Abstract

Pyrococcus furiosus is a hyperthermophilic archaeon which grows optimally near 100°C by fermenting peptides and sugars to produce organic acids, CO2, and H2. Its growth requires tungsten, and two different tungsten-containing enzymes, aldehyde ferredoxin oxidoreductase (AOR) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate ferredoxin oxidoreductase (GAPOR), have been previously purified from P. furiosus. These two enzymes are thought to function in the metabolism of peptides and carbohydrates, respectively. A third type of tungsten-containing enzyme, formaldehyde ferredoxin oxidoreductase (FOR), has now been characterized. FOR is a homotetramer with a mass of 280 kDa and contains approximately 1 W atom, 4 Fe atoms, and 1 Ca atom per subunit, together with a pterin cofactor. The low recovery of FOR activity during purification was attributed to loss of sulfide, since the purified enzyme was activated up to fivefold by treatment with sulfide (HS−) under reducing conditions. FOR uses P. furiosus ferredoxin as an electron acceptor (Km = 100 μM) and oxidizes a range of aldehydes. Formaldehyde (Km = 15 mM for the sulfide-activated enzyme) was used in routine assays, but the physiological substrate is thought to be an aliphatic C5 semi- or dialdehyde, e.g., glutaric dialdehyde (Km = 1 mM). Based on its amino-terminal sequence, the gene encoding FOR (for) was identified in the genomic database, together with those encoding AOR and GAPOR. The amino acid sequence of FOR corresponded to a mass of 68.7 kDa and is highly similar to those of the subunits of AOR (61% similarity and 40% identity) and GAPOR (50% similarity and 23% identity). The three genes are not linked on the P. furiosus chromosome. Two additional (and nonlinked) genes (termed wor4 and wor5) that encode putative tungstoenzymes with 57% (WOR4) and 56% (WOR5) sequence similarity to FOR were also identified. Based on sequence motif similarities with FOR, both WOR4 and WOR5 are also proposed to contain a tungstobispterin site and one [4Fe-4S] cluster per subunit.

In the last decade, several species of anaerobic sulfur-dependent heterotrophic hyperthermophiles have been isolated from solfataric fields and submarine hydrothermal systems (5, 46). These organisms exhibit optimal growth at temperatures of 90°C or above, and most of them belong to the domain Archaea rather than Bacteria (50). With the exception of the methanogenic species, many of the hyperthermophiles are able to utilize peptides as their sole carbon source, although a few saccharolytic species are also known. One of the most extensively studied of these organisms is the archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus (optimum growth temperature, 100°C [14]). This anaerobic heterotroph grows on peptides (casein, peptone, yeast extract) and utilizes both simple (maltose, cellobiose) and complex (starch, glycogen) sugars. It metabolizes carbohydrates by an unusual fermentation-type pathway whose products are acetate, CO2, H2, and alanine (26, 27). Although the growth of many of the hyperthermophilic archaea is dependent upon elemental sulfur (S0), which is reduced to H2S, P. furiosus is one of the few archaea that can grow well in the absence of S0 (14, 44).

The growth of P. furiosus is dependent upon tungsten (8), an element rarely used in biological systems (24, 30). Two tungsten-containing, aldehyde-oxidizing enzymes, aldehyde ferredoxin oxidoreductase (AOR [36]) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate ferredoxin oxidoreductase (GAPOR [38]) have been previously purified from this organism. AOR has a broad substrate specificity but is most active with aldehydes derived from amino acids (via transamination and decarboxylation [21]). AOR is thought to play a key role in peptide fermentation by oxidizing aldehydes generated by the four types of 2-keto acid oxidoreductases present in this organism (1, 22, 35). In contrast, GAPOR uses only glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate as a substrate and it functions in the unusual glycolytic pathway that is present in P. furiosus, replacing the expected glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (38).

The hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus litoralis has been reported to contain another type of tungsten-containing, aldehyde-oxidizing enzyme, termed formaldehyde ferredoxin oxidoreductase (FOR [37]). This organism, like P. furiosus, ferments peptides and certain sugars and requires S0 for optimal growth (7, 39), although T. litoralis shows essentially no similarity (3%) with P. furiosus at the DNA level (39). FOR was reported to oxidize only small (C1 to C3) aliphatic aldehydes (37). However, dramatic losses of FOR activity occurred during purification from T. litoralis (>90% after two chromatography steps), leading to a virtually inactive enzyme (37). Herein we show that P. furiosus also contains FOR and report on its biochemical and molecular properties, including the gene-derived amino acid sequence. This enzyme also undergoes significant inactivation during purification, but the results presented herein indicate that this is due to the loss of sulfide. The substrate specificity of FOR (both purified and sulfide-activated FOR) has been evaluated, and although its function in vivo is still unclear, the enzyme shows a high catalytic efficiency with aliphatic dialdehydes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth of the organism and enzyme purification.

P. furiosus (DSM 3638) was grown in the absence of S0 at 90°C in a stainless steel fermentor with maltose as the carbon source as previously described (8). FOR was routinely purified from frozen cells (500 g [wet weight]) under strictly anaerobic conditions at 23°C. The buffer used throughout the purification was 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, containing 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). Where indicated (see Results), 10% glycerol (vol/vol) and/or 2 mM sodium dithionite were also present. The techniques and procedures were the same as those used to purify AOR from P. furiosus, up to the first chromatography step (36). In a typical purification, the cell extract prepared from up to 500 g (wet weight) of frozen cells was loaded onto a column (10 by 14 cm) of DEAE Fast Flow (Pharmacia LKB) equilibrated with buffer. FOR eluted from the column at 150 to 205 mM NaCl with a gradient (10 liters) from 0 to 0.5 M NaCl in buffer. The flow rate was 20 ml/min, and 125-ml fractions were collected. Fractions from this column with FOR activity were combined (1.2 liters) and loaded directly onto a column (5 by 25 cm) of hydroxyapatite (American International Chemical). The absorbed proteins were eluted with a gradient (4.0 liters) from 0 to 0.2 M potassium phosphate in buffer at a flow rate of 4.0 ml/min. Fractions of 100 ml were collected, and FOR activity eluted as 55 to 140 mM phosphate was applied. Fractions containing FOR activity were combined and concentrated to approximately 12 ml by ultrafiltration with an Amicon type PM-30 membrane. The concentrated sample of FOR was applied to a column (6 by 60 cm) of Superdex 200 (Pharmacia LKB) equilibrated with buffer containing KCl (200 mM). Fractions containing pure FOR as judged by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) gel electrophoresis were combined (150 ml), concentrated by ultrafiltration to approximately 5 ml, and stored as pellets under liquid N2.

Enzyme assays.

FOR activity was routinely determined at 80°C with formaldehyde (50 mM) as the substrate and benzyl viologen (3 mM) as the electron acceptor (37). Where indicated in Results, methyl viologen (3 mM) replaced benzyl viologen. The reduction of P. furiosus ferredoxin by FOR was measured as described previously (8). Crotonaldehyde (250 μM) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (300 μM) were used as substrates in the assays for AOR and GAPOR, respectively. Results are expressed as units per milligram of protein where 1 U equals the oxidation of 1 μmol of substrate/min/mg of protein. Hydroxycarboxylate-viologen oxidoreductase (HVOR) assays were carried out at 80°C in 100 mM EPPS [N-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-N′-(3-propanesulfonic acid)] (pH 8.4) with either 2-hydroxy acids as substrates and oxidized benzyl viologen (3 mM) as the electron acceptor or 2-keto acids as substrates and reduced benzyl viologen (1 mM) as the electron donor (45). For the latter assay, benzyl viologen was reduced with sodium dithionite. Amino acid oxidoreductase assays were carried out at both 50 and 80°C in 100 mM EPPS (pH 8.4) with various amino acids as substrates (0.1 to 5 mM) and benzyl viologen (3 mM) as the electron acceptor. Pyruvate formate lyase activity was determined by a two-step assay modified from that previously described (31). The assay mixture contained 100 mM EPPS (pH 8.4), sodium pyruvate (2 or 50 mM), coenzyme A (55 or 100 μM), and FOR (see below). This mixture was incubated anaerobically at 80°C for 10 min and then rapidly cooled to 4°C. Formate was then measured at 37°C with an NAD-dependent formate dehydrogenase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (F8649; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.). NAD (1 mM) and formate dehydrogenase (50 μg) were added to the cooled reaction mixture, and NADH production was measured by the increase in absorbance at 340 nm. A standard curve was prepared with 50 to 300 μM formate. For the HVOR, amino acid oxidoreductase, and pyruvate formate lyase assays, the final reaction mixture volumes were 2 ml and all assays contained either pure FOR (50 μg) or a cell extract of P. furiosus (50 μl of ∼15 mg/ml).

Other methods.

Iron (33), acid-labile sulfide (11), cysteine (2, 43), pterin (51), and protein (6, 34) were measured as described previously. Molecular weight estimations (32, 37), plasma emission spectroscopy (37), and N-terminal sequence analysis (13) were all carried out as described in the references. Ferredoxin (2), AOR (36), and GAPOR (38) were purified from P. furiosus as described previously. Amino acid sequences were analyzed with the Genetics Computer Group software program and MacVector (International Biotechnologies, Inc., New Haven, Conn.).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The DNA sequences of the genes encoding FOR and the two putative tungstoenzymes, WOR4 and WOR5, are available from GenBank under accession no. AF102769, AF101432, and AF101433, respectively. The DNA sequences for AOR and GAPOR (40) can be found in the EMBL data bank under the accession no. X79777 and U74298, respectively.

RESULTS

Purification of FOR.

The ability of FOR to catalyze the formaldehyde-dependent reduction of benzyl viologen was used to detect the enzyme during its purification from P. furiosus cells. Cell extracts contained 4.3 ± 1.8 U of formaldehyde-oxidizing activity per mg, which is much higher than that found in cell extracts of T. litoralis (0.6 ± 0.2 U/mg). However, AOR (but not GAPOR) of P. furiosus also uses formaldehyde as a substrate (36), so the apparent FOR activity observed in the extracts of P. furiosus is the sum of the formaldehyde-oxidizing activities of both FOR and AOR. The AOR and FOR activities were easily separated by the first chromatography step with DEAE-Sepharose. The FOR activity eluted at 150 mM NaCl, whereas the AOR activity eluted much later at 210 mM NaCl. FOR judged homogeneous by gel electrophoresis was obtained by two further chromatography steps (hydroxyapatite and gel filtration). It should be noted that substantial losses in activity were observed throughout the purification procedure. The highest recovery of activity (∼6%) was obtained when sodium dithionite (2 mM), DTT (2 mM), and glycerol (10%, vol/vol) were included in all buffers (see Table 1). This decreased to 2% if dithionite was omitted; hence, P. furiosus FOR undergoes substantial inactivation during purification, even under strictly anaerobic conditions. Possible reasons for this are discussed below.

TABLE 1.

Purification of FOR from P. furiosus

| Step | Protein (mg) | Activity (U) | Sp act (U/mg) | Recovery (%) | Purification (fold) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell extract | 14,000 | 35,600 | 2.5 | 100 | 1 |

| DEAE-Sepharose | 5,300 | 26,700 | 5.0 | 75 | 2 |

| Hydroxyapatite | 1,100 | 10,186 | 9.2 | 28 | 4 |

| Superdex 200 | 51 | 2,142 | 42.0 | 6 | 17 |

Approximately 50 mg of pure FOR was obtained from 500 g (wet weight) of P. furiosus cells (Table 1). This compares with yields of 120 and 35 mg for AOR and GAPOR, respectively, from the same cell mass. With benzyl viologen as the electron acceptor, the specific activity of pure FOR ranged from 35 to 45 U/mg. These values are in the same range as those reported for AOR (80 U/mg with crotonaldehyde as the substrate) and GAPOR (25 U/mg with glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate as the substrate) when it was assayed under standard conditions at 80°C. With methyl viologen rather than benzyl viologen as the acceptor, the activities of both FOR (24 U/mg) and AOR (8 U/mg) decreased while that of GAPOR (28 U/mg) was unaffected. Based on the total amount of activity in a cell extract and assuming an intracellular volume of 5 μl/mg (42), the intracellular concentrations of FOR, AOR, and GAPOR were estimated to be 46, 112, and 112 μM, respectively. These calculations are based on the holoenzyme forms (tetramer, dimer, and monomer, respectively [see below]) and take into account the formaldehyde oxidation activity of AOR in determining the FOR concentration.

Molecular properties.

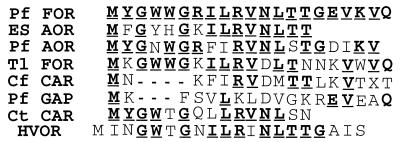

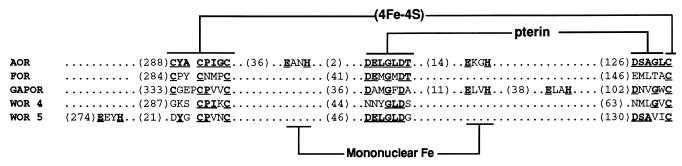

The apparent molecular weight of P. furiosus FOR as determined by gel filtration was 275,000 ± 20,000 (average ± standard deviation) (data not shown). After the enzyme was treated with SDS (1%, wt/vol) at 100°C for 10 min, the sample after SDS gel electrophoresis gave rise to two bands (Fig. 1) which corresponded to molecular weights of 265,000 ± 20,000 and 68,000 ± 4,000. A single protein band corresponding to a molecular weight of 68,000 ± 4,000 was observed if the sample was heated with SDS at 100°C for 30 min (Fig. 1). These results suggest that FOR is a homotetrameric protein (Mr, ∼272,000) with subunits with Mrs of ∼68,000. The latter value is similar to the subunit molecular weights reported for AOR (66,630 from the gene sequence [29]) and GAPOR (63,000 by gel filtration and electrophoresis [38]), although in contrast to FOR, AOR is a dimer (10) while GAPOR appears to be a monomer (38). The high purity of P. furiosus FOR and the presence of a single subunit were confirmed by N-terminal amino acid sequencing. This gave rise to a single sequence which showed similarity to the N-terminal sequences of AOR and GAPOR from P. furiosus (Fig. 2). The N-terminal sequence (29 residues) of FOR was used to search the genomic sequence database of P. furiosus, which is nearing completion by multiplex sequencing methods (12). The N terminus matched exactly the translated 5′ end of one open reading frame (ORF), now termed for, which contained 619 codons corresponding to a protein with a molecular weight of 68,724 (see below), which is in good agreement with that (68,000) estimated by biochemical analyses.

FIG. 1.

SDS gel electrophoresis analysis of purified P. furiosus FOR. Samples of FOR (8.5 mg/ml) were incubated with an equal volume of SDS (1%, wt/vol) at 100°C for 10 min (lane 3) or 30 min (lane 2) prior to electrophoresis on a 10% (wt/vol) acrylamide gel. Lane 1 contained marker proteins with the indicated molecular masses (in kilodaltons) for (from top to bottom) myosin, β-galactosidase, phosphorylase b, bovine serum albumin, ovalbumin, and carbonic anhydrase.

FIG. 2.

N-terminal amino acid sequence analysis of P. furiosus FOR and related enzymes. Abbreviations: Pf FOR, P. furiosus FOR (this work); ES AOR, ES-1 AOR (21); Pf AOR, P. furiosus AOR (36); Tl FOR, T. litoralis FOR (37); Cf CAR, Clostridium formicoaceticum carboxylic acid reductase (49); Pf GAP, P. furiosus GAPOR (38); Ct CAR, Clostridium thermoaceticum carboxylic acid reductase (α-subunit) (47); HVOR, P. vulgaris HVOR (48). Identical amino acids are in boldface type and underlined.

Colorimetric analyses indicated that P. furiosus FOR contained 3.8 ± 0.3 mol of Fe, 2.9 ± 0.5 g-mol of acid-labile sulfide, and six cysteines ± 1 cysteine per subunit. The last value agrees with that (six Cys/subunit) determined from the amino acid sequence (see below). An elemental analysis of FOR by inductively coupled plasma emission spectroscopy revealed the presence (in gram-atoms per subunit) of 3.8 ± 0.3 mol of Fe, 0.9 ± 0.1 mol of W, 1.5 ± 0.1 mol of Mg, 1.4 ± 0.1 mol of P, and 0.4 ± 0.1 mol of Ca. No other metals were present in significant amounts (>0.1 g-atom/subunit). The presence of a pterin cofactor in FOR was confirmed by extracting it in the presence of iodine and measuring the fluorescence of the resulting derivative. The spectrum (not shown) was virtually identical to that previously reported for the cofactor extracted from P. furiosus AOR (36), as well as to those obtained from various molybdenum-containing enzymes (except nitrogenase) when they are treated in a similar fashion. Such spectra originate from the so-called form A derivative of the pterin cofactor (41).

Catalytic properties.

FOR was purified by its abilities to oxidize formaldehyde and reduce the artificial electron carrier benzyl viologen. Under standard assay conditions (80°C, pH 8.4), the specific activity of pure FOR was dependent, for reasons as yet unknown, upon the enzyme concentration in the assay mixture, with the specific activity increasing fourfold as the enzyme concentration increased from 0.01 to 0.15 mg/ml. Hence, to enable meaningful comparisons, and unless otherwise stated, FOR was used at a protein concentration of 0.025 mg/ml in all assay mixtures. The activity of the pure enzyme with benzyl viologen as the electron acceptor increased more or less linearly with pH over the pH range 5.5 (1.5 U/mg) to 10.0 (55 U/mg) at 80°C (data not shown). Specific activity increased over the temperature range from 60°C (13 U/mg) to 90°C (58 U/mg) at pH 8.4 (data not shown). FOR activity, albeit low, was measurable at 25°C (∼1 U/mg, pH 8.4). The enzyme was quite thermostable, with a time required for a 50% loss of activity (t50%) at 80°C of about 8 h (with 5 mg of enzyme per ml in 100 mM EPPS, pH 8.4, containing 2 mM sodium dithionite and 2 mM DTT). For comparison, the values for AOR and GAPOR when they were treated under the same conditions were 15 min and 1 h, respectively. Note that activity values at 80°C (and above) were determined for all three enzymes from initial rates of benzyl viologen reduction, which were measured over a period of 30 s or less.

For FOR under standard assay conditions, a linear Lineweaver-Burk plot was obtained when the formaldehyde concentration was varied from 0.5 to 100 mM. The apparent Km and Vmax values were 25 mM and 62 U/mg, respectively. The former value suggests that formaldehyde is unlikely to be the physiological substrate. As shown in Table 2, FOR also oxidized various C1 to C3 aldehydes when they were used at either low (0.3 mM) or high (50 mM) concentrations. The exceptions were glyoxal, which inhibited the enzyme at concentrations above 1 mM (data not shown), and methyl glyoxal, which was not oxidized at a detectable rate. However, the apparent Km value, calculated from linear double-reciprocal plots, for both of the most active of the C1 to C3 aldehydes, acetaldehyde and propionaldehyde (Table 2), was 60 mM (Table 3), suggesting that these reactions also are not of physiological relevance. As shown in Table 2, FOR exhibited low activity with butyraldehyde (C4) or crotonaldehyde (C4) as a substrate but was not active with isovaleraldehyde (C5), indicating that the catalytic site of the enzyme is accessible only to short-chain (C1 to C3) aliphatic aldehydes. This notion was supported by a lack of detectable activity with the aromatic substrates benzaldehyde, salicaldehyde, and 2-furfuraldehyde. On the other hand, FOR did oxidize short-chain aldehydes with associated aromatic groups, such as phenylacetaldehyde, phenylpropionaldehyde, and indole-3-acetaldehyde (Tables 2 and 3). In fact, the kinetic constants determined for indoleacetaldehyde and phenylpropionaldehyde were comparable to those obtained with acetaldehyde (Table 3), although the relatively high apparent Km values (≥15 mM) again suggest that the oxidation of aromatic acetaldehyde derivatives is not the in vivo function of FOR.

TABLE 2.

Substrate specificity of P. furiosus FOR

| Substrate | Sp act (U/mg)a

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purified FOR at substrate concn (mM):

|

Sulfide-activated FOR at substrate concn (mM):

|

|||

| 0.3 | 50 | 0.3 | 50 | |

| Formaldehyde (C1) | 0.49 ± 0.24 | 35.50 ± 2.46 | 2.30 ± 0.09 | 85.00 ± 7.5 |

| Formamide (C1) | 1.06 ± 0.12 | 0.64 ± 0.24 | 0.44 ± 0.13 | 0.20 |

| Acetaldehydeb (C2) | 0.30 ± 0.06 | 8.03 ± 3.87 | 2.45 ± 0.08 | 23.22 ± 6.0 |

| Glyoxal (C2) | 2.20 ± 0.05 | NDc | 2.45 ± 0.08 | ND |

| Methyl glyoxal (C3) | 0.04 | ND | 0.23 | ND |

| Pyruvaldehyde (C3) | 0.47 ± 0.03 | 2.44 ± 0.44 | 1.92 ± 0.36 | 7.48 ± 0.57 |

| Glyceraldehyde (C3) | 0.20 ± 0.03 | 1.02 ± 0.05 | 0.55 ± 0.02 | 3.49 ± 0.15 |

| Propionaldehyde (C3) | 0.61 ± 0.20 | 5.16 ± 2.10 | 0.32 ± 0.15 | 14.40 ± 0.88 |

| Crotonaldehyde (C4) | 0.18 ± 0.06 | 0.59 ± 0.08 | 0.09 ± 0.04 | 0.36 ± 0.13 |

| Butyraldehyde (C4) | ND | 0.29 ± 0.13 | ND | 0.35 ± 0.08 |

| Isovaleraldehyde (C5) | ND | ND | ND | 0.33 ± 0.14 |

| Phenylacetaldehyde | ND | 0.72 ± 0.01 | ND | ND |

| Phenylpropionaldehyde | 0.31 ± 0.13 | 19.81 ± 4.87 | 0.62 ± 0.19 | 30.81 ± 7.33 |

Reactions were carried out at 80°C in 100 mM EPPS buffer (pH 8.4) with benzyl viologen (3 mM) as the electron carrier and with a substrate concentration of 0.3 or 50 mM.

Measured at 65°C.

ND, no activity was detected.

TABLE 3.

Kinetic constants for the purified and sulfide-activated forms of P. furiosus FORa

| Substrate (mM)b | Purified FOR

|

Sulfide-activated FOR

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apparent Km (mM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/Km (μM−1 s−1) | Apparent Km (mM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/Km (μM−1 s−1) | |

| Formaldehyde (0.5–80) | 25 | 7.1 × 104 | 3.00 | 15 | 1.3 × 105 | 8.46 |

| Acetaldehydec (1–250) | 60 | 4.4 × 104 | 0.73 | 8 | 2.8 × 104 | 3.50 |

| Propionaldehyde (1–200) | 62 | 1.1 × 104 | 0.17 | 25 | 2.3 × 104 | 0.92 |

| Phenylpropionaldehyde (0.9–80) | 15 | 2.5 × 104 | 1.70 | 10 | 2.2 × 104 | 2.22 |

| Indole-3-acetaldehyde (0.5–80) | 25 | 2.3 × 103 | 0.09 | 12 | 1.1 × 103 | 0.10 |

| Succinic semialdehyde (0.5–30) | 8 | 5.7 × 103 | 0.71 | 6 | 1.1 × 104 | 1.90 |

| Glutaric dialdehyde (0.01–30) | 0.8 | 4.2 × 104 | 60.0 | 1 | 5.7 × 104 | 57.0 |

Reactions were carried out at 80°C in 100 mM EPPS buffer (pH 8.4) with benzyl viologen (3 mM) as the electron acceptor.

Values in parentheses indicate the concentration range in millimolar units used to obtain the kinetic constants.

Measured at 65°C.

A clue to other potential substrates for P. furiosus FOR came from the fact that the N-terminal sequences of members of the AOR family of tungstoenzymes, which includes FOR (Fig. 2), were previously reported (30) to have similarity with that of the molybdoenzyme HVOR. HVOR, which has been purified from Proteus vulgaris (48) and Clostridium tyrobutyricum (3), has a broad substrate specificity and catalyzes the reversible oxidation of 2-hydroxycarboxylic acids with benzyl viologen as the electron carrier. However, P. furiosus FOR did not oxidize lactate, 2-hydroxybutyrate, 2-hydroxyvalerate, 2-hydroxycaproate, or 1-ethyl-2-hydroxycaproate and it did not reduce pyruvate, 2-ketobutyrate, 2-ketovalerate, 1-ethyl-3-ketovalerate, 1-ethyl-4-ketovalerate, or 2-ketocaproate (with these substrates being used at a 5 or 50 mM final concentration). In addition, FOR was unable to oxidize amino acids (glycine, alanine, serine, threonine, aspartate, glutamate, and sarcosine) or formate (to CO2) with benzyl viologen or NAD as the electron acceptor and it did not exhibit pyruvate formate lyase activity. Furthermore, none of these activities were detected in a cell extract of P. furiosus.

Thus, of all the compounds listed above, P. furiosus FOR oxidizes only short-chain (at most C4) unsubstituted aldehydes, but even these are poor substrates, as shown by the high apparent Km values. Our attempts to uncover related substrates for which the enzyme had a much greater affinity were limited by the availability of substituted compounds of this type. Nevertheless, FOR did catalyze the oxidation of succinate semialdehyde (C4) at a reasonable rate and the apparent Km value was almost an order of magnitude lower than that of propionaldehyde (Table 3). Moreover, while butyraldehyde (C4) was oxidized by FOR only at extremely high concentrations (Table 2), the presence of a terminal aldehyde group, as in glutaric dialdehyde (C5), resulted in a substrate that was oxidized at a rate comparable to that obtained with formaldehyde and acetaldehyde but with an apparent Km value more than 25-fold lower (25 versus 0.8 mM) (Table 3). Increasing the chain length to C6 (adipic acid semialdehyde, methyl ester) resulted in an activity similar to that obtained with succinic semialdehyde (catalytic constant [kcat] = 3.0 × 104 s−1) but with a much higher Km value (30 mM). From these analyses we conclude that the true substrate for FOR is therefore most likely a C5 di- or semialdehyde, although its precise nature is still unclear.

The activity of FOR was largely unaffected when it was assayed in the presence of various mono- and diacids (formate, acetate, succinate, citrate) when they were used at concentrations of 10 mM. The exception was glutarate, which resulted in ∼15% inhibition under standard assay conditions. At a higher concentration of the acids (100 mM), the enzyme was inhibited by 35, 32, 36, 75, and 70% in the presence of formate, acetate, succinate, glutarate, and citrate, respectively. These data again suggest that C5- or C6-type aldehydes might be physiologically relevant. With either formaldehyde (50 mM) or glutaric dialdehyde (30 mM) as the substrate for FOR, linear double-reciprocal plots were obtained with P. furiosus ferredoxin in place of benzyl viologen as the electron acceptor (concentration range, 10 to 200 μM). The apparent Km value for the ferredoxin was approximately 100 μM (at pH 8.0) with both substrates. Over the pH range 6.0 to 10.0, the highest rate of ferredoxin reduction (coupled to formaldehyde oxidation) was observed at pH 6.0. The rate decreased with increasing pH and at pH 10.0 was about 30% of that observed at pH 6.0 (data not shown). Thus, although the in vivo aldehyde substrates for AOR and GAPOR are known, that for FOR remains unknown but, like AOR and GAPOR, FOR utilizes ferredoxin as its physiological electron carrier.

FOR was routinely purified in the presence of glycerol (10%, vol/vol) as this appeared to stabilize the enzyme. That is, when FOR was purified in the absence of this reagent, the final recovery of FOR activity decreased by about twofold, as did the specific activity of the pure enzyme. However, although glycerol is a potential substrate analog, it had little effect on FOR activity. For example, when glycerol-free FOR was incubated (at 23°C in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.0) for up to 6 h with up to 40% (vol/vol) glycerol, there was no significant loss of activity (determined in the absence of glycerol). The enzyme was inhibited when 60% (vol/vol) glycerol was used, as about 60% of the activity was lost after 6 h. Under the same conditions, P. furiosus AOR was much more sensitive to inhibition by glycerol, with a loss of 25 and 80% of the initial activity after a 4-h incubation with 20 and 40% (vol/vol) glycerol, respectively. P. furiosus GAPOR was even more sensitive to inhibition by glycerol, with t50%s of 30 and 10 min in the presence of 40 and 60% glycerol, respectively. Hence, although all three enzymes are routinely purified in the presence of glycerol (10%, vol/vol), significantly higher concentrations are required for inhibition.

P. furiosus FOR as purified under standard conditions was oxygen sensitive, with the t50% being about 12 h when FOR was exposed to air (no activity was lost under anaerobic conditions). For comparison, a similar value was obtained with P. furiosus GAPOR, whereas AOR from P. furiosus was much more sensitive to oxygen, with the t50% being about 30 min in air. P. furiosus FOR was not inhibited when it was incubated for up to 24 h with iodoacetate, arsenite, or cyanide (each at a concentration of 5 mM) prior to being assayed under standard conditions in the absence of these reagents. In contrast, both AOR and GAPOR of P. furiosus were inhibited by all of these reagents under the conditions used for FOR. Thus, when AOR was incubated with either potassium cyanide, sodium arsenite, or sodium iodoacetate (each at 5 mM), the t50% was 13 h, 10 min, or 5 min, respectively. With GAPOR under the same conditions, the t50% was 30 min, 12 h, or 20 min, respectively. Thus, while GAPOR is very sensitive to inhibition by cyanide and AOR is readily inhibited by arsenite and iodoacetate, FOR is not affected by these reagents.

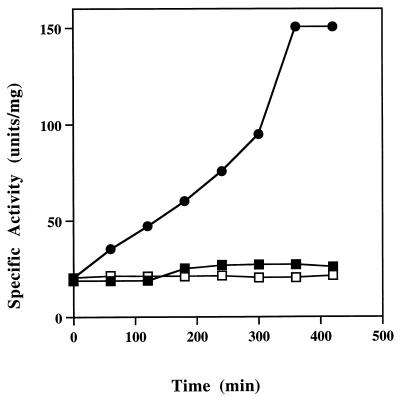

Properties of sulfide-activated FOR.

A troubling aspect concerning the characterization of P. furiosus FOR was the significant loss of activity during purification. This loss occurred even when the procedure was carried out under the most rigorous of anaerobic conditions with reducing agents (DTT and sodium dithionite) in all buffers. A clue to the mechanism involved was the finding that the enzyme can be activated by sulfide. As shown in Fig. 3, incubation of FOR with excess sodium sulfide (20 mM) and sodium dithionite (20 mM) at 23°C (pH 8.0) resulted after a 6-h period in a >5-fold increase in specific activity. No activation was observed even after 8 h if either reagent was omitted. The degree of activation varied from preparation to preparation, but all samples analyzed showed at least a threefold increase in formaldehyde oxidation activity after a 6-h period and thereafter showed little if any further increase, even after 24 h. The time course and degree of activation were similar when sodium dithionite was replaced by titanium(III) citrate (20 mM), but DTT (20 mM) was ineffective as the reductant in the activation reaction. When the enzyme was incubated with sulfide for 6 h and the sulfide was then removed (by gel filtration with 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0] containing 2 mM sodium dithionite, 2 mM DTT, and 10% [vol/vol] glycerol), the specific activity of the resulting sulfide-free form of the activated enzyme decreased by ∼20% but this specific activity remained unchanged even after a further 24 h under anaerobic conditions (in the absence of sulfide). The sulfide-free, activated form of FOR was much more sensitive to inactivation by oxygen than the purified form, with a decrease in the t50% from 12 to about 4 h. Similarly, in contrast to the purified form, sulfide-activated FOR was sensitive to inhibition by cyanide. For example, while untreated FOR was unaffected by a 4-day incubation with cyanide (5 mM), the activated form (10 mg/ml in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0) lost approximately 70% of its activity after a 16-h incubation under the same conditions.

FIG. 3.

Activation of P. furiosus FOR by sulfide. The enzyme (10 mg/ml in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0) was incubated at 23°C with either sodium sulfide (20 mM, open squares), sodium dithionite (20 mM, filled squares), or both (filled circles). At the indicated times, samples were removed and the residual activities were determined with formaldehyde as the substrate under standard assay conditions.

Thus, treating FOR with sulfide results in an enzyme that is more active in catalyzing formaldehyde oxidation and that is more sensitive to inactivation by both cyanide and oxygen. It seems reasonable to suggest that the larger-than-expected decrease in activity of FOR during purification was due, in substantial part, to loss of sulfide. While the mechanisms of the sulfide-dependent effects are under study, of more relevance to the present work was the possibility that the substrate specificity of the sulfide-activated form of FOR was different from that of the purified or native form of the enzyme. Kinetic analyses were therefore conducted with three different batches of each of the purified and sulfide-activated forms, and the results are shown in Tables 2 and 3 (values are averages of at least six determinations). As indicated, although the range of substrates used by the two forms of the enzyme was the same, there were significant changes in the kinetic properties of the activated enzyme. Thus, while some of the substrates, like formaldehyde, were oxidized at a higher rate by the sulfide-activated form of the enzyme, some were oxidized at the same rate (glyoxal) or at a lower rate (formamide, propionaldehyde, and crotonaldehyde) and phenylacetaldehyde was seemingly not oxidized at all by the sulfide-activated form. Similarly, as shown in Table 3, while the catalytic efficiencies of the sulfide-activated enzyme, as determined by the kcat/Km values, were generally higher than those exhibited with the prepared enzyme, this result was due mainly to the lower Km values. The activated enzyme had higher kcat values with only four of the seven substrates tested, and these ranged between 136 and 209% of the values obtained with the same substrate and the enzyme as prepared (Table 3). Hence, while the sulfide-activated enzyme does show a large increase (approximately fivefold) in activity with formaldehyde as the substrate under standard assay conditions, relative to the activity of the purified enzyme, this is obviously not the situation with all of the substrates that this enzyme can utilize. At this point it is not clear why the degree of activation depends on the substrate that is utilized. Notably, similar kinetic values were determined for the two enzyme forms with the best substrate found so far, glutaric dialdehyde (Table 3).

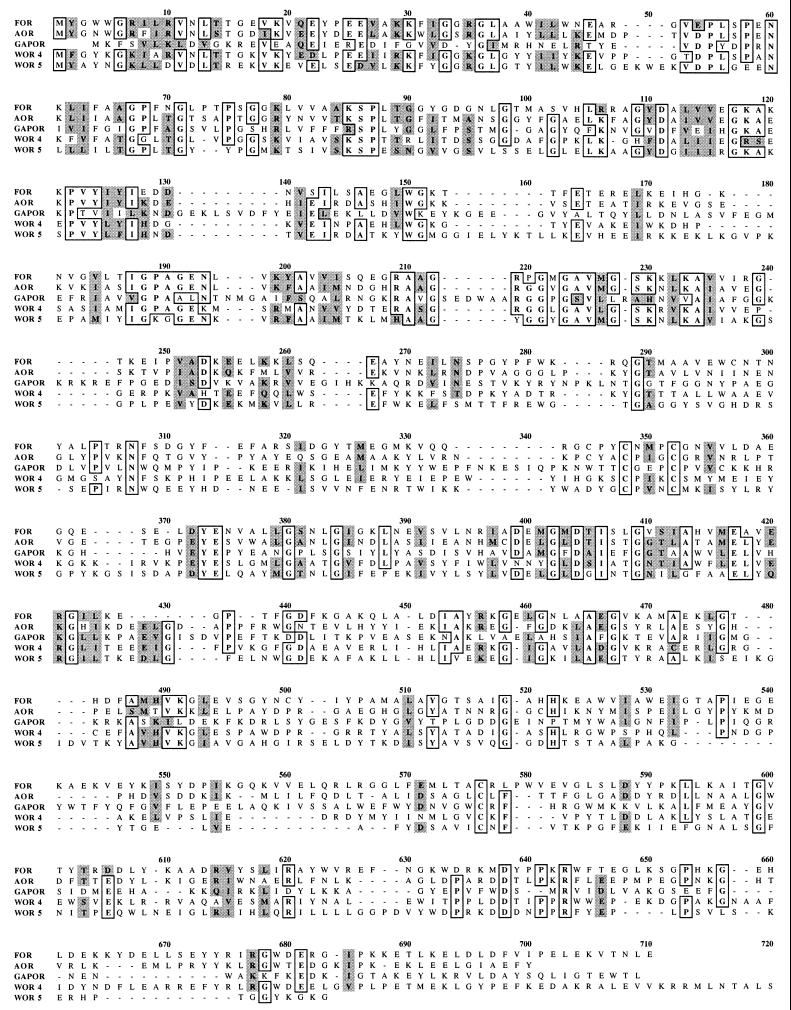

Gene sequences of related enzymes.

With the availability of the complete amino acid sequence of FOR, the genomic sequence database of P. furiosus (12), while still incomplete, was also searched for related enzymes. The N-terminal sequence (45 residues) of P. furiosus GAPOR (38) matched exactly the translated 5′ end of one ORF, now termed gor. The gene contained 653 codons corresponding to a protein with a molecular weight of 73,850. This value is in reasonable agreement with that (63,000) estimated by biochemical analyses (38). The gene encoding AOR (aor) was located in the database with the previously published sequence (29), and the two nucleotide sequences were identical. The genes encoding FOR (for), aor, and gor were spatially separated on the genome, and except for the ORFs adjacent to the previously identified cofactor-modifying (cmo) gene (29), none of the ORFs immediately adjacent to the for, aor, and gor genes appeared to have a role in the synthesis or function of these three tungstoenzymes in P. furiosus. The complete sequences of the three enzymes are aligned in Fig. 4. FOR and AOR are highly similar (61% similarity, 40% identity), with GAPOR being somewhat less closely related (50% similarity and 23% identity with FOR and 45% similarity and 25% identity with AOR).

FIG. 4.

Alignment of the sequences of FOR, AOR, and GAPOR and the putative gene products WOR4 and WOR5 from P. furiosus. Identical residues are boxed, and similar residues are shaded.

A search of the genome database with the complete amino acid sequences of FOR, AOR, and GAPOR revealed the presence of two additional ORFs, and these appear to encode the fourth and fifth members of this enzyme family. Tentatively termed wor4 and wor5 (to indicate genes encoding putative oxidoreductases within the tungstoenzyme family), these genes are also spatially separated from those encoding the other three tungstoenzymes, and adjacent genes appear to be unrelated (although obviously the functions of these putative enzymes are as yet unknown). The wor4 and wor5 genes encode 622 and 582 codons, corresponding to proteins with molecular weights of 69,363 and 64,889, respectively, and their sequences are also aligned in Fig. 4. The similarities (identities shown in parentheses) of the sequence of the WOR4 protein to those of FOR, AOR, and GAPOR are 57% (36%), 58% (37%), and 49% (25%), respectively, and those of the WOR5 protein are 56% (33%), 58% (36%), and 49% (25%), respectively. Hence, both WOR4 and WOR5 appear to be more closely related to AOR and FOR than they are to GAPOR.

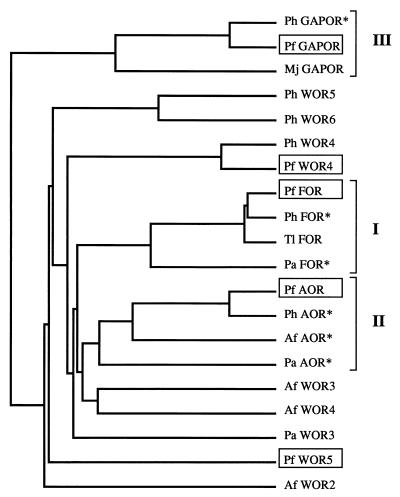

The complete genomes of several hyperthermophilic archaea are now, or soon will be, available, and these were searched for relatives of FOR and other members of the tungstoenzyme family found in P. furiosus. These genomes include those of Pyrococcus horikoshii (19, 25), Pyrobaculum aerophilum (15, 16), Methanococcus jannaschii (9), and Archaeoglobus fulgidus (28), all of which contained genes encoding putative tungstoenzymes. The phylogenetic relationship between the amino acid sequences of the five tungstoenzymes proposed for P. furiosus and their homologs in the other genome sequences of various archaea is depicted in Fig. 5. From the dendogram three distinct groups are apparent, and these correspond to the three types of enzymes that have been purified and characterized so far. Group I, or the FOR group, has homologous genes in P. horikoshii and Pyrobaculum aerophilum as well as in P. furiosus and T. litoralis (previously characterized). Group II enzymes have representatives in P. horikoshii, A. fulgidus, and Pyrobaculum aerophilum as well as in P. furiosus, while the group III enzyme, GAPOR, although it has so far been purified only from P. furiosus, has close homologs in P. horikoshii and M. jannaschii. It should be noted that these sequences have been placed in their respective groups based solely on similarity at the amino acid level, but the corresponding enzymes are predicted to have the same function as those of the previously characterized enzymes. As indicated in Fig. 5, there are also several sequences that do not fall into any of the three groups, including WOR4 and WOR5 of P. furiosus, and any existing relationship among them will have to await elucidation of function through biochemical or genetic analyses.

FIG. 5.

Phylogenetic relation of the amino acid sequences of tungstoenzymes from P. furiosus and their homologs found in genome databases. Sequences demarcated by brackets and Roman numerals indicate groups. Asterisks denote amino acid sequence homologous to a tungstoenzyme of known function, though the relevant enzyme activity has not yet been determined in these organisms. Length of the line represents distance in arbitrary units. Abbreviations: Ph, P. horikoshii; Pf, P. furiosus; Mj, M. jannaschii; Pa, Pyrobaculum aerophilum; Af, A. fulgidus. The GenBank accession numbers of amino acid sequences used in this figure are as follows: Ph GAPOR*, g3130733; Mj GAPOR, U67559; Ph WOR5, g3131172; Ph WOR6, g3131173; Ph WOR4, g3130250; Ph FOR*, g3257694; Ph AOR*, g3131315; Af AOR*, g2648240; Af WOR3, g2650295; Af WOR4, g2650628; and Af WOR2, g2650571. See the text for accession numbers of the P. furiosus sequences. For Pa FOR*, Pa AOR*, and Pa WOR3 accession numbers, see reference 16.

DISCUSSION

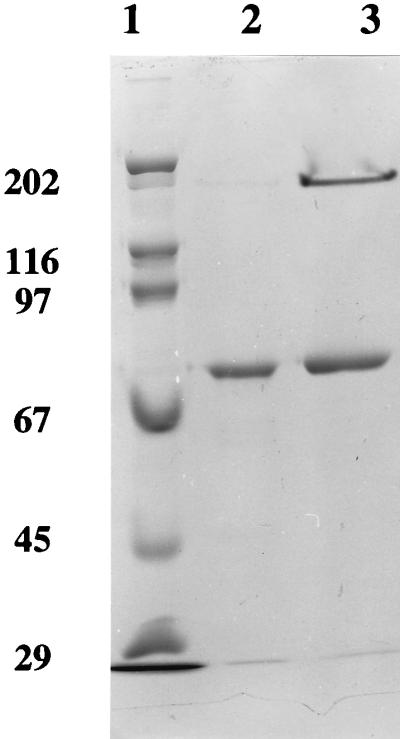

FOR is the third tungsten-containing, aldehyde-oxidizing enzyme, in addition to AOR and GAPOR, to be characterized from P. furiosus. Their cellular concentrations appear to be comparable, at least in cells grown with maltose as the primary carbon source. The Fe, W, P, and Mg content of FOR is similar to that of AOR (10, 36) and also GAPOR, but FOR also contains Ca (apparently one atom/subunit) while GAPOR also contains Zn (two atoms/subunit) (38). The function of Ca in FOR (and of Zn in GAPOR) is not known. From crystallographic analysis, AOR is known to contain one [4Fe-4S] cluster and a mononuclear tungstobispterin cofactor (10). As shown in Fig. 6, the two pterin-binding motifs and all four of the Cys residues in AOR are conserved in FOR and also in GAPOR, indicating that they too contain one [4Fe-4S] cluster and a mononuclear tungstobispterin cofactor. AOR also contains two EXXH motifs, which coordinate a mononuclear metal site, most likely iron, that bridges the two subunits. FOR lacks these motifs (as does GAPOR, which is monomeric) and presumably lacks subunit-bridging metal ions, a conclusion supported by its metal content (Fig. 6). The sequence of the FOR of T. litoralis is also available (29), and in spite of the low similarity in the overall DNA sequences of P. furiosus and T. litoralis, it is virtually identical to the P. furiosus enzyme, with 92% similarity (87% identity) to its amino acid sequence. The two putative tungstoenzymes in P. furiosus, WOR4 and WOR5, have molecular weights comparable to those of FOR, AOR, and GAPOR, and in its sequence, each contains a motif, separated by the appropriate number of residues, that binds a single [4Fe-4S] cluster and a bispterin site (Fig. 6). These enzymes also contain EXXH motifs but they are not in the same location as those of AOR, suggesting that WOR4 and WOR5 lack the subunit-bridging metal ion found in AOR. In any event, these two putative tungstoenzymes are clearly closely related both in cofactor content and in structure to the three tungstoenzymes that have been purified from P. furiosus, although their functions are obviously unknown.

FIG. 6.

Alignments of the cofactor-binding motifs of FOR, AOR, and GAPOR and of the putative gene products WOR4 and WOR5 from P. furiosus. The numbers in parentheses indicate the numbers of residues between the indicated motifs. See the text for details.

Homologs of the three characterized tungstoenzymes and of the two putative tungstoenzymes of P. furiosus were identified in the genomes of other hyperthermophilic archaea. P. horikoshii has representative sequences of tungstoenzymes in all three main groups, namely, FOR, AOR, and GAPOR, as well as homologs of the putative P. furiosus WOR4 and WOR5 enzymes. This finding is consistent with the physiological similarities between the two organisms (8, 19). In fact, P. horikoshii has a sixth member of the tungstoenzyme family, close homologs of which two (WOR5 and WOR6) have not yet been identified in the still incomplete genome of P. furiosus. It remains to be seen if P. furiosus contains more than five tungstoenzymes. Similarly, the presence of homologs of FOR and AOR, both of which have proposed roles in peptide metabolism, in Pyrobaculum aerophilum and A. fulgidus is consistent with the reported ability of both organisms to use peptides as a carbon source, even though their modes of energy conservation are quite different (by respiring nitrate or oxygen and by sulfate reduction, respectively). On the other hand, the finding of a GAPOR-type sequence in M. jannaschii is unexpected. This methanogenic organism is thought to grow only on H2-CO2, and yet GAPOR is a key enzyme in the glycolytic pathway of heterotrophic hyperthermophiles. Either GAPOR has another function in methanogens or else M. jannaschii can grow on other carbon substrates, perhaps derived from storage compounds.

The true role of FOR in P. furiosus also remains a mystery, in spite of the extensive analyses of potential physiological substrates reported herein. Compared to formaldehyde, FOR (in both the purified and sulfide-activated states [see below]) exhibited a higher kcat/Km value only with glutaric dialdehyde, a C5 compound, but this compound does not lie on a known biochemical pathway. Various C4 to C6 semialdehydes are involved in the metabolism of certain amino acids such as Arg, Lys, and Pro (4, 20, 52), and although such compounds are not commercially available, whether relevant enzymes are present in cell extracts of P. furiosus is under study. Indeed, it should be noted that P. furiosus appears to utilize AOR and GAPOR for very different purposes, namely, in peptide catabolism and glycolysis, respectively, yet these two enzymes have very similar molecular properties and presumably are also closely related phylogenetically. Thus, it is hard to rationalize a potential physiological role for FOR based merely on its similarity to AOR and GAPOR. Similarly, while an aldehyde-oxidizing enzyme with a substrate specificity analogous to that of AOR has been found in mesophilic clostridia (47, 49), an enzyme with the substrate range of FOR has not been reported for any organism. A similar situation will no doubt exist for the putative tungstoenzymes WOR4 and WOR5, and elucidating their functions, particularly in the absence of purified enzymes, will likely require a genetic approach.

Last, we turn to the finding that FOR is activated by incubation with sulfide under reducing conditions. Although loss of sulfide can account for the significant loss of formaldehyde oxidation activity observed during the purification of FOR, it raises several issues, such as what is the nature of the sulfide that is lost, why is the extent of sulfide activation substrate dependent, and is sulfide activation a physiologically relevant reaction? While there is no experimental evidence to address the last question, the sulfide that is lost is presumably associated with the catalytic site, and that site in the activated and prepared forms of the enzyme presumably has different reactivities with different substrates. By analogy with AOR (10), FOR is expected to contain a tungstobispterin site where the W atom is coordinated in part by four S atoms from the dithiolene groups of two pterin molecules, with water, hydroxide, and/or a terminal oxo group completing the coordination sphere. Interestingly, mononuclear molybdopterin-containing enzymes such as xanthine oxidase lose sulfur as thiocyanate when the oxidized forms are treated with cyanide (see, for example, reference 23). The resulting “desulfo” enzymes are activated by treatment with sulfide, which is accomplished by conversion of a terminal Mo⩵O species to Mo⩵S, which does not involve the dithiolene sulfurs. So, is FOR as purified equivalent to the desulfo state, and does sulfide activation involve W⩵O-to- W⩵S conversion? It is noteworthy that upon sulfide activation, FOR became more sensitive to inactivation by O2 and by cyanide, suggesting that both may effect a W⩵S-to-W⩵O conversion. However, for AOR, there was no evidence for a W=S bond either from crystallography (10) or X-ray absorption spectroscopy (18). Thus, the precise mechanism by which sulfide activates FOR remains to be determined, and spectroscopic analyses using both X-ray absorption and resonance Raman (see reference 17) of the enzyme are in progress to address these issues.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by grants from the Department of Energy (FG05-95ER20175) and the National Science Foundation (BCS-9632657).

We thank A. Menon for helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams M W W, Kletzin A. Oxidoreductase-type enzymes and redox proteins involved in the fermentative metabolisms of hyperthermophilic archaea. Adv Protein Chem. 1996;48:101–180. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60362-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aono S, Bryant F O, Adams M W W. A novel and remarkably thermostable ferredoxin from the hyperthermophilic archaebacterium Pyrococcus furiosus. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:3433–3439. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.6.3433-3439.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bayer M, Gunther H, Simon H. Purification and characterization of a (S)-3-hydroxycarboxylate oxidoreductase from Clostridium tyrobutyricum. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1994;42:40–45. doi: 10.1007/BF00170222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bender D A. Amino acid metabolism. 2nd ed. 1985. pp. 152–154. and 181–186. John Wiley, New York, N.Y. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blöchl E, Burggraf S, Fiala F, Lauerer G, Huber G, Huber R, Rachel R, Segerer A, Stetter K O, Völkl P. Isolation, taxonomy, and phylogeny of hyperthermophilic microorganisms. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 1995;11:9–16. doi: 10.1007/BF00339133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1975;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown S H, Kelly R M. Characterization of amylolytic enzymes, having both α-1,4 and α-1,6-hydrolytic activity, from the thermophilic archaea Pyrococcus furiosus and Thermococcus litoralis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2614–2621. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.8.2614-2621.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bryant F O, Adams M W W. Characterization of hydrogenase from the hyperthermophilic archaebacterium, Pyrococcus furiosus. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:5070–5079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bult C J, White O, Olsen G J, Zhou L, Fleischmann R D, Sutton G G, Blake J A, Fitzgerald L M, Clayton R A, Gocayne J D, Kerlavage A R, Dougherty B A, Tomb J F, Adams M D, Reich C I, Overbeek R, Kirkness E F, Weinstock K G, Merrick J M, Glodek A, Scott J L, Geoghagen N S M, Weidman J F, Fuhrmann J L, Nguyen D, Utterback T R, Kelley J M, Peterson J D, Sadow P W, Hanna M C, Cotton M D, Roberts K M, Hurst M A, Kaine B P, Borodovsky M, Klenk H P, Fraser C M, Smith H O, Woese C R, Venter J C. Complete genome sequence of the methanogenic archaeon, Methanococcus jannaschii. Science. 1996;273:1058–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5278.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan M K, Mukund S, Kletzin A, Adams M W W, Rees D C. The 2.3 Å resolution structure of the tungstoprotein aldehyde ferredoxin oxidoreductase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. Science. 1995;267:1463–1469. doi: 10.1126/science.7878465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen J S, Mortenson L E. Inhibition of methylene blue formation during determination of acid-labile sulfide of iron-sulfur protein samples containing dithionite. Anal Biochem. 1977;79:157–165. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(77)90390-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cherry J L, Young H H, Disera L J, Ferguson F M, Kimball A W, Dunn D M, Gesteland R F, Weiss R B. Enzyme-linked fluorescent detection for automated multiplex DNA-sequencing. Genomics. 1994;20:68–74. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deutscher M P. Guide to protein purification. Methods Enzymol. 1990;182:588–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fiala G, Stetter K O. Pyrococcus furiosus sp. nov. represents a novel genus of marine heterotrophic archaebacteria growing optimally at 100°C. Arch Microbiol. 1986;145:56–61. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fitz-Gibbon S, Choi A J, Miller J H, Stetter K O, Simon M I, Swanson R, Kim U-J. A fosmid-based genomic map and identification of 474 genes of the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrobaculum aerophilum. Extremophiles. 1997;1:36–51. doi: 10.1007/s007920050013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fitz-Gibbon, S. Personal communication.

- 17.Garton S D, Garrett R M, Rajagopalan K V, Johnson M K. Resonance Raman characterization of the molybdenum center in sulfite oxidase: identification of Mo⩵O stretching modes. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:2590–2591. [Google Scholar]

- 18.George G, Prince R C, Mukund S, Adams M W W. Aldehyde ferredoxin oxidoreductase from the hyperthermophilic archaebacterium Pyrococcus furiosus contains a tungsten oxo-thiolate center. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:3521–3523. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gonzalez J M, Masuchi Y, Robb F T, Ammerman J W, Maeder D L, Yanagibayashi M, Tamaoka J, Kato C. Pyrococcus horikoshii sp. nov., a hyperthermophilic archaeon isolated from a hydrothermal vent at the Okinawa Trough. Extremophiles. 1998;2:123–130. doi: 10.1007/s007920050051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gottschalk G, editor. Bacterial metabolism. New York, N.Y: Springer Verlag; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heider J, Ma K, Adams M W W. Purification, characterization and metabolic function of aldehyde ferredoxin oxidoreductase from the hyperthermophilic and proteolytic archaeon Thermococcus strain ES-1. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4757–4764. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.16.4757-4764.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heider J, Mai X, Adams M W W. Characterization of 2-ketoisovalerate ferredoxin oxidoreductase, a new and reversible coenzyme A-dependent enzyme involved in peptide fermentation by hyperthermophilic archaea. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:780–787. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.3.780-787.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hille R. The mononuclear molybdenum enzymes. Chem Rev. 1996;96:2757–2816. doi: 10.1021/cr950061t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson M K, Rees D C, Adams M W W. Tungstoenzymes. Chem Rev. 1996;96:2817–2839. doi: 10.1021/cr950063d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kawarabayasi Y, Sawada M, Horikawa H, Haikawa Y, Hino Y, Yamamoto S, Sekine M, Baba S, Kosugi H, Hosoyama A, Nagai Y, Sakai M, Ogura K, Otsuka R, Nakazawa H, Takamiya M, Ohfuku Y, Funahashi T, Tanaka T, Kudoh Y, Yamazaki J, Kushida N, Oguchi A, Aoki K, Yoshizawa T, Nakamura Y, Robb F T, Horikoshi K, Masuchi Y, Shizuya H, Kikuchi H. Complete sequence and gene organization of the genome of a hyperthermophilic archaebacterium, Pyrococcus horikoshii OT3. 1998. www.bio.nite.go.jp/ot3db_index.html. www.bio.nite.go.jp/ot3db_index.html. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kengen S W M, Stams A J M. Formation of l-alanine as a reduced end product in carbohydrate fermentation by the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. Arch Microbiol. 1994;161:168–175. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kengen S W M, de Bok F A M, Vanloo N D, Dijkema C, Stams A J M, de Vos W M. Evidence for operation of Embden-Meyerhof pathway that involves ADP-dependent kinases during sugar fermentation by Pyrococcus furiosus. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:17537–17541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klenk H P, Clayton R A, Tomb J F, White O, Nelson K E, Ketchum K A, Dodson R J, Gwinn M, Hickey E K, Peterson J D, Richardson D L, Kerlavage A R, Graham D E, Krypides N C, Fleischmann R D, Quackenbush J, Lee N H, Sutton G G, Gill S, Kirkness E F, Dougherty B A, Mckenney K, Adams M D, Loftus B, Peterson S, Reich C I, McNeil L K, Badger J H, Glodek A, Zhou L, Overbeek R, Gocayne J D, Weidman J F, McDonald L, Utterback T, Cotton M D, Spriggs T, Artiach P, Kaine B P, Sykes S M, Sadow P W, D’Andrea K P, Bowman C, Fujii C, Garland S A, Mason T M, Olsen G J, Fraser C M, Smith H O, Woese C R, Venter J C. The complete genome sequence of the hyperthermophilic, sulfate-reducing archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus. Nature. 1997;390:364–370. doi: 10.1038/37052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kletzin A, Mukund S, Kelley-Crouse T L, Chan M K, Rees D C, Adams M W W. Molecular characterization of the genes encoding two tungsten-containing enzymes from hyperthermophilic archaea: aldehyde ferredoxin oxidoreductase from Pyrococcus furiosus and formaldehyde ferredoxin oxidoreductase from Thermococcus litoralis. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4817–4819. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.16.4817-4819.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kletzin A, Adams M W W. Tungsten in biology. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1996;18:5–64. doi: 10.1016/0168-6445(95)00025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knappe J, Blaschowski H P, Grobner P, Schmitt T. Pyruvate formate-lyase of Escherichia coli: the acetyl-enzyme intermediate. J Biochem. 1974;50:256–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1974.tb03894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lovenberg W, Buchanan B B, Rabinowitz J C. Studies on chemical nature of ferredoxin. J Biol Chem. 1963;238:3899–3913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lowry O H, Rosebrough N J, Farr A L, Randall R J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mai X, Adams M W W. Characterization of a fourth type of 2-keto acid-oxidizing enzyme from hyperthermophilic archaea: 2-ketoglutarate ferredoxin oxidoreductase from Thermococcus litoralis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5890–5896. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.20.5890-5896.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mukund S, Adams M W W. The novel tungsten-iron-sulfur protein of the hyperthermophilic archaebacterium, Pyrococcus furiosus, is an aldehyde ferredoxin oxidoreductase: evidence for its participation in a unique glycolytic pathway. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:14208–14216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mukund S, Adams M W W. Characterization of a novel tungsten-containing formaldehyde ferredoxin oxidoreductase from the extremely thermophilic archaeon, Thermococcus litoralis. A role for tungsten in peptide catabolism. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:13592–13600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mukund S, Adams M W W. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate ferredoxin oxidoreductase, a novel tungsten-containing enzyme with a potential glycolytic role in the hyperthermophilic archaeon, Pyrococcus furiosus. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:8389–8392. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.15.8389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neuner A, Jannasch H W, Belkin S, Stetter K O. Thermococcus litoralis sp. nov.: a new species of extremely thermophilic, marine archaebacterium. Arch Microbiol. 1990;153:205–207. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oost J, Schut G, Kengen S W M, Hagen W R, Thomm M, de Vos W M. The ferredoxin-dependent conversion of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus represents a novel site of glycolytic regulation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:28149–28154. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.28149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rajagopalan K V, Johnson J L. The pterin molybdenum cofactors. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:10199–10202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramakrishnan V, Verhagen M F J M, Adams M W W. Characterization of di-myo-inositol-1,1′-phosphate in the hyperthermophilic bacterium Thermotoga maritima. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:347–350. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.1.347-350.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Riddles P W, Blakeley R L, Zerner B. Reassessment of Ellman’s reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1983;91:49–60. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(83)91010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schicho R N, Ma K, Adams M W W, Kelly R M. Bioenergetics of sulfur reduction in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1823–1830. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.6.1823-1830.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schinschel C, Simon H. Effect of carbon sources and electron acceptors in the growth medium of Proteus spp. on the formation of (R)-2-hydroxycarboxylate viologen oxidoreductase and dimethylsulphoxide reductase. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1993;38:531–536. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stetter K O. Hyperthermophilic procaryotes. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1996;18:149–158. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strobl G, Feicht R, White H, Lottspeich F, Simon H. The tungsten-containing aldehyde oxidoreductase from Clostridium thermoaceticum and its complex with viologen-accepting NADPH oxidoreductase. Biol Chem Hoppe-Seyler. 1992;373:123–132. doi: 10.1515/bchm3.1992.373.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Trautwein T, Krauss F, Lottspeich F, Simon H. The (2R)-hydroxycarboxylate-viologen-oxidoreductase from Proteus vulgaris is a molybdenum-containing iron-sulphur protein. Eur J Biochem. 1994;222:1025–1032. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.White H, Feicht R, Huber C, Lottspeich F, Simon H. Purification and some properties of the tungsten-containing carboxylic acid reductase from Clostridium formicoaceticum. Biol Chem Hoppe-Seyler. 1991;372:999–1005. doi: 10.1515/bchm3.1991.372.2.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woese C R, Kandler O, Wheelis M L. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains of archaea, bacteria and eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4576–4579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamamoto I, Saiki T, Liu S-I, Ljungdahl L G. Purification and properties of NADP-dependent formate dehydrogenase from Clostridium thermoaceticum, a tungsten-selenium-iron protein. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:1826–1832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang Y-X, Tang L, Hutchinson C R. Cloning and characterization of a gene (msdA) encoding methylmalonic acid semialdehyde dehydrogenase from Streptomyces coelicolor. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:490–495. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.2.490-495.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]