Abstract

Here we report on the overexpression and in vitro characterization of a recombinant form of ExoM, a putative β1-4 glucosyltransferase involved in the assembly of the octasaccharide repeating subunit of succinoglycan from Sinorhizobium meliloti. The open reading frame exoM was isolated by PCR and subcloned into the expression vector pET29b, allowing inducible expression under the control of the T7 promoter. Escherichia coli BL21(DE3)/pLysS containing exoM expressed a novel 38-kDa protein corresponding to ExoM in N-terminal fusion with the S-tag peptide. Cell fractionation studies showed that the protein is expressed in E. coli as a membrane-bound protein in agreement with the presence of a predicted C-terminal transmembrane region. E. coli membrane preparations containing ExoM were shown to be capable of transferring glucose from UDP-glucose to glycolipid extracts from an S. meliloti mutant strain which accumulates the ExoM substrate (Glcβ1-4Glcβ1-3Gal-pyrophosphate-polyprenol). Thin-layer chromatography of the glycosidic portion of the ExoM product showed that the oligosaccharide formed comigrates with an authentic standard. The oligosaccharide produced by the recombinant ExoM, but not the starting substrate, was sensitive to cleavage with a specific cellobiohydrolase, consistent with the formation of a β1-4 glucosidic linkage. No evidence for the transfer of multiple glucose residues to the glycolipid substrate was observed. It was also found that ExoM does not transfer glucose to an acceptor substrate that has been hydrolyzed from the polyprenol anchor. Furthermore, neither glucose, cellobiose, nor the trisaccharide Glcβ1-4Glcβ1-3Glc inhibited the transferase activity, suggesting that some feature of the lipid anchor is necessary for activity.

Rhizobial succinoglycan or exopolysaccharide I has been shown to play an important role in the symbiotic relationship between the nitrogen-fixing bacterium Sinorhizobium meliloti (formerly known as Rhizobium meliloti) and its plant host, alfalfa (Medicago sativa) (17, 18, 30). Recent elegant studies employing succinoglycan-deficient strains of S. meliloti expressing green fluorescent protein have shown that succinoglycan is required for the formation of extended infection threads in the root hairs that would otherwise allow the bacteria to populate the root nodule (8). In addition to its role in symbiosis, the physicochemical properties of succinoglycan have led to its use as a gelling agent in certain industrial applications (13).

Like other bacterial exopolysaccharides, such as xanthan gum from Xanthomonas campestris and acetan from Acetobacter xylinum, succinoglycan is synthesized by the polymerization of an oligosaccharide subunit that has been assembled upon a polyprenyl pyrophosphate anchor (14, 27). This mechanism is similar to that observed in the biosynthesis of the O-antigen portion of many lipopolysaccharides and of some capsular polysaccharides of gram-negative bacteria (33). The assembly of the oligosaccharide unit of repetition is a key feature in the biosynthesis of cell surface-associated polysaccharides.

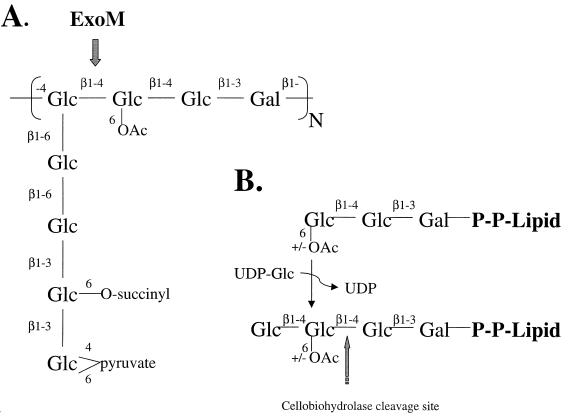

Succinoglycan secreted by S. meliloti is a polymer of an octasaccharide subunit, which is in turn comprised of one residue of galactose and seven residues of glucose, joined in either β1-4, β1-3, or β1-6 glycosidic linkages (Fig. 1A) (22). Each octasaccharide is specifically replaced by one group each of acetate, succinate, and pyruvate. The subunits are joined via a β1-4 linkage from the first to the fourth residue, resulting in a branched, acidic polysaccharide. Succinoglycan is found in two forms, a high-molecular-weight form of fairly uniform molecular-mass distribution ranging from 106 to 107 Da and a low-molecular-weight form consisting of monomers, dimers, and trimers of the octasaccharide subunit (11, 12). Several studies suggest that the low-molecular-weight form is required for the invasion of the root nodules (2, 29).

FIG. 1.

(A) Structure of the octasaccharide repeat unit of succinoglycan with the point of ExoM activity indicated. (B) Reaction catalyzed by ExoM, with the site of cellobiohydrolase II cleavage indicated.

At least 26 genes are known to be involved in the biosynthetic pathway of succinoglycan in S. meliloti 1021 (3–5, 9, 10, 19, 21), the majority of which are located in a single cluster (exo cluster) on one of two symbiotic megaplasmids (pSym II). Studies of the biosynthetic intermediates produced by S. meliloti mutant strains and sequence similarities to other gene products known to be involved in bacterial polysaccharide biosynthesis have allowed the assignment of putative activities to 11 gene products in the cluster, whose activity is required for the production of the fully substituted lipid-linked octasaccharide (24). The presence of both exoF and exoY is necessary for the initial transfer of galactose-1-phosphate from UDP-galactose (UDP-Gal) to polyprenyl-phosphate (24). Six putative glucosyltransferases encoded by exoA, exoL, exoM, exoO, exoU, and exoW are then thought to be responsible for the sequential transfer of the remaining seven residues from UDP-glucose (UDP-Glc) to the growing lipid-linked oligosaccharide (9, 24). As no mutants producing lipid-linked heptasaccharides have been isolated and no other genes resembling those that encode the glycosyltransferases have been identified in the exo cluster, it has been proposed that ExoW may be responsible for the addition of the two terminal β1-3-linked glucose residues of the octasaccharide (18). Three putative glycosyl-modifying enzymes (ExoZ, an acetyltransferase; ExoH, a succinyl transerase; and ExoV, a pyruvyl transferase) act during the assembly of the oligosaccharide, before the completed octasaccharide is polymerized (10, 24). TnphoA fusion studies of the relevant gene products and the obligatory presence of nucleotide sugars support the idea that the oligosaccharide subunit is biosynthesized on the cytoplasmic face of the inner cell wall membrane (9, 23).

The Exo glucosyltransferases are functionally similar to one another in that each presumably employs a UDP-Glc sugar donor to catalyze the formation of a β-glycosidic linkage to a glucose residue (except ExoA, which transfers to galactose), albeit with different regiospecificities, i.e., β1-3 for ExoA and ExoW, β1-4 for ExoM and ExoL, and β1-6 for ExoO and ExoU. However, these enzymes (except ExoL) have significant similarity only within an N-terminal 100-amino-acid region (domain A) which includes three highly conserved aspartic acid residues (25). Two of these conserved Asp residues (DXD motif) are also found in a number of other prokaryotic and eukaryotic glycosyltransferases and in polysaccharide synthases which employ nucleotide sugars to transfer hexoses such as galactose, mannose, N-acetylglucosamine, N-acetylgalactosamine, or N-acetylmannosamine to a variety of different carbohydrate, protein, or steroid acceptors (6, 15, 34). Recent studies of the glucosyltransferase domain of a large clostridial cytotoxin suggest that both of the aspartic acid residues of the conserved DXD motif may be involved in nucleotide sugar and/or divalent cation binding (7). Therefore, despite their functional similarities, it is not evident which feature of each of the Exo glucosyltransferases determines their nucleotide sugar donor usage, their acceptor specificity, and the regio- and stereospecificity of each glycosidic bond formed. The expression of recombinant forms of the Exo glucosyltransferases and the verification of their putative activities in vitro are the first steps towards functional and structural studies which may resolve such questions. Here we report on the overexpression in Escherichia coli and subsequent study in vitro of a recombinant form of ExoM. Our studies demonstrate that ExoM is a nonprocessive glucosyltransferase responsible for the addition of the fourth residue of the polyprenol-anchored octasaccharide subunit, most likely in a β1-4 linkage (Fig. 1B).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials, culture conditions, and bacterial strains.

See Table 1 for descriptions of plasmids and genotypes of all strains employed. All cloning work was performed in E. coli XL1-Blue cells. Recombinant proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3)/pLysS. E. coli was grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at 37°C. S. meliloti was grown in LB medium with 2.5 mM MgSO4 and 2.5 mM CaCl2 at 30°C. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: kanamycin, 30 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 34 μg/ml; neomycin, 200 μg/ml; gentamicin, 20 μg/ml; spectinomycin, 50 μg/ml; and trimethoprim, 500 μg/ml. Oligonucleotide primers for PCR were purchased from Oligoexpress (Paris, France). Blunting and ligations were performed with the kits from Amersham France (Les Ulis, France). Pfu polymerase was from Stratagene (La Jolla, Calif.), and all other enzymes used for molecular biology were purchased from New England Biolabs (Beverly, Mass.). 14C-labeled nucleotide sugars were obtained from Amersham. The pET29b expression vector and S-tag Western blotting kit were from Novagen (Madison, Wis.). Recombinant cellobiohydrolase II of Humicola insolens was a gift from M. Schülein. Glcβ1-4Glcβ1-3Gal was a gift from Hugues Driguez. Protein concentrations were determined by the Bio-Rad DC assay. Analytical-grade solvents were used, unless noted otherwise.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| XL1-Blue | recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 relA1 lac [F′ proAB lacIqZM15::Tn10(Tetr)]c | Stratagene |

| BL21(DE3)/pLysS | F−ompT hsdSB (rB− mB−) gal dcm (DE3) pLysS(Cmr) | Novagen |

| S. meliloti | ||

| Rm8278 | Rm1021 exoM::Tn5 exoB::Tn5-Tp exoR::Tn-233 | 24 |

| Rm10003 | Rm1021 exoO::Tn5 exoB::Tn5-Tp exoR::Tn-233 | 24 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pEX154 | Tcr pLAFR1 cosmid containing EcoRI fragment of S. meliloti exo gene cluster | 19 |

| pBluescript KS(+) | General cloning vector, Ampr | Stratagene |

| pLGC1 | pBluescript KS(+) containing exoM PCR product | This work |

| pET29b | Prokaryotic expression vector, Kanr | Novagen |

| pLGC2 | pET29b containing SacI-NotI exoM fragment from pLGC1 | This work |

Isolation and subcloning of exoM.

The 943-bp open reading frame (ORF) of exoM was amplified by PCR from the cosmid pEX154 (19). Primers used were ACTGCAGGTTCATGCCGAGGTCACC and AGAGCTCCCTAATGCCGAACGAAAC. The underlined sequences create PstI and SacI restriction sites at each end of the gene. The desired product was obtained by using the Pfu polymerase in 35 cycles, with each cycle comprising 45 s of denaturation at 94°C, 1 min of annealing at 58°C, and 2 min of elongation at 72°C. The PCR product was purified from an agarose gel, subcloned in the EcoRV site of pBluescript KS(+) to give pLGC1, and subsequently verified by DNA sequencing (Genome Express SA, Grenoble, France). Cleavage of pLGC1 with SacI-NotI generated two fragments corresponding to pBluescript and a 984-bp fragment containing the exoM ORF. The 984-bp fragment was then cloned into the SacI-NotI sites of the expression vector pET29b to give pLGC2.

Expression of exoM.

E. coli BL21(DE3)/pLysS cells were transformed with pLGC2 or with pET29b as a control. Cultures (50 to 200 ml) were inoculated with 0.5 to 2.0 ml of preculture prepared overnight. Optimal protein expression was obtained by induction with 0.4 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) when cultures had reached an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.5. Expression of recombinant ExoM was monitored by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), followed by staining with Coomassie brilliant blue R250. The presence of the N-terminal S-tag epitope fusion was confirmed by transfer of an SDS–12% PAGE gel to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane and subsequent treatment with the Novagen S-tag Western blotting kit with alkaline phosphatase S-protein conjugate per the manufacturer’s instructions. For N-terminal sequencing, 20 μg of protein from a membrane fraction preparation was treated with 0.1 U of thrombin for 2 h at 20°C in the presence of 0.1% SDS to release the S-tag fragment. The protein sample was separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred electrophoretically onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, according to the protocol defined for ProBlott membranes (Applied Biosystems). Amino acid sequence determination of the digestion product was performed with a gas-phase sequencer (model 477A; Applied Biosystems). Phenylthiohydantoin amino acid derivatives were identified and quantitated on-line with a model 120A high-pressure liquid chromatography system (Applied Biosystems), as recommended by the manufacturer (20).

For protein production, cells were harvested 2 h after induction, washed once with 70 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), resuspended in 70 mM Tris-HCl–10 mM EDTA (pH 8.2) at 40 OD equivalents/ml, and passed through the French press (18,000 lb/in2) three times. Unbroken cells and inclusion bodies were recovered by a 15-min centrifugation (5,000 × g) at 4°C. Membrane fractions were recovered from the 5,000 × g supernatant by a 1-h centrifugation (100,000 × g) at 4°C (Beckman, model LE-70, Ti70 centrifuge). The membrane pellet was resuspended in a volume of buffer (70 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM EDTA, pH 8.2) equivalent to that of the starting sample, divided into 100-μl aliquots, and stored at −20°C until they were used. The stock membrane fractions were typically 7 to 9 mg of total protein per ml.

Preparation of rhizobial glycolipid acceptors.

EDTA-permeabilized samples of S. meliloti exoMBR or exoOBR triple mutants were obtained essentially by the freeze-thaw method described by Tolmasky et al. (28). Briefly, 200-ml cultures were harvested at an OD600 of 0.6 to 1.0. Cells were collected, washed once with 70 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.2), resuspended in 70 mM Tris-HCl–10 mM EDTA (pH 8.2), and subsequently subjected to three cycles of freeze-thawing in liquid nitrogen. The cells were finally stored in 70-μl aliquots at −70°C. To synthesize the unlabeled glycolipid acceptor, the permeabilized cells were incubated at 10°C for 30 min in the presence of 0.5 mM UDP-Glc, 0.5 mM UDP-Gal, and 12 mM MgCl2 in a total volume of 100 μl. For the preparation of 14C-labeled acceptor, the appropriate nucleotide sugar donor was replaced with 0.25 μCi of UDP-[U-14C]glucose or UDP-[U-14C]galactose (specific activities of 231 and 261 mCi/mmol, respectively). The reaction was stopped by the addition of 0.5 ml of ice-cold 70 mM Tris-HCl–10 mM EDTA (pH 8.2), and washed once with 0.3 ml of 70 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.2). The glycolipid acceptors were recovered by two 150-μl extractions with CHCl3:MeOH:H2O at a ratio of 1:2:0.3. The extract was stored at −20°C until it was used.

Glucosyltransferase assay.

The CHCl3:MeOH:H2O (1:2:0.3) extract containing the glycolipid acceptor (either cold or 14C labeled) was dried to a final volume of approximately 10 μl under a stream of compressed air immediately prior to use. To the lipid emulsion was added 0.1% Triton X-100, 12 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM UDP-Glc, and 50 μl (∼350 μg) of resuspended E. coli membranes to a final reaction mixture volume of 100 μl. For inhibition studies, glucose, cellobiose, or the trisaccharide Glcβ1-4Glcβ1-3Glc was added to the reaction mixture at a final concentration of 1 mM. The reaction mixture was incubated for 30 min at 37°C, and the reaction was stopped by the addition of 100 μl of H2O and 200 μl of CHCl3:MeOH (1:2). The reaction mixture was mixed vigorously in a Vortex mixer and centrifuged for 3 min, and the aqueous layer was discarded. The remaining organic and particulate phases were washed twice with 1 volume of H2O and 0.5 volumes of CHCl3:MeOH (1:2) to remove any traces of unreacted nucleotide 14C-sugar. The organic phase was removed and saved. The particulate phase was extracted twice with 150 μl of CHCl3:MeOH:H2O (1:2:0.3), and extracts were pooled with the organic phase. A 1/10 volume of the final organic extract pool was monitored by liquid scintillation counting. The remaining organic extract pool was dried on a SpeedVac. The oligosaccharide was cleaved from the lipid anchor by mild acid hydrolysis with 200 μl of 0.01 N aqueous trifluoroacetic acid for 10 min at 100°C. The hydrolysate was neutralized with 2 μl of 1 M NH4OH and treated overnight with 5 U of bovine alkaline phosphatase in the presence of 10 mM glycine–NaOH–10 mM MgCl2 (pH 9) to remove any remaining sugar-linked phosphates. The reaction mixture was extracted with 0.5 ml of CHCl3:MeOH (2:1) to remove the released lipid moiety. The aqueous phase was desalted over a mixed bed resin. The resin was rinsed twice with 200 μl of H2O, and the washes were pooled with the sample. A 1/10 volume was removed for counting. The final sample was dried on a SpeedVac and resuspended in 10 to 20 μl of H2O before thin-layer chromatography (TLC).

TLC analysis of products.

Typically 10,000 cpm of each sample to be analyzed, in 5 to 10 μl of H2O, was applied to a TLC plate (silica gel 60, 0.25-mm-thick layer of silica gel; Sigma). One microliter of oligomaltose (50 mg/ml) was applied to each sample lane as a carrier sugar. Glucose, maltose, and oligomaltose (dimer to pentamer) were run in adjacent lanes as standards. Plates were developed twice in 50:20:20 1-propanol:nitromethane:H2O. Standard lanes were separated from the rest of the plate and revealed by charring after treatment with 5% H2SO4 in ethanol. The remaining portion of the plate containing the radiolabeled samples was treated with 0.4% PPO (2,5-diphenyloxazole) in 2-methylnaphthalene (Aldrich) to enhance the signal and exposed on photographic film (Amersham) for 24 to 72 h.

Cellobiohydrolase digestion.

One microliter of recombinant cellobiohydrolase from H. insolens (3 mg/ml) was added to the released oligosaccharide sample during the overnight phosphatase treatment. Samples were processed as described above.

RESULTS

S-tag-ExoM is expressed as a membrane-associated protein in E. coli.

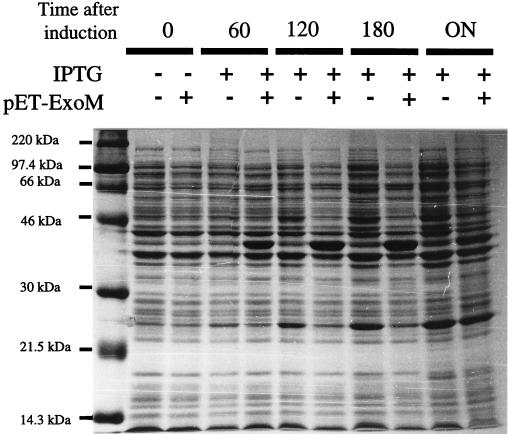

Rather than purifying ExoM activity from S. meliloti, we overexpressed a recombinant form of ExoM in E. coli. In order to facilitate the detection and eventual purification of the recombinant product, ExoM was expressed as an N-terminal fusion with the S-tag epitope. The desired exoM ORF was amplified by PCR from the cosmid pEX154 containing a 14-kb fragment of the symbiotic megaplasmid II of S. meliloti 1021 (21). After the full-length amplified product in pLGC1 had been sequenced, the gene was cloned into the expression vector pET29b to produce pLGC2. The resulting recombinant protein should consist of the predicted 309 amino acids with an N-terminal fusion of 36 amino acids corresponding to the S-tag epitope and a unique thrombin cleavage site with a total predicted molecular mass of 37.5 kDa. Expression of recombinant ExoM was monitored by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2). A significant novel band of approximately 38 kDa was produced by BL21(DE3)/pLysS cells harboring pLGC2 1 h after induction. The relative quantity of recombinant protein appeared to increase up to 3 h after induction but was significantly diminished after overnight culturing. Protein samples were prepared from cultures 2 h after induction. The presence of the S-tag epitope in the new product was confirmed by Western blotting with the alkaline-phosphatase conjugated S-protein (data not shown). The identity of the novel product was further confirmed by thrombin digestion of the crude extract and N-terminal sequencing of the subsequent lower-molecular-mass product appearing in the SDS-PAGE. The sequence determined was in accordance with published results (9).

FIG. 2.

Expression of ExoM. BL21(DE3)/pLysS harboring pET29b (−) or pLGC2 (+) was cultured as described in Materials and Methods. Aliquots were removed before (− and 0) or at different times after IPTG induction (+, 60 min, 120 min, 180 min, and overnight [ON]). Total cell samples were normalized for cell density and analyzed by SDS–12% PAGE.

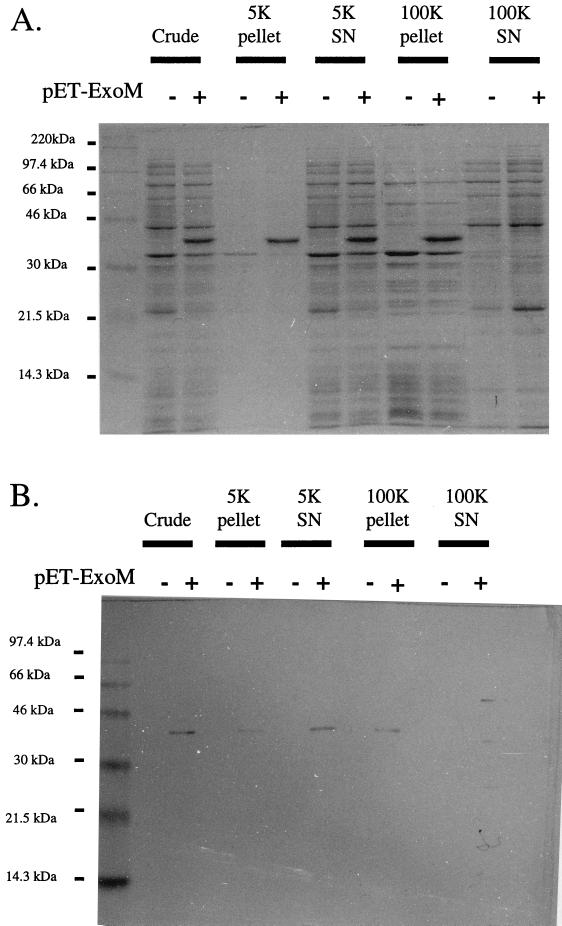

To investigate the localization of the recombinant protein in E. coli, crude French press extracts were subjected to a series of centrifugations, and the protein composition of each fraction was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting against the S-tag epitope (Fig. 3). Equivalent quantities (∼3 μg) of protein from each fraction were precipitated with trichloroacetic acid and used in the analysis. A 5,000 × g centrifugation pelleted a protein fraction very highly enriched with ExoM, suggesting that some portion of the recombinant protein is expressed in the form of an inclusion body. The ExoM remaining in solution after the 5,000 × g centrifugation pelleted at a 100,000 × g centrifugation, suggesting that as predicted by the presence of a C-terminal hydrophobic region, the recombinant protein is membrane bound (9). The recombinant protein pelleted at high speeds could be solubilized in detergents such as 0.5% 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS) or 0.1% Triton X-100, as would be expected for a membrane protein (data not shown). No recombinant protein or enzyme activity could be detected in the supernatant after the high-speed centrifugation. All assays of glycosyltransferase activity were performed with the membrane fraction obtained by high-speed centrifugation.

FIG. 3.

Membrane localization of ExoM. BL21(DE3)/pLysS cells harboring pET29b (−) or pLGC2 (+) were cultured, disrupted, and subjected to 5,000 × g (5K) and 100,000 × g (100K) centrifugations, as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Coomassie blue-stained SDS–12% PAGE gel of each fraction. (B) S-protein blot against S-tag epitope of samples of each fraction. SN, supernatant.

ExoM displays glucosyltransferase activity in vitro.

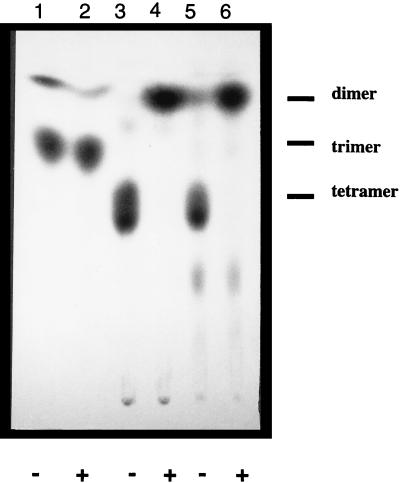

Because the predicted trisaccharide acceptor substrate for ExoM, Glcβ1-4Glcβ1-3Gal, is not commercially available and it was not known at the outset whether a soluble saccharide could replace the natural glycolipid acceptor, mutant strains of S. meliloti were used as a source of authentic glycolipid substrates. The S. meliloti exoMBR triple mutant contains a disruption in exoM, as well as in exoB and exoR. exoB is believed to encode the UDP-4-glucose epimerase which generates the UDP-Gal necessary to initiate succinoglycan biosynthesis, while exoR is a negative regulator of exo gene transcription (24). Therefore, the triple mutant strain accumulates the Glcβ1-4Glcβ1-3Galα-pyrophosphoryl-polyprenol-linked acceptor for ExoM (hereafter referred to as Glc2Gal-PPL) only when provided with exogenous nucleotide sugars. The characterization of the native lipid-linked octasaccharide from wild-type S. meliloti and the glycolipids produced by the mutant strains have been reported previously (24, 28). We found that crude extracts of BL21(DE3)/pLysS, containing pLGC2, but not the pET29b control, were capable of transferring [14C]glucose from UDP-[14C]Glc to the CHCl3:MeOH:H2O (1:2:0.3) lipid-extractable fraction in the presence of unlabeled glycolipids prepared from permeabilized exoMBR mutant cells (Table 2). No incorporation into the CHCl3:MeOH:H2O (1:2:0.3) fraction was observed in the absence of pLGC2 or rhizobial lipids, demonstrating that E. coli possesses no endogenous glucosyltransferase activity and furthermore that the E. coli membranes do not contain a lipid-anchored substrate for ExoM. Following the recombinant ExoM reaction, the CHCl3:MeOH:H2O (1:2:0.3) extract was dried, and the oligosaccharides were released from the lipid anchor by mild acid hydrolysis and subsequently analyzed by TLC, as described in the previous section. The radiolabeled product recovered was found to comigrate with a sample of the expected product Glcβ1-4Glcβ1-4Glcβ1-3Gal (Glc3Gal), isolated from the rhizobial exoOBR triple mutant which accumulates the biosynthetic intermediate corresponding to the ExoM reaction product (Fig. 4) (24). Interestingly, no significant incorporation was detected when the CHCl3:MeOH:H2O (1:2:0.3) fraction from the exoOBR cells was used as the source of glycolipid acceptor (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Crude E. coli extract-mediated [14C]glucose incorporation in rhizobial glycolipids

| Plasmid expressed | S. meliloti glycolipid | Inhibitor (1 mM) | Amt of glucose incorporated (pmol min−1 mg of protein−1) (mean ± SEM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| pET29b | 0.44 ± 0.04 | ||

| pLGC2 | 0.58 ± 0.03 | ||

| pET29b | exoMBR | 0.33 ± 0.09 | |

| pLGC2 | exoMBR | 9.5 ± 0.3 | |

| pLGC2 | exoMBR | Glucose | 9.7 ± 0.4 |

| pLGC2 | exoMBR | Cellobiose | 9.1 ± 1.7 |

| pLGC2 | exoMBR | Glcβ1-4Glcβ1-3Glc | 9.3 ± 0.2 |

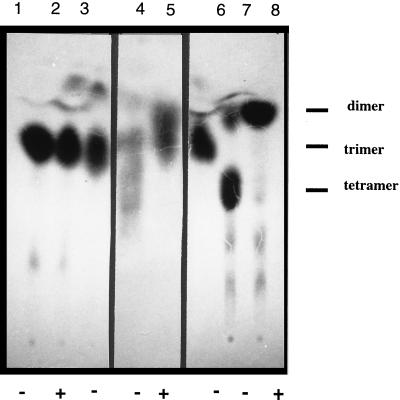

FIG. 4.

TLC analysis of oligosaccharides released after ExoM-mediated transfer of UDP-[14C]Glc to unlabeled rhizobial glycolipids. Lanes 1 and 2, Glc2[14C]Gal isolated from S. meliloti exoMBR triple mutant; lanes 3 and 4, unlabeled Glc2Gal incubated with UDP-[14C]Glc and membranes from E. coli(DE3)/pLysS/pLGC; lanes 5 and 6, Glc3[14C]Gal isolated from S. meliloti exoOBR triple mutant. Dimer, trimer, and tetramer refer to maltobiose, maltotriose, and maltotetraose standards, respectively. Oligosaccharides were treated with (+) or without (−) cellobiohydrolase.

In the converse experiment, in which the glycolipid acceptor prepared with the permeabilized rhizobial cells was labeled with either [14C]glucose or [14C]galactose rather than the nucleotide sugar donor, ExoM was also found to be active. The E. coli membrane fractions expressing ExoM modified the radiolabeled product in the presence of cold UDP-Glc and MgCl2, demonstrating that the observed glucosyltransferase activity is specific for the appropriate acceptor of rhizobial origin (Fig. 5). In this second experiment employing the 14C-labeled glycolipid acceptor, the conversion of the starting substrate into the expected product was detected directly. Under the conditions assayed, the reaction did not go to completion, as both the starting material and the product were detected. These results taken together demonstrate that the gene product of exoM has glucosyltransferase activity towards a specific glycolipid substrate of S. meliloti origin in vitro.

FIG. 5.

TLC analysis of oligosaccharides released after ExoM-mediated transfer of unlabeled UDP-Glc to [14C]galactose-labeled rhizobial lipids. Lanes 1 and 2, [14C]galactose-labeled Glc2Gal standard isolated from S. meliloti exoMBR triple mutant. Lane 3, oligosaccharides released after treatment of [14C]galactose-labeled Glc2Gal-PP lipid with pET29b E. coli membrane preparations. Lanes 4 and 5, oligosaccharides released after treatment of [14C]galactose-labeled Glc2Gal-PP lipid with recombinant ExoM E. coli membrane preparations. Lane 6, oligosaccharide recovered after treatment of lipid-free [14C]galactose-labeled Glc2Gal with recombinant ExoM E. coli membrane preparations. Lanes 7 and 8, [14C]galactose-labeled Glc3Gal standard isolated from S. meliloti exoOBR triple mutant. Dimer, trimer, and tetramer refer to maltobiose, maltotriose, and maltotetraose standards, respectively. Oligosaccharides were analyzed with (+) or without (−) cellobiohydrolase digestion.

The product of ExoM activity is sensitive to cellobiohydrolase degradation.

In order to show that the glycosidic linkage resulting from ExoM activity is in the predicted β1-4 regio- and stereochemistry, the product of the ExoM reaction was treated with the recombinant catalytic domain of cellobiohydrolase II of H. insolens. This cellobiohydrolase recognizes a nonreducing terminal cellotriose sequence (Glcβ1-4Glcβ1-4Glc) and specifically cleaves the β1-4 glucosidic linkage, resulting in the release of cellobiose from the nonreducing terminus (Fig. 1B) (26). As expected, [14C]galactose-labeled trisaccharide (Glcβ1-4Glcβ1-3Gal) from Glc2Gal-PPL substrate acceptor for ExoM is insensitive to the cellobiohydrolase digestion, presumably because the residue adjacent to the cellobiose moiety is β1-3-linked galactose. However, the product of the in vitro reaction with recombinant ExoM, adding an additional glucose residue to either cold or [14C]galactose-labeled acceptor (Fig. 4 and 5), converts the previously insensitive trisaccharide into a cellobiohydrolase-sensitive tetrasaccharide which must now contain the cellotriose structure and a galactose residue. These results strongly suggest that recombinant ExoM catalyzes the formation of a β1-4 glucosidic linkage. Further enzymological investigations of ExoM will require the direct chemical characterization of reaction products derived from either natural or synthetic glycolipid acceptors.

A lipid-anchored substrate is required for ExoM activity.

The study of ExoM would be greatly facilitated if a soluble substrate could be found for the enzyme. In order to determine whether a soluble form of the trisaccharide Glc2Gal could serve as an acceptor for ExoM, [14C]galactose-labeled Glc2Gal-PPL was prepared as described previously. The trisaccharide moiety was then released from the lipid anchor by mild acid hydrolysis, phosphatase treated, and desalted before use in the transferase assay. When equal counts of [14C]galactose-labeled trisaccharide, either in the soluble or in the lipid-anchored form, were employed in the assay, TLC analysis of the products revealed that no conversion of the starting material could be observed when the trisaccharide had been released from the lipid anchor prior to the assay (Fig. 5). In order to determine whether soluble saccharides could inhibit the transfer of [14C]glucose to the Glc2Gal-PPL, glucose, cellobiose, or the trisaccharide analog Glcβ1-4Glcβ1-3Glc was added to the reaction mixture (1 mM final concentration) in addition to the usual quantities of nucleotide sugar, detergent, and Glc2Gal-PPL (Table 2). No significant reduction in the amount of [14C]glucose transfer to the glycolipid fraction was observed. These findings together support the idea that the polyprenyl-pyrophosphate anchor is necessary for the glucosyltransferase activity.

DISCUSSION

Here we report on both the overexpression of an active membrane-associated form of the S. meliloti protein ExoM in E. coli and our results which clearly establish the fact that this recombinant protein is a glucosyltransferase capable of transferring glucose from UDP-Glc to a rhizobial glycolipid in vitro. Furthermore, the fact that the ExoM reaction product is sensitive to digestion by a cellobiohydrolase is consistent with the prediction that ExoM possesses β1-4 glucosyltransferase activity. These results directly confirm in vitro the biosynthetic role previously attributed to the exoM gene product, based on in vivo studies (2, 9, 24). ExoM is the first of the six putative glucosyltransferases involved in the assembly of this biologically important polysaccharide to have been analyzed in vitro.

Many gram-negative bacterial exopolysaccharides, as well as O antigen from lipopolysaccharides and the glycopeptide precursors of peptidoglycan, are assembled from polyprenyl-pyrophosphate-linked subunits (31). In the cases where the lipid anchor has been fully characterized, it is most often found to be undecaprenol (C55). Early studies of the succinoglycan intermediates of S. meliloti have shown that the lipid anchor contains a pyrophosphate and possesses chemical characteristics consistent with the presence of a polyisoprene chain with an unsaturated α-subunit; however, the exact chain length of the polyisoprene carrier is not known (28). We found that ExoM is incapable of transferring glucose to a lipid-pyrophosphate free trisaccharide acceptor, which suggests that some portion of the polyprenyl-pyrophosphate moiety is necessary for the enzyme activity. This finding was somewhat surprising, given that ExoM does not act upon a sugar residue very close to the lipid anchor. However, similar results have been reported for the yeast β1-4 mannosyltransferase (ALG1), which normally acts upon a dolichol-pyrophosphate-linked chitobiose acceptor during the assembly of the N-glycan core oligosaccharide (Glc3Man9GlcNac2-PP-dolichol) (35). In vitro studies employing synthetic glycolipid acceptor analogs have shown that recombinant ALG1 requires the pyrophosphate linkage and a branched lipid anchor for activity (32). The glycosyltransferases involved in the assembly of the polyprenyl-pyrophosphate-linked tetrasaccharide repeat unit of the Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 14 capsular polysaccharide display different substrate requirements. Cps14J is thought to transfer galactose to a lipid-anchored trisaccharide structure in vivo and is active with soluble FCHASE [6-(5-fluorescein-carboxyamido)-hexanoic acid succimyl ester]-derivatized trisaccharide analog in vitro. However, Cps14I, which transfers N-acetylglucosamine to a lipid-linked lactose acceptor in the step preceding the one involving Cps14J, is not active on a soluble FCHASE-derivatized lactose in vitro. The authors speculated that Cps14I has more stringent substrate requirements that may involve the lipid anchor (16).

Only a very limited number of glycosyltransferases which use polyprenyl-pyrophosphate-linked acceptors have been studied in vitro. It is not clear, even in the case of ALG1, exactly what role the lipid anchor plays in substrate recognition or if its recognition is a general phenomenon. It has been proposed that the membrane anchor of glycosyltransferases involved in N-glycan assembly may be involved in recognition of the dolichol anchor of the oligosaccharide acceptor substrate (1). However, in the case of ALG1, the acceptor lipid anchor is still required for transferase activity, even after the transmembrane region of the mannosyltransferase has been removed (32). In addition, preliminary results from our laboratory indicate that AceA, a soluble recombinant mannosyltransferase from A. xylinum involved in acetan biosynthesis, is also incapable of transferring mannose to a lipid-pyrophosphate free cellobiose acceptor (8a). These findings suggest that it is not merely the presence of a transmembrane region that renders the glycosyltransferase sensitive to the presence or absence of the acceptor lipid anchor. The production of a soluble form of ExoM with which to investigate the role of the putative C-terminal transmembrane region in substrate recognition is currently under way in our laboratory.

The purification of native rhizobial glycolipid substrates on a large scale and the preparation of synthetic glycolipid analog substrates will allow more detailed investigations of ExoM in vitro. Future points to investigate include the influence of nonglycosidic substrate modifications (e.g., O-acetylation) upon ExoM activity, the minimal acceptor structure requirements for the enzymatic activity (including features of the lipid anchor), and divalent cation usage. The reaction catalyzed by ExoM, i.e., the transfer of glucose from UDP-Glc to a Glcβ1-4Glc-containing acceptor, is very close to the reaction performed processively by cellulose synthase in the production of the cellulose [(Glcβ1-4Glc)n]. Aside from domain A and the conserved aspartic acid residues, ExoM and bacterial cellulose synthases have no significant overall sequence similarity (25). Our findings support the assumption that ExoM is a nonprocessive glucosyltransferase, as we have found no evidence for the addition of more than one sugar residue under the conditions tested. However, as ExoM is one of the rare glucosyltransferases (other than cellulose synthases) to catalyze the formation of a Glcβ1-4Glc structure, further studies on the molecular mechanisms of ExoM may also provide useful insight into the biosynthesis of cellulose.

S. meliloti mutants producing glycolipid intermediates corresponding to almost every step in the assembly of the succinoglycan octasaccharide subunit have been described, and thus a similar strategy to that presented here can be applied to the initial study of each of the other exo cluster glucosyltransferases as well (24). For example, ExoL is required in vivo for the addition of the third saccharide residue (β1-4Glc, like ExoM) to the lipid anchor, generating Glcβ1-4Glcβ1-3Gal-pyrophosphate lipid. However, ExoL does not possess any detectable similarity to any currently known glycosyltransferase (18a). It is tempting to speculate that if this gene product catalyzes the formation of a β1-4Glc linkage, it may function differently than the other Exo glucosyltransferases, perhaps not employing a nucleotide sugar donor. Alternatively, ExoL alone may not be directly responsible for the glucose transfer. An in vitro study, analogous to the one described here and employing recombinant ExoL, will allow us to directly determine the function of this unusual protein also involved in succinoglycan biosynthesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank G. C. Walker for kindly providing the cosmid pEX154 and the rhizobial strains, Valerie Chazalet for her expert technical assistance, and Sabine Flitsch for helpful advice. The N-terminal amino acid sequence of recombinant ExoM was determined by Jean Gagnon, Institut de Biologie Structurale, Grenoble, France.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albright C F, Orlean P, Robbins P W. A 13 amino acid peptide in three yeast glycosyltransferases may be involved in dolichol recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:7366–7369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.19.7366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Battisti L, Lara J C, Leigh J A. Specific oligosaccharide form of the Rhizobium meliloti exopolysaccharide promotes nodule invasion in alfalfa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5625–5629. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becker A, Kleickmann A, Keller M, Arnold W, Pühler A. Identification and analysis of the Rhizobium meliloti exoAMONP genes involved in exopolysaccharide biosynthesis and mapping of promoters located on the exoHKLAMONP fragment. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;241:367–379. doi: 10.1007/BF00284690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Becker A, Kleickmann A, Küster H, Keller M, Arnold W, Pühler A. Analysis of the Rhizobium meliloti genes exoU, exoV, exoW, exoT, and exoI involved in exopolysaccharide biosynthesis and nodule invasion: exoU and exoW probably encode glucosyltransferases. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1993;6:735–744. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-6-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Becker A, Küster H, Niehaus K, Pühler A. Extension of the Rhizobium meliloti succinoglycan biosynthesis gene cluster: identification of the exsA gene encoding an ABC transporter protein, and the exsB gene which probably codes for a regulator of succinoglycan biosynthesis. Mol Gen Genet. 1995;249:487–497. doi: 10.1007/BF00290574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breton C, Bettler E, Joziasse D, Geremia R, Imberty A. Sequence-function relationships in prokaryotic and eukaryotic galactosyltransferases. J Biochem. 1998;123:1000–1009. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Busch C, Hofmann F, Selzer J, Munro S, Jeckel D, Aktories K. A common motif of eukaryotic glycosyltransferases is essential for the enzyme activity of large clostridial cytotoxins. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:19566–19572. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.31.19566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng H-P, Walker G C. Succinoglycan is required for the initiation and elongation of infection threads during nodulation of alfalfa by Rhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5183–5191. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.19.5183-5191.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8a.Geremia, R. A. Personal communication.

- 9.Glucksmann M A, Rueber T L, Walker G C. Family of glycosyltransferases needed for the synthesis of succinoglycan by Rhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7033–7044. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.21.7033-7044.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glucksmann M A, Rueber T L, Walker G C. Genes needed for the modification, polymerization, export, and processing of succinoglycan by Rhizobium meliloti: a model for succinoglycan biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7045–7055. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.21.7045-7055.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.González J E, Semino C E, Wang L-X, Castellano-Torres L E, Walker G C. Biosynthetic control of molecular weight in the polymerization of the octasaccharide subunits of succinoglycan, a symbiotically important exopolysaccharide of Rhizobium meliloti. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13477–13482. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gonzalez J E, York G M, Walker G C. Rhizobium meliloti exopolysaccharides: synthesis and symbiotic function. Gene. 1996;179:141–146. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00322-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gravanis G, Milas M, Rinaudo M, Clarke-Sturman A J. Rheological behavior of a succinoglycan polysaccharide in dilute and semi-dilute solutions. Int J Biol Macromol. 1990;12:201–206. doi: 10.1016/0141-8130(90)90033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ielpi L, Couso R O, Dankert M A. Sequential assembly and polymerization of the polyprenol-linked pentasaccharide repeating unit of the xanthan polysaccharide in Xanthomonas campestris. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2490–2500. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.9.2490-2500.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keenleyside W J, Whitfield C. A novel pathway for O-polysaccharide biosynthesis in Salmonella enterica serovar Borreze. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:28581–28592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.45.28581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kolkman M A B, Wakarchuk W, Nuijten P J M, van der Zeijst B A M. Capsular polysaccharide synthesis in Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 14: molecular analysis of the complete cps locus and identification of genes encoding glycosyltransferases required for the biosynthesis of the tetrasaccharide subunit. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:197–208. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5791940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leigh J A, Signer R, Walker G C. Exopolysaccharide deficient mutants of Rhizobium meliloti that form ineffective nodules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:6231–6235. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.18.6231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leigh J A, Walker G C. Exopolysaccharides of Rhizobium: synthesis, regulation and symbiotic function. Trends Genet. 1994;10:63–67. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(94)90151-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18a.Lellouch, A. C. Personal communication.

- 19.Long S, Reed J W, Himawan J, Walker G C. Genetic analysis of a cluster of genes required for synthesis of the Calcofluor-binding exopolysaccharide of Rhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4239–4248. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.9.4239-4248.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matusdaira P. Sequence from picomole quantities of proteins electroblotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:10035–10038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reed J W, Capage M, Walker G C. Rhizobium meliloti exoG and exoJ mutations affect the ExoX-ExoY system for modulation of exopolysaccharide production. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:3776–3788. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.12.3776-3788.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reinhold B R, Chan S Y, Reuber T L, Marra A, Walker G C, Reinhold V N. Detailed structural characterization of succinoglycan, the major exopolysaccharide of Rhizobium meliloti Rm1021. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1997–2002. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.7.1997-2002.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reuber T L, Long S, Walker G C. Regulation of Rhizobium meliloti exo genes in free-living cells and in planta examined by using TnphoA fusions. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:426–434. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.426-434.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reuber T L, Walker G C. Biosynthesis of succinoglycan, a symbiotically important exopolysaccharide of Rhizobium meliloti. Cell. 1993;74:269–280. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90418-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saxena I M, Brown R M, Jr, Fevre M, Geremia R A, Henrissat B. Multidomain architecture of β-glycosyl transferases: implications for mechanism of action. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1419–1424. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.6.1419-1424.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schülein M. Enzymatic properties of cellulases from Humicola insolens. J Biotechnol. 1997;57:71–81. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1656(97)00090-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Semino C E, Dankert M A. In vitro biosynthesis of acetan using electroporated Acetobacter xylinum cells as enzyme preparations. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:2745–2756. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-11-2745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tolmasky M E, Staneloni R J, Leloir L F. Lipid-bound saccharides in Rhizobium meliloti. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:6751–6757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Urzainqui A, Walker G C. Exogenous suppression of the symbiotic deficiencies of Rhizobium meliloti exo mutants. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3403–3406. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.10.3403-3406.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Rhijn P, Vanderleyden J. The Rhizobium-plant symbiosis. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:124–142. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.1.124-142.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Warren C D, Jeanloz R W. Chemical synthesis of pyrophosphodiesters of carbohydrates and isoprenoid anchors. Lipid intermediates of bacterial cell wall and antigenic polysaccharide biosynthesis. Biochemistry. 1972;11:2565–2572. doi: 10.1021/bi00764a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watt G M, Revers L, Webberley M C, Wilson I B H, Flitsch S L. The chemo-enzymatic synthesis of the core trisaccharide of N-linked oligosaccharides using a recombinant β-mannosyltransferase. Carbohydr Res. 1998;305:533–541. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(97)00261-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whitfield C, Valvano M A. Biosynthesis and expression of cell-surface polysaccharides in gram-negative bacteria. Adv Microb Physiol. 1993;35:135–246. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(08)60099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wiggins C A, Munro S. Activity of the yeast MNN1 alpha 1-3 mannosyltransferase requires a motif conserved in many other families of glycosyltransferases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;14:7945–7950. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.7945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilson I B H, Webberley M C, Revers L, Flitsch S L. Dolichol is not a necessary moiety for lipid-linked oligosaccharide substrates of the mannosyltransferases involved in in vitro N-linked-oligosaccharide assembly. Biochem J. 1995;310:909–916. doi: 10.1042/bj3100909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]