Abstract

Many gram-negative bacteria communicate by N-acyl homoserine lactone signals called autoinducers (AIs). In Pseudomonas aeruginosa, cell-to-cell signaling controls expression of extracellular virulence factors, the type II secretion apparatus, a stationary-phase sigma factor (ςs), and biofilm differentiation. The fact that a similar signal, N-(3-oxohexanoyl) homoserine lactone, freely diffuses through Vibrio fischeri and Escherichia coli cells has led to the assumption that all AIs are freely diffusible. In this work, transport of the two P. aeruginosa AIs, N-(3-oxododecanoyl) homoserine lactone (3OC12-HSL) (formerly called PAI-1) and N-butyryl homoserine lactone (C4-HSL) (formerly called PAI-2), was studied by using tritium-labeled signals. When [3H]C4-HSL was added to cell suspensions of P. aeruginosa, the cellular concentration reached a steady state in less than 30 s and was nearly equal to the external concentration, as expected for a freely diffusible compound. In contrast, [3H]3OC12-HSL required about 5 min to reach a steady state, and the cellular concentration was 3 times higher than the external level. Addition of inhibitors of the cytoplasmic membrane proton gradient, such as azide, led to a strong increase in cellular accumulation of [3H]3OC12-HSL, suggesting the involvement of active efflux. A defined mutant lacking the mexA-mexB-oprM-encoded active-efflux pump accumulated [3H]3OC12-HSL to levels similar to those in the azide-treated wild-type cells. Efflux experiments confirmed these observations. Our results show that in contrast to the case for C4-HSL, P. aeruginosa cells are not freely permeable to 3OC12-HSL. Instead, the mexA-mexB-oprM-encoded efflux pump is involved in active efflux of 3OC12-HSL. Apparently the length and/or degree of substitution of the N-acyl side chain determines whether an AI is freely diffusible or is subject to active efflux by P. aeruginosa.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa remains a leading cause of both nosocomial infections in immunocompromised patients and chronic infections in cystic fibrosis patients (reviewed in references 9 and 57). P. aeruginosa virulence depends on cell-associated factors, including alginate and pili (5, 9), and secreted factors, including toxins, exotoxin A, and exoenzyme S (14, 28); proteases, elastase, alkaline protease, and LasA protease (13, 27, 47); and hemolysins, rhamnolipid, and phospholipase (25). Cell-to-cell signaling (quorum sensing) is required for expression of many P. aeruginosa virulence factors (see below) (6, 43).

Intrinsic resistance of P. aeruginosa to many antibiotics and disinfectants also causes clinical problems (49). The intrinsic resistance is due to low outer membrane permeability and to multidrug efflux pumps that reduce the cellular level of antibiotics (reviewed in references 11 and 30). Three known P. aeruginosa multidrug efflux pumps are encoded by the mexAB-oprM, mexCD-oprJ, and mexEF-oprN operons, respectively (18, 45, 46). These pumps consist of a cytoplasmic membrane component of the resistance-nodulation-cell division (RND) family (39) thought to function as a proton antiport exporter (i.e., MexB), an outer membrane component thought to form channels (i.e., OprM), and a membrane fusion protein thought to link MexB and OprM (reviewed in reference 29). Bacterial RND pumps have also been shown to cause the efflux of many other organic compounds, including solvents and inhibitors (24, 29, 50). However, no natural products of P. aeruginosa have yet been shown to be subject to efflux via RND pumps.

Quorum sensing (or autoinduction) is the controlled expression of specific genes in response to extracellular chemical signals produced by the bacteria themselves (6). Typically cells emit an N-acyl homoserine lactone signal called an autoinducer (AI), which is usually synthesized by a LuxI-type AI synthase, into the environment (6). At high cell densities, the AI reaches a threshold concentration and binds to a LuxR-type protein which is then able to activate target genes (6). To date, luxR-luxI-type quorum-sensing systems and their N-acyl homoserine lactone AIs have been found in many different gram-negative bacteria (6). In P. aeruginosa the las (lasR-lasI) (7, 37) and rhl (rhlR-rhlI) (33, 34) quorum-sensing systems direct the synthesis of two distinct AIs, N-(3-oxododecanoyl) homoserine lactone (3OC12-HSL) (formerly called PAI-1) (40) and N-butyryl homoserine lactone (C4-HSL) (formerly called PAI-2) (41, 59), respectively. LasR and 3OC12-HSL activate expression of several genes, including lasI itself (54), lasB (encoding elastase) (37), lasA (encoding LasA protease) (8), both xcp operons (xcpPQ and xcpR-Z, encoding the type II secretion apparatus [3]), and rhlR (20, 44). Recently, the las quorum-sensing system was shown to be involved in P. aeruginosa biofilm differentiation (4). C4-HSL and RhlR also activate expression of numerous genes, including rhlI itself (20), the rhamnolipid biosynthesis operon rhlAB (32, 42), lasB (1, 41, 42), and rpoS (encoding the stationary-phase sigma factor ςs) (20).

Although many different N-acyl homoserine lactone AIs have been isolated from various gram-negative bacteria, to date, all differences are in the N-acyl side chain length (from C4 to C14) or degree of substitution (either 3-oxo, 3-hydroxy, saturated, or unsaturated) (6, 26, 48, 55). All AIs have been assumed to be freely diffusible in bacterial cells. This assumption is based on the fact that a radiolabeled Vibrio fischeri AI, N-3-oxo-hexanoyl homoserine lactone ([3H]3OC6-HSL), was shown to freely diffuse into and out of V. fischeri and Escherichia coli cells (15, 42). Here, we studied the uptake and efflux of 3OC12-HSL and C4-HSL by P. aeruginosa cells. Our results indicate that [3H]C4-HSL freely diffuses into and out of P. aeruginosa cells. In contrast, cellular concentrations of [3H]3OC12-HSL are higher than external levels. Our results show that the increased cellular level of [3H]3OC12-HSL is not due to association with LasR or RhlR and suggest that it is not due to active (inward) transport. We propose that the high cellular level of 3OC12-HSL is probably due to partitioning into the cell membranes. By use of P. aeruginosa Δ(mexAB-oprM) mutant cells or poisoned wild-type cells, we also show that 3OC12-HSL is subject to active efflux by the MexAB-OprM pump.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions.

The strains and plasmids used are shown in Table 1. Bacteria were grown at 37°C. When needed for plasmid maintenance, ampicillin (100 μg/ml) was included in cultures of E. coli and carbenicillin (200 μg/ml) was included in P. aeruginosa cultures. For β-galactosidase determinations, P. aeruginosa and E. coli were grown with shaking in PTSB medium (35) and supplemented A medium (40), respectively. Otherwise, P. aeruginosa cultures were grown with shaking in M9 medium (52) containing 0.2% glucose and 1 mM MgSO4. Overnight cultures were centrifuged (10,000 × g for 10 min at 20°C), and cell pellets were washed in fresh M9 medium and resuspended in M9 medium to an optical density at 660 nm of 0.075. These cultures were then grown to mid-logarithmic growth phase (optical density at 660 nm of 0.7). This corresponded to 1.3 × 109 CFU/ml.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| P. aeruginosa strains | ||

| PAO1 | Wild type | This laboratory |

| PAO-JP2 | ΔlasI ΔrhlI Tcr HgCl2r | 42 |

| PAO-JP3 | ΔlasR rhlR::Tn501 Tcr HgCl2r | 42 |

| PAO200 | Δ(mexA-mexB-oprM) unmarked | 53 |

| E. coli MG4λI14 | Δ(argF-lac)U169 zah-735::Tn10 recA56 srl::Tn10 λ::lasIp-lacZ | 54 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pPCS1 | ColE1 lasR+bla | 54 |

| pECP61.5 | ColE1 oriP. aeruginosa rhlAp-lacZ tacp-rhlR+bla | 42 |

| pUCP21T | oriP. aeruginosa bla | 53 |

| pPS952 | pUCP21T derivative; mexA+mexB+oprM+ | 53 |

Preparation of cell suspensions.

Cells were washed in KG buffer (10 mM potassium phosphate [pH 7.0], 0.03% glycerol) and resuspended in KG buffer to a cell density of 8 × 1010 CFU/ml.

Chemicals.

The syntheses of unlabeled 3OC12-HSL, [3H]3OC12-HSL (specific activity, 229 Ci/mmol), unlabeled C4-HSL, and [3H]C4-HSL (specific activity, 29.4 Ci/mmol) have been described previously (38, 41, 42). [3H]3OC12-HSL and [3H]C4-HSL are labeled with tritium on the respective acyl side chains (38, 42). Antibiotics and all other chemicals, including the three radioactive compounds [14C]ethylene glycol (specific activity, 1.5 mCi/mmol), [14C]dextran (specific activity, 1.25 mCi/g; average molecular weight of 70,000), and [14C]leucine (specific activity, 0.27 Ci/mmol), were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.

Determination of cellular AI concentrations.

The measurement of AI concentration was based on previously described techniques (15) with the following modifications. A 250-μl volume of cell suspension (2 × 1010 cells) was mixed with 50 μl of KG buffer containing the compound of interest (unless otherwise specified, the concentrations were as follows: [3H]3OC12-HSL or [3H]C4-HSL, 60 nM; [14C]leucine, 2.0 μM; [14C]ethylene glycol, 720 μM; or [14C]dextran, 1.7 μg/μl). Assay mixtures were incubated for 5 min (20 to 22°C) unless otherwise specified, and then duplicate 140-μl aliquots were centrifuged through 75 μl of Nyosil M25 silicone fluid (Nye Lubricants, New Bedford, Mass.) into 25 μl of aqueous 2% trichloroacetic acid–10% glycerol and radioactivity was counted as described previously (15). One percent of the input [3H]3OC12-HSL radioactivity entered the silicone fluid regardless of whether cells were present, and this was corrected for in subsequent calculations. No radioactivity was detected in the silicone fluid for the other radioactive compounds.

Cell volumes were calculated by a modification of a previously described method (51). We substituted P. aeruginosa PAO1 and its derivatives for E. coli. We measured accumulation of the freely permeative [14C]ethylene glycol in place of the [3H]-labeled AIs. Trapped extracellular fluid was measured by using the impermeative [14C]dextran.

[14C]leucine accumulation was also assayed by using the above-described technique. Prior to addition of the radiolabeled compounds, cells were pretreated for 30 min with chloramphenicol (final concentration of 5 mM) to inhibit protein synthesis. Accumulation of both 3H-AIs was unaffected by pretreating the cells with chloramphenicol. Thus, chloramphenicol was not included in further experiments with 3H-AIs.

Where indicated, either sodium azide (30 mM) or carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) (250 μM) was added to de-energize cells as described previously (16, 22).

Efflux assay.

Efflux of AI from cells was measured by comparing the cellular AI level with that remaining associated with the cells after removal of the external AI and then suspending the cells in a large excess of AI-free buffer as described previously (15). Incubation times were 20 and 5 min for cells with [3H]3OC12-HSL or [3H]C4-HSL, respectively, to reach steady-state levels. Duplicate 140-μl samples were transferred to 1.5-ml tubes and centrifuged for 1 min at 13,000 × g (20 to 22°C). Cells from one of the samples were suspended in 1.4 ml of KG buffer and centrifuged for 2 min as before. AI levels remaining with the cells after washing was compared with those remaining with cells that were not washed. Where indicated, sodium azide or CCCP was included in the wash buffer at the same concentrations as described above. Trapped extracellular fluid was corrected for by using [14C]dextran in place of the 3H-labeled AIs.

AI bioassays.

E. coli MG4λI14(pPCS1) was used to measure 3OC12-HSL as described previously (54). P. aeruginosa PAO-JP2(pECP61.5) was used to measure C4-HSL as described previously (42).

HPLC analysis of cellular AIs.

Analysis of cellular AIs was based on a previously described technique (15). Briefly, cells were incubated with [3H]3OC12-HSL or [3H]C4-HSL as described above and centrifuged (13,000 × g for 1 min at 20 to 22°C). Cell pellets were suspended in 20 μl of KG buffer and extracted twice in 0.2 ml of ethyl acetate, and then 20 nmol of unlabeled 3OC12-HSL or 24 nmol of unlabeled C4-HSL was added as a carrier to 0.15 ml of the respective [3H]3OC12-HSL or [3H]C4-HSL extract. Each mixture was then evaporated under N2 gas, and the material was dissolved in 10% (vol/vol) acetonitrile in water and subjected to reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (C18 column, 0.46 by 25 cm). The HPLC flow rate was 1 ml/min, and elution conditions are indicated in Fig. 1.

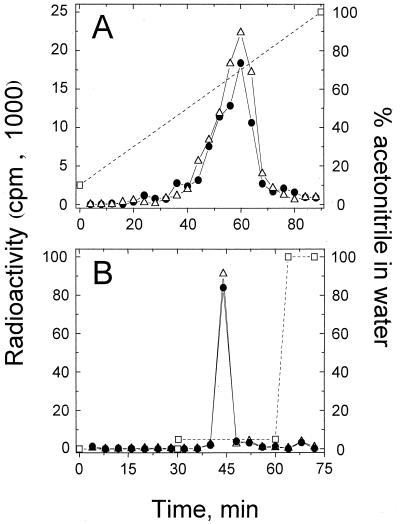

FIG. 1.

HPLC analysis of tritium-labeled material extracted from P. aeruginosa PAO1 that had been loaded with [3H]3OC12-HSL (A) or with [3H]C4-HSL (B) compared with [3H]3OC12-HSL and [3H]C4-HSL, respectively. Symbols: ●, material extracted from cells; ▵, 3H-AI; □, percent (volume/volume) acetonitrile in water.

RESULTS

Cellular concentrations of P. aeruginosa AIs.

In order to study AI uptake in P. aeruginosa, [3H]3OC12-HSL or [3H]C4-HSL was incubated with suspensions of wild-type cells (strain PAO1). After separation of the cells from the extracellular fluid by centrifugation through a layer of silicone fluid, radiolabeled AI was found to be associated with the cells. In order to calculate the internal concentration of each AI and compare it with external concentrations, cellular AI is assumed to be unmodified. A structurally similar AI molecule, [3H]3OC6-HSL, was reported to be unmodified in V. fischeri cells (15). To verify this assumption, P. aeruginosa PAO1 cells that had been loaded with either [3H]3OC12-HSL or [3H]C4-HSL were extracted with ethyl acetate as described in Materials and Methods. For [3H]C4-HSL-loaded cells, 100% of the radioactivity was recovered from the cells that had been loaded with this AI. In the case of [3H]3OC12-HSL, 75.2 ± 2.3% (average ± standard deviation [SD]; n = 3 independent experiments) of the radioactivity was recovered from cells. In both cases, when the extracted radioactivity was analyzed by HPLC, >90% of the radioactivity applied to the HPLC column eluted at the same point as the [3H]3OC12-HSL and [3H]C4-HSL standards, respectively (Fig. 1). For C4-HSL these results support the assumption that cellular radiolabel was in the form of unmodified [3H]C4-HSL. For [3H]3OC12-HSL, nearly all of the radiolabel extracted from cells was unmodified [3H]3OC12-HSL (Fig. 1), but 25% of the [3H]3OC12-HSL remained associated with the cells. It is possible that this fraction of the total [3H]3OC12-HSL accumulated by strain PAO1 may be chemically modified (such as by lactone ring hydrolysis or deacylation of the side chain) by the cells. Chemical modification of [3H]3OC12-HSL by the cells seems unlikely, because other AIs with structurally similar lactone rings and shorter acyl side chains, i.e., [3H]C4-HSL and [3H]3OC6-HSL, are not modified by P. aeruginosa (Fig. 1) or V. fischeri (15), respectively. It is, however, more likely that the 25% of [3H]3OC12-HSL remaining with cells may be unmodified yet is strongly associated with the cells (i.e., partitioned into the membranes) and could not be liberated by our method of extraction.

P. aeruginosa PAO1 incubated with [3H]C4-HSL yielded a cellular/extracellular concentration ratio of 0.92, which is close to the ratio of 0.96 obtained with the freely permeative [14C]ethylene glycol (Table 2). In contrast, the cellular [3H]3OC12-HSL concentration was 3.35-fold higher than the external concentration (Table 2). The fact that 3OC12-HSL appeared to be concentrated by cells opened the possibility that active (inward) transport could be involved.

TABLE 2.

P. aeruginosa PAO1 cellular and external AI concentrations

| Compound | External concna | Cellular concnb | Ratio of cellular to external concnc |

|---|---|---|---|

| [3H]3OC12-HSL | 69.1 ± 6.03 nM | 231 ± 16.8 nM | 3.35 |

| [3H]C4-HSL | 56.4 ± 6.93 nM | 51.9 ± 11.4 nM | 0.92 |

| [14C]ethylene glycol | 2.10 ± 0.07 mM | 2.00 ± 0.06 mM | 0.96 |

Calculated from the amount of radioactivity remaining above the silicone fluid after centrifugation. Values are the averages ± SDs from three or four experiments.

Calculated from the amount of radioactivity centrifuged through silicone fluid and the cell volume, with a correction for the small amount of extracellular material carried through the silicone fluid (measured with [14C]dextran). Values are the averages ± SDs from four independent experiments.

An unpaired t test determined that the ratio of 4.4 for 3OC12-HSL was significantly higher than the ratio of 0.92 for C4-HSL (P < 0.001) and the ratio of 0.96 for ethylene glycol (P < 0.001).

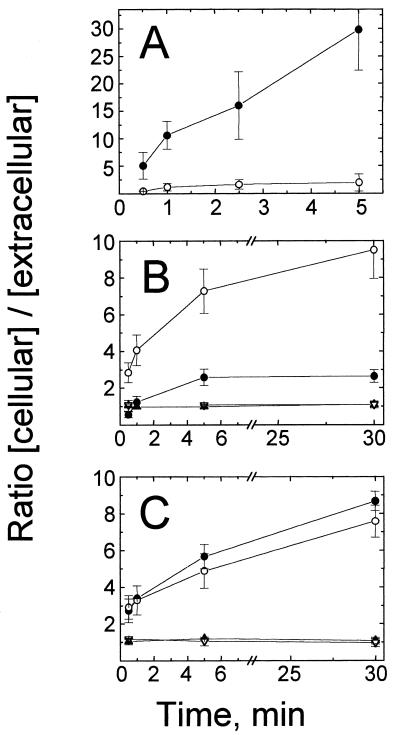

To address whether the silicone fluid centrifugation technique would be able to distinguish between the active and passive transport, the time course of P. aeruginosa uptake of [14C]leucine, which is known to be actively transported inward by P. aeruginosa (12), was measured (Fig. 2A). After 5 min of incubation in the presence of [14C]leucine, the cellular [14C]leucine concentration was greater than 20-fold higher than the external concentration (Fig. 2A), as previously reported (12). To demonstrate inhibition of active (inward) transport, cells were preincubated with sodium azide, which has been shown to block the active transport of leucine in P. aeruginosa (12, 16). As expected, the [14C]leucine level in cells pretreated with sodium azide reached only approximately twice the external level (Fig. 2A). These experiments demonstrated that the silicone fluid centrifugation technique would be able to detect active (inward) transport systems.

FIG. 2.

Accumulation of radiolabeled compounds by P. aeruginosa. (A) [14C]leucine accumulation in strain PAO1 treated with chloramphenicol (5 mM); (B) accumulation of [3H]3OC12-HSL (circles) and [3H]C4-HSL (triangles) in strain PAO1; (C) accumulation of [3H]3OC12-HSL (circles) and [3H]C4-HSL (triangles) in mexAB-orpM mutant strain PAO200. Closed symbols, non-azide-treated cells; open symbols, cells treated with sodium azide (30 mM). Accumulation of each compound was determined as described in Materials and Methods. Data are the averages (± SDs) of results from two to five independent experiments.

We then measured the time courses of [3H]3OC12-HSL and [3H]C4-HSL accumulation in strain PAO1 under the same conditions (Fig. 2B). In less than 30 s, the cellular concentration of [3H]C4-HSL reached a steady-state level that was approximately equal to the external concentration (Fig. 2B). The same results were obtained with the freely diffusible compound [14C]ethylene glycol (data not shown). P. aeruginosa cells seem to be freely permeable to C4-HSL, as V. fischeri cells are to 3OC6-HSL (15). In contrast, [3H]3OC12-HSL required about 5 min to reach a steady-state level, with a cellular-to-extracellular ratio of nearly 3 (Fig. 2B), suggesting that 3OC12-HSL transport was more complex than simple diffusion.

Because active (inward) transport of [14C]leucine was strongly inhibited when cells were pretreated with sodium azide, the effect of this poison on 3H-AI accumulation was also studied, and the results were surprising. Cellular [3H]3OC12-HSL concentrations rose to 10 times the extracellular concentrations (Fig. 2B), but azide treatment had no effect on accumulation of [3H]C4-HSL (Fig. 2B). These results suggest that 3OC12-HSL is not actively transported into P. aeruginosa as is leucine.

Azide and other agents, such as potassium cyanide and CCCP, that de-energize the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane potential (i.e., proton motive force [PMF]) are known to cause increases in cellular accumulation of various substances, including certain antibiotics (i.e., tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones, and some β-lactams) (21, 29). The increased accumulation occurs because PMF-dependent multidrug efflux pumps become inactivated in de-energized cells (29). Thus, these amphipathic antibiotics are no longer subject to active efflux out of the cells, resulting in the higher cellular antibiotic levels (29). In P. aeruginosa the mexAB-oprM operon constitutively expresses a PMF-dependent multidrug efflux pump (23, 46). To address whether the increased cellular [3H]3OC12-HSL concentrations observed in azide-treated cells were due to inhibition of this efflux pump, the [3H]3OC12-HSL concentration in a defined P. aeruginosa Δ(mexAB-oprM) mutant, strain PAO200 (53), was measured. This strain is derived from wild-type strain PAO1 and carries an unmarked deletion of the entire mexAB-oprM operon (53). The time course of accumulation of [3H]3OC12-HSL by strain PAO200 cells (Fig. 2C) resembled that by azide-treated strain PAO1 cells (Fig. 2B). The [3H]3OC12-HSL concentration observed in strain PAO200 cells was about eightfold higher than the external concentration, as we had observed for azide-treated PAO1 cells (Fig. 2B and C). Azide treatment of strain PAO200 resulted in almost no change in the cellular concentration of [3H]3OC12-HSL (Fig. 2C). These results suggested that the cellular level of [3H]3OC12-HSL is influenced by the presence of the mexAB-oprM-encoded efflux pump and further suggested that the high level of [3H]3OC12-HSL accumulated in azide-treated wild-type cells is due to inactivation of this PMF-dependent efflux pump. In contrast, when [3H]C4-HSL was added to strain PAO200 cells, the cellular-to-external concentration ratios were not significantly increased compared to those in strain PAO1 cells, and these levels were unaffected by poison (Fig. 2C). Therefore, C4-HSL accumulation in P. aeruginosa appears to be independent of MexAB-OprM.

Efflux of AIs.

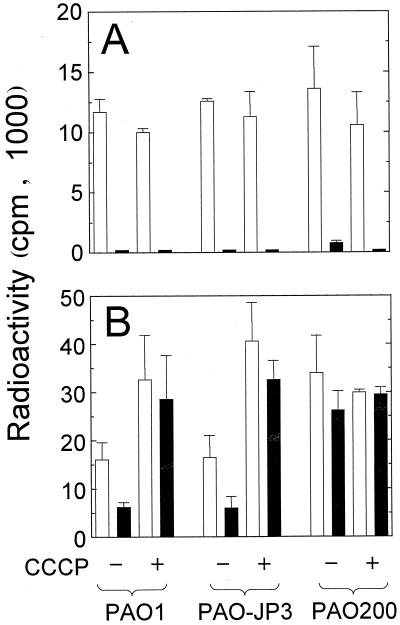

To further investigate the role of the mexAB-oprM-encoded PMF-dependent efflux pump on [3H]3OC12-HSL accumulation in P. aeruginosa, and to confirm that cells are freely permeable to [3H]C4-HSL, AI efflux was studied (Fig. 3). In theory, a freely diffusible compound would be expected to completely escape when cells loaded with the compound are transferred into a large volume of medium lacking the compound. Moreover, this free diffusion process would occur independently of the presence or absence of an active-efflux system. When strains PAO1 and PAO200 (ΔmexAB-oprM) were loaded with [3H]C4-HSL and transferred to AI-free buffer, cellular levels of this AI decreased 100 and 95%, respectively (Fig. 3A). When CCCP-treated cells (strains PAO1 and PAO200, respectively) were loaded with [3H]C4-HSL and then transferred to AI-free buffer, 100% of the radiolabel escaped from the cells (Fig. 3A). These results confirmed that P. aeruginosa cells are freely permeable to [3H]C4-HSL and that the mexAB-oprM-encoded efflux pump has no effect on efflux of this AI.

FIG. 3.

Efflux of [3H]C4-HSL (A) and [3H]3OC12-HSL (B) from P. aeruginosa PAO1 (wild type), PAO-JP3 (lasR rhlR), or PAO200 (mexABA-oprM). Open bars, radioactivity loaded in cells; closed bars, radioactivity remaining in cells after suspension in AI-free buffer. Cells were de-energized with CCCP (250 μM) as indicated. Data are the averages (± SDs) of results from two to four independent experiments.

A compound utilizing an efflux pump would escape more readily from cells containing an active-efflux system than from mutants lacking the system. As shown above, in both azide-poisoned strain PAO1 cells and mutant cells lacking the mexAB-oprM-encoded efflux pump (strain PAO200), the cellular accumulation of [3H]3OC12-HSL was higher than that in nonpoisoned strain PAO1 cells (Fig. 2B and C). In efflux experiments, the level of [3H]3OC12-HSL initially loaded in strain PAO200 [Δ(mexAB-oprM)] cells and in poisoned PAO1 cells was therefore higher than the level of [3H]3OC12-HSL initially loaded in unwashed strain PAO1 cells (Fig. 3B). When the external [3H]3OC12-HSL was removed and cells were suspended in AI-free buffer, 60% of the cellular radioactivity escaped from the wild-type cells and 30% escaped from mutant cells (strain PAO200) that lacked the efflux pump (Fig. 3B). This strongly suggested that P. aeruginosa cells are not freely permeable to [3H]3OC12-HSL and that the mexAB-oprM-encoded efflux pump facilitates efflux of this AI. Furthermore, when de-energized (CCCP-treated) strain PAO1 or PAO200 cells were loaded with [3H]3OC12-HSL and then transferred to AI-free buffer, very little [3H]3OC12-HSL escaped from either strain (Fig. 3B).

Therefore, unlike the freely permeative [3H]C4-HSL, which completely escaped from cells, 40% of cellular [3H]3OC12-HSL remained after transfer of strain PAO1 cells to AI-free buffer. To address the possibility that the remaining [3H]3OC12-HSL was bound to the AI-dependent transcriptional activator proteins encoded by lasR and rhlR, strain PAO-JP3, a defined lasR rhlR double mutant, was tested for [3H]3OC12-HSL efflux (and for [3H]C4-HSL efflux as a control). The results were nearly identical to those for efflux in strain PAO1 cells (Fig. 3). Therefore, the remaining cellular [3H]3OC12-HSL in strain PAO1 was not irreversibly bound to the LasR or RhlR protein. In a time course efflux experiment in which both CCCP-treated and nontreated wild-type cells that had been loaded with [3H]3OC12-HSL were suspended in AI-free buffer, 40% of the [3H]3OC12-HSL remained after 1 min with the nontreated cells and 80% remained with the CCCP-treated cells, as before. By 60 min (the duration of this experiment), 25% of the [3H]3OC12-HSL remained with the nontreated cells whereas 50% remained with the CCCP-treated cells (data not shown). The fact that some of the [3H]3OC12-HSL was released by CCCP-treated cells may be due to diffusion through the cell membranes in an efflux pump-independent fashion. This explanation would also account for the minor release of [3H]3OC12-HSL by strain PAO200 shown in Fig. 3.

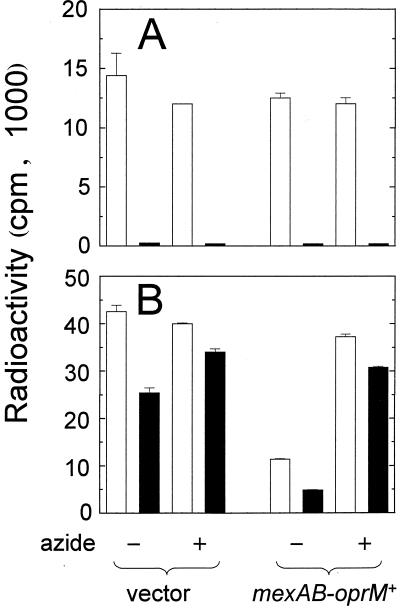

To confirm that the effects seen in strain PAO200 were due to the absence of mexAB-oprM, autoinducer efflux was measured in PAO200 cells containing either pUCP21T, a vector control plasmid, or pPS952, a pUCP21T derivative carrying a wild-type mexAB-oprM operon. When strain PAO200 contained pPS952, [3H]3OC12-HSL accumulated in these cells to levels similar to those observed in wild-type PAO1 cells (Fig. 4B and 3B), about fourfold less than for PAO200 containing the vector control. This indicated that efflux of [3H]3OC12-HSL was restored when strain PAO200 contained a functional mexAB-oprM-encoded pump. This efflux was strongly inhibited when strain PAO200(pPS952) cells were de-energized (Fig. 4B). As a control, efflux of [3H]C4-HSL from the mexAB-oprM mutant containing the mexA+ mexB+ oprM+ plasmid was also assayed. As expected, 98 to 100% of the [3H]C4-HSL was transported from the cells regardless of whether cells were de-energized or contained a functional mexAB-oprM operon (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

Efflux of [3H]C4-HSL (A) and [3H]3OC12-HSL (B) from P. aeruginosa PAO200 in the presence (labeled mexAB-oprM+ [pPS952]) or absence (labeled vector [pUCP21T]]) of mexAB-oprM. Open bars, radioactivity loaded in cells; closed bars, radioactivity remaining in cells after suspension in AI-free buffer. Cells were de-energized with sodium azide (30 mM) as indicated. Data are the averages (± SDs) of results from two independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

This study shows that both C4-HSL and 3OC12-HSL diffuse into and out of P. aeruginosa. We found that the cellular concentration of [3H]C4-HSL quickly reached a steady state in wild-type P. aeruginosa cells at a level that was nearly equal to the external level, suggesting a passive diffusion process. Thus, we have shown that P. aeruginosa is freely permeable to C4-HSL as both V. fischeri and E. coli are freely permeable to 3OC6-HSL (15). In contrast, [3H]3OC12-HSL required about 5 min to reach a steady-state cellular concentration of nearly threefold the external level (Fig. 2B), indicating a more complex transport process. HPLC analysis indicated that P. aeruginosa did not modify the cellular [3H]C4-HSL and did not modify 75% of the [3H]3OC12-HSL that was loaded into the cells. The remaining 25% of the cellular [3H]3OC12-HSL could have been chemically modified; however, it is more likely that it is unmodified and partitioned into the cell membranes. Most importantly, this 25% does not significantly influence our conclusions about active efflux of [3H]3OC12-HSL from P. aeruginosa cells.

Thus, while 3OC12-HSL freely diffuses into and out of P. aeruginosa, the cells accumulate more of this compound because of passive partitioning into membranes. Superimposed on these processes, 3OC12-HSL is subject to active efflux from P. aeruginosa via the MexAB-OprM pump.

[3H]3OC12-HSL does not seem to be actively transported into P. aeruginosa. Indeed, accumulation of this AI was not inhibited in de-energized cells but actually increased (Fig. 2B). De-energization of the cytoplasmic membrane potential (i.e., PMF) by azide and other poisons such as CCCP results in a strong increase in the accumulation of certain antibiotics by some gram-negative bacteria (21, 29). In P. aeruginosa these effects have been associated with inhibition of the PMF-dependent mexAB-oprM-encoded efflux pump (23, 46).

We have observed that a P. aeruginosa Δ(mexAB-oprM) mutant accumulated about threefold more [3H]3OC12-HSL than untreated wild-type cells. Because de-energization of strain PAO200 cells had essentially no effect on the time course of accumulation of [3H]3OC12-HSL (Fig. 2C), these results strongly suggest that the MexAB-OprM efflux is the only PMF-dependent efflux pump involved in regulation of cellular levels of 3OC12-HSL under these conditions. However the P. aeruginosa mexCD-oprJ- and mexEF-oprN-encoded multidrug pumps may also be involved in efflux of 3OC12-HSL under other conditions where those operons would be expressed.

From our efflux experiments we conclude that 3OC12-HSL efflux depends on the presence of an active MexAB-OprM pump. While this paper was being prepared, others also suggested that 3OC12-HSL may be exported by the mexAB-oprM-encoded pump (5a). Here, we found that the percentage of [3H]3OC12-HSL retained after resuspension in AI-free buffer was higher in de-energized wild-type cells and in mexAB-oprM mutant cells than in nontreated wild-type cells (Fig. 3B). The observation that the remaining cellular 3OC12-HSL slowly escaped even when the cells were de-energized suggests that a gradual release of this AI likely occurs in addition to active efflux of the majority of cellular 3OC12-HSL via the MexAB-OprM pump. One explanation for the slow efflux of 3OC12-HSL from the cells may be that 3OC12-HSL partitions into the cell membranes. The respective lengths of the acyl side chains of the two AIs are probably responsible for the differences in accumulation observed between the relatively hydrophobic 3OC12-HSL and the more hydrophilic C4-HSL. We propose that 3OC12-HSL transport by P. aeruginosa occurs by a mechanism similar to that of amphipathic antibiotics such as tetracycline, fluoroquinolones, and β-lactams. Nikaido has presented a model in which those antibiotics diffuse and partition in gram-negative bacterial cell membranes and are subject to active efflux from the cells by PMF-dependent RND pumps (29). Recent results with an RND pump (AcrAB) of Salmonella typhimurium have extended this model and suggested that penicillins and cephalosporins containing more-lipophilic side chains are more likely to partition into the lipid bilayer of the cytoplasmic membrane (31). The model suggests that once these β-lactam antibiotics are partitioned into the cytoplasmic membrane, they can then become substrates of the RND pump (31). Future studies will be required to elucidate the likely mechanism(s) (i.e., membrane partitioning) apparently involved in 3OC12-HSL accumulation, besides the role of the MexAB-OprM pump described here.

A natural substrate of MexAB-OprM.

PMF-dependent RND pumps in P. aeruginosa are known to cause the efflux of various toxic substances, such as antibiotics (18, 23, 45), fatty acid inhibitors (53), and organic solvents (24), out of cells. 3OC12-HSL is the first example of a natural product of P. aeruginosa that is subject to efflux by a PMF-dependent RND pump. Our results show that the other P. aeruginosa AI, C4-HSL, is not a substrate of MexAB-OprM, which indicates specificity for long-chain AIs. Based on the broad spectrum of compounds that RND pumps are known to transport, other small amphipathic molecules produced by P. aeruginosa are likely to be subject to efflux by these pumps as well.

Cell-to-cell signaling and RND pumps.

The discovery that 3OC12-HSL is subject to efflux by an RND pump suggests that regulation of genes controlled by 3OC12-HSL and LasR, such as those encoding elastase (lasB) or the type II secretion apparatus (xcp operons), is likely to be affected by the presence of a MexAB-OprM pump and PMF. In theory, as PMF decreases, the efflux pump activity would also decrease, causing the cellular concentration of 3OC12-HSL to rise. The expected result would be increased activation of las quorum-sensing target genes such as those mentioned above. Interestingly, in the early 1980s others observed that in P. aeruginosa, extracellular protease production increased as the PMF decreased (58). Those findings, together with the results presented here which demonstrate that 3OC12-HSL concentrations in P. aeruginosa cells are higher in de-energized cells or those lacking the MexAB-OprM efflux pump, suggest that the timing of induction of genes controlled by LasR and 3OC12-HSL may be affected by PMF-dependent AI efflux. A higher cellular 3OC12-HSL concentration would be expected sooner during the growth of P. aeruginosa lacking a functional MexAB-OprM efflux pump, resulting in earlier expression of target genes. Indeed, P. aeruginosa quorum-sensing target genes are controlled by a hierarchy of induction based on the AI concentration (43, 54). Because of the roles that the las quorum-sensing system play in virulence and biofilm differentiation (4, 56), experiments with the mexAB-oprM mutant will need to examine if the timing of biofilm differentiation and virulence are affected.

Because 3OC12-HSL may be partitioned into the P. aeruginosa membranes by the same mechanism as other amphipathic compounds, future studies will need to examine the role of P. aeruginosa membranes in quorum sensing. Although others have shown that in V. fischeri the 3OC6-HSL-dependent transcriptional activator of the lux genes, LuxR, is associated with the inner membrane (19), it is not known whether LasR associates with the P. aeruginosa inner membrane.

Components of quorum-sensing systems (a luxR-luxI homologue and/or an N-acyl homoserine lactone AI) and RND-type efflux systems (a mexA, mexB, or oprM homologue or all three) have been identified in numerous gram-negative bacteria. Agrobacterium tumefacians synthesizes 3OC8-HSL (60), Rhizobium leguminosarum is known to produce 7,8-cis-3-hydroxy-C14-HSL (10), Rhizobium meliloti produces an AI of unknown structure (10) which comigrates in HPLC with 7,8-cis-C14-HSL of Rhodobacter sphaeroides (48), and Pseudomonas putida and Burkholderia cepacia also produce AI activity detected in a 3OC8-HSL assay (39a). Homologues of at least one component of the P. aeruginosa MexAB-OprM system have been identified in all of these species except R. sphaeroides. In the plant symbionts R. meliloti and R. leguminosarum, the respective mexAB-oprM homologues may be involved in efflux of nodulation signals (29, 39). In P. putida, the srpABC operon and ttgB, respectively, were shown to cause efflux of organic solvents (17, 50). In the human pathogen B. cepacia, a mexAB-oprM homologue is involved in multiple antibiotic resistance (2), and in the plant pathogen A. tumefacians, ifeAB encode an isoflavanoid-inducible efflux pump that is involved in colonization of plant roots (36). Thus, it is likely that cell-to-cell communication systems in species other than P. aeruginosa that rely on N-acyl homoserine lactones containing long-chain AIs will also involve RND pumps.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank H. P. Schweizer for providing the P. aeruginosa mexAB-oprM mutant PAO200 and plasmids. We also thank A. Kende for earlier collaboration on the synthesis of tritium-labeled 3OC12-HSL, E. P. Greenberg for advice and the use of his centrifuge, and V. Clark for her advice and critical evaluation of the data.

This work was supported in part by NIH grant AI33713 (to B.H.I.), NIH predoctoral training grant 5T32AI07362 (to J.P.P.), and Wilmot Foundation and Swiss Research Federation grants (to C.V.D.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Brint J M, Ohman D E. Synthesis of multiple exoproducts in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is under the control of RhlR-RhlI, another set of regulators in strain PAO1 with homology to the autoinducer-responsive LuxR-LuxI family. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:7155–7163. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.24.7155-7163.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burns J L, Wadsworth C D, Barry J J, Goodall C P. Nucleotide sequence analysis of a gene from Burkholderia (Pseudomonas) cepacia encoding an outer membrane lipoprotein involved in multiple antibiotic resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:307–313. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.2.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chapon-Herve V, Akrim M, Latifi A, Williams P, Lazdunski A, Bally M. Regulation of the xcp secretion pathway by multiple quorum-sensing modulons in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:1169–1178. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4271794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies D G, Parsek M R, Pearson J P, Iglewski B H, Costerton J W, Greenberg E P. The involvement of cell-to-cell signals in the development of a bacterial biofilm. Science. 1998;280:295–298. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5361.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Bentzmann S, Roger P, Bajolet-Laudinat O, Fuchey C, Plotkowski M C, Puchell E. Asialo GM1 is a receptor for Pseudomonas aeruginosa adherence to regenerating respiratory epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1582–1588. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.5.1582-1588.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5a.Evans K, Passador L, Srikumar R, Tsang E, Nezezon J, Poole K. Influence of the MexAB-OprM multidrug efflux system on quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5443–5447. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.20.5443-5447.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuqua W C, Winans S C, Greenberg E P. Census and consensus in bacterial ecosystems: the LuxR-LuxI family of quorum-sensing transcriptional regulators. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1996;50:727–751. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gambello M J, Iglewski B H. Cloning and characterization of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa lasR gene, a transcriptional activator of elastase expression. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:3000–3009. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.9.3000-3009.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gambello M J, Kaye S, Iglewski B H. LasR of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a transcriptional activator of the alkaline protease gene (apr) and an enhancer of exotoxin A expression. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1180–1184. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.4.1180-1184.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Govan J R, Deretic V. Microbial pathogenesis in cystic fibrosis: mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:539–574. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.3.539-574.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gray K M, Pearson J P, Downie J A, Boboye B E, Greenberg E P. Cell-to-cell signaling in the symbiotic nitrogen-fixing bacterium Rhizobium leguminosarum: autoinduction of stationary-phase and rhizosphere-expressed genes. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:372–376. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.2.372-376.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hancock R E. Resistance mechanisms in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other nonfermentative gram-negative bacteria. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:S93–S99. doi: 10.1086/514909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoshino T. Transport systems for branched-chain amino acids in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1979;139:705–712. doi: 10.1128/jb.139.3.705-712.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howe T R, Iglewski B H. Isolation and characterization of alkaline protease-deficient mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in vitro and in a mouse eye model. Infect Immun. 1984;43:1058–1063. doi: 10.1128/iai.43.3.1058-1063.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iglewski B H, Liu P V, Kabat D. Mechanism of action of Pseudomonas aeruginosa exotoxin A in adenosine diphosphate-ribosylation of mammalian elongation factor 2 in vitro and in vivo. Infect Immun. 1977;15:138–144. doi: 10.1128/iai.15.1.138-144.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaplan H B, Greenberg E P. Diffusion of autoinducer is involved in regulation of the Vibrio fischeri luminescence system. J Bacteriol. 1985;163:1210–1214. doi: 10.1128/jb.163.3.1210-1214.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kay W W, Gronlund A F. Amino acid transport in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1969;97:273–281. doi: 10.1128/jb.97.1.273-281.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kieboom J, Dennis J J, de Bont J A M, Zylstra G J. Identification and molecular characterization of an efflux pump involved in Pseudomonas putida S12 solvent tolerance. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:85–91. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kohler T, Michea-Hamzehpour M, Henze U, Gotoh N, Curty L K, Pechere J C. Characterization of MexE-MexF-OprN, a positively regulated multidrug efflux system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:345–354. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2281594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kolibachuk D, Greenberg E P. The Vibrio fischeri luminescence gene activator LuxR is a membrane-associated protein. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7307–7312. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.22.7307-7312.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Latifi A, Foglino M, Tanaka K, Williams P, Lazdunski A. A hierarchical quorum-sensing cascade in Pseudomonas aeruginosa links the transcriptional activators LasR and RhlR (VsmR) to expression of the stationary-phase sigma factor RpoS. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:1137–1146. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.00063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levy S B. Active efflux mechanisms for antimicrobial resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:695–703. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.4.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li X Z, Livermore D M, Nikaido H. Role of an efflux pump(s) in intrinsic resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: resistance to tetracycline, chloramphenicol, and norfloxacin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1732–1741. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.8.1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li X Z, Nikaido H, Poole K. Role of mexA-mexB-oprM in antibiotic efflux in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1948–1953. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.9.1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li X Z, Zhang L, Poole K. Role of the multidrug efflux systems of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in organic solvent tolerance. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2987–2991. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.11.2987-2991.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu P V. Extracellular toxins of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Infect Dis. 1974;130:94–99. doi: 10.1093/infdis/130.supplement.s94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Milton D L, Hardman A, Camara M, Chhabra S R, Bycroft B W, Stewart G S, Williams P. Quorum sensing in Vibrio anguillarum: characterization of the vanI/vanR locus and identification of the autoinducer N-(3-oxodecanoyl)-l-homoserine lactone. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3004–3012. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.9.3004-3012.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morihara K, Homma J Y. Bacterial enzymes and virulence. In: Holder I A, editor. Pseudomonas proteases. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1985. pp. 41–79. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nicas T I, Iglewski B H. Contribution of exoenzyme S to the virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antibiot Chemother. 1985;36:40–48. doi: 10.1159/000410470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nikaido H. Multidrug efflux pumps of gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5853–5859. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.20.5853-5859.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nikaido H. Antibiotic resistance caused by gram-negative multidrug efflux pumps. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:S32–S41. doi: 10.1086/514920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nikaido H, Basina M, Nguyen V, Rosenberg E Y. Multidrug efflux pump AcrAB of Salmonella typhimurium excretes only those β-lactam antibiotics containing lipophilic side chains. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4686–4692. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4686-4692.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ochsner U A, Fiechter A, Reiser J. Isolation, characterization, and expression in Escherichia coli of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa rhlAB genes encoding a rhamnosyltransferase involved in rhamnolipid biosurfactant synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:19787–19795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ochsner U A, Koch A K, Fiechter A, Reiser J. Isolation and characterization of a regulatory gene affecting rhamnolipid biosurfactant synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2044–2054. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.7.2044-2054.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ochsner U A, Reiser J. Autoinducer-mediated regulation of rhamnolipid biosurfactant synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6424–6428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ohman D E, Cryz S J, Iglewski B H. Isolation and characterization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO mutant that produces altered elastase. J Bacteriol. 1980;142:836–842. doi: 10.1128/jb.142.3.836-842.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palumbo J D, Kado C I, Phillips D A. An isoflavonoid-inducible efflux pump in Agrobacterium tumefaciens is involved in competitive colonization of roots. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3107–3113. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.12.3107-3113.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Passador L, Cook J M, Gambello M J, Rust L, Iglewski B H. Expression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence genes requires cell-to-cell communication. Science. 1993;260:1127–1130. doi: 10.1126/science.8493556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Passador L, Tucker K D, Guertin K R, Journet M P, Kende A S, Iglewski B H. Functional analysis of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa autoinducer PAI. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5995–6000. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.20.5995-6000.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paulsen L T, Brown M H, Skurray R A. Proton-dependent multidrug efflux systems. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:575–608. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.4.575-608.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39a.Pearson, J. P. Unpublished data.

- 40.Pearson J P, Gray K M, Passador L, Tucker K D, Eberhard A, Iglewski B H, Greenberg E P. Structure of the autoinducer required for expression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:197–201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.1.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pearson J P, Passador L, Iglewski B H, Greenberg E P. A second N-acylhomoserine lactone signal produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1490–1494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pearson J P, Pesci E C, Iglewski B H. Role of Pseudomonas aeruginosa las and rhl quorum-sensing systems in the control of elastase and rhamnolipid biosynthesis genes. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5756–5767. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.18.5756-5767.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pesci E C, Iglewski B H. The chain of command in Pseudomonas quorum sensing. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:132–134. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pesci E C, Pearson J P, Seed P C, Iglewski B H. Regulation of las and rhl quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3127–3132. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.10.3127-3132.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Poole K, Gotoh N, Tsujimoto H, Zhao Q, Wada A, Yamasaki T, Neshat S, Yamagishi J, Li X Z, Nishino T. Overexpression of the mexC-mexD-oprJ efflux operon in nfxB-type multidrug-resistant strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:713–724. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.281397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Poole K, Krebes K, McNally C, Neshat S. Multiple antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: evidence for involvement of an efflux operon. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7363–7372. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.22.7363-7372.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Preston M J, Seed P C, Toder D S, Iglewski B H, Ohman D E, Gustin J K, Goldberg J B, Pier G B. Contribution of proteases and LasR to the virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa during corneal infections. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3086–3090. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3086-3090.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Puskas A, Greenberg E P, Kaplan S, Schaefer A L. A quorum-sensing system in the free-living photosynthetic bacterium Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7530–7537. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.23.7530-7537.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Quinn J P. Clinical problems posed by multiresistant nonfermenting gram-negative pathogens. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:S117–S124. doi: 10.1086/514912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ramos J L, Duque E, Godoy P, Segura A. Efflux pumps involved in toluene tolerance in Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3323–3329. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.13.3323-3329.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rottenberg H. The measurement of membrane potential and ΔpH in cells, organelles, and vesicles. Methods Enzymol. 1979;55:547–569. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(79)55066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schweizer H P. Intrinsic resistance to inhibitors of fatty acid biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is due to efflux: application of a novel technique for generation of unmarked chromosomal mutations for the study of efflux systems. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:394–398. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.2.394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seed P C, Passador L, Iglewski B H. Activation of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa lasI gene by LasR and the Pseudomonas autoinducer PAI: an autoinduction regulatory hierarchy. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:654–659. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.3.654-659.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shaw P D, Ping G, Daly S L, Cha C, Cronan J E J, Rinchart K L, Farrand S K. Detecting and characterizing N-acyl-homoserine lactone signal molecules by thin-layer chromatography. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6036–6041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tang H B, DiMango E, Bryan R, Gambello M, Iglewski B H, Goldberg J B, Prince A. Contribution of specific Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence factors to pathogenesis of pneumonia in a neonatal mouse model of infection. Infect Immun. 1996;64:37–43. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.37-43.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Van Delden C, Iglewski B H. Cell-signaling and the pathogenesis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Emerg Infect Dis. 1998;4:551–560. doi: 10.3201/eid0404.980405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Whooley M A, McLoughlin A J. The protonmotive force in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and its relationship to exoprotease production. J Gen Microbiol. 1983;129:989–996. doi: 10.1099/00221287-129-4-989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Winson M K, Camara M, Latifi A, Foglino M, Chhabra S R, Daykin M, Bally M, Chapon V, Salmond G P, Bycroft B W, et al. Multiple N-acyl-l-homoserine lactone signal molecules regulate production of virulence determinants and secondary metabolites in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9427–9431. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang L, Murphy P J, Kerr A, Tate M E. Agrobacterium conjugation and gene regulation by N-acyl-l-homoserine lactones. Nature. 1993;362:446–448. doi: 10.1038/362446a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]