. Emerging antioxidant paradigm of mesenchymal stem cell‐derived exosome therapy. Front Endocrinol. 2021;12:727272. 10.3389/fendo.2021.727272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zangeneh Z, Andalib A, Khamisipour G, Saadabadimotlagh H, Zangeneh S, Motamed N. TNF‐α, iNOS augmentation due to macrophages and neutrophils activity in samples from patients in intensive care unit with COVID‐19 infection. Int J Med Lab. 2021;8:247‐255. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pizzorno A, Padey B, Julien T, et al. Characterization and treatment of SARS‐CoV‐2 in nasal and bronchial human airway epithelia. Cell Rep Med. 2020;1:100059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Han L, Zhuang MW, Deng J, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 ORF9b antagonizes type I and III interferons by targeting multiple components of the RIG‐I/MDA‐5–MAVS, TLR3–TRIF, and cGAS–STING signaling pathways. J Med Virol. 2021;93:5376‐5389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yao Z, Jia X, Megger DA, et al. Label‐free proteomic analysis of exosomes secreted from THP‐1‐derived macrophages treated with IFN‐α identifies antiviral proteins enriched in exosomes. J Proteome Res. 2018;18:855‐864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mohanty A, Polisetti N, Vemuganti GK. Immunomodulatory properties of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. J Biosci. 2020;45:98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wang J, Huang R, Xu Q, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell‐derived extracellular vesicles alleviate acute lung injury via transfer of miR‐27a‐3p. Crit Care Med. 2020;48:e599‐e610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tomar B, Anders H‐J, Desai J, Mulay SR. Neutrophils and neutrophil extracellular traps drive necroinflammation in COVID‐19. Cells. 2020;9:1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shi LZ, Bonner JA. Bridging radiotherapy to immunotherapy: the IFN–JAK–STAT Axis. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:12295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ziegler CG, Miao VN, Owings AH, et al. Impaired local intrinsic immunity to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in severe COVID‐19. Cell. 2021;184:4713‐4733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shen Z, Xiao Y, Kang L, et al. Genomic diversity of severe acute respiratory syndrome–coronavirus 2 in patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:713‐720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fan J, Li X, Gao Y, et al. The lung tissue microbiota features of 20 deceased patients with COVID‐19. J Infect. 2020;81:e64‐e67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Russell KA, Garbin LC, Wong JM, Koch TG. Mesenchymal stromal cells as potential antimicrobial for veterinary use—a comprehensive review. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:3056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sengupta V, Sengupta S, Lazo A, Woods P, Nolan A, Bremer N. Exosomes derived from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells as treatment for severe COVID‐19. Stem Cells Dev. 2020;29:747‐754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Arabpour M, Saghazadeh A, Rezaei N. Anti‐inflammatory and M2 macrophage polarization‐promoting effect of mesenchymal stem cell‐derived exosomes. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;97:107823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. V'kovski P, Gultom M, Kelly JN, et al. Disparate temperature‐dependent virus–host dynamics for SARS‐CoV‐2 and SARS‐CoV in the human respiratory epithelium. PLoS Biol. 2021;19:e3001158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Barberis E, Vanella VV, Falasca M, et al. Circulating exosomes are strongly involved in SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Front Mol Biosci. 2021;8:632290. 10.3389/fmolb.2021.632290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mulay A, Konda B, Garcia G, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 infection of primary human lung epithelium for COVID‐19 modeling and drug discovery. Cell Rep. 2021;35:109055. 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hou YJ, Okuda K, Edwards CE, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 reverse genetics reveals a variable infection gradient in the respiratory tract. Cell. 2020;182:429‐446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rahbarghazi R, Keyhanmanesh R, Aslani MR, Hassanpour M, Ahmadi M. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and condition media diminish inflammatory adhesion molecules of pulmonary endothelial cells in an ovalbumin‐induced asthmatic rat model. Microvasc Res. 2019;121:63‐70. 10.1016/j.mvr.2018.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Qu Q, Pang Y, Zhang C, Liu L, Bi Y. Exosomes derived from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells inhibit vein graft intimal hyperplasia and accelerate reendothelialization by enhancing endothelial function. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;11:133. 10.1186/s13287-020-01639-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kuate S, Cinatl J, Doerr HW, Uberla K. Exosomal vaccines containing the S protein of the SARS coronavirus induce high levels of neutralizing antibodies. Virology. 2007;362:26‐37. 10.1016/j.virol.2006.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pesce E, Manfrini N, Cordiglieri C, et al. Exosomes recovered from the plasma of COVID‐19 patients expose SARS‐CoV‐2 spike‐derived fragments and contribute to the adaptive immune response. Front Immunol. 2022;12:785941. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.785941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. El‐Shennawy L, Hoffmann AD, Dashzeveg NK, et al. Circulating ACE2‐expressing extracellular vesicles block broad strains of SARS‐CoV‐2. Nat Commun. 2022;13:405. 10.1038/s41467-021-27893-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Popowski KD, Dinh P‐UC, George A, Lutz H, Cheng K. Exosome therapeutics for COVID‐19 and respiratory viruses. VIEW. 2021;2:20200186. 10.1002/VIW.20200186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Inal JM. Decoy ACE2‐expressing extracellular vesicles that competitively bind SARS‐CoV‐2 as a possible COVID‐19 therapy. Clin Sci. 2020;134:1301‐1304. 10.1042/cs20200623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Scott TA, Supramaniam A, Idris A, et al. Engineered extracellular vesicles directed to the spike protein inhibit SARS‐CoV‐2. Mol Ther‐Methods Clin Dev. 2022;24:355‐366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kim HK, Cho J, Kim E, et al. Engineered small extracellular vesicles displaying ACE2 variants on the surface protect against SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. J Extracell Vesicles. 2022;11:e12179. 10.1002/jev2.12179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yan S, Ye P, Aleem MT, Chen X, Xie N, Zhang Y. Mesenchymal stem cells overexpressing ACE2 favorably ameliorate LPS‐induced inflammatory injury in mammary epithelial cells. Front Immunol. 2022;12:796744. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.796744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zhang Q, Jeppesen DK, Higginbotham JN, Franklin JL, Crowe JE, Coffey RJ. Angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2‐containing small extracellular vesicles and exomeres bind the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 spike protein. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:958‐961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Elsharkasy OM, Nordin JZ, Hagey DW, et al. Extracellular vesicles as drug delivery systems: why and how? Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2020;159:332‐343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Xu J, Tao J, Wang J. Design and application in delivery system of intranasal antidepressants. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020;8:626882. 10.3389/fbioe.2020.626882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Herman S, Fishel I, Offen D. Intranasal delivery of mesenchymal stem cells‐derived extracellular vesicles for the treatment of neurological diseases. Stem Cells. 2021;39:1589‐1600. 10.1002/stem.3456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Zhang Y‐T, He K‐J, Zhang J‐B, Ma Q‐H, Wang F, Liu C‐F. Advances in intranasal application of stem cells in the treatment of central nervous system diseases. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12:210. 10.1186/s13287-021-02274-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Guo S, Perets N, Betzer O, et al. Intranasal delivery of mesenchymal stem cell derived exosomes loaded with phosphatase and tensin homolog siRNA repairs complete spinal cord injury. ACS Nano. 2019;13:10015‐10028. 10.1021/acsnano.9b01892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Moss LD, Sode D, Patel R, et al. Intranasal delivery of exosomes from human adipose derived stem cells at forty‐eight hours post injury reduces motor and cognitive impairments following traumatic brain injury. Neurochem Int. 2021;150:105173. 10.1016/j.neuint.2021.105173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Dinh P‐UC, Paudel D, Brochu H, et al. Inhalation of lung spheroid cell secretome and exosomes promotes lung repair in pulmonary fibrosis. Nat Commun. 2020;11:1064. 10.1038/s41467-020-14344-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kennedy TL, Russell AJ, Riley P. Experimental limitations of extracellular vesicle‐based therapies for the treatment of myocardial infarction. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2021;31:405‐415. 10.1016/j.tcm.2020.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Li X, Corbett AL, Taatizadeh E, et al. Challenges and opportunities in exosome research—perspectives from biology, engineering, and cancer therapy. APL Bioeng. 2019;3:011503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Imai T, Takahashi Y, Nishikawa M, et al. Macrophage‐dependent clearance of systemically administered B16BL6‐derived exosomes from the blood circulation in mice. J Extracell Vesicles. 2015;4:26238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Liu Y, Defourny KA, Smid EJ, Abee T. Gram‐positive bacterial extracellular vesicles and their impact on health and disease. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed in the manuscript are included in this article.