Abstract

Objective

To investigate the relations between young children's negative emotions and their mothers' mental health during the COVID‐19 pandemic.

Background

The COVID‐19 pandemic caused the public a certain degree of psychological symptoms, and family environments and relations have been changed dramatically as a result. The relations between young children's negative emotions and their mothers' mental health have not been sufficiently determined for the context of a pandemic or other large‐scale crises.

Method

A survey was administrated on 8119 Chinese mothers of 3‐ to 6‐year‐old children with the Symptom Checklist 90 and the Child Negative Emotion Questionnaire.

Results

The canonical correlation results indicated that there were covariation trends between young children's anger and their mother's obsessive–compulsive symptoms and hostility, children's fear and mothers' phobic anxiety, and children's tension and mothers' interpersonal sensitivity and depression. These correlations were all positively significant.

Conclusion

During the COVID‐19 pandemic, the predictive power of young children's negative emotions to their mothers' mental health was greater than that of the reverse.

Implications

This study provides a scientific guidance on the regulation of young children's negative emotions and the improvement of mothers' mental health during the pandemic as well as potential emergencies in the future.

Keywords: COVID‐19, mental health, mother–child interaction, negative emotion

The COVID‐19 pandemic is the most influential global public health emergency that humans have encountered in the past 100 years. Similar to the psychological problems caused by the crisis with the SARS virus in 2003, the pandemic not only caused the public mental health problems, such as stress, anxiety, depression, anger, and fear (Torales et al., 2020), it also increased confusion, loneliness, boredom, and anger, triggered by the public's posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and isolation (Brooks et al., 2020). Families throughout the world have suffered during the COVID‐19 pandemic, and the family environment and family relations have been changed dramatically (Hentges et al., 2021; Yan et al., 2021; Yoshikawa et al., 2020).

PARENT–CHILD INTERACTIONS UNDER THE IMPACT OF COVID‐19 PANDEMIC

Relevant studies have confirmed that parents' psychological adjustment level and mental health status are closely related to children's emotions. Moed et al. (2017) found that the negative emotional reactions in parent–child interactions were related to the negative emotions of young children. Young children's low‐level negative emotions were positively correlated with the good parenting behavior, but parents' high degree of negative emotions was positively connected to children's externalization problems (Rispoli, 2018). Mirabile et al. (2018) found that parents' supportive emotions in parent–child cooperation had a protective effect on children's mental health. Rothenberg et al. (2018) pointed out that parental emotional socialization had a continuous effect on improving children's emotional regulation. Liu et al. (2017) found that parental emotional regulation and depression might aggravate children's difficulty with emotional regulation, thereby increasing the likelihood of children suffering from depression. Thus, there is a close relationship in the interaction of mental health and emotions between parents and children.

According to ecological systems theory and family systems theory, children develop within the context of the system of relationships that form their environment. Children and the external environment reciprocally influence each other. Individuals are affected by the macro system with which the society interacts (Liu & Meng, 2009). At the same time, they are influenced by micro systems, such as the family, professional groups, and other social groups; intermediate systems; as well as outer system interaction. The family is an important micro system in which the behavior and emotional interaction of each family member affect the other members (Fitzgerald et al., 2020; Minuchin, 1985). Young children are not only subjects affected by this special life and interpersonal environment; they are also agents who have an impact on these environments. As mentioned earlier, existing studies have paid more attention to the influence of the parents' psychological adjustment and the impact of health status on their children's mood. Less consideration has been placed to the child's influence on the parents' mental health as the actor. In the parent–child interaction, the child is not in a completely passive position. They may influence the emotional changes of their parents through their own behaviors (Gao & Yan, 2017).

The COVID‐19 pandemic constitutes a unique environment for social life and interpersonal interaction. In sudden public health events such as this, young children often show varying degrees of negative emotions, which are mainly manifested as tension, fear, irritability, and anger (Ji, 2020). Brooks et al. (2020) pointed out that isolation is an unpleasant experience that can cause tremendous stress. During the pandemic, young children have received negative information related to the pandemic on a regular basis, often making them feel nervous (Wei et al., 2020; Yoshikawa et al., 2020). Fear often develops in those who lack the ability to deal with and get out of scary situations (Xiao, 2017). Wei et al. (2020) found that the sudden outbreak of the pandemic led to lockdown of cities and suspension of classes; it was difficult for children to cope with this complicated situation, and most had varying degrees of fear. Individuals often experience some stress reactions after experiencing major sudden public crisis events (Jiao et al., 2020), and many people were anxious at the height of the COVID‐19 crisis (Li et al., 2020).

In an effort to prevent the spread of the virus, the Chinese government restricted social activities during the pandemic. Conducting all activities for a long period in a small family space may lead to boredom, and living in isolation at home reduces opportunities for children to communicate and interact with peers and teachers (Ma et al., 2020). This is irritating for young children, who enjoy time spent with other young people and are eager to go out to play (Ma et al., 2020). However, under the stay‐at‐home policy during the COVID‐19 pandemic, the family home was the primary place for most activities. Research has indicated that longer confinement in the home can magnify the more subtle conflicts that are not usually noticeable in the family; the number of parent–child conflicts increases, and children may become angry (Chen, 2020). These circumstances may negatively affect parents' mental health, leading to interpersonal sensitivity, anxiety, or even hostility (Yoshikawa et al., 2020). Therefore, relationships during the pandemic—particularly the relation between negative mental and emotional states of young children and their parents during the COVID‐19 pandemic—are worthy of attention.

For example, in a study of the 1060 participants investigated in China, 73% reported having moderate and higher level of psychological symptoms during the pandemic (Tian et al., 2020). This finding was particularly strong for obsessive–compulsive symptoms, interpersonal sensitivity, fear, and anxiety. Of interest for mental health during the pandemic, research has shown that the severity of mental health symptoms can be lower for mothers when they spend more time interacting with their children (Bronte‐Tinkew et al., 2007). This raises the question of how increased interaction with children during the pandemic may influence mothers' mental health symptoms.

CURRENT STUDY

This research begins to address the relation between young children's negative emotions and the mental health of their mothers. Implications of addressing this question may be identification of the psychological insights this research can add to the literature on the pandemic. On the basis of the adjectives about negative emotions in the Positive and Negative Affect Scale, in combination with several social and psychological survey reports that have been developed during the COVID‐19 pandemic, we selected four negative emotions (tension, fear, anger, and irritability) that were likely to surface in children during the COVID‐19 pandemic and focused on the exploration of the relation between young children's negative emotions and their mothers' mental health. This study assumes that there are close correlations between these two factors. Through an investigation and analysis, it provides scientific guidance on the regulation of children's negative emotions and improvement of mothers' mental health, in relation to both the COVID‐19 pandemic and potential emergencies in the future.

METHOD

Participants

Data were collected through the WenJuanXing public online platform (https://www.wjx.cn) from February 1, 2020, to March 1, 2020, at the beginning of the COVID‐19 pandemic in China. The Chongqing Early Childhood Education Quality Monitoring and Evaluation Research Center of Chongqing Normal University provided ethical approval to conduct the study. Participants were 8119 mothers of young children aged 3 to 6 years from 31 provincial administrative units in China who filled out this questionnaire. We checked and excluded invalid data with the following three criteria: (a) the answers had obvious regularity, (b) there were missing items in the completed questionnaire, and (c) subjects with the same IP address completed the survey more than once. After verification, these 8119 data were valid. The children comprised 4499 boys (55.41%), 3620 girls (44.59%); 705 three‐year‐olds (8.68%), 2062 four‐year‐olds (25.40%), 3112 five‐year‐olds (38.33%), and 2240 six‐year‐olds (27.59%); 3728 children living in urban areas (45.92%); 1791 children living in townships (22.06%); 2600 children living in villages (32.02%); 1361 children from single‐child families (16.76%); and 6758 children from multiple‐child families (83.24%).

Measures

Symptom Checklist—90

The Symptom Checklist—90 (SCL‐90) is widely used to identify individuals' mental health status. It contains 90 items with nine subscales: Somatization (SOM), Obsessive–Compulsive (OC), Interpersonal Sensitivity (IS), Depression (DEP), Anxiety (ANX), Hostility (HOS), Phobic Anxiety (PHOB), Paranoid Ideation (PAR), and Psychoticism (PSY). Each item adopts a five‐level scoring system, with 1 = not at all, 2 = a little bit, 3 = moderately, 4 = quite a bit, and 5 = extremely. The higher the score, the more negative the symptom is. In this study, the mothers of young children conducted self‐evaluation based on their own feeling on the psychological symptoms during the pandemic. Cronbach's α coefficient of the scale in this study is 0.97.

Child Negative Emotion Questionnaire

Our research group developed a scale to measure the four types of typical negative emotions (tension, fear, anger, and irritability) that young children have experienced during the COVID‐19 pandemic (see Appendix in the supplemental materials). There are 17 items on the scale with a five‐point scoring system: 1 = not at all, 2 = a little bit, 3 = moderately, 4 = quite a bit, and 5 = extremely. An example question is: “My child can't sit still and is constantly moving while staying at home.” The higher the mother's rating score, the more negative young children's emotion is. It was reported by the mothers to evaluate the four emotions of tension, fear, irritability, and anger that the young children were exhibiting during the pandemic. Cronbach's α coefficient of the total scale is 0.85, and Cronbach's α coefficient analysis results of each emotional dimension show that it has good reliability (αtension = 0.80, αfear = 0.82, αanger = 0.76, αirritability = 0.78). The confirmatory factor analysis and fitting indicators were as the following: χ2/df = 19.36 (χ2 = 2188.22, df = 113), goodness of fit index = 0.97, comparative fit index = 0.96, incremental fit index = 0.96, Tucker–Lewis index = 0.95, root mean square of approximation = 0.05. According to the fitting index standard, all the other indexes are relatively ideal except that the value of χ2/df was slightly higher due to the large sample.

Common method deviation avoidance

Usually, data collection through participant self‐report may lead to a bias effect. To avoid this, participants' privacy concerns were addressed in the instructions for the questionnaire, checks on ambiguity and subject bias were undertaken, and investigations were anonymous and conducted online. The results of Harman single factor test showed that there were 17 factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, and the variance explained by the first factor was 25.89%, which was less than the critical standard of 40%. Therefore, the common method bias effect did not affect this study.

RESULTS

Conditions of children's negative emotions and mothers' mental health

The distribution of the mean and standard deviation of young children's negative emotions and their mother's mental health is presented in Supplemental Table 1. Among young children's negative emotions, irritability was the most severe, anger the second most severe, and fear the least severe. As shown in Supplemental Table 2, the proportion of young children with negative emotions at the moderate or greater level was not small, especially irritability, which was greater than 30%. Although the proportion of each negative emotion at the quite a bit and extreme levels was small considering the large sample in this survey, the absolute number nonetheless deserves attention.

As the results shown in Supplemental Table 3 indicate, the most prominent mental health concern mothers described was obsessive–compulsive symptoms and the lowest was somatization. The proportion of the obsessive–compulsive symptoms at the mild or greater level was close to 30%.

Compared with the Chinese norm (Tong, 2010), the results shown in Supplemental Table 4 indicate that the mothers' mental health was significantly lower on the nine subscales of the SCL‐90 during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Among them, the degree of Somatization, Obsessive–Compulsive, Interpersonal Sensitivity, Depression, Anxiety, Hostility, Phobic Anxiety, Paranoid Ideation, and Psychoticism were significantly lower than Chinese norms on the SCL‐90 (p < 0.001).

According to the independent‐sample t test, there are significant differences in young children's negative emotions in the term of gender, t(7,877.54) = 6.58, p < 0.001, and boys' negative emotion levels were significantly higher than those of girls. There were significant differences in young children's negative emotions in relations to the number of children in a family, t(8,117) = −4.82, p < 0.001, and the negative emotion level of the children from single‐child families was significantly higher than that of the children from multiple‐child families. The results of one‐way analysis of variance indicate that children's negative emotions significantly vary with age, F(3, 8115) = 7.41, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.003. The least significant difference test showed that the level of 3‐year‐old children's negative emotions was significantly higher than that of 6‐year‐old children and that the negative emotion level of 4‐year‐old children was significantly higher than that of 5‐ and 6‐year‐old children. However, there was no significant difference in children's negative emotions in terms of their place of residence, F(2, 8116) = 2.38, p = 0.09, η2 = 0.001.

Correlations between children's negative emotions and mothers' mental health

A simple correlation analysis on children's negative emotions and their mothers' mental health was carried out. The results demonstrate that all dimensions of children's negative emotions (fear, anger, tension, irritability) were related to the dimensions of their mothers' mental health (Somatization, Obsessive–Compulsive, Interpersonal sensitivity, Depression, Anxiety, Hostility, Hostility, Paranoid Ideation, and Psychoticism), as shown in Supplemental Table 5.

Canonical correlation analysis on children's negative emotions and mothers' mental health

This study further investigated the covariant relations between the two sets of variables of children's negative emotions and mothers' mental health. Through the canonical correlation analysis, a total of three canonically correlated variables were obtained (see Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Typical variables of children's negative emotions and mothers' mental health

| CCC | Eigenvalue | Wilks statistic | F | Num. df | Denom. df | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.46 | 0.27 | 0.74 | 70.60 | 36.00 | 30,378.67 | 0.000 |

| 2 | 0.23 | 0.06 | 0.94 | 21.57 | 24.00 | 23,513.37 | 0.000 |

| 3 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.99 | 4.33 | 14.00 | 16,216.00 | 0.000 |

Note. CCC = canonical correlation coefficient; Denom. = denominator; Num. = numerator.

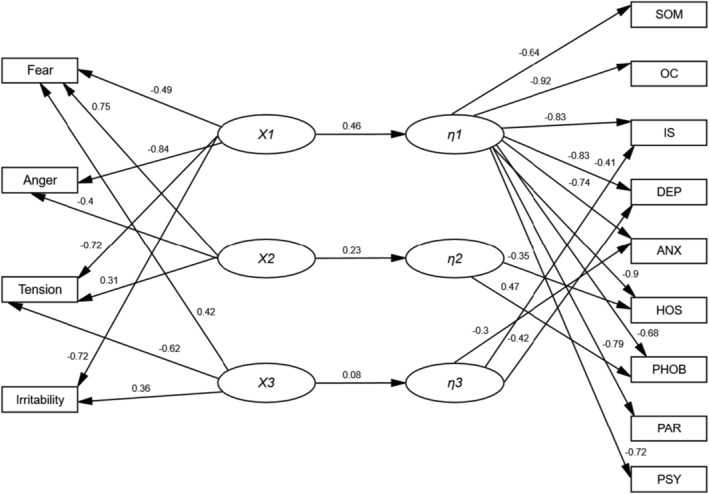

According to the nonstandardized canonical coefficients, for the first canonical variable—that is, children's negative emotions—the loading associated with each emotion was >0.40, and all were negative values (see Table 2). For the first canonical variable—mothers' mental health—the loading associated with each dimension was >0.60, and its value was also negative (see Table 3). The covariation trend of the two groups of variables in the first pair of typical variables is the same. For the first pair of typical variables, shown in the Χ1 column, the loadings for anger is the largest among children's negative emotions, with a negative value; for the first pair of typical variables, shown in the η1 column, the loadings of obsessive–compulsive symptoms and hostility are the largest for mothers' mental health, with negative values, indicating that the anger in children's negative emotions and the obsessive–compulsive symptoms and hostility in the mothers' mental health had a covariation trend with a positive correlation. For the second pair of typical variables, shown in the Χ2 column, the loadings of fear is largest among children's negative emotions, with a positive value; for the second pair of typical variables shown in the η2 column, the loadings of the phobic anxiety is the largest among mothers' mental health, with a positive value, indicating that children's fear and mother's phobic anxiety also had a covariation trend with a positive correlation. For the third pair of typical variables, as shown in the Χ3 column, the loadings for tension is the largest among children's negative emotions, with a negative value; for the second pair of typical variables, shown in the η3 column, the loadings of interpersonal sensitivity and depression are the largest among mothers' mental health, with negative values, indicating that the tension in children's negative emotions and the interpersonal sensitivity and depression in the mothers' mental health still show a covariation trend with a positive correlation.

TABLE 2.

Unstandardized canonical coefficients and correlation coefficients of various dimensions and canonical variables of children's negative emotions

| Unstandardized typical coefficient | Correlation coefficient (loadings) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Χ1 | Χ2 | Χ3 | Χ1 | Χ2 | Χ3 | |

| Fear | −0.29 | 1.14 | 0.85 | −0.49 | 0.75 | 0.42 |

| Tension | −0.59 | 0.52 | −1.45 | −0.72 | 0.31 | −0.62 |

| Anger | −0.80 | −1.00 | 0.18 | −0.84 | −0.40 | 0.08 |

| Irritability | −0.45 | −0.31 | 0.58 | −0.72 | −0.29 | 0.36 |

TABLE 3.

Unstandardized canonical coefficients and correlation coefficients of various dimensions and canonical variables of mothers' mental health

| Unstandardized typical coefficient | Correlation coefficient (loadings) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| η1 | η2 | η3 | η1 | η2 | η3 | |

| Somatization | −0.07 | −1.57 | −0.90 | −0.64 | −0.18 | −0.29 |

| Obsessive Compulsive | −1.33 | 1.65 | 2.19 | −0.92 | 0.24 | 0.01 |

| Interpersonal Sensitivity | −0.27 | 0.28 | −2.92 | −0.83 | 0.15 | −0.41 |

| Depression | −0.05 | −1.42 | −2.76 | −0.83 | −0.06 | −0.42 |

| Anxiety | 0.32 | 1.44 | −0.43 | −0.74 | 0.19 | −0.30 |

| Hostility | −1.18 | −2.48 | 1.12 | −0.90 | −0.35 | −0.00 |

| Phobic Anxiety | −0.31 | 2.32 | 0.16 | −0.68 | 0.47 | −0.22 |

| Paranoid Ideation | −0.40 | 0.06 | 3.19 | −0.79 | 0.02 | 0.07 |

| Psychoticism | 0.53 | 0.08 | −0.39 | −0.72 | 0.07 | −0.27 |

According to the canonical correlation coefficient and the correlation coefficients (loadings) of the two variables of children's negative emotions and mothers' mental health with the corresponding dimensions, the canonical correlation path diagram can be drawn (see Figure 1). The correlation coefficients of each dimension and the typical variables reflect the dimensions on the typical variables. The sign of the correlation coefficient on the same pair of typical variables represents the directionality of the covariation trend.

FIGURE 1.

Typical correlation structure between children's negative emotions and their mothers' mental health

Note. The figure only lists the variable relations with typical factor loadings >0.30, and the negative sign before the value indicates the directionality of the value.

Through the typical redundancy analysis of children's negative emotions and mothers' mental health (Table 4), the square of the canonical correlation coefficient of the first pair of typical variables is 0.212, which accounts for 21.2% of the total variation; the sum of the determination coefficients of the three pairs of typical variables is 0.273, which contributes 27.3% to the total variation. Typical variables from children's negative emotions have a 13.4% total predictive power for the variation of mothers' mental health, which is slightly greater than the predictive power of typical variables from mothers' mental health for children's negative emotions (11.7%).

TABLE 4.

Typical redundancy analysis results of children's negative emotion and mothers‘mental health

| Typical variables | Children's negative emotions | Mother's mental health | CCC square | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extract % of variance | Overlapping | Extract % variance | Overlapping | ||

| 1 | 0.493 | 0.104 | 0.621 | 0.131 | 0.212 |

| 2 | 0.225 | 0.012 | 0.055 | 0.003 | 0.054 |

| 3 | 0.173 | 0.001 | 0.070 | 0.000 | 0.007 |

Note. CCC = canonical correlation coefficient.

DISCUSSION

The relation between children's negative emotions and their mothers' mental health has not been sufficiently determined in the context of a pandemic or other large‐scale crises. There has been increasing work on this topic, particularly on the bidirectional relations between parental and children's functioning (Hentges et al., 2021; Yan et al., 2021). This study not only found a correlation between the two through canonical correlation analysis, but also showed covariation in patterns between children's negative emotions and their mothers' mental health, which validates the rationality of the hypothesis and contributes some valuable findings to this field.

Children's anger and mothers' hostility and obsessive–compulsive symptoms

The results of this study show that children's anger is positively correlated with mothers' hostility and obsessive–compulsive symptoms. Anger is a primitive emotional reaction of individuals, and it is also a fierce emotion often found in young children (Luo, 2011). Gao (2004) pointed out that the reasons for children's anger including not being able to have something immediately, being disappointed by something, being intimidated, or feeling helpless. During the pandemic, 60% of children worldwide lived in fully or partially closed countries, and physical isolation measures and restriction of movement had a negative impact on young children (United Nations, 2020). Children who stay at home for a long time cannot go out and play with their peers because of restricted activities, and they may get angry (Professional Committee on Early Childhood Development of Maternal and Child Health Research Association, 2020). As for mothers' hostility and obsessive–compulsive symptoms, in addition to generating negative effects on the general population, the COVID‐19 lockdown may be creating a particularly stressful environment for parents, who face concerns over their family's health, their children's isolation from teachers and peers, and their management of homeschooling and other daily commitments (Fontanesi et al., 2020; Romero et al., 2020; Yoshikawa et al., 2020). For instance, Chinese parents often require children to abide by rules related to the pandemic, such as requiring them to stay at home and asking them to wear masks and wash hands frequently. More compulsory regulations will increase the frequency of parent–child conflict (Yoshikawa et al., 2020). The positive correlation between children's anger and mothers' obsessive–compulsive symptoms and hostility may be due to the reciprocal influence of children's emotions and parents' mental health. There are both top‐down intergenerational transmission effects and bottom‐up counteractions (Silk et al., 2011). Piersigilli et al. (2020) pointed out that although the proportion of children infected in this pandemic was not the largest among age groups, their resistance was poor, and they required specific protection. The degree of parental intervention in children's emotional and behavioral disorders can promote the development of children's ability to self‐regulate (Hajal & Blair, 2020).

Children's fear and mothers' phobic anxiety symptoms

This study has founded that young children's fear is positively correlated with mothers' phobic anxiety. The novelty of a situation and the threat to ways of life have a direct stimulus effect on fear (Si & Zhu, 2011; Zhou & Wu, 2011). The pandemic is an unprecedented global public health, humanitarian, socioeconomic, and human rights crisis, which to some extent exacerbated the vulnerability of affected children (United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund, 2020). Survey data indicate that 62.5% of young children had varying degrees of fear during the pandemic. When they hear about it, they feel scared and worried that they and their family members might be infected with the virus. The World Health Organization (2020) recommended the use of social distancing and staying home to reduce the spread of the virus, which may have aggravated the fear of young children. The relation between young children's fear and mothers' phobic anxiety may be accounted for by the traumatic stress response. As for posttraumatic stress disorder, parents' stress response is closely related to negative emotions and other symptoms of stress that they see in their children (Egberts et al., 2018). During the pandemic, parents and children stayed together for long periods, and the worries and fears that parents perceive in their children directly was reflected in themselves. In addition, individuals under confinement experience deep‐seated frustration around the need to ensure the protection of themselves and their families, but this high degree of vigilance often leads to fear, anxiety, and pain (Matias et al., 2020). Parents may feel unable to protect their children, and the degree of phobic anxiety will increase with the deepening of their children's fear.

Children's tension and mothers' interpersonal sensitivity and depression symptoms

This study found that children's tension is positively correlated with mothers' interpersonal sensitivity and depression. The survey data show that 47.15% of participants' children felt nervous during the pandemic, and 17.58% were moderately or more severely nervous. Young children feel nervous when going to a new place and will take a while to calm down. Young children usually need their parents' presence when they go to crowded places, and they rely on their parents. The relation between children's tension and mothers' interpersonal sensitivity may be accounted by parent–child attachment. Early childhood security usually comes from attachment to the mother. This attachment is inversely proportional to children's own emotional regulation ability. The mother's emotional socialization can regulate the relationship between the two (Ahmetoglu et al., 2018). Attachment can regulate the relationship between mothers' depression and anxiety and a child's development (Gete et al., 2019). If secure attachment is established early, children like to snuggle with their mothers, so they will choose to close to their mothers when they feel nervous. In addition, parents have become cautious in interpersonal relationships outside the family to reduce the risk of infection and relieve children's tension during the pandemic, so they do not bring their children into dense, unfamiliar environments. During the pandemic, parents and children have spent more time together, and it is easier for parents to detect emotional changes in their child; thus, they may be more sensitive than usual (Hentges et al., 2021; Yan et al., 2021; Yoshikawa et al., 2020). However, due to a lack of specialized knowledge and skills, parents often fail to help young children regulate negative emotions and may even promote worsening of young children's tension. For this reason, parents may feel guilty and worried, which in turn may result in their children's psychological problems becoming more serious.

Children's tension and mothers' paranoid ideation symptoms

In this study, the correlation coefficient (loadings) for the third pair of typical variables, paranoid ideation, decreased, which is consistent with the findings reported by Su et al. (2020). With the occurrence of public health incidents, relationships between people have become relatively simple, and paranoid ideation has been self‐corrected to a certain extent. Human beings rely on this conscious or unconscious psychological response to develop strength to deal with common or universal difficulties, which is conducive to the survival of humans. In this study, 52.89% of the children felt nervous when they went to a new place, and many children had increased tension due to the pandemic. Parents staying with their children for long periods are likely to detect their children's negative emotions. When children are nervous and tense, parents usually attempt to alleviate these negative feelings, and the attention to their own inner world may be overlooked, so that personal paranoid ideation is gradually reduced (Jiao et al., 2020). From this perspective, covariation trends between children's tension and mothers' paranoid ideation are opposite of each other. However, conclusive explanation of this result needs to be verified by additional research.

Implications

Our findings further confirm ecological system theory and family system theory. On this basis, for emergent public health incidents that may occur in the future, we should adopt bidirectional adjustment to relieve children's negative emotions and improve mothers' mental health; this might include revealing information about the pandemic in a more easygoing, less frightening manner; asking open questions and listening to children's ideas and concerns; providing a safe environment; and parents' attention to self‐care and their own emotions.

It is worth emphasizing that fathers' participation in upbringing is also crucial. Fathers play important roles in children's growth, especially during major public health and other emergencies. Actions taken to fight the pandemic by all family members will have a positive effect on children's crisis management, mental resilience, and many other aspects. Therefore, in the post‐pandemic era and in possible future public health crises, fathers should increase their share of the burden of responsibility and participate in care of their children.

In addition, monitoring of the mental health of special groups, such as young children and their families, can be strengthened in accordance with local conditions. National or local governments can offer psychological counseling video clips that are appropriate for children's developmental level to relate to their emotions and also arrange for mental health workers to conduct psychological counseling and interventions in a timely manner, based on the characteristics of different groups and the need for such services. In general, this study not only contributes to the enrichment of the related research on children's negative emotions and mothers' mental health, but also provides a reference to establish a psychological service system to cope with public health emergencies.

Conclusion

During the COVID‐19 pandemic, young children's negative emotions have been closely related to their mothers' mental health. There are covariation trends between children's anger and their mother's obsessive–compulsive symptoms and hostility, between children's fear and their mothers' phobic anxiety, and between children's tension and their mothers' interpersonal sensitivity and depression, with significant positive correlations. The predictive power of children's negative emotions on their mothers' mental health is greater than that of the reverse.

Limitations

There are some limitations to this study. It is cross‐sectional, conducted during the unique period of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Without measuring mothers' mental health before the pandemic, there is a lack of longitudinal tracking data as the pandemic normalized, and more information about the family (e.g., average family socioeconomic status, mothers' employment status) should be collected in future work. The mental health of mothers during the COVID‐19 pandemic is affected not only by children's negative emotions, but also by other factors that were not investigated here. This study considers only mothers' mental health, without looking at the roles of fathers and other potential caregivers. Children's emotions were not directly measured, but only indirectly studied through maternal perceptions.

Supporting information

Appendix S1 Supporting Information

Wei, Y. , Wang, L. , Zhou, Q. , Tan, L. , & Xiao, Y. (2022). Reciprocal effects between young children's negative emotions and mothers' mental health during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Family Relations, 1–13. 10.1111/fare.12702

Funding information This study was funded by Chongqing Social Science Planning Project (no. 2019YBJJ102), Chongqing Education Science 13th Five‐Year Plan Special Key Project (no. 2020‐YQ‐09), and Chongqing University Outstanding Talents Support Program.

REFERENCES

- Ahmetoglu, E. , Ildiz, G. I. , Acar, I. H. , & Encinger, A. (2018). Children's emotion regulation and attachment to parents: parental emotion socialization as a moderator. Social Behavior and Personality, 46(6), 9693–984. 10.2224/sbp.6795 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bronte‐Tinkew, J. , Moore, A. K , Matthews, G. , & Carrano, J. (2007). Symptoms of major depression in a sample of fathers of infants: Sociodemographic correlates and links to father involvement. Journal of Family Issues, 28(1), 61–99. 10.1177/0192513X06293609 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, S. K. , Webster, R. K. , Smith, L. E. , Woodland, L. , Wessely, S. , Greenberg, N. , & Rubin, G. J. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet, 395(10227), 912–920. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H. (2020). Uncover the secret behind emotions based on the perspective of parent–child interaction during the COVID‐19 epidemic [in Chinese]. Mental Health Education in Primary and Secondary Schools, 12, 73–76. [Google Scholar]

- Egberts, M. R. , Rens, V. D. S. , Geenen, R. , & Van Loey, N. E. E. (2018). Mother, father and child traumatic stress reactions after paediatric burn: within‐family co‐occurrence and parent–child discrepancies in appraisals of child stress. Burns, 44(4), 861–869. 10.1016/j.burns.2018.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald, M. , London‐Johnson, A. , & Gallus, K. L. (2020). Intergenerational transmission of trauma and family systems theory: An empirical investigation. Journal of Family Therapy, 42(3), 406–424. 10.1111/1467-6427.12303 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fontanesi, L. , Marchetti, D. , Mazza, C. , Di Giandomenico, S. , Roma, P. , & Verrocchio M. C. (2020). The effect of the COVID‐19 lockdown on parents: a call to adopt urgent measures. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(Suppl. 1), S79–S81. 10.1037/tra0000672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao, P. Y. , & Yan, N. (2017). Status quo and progress of research on parental reactivity to child behaviors [in Chinese]. Journal of Bio‐Education, 5(04), 223–227. 10.3969/j.issn.2095-4301.2017.04.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gete, S. , Calderon‐Margalit, R. , Grotto, I. , & Ornoy, A. (2019). A comparison of the effects of maternal anxiety and depression on child development. The European Journal of Public Health, 29(Suppl. 4), 105. 10.1093/eurpub/ckz185.275 30169634 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hentges, R. F. , Graham, S. A. , Plamondon, A. , Tough, S. , & Madigan, S. (2021). Bidirectional associations between maternal depression, hostile parenting, and early child emotional problems: Findings from the All Our Families cohort. Journal of Affective Disorders, 287, 397–404. 10.1016/j.jad.2021.03.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji, X. J. (2020, February 16). Comfort children's spirit with love—preschool education workers control epidemic to help children grow happily at home [in Chinese]. Zhongguo Jiaoyu Bao. Chinese Education News Network. http://www.jyb.cn/rmtzgjyb/202002/t20200216_295857.html?tdsourcetag=s_pcqq_aiomsg [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, W. Y. , Liu, J. , Sun, Y. , Song, D. F. , Yi, Y. , & Zhang, T. B. (2020). Prevention and management of common psychological problems in children and adolescents during epidemic period of COVID‐19 virus infection [in Chinese]. Chinese Journal of Woman and Child Health Research, 31(02), 192–196. 10.3969/j.issn.1673-5293.2020.02.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li, S. , Wu, Y. , Zhang, F. , Xu, Q. , & Zhou, A. (2020). Self‐affirmation buffering by the general public reduces anxiety levels during the COVID‐19 epidemic. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 52(7), 886–894. 10.3724/SP.J.1041.2020.00886 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. , & Meng, H. M. (2009). Understanding on the ecological system theory of Bronfenbrenner developmental psychology [in Chinese]. China Journal of Health Psychology, 17(02), 250–252. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X. , Lin, X. , Xu, S. , Olson, S. L. , Li, Y. , & Du, H. (2017). Depressive symptoms among children with odd: contributions of parent and child risk factors in a Chinese sample. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(11), 3145–3155. 10.1007/s10826-017-0823-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J. Y. (2011). Developmental psychology of preschool children (p. 196). [in Chinese]. Science Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, T. Y. , Du, Y. S. , Wang, W. J. , Cheng, Y. C. , & He, W. J. (2020). Online survey of children's psychological state at home during the COVID‐19 epidemic [in Chinese]. China Journal of Health Psychology, 28(12), 1842–1847. [Google Scholar]

- Matias, T. , Dominski, F. H. , & Marks, D. F. (2020). Human needs in COVID‐19 isolation. Journal of Health Psychology, 25(7), 871–882. 10.1177/1359105320925149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minuchin, P. (1985). Families and individual development: Provocations from the field of family therapy. Child Development, 56(2), 289–302. 10.2307/1129720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirabile, S. P. , Oertwig, D. , & Halberstadt, A. G. (2018). Parent emotion socialization and children's socioemotional adjustment: when is supportiveness no longer supportive? Social Development, 27(3), 466–481. 10.1111/sode.12226 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moed, A. , Gershoff, E.T. , Eisenberg, N. , Hofer, C. , Losoya, S. , Spinrad, T.L. , & Liew, J. (2017). Parent–child negative emotion reciprocity and children's school success: An emotion–attention process model. Social Development, 26(3), 560–574. 10.1111/sode.12217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piersigilli, F. , Carkeek, K. , Hocq, C. , van Grambezen, B. , Hubinont, C. , Chatzis, O. , Van der Linden, D. , & Danhaive, O. (2020). COVID‐19 in a 26‐week preterm neonate. The Lancet: Child & Adolescent Health, 4(6), 476–478. 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30140-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Professional Committee on Early Childhood Development of Maternal and Child Health Research Association . (2020). Advice on sports guidance for children aged 0–6 during COVID‐19 [in Chinese]. Chinese Journal of Child Health Care, 28(04), 366–369. 10.11852/zgetbjzz2020-0246 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rispoli, K. M. (2018). Role of parent affective behaviors and child negativity in behavioral functioning for young children with developmental delays. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 34(1), 20–28. 10.1177/1088357618800262 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Romero, E. , López‐Romero, L. , Domínguez‐Álvarez, B. , Villar, P. , & Gómez‐Fraguela, J. A. (2020). Testing the effects of COVID‐19 confinement in Spanish children: The role of parents' distress, emotional problems and specific parenting. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(19), 6975. 10.3390/ijerph17196975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothenberg, W. A. , Weinstein, A. , Dandes, E. A. , & Jent, J. F. (2018). Improving child emotion regulation: Effects of parent–child interaction therapy and emotion socialization strategies. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(3), 720–731. 10.1007/s10826-018-1302-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Si, S. B. , & Zhu, X. (2011). A brief introduction of abroad research on children's fear [in Chinese]. Journal of Educational Development Monthly, 3, 24–26. [Google Scholar]

- Silk, J. S. , Shaw, D. S. , Prout, J. T. , O'Rourke, F. , Lane, T. J. , & Kovacs, M. (2011). Socialization of emotion and offspring internalizing symptoms in mothers with childhood‐onset depression. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 32(3), 127–136. 10.1016/j.appdev.2011.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su, B. Y. , Ye, W. X. , Zhang, W. , & Lin, M. (2020). Characteristics of people's psychological stress response under different time and process of COVID‐19 epidemic. Journal of South China Normal University (Social Science Edition), 03, 79–94 [in Chinese]. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, F. , Li, H. , Tian, S. , Yang, J. , Shao, J. , & Tian, C. (2020). Psychological symptoms of ordinary Chinese citizens based on SCL‐90 during the level I emergency response to COVID‐19. Psychiatry Research, 288(Suppl. I), 112992. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong, H. J. (2010). Research on the 20‐year changes of SCL‐90 scale and its norm [in Chinese]. Psychological Science, 33(04), 928–930. [Google Scholar]

- Torales, J. , O'Higgins, M. , Castaldelli‐Maia, J. M. , & Ventriglio, A. (2020). The outbreak of COVID‐19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 66(4), 317–320. 10.1177/0020764020915212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations . (2020). Policy brief: The impact of COVID‐19 on children. https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP–0000114560/download/?_ga=2.240382787.1315908621.1590485239–1188568919.1590485239

- United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund . (2020). Humanitarian action for children: Novel coronavirus (COVID–19) global response. https://www.unicef.cn/reports/novel-coronavirus-covid-19-global-response

- Wei, H. , Chen, L. , Qian, Y. , Hao, Y. , Ke, X. Y. , Cheng, Q. , & Li, T. Y. (2020). Psychological impact of coronavirus disease 2019 on children and adolescents and recommendations for family intervention (1st version) [in Chinese]. Chinese Journal of Child Health Care, 28(04), 370–373. 10.11852/zgetbjzz2020-0200 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2020). Coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) advice for the public. http://www.foodchem.cn/News/209.html

- Xiao, Q. M. (2017). Educational diagnosis of children's psychological behavior (pp. 154–155). [in Chinese]. Wuhan University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, J. J. , Schoppe‐Sullivan, S. , Wu, Q. , & Han, Z. R. (2021). Associations from parental mindfulness and emotion regulation to child emotion regulation through parenting: The moderating role of coparenting in Chinese families. Mindfulness, 12(6), 1513–1523. 10.1007/s12671-021-01619-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa, H. , Wuermli, A. J. , Britto, P. R. , Dreyer, B. , Leckman, J. F. , Lye, S. J. , Ponguta, L. A. , Richter, L. M. , & Stein, A. (2020). Effects of the global COVID‐19 pandemic on early childhood development: Short‐ and long‐term risks and mitigating program and policy actions. The Journal of Pediatrics, 223(1), 188–193. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.05.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y. , & Wu, J. B. (2011). An interview study of preschool children's sources of fear [in Chinese]. Journal of Contemporary Preschool Education, 01, 38–40. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1 Supporting Information