Abstract

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a particularly deadly form of pulmonary fibrosis of unknown cause. In patients with IPF, high serum and lung concentrations of CHI3L1 (chitinase 3 like 1) can be detected and are associated with poor survival. However, the roles of CHI3L1 in these diseases have not been fully elucidated. We hypothesize that CHI3L1 interacts with CRTH2 (chemoattractant receptor–homologous molecule expressed on T-helper type 2 cells) to stimulate profibrotic macrophage differentiation and the development of pulmonary fibrosis and that circulating blood monocytes from patients with IPF are hyperresponsive to CHI3L1–CRTH2 signaling. We used murine pulmonary fibrosis models to investigate the role of CRTH2 in profibrotic macrophage differentiation and fibrosis development and primary human peripheral blood mononuclear cell culture to detect the difference of monocytes in the responses to CHI3L1 stimulation and CRTH2 inhibition between patients with IPF and normal control subjects. Our results showed that null mutation or small-molecule inhibition of CRTH2 prevents the development of pulmonary fibrosis in murine models. Furthermore, CHI3L1 stimulation induces a greater increase in CD206 expression in IPF monocytes than control monocytes. These results demonstrated that monocytes from patients with IPF appear to be hyperresponsive to CHI3L1 stimulation. These studies support targeting the CHI3L1–CRTH2 pathway as a promising therapeutic approach for IPF and that the sensitivity of blood monocytes to CHI3L1-induced profibrotic differentiation may serve as a biomarker that predicts responsiveness to CHI3L1- or CRTH2-based interventions.

Keywords: pulmonary fibrosis, macrophage, chitinase 3 like 1, CRTH2

“Pulmonary fibrosis” is a collective term for fibrotic lung disorders characterized by excessive fibroblast accumulation and extracellular matrix molecule deposition (1). The histological manifestation of pulmonary fibrosis includes varying degrees of inflammation, epithelial cell death, and fibroblast proliferation that eventually lead to distorted pulmonary architecture and compromised lung function. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a particularly deadly form of pulmonary fibrosis of unknown cause (2). The mean survival after diagnosis is only ∼3 years, which is similar to, if not worse than, the prognoses of many types of cancer (3, 4). The therapeutic options for treating IPF have historically been limited (5, 6). Approved therapeutics such as pirfenidone (Esbriet) and nintedanib (Ofev) are able only to slow the progression of the disease (7, 8). They unfortunately do not cure the disease and are associated with severe side effects (9). As a result, the scarring of tissue and disease progression seem irreversible. Thus, there is a need for better understanding of the tissue injury and fibrosis repair associated with IPF to develop more effective preventions and treatments.

Previous studies from our laboratory demonstrated that chitinase-like proteins (CLPs) play an important role in regulating the injury and repair responses in fibrotic lung diseases (10). Chitinase is a family of glycosyl hydrolase proteins that cleave chitin, a polysaccharide. CLPs such as CHI3L1 (chitinase 3 like 1; also referred to as YKL-40 in humans and BRP-39 in mice) (11, 12), on the other hand, bind to chitin but do not cleave it (13). Although chitin and chitin synthesis do not exist in mammals, chitinases and CLPs are widely found in the human lungs and other organs (14–16), which indicates that there is an evolutionary need for their existence. The importance of CHI3L1 is indicated by the large number of diseases characterized by inflammation and remodeling in which CHI3L1 excess has been documented (17–20). In many of these disorders, CHI3L1 is likely produced as a protective response on the basis of its ability to simultaneously decrease epithelial cell apoptosis and stimulate fibroproliferative repair. In patients with IPF, high serum and lung concentrations of CHI3L1 can be detected and are associated with poor survival (21, 22). These findings support the major role of CHI3L1 in fibroproliferative responses. However, the roles of CHI3L1 in these diseases have not been fully elucidated, because the biologic functions of CHI3L1 and the mechanisms by which they are mediated have only recently begun to be studied.

Abundant data indicate that alternatively activated profibrotic “M2” macrophages play an important role in the development of lung fibrosis (23, 24), either via direct effects on matrix remodeling or indirectly by promoting fibroblast accumulation and activation (23, 25, 26). Importantly, circulating monocytes in patients with IPF exhibit increased expression of the M2 activation marker CD206 (25, 26). Our previous research demonstrated that CHI3L1-induced M2 activation is the major mechanism through which CHI3L1 promotes the development of lung fibrosis. Because CHI3L1 lacks enzymatic activity, recent studies were undertaken to identify if CHI3L1 mediates its effector functions through novel cell surface receptors. Yeast two-hybrid screening and other binding and cellular approaches demonstrate that CHI3L1 binds to, signals, and confers tissue responses via IL-13Rα2 (IL-13 receptor subunit alpha-2) (and its β subunit TMEM219 [transmembrane protein 219]) and CRTH2 (chemoattractant receptor–homologous molecule expressed on T-helper type 2 cells) (23). CRTH2 is a G protein–coupled receptor with prostaglandin D2 as its known ligand (26, 27). The ligand and receptor interactions between CHI3L1 and CRTH2 have been further verified with coimmunoprecipitation/IB assays and colocalization immunohistochemistry (10). These studies demonstrated that CHI3L1 and CRTH2 interact to induce profibrotic macrophage differentiation in vivo and in vitro and promoted fibrosis development in a bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis model in mice. In this model, collagen accumulation and gene expression were significantly reduced in mice treated with a CRTH2 inhibitor (CAY10471; Cayman Chemical Inc.) (10).

We hypothesize that CHI3L1 interacts with CRTH2 to promote profibrotic macrophage differentiation and the development of pulmonary fibrosis. We further hypothesize that circulating blood monocytes from patients with IPF are hyperresponsive to CHI3L1–CRTH2 signaling. Our results showed that CRTH2 concentrations were increased in mouse models of lung fibrosis, and the inhibition of CRTH2 prevented fibroproliferation. Furthermore, CRTH2 was found to mediate the differentiation of profibrotic monocyte-derived macrophages, a key feature in fibroproliferative responses. Using human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), we found that monocyte CD206 expression was increased in patients with IPF compared with control subjects, and CHI3L1 stimulation induced a greater increase in CD206 expression in IPF monocytes than control monocytes. Importantly, CHI3L1-induced increase of CD206 expression was attenuated by CRTH2 inhibition. These results demonstrate that CHI3L1 induces profibrotic differentiation via CRTH2 in monocytes from both control subjects and patients with IPF. Moreover, monocytes from patients with IPF appear to be hyperresponsive to CHI3L1 stimulation. These studies support targeting the CHI3L1–CRTH2 pathway as a promising therapeutic approach in patients with IPF and that the sensitivity of blood monocytes to CHI3L1-induced profibrotic differentiation may serve as a biomarker that predicts responsiveness to CHI3L1- or CRTH2-based interventions.

Methods

Animal Models of Pulmonary Fibrosis

In the bleomycin model, sex-matched, 8-week-old C57BL/6 mice (four or more mice per group per experiment, repeated at least three times) were given a single intratracheal bleomycin injection (1.25 U/kg; Teva Parenteral Medicines). Mice were then killed and evaluated on various days after administration on Day 0. IL-13 and TGF-β (transforming growth factor-β) transgene are constitutively expressed by the CC10 (club cell 10 kD) promoter. CRTH2-deficient (CRTH2-knockout) mice were provided by Dr. Nakamura (Tokyo Medical and Dental University). All mice were congenic on a C57BL/6 background and were genotyped as previously described. Lungs were harvested, and tissue sections were stained with anti-CRTH2, anti–CX3CR1 (C-X3-C motif chemokine receptor 1) (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and DAPI.

Quantification of Lung Collagen

Collagen content was determined by quantifying total soluble collagen using the Sircol Collagen Assay kit from Biocolor (Accurate Chemical and Scientific Corporation) per the manufacturer’s instructions.

CRTH2 Inhibitor

To define the roles of CRTH2 in injury and repair responses in other fibrosis mouse models, a well-characterized CRTH2 inhibitor, CAY10471, was used. Each injection contained 0.4 mg of the CAY 10471 compound dissolved in 15.5 μL EtOH, 7.7 μL DMSO, 15.5 μL polyethylene glycol 400, and 33.3 μL PBS, resulting in an injection volume of 72 μL per injection. Mice were given intraperitoneal injections twice per week of either the drug formulation or the vehicle control.

Gene Expression Analysis

Cells processed from human blood were lysed in TRIzol reagents, and then total cellular RNA was extracted using the Qiagen RNeasy Kit per the manufacturer’s instructions. From the mRNA, cDNA was synthesized using the Bio-Rad iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit per the manufacturer’s instructions. The corresponding mRNA concentration was then measured using RT-PCR. The primer sequences for 14s RNA, RPL13α (ribosomal protein L13α), CD206, Arg-1 (arginase 1), YM-1 (chitinase 3 like 1), FIZZ-1 (found in inflammatory zone 1), fibrotic matrix genes, and CRTH2 were obtained from PrimerBank (http://pga.mgh.harvard.edu/primerbank/) or were the same as previously used.

Human Subjects

Subjects with IPF were identified from those being cared for at the Rhode Island Hospital Interstitial Lung Disease Clinic. For inclusion in this study, subjects had to meet criteria for a diagnosis of IPF on the basis of international consensus guidelines. Control subjects were nonsmoking individuals at least 50 years of age without histories of chronic lung disease. Twenty-three patients with IPF and 22 healthy volunteers were included in this study. After informed consent was obtained, peripheral blood was obtained from subjects via standard phlebotomy and collected into heparinized tubes (for plasma) or BD Cell Preparation Tubes (for PBMC isolation). Heparinized whole blood was centrifuged at 1,800 × g for 20 minutes to obtain plasma. PBMC isolation was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. PBMC and plasma samples were labeled with the subject’s study number only (no directly identifying information) and stored at −80°C (plasma) or in liquid nitrogen (PBMCs) until analysis. Baseline demographic data were recorded for all subjects, and for patients with IPF, baseline and follow-up lung function data, vital status, and lung transplantation status were recorded in a longitudinal clinical database.

CHI3L1 ELISA

Measurement of CHI3L1 was performed using a commercially available ELISA kit (Quantikine; R&D Systems). The minimum detectable dose of human CHI3L1 ranged from 1.25 to 8.15 pg/ml. The mean minimum detectable dose was 3.55 pg/ml. Typical patient serum samples in healthy human samples can be detected in the range of 15.9 to 93.5 ng/ml. The experimental protocol follows exactly the Quantikine instructions except for the dilution of serum samples; 1:500 dilution was used instead of 1:50 dilution. The standard curve was created in GraphPad (GraphPad Software Inc.) using a four-parameter logistic curve fit.

Processing of Human Cells

PBMCs were isolated from whole blood using Ficoll-Hypaque–based separation (BD Biosciences) and stored in 90% FBS:10% DMSO. At the time of analysis, PBMCs were thawed and plated on tissue culture dishes. The PBMCs were divided into four treatment groups during plating: control (no treatment), CHI3L1 (R&D Systems), inhibitor to CRTH2 (CAY10471), and both CHI3L1 and CRTH2 inhibitor. One hundred microliters of PBS was used to dissolve 50 μg CHI3L1. A concentration of 0.5 μg/μl was reached, and 2 μl was added to each well to create a final concentration of 500 ng/ml to create an environment that simulated patient physiology. However, CAY10471 is not very soluble in aqueous buffers. Thus, RPMI 1640 growth medium was used to dissolve the molecule, such that solubility was maximized while minimizing toxicity.

Cell cultures were then incubated for 48 hours before processing for flow cytometry analysis or RNA extraction.

Flow Cytometry

The following antibodies were used in mouse studies: CD45–Pacific Blue, CD11b-PE-Cy5, CD64 PerCP-eFluor710, Ly6G-PE, Ly6C-APC, CD206-FITC, and Siglec F–Alexa Fluor 700 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). APC-conjugated antihuman CD206 and PE-conjugated anti-CD14 (BD Pharmingen) were used in the human studies. Percentages of cells coexpressing CD14 and CD206 were used to determine the percentage of M2 differentiation. For all analyses, isotype control staining was subtracted from true antibody staining to determine the percentage of positive cells. Flow cytometry was performed using BD FACSAria. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software version 10.6.1 (FlowJo LLC).

Statistical Analysis

Mouse data are expressed as mean ± SEM. As appropriate, groups were compared using ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc test; follow-up comparisons between groups were conducted using a two-tailed Student’s t test. P values of ⩽0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. In human studies, parametric data were compared using the two-tailed Student’s t test. Nonparametric data were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad. Graphs were generated using Excel (Microsoft) and GraphPad.

Study Approval

Animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Brown University in accordance with federal guidelines. Human studies were approved by the Rhode Island Hospital Institutional Review Board.

Results

CRTH2 Expression Is Increased in Murine Models of Lung Fibrosis

We evaluated CRTH2 mRNA expression in three murine models that are characterized by lung injury and remodeling: the bleomycin model (28), the TGF-β transgenic overexpression model (29), and the IL-13 transgenic overexpression model (30). To evaluate CRTH2 mRNA expression concentrations after bleomycin administration, wild-type (WT) mice were challenged with a single intratracheal bleomycin injection, and CRTH2 mRNA concentrations in whole lung were assessed on Days 3, 7, 10, and 14 using RT-PCR. At each time point, BAL cell pellets were recovered and resuspend to allow alveolar macrophages to adhere, nonadherent cells were removed, and CRTH2 mRNA concentrations were assessed in the attached alveolar macrophage population. Our results demonstrated that although CRTH2 expression in the whole lung remained at similar degrees throughout the 14-day period (Figure 1A), bleomycin administration caused a significant increase in CRTH2 expression in BAL macrophages that were associated with the fibroproliferative repair response (Days 10–14) (Figure 1B). Similar approaches were used to evaluate CRTH2 mRNA expression in TGF-β transgenic mice and IL-13 transgenic mice. These results showed that CRTH2 expression was induced by the transgene expression at the whole-lung level (Figures 1C and 1E) and in alveolar macrophages (Figures 1D and 1F). Previous studies have shown that monocyte-derived alveolar macrophages (MoAMs), but not tissue-resident alveolar macrophages (TRAMs), are the major subpopulation of profibrotic macrophages that are responsible for pulmonary fibrosis pathogenesis (31–33). Follow-up studies demonstrated that the chemokine receptor CX3CR1 would label monocytes and MoAMs, but not TRAMs or other lung cells (32, 34–36). Consistent with these findings, coimmunofluorescence staining demonstrated that CRTH2 was expressed by CX3CR1+ MoAMs (Figure 2A), and CX3CR1/CRTH2 double-positive cells were increased in the lungs in all three models (Figure 2B). These studies demonstrate that CRTH2 is expressed by MoAMs, and its expression is increased during fibroproliferative repair in murine models of lung fibrosis.

Figure 1.

CRTH2 (chemoattractant receptor–homologous molecule expressed on T-helper type 2 cells) expression is increased in murine models of lung fibrosis. (A and B) WT mice were subjected to intratracheal bleomycin administration. Lungs and BAL macrophages were harvested. (C and D) Lungs and BAL macrophages were harvested from WT and TGF-β transgenic (Tg) overexpression mice. (E and F) Lungs and BAL macrophages were harvested from IL-13 Tg overexpression mice. CRTH2 transcript degrees were measured in whole-lung RNA extracts (A, C, and E) and in alveolar macrophage RNA extracts (B, D, and F) using qRT-PCR. Data were assessed using the unpaired Student’s t test. Values are mean ± SEM, with a minimum of five mice in each group. *P ⩽ 0.05 and **P ⩽ 0.01. TGF-β = transforming growth factor-β; WT = wild-type.

Figure 2.

CRTH2 is expressed by monocyte-derived macrophages in the lung. (A) Lung sections from control and the three murine models of lung fibrosis were stained for CRTH2 (red). Sections were costained for CX3CR1 (C-X3-C motif chemokine receptor 1) (green). Images are representative of three mice. Scale bars, 100 μm. (B) CRTH2/CX3CR1 double-positive cells were quantitated in each model, and data are presented as number of cells per 40× field. Values are mean ± SEM with a minimum of 20 40× fields counted in each group. ****P ⩽ 0.0001. Tg = transgenic.

Null Mutation or Small-Molecule Inhibition of CRTH2 Prevents the Development of Pulmonary Fibrosis in Murine Models

We next compared collagen accumulation and fibroproliferative responses in the three murine models of lung fibrosis in the presence or absence of CRTH2 using null genetic mutations or a small-molecule inhibitor against CRTH2. These assessments were undertaken during fibroproliferative repair phases of the murine models (Day 14 for the bleomycin and TGF-β transgenic models, 3 months for the IL-13 transgenic model). When compared with the WT control subjects, bleomycin-challenged mice manifested exaggerated degrees of collagen accumulation in the lung (Figures 3A and 3B). The fibrotic response was significantly diminished in CRTH2-null mice (Figure 3A) and mice treated with the CRTH2 inhibitor CAY10471 (0.4 mg/mouse, twice a week) (Figure 3B). An additional experiment was designed to examine if CRTH2 inhibition was able to diminish lung fibrosis even when established fibrosis had occurred. CRTH2 inhibitor treatment was started 12 days after bleomycin challenge, and our results showed that it had a mild effect in established fibrosis by Day 21 (see Figure E1 in the data supplement). In the TGF-β transgenic model, TGF-β–induced collagen accumulation was significantly diminished in mice that had null mutations of CRTH2 (Figure 3C) or were treated with CAY10471 (Figure 3D). Similar findings were observed in the IL-13 transgenic model, in which IL-13–induced collagen accumulation was blocked by CRTH2 null mutation (Figure 3E) or inhibition (Figure 3F). Histological assessments with trichrome staining demonstrated consistent reduction of fibrosis in these models (Figures 3A–3F). In accord with these findings, the degrees of mRNA encoding ACTA2, α1-procollagen, and fibronectin were significantly decreased in CRTH2-null mice (see Figures E2A, E2C, E2E, E3A, E3C, E3E, E4A, E4C, and E4E) or mice treated with CAY10471 (see Figures E2B, E2D, E2F, E3B, E3D, E3F, E4B, E4D, and E4F). These studies demonstrate that CRTH2 regulates bleomycin-, TGF-β–, and IL-13–induced lung fibrosis.

Figure 3.

Null mutation or small-molecule inhibition of CRTH2 prevents the development of pulmonary fibrosis in murine models. (A) WT and CRTH2-null mice were subjected to intratracheal bleomycin administration. (B) WT mice were subjected to intratracheal bleomycin administration with or without the CRTH2 inhibitor CAY10471 treatment. (C) CRTH2-null mice were bred with TGF-β Tg overexpression mice. (D) WT and TGF-β Tg mice were treated with CAY10471 or its vehicle control. (E) CRTH2-null mice were bred with IL-13 Tg overexpression mice. (F) WT and IL-13 Tg mice were treated with CAY10471 or its vehicle control. Total lung collagen was quantified using Sircol assay on Day 14 (A–D) and 3 months after Tg induction (E and F). The noted values are the mean ± SEM of evaluations of four to seven mice in each group. Comparisons between groups were conducted using two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc test. *P ⩽ 0.05 and **P ⩽ 0.01. Scale bars, 100 μm. Rt. = right.

CRTH2 Mediates Profibrotic Macrophage Differentiation

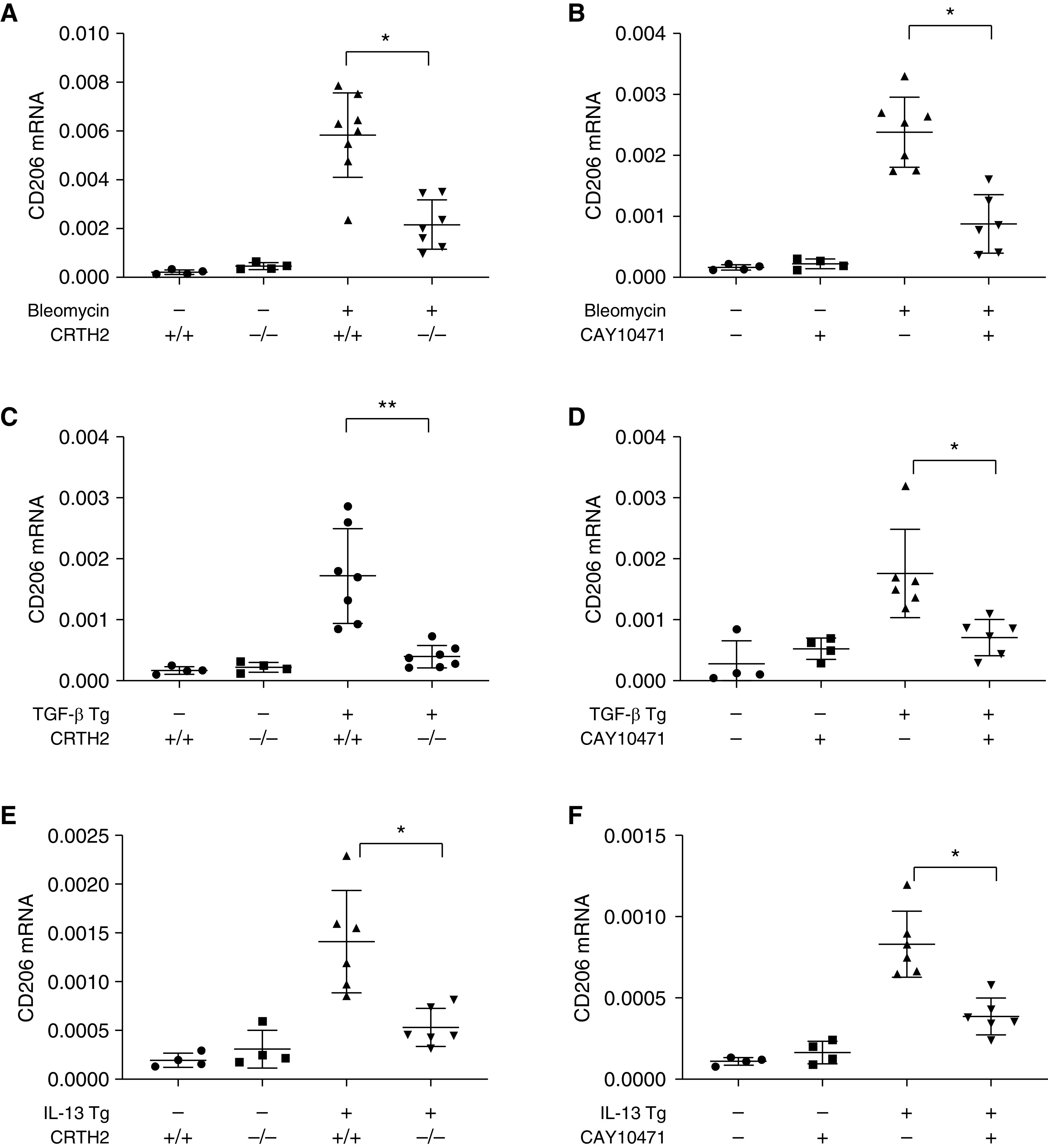

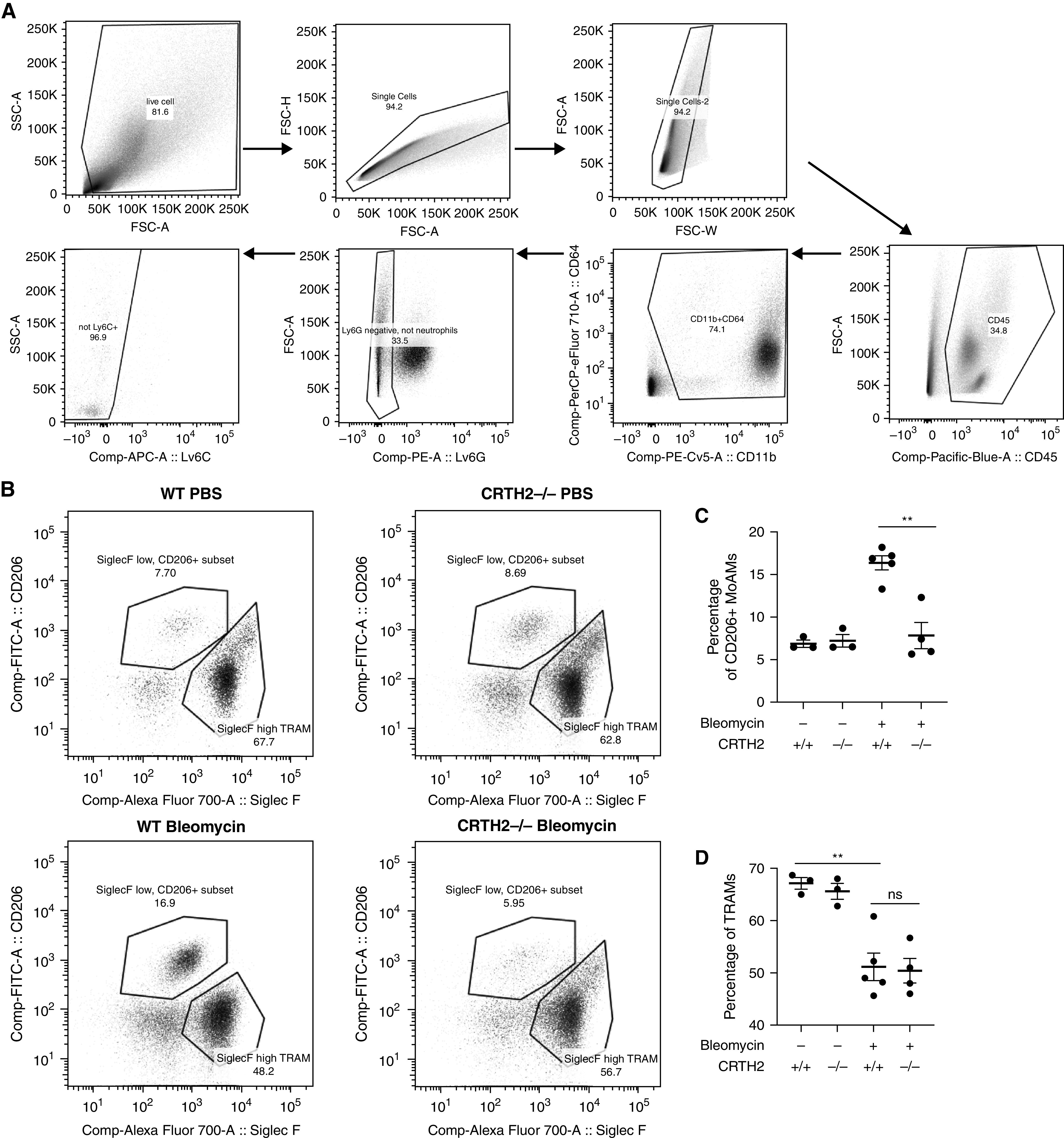

Current paradigms of pulmonary fibrosis include a potential role for alternatively activated macrophages in the immunomodulation of fibrotic responses (25). We previously demonstrated that CHI3L1 stimulates the expression of the alternative macrophage activation marker CD206 via CRTH2 (10). We next assessed the expression of CD206, a profibrotic macrophage differentiation marker, in whole-lung RNA extracts in murine models of lung fibrosis in the presence or absence of CRTH2. Our results showed that CD206 expression was induced by bleomycin challenge (see Figure E5A), TGF-β overexpression (see Figure E5B), and IL-13 overexpression (see Figure E5C). The expression of CD206 reached a peak 14 days after bleomycin challenge and TGF-β transgene induction, and at 3 months after IL-13 gene overexpression, consistent with the expression kinetics of CRTH2. Our results further showed that CRTH2-mediated CD206 expression because its mRNA expression was significantly lower in CRTH2-null mice or mice treated with CAY10471 in the bleomycin model (Figures 4A and 4B), TGF-β transgenic model (Figures 4C and 4D), and IL-13 transgenic model (Figures 4E and 4F). In addition, the expression of Arg-1, Ym-1, and FIZZ-1 was reduced in CRTH2-null mice or mice treated with CAY10471 in all three murine models of lung fibrosis (see Figures E6–E8). No compensatory change in IL-13Rα2, the other signaling receptor of CHI3L1, was observed after CRTH2 knockout or inhibition in these models (see Figure E9). Previous studies have demonstrated the major role of MoAMs, but not TRAMs, in the development of lung fibrosis (31–33), and Siglec F is a reliable marker to distinguish MoAMs versus TRAMs in the bleomycin-induced fibrosis model in flow cytometry analysis (31). In accord with these findings, FACS analysis was performed to examine CD45+CD11b+CD64+Ly6G−Ly6C− macrophage populations (Figure 5A), and these studies demonstrated that although Siglec Fhigh TRAMs were decreased in bleomycin-challenged mice, Siglec Flow MoAMs polarized to express higher concentrations of CD206 (Figures 5B–5D). Importantly, the number of CD206+Siglec Flow MoAMs was significantly lower in CRTH2-null mice compared with WT control animals in the bleomycin model (Figures 5B and 5C). These results highlight the importance of CRTH2 receptor in stimulating profibrotic MoAM differentiation in murine models, suggesting a critical role of CRTH2 in fibroproliferative repair.

Figure 4.

CRTH2 mediates profibrotic macrophage differentiation. In bleomycin model (A and B), TGF model (C and D), and IL-13 Tg model (E and F) of lung fibrosis, lungs were harvested and mRNA concentrations of CD206 were evaluated using qRT-PCR. The noted values are the mean ± SEM of evaluations of four to seven mice in each group. Comparisons between groups were conducted using two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc test. *P ⩽ 0.05 and **P ⩽ 0.01.

Figure 5.

Number of profibrotic monocyte-derived alveolar macrophages (MoAMs) was lower in CRTH2-null mice. WT and CRTH2-null mice were subjected to intratracheal bleomycin administration. Lungs were digested, and FACS analysis was used to analyze CD45+CD11b+CD64+Ly6G−Ly6C− macrophage populations. (A) Gating strategy for CD45+CD11b+CD64+Ly6G−Ly6C−Siglec Fhigh tissue-resident alveolar macrophages (TRAMs) and CD45+CD11b+CD64+Ly6G−Ly6C−Siglec Flow MoAMs. (B) Representative data of Siglec Flow MoAMs and Siglec Fhigh TRAMs on CD45+CD11b+CD64+Ly6G−Ly6C− gated alveolar macrophage population in four groups of mice. (C and D) Compared with bleomycin-challenged WT mice, CD206+ MoAMs, but not TRAMs, are decreased in bleomycin-challenged CRTH2-null mice. The noted values are the mean ± SEM of evaluations of three to five mice in each group. Comparisons between groups were conducted using two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc test. **P ⩽ 0.01. FSC-A = forward scatter area; FSC-H = forward scatter height; FSC-W = forward scatter width; ns = not significant; SSC-A = side scatter area.

CHI3L1 Concentrations Are Increased in Patients with IPF and Correlate with CD206 Expression on Primary Peripheral Blood Monocytes

We next sought to determine whether CHI3L1–CRTH2 interaction regulates CD206 expression in human monocytes. Through the Rhode Island Hospital Interstitial Lung Disease Clinic, we collected plasma and PBMCs from 23 patients with IPF and from 22 healthy, nonsmoking volunteers as control subjects. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the study subjects are shown in Figure 6A. ELISA was used to measure the concentrations of CHI3L1 in patients with IPF and control subjects. Consistent with our previously published data (26), circulating CHI3L1 concentrations were higher in patients with IPF compared with the control group (Figure 6B). We then used flow cytometry to define the percentage of CD206+ cells in the CD14+ monocyte population. As expected, at baseline, the percentage of CD206+ monocytes was higher in patients with IPF compared with control subjects (Figure 6C). Furthermore, we found moderate but statistically significant correlations between serum CHI3L1 concentrations and baseline percentages of CD206-positive populations in both control subjects (Figure 6D; P = 0.05) and patients with IPF (Figure 6E; P = 0.02), suggesting that profibrotic monocyte differentiation may depend, at least in part, on circulating CHI3L1 concentrations.

Figure 6.

CHI3L1 (chitinase 3 like 1) concentrations are increased in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), and they correlate with CD206 expression on primary peripheral blood monocytes. (A) Patient characteristics. (B) Serum CHI3L1 is increased in patients with IPF (n = 23) compared with normal control subjects (n = 22). (C) CD206+ monocytes are increased in patients with IPF compared with normal control subjects. (D) Serum CHI3L1 concentrations correlate with CD206+ monocytes in normal control subjects. (E) Serum CHI3L1 concentrations correlate with CD206+ monocytes in patients with IPF. Nonparametric data were assessed using Mann-Whitney analysis (B and C) or Spearman correlations (D and E). *P ⩽ 0.05 and **P ⩽ 0.01. FVC = forced vital capacity; N/A = not applicable.

Primary Peripheral Blood Monocytes from Patients with IPF Are Sensitive to CHI3L1–CRTH2 Pathway Manipulation

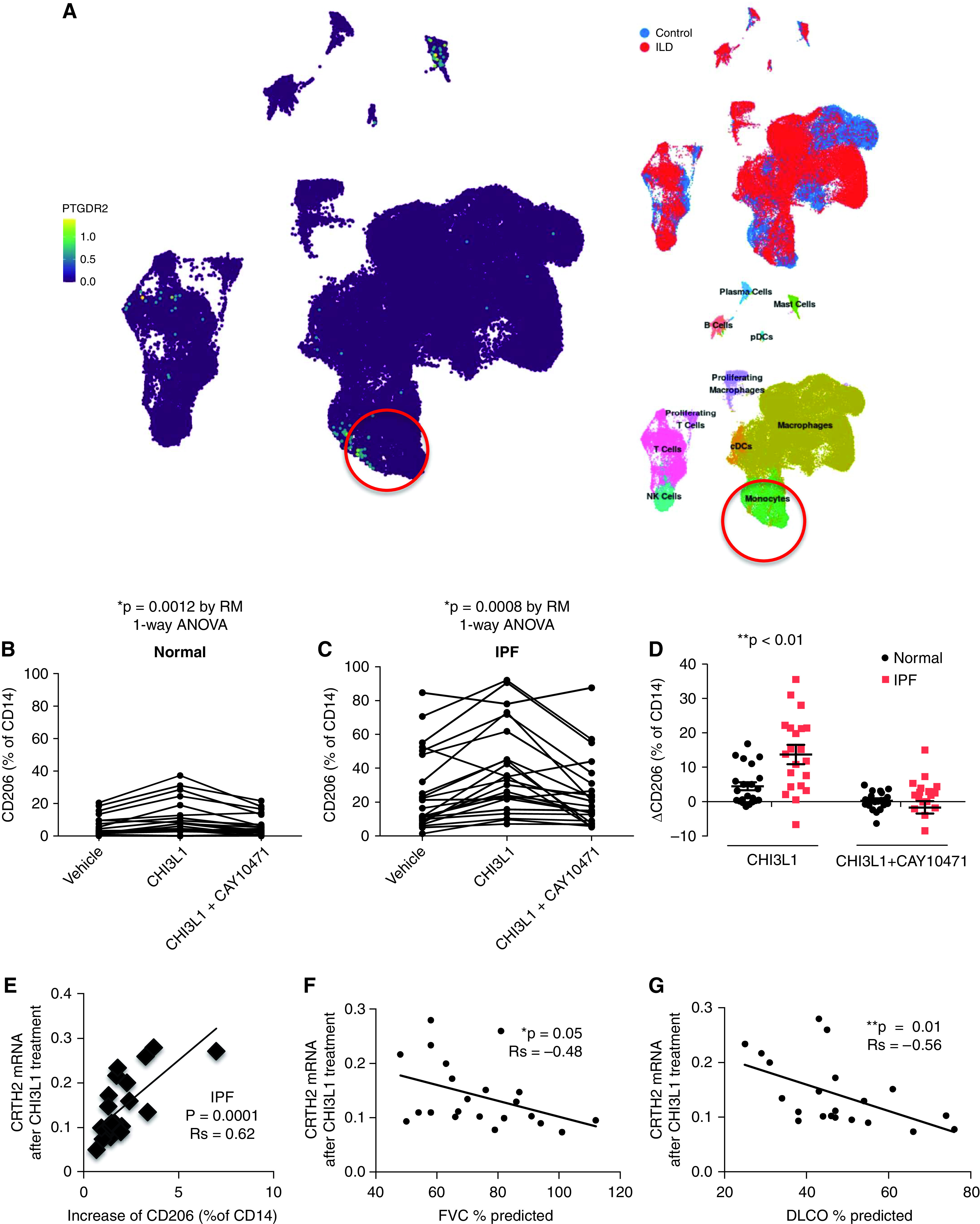

We examined the expression of CRTH2 using the publicly available Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Cell Atlas single-cell RNA sequencing data set. We found that the expression of CRTH2 was detected in subpopulations of human monocytes from the lungs of control subjects and patients with IPF (37–39) (Figure 7A). We next compared the ability of CHI3L1 to stimulate profibrotic differentiation in circulating monocytes from patients with IPF and control subjects and determine the role CRTH2 plays in these responses. In both control monocytes (Figure 7B) and IPF monocytes (Figure 7C), percentages of CD206+ cells were increased after CHI3L1 treatment in vitro. Importantly, treatment with CAY10471, a CRTH2 inhibitor, blocked these increases in CD206+ populations. Although the monocytes from both study groups showed increases in the percentage of CD206+ cells in response to CHI3L1 stimulation, the magnitude of the increase was greater in IPF cells compared with those from control subjects (Figure 7D). We then correlated the flow cytometry results of CD206 expression fold change after CHI3L1 treatment with CRTH2 mRNA expression after CHI3L1 treatment. Our results demonstrate a moderate positive correlation between CD206 fold change and CRTH2 gene expression in patients with IPF after CHI3L1 treatment (Figure 7E). Taken together, these data indicate that CHI3L1 promotes human monocyte differentiation to a profibrotic phenotype in a manner dependent on the CRTH2 receptor and that circulating monocytes from patients with IPF appear to be more sensitive to CHI3L1-induced profibrotic activation than those from individuals without IPF.

Figure 7.

Primary peripheral blood monocytes from patients with IPF are sensitive to CHI3L1–CRTH2 pathway manipulation. (A) Uniform manifold approximation and projection clustering of lung immune cells in patients with IPF and control subjects evaluated using single-cell RNA sequencing analysis. High CRTH2 (PTGDR2 [prostaglandin D2 receptor 2])–expressing cells were noted in the monocyte population, together with mast cells and a subset of T cells. PBMCs from normal individuals (B) and IPF patients (C) were stimulated with CHI3L1 (500 ng/ml) in culture, with or without CAY10471 pretreatment, and CD206+ monocyte percentages were determined using flow cytometry. (D) Changes in the percentage of CD206+CD14+ cells between IPF and control monocytes before and after CHI3L1 stimulation were calculated. Data were assessed using one-way ANOVA. (E) PBMC CRTH2 expression was measured using RT-PCR. Changes of CD206+CD14+ cells correlate with CRTH2 mRNA concentrations after CHI3L1 treatment. (F and G), CRTH2 mRNA concentrations after CHI3L1 treatment correlate with FVC (F) and DlCO (G). Data were assessed using Spearman correlations. *P ⩽ 0.05 and **P ⩽ 0.01. cDC = classical dendritic cell; NK = natural killer; PBMC = peripheral blood mononuclear cell; pDC = plasmacytoid dendritic cell; RM = repeated-measures.

The Responses of Monocytes to CHI3L1 Treatment Correlate with Baseline Lung Function but Not Clinical Outcomes

We next correlated the lung function data with circulating concentrations of CHI3L1 and CRTH2 and CD206 expression in monocytes. We found that monocyte CRTH2 mRNA expression had a low but significant negative correlative relationship with baseline forced vital capacity (Figure 7F) and a moderate negative correlative relationship with baseline DlCO (Figure 7G). We did not find significant correlations between plasma CHI3L1 or baseline monocyte CD206+ percentage and baseline lung function. During follow-up, a total of 10 patients with IPF either died or underwent lung transplantation, with a median time to death or transplantation of 13.4 months (range, 1.5–23.1 mo). Among those who were alive and had not undergone lung transplantation, the median follow-up time was 30.8 months (range, 9–47.4 mo). We did not detect significant correlations between any of the plasma or PBMC analyses and rate of lung function decline, nor did we detect significant differences in any of these analyses between patients who subsequently died or underwent lung transplantation and those who were alive at last follow-up.

Discussion

IPF affects 132,000 to 200,000 people in the United States and millions worldwide (40). Because of the large clinical impact of IPF, numerous efforts have been put into investigating the mechanisms of the injury and fibroproliferative repair processes of the disease. However, current therapeutic agents only manage the symptoms of IPF and are unable to control the development and progression of the disease (41–43). In this study, we used both murine models and human cells from patients with IPF to characterize the relationship between CHI3L1 and CRTH2 and to define the mechanisms by which they drive aberrant fibroproliferation in the lung. In the murine models, we examined profibrotic macrophage differentiation and collagen accumulation in the presence or absence of CRTH2 in a bleomycin model and two transgenic models of lung fibrosis, IL-13 and TGF-β. The results demonstrated that the elimination of CRTH2, via genetic knockout or pharmaceutical inhibition, diminished profibrotic macrophage differentiation and the amounts of collagen accumulation in all three fibrotic models. In the human studies, we analyzed plasma, PBMCs, and clinical data from 23 patients with IPF and 22 healthy control subjects. Consistent with our findings in the murine models, we found that CHI3L1 stimulated monocyte differentiation into a profibrotic M2 phenotype via its receptor CRTH2. Moreover, IPF monocytes appeared to be hyperresponsive to CHI3L1 stimulation compared with control cells. Our work has established the relevance of the CHI3L1–CRTH2 pathway in human lung fibrosis, and together with our mechanistic studies in animal models, it supports targeting this pathway as a promising therapeutic approach in IPF.

Our previous studies demonstrated that CHI3L1 mediates its fibroproliferative effects via CRTH2. CRTH2 is a G protein–coupled receptor known for binding with prostaglandin D2 and plays an important role in the pathogenesis of eosinophil-dominant allergic T-helper cell type 2 inflammation (44, 45). Recent studies indicate that CRTH2 contributes to the development of kidney fibrosis (46, 47). In accord with these findings, we demonstrate that CRTH2 plays a key role in CHI3L1-induced profibrotic monocyte/macrophage differentiation and fibroproliferation in murine lung fibrosis models. A recent study, however, showed that deficiency of CRTH2 aggravated bleomycin-induced lung inflammation and fibrosis (48). The authors speculated that exaggerated mortality, inflammation, and fibrosis are due to depleted γδT cells that express CRTH2. Further studies using CRTH2 conditional knockout animal models will be required to evaluate the role of CHI3L1–CRTH2 on γδT cells. However, it is noteworthy that the bleomycin model in that study was performed in BALB/c mice, which developed only mild to moderate pulmonary fibrosis. The genetic background of mice used in the study and the dose of bleomycin challenge might explain the discrepancy between the two different studies.

Monocytes constitute up to 30% of all PBMCs. Previous research by others demonstrated that MoAMs are likely polarized and contribute to fibrosis development (31). In addition, depleting circulating monocytes using Ccr2-null mice or via liposomal clodronate was able to diminish lung fibrosis in mice (49, 50). Consistent with these findings, CRTH2 appears to mediate the differentiation of MoAMs, but not TRAMs, at least in the bleomycin model. In our previous research using IPF PBMCs, we found that peripheral blood monocytes obtained from subjects with lung fibrosis display enhanced expression of CD206 that is typically associated with profibrotic macrophages (26, 51, 52). In the present study, we extended those studies by exploring the relationship between CRTH2 and the quantities of CD206 expression on circulating monocytes. A limitation of our human studies is the demographic differences between our IPF and control groups; specifically, compared with the control subjects, the IPF group was older and contained a larger percentage of men and White patients, which is consistent with the demographic profile of the general IPF population in the United States (42, 53, 54). Within each study group, we did not detect significant associations between the results of our plasma and PBMC analyses and age, sex, and race. Nevertheless, we cannot exclude the possibility that these demographic differences may have partially affected the responses of PBMCs to CHI3L1 as described in this study.

Overall, our studies demonstrate a critical role of the CHI3L1–CRTH2 pathway in regulating monocyte/macrophage responses. These results add new insights into targeting this pathway as a potential therapeutic strategy for major fibrotic lung diseases in which CHI3L1 and its receptor systems are dysregulated. This study also allows us to establish the sensitivity of blood monocytes in response to CHI3L1-induced profibrotic differentiation as a potential biomarker that predicts responsiveness to CHI3L1- or CRTH2-based interventions. Further longitudinal studies are warranted to further validate these findings.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge Kevin Carlson of Flow Cytometry Core, Department of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology, Brown University.

Footnotes

Supported by grant U54 GM115677 (Y.Z. and B.S.S.); National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant R01 HL146498 (Y.Z.); and National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant P20 GM103652 (Y.Z.).

Author Contributions: Conception and design: B.S.S. and Y.Z. analysis and interpretation: Y.Z., J.R., R.W., S.R., P.S., A.X.Y., M.M., D.Y., A.P., T.W., C.D., T.C., and L.T. drafting the manuscript for important intellectual content: Y.C., B.S.S., and Y.Z.

This article has a data supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2021-0504OC on May 18, 2022

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Todd NW, Luzina IG, Atamas SP. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of pulmonary fibrosis. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair . 2012;5:11. doi: 10.1186/1755-1536-5-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Crystal RG, Fulmer JD, Roberts WC, Moss ML, Line BR, Reynolds HY. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Clinical, histologic, radiographic, physiologic, scintigraphic, cytologic, and biochemical aspects. Ann Intern Med . 1976;85:769–788. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-85-6-769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Martinez FJ, Safrin S, Weycker D, Starko KM, Bradford WZ, King TE, Jr, et al. IPF Study Group The clinical course of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Ann Intern Med . 2005;142:963–967. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-12_part_1-200506210-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Woodcock HV, Maher TM. The treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. F1000Prime Rep . 2014;6:16. doi: 10.12703/P6-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sharif R. Overview of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and evidence-based guidelines. Am J Manag Care . 2017;23:S176–S182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gay SE, Kazerooni EA, Toews GB, Lynch JP, III, Gross BH, Cascade PN, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: predicting response to therapy and survival. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 1998;157:1063–1072. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.4.9703022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Karimi-Shah BA, Chowdhury BA. Forced vital capacity in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis—FDA review of pirfenidone and nintedanib. N Engl J Med . 2015;372:1189–1191. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1500526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Myllärniemi M, Kaarteenaho R. Pharmacological treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis—preclinical and clinical studies of pirfenidone, nintedanib, and N-acetylcysteine. Eur Clin Respir J . 2015;2 doi: 10.3402/ecrj.v2.26385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rodríguez-Portal JA. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib for the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: an update. Drugs R D . 2018;18:19–25. doi: 10.1007/s40268-017-0221-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhou Y, He CH, Herzog EL, Peng X, Lee CM, Nguyen TH, et al. Chitinase 3-like-1 and its receptors in Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome-associated lung disease. J Clin Invest . 2015;125:3178–3192. doi: 10.1172/JCI79792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kzhyshkowska J, Gratchev A, Goerdt S. Human chitinases and chitinase-like proteins as indicators for inflammation and cancer. Biomark Insights . 2007;2:128–146. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lee CG, Elias JA. Role of breast regression protein-39/YKL-40 in asthma and allergic responses. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res . 2010;2:20–27. doi: 10.4168/aair.2010.2.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lee CG, Hartl D, Lee GR, Koller B, Matsuura H, Da Silva CA, et al. Role of breast regression protein 39 (BRP-39)/chitinase 3-like-1 in Th2 and IL-13-induced tissue responses and apoptosis. J Exp Med . 2009;206:1149–1166. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ohno M, Bauer PO, Kida Y, Sakaguchi M, Sugahara Y, Oyama F. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of YKL-40 and its comparison with mammalian chitinase mRNAs in normal human tissues using a single standard DNA. Int J Mol Sci . 2015;16:9922–9935. doi: 10.3390/ijms16059922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yan L, Deng Y, Zhou J, Zhao H, Wang G, China HepB-Related Fibrosis Assessment Research Group Serum YKL-40 as a biomarker for liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis B patients with normal and mildly elevated ALT. Infection . 2018;46:385–393. doi: 10.1007/s15010-018-1136-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Aerts JM, van Breemen MJ, Bussink AP, Ghauharali K, Sprenger R, Boot RG, et al. Biomarkers for lysosomal storage disorders: identification and application as exemplified by chitotriosidase in Gaucher disease. Acta Paediatr . 2008;97:7–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Areshkov PO, Avdieiev SS, Balynska OV, Leroith D, Kavsan VM. Two closely related human members of chitinase-like family, CHI3L1 and CHI3L2, activate ERK1/2 in 293 and U373 cells but have the different influence on cell proliferation. Int J Biol Sci . 2012;8:39–48. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.8.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dela Cruz CS, Liu W, He CH, Jacoby A, Gornitzky A, Ma B, et al. Chitinase 3-like-1 promotes Streptococcus pneumoniae killing and augments host tolerance to lung antibacterial responses. Cell Host Microbe . 2012;12:34–46. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Recklies AD, White C, Ling H. The chitinase 3-like protein human cartilage glycoprotein 39 (HC-gp39) stimulates proliferation of human connective-tissue cells and activates both extracellular signal-regulated kinase- and protein kinase B-mediated signalling pathways. Biochem J . 2002;365:119–126. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sohn MH, Kang MJ, Matsuura H, Bhandari V, Chen NY, Lee CG, et al. The chitinase-like proteins breast regression protein-39 and YKL-40 regulate hyperoxia-induced acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2010;182:918–928. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200912-1793OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Korthagen NM, van Moorsel CH, Barlo NP, Ruven HJ, Kruit A, Heron M, et al. Serum and BALF YKL-40 levels are predictors of survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Med . 2011;105:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee CG, Da Silva CA, Dela Cruz CS, Ahangari F, Ma B, Kang MJ, et al. Role of chitin and chitinase/chitinase-like proteins in inflammation, tissue remodeling, and injury. Annu Rev Physiol . 2011;73:479–501. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-012110-142250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. He CH, Lee CG, Dela Cruz CS, Lee CM, Zhou Y, Ahangari F, et al. Chitinase 3-like 1 regulates cellular and tissue responses via IL-13 receptor α2. Cell Rep . 2013;4:830–841. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Soldano S, Pizzorni C, Paolino S, Trombetta AC, Montagna P, Brizzolara R, et al. Alternatively activated (M2) macrophage phenotype is inducible by endothelin-1 in cultured human macrophages. PLoS One . 2016;11:e0166433. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pechkovsky DV, Prasse A, Kollert F, Engel KM, Dentler J, Luttmann W, et al. Alternatively activated alveolar macrophages in pulmonary fibrosis-mediator production and intracellular signal transduction. Clin Immunol . 2010;137:89–101. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2010.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhou Y, Peng H, Sun H, Peng X, Tang C, Gan Y, et al. Chitinase 3-like 1 suppresses injury and promotes fibroproliferative responses in Mammalian lung fibrosis. Sci Transl Med . 2014;6:240ra76. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chen G, Zuo S, Tang J, Zuo C, Jia D, Liu Q, et al. Inhibition of CRTH2-mediated Th2 activation attenuates pulmonary hypertension in mice. J Exp Med . 2018;215:2175–2195. doi: 10.1084/jem.20171767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bale S, Sunkoju M, Reddy SS, Swamy V, Godugu C. Oropharyngeal aspiration of bleomycin: an alternative experimental model of pulmonary fibrosis developed in Swiss mice. Indian J Pharmacol . 2016;48:643–648. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.194859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fernandez IE, Eickelberg O. The impact of TGF-β on lung fibrosis: from targeting to biomarkers. Proc Am Thorac Soc . 2012;9:111–116. doi: 10.1513/pats.201203-023AW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moore BB, Lawson WE, Oury TD, Sisson TH, Raghavendran K, Hogaboam CM. Animal models of fibrotic lung disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol . 2013;49:167–179. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0094TR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Misharin AV, Morales-Nebreda L, Reyfman PA, Cuda CM, Walter JM, McQuattie-Pimentel AC, et al. Monocyte-derived alveolar macrophages drive lung fibrosis and persist in the lung over the life span. J Exp Med . 2017;214:2387–2404. doi: 10.1084/jem.20162152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Joshi N, Watanabe S, Verma R, Jablonski RP, Chen CI, Cheresh P, et al. A spatially restricted fibrotic niche in pulmonary fibrosis is sustained by M-CSF/M-CSFR signalling in monocyte-derived alveolar macrophages. Eur Respir J . 2020;55:1900646. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00646-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McQuattie-Pimentel AC, Ren Z, Joshi N, Watanabe S, Stoeger T, Chi M, et al. The lung microenvironment shapes a dysfunctional response of alveolar macrophages in aging. J Clin Invest . 2021;131:140299. doi: 10.1172/JCI140299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Burgess M, Wicks K, Gardasevic M, Mace KA. Cx3CR1 expression identifies distinct macrophage populations that contribute differentially to inflammation and repair. Immunohorizons . 2019;3:262–273. doi: 10.4049/immunohorizons.1900038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ishida Y, Kimura A, Nosaka M, Kuninaka Y, Hemmi H, Sasaki I, et al. Essential involvement of the CX3CL1-CX3CR1 axis in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis via regulation of fibrocyte and M2 macrophage migration. Sci Rep . 2017;7:16833. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-17007-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Greiffo FR, Viteri-Alvarez V, Frankenberger M, Dietel D, Ortega-Gomez A, Lee JS, et al. CX3CR1-fractalkine axis drives kinetic changes of monocytes in fibrotic interstitial lung diseases. Eur Respir J . 2020;55:1900460. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00460-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Adams TS, Schupp JC, Poli S, Ayaub EA, Neumark N, Ahangari F, et al. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals ectopic and aberrant lung-resident cell populations in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sci Adv . 2020;6:eaba1983. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aba1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Neumark N, Cosme C, Jr, Rose KA, Kaminski N. The idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis cell atlas. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol . 2020;319:L887–L893. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00451.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Habermann AC, Gutierrez AJ, Bui LT, Yahn SL, Winters NI, Calvi CL, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals profibrotic roles of distinct epithelial and mesenchymal lineages in pulmonary fibrosis. Sci Adv . 2020;6:eaba1972. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aba1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Raghu G, Weycker D, Edelsberg J, Bradford WZ, Oster G. Incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2006;174:810–816. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200602-163OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Borie R, Justet A, Beltramo G, Manali ED, Pradère P, Spagnolo P, et al. Pharmacological management of IPF. Respirology . 2016;21:615–625. doi: 10.1111/resp.12778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. King TE, Jr, Bradford WZ, Castro-Bernardini S, Fagan EA, Glaspole I, Glassberg MK, et al. ASCEND Study Group A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med . 2014;370:2083–2092. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Richeldi L, du Bois RM, Raghu G, Azuma A, Brown KK, Costabel U, et al. INPULSIS Trial Investigators Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med . 2014;370:2071–2082. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Satoh T, Moroi R, Aritake K, Urade Y, Kanai Y, Sumi K, et al. Prostaglandin D2 plays an essential role in chronic allergic inflammation of the skin via CRTH2 receptor. J Immunol . 2006;177:2621–2629. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.4.2621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shiraishi Y, Asano K, Nakajima T, Oguma T, Suzuki Y, Shiomi T, et al. Prostaglandin D2-induced eosinophilic airway inflammation is mediated by CRTH2 receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther . 2005;312:954–960. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.078212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Montgomery TA, Xu L, Mason S, Chinnadurai A, Lee CG, Elias JA, et al. Breast regression protein-39/chitinase 3-like 1 promotes renal fibrosis after kidney injury via activation of myofibroblasts. J Am Soc Nephrol . 2017;28:3218–3226. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2017010110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ito H, Yan X, Nagata N, Aritake K, Katsumata Y, Matsuhashi T, et al. PGD2-CRTH2 pathway promotes tubulointerstitial fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol . 2012;23:1797–1809. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012020126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ueda S, Fukunaga K, Takihara T, Shiraishi Y, Oguma T, Shiomi T, et al. Deficiency of CRTH2, a prostaglandin D2 receptor, aggravates bleomycin-induced pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol . 2019;60:289–298. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2017-0397OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gibbons MA, MacKinnon AC, Ramachandran P, Dhaliwal K, Duffin R, Phythian-Adams AT, et al. Ly6Chi monocytes direct alternatively activated profibrotic macrophage regulation of lung fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2011;184:569–581. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201010-1719OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Moore BB, Paine R, III, Christensen PJ, Moore TA, Sitterding S, Ngan R, et al. Protection from pulmonary fibrosis in the absence of CCR2 signaling. J Immunol . 2001;167:4368–4377. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.8.4368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Murray LA, Chen Q, Kramer MS, Hesson DP, Argentieri RL, Peng X, et al. TGF-beta driven lung fibrosis is macrophage dependent and blocked by serum amyloid P. Int J Biochem Cell Biol . 2011;43:154–162. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Peng X, Mathai SK, Murray LA, Russell T, Reilkoff R, Chen Q, et al. Local apoptosis promotes collagen production by monocyte-derived cells in transforming growth factor β1-induced lung fibrosis. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair . 2011;4:12. doi: 10.1186/1755-1536-4-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, Martinez FJ, Behr J, Brown KK, et al. ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Committee on Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2011;183:788–824. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2009-040GL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. King TE, Jr, Tooze JA, Schwarz MI, Brown KR, Cherniack RM. Predicting survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: scoring system and survival model. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2001;164:1171–1181. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.7.2003140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]