Abstract

Using an online survey experiment and a sample of 1650 participants from the Mid‐Atlantic region in the United States, we investigate the effects of COVID‐19 and two reinforcing primes on preferences for local food and donations to support farmers, farmers markets, and a food‐relief program. At the beginning of the survey, we induce a subset of participants to think about the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on either their personal life, finances, and health or on their local community and its members. Both primes increase participants’ levels of anxiety and slightly reduce their sense of community. Additionally, both primes significantly decrease the hypothetical price premium participants are willing to pay for local food, that is, both for fruits and vegetables and for meat products. The primes do not significantly affect the amount donated to charitable organizations, except when controlling for participants’ own experiences with COVID‐19. While priming increases donations for some participants, it decreases donations for those with a “strong” COVID‐19 experience, especially for the food relief program. [EconLit Citations: C90, Q19].

Keywords: COVID‐19, farmers, local food, online experiment, priming

Abbreaviation

- OLS

ordinary least squares

1. INTRODUCTION

Some of the most tangible shifts brought on by the COVID‐19 pandemic are taking place in the food system. As the pandemic has uncovered vulnerabilities in food supply chains, many consumers changed their food buying behavior because of availability and tighter budgets, and interest in local food increased (Cappelli & Cini, 2020; CPG FMCG & Retail, 2020; Hobbs, 2020; Schmidt et al., 2020; Thilmany et al., 2021; Weersink et al., 2021). In addition, food at home preparation increased significantly during the pandemic (Chenarides et al., 2021; Bender et al., 2021; Edmondson et al., 2021; Ellison et al., 2021; Jensen et al. 2021). Consumers’ food‐sourcing preferences also changed during the pandemic. With an increase in COVID cases, consumers were less willing to shop in person in grocery stores (Chenarides et al. 2021; Grashuis et al., 2020). Edmondson et al. (2021) conducted a nationwide consumer survey about local food purchasing and find that higher‐income consumers and consumers with children were more likely to shop at a local farm or food business. Concerns about food item availability increased the frequency of online shopping and consumers that are more concerned about COVID‐19 are more likely to shop online (Jensen et al. 2021). Melo (2020) suggests that while online grocery shopping will supply the basics, local shopping will provide fresh local goods to those consumers who value convenience, want to support the local economy, and prefer to avoid hot spot areas for the virus.

However, even though consumers’ interest in sourcing locally might have increased, their access to local foods may have suffered. For example, O'Hara and Low (2020) find that neighborhood farmers markets’ sales decreased in the Washington, D.C. area through the pandemic because of regulations. Ali et al. (2021) find that a number of fruit and vegetable vendors closed or had limited setup in New York City early in the pandemic. US households had to make tradeoffs based on budgets and availability. After surveying a panel of consumers four times at the beginning of the pandemic, Ellison et al. (2021) find that, in terms of food values, taste remained an important factor for food purchases, but nutrition and price decreased in importance for the surveyed households. Leggett (2020) suggests that future shoppers will be more interested in understanding the supply chain—from farm to distribution—and willing to pay more for products with high‐quality assurances and verifiable safety standards. However, despite this wide‐ranging pandemic‐related research, we do not yet know the full extent of the current pandemic's impact on people's attitudes towards local farmers and local foods.

On one hand, the pandemic has spotlighted the concerns for others’ wellbeing and community engagement and the importance of sustaining farmers and ranchers committed to growing the food consumers depend on. On the other, it has also shifted consumers’ focus to personal safety and household financial and economic concerns (Cranfield, 2020). The limited access to basic necessities early in the pandemic also increased consumers’ stress and anxiety (Kassas & Nayga, 2021). Thus, personal concerns may be at odds with community‐minded aspirations. Our study aims to investigate these potentially countervailing influences of the pandemic on attitudes towards local food and farmers.

Previous research has investigated consumer demand and attitudes towards local food (see Feldmann & Hamm, 2015 for a review) and mapped consumers’ preference and willingness to pay a premium for it (Printezis & Grebitus, 2018; Willis et al., 2013). Local food preferences are driven by multiple reasons. Some consumers have altruistic motives such as supporting the local economy, the local community, or the environmental friendliness of local food products (Bean & Sharp 2011; Brown et al., 2009; Dunne et al., 2011; Megicks et al., 2012; Yue & Tong, 2009). Others prefer local food for hedonistic motives, such as its freshness, taste, and healthfulness (Adams & Adams, 2011; Birch et al., 2018; Campbell et al., 2013; Conner et al., 2010; Cranfield et al., 2012; Dunne et al., 2011; Grebitus et al., 2013; Onozaka & McFadden 2011; Yue & Tong, 2009). Some consumers also perceive local food as safer, given its easier traceability (Darby et al., 2008; Nganje et al., 2011; Yue & Tong, 2009).

In this study, we investigate the influence of the current pandemic on respondents’ reported price premium for local food and on their charitable support for farmers, farmers markets, and a food relief program. The pandemic could strengthen the safety and environmental motives for purchasing local food, increasing the price premium accorded to local food. Alternatively, the anxiety caused by the pandemic might reduce altruistic motives for selecting local food, thereby decreasing the price premium. To study the causal effect of the COVID‐19 pandemic, at the beginning of the study we randomly assign a group of respondents to two priming treatments and a control group. Priming consists in the activation of mental concepts through situational cues (Bargh & Chartrand, 2014). Common priming techniques include prompting subjects to think about specific concepts or experiences (Callen et al., 2014; Cohn et al., 2015), and are used to study the impact of primed concepts on subsequent behavior and attitudes. This method stems from experimental psychology and has become an increasingly popular tool in economics (Cohn et al., 2016).

We conduct an online survey experiment with 1650 participants from the Mid‐Atlantic region and Washington State in the United States to investigate the impact of the current coronavirus pandemic on preferences for local food and on the support for farmers via a charitable donation decision. We also aim to distinguish the impact of concerns related to individual safety and finances from related concerns focused on the communities where these individuals live. In the survey experiment, respondents are randomly divided into three groups, two treatment groups, and one control group. At the start of the survey, we ask respondents in the two treatment groups a series of questions about either the personal impact (Individual prime) or the impact on their community (Community prime) of the pandemic. We assume that this reminder of the pandemic's impact increases the salience of the primed concepts when answering subsequent questions. Moreover, we expect the two reminders (primes) will shift respondents’ focus on specific features of the pandemic and their preferences accordingly (Cappelen et al., 2020; Cohn & Maréchal 2016).

After the prime, we measure local food preferences by collecting respondents’ hypothetical price premium for local produce and meat products using the “unfolding brackets method” (Cornsweet, 1962; Falk et al., 2018). Participants are asked to indicate whether they would buy local or nonlocal produce (and meat) at varying price premiums for local food that adapt upwards or downwards to narrow in on the indifference point (accurate to a 5% interval). We then measure respondents’ support for farmers, farmers markets, or food relief programs by offering them the opportunity to donate part of a randomly assigned $25 bonus to three charities. We select one charity supporting farmers (Farm Aid), one supporting farmers markets (Farmers Market Coalition), and one committed to bringing food to people in need (World Central Kitchen). The incentivized donation should gauge revealed preferences for supporting farmers, farmers markets, or the local community. The use of donation choices to capture participants’ support for different causes has been previously used to study revealed preferences for several causes, such as compensating organ donors (Elias et al., 2019), anti‐immigration attitudes (Bursztyn et al., 2020), environmental causes (Fanghella et al., 2019; Goff et al., 2017).

We hypothesize that thinking about the pandemic would increase participants’ anxiety, which we measure with the six‐item short‐form state anxiety inventory developed by Marteau & Bekker (1992), especially in the Individual prime treatment. Stress and anxiety have been linked to a reduction in ethical and prosocial behavior (Kouchaki & Desai, 2015; Vinkers et al., 2013). Therefore, we hypothesize that the Individual prime will reduce the price premium for local food and the donation to the three charities. We also hypothesize that the Community prime will increase respondents’ sense of community belonging, which we measure using a question by Carpiano and Hystad (2011). The fear of an external threat has been linked to increased group identification and willingness to act in support to the group (Huddy, 2015; Kuehnhanss et al., 2020; LeVine & Campbell, 1972). In this study, the COVID‐19 pandemic could increase the self‐reported price premium for local food and donations to the three charitable organizations by increasing the sense of community belonging and the willingness to support family farmers, farmers markets, and food relief programs.

Our survey results suggest that thinking about the pandemic increases anxiety, especially when thinking about the individual impact, and reduces the sense of community belonging in both treatment groups. We do not find any significant difference between the two primes. Consistent with these effects, we find that thinking about the impact of COVID‐19 (i.e., primed by both treatments) reduces the stated price premiums that respondents are willing to pay for local fruits and vegetables and local meat products. Thinking about the pandemic does not significantly impact the average donation, however, possibly because it does not affect support for the charitable organizations and generosity. An ex‐post power calculation shows that the null result might be driven by the low statistical power of our estimates.

Our respondents also completed a questionnaire where we collected information on shopping habits, attitudes towards local food, whether they or anyone in their family had been infected with COVID 19 or lost their job because of the pandemic, and several demographic variables. We find that the primes induce a larger reduction in price premium for local food when controlling for participants’ COVID‐19 experience. The impact of the two primes on donations instead differs depending on participants’ experience. More specifically, the primes increase donations when controlling for COVID‐19 experience; however, they decrease donations for participants with a “strong” COVID‐19 experience, especially donations in favor of the food aid program. This decrease in donations seems to be driven by a larger increase in anxiety in participants with a more substantial experience with COVID‐19.

The contribution of this paper is to provide an insight into the impact of the pandemic on preferences for local food and willingness to support farmers, farmers markets, and a food relief program. It also investigates the mechanism for the pandemic's impact by attempting to disentangle pandemic‐induced personal concerns from community‐minded aspirations. However, in the case of the COVID‐19 pandemic, we find that both our Individual and Community primes increased respondents’ anxiety levels and, thus, had similar impacts on attitudes towards local food and charitable giving.

In the next section, we discuss the experimental design and the data collected during the experiment. Section 3 outlines the hypotheses tested. In Section 4, we present and report our empirical analysis and results. Section 5 concludes.

2. EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN

2.1. Sample and recruitment

We conducted an online survey experiment with 1650 participants 18 or older from the Mid‐Atlantic region and Washington state1 in the United States. The Mid‐Atlantic region is characterized by proximity to high‐density population centers, access to both urban and suburban areas, and large population size and diversity. We focused on this region to recruit participants with a potentially more homogeneous definition of local food. The study was conducted from November 19 to 29, 2020, with the help of the survey provider Dynata.2 Participants spent, on average, approximately ten min completing the survey and received a participation fee of $4.3

2.2. Treatments

We randomly assign participants to two treatment and control conditions. In the first treatment condition, that is, the Individual prime, we ask respondents to quantify on a scale from 0 to 10 the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on their personal life and their personal financial and health concerns, and then ask them to describe the most important ways in which the pandemic has impacted their life. In the second treatment condition, that is, the Community prime, we ask respondents to quantify on a scale from 0 to 10 the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on their local community, and their financial and health concerns about their local community and its local economy, including local farmers and food retailers. Then, we ask them whether they know of any businesses in their local community that had been forced to close because of the pandemic and to describe the most important ways in which the pandemic has impacted their community. Asking participants to think about the impact of COVID‐19 places the crisis at the top of the respondents’ minds, creating the context in which they would then consider the following questions and decisions. Participants in the “control” condition were not reminded about the pandemic or asked about its impacts.

2.3. Preference for local food

After the treatment, we ask participants about their local food preferences through a series of choice‐based questions meant to elicit a hypothetical price premium. For this task, we define local food as food grown, produced, or processed within 50 miles from the respondents. This definition has been used by, among others, Chambers et al. (2007), Groves (2005), and Trobe (2001). Moreover, Darby et al. (2008) find that consumers assign the same value to different definitions of “local” and that willingness to pay for a local attribute is independent of other features. Perhaps more importantly, in the study we are mainly interested in the difference between treatments and control conditions, and we do not expect that effect to be affected by the specific definition employed. We measure the price premium for local fruit or vegetables and the price premium for local meat or poultry products with two sets of questions adapted from Carpio and Isengildina‐Massa (2009). We select food categories instead of specific food items to avoid food‐specific aspects other than preference over the local attribute (as disliking the food selected, food allergies, religious prohibitions, and others) would drive respondents’ answers (Cranfield et al., 2012).

We collect the self‐reported price premium for local food using the “unfolding brackets method” where participants are asked to choose between local and nonlocal food at varying price premiums for local food. The unfolding brackets mechanism requires an adaptive questionnaire, with binary choices presented to participants depending on their prior choices. The first choice is between nonlocal and local food products at equal prices. If a participant chooses the local food, then the next choice will be between nonlocal food and 50% more expensive local food. The alternatives adjust upwards or downwards to narrow in on the indifference point and is accurate to a 5% interval. This method is used in Falk et al. (2016) to elicit risk taking and time discounting in surveys since these measures are very comparable to the incentivized experimental measures collected based on the multiple price lists. To reduce the hypothetical bias, at the beginning of the survey we ask respondents to commit to providing accurate and honest answers by signing an oath, and we increase the consequentiality of the survey by stating that it would help inform policy decisions. Prior research has shown that soft commitment and increased consequentiality improve data quality and reduce hypothetical bias (Cibelli, 2017; Jacquemet et al., 2011; Vossler & Watson 2013). Moreover, since we are primarily interested in the priming effect, the hypothetical bias should not affect the comparative static in the three groups.

2.4. Donation

To study whether the impact of COVID‐19 increases participants’ willingness to support farmers, farmers market, or the local communities through a food relief program, or increases participants’ self‐interest by increasing participants’ worries, we elicit an incentivized donation decision. We ask participants whether they want to donate part of a $25 bonus to any of three charitable organizations or keep it all for themselves. To capture individual preferences for certain charitable organizations, we ask participants to make the allocation decisions between themselves and three charities. We have selected one charity supporting farmers (Farm Aid, whose mission is to build a system of agriculture that values family farmers), one supporting farmers markets (Farmers Market Coalition, whose mission is strengthening farmers markets across the United States so that they can serve as community assets), and one committed to bringing food to people in need (World Central Kitchen, which is working across America to safely distribute individually packaged, fresh meals in communities that need support). The possibility of keeping the monetary bonus reflects the self‐interested choice. Participants can allocate any share of the $25 to themselves, Farm Aid, Farmers Market Coalition, and World Central Kitchen. While all participants make the choice, we inform participants that a randomly selected group of participants will receive a $25 bonus, that would be accredited within three weeks by the survey company on their account.4

2.5. Manipulations and personal characteristics questionnaire

To assess whether our treatments modified participants’ sense of community, we ask them to rate their sense of belonging to their local community using a question by Carpiano and Hystad (2011). We ask participants to describe their sense of belonging to their local community on a 5‐point scale from “very weak” to “very strong.” We then assess whether our treatment affected respondents’ state anxiety using the six‐item short‐form state anxiety inventory developed by Marteau and Bekker (1992). We ask participants to rate their current feelings (calm, tense, upset, relaxed, content, worried) on a 4‐point scale from “not at all” to “very much,” and we then combine these individual ratings in a state anxiety score, from 20 to 80.

After answering questions related to our main outcome variables, survey participants are then asked a variety of questions about their shopping habits, preferences, and demographic variables. The full set of questions can be found in Supporting Information: Appendix B.

3. HYPOTHESES

In our study, we remind participants about their concerns related to the COVID‐19 pandemic. If being primed to think about COVID‐19 increases state anxiety, we expect this to reduce altruistic motives for purchasing local food, decreasing reported price premiums. Moreover, we expect a reduction in generosity and willingness to support farmers, farmers' markets, and a food relief program. Anxiety can indeed lead to self‐interested behavior, by increasing the perception of being threatened and stimulating intuitive automatic processing (Grecucci et al., 2013; Kouchaki & Desai, 2015; Zhang et al., 2020).

H1: Being reminded about COVID‐19 and personal health and safety concerns related to COVID‐19 decreases the premium for local food.

H2: Being reminded about COVID‐19, and personal health and safety concerns related to COVID‐19 decreases the amount donated to the three charitable organizations supporting farmers, farmers markets, and a food relief program.

Thinking about COVID‐19 and in particular, its impact on the community might increase the sense of community. External threats can be crucial to foster a stronger group identity (Giles & Evans, 1985), increasing willingness to act in support of the group (Huddy, 2015; Kuehnhanss et al., 2020; LeVine & Campbell, 1972). If the “preference” for local food is perceived as a way to support local communities, price premium for local food might increase as a consequence of the prime. Also, the threat of COVID‐19 might increase the sense of community and willingness to support the community with donations, in particular to a charity supporting local communities (World Central Kitchen).

H3: Being reminded about the impact and concerns, especially on the local community, related to COVID‐19 increases the price premium for local food.

H4: Being reminded about the impact and concerns on the local community related to COVID‐19 increases the amount donated to the three charitable organizations supporting farmers, farmers markets, and a food relief program.

4. EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS

4.1. Empirical strategy

First, we investigate the effects of the primes on sense of community belonging and on state anxiety. We then study treatment effects on the preference for local food and donations. We use four different measures of preference for local food: (i) the average percentage price premium for local food (on a scale from −100 to +100); (ii) the percentage price premium for local fruit or vegetables; (iii) the percentage price premium for meat or poultry; and (iv) a binary variable equal to 1 if the respondent has a positive price premium for local food. Similarly, we consider five different specifications for the donation decision: (i) the total amount of the $25 bonus donated to the three charitable organizations (on a scale from 0 to $25); (ii) the amount donated to “Farm Aid”; (iii) the amount donated to “Farmers Market Coalition”; (iv) the amount donated to “World Central Kitchen”; (v) a binary variable equal to 1 if the respondent donates a positive amount.

We will first conduct descriptive data analysis and assess balance of observable characteristics across treatments. We will then perform a parametric analysis, comparing the price premium and donation outcomes across treatment groups. To analyze whether the preference for different charities depends on the prime, we compare the difference in donation between two of the three charities across treatments.5 We then estimate linear models using the outcome measures described in the previous section.

More specifically, we estimate the following model:

| (1) |

where denotes the outcome variable for participant i, and and are the coefficients of interest. indicates whether participant i was asked about individual impact and concerns related to the pandemic. indicates whether participant i was asked about the impact and concerns for the local community related to the pandemic. is a vector of control variables and is an idiosyncratic error term. We control for variables that differ significantly between the two treatment and the control group.6 We estimate Equation (1) for several closely related specifications and models: double bounded at −100 and +100 Tobit regressions when the dependent variable is the price premium, double bounded at 0 and 25 Tobit regressions when the outcome is the donation amounts, Logit regressions when the outcome is a binary variable, and Truncated regressions when excluding participants not donating.7

As a robustness check, we will perform the analysis excluding participants who stated they are not willing to provide truthful and accurate answers (91 participants) and report these results in Supporting Information: Appendix A.1.

Finally, we examine two sources of heterogeneity in treatment effects. Prior experience with COVID‐19 is likely that the impact of the prime depends on whether respondents’ have been infected or lost their job because of the pandemic, or whether someone in their family or close circle of friends have been infected or has lost the job. Since the rationale behind the prime relies on being able to increase the salience of the pandemic, it is plausible that the prime will affect differently those with a “stronger” COVID‐19 experience, who might already have the pandemic salient in their mind. Participants’ state anxiety and sense of community belonging are also likely to differentially impact participants’ responses to our primes. We expect participants with higher state anxiety to decrease their price premium for local food and their donations after our prime. Participants with a higher sense of community might instead react to the COVID‐19 prime by increasing their donations and price premium for local food.

4.2. Descriptive statistics

Demographic characteristics of the sample in our study can be found in Table 1. The table reports the average level across all the priming conditions and the results of the F‐test comparing the three treatment conditions. The average age of participants is 50 years; 55% identify as female and 44% as male; 19% of participants have high school diploma or less; 58% of them work either part‐ or full‐time or are self‐employed; 22% are retired; and only 2% are students. In addition, 50% of participants live in a suburban area, 32% live in an urban area, and 18% in a rural area. 54% of participants are married, and the average household size is 2.64 persons. A comparison of demographics between participants assigned to the different treatments shows no significant differences except for gender, education, and annual income. We will therefore control for these variables in our regression analysis. The duration of the study is not significantly different across treatments.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | F‐test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Control | Individual | Community | p Value | |

| Age | 49.77 | 49.73 | 49.60 | 49.98 | 0.92 |

| (15.30) | (15.47) | (14.72) | (15.72) | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 0.44 | 0.40 | 0.49 | 0.44 | 0.01*** |

| Female | 0.55 | 0.59 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.01*** |

| Other or not say | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.65 |

| Education | |||||

| High school or less | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.80 |

| Some college | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.60 |

| Technical degree | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.06* |

| 4‐year college | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.91 |

| Postgraduate | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.58 |

| Employment status | |||||

| Unemployed | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.19 |

| Full‐time | 0.44 | 0.43 | 0.45 | 0.44 | 0.77 |

| Part‐time | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.26 |

| Self‐employed | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.48 |

| Homemaker | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.97 |

| Retired | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.59 |

| Not working | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.86 |

| Student | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.60 |

| Annual income | |||||

| Under $24,999 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.88 |

| $25,000 to $49,999 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.77 |

| $50,000 to $74,999 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.85 |

| $75,000 to $99,999 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.55 |

| $100,000 to $104,999 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.83 |

| $125,000 to $149,999 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.17 |

| $150,000 to $174,999 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.08* |

| $175,000 and over | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.72 |

| State | |||||

| Delaware | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.24 |

| Maryland | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.01*** |

| New Jersey | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.43 |

| New York | 0.34 | 0.37 | 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.22 |

| Pennsylvania | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.23 |

| Virginia | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.25 |

| Area | |||||

| Urban | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.92 |

| Suburban | 0.50 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.52 | 0.58 |

| Rural | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.58 |

| Marital status | |||||

| Single | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.25 | 0.28 |

| Living with partner | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.15 |

| Married | 0.54 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.56 | 0.39 |

| Widowed | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.40 |

| Separated or divorced | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.92 |

| People in the household | 2.64 | 2.86 | 2.51 | 2.55 | 0.15 |

| (3.31) | (5.11) | (1.90) | (1.46) | ||

| Children in the household | 0.56 | 0.58 | 0.58 | 0.53 | 0.67 |

| (1.10) | (1.03) | (1.29) | (0.95) | ||

| Hispanic | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.45 |

| Race | |||||

| White | 0.72 | 0.74 | 0.73 | 0.69 | 0.10 |

| Black or African American | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.21 |

| Asian | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.68 |

| Voting preferences | |||||

| Republican | 0.31 | 0.33 | 0.31 | 0.30 | 0.47 |

| Democrat | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.41 | 0.26 |

| Independent | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.66 |

| N | 1650 | 571 | 546 | 533 | 1650 |

Note: p Values based on the F‐test of equality across the three priming conditions. We report only States with a share or respondents larger than 0.01. Significance levels are indicated as follows: *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Supporting Information: Table A.2.1 of Appendix A.2 reports information about shopping behavior, altruism, and experience with COVID‐19 and the F‐test results comparing the three treatment conditions. Respondents report that around 42‐43% of the food they purchased over the previous month was local. This relatively high level appears to reflect a wide variety of personal definitions of local food. When asked about their willingness to share with others without expecting anything in return when it comes to charity, participants report a high level of altruism (8 out of 10). Also, on average, 3.69% of respondents report giving to charities sometimes/on a regular basis.8 When asked about their experience with COVID‐19, around 10% report having been infected, 25% report having lost their job or having reduced work hours, around 30% report having a friend or a family member who got infected, and again 30% report someone losing their job because of the pandemic. All variables are balanced across treatment groups, except for the number of people who report having had someone in their family losing their job and for the shopping role, where the share of people that never shop is higher in the Individual prime group. We will therefore include these variables as covariates in our regression analysis.

Descriptive statistics of the outcome variables in our study are also presented in Supporting Information: Appendix A.2, Table A.2.2. The mean price premium that respondents accord to local fruits and vegetables is around 35%, and the mean price premium for local meat or poultry is around 31%. In addition, 20% of respondents report a negative or null price premium for local, and 13% report being willing to pay 100% more for a product that is local. The price premium for local animal products is significantly different from the price premium for local produce; however, as can be seen in what follows, this difference is not influenced by our treatment (i.e., the difference in price premium is not significantly different across treatments). Respondents donate an average of $14.74 (59% of the $25 bonus), 80% donate a positive amount, and 28% donate the entire $25. The charitable organization receiving significantly more funds between the three is World Central Kitchen ($5.59 out of $25); however, the difference in donations between charities is not significantly different across treatments.

We compare the demographic characteristics of our sample to those of individuals matching the same demographic eligibility criteria in the nationally representative IPSUM USA sample from 2019 (Ruggles et al., 2019). We find very few differences in gender, employment status, race, and share of Hispanics. We observe differences in education status, where the share of people with high school or less is higher in the US representative sample (the IPSUM USA data are more detailed with respect to the education status, which might create some discrepancies between the two measurements). Results of the comparison are shown in Supporting Information: Table A.2.3 of Appendix A.2.

4.3. Effect of the COVID‐19 primes

4.3.1. Impact of the COVID‐19 primes on sense of community belonging and state anxiety

We document the change in sense of community belonging and state anxiety following the Individual and Community primes. Table 2 shows ordinary least squares (OLS) results for the impact of the priming on sense of community and state anxiety using the model in Equation (1). Being primed to think about COVID‐19 (with either the Individual or Community prime) decreases the sense of community, and the two coefficients are not significantly different from each other as evidenced by the results of the Wald test of equality. Both primes increase state anxiety among respondents, but only the Individual prime has a significant impact. Controlling for the demographic variables that differ across treatment conditions, as shown in columns 2 and 4, does not change these results. Excluding participants who stated they are not willing to provide truthful and accurate answers also gives similar results, with only the impact of the Individual prime for the model without covariates becoming nonsignificant (see Supporting Information: Table A.1.1 in Appendix A.1).

Table 2.

OLS models of the impact of the primes on sense of community and state anxiety

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sense of community | Sense of community | State anxiety | State anxiety | |

| Individual | −0.112* | −0.123** | 2.356*** | 3.014*** |

| (0.062) | (0.061) | (0.842) | (0.826) | |

| Community | −0.104* | −0.121** | 1.220 | 1.321 |

| (0.062) | (0.061) | (0.844) | (0.824) | |

| Annual Income | 0.060*** | −0.440*** | ||

| (0.011) | (0.143) | |||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | −0.094* | 2.659*** | ||

| (0.052) | (0.716) | |||

| Other or not say | −0.186 | 2.536 | ||

| (0.440) | (2.810) | |||

| Education | 0.010 | −0.036 | ||

| (0.019) | (0.267) | |||

| Family job loss | 0.052 | 5.675*** | ||

| (0.058) | (0.749) | |||

| Shopping role | 0.085*** | −0.672** | ||

| (0.029) | (0.340) | |||

| Constant | 3.203*** | 2.531*** | 39.311*** | 41.344*** |

| (0.044) | (0.148) | (0.574) | (1.826) | |

| Observation | 1650 | 1645 | 1650 | 1645 |

| Wald's test | 0.016 | 0.001 | 1.691 | 3.937 |

| Significance | (p = 0.898) | (p = 0.971) | (p = 0.194) | (p = 0.047) |

Note: Sense of community measured on a 5‐point scale from “very weak” to “very strong.” State anxiety measured on a scale from 20 to 80 by combining rates for current feelings (calm, tense, upset relaxed, content, worried). Individual is a dummy variable taking value 1 for participants primed to think about the individual impact of COVID‐19. Community is a dummy variable taking value 1 for participants primed to think about the impact on their local community of COVID‐19. Annual income is measured as the income bracket participants select on an 8‐point scale from “Under $ 24,999” to “$175,000 and over.” Education is measured as the highest degree of school completed on a 5‐point scale from “High school graduate or less” to “Postgraduate studies.” Family job loss is a dummy variable taking value 1 for participants reporting having anyone in the family or close circle of friends lose their job because of the pandemic. Shopping role is measured on a 5‐point scale from “I am never the shopper” to “I am the only shopper.” Wald's test of equality of the Individual and Community coefficients. Robust standard errors are shown in parentheses. Significance levels are indicated as follows: *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Abbreviation: OLS, ordinary least squares.

4.3.2. Impact of the COVID‐19 primes on preference for local food

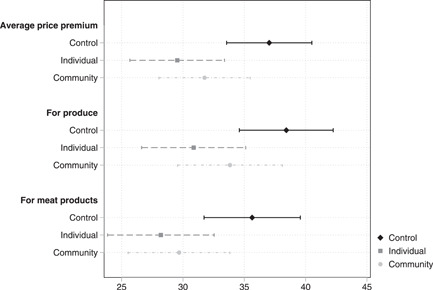

We now turn to examine the impact of COVID‐19 primes on the price premium for local food. Figure 1 shows that the stated average price premiums respondents are willing to pay for local food (average price premium and price premium for fruits and vegetables, and for meat products are significantly lower when primed to think about COVID‐19. Table 3 shows double bounded Tobit results for the impact of the two COVID‐19 primes following Equation (1) on price premium for local food. Columns 2, 4, and 6 correspond to the augmented model, which controls for potentially confounding factors that differ significantly between the three treatment groups. We find that being primed to think about COVID‐19 significantly decreases the local‐food price premium by more than 8 percentage points for the Individual prime and 6 for the Community prime. The coefficients for the Individual and Community prime are not significantly different from each other, as evidenced by the lack of significance of the Wald test of equality between the two coefficients. In Supporting Information: Appendix A.1, Table A.1.2 reports the results for a subsample comprised only of respondents willing to commit to providing truthful answers. For this subsample of participants, the magnitude of the effect is smaller across all specifications and the coefficient for the Individual prime is not significant for meat products and when considering the average, while it is significant for the Community prime across all specifications. The coefficients on Individual and Community prime are not significantly different from each other.9 The results of this analysis indicate that COVID‐19 decreases the price premium for local food, possibly because it increases the sense of anxiety and subsequent selfish choices.

Figure 1.

Mean price premium for local food. Bands indicate ±1 standard error.

Table 3.

Tobit model for the impact of COVID‐19 primes on price premium for local food

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average premium | Average premium | Premium for local produce | Premium for local produce | Premium for local meat | Premium for local meat | |

| Individual | −8.392*** | −7.634** | −9.096** | −8.348** | −8.815** | −8.038** |

| (3.095) | (3.029) | (3.690) | (3.614) | (3.659) | (3.612) | |

| Community | −6.160** | −6.138** | −6.112 | −6.340* | −7.547** | −7.336** |

| (3.113) | (3.037) | (3.714) | (3.625) | (3.679) | (3.620) | |

| Annual Income | 1.458*** | 1.964*** | 1.256** | |||

| (0.530) | (0.632) | (0.631) | ||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | −1.592 | −2.417 | −1.110 | |||

| (2.629) | (3.136) | (3.132) | ||||

| Other/not say | −25.695* | 3.128 | −61.947*** | |||

| (15.250) | (18.276) | (18.570) | ||||

| Education | −0.177 | −0.904 | 0.332 | |||

| (0.984) | (1.173) | (1.173) | ||||

| Family job loss | 10.234*** | 12.067*** | 9.817*** | |||

| (2.762) | (3.295) | (3.295) | ||||

| Shopping role | 10.870*** | 13.200*** | 9.795*** | |||

| (1.304) | (1.560) | (1.558) | ||||

| Observation | 1650 | 1645 | 1650 | 1645 | 1650 | 1645 |

| Wald's test | 0.504 | 0.238 | 0.634 | 0.301 | 0.117 | 0.037 |

| Significance | (p = 0.478) | (p = 0.626) | (p = 0.426) | (p = 0.583) | (p = 0.733) | (p = 0.848) |

Note: Average premium measured as average of the price premiums participants state to be willing to pay for local produce and local meat, on a scale from −100 to 100. Premium for local produce and premium for local meat are the average price premium that participants state to be willing to pay for local fruits and vegetables and local meat products respectively, on a scale from −100 to 100. Individual is a dummy variable taking value 1 for participants primed to think about the individual impact of COVID‐19. Community is a dummy variable taking value 1 for participants primed to think about the impact on their local community of COVID‐19. Annual income is measured as the income bracket participants select on an 8‐point scale from “Under $ 24,999” to “$175,000 and over.” Education is measured as the highest degree of school completed on a 5‐point scale from “High school graduate or less” to “Postgraduate studies.” Family job loss is a dummy variable taking value 1 for participants reporting having anyone in the family or close circle of friends lose their job because of the pandemic. Shopping role is measured on a 5‐point scale from “I am never the shopper” to “I am the only shopper.” Wald's test of the equality of the Individual and Community coefficients. Significance levels are indicated as follows: *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

4.3.3. Impact of the COVID‐19 primes on donations

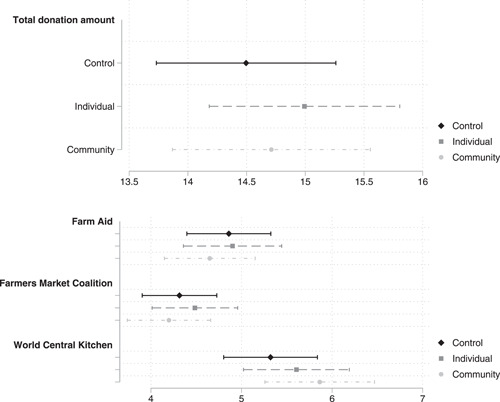

Examining the impact of the COVID‐19 prime on the charity donation decision, Figure 2 shows the mean donation of participants in the three treatments, and the breakdown of donations to specific charities. The amount donated to World Central Kitchen is significantly higher than the amount donated to any other charity, but there is no statistically significant difference in behavior across the three respondent groups.10 Table 4 shows Tobit models for the impact of the COVID‐19 primes on the amount donated and donation to the three charities. Comparing the coefficients on the two primes with a Wald test of equality shows no significant differences across the three charities. The primes do not significantly impact the amount participants donate to the three charities. In other words, while COVID‐19 primes change respondents’ local food price premiums, they do not modify their decisions related to charitable donations to support farmers, farmers' markets, or food aid.11

Figure 2.

Mean donation. Bands indicate ±1 standard error.

Table 4.

Tobit model for the impact of COVID‐19 primes on donation

| Total donation | Farm aid | Farmers market coalition | World central kitchen | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Individual | 1.210 | 1.185 | −0.469 | −0.118 | 0.491 |

| (1.083) | (1.081) | (0.614) | (0.548) | (0.686) | |

| Community | 0.800 | 0.679 | −0.766 | −0.646 | 0.551 |

| (1.093) | (1.088) | (0.616) | (0.552) | (0.688) | |

| Annual income | 0.523*** | 0.189* | 0.041 | 0.132 | |

| (0.191) | (0.108) | (0.097) | (0.120) | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 1.588* | −0.815 | −0.932* | 1.896*** | |

| (0.943) | (0.534) | (0.478) | (0.597) | ||

| Other or not say | 12.426** | 3.848 | 2.885 | 3.481 | |

| (5.906) | (3.006) | (2.685) | (3.308) | ||

| Education | 0.377 | ‐0.209 | 0.223 | 0.466** | |

| (0.352) | (0.200) | (0.179) | (0.223) | ||

| Family job loss | 0.044 | 0.007 | 0.136 | 0.747 | |

| (0.983) | (0.559) | (0.500) | (0.622) | ||

| Shopping role | −0.415 | 0.189 | −0.084 | −0.077 | |

| (0.465) | (0.263) | (0.236) | (0.293) | ||

| 1650 | 1645 | 1645 | 1645 | 1645 | |

| Wald's test | 0.136 | 0.210 | 0.224 | 0.889 | 0.007 |

| Significance | (p = 0.712) | (p = 0.647) | (p = 0.636) | (p = 0.346) | (p = 0.931) |

Note: Total donation is the total amount of the $25 bonus participants donate to the three charities. Average donation to each charity is reported in columns 3‐5. Individual is a dummy variable taking value 1 for participants primed to think about the individual impact of COVID‐19. Community is a dummy variable taking value 1 for participants primed to think about the impact on their local community of COVID‐19. Annual income is measured as the income bracket participants select on an 8‐point scale from “Under $ 24,999” to “$175,000 and over.” Education is measured as the highest degree of school completed on a 5‐point scale from “High school graduate or less” to “Postgraduate studies.” Family job loss is a dummy variable taking value 1 for participants reporting having anyone in the family or close circle of friends lose their job because of the pandemic. Shopping role is measured on a 5‐point scale from “I am never the shopper” to “I am the only shopper.” Wald test of the equality of the Individual and Community coefficients. Significance levels are indicated as follows: *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

To determine whether the prime influences the propensity to donate or the size of the donation, we estimate a Logit model of the impact of the primes on the probability of donating a positive amount and a truncated model that includes only the positive donation occurrences and excludes the zeros (Supporting Information: Table A.2.7 in Appendix A.2). Thinking about COVID‐19 decreases the probability of donating though not significantly in most specifications, but increases the amount donated if donating, with a significant coefficient for the Community prime (1314 respondents). Overall, the reduction in the probability of making a positive donation more than offsets the increase in donations, hence the lower expected donation for prime groups.12

While ex‐ante statistical power assessments were infeasible due to the lack of priors on the pandemic's possible impact on donation to the charities, we perform an ex‐post analysis. This helps us distinguish whether the null result in the donation choice indicates low statistical power or a no substantive effect of the primes (Brown et al., 2009). The analysis shows that at a significance level of 5%, given our sample size of 1650 respondents and the control mean and standard deviation, we have 80% power to detect effects of 0.168 standard deviations of the control for the two COVID‐19 primes, and of 0.17 standard deviations for the Community prime. This translates into a minimum detectable effect of 1.59 for the two primes (10.97% of the control group mean). Since the effect size we find in the Tobit and OLS models (Table 4 and Supporting Information: Table A.2.6) are smaller than the minimum detectable effect, the lack of significance in the results might be driven by a lack of statistical power due to the standard deviation of responses.

4.4. Heterogeneous effects

4.4.1. Heterogeneity by intensity of COVID‐19 experience

We now examine a possible different source of heterogeneity in treatment effects. The primes’ effect likely depends on the intensity of COVID‐19 experienced in terms of whether respondents themselves or anyone in their families had been infected with COVID 19 or lost their job because of the pandemic. Therefore, we classify respondents depending on whether they reported having had a “Mild experience” (i.e., lower than average) or “Strong experience” with COVID‐19. Participants’ experience with COVID‐19 is defined as the average of the four questions: (i) Did you yourself get infected with COVID‐19?; (ii) Did anyone in your family or close circle of friends get infected with COVID‐19?; (iii) Did you lose your job or were your work hours reduced because of the pandemic?; and (iv) Did anyone in your family or close circle of friends lose their job because of the pandemic? The Individual prime reduces the price premium significantly and the coefficient is larger in magnitude when considering the impact of the COVID‐19 experience, while the effect of the Community prime reduces and is not significant when considering local meat or average premium (Table 5). The impact of the primes on donations differs based on COVID‐19 experience. When controlling for COVID‐19 experience, participants primed to think about COVID‐19 significantly increase the total amount donated to charity, in particular to World Central Kitchen. Participants with a “stronger” experience, instead, decrease the total amount donated to the three charities when primed, with a significant coefficient for donation to the food relief program. The different impact of the primes depending on COVID‐19 experience could explain the null effect of the prime on donations. Since participants with a strong COVID‐19 experience report significantly higher state anxiety, this result might be driven by a larger increase in anxiety when primed for respondents with a “stronger” COVID‐19 experience.

Table 5.

Tobit model of the impact of COVID‐19 primes by COVID‐19 experience

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average premium | Premium for local produce | Premium for local meat | Total donation | Farm aid | Farmers market coalition | World central kitchen | |

| Individual | −11.240** | −10.368* | −13.736*** | 2.855* | 0.105 | 0.587 | 2.303** |

| (4.462) | (5.323) | (5.271) | (1.572) | (0.890) | (0.790) | (0.995) | |

| Community | −6.878 | −9.550* | −5.859 | 2.322 | −0.116 | −0.862 | 2.192** |

| (4.510) | (5.384) | (5.327) | (1.597) | (0.902) | (0.808) | (1.009) | |

| Strong COVID experience | 4.170 | 3.609 | 5.017 | 1.701 | 1.126 | −0.012 | 2.332** |

| (4.334) | (5.173) | (5.125) | (1.513) | (0.856) | (0.765) | (0.962) | |

| Strong COVID experience × Individual | 6.031 | 2.843 | 10.266 | −3.118 | −0.736 | −1.221 | −3.841*** |

| (6.182) | (7.373) | (7.307) | (2.169) | (1.228) | (1.095) | (1.373) | |

| Strong COVID experience × Community | 1.658 | 6.950 | −2.987 | −2.840 | −0.986 | 0.617 | −3.111** |

| (6.219) | (7.423) | (7.347) | (2.191) | (1.236) | (1.107) | (1.381) | |

| Observation | 1650 | 1650 | 1650 | 1650 | 1650 | 1650 | 1650 |

| Wald's test | 0.956 | 0.024 | 2.240 | 0.114 | 0.061 | 3.317 | 0.013 |

| Significance | (p = 0.328) | (p = 0.878) | (p = 0.135) | (p = 0.736) | (p = 0.804) | (p = 0.069) | (p = 0.910) |

Note: Average premium measured as average of the price premium participants state to be willing to pay for local produce and local meat, on a scale from −100 to 100. Premium for local produce and premium for local meat are the average price premium that participants state to be willing to pay for local fruits and vegetables and local meat products respectively, on a scale from −100 to 100. Total donation is the total amount of the $25 bonus participants donate to the three charities. Average donation to each charity is reported in columns 5–7 Individual is a dummy variable taking value 1 for participants primed to think about the individual impact of COVID‐19. Community is a dummy variable taking value 1 for participants primed to think about the impact on their local community of COVID‐19. Strong COVID‐19 Experience is a dummy variable taking value 1 for participants with an experience with COVID‐19 higher than average, where COVID‐19 experience is measured as the average answer of the four questions: (i) Did you yourself get infected with COVID‐19?; (ii) Did anyone in your family or close circle of friends get infected with COVID‐19?; (iii) Did you lose your job or were your work hours reduced because of the pandemic?; and (iv) Did anyone in your family or close circle of friends lose their job because of the pandemic? Wald test of the equality of the Individual and Community coefficients. Significance levels are indicated as follows: *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

4.4.2. Heterogeneity by state anxiety and sense of community belonging

We now examine the impact of COVID‐19 depending on the reported State Anxiety and Sense of Community and present these results in Table 6. Throughout this paper, we hypothesize that the impact of COVID‐19 on price premium for local food and donations depends on its impact on State Anxiety and Sense of Community. We classify respondents depending on whether they reported a State Anxiety higher than average (“High Anxiety”) and on whether they reported a Sense of Community higher than average (“High Community”). We then analyze whether the primes have a differential impact on people with a high response to the prime in terms of anxiety and sense of community belonging by interacting our primes with these two dummy variables.

Table 6.

Tobit model of the impact of COVID‐19 primes by state anxiety and sense of community

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average premium | Premium for local produce | Premium for local meat | Total donation | Farm aid | Farmers market coalition | World central kitchen | |

| Individual | −1.480 | −1.992 | 0.241 | 3.836** | 0.813 | 0.513 | 1.722 |

| (4.758) | (5.690) | (5.626) | (1.704) | (0.969) | (0.866) | (1.082) | |

| Community | −4.602 | −5.946 | −3.866 | 4.448*** | 0.986 | 0.069 | 1.783* |

| (4.692) | (5.614) | (5.545) | (1.697) | (0.957) | (0.859) | (1.069) | |

| High anxiety | 10.700** | 10.786** | 13.926*** | 4.677*** | 2.429*** | 1.712** | 1.721* |

| (4.274) | (5.129) | (5.070) | (1.505) | (0.852) | (0.761) | (0.958) | |

| High anxiety × Individual | −11.922* | −10.430 | −16.978** | −3.189 | −1.624 | −0.325 | −2.393* |

| (6.097) | (7.307) | (7.225) | (2.161) | (1.225) | (1.092) | (1.372) | |

| High anxiety × Community | −0.694 | 0.462 | −2.513 | −5.494** | −2.857** | −0.791 | −1.930 |

| (6.131) | (7.356) | (7.263) | (2.182) | (1.233) | (1.102) | (1.380) | |

| High sense of community | 21.434*** | 22.228*** | 23.860*** | 3.309** | 1.465 | 1.929** | 0.682 |

| (4.622) | (5.553) | (5.487) | (1.619) | (0.912) | (0.814) | (1.028) | |

| High community × Individual | −1.753 | −5.498 | −0.548 | −3.781 | −1.174 | −1.242 | −0.973 |

| (6.745) | (8.085) | (7.996) | (2.378) | (1.344) | (1.197) | (1.511) | |

| High community × Community | −2.436 | 0.609 | −6.975 | −3.251 | −0.812 | −0.592 | −1.206 |

| (6.741) | (8.095) | (7.986) | (2.386) | (1.344) | (1.198) | (1.506) | |

| Observation | 1650 | 1650 | 1650 | 1650 | 1650 | 1650 | 1650 |

| Wald's test | 0.422 | 0.473 | 0.523 | 0.124 | 0.031 | 0.255 | 0.003 |

| Significance | (p = 0.516) | (p = 0.492) | (p = 0.470) | (p = 0.725) | (p = 0.860) | (p = 0.613) | (p = 0.955) |

Note: Average premium measured as average of the price premium participants state to be willing to pay for local produce and local meat, on a scale from −100 to 100. Premium for local produce and premium for local meat are the average price premium that participants state to be willing to pay for local fruits and vegetables and local meat products respectively, on a scale from −100 to 100. Total donation is the total amount of the $25 bonus participants donate to the three charities. Average donation to each charity is reported in columns 5‐7. Individual is a dummy variable taking value 1 for participants primed to think about the individual impact of COVID‐19. Community is a dummy variable taking value 1 for participants primed to think about the impact on their local community of COVID‐19. High Anxiety is a dummy variable taking value of 1 for participants reporting a level of state anxiety larger than the average (median). High Community is a dummy variable taking value of 1 for participants reporting a sense of community higher than the average (median). Wald's test of the equality of the Individual and Community coefficients. Significance levels are indicated as follows: *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

The impact of the primes on the price premium among people with low anxiety and sense of community is mostly negative but nonsignificant. While high anxiety increases the price premium among people in the control group, it largely decreases the price premium for participants primed to think about the individual impact of COVID‐19. Subjects with a high sense of community belonging also report a significantly larger price premium for local produce, while the impact of the prime on this group decreases slightly and non‐significantly the price premium. These results confirm that the impact of the prime on price premium is mostly driven by the level of state anxiety.

With respect to donations, thinking about COVID‐19 increases the total amount donated for participants with low anxiety and sense of community. While having high anxiety and a high sense of community generally increases donation, thinking about COVID‐19 decreases the amount donated for participants with high anxiety. In particular, the effect is significant for participants with high anxiety primed to think about the impact of COVID‐19 on their community. This finding indicates that thinking about the pandemic does influence donation, though differently depending on the response in terms of anxiety: for those who do not experience high anxiety it increases generosity by increasing donations; for those experiencing high anxiety, donations and generosity are instead decreased.

5. CONCLUSION

The coronavirus pandemic has brought several changes in the food system, consumers’ behavior towards local food, and concern about their local communities. Local food outlets have received significantly more attention from consumers, and many in the local food community wonder if this interest will continue beyond the pandemic. We use a survey experiment to investigate the impact of COVID‐19 on consumer preferences for local food and for supporting farmers, farmers markets, and a food aid program. Based on previous literature we test two hypotheses. First, if consumers’ anxiety increases when reminded of the COVID‐19 pandemic, this increase may reduce ethical behavior and reduce the price premium for local food and donation to charities. However, external threats are shown to increase the sense of belonging in a community. We hence hypothesize that the price premium for local food increases, together with charitable donations, when reminded of the COVID‐19 pandemic.

In the survey, we divide participants into a control group and two treatments groups where we prime participants by asking them about either the personal impact or the community impact of the pandemic. We then measure preferences for local food by asking participants their price premium for local fruits and vegetables and local meat products with an “unfolding bracket methods.” The results show that priming participants to think about COVID‐19 reduces the price premium for all local foods, and also for local produce and meat individually. There are, however, no differences between Individual and Community priming. A deeper analysis reveals that respondents’ state of anxiety plays a particularly important role in mediating the effect of COVID‐19: that is, we find that the reduction of price premium for local food is being driven mostly by participants with high state anxiety.

We also investigate whether thinking about the pandemic has changed the support for farmers, farmers market, and the local food program with an incentivized donation decision. We ask participants whether they want to donate part of a $25 bonus, should they be selected to receive the bonus, to Farm Aid, the Farmers Market Coalition, or the World Central Kitchen. Participants could allocate any portion of the $25 to themselves or each of the three charities. While priming appears to decrease the probability of donating and increase the amount of donation, the results are statistically insignificant. Overall, the reduction in probability of donating is more than offset by the increase in the amount donated which reveals itself as a positive, but insignificant, association between priming and the total amount of donation. In addition, there are no differences between Individual and Community priming. An ex‐post power calculation shows that these null results might be driven by the low statistical power of our estimates, due to the standard deviation of responses in our survey. Similarly, to the results on price premium, state anxiety importantly mediates the impact of thinking about COVID‐19 on donations. While participants with low state anxiety increase their donations after the prime, participants with high state anxiety largely reduce their donations.

We find that priming participants to think about COVID‐19 significantly increases anxiety, slightly decreases sense of community, and reduces the price premium for all local foods. Regarding the demand for local food, our findings support previous research that found that consumers “were simply buying the food they could get due to out of stock situations” (Chenarides et al., 2021). Overall, when people are alarmed/distressed/scared (anxious), not only they are less likely to pay a higher price premium for local food, but they also get less charitable; hence one would expect to observe that places hit harder by a pandemic to be less supportive of local food systems and charitable in comparison to the ones that did not. One conclusion from this study is that crisis‐induced anxiety is an important factor affecting people's choices and behavioral outcomes, and thus managing individuals’ anxiety could be added to the suite of public health policies during future crises.

Our research finding is particularly important for two reasons: first, it shows that both priming treatments did have an impact on participants even though the pandemic might have already elevated their anxiety levels; and second, it suggests the main mechanism through which the two priming treatments affect participants’ choices. Compared to the Individual prime, the Community prime has no separably different impact on participants’ sense of community and only a weakly different impact on anxiety levels. In other words, for an experiment that attempts to explore the potentially countervailing forces of pandemic‐driven increased personal concerns and community‐mindedness, we find that these forces remain difficult to disentangle because reinforcing primes about the pandemic's impact on individuals and community both increase anxiety levels, which appears to be the main driver behind our experimental outcomes.

To successfully disentangle the effect of personal concerns versus community concerns raised by COVID‐19, a differently targeted survey might be required. For example, to ensure that participants have similar community reference points before the priming treatments, an alternative survey might need to focus on a single community (or perhaps multiple specific communities). Additionally, to ensure that participants have similar individual reference points before the priming treatments, a survey might need to be targeted so that participants can be separated into subsamples with similar Covid‐19 experiences—that is, a subsample of people who got infected, a subsample of people who lost their jobs, etc. Even better, a large‐enough survey strategically targeted to both communities and individuals would allow researchers to investigate the role of one while controlling for the other. This type of targeted survey, in conjunction with the two priming treatments, might successfully disentangle personal concerns from community concerns.

Our study has several limitations, some specific to our design and some more general. Given the ubiquity of COVID‐19 reporting and impacts, COVID‐19 is likely present in participants’ minds, regardless of priming. Our treatment is therefore only amplifying its impact on the responses. We therefore control for participants’ experience of COVID‐19, measured in terms of having been infected, having lost their job, or having a close family member becoming infected or losing a job, in our analysis. There are no significant differences between “mild” and “strong” COVID‐19 experiences for the price premium, except for local meat, where strong experience further reduces the price premium for the community relative to individual priming. With respect to donations, priming significantly increases the amount donated when controlling for COVID‐19 experience, especially with respect to support for the food relief program. Priming instead decreases the amount donated among respondents with a “strong” COVID‐19 experience, with a significant coefficient for the donation to the food relief program, possibly because it increases anxiety more in this subgroup.

Moreover, the price premium for local food is a hypothetical measure. Even though the treatment effect of the primes is likely not affected by this issue, we try to mitigate hypothetical bias with several approaches. Our measure of the price premium is similar to the one used in Falk et al. (2016) to elicit risk‐taking and time discounting in surveys since it is very comparable to the incentivized experimental measures. We also ask respondents to commit to answering accurately and increase consequentiality by stating that the survey responses would inform policy making.

6. ETHICS STATEMENT

Ethical approval to conduct the study was obtained from the IRB office at Penn State.

Supporting information

Supplementary information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Kathryn J. Brasier, Francesco Colombo, Linlin Fan, Karen Fisher‐Vanden, Carola Grebitus, Yizao Liu, Nadia Streletskaya, and Katherine Y. Zipp for their helpful comments. This project is funded by a Rapid Response to COVID‐19 Grant by the College of Agricultural Sciences Institute for Sustainable Agricultural, Food, and Environmental Science. We also acknowledge support by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture and Hatch Appropriations under Project number PEN04709 and Accession number 1019915.

Biographies

Martina Vecchi is an Assistant Professor of Agricultural Economics in the Department of Agricultural Economics, Sociology, and Education at Penn State University, University Park, PA, USA. There are two broad themes to her research, one focused on food decision‐making and health and one focused on environmental and sustainable choices, that she investigates in a behavioral and experimental framework.

Edward C. Jaenicke is a Professor of Agricultural Economics in the Department of Agricultural Economics, Sociology, and Education at Penn State University, University Park, PA, USA. His research focuses on the economic modeling of food purchase behavior, the link between food behavior and health, food waste, and organic food and agriculture.

Claudia Schmidt is an Assistant Professor of Marketing and Local/Regional Food Systems in the Department of Agricultural Economics, Sociology, and Education at Penn State University, University Park, PA, USA. Her research focuses on small‐medium scale agricultural producer and processor issues within the network of local food systems.

Vecchi, M. , Jaenicke, E. C. , & Schmidt, C. (2022). Local food in times of crisis: The impact of COVID‐19 and two reinforcing primes. Agribusiness, 1–24. 10.1002/agr.21754

Footnotes

Washington State was inadvertently included (instead of Washington, DC) by the survey provider.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at The Pennsylvania State University and was pre‐registered in the AEA RCT registry under the following trial ID: AEARCTR‐0006755.

The full experimental instructions given to participants can be found in Supporting Information: Appendix B.

Participants were not aware of the odds of getting the $25 bonus incentive, which was of 6%. We selected a larger incentive (the $25 bonus) with a small probability since individuals tend to overweight small probabilities (Tversky & Kahneman, 1992). Moreover, several studies report that paying a subset of participants allows to minimize transaction costs and does not lead to significant difference from the full payment method (Voslinsky & Azar, 2021).

We compute the difference in donations between Farm Aid and Farmers Market coalition, between Farmers Market Coalition and World Central Kitchen, between Farm Aid and World Central Kitchen, and compare these differences across treatment groups with an F‐test of equality.

Controlling in the regression models for several observables collected in the survey does not modify the results of the analysis. The controls include: percentage of local food purchased last month; definition of local; motives for buying local food; altruism; charitable giving behavior; familiarity with the three charities; living area (urban, suburban, or rural).

It should be relatively clear that the empirical model given by Equation (1), for either the elicited price premium or the donation amount, is not a structural model in the sense that it flows directly from a utility‐maximizing decision. Rather, it can be thought of as a reduced‐form model meant to investigate the participant‐specific factors that influence the preferences underlying such a decision.

The discrepancy between the question measuring altruism and charitable giving likely depends on charitable giving being more linked to annual income (correlation with income of 0.307 for charitable giving, and of 0.113 for altruism).

Supporting Information: Table A.2.4 in Appendix A.2 reports the estimation for price premium with ordinary least squares (OLS) models.

Since the error terms could be correlated across price premium equations for local produce and for local meat, we also estimate Bivariate Tobit models and Seemingly Unrelated Regressions for these outcomes. These models produce results very similar to the ones showed in the manuscript tables.

Significance based on t‐tests and F‐tests of equality across groups. An exploratory analysis of the difference between the three charities seems to indicate that being reminded about the impact of the pandemic slightly increases donations to food relief programs, while this might not be the case with charities supporting farmers or farmers markets as participants may not closely relate with farmers or feel the need to help them. If we analyze the effect of the prime on individuals working in farming, fishing, and forestry we find that the impact of the Community prime is positive on donations to Farm Aid, positive and significant for donations to Farmers Market Coalition, and negative and significant for donations World Central Kitchen since these participants might feel closer to farmers and farmers markets (Supporting Information: Table A.2.5 in Appendix A.2.).

Supporting Information: Table A.1.3 in Appendix A.1 reports the analysis with the subsample of people willing to commit to providing truthful answers. Supporting Information: Table A.2.6 in Appendix A.2 reports the estimations for donation with ordinary least squares (OLS) models.

We also estimate a Factional Multinomial Logit model with the shares of the $25 bonus participants keep to themselves and donate to each of the charities. The results of this model show the same pattern of significance as those shown in Table 4. The two treatment variables Individual and Community are not significant, while annual income has a significant impact on donations to each of the three charities.

Since the error terms could be correlated across equations for the propensity to donate and the amount donated, we also estimate a multi‐equation, Mixed Process model. We simultaneously estimate a Probit model for the propensity to donate and a Truncated Regression model for the amount donated. The results are very similar to the ones shown in Supporting Information: Table A.2.7 in Appendix A.2.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

REFERENCES

- Adams, D. C. , & Adams, A. E. (2011). De‐placing local at the farmers' market: Consumer conceptions of local foods. Journal of Rural Social Sciences, 26(2), 4. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S. H. , Imbruce, V. M. , Russo, R. G. , Kaplan, S. , Stevenson, K. , Mezzacca, T. A. , Foster, V. , Radee, A. , Chong, S. , Tsui, F. , & Kranick, J. (2021). Evaluating closures of fresh fruit and vegetable vendors during the COVID‐19 pandemic: Methodology and preliminary results using omnidirectional street view imagery. JMIR Formative Research, 5(2), e23870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargh, J. A. , & Chartrand, T. L. (2014). The mind in the middle: A practical guide to priming and automaticity research. In Reis H. T. & Judd C. M. (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology (pp. 311–344). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bean, M. , & Sharp, J. S. (2011). Profiling alternative food system supporters: The personal and social basis of local and organic food support. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, 26, 243–254. [Google Scholar]

- Bender, K. E. , Badiger, A. , Roe, B. E. , Shu, Y. , & Qi, D. (2021). Consumer behavior during the COVID‐19 pandemic: An analysis of food purchasing and management behaviors in US households through the lens of food system resilience. Socio‐Economic Planning Sciences, 101107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Birch, D. , Memery, J. , & Kanakaratne, M. D. S. (2018). The mindful consumer: Balancing egoistic and altruistic motivations to purchase local food. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 40, 221–228. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, E. , Dury, S. , & Holdsworth, M. (2009). Motivations of consumers that use local, organic fruit and vegetable box schemes in Central England and Southern France. Appetite, 53(2), 183–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callen, M. , Isaqzadeh, M. , Long, J. D. , & Sprenger, C. (2014). Violence and risk preference: Experimental evidence from Afghanistan. American Economic Review, 104(1), 123–148. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, B. L. , Mhlanga, S. , & Lesschaeve, I. (2013). Perception versus reality: Canadian consumer views of local and organic. Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics/Revue canadienne d'agroeconomie, 61(4), 531–558. [Google Scholar]

- Cappelen, A. W. , Falch, R. , Sørensen, E. Ø. , & Tungodden, B. (2020). Solidarity and fairness in times of crisis (NHH Department of Economics Discussion Paper, 06).

- Cappelli, A. , & Cini, E. (2020). Will the COVID‐19 pandemic make us reconsider the relevance of short food supply chains and local productions? Trends in Food Science & Technology, 99, 566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpiano, R. M. , & Hystad, P. W. (2011). “Sense of community belonging” in health surveys: what social capital is it measuring? Health & Place, 17(2), 606–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpio, C. E. , & Isengildina‐Massa, O. (2009). Consumer willingness to pay for locally grown products: the case of South Carolina. Agribusiness: An International Journal, 25(3), 412–426. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, S. , Lobb, A. , Butler, L. , Harvey, K. , & Traill, W. B. (2007). Local, national and imported foods: A qualitative study. Appetite, 49(1), 208–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenarides, L. , Grebitus, C. , Lusk, J. L. , & Printezis, I. (2021). Food consumption behavior during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Agribusiness, 37(1), 44–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cibelli, K. (2017). The effects of respondent commitment and feedback on response quality in online surveys [Doctoral dissertation].

- Cohn, A. , Engelmann, J. , Fehr, E. , & Maréchal, M. A. (2015). Evidence for countercyclical risk aversion: an experiment with financial professionals. American Economic Review, 105(2), 860–885. [Google Scholar]

- Cohn, A. , & Maréchal, M. A. (2016). Priming in economics. Current Opinion in Psychology, 12, 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Conner, D. , Colasanti, K. , Ross, R. B. , & Smalley, S. B. (2010). Locally grown foods and farmers markets: Consumer attitudes and behaviors. Sustainability, 2(3), 742–756. [Google Scholar]

- Cornsweet, T. N. (1962). The staircase‐method in psychophysics. The American Journal of Psychology, 75(3), 485–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CPG FMCG & Retail . (2020). COVID‐19 concerns are a likely tipping point for local growth. Nielsen. https://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/article/2020/covid-19-concerns-are-a-likely-tipping-point-for-local-brand-growth/

- Cranfield, J. , Henson, S. , & Blandon, J. (2012). The effect of attitudinal and sociodemographic factors on the likelihood of buying locally produced food. Agribusiness, 28(2), 205–221. [Google Scholar]

- Cranfield, J. A. (2020). Framing consumer food demand responses in a viral pandemic. Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics/Revue canadienne d'agroeconomie, 68(2), 151–156. [Google Scholar]

- Darby, K. , Batte, M. T. , Ernst, S. , & Roe, B. (2008). Decomposing local: A conjoint analysis of locally produced foods. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 90(2), 476–486. [Google Scholar]

- Dunne, J. B. , Chambers, K. J. , Giombolini, K. J. , & Schlegel, S. A. (2011). What does' local' mean in the grocery store? Multiplicity in food retailers' perspectives on sourcing and marketing local foods. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, 26, 46–59. [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson, H. , Thilmany McFadden, D. D. , & Jablonski, B. B. (2021). Exploring changes in local food purchasing patterns during COVID‐19: Insights from a nationwide consumer survey. https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/312859/files/Abstracts_21_06_15_22_08_52_13__24_9_64_193_0.pdf

- Elias, J. J. , Lacetera, N. , & Macis, M. (2019). Paying for kidneys? A randomized survey and choice experiment. American Economic Review, 109(8), 2855–88. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison, B. , McFadden, B. , Rickard, B. J. , & Wilson, N. L. (2021). Examining food purchase behavior and food values during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 43(1), 58–72. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, A. , Becker, A. , Dohmen, T. , Enke, B. , Huffman, D. , & Sunde, U. (2018). Global evidence on economic preferences. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 133(4), 1645–1692. [Google Scholar]