Abstract

The advent of immune checkpoint inhibitors for recurrent/metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (RM-HNSCC) has revolutionized the standard of care approach in first-line treatment. The heterogeneity of disease presentation and treatment-related toxicities can be associated with suboptimal patient compliance to oncologic care. Hence, prioritizing quality of life and well-being are crucial aspects to be considered in tailoring the best treatment choice. The aim of our work is to present a short report on the topic of the patient’s preference in regard to treatment and its consequences on quality of life in the recurrent/metastatic setting. According to the literature, there’s an unmet need on how to assess patient attitude in respect to the choice of treatment. In view of the availability of different therapeutic strategies in first-line management of RM-HNSCC, increasing emphasis should be put on integrating patient preferences into the medical decision-making.

Keywords: Immunotherapy, Pembrolizumab, Recurrent or metastatic HNSCC, Patient’s preference, Quality of life

Abstract

L'avvento degli inibitori del checkpoint immunitario per il carcinoma squamocellulare ricorrente/metastatico del distretto testa e collo (RM-HNSCC) ha rivoluzionato l'approccio standard di cura nel trattamento di prima linea di questa malattia. L'eterogeneità di presentazione del RM-HNSCC e le tossicità correlate al trattamento possono essere associate a una compliance non ottimale del paziente alle cure oncologiche. Per tale ragione, qualità della vita e benessere del paziente sono aspetti cruciali da considerare per definire la migliore scelta di trattamento. Lo scopo del nostro lavoro è presentare una panoramica sul tema della preferenza del paziente rispetto al trattamento e delle sue conseguenze sulla qualità della vita in ambito di malattia recidivante/metastatica. Secondo la letteratura infatti, esiste un'esigenza concreta su come valutare l'atteggiamento del paziente rispetto alla scelta del trattamento. In considerazione della disponibilità di diverse strategie terapeutiche nella gestione di prima linea di RM-HNSCC, si dovrebbe dunque porre maggiore enfasi sull'integrazione delle preferenze del paziente nell’individuazione dell’iter terapeutico.

Introduction

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is the seventh most common cancer worldwide [1]. Distant metastases and/or local recurrence after primary curative treatment occur in about half of patients with locally advanced HNSCC. Approximately 5% of patients have upfront metastases [2]. The prognosis of recurrent/metastatic HNSCC (RM-HNSCC) remains extremely poor with a median overall survival (OS) of about one year [3–5]. Until the publication of the results of Keynote-048 trial, the standard of care of RM-HNSCC was cetuximab plus chemotherapy with platinum and 5-fluorouracil [4]. Immunotherapy for RM-HNSCC has provided promising results and the “one-size-fits-all-approach” in first-line therapy has recently changed [5, 6]. Notwithstanding the progress achieved in the selection of first-line therapy, the treatment for RM-HNSCC remains an open question due to the heterogeneity of patients’ characteristics, symptoms burden and disease presentation. All these factors—performance status, age, comorbidities, need of quick tumor response and PD-L1 Combined Positive Score (CPS)—are simultaneously the main aspects to be considered in the decision-making. However, recurrent and metastatic head and neck patients may suffer from complications such as infections, nutritional issues and voice alterations that negatively affect their quality of life. Moreover, the adverse events of therapy are crucial aspects to be taken into account in the management of HNSCC patients. The aggressiveness of treatment-related toxicities can contribute to refusal of therapeutic options and/or premature interruption of oncologic care, especially in vulnerable populations [7–11]. The aim of our work is to present a critical overview on the topic of the patient’s preference in regard to treatment and its consequences on quality of life in the recurrent/metastatic setting.

Preferences and priorities of head and neck cancer patients

HNSCC poses a significant burden on HRQoL. Impairments of the anatomic structures involved in breathing, speech and swallowing can occur as the results of the disease itself or can be caused by aggressive treatments [12, 13]. With this regard, patients with HNSCC commonly develop remarkable social isolation and psychological distress [14]. Maintaining HRQoL and psychological well-being are crucial aspects in the management of treatment and independent prognostic factors for survival, especially in RM-HNSCC patients [15–20].

This highlights the relevance of the patients’ perspective as a variable outcome in addition to survival, recurrence or physical impairment [10]. Even though the questionnaire-based evaluation of HRQoL is mostly adopted in clinical trials, we, as others, truly believe that in clinical practice the perception of disease and treatment of each patient remain challenging to investigate. In addition to the negative effects of treatments on HRQoL, patients with RM-HNSCC have to deal with their poor prognosis. Recently, pembrolizumab in combination with platinum/5-FU and pembrolizumab monotherapy have yielded a significant survival benefit compared to the EXTREME regimen in first-line treatment for RM-HNSCC [5, 21]. In addition to the PD-L1 combined positive score (CPS) result, in PS 0–1 patients the choice between the combination of pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy and immunotherapy alone is mostly driven by the need of a rapid tumor shrinkage. Therefore, for RM-HNSCC with persistence of locoregional disease, high risk of airways obstruction and consequent need of quick tumor response the combination of chemotherapy plus immunotherapy can be recommended as preferential option [6].

However, the pembrolizumab monotherapy can be an optimal choice for “hard-to-approach” RM-HNSCC patients thanks to its triweekly schedule, short infusion time for drug administration, no need for central venous access devices and good tolerability profile.

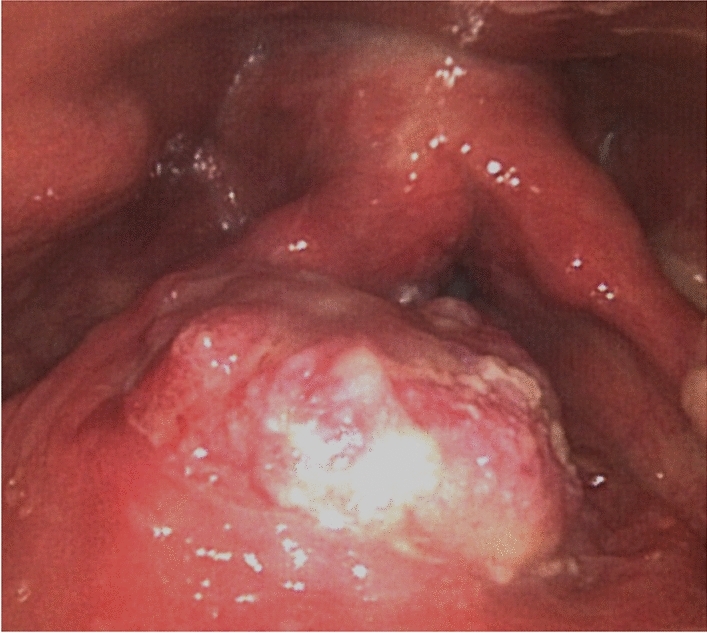

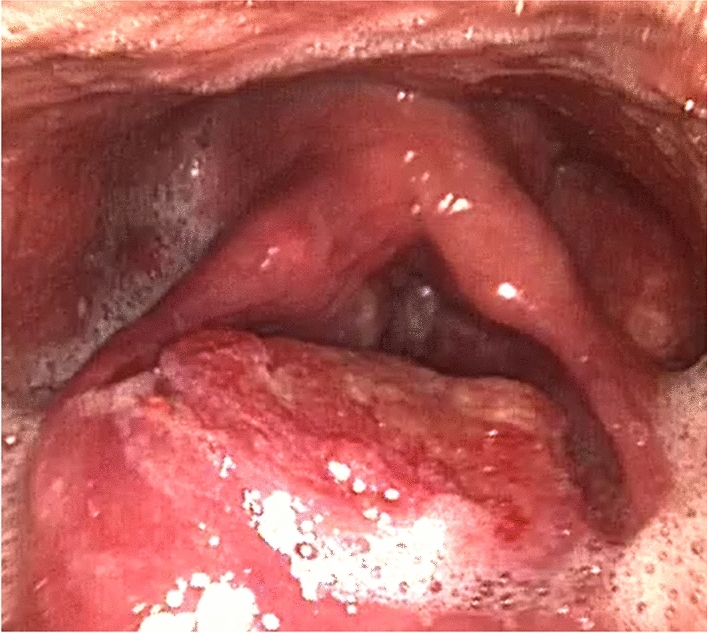

Of note, we recently examined a paradigmatic example of a RM-HNSCC patient treated with pembrolizumab monotherapy due to the refusal of chemo-based treatment options. The patient presented with a SCC of the larynx (Fig. 1). Contrast-enhanced (CE) computed tomography (CT) scan and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) imaging were recommended as imaging workup [22, 23] but the patient refused to perform any further diagnostic-therapeutic approach. Two months after the refusal, he presented with progressive disease (cT4aN2cM1, IVc stage) with CPS of 1 or more preferring a “chemo-free” approach with pembrolizumab monotherapy. Currently, he has received 7 cycles of immunotherapy with unaffected well-being and clinical stability of disease (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Fiberoptic endoscopy at the first clinical evaluation

Fig. 2.

Fiberoptic endoscopy after seven cycles of pembrolizumab

Although disease- and treatment-related aspects represent the key components in the management of RM-HNSCC, patient-related factors such as availability of caregivers, patients’ quality of life, need and preferences should be simultaneously considered [11] and our experience is a representative example of this need.

Increasingly, patients are involved in medical decisions about oncological treatments using tradeoffs between survival benefits and exceeding morbidity from treatment [24, 25]. In HNSCC, the importance of providing increased survival while maximizing patients' quality of life and well-being has been known for many years. More than 40 years ago, McNeil et al. [25] published attitudinal data toward survival and artificial speech of 37 volunteers with stage T3 laryngeal cancer. Up to 20 per cent of the interviewed patients would choose radiation therapy instead of surgery in order to preserve voice suggesting that treatment choice should be made on the basis of preference about the quality as well as the quantity of survival.

Although data about patients' perspectives of treatments remain still limited, it is well known that psychosocial distress caused by HNSCC diagnosis and treatment-related toxicities may lead patients to refusal or interruption of oncological care. In recent decades, some authors focused their effort on analyzing the subset of head and neck patients who are inclined to refuse treatment reporting that 1.3–1.7% of patients with HNSCC refused surgical- and/or radiotherapy-based definitive therapy [15–26].

According to the analysis of 797 patients with unresectable and metastatic tumors who did not perform any sort of treatment in a single center experience, 19% of patients refused therapy based on their personal choice [27]. Moreover, Choi et al. [28] documented that 32.2% did not receive any treatment and identified the advanced age, worse socioeconomic status and lip/oral cavity tumor as the main risk factors related to patient refusal of care.

A retrospective experience of 35,834 patients reported a rate of untreated patients of 10%. The main factors associated with treatment failure were the higher stage of the disease, pharyngeal site and black race [29]. A more recent analysis published by Cheraghlou et al. [30] including 36,261 patients with resectable oral cavity cancer documented a rate of treatment failure of about 1%. Similarly, the higher primary tumor and nodal stage, age of 75 years or older, insurance status and treatment at low/intermediate volume facilities were associated with a patient's likelihood of refusing treatment.

However, there is a large unmet medical need as well as a lack of evidence on tools to assess the preferences of HNSCC patients in regard to treatment and its consequences on several life aspects (Table 1).

Table 1.

Studies assessing preferences and priorities of head and neck cancer patients

| Studies assessing preferences and priorities of head and neck cancer patients | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study [Ref] | Institution | Date | N° of HNC pts | No of laryngeal cancer pts (%) | RM HNC patients | Instrument | Main findings |

| Jalukar [34] | University of Iowa, USA | 1998 | 49 | NS | NI | TTO |

Healthcare professionals and patients have similar attitudes regarding the desirability of potential health-state outcomes within the HNC-specific domains of eating, speech, appearance and breathing |

| Sharp [35] | University of Chicago, USA | 1998 | 20 | 2 (10%) | NI | Ranking (CPS, design of the scale) | Being cured/live longer was first priority |

| List [33] | Multi-institution, USA | 2000 | 131 | 36 (27%) | NS | Ranking (CPS, FACT-HN, PSSHN) | Cure ranked first for 75% of pts, then living long, having no pain, energy, swallowing, voice and appearance |

| Gill [36] | Newcastle, UK | 2007 | 30 | NS | NI | Ranking (CPS, Ottawa DRS) | Being cured/live longer uniformly ranked first, pain and swallowing items ranked next, but with varying scores |

| Kanatas [37] | Liverpool, UK | 2011 | 447 | 186 (42%) | NI | Ranking (PCI, UW-QoL) |

Fear of recurrence was the first concern, then issues more specific to each disease such as speech (larynx) and salivation (oropharynx) Variation by age (less fear of recurrence in among elderly pts) |

| Tschiesner [32] | Munich, Germany | 2013 | 300 | 130 (43%) | NS | Ranking (ICFHNC) | Survival ranked first (but only by 58% of pts), all expenses for cancer treatment being covered 2nd (51%), being able to continue performing all daily life activities well (50%) |

| Windon [38] | Baltimore, USA | 2020 | 150 | 18 (12%) | NS | Ranking (CPS) | Top three priority were cure, survival and swallow. Prioritization of cure, survival and swallow was similar by human papillomavirus (HPV) tumor status. By increasing decade of age, older participants were significantly less likely than younger to prioritize survival |

| Bonomo [31] | 7 institutions worldwide | 2020 | 111 | 15 (13.5%) | 20 (23%) | Ranking (list of issues from a phase I-II study) | Cure of disease, survival-live as long as possible and trusting in health care providers were the 3 most common priorities |

| Mc Neil [25] | Boston, USA | 1981 | 37 | 37 (100%) | NI | TTO | 20% of pts would choose radiation therapy instead of surgery in order to preserve voice |

| Otto [39] |

UT San Antonio, USA |

1997 | 46 | 46 (100%) | NI | TTO | Only 20% of pts willing to trade survival for function, by a mean of 5.6 years |

| Van der Donk [40] | Rotterdam, Netherlands | 1995 | 20 | 10 (50%) | NI | TTO, SG, RS, DC | Most respondents preferred RT alone; utilities always higher for RT alone than TL |

CPS, Chicago Priority Scale; DRS, Decision Regret Scale; FACT-HN, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Head and Neck; HNC, head and neck cancer; recurrent/metastatic HNC (RM HNC); ICF-HNC, International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Core Set for Head and Neck Cancer; PSS-HN, Performance Status Scale for Head and Neck Cancer; PCI, patient concerns inventory; pts, patients; S, subject; UW-QOL, University of Washington Head and Neck Cancer Questionnaire; DC, direct comparison; HNC, head and neck cancer; RS, rating scale; SG, standard gamble; TL, total laryngectomy; TTO, Time Trade Off; RT, radiotherapy; NI, not included; NS, not specified

Currently, the methods used to assess the preferences of patients with head and neck cancer are heterogeneous and the gold standard is still missing.

Interestingly, a recent prospective phase I–II study has been published with the purpose to develop a HNSCC patients’ preference questionnaire. Among the final list of items for patients’ preferences, “cure of disease,” “survival-live as long as possible” and “trusting in health care providers” were the three most common priorities in 87.3%, 73.6% and 59.1% of patients, respectively [31].

Similarly, some authors (Table 1) focused their investigation on identifying the checklist of priorities for this population in regard to long-term treatment effects. Although the item of “being cured/living longer” was uniformly ranked first [32–35], in the Gill et al. [36] assessment also no pain and swallow preservation were indicated as the main priorities for HNSCC interviewed patients. Additionally, Kanatas et al. [37] showed that also fear of recurrence was common to all clinical groups and speech issues were much more considered by laryngeal cancer patients than other subgroups of HNSCC. In a more recent publication, Windon et al. [38] investigated the perspective and preference of a prospective cohort of 150 HNSCC patients, confirming that oncological treatments and benefits in terms of survival were the two most priorities.

Although we found a wide heterogeneity of data from the head and neck cancer patients, remarkable findings were reported in the papers of larynx preservation. This subgroup of site-specific studies [25, 39, 40] interviewed the patients using similar questions in regard to the utility of laryngectomy health state or the tradeoff between survival and laryngectomy. Moreover, the patients’ preference tool used by the authors was mostly time trade-off and the results were much more homogeneous. Contrary to the previous papers assessing ranking of preference and priority, the main findings from studies on laryngeal preservation suggested that ‘‘live longer” is not the main expectancy. Laryngeal cancer patients mostly preferred radiation treatment alone or in combination with chemotherapy than laryngectomy in order to preserve voice and speech [25, 39–42]. Notably, the inclusion of RM HNSCC in the aforementioned experiences is underrepresented (22% of patients in the subgroup of palliative treatment [31]) or completely missing.

Conclusions

Ideally, the development of a comprehensive questionnaire assessing the heterogeneous domains of preference may allow to fully integrate also the RM-HNSCC patients’ priorities in the medical decision. Prospective studies designed to integrate patients’ needs and preferences in the optimal choice of first-line treatment are warranted.

Authors' contribution

PB Conceptualization; Investigation; Methodology; Writing—original draft. VS Investigation; Methodology; Writing—original draft. CB Investigation; Methodology; Validation; Visualization; Writing—review and editing. ID Investigation; Writing—original draft. LC Writing—original draft. MM Writing—original draft. MB Investigation; Methodology; Validation; Visualization; Writing—review and editing. NP Writing—review and editing. VS Investigation; Writing—original draft. LL Investigation; Writing—original draft. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Firenze within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. Funding was received for this work.

Availability of data and material

Data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical approval

Research involving human participants, their data or biological material: ethical approval was waived by the local Ethics Committee of University of Florence/Area Vasta Centro in view of the retrospective nature of the study, and all the procedures being performed were part of the routine care.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained by the individual patient whose clinical history is briefly described.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leeman JE, Li JG, Pei X, et al. Patterns of treatment failure and postrecurrence outcomes among patients with locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma after chemoradiotherapy using modern radiation techniques. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(11):1487–1494. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Argiris A, Harrington KJ, Tahara M, et al. Evidence-based treatment options in recurrent and/or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Front Oncol. 2017;7:72. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2017.00072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vermorken JB, Mesia R, Rivera F, et al. Platinum-based chemotherapy plus cetuximab in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1116–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burtness B, Harrington KJ, Greil R, et al. Pembrolizumab alone or with chemotherapy versus cetuxumab with chemotherapy for recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (KEYNOTE-048): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2019;394:1915–1928. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32591-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Machiels JP, René Leemans C, Golusinski W, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity, larynx, oropharynx and hypopharynx: EHNS-ESMO-ESTRO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(11):1462–1475. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sethi RA, Stamell EF, Price L, et al. Head and neck radiotherapy compliance in an underserved patient popu-lation. Laryngoscope. 2010;120:1336–1341. doi: 10.1002/lary.20963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas K, Martin T, Gao A, Ahn C, Wilhelm H, Schwartz DL (2017 ) Interruptions of head and neck radiotherapy across insured and indigent patient populations [published correction appears in J Oncol Pract. Jul;13(7):466]. J Oncol Pract 13(4):e319–e328. 10.1200/JOP.2016.017863 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Hassan SJ, Weymuller EA., Jr Assessment of quality of life in head and neck cancer patients. Head Neck. 1993;15:485–496. doi: 10.1002/hed.2880150603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ringash J. Survivorship and quality of life in head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3322–3327. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.4115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oliveira TB, Mesía R, Falco A, et al. Defining the needs of patients with recurrent and/or metastatic head and neck cancer: an expert opinion. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021;157:103200. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2020.103200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Licitra L, Mesía R, Keilholz U. Individualised quality of life as a measure to guide treatment choices in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Oral Oncol. 2016;52:18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amini A, Verma V, Li R, et al. Factors predicting for patient refusal of head and neck cancer therapy. Head Neck. 2020;42(1):33–42. doi: 10.1002/hed.25966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fan CY, Chao HL, Lin CS, et al. Risk of depressive disorder among patients with head and neck cancer: a nationwide population-based study. Head Neck. 2018;40:312–323. doi: 10.1002/hed.24961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Urba S, Gatz J, Shen W, et al. Quality of life scores as prognostic factors of overall survival in advanced head and neck cancer: analysis of a phase III randomized trial of pemetrexed plus cisplatin versus cisplatin monotherapy. Oral Oncol. 2012;48:723–729. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ringash J, Bezjakn A. A structured review of quality of life instruments for head and neck cancer patients. Head Neck. 2001;23:201–213. doi: 10.1002/1097-0347(200103)23:3<201::AID-HED1019>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mesia R, Rivera F, Kawecki A, et al. Quality of life of patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy plus cetuximab first line for recurrent and/or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1967–1973. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Machiels JP, Haddad RI, Fayette J, et al. Afatinib versus methotrexate as second-line treatment in patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck progressing on or after platinum-based therapy (LUX-Head & Neck 1): an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:583–594. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70124-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ojo B, Genden EM, Teng MS, et al. A systematic review of head and neck cancer quality of life assessment instruments. Oral Oncol. 2012;48:923–937. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vartanian JG, Rogers SN, Kowalski LP. How to evaluate and assess quality of life issues in head and neck cancer patients. Curr Opin Oncol. 2017;29(3):159–165. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cramer JD, Burtness B, Le QT, Ferris RL. The changing therapeutic landscape of head and neck cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2019;16:669–683. doi: 10.1038/s41571-019-0227-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pietragalla M, Nardi C, Bonasera L, et al. Current role of computed tomography imaging in the evaluation of cartilage invasion by laryngeal carcinoma. Radiol Med. 2020;125(12):1301–1310. doi: 10.1007/s11547-020-01213-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mazzola R, Alongi P, Ricchetti F, et al. 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose-PET/CT in locally advanced head and neck cancer can influence the stage migration and nodal radiation treatment volumes. Radiol Med. 2017;122(12):952–959. doi: 10.1007/s11547-017-0804-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blanchard P, Volk RJ, Ringash J, Peterson SK, Hutcheson KA, Frank SJ. Assessing head and neck cancer patient preferences and expectations: a systematic review. Oral Oncol. 2016;62:44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McNeil BJ, Weichselbaum R, Pauker SG. Speech and survival: tradeoffs between quality and quantity of life in laryngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1981;305(17):982–987. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198110223051704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sahovaler A, Gualtieri T, Palma D, et al. Head and neck cancer patients declining curative treatment: a case series and literature review. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2021;41(1):18–23. doi: 10.14639/0392-100X-N1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kowalski LP, Carvalho AL. Natural history of untreated head and neck cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36:1032–1037. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi HG, Park B, Ahn SH. Untreated head and neck cancer in Korea: a national cohort study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;274:1643–1650. doi: 10.1007/s00405-016-4392-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hughley BB, Sperry SM, Thomsen TA, et al. Survival outcomes in elderly patients with untreated upper aerodigestive tract cancer. Head Neck. 2017;39:215–218. doi: 10.1002/hed.24565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheraghlou S, Kuo P, Mehra S, et al. Untreated oral cavity cancer: long-term survival and factors associated with treatment refusal. La-ryngoscope. 2018;128:664–669. doi: 10.1002/lary.26809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bonomo P, Maruelli A, Saieva C, et al. Assessing preferences in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: phase I and II of questionnaire development. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12(12):3577. doi: 10.3390/cancers12123577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tschiesner U, Sabariego C, Linseisen E, et al. Priorities of head and neck cancer patients: a patient survey based on the brief ICF core set for HNC. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;270(12):3133–3142. doi: 10.1007/s00405-013-2446-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.List MA, Stracks J, Colangelo L, et al. How Do head and neck cancer patients prioritize treatment outcomes before initiating treatment? J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(4):877–884. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.4.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jalukar V, Funk GF, Christensen AJ, Karnell LH, Moran PJ. Health states following head and neck cancer treatment: patient, health-care professional, and public perspectives. Head Neck. 1998;20(7):600–608. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0347(199810)20:7<600::aid-hed4>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharp HM, List M, MacCracken E, Stenson K, Stocking C, Siegler M. Patients' priorities among treatment effects in head and neck cancer: evaluation of a new assessment tool. Head Neck. 1999;21(6):538–546. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0347(199909)21:6<538::aid-hed7>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gill SS, Frew J, Fry A, et al. Priorities for the head and neck cancer patient, their companion and members of themultidisciplinary team and decision regret. Clin Oncol R Coll Radiol G B. 2011;23:518–524. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2011.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kanatas A, Ghazali N, Lowe D, et al. Issues patients would like to discuss at their review consultation: variation by early and late stage oral, oropharyngeal and laryngeal subsites. Eur Arch Oto-Rhino Laryngol Off J Eur Fed Oto-Rhino-Laryngol Soc EUFOS Affil Ger Soc Oto-Rhino-Laryngol - Head Neck Surg. 2013;270:1067–1074. doi: 10.1007/s00405-012-2092-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Windon MJ, D'Souza G, Faraji F, et al. Priorities, concerns, and regret among patients with head and neck cancer. Cancer. 2019;125(8):1281–1289. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Otto RA, Dobie RA, Lawrence V, Sakai C. Impact of a laryngectomy on quality of life: perspective of the patient versus that of the health care provider. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1997;106:693–699. doi: 10.1177/000348949710600815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van der Donk J, Levendag PC, Kuijpers AJ, et al. Patient participation in clinical decision-making for treatment of T3 laryngeal cancer: a comparison of state and process utilities. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2369–2378. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.9.2369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luo XN, Chen LS, Zhang SY, Lu ZM, Huang Y. Effectiveness of chemotherapy and radiotherapy for laryngeal preservation in advanced laryngeal cancer: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Radiol Med. 2015;120(12):1153–1169. doi: 10.1007/s11547-015-0547-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dias LM, Bezerra MR, Barra WF, Rego F. Refusal of medical treatment by older adults with cancer: a systematic review. Ann Palliat Med. 2021;10:4868–4877. doi: 10.21037/apm-20-2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.