Abstract

The COVID‐19 crisis has sparked a resurgence of scholarly interest in the issue of ageism. Whether the outbreak thwarts or facilitates efforts to combat ageism hinges upon public sentiments toward the older demographic. This study aims to explore discourse surrounding older adults by analyzing 183,179 related tweets posted during the COVID‐19 pandemic from February to December 2020. Overall, sentiments toward older adults became significantly less negative over time, being the least negative in April, August, and October, though the score remained below the neutral value throughout the 11 months. Our topic modelling analysis generated four themes: “The Need to Protect Older Adults” (41%), “Vulnerability and Mortality” (36%), “Failure of Political Leadership” (12%), and “Resilience” (11%). These findings indicate nascent support for older adults, though attempts to show solidarity may well worsen benevolent ageism.

INTRODUCTION

The COVID‐19 crisis has sparked a resurgence of scholarly interest in the perennial issue of ageism—a form of stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination on the basis of age (World Health Organization, 2021a). Globally, one in two people exhibits ageist attitudes toward older adults (World Health Organization, 2021b). On top of affecting one's health (B. Levy, 2009), ageism imposes a major financial burden on society. Negative age stereotypes and self‐perceptions of aging account for US$63 billion worth of healthcare costs annually (B. R. Levy et al., 2020). Meanwhile, discrimination against older persons in the workplace cost the US economy a whopping $850 billion in 2018 (AARP, 2020). Whether the outbreak thwarts or facilitates efforts to combat ageism hinges upon existing public sentiments toward the older demographic. Accordingly, this study aims to explore discourse surrounding older adults by analyzing tweets posted during the COVID‐19 pandemic from February to December 2020.

Research on age stereotypes argues that evaluations of older persons are complex and multidimensional (Brewer et al., 1981; Hummert, 1990; Hummert et al., 1994; Schmidt & Boland, 1986; Spaccatini et al., 2022). Specifically, the social category of the older person is a superordinate one that encompasses numerous subcategories, some of which are positive and others negative (Brewer et al., 1981; Hummert, 1990; Hummert et al., 1994; Schmidt & Boland, 1986; Sutter et al., 2022). Examples of negative subcategories include the “severely impaired” and the “shrew/curmudgeon,” while positive ones include the “perfect grandmother” and the “John Wayne conservative” (Brewer et al., 1981; Hummert, 1990; Hummert et al., 1994; Schmidt & Boland, 1986). As outlined by the communication predicament of aging model, even as one stereotypes an older person both positively and negatively, negative stereotypes tend to predominate, in turn affecting the dynamics of an intergenerational encounter (Ryan et al., 1995). For instance, the activation of negative stereotypes may cause one to speak to an older adult in a patronizing manner, subsequently setting in motion a negative feedback cycle with unfavorable outcomes for the older adult (Ryan et al., 1995).

Various studies have examined the themes of online discourse on older persons during the pandemic. Jimenez‐Sotomayor et al. (2020) looked at tweets posted over a 10‐day period in March 2020, while Xiang et al. (2021) analyzed tweets uploaded from January 2020 to April 2020. Both studies drew attention to the prevalence of explicitly ageist rhetoric on Twitter at the beginning of the outbreak. The belief that older adults were more vulnerable led many to downplay its severity and even engendered the spread of the invidious hashtag #BoomerRemover. Two other studies dissected content accompanying the hashtag #BoomerRemover during the months of March and April 2020 (Sipocz et al., 2021; Skipper & Rose, 2021). These analyses found clear evidence of ageism and intergenerational animosity in the tweets sampled, though Sipocz et al. (2021) also discovered signs of intergenerational unity in their dataset. Although these four studies have been instrumental in highlighting the reality of ageism on social media, they remain limited in two key aspects.

First, previous studies collected data using only age‐based queries—terms related to older adults—and the #BoomerRemover hashtag. Findings therefore dwelled largely on the prevalence of negative age stereotypes and hostile ageism during the outbreak. To gain a more nuanced understanding of how older adults are portrayed as well as to capture the complexities of ageism, our study broadens the search query by including terms related to older adults as well as a major subcategory: grandparents. Not only are grandparents viewed more positively than older adults in general (Hoogland & Hoogland, 2018; Newsham et al., 2020b; Ng & Indran, 2022a, 2022c), there have also been pleas during the pandemic to protect grandparents through the use of hashtags such as #NoHugsForGrandma and #StayHomeForGrandma (Ellerich‐Groppe et al., 2020).

Second, prior studies regarding online narratives on older persons during the pandemic were conducted during its early phase—from January to April 2020—and each over a short period. In contrast, our study analyzes narratives surrounding older adults on Twitter over an extensive period of 11 months, from February to December 2020. Much has changed since the onset of the COVID‐19 crisis. For example, it was toward the end of March 2020 that most countries instituted either a partial or full lockdown (Dunford et al., 2020). The closure of schools and workplaces meant that many parents had to juggle working remotely with looking after their children (Thomas, 2020). Grandparents became less viable as a childcare option due to safe distancing efforts to limit their exposure to the virus, hence prompting a renewed sense of appreciation for them (Ng & Indran, 2022a). Furthermore, 2020 was the year that COVID‐19 vaccines were being developed and that certain countries began vaccination campaigns (Mandavilli, 2020). It was also during this time that there were calls to include more older adults in vaccine clinical trials and to prioritize them in the rollout of vaccines (Morrow‐Howell, 2020).

Importantly, even as the pandemic amplified ageism, it provoked widespread reflections and insights, not least among which is the long‐overdue acknowledgment that society has failed the older community (Henning, 2020; Mills, 2021). Within the healthcare setting, older adults’ lives have been imperiled by the age‐based rationing of resources—a disquieting practice that many have criticized as being suggestive of older adults as an expendable group (Fraser et al., 2020). Governments across the globe have also come under fire for what has been deemed a flagrant mismanagement of the COVID‐19 situation (Ng et al., 2021b; Ng & Tan, 2021b). Nursing homes in various countries have emerged as hotbeds of infections as a result of policies which failed to prioritize the care of older adults (Amnesty International, 2020; Fallon et al., 2020). As of February 2021, nursing homes in the United States make up approximately 1.2 million COVID‐19 infections and 147,000 deaths (Kosar et al., 2021).

There have also been shows of intergenerational solidarity throughout the crisis. Initiatives such as pen pal programs have been implemented to mitigate the negative consequences of lockdowns on the well‐being of older people (Monahan et al., 2020). In addition, measures have been developed with the specific aim of protecting this group from possible exposure to the virus (Ellerich‐Groppe et al., 2020). For instance, in an endeavor to provide older adults with a safe shopping environment, many retailers have granted them designated shopping hours (Monahan et al., 2020). Although well‐intentioned, gerontologists caution that such initiatives may act as a catalyst for benevolent ageism—a subtle form of ageism marked by feelings of pity and overaccommodative behavior (Apriceno et al., 2020; Cary et al., 2017; Lytle et al., 2020). Nonetheless, in view of the support that has been given to older adults during the crisis, we hypothesize that sentiments toward them have become less negative over time (Hypothesis 1).

Several reasons make Twitter a compelling platform for this study. First, the micro‐blogging application witnessed a record number of users during the pandemic (Rojas, 2020), rendering it a powerful gauge of public sentiment, and in turn both implicit and explicit biases. Second, unlike surveys which tend to be time‐consuming and costly, Twitter serves as an invaluable source of data for drawing real‐time insights, which is particularly critical given the rapidly evolving pandemic and pandemic‐related discourse (Valdez et al., 2020). Third, although usage of Twitter has increased among older people, the Twitter user base continues to skew toward the young (Pew Research Center, 2021). According to stereotype embodiment theory, age stereotypes are internalized throughout one's life span, eventually becoming self‐definitions that predict health and well‐being in later life (B. Levy, 2009). When assimilated, negative stereotypes may reduce an older adult's sense of self‐efficacy, increase the risk of depression and affect both the immune and cardiovascular system (Auman et al., 2005; B. Levy, 2009; B. R. Levy et al., 2000, 2002). Conversely, positive self‐perceptions of aging are linked to improved functional health, well‐being and longevity (B. Levy, 2009; B. R. Levy et al., 2000, 2002). Evidence also shows that younger individuals who hold more negative age stereotypes are more likely to experience a cardiovascular event in later life than those with positive age stereotypes (B. R. Levy et al., 2009). It is thus important to study the types of narratives advanced and internalized by members of the Twitter community.

Our study is significant in the following regards. Conceptually, we contribute to literature on how older people are discussed on social media during the COVID‐19 crisis. As the pandemic continues to unfold, there remains ample room for research on the topic. Relative to past work (e.g., Jimenez‐Sotomayor et al., 2020; Xiang et al., 2021), we cover a broader time period of 11 months. In doing so, we underscore how narratives on older adults have been impacted by events such as the implementation of policies aimed at supporting older adults, the development of vaccines as well as controversies involving deaths in nursing homes. Moreover, unlike earlier inquiries, we include both age‐based (e.g., senior citizen) and role‐based terms (e.g., grandparent) to refer to older adults in our analysis to present a more holistic overview of how older people in general have been discursively constructed on Twitter. From a practical viewpoint, our study provides timely insights into public sentiments toward older persons, hence serving as a marker of how society has fared in caring for this cohort during the COVID‐19 crisis.

METHODS

Dataset

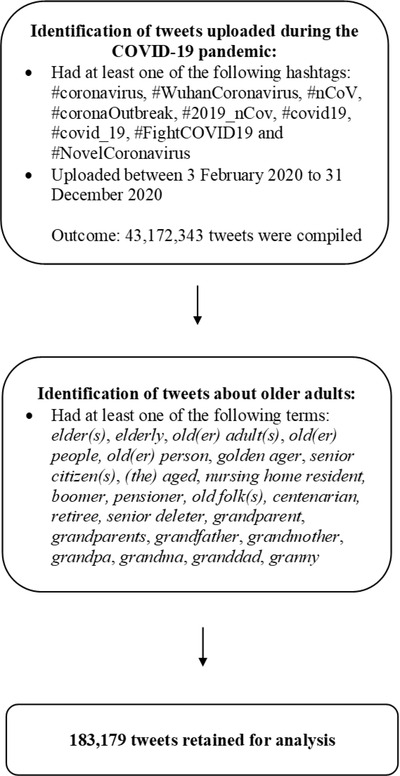

Data were retrieved using Twitter's standard search API (application programming interface) v1.1. The Twitter API allows users to query posts by keywords, hashtags, account handles, user IDs and time range (Gu et al., 2016). Content used for the analysis was limited to English tweets and spanned a period of 11 months, from 3 February to 31 December 2020. Tweets under the following hashtags were collected: #coronavirus, #WuhanCoronavirus, #nCoV, #coronaOutbreak, #2019_nCov, #covid19, #covid_19, #FightCOVID19, and #NovelCoronavirus. This process resulted in 43,172,343 tweets. We then extracted a subset of tweets using the following terms: elder(s), elderly, old(er) adult(s), old(er) people, old(er) person, golden ager, senior citizen(s), (the) aged, nursing home resident, boomer, pensioner, old folk(s), centenarian, retiree, senior deleter, grandparent, grandparents, grandfather, grandmother, grandpa, grandma, granddad, and granny. The selection of these terms was informed by earlier research on age‐based and role‐based framing (Ng & Indran, 2022a, 2022c). 183,179 tweets were retained for analysis. Figure 1 depicts the data collection process.

FIGURE 1.

Process of collating tweets related to older adults during the COVID‐19 pandemic from February to December 2020

Data pre‐processing and sentiment analysis

We began by pre‐processing the data since text on social media is raw and unstructured. Similar to past analyses (e.g., Li et al., 2020; Mackey et al., 2020), we removed the following attributes from the data: (a) notations such as the hashtag symbol (#), “RT” (retweet) and @ (user ID); (b) usernames; (c) hyperlinks; (d) stop words such as the, an and on; (e) punctuation marks; and (f) special characters such as emoticons or emojis. These attributes were removed to reduce the amount of noise or irrelevant information in the dataset.

Next, a sentiment score was calculated using a sentiment library which comprises words rated on a scale from 1 (very negative) to 5 (very positive) by two raters trained in gerontology. This sentiment library has proven valid and reliable in measuring words associated with age stereotypes and is consistent with past corpus‐based analyses (Ng, 2021b; Ng et al., 2015; Ng & Chow, 2021; Ng & Tan, 2021b, 2022). The methodology also supports literature on priming which indicates that the repeated association of negative words with older adults—or words within close lexical proximity—increases implicit ageism (B. Levy, 2009). Very negative collocates were rated 1 (e.g., devastating, tragedy), neutral collocates were rated 3 (e.g., tradition, insurance), and very positive collocates were rated 5 (e.g., blessing, acclaimed). For each month, we calculated a mean score which was then weighted (by the number of times the synonym appeared in that month) to determine a Twitter Aging Narrative Score (TANS) for all tweets.

Topic modelling

In addition to sentiment analysis, we analyzed the dataset from February to December 2020 using Biterm Topic Model (BTM)—a natural language processing method designed specifically for large‐scale short‐text data (Cheng et al., 2014) such as tweets. Unlike Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA), BTM circumvents the issue of data sparsity by directly modelling the biterm (an unordered word pair) on the entire corpus of tweets (Cheng et al., 2014). By analyzing co‐occurrence patterns, BTM categorizes short forms of text into clusters of topics (Yan et al., 2013).

We began the BTM analysis by setting K number of topics and T words per topic. The number of topics selected for extraction (K) impacts the results produced. Too many topics may result in a diffusion of signal, while too few topics may obscure possible signals in the topics (Li et al., 2020; Mackey et al., 2020). Following earlier research (e.g., Li et al., 2020; Mackey et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2019), we calculated a coherence score to identify the most appropriate K value. Given a topic z and its top T words Vz ,

where D(v) is the document frequency of word v, D(v, v′) is the number of documents words v and v′ co‐occurred (Yan et al., 2013). To evaluate the overall quality of a topic set, we calculated the average coherence score for each K value using the formula:

A coherence score is used to evaluate the performance of a topic model based on the K value and measures how correlated texts within the clusters are. The higher the coherence score, the more correlated the texts in the cluster are with each other. We calculated the coherence score for six K values (K = 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60). K = 20 emerged as the optimal number of topics. A higher K value results in diminishing returns in coherence scores at the risk of excessive topic splintering (Li et al., 2020; Mackey et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2019). The output of the BTM was set to display the top 15 words (T) with the highest correlation with each topic.

RESULTS

Sentiment analysis

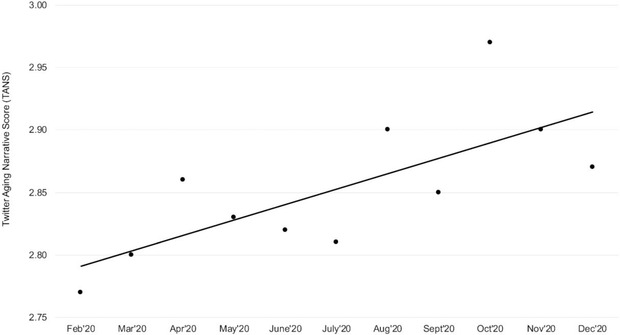

Overall, sentiments toward older adults—rated from 1 (very negative) to 5 (very positive)—remained below the neutral score of 3 throughout the 11 months of the COVID‐19 crisis, though it became significantly less negative (β = .0123, p = .0118) over time. This supports Hypothesis 1. The sentiment scores were the least negative in April, August, and October 2020 (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Trajectory of Sentiments toward Older Adults on Twitter over 11 months (February–December 2020) during the COVID‐19 Pandemic. Overall, sentiments toward older adults—rated from 1 (very negative) to 5 (very positive)—remained below the neutral score of 3 throughout the pandemic, though they became significantly less negative. Sentiments were the least negative in April, August, and October 2020. The solid line represents the best fit line and the dots represent the mean sentiment score of relevant tweets for the respective month.

Topic modelling

The BTM analysis generated 20 sub‐topics which were subsequently grouped into four broad themes. Topic 1 (41%) pertains to “the need to protect older adults.” Sub‐topics include limiting physical contact with grandparents, staying at home to prevent possible transmission of the virus to older family members as well as initiatives aimed at supporting older adults. Examples of these initiatives are the implementation of senior shopping hours in supermarkets as well as the prioritization of older people for COVID‐19 vaccination. Topic 2 (36%) concerns the “vulnerability and mortality of older adults.” Topic 3 (12%) is about the “failure of political leadership.” Sub‐topics consist of the perceived failure of the government to contain the virus as well as protests which emerged in response to deaths in nursing homes. Topic 4 (11%) touches on the “resilience” of older individuals who survived the COVID‐19 infection. Table 1 provides the breakdown of narratives by percentage as well as sample sub‐topics, terms and tweets associated with each topic.

TABLE 1.

Four major themes distilled from 183,179 tweets about older adults and the COVID‐19 pandemic across 11 months from February to December 2020

| Themes | Sub‐themes | Sample terms | Sample tweets |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Need to Protect Older Adults (41%) | Taking steps to prevent potential transmission of the virus to older adults | Home, avoid, meet, care, kill, hug, grocery, shop, vaccine, receive | “We need to consider every preventative measure to protect the well‐being & health of our grandmothers and grandfathers” |

| Programs aimed at limiting older adults' exposure to the virus | |||

| Vulnerability and Mortality of Older Adults (36%) | High hospitalization or mortality rate among older adults | Vulnerable, die, death, severe, risk, condition, hospital, test, positive, health | “Older people need to be very very careful against #coronaoutbreak, death rate is highest for this group. infections in young are recoverable.” |

| Beliefs that older adults are an at‐risk cohort | |||

| Failure of Political Leadership (12%) | Beliefs that politicians are responsible for the high death toll among older adults | Trump, heartless, arrogant, bureaucrat, republican, governor, advisor, protest, leader |

“#COVID19 death tally would be lower #Cuomo hadn't crammed old people into nursing homes. #CuomoMustGo #CuomoKilledGrandma” |

| Resilience (11%) | Older survivors of the virus | Recover, beat, fight, survive, birthday, visit, recovery, love | “Grandma who survived COVID‐19 after ICU stay delivers 800 handmade tamales to Cedars‐Sinai workers” |

DISCUSSION

This study analyzed discourse surrounding older adults on Twitter over a period of 11 months during the COVID‐19 crisis. In contrast to prior studies which evaluated tweets related to older adults during the pandemic (Jimenez‐Sotomayor et al., 2020; Sipocz et al., 2021; Skipper & Rose, 2021; Xiang et al., 2021), our study covered a broader time period and included search terms pertaining not just to older adults, but also to grandparents. Whereas these earlier studies discovered the presence of hostile ageism on Twitter at the start of the crisis (Jimenez‐Sotomayor et al., 2020; Sipocz et al., 2021; Skipper & Rose, 2021; Xiang et al., 2021), our findings revealed that ageism in the Twitter sphere became more nuanced as the crisis unfolded throughout 2020, with narratives centered around two main topics: the need to protect older adults (41%) as well as their vulnerability and mortality (36%).

As hypothesized, sentiments toward older people became less negative from February to December 2020, with sentiments being the least negative in April, August, and October. Supportive responses at the community level surfaced between the end of March and the start of April. Many stores started offering “senior‐only shopping hours” and programs involving the delivery of groceries and meals to older adults were launched (Monahan et al., 2020). Concerns that older adults might suffer from social isolation and loneliness also kickstarted pen pal initiatives aimed at connecting older and younger individuals (Monahan et al., 2020; Zaveri, 2020).

In August 2020, COVID‐19 vaccines yielded promising results in clinical trials which included older adults (Loftus, 2020), raising hopes that the cohort presumed to be most at risk would be protected from the virus. Grandparents’ Day in both Australia and the United Kingdom falls in October, which could account for why sentiments toward older adults were the least negative then. Tweets uploaded this month reflected an appreciation for grandparents and their contributions to the family, a finding which corroborates recent work stating that older people tend to be stereotyped positively when framed according to their roles as grandparents (Hoogland & Hoogland, 2018; Newsham et al., 2020a; Ng & Indran, 2022a, 2022c). All these events may have led to the spread of more hopeful and uplifting narratives on Twitter in April, August, and October.

Of noteworthy importance is that even though sentiments toward older adults became less negative over time, the sentiment score remained below the neutral value of 3 throughout, never quite reaching the positive side of the continuum. In 2020, younger people were accused by politicians and journalists of being cavalier about the virus and non‐compliant with safe distancing measures, thus endangering the lives of older persons (Bland, 2020; Stevens, 2020). Furthermore, there were suggestions to issue a lockdown only for older adults so that the rest of society would be able to regain some semblance of normalcy and freedom (Farrell, 2020). Some also stereotyped older people as refusing to wear masks (Ng & Indran, 2022b). Tension between the generations as well as negative stereotypes of older adults during the pandemic may have therefore served as countervailing forces that hindered greater improvements in the sentiment score.

The fact that the sentiment score has nonetheless shifted in a positive direction is indicative of nascent support for older adults. That said, attempts to show solidarity may well worsen benevolent ageism—an insidious form of prejudice occasioned by the belief that older adults are pitiful, helpless, and incompetent (Cuddy et al., 2007; Swift & Chasteen, 2021; Vale et al., 2020). Since the onset of the pandemic, older adults have been repeatedly portrayed in mainstream discourse as a high‐risk population for COVID‐19 mortality (Ayalon, 2020). Similar to previous studies (Jimenez‐Sotomayor et al., 2020; Xiang et al., 2021), our analysis illustrated that a large percentage (36%) of online discourse on older adults revolved around their vulnerability and mortality.

However, while prior analyses of tweets uploaded in March and April 2020 pointed out that there was a prevalence of hostile ageism (Sipocz et al., 2021), we found that the frequent conflation of old age with vulnerability led to numerous instances of benevolent ageism, as evident from how the need to protect older adults (41%) dominated the narratives throughout 2020. Using hashtags such as #StayHomeForGrandma, #StayHomeSaveLives, and #DontKillGrandma, many users on Twitter emphasized the need to behave in a socially responsible manner and to look out for older family members. Another portion of the narratives focused on the implementation of measures targeted at supporting older individuals, with many praising initiatives adopted by supermarkets allowing older customers to shop at designated hours. Likewise, there were calls among the Twitter community for older people to be given priority for vaccination, echoing findings that the endorsement of benevolent ageism predicts the prioritization of older people in healthcare decision‐making (Apriceno et al., 2020).

As indicated by the communication predicament of aging model, negative age stereotypes typically exercise primacy over positive ones in shaping intergenerational interactions (Hummert, 2017; Hummert et al., 1994; Ng, 2021a; Ryan et al., 1995). Although fueled by good intentions, benevolent ageism reflects and reinforces the oversimplistic belief that being old is tantamount to being incompetent. This may encourage paternalistic thinking or decision‐making, subsequently impinging on older adults’ sense of agency (Allen & Ayalon, 2021; Lichtenstein, 2020; Vale et al., 2020). Past literature argues that such paternalistic behavior may produce self‐fulfilling prophecies, whereby older individuals internalize beliefs of low self‐efficacy and act in a manner that aligns with such stereotypes (Cary et al., 2017; B. Levy, 2009). Following Levy's (2009) theory of stereotype embodiment, this may reduce older adults’ sense of empowerment and self‐esteem while affecting their social, psychological, and physical functioning (Baltes & Wahl, 1996; Hehman & Bugental, 2015; Vervaecke & Meisner, 2020). The compulsion to show compassion may also lead young people to exhibit behaviors older adults might deem patronizing (Ryan et al., 1995; Vervaecke & Meisner, 2020), which could then exacerbate tension between the generations.

The third group of tweets (12%) was about the failure of political leadership. Hashtags such as #CuomoKilledGrandma circulated widely after New York Governor, Andrew Cuomo, issued a directive which forced older adults who tested positive for COVID‐19 into nursing homes. The politician recently drew another round of backlash for allegedly undercounting the number of deaths in nursing homes (Cohrs, 2021). Concerns regarding political negligence also surfaced in countries other than the United States. In the United Kingdom, worries that the National Health Service would be overwhelmed led to hospitalized patients being transferred to nursing homes without first being tested for the virus. Similarly, inadequate measures by government bodies in Sweden contributed to the high mortality rate in nursing homes (Ahlander & Pollard, 2020).

Even as these incidents paint a grim picture of the reality of systemic ageism, they have thrust nursing homes into the spotlight, spurring political awakenings across various communities (Astor, 2021). Our results show that members of the public are incensed by the perceived culpability of politicians regarding the high death toll among older people. There have even been protests in some countries, particularly among family members of nursing home residents who have died from the virus (Aguilar, 2021; Moynihan & Shahrigian, 2020). Hence, while generally construed as a negative emotion, anger can be constructive insofar as it galvanizes individuals to fix perceived injustices and take collective action (Lambert et al., 2019; Renström & Bäck, 2021). This reiterates past findings on how some Twitter users implored others not to use the hashtag #BoomerRemover when pleading for intergenerational unity (Sipocz et al., 2021; Skipper & Rose, 2021).

At the same time, it must be stressed that the extensive media coverage of the high mortality rates in nursing homes may perpetuate benevolent ageism by evoking discourses of pity that reduce older adults to a state of passivity and victimhood. This could then serve to legitimize discriminatory practices that end up limiting the rights and autonomy of older people (Bugental & Hehman, 2007). Repeated exposure to such news may even generate a “collapse of compassion,” a situation whereby the tendency to empathize or render help reduces as the number of people in need of aid increases (Seppala et al., 2017). The public may then become desensitized to the plight of nursing home residents, which could obliterate the need to take collective action.

Whether content on social media is more positive or negative remains a point of contention among the scholarly community (Jalonen, 2014). However, in this time of COVID‐19 where feelings of anxiety and fear prevail (Renström & Bäck, 2021; Steinert, 2020), it makes sense that only 11% of the narratives involved stories of resilience and hope. Examples of these include tweets about older survivors of the virus (Burke, 2020; Salo, 2020; Woods, 2020).

Our study makes a case for greater discussion on the nuances of ageism. It is important to recognize that prejudice can be masked by compassion (Vervaecke & Meisner, 2020). Despite the reality that benevolent ageism is much more pervasive than hostile ageism, evidence suggests that individuals, regardless of age, tend to perceive acts of benevolent ageism as more acceptable than those of hostile ageism (Horhota et al., 2019). As frequent acts of benevolent ageism may have a cumulative and harmful impact on older adults (Horhota et al., 2019), sustained efforts should be made to promote greater public understanding of the many insidious ways in which ageism manifests. This will ensure that those well‐meaning displays of solidarity are not undercut by patronizing language or actions.

In creating opportunities for intergenerational contact, it is vital that these opportunities are reconceived as experiences beneficial to both the young and old rather than as a service which positions older adults as recipients of help. Leveraging social media to reach a broader audience—especially during this time when physical interaction is limited—may also prove useful for building intergenerational relationships (Lytle et al., 2022; Ng & Indran, 2022b; Spaccatini et al., 2022; Sutter et al., 2022) and will complement existing offline interventions aimed at reducing ageism.

As coverage on COVID‐19 continues to dominate the headlines, messages propagated by the media should be crafted more tactfully in order not to be inimical to ongoing calls to reframe aging (Busso et al., 2019; Jarrott et al., 2019; Ng, 2021a; Ng & Indran, 2022d; Sweetland et al., 2017). Besides ensuring that older persons are not constantly singled out as a homogeneous entity, inclusive terms such as “we” and “us” should be used to avoid perpetuating an “us versus them” mindset (Berridge & Hooyman, 2020; Schnell et al., 2021). This will replace the existing narrative from one of COVID‐19 as a virus that older adults must be protected from to one that sees the pandemic as a broader issue which society can overcome as a collective (Xiang et al., 2021). Social media should also be employed as an avenue to share optimistic narratives on older adults to counteract the spread of inaccurate age stereotypes as well as to improve younger people's perceptions of old age (Ng, Indran et al., 2022; Ng & Indran, 2022b, 2022d). In line with stereotype embodiment theory, this will lead to better health outcomes among younger people when they eventually enter later life (B. Levy, 2009). Older people too will have a more positive outlook on the aging process, hence improving their physiological outcomes (B. R. Levy et al., 2000, 2002).

Crucially, regular media coverage on the impact of COVID‐19 on the older population should not be viewed as mere trends, but as starting points for further discussion on the need to rectify systemic shortcomings (Allen & Ayalon, 2021). In preparing for a post‐pandemic future, governments worldwide must place older persons at the center of policy responses (World Economic Forum, 2020). Policymakers should be mindful not to cast older adults as objects to be pitied (Ng, Chow et al., 2022). Evoking the sympathy of the public is not the same as evoking their “systems thinking,” a mindset which considers how various mechanisms interact to impact the lives of older adults (Sweetland et al., 2017). The public must therefore be attuned to the fact that ageism is a systemic issue which requires systemic solutions. Additionally, support for older persons online should be translated into collective action offline. Policymakers and advocates could frame messages in a way that appeals to an individual's sense of justice (Gamson et al., 1992) and that includes a call to action (Snow & Benford, 1988). Ultimately, the issue of ageism must be seen as one of personal relevance and that everyone has a vested interest in eliminating.

This study has limitations which must be addressed. First, we collected only textual data even though tweets often contain visual elements such as photos, videos, and GIFs. This is a drawback which can be overcome in the future when multimodal techniques are developed to analyze both textual and visual content on Twitter. Second, we acknowledge that Twitter users are not representative of the wider population and that only publicly available tweets were included in the dataset. However, as most accounts on Twitter are open to the public (Beevolve, 2021), tweets collected are likely to be representative of the Twitter community. Third, since we did not have information regarding users’ demographics—Twitter does not require users to publish demographic data and scholars have brought up the limitations of analyzing publicly provided demographic information on social media (Goga et al., 2015; Sloan, 2017)—we were unable to fully contextualize the reasons for the sentiment scores.

It is unclear whether the overall improvement in sentiments toward older persons is a result of our inclusion of role‐based terms or a result of greater support for them. To ascertain whether sentiments toward older persons have indeed become less negative, future studies could explore using survey techniques (Lakra et al., 2012; Ng et al., 2016; Ng, Allore et al., 2020; Ng & Levy, 2018; Ng & Rayner, 2010; Ng, Tan et al., 2022) and analyzing big data (Giest & Ng, 2018; Ng, 2018; Ng, Lim et al., 2020; Ng & Tan, 2021a). Qualitative approaches could be used to look at how the pandemic has impacted relationships between individuals and older family members. In addition, since most of the tweets analyzed covered issues taking place in the West, it may be worthwhile for future scholarship to examine the effect of the pandemic on intergenerational relations in cultures where attitudes toward old age are more positive (Ng et al., 2021a; Ng & Indran, 2021a, 2021b; Ng & Lim, 2021).

Despite the calamitous toll that the COVID‐19 pandemic has taken on the lives of older adults, it has nevertheless brought about emerging support for them as highlighted in our study. As societies envision a post‐COVID‐19 future, it is imperative that a more equitable environment for the older cohort is created. This means eliminating ageist attitudes and supporting older persons in a way that welcomes expressions of autonomy and competence.

Biographies

Reuben Ng is an Assistant Professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore (NUS). He trained as a behavioral and data scientist at NUS, Oxford, Yale, and had careers in management consulting and government before returning to academia. His research interests include ageism, social gerontology, and quantitative social science. Visit http://www.drreubenng.com for more details.

Nicole Indran is a Research Assistant based at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, NUS. She graduated with an honors degree in sociology from the National University of Singapore. Her research interests include ageism, age stereotypes, and intergenerational relations.

Luyao Liu is a Research Associate at the Lloyd's Register Foundation Institute for the Public Understanding of Risk, NUS. She has a Master of Science in Statistics from the National University of Singapore. Her research interest is in social media data mining.

Ng, R. , Indran, N. , & Liu, L. (2022) Ageism on Twitter during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Journal of Social Issues, 00, 1–18. 10.1111/josi.12535

REFERENCES

- AARP. (2020) The Economic Impact of Age Discrimination: How Discriminating Against Older Workers Could Cost the U.S. Economy $850 Billion. AARP Thought Leadership, 10.26419/int.00042.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar, B. (2021) “Please help”: Protest held outside Toronto long‐term care home with deadly outbreak. CTV News. https://toronto.ctvnews.ca/please‐help‐protest‐held‐outside‐toronto‐long‐term‐care‐home‐with‐deadly‐outbreak‐1.5261110 [Google Scholar]

- Ahlander, J. & Pollard, N. (2020) Sweden failed to protect elderly in COVID pandemic, commission finds. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/health‐coronavirus‐sweden‐commission‐idUSKBN28P1PP [Google Scholar]

- Allen, L.D. , Ayalon, L. (2021) “It's pure panic”: the portrayal of residential care in American Newspapers during COVID‐19. The Gerontologist, 61(1), 86–97. 10.1093/geront/gnaa162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amnesty International. (2020) As if Expendable: The UK Government's Failure to Protect Older People in Care Homes During the COVID‐19 Pandemic. Amnesty International. [Google Scholar]

- Apriceno, M. , Lytle, A. , Monahan, C. , Macdonald, J. & Levy, S.R. (2020) Prioritizing health care and employment resources during COVID‐19: roles of benevolent and hostile ageism. The Gerontologist, 61, 98–102, gnaa165. 10.1093/geront/gnaa165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astor, M. (2021) How 535,000 Covid Deaths Spurred Political Awakenings Across America. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/17/us/politics/covid‐survivors.html [Google Scholar]

- Auman, C. , Bosworth, H.B. & Hess, T.M. (2005) Effect of health‐related stereotypes on physiological responses of hypertensive middle‐aged and older men. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 60(1), P3–P10. 10.1093/geronb/60.1.P3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayalon, L. (2020) There is nothing new under the sun: ageism and intergenerational tension in the age of the COVID‐19 outbreak. International Psychogeriatrics, 32(10), 1221–1224. 10.1017/S1041610220000575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltes, M. & Wahl, H.‐W. (1996) Patterns of communication in old age: the dependence‐support and independence‐ignore script. Health Communication, 8(3), 217–231. 10.1207/s15327027hc0803_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beevolve . (2021) An Exhaustive Study of Twitter Users Across the World. Beevolve. http://www.beevolve.com/twitter‐statistics/

- Berridge, C. & Hooyman, N. (2020) The consequences of ageist language are upon us. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 63, 508–512, http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01634372.2020.1764688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland, A. (2020) Ravers and boomers: Is intergenerational Covid tension real? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/aug/09/ravers‐and‐boomers‐is‐intergenerational‐covid‐tension‐real [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, M.B. , Dull, V. & Lui, L. (1981) Perceptions of the elderly: Stereotypes as prototypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41(4), 656–670. 10.1037/0022-3514.41.4.656 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bugental, D.B. & Hehman, J.A. (2007) Ageism: A Review of Research and Policy Implications. Ageism. Social Issues and Policy Review, 1(1), 173–216. 10.1111/j.1751-2409.2007.00007.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burke, M. (2020) At 102 years old, New York woman beats the coronavirus—Twice. NBC News, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us‐news/102‐years‐old‐new‐york‐woman‐beats‐coronavirus‐twice‐n1249863 [Google Scholar]

- Busso, D.S. , Volmert, A. & Kendall‐Taylor, N. (2019) Reframing aging: effect of a short‐term framing intervention on implicit measures of age bias. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 74(4), 559–564. 10.1093/geronb/gby080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cary, L.A. , Chasteen, A.L. & Remedios, J. (2017) The ambivalent ageism scale: developing and validating a scale to measure benevolent and hostile ageism. The Gerontologist, 57(2), e27–e36. 10.1093/geront/gnw118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, X. , Yan, X. , Lan, Y. & Guo, J. (2014) BTM: Topic modeling over short texts. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering, 26(12), 2928–2941. 10.1109/TKDE.2014.2313872 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohrs, R. (2021) Cuomo's nursing home fiasco shows the ethical perils of policymaking. STAT, https://www.statnews.com/2021/02/26/cuomos‐nursing‐home‐fiasco‐ethical‐perils‐pandemic‐policymaking/ [Google Scholar]

- Cuddy, A.J.C. , Fiske, S.T. & Glick, P. (2007) The BIAS map: behaviors from intergroup affect and stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(4), 631–648. 10.1037/0022-3514.92.4.631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunford, D. , Dale, B. , Stylianou, N. , Lowther, E. , Ahmed, M. & de la Torre Arenas, I. (2020) Coronavirus: the world in lockdown in maps and charts—BBC News. BBC News, https://www.bbc.com/news/world‐52103747 [Google Scholar]

- Ellerich‐Groppe, N. , Schweda, M. & Pfaller, L. (2020) #StayHomeForGrandma – towards an analysis of intergenerational solidarity and responsibility in the coronavirus pandemic. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 2(1), 100085. 10.1016/j.ssaho.2020.100085 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fallon, A. , Dukelow, T. , Kennelly, S.P. & O'Neill, D. (2020) COVID‐19 in nursing homes. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, 113(6), 391–392. 10.1093/qjmed/hcaa136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, C. (2020) A pandemic lockdown just for older people? No! Forbes, https://www.forbes.com/sites/nextavenue/2020/07/03/a‐pandemic‐lockdown‐just‐for‐older‐people‐no/ [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, S. , Lagacé, M. , Bongué, B. , Ndeye, N. , Guyot, J. , Bechard, L. , Garcia, L. , Taler, V. , CCNA Social Inclusion and Stigma Working Group , Adam, S. , Beaulieu, M. , Bergeron, C.D. , Boudjemadi, V. , Desmette, D. , Donizzetti, A.R. , Éthier, S. , Garon, S. , Gillis, M. , Levasseur, M. , Lortie‐Lussier, M. , Marier, P. , Robitaille, A. , Sawchuk, K. , Lafontaine, C. & Tougas, F. (2020) Ageism and COVID‐19: What does our society's response say about us? Age and Ageing, 49(5), 692–695. 10.1093/ageing/afaa097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamson, W.A. , Gamson, G. , Anthony, W. , Gamson, W.A. & Gamson, W.A. (1992) Talking politics. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Giest, S. & Ng, R. (2018) Big data applications in governance and policy. Politics and Governance, 6(4), 1–4. 10.17645/pag.v6i4.1810 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goga, O. , Loiseau, P. , Sommer, R. , Teixeira, R. & Gummadi, K.P. (2015) On the Reliability of Profile Matching Across Large Online Social Networks. Proceedings of the 21th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 1799–1808. 10.1145/2783258.2788601 [DOI]

- Gu, Y. , Qian, Z. & Chen, F. (2016) From twitter to detector: real‐time traffic incident detection using social media data. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 67, 321–342. 10.1016/j.trc.2016.02.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hehman, J.A. & Bugental, D.B. (2015) Responses to patronizing communication and factors that attenuate those responses. Psychology and Aging, 30(3), 552–560. 10.1037/pag0000041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henning, B. (2020) Opinion | How Government ‘Failed the Elderly’ in the Coronavirus Pandemic. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/22/opinion/letters/coronavirus‐nursing‐homes.html [Google Scholar]

- Hoogland, A.I. & Hoogland, C.E. (2018) Learning by listing: A content analysis of students’ perceptions of older adults and grandparents. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 39(1), 61–74. 10.1080/02701960.2016.1152271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horhota, M. , Chasteen, A.L. & Crumley‐Branyon, J.J. (2019) Is ageism acceptable when it comes from a familiar partner? The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 74(4), 595–599. 10.1093/geronb/gby066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummert, M.L. (1990) Multiple stereotypes of elderly and young adults: a comparison of structure and evaluations. Psychology and Aging, 5(2), 182–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummert, M.L. (2017) Communication with Older Adults. In: Pachana, N. A. (Ed.) Encyclopedia of geropsychology. Springer, pp. 569–575. 10.1007/978-981-287-082-7_267 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hummert, M.L. , Wiemann, J.M. & Nussbaum, J.F. (1994) Stereotypes of the elderly and patronizing speech. In: Interpersonal communication in older adulthood: interdisciplinary theory and research. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Jalonen, H. (2014) Social media – an arena for venting negative emotions. Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies, 4(October 2014‐Special Issue), 53–70. 10.30935/ojcmt/5704 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrott, S.E. , Hooker, K. & Morrow‐Howell, N. (2019) Reframing aging: practices and measures to harness the strength of intergenerational network ties. Innovation in Aging, 3(Suppl 1), S625–S626. 10.1093/geroni/igz038.2330 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez‐Sotomayor, M.R. , Gomez‐Moreno, C. & Soto‐Perez‐de‐Celis, E. (2020) Coronavirus, ageism, and twitter: an evaluation of tweets about older adults and COVID‐19. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 68(8), 1661–1665. 10.1111/jgs.16508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosar, C.M. , White, E.M. , Feifer, R.A. , Blackman, C. , Gravenstein, S. , Panagiotou, O.A. , Mcconeghy, K. & Mor, V. (2021) COVID‐19 mortality rates among nursing home residents declined from March to November 2020. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 40(4), 655–663. 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.02191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakra, D.C. , Ng, R. & Levy, B.R. (2012) Increased longevity from viewing retirement positively. Ageing & Society, 32(8), 1418–1427. 10.1017/S0144686/11000985 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, A. , Eadeh, F. & Hanson, E. (2019) Anger and its consequences for judgment and behavior: recent developments in social and political psychology. In: Advances in experimental social psychology. 10.1016/bs.aesp.2018.12.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levy, B. (2009) Stereotype embodiment. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(6), 332–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy, B.R. , Hausdorff, J.M. , Hencke, R. & Wei, J.Y. (2000) Reducing cardiovascular stress with positive self‐stereotypes of aging. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 55(4), P205–P213. 10.1093/geronb/55.4.P205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy, B.R. , Slade, M.D. , Chang, E.‐S. , Kannoth, S. & Wang, S.‐Y. (2020) Ageism amplifies cost and prevalence of health conditions. The Gerontologist, 60(1), 174–181. 10.1093/geront/gny131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy, B.R. , Slade, M.D. , Kunkel, S.R. & Kasl, S.V. (2002) Longevity increased by positive self‐perceptions of aging. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(2), 261–270. 10.1037//0022-3514.83.2.261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy, B.R. , Zonderman, A.B. , Slade, M.D. & Ferrucci, L. (2009) Age stereotypes held earlier in life predict cardiovascular events in later life. Psychological Science, 20(3), 296–298. 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02298.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. , Chen, W.‐H. , Xu, Q. , Shah, N. , Kohler, J.C. & Mackey, T.K. (2020) Detection of self‐reported experiences with corruption on twitter using unsupervised machine learning. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 2(1), 100060. 10.1016/j.ssaho.2020.100060 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein, B. (2020) From “Coffin Dodger” to “Boomer Remover”: outbreaks of ageism in three countries with divergent approaches to coronavirus control. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 76(4), e206–e212. 10.1093/geronb/gbaa102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loftus, P. (2020) Moderna says Covid‐19 vaccine shows signs of working in olderadults. Wall Street Journal, https://www.wsj.com/articles/moderna‐says‐covid‐19‐vaccine‐shows‐signs‐of‐working‐in‐older‐adults‐11598452800 [Google Scholar]

- Lytle, A. , Apriceno, M. , Macdonald, J. , Monahan, C. & Levy, S.R. (2020) Pre‐pandemic ageism toward older adults predicts behavioral intentions during the COVID‐19 pandemic. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 77, e11–e15, gbaa210. 10.1093/geronb/gbaa210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytle, A. , Macdonald, J. & Levy, S.R. (2022) An experimental investigation of a simulated online intergenerational friendship. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 0(0), 1–12. 10.1080/02701960.2021.2023810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackey, T. , Purushothaman, V. , Li, J. , Shah, N. , Nali, M. , Bardier, C. , Liang, B. , Cai, M. & Cuomo, R. (2020) Machine learning to detect self‐reporting of symptoms, testing access, and recovery associated with COVID‐19 on twitter: retrospective big data infoveillance study. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 6(2), e19509. 10.2196/19509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandavilli, A. (2020) The Next Vaccine Challenge: Reassuring Older Americans. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/14/health/coronavirus‐vaccine‐elderly.html [Google Scholar]

- Mills, L. (2021) Covid‐19 Exposed Need to Protect Older People's Rights. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/03/04/covid‐19‐exposed‐need‐protect‐older‐peoples‐rights [Google Scholar]

- Monahan, C. , Macdonald, J. , Lytle, A. , Apriceno, M. & Levy, S.R. (2020) COVID‐19 and ageism: How positive and negative responses impact older adults and society. American Psychologist, 75(7), 887. 10.1037/amp0000699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow‐Howell, N. (2020) Why older people are among the first to get the vaccine | Institute for Public Health |. Washington University in St. Louis. Washington University in St. Louis: Institute for Public Health. https://publichealth.wustl.edu/why‐older‐people‐are‐among‐the‐first‐to‐get‐the‐vaccine/ [Google Scholar]

- Moynihan, E. & Shahrigian, S. (2020) Protesters demand Cuomo apology over COVID deaths in nursing homes. New York Daily News. https://www.nydailynews.com/news/politics/new‐york‐elections‐government/ny‐andrew‐cuomo‐20201018‐533pxrrc6zfxtbg5nq2yolagde‐story.html [Google Scholar]

- Newsham, T.M.K. , Schuster, A.M. , Guest, M.A. , Nikzad‐Terhune, K. & Rowles, G.D. (2020a) College students’ perceptions of “old people” compared to “grandparents.” Educational Gerontology,47, 63–71, 10.1080/03601277.2020.1856918 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newsham, T.M.K. , Schuster, A.M. , Guest, M.A. , Nikzad‐Terhune, K. & Rowles, G.D. (2020b) College students’ perceptions of “old people” compared to “grandparents. Educational Gerontology, 47, 63–71. 10.1080/03601277.2020.1856918 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, R. (2018) Cloud computing in Singapore: key drivers and recommendations for a smart nation. Politics and Governance, 6(4), 39–47. 10.17645/pag.v6i4.1757 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, R. (2021a) Societal age stereotypes in the U.S. and U.K. from a media database of 1.1 billion words. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 8822. 10.3390/ijerph18168822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, R. (2021b) Anti‐Asian sentiments during COVID‐19 across 20 countries: analysis of a 12‐billion‐word News Media Database. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23, e28305, 10.2196/28305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, R. , Allore, H.G. & Levy, B.R. (2020) Self‐acceptance and interdependence promote longevity: evidence from a 20‐year prospective cohort study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(16), 5980. 10.3390/ijerph17165980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, R. , Allore, H.G. , Monin, J.K. & Levy, B.R. (2016) Retirement as meaningful: positive retirement stereotypes associated with longevity. The Journal of Social Issues, 72(1), 69–85. 10.1111/josi.12156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, R. , Allore, H.G. , Trentalange, M. , Monin, J.K. & Levy, B.R. (2015) Increasing negativity of age stereotypes across 200 years: evidence from a database of 400 million words. PLOS ONE, 10(2), e0117086. 10.1371/journal.pone.0117086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, R. & Chow, T.Y.J. (2021) Aging narratives over 210 years (1810‐2019). The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 76(9), 1799–1807. 10.1093/geronb/gbaa222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, R. , Chow, T.Y.J. & Yang, W. (2021a) Culture linked to increasing ageism during Covid‐19: evidence from a 10‐billion‐word corpus across 20 countries. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 76(9), 1808–1816. 10.1093/geronb/gbab057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, R. , Chow, T.Y.J. & Yang, W. (2021b) News media narratives of Covid‐19 across 20 countries: early global convergence and later regional divergence. PLOS ONE, 16(9), e0256358. 10.1371/journal.pone.0256358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, R. , Chow, T.Y.J. & Yang, W. (2022) The impact of aging policy on societal age stereotypes and ageism. The Gerontologist, 62(4), 598–606. 10.1093/geront/gnab151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, R. & Indran, N. (2021a) Societal narratives on caregivers in Asia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11241. 10.3390/ijerph182111241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, R. & Indran, N. (2021b) Societal perceptions of caregivers linked to culture across 20 countries: evidence from a 10‐billion‐word database. PLOS ONE, 16(7), e0251161. 10.1371/journal.pone.0251161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, R. & Indran, N. (2022a) Reframing aging during COVID‐19: familial role‐based framing of older adults linked to decreased ageism. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 70(1), 60–66. 10.1111/jgs.17532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, R. & Indran, N. (2022b) Hostility towards baby boomers on tiktok. The Gerontologist, gnac020. 10.1093/geront/gnac020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, R. & Indran, N. (2022c) Role‐based framing of older adults linked to decreased ageism over 210 years: evidence from a 600‐million‐word historical corpus. The Gerontologist, 62(4), 589–597. 10.1093/geront/gnab108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, R. & Indran, N. (2022d) Not too old for tiktok: how older adults are reframing aging. The Gerontologist, gnac055. 10.1093/geront/gnac055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ng, R. , Indran, N. & Liu, L. (2022) A playbook for effective age advocacy on twitter. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 10.1111/jgs.17909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, R. & Levy, B. (2018) Pettiness: conceptualization, measurement and cross‐cultural differences. PLOS ONE, 13(1), e0191252. 10.1371/journal.pone.0191252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, R. , Lim, S.Q. , Saw, S.Y. & Tan, K.B. (2020) 40‐year projections of disability and social isolation of older adults for long‐range policy planning in Singapore. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(14), 4950. 10.3390/ijerph17144950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, R. & Lim, W.J. (2021) Ageism Linked to Culture, Not Demographics: Evidence From an 8‐Billion‐Word Corpus Across 20 Countries. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 76(9), 1791–1798. 10.1093/geronb/gbaa181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, R. & Rayner, S. (2010) Integrating psychometric and cultural theory approaches to formulate an alternative measure of risk perception. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, 23(2), 85–100. 10.1080/13511610.2010.512439 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, R. & Tan, K.B. (2021a) Implementing an individual‐centric discharge process across Singapore public hospitals. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 8700. 10.3390/ijerph18168700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, R. & Tan, Y.W. (2021b) Diversity of COVID‐19 news media coverage across 17 countries: the influence of cultural values, government stringency and pandemic severity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(22), 11768. 10.3390/ijerph182211768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, R. & Tan, Y.W. (2022) Media attention toward COVID‐19 across 18 countries: the influence of cultural valuesand pandemic severity. PLOS ONE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, R. , Tan, Y.W. & Tan, K.B. (2022) Cohort profile: Singapore's nationally representative retirement and health study with 5 waves over 10 years. Epidemiology and Health, e2022030. 10.4178/epih.e2022030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Center Research . (2021) Demographics of socialmedia users and adoption in the United States. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech, https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact‐sheet/social‐media/ [Google Scholar]

- R. E.A. & B. H. (2021) Emotions during the Covid‐19 pandemic: fear, anxiety, and anger as mediators between threats and policy support and political actions. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 51, 861–877, 10.1111/jasp.12806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas, J.‐P.F. (2020) Coronavirus: Lockdowns drive record growth in Twitter usage. Sky News. https://news.sky.com/story/coronavirus‐lockdowns‐drive‐record‐growth‐in‐twitter‐usage‐12034770 [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, E.B. , Hummert, M.L. & Boich, L.H. (1995) Communication predicaments of aging: patronizing behavior toward older adults. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 14(1–2), 144–166. 10.1177/0261927/95141008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salo, J. (2020) 102‐year‐old woman from Italy recovers from coronavirus. New York Post. https://nypost.com/2020/03/29/102‐year‐old‐woman‐from‐italy‐recovers‐from‐coronavirus/ [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, D.F. & Boland, S.M. (1986) Structure of perceptions of older adults: evidence for multiple stereotypes. Psychology and Aging, 1(3), 255–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnell, F. , Mcconatha, J.T. , Magnarelli, J. & Broussard, J. (2021) Ageism and perceptions of vulnerability: framing of age during the during the Covid‐19 pandemic. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 8(2), 170–177. 10.14738/assrj.82.9706 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seppala, E. , Simon‐Thomas, E. , Brown, S.L. , Worline, M.C. , Cameron, C.D. & Doty, J.R. (2017) The oxford handbook of compassion science. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sipocz, D. , Freeman, J.D. & Elton, J. (2021) A toxic trend?”: generational conflict and connectivity in twitter discourse under the #BoomerRemover Hashtag. The Gerontologist, 61(2), 166–175. 10.1093/geront/gnaa177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skipper, A.D. & Rose, D.J. (2021) #BoomerRemover: COVID‐19, ageism, and the intergenerational twitter response. Journal of Aging Studies, 57, 100929. 10.1016/j.jaging.2021.100929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan, L. (2017) Who tweets in the United Kingdom? Profiling the twitter population using the british social attitudes survey 2015. Social Media + Society, 3(1), 205630511769898. 10.1177/2056305117698981 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snow, D. & Benford, R. (1988) Ideology, frame resonance and participant mobilization. International Social Movement Research, 1, 197–217. [Google Scholar]

- Spaccatini, F. , Giovannelli, I. & Giuseppina Pacilli, M. (2022) You are stealing our present”: younger people's ageism towards older people affects attitude towards age‐based COVID‐19 restriction measures. Journal of Social Issues. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinert, S. (2020) Corona and value change. The role of social media and emotional contagion. Ethics and Information Technology, 23, 59–68. 10.1007/s10676-020-09545-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, J. (2020) Make the young socially distance, Boris Johnson is warned. Daily Mail Online. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article‐8586003/Make‐young‐socially‐distance‐locking‐50s‐Boris‐Johnson‐warned.html

- Sutter, A. , Vaswani, M. , Denice, P. , Choi, K.H. , Bouchard, J. & Esses, V. (2022) Ageism toward older adults during the COVID‐19 pandemic: intergenerationalconflict and support. Journal of Social Issues. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweetland, J. , Volmert, A. & O'Neil, M. (2017) Finding the frame: an empirical approach to reframing aging and ageism. FrameWorks Institute. https://www.frameworksinstitute.org/wp‐content/uploads/2020/05/aging_research_report_final_2017.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Swift, H.J. & Chasteen, A.L. (2021) Ageism in the time of COVID‐19. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 24(2), 246–252. 10.1177/1368430220983452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, M. (2020) How to support parents juggling kids and working remotely. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/maurathomas/2020/10/13/how‐to‐support‐parents‐juggling‐kids‐and‐working‐remotely/ [Google Scholar]

- Valdez, D. , Ten Thij, M. , Bathina, K. , Rutter, L.A. & Bollen, J. (2020) Social media insights into US mental health during the COVID‐19 pandemic: longitudinal analysis of twitter data. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(12), e21418. 10.2196/21418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vale, M.T. , Stanley, J.T. , Houston, M.L. , Villalba, A.A. & Turner, J.R. (2020) Ageism and behavior change during a health pandemic: a preregisteredstudy. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.587911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vervaecke, D. & Meisner, B.A. (2020) Caremongering and Assumptions of Need: The Spread of Compassionate Ageism During COVID‐19. The Gerontologist, gnaa131. 10.1093/geront/gnaa131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Woods, A. (2020) Grandma, 95, is oldest woman to recover from coronavirus in Italy. New York Post. https://nypost.com/2020/03/23/grandma‐95‐is‐oldest‐woman‐to‐recover‐from‐coronavirus‐in‐italy/ [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum. (2020) COVID and Longer Lives: Combating Ageism and Creating Solutions. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Combating_ageism_and_creating_solutions_2020.pdf

- World Health Organization . (2021a) Ageing and Life‐course. http://www.who.int/ageing/ageism/en/

- World Health Organization. (2021b) Global Report on Ageism. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/teams/social‐determinants‐of‐health/demographic‐change‐and‐healthy‐ageing/combatting‐ageism/global‐report‐on‐ageism [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, X. , Lu, X. , Halavanau, A. , Xue, J. , Sun, Y. , Lai, P.H.L. & Wu, Z. (2021) Modern Senicide in the Face of a Pandemic: An Examination of Public Discourse and Sentiment About Older Adults and COVID‐19 Using Machine Learning. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 76(4), e190–e200. 10.1093/geronb/gbaa128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Q. , Li, J. , Cai, M. & Mackey, T.K. (2019) Use of Machine Learning to Detect Wildlife Product Promotion and Sales on Twitter. Frontiers in Big Data, 2, 28. 10.3389/fdata.2019.00028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Yan, X. , Guo, J. , Lan, Y. & Cheng, X. (2013) A Biterm Topic Model for Short Texts. 1445–1456. 10.1145/2488388.2488514 [DOI]

- Zaveri, M. (2020) To Battle Isolation, Elders and Children Connect as Pen Pals. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/10/us/coronavirus‐seniors‐pen‐pals.html [Google Scholar]