Abstract

The emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants with mutations in major neutralizing antibody-binding sites can affect humoral immunity induced by infection or vaccination1–6. We analysed the development of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody and T cell responses in previously infected (recovered) or uninfected (naive) individuals that received mRNA vaccines to SARS-CoV-2. While previously infected individuals sustained higher antibody titers than uninfected individuals post-vaccination, the latter reached comparable levels of neutralization responses to the ancestral strain after the second vaccine dose. T cell activation markers measured upon spike or nucleocapsid peptide in vitro stimulation showed a progressive increase after vaccination. Comprehensive analysis of plasma neutralization using 16 authentic isolates of distinct locally circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants revealed a range of reduction in the neutralization capacity associated with specific mutations in the spike gene: lineages with E484K and N501Y/T (e.g., B.1.351 and P.1) had the greatest reduction, followed by lineages with L452R (e.g., B.1.617.2). While both groups retained neutralization capacity against all variants, plasma from previously infected vaccinated individuals displayed overall better neutralization capacity when compared to plasma from uninfected individuals that also received two vaccine doses, pointing to vaccine boosters as a relevant future strategy to alleviate the impact of emerging variants on antibody neutralizing activity.

The ongoing evolution and emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) variants raise concerns about the effectiveness of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) therapies and vaccines. The mRNA-based vaccines Pfizer-BioNTech BNT162b2 and Moderna mRNA-1273 encode a stabilized full-length SARS-CoV-2 spike ectodomain derived from the Wuhan-Hu-1 genetic sequence and elicit potent neutralizing antibodies (NAbs)7,8. However, emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants with mutations in the spike (S) gene, especially in NAb binding sites, have been associated with increased transmissibility9,10 as well as neutralization resistance to mAbs, convalescent plasma, and sera from vaccinated individuals1–6.

To better understand how immune responses triggered by vaccination, and/or SARS-CoV-2 infection, fare against emerging virus variants, we assembled a cohort of mRNA-vaccinated individuals, previously infected or not, and characterized virus-specific immunologic profiles. We examined the impact of SARS-CoV-2 variants containing many different key S gene mutations in mRNA-vaccinated individuals using a comprehensive set of full-length authentic SARS-CoV-2 isolates.

Vaccine-induced antibody responses

First, to characterize SARS-CoV-2-specific adaptive immune responses post mRNA COVID vaccines (Moderna or Pfizer), forty healthcare workers (HCWs) from the Yale-New Haven Hospital (YNHH), were enrolled in this study between November 2020 and January 2021, with a total of 198 samples. We stratified the vaccinated participants based on prior exposure to SARS-CoV-2 into previously infected (recovered) or uninfected (naive) groups. Previous infection was confirmed by RT–qPCR and SARS-CoV-2 IgG ELISA. The HCWs received mRNA vaccines, either Pfizer or Moderna, and we followed them longitudinally pre- and post-vaccination (Figure 1a). Cohort demographics, vaccination status, and serostatus are summarized in Extended Data Table 1. We collected plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) sequentially in 5 time points covering a period of 98 days after the first vaccination dose. Samples were collected at baseline (prior to vaccination), 7- and 28- post first vaccination dose, and 7-, 28- and 70-days post second vaccination dose (Figure 1a). We determined antibody profiles, using both ELISA and neutralizations assays; and assessed cellular immune response, profiled by flow cytometry using frozen PBMCs.

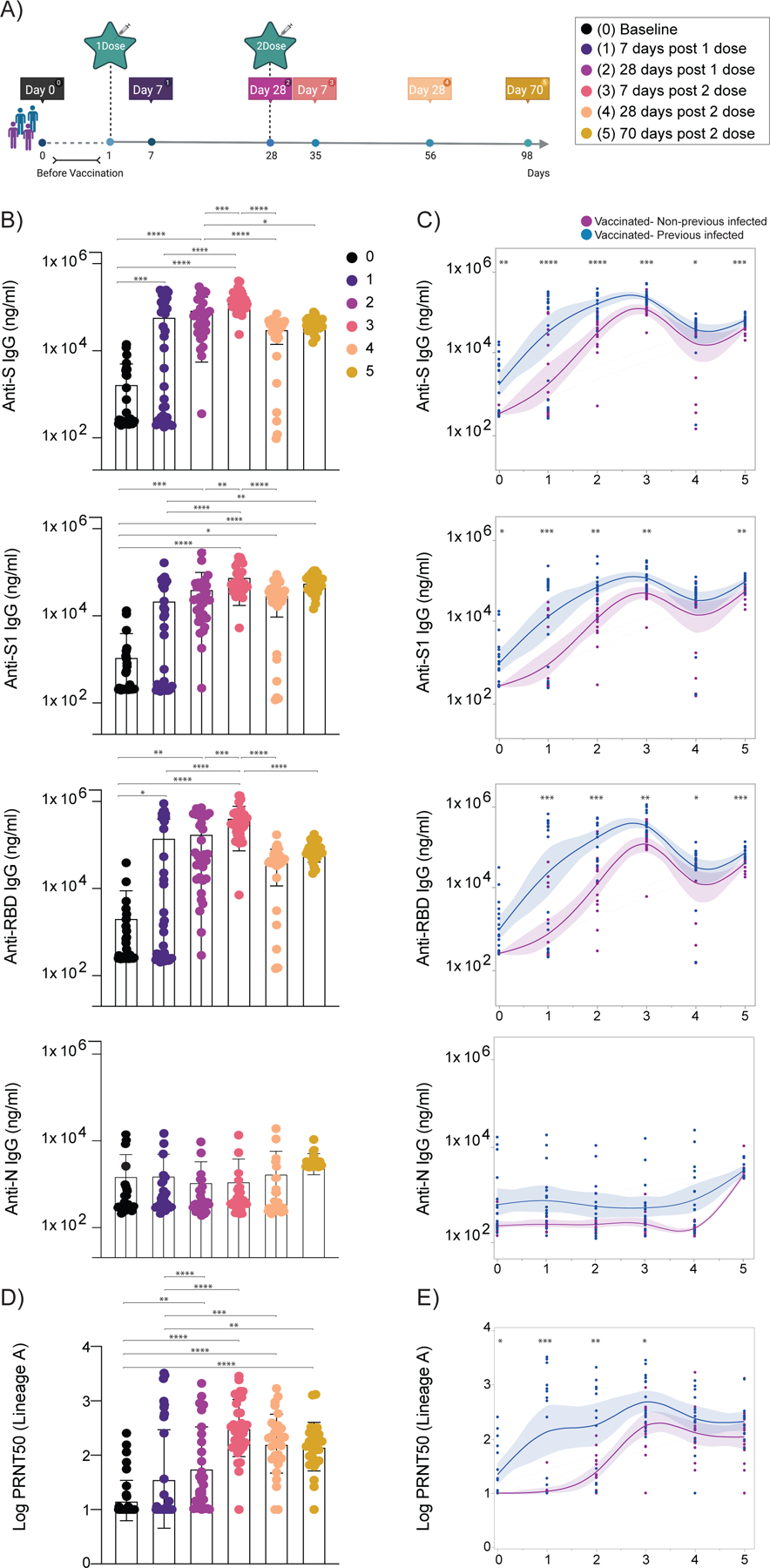

Figure 1 |. Temporal dynamics of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in vaccinated participants.

a, Cohort timeline overview indicated by days post SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination. HCW participants received 2 doses of the mRNA vaccine and plasma samples were collected as indicated. Baseline, prior to vaccination; Time point (TP) 1, 7 days post 1 dose; TP 2, 28 days post 1 dose; TP 3, 7 days post 2 dose; TP 4, 28 days post 2 dose; TP 5, 70 days post 2 dose. Participants were stratified based on previous exposure to SARS-CoV-2 (purple: Vaccinated- uninfected; blue: Vaccinated-Previously infected). b, c, Plasma reactivity to S protein, RBD and Nucleocapsid measured over time by ELISA. b, Anti-S, Anti-S1, Anti-RBD and Anti-N IgG levels. c, Anti-S, Anti-S1, Anti-RBD and Anti-N IgG comparison in vaccinated participants previously infected or not to SARS-CoV-2. S, spike. S1, spike subunit 1. RBD, receptor binding domain. N, nucleocapsid. d, e, Longitudinal neutralization assay using wild-type SARS-CoV-2, ancestral strain (WA1, USA). d, Neutralization titer (PRNT50) over time. b, d, Significance was assessed by One-way ANOVA corrected for multiple comparisons using Tukey’s method. Boxes represent mean values ± standard deviations. e, Plasma neutralization capacity between vaccinated participants previously infected or not to SARS-CoV-2. c, e, Longitudinal data plotted over time continuously. Regression lines are shown as blue (previously infected) and purple (uninfected). Lines indicate cross-sectional averages from each group with shading representing 95% CI and are coloured accordingly. Significance was accessed using unpaired two-tailed t-test. TP, vaccination time point (TP0, n=37; TP1, n=35; TP2, n=30; TP3, n=34; TP4, n=31; TP5, n=27). Each dot represents a single individual. ****p < .0001 ***p < .001 **p < .01*p < .05.

We found that mRNA vaccines induced high titers of virus-specific antibodies that declined over time, as previously reported6,11 (Figure 1b, c). After the first vaccine dose, over 97% vaccinated participants developed virus-specific IgG titers, which increased to 100% after the second dose. IgG titers against the S protein, spike subunit 1 (S1), and receptor binding domain (RBD) peaked 7 days post second vaccination dose (Figure 1 b, c). No differences were observed in antibody levels between vaccinated participants of different sexes and after stratification by age (Extended Data Figure 1a). Consistent with previous reports7,12, we found that virus-specific IgG levels were significantly higher in the previously infected vaccinated group than the uninfected vaccinated group (Extended Data Figure 1b and Figure 1c). As expected, given the absence of sequences encoding nucleocapsid (N) antigens in the mRNA vaccines, anti-N antibody titers remain stable over time for previously infected vaccinated individuals, and were not affected by vaccination in both the uninfected and previously infected groups (Figure 1 b, c). We next assessed plasma neutralization activity longitudinally against an authentic SARS-CoV-2 strain USA-WA1/2020 (lineage A), with a similar S gene amino acid sequence as Wuhan-Hu-1 used for the mRNA vaccine design, by a 50% plaque-reduction neutralization (PRNT50) assay. Neutralization activity directly correlates with anti-S and anti-RBD antibody titers, also peaking at 7 days post second dose (Figure 1 d, e). However, both groups displayed similar neutralization titers against the lineage A virus isolate at the peak of response (Figure 1 d, e). Our data indicate that despite faster and more exuberant antibody responses to viral proteins by previously infected vaccinated than uninfected vaccinated individuals, vaccination led to overall similar levels of neutralizing antibodies (NAb) after the second dose.

Vaccine-induced T cell responses

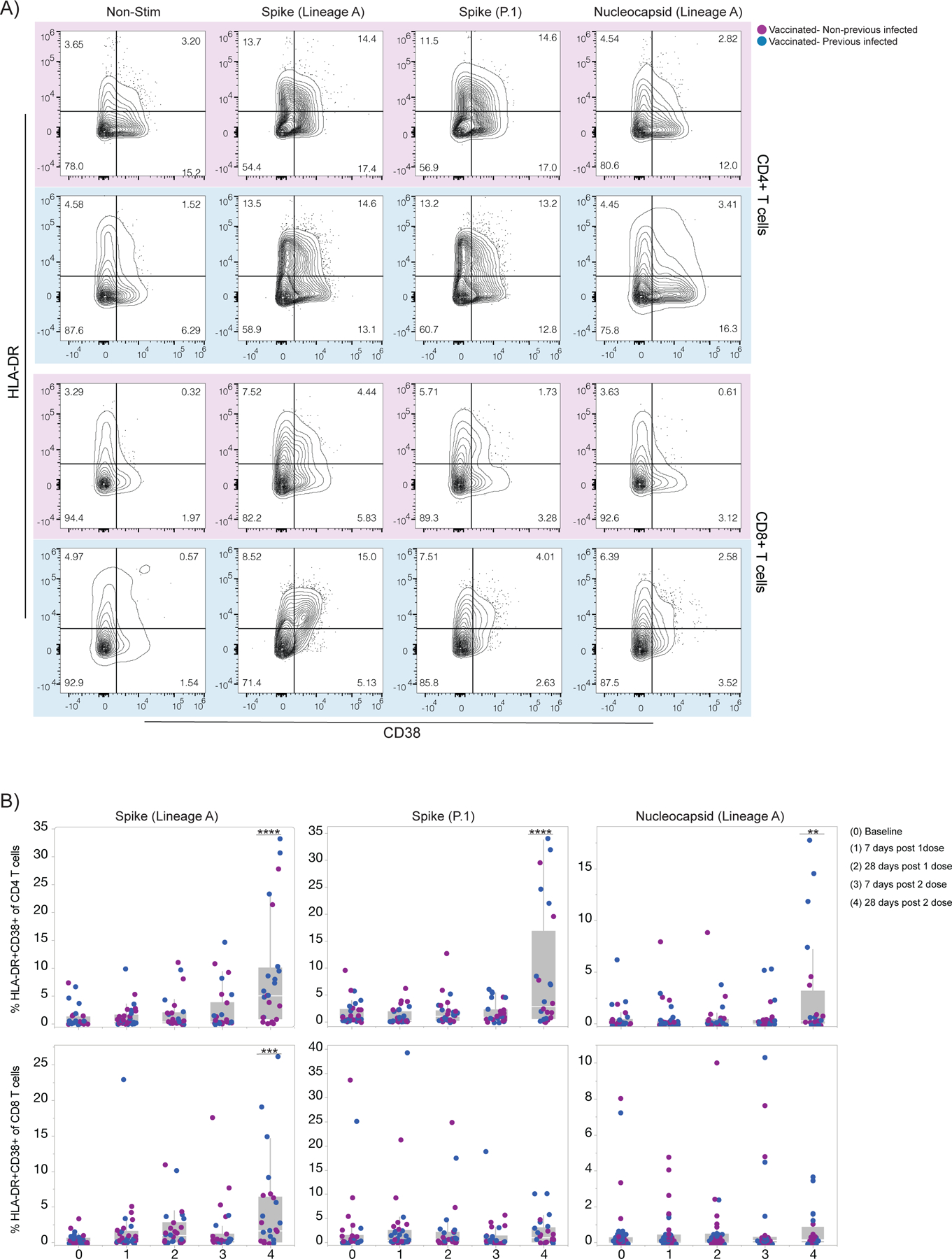

A robust T cell response has also been linked to efficient protective immunity against SARS-CoV-213–15. Hence, we next longitudinally analyzed S- and N-reactive T cells responses in vaccinated individuals. To detect low-frequency peptide-specific T cell populations, we first expanded antigen–specific T cells by stimulating PBMCs from vaccinated individuals with S and N peptide pools ex vivo for 6 days, followed by restimulation with the same peptide pools and analysis of activation markers after 12 hours. To cover the entire S protein, two peptide pools were used (S-I and S-II), while a single peptide pool was used for the nucleocapsid stimulation. S-reactive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells increased over time following vaccination (Figure 2 a, b), as evidenced by an increase in cells expressing the activation markers CD38 and HLA-DR; no differences were observed between the previously infected and uninfected vaccinated groups. Consistent with previous reports16,17, S-reactive CD4+ T cell responses were comparable among full-length lineage A and P.1 virus isolates. In contrast, S-reactive CD8+ T cell responses were only observed to lineage A, and not P.1, 28 days post second vaccination dose, suggesting that S-specific CD8 T cell responses can be affected by the mutations within the S gene of SARS-CoV-2 variants (Figure 2b). As expected, N-reactive T cells induced after stimulation with a N-peptide pool derived from the lineage A virus isolate were primarily observed in the previously infected vaccinated individuals (Figure 2b). Unexpectedly, we also observed elevated N-reactive CD4 T cells in previously infected individuals at 28 days post second dose, paralleling general activation of CD4 T cells (Figure 2b and Extended Data Figure 2a). Moreover, we observed increased levels of activated CD4+ T, Tfh, and antibody-secreting cells 28 days post vaccination booster (Extended Data Figure 2). Thus, T cell responses in vaccinated individuals display similar dynamics as antibody responses.

Figure 2 |. Temporal dynamics of anti-SARS-CoV-2 T cell immunity in vaccinated participants.

a, b, SARS-CoV-2 S-reactive CD4+ and CD8+T cells after in vitro stimulation with SARS-CoV-2 S-I and S-II peptide pools and Nucleoprotein peptides pool. a, Representative dot plots from four vaccinated individuals, 28 days post 2 vaccination dose, showing the percentage of double-positive cells expressing HLA-DR and CD38 out of CD4+T cells (top) and CD8+T cells (bottom). Individuals previously infected to SARS-CoV-2 or uninfected are indicated by blue or purple shades, respectively. b, Percentage of double-positive cells, S-reactive and N-reactive out of CD4+T cells (top) and CD8+T cells (bottom) over time post-vaccination. Individuals previously infected to SARS-CoV-2 or uninfected are indicated by blue or purple dots, respectively. Each dot represents a single individual. Significance was assessed by One-way ANOVA corrected for multiple comparisons using Dunnett’s method. Vaccination time points were compared with baseline. Stimulation values were subtracted from the respective non-stimulation condition. Boxes represent variables’ distribution with quartiles and outliers. Horizontal bars, mean values. TP, vaccination time point (TP0, n = 30; TP1, n=34; TP2, n =27; TP3, n = 27; TP4, n=24). Non-Stim, non-stimulated PBMCs. Nucleocapsid, PBMCs stimulated with SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid (N) protein pool derived from the ancestral lineage A virus, WA1, USA. Spike, PBMCs stimulated with SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) protein pool derived from the ancestral strain lineage A, WA1, USA. Spike (P.1), PBMCs stimulated with SARS-CoV-2 Spike (S) protein pool derived from the P.1 variant. ****p < .0001***p < .001 **p < .01*p < .05.

Vaccine-induced NAb against variants

To investigate potential differences in NAb escape between the SARS-CoV-2 variants, we analyzed the neutralization capacity of plasma samples from vaccinated individuals against a panel of 18 genetically distinct and authentic SARS-CoV-2 isolates. Among the isolates, 16 were from our Connecticut SARS-CoV-2 genomic surveillance program representing variants from the same geographical region as our HCW cohort18. Our variant panel includes representatives of all lineages currently classified as variants of concern (B.1.1.7, B.1.351, P.1, and B.1.617.2) as well as lineages classified as variants of interest (B.1.427, B.1.429, B.1.525, B.1.526, and B.1.617.1)19. In addition, we selected lineages with key S gene mutations (B.1.517 with N501T, and B.1 and R.1 with E484K)20, and included lineage A as a comparison (Figure 3a). To help deconvolute the effects of individual mutations, we included 4 different B.1.526 isolates (labeled as B.1.526a-d) that represent different phylogenetic clades and key S gene mutations (L452R, S477N, and E484K; Extended Data Figure 3b), two different B.1.1.7 isolates with (B.1.1.7b) and without E484K (B.1.1.7a, most common), and two B.1.351 isolates with (B.1.351b) and without L18F (B.1.351a, most common; Figure 3a & Extended Data Table 2). Except lineage A, all isolates (lineages B, P, and R) have the S gene D614G mutation located in the receptor-binding motif, which has been reported to have a modest impact on vaccine-elicited neutralization21. For each isolate we highlight key S protein amino acid differences in the antigenic regions of the amino-terminal domain (NTD), RBD-ACE2 interface, and furin cleavage site (FCS) (Figure 3a). A full list of amino acid substitutions and deletions from all genes is provided in Extended Data Table 2. We used a PRNT50 assay to determine the neutralization titers of plasma collected 28 days after the second vaccination dose.

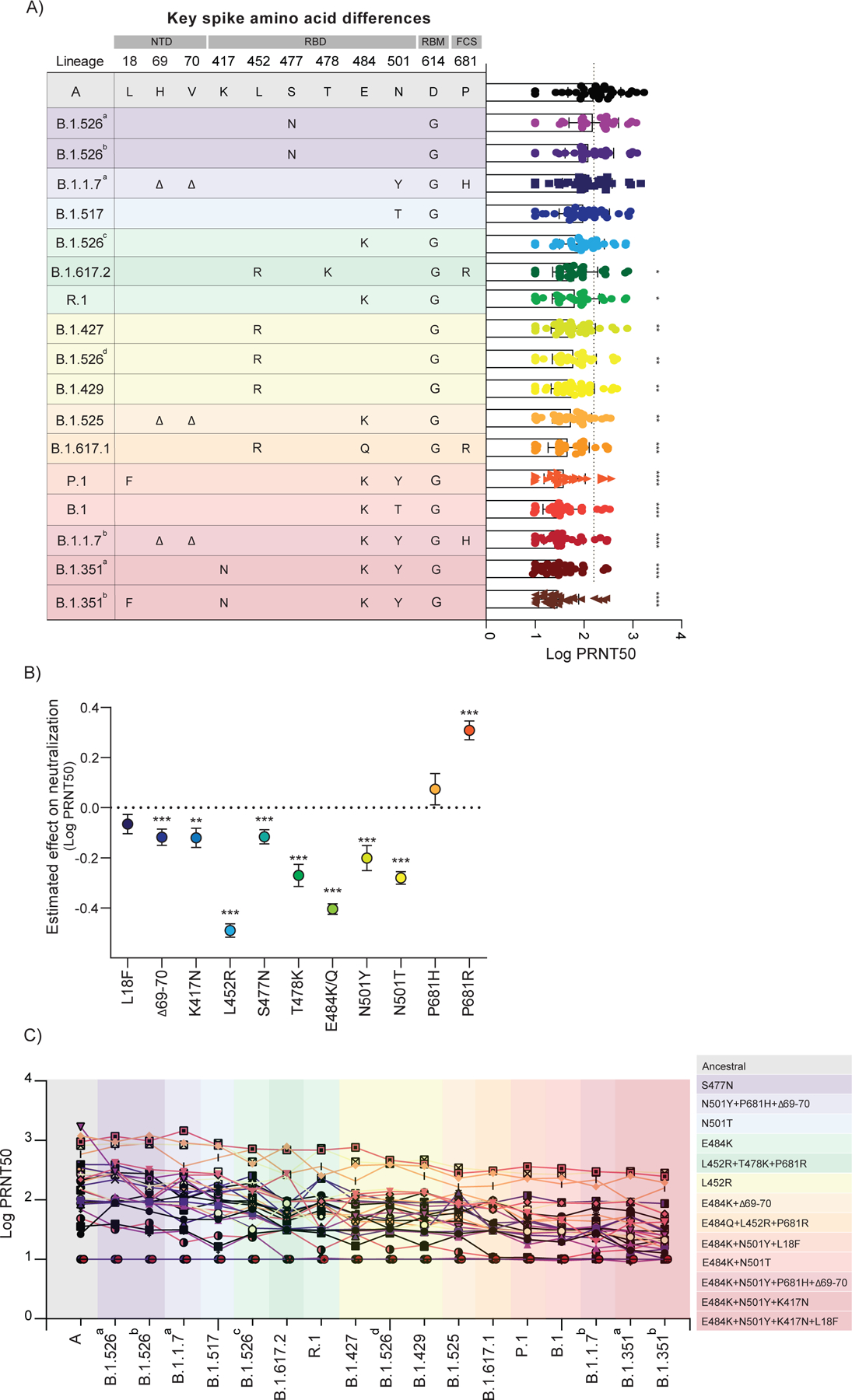

Figure 3 |. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 VOC on neutralization capacity of vaccinated participants.

a, Plasma neutralization titers against ancestral lineage A virus, (WA1, USA) and locally circulating variants. Sixteen SARS-CoV-2 variants were isolated from nasopharyngeal swabs of infected individuals and an additional B.1.351 isolate was obtained from BEI. Neutralization capacity was assessed using plasma samples from vaccinated participants, 28 days post SARS-CoV-2 second vaccination dose at the experimental sixfold serial dilutions (from 1:3 to 1:2430). a, Key spike mutations within the distinct lineages and plasma neutralization titers (PRNT50). Spike mutations are arranged across columns and rows represent lineages. Significance was assessed by One-way ANOVA corrected for multiple comparisons using Dunnett’s method. Neutralization capacity of variants was compared to neutralization capacity against the ancestral strain. Boxes represent mean values ± standard deviations. Dotted line indicates the mean value of PRNT50 to ancestral strain. n=32. b, Estimated effect of individual mutations on plasma neutralization titers. Neutralization estimates (Log PRNT50) and significance were tested with a linear mixed model with subject-level random effects. Dots represent the ratio of linear mixed model coefficients + intercept to the intercept alone, and error bars represent the standard error. ****p < .0001***p < .001 **p < .01*p < .05. c, Individual trajectories of plasma neutralization titers (PRNT50). Each line represents a single individual. n=32. Dotted line indicates the mean value of PRNT50 to ancestral strain of previously infected individuals, prior to vaccination (baseline). Variants were grouped giving specific-spike mutations and are coloured accordingly. ****p < .0001 ***p < .001 **p < .01*p < .05. NTD, amino-terminal domain. RBD, receptor-binding domain. RBM, receptor-binding motif. FCS, furin cleavage site.

When comparing vaccine-induced neutralization against the different isolates in comparison to the lineage A virus isolate, we observed significantly reduced PRNT50 titers for 12 out of the 17 isolates, and the rank order of reduced neutralization mostly clustered by key S gene amino acid differences (Figure 3a). Virus isolates with both the E484K and N501Y (or N501T) mutations (B.1.351b, B.1.351a, B.1.1.7b, B.1, and P.1) reduced neutralization the most (4.6–6.0 fold decrease in PRNT50 titers). Virus isolates with the L452R mutation (B.1.617.1, B.1.429, B.1.526b, B.1.427, and B.1.617.2) were in the next grouping of decreased neutralization (2.5–4.1 fold decrease), which partially overlapped with isolates with E484K but without N501Y/T (B.1.525, R.1, and B.1.526c; 2.0–3.8 fold decrease). To further assess the impact of individual mutations, we constructed a linear mixed model with subject-level random effects to account for the differences in neutralization outcome (log transformed PRNT50 titers) by each individual mutation as compared to lineage A (with no mutation; Figure 3b). From our model, we estimated that 8 of the 11 key S gene mutations that we investigated had significant negative effects on neutralization, and that L452R (2.8 fold decrease in PRNT50 titers [mean]; p< 2e-16) and E484K/Q (2.0 fold decrease; p< 2e-16) had the greatest individual effects. As combinations of mutations can alter effects differently than the added value of each individually (i.e. epistatic interactions), we also created a second linear mixed model that controlled for all of the individual mutations in the first model as well as three common combinations of key S gene mutations found in our isolates: ΔH69/V70 and E484K, L452R and P681R, and E484K and N501Y. These combinations of mutations allowed us to assess if the contribution of mutations together is synergistic, antagonistic, or neither. Our model suggests that the ΔH69/V70 and E484K combination was synergistic (i.e. decreased neutralization more than the added effects of each; β=−0.182; p=0.005), L452R and P681R was antagonistic (i.e. decreased neutralization less than the added effects of each; β=0.228; p=0.003), and E484K and N501Y was neither (i.e. neutralization likely the sum of the individual effects of each; β=0.060; p=0.248). Thus, from our large panel of virus isolates, we find that virus genotype plays an important role in vaccine-induced neutralization, with L452R likely having the largest individual impact, but the added effects of E484K and N501Y make viruses with this combination perhaps the most concerning for vaccines.

Although virus-specific factors may play a significant role in neutralization, differences in neutralization activity between individual vaccinated HCWs were much larger (up to ~2 log PRNT50 titers) than differences among virus isolates (mostly <1 log; Figure 3a). By tracking PRNT50 titers from each HCW, we found the vaccinated individuals with high neutralization activity for the lineage A virus isolate are typically on the higher end of neutralization for all variants (Figure 3c). Moreover, two vaccinated HCWs did not develop neutralizing antibodies against any of the virus isolates, including lineage A (Figure 3c), despite the production of virus-specific antibodies (Figure 1a, b).

Impact of previous infection on NAb

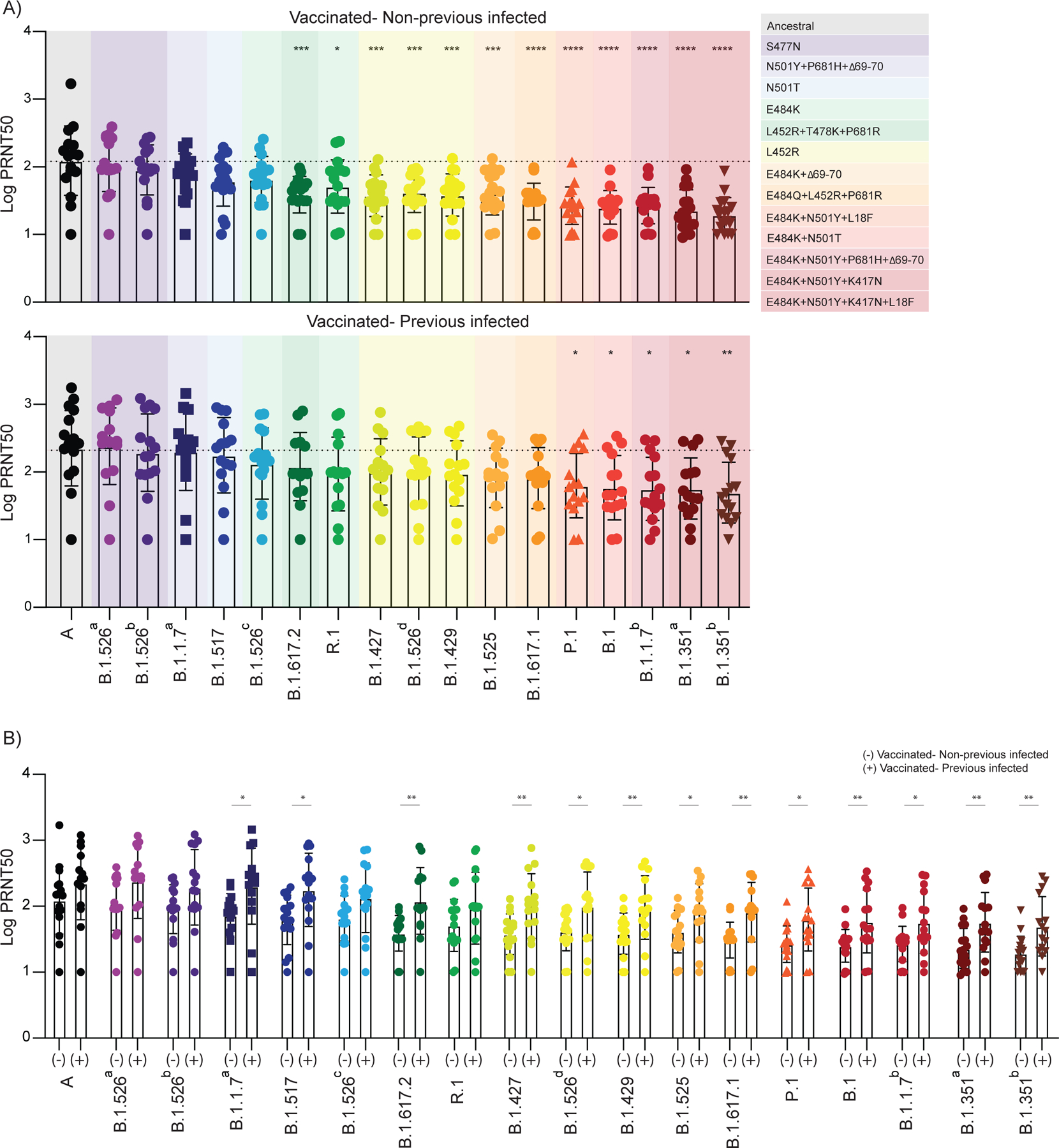

To further understand the underlying factors that determine levels of neutralization activity, we separated individuals by their SARS-CoV-2 previous infection status (i.e. previously infected vs uninfected) and determined their neutralization titers to our panel of SARS-CoV-2 isolates. Previous infection occurred between April and December 2020, and for 3 out of 15 HCWs we were able to identify the lineage of the virus, which were all B.1.3. While the rank order of virus isolates impacting neutralization remained mostly the same, we found that the plasma from previously infected vaccinated individuals generally had higher PRNT50 titers against the panel of SARS-CoV-2 isolates than uninfected vaccinated individuals (Figure 4a, b). With the exception of virus isolates from lineages A, B.1.526a-c, and R.1, which affected neutralization the least, all other assayed isolates had a significantly higher NAb response in previously infected vaccinated individuals (Figure 4b); only virus isolates with the E484K and N501Y/T mutations still significantly reduced neutralization (Figure 4a). For example, the lineage B.1.351b isolate (E484K and N501Y) decreased neutralization titers by 13.2 fold (compared to lineage A) in uninfected and by 3.7 fold in previously infected vaccinated individuals, whereas B.1.617.2 (L452R) went from 6.9 to 1.5 and B.1.1.7a (N501Y) went from 3.4 to 0.8 fold decrease in uninfected to infected, respectively (Figure 4a). Thus, our data suggests that plasma neutralization activity against SARS-CoV-2 variants is improved in vaccinated individuals previously infected with the virus.

Figure 4 |. Neutralizing activity comparison in vaccinated healthcare workers previously infected or not to SARS-CoV-2.

a-b,Plasma neutralization titers against ancestral lineage A virus, (WA1, USA) and locally circulating variants of concern or interest, and other lineages. Sixteen SARS-CoV-2 variants were isolated from nasopharyngeal swabs of infected individuals and an additional B.1.351 isolate was obtained from BEI. Neutralization capacity was accessed using plasma samples from vaccinated participants, 28 days post SARS-CoV-2 second vaccination dose at the experimental sixfold serial dilutions (from 1:3 to 1:2430). a, b, Neutralization capacity between vaccinated participants previously infected or not to SARS-CoV-2. a, Neutralization titer among vaccinated individuals. Significance was assessed by One-way ANOVA corrected for multiple comparisons using Dunnett’s method. Neutralization capacity to the variants was compared to neutralization capacity against the ancestral strain. Boxes represent mean values ± standard deviations. Dotted line indicates the mean value of PRNT50 to ancestral strain. Variants were grouped giving specific-spike mutations and are coloured accordingly. ****p < .0001 ***p < .001 **p < .01*p < .05. b, Neutralization titer comparison among vaccinated participants previously infected or not to SARS-CoV-2. Significance was accessed using unpaired two-tailed t-test. Boxes represent mean values ± standard deviations. (−) Vaccinated-uninfected, n=17; (+) Vaccinated-Previously infected, n=15. Each dot represents a single individual **p < .01*p < .05.

Discussion

Human NAbs against SARS-CoV-2 can be categorized as belonging to four classes on the basis of their target regions on the RBD. Although the RBD is immunodominant, there is evidence for a substantial role of other spike regions in antigenicity, most notably the NTD supersite22–24. These antibodies target epitopes that are closely associated with NTD and RBD residues L18 and ΔH69/V70, and K417, L452, S477, T478, E484 and N501. Previous studies using pseudovirus constructs reported a significant impact of single S amino acid substitutions, including S477N and E484K located at the RBD-ACE2 interface, in the neutralization activity of plasma from vaccinated individuals1–5,25.

Using a large panel of genetically diverse authentic SARS-CoV-2 isolates, we found that lineages with E484K and N501Y/T led to the most severe decreases in mRNA vaccine-induced neutralization (>10 fold in previously uninfected vaccinated individuals). This group includes B.1.351 (Beta) and P.1 (Gamma), further supporting their importance in regards to vaccines. Interestingly, we also found that a generic lineage B.1 isolate with E484K and N501T, and a rare B.1.1.7 (Alpha) isolate with E484K (also with the common N501Y mutation) have similar impacts on neutralization as B.1.351 and P.1. While the combinations of mutations in the B.1 and B.1.1.7 with E484K isolates likely do not increase transmissibility, the additive effects of these two mutations supports that surveillance programs should track all viruses with E484K and N501Y/T in addition to variants of concern/interest.

While we estimate that the L452R mutation has the greatest individual impact on neutralization, lineages with this mutation, including B.1.617.2 (Delta), are less concerning for NAb escape than the E484K-N501Y/T combination. From our data, we expect that most fully vaccinated individuals will be protected against B.1.617.2, and that the rise in vaccine-breakthroughs associated with this variant are more likely associated with its high transmissibility26–29.

The discrepancies of our results compared to other studies, including the study by Stamatatos and coworkers6, may point to the importance of using fully intact authentic virus for neutralization assays to detect effects of epistasis among virus mutations on neutralization assays. Nevertheless, it remains possible that additional factors also contribute to some of the discrepancies between our observations and those of previous studies, including the presence of additional mutations in the membrane and envelope, as well as the composition of our cohorts, predominantly young Caucasian women. Discrepancies between cohorts could also account for subtle differences in T cell responses observed in our study versus the ones recently reported by Alter et al., and Tarke et al. While we observed decreased cross-reactivity of S-reactive CD8+ T cells against P.1 S peptides, the above studies found T cell responses are largely preserved against variants16,17. In addition to cohort composition, we used overlapping peptide pools in our assays and it remains possible that our T cells assay failed to detect underrepresented T cell clones impacted by variant sequences when sampled in the presence of the majority of conserved peptides. Furthermore, Alter et al. used an AdV1.26 vaccine16, while ours and Tarke et al. used mRNA vaccines17. Overall, our data point to a necessity of active monitoring of T cell reactivity in the context of SARS-CoV-2 evolution.

The magnitude of the antibody titers in COVID-19 patients following natural infection has been directly correlated with length of infection and severity30. Here, we found that previously infected vaccinated individuals display an increased resilience in antibody responses against both “single” and combination of substitutions in the RBD region, which otherwise severely decreased neutralization activity of uninfected vaccinated individuals. Our observations of the impact of pre-existing immunity in vaccinated individuals on their ability to neutralize variants could be explained by the time window between the initial exposure (infection) and vaccination. Moreover, based on timing of previous infection (before the emergence of tested variants) and confirmation by sequencing (3 previous infections with B.1.3), we believe that the virus lineage of the infection likely did not have a major impact on our findings. Our observations provide an important rationale for worldwide efforts in characterizing the contribution of pre-existing SARS-CoV-2 immunity to the outcome of various vaccination strategies. Along with recently introduced serological tests31, such studies could inform evidence-based risk evaluation, patient monitoring, adaptation of containment methods and vaccine development and deployment. Finally, these findings suggest that an additional third vaccination dose may be beneficial to confer higher protection against SARS-CoV-2 lineages such as B.1.351 and P.1.

METHODS

Ethics statement

This study was approved by Yale Human Research Protection Program Institutional Review Board (IRB Protocol ID 2000028924). Informed consent was obtained from all enrolled vaccinated HCWs. The Institutional Review Board from the Yale University Human Research Protection Program determined that the RT-qPCR testing and sequencing of de-identified remnant COVID-19 clinical samples conducted in this study is not research involving human subjects (IRB Protocol ID: 2000028599).

Healthcare worker volunteers

Forty health care worker volunteers from the YNHH were enrolled and included in this study. The volunteers received the mRNA vaccine (Moderna or Pfizer) between November 2020 and January 2021. Vaccinated donors were stratified in two major groups, previously infected with SARS-CoV-2 (recovered) on uninfected (naive), confirmed by RT-qPCR (10 April 2020 – 31 December 2020) and serology (2 April 2020 – 11 March 2020). None of the participants experienced serious adverse effects after vaccination. HCWs were followed serially post-vaccination. Plasma and PBMCs samples were collected at baseline (previous to vaccination), 7- and 28- post first vaccination dose, and 7-, 28- and 70-days post second vaccination dose. Demographic information was aggregated through a systematic review of the EHR and was used to construct Extended Data Table 1. The clinical data were collected using EPIC EHR May 2020 and REDCap 9.3.6 software. Blood acquisition was performed and recorded by a separate team. Vaccinated HCW’s clinical information and time points of collection information was not available until after processing and analyzing raw data by flow cytometry and ELISA. ELISA, neutralizations, and flow cytometry analyses were blinded.

Isolation of plasma and PBMCs

Whole blood was collected in heparinized CPT blood vacutainers (BD; # BDAM362780) and kept on gentle agitation until processing. All blood was processed on the day of collection in a single step standardised method. Plasma samples were collected after centrifugation of whole blood at 600 g for 20 min at room temperature (RT) without brake. The undiluted plasma was transferred to 15-ml polypropylene conical tubes, and aliquoted and stored at −80 °C for subsequent analysis. The PBMC layer was isolated according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were washed twice with PBS before counting. Pelleted cells were briefly treated with ACK lysis buffer for 2 min and then counted. Percentage viability was estimated using standard Trypan blue staining and an automated cell counter (Thermo-Fisher, #AMQAX1000). PBMCs were stored at −80 °C for subsequent analysis.

SARS-CoV-2 specific-antibody measurements

ELISAs were performed as previously described32. In short, Triton X-100 and RNase A were added to serum samples at final concentrations of 0.5% and 0.5mg/ml respectively and incubated at room temperature (RT) for 30 minutes before use, to reduce risk from any potential virus in serum. 96-well MaxiSorp plates (Thermo Scientific #442404) were coated with 50 μl/well of recombinant SARS Cov-2 STotal (ACROBiosystems #SPN-C52H9–100ug), S1 (ACROBiosystems #S1N-C52H3–100ug), RBD (ACROBiosystems #SPD-C52H3–100ug) and Nucleocapsid protein (ACROBiosystems #NUN-C5227–100ug) at a concentration of 2 μg/ml in PBS and were incubated overnight at 4°C. The coating buffer was removed, and plates were incubated for 1 h at RT with 200 μl of blocking solution (PBS with 0.1% Tween-20, 3% milk powder). Plasma was diluted serially 1:100, 1:200, 1:400 and 1:800 in dilution solution (PBS with 0.1% Tween-20, 1% milk powder) and 100 μl of diluted serum was added for two hours at RT. Human Anti-Spike (SARS-CoV-2 Human Anti-Spike (AM006415) (Active Motif #91351) and anti-nucleocapsid SARS-CoV-2 Human anti-Nucleocapsid (1A6) (Active Motif # MA5–35941) were serially diluted to generate a standard curve. Plates were washed three times with PBS-T (PBS with 0.1% Tween-20) and 50 μl of HRP anti-Human IgG Antibody (GenScript #A00166, 1:5,000) diluted in dilution solution added to each well. After 1 h of incubation at RT, plates were washed six times with PBS-T. Plates were developed with 100 μl of TMB Substrate Reagent Set (BD Biosciences #555214) and the reaction was stopped after 5 min by the addition of 2 N sulfuric acid. Plates were then read at a wavelength of 450 nm and 570nm.

T cells stimulation

For the in vitro stimulation, PBMCs were stimulated with HLA class I and HLA-DR peptide pools at the concentration of 1–10 μg/ml per peptide and cultured for 7 days. On day 0, PBMCs were thawed, counted, and plated in a total of 5–8×105 cells per well in 200ul of RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco) supplemented with 1% sodium pyruvate (NEAA), 100 U/ml penicillin /streptomycin (Biochrom) and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37°C and 5% CO2. On day 1, cells were washed and the stimulation was performed with: PepMix SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein pool 1 and pool 2 (GenScript), PepMix P.1 SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein pool 1 and pool 2 (JPT) and PepMix SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid protein (JPT). Stimulation controls were performed with PBS (unstimulated). Peptide pools were used at 1 μg/ml per peptide. Incubation was performed at 37 °C, 5% CO2 for 6 days. On day 6, cells were restimulated with 10ug/ml per peptide and subsequently incubated for 12h, being the last 6 h in the presence of 10 μg/ml brefeldin A (Sigma-Aldrich). Following this incubation, cells were washed with PBS 2 mM EDTA and prepared for analysis by flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry

Antibody clones and vendors were as follows: BB515 anti-hHLA-DR (G46–6) (1:400) (BD Biosciences), BV605 anti-hCD3 (UCHT1) (1:300) (BioLegend), BV785 anti-hCD19 (SJ25C1) (1:300) (BD Biosciences), BV785 anti-hCD4 (SK3) (1:200) (BioLegend), APCFire750 or BV711 anti-hCD8 (SK1) (1:200) (BioLegend), AlexaFluor 700 anti-hCD45RA (HI100) (1:200) (BD Biosciences), PE anti-hPD1 (EH12.2H7) (1:200) (BioLegend), APC or PE-CF594 anti-hTIM3 (F38–2E2) (1:50) (BioLegend), BV711 anti-hCD38 (HIT2) (1:200) (BioLegend), BB700 anti-hCXCR5 (RF8B2) (1:50) (BD Biosciences), PE-CF594 anti-hCD25 (BC96) (1:200) (BD Biosciences), AlexaFluor 700 anti-hTNFa (MAb11) (1:100) (BioLegend), PE or APC/Fire750 anti-hIFNy (4S.B3) (1:60) (BioLegend), FITC anti-hGranzymeB (GB11) (1:200) (BioLegend), BV785 anti-hCD19 (SJ25C1) (1:300) (BioLegend), BV421 anti-hCD138 (MI15) (1:300) (BioLegend), AlexaFluor700 anti-hCD20 (2H7) (1:200) (BioLegend), AlexaFluor 647 anti-hCD27 (M-T271) (1:350) (BioLegend), PE/Dazzle594 anti-hIgD (IA6–2) (1:400) (BioLegend), Percp/Cy5.5 anti-hCD137 (4B4–1) (1:150) (BioLegend) and PE anti-CD69 (FN-50) (1:200) (BioLegend), APC anti-hCD40L (24–31) (1:100) (BioLegend). In brief, freshly isolated PBMCs were plated at 1–2 × 106 cells per well in a 96-well U-bottom plate. Cells were resuspended in Live/Dead Fixable Aqua (ThermoFisher) for 20 min at 4°C. Following a wash, cells were blocked with Human TruStan FcX (BioLegend) for 10 min at RT. Cocktails of desired staining antibodies were added directly to this mixture for 30 min at RT. For secondary stains, cells were first washed and supernatant aspirated; then to each cell pellet a cocktail of secondary markers was added for 30 min at 4°C. Prior to analysis, cells were washed and resuspended in 100 μl 4% PFA for 30 min at 4 °C. Following this incubation, cells were washed and prepared for analysis on an Attune NXT (ThermoFisher). Data were analysed using FlowJo software version 10.6 software (Tree Star). The specific sets of markers used to identify each subset of cells are summarized in Extended Data Figure 4.

Cell lines and virus

TMPRSS2-VeroE6 kidney epithelial cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 1% sodium pyruvate (NEAA) and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37°C and 5% CO2. The cell line was obtained from the ATCC and has been tested negative for contamination with mycoplasma. SARS-CoV-2 lineage A(USA-WA1/2020), was obtained from BEI Resources (#NR-52281) and was amplified in TMPRSS2-VeroE6. Cells were infected at a MOI 0.01 for three days to generate a working stock and after incubation the supernatant was clarified by centrifugation (450 g × 5 min), and filtered through a 0.45-micron filter. The pelleted virus was then resuspended in PBS and aliquoted for storage at −80°C. Viral titers were measured by standard plaque assay using TMPRSS2-VeroE6. Briefly, 300 µl of serial fold virus dilutions were used to infect Vero E6 cells in MEM supplemented NaHCO3, 4% FBS 0.6% Avicel RC-581. Plaques were resolved at 48h post-infection by fixing in 10% formaldehyde for 1h followed by 0.5% crystal violet in 20% ethanol staining. Plates were rinsed in water to plaques enumeration. All experiments were performed in a biosafety level 3 laboratory with approval from the Yale Environmental Health and Safety office.

SARS-CoV-2 Variant sequencing and isolation

SARS-CoV-2 samples were sequenced as part of the Yale SARS-CoV-2 Genomic Surveillance Initiative’s weekly surveillance program in Connecticut, United States33. Lineages were sequenced and isolated as described previously34. In brief, nucleic acid was extracted from de-identified remnant nasopharyngeal swabs and tested with our multiplexed RT-qPCR variant assay to select samples with a N1 cycle threshold (Ct) value of 35 or lower for sequencing35,36. Libraries were prepared with a slightly adjusted version of the Illumina COVIDSeq Test RUO version. The Yale Center for Genome Analysis sequenced pooled libraries of up to 96 samples on the Illumina NovaSeq (paired-end 150). Data was analyzed and consensus genomes were generated using iVar (version 1.3.1)37. Variants of interest and concern, lineages with mutations of concern (E484K), as well as other lineages as controls were selected for virus isolation. In total, 16 viruses were isolated belonging to 12 lineages (Extended Data Figure 3; Extended Data Table 2). In addition, ancestral lineage A virus and lineage B.1.351 virus were obtained from BEI.

Samples selected for virus isolation were diluted 1:10 in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) and then filtered through a 45 µM filter. The samples were ten-fold serially diluted from 1:50 to 1:19,531,250. The dilution was subsequently incubated with TMPRSS2-Vero E6 in a 96 well plate and adsorbed for 1 hour at 37°C. After adsorption, replacement medium was added, and cells were incubated at 37°C for up to 5 days. Supernatants from cell cultures with cytopathic effect (CPE) were collected, frozen, thawed and subjected to RT-qPCR. Fresh cultures were inoculated with the lysates as described above for viral expansion. Viral infection was subsequently confirmed through reduction of Ct values in the cell cultures with the multiplex variant qPCR assay. Expanded viruses were re-sequenced following the same method as described above and genome sequences were uploaded to GenBank (Supplementary Data Table 2), and the aligned consensus genomes are available on GitHub (https://github.com/grubaughlab/paper_2021_Nab-variants). Nextclade v1.5.0 (https://clades.nextstrain.org/) was used to generate a phylogenetic tree (Extended Data Figure 3), and to compile a list of amino acid changes in the virus isolates as compared to the Wuhan-Hu-1 reference strain (Extended Data Table 2). Key spike amino acid differences were identified based on the outbreak.info mutation tracker20.

Neutralization assay

Vaccinated HCWs sera were isolated as described before and then heat treated for 30 min at 56°C. Sixfold serially diluted plasma, from 1:3 to 1:2430 were incubated with SARS-CoV-2 variants, for 1 h at 37 °C. The mixture was subsequently incubated with TMPRSS2-VeroE6 in a 12-well plate for 1h, for adsorption. Then, cells were overlayed with MEM supplemented NaHCO3, 4% FBS 0.6% Avicel mixture. Plaques were resolved at 40 h post infection by fixing in 10% formaldehyde for 1 h followed by staining in 0.5% crystal violet. All experiments were performed in parallel with baseline controls sera, in an established viral concentration to generate 60–120 plaques/well.

Statistical analysis

All analyses of patient samples were conducted using GraphPad Prism 8.4.3, JMP 15, and R 3.4.3. Multiple group comparisons were analyzed by running parametric (ANOVA) statistical tests. Multiple comparisons were corrected using Tukey’s and Dunnett’s test as indicated in figure legends. For the comparison between stable groups, two-sided unpaired t-test was used for the comparison. The impact of spike mutations were assessed using a linear mixed model with an outcome of log transformed PRNT50 and random effects accounting for each individual subject. This was done using the “lme4” package in R 4.0.138.

Extended Data

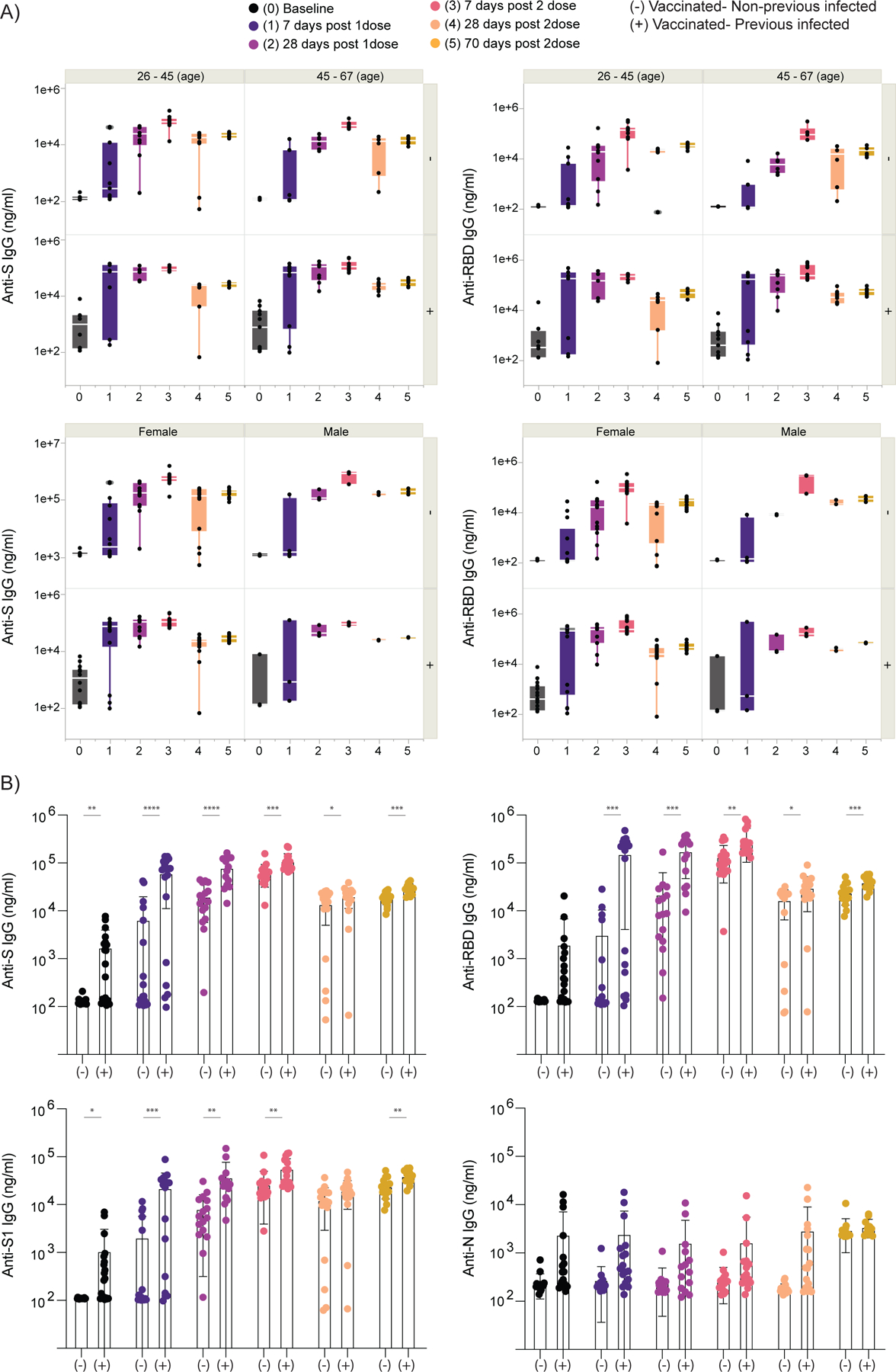

Extended Data Figure 1 |. Correlation of virus-specific antibodies with age and sex of participants.

a,b, Plasma reactivity to S protein and RBD in vaccinated participants measured over time by ELISA. HCW participants received 2 doses of the mRNA vaccines and plasma samples were collected as at the indicated time points (TP). Baseline, previously to vaccination; 1 Time point, 7 days post 1 dose; 2 Time point, 28 days post 1 dose; 3 Time point, 7 days post 2 dose; 4 Time point, 28 days post 2 dose; 5 Time point, 70 days post 2 dose. a, Anti-S (left) and Anti-RBD (right) IgG levels stratified by vaccinated participants accordingly to age and sex. Significance was accessed using unpaired two-tailed t-test. Boxes represent variables’ distribution with quartiles and outliers. Horizontal bars, mean values. b, Anti-S, Anti-S1, Anti-RBD and Anti-N IgG comparison in vaccinated participants previously infected or not to SARS-CoV-2. Longitudinal data plotted over time. Significance was accessed using unpaired two-tailed t-test. Boxes represent mean values ± standard deviations. TP, vaccination time point. Anti-S IgG (TP0, n=37; TP1, n=35; TP2, n=30; TP3, n=34; TP4, n=34; TP5, n=28). Anti-S1 IgG (TP0, n=37; TP1, n=35; TP2, n=30; TP3, n=34; TP4, n=34; TP5, n=27). Anti-RBD IgG (TP0, n=37; TP1, n=35; TP2, n=30; TP3, n=34; TP4, n=34; TP5, n=27). Anti-N IgG (TP0, n=37; TP1, n=35; TP2, n=30; TP3, n=34; TP4, n=34; TP5, n=27). S, spike. S1, spike subunit 1. RBD, receptor binding domain. N, nucleocapsid. Each dot represents a single individual. ****p < .0001 ***p < .001 **p < .01*p < .05.

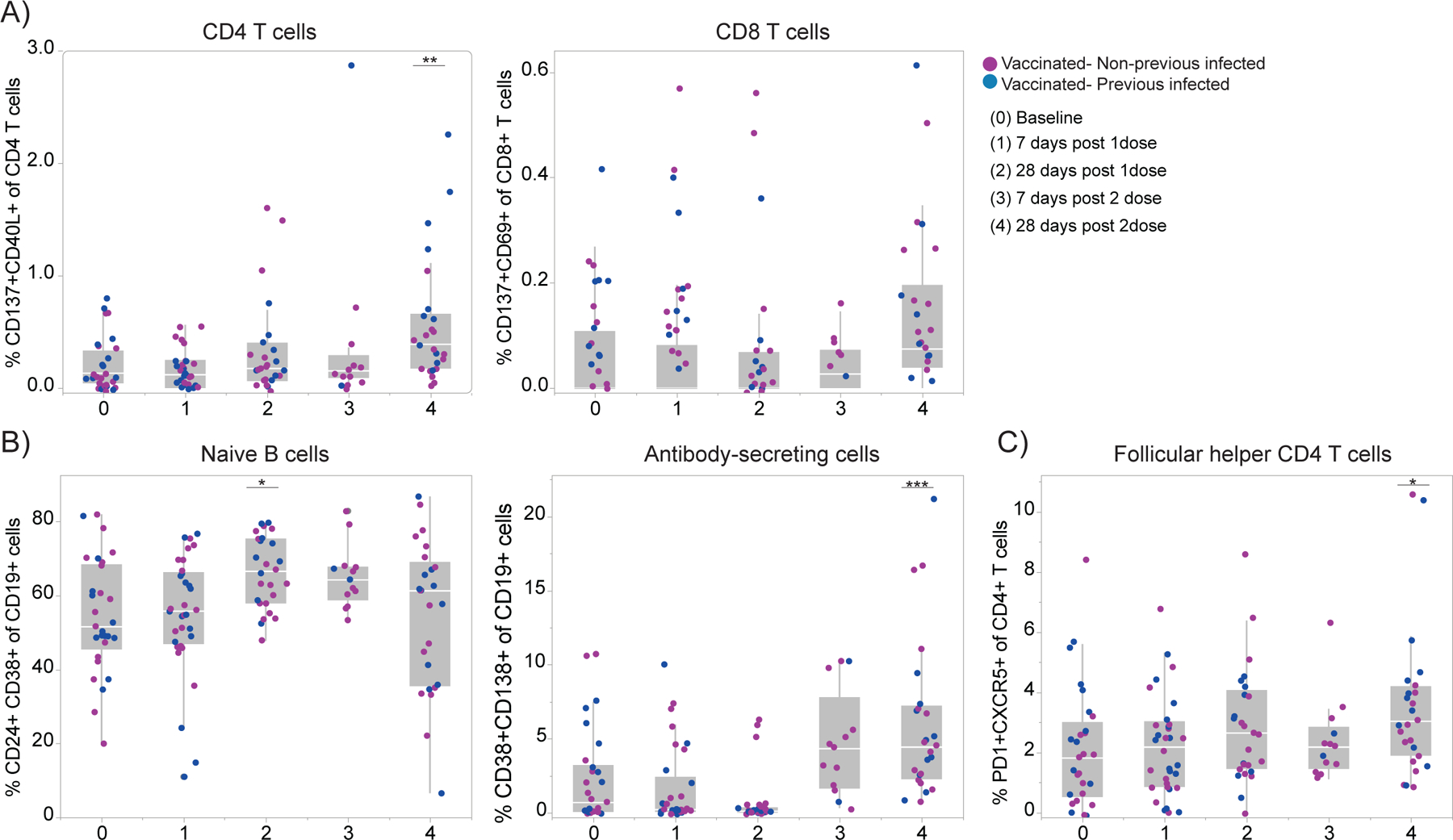

Extended Data Figure 2 |. Cellular immune profiling post SARS-CoV-2 vaccination.

a-b, Immune cell subsets of interest, plotted as a percentage of a parent population over time according to the vaccination time points. HCW participants received 2 doses of the mRNA vaccines and PBMCs samples were collected as at the indicated time points (TP). Baseline, previously to vaccination; 1 Time point, 7 days post 1 dose; 2 Time point, 28 days post 1 dose; 3 Time point, 7 days post 2 dose; 4 Time point, 28 days post 2 dose. Percentage of activated T cell subsets (a), B cell subsets (b) and Tfh cells (c) among vaccinated individuals over time. Individuals previously infected to SARS-CoV-2 or uninfected are indicated by blue or purple dots, respectively. Each dot represents a single individual. Significance was assessed by One-way ANOVA corrected for multiple comparisons using Dunnett’s method. Vaccination time points were compared with baseline. Boxes represent variables’ distribution with quartiles and outliers. Horizontal bars, mean values.TP, vaccination time point (TP0, n = 29; TP1, n=33; TP2, n =26; TP3, n = 13; TP4, n=25). ***p < .001 **p < .01*p < .05.

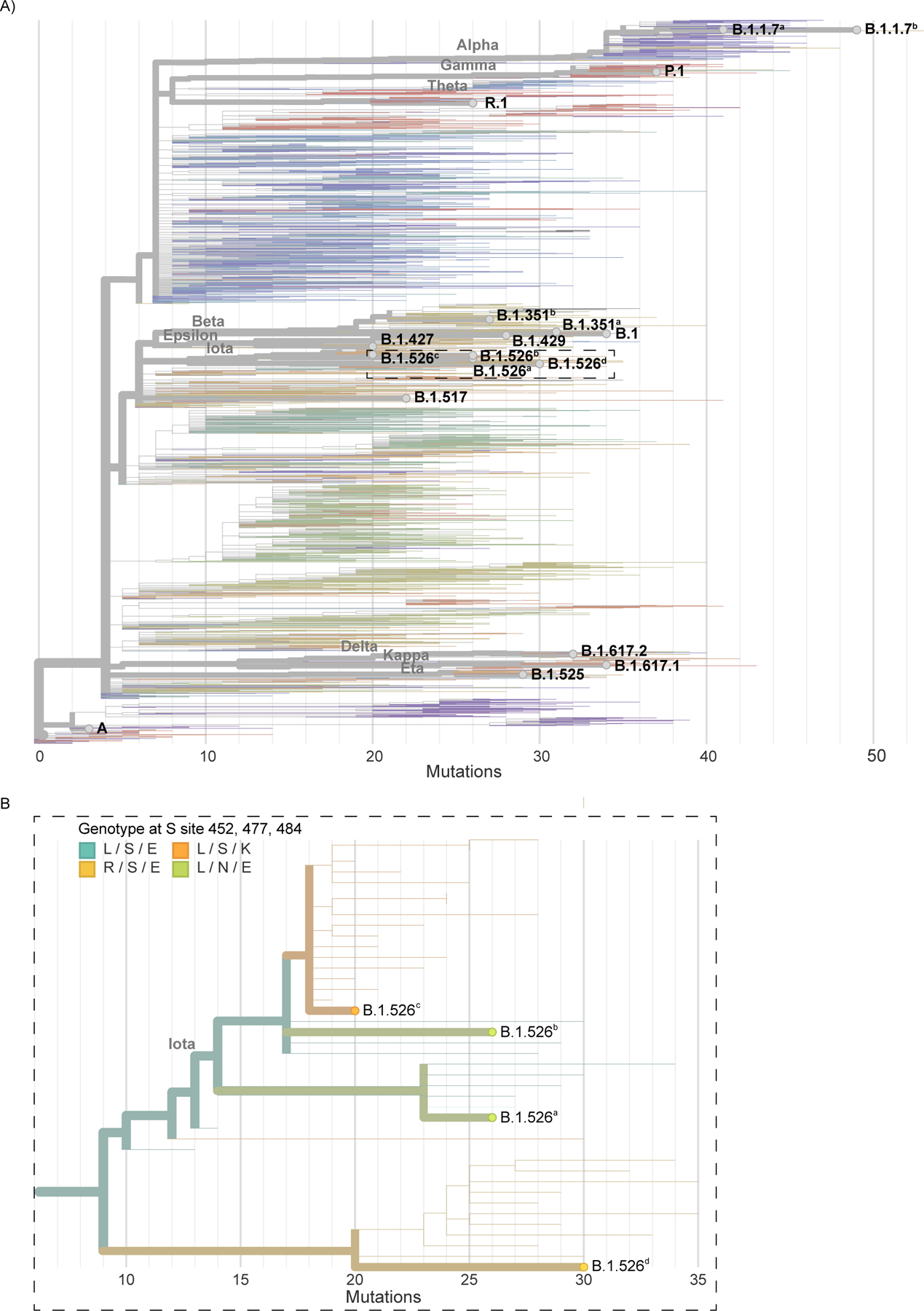

Extended Data Figure 3 |. Maximum likelihood phylogeny of SARS-CoV-2 genomes of cultured virus isolates.

a, Nextclade (https://clades.nextstrain.org/) was used to generate a phylogenetic tree to show evolutionary relations between the cultured virus isolates used in this study and other publicly available SARS-CoV-2 genomes. Branches are colored by Pango Lineage, and labelled according to the WHO naming scheme. Highlighted are the cultured virus isolates used in this study. b, Enlarged section of the phylogenetic tree highlighting spike amino acid changes in the B.1.526 (iota) lineage viruses belonging to different clades.

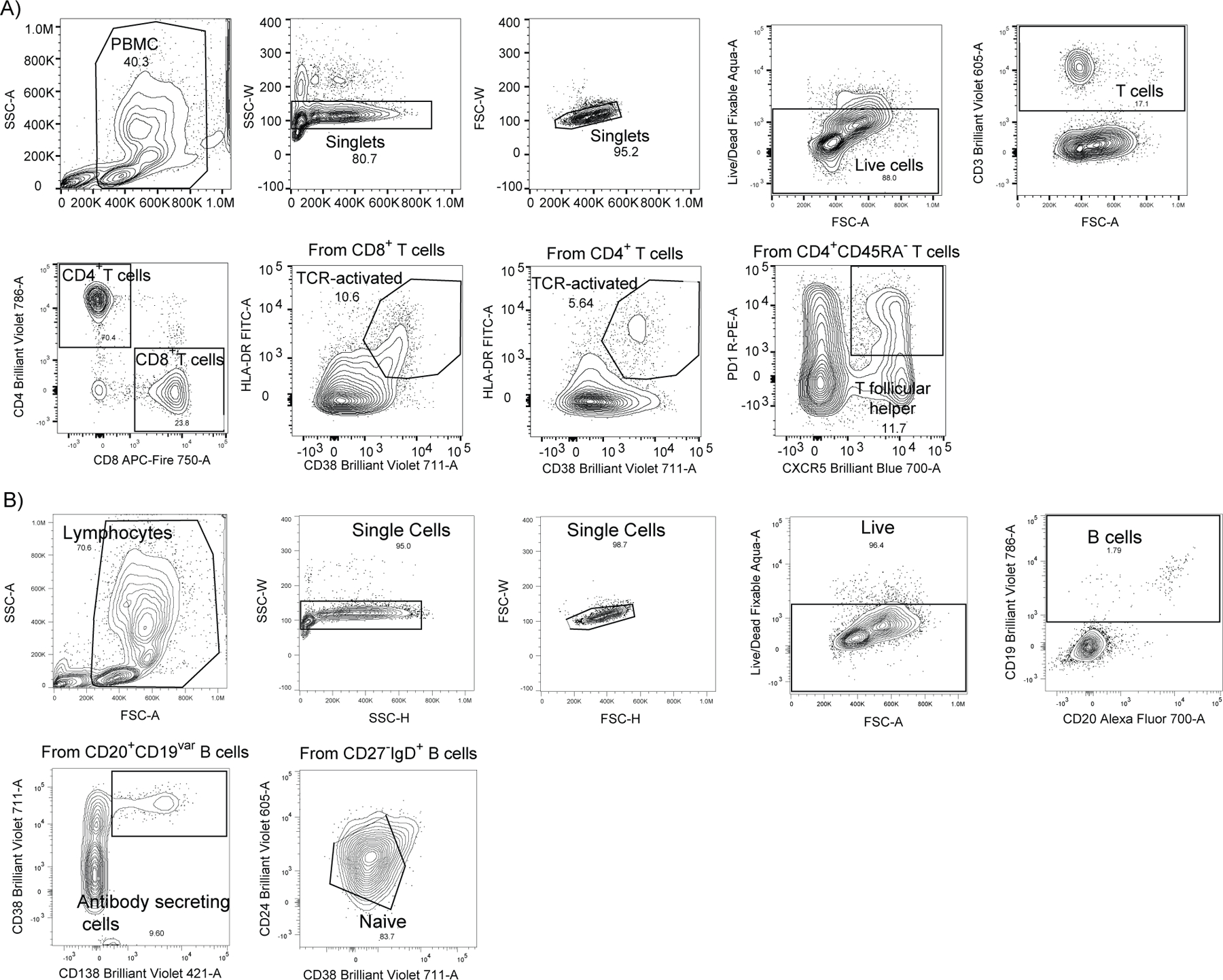

Extended Data Figure 4 |. Gating strategies.

Gating strategies are shown for the key cell populations described in Figure 2 and Extended Data Figure 2. a, Leukocyte gating strategy to identify lymphocytes. T cell surface staining gating strategy to identify CD4 and CD8 T cells, TCR-activated T cells and follicular T cells. b, B cell surface staining gating strategy to identify B cells subsets.

Extended Data Table 1 |. SARS-CoV-2 Vaccinated Cohort.

Exact counts for each demographic category are displayed in each cell with accompanying standard deviations for each measurement. Percentages of total, where applicable, are provided in parenthesis. In cases where specific demographic information was missing, the total number of patients with complete information used for calculations is provided within the cell.

| Vaccine | Sex | SeroStatus | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Moderna | Pfizer | Female | Male | Negative | Positive | |

| Total Cohort % | #DIV/0! | 80.56 | 19.44 | 80.56 | 19.44 | 50.0 | 50.0 |

| Non- Previous exposed % | 44.28 (1.833 ± 4.242) | 61.11 | 38.88 | 77.7 | 83.33 | ||

| Previous exposed % | 46.11 (1.833 ± 4.242) | 100.0 | 0.0 | 22.22 | 16.66 |

| Volunteers ID | Age range | Sex | SeroStatus | Vaccine | Age Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | B | Female | Negative | Pfizer | A | 26–35 |

| 2 | B | Female | Negative | Pfizer | B | 36–45 |

| 3 | B | Female | Negative | Moderna | C | 46–55 |

| 4 | C | Female | Negative | Moderna | D | 56–65 |

| 5 | C | Female | Negative | Pfizer | E | 66–75 |

| 6 | B | Female | Negative | Pfizer | ||

| 7 | E | Female | Negative | Moderna | ||

| 8 | B | Female | Negative | Moderna | ||

| 9 | C | Male | Negative | Moderna | ||

| 10 | A | Female | Negative | Pfizer | ||

| 11 | B | Female | Negative | Moderna | ||

| 12 | B | Male | Negative | Moderna | ||

| 13 | D | Male | Negative | Moderna | ||

| 14 | A | Female | Negative | Moderna | ||

| 15 | D | Female | Negative | Pfizer | ||

| 16 | B | Female | Negative | Moderna | ||

| 17 | A | Female | Negative | Moderna | ||

| 18 | C | Male | Negative | Pfizer | ||

| 20 | D | Female | Positive | Moderna | ||

| 21 | A | Female | Positive | Moderna | ||

| 22 | D | Female | Positive | Moderna | ||

| 24 | E | Female | Positive | Moderna | ||

| 25 | C | Female | Positive | Moderna | ||

| 26 | B | Female | Positive | Moderna | ||

| 27 | C | Male | Positive | Moderna | ||

| 28 | D | Female | Positive | Moderna | ||

| 30 | A | Male | Positive | Moderna | ||

| 31 | A | Female | Positive | Moderna | ||

| 32 | C | Female | Positive | Moderna | ||

| 33 | A | Female | Positive | Moderna | ||

| 34 | A | Female | Positive | Moderna | ||

| 35 | C | Female | Positive | Moderna | ||

| 36 | D | Female | pOsitive | Moderna | ||

| 37 | D | Female | Positive | Moderna | ||

| 38 | D | Female | Positive | Moderna | ||

| 39 | A | Male | Positive | Moderna | ||

Extended Data Table 2 |. Amino acid changes identified in cultured SARS-CoV-2 isolates.

Cultured virus isolates were resequenced and the consensus genomes were compared to the reference genome (Accession MN908947) using Nextclade (https://clades.nextstrain.org/). Letters indicate amino acids, numbers indicate amino acid positions, asterisks indicate stop codon mutations, and dashes indicate deletions. Abbreviations: E, envelope; M, membrane; N, nucleocapsid; ORF, open reading frame; S, spike.

| Lineage GenBank Accession | A MZ468053 |

B.1.526a MZ467323 |

B.1.526b MZ467333 |

B.1.1.7a MZ202178 |

B.1.517 MZ468008 |

B.1.526c MZ201303 |

B.1.617.2 MZ468047 |

R.1 MZ467697 |

B.1.427 MZ467318 |

B.1.526d MZ467322 |

B.1.429 MZ467319 |

B.1.525 MZ467313 |

B.1.617.1 MZ468046 |

P.1 MZ202306 |

B.1 MZ467989 |

B.1.1.7b MZ467988 |

B.1.351a MZ468007 |

B.1.351b MZ202314 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E | V62F | L21F | P71L | P71L | ||||||||||||||

| M | I82T | F28L T175M |

I82T | I82S | ||||||||||||||

| N | P13L S202R A414V |

P199L M234I |

D3L R203K G204R S235F |

S206F | P199L M234I |

D63G R203M D377Y |

S187L R203K G204R Q418H |

T205I T362I |

T205I M234I |

T205I M234I |

M1- S2M D3Y A12G T205I |

R203M D377Y |

P80R R203K G204R |

D3Y T205I |

D3L R203K G204R S235F |

T205I | T205I | |

| ORF1a | T265I T1840I G1946S L3201P S3675- G3676- F3677- |

T265I A1352V L3201P P3504S S3675- G3676- F3677- |

T1001I P1213L A1708D I2230T M2259I S3675- G3676- F3677- |

T265I A541S G989V H1580Y |

T265I T2977I L3201P S3675- G3676- F3677- |

P309L A405V P1640L A3209V V3718A |

T265I S3158T |

T265I T2087I K3162E L3201P A3209V P3359S S3675- G3676- F3677- V3847I L4126F |

T265I I4205V |

T2007I L2609I S3675- G3676- F3677- |

T1567I T3646A |

S1188L K1795Q G2941S S3675- G3676- F3677- |

G150S T265I V649F T708I A1049V T1854I K2497N R3542C M4375T |

E913D T1001I A1306T A1708D P2046L I2230T M2259I S3675- G3676- F3677- L3736F L3829F |

T265I T333M Y1598C K1655N E1843D T2174I K3353R S3675- G3676- F3677- T4065I |

T265I K1655N K3353R S3675- G3676- F3677- |

||

| ORF1b | P314L Q1011H | P314L Q1011H | P218L P314L A1432V |

P314L D1506N P2633S |

P314L Q1011H R1078C |

P314L G662S P1000L P1570L |

P314L G814C G1362R P1936H |

P314L P976L D1183Y |

P314L | P314L D1183Y G2436C |

P314F | P314L G1129C A1291S M1352I K2310R S2312A |

P314L A1219S E1264D |

T132I P314L |

P218L P314L T1511I |

P314L T1050I Y2608H |

P314L | |

| ORF3a | P42L Q57H |

P42L Q57H |

Q57H D210E |

P42L Q57H |

S26L | Q57H | P42L Q57H |

Q57H | S92L | S26L | Q57H S253P |

Q57H P104S S171L |

Q57H S171L | Q57H W131L S171L |

||||

| ORF6 | M1- F2M |

|||||||||||||||||

| ORF7a | L116F | V82A L116F T120I |

P34S | A105S | N43Y V82A | V93F | ||||||||||||

| ORF8 | L84S | T11I | T11I | Q27* R52I K68* Y73C |

E59* | T11I | D119- F120- |

T11I P36S A51S |

V100L | E92K | E106D | Q27* R52I K68* Y73C |

I121L | R115L | ||||

| ORF9b | P10S | T83I | T60A | H9D | Q77E | |||||||||||||

| S | L5F T95I D253G S477N D614G Q957R |

L5F T95I D253G S477N D614G A701V |

H69- V70- Y144- N501Y A570D D614G P681H T716I S982A D1118H |

N501T Q613H D614G G639V |

L5F T95I D253G E484K D614G A701V |

T19R E156 F157- R158G L452R T478K D614G P681R D950N L1141W |

W152L E484K K558N D614G G769V |

S13I W152C L452R D614G |

D80G Y144- F157S L452R D614G T791I T859N D950H |

S13I W152C L452R D614G |

H69- V70- Y144- Q52R A67V E484K D614G Q677H F888L |

T95I G142D E154K L452R E484Q D614G P681R Q1071H |

L18F T20N P26S D138Y R190S K417T E484K N501Y D614G H655Y T1027I V1176F |

E484K N501T D614G |

H69- V70- Y144- E484K N501Y A570D D614G P681H T716I S982A D1118H |

D80A D215G L241- L242- A243- K417N E484K N501Y D614G A701V |

L18F D80A D215G L241- L242- A243- K417N E484K N501Y D614G Q677H R682W A701V |

Abbreviations: E = envelope, M = membrane, N = nucleocapsid, ORF = open reading frame, S = spike.

Supplementary Material

Clinical information, demographics and exact counts for immunological data.

Acknowledgements

We thank M. Linehan for technical and logistical assistance, D. Mucida for discussions, and M. Suchard and W. Hanage for statistics advice. This work was supported by the Women’s Health Research at Yale Pilot Project Program (A.I.), Fast Grant from Emergent Ventures at the Mercatus Center (A.I. and N.D.G.), Mathers Foundation, and the Ludwig Family Foundation, the Department of Internal Medicine at the Yale School of Medicine, Yale School of Public Health and the Beatrice Kleinberg Neuwirth Fund. A.I. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. C.L. is a Pew Latin American Fellow. C.B.F.V. is supported by NWO Rubicon 019.181EN.004.

Yale SARS-CoV-2 Genomic Surveillance Initiative

Claire Pearson11, Anthony Muyombwe11, Randy Downing11, Jafar Razeq11, Mary Petrone2, Isabel Ott2, Anne Watkins2, Chaney Kalinich2, Tara Alpert2, Anderson Brito2, Rebecca Earnest2, Steven Murphy12, Caleb Neal12, Eva Laszlo12, Ahmad Altajar12, Irina Tikhonova13, Christopher Castaldi13, Shrikant Mane13, Kaya Bilguvar13, Nicholas Kerantzas14, David Ferguson15, Wade Schulz15,16, Marie Landry17, David Peaper17.

2Department of Epidemiology of Microbial Diseases, Yale School of Public Health, New Haven, CT, USA.

11Connecticut State Department of Public Health, Rocky Hill, CT 06067, USA

12Murphy Medical Associates, Greenwich, CT 06830, USA

13Yale Center for Genome Analysis, Yale University, New Haven, CT, 06510, USA

14Department of Laboratory Medicine, Yale New Haven Hospital, CT 06510, USA

15Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation, Yale New Haven Hospital, CT 06510, USA

16Department of Laboratory Medicine, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT 06510, USA

17Departments of Laboratory Medicine and Medicine, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT 06510, USA

Footnotes

Competing interests: AI served as a consultant for Spring Discovery, Boehringer Ingelheim and Adaptive Biotechnologies. IY reported being a member of the mRNA-1273 Study Group and has received funding to her institution to conduct clinical research from BioFire, MedImmune, Regeneron, PaxVax, Pfizer, GSK, Merck, Novavax, Sanofi-Pasteur, and Micron. NDG is a consultant for Tempus Labs to develop infectious disease diagnostic assays.

All other authors declare no competing interests.

Data availability

The data generated during the current study is available as indicated. All the background information for HCWs participants and data generated in this study are included in Supplementary Data file. All the genome information for SARS-CoV-2 variants used in this study are available in Extended Data Table 2, and the aligned consensus genomes are available on GitHub (https://github.com/grubaughlab/paper_2021_Nab-variants). Additional correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to the corresponding author (A.I).

Main references

- 1.Cele S et al. Escape of SARS-CoV-2 501Y.V2 from neutralization by convalescent plasma. Nature 593, 142–146 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garcia-Beltran WF et al. Multiple SARS-CoV-2 variants escape neutralization by vaccine-induced humoral immunity. Cell 184, 2372–2383.e9 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Z et al. mRNA vaccine-elicited antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 and circulating variants. Nature 592, 616–622 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen RE et al. Resistance of SARS-CoV-2 variants to neutralization by monoclonal and serum-derived polyclonal antibodies. Nat. Med 27, 717–726 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang P et al. Antibody resistance of SARS-CoV-2 variants B.1.351 and B.1.1.7. Nature 593, 130–135 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stamatatos L et al. mRNA vaccination boosts cross-variant neutralizing antibodies elicited by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Science (2021) doi: 10.1126/science.abg9175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson LA et al. An mRNA Vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 - Preliminary Report. N. Engl. J. Med 383, 1920–1931 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walsh EE et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of Two RNA-Based Covid-19 Vaccine Candidates. N. Engl. J. Med 383, 2439–2450 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies NG et al. Estimated transmissibility and impact of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.1.7 in England. Science 372, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sabino EC et al. Resurgence of COVID-19 in Manaus, Brazil, despite high seroprevalence. Lancet 397, 452–455 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jalkanen P et al. COVID-19 mRNA vaccine induced antibody responses against three SARS-CoV-2 variants. Nat. Commun 12, 3991 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sahin U et al. COVID-19 vaccine BNT162b1 elicits human antibody and TH1 T cell responses. Nature 586, 594–599 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braun J et al. SARS-CoV-2-reactive T cells in healthy donors and patients with COVID-19. Nature 587, 270–274 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dan JM et al. Immunological memory to SARS-CoV-2 assessed for up to 8 months after infection. Science 371, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao J et al. Airway Memory CD4(+) T Cells Mediate Protective Immunity against Emerging Respiratory Coronaviruses. Immunity 44, 1379–1391 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alter G et al. Immunogenicity of Ad26.COV2.S vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 variants in humans. Nature (2021) doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03681-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tarke A et al. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 variants on the total CD4+ and CD8+ T cell reactivity in infected or vaccinated individuals. Cell Reports Medicine 100355 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Connecticut SARS-CoV-2 Variant Surveillance https://covidtrackerct.com/ (2020).

- 19.CDC. SARS-CoV-2 Variant Classifications and Definitions https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/variants/variant-info.html (2021).

- 20.SARS-CoV-2 (hCoV-19) Mutation Reports. outbreak.info https://outbreak.info/situation-reports (2021).

- 21.Zou J et al. The effect of SARS-CoV-2 D614G mutation on BNT162b2 vaccine-elicited neutralization. NPJ Vaccines 6, 44 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robbiani DF et al. Convergent antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in convalescent individuals. Nature 584, 437–442 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barnes CO et al. SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody structures inform therapeutic strategies. Nature 588, 682–687 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCallum M et al. N-terminal domain antigenic mapping reveals a site of vulnerability for SARS-CoV-2. bioRxiv (2021) doi: 10.1101/2021.01.14.426475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xie X et al. Neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 spike 69/70 deletion, E484K and N501Y variants by BNT162b2 vaccine-elicited sera. Nat. Med 27, 620–621 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bernal JL et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against the B.1.617.2 variant. bioRxiv (2021) doi: 10.1101/2021.05.22.21257658. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bolze A et al. Rapid displacement of SARS-CoV-2 variant B.1.1.7 by B.1.617.2 and P.1 in the United States. bioRxiv (2021) doi: 10.1101/2021.06.20.21259195. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lustig Y et al. Neutralising capacity against Delta (B.1.617.2) and other variants of concern following Comirnaty (BNT162b2, BioNTech/Pfizer) vaccination in health care workers, Israel. Euro Surveill 26, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Challen R et al. Early epidemiological signatures of novel SARS-CoV-2 variants: establishment of B.1.617.2 in England. bioRxiv (2021) doi: 10.1101/2021.06.05.21258365. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lucas C et al. Delayed production of neutralizing antibodies correlates with fatal COVID-19. Nat. Med (2021) doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01355-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.U.S. Food & Drug Administration. EUA Authorized Serology Test Performance https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19-emergency-use-authorizations-medical-devices/eua-authorized-serology-test-performance (2021).

Methods references

- 32.Amanat F et al. A serological assay to detect SARS-CoV-2 seroconversion in humans. Nat. Med 26, 1033–1036 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kalinich CC et al. Real-time public health communication of local SARS-CoV-2 genomic epidemiology. PLoS Biol 18, e3000869 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mao T et al. A stem-loop RNA RIG-I agonist confers prophylactic and therapeutic protection against acute and chronic SARS-CoV-2 infection in mice. bioRxiv 2021.06.16.448754 (2021) doi: 10.1101/2021.06.16.448754. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vogels CBF et al. Multiplex qPCR discriminates variants of concern to enhance global surveillance of SARS-CoV-2. PLoS Biol 19, e3001236 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vogels CBF, Fauver JR & Grubaugh ND Multiplexed RT-qPCR to screen for SARS-COV-2 B.1.1.7, B.1.351, and P.1 variants of concern V.3 10.17504/protocols.io.br9vm966 (2021) doi: 10.17504/protocols.io.br9vm966. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grubaugh ND et al. An amplicon-based sequencing framework for accurately measuring intrahost virus diversity using PrimalSeq and iVar. Genome Biol 20, 8 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B & Walker S Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, Articles 67, 1–48 (2015). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Clinical information, demographics and exact counts for immunological data.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated during the current study is available as indicated. All the background information for HCWs participants and data generated in this study are included in Supplementary Data file. All the genome information for SARS-CoV-2 variants used in this study are available in Extended Data Table 2, and the aligned consensus genomes are available on GitHub (https://github.com/grubaughlab/paper_2021_Nab-variants). Additional correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to the corresponding author (A.I).