Abstract

Discovery of the VEXAS (vacuoles, E1 enzyme, X-linked, autoinflammatory, somatic) syndrome demonstrates that somatic mutations in haematological precursor cells can cause adult-onset, complex inflammatory disease. Unlike germline mutations, somatic mutations occur throughout the lifespan, are restricted to specific tissue types, and may play a causal role in non-heritable rheumatological diseases, especially conditions that start in later life. Improvements in sequencing technology have enabled researchers and clinicians to detect somatic mutations in various tissue types, especially blood. Understanding the relationships between cell-specific acquired mutations and inflammation is likely to yield key insights into causal factors that underlie many rheumatological diseases. The objective of this review is to detail how somatic mutations are likely to be relevant to clinicians who care for patients with rheumatological diseases, with particular focus on the pathogenetic mechanisms of the VEXAS syndrome.

Keywords: VEXAS syndrome, somatic mutations, clonal haematopoiesis, autoinflammatory disease, autoimmune disease

Rheumatology key messages.

Most genetic studies in rheumatology focus on heritable variants in the germline.

Somatic mutations are associated with an expanding list of autoimmune and autoinflammatory diseases.

VEXAS syndrome is an adult-onset, monogenic disease caused by somatic mutations in haematological cells.

Introduction

Discovery of monogenic diseases has traditionally prioritized investigation of early-onset illnesses or cases of familial aggregation of disease. Genetic mutations in the germline define an increasing list of heritable, monogenic diseases that typically manifest early in life. In contrast, emphasis on identifying genetic causes of disease in the germline may be too restrictive for rheumatological diseases that have peak incidence in adulthood, including diseases exclusively restricted to later life, such as GCA. Further, familial aggregation of disease is uncommon for most rheumatological diseases, arguing against Mendelian patterns of inheritance. In contrast to germline mutations, alterations in DNA that occur after the first zygotic division are referred to as somatic mutations. Somatic mutations increasingly occur throughout the lifespan, from early embryogenesis through adulthood. Mutations that are acquired outside of gonadal tissue are not heritable, thus familial aggregation of disease would not be expected under this paradigm. While somatic mutations have a well-established causal role in cancer, the role of somatic mutations in rheumatological disease is less clear.

To date, most genetic studies in rheumatological diseases have focused upon the effect of germline variants or common disease risk-conferring single nucleotide polymorphisms. While these studies have broadened understanding about the pathogenesis of many diseases, genetic variation in the germline may play less of a role in diseases that emerge later in life. The VEXAS (vacuoles, E1 enzyme, X-linked, autoinflammatory, somatic) syndrome is caused by somatic mutations in the gene UBA1 that result in systemic inflammation and progressive bone marrow failure, with initial clinical symptoms manifesting in the fifth decade of life or later [1]. The recent discovery of the VEXAS syndrome proves that somatic mutations can cause exclusively adult-onset, inflammatory, monogenic syndromes.

This review focuses on the role of somatic mutations within the field of rheumatology. Understanding to what extent cell-specific acquired mutations are selected for and expanded within an inflammatory environment vs those that directly contribute to inflammation is likely to yield key insights into both disease onset and progression in rheumatological diseases. As sequencing methods continue to improve, the understanding of how somatic mutations evolve throughout the lifespan of healthy individuals and the relationship of tissue-restricted mutations to disease states will expand [2, 3]. The causal mechanism of the VEXAS syndrome will be reviewed. Examples that illustrate how somatic mutations are likely to be relevant to clinicians who care for patients with rheumatological diseases will be highlighted.

Somatic mutations in healthy individuals

Genetic alterations in blood and tissue are frequent and dynamic events linked to cell replication. Exposure to mutagenic environmental and endogenous factors present continuous challenges to the genome. In some cases, mosaicism is physiological, with the most notable examples being V(D)J segment rearrangements that result in the wide diversity of the T cell receptor repertoire [4] or somatic hypermutation in proliferating germinal centre B cells [5]. Genetic analysis of tissues in healthy individuals and in disease states has revealed tissue-restricted mutations that occur across the age spectrum [2, 6]. In an interesting case study, using brain as a control tissue, ∼600 somatic variants were found in the blood of a 115-year-old healthy woman [7]. While most acquired mutations likely have a neutral effect on health, a few are deleterious, and in some instances, somatic mutations can be protective, such as revertant mosaicism in genodermatoses [8].

Clonal haematopoiesis of indeterminate potential

Somatic mutations in healthy populations have been best characterized in blood, likely because it is an easily accessible tissue source. In some healthy individuals, mutations in a set of genes associated with myeloid neoplasms have been found in clonal populations of peripheral blood cells [9–11]. Clonal haematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP) is defined by the detection of somatic mutations in at least one of these genes, typically at a variant allele fraction of ≥2% in peripheral blood, in a person without clinical evidence of cytopenia or clonal disorders [12]. The prevalence of CHIP increases with age, and the most common genes associated with CHIP are DNMT3A, TET2, JAK2 and ASXL1 [10, 11, 13] (Table 1). Most recently, CHIP has been associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and ischaemic stroke, independent of traditional risk factors such as smoking and dyslipidaemia [11, 14].

Table 1.

Clonal haematopoiesis of indeterminate potential—most commonly associated genes

| DNMT3A | TET2 | ASXL1 | JAK2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene function | Catalyses cytosine methylation | Begins cytosine demethylation | Chromatin regulator and histone modifier | Component of critical cell signalling pathway |

| Associated cytokines | Increases expression of CXCL1, CXCL2, IL-6 and CCL5 | Increased expression of IL-6 and IL-1β transcripts; elevated serum CXCL9, CCL5, IL-10 and TNFα in serum; CCL2, CCL4, IL-12 p40, RANTES, IL-6 and IL-1β may also be elevated in serum but reports are conflicting; conflicting reports on whether TET2 mutant human cells produce more IL-6 and IL-1β transcripts | No significant associations with cytokine production | Increased transcription of IL-6, IL-1β, TNFα and CCL2 |

| Associated cells | Leads to myeloid skewing | Differentiation skews to myelomonocytic and macrophage lineages; oligo- or monoclonality develops in B cell compartment | Total loss leads to pancytopenia and myeloid skewing; haematopoietic-restricted loss leads to impaired erythroid differentiation and age-dependent decreases in mature B-cells, neutrophils and monocytes; knock-in models show myeloid skewing, increased platelets and fewer erythrocytes with some reports of pancytopenia or leukopenia | Myeloid skewing, increases in erythroblasts and platelet counts |

| Clinical associations | Systemic mastocytosis, T cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, DNMT3A overgrowth syndrome | Essential thrombocythemia, polycythemia vera, primary myelofibrosis, systemic mastocytosis | Bohring–Optiz syndrome, systemic mastocytosis, chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia | Crohn’s disease, essential thrombocythemia, polycythemia vera, primary myelofibrosis, Budd–Chiari syndrome |

| Drugs to target effects of mutation | Hypermethylating agents or high dose anthracyclines | Hypomethylating agents, azacytidine, E3330 (NF-κB and STAT3 inhibitor), SHP099 (SHP2 inhibitor) | BAP1 inhibition (no clinically available drugs), PUGNAc, virinostat | Ruxolitinib, tofacitinib, baricitinib, fedratinib, givinostat |

BRCA1-associated protein-1; CCL: chemokine (C-C motif) ligand; CXCL: chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand; NF-κB: nuclear factor-κB; RANTES: regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted; SHP2: Src homology-2 containing protein tyrosine phosphatase-2; STAT3: signal transducer and activator of transcription-3.

Understanding the mechanistic consequences of CHIP will likely be relevant to rheumatologists and immunologists. In mice, loss-of-function of Dnmt3a or Tet2 mediates inflammation by activating the NLRP3 inflammasome and increasing production of key cytokines, including IL-1β and IL-6, and chemokines leading to an increase of monocyte-recruiting P-selectin within the aorta [14–17]. Notably, serum high-sensitivity CRP, which is produced by hepatocytes in response to IL-6 [18], is higher in patients with CHIP [19]. In the Canakinumab Anti-inflammatory Thrombosis Outcome Study (CANTOS) trial, targeting IL-1β reduced risk of myocardial infarction and stroke compared with placebo [20, 21]. The favourable response to canakinumab was more pronounced in patients with TET2 CHIP mutations [22]. Interestingly, patients harbouring large CHIP clones (allele fraction >10%) and the IL6R signal attenuating p. Asp358Ala variant were protected against CVD [23]. Collectively, these findings raise questions about the relationship between CHIP and inflammatory diseases, particularly in diseases affecting the vasculature.

CHIP has been studied in RA, ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV), ulcerative colitis (UC), Schnitzler syndrome (SchS), SSc and GCA [13, 24–27]. Despite years of systemic inflammation, CHIP prevalence was not increased above controls in 59 RA patients, nor did its presence correlate with disease activity [13]. In contrast, in a study of 112 AAV patients, the prevalence of CHIP mutations was found to be significantly elevated above that of age-matched healthy controls. Those with CHIP had less renal and nervous system involvement and ANCA-induced neutrophil reactive oxygen species production [24]. Compared with age-matched controls, CHIP prevalence was significantly elevated in SSc patients younger than 50 years of age, a difference that diminished with ageing, and was associated with a higher proportion of patients with serum anti-RNA polymerase III antibodies [27]. In ulcerative colitis, DNMT3A and PPM1D CHIP was significantly increased above historical controls. While CHIP status was not linked to differences in serum TNF-α, patients with DNMT3A CHIP displayed significantly higher serum IFN-γ levels [25]. In general, these studies were cross-sectional with small sample size, limiting the ability to accurately evaluate the relationship between CHIP mutations and clinical outcomes. Therefore, whether CHIP expansion is driven by inflammation or directly contributes to the pathogenesis of inflammatory conditions remains to be determined.

Examples of somatic mutations in rheumatological diseases

Over the past 40 years, the identification of genetic variation contributing to inflammatory disease has mostly focused on variation transmitted through the germline. Goodnow proposed a pathogenic mechanism similar to the development of malignancy: dictated by basal mutational rate and mutation type, an accumulation of somatic ‘hits’ in genes designed to uphold self-tolerance could ultimately lead to autoimmunity [28]. Indeed, a cascade of sequentially acquired somatic mutations within B lymphocytes has been recently reported, starting with a V(D)J recombination causing benign RF formation and ultimately leading to this B cell clone producing pathological RF driven cryoglobulinemic vasculitis [29]. However, the possibility of somatic mosaicism as a causal mechanism of inflammatory disease was further raised by the existence of mutation-negative patients that closely phenocopied established autosomal dominant monogenic diseases. The following narrative is not meant to be an exhaustive discussion of all somatically driven inflammatory diseases, but rather to illustrate a handful of clinically relevant concepts underlying somatic mosaicism. A list of rheumatological diseases associated with somatic mutations is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Inflammatory diseases associated with somatic mutations

| Disease | Gene | Chr. | Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autoimmunity | ||||

| ALPS | FAS | Chr10 | LOF | [30] |

| RALD | KRAS | Chr12 | GOF | [31, 32] |

| NRAS | Chr1 | GOF | [33] | |

| Felty syndrome | STAT3 | Chr17 | GOF | [34] |

| Autoinflammatory | ||||

| NLRP3-AID | NLRP3 | Chr1 | GOF | [35] |

| AIFEC | NLRC4 | Chr2 | GOF | [36] |

| TRAPS | TNFRSF1A | Chr12 | GOF | [37] |

| Blau syndrome | NOD2 | Chr16 | GOF | [38] |

| SAVI | TMEM173 | Chr5 | GOF | [39] |

| VEXAS | UBA1 | X | LOF | [1] |

| JAK1 GOF | JAK1 | Chr1 | GOF | [40] |

| MDS–Behçet’s | N/A | Chr8 | Trisomy | [41, 42] |

| ECD | BRAF | Chr7 | GOF | [43] |

AIFEC: autoinflammation with infantile enterocolitis; ALPS: autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome; ECD: Erdheim-Chester disease; GOF: gain-of-function; LOF: loss-of-function; MDS: myelodysplastic syndrome; NLRP3-AID: NLRP3-associated inflammatory disease; RALD: RAS-associated autoimmune leukoproliferative disease; TRAPS: tumour necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome; SAVI: STING-associated vasculopathy with onset in infancy; VEXAS: vacuoles, E1 enzyme, X-linked, autoinflammatory, somatic.

Somatic mutations phenocopy germline mutations in inflammatory diseases

Autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS) is a prototypical autoimmune disorder that is caused by both germline and somatic mutations [30]. Its inheritance is autosomal dominant with clinical features of persistent lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly secondary to abnormal lymphoid proliferation, including the hallmark increased circulating CD4−CD8− (double-negative) TCRα/β+ T lymphocytes, hypergammaglobulaemia, and evidence of autoantibodies and autoimmunity (mainly haemolytic anaemia, idiopathic thrombocytopenia and neutropenia) [44]. While germline heterozygous dominant negative mutations within proapoptotic TNFRSF6, encoding Fas/CD95, have been identified in about 65% of ALPS cases [45–47], close disease phenocopies have been found to have mutations in other proapoptotic genes, such as caspases 8 or 10 [48, 49], FasL [50], KRAS [31, 32] and NRAS [33].

Illustrating an example of a somatic mutation phenocopying its associated germline disease, focusing on germline TNFRSF6 mutation negative ALPS patients with no family history of disease, somatic TNFRSF6 mutations were first identified in fluorescence-sorted peripheral double-negative T cells [30]. Depending on the mutation, ALPS also displays incomplete clinical penetrance, with some family members remaining completely asymptomatic [51]. To help explain intrafamilial heterogeneity, a somatic ‘second hit’ model was proposed similar to malignancy and studied via genetic comparison of symptomatic ALPS patients with their older asymptomatic relatives. Sequencing DNA from sorted double-negative T cells and various other cell types revealed additional somatically acquired genetic perturbations in the other TNFRSF6 allele, perhaps causing an earlier onset of an otherwise low penetrance mutation [52]. Given that ALPS patients have a significantly higher risk for developing multiple different types of malignancies after years of disease [53], it is likely that the loss of normal apoptosis also leads to additional somatic mutational burden over time.

Somatic mutation detection method depends on mutational burden

Previously named cryopyrin-associated periodic fever syndrome (CAPS) [54], NLRP3-associatiated autoinflammatory disease (NLRP3-AID) encompasses a group of familial and sporadic autosomal dominant diseases characterized by gain-of-function mutations in NLRP3, leading to increased inflammasome activity. Their phenotypic presentation is broad [55], leading to a continuous spectrum of diseases previously named familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome (FCAS), Muckle–Wells syndrome (MWS) and neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disorder (NOMID) or chronic infantile neurological, cutaneous and articular (CINCA) syndrome. Given their milder phenotypes, FCAS and MWS tend to be familial [56], while the more severe NOMID is mostly sporadic [57]. Whereas some NLRP3 mutations are closely linked to disease severity, some are associated with more heterogeneous phenotypic presentations [58, 59], possibly due to other genetic or environmental factors.

Sporadic NLRP3-AID may be due to de novo germline or acquired somatic mutations. Considering that about 40% of NOMID patients are negative for germline NLRP3 mutations [57, 58, 60, 61], focus turned to investigation of possible somatic mutations. Early efforts [60] failed to identify mosaicism within 14 NLRP3 mutation-negative NOMID patients using traditional bidirectional Sanger sequencing, which has a lower limit of detection of around 20% somaticism [62]. Other groups have utilized more sensitive approaches to detect mosaicism. Applying knowledge of the pathophysiology of this disease, Saito et al. demonstrated enrichment of mutation-positive cells from a mixed population by sequencing cells undergoing LPS-induced cell death [63]. A large international effort employed subcloning of amplicons followed by Sanger sequencing and identified a mosaicism allele frequency of 4.2–35.8% in about 70% of NLRP3 mutation-negative NOMID patients, highlighting that ∼30% of NOMID cases are due to mosaicism [61]. Given the laborious and time-consuming process of subcloning, next-generation sequencing (NGS) should revolutionize the hunt for disease-causing mosaicism [64]. NGS can detect NLRP3 mosaicism as low as 2% [65]. However, with increased read coverage, detecting an allele frequency of about 1% or lower can be achieved [35]. In practice, these studies illustrate that outside of labour-intensive subcloning or cell sorting, conventional Sanger sequencing is usually not sensitive enough to reliably detect the presence of low-level somaticism and NGS has revolutionized the ability to rapidly detect such mutations.

A recent study examined 223 unrelated patients harbouring either somatic or germline NLRP3 mutations and found a locational segregation between these two groups, with only a small overlap [66]. The most common amino acid change in mosaic patients, p. Glu569, has only been reported once as a germline mutation in a severe case of NOMID, causing the authors to speculate that somatic mutations in NLRP3 would likely be incompatible with life if found in the germline state, and conversely, known germline NLRP3 mutations would likely cause mild or subclinical disease if somatic. Finally, a correlation between phenotypic severity and level of mosaicism was not identified.

Myeloid restricted somatic mutations may cause late-onset autoinflammatory disease

Rowczenio et al. presented a series of eight patients with late-onset periodic urticaria, fevers and progressive bilateral sensorineural hearing loss, consistent with MWS. Amplicon-based NGS done at mean coverage 3500× revealed NLPR3 mosaicism in all cases, where the mutational burden was highest in the myeloid cells [67]. Interestingly, they also reported a patient with symptom onset at age 46 and progressive disease displaying an allele frequency increasing from 5.1 to 45% over the span of 12 years. While NLRP3 somatic mutations have mostly been demonstrated in paediatric patients [61, 63, 65, 68–71], these mutations can also cause adult-onset disease [67, 72–74]. Two reports described patients in their 50 s and 60 s with symptoms consistent with MWS, both found to have low-level mosaicism mostly confined to their myeloid cells [72, 73]. The commonality among mosaic NLRP3-AID is the variant allele frequency being highest within the myeloid lineage, indicating a survival benefit, an indirectly related expansion of the myeloid compartment due to normal aging, or both [67].

Somatic mutations link inflammation and malignancy

The inflammasome-driven acquired autoinflammatory condition Schnitzler syndrome (SchS) may be considered a phenocopy of late-onset NLRP3-AID mosaicism, but SchS is usually distinguished via the presence of serum monoclonal IgMκ gammopathy [75]. Given the similarity of these conditions, efforts were made to identify NLRP3 mosaicism within SchS. However, genetic interrogations of 21 patients with classical SchS failed to identify a clear disease-causing germline or somatic mutations in NLRP3 [76]. Given that around 20% of SchS patients progress to clinically overt lymphoproliferative disorders, including Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinaemia (WM) [77], and that 90% of WM carry the MYD88 L265P gain-of-function (GoF) mutation [78], it was postulated that MYD88 GoF could underlie the pathogenesis of SchS [76]. Indeed, Pathak et al. identified MYD88 L265P in the peripheral blood of 9 of 30 patients using allele-specific oligonucleotide PCR with a lower limit of detection of 1% allele frequency [26], while excluding NLRP3 mosaicism. Predating this important finding, MYD88 GoF mutations had been identified as somatic variants in various blood malignancies [78–80], as well as a germline mutation patient with early-onset severe, episodic arthritis and rash [81], illustrating a link between autoinflammatory disease and malignancy.

Discovery of the VEXAS syndrome

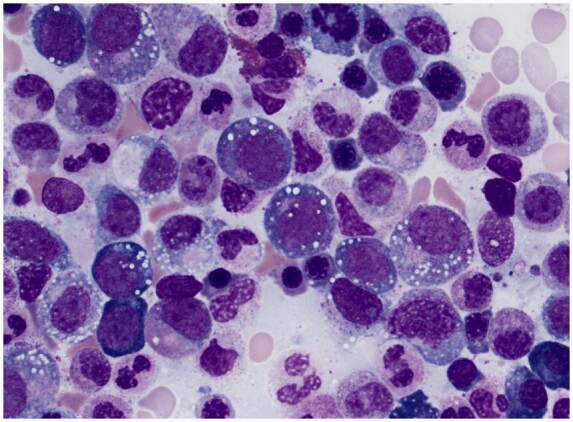

The VEXAS syndrome is a newly described monogenic disease of adulthood caused by somatic mutations in UBA1 [1]. This syndrome was identified using a genotype-first approach. WES data from 2560 individuals were screened for novel, shared, genetic variants in 841 genes related to protein ubiquitylation, which initially identified three individuals with missense mutations in codon 41 of UBA1. These individuals were older men with treatment-refractory severe inflammatory disease and progressive bone marrow failure. Detailed examination of bone marrow aspirates demonstrated characteristic cytoplasmic vacuoles in the myeloid and erythroid precursor cells (Fig. 1). Subsequent, clinical assessment for patients with severe multisystem inflammatory disease and progressive bone marrow failure led to the identification of 25 adult patients with novel missense mutations in UBA1, described in the initial report of the VEXAS syndrome [1].

Fig. 1.

Bone marrow aspirate from patient with the VEXAS syndrome

Characteristic vacuoles are present in myeloid and erythroid precursor cells. Vacuoles are sensitive for the VEXAS syndrome but are not specific for the disease. Presence of vacuoles likely reflects defects in cytoplasmic ubiquitylation related to somatic mutations in UBA1, the master switch of the ubiquitin pathway. Image courtesy of Dr Katherine Calvo, National Institutes of Health.

Several reports on the VEXAS syndrome from cohorts around the world have confirmed the stereotypical nature of the disease. Common inflammatory features include fever, chondritis, vasculitis, neutrophilic dermatosis and sterile alveolitis. Given this particular collection of systemic inflammatory features, patients with VEXAS syndrome are often clinically diagnosed with several rheumatological conditions, including relapsing polychondritis, Sweet syndrome, adult-onset Still’s disease, polyarteritis nodosa and GCA. The VEXAS syndrome is also a haematological disease, with macrocytosis being an early manifestation in almost all patients. Patients often develop cytopenias and may eventually require blood and platelet transfusions. In fact, a clinical algorithm based on male sex and mean corpuscular volume >100 and/or platelet count <200 identified patients with the VEXAS syndrome within a cohort of patients clinically diagnosed with relapsing polychondritis with near-perfect accuracy [82]. Serial bone marrow biopsies demonstrate evolving myelodysplastic syndrome or multiple myeloma. To date, all patients with the VEXAS syndrome have vacuoles in myeloid and erythroid precursor cells on bone marrow aspirates—a finding that is sensitive for the diagnosis but is not pathognomonic since similar vacuoles have been described in association with neoplasms, copper deficiency, alcoholism and other states of malnutrition [83].

Conjugation of ubiquitin to protein substrates marks them for degradation or functional modulation. Cellular ubiquitin tagging employs an enzymatic cascade, ultimately leading to ubiquitin becoming covalently bound to its target protein. In this process, the E1 enzyme activates and transfers ubiquitin to ∼40 different E2 ubiquitin ligases, which in turn deliver it to target proteins with the cooperation of over 600 substrate-specific E3 ubiquitin ligases [84]. UBA1 (formerly known as UBE1) encodes the canonical mammalian E1-ubiquitin ligase and exists as two isoforms in the physiological state: a nuclear form initiated at p. M1 and a cytoplasmic form initiated at p. M41 [85, 86]. Almost all VEXAS mutations occur at p. 41M, abolishing this alternative start site. Surprisingly, immunohistochemistry can still identify UBA1 within the cytoplasm of patient monocytes, which led to the hypothesis of an even further downstream start codon being used. Indeed, a smaller isoform, corresponding to start site p. M67 can be translated in cells from patients with VEXAS, despite this isoform showing impaired ubiquitin thioester formation. Interestingly, certain mutations within UBA1 had previously been shown to cause temperature-sensitive impairment of its enzymatic activity in several murine cell lines [87–89]. Outside of the p. M41 variant, p. Ser56Phe has been described in one patient and decreases ubiquitin thioester formation at 37°C, but not at 4°C. Another novel mutation at a splice acceptor site (c. 118-1G>C) is believed to cause aberrant RNA splice products [90]. Collectively, all VEXAS mutations described to date cause loss-of-function of normal UBA1 and occur exclusively in males, except for females with concomitant monosomy X [91–94].

The VEXAS phenotype is one of extreme inflammation, characterized by significantly elevated CRP, an interferon-induced protein signature, and increased serum neutrophil attracting IL-8. A cellular impaired ubiquitin-proteasome system leads to an accumulation of proteins, triggering an unfolded protein response as shown by increased eIF2-α phosphorylation and XBP1 splicing in patient monocytes. Given that ubiquitylation is a key regulator of the immune response [95], multiple mechanisms likely contribute to this complex inflammatory phenotype. This complexity is supported by the relative resistance to nearly all target-specific anti-rheumatic agents, while systemic glucocorticoids display the best efficacy. Given significantly elevated CRP levels and increased IL6 transcripts seen in VEXAS CD14+ monocytes, tocilizumab does ameliorate some manifestations, yet elevations of serum proinflammatory cytokines persist and it does not alter the progression of disease [96, 97]. It is conceivable, given the pervasive effects of UBA1 dysfunction, more general chemotherapies, such as the hypomethylating agent azacytidine [96] may be more beneficial than targeted therapies. JAKinibs may also be clinically effective [96]. Ultimately, bone marrow transplantation may be curative [92].

VEXAS represents a new class of conditions where somatic mutations in blood cause adult-onset inflammatory diseases with complex phenotypes that do not phenocopy established germline disease. In the context of newly discovered rheumatological diseases, the pathogenetic mechanisms underlying the VEXAS syndrome are particularly novel and compelling. Pathogenic somatic mutations acquired very early in life usually affect multiple embryonic germ layers and lead to severe, early-onset disease, as illustrated by diseases such as Sturge–Weber syndrome, Proteus syndrome, or McCune–Albright syndrome [98]. In contrast, pathogenic mutations acquired later in life usually display a restriction in affected cell populations, thus are more challenging to detect, and result in less pervasive phenotypes. The VEXAS syndrome, however, does not support this oversimplified view, because this disease can be readily detected in peripheral blood, is associated with a high burden of mutant cells, and leads to a severe clinical phenotype with onset later in life. Although VEXAS is fundamentally a disease of haematopoietic progenitor cells, mutations can be readily detected in peripheral blood due to profound clonal expansion of mutant, circulating myeloid cells, but not T or B lymphocytes, possibly due to negative selection of mutant lymphocytes within bone marrow. A high clonal burden of mutation is almost always observed at time of genetic diagnosis, and preliminary data do not show a correlation between variant allele fraction and disease duration or phenotypic severity [82]. While the exact timing of genetic onset of disease is unknown, somatic mutations in UBA1 are likely acquired later in life in patients with the VEXAS syndrome, aligning with the observation that clinical symptoms first begin in the fifth decade of life or later. The mechanisms that drive clonal expansion and the rate of expansion are currently unknown.

VEXAS joins an expanding list of monogenic inflammatory diseases caused by genetic perturbations of the ubiquitin–protease system [39, 99]. Discovery of the VEXAS syndrome will likely facilitate identification of additional rheumatological diseases caused by somatic mutations. If somatic mutations occur in blood, patients may present with an overlap of inflammatory and haematological manifestations. A clinical association between autoimmune diseases and blood dysplasia has long been established [100, 101]. Early studies screening for UBA1 mutations in these kinds of patients demonstrate that VEXAS likely explains many, but not all, of these clinical associations. Genomic interrogation for somatic mutations in genes beyond UBA1 is warranted in patients with systemic inflammation and conditions like myelodysplastic syndrome or chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia. Additionally, disease-associated somatic mutations may be restricted to specific tissue types in solid organs rather than peripheral blood and thus could be more challenging to identify in absence of biopsy material.

Haematoinflammatory diseases

The VEXAS syndrome is a prototype for a new class of diseases. We have proposed the term haematoinflammatory disease to define these conditions with the following requirements: (i) somatic mutations in blood cells; (ii) systemic inflammation; and (iii) progression towards myeloproliferative, myelodysplastic or lymphoproliferative diseases [102]. In addition to VEXAS syndrome, a few other established diseases meet this definition.

Erdheim–Chester disease (ECD) is a non-Langerhans-cell histiocytosis with systemic inflammatory features involving cortical bone, skin, lung, aorta, central nervous system and the retroperitoneum [103]. Somatic mutations in BRAF within histiocytes are causal in ∼50% of patients with ECD, and these patients may benefit from treatment with vemurafenib, a targeted agent to the BRAF protein [43, 104]. Over time, these patients can develop myeloid neoplasia [105]. These observations highlight the principle that somatic mutations can cause systemic inflammatory diseases, inform targeted treatment approaches and carry prognostic information about disease progression.

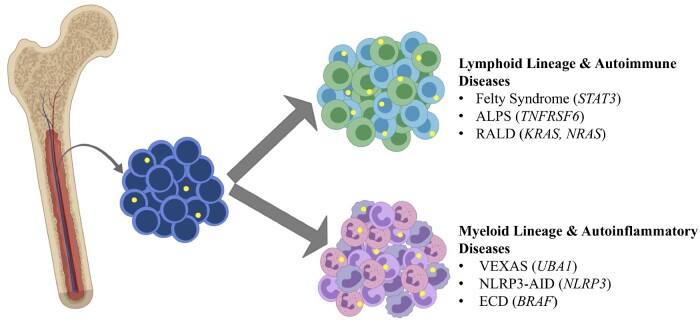

The VEXAS syndrome and ECD are disease examples of somatic mutations in blood restricted to myeloid lineages, but examples exist of somatic mutations within lymphoid lineages associated with rheumatological diseases (Fig. 2). Felty syndrome is defined by neutropenia, splenomegaly and RA. Somatic STAT3 mutations in CD8+ T cells have been described in 43% of patients with Felty syndrome [34]. These same mutations have been characterized at similar frequencies in association with large granular lymphocyte leukaemia [106]. Of note, identification of acquired mutations restricted to lymphocytes may be more challenging to detect due to relatively low abundance of these cells in peripheral blood.

Fig. 2.

Somatic mutations in bone marrow become lineage restricted to myeloid or lymphoid cell populations

Somatic mutations in bone marrow (yellow circles) can become lineage restricted to lymphoid cells in various autoimmune diseases and to myeloid cells in a range of autoinflammatory diseases. Causative genes are in parentheses and italics. ALPS: autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome; ECD: Erdheim–Chester disease; NLRP3-AID: NLRP3-associated inflammatory disease; RALD: RAS-associated autoimmune leukoproliferative disease; VEXAS: vacuoles, E1 enzyme, X-linked, autoinflammatory, somatic. Created with BioRender.com.

In up to half of patients, an autoimmune or inflammatory phenomenon may precede, occur simultaneously with, or follow the development of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) [107–109]. Trisomy 8 mosaicism (T8m) has a highly variable phenotype, depending on cells harbouring an extra chromosome 8, including skeletal defects, decreased cognitive ability and dysmorphic features. It may also be associated with haematological and neoplastic disorders, including MDS, in about 10–15% of cases [110, 111]. Behçet’s disease (BD) is a systemic autoinflammatory disease defined by recurrent aphthous stomatitis, genital ulcers, intestinal inflammation, rash, non-granulomatous uveitis and thrombosis [112], but can also be rarely complicated by MDS and interestingly, most of these patients have T8m [41]. Supporting that this syndrome may be an entity distinct from classical BD, T8m patients have mostly oral/genital ulcers, rash, fever and recalcitrant intestinal inflammation, while eye lesions are uncommon [42, 113, 114]. While trisomy 8 is insufficient to cause this phenotype, as it is commonly detected in MDS patients [115], its contribution to the BD phenotype remains unclear and is likely influenced by other acquired cytogenetic abnormalities. The role of somatic mosaicism in MDS-associated inflammatory phenomena remains an active field of investigation and could serve to illuminate the underling pathogenesis of more common immune mediated diseases.

Conclusion

Somatic mutations have been associated with an expanding range of rheumatological diseases, and knowledge about these mutations will likely be useful to clinicians in a variety of ways. Identification of somatic mutations and monitoring clonal burden over time has the potential to define new disease syndromes, novel biomarkers of disease activity, inform understanding of pathophysiology and disease prognosis, and unlock novel therapeutic approaches. Discovery of the VEXAS syndrome demonstrates the potential of considering somatic mutations as a causal mechanism of adult-onset complex inflammatory syndromes. Future efforts to identify and characterize these mutations in blood and solid organs will help in understanding the dynamic interplay between inflammation and genomic stability.

Funding: This study was supported by the Intramural Research Programs of National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS).

Disclosure statement: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Keith A Sikora, National Institutes of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Kristina V Wells, National Institutes of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Ertugrul Cagri Bolek, National Institutes of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA; Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey.

Adrianna I Jones, National Institutes of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Peter C Grayson, National Institutes of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent scientific research, and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal and Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) and execution of a Data Sharing Agreement (DSA). All data relevant to the study are included in the article.

References

- 1. Beck DB, Ferrada MA, Sikora KA. et al. Somatic mutations in UBA1 and severe adult-onset autoinflammatory disease. N Engl J Med 2020;383:2628–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Blokzijl F, de Ligt J, Jager M. et al. Tissue-specific mutation accumulation in human adult stem cells during life. Nature 2016;538:260–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mustjoki S, Young NS.. Somatic mutations in "Benign" disease. N Engl J Med 2021;384:2039–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gellert M. V(D)J recombination gets a break. Trends Genet 1992;8:408–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Neuberger MS, Milstein C.. Somatic hypermutation. Curr Opin Immunol 1995;7:248–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhang L, Dong X, Lee M. et al. Single-cell whole-genome sequencing reveals the functional landscape of somatic mutations in B lymphocytes across the human lifespan. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2019;116:9014–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Holstege H, Pfeiffer W, Sie D. et al. Somatic mutations found in the healthy blood compartment of a 115-yr-old woman demonstrate oligoclonal hematopoiesis. Genome Res 2014;24:733–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lai-Cheong JE, McGrath JA, Uitto J.. Revertant mosaicism in skin: natural gene therapy. Trends Mol Med 2011;17:140–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Busque L, Patel JP, Figueroa ME. et al. Recurrent somatic TET2 mutations in normal elderly individuals with clonal hematopoiesis. Nat Genet 2012;44:1179–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Xie M, Lu C, Wang J. et al. Age-related mutations associated with clonal hematopoietic expansion and malignancies. Nat Med 2014;20:1472–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jaiswal S, Fontanillas P, Flannick J. et al. Age-related clonal hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes. N Engl J Med 2014;371:2488–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Steensma DP, Bejar R, Jaiswal S. et al. Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential and its distinction from myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood 2015;126:9–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Savola P, Lundgren S, Keränen MAI. et al. Clonal hematopoiesis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Blood Cancer J 2018;8:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jaiswal S, Natarajan P, Silver AJ. et al. Clonal hematopoiesis and risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med 2017;377:111–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jaiswal S, Natarajan P, Ebert BL.. Clonal hematopoiesis and atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1401–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fuster JJ, MacLauchlan S, Zuriaga MA. et al. Clonal hematopoiesis associated with TET2 deficiency accelerates atherosclerosis development in mice. Science 2017;355:842–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sano S, Oshima K, Wang Y. et al. CRISPR-mediated gene editing to assess the roles of Tet2 and Dnmt3a in clonal hematopoiesis and cardiovascular disease. Circ Res 2018;123:335–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moshage HJ, Roelofs HM, van Pelt JF. et al. The effect of interleukin-1, interleukin-6 and its interrelationship on the synthesis of serum amyloid A and C-reactive protein in primary cultures of adult human hepatocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1988;155:112–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Busque L, Sun M, Buscarlet M. et al. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein is associated with clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential. Blood Adv 2020;4:2430–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ridker PM, Everett BM, Thuren T. et al. ; CANTOS Trial Group. Antiinflammatory therapy with canakinumab for atherosclerotic disease. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1119–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ridker PM, MacFadyen JG, Everett BM. et al. Relationship of C-reactive protein reduction to cardiovascular event reduction following treatment with canakinumab: a secondary analysis from the CANTOS randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2018;391:319–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Svensson EC, Madar A, Campbell CD. et al. TET2-driven clonal hematopoiesis predicts enhanced response to canakinumab in the CANTOS trial: an exploratory analysis. Circulation 2018;138(Suppl 1):A15111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bick AG, Pirruccello JP, Griffin GK. et al. Genetic interleukin 6 signaling deficiency attenuates cardiovascular risk in clonal hematopoiesis. Circulation 2020;141:124–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Arends CM, Weiss M, Christen F. et al. Clonal hematopoiesis in patients with anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Haematologica 2020;105:e264–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhang CRC, Nix D, Gregory M. et al. Inflammatory cytokines promote clonal hematopoiesis with specific mutations in ulcerative colitis patients. Exp Hematol 2019;80:36–41.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pathak S, Rowczenio DM, Owen RG. et al. Exploratory study of MYD88 L265P, rare NLRP3 variants, and clonal hematopoiesis prevalence in patients with Schnitzler syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71:2121–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ricard L, Hirsch P, Largeaud L. et al. ; MINHEMON (French Network of dysimmune disorders associated with hemopathies). Clonal haematopoiesis is increased in early onset in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2020;59:3499–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Goodnow CC. Multistep pathogenesis of autoimmune disease. Cell 2007;130:25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Singh M, Jackson KJL, Wang JJ. et al. Lymphoma driver mutations in the pathogenic evolution of an iconic human autoantibody. Cell 2020;180:878–94.e19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Holzelova E, Vonarbourg C, Stolzenberg MC. et al. Autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome with somatic Fas mutations. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1409–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Niemela JE, Lu L, Fleisher TA. et al. Somatic KRAS mutations associated with a human nonmalignant syndrome of autoimmunity and abnormal leukocyte homeostasis. Blood 2011;117:2883–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Takagi M, Shinoda K, Piao J. et al. Autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome-like disease with somatic KRAS mutation. Blood 2011;117:2887–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shiota M, Yang X, Kubokawa M. et al. Somatic mosaicism for a NRAS mutation associates with disparate clinical features in RAS-associated leukoproliferative disease: a report of two cases. J Clin Immunol 2015;35:454–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Savola P, Bruck O, Olson T. et al. Somatic STAT3 mutations in Felty syndrome: an implication for a common pathogenesis with large granular lymphocyte leukemia. Haematologica 2018;103:304–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Izawa K, Hijikata A, Tanaka N. et al. Detection of base substitution-type somatic mosaicism of the NLRP3 gene with >99.9% statistical confidence by massively parallel sequencing. DNA Res 2012;19:143–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kawasaki Y, Oda H, Ito J. et al. Identification of a high-frequency somatic NLRC4 mutation as a cause of autoinflammation by pluripotent cell-based phenotype dissection. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69:447–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rowczenio DM, Trojer H, Omoyinmi E. et al. Brief report: Association of tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome with gonosomal mosaicism of a novel 24-nucleotide TNFRSF1A deletion. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:2044–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. de Inocencio J, Mensa-Vilaro A, Tejada-Palacios P. et al. Somatic NOD2 mosaicism in Blau syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;136:484–7.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Liu Y, Jesus AA, Marrero B. et al. Activated STING in a vascular and pulmonary syndrome. N Engl J Med 2014;371:507–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gruber CN, Calis JJA, Buta S. et al. Complex autoinflammatory syndrome unveils fundamental principles of JAK1 kinase transcriptional and biochemical function. Immunity 2020;53:672–84.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ohno E, Ohtsuka E, Watanabe K. et al. Behcet's disease associated with myelodysplastic syndromes. A case report and a review of the literature. Cancer 1997;79:262–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ogawa H, Kuroda T, Inada M. et al. Intestinal Behçet's disease associated with myelodysplastic syndrome with chromosomal trisomy 8–a report of two cases and a review of the literature. Hepatogastroenterology 2001;48:416–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Haroche J, Charlotte F, Arnaud L. et al. High prevalence of BRAF V600E mutations in Erdheim-Chester disease but not in other non-Langerhans cell histiocytoses. Blood 2012;120:2700–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rieux-Laucat F. What's up in the ALPS. Curr Opin Immunol 2017;49:79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rieux-Laucat F, Le Deist F, Hivroz C. et al. Mutations in Fas associated with human lymphoproliferative syndrome and autoimmunity. Science 1995;268:1347–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Fisher GH, Rosenberg FJ, Straus SE. et al. Dominant interfering fas gene mutations impair apoptosis in a human autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome. Cell 1995;81:935–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Drappa J, Vaishnaw AK, Sullivan KE, Chu JL, Elkon KB.. Fas gene mutations in the Canale-Smith syndrome, an inherited lymphoproliferative disorder associated with autoimmunity. N Engl J Med 1996;335:1643–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wang J, Zheng L, Lobito A. et al. Inherited human Caspase 10 mutations underlie defective lymphocyte and dendritic cell apoptosis in autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome type II. Cell 1999;98:47–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chun HJ, Zheng L, Ahmad M. et al. Pleiotropic defects in lymphocyte activation caused by caspase-8 mutations lead to human immunodeficiency. Nature 2002;419:395–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Del-Rey M, Ruiz-Contreras J, Bosque A. et al. A homozygous Fas ligand gene mutation in a patient causes a new type of autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome. Blood 2006;108:1306–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rieux-Laucat F, Blachere S, Danielan S. et al. Lymphoproliferative syndrome with autoimmunity: A possible genetic basis for dominant expression of the clinical manifestations. Blood 1999;94:2575–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Magerus-Chatinet A, Neven B, Stolzenberg MC. et al. Onset of autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS) in humans as a consequence of genetic defect accumulation. J Clin Invest 2011;121:106–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Straus SE, Jaffe ES, Puck JM. et al. The development of lymphomas in families with autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome with germline Fas mutations and defective lymphocyte apoptosis. Blood 2001;98:194–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ben-Chetrit E, Gattorno M, Gul A. et al. ; Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation (PRINTO) and the AIDs Delphi study participants. Consensus proposal for taxonomy and definition of the autoinflammatory diseases (AIDs): a Delphi study. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:1558–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kuemmerle-Deschner JB. CAPS—pathogenesis, presentation and treatment of an autoinflammatory disease. Semin Immunopathol 2015;37:377–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hoffman HM, Mueller JL, Broide DH, Wanderer AA, Kolodner RD.. Mutation of a new gene encoding a putative pyrin-like protein causes familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome and Muckle-Wells syndrome. Nat Genet 2001;29:301–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Feldmann J, Prieur AM, Quartier P. et al. Chronic infantile neurological cutaneous and articular syndrome is caused by mutations in CIAS1, a gene highly expressed in polymorphonuclear cells and chondrocytes. Am J Hum Genet 2002;71:198–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Aksentijevich I, Nowak M, Mallah M. et al. De novo CIAS1 mutations, cytokine activation, and evidence for genetic heterogeneity in patients with neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease (NOMID): a new member of the expanding family of pyrin-associated autoinflammatory diseases. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:3340–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Levy R, Gerard L, Kuemmerle-Deschner J. et al. ; PRINTO and Eurofever. Phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome: a series of 136 patients from the Eurofever Registry. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:2043–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Aksentijevich I, Remmers EF, Goldbach-Mansky R, Reiff A, Kastner DL.. Mutational analysis in neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease: comment on the articles by Frenkel et al and Saito et al. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:2703–4; author reply 2704–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Tanaka N, Izawa K, Saito MK. et al. High incidence of NLRP3 somatic mosaicism in patients with chronic infantile neurologic, cutaneous, articular syndrome: results of an international multicenter collaborative study. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:3625–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Tsiatis AC, Norris-Kirby A, Rich RG. et al. Comparison of Sanger sequencing, pyrosequencing, and melting curve analysis for the detection of KRAS mutations: diagnostic and clinical implications. J Mol Diagn 2010;12:425–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Saito M, Nishikomori R, Kambe N. et al. Disease-associated CIAS1 mutations induce monocyte death, revealing low-level mosaicism in mutation-negative cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome patients. Blood 2008;111:2132–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Lindhurst MJ, Sapp JC, Teer JK. et al. A mosaic activating mutation in AKT1 associated with the Proteus syndrome. N Engl J Med 2011;365:611–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Lasiglie D, Mensa-Vilaro A, Ferrera D. et al. Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes in italian patients: evaluation of the rate of somatic NLRP3 mosaicism and phenotypic characterization. J Rheumatol 2017;44:1667–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Louvrier C, Assrawi E, El Khouri E. et al. NLRP3-associated autoinflammatory diseases: henotypic and molecular characteristics of germline versus somatic mutations. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2020;145:1254–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Rowczenio DM, Gomes SM, Arostegui JI. et al. Late-onset cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes caused by somatic NLRP3 mosaicism—UK single center experience . Front Immunol 2017;8:1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Arostegui JI, Lopez Saldana MD, Pascal M. et al. A somatic NLRP3 mutation as a cause of a sporadic case of chronic infantile neurologic, cutaneous, articular syndrome/neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease: novel evidence of the role of low-level mosaicism as the pathophysiologic mechanism underlying Mendelian inherited diseases. Arthritis Rheum 2010;62:1158–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Nakagawa K, Gonzalez-Roca E, Souto A. et al. Somatic NLRP3 mosaicism in Muckle-Wells syndrome. A genetic mechanism shared by different phenotypes of cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:603–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Omoyinmi E, Melo Gomes S, Standing A. et al. Brief report: Whole-exome sequencing revealing somatic NLRP3 mosaicism in a patient with chronic infantile neurologic, cutaneous, articular syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;66:197–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Saito M, Fujisawa A, Nishikomori R. et al. Somatic mosaicism of CIAS1 in a patient with chronic infantile neurologic, cutaneous, articular syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:3579–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Mensa-Vilaro A, Teresa Bosque M, Magri G. et al. Brief report: Late-onset cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome due to myeloid-restricted somatic NLRP3 Mosaicism. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:3035–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Zhou Q, Aksentijevich I, Wood GM. et al. Brief report: Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome caused by a myeloid-restricted somatic NLRP3 mutation. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67:2482–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Assrawi E, Louvrier C, Lepelletier C. et al. Somatic mosaic NLRP3 mutations and inflammasome activation in late-onset chronic urticaria. J Invest Dermatol 2020;140:791–8.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Gusdorf L, Lipsker D.. Schnitzler syndrome: a review. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2017;19:46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. de Koning HD. Schnitzler's syndrome: lessons from 281 cases. Clin Transl Allergy 2014;4:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Bashir M, Bettendorf B, Hariman R.. A rare but fascinating disorder: case collection of patients with Schnitzler syndrome. Case Rep Rheumatol 2018;2018:7041576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Treon SP, Xu L, Yang G. et al. MYD88 L265P somatic mutation in Waldenström's macroglobulinemia. N Engl J Med 2012;367:826–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Ngo VN, Young RM, Schmitz R. et al. Oncogenically active MYD88 mutations in human lymphoma. Nature 2011;470:115–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Puente XS, Pinyol M, Quesada V. et al. Whole-genome sequencing identifies recurrent mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nature 2011;475:101–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Sikora KA, Bennett JR, Vyncke L. et al. Germline gain-of-function myeloid differentiation primary response gene-88 (MYD88) mutation in a child with severe arthritis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018;141:1943–7.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Ferrada MA, Sikora KA, Luo Y. et al. Somatic mutations in UBA1 define a distinct subset of relapsing polychondritis patients with VEXAS syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol 2021;73:1886–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Gurnari C, Pagliuca S, Durkin L. et al. Vacuolization of hematopoietic precursors: an enigma with multiple etiologies. Blood 2021;137:3685–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Kleiger G, Mayor T.. Perilous journey: a tour of the ubiquitin–proteasome system. Trends Cell Biol 2014;24:352–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Handley-Gearhart PM, Stephen AG, Trausch-Azar JS, Ciechanover A, Schwartz AL.. Human ubiquitin-activating enzyme, E1. Indication of potential nuclear and cytoplasmic subpopulations using epitope-tagged cDNA constructs. J Biol Chem 1994;269:33171–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Stephen AG, Trausch-Azar JS, Handley-Gearhart PM, Ciechanover A, Schwartz AL.. Identification of a region within the ubiquitin-activating enzyme required for nuclear targeting and phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 1997;272:10895–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Finley D, Ciechanover A, Varshavsky A.. Thermolability of ubiquitin-activating enzyme from the mammalian cell cycle mutant ts85. Cell 1984;37:43–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Chowdary DR, Dermody JJ, Jha KK, Ozer HL.. Accumulation of p53 in a mutant cell line defective in the ubiquitin pathway. Mol Cell Biol 1994;14:1997–2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Sugaya K, Ishihara Y, Inoue S.. Nuclear localization of ubiquitin-activating enzyme Uba1 is characterized in its mammalian temperature-sensitive mutant. Genes Cells 2015;20:659–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Poulter JA, Collins JC, Cargo C. et al. Novel somatic mutations in UBA1 as a cause of VEXAS syndrome. Blood 2021;137:3676–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Barba T, Jamilloux Y, Durel CA. et al. VEXAS syndrome in a woman. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2021;60:e402–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Arlet JB, Terrier B, Kosmider O.. Mutant UBA1 and severe adult-onset autoinflammatory disease. N Engl J Med 2021;384:2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Luzzatto L, Risitano AM, Notaro R.. Mutant UBA1 and severe adult-onset autoinflammatory disease. N Engl J Med 2021;384:2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Beck DB, Grayson PC, Kastner DL.. Mutant UBA1 and severe adult-onset autoinflammatory disease. Reply. N Engl J Med 2021;384:2164–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Bhoj VG, Chen ZJ.. Ubiquitylation in innate and adaptive immunity. Nature 2009;458:430–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Bourbon E, Heiblig M, Gerfaud Valentin M. et al. Therapeutic options in VEXAS syndrome: insights from a retrospective series. Blood 2021;137:3682–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Kirino Y, Takase-Minegishi K, Tsuchida N. et al. Tocilizumab in VEXAS relapsing polychondritis: a single-center pilot study in Japan. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:1501–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Levy-Lahad E, King MC.. Hiding in plain sight—somatic mutation in human disease. N Engl J Med 2020;383:2680–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Vece TJ, Watkin LB, Nicholas S. et al. Copa syndrome: a novel autosomal dominant immune dysregulatory disease. J Clin Immunol 2016;36:377–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Mekinian A, Grignano E, Braun T. et al. Systemic inflammatory and autoimmune manifestations associated with myelodysplastic syndromes and chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia: a French multicentre retrospective study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2016;55:291–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Grignano E, Jachiet V, Fenaux P. et al. Autoimmune manifestations associated with myelodysplastic syndromes. Ann Hematol 2018;97:2015–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Grayson PC, Patel BA, Young NS.. VEXAS syndrome. Blood 2021;137:3591–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Estrada-Veras JI, O'Brien KJ, Boyd LC. et al. The clinical spectrum of Erdheim-Chester disease: an observational cohort study. Blood Adv 2017;1:357–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Haroche J, Cohen-Aubart F, Emile JF. et al. Dramatic efficacy of vemurafenib in both multisystemic and refractory Erdheim-Chester disease and Langerhans cell histiocytosis harboring the BRAF V600E mutation. Blood 2013;121:1495–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Papo M, Diamond EL, Cohen-Aubart F. et al. High prevalence of myeloid neoplasms in adults with non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood 2017;130:1007–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Fasan A, Kern W, Grossmann V. et al. STAT3 mutations are highly specific for large granular lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia 2013;27:1598–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Ganan-Gomez I, Wei Y, Starczynowski DT. et al. Deregulation of innate immune and inflammatory signaling in myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia 2015;29:1458–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Komrokji RS, Kulasekararaj A, Al Ali NH. et al. Autoimmune diseases and myelodysplastic syndromes. Am J Hematol 2016;91:E280–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Montoro J, Gallur L, Merchan B. et al. Autoimmune disorders are common in myelodysplastic syndrome patients and confer an adverse impact on outcomes. Ann Hematol 2018;97:1349–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Seghezzi L, Maserati E, Minelli A. et al. Constitutional trisomy 8 as first mutation in multistep carcinogenesis: clinical, cytogenetic, and molecular data on three cases. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 1996;17:94–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Maserati E, Aprili F, Vinante F. et al. Trisomy 8 in myelodysplasia and acute leukemia is constitutional in 15-20% of cases. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2002;33:93–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Yazici H, Seyahi E, Hatemi G, Yazici Y.. Behçet syndrome: a contemporary view. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2018;14:107–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Kawabata H, Sawaki T, Kawanami T. et al. Myelodysplastic syndrome complicated with inflammatory intestinal ulcers: significance of trisomy 8. Intern Med 2006;45:1309–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Toyonaga T, Nakase H, Matsuura M. et al. Refractoriness of intestinal Behçet's disease with myelodysplastic syndrome involving trisomy 8 to medical therapies – our case experience and review of the literature. Digestion 2013;88:217–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Jacobs RH, Cornbleet MA, Vardiman JW. et al. Prognostic implications of morphology and karyotype in primary myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood 1986;67:1765–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent scientific research, and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal and Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) and execution of a Data Sharing Agreement (DSA). All data relevant to the study are included in the article.