Abstract

Purpose

During COVID‐19, stigmatization and violence against and between professional healthcare workers worldwide are increasing. Understanding the prevalence of such stigmatization and violence is needed for gaining a complete picture of this issue. Therefore, the purpose of this review was to update estimates of the prevalence of stigmatization and violence against healthcare workers during the pandemic.

Design

A systematic review and meta‐analysis was conducted.

Methods

This review followed PRISMA guidelines and encompassed these databases: PubMed, Academic Search Complete, CINAHL, Web of Science, MEDLINE Complete, OVID (UpToDate), and Embase (from databases inception to September 15, 2021). We included observational studies and evaluated the quality of the study using the Joanna Briggs Institute methodology. Further, a random effects model was used to synthesis the pooled prevalence of stigmatization and violence in this study.

Findings

We identified 14 studies involving 3452 doctors, 5738 nurses, and 2744 allied health workers that reported stigmatization and violence during the pandemic. The pooled prevalence was, for stigmatization, 43% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 21% to 65%) and, for violence, 42% (95% CI: 30% to 54%).

Conclusions

Stigmatization and violence during the COVID‐19 pandemic were found to have affected almost half the studied healthcare workers. Healthcare professionals are more prone to be stigmatized by the community and to face workplace violence.

Clinical Relevance

Health administrators and policymakers should anticipate and promptly address stigmatization and violence against and between healthcare workers, while controlling the spread of COVID‐19. Health care systems should give serious attention to the mental health of all health providers.

Keywords: COVID‐19, healthcare workers, meta‐analyses, stigmatization, violence

Globally, 275,233,892 cases of the coronavirus (COVID‐19) had been diagnosed as of September 21, 2021, with 5,364,996 deaths—numbers that are still rising everyday (WHO, 2021). The high number of COVID‐19 cases and accompanying deaths has put an enormous amount of pressure on healthcare workers (i.e., doctors or nurses) throughout the world (Conti et al., 2021). As a result of public anxiety that healthcare workers are sources of infection, the COVID‐19 outbreak has increased the risk of stigmatization and violence against professionals in their home neighborhoods and places of employment, including being avoided or outcast (Bagcchi, 2020; Bitencourt et al., 2021; Dye et al., 2020; Ghareeb et al., 2021). Updated estimates of the global prevalence of stigmatization and violence against healthcare workers during the pandemic are desperately needed to raise awareness and develop strategies to support a safe workplace so that healthcare workers can deliver quality patient care. Therefore, the goal of this study was to quantify the incidence of stigmatization and violence among healthcare workers during the COVID‐19 pandemic.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design

The PRISMA guidelines were used to perform this review (Page et al., 2021) (Supplementary S1). The study was registered in PROSPERO CRD42021271121.

Search strategy

A comprehensive search encompassed these databases: PubMed, Academic Search Complete, CINAHL, Web of Science, MEDLINE Complete, OVID (UpToDate), and EMBASE from inception to September 15, 2021. Keywords that were utilized included “Healthcare workers” OR “health worker” OR “health care provider” OR “professionals” OR “front line workers” OR “nurses” OR “doctor” OR “paramedic” OR “medical workers” AND “violence” OR “violent” OR “harassment” OR “stigmatization” OR “aggression” OR “anger” OR “discrimination” AND “COVID‐19” OR “SARS‐CoV‐2” OR “coronavirus disease 2019” OR “con‐19” OR “coronavirus disease” OR “2019 n‐cov” AND “cohort study” OR “case–control study” OR “cross‐sectional study” (Supplementary S2).

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included if they (a) involved professionals who worked in healthcare facilities during the COVID‐19 pandemic; (b) provided the incidence of stigmatization or violence (c) the studies were observational (i.e., cohort or cross‐sectional studies); and (d) the studies were written in English. Publications that did not describe incidents of stigmatization or violence, as well as those that were peer‐reviewed or not original studies, were excluded. Two authors together determined the eligibility criteria. Any discrepancies uncovered throughout the screening process were resolved by reaching an agreement with a third reviewer.

Data collection

The studies were reviewed by two authors separately based on the title and abstract. The whole text of articles that passed the initial screening was then screened. Any discrepancies uncovered throughout the screening process were resolved by reaching an agreement with a third reviewer. When appropriate studies were identified, data on authors, year, and country; research design and sample size; participants' age, gender, and occupation; and incidence of stigmatization and violence were retrieved.

Quality assessment

Using the 8‐question Joanna Briggs Institute tool for cross‐sectional studies and the 10‐question Joanna Briggs Institute instrument for case–control studies, two authors independently rated the level of each publication as well as the quality of each cohort study design (Buccheri & Sharifi, 2017; Joanna Briggs Institute, 2020). Each item was assigned a score ranging from 0 to 1, indicating a high risk of bias or a low risk of bias. A number of 4 or less indicates low quality for cross‐sectional studies, while a score more than 4 suggests good quality; for case–control studies, a score of 5 or less indicates low quality, and a score greater than 5 indicates high quality.

Statistical analysis

The pooled prevalence of stigmatization and violence against healthcare professionals during the pandemic was estimated using a meta‐analysis with a random effects model. The I 2 was also used to identify the analyses' heterogeneity, with percentages of 25%, 50%, and 75% indicating low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively (Huedo‐Medina et al., 2006). Further, funnel plots and the Egger regression test were analyzed to evaluate potential bias (Sterne et al., 2000; Sterne & Egger, 2001). The significance level was set at p < 0.05. The Stata software tool was used for all statistical analyses (version 16.0: StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

RESULTS

Study selection

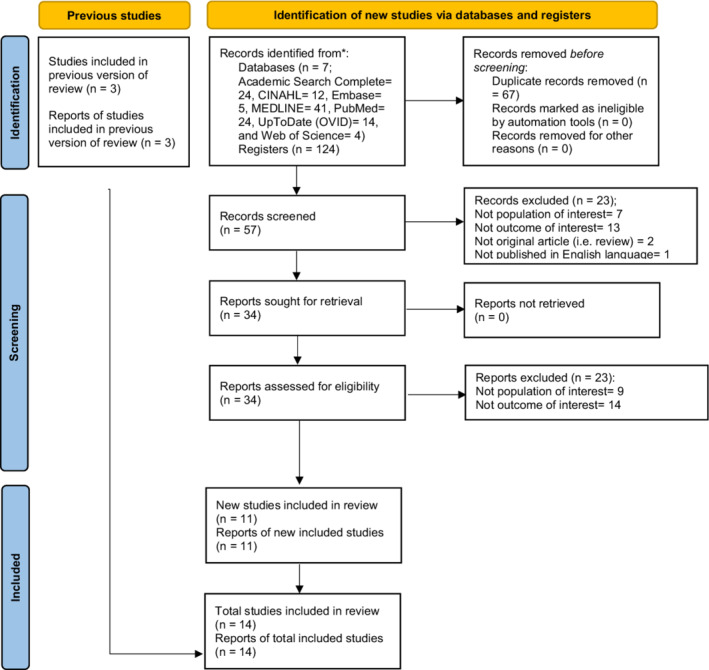

A search of the literature generated 124 citations. EndNote X9 software was used to delete 67 duplicates. Titles and abstracts were screened for the remaining 57 citations, 23 of these were deleted because they did not meet the PICOS criteria; was not the target population (n = 7), did not include outcomes of interest (n = 13), not an observational study design (n = 2), or the study was not available in English (n = 1). The remaining 34 publications were thoroughly reviewed for eligibility, excluded another 23 studies because they did not include the target population (n = 9) or the outcomes of interest (n = 14). The final analysis includes 14 studies; Adhikari et al., 2021; Bitencourt et al., 2021; Dye et al., 2020; Elhadi et al., 2020; Ghareeb et al., 2021; Khanal et al., 2020; Mohindra et al., 2021; Mostafa et al., 2020; Özkan Şat et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2020; Yadav et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2021; Zandifar et al., 2020; and Zhu et al., 2020. Figure 1 summarizes the source selection process in a PRISMA flow diagram.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. *Consider, if feasible to do so, reporting the number of records identified from each database or register searched (rather than the total number across all databases/registers). **If automation tools were used, indicate how many records were excluded by a human and how many were excluded by automation tools.

Studies characteristics

This review included a total of 14 cross‐sectional studies. Three studies were undertaken in China, 2 in Nepal, 2 in India, and 1 in each of Brazil, Egypt, Iran, Jordan, Libya, Turkey, and the United States. The analyses included 34,873 healthcare workers in total. The health care occupations were distributed as follows: 3452 doctors, 5738 nurses, and 2744 allied healthcare workers. In the studies that did report ages, participants ranged in age from 19 to 40 or more years. Across the studies, the prevalence among healthcare workers of mental health problems related to stigmatization ranged from 19% to 95% and those related to violence ranged from 8% to 70%. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the selected studies.

TABLE 1.

Selected studies on stigmatization and violence against and between healthcare workers during COVID‐19

| Reference | Country | Country'sincomestatus | Studydesign | Samplesize(N) | Men(n) | Age(medianyears) | HCWs (n) | Outcomes | Stigmatization(n [%]) | Violence(n [%]) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doctor | Nurse | Alliedhealth | ||||||||||

| Dye et al., 2020 | USA | Upper–middle | Cross‐sectional | 7411 | 366 | <32, >32 | General violence | 595 (8) | ||||

| Elhadi et al., 2020 | Libya | Low | Cross‐sectional | 745 | 358 | 33.3 | 265 | Stigmatization | 231 (31) | |||

| Khanal et al., 2020 | Nepal | Low | Case–control | 475 | 225 | ≥28.20 | Stigmatization | 255 (54) | ||||

| Mostafa et al., 2020 | Egypt | Upper–middle | Cross‐sectional | 509 | 156 | 39 | Stigmatization | 486 (95) | ||||

| Wang et al., 2020 | China | Upper–middle | Cross‐sectional | 1063 | 803 | 34.2 | 827 | 872 | 883 | Discrimination | 327 (31) | |

| Yadav et al., 2020 | India | Low | Cross‐sectional | 424 | 180 | 298 | 29 | 466 | Stigmatization;violence (physicaland psychological) | 82 (19) | ||

| Zandifar et al., 2020 | Iran | Low | Cross‐sectional | 894 | 254 | <30, >40 | 80 | 543 | Discrimination | 281 (31) | ||

| Zhu et al., 2020 | China | Upper–middle | Cross‐sectional | 5062 | 0 | >19 | 1004 | 3417 | 641 | Discrimination | 987 (19) | |

| Adhikari et al., 2021 | Nepal | Low | Cross‐sectional | 213 | 106 | ≥29 | Stigmatization | 116 (54) | ||||

| Bitencourt et al., 2021 | Brazil | Low | Cross‐sectional | 1166 | 288 | >18 | 641 | 180 | 345 | General violence | 574 (49) | |

| Ghareeb et al., 2021 | Jordan | Upper–middle | Cross‐sectional | 382 | 162 | 40.24 | 170 | 212 | Violence (physicaland psychological) | 250 (65) | ||

| Mohindra et al., 2021 | India | Low | Cross‐sectional | 574 | 208 | 30.21 | 167 | 178 | 218 | Stigmatization | 294 (51) | |

| Özkan Şat et al., 2021 | Turkey | Upper–middle | Cross‐sectional | 424 | 31 | 31,26 | 307 | 191 | Violence (physicaland psychological) | 297 (70) | ||

| Yang et al., 2021 | China | Upper–middle | Cross‐sectional | 15,531 | 1770 | 33.42 | Violence | 2878 (19) | ||||

Abbreviation: HCWs, healthcare workers.

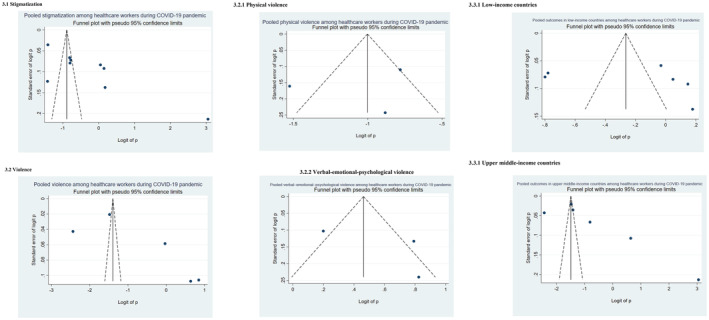

Risk of bias in studies

Overall, the risk of bias was deemed to be low in all of the included studies examined (Table 2). In addition, one limitation of this study was the presence of asymmetric outliers, which suggested probable publication bias. Figure 3 depicts the funnel plot. The Egger regression test, on the other hand, showed that the impact of publication bias was small.

TABLE 2.

Quality assessment of cross‐sectional studies

| Joanna Briggs Institute checklist question | Dye et al., 2020 | Elhadi et al., 2020 | Khanal et al., 2020 | Mostafa et al., 2020 | Wang et al., 2020 | Yadav et al., 2020 | Zandifar et al., 2020 | Zhu et al., 2020 | Adhikari et al., 2021 | Bitencourt et al., 2021 | Ghareeb et al., 2021 | Mohindra et al., 2021 | Özkan Şat et al., 2021 | Yang et al., 2021 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Were the criteria for inclusion in the sample clearly defined? | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| 2 | Were the study subjects and the setting described in detail? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 3 | Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way? | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| 4 | Were objective, standard criteria used for measurement of the condition? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 5 | Were confounding factors identified? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 6 | Were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated? | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| 7 | Were the outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 8 | Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Overall appraisal | |||||||||||||||

| Include (Y total) | 8 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 8 | |

| Exclude (N total) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| Level of evidence | 4.c | 4.c | 4.c | 4.c | 4.c | 4.c | 4.c | 4.c | 4.c | 4.c | 4.c | 4.c | 4.c | 4.c | |

Note: Y = 1; N = 0; 4.c = case series.

FIGURE 3.

Funnel plots with pseudo 95% confidence limits of the pooled global prevalence of violence and stigmatization against healthcare workers during the COVID‐19 pandemic. (3.1) Stigmatization, all studies. (3.2) Violence, all studies. (3.2.1) Physical violence, when separately reported. (3.2.2) Verbal–emotional–psychological violence, when separately reported. (3.3) Outcomes by country's income level. (3.3.1) Low‐income countries. (3.3.2) Upper−/middle‐income countries.

Meta‐analysis

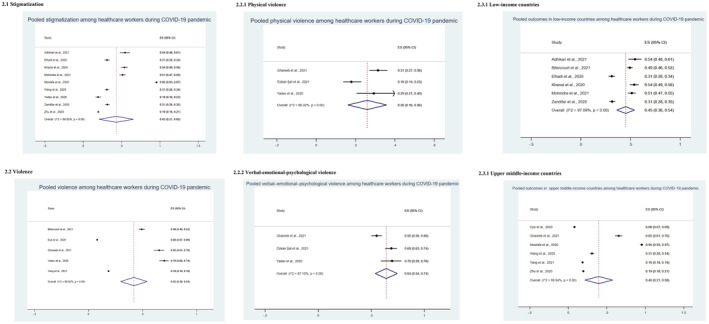

Global prevalence of stigmatization

The 9 studies that could be used to estimate the prevalence of stigmatization resulted in an estimate of 43% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 21% to 65%; Figure 2[2.1]). The I 2 for heterogeneity was 99.85% (p < 0.001), and the funnel plot is displayed in Figure 3[3.1]. The Egger regression test for small sample size was nonsignificant (t = 2.05, p = 0.079).

FIGURE 2.

Forest plots of the global prevalence of violence and stigmatization against healthcare workers during the COVID‐19 pandemic. (2.1) Stigmatization, all studies. (2.2) Violence, all studies. (2.2.1) Physical violence, when separately reported. (2.2.2) Verbal–emotional–psychological violence, when separately reported. (2.3) Outcomes by the country's income level. (2.3.1) Low‐income countries. (2.3.1) Upper‐middle‐income countries. ES, effect size; CI, confidence interval.

Global prevalence of violence

The 5 studies that could be used to estimate the prevalence of violence resulted in an estimate of 42% (95% CI: 30% to 54%; Figure 2[2.2]). The I 2 for heterogeneity was 99.82% (p < 0.001), and the funnel plot is displayed in Figure 3[3.2]. The Egger regression test for small sample size was nonsignificant (t = 2.14, p = 0.122). We also subdivided violence into physical violence and verbal–emotional–psychological violence. The prevalence of physical violence was estimated at 26% (95% CI: 16% to 36%; t = 2.36, p = 0.255; Figure 2[2.3]), and the prevalence of verbal–emotional–psychological violence was estimated at 64% (95% CI: 54% to 74%; t = 6.34, p = 0.100; Figure 2[2.4]).

Income classification of countries

We identified 7 studies that could be used to estimate the prevalence of stigmatization and violence against healthcare workers based on the country's income level. The pooled prevalence was 45% in low‐income countries (95% CI: 36% to 54%; t = 4.75, p = 0.009; Figure 2[2.5]) and 40% in the upper middle countries (95% CI: 21% to 58%; t = 1.19, p = 0.301; Figure 2[2.6]).

DISCUSSION

We found that almost half the professional healthcare workers studied experienced stigmatization and personally‐directed violence during the pandemic. That stigmatization and violence have affected the physical and psychosocial health of the workers. In low, middle, and high income countries, stigmatization and violence were proportionally balanced. In addition to their efforts to manage patients with COVID‐19 as frontliners, healthcare workers encountered additional stress in both their workplace and their social life. In this study, we concluded that insomnia, anxiety, and depression are the most common physical and psychosocial manifestations of stigmatization and workplace violence encounters. A previous meta‐analysis discovered that mental health problems are frequent among healthcare workers (Saragih et al., 2021). The increase in mental health problems among professionals practice appears to be linked to violence and stigma. For instance, stigmatized healthcare workers reported higher anxiety and depression (Khanal et al., 2020). Furthermore, healthcare workers who were the victims of violent attacks suffered from long‐term mental illness (i.e., post‐traumatic stress disorder) (Hilton et al., 2022).

More than one third of the analyzed studies revealed that healthcare workers faced physical violence (26%) and verbal–emotional–psychological violence (64%) in the healthcare institutions during the pandemic. That prevalence might be underestimated, because capturing all incidents through surveillance is difficult. Surveillance often captures only the high‐profile, high‐intensity attacks against international staff. Local healthcare workers might also be bearing the effects of violent attacks that are seldom reported (Devi, 2020). Those effects can include both lessened quality of life and less‐than‐optimal‐quality job performance and patient care (Devi, 2020; Shaikh et al., 2020; Xie et al., 2021). Healthcare professionals who had been subjected to violence were more likely to intend to leave (Nashwan et al., 2021; Özkan Şat et al., 2021).

Stigmatization affecting health providers in many countries worldwide arose both in the workplace and in the community, as well as from their own family members, which potentially added to mental exhaustion (Gualano et al., 2021; Zipf et al., 2021). Mental distress can affect healthcare workers for up to 3 years after an outbreak (Maunder et al., 2006). Perceived stigma was reported most often by frontliners—in particular, nurses, workers diagnosed with COVID‐19, women, married workers, and workers with lower educational qualifications (Dye et al., 2020; Kafle et al., 2021; Zandifar et al., 2020). Early interventions to support healthcare workers who have encountered stigmatization or personally directed violence and experienced related physical and psychological effects (e.g., anxiety, depression, stress, insomnia) are desperately needed. Timely support from the workplace is essential to prevent the exacerbation of physical and psychological effects that could lead to less‐than‐optimal work performance and quality patient care (Nowrouzi‐Kia et al., 2021).

We reviewed an equal number of studies from lower‐income countries (Adhikari et al., 2021; Bitencourt et al., 2021; Elhadi et al., 2020; Khanal et al., 2020; Mohindra et al., 2021; Yadav et al., 2020; Zandifar et al., 2020) and upper−/middle‐income countries (Dye et al., 2020; Ghareeb et al., 2021; Mostafa et al., 2020; Özkan Şat et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 2020). Stigma reported in the lower‐income countries was double that reported in upper−/middle‐income countries; in contrast, violence occurred more often in the upper−/middle‐income countries. Cénat et al. (2021) conducted a study in four lower‐middle‐income countries. Lack of education about COVID‐19 among the population in the lower‐middle‐income country and inadequate health system to provide care to sick patients are identified as two main reasons that intensify general public's misinformation about healthcare workers and stigmatization against healthcare workers (Cénat et al., 2021). Efforts from government and the public media to increase the public's view of COVID‐19 and its management could reduce stigmatization against healthcare workers (Bruns et al., 2020).

We also came to the conclusion that cultural influences influenced the stigmatizing behaviors and attitudes directed toward mental health professionals by members of the public. For example, East Asians are commonly known to endorse collectivist culture, and White Americans, to support individualist culture (Ran et al., 2021). The largest population in East Asians is Chinese, followed by Japanese and Korean (Pan & Xu, 2020). Pang et al. (2017) found that Chinese Singaporeans suffering from mental illnesses experienced a higher level of social distance and physical threat connected to the influence of collectivism. Another significant challenge in lower‐income countries is communication (Pang et al., 2017). Media are playing an essential role in information‐sharing. One of the primary causes for the rising stigma connected with COVID‐19 has been found is the use of unethical media (Bandara et al., 2020). Bruns et al. (2020) discovered that social media affected perceptions about the risk of diseases such as COVID‐19. Compared with the upper−/middle‐income countries, the lower‐income countries appeared to be more vulnerable and to experience more significant implications connected with COVID‐19 due to a greater reliance on social media for information and a weaker competence for fact‐checking (Hussain, 2020). Roelen et al. (2020) identified misinformation and misconceptions about COVID‐19 as the key driving factor of stigma in lower‐income countries, followed by fear of contagion and local health policies and priorities.

As with stigma, violence against healthcare workers is alarming such workers across the world. Violence against healthcare workers, for example, was common in China, ranging from 59.64% to 76.2% (Liu et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2021). Workplace violence in the upper−/middle‐income countries is also widespread, with the prevalence being 58.7% in North America and 31.6% in selected European countries (Yang et al., 2021). In terms of sorts of violence, verbal violence greatly outweighed physical violence. Verbal violence can result from poor verbal communication exchanges, possibly because, during the early days of the pandemic, frontline healthcare workers constantly faced an overwhelming workload and its related pressures, exacerbating their emotional disturbances and triggering unhelpful verbal disputes (Liu et al., 2018). That phenomenon is also commonly observed in the upper−/middle‐income countries, where the healthcare delivery workspace for treating confirmed and suspected COVID‐19 cases was crowded and chaotic. Addressing workplace violence in ways appropriate to workplace type and the local culture is a crucial priority concern in health policymaking (Varghese et al., 2021).

STUDY LIMITATIONS

While the current review contributes to the body of knowledge on estimating stigma and violence among healthcare workers during the pandemic, it has limitations. First, we did not examine the gray literature, and we only considered studies that were written in English. Consequently, other important research may have been left out in the screening process. Second, this review did not focus on the effects on patients and healthcare workers of stigmatization and violence against healthcare workers (e.g., worker turnover, medical errors, and adverse events during the delivery of patient care); such data were absent from all the included studies. Third, in the funnel plots, asymmetric outliers occurred, suggesting that the pooled results of the included studies had publication bias.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE TO CLINICAL PRACTICE

This study showed that about half the participating healthcare workers experienced personally directed stigmatization and violence during COVID‐19 pandemic. Such stigmatization and violence could have caused severe physical and psychosocial effects for those healthcare workers. Community stigmatization and workplace violence are more common among healthcare workers.

With respect to the practical implications of those review findings, stigmatization and violence against healthcare workers should be considered a public health and public safety priority concern in healthcare delivery settings and in the community—one that requires strategic planning that takes the specific workplace and local culture into account. Policymakers and administrators in healthcare settings and local governments should consider disseminating crisis management protocols to prevent the exacerbation of stigmatization and violence against healthcare workers during chaotic public health emergencies like the COVID‐19 pandemic. It does take a village to deal with stigmatization and violence given that both pertain to public health and public safety.

PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews

Registration number CRD42021271121.

CLINICAL RESOURCES

WHO Coronavirus (COVID‐19) Dashboard | WHO Coronavirus (COVID‐19) Dashboard With Vaccination Data

FUNDING INFORMATION

Not applicable.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

Supporting information

Supplementary S1

Supplementary S2

Saragih, I. D. , Tarihoran, D. E. T. , Rasool, A. , Saragih, I. S. , Tzeng, H‐M & Lin, C‐J (2022). Global prevalence of stigmatization and violence against healthcare workers during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 00, 1–10. 10.1111/jnu.12794

Akhtar Rasool, Sigma Theta Tau International Chapter: Phi Gamma Chapter

Huey‐Ming Tzeng, Sigma Theta Tau International Chapter: Alpha Delta Chapter

Contributor Information

Ita Daryanti Saragih, Email: itadaryanti05@gmail.com.

Chia‐Ju Lin, Email: chiaju@kmu.edu.tw.

REFERENCES

- Adhikari, S. P. , Rawal, N. , Shrestha, D. B. , Budhathoki, P. , Banmala, S. , Awal, S. , Bhandari, G. , Poudel, R. , & Parajuli, A. R. (2021). Prevalence of anxiety, depression, and perceived stigma in healthcare workers in Nepal during later phase of first wave of COVID‐19 pandemic: A web‐based cross‐sectional survey. Cureus, 13(6), e16037. 10.7759/cureus.16037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagcchi, S. (2020). Stigma during the COVID‐19 pandemic. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 20(7), 782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandara, G. , Thotawaththa, I. , & Ranasinghe, A. (2020). Ground realities of COVID‐19 in Sri Lanka: a public health experience on fear, stigma and the importance of improving professional skills among health care professionals. Sri Lanka Journal of Medicine, 29(1), 4–6. 10.4038/sljm.v29i1.173 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bitencourt, M. R. , Alarcão, A. C. J. , Silva, L. L. , Dutra, A. C. , Caruzzo, N. M. , Roszkowski, I. , Bitencourt, M. R. , Marques, V. D. , Pelloso, S. M. , & Carvalho, M. D. B. (2021). Predictors of violence against health professionals during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Brazil: A cross‐sectional study. PLoS One, 16(6), e0253398. 10.1371/journal.pone.0253398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruns, D. P. , Kraguljac, N. V. , & Bruns, T. R. (2020). COVID‐19: Facts, cultural considerations, and risk of stigmatization. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 31(4), 326–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buccheri, R. K. , & Sharifi, C. (2017). Critical appraisal tools and reporting guidelines for evidence‐based practice. Worldviews on Evidence‐Based Nursing, 14(6), 463–472. 10.1111/wvn.12258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cénat, J. M. , Dalexis, R. D. , Guerrier, M. , Noorishad, P. G. , Derivois, D. , Bukaka, J. , Birangui, J. P. , Adansikou, K. , Clorméus, L. A. , Kokou‐Kpolou, C. K. , Ndengeyingoma, A. , Sezibera, V. , Auguste, R. E. , & Rousseau, C. (2021). Frequency and correlates of anxiety symptoms during the COVID‐19 pandemic in low‐ and middle‐income countries: a multinational study. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 132, 13–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti, C. , Fontanesi, L. , Lanzara, R. , Rosa, I. , Doyle, R. L. , & Porcelli, P. (2021). Burnout status of italian healthcare workers during the first COVID‐19 pandemic peak period. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland), 9(5), 510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devi, S. (2020). COVID‐19 exacerbates violence against health workers. Lancet (London, England), 396(10252), 658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dye, T. D. , Alcantara, L. , Siddiqi, S. , Barbosu, M. , Sharma, S. , Panko, T. , & Pressman, E. (2020). Risk of COVID‐19‐related bullying, harassment and stigma among healthcare workers: an analytical cross‐sectional global study. BMJ Open, 10(12), e046620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhadi, M. , Msherghi, A. , Elgzairi, M. , Alhashimi, A. , Bouhuwaish, A. , Biala, M. , Abuelmeda, S. , Khel, S. , Khaled, A. , Alsoufi, A. , Elmabrouk, A. , Alshiteewi, F. B. , Alhadi, B. , Alhaddad, S. , Gaffaz, R. , Elmabrouk, O. , Hamed, T. B. , Alameen, H. , Zaid, A. , … Albakoush, A. (2020). Psychological status of healthcare workers during the civil war and COVID‐19 pandemic: A cross‐sectional study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 137, 110221. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghareeb, N. S. , El‐Shafei, D. A. , & Eladl, A. M. (2021). Workplace violence among healthcare workers during COVID‐19 pandemic in a Jordanian governmental hospital: The tip of the iceberg. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 1–9, 61441–61449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gualano, M. R. , Corradi, A. , Voglino, G. , Catozzi, D. , Olivero, E. , Corezzi, M. , Bert, F. , & Siliquini, R. (2021). Healthcare Workers' (HCWs) attitudes towards mandatory influenza vaccination: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Vaccine, 39(6), 901–914. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.12.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton, N. Z. , Addison, S. , Ham, E. N.,. C. R. , & Seto, M. C. (2022). Workplace violence and risk factors for PTSD among psychiatric nurses: Systematic review and directions for future research and practice. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 29(2), 186–203. 10.1111/jpm.12781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huedo‐Medina, T. B. , Sanchez‐Meca, J. , Marin‐Martinez, F. , & Botella, J. (2006). Assessing heterogeneity in meta‐analysis: Q statistic or I2 index? Psychological Methods, 11(2), 193–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, W. (2020). Role of social media in COVID‐19 pandemic. The International Journal of Frontier Sciences, 4(2), 59–60. 10.37978/tijfs.v4i2.144. Accessed on December 22, 2021 Available at:, https://publie.frontierscienceassociates.com/index.php/tijfs/article/view/144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joanna Briggs Institute . (2020). Critical appraisal tools: checklist for cohort studies. Accessed on December 22, 2021. Available at: https://jbi.global/critical‐appraisal‐tools

- Kafle, K. , Shrestha, D. B. , Baniya, A. , Lamichhane, S. , Shahi, M. , Gurung, B. , Tandan, P. , Ghimire, A. , & Budhathoki, P. (2021). Psychological distress among health service providers during COVID‐19 pandemic in Nepal. PLoS One, 16(2), e0246784. 10.1371/journal.pone.0246784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanal, P. , Devkota, N. , Dahal, M. , Paudel, K. , & Joshi, D. (2020). Mental health impacts among health workers during COVID‐19 in a low resource setting: a cross‐sectional survey from Nepal. Globalization and Health, 16(1), 89. 10.1186/s12992-020-00621-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. , Gan, Y. , Jiang, H. , Li, L. , Dwyer, R. , Lu, K. , Yan, S. , Sampson, O. , Xu, H. , Wang, C. , Zhu, Y. , Chang, Y. , Yang, Y. , Yang, T. , Chen, Y. , Song, F. , & Lu, Z. (2019). Prevalence of workplace violence against healthcare workers: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 76(12), 927–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W. , Zhao, S. , Shi, L. , Zhang, Z. , Liu, X. , Li, L. , Duan, X. , Li, G. , Lou, F. , Jia, X. , Fan, L. , Sun, T. , & Ni, X. (2018). Workplace violence, job satisfaction, burnout, perceived organisational support and their effects on turnover intention among Chinese nurses in tertiary hospitals: a cross‐sectional study. BMJ Open, 8(6), e019525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maunder, R. G. , Lancee, W. J. , Balderson, K. E. , Bennett, J. P. , Borgundvaag, B. , Evans, S. , Fernandes, C. M. , Goldbloom, D. S. , Gupta, M. , Hunter, J. J. , McGillis Hall, L. , Nagle, L. M. , Pain, C. , Peczeniuk, S. S. , Raymond, G. , Read, N. , Rourke, S. B. , Steinberg, R. J. , Stewart, T. E. , … Wasylenki, D. A. (2006). Long‐term psychological and occupational effects of providing hospital healthcare during SARS outbreak. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 12(12), 1924–1932. 10.3201/eid1212.060584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohindra, R. K. D. , Soni, R. K. , Suri, V. , Bhalla, A. , & Singh, S. M. (2021). The experience of social and emotional distancing among health care providers in the context of COVID‐19: A study from North India. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 31(1–4), 173–183. 10.1080/10911359.2020.1792385 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mostafa, A. , Sabry, W. , & Mostafa, N. S. (2020). COVID‐19‐related stigmatization among a sample of Egyptian healthcare workers. PLoS One, 15(12), 1–15. 10.1371/journal.pone.0244172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nashwan, A. J. , Abujaber, A. A. , Villar, R. C. , Nazarene, A. , Al‐Jabry, M. M. , & Fradelos, E. C. (2021). Comparing the Impact of COVID‐19 on Nurses' Turnover Intentions before and during the Pandemic in Qatar. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 11(6), 456. 10.3390/jpm11060456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowrouzi‐Kia, B. , Sithamparanathan, G. , Nadesar, N. , Gohar, B. , & Ott, M. (2021). Factors associated with work performance and mental health of healthcare workers during pandemics: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Public Health (Oxford, England), fdab173. Advance online publication. 10.1093/pubmed/fdab173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özkan Şat, S. , Akbaş, P. , & Yaman Sözbir, Ş. (2021). Nurses' exposure to violence and their professional commitment during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 30(13–14), 2036–2047. 10.1111/jocn.15760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page, M. J. , McKenzie, J. E. , Bossuyt, P. M. , Boutron, I. , Hoffmann, T. C. , Mulrow, C. D. , Shamseer, L. , Tetzlaff, J. M. , Akl, E. A. , Brennan, S. E. , Chou, R. , Glanville, J. , Grimshaw, J. M. , Hróbjartsson, A. , Lalu, M. M. , Li, T. , Loder, E. W. , Mayo‐Wilson, E. , McDonald, S. , … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 372, n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Z. , & Xu, S. (2020). Population genomics of East Asian ethnic groups. Hereditas, 157, 49. 10.1186/s41065-020-00162-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang, S. , Liu, J. , Mahesh, M. , Chua, B. Y. , Shahwan, S. , Lee, S. P. , Vaingankar, J. A. , Abdin, E. , Fung, D. , Chong, S. A. , & Subramaniam, M. (2017). Stigma among Singaporean youth: a cross‐sectional study on adolescent attitudes towards serious mental illness and social tolerance in a multiethnic population. BMJ Open, 7(10), e016432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ran, M. S. , Hall, B. J. , Su, T. T. , Prawira, B. , Breth‐Petersen, M. , Li, X. H. , & Zhang, T. M. (2021). Stigma of mental illness and cultural factors in Pacific Rim region: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 21(1), 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roelen, K. , Ackley, C. , Boyce, P. , Farina, N. , & Ripoll, S. (2020). COVID‐19 in LMICs: The need to place stigma front and centre to its response. The European Journal of Development Research, 32(5), 1592–1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saragih, I. D. , Tonapa, S. I. , Saragih, I. S. , Advani, S. , Batubara, S. O. , Suarilah, I. , & Lin, C.‐J. (2021). Global prevalence of mental health problems among healthcare workers during the Covid‐19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 121, 104002. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.104002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh, S. , Baig, L. A. , Hashmi, I. , Khan, M. , Jamali, S. , Khan, M. N. , Saleemi, M. A. , Zulfiqar, K. , Ehsan, S. , Yasir, I. , Haq, Z. U. , Mazharullah, L. , & Zaib, S. (2020). The magnitude and determinants of violence against healthcare workers in Pakistan. BMJ Global Health, 5(4), e002112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterne, J. A. C. , & Egger, M. (2001). Funnel plots for detecting bias in meta‐analysis: Guidelines on choice of axis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 54(10), 1046–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterne, J. A. C. , Gavaghan, D. , & Egger, M. (2000). Publication and related bias in meta‐analysis: Power of statistical tests and prevalence in the literature. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 53(11), 1119–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, P. , Wang, M. , Song, T. , Wu, Y. , Luo, J. , Chen, L. , & Yan, L. (2021). The psychological impact of COVID‐19 pandemic on health care workers: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 626547. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.626547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varghese, A. , Joseph, J. , Vijay, V. R. , Khakha, D. C. , Dhandapani, M. , Gigini, G. , & Kaimal, R. (2021). Prevalence and determinants of workplace violence among nurses in the South‐East Asian and Western Pacific Regions: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 31, 798–819. 10.1111/jocn.15987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W. , Lu, L. , Kelifa, M. M. , Yu, Y. , He, A. , Cao, N. , Zheng, S. , Yan, W. , & Yang, Y. (2020). Mental health problems in Chinese healthcare workers exposed to workplace violence during the COVID‐19 outbreak: A cross‐sectional study using propensity score matching analysis. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 13, 2827–2833. 10.2147/RMHP.S279170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . (2021). WHO coronavirus (COVID‐19) dashboard. Accessed on December 22, 2021. Available at https://covid19.who.int/

- Xie, X. M. , Zhao, Y. J. , An, F. R. , Zhang, Q. E. , Yu, H. Y. , Yuan, Z. , Cheung, T. , Ng, C. H. , & Xiang, Y. T. (2021). Workplace violence and its association with quality of life among mental health professionals in China during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 135, 289–293. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.01.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, K. , Laskar, A. R. , & Rasania, S. (2020). A study on stigma and apprehensions related to COVID‐19 among healthcare professionals in Delhi. International Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health, 7(11), 4547–4553. Accessed on December 22, 2021. https://www.ijcmph.com/index.php/ijcmph/article/view/7045 [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y. , Li, Y. , An, Y. , Zhao, Y. J. , Zhang, L. , Cheung, T. , Hall, B. J. , Ungvari, G. S. , An, F. R. , & Xiang, Y. T. (2021). Workplace violence against chinese frontline clinicians during the COVID‐19 pandemic and its associations with demographic and clinical characteristics and quality of life: A structural equation modeling investigation. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 649989. 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.649989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zandifar, A. , Badrfam, R. , Mohammadian Khonsari, N. , Mohammadi, M. R. , Asayesh, H. , & Qorbani, M. (2020). Prevalence and associated factors of posttraumatic stress symptoms and stigma among health care workers in contact with COVID‐19 patients. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry, 15(4), 340–350. 10.18502/ijps.v15i4.4303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z. , Xu, S. , Wang, H. , Liu, Z. , Wu, J. , Li, G. , Miao, J. , Zhang, C. , Yang, Y. , Sun, W. , Zhu, S. , Fan, Y. , Chen, Y. , Hu, J. , Liu, J. , & Wang, W. (2020). COVID‐19 in Wuhan: Sociodemographic characteristics and hospital support measures associated with the immediate psychological impact on healthcare workers. EClinicalMedicine, 24, 100443. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipf, A. L. , Polifroni, E. C. , & Beck, C. T. (2021). The experience of the nurse during the COVID‐19 pandemic: A global meta‐synthesis in the year of the nurse. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 54, 92–103. 10.1111/jnu.12706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary S1

Supplementary S2