Abstract

This paper empirically explores the impact of COVID‐19 pandemic and its accompanying lockdown on adolescent girls’ and women's access to sanitary pads in India. We have used the National Health Mission's Health Management Information System (NHM‐HMIS) data for the study, which provides data on pads' distribution on a district level. The empirical strategy used in the study exploits the variation of districts into red, orange, and green zones as announced by the Indian Government. To understand how lockdown severity impacts access to sanitary pads, we used a difference‐in‐difference (DID) empirical strategy to study sanitary pads' access in red and orange zones compared to green zones. We find clear evidence of the impact of lockdown intensity on the provision of sanitary pads, with districts with the strictest lockdown restrictions suffering the most. Our study highlights how sanitary pads distribution was overlooked during the pandemic, leaving girls and women vulnerable to managing their menstrual needs. Thus, there is a requirement for strong policy to focus on the need to keep sanitary pads as part of the essential goods to ensure the needs of the girls and women are met even in the midst of a pandemic, central to an inclusive response.

INTRODUCTION

The phenomenon of menstruation is a physiological one, experienced by adolescent girls and pre‐menopausal women every month (Biran et al., 2012). There is growing recognition of menstruation posing a barrier to health and gender equality in low and middle‐income countries (Sommer et al., 2017). Multiple studies focused on adolescent girls have highlighted how their menstrual experiences are coupled with feelings of discomfort, fear, and shame (Anand et al., 2015; Babbar et al., 2021; Dolan et al., 2014; Eijk et al., 2016; Goli et al., 2020; McMahon et al., 2011; Sommer, 2009). The negative experiences around menstruation have been linked to the lack of access to clean, reliable materials, supporting sanitation infrastructure, and information about menstruation (House et al., 2013; Sommer & Sahin, 2013).

The impact of experiencing menstruation without a proper structural environment on girls ranges from social, psychological and economic. It lowers women's sense of agency and leads to poor psychosocial outcomes, including lower self‐confidence, self‐esteem, confidence (Eijk et al., 2016; Phillips‐Howard et al., 2016; Sivakami et al., 2019). The economic impact includes lowered participation of girls and women in schools and offices and is also associated with poor health outcomes, including urinary tract infections (UTIs) and reproductive tract infections (RTIs) (Almeida‐Velasco & Sivakami, 2019; Anand et al., 2015; Eijk et al., 2016; Traylor et al., 2020). Given the wide‐ranging impact of the inadequate resources for menstruation, it is crucial to address these needs of girls and women, especially during the pandemic.

There is rising evidence of COVID 19 affecting girls and women disproportionately (UN Women, 2020a) as compard to men. Our study focuses on access to sanitary pads during the ongoing pandemic, which has widely been acknowledged to be a concern (BBC, 2020; PLAN International, 2020). The concerns around the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic and lockdown on access to sanitary pads have mostly been based on media reports. Little is known about changes in the magnitude of access and availability of sanitary pads during the COVID 19 pandemic and lockdowns. We study India's scenario, where only 57% of women use sanitary items including local and commercial sanitary pads, tampons in the pre‐COVID times, while the rest use old cloth, rags, husk, or ash (IIPS and Macro International, 2017). Adolescent girls in India end up missing 1–2 days of school each month (DASRA, 2015), and 52% of the girls are not aware of menstruation pre‐menarche (Eijk et al., 2016).

Menstrual hygiene management and crisis situations

Menstrual hygiene management (MHM) is defined as “women and adolescent girls using a clean menstrual management material to absorb or collect blood that can be changed in privacy as often as necessary for the duration of the menstruation period, using soap and water for washing the body as required, and having access to facilities to dispose of used menstrual management materials” (Budhathoki et al., 2018). Women and girls often use sanitary pads to absorb menstrual blood, required for facilitating personal hygiene. Different absorbents are used for managing menstrual needs in low‐income countries, including Nepal, ranging from reusable cloths to commercially available disposable sanitary napkins (Sebastian et al., 2013).

Despite the absolute necessity, not everyone can afford sanitary pads, and it is a ubiquitous problem, also known as ‘period poverty i ,’ which becomes even more severe in emergency and humanitarian contexts (VanLeeuwen & Torondel, 2018). For example, in 2015, Nepal's earthquake‐affected 1.4 million girls and women (Chaudhary et al., 2017). Sanitary pads were of the highest priority for girls and women. However, none of them reported receiving any sanitary pads during the first‐month post the earthquake (Budhathoki et al., 2018). Similar instances were seen in Uganda, where girls and women living in refugee settlements for decades had to rely on the government for daily rations. They had to cover long distances to get their daily rations. Girls and women have reported difficulties in covering these long distances while menstruating as they end up staining themselves. Instances have also been recorded of women having to sell their food rations to purchase sanitary pads (CARE International in Uganda CARE International in Uganda Annual Report, 2018).

COVID‐19 induced lockdowns, similar to other emergencies/humanitarian crises, have led to many issues for those who menstruate as periods do not stop during a pandemic, yet managing them becomes problematic. The pandemic has seen girls and women resorting to using socks and old newspapers during menstruation times as sanitary items became either expensive or harder to procure (Xiao & Darmadi, 2020). The ongoing economic crisis resulting from the pandemic has put many girls and women into period poverty, thus posing multiple health risks, including RTIs, UTIs, and others (PLAN International, 2020). Around 20% of the girls and women surveyed in the PLAN International Report reported an increase in the price of sanitary items. The same survey also reveals a limited supply of sanitary items due to COVID‐19 lockdowns and the closure of state borders across 30 countries. An online survey conducted where (PLAN International, 2020) professionals from 24 countries across the Asia Pacific, Africa, Latin America, Europe, and North America were interviewed found that “81% were concerned people who menstruate would not be supported to meet their MHM needs” (p.3). According to the report, 73% of the participants were also concerned about restricting access to sanitary items resulting from shortages or disruption in supply chains. Another concern raised by the majority of the participants related to an increase and prohibitive rise in the prices of sanitary items. In the current pandemic, it is of utmost importance that the MHM's impact is understood, given the challenges faced by girls and women menstruating.

Menstrual hygiene scheme for adolescent girls

The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare launched the Menstrual Hygiene Scheme to promote menstrual health and hygiene among adolescent girls in the age group of 10–19 as a part of their adolescent reproductive sexual health (ARSH) to ensure good health and hygiene for the girls. The objective of this scheme was three‐fold (a) to increase menstrual awareness among adolescent girls, (b) to increase access and usage of sanitary pads for the adolescent girls, and (c) to ensure safe disposal of sanitary pads to promote a friendly environment.

Steps were taken at the community and school level to ensure a regular supply of sanitary pads (Menstrual Hygiene Scheme (MHS): National Health Mission, n.d.). Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) workers distribute the pads at the school level under the Adolescent Education Program (AEP) or School Health Program. ASHA workers will also be responsible for maintaining the supply in the community. These pads were sold to the adolescent girls for Rs 6 for six sanitary pads by ASHA workers through the door‐to‐door sale. ASHA workers receive Rs 1 per pack as an incentive and a free pack of sanitary pads per month. In our study, we focus on the impact of the pandemic and ensuing lockdown on access to sanitary pads (distribution and sales) for adolescent girls and ASHA workers in the Indian context.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data on lockdown zones in India

A nation‐wide lockdown was imposed in India for 21 days starting on March 25, which limited 1.3 billion people's movement, as a preventive measure to stop the spread of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Due to the growing number of COVID‐19 infections, the lockdown was further extended in three additional phases from April 15 to May 3, May 4 to May 17, and May 18 to May 31 (Press Trust of India, 2020). In the third phase, starting from May 4, 2020, the Ministry of Home Affairs and the Government of India divided the country into three zones, that is, red, orange, and green zones, based on the number of COVID‐19 cases in these zones (Ministry of Home Affairs, 2020). The zone classification remained the same for these 83 districts till the lockdown was lifted. Zones with a “significant risk of spread of COVID‐19 infection” were classified as red zones, whereas zones with “zero or no confirmed cases of COVID‐19 infection in the past 21 days” were classified as green zones, and those in between were classified as orange zones. April and May have been taken as the treatment months since the lockdown announcement was made just before April's end and continued until May.

Health Secretary of India, Preeti Sudan, said, “This classification is multi‐factorial and considers incidence of cases, doubling rate, the extent of testing and surveillance feedback to classify the districts” (Thacker, 2020).

We next discuss the implications of zonal classification on individual movement and the production/transportation of goods. Red zones were under complete lockdown. Even basic transportation, including bicycles, taxi cabs, and autorickshaws along with buses plying on intra‐district or inter‐district routes or any other form of public transport, was prohibited. The only exception was for four‐wheeler vehicles with a driver accompanied by two passengers and for two‐wheeler vehicles not carrying a pillion rider. In the urban areas, special economic zones (SEZs), Export Oriented Units (EOUs), industrial estates and industrial townships with access control, manufacturing units of essential goods, and packaging materials, were given consent to continue with their operations. All the standalone shops, and e‐commerce sites for essential services, were allowed to operate. In orange zones, only cabs and taxis with a driver and two passengers, were allowed to operate. Inter‐district movement of individuals and vehicles could resume but only for permitted activities. In green zones, public transport (buses) movement was allowed at 50% occupancy. Bus Depots could also function at a maximum of 50% occupancy. Additionally, all States and Union Territories were permitted inter‐state movement of goods/cargo. The economic activities that could resume in the red zones, including SEZs, manufacturing plants for essential items, and others, were also granted authorization to operate in the orange and green zones. Out of the 83 districts in our data, 17 districts were identified in the red zone, 38 districts in the orange zone and 28 districts in the green zone.

Sanitary pads distribution for adolescent girls

National Health Mission's Health Management Information System (NHM‐MIS) serves as the primary database for this study. It is an established data source for Reproductive, Maternal, neonatal, and Child Health (RMNCH). NHM‐HMIS was put into the system in October 2008 by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare and the Government of India to monitor the National Health mission and leverage it to collect evidence for local planning and policy level decision making. NHM‐HMIS tracks data on various health services indicators, including Ante Natal Care (ANC), family planning, adolescent health, and other health services over 200,000 government‐run health facilities. For this study, we use NHM‐HMIS provided data on the number of adolescent girls provided sanitary pad packs, the number of sanitary pads sold to the adolescent girls, and the number of sanitary pad packs distributed free to ASHA workers across various districts and sub‐district levels.

Health Management Information System was reported as having several issues in the 90s citing multiple problems (Kumar, 1993). These problems included incomplete records and over‐reporting of the final outcomes of health (Pandey & Mishra, 2010). To improve the data quality, Health, Finance, and Governance (HFG) trained the government officials in Punjab and Haryana. HFG helped them conduct two rounds of data quality assessment (Improving Health Data Quality in India's Haryana and Punjab States | HFG, n.d.). Sharma et al. (2016) have also shown that records for NHM‐HMIS are satisfactory. In a similar effort, the World Bank supported the Tamil Nadu government in preparing a paperless health system to provide real‐time data, thus improving the data quality (Govindaraj, 2016). Punjab has also developed a similar system, and these GIS‐enabled HMIS applications were considered an indicator of the improvement in the data quality (Kurian, 2016). The improved data quality was evident as multiple researchers and international organizations of repute like the World Bank and Niti Aayog have used this dataset to understand the relationship among various health indicators (Aayog et al., 2019; Salve et al., 2020).

We use the NHM‐HMIS database to retrieve the numbers for sanitary pads distributed to adolescent girls from January to May 2020. The data was available for 83 districts across 11 states from January 2020 to May 2020, which became our study's final sample. The data on the sanitary pads has been combined with the data from the Ministry of Home Affairs, India, about the lockdown zone categories across various districts. We use a Difference in Difference (DID) technique with a view to establish a relationship between lockdown intensity and provision of sanitary pads. The DID approach allows us to isolate the impact of government policy (lockdown intensity) on distribution of sanitary products. There is an expected effect of the lockdown on supplies of various goods but the differential impact by lockdown intensity is essential to investigate. The objective of the study is to investigate whether the impact was larger on red/orange zones than on green zones. If this is indeed the case, then it is an important lesson for policy to ensure equitable distribution of sanitary products across regions as it did for other products.

Girls and women use different sanitary items, including traditional methods, sanitary pads, menstrual cups, and tampons to manage their menstrual needs (IIPS and Macro International, 2020). Only a small subset of them uses sanitary pads to manage their menstrual needs. Our sample includes the data on sanitary pads distributed directly to adolescent girls and those distributed to ASHA workers. It is pertinent to keep in mind that our data only addresses access of adolescent girls and not all those who menstruate. Even among adolescent girls, many do not study in government schools and may not have access to these free/subsidized pads. However, the scheme and its outcomes are vital to study since it targets the most vulnerable population within those who menstruate. It was started for adolescent girls belonging to disadvantaged groups and the ones coming from rural areas. To that effect, our study in fact, highlights the change in access of menstrual products for the most disadvantaged girls.

Pre‐trends

Before we present our main results, we ensure that districts which were classified as Red and Orange did not differ along the lines of sanitary pad distribution compared to Green districts. We analyze these trends in pre‐lockdown outcomes for January 2020 to March 2020. We regress the below mentioned standard specification to check for pre‐trends:

| (1) |

The dependent variable Ydm refers to the sanitary pad distribution to the adolescent girls in the district' d', in the month 'm’. The variables Redd and Oranged are indicator variables taking value 1 if the district is classified as red/orange, respectively while Monthm is an indicator for the mth month in the pre‐lockdown time. If the parallel trends assumption holds true, then, β1m and β2m should be null and statistically insignificant for each month ‘m’ in the pre‐lockdown time.

Empirical strategy

Our study uses a robust strategy to exploit the temporal and spatial variation in exploring the impact of lockdown policy on adolescent girls' sanitary pads' distribution. We exploit pre versus post‐COVID lockdown temporal variation coupled with government‐mandated spatial variation intensity of the lockdown classified, which classified districts into red, orange, and green zones. This strategy enables us to treat the variation across the 83 districts of 11 states in India as quasi‐random. The variation in the lockdown intensity and the availability of pre‐ and post‐lockdown data allows us to use a difference‐in‐difference (DID) design to understand if the impact on the sanitary pads' distribution was more severe in districts with the strictest lockdown measures in comparison to the districts with the least stringent lockdown measures. Our final data has a panel structure with information regarding the distribution of sanitary pads and lockdown intensity in each district over across January to May 2020. We run the following specification using district fixed effects and clustering the standard errors at the state level:

| (2) |

Our dependent variable is Ydm which refers to the sanitary pad distribution to the adolescent girls in the state ‘s’, district' d', in the month ‘m’. Lockdownm is a binary variable with a value of “1” for months April and May and “0” for January to March. Redd (Oranged) is the district level categorical variable which values 1 for districts in red (orange) zones and 0 otherwise. To allow for differences by district we include γd which captures any district level fixed effects. Using fixed effects at the district level allows us to capture any time‐invariant characteristics of districts related to sanitary pad distribution. The error term εdm is clustered at the state level. In 2014, under their National Health Mission, the Indian government started providing funds to the States and Union Territories for decentralized procurement of sanitary napkin packs (Menstrual Hygiene Scheme (MHS): National Health Mission, n.d.). Thus, every state has a different pad distribution policy, hence, clustering was done at the state level.

Note that α1 captures the impact of lockdown on the sanitary pad distribution in the month ‘m’ (April and May) compared to the monthly average from January to March 2020 (the omitted months). The coefficients α2o and α2r capture the difference in sanitary pad distribution in red and orange zones respectively relative to the green zone (the omitted zone) districts. Our variables of interest are α3o and α3r which capture the differential impact of the sanitary pad distribution across the orange and red zones relative to the green zone before and after the lockdown in April and May relative to the monthly average from January 2020 to March 2020.

Robustness checks

Multiple robustness checks were conducted to confirm the main results of the impact of the zone‐wise lockdown policies on the sanitary pad distribution.

First, we conducted robustness check using Equation (2) with the outcomes variable as pads sold to the adolescent girls and pads distributed to the ASHA workers. Next, we checked the differential impact of the lockdown and zones categories on the sanitary pads sold to the adolescent girls and sanitary pads distributed to the ASHA workers to confirm the consistency of our results.

Additionally, for addressing the potential concern that the number of pads maybe reduced due to the poor economic activity in the areas with the highest number of COVID‐19 infections, that is, red and orange zones, we re‐estimated Equation (2) after controlling for the district‐wise data of the COVID‐19 cases (Ravindran & Shah, 2020).

Another potential concern was that of data entry errors, as the data was collected during lockdown. To address this concern, we winsorize the sanitary pads data (including sanitary pads distributed, sanitary pads sold and sanitary pads given to the ASHA workers) such that the distribution of the raw data is considered only between the 5th and 95th percentile.

RESULTS

Descriptive results

We first present the descriptive statistics associated with the sanitary pad distribution to adolescent girls. Table 1 shows the mean and standard deviation of the sanitary pads distributed to adolescent girls from January 2020 to May 2020 across different zones. Table 2 shows the sanitary pads distribution to the adolescent girls across the three zones and lockdown.

TABLE 1.

Pads distributed to adolescent girls across various zones from January to May 2020

| Red zone | Orange zone | Green zone | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev | |

| January | 20888 | 16895 | 25478 | 27480 | 14703 | 35552 |

| February | 18137 | 13431 | 28485 | 30287 | 15124 | 34632 |

| March | 48597 | 128741 | 23199 | 27955 | 6629 | 9380 |

| April | 11944 | 13842 | 17814 | 20884 | 5776 | 8860 |

| May | 9791 | 11215 | 18223 | 22689 | 9400 | 16999 |

TABLE 2.

Average pads distributed across various zones before and during the lockdown

| Pads given | Pads sold | Pads ASHA | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Red zone | Orange zone | Green zone | Red zone | Orange zone | Green zone | Red zone | Orange zone | Green zone | |

| Pre‐lockdown | 28981.8 | 25716 | 12292 | 17278 | 37380 | 14584 | 1335 | 5567.4 | 766.09 |

| Lockdown | 13683.6 | 19864 | 8423.2 | 8940.2 | 31024 | 9256.3 | 853 | 4018.9 | 723.84 |

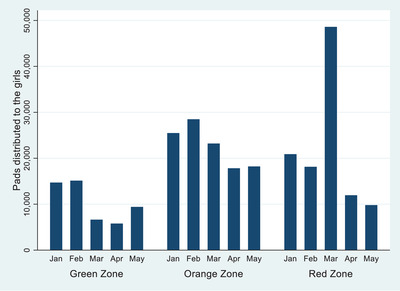

We found some interesting results from looking at the averages by month, as shown in Figure 1 and Table 1. India officially entered the lockdown in March and impact of the lockdown can be seen in April and May for all zones. We saw a decline in sanitary pads distribution by 53%, 23%, and 32% in the red, orange, and green zones during the lockdown compared to the pre‐lockdown period.

FIGURE 1.

Sanitary pads distributed to adolescent girls across zones from January to May 2020 [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

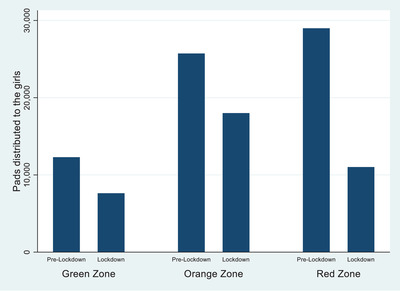

Thirdly, the sanitary pads distribution started increasing in May compared to April in the orange and green zones; however, it dipped further in the red zone. We aggregate the above data to understand the trends before and during the lockdown in Figure 2 and Table 2. As seen in Figure 2, the sanitary pads distribution decreased by 52% in the red zones during the lockdown. It reduced by 23% and 33% in the orange and green zones, respectively.

FIGURE 2.

Sanitary pads distributed to the adolescent girls across zones and lockdown [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

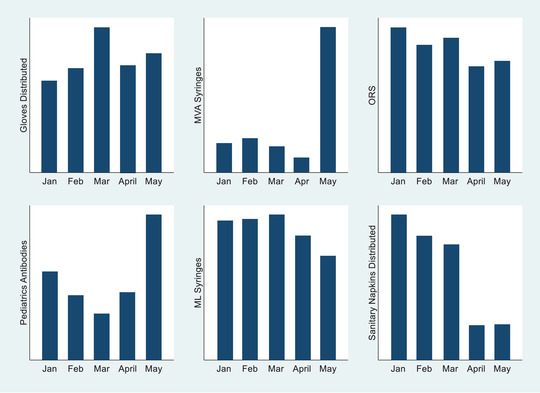

To understand if the trends we observe are specific to sanitary pads or the trends were similar to that for other products, we further looked at the aggregate data for other items in the NHM‐HMIS. Figure 3 shows data on other items at the monthly level aggregated at the all‐India level. We found that various transportable items like gloves, syringes, ORS, and other antibiotics remained similar or showed a small decrease in April and May. In contrast, sanitary pad distribution showed a colossal dip during the same months. All these items are transferred via various distribution channels. The dip in the sanitary napkin distribution is the highest, showing Government's low priority on the sanitary pad distribution.

FIGURE 3.

Various items distributed across India [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

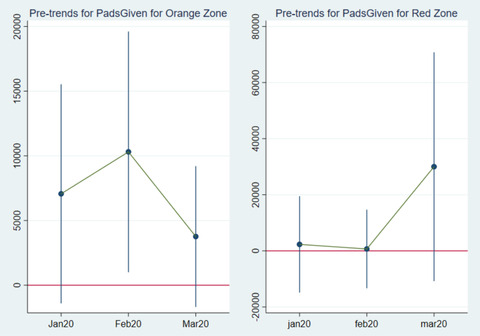

Results for pre‐trends

Figure 4 shows the monthly estimates from Equation (2) for the red and orange zones in the pre‐lockdown period from January 2020 to March 2020. Most of the coefficients are null and statistically indistinguishable from zero, indicating that the parallel trends assumption holds true for our study.

FIGURE 4.

Pre‐trends for pads distributed to the adolescent girls for red and orange zones [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Differential impact of lockdown and zones on sanitary pad distribution

Table 4 reports the results from Equation (1), a combination of (a) temporal variations of the pre‐and post‐lockdown (b) spatial variations in the lockdown intensity across the red, orange, and green zones. Column (1) of Table 3 shows the results for sanitary pads distributed to adolescent girls from January to May. We find a strong effect of the lockdown itself with Sanitary Pads distribution dropping by 2,614,866 (70%) units at the all‐India level during the lockdown for all zones. In general, the coefficients of the zones highlight that sanitary pad distribution was higher in orange and red zones, respectively, compared to green zones. Our variable of interest is the interaction between lockdowns and zones, which shows the differential impact of the lockdown across various zones on the sanitary item distribution. The interaction of the lockdown with red and orange zones is negative and significant. It shows that the sanitary pad distribution in the red and orange zone is lower than in the green zone during the lockdown after controlling for the pre‐lockdown levels. The results show the negative impact of lockdown on the sanitary pad distribution and how this impact was highest in red zones, followed by orange and green zones.

TABLE 4.

Differential impact of lockdown and zone on the sanitary pads distribution after controlling for COVID‐19 cases

| Pads given | Pads sold | Pads asha | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Lockdown | −4661.82* | −6333.79* | −102.97* |

| Zone | |||

| Orange zone | 16227.83*** | 15311.79*** | 1533.44*** |

| Red zone | 20530.86*** | 22195.32*** | 1399.72*** |

| Lockdown*zone | |||

| Lockdown*orange zone | −4397.04** | −1471.90 | −714.45 |

| Lockdown*red zone | −11504.83** | −4422.10 | −515.82*** |

| Constant | 11577.21*** | 11732*** | 126.14*** |

| Number of observations | 373 | 277 | 262 |

| Number of groups | 83 | 64 | 62 |

***p<.01, **p<.05, and *p<.1.

TABLE 3.

Differential impact of lockdown and zone on the sanitary pads distribution

| Pads given | Pads sold | Pads Asha | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Lockdown | −4624.57* | −6311.10* | −101.1 |

| Zone | |||

| Orange zone | 16247.45*** | 15317.68*** | 1534.33*** |

| Red zone | 20289.06*** | 22060.86*** | 1385.02*** |

| Lockdown*zone | |||

| Lockdown*orange zone | −4335.12** | −1445.09 | −711.99 |

| Lockdown*red zone | −10411.57* | −3844.35 | −451.8*** |

| Constant | 11565.23*** | 11732*** | 125.70*** |

| Number of observations | 373 | 277 | 262 |

| Number of groups | 83 | 64 | 62 |

***p<.01, **p<.05, and *p<.1.

Robustness checks

First, we see the impact of the zonal lockdown policies on the sanitary pads (a) sold to the adolescent girls (b) distributed free to the ASHA women. Column (2)–(3) of Table 3 shows the differential impact of the lockdown across various zones on the sanitary pads sold to the adolescent girls and sanitary pads distributed to the ASHA workers from January to May. Sanitary pad sales and distribution dropped during the lockdown. Sanitary pad distribution and sales were higher in orange and red zones than in green zones during the whole period.

The interaction of the lockdown with red and orange zones is negative. It shows that the sanitary pad sold to the adolescent girls in the red and orange zone dropped during the lockdown. However, our results are not statistically significant. Hence, we can say that we did not see the differential impact for the sanitary pads sold to adolescent girls during May.

The differential impact of the zone and lockdown for the sanitary pads distributed to the ASHA workers is negative for the lockdown months. Thus, it shows that sanitary pads distributed to the ASHA workers dropped significantly during the lockdown in the red and orange zones compared to the green zone. Thus, there was a negative impact of lockdown on the sanitary pad distribution, and this impact was highest in red zones followed by orange zones. Combing these findings, we found that sanitary pads distribution reduced significantly during the lockdown in the orange and red zones, as compared to the green zones.

Second, we report the results for the impact of the zonal lockdown policies on the sanitary pads distribution after controlling for the monthly number of the COVID‐19 infections, as shown in Column (1)–(3) of Table 4. We found that our main results are qualitatively consistent with those reported in the Column (1) of Table 3, suggesting that our final results are not driven by the loss of the economic activity due to higher number of COVID‐19 infections across zones.

Third, we report the differential impact of the lockdown and zones after excluding the outliers, as shown in Table 5. We found that our main results are qualitatively consistent with those reported in Columns (1)–(3) of Table 3. As a result of these analyzes, the robustness of the findings can be established.

TABLE 5.

Differential impact of lockdown and zones on sanitary pads distribution after excluding the outliers

| Pads given | Pads sold | Pads Asha | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Lockdown | −2191.82 | −3026.34 | −106.59* |

| Zone | |||

| Orange zone | 16743.5*** | 15185.26*** | 1365.01*** |

| Red zone | 19637.39*** | 21726.86*** | 1334.73*** |

| Lockdown*zone | |||

| Lockdown*orange zone | −5575.25** | −4398.81 | −287.76 |

| Lockdown*red zone | −6344.75*** | −7083.11*** | −252.47*** |

| Constant | 10591.80*** | 11732*** | 127.53*** |

| Number of observations | 373 | 277 | 262 |

| Number of groups | 83 | 64 | 62 |

***p<.01, **p<.05, and *p<.1.

DISCUSSION

COVID‐19 has disrupted the daily lives of people worldwide, especially girls and women. It has exacerbated the existing gender inequalities with significant challenges for girls and women (Chauhan, 2020). Within the domain of health and hygiene, it has been women facing the brunt of the lockdown (UN Women, 2020b). Last year's World Menstrual Hygiene Day theme was “Periods in Pandemic,” which powerfully conveyed the message that periods do not stop in pandemics and emphasized the urgency to address the menstrual needs of millions of women and girls across the world. Motivated by this theme, our study attempts to understand the impact of the government mandated lockdown across various zones on the sanitary pad distribution by the government among adolescent girls and women across 83 districts in 11 states of India.

We contribute to the growing body of evidence worldwide on the impact of the lockdown on sanitary item distribution during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Our identification strategy builds on (a) pre and post lockdown, i.e. temporal variation and, (b) government's classification of spatial variation in the intensity of the lockdown across districts into red, orange and green zones. This provides us quasi‐random variation in the lockdown intensity across India. Second, we also contribute to the literature on sanitary item distribution during emergency. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to understand the impact of the lockdown on the sanitary item distribution during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Indian government containment policies have been much debated around the world and findings of this study are relevant to policy making, especially for emergency situation response.

Using a DID estimation strategy, we find evidence of a 53% decrease in sanitary items distributed to the adolescent girls during the lockdown in the districts that saw the strictest measures (red zone) relative to the districts that saw the least stringent measures (green zone). Similarly, we found a 23% decrease in sanitary items distributed to the adolescent girls during the lockdown in the orange zone districts relative to the districts in the green zones. Our findings substantiate anecdotal evidence from various media reports which showed a colossal dip in the sanitary pad distribution during the COVID‐19 pandemic across India (BBC, 2020; Edwin, 2020) and highlight the plight of girls and women who rely on humanitarian settings to receive sanitary items which are severely disrupted during the health emergencies like COVID‐19 (Fuhrman et al., 2020).

In 2014, under their National Health Mission, the Indian government started providing funds to the States and Union Territories for decentralized procurement of the sanitary napkin packs (Menstrual Hygiene Scheme [MHS]: National Health Mission, n.d.). Community Health workers who are usually allocated for the sanitary items supply (like ASHA workers in India) were reallocated to carry out various community‐level activities, including tracking the patients who tested positive for COVID‐19, monitoring people with travel history, and others (Singh et al., 2020). It is not only the disruption of supply from government sources but the closure of private shops due to lockdown which hinders the availability and accessibility of sanitary napkins.

In addition to the distribution constraints listed above, the treatment of sanitary napkins as a non‐essential item in India and the associated delays in production also contributed to the shortage of sanitary pads (Mendoza, 2020). Four days after the nationwide lockdown was announced, sanitary napkins were added to the government's list of essential items. It has been documented that even after the inclusion of sanitary napkins as part of essential items, the delay in production and distribution continued in India (Singh, 2020). The delay caused by later addition to the list was further compounded by a delay caused by the administrative procedures for getting the required permits (BBC, 2020). Adding to the delay in production, workers having migrated back to their hometowns (Rajan et al., 2020), causing a shortage of labour, contributed to only partial utilization of production capacity.

With the schools shut down, supplies of free sanitary pads by the government have come to a halt. At the same time production delays and supply chain disruptions have reduced access to sanitary napkins from private sources. These factors have forced adolescent girls to look for alternative options, including cloths and rags (Kapoor, 2020; Mishra & Jaiswal, 2020). The physical impact has been felt by many girls who developed serious infections and faced heavy and erratic bleeding (Kapoor, 2020).

Our study emphasizes the need for governments to invest in providing access to sanitary items through public and private channels as the first line of defence in fighting public health emergencies. Governments must ensure that access to sanitary products should not be hindered or fail during the emergencies like floods, earthquakes, or in the current case, a pandemic. Additionally, information on making, using and maintaining homemade pads should also be provided to the girls and women if they are unable to access sanitary items. The government and policymakers should remove the taxes on sanitary items and ensure that sanitary items are considered an essential item to be made available through distribution channels during emergencies situations, as a part of the sexual and reproductive emergency health package.

To be prepared for future emergencies, government and policymakers can (a) procure the sanitary items in sufficient quantity, (b) consider improving the absorbency of the pads, which are safe to be changed less frequently, (c) ensure that sanitary items are a part of essential commodity list, thus, removing barriers from the production and supply of the sanitary items, (d) encourage the manufacturers (by providing incentives, tax‐benefits and other benefits) in similar industries to consider manufacturing or distributing sanitary items to meet the increased demand, (e) improving the public health communication by including information around menstrual health and hygiene, in addition, to the information around handwashing, and (f) improving the local supply chains by tying up with the local NGOs, ASHA and other frontline health workers, and other local partners to ensure that we reach out to the most vulnerable population.

COVID‐19 has exacerbated the existing silence around menstruation, and thus, it is crucial to raise awareness and break the negative social norms around menstruation (Babbar, 2021). It can be done by integrating MHM into offline and online learning curriculums. Lessons from previous disaster scenarios documenting the lived experiences of women show have shown managing menstruation as challenging (Budhathoki et al., 2018). Meeting menstrual needs adequately is not only specific to girls and women of reproductive age, but managing periods in a satisfactory manner is a basic public health and human rights issue (Babbar et al., 2022). The requirement of every government's emergency health response to be inclusive of managing menstruation needs during the pandemic has paramount importance. This is not only limited to including information on menstruation distributed as part of a package of health information but also campaigns addressing period stigma and working closely with Ministries of Health and Education for ensuring recovery responses consist of MHM. In addition, the supply of sanitary products can be augmented by supporting local small businesses and microenterprises to match demand and reduction in reliance on global supply chains. Apart from these steps, there is also a requirement for more robust policies to strengthen the existing sanitary pads distribution schemes.

LIMITATIONS

There is minimal literature on menstruation during an emergency. It is a relatively growing area of interest for scholars in the education, health, and other socially aligned areas. Our paper is limited to the impact of the lockdown on the distribution of low‐cost sanitary pads to the girls and women and doesn't offer insights and experiences of the women and girls using these pads. Second, the assessment is limited to the 83 districts of 11 states, thus, limiting the external validity of the study. Third, the study uses data from NHM‐HMIS system, which was collected during lockdown. Thus, it may be possible that the severity of the pandemic could have impacted recordkeeping in the red districts as compared to the green districts. Fourth, the data in this study is limited to sanitary pads and does not include other sanitary items like menstrual cups, tampons etc. Thus, our final results may under‐represent the usage of the period products. Lastly, our analysis is limited to the sanitary pads distributed to girls and women and does not include data for trans and non‐binary individuals who menstruate, due to lack of data. Even with these limitations, this is the first study to demonstrate the impact of the COVID‐19 lockdown on the sanitary pad distribution in India.

CONCLUSION

During the ongoing pandemic, girls' and women's access to sanitary items has been hindered, worsening the pre‐existing period poverty. Covid‐19 has exposed the fragility of health services across the world. Lack of timely access to sanitary items risks the lives of adolescent girls and women from reproductive infections, UTIs, anaemia, and poor mental health. The current pandemic has undone previous interventions for improving menstrual health and access to sanitary items. They will be unable to compensate for the “zero or limited” interventions due to the pandemic. Thus now, more than ever, a renewed focus from individuals and governments is required to rapidly respond to ever‐evolving challenges to menstrual health and address the needs of girls and women.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

STATEMENT

We have used secondary data from National Health Mission, Health Management Information System (NHM‐HMIS) to conduct this study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Authors did not receive any funding for the study.

Biographies

Karan Babbar is an Assistant Professor at Jindal Global Business School. He works on the intersection of education and health focusing on gender and his research interests includes Menstrual Health and Hygiene, LGBTQ Issues, Domestic Violence and Women's Empowerment, and Health and Sanitation.

Niharika Rustagi is a PhD student at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore. Her key research interests relate to gender and development. The methodological approaches she uses are quantitative analysis, qualitative inquiry and policy impact evaluation using both primary and secondary data.

Pritha Dev is an Associate Professor with the Economics area at the Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad. Her research and teaching interests are at the intersection of game theory, economics of networks, gender and experimental economics.

Babbar, K. , Rustagi, N. & Dev, P. (2022) How COVID‐19 lockdown has impacted the sanitary pads distribution among adolescent girls and women in India. Journal of Social Issues, 00 1–18. 10.1111/josi.12533

NOTE

“Period poverty” is defined as the inability to afford the sanitary items including sanitary napkins, tampons, menstrual cups and others to manage their menstrual needs. Girls and women end up using old clothes, toilet papers, paper towels. In addition to the lack of sanitary items, it also incorporates the lack of water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) facilities (Babbar et al., 2021).

REFERENCES

- Aayog, N. , The World Bank, & Ministry of Health and Family Welfare . (2019). Healthy states progressive India report on the ranks of states and union territories health index.

- Almeida‐Velasco, A. & Sivakami, M. (2019) Menstrual hygiene management and reproductive tract infections: a comparison between rural and urban India. Waterlines, 38(2), 94–112. 10.3362/1756-3488.18-00032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anand, E. , Singh, J. & Unisa, S. (2015) Menstrual hygiene practices and its association with reproductive tract infections and abnormal vaginal discharge among women in India. Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. 6(4), 249‐254. 10.1016/j.srhc.2015.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babbar, K. (2021) Taboos and myths as a mediator of the relationship between menstrual practices and menstrual health. European Journal of Public Health, 31(Supplement_3), ckab165.552. 10.1093/EURPUB/CKAB165.552 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Babbar, K. , Martin, J. , Ruiz, J. , Parray, A.A. & Sommer, M. (2022) Menstrual health is a public health and human rights issue. The Lancet Public Health, 7(1), e10–e11. 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00212-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babbar, K. , Saluja, D. & Sivakami, M. (2021) How socio‐demographic and mass media factors affect sanitary item usage among women in rural and urban India. Waterlines, 40(3), 160–178. 10.3362/1756-3488.21-00003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- BBC . (2020) Coronavirus sparks a sanitary pad crisis in India. BBC News . https://www.bbc.com/news/world‐asia‐india‐52718434

- Biran, A. , Schmidt, W.‐P. , Sijbesma, C. , Sumpter, C. , Hernandez, O. , Hutton, G. , Lanata, C. , Luvendijk, R. , Ram, P. , Slater, M. , Sommer, M. , Toure, O. & Weinger, M. (2012) Background paper on measuring WASH and food hygiene practices‐definition of goals to be tackled post 2015 by the Joint Monitoring Programme. London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

- Budhathoki, S.S. , Bhattachan, M. , Castro‐Sánchez, E. , Sagtani, R.A. , Rayamajhi, R.B. , Rai, P. & Sharma, G. (2018) Menstrual hygiene management among women and adolescent girls in the aftermath of the earthquake in Nepal. BMC Women's Health, 18(1), 33. 10.1186/s12905-018-0527-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CARE International in Uganda CARE International in Uganda Annual Report. (2018)

- Chaudhary, P. , Vallese, G. , Thapa, M. , Alvarez, V. B. , Pradhan, L. M. , Bajracharya, K. , Sekine, K. , Adhikari, S. , Samuel, R. & Goyet, S. (2017) Humanitarian response to reproductive and sexual health needs in a disaster: the Nepal Earthquake 2015 case study. Reproductive Health Matters, 25(51), 25–39. 10.1080/09688080.2017.1405664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan, P. (2020) Gendering COVID‐19: impact of the pandemic on women's burden of unpaid work in India. Gender Issues, 38, 1–25. 10.1007/s12147-020-09269-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DASRA. (2015) On! Improving Menstrual Health and Hygiene in India. Retrieved from: https://www.dasra.org/resource/improving‐menstrual‐health‐and‐hygiene

- Dolan, C.S. , Ryus, C.R. , Dopson, S. , Montgomery, P. & Scott, L. (2014) A blind spot in girls’ education: menarche and its webs of exclusion in Ghana. Journal of International Development, 26(5), 643–657. 10.1002/jid.2917 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edwin, T. (2020) Covid‐19: Lockdown affects availability of affordable sanitary pads in rural areas ‐ The Hindu Business Line. The Hindu . https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/news/covid‐19‐impact‐lockdown‐affects‐availability‐of‐affordable‐sanitary‐pads‐in‐rural‐areas/article31450481.ece

- van Eijk, A. , Sivakami, M. , Thakkar, M. , Bauman, A. , Laserson, K. & Coates, S. (2016) Menstrual hygiene management among adolescent girls in India: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. BMJ Open, 6(3), e010290. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrman, S. , Kalyanpur, A. , Friedman, S. & Tran, N.T. (2020) Gendered implications of the COVID‐19 pandemic for policies and programmes in humanitarian settings. In: BMJ Global Health. BMJ Publishing Group, p. 2624. 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goli, S. , Sharif, N. , Paul, S. & Salve, P.S. (2020) Geographical disparity and socio‐demographic correlates of menstrual absorbent use in India: a cross‐sectional study of girls aged 15–24 years. Children and Youth Services Review, 117, 105283. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105283 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Govindaraj, R. (2016) How the Tamil Nadu Health System was transformed to a paperless health system in just 10 years . World Bank. Retrieved from: https://blogs.worldbank.org/health/how‐tamil‐nadu‐health‐system‐was‐transformed‐paperless‐health‐system‐just‐10‐years

- House, S. , Mahon, T. & Cavill, S. (2013) Bookshelf: Menstrual hygiene matters: a resource for improving menstrual hygiene around the world by Sarah House Thérèse Mahon, Sue Cavill Co‐published by WaterAid and 17 other organisations, 2012 www.wateraid.org/mhm. Reproductive Health Matters, 21(41), 257–259. 10.1016/S0968-8080(13)41712-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- IIPS and Macro International. (2017) National Family Health Survey (NFHS‐4), India, Mumbai: International Institute of Population Studies and Macro Internationals.

- IIPS and Macro International. (2020) Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Fact Sheets Key Indicators 22 States/UTs from Phase‐I. Improving Health Data Quality in India's Haryana and Punjab States | HFG. (n.d.). Retrieved January 5, 2021, from https://www.hfgproject.org/training‐officials‐monitor‐health‐information‐systems‐haryana‐punjab/

- Irudaya Rajan, S. , Sivakumar, P. & Srinivasan, A. (2020) The COVID‐19 pandemic and internal labour migration in India: a ‘Crisis of Mobility’. Indian Journal of Labour Economics, 63(4), 1021–1039. 10.1007/s41027-020-00293-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor, C. (2020) India faces “sanitary napkin shortage” amid COVID‐19 . Retrieved from: https://www.aa.com.tr/en/asia‐pacific/india‐faces‐sanitary‐napkin‐shortage‐amid‐covid‐19/1855047

- Kumar, R. (1993) Streamlined records benefit maternal and child health care. World Health Forum, 14(3), 305–307 https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/49125 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurian, O.C. (2016) Overcoming Data Challenges in Tracking India's Health and Nutrition Targets . Observer Research Foundation. Retrieved from: https://www.orfonline.org/research/overcoming‐data‐challenges‐tracking‐indias‐health‐nutrition‐targets/

- McMahon, S.A. , Winch, P.J. , Caruso, B.A. , Obure, A.F. , Ogutu, E.A. , Ochari, I.A. , & Rheingans, R.D. (2011). The girl with her period is the one to hang her head” Reflections on menstrual management among schoolgirls in rural Kenya. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 11(1), 7. 10.1186/1472-698X-11-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza, C. (2020) COVID‐19 lockdown: impact on menstrual hygiene management. CNBC Tv18. Retrieved from: https://www.cnbctv18.com/healthcare/covid‐19‐lockdown‐impact‐on‐menstrual‐hygiene‐management‐6018721.htm

- Menstrual Hygiene Scheme (MHS): National Health Mission. (n.d.). Retrieved from: https://nhm.gov.in/index1.php?lang=1&level=3&sublinkid=1021&lid=391

- Ministry of Home Affairs. (2020) Guidelines on lockdown measures to contain the spread of COVID‐19 in India .

- Mishra, I. & Jaiswal, A. (2020) For several women, it's back to cloth and ash as India faces sanitary pad crisis ‐ Times of India. Retrieved from: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/for‐several‐women‐its‐back‐to‐cloth‐and‐ash‐as‐india‐faces‐sanitary‐pad‐crisis/articleshow/75973494.cms

- Pandey, A. & Mishra, R.M. (2010) Health information system in india: issues of data availability and quality 1. Demography India, 39, 239–45. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips‐Howard, P. , Caruso, B. , Torondel, B. , Zulaika, G. , Sahin, M. & Sommer, M. (2016) Menstrual hygiene management among adolescent schoolgirls in low‐ and middle‐income countries: research priorities. Global Health Action, 9(1), 33032 10.3402/gha.v9.33032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PLAN International. (2020) Periods In a Pandemic Menstrual hygiene management in the time of COVID‐19 .

- Press Trust of India . (2020) Fourth phase of lockdown accounts for nearly half of total Covid cases in India. Hindustan Times. Retrieved from: https://www.hindustantimes.com/india‐news/fourth‐phase‐of‐lockdown‐accounts‐for‐nearly‐half‐of‐total‐covid‐cases‐in‐india/story‐BArq6GErIjSLtLp4qy2QGO.html

- Ravindran, S. & Shah, M. (2020) Unintended consequences of lockdowns: COVID‐19 and the shadow pandemic. National Bureau of Economic Research. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salve, P.S. , Vatavati, S. & Hallad, J. (2020) Clustering the envenoming of snakebite in India: the district level analysis using Health Management Information System data. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health, 8(3), 733–738. 10.1016/j.cegh.2020.01.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sebastian, A. , Hoffmann, V. & Adelman, S. (2013) Menstrual management in low‐income countries: needs and trends. Waterlines, 32(2), 135–153. 10.3362/1756-3488.2013.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A. , Rana, S.K. , Prinja, S. & Kumar, R. (2016) Quality of health management information system for maternal & child health care in Haryana state. India. PLOS ONE, 11(2), e0148449. 10.1371/journal.pone.0148449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, V. (2020) COVID‐19 | ASHA women workers deserve not just praise for frontline work but also better financial pay. The Quint. Retrieved from: https://www.thequint.com/voices/women/coronavirus‐asha‐women‐financial‐support‐recognition

- Sivakami, M. , van Eijk, A.M. , Thakur, H. , Kakade, N. , Patil, C. , Shinde, S. , Surani, N. , Bauman, A. , Zulaika, G. , Kabir, Y. , Dobhal, A. , Singh, P. , Tahiliani, B. , Mason, L. , Alexander, K.T. , Thakkar, M.B. , Laserson, K.F. & Phillips‐Howard, P.A. (2019) Effect of menstruation on girls and their schooling, and facilitators of menstrual hygiene management in schools: surveys in government schools in three states in India, 2015. Journal of Global Health, 9(1), 010408. 10.7189/jogh.09.010408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, M. (2009) Ideologies of sexuality, menstruation and risk: girls’ experiences of puberty and schooling in northern Tanzania. Culture, Health and Sexuality, 11(4), 383–398. 10.1080/13691050902722372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, M. & Sahin, M. (2013) Overcoming the taboo: advancing the global agenda for menstrual hygiene management for schoolgirls. American Journal Public Health, 103(9), 1556‐1559. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, M. , Schmitt, M.L. , Clatworthy, D. , Bramucci, G. , Wheeler, E. & Ratnayake, R. (2017) What is the scope for addressing menstrual hygiene management in complex humanitarian emergencies? A global review, 35, 1756–3488. 10.3362/1756-3488.2016.024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thacker, T. (2020) Covid zones in India: centre issues state‐wise division of covid‐19 red, orange & green zones. The Economic Times. Retrieved from: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics‐and‐nation/centre‐issues‐state‐wise‐division‐of‐covid‐19‐red‐orange‐green‐zones/articleshow/75486277.cms

- Traylor, A.M. , Ng, L.C. , Corrington, A. , Skorinko, J.L.M. & Hebl, M.R. (2020) Expanding research on working women more globally: identifying and remediating current blindspots. Journal of Social Issues, 76(3), 744–772. 10.1111/JOSI.12395 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- UN Women. (2020a) The impact of COVID‐19 on women. United Nations, April, 21. Retrieved from: https://asiapacific.unwomen.org/en/digital‐library/publications/2020/04/policy‐brief‐the‐impact‐of‐covid‐19‐on‐women

- UN Women. (2020b) Unlocking the lockdown: The gendered effects of COVID‐19 on achieving the SDGS in Asia and the Pacific | UN Women Data Hub . https://data.unwomen.org/publications/unlocking‐lockdown‐gendered‐effects‐covid‐19‐achieving‐sdgs‐asia‐and‐pacific

- VanLeeuwen, C. & Torondel, B. (2018) Improving menstrual hygiene management in emergency contexts: literature review of current perspectives. International Journal of Women's Health, 10, 169–186. 10.2147/IJWH.S135587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, B. & Darmadi, G. (2020) Coronavirus is exacerbating menstruation health risks for those living in “period poverty”. ABC News. Retrieved from: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020‐10‐03/coronavirus‐poses‐period‐poverty‐worse‐around‐the‐world/12700290