Abstract

Background and purpose

Many single cases and small series of Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS) associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) infection were reported during the coronavirus disease 19 (COVID‐19) outbreak worldwide. However, the debate regarding the possible role of infection in causing GBS is still ongoing. This multicenter study aimed to evaluate epidemiological and clinical findings of GBS diagnosed during the COVID‐19 pandemic in northeastern Italy in order to further investigate the possible association between GBS and COVID‐19.

Methods

Guillain–Barré syndrome cases diagnosed in 14 referral hospitals from northern Italy between March 2020 and March 2021 were collected and divided into COVID‐19‐positive and COVID‐19‐negative. As a control population, GBS patients diagnosed in the same hospitals from January 2019 to February 2020 were considered.

Results

The estimated incidence of GBS in 2020 was 1.41 cases per 100,000 persons/year (95% confidence interval 1.18–1.68) versus 0.89 cases per 100,000 persons/year (95% confidence interval 0.71–1.11) in 2019. The cumulative incidence of GBS increased by 59% in the period March 2020–March 2021 and, most importantly, COVID‐19‐positive GBS patients represented about 50% of the total GBS cases with most of them occurring during the two first pandemic waves in spring and autumn 2020. COVID‐19‐negative GBS cases from March 2020 to March 2021 declined by 22% compared to February 2019–February 2020.

Conclusions

Other than showing an increase of GBS in northern Italy in the “COVID‐19 era” compared to the previous year, this study emphasizes how GBS cases related to COVID‐19 represent a significant part of the total, thus suggesting a relation between COVID‐19 and GBS.

Keywords: COVID‐19, GBS, Guillain–Barré syndrome

By showing an increase of Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS) cases during the first two pandemic waves of coronavirus disease 19 (COVID‐19) in northern Italy and emphasizing that COVID‐19‐positive GBS patients represent about 50% of the total GBS cases, this study supports a relation between COVID‐19 and GBS. Physicians should keep in mind GBS as a possible complication of COVID‐19 infection to make an early diagnosis and start an appropriate treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) first appeared in Italy at the end of February 2020 causing a first pandemic wave between March and May 2020 that mainly affected the regions of northern Italy. Subsequently, the cases of coronavirus disease 19 (COVID‐19) in Italy began to increase again from October 2020 causing a second and a third pandemic wave [1, 2].

The main manifestation of COVID‐19 is an interstitial pneumonia that can rapidly lead to respiratory failure [1]. However, following the understanding of the disease and the increase in the number of cases, many non‐pulmonary symptoms were recognized, including neurological complications such as acute cerebrovascular diseases, meningitis, encephalitis and specific neuromuscular manifestations including Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS) [3, 4, 5, 6].

In the early pandemic experience several patients with COVID‐19 and GBS have been described from all over the world suggesting a possible association [7, 8]. Our previous study found an increased incidence of GBS in northern Italy between March and April 2020 compared to the same period of 2019, providing evidence of a possible link between the COVID‐19 pandemic wave and GBS [9]. COVID‐19‐associated GBS was predominantly demyelinating and seemed to be more severe than non‐COVID‐19 GBS [9, 10]. Fragiel et al. described 11 cases of GBS diagnosed at the Emergency Department in Spain in the same period [11]. They found a statistically significant increase in the relative frequency and standardized incidence of GBS in COVID‐19 patients than in non‐COVID‐19 patients [11]. An increased risk of GBS (145 excess cases per 10 million exposed) in the 1–28 day period after a positive SARS‐CoV‐2 test was also observed [12].

Differently, Keddie et al. reported that in the UK the GBS incidence fell between March and May 2020 [13]. They studied a cohort of 47 GBS cases diagnosed in this period (COVID‐19 status: 13 definite, 12 probable, 22 non‐COVID‐19) and found that there were no significant differences in motor involvement, time to nadir, neurophysiological findings, cerebrospinal fluid findings and outcome compared to patients with GBS occurring during the same months of 2016–2019 [13].

Luijten et al. reported that between January and May 2020 there was no increase in patient recruitment for the ongoing International GBS Outcome Study compared to previous years [14]. However, they found that the prevalence of a preceding SARS‐CoV‐2 infection was higher than estimates of the contemporaneous background prevalence of SARS‐CoV‐2, possibly indicating that some of the cases followed a recent SARS‐CoV‐2 infection [14].

The debate emerging from the literature regarding the possible role of COVID‐19 in causing GBS is still ongoing. This multicenter study aimed at evaluating epidemiological and clinical findings of GBS diagnosed during the COVID‐19 pandemic in northern Italy over a long period in order to clarify this topic.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

Between January 2019 and March 2021, patients with GBS diagnosed in 14 referral hospitals of eight provinces from northern Italy were enrolled. Clinical data were retrospectively collected in the January 2019–April 2020 period and prospectively in the next months.

Inclusion criteria were age >18 years and GBS diagnosed according to clinical findings and the Brighton Collaboration GBS Working Group criteria [15, 16]. SARS‐CoV‐2 polymerase chain reaction based detection using nasopharyngeal swab specimens or anti‐nucleocapsid SARS‐CoV‐2 antibodies were obtained in all the patients at admission (Table 1). The exclusion criterion was a diagnosis of GBS‐mimicking conditions including critical illness myopathy and/or neuropathy and other nerve and/or muscle acute diseases that can be misdiagnosed as GBS.

TABLE 1.

COVID‐19‐related findings in the 63 patients with COVID‐19 and GBS

| Clinical findings (patients, n = 63) | % (patients, n) |

|---|---|

| Nasopharyngeal swab positivity | 93.7% (59) |

| Anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 positivity | 6.3% (4) |

| Interstitial pneumonia on chest X‐ray or chest computed tomography | 96.8% (61) |

| COVID symptoms |

Fever 84.1% (53) Cough 79.4% (50) Dyspnea 68.3% (43) Dysgeusia 31.7% (20) Anosmia 30.2% (19) Gastrointestinal symptoms 19.0% (12) Asymptomatic 1.6% (1) |

| PaO2 at hospitalization (mean ± SD) | 57.12 ± 25.3 mmHg |

| Oxygen therapy | 84.1% (53) |

| Non‐invasive ventilation | 52.4% (33) |

| Invasive ventilation | 27% (17) |

| COVID therapy |

Antibiotic therapy 84.1% (53) Prophylactic dose heparin therapy 68.3% (43) Steroid therapy 58.7% (37) Hydroxychloroquine 41.3% (26) Antiviral therapy 27% (17) Heparin with an anticoagulant dosage 23.8% (15) Tocilizumab 11.1% (7) |

| Admission to ICU | 49.2% (31) |

| Mean ICU hospitalization duration | 26.42 ± 11.34 days |

| SOFA score at hospitalization (mean ± SD) | 3.87 ± 3.68 |

| SOFA score at discharge (mean ± SD) | 2.69 ± 2.63 |

| Interval from onset of COVID‐19 symptoms and GBS symptoms (mean ± SD) | 18.02 ± 12.01 days |

Abbreviations: COVID, coronavirus disease; GBS, Guillain–Barré syndrome; ICU, intensive care unit; SOFA, sequential organ failure assessment score.

Clinical scales

The Medical Research Council (MRC) sum score was used to evaluate muscle strength in 12 muscle groups. It ranges from 0 to 60 with higher scores indicating more preserved strength.

Disability was measured by the Hughes scale according to the following scores: 0, a healthy state; 1, minor symptoms and capable of running; 2, able to walk 10 m or more without assistance but unable to run; 3, able to walk 10 m across an open space with help; 4, bedridden or chair bound; 5, requiring assisted ventilation for at least part of the day; 6, dead [17].

Electrophysiological studies and electrodiagnostic criteria

Nerve conduction studies were performed according to standardized techniques [10, 18, 19, 20]. In the median, ulnar, peroneal and tibial motor nerves distal motor latency, amplitude and duration of the negative peak of the compound muscle action potential (CMAP) from different stimulation sites, motor conduction velocity and minimal F‐wave latency were measured. The cut‐off values for the distal CMAP duration were determined according to normal values for the low frequency filter used +2 SD [10]. Proximal/distal CMAP amplitude and duration ratios were also assessed. Sensory studies were performed antidromically in the median, ulnar and sural nerves and the amplitude of the sensory nerve action potential was measured from baseline to negative peak. Electrophysiological findings were normalized as percentages of upper and lower limits of normal according to reference values of each center. For the electrodiagnosis of GBS subtypes a criterion set was used that showed the highest diagnostic accuracy at first electrophysiological study in a cohort with a balanced number of acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (AIDP) and axonal GBS patients and that was also employed in previous studies [10, 18, 20].

Statistical analysis

The analysis was performed using version 24.0 of the IBM SPSS software. Continuous variables were expressed as median value and/or mean ± SD when appropriate. Categorical variables were shown as frequencies and percentages. Statistical analyses were performed with parametrical tests (chi‐squared test or t of the Student test). The statistical threshold was set at 0.05.

The annual incident risk was calculated by putting in the numerator the number of GBS cases recorded during the observation period and in the denominator the number of people at risk of getting sick, taking into account the number of the general population in the provinces according to the 2019 ISTAT (National Institute of Statistics) official data. The total of the population thus calculated was 8,632,708. Relative incidence was derived from comparing the 2019 and 2020 GBS populations.

For the purpose of our study, the 13 months following the beginning of the pandemic in Italy (March 2020–March 2021), the so‐called “COVID‐19 era”, was also compared with the previous 13 months (February 2019–February 2020).

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethical committee and informed consent

This study has been approved by Brescia Ethical Committee. Given the difficulty in systematically obtaining informed consent and given the great public interest of the project, the research was conducted in the context of the authorizations guaranteed by Article 89 of the GDPR EU Regulation 2016/679.

RESULTS

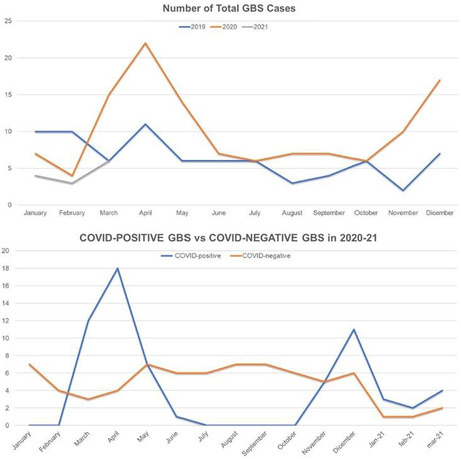

A total of 212 patients with GBS were diagnosed between 1 January 2019 and 31 March 2021. Seventy‐seven patients were diagnosed in 2019, 122 in 2020 and 13 between January and March 2021. The temporal distribution of the diagnoses is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Total diagnoses of GBS divided month by month in 2019, 2020 and 2021. A peak of cases is coincident with the first pandemic wave during spring 2020 and with the second wave in autumn 2020.

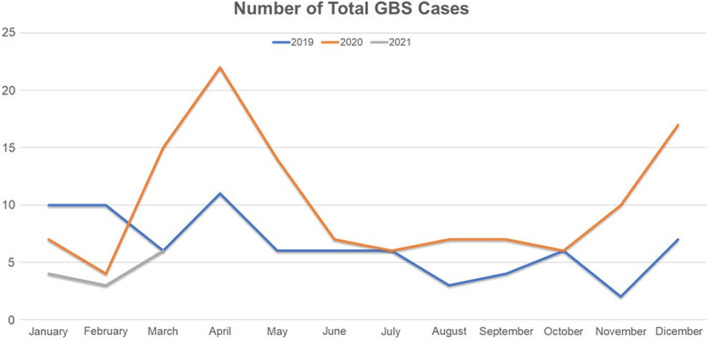

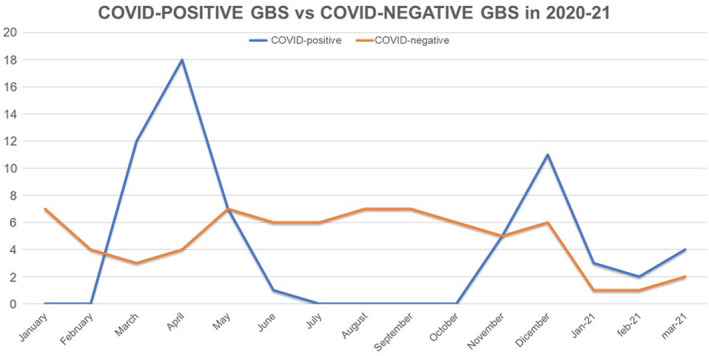

In the COVID‐19 era (March 2020–March 2021), 63 patients with confirmed SARS‐CoV‐2 and labeled as COVID‐19‐positive GBS and 61 COVID‐19‐negative GBS subjects were diagnosed (Figure 2). A total of 78 GBS patients were diagnosed in the same centers in the previous 13 months (between February 2019 and February 2020).

FIGURE 2.

COVID‐19‐positive and COVID‐19‐negative patients divided month by month diagnosed between March 2020 and March 2021. GBS‐COVID‐19‐positive cases are significantly prevalent in correspondence with the first pandemic wave during spring 2020 and with the second wave in autumn 2020.

GBS incidence

The annual incidence of GBS in 2020 in the provinces of Lombardy, Veneto and Friuli Venezia Giulia involved in this study was 1.41 cases per 100,000 persons/year (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.18–1.68). In 2019 the annual incidence in the same regions was 0.89 cases per 100,000 persons/year (95% CI 0.71–1.11). The relative incidence of GBS in 2020 compared with 2019 was 1.58. In 2020, 50.8% of the total GBS were COVID‐19‐positive whilst 49.2% were COVID‐negative.

When the period between March 2020 and March 2021 is compared with the previous 13 months (February 2019–February 2020) total GBS cases rose by 59% (n = 46) in the COVID‐19 era, whilst COVID‐19‐negative GBS dropped by 22% (n = 17).

Figure 2 shows a higher number of COVID‐19‐positive GBS during spring 2020 and between November and December 2020 concurrently with the first two pandemic waves in Italy.

Clinical features of GBS cases

Clinical and electrophysiological features of 2020–2021 COVID‐19‐positive and COVID‐19‐negative GBS patients are reported in Table 2. The COVID‐19‐related clinical, radiological and laboratory findings of COVID‐19‐positive GBS patients are reported in Table 1.

TABLE 2.

Demographic, clinical features, electrodiagnosis and laboratory findings of COVID‐19‐positive GBS patients versus total COVID‐19‐negative patients

| 2020–2021 COVID‐19‐positive GBS (63), % (no.) | COVID‐19‐negative GBS (149), % (no.) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 74.6 (47) male | 62.4 (93) male | 0.11 |

| 25.4 (16) female | 37.6 (56) female | ||

| Age | 63.30 ± 14.45 years (range 24–94) | 58.17 ± 17.52 years (range 18–85) | 0.08 |

| Neurological findings | |||

| Consciousness | Alert 73 (46) | Alert 95.3 (142) | <0.001* |

| Unresponsive 14.3 (9) | Unresponsive 1.3 (2) | <0.001* | |

| Delirium 12.7 (8) | Delirium 3.4 (5) | <0.001* | |

| MRC sum score | 34.7 ± 17.6 | 47.71 ± 12.14 | <0.001* |

| Motor impairment | Upper proximal weakness 61.9 (39) | Upper proximal weakness 38.3(57) | 0.001* |

| Upper distal weakness 66.7 (42) | Upper distal weakness 58.4(87) | 0.41 | |

| Upper limb asymmetry 14.3 (9) | Upper limb asymmetry 13.4 (20) | 0.83 | |

| Lower proximal weakness 85.7 (54) | Lower proximal weakness 67.8 (101) | 0.007* | |

| Lower distal weakness 90.5 (57) | Lower distal weakness 79.2 (118) | 0.05 | |

| Lower limb asymmetry 19 (12) | Lower limb asymmetry 20.8 (31) | 0.85 | |

| Sensory impairment | Upper limb hypoesthesia 28.5 (18) | Upper limb hypoesthesia 28.8 (43) | 0.73 |

| Lower limb hypoesthesia 49.2 (31) | Lower limb hypoesthesia 46.3 (69) | 0.86 | |

| Upper limb paresthesia 36.5 (23) | Upper limb paresthesia 53(79) | 0.20 | |

| Lower limb paresthesia 46 (29) | Lower limb paresthesia 61.7 (92) | 0.26 | |

| Pain 27.4 (17) | Pain 30.2 (45) | 0.37 | |

| Hypo/areflexia | 98.4 (62) | 95.3 (142) | 0.32 |

| Cranial neuropathies | |||

| Olfactory | 31.7 (20) | 0.7 (1) | <0.001* |

| Oculomotor nerves | 12.7 (8) | 16.1 (24) | 0.67 |

| Facial nerve | Unilateral 25.4 (16) | Unilateral 15.4 (23) | 0.41 |

| Bilateral 11.1 (7) | Bilateral 12.1 (18) | 0.92 | |

| Bulbar nerves | 20.6 (13) | 9.4 (14) | 0.12 |

| Dysautonomia | |||

| Blood pressure | Normal 46 (29) | Normal 81.8 (122) | 0.001* |

| Hypotension 46 (29) | Hypotension 16.8 (25) | 0.001* | |

| Hypertension 8 (5) | Hypertension 1.3 (2) | 0.002* | |

| Heart rate | Normal 76.2 (48) | Normal 93.4 (140) | 0.001* |

| Tachycardia/bradycardia 23.8 (15) | Tachycardia/bradycardia 6.6 (9) | 0.001* | |

| Clinical diagnosis | Classical GBS 88.8 (56) | Classical GBS 85.9 (128) | 0.11 |

| Miller Fisher syndrome 3.2 (2) | Miller Fisher syndrome 10.8 (16) | ||

| Facial diplegia 1.6 (1) | Facial diplegia 1.3 (2) | ||

| Pure sensory form 1.6 (1) | Pure sensory form 0.7 (1) | ||

| Pure motor form 1.6 (1) | Pure motor form 0 (0) | ||

| Pharyngeal‐cervical‐brachial 3.2 (2) | Pharyngeal‐cervical‐brachial 1.3 (2) | ||

| Electrodiagnosis | AIDP 76.2 (48) | AIDP 49.6 (74) | 0.018* |

| AMAN 7.9 (5) | AMAN 15.4 (23) | ||

| AMSAN 4.8 (3) | AMSAN 6 (9) | ||

| Equivocal 9.5 (6) | Equivocal 22.2 (33) | ||

| Normal 1.6 (1) | Normal 6.8 (10) | ||

| CSF findings | Increased proteins/normal cells 61.2 (32) | Increased proteins/normal cells 61.1 (69) | 0.99 |

| Normal 38.8 (19) | Normal 38.2 (44) | ||

| Brighton criteria | Level 1, 42.9 (27) | Level 1, 46.3 (69) | 0.15 |

| Level 2, 55.6 (35) | Level 2, 49.7 (74) | ||

| Not classifiable 1.6 (1) | Level 3, 4 (6) | ||

| Hughes disability score during hospitalization | 3.76 ± 1.13 | 3.03 ± 1.12 | <0.001* |

| Hughes disability score at discharge | 3.15 ± 1.27 | 2.19 ± 1.29 | <0.001* |

| ICU admission | 49.2 (31) | 14.7 (22) | <0.001* |

| Comorbidities | Obesity 25.4 (16) | Obesity 22.1 (33) | 0.06 |

| Neoplasms 7.9 (5) | Neoplasms 8.7 (13) | 0.52 | |

| Pulmonary disease 9.5 (6) | Pulmonary disease 6.0 (9) | 0.28 | |

| Diabetes 23.8 (15) | Diabetes 14.8 (22) | 0.16 | |

| Hypertension 46 (29) | Hypertension 39.6 (59) | 0.76 | |

| Cardiovascular disease 23.8 (15) | Cardiovascular disease 12.8 (19) | 0.09 | |

| Plasma exchange | 4.8 (3) | 6.0 (9) | 0.99 |

| IVIGs | 85.7 (54) | 91.3 (136) | 0.05 |

| No treatment | 9.6 (6) | 2.6 (4) | 0.12 |

| Response to treatment | Yes 77.8 (49) | Yes 86.5 (129) | 0.25 |

Abbreviations: AIDP, acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy; AMAN, acute motor axonal neuropathy; AMSAN, acute motor and sensory axonal neuropathy; COVID, coronavirus disease; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; GBS, Guillain–Barré syndrome; ICU, intensive care unit; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; MRC, Medical Research Council.

Bold values and * indicate statistically significant (< 0.05).

Briefly, GBS clinical presentation in COVID‐19‐positive patients was the classical form in 88.8% of the patients. Two patients had Miller Fisher syndrome, one had a pure motor form, one a pure sensory form and two patients the pharyngeal‐cervical‐brachial variant. The electrodiagnosis showed a prevalence of AIDP subtype (76.2%). Acute motor axonal neuropathy represented 7.9% of patients and acute motor and sensory axonal neuropathy 4.8%. An equivocal result was observed in 9.5% of patients who could not be more precisely classified.

The mean Hughes value during hospitalization was 3.76 ± 1.13 and at discharge was 3.15 ± 1.27 with an average improvement of 0.59 point. The majority of patients (85.7%) received intravenous immunoglobulins. Three patients were treated with plasma exchange and six patients received no treatment. The overall rate of response was 77.8%.

Fifty‐nine patients were diagnosed with COVID‐19 by a nasopharyngeal positive swab whilst four had positive anti‐nucleocapsid SARS‐CoV‐2 antibodies. All patients but one showed some COVID‐19‐related symptoms, that is, fever (84.1%), cough (79.4%), dyspnea (68.3%), olfactory dysfunction (31.7%), dysgeusia (30.2%), gastrointestinal symptoms (19%). The majority of patients (96.8%) showed some degree of interstitial pneumonia on chest X‐ray or chest computed tomography scan. The mean interval from COVID‐19 symptom onset and GBS symptoms was 18.02 ± 12.01 days.

The COVID‐19‐positive and COVID‐19‐negative populations showed no differences in sex distribution, medium age and comorbidities.

When comparing COVID‐19‐positive and COVID‐19‐negative GBS patients, the first group showed a higher rate of consciousness alteration with more patients being unresponsive (14.3% vs. 1.3%) or with delirium (12.7% vs. 3.4%) (p < 0.001). COVID‐19‐positive patients had a lower MRC sum score (34.7 ± 17.6 vs. 47.71 ± 12.14, p < 0.001) and more frequent upper and lower limb proximal weakness.

Hyposmia was less present in COVID‐19‐negative patients (0.7% vs. 31.7%, p < 0.001) whilst dysautonomic symptoms were more frequently detected in COVID‐19‐positive GBS patients. The two groups showed no differences in GBS clinical presentation, whilst in terms of electrodiagnosis AIDP was more frequent in COVID‐19‐positive GBS patients (76.2% vs. 49.6%, p = 0.018). COVID‐19‐positive patients had a more severe disability measured with Hughes score both at peak (3.76 ± 1.13 vs. 3.03 ± 1.12, p < 0.001) and at discharge (3.15 ± 1.27 vs. 2.15 ± 1.29, p < 0.001) with a more frequent admission in the intensive care unit (49.2% vs. 14.7%, p < 0.001). There were no differences in terms of response to therapy between the two groups.

A statistical comparison between 2020–2021 COVID‐19‐positive, 2020–2021 COVID‐19‐negative and 2019 GBS patients showed results similar to those obtained by comparing 2020–2021 COVID‐19‐positive and total COVID‐19‐negative GBS patients.

DISCUSSION

The incidence of GBS in the general population in Europe and North America was found to be between 0.84 and 1.8 cases per 100,000 people per year [21, 22, 23]. Lower values were found in the pediatric population whilst the rate increased up to 3.3/100,000/year in the population over the age of 50 years [21, 24]. In Italy, previous studies found an annual incidence of GBS of 1.11/100,000/year in the Emilia Romagna region and 1.28/100,000/year in the Piedmont and Valle d'Aosta regions [25, 26]. In the Lombardy region an incidence of between 0.92 and 1.43/100,000/year was reported [27, 28].

For the COVID‐19 era, GBS incidence in Italy was evaluated in our previous study [9]. Based on the data from March and April 2020, a GBS incidence of 0.202 per 100,000 per month in 2020 (95% CI 0.140–0.282) was calculated with an estimated annual incidence of 2.43/100,000/year, whilst in 2019 the GBS incidence was 0.077 per 100,000 per month (95% CI 0.041–0.132) with an estimated annual rate of 0.93/100,000/year [9]. In Friuli‐Venezia Giulia, the monthly GBS incidence during March and April 2020 was 0.65 cases/100,000 compared to 0.12 cases/100,000 in the same period of the previous years, meaning a 5.41‐fold incidence increase [29].

On the other hand, no increase in patient recruitment in the International GBS Outcome Study between January and May 2020 compared to previous years was reported and a decrease in GBS cases between March and May 2020 compared to the number of cases observed in the same months of the previous 5‐year period was found in a UK cohort [13, 14]. However, more recently Patone et al. found contrasting robust and real data‐based results in a wide UK population by demonstrating an increase in GBS cases after SARS‐CoV‐2 test positivity [12].

Our present study conducted in main referral centers of three regions from northern Italy showed a statistically significant increase in the incidence of GBS in 2020 compared to 2019 with a relative incidence of 1.58. Although both the currently reported 2020 (1.41/100,000/year) and 2019 (0.89/100,000/year) incidences fall within the expected range from previous non‐COVID‐19 studies in Lombardy (0.92–1.43/100,000/year) [27, 28], our data show that more than half of the total GBS cases diagnosed in the COVID‐19 era were COVID‐19‐positive whilst COVID‐19‐negative GBS cases dropped by 22% compared to the previous year. Moreover, the month‐by‐month distribution of cases shows a peak of GBS cases coinciding with the first wave in spring 2020 and the second wave in autumn 2020 (Figure 1) and emphasizes that GBS‐COVID‐19‐positive cases are significantly prevalent in the two pandemic waves (Figure 2), further supporting an association between COVID‐19 and GBS in Italy.

The decrease in COVID‐19‐negative GBS cases observed in 2020 could be related to the implementation of personal hygiene measures which might have reduced the incidence of GBS linked to other infectious agents. Similarly, social distancing, hygiene measures and use of face masks could explain the decrease in total cases in the first months of 2021 (Figures 1 and 2) compared to the previous years since these precautions have also significantly reduced the cases of seasonal flu [30, 31, 32, 33, 34].

Although a role for direct neuro‐invasion binding to gangliosides through spike protein and/or cytokine storm has been proposed, underlying pathogenic mechanisms as well as whether the different beta, gamma, delta, omicron SARS‐CoV‐2 variants have a different ability to trigger GBS remains to be elucidated [35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44]. Similarly, it is unclear why differences in triggering GBS between various regions have been reported [9, 11, 13, 14, 34].

Closely related to the pathogenetic issue, whether COVID‐19‐related GBS is a post‐infectious or a para‐infectious disease is still debated [9, 45]. In our series, the mean interval from onset of COVID‐19 and GBS symptoms was 18.02 days. Only 20% of patients showed a clear post‐infectious course of disease, whilst in 80% of patients GBS symptoms developed whilst COVID‐19 symptoms were still ongoing. However, it was not possible to establish whether the latter group of patients have a “true” para‐infectious disease because of the persistence of respiratory symptoms and chest computed tomography scan abnormalities in the post‐viremic hyperinflammatory phase, meaning beyond the viremic early infection and pulmonary phases [46, 47, 48].

Regarding clinical findings, our data do not differ from those previously reported [9]. Compared with non‐COVID‐19‐related GBS, the COVID‐19‐related disease is predominantly an AIDP and it is usually more severe with a lower mean MCR score, a higher Hughes score, more frequent autonomic dysfunction and more frequent intensive care unit admission. As previously reported, no statistically significant differences in the response rate to therapy between COVID‐19‐related and non‐related GBS have been found in the present study [9].

Interestingly, COVID‐19‐positive GBS patients mainly present with a symptomatic SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, since almost all the patients had lung involvement with signs of interstitial pneumonia and needed oxygen therapy, suggesting that GBS mainly develops following moderate or severe COVID‐19 infections and seems less likely in asymptomatic or paucisymptomatic forms.

The current study has some limitations. First, data regarding GBS patients between January 2019 and February 2020 were retrospectively collected and some cases may have been missed.

Secondly, although our study includes main reference centers for acute neurological diseases in northeastern Italy, it is likely that additional patients with GBS may have been admitted to other hospitals, thus leading to an underestimation of the global incidence of GBS. However, the incidence of GBS calculated in 2019 is comparable to that previously reported in the north of Italy and the selection bias is identical for data collected both in the pre‐pandemic period and the COVID‐19 era, so that the difference in the observed rates between 2019 and 2020 remains valid.

Despite these limitations, to our knowledge this is the study with the largest cohort of COVID‐19‐positive patients who have developed GBS and with the longest observation period. Our results confirm an increase in GBS cases in the COVID‐19 era compared to the previous year in northeast Italy and highlights how GBS cases related to COVID‐19 represent a significant part of the total, thus suggesting a relation between COVID‐19 and GBS.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Massimiliano Filosto: Conceptualization (lead); data curation (lead); formal analysis (lead); investigation (lead); methodology (lead); supervision (lead); writing – original draft (lead); writing – review and editing (lead). Stefano Cotti Piccinelli: Data curation (lead); formal analysis (lead); investigation (lead); methodology (lead); validation (equal); writing – original draft (lead). Stefano Gazzina: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); methodology (equal). Camillo Foresti: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Barbara Frigeni: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Maria Cristina Servalli: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Maria Sessa: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Giuseppe Cosentino: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Enrico Marchioni: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Sabrina Ravaglia: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Chiara Briani: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Francesca Castellani: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Gabriella Zara: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Francesca Bianchi: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Ubaldo Del Carro: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Raffaella Fazio: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Massimo Filippi: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Eugenio Magni: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Giuseppe Natalini: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Francesco Palmerini: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Anna Maria Perotti: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Andrea Bellomo: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Maurizio Osio: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Caterina Nascimbene: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Marinella Carpo: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Andrea Rasera: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Giovanna Squintani: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Pietro Doneddu: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Valeria Bertasi: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Maria Sofia Cotelli: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Laura Bertolasi: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Gian Maria Fabrizi: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Sergio Ferrari: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Federico Ranieri: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Francesca Caprioli: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Elena Grappa: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Paolo Manganotti: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Giulia Bellavita: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Giovanni Furlanis: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Giovanni De Maria: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Ugo Leggio: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Loris Poli: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Frank Rasulo: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Nicola Latronico: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal). Eduardo Nobile‐Orazio: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); resources (equal); validation (equal). Ettore Beghi: Formal analysis (equal); methodology (equal); validation (equal). Alessandro Padovani: Conceptualization (equal); methodology (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Antonino Uncini: Conceptualization (equal); data curation (equal); methodology (equal); supervision (equal); validation (equal); writing – review and editing (equal).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Nothing to report.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

MF, SCP, AP, CB are members of HCPs part of the European Reference Network for Neuromuscular Diseases. The authors thank Dr Elisabetta Pupillo for critically reading the manuscript. Open Access Funding provided by Universita degli Studi di Brescia within the CRUI‐CARE Agreement.

Filosto M, Cotti Piccinelli S, Gazzina S, et al. Guillain‐Barré syndrome and COVID‐19: A 1‐year observational multicenter study. Eur J Neurol. 2022;00:1‐10. doi: 10.1111/ene.15497

Massimiliano Filosto and Stefano Cotti Piccinelli contributed equally to this paper.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708‐1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. COVID‐19 integrated surveillance data in Italy, Epicentro‐Epidemiology for Public Health Istituto Superiore di Sanità. Accessed December 15, 2021. https://www.epicentro.iss.it/en/coronavirus/sars‐cov‐2‐dashboard

- 3. Harapan BN, Yoo HJ. Neurological symptoms, manifestations, and complications associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) and coronavirus disease 19 (COVID‐19). J Neurol. 2021;268:3059‐3071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carod‐Artal FJ. Neurological complications of coronavirus and COVID‐19. Rev Neurol. 2020;70:311‐322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Benussi A, Pilotto A, Premi E, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of inpatients with neurologic disease and COVID‐19 in Brescia, Lombardy, Italy. Neurology. 2020;95:e910‐e920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Guidon AC, Amato AA. COVID‐19 and neuromuscular disorders. Neurology. 2020;94:959‐969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Caress JB, Castoro RJ, Simmons Z, et al. COVID‐19‐associated Guillain–Barré syndrome: the early pandemic experience. Muscle Nerve. 2020;62:485‐491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Abu‐Rumeileh S, Abdelhak A, Foschi M, Tumani H, Otto M. Guillain–Barré syndrome spectrum associated with COVID‐19: an up‐to‐date systematic review of 73 cases. J Neurol. 2021;268:1133‐1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Filosto M, Cotti Piccinelli S, Gazzina S, et al. Guillain–Barré syndrome and COVID‐19: an observational multicentre study from two Italian hotspot regions. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2021;92:751‐756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Uncini A, Foresti C, Frigeni B, et al. Electrophysiological features of acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy associated with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Neurophysiol Clin. 2021;51:183‐191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fragiel M, Miró Ò, Llorens P, et al. Incidence, clinical, risk factors and outcomes of Guillain–Barré in COVID‐19. Ann Neurol. 2020;89:598‐603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Patone M, Handunnetthi L, Saatci D, et al. Neurological complications after first dose of COVID‐19 vaccines and SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Nat Med. 2021;27:2144‐2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Keddie S, Pakpoor J, Mousele C, et al. Epidemiological and cohort study finds no association between COVID‐19 and Guillain–Barré syndrome. Brain. 2021;144:682‐693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Luijten LWG, Leonhard SE, van der Eijk AA, et al. Guillain–Barré syndrome after SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in an international prospective cohort study. Brain. 2021;144:3392‐3404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sejvar JJ, Kohl KS, Gidudu J, et al. Guillain–Barré syndrome and Fisher syndrome: case definitions and guidelines for collection, analysis, and presentation of immunization safety data. Vaccine. 2011;29:599‐612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wakerley B, Uncini A. Yuki N and the GBS classification group. Guillain–Barré and Miller Fisher syndrome—new diagnostic classification. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10:537‐544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. van Koningsveld R, Steyerberg EW, Hughes RAC, Swan AV, van Doorn PA, Jacobs BC. A clinical prognostic scoring system for Guillain–Barré syndrome. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:589‐594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Uncini A, Ippoliti L, Shahrizaila N, Sekiguchi Y, Kuwabara S. Optimizing the electrodiagnostic accuracy in Guillain–Barré syndrome subtypes: criteria sets and sparse linear discriminant analysis. Clin Neurophysiol. 2017;128:1176‐1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Uncini A, Kuwabara S. The electrodiagnosis of Guillain–Barré syndrome subtypes: where do we stand? Clin Neurophysiol. 2018;29:2586‐2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Uncini A, González‐Bravo DC, Acosta‐Ampudia YY, et al. Clinical and nerve conduction features in Guillain–Barré syndrome associated with zika virus infection in Cúcuta, Colombia. Eur J Neurol. 2018;25:644‐650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McGrogan A, Madle GC, Seaman HE, de Vries CS. The epidemiology of Guillain–Barré syndrome worldwide. A systematic literature review. Neuroepidemiology. 2009;32:150‐163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kinnunen E, Junttila O, Haukka J, Hovi T. Nationwide oral poliovirus vaccination campaign and the incidence of Guillain–Barré syndrome. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147:69‐73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Alshekhlee A, Hussain Z, Sultan B, Katirji B. Guillain–Barré syndrome: incidence and mortality rates in US hospitals. Neurology. 2008;70:1608‐1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rantala H, Cherry JD, Shields WD, Uhari M. Epidemiology of Guillain–Barré syndrome in children: relationship of oral polio vaccine administration to occurrence. J Pediatr. 1994;124:220‐223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Emilia‐Romagna study group on clinical and epidemiological problems in neurology a prospective study on the incidence and prognosis of Guillain–Barré syndrome in Emilia‐Romagna region, Italy (1992–1993). Neurology. 1997;48:214‐221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chio A, Cocito D, Leone M, et al. Guillain–Barré syndrome: a prospective, population‐based incidence and outcome survey. Neurology. 2003;60:1146‐1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Beghi E, Bogliun G. The Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS): implementation of a register of the disease on a nationwide basis. Ital J Neurol Sci. 1996;17:355‐361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bogliun G, Beghi E, Italian GBS Registry Study Group . Incidence and clinical features of acute inflammatory polyradiculoneuropathy in Lombardy, Italy, 1996. Acta Neurol Scand. 2004;110:100‐106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gigli GL, Bax F, Marini A. Guillain–Barré syndrome in the COVID‐19 era: just an occasional cluster? J Neurol. 2021;268:1195‐1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control . Seasonal influenza—Annual Epidemiological Report for 2020–2021. Accessed December 15, 2021. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications‐data/seasonal‐influenza‐annual‐epidemiological‐report‐2020‐2021

- 31. Lehmann HC, Hartung HP, Kieseier BC, Hughes RAC. Guillain–Barré syndrome after exposure to influenza virus. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:643‐651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. van den Berg B, Walgaard C, Drenthen J, Fokke C, Jacobs BC, van Doorn PA. Guillain–Barré syndrome: pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10:469‐482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Orlikowski D, Porcher R, Sivadon‐Tardy V, et al. Guillain–Barré syndrome following primary cytomegalovirus infection: a prospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:837‐844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Umapathi T, Er B, Koh JS, Goh YH, Chua L. Guillain–Barré syndrome decreases in Singapore during the COVID‐19 pandemic. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2021;26:235‐236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fantini J, Di Scala C, Chahinian H, et al. Structural and molecular modelling studies reveal a new mechanism of action of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine against SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;55:105960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Song E, Zhang C, Israelow B, et al. Neuroinvasion of SARS‐CoV‐2 in human and mouse brain. J Exp Med. 2021;218:e20202135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mohammadi S, Moosaie F, Aarabi MH. Understanding the immunologic characteristics of neurologic manifestations of SARS‐CoV‐2 and potential immunological mechanisms. Mol Neurobiol. 2020;57:5263‐5275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rabi FA, Al Zoubi MS, Al‐Nasser AD, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 and coronavirus disease 2019: what we know so far. Pathogens. 2020;9:231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Destras G, Bal A, Escuret V, et al. Systematic SARS‐CoV‐2 screening in cerebrospinal fluid during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Lancet Microbe. 2020;1:e149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Khan F, Sharma P, Pandey S, et al. COVID‐19‐associated Guillain–Barré syndrome: postinfectious alone or neuroinvasive too? J Med Virol. 2021;93:6045‐6049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Viszlayová D, Sojka M, Dobrodenková S, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA in the cerebrospinal fluid of a patient with long COVID. Ther Adv Infect Dis. 2021;8:20499361211048572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Freire M, Andrade A, Sopeña B, et al. Guillain–Barré syndrome associated with COVID‐19 lessons learned about its pathogenesis during the first year of the pandemic, a systematic review. Autoimmun Rev. 2021;20:102875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Manson JJ, Crooks C, Naja M, et al. COVID‐19‐associated hyperinflammation and escalation of patient care: a retrospective longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;2:e594‐e602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hussain FS, Eldeeb MA, Blackmore D, et al. Guillain–Barré syndrome and COVID‐19: possible role of the cytokine storm. Autoimmun Rev. 2020;19:102681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Manganotti P, Bellavita G, D'Acunto L, et al. Clinical neurophysiology and cerebrospinal liquor analysis to detect Guillain–Barré syndrome and polyneuritis cranialis in COVID‐19 patients: a case series. J Med Virol. 2021;93:766‐774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Uncini A, Vallat J‐M, Jacobs BC. Guillain–Barré syndrome in SARS‐CoV‐2 infection: an instant systematic review of the first six months of pandemic. J Neurol Neurosurg. 2020;91:1105‐1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lauer SA, Grantz KH, Bi Q, et al. The incubation period of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) from publicly reported confirmed cases: estimation and application. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:577‐582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Siddiqi HK, Mehra MR. COVID‐19 illness in native and immunosuppressed states: a clinical‐therapeutic staging proposal. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020;39:405‐407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.