Abstract

Black Americans are disproportionately represented among coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19)‐related morbidities and mortalities. While the COVID‐19 vaccines are positioned to change this disparity, vaccine hesitancy, attributed to decades of systemic racism and mistreatment by the United States health care system, heavily exists among this racially and ethnically minoritized group. In addition, social determinants of health within Black communities including the lack of health care access and inequitable COVID‐19 vaccine allocation, further impacts vaccine uptake. Black pharmacists have worked to address the pandemic's deleterious effects that have been recognized within Black communities, as they are intimately aware of the structural and systematic limitations that contribute to lower vaccination rates in comparison to other racial and ethnic groups. Black pharmacists have been integral to promoting equity in COVID‐19 uptake within Black communities by disseminating factual, trustworthy information in collaboration with community leaders, advocating for the equitable access to the immunizations into vulnerable areas, and creating, low‐barrier, options to distribute the vaccines. Herein, we thoroughly explain these points and offer a framework that describes the role of Black pharmacists in narrowing vaccine equity gaps.

Keywords: Black Americans, COVID‐19, pharmacists, vaccines

1. INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) continues to have a significant global impact since the initial discovery of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus‐2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) pathogen. As of May 2022, greater than 83 million individuals in the United States have been infected with the virus, resulting in more than 1 000 000 fatalities. 1 To date, Black Americans are twice as likely to be hospitalized due to COVID‐19 when compared with their White counterparts. 2 This disparity is heavily attributed to the interrelationship of structural racism and inequities in social determinants of health. 3 These inequities include the occupancy of essential‐worker roles, as well as systematically oppressive housing policies that result in higher density living arrangements. 4 Unfortunately, these circumstances place Black individuals at increased risk of transmitting and/or contracting SARS‐COV‐2.

The availability of the COVID‐19 vaccines serves as a beacon of hope; however, centuries of mistreatment of Black individuals at the hands of the United States' health care system have resulted in the warranted mistrust of the vaccination process. 5 , 6 While the lack of trusted messaging, resulting in decreased confidence, contributes to the reduced vaccine uptake within Black communities, the inequitable allocation and access of the available COVID‐19 vaccines has also been an evident issue. 7 Of the greater than 500 million COVID‐19 vaccines that have been administered in the United States, 10% have been administered to Black Americans. This percentage is substantially disproportionate to their representation among COVID‐related mortalities (reported to be 14% as of February 2022). 1 , 8

Irrespective of their historical underrepresentation in the pharmacy profession, Black pharmacists have a distinct role in promoting health equity within Black communities and this has been amplified during the COVID‐19 pandemic. 9 , 10 Herein, we describe the barriers to COVID‐19 vaccination within Black communities. We also propose a framework that discusses the impact that Black pharmacists have on promoting equity in COVID‐19 vaccine uptake within Black communities specifically as it pertains to delivering pertinent vaccination education, building trustworthy relationships, and creating opportunities for equitable access to COVID‐19 vaccines.

2. BLACK PHARMACISTS AND SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH WITHIN BLACK COMMUNITIES

The intersection of racism and social determinants of health influence the negative health outcomes recognized among Black Americans. 4 Black individuals are often unable to complete college level degrees due to structural racism, which severely limits their employment opportunities. 11 Thus, these individuals are less likely to have health insurance, preventing access to health care providers when compared with their White counterparts. 11 , 12 Further, Black Americans were reported as being 15% more likely, when compared with White Americans, not to have a primary care provider due to associated costs. 12 While the expansion of Medicaid with the Affordable Care Act has sought to change this, several states that have elected not to implement the expansion have exacerbated these inequalities.

As these systemic roadblocks have severely impacted health care access in Black communities, Black pharmacists have worked to mitigate the health disparities. For Black patients that lack health insurance and the ability to receive routine care, several Black pharmacists have created ambulatory care clinics dedicated to providing education on the management of prevalent chronic disease states within Black communities (ie, hypertension, lipidemia, and diabetes). 10 Other Black pharmacists have developed programs in rural Black communities that are centered on teaching patients how to access affordable insurance and medication services. Ultimately, these pharmacists have turned their care settings into hubs for culturally competent care, earning the respect and trust of the Black communities that they serve. Using this established foundation for closing cultural gaps, Black pharmacists have been essential in addressing several key limitations in vaccine uptake among Black Americans, including uncertainties surrounding the COVID‐19 vaccine and inadequate access to immunizations.

3. COVID‐19 VACCINE HESITANCY WITHIN BLACK COMMUNITIES

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), vaccine hesitancy can be attributed to three factors including complacency, convenience, and confidence. 13 Within this definition, confidence signifies trust in the effectiveness and safety of vaccines, as well as the system that delivers them. 13 Historically, this described trust in vaccines has been shattered within Black communities, credited in part to the egregious Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male that occurred in Tuskegee, Alabama between 1932 and 1972. 14 The United States Public Health Service conducted this study on over 300 men without notifying them of their syphilis disease or an available treatment. Unfortunately, the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male is not a monolith in the United States government's medical injustices committed against Black Americans. The illegal extraction and inclusion of Black persons' DNA in clinical research, the involuntary sterilization of Black women, and the overall lack of empathy that Black individuals receive from health care providers further contribute to their fragile relationships with science and ultimately modern medicine. 15 , 16 , 17

These aforementioned events are all likely factors in the decreased willingness that Black individuals have in adopting vaccines as a measure to prevent respiratory infectious diseases (ie, influenza) as persistent racial and ethnic disparities have been observed. 17 Prior to the COVID‐19 pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported racial/ethnic disparities in influenza vaccine uptake. A CDC analysis of influenza hospitalization rates by race and ethnicity during 10 flu seasons from 2009 to 2019 demonstrated that non‐Hispanic Black persons had the highest influenza‐related hospitalization rates (68/100 000). 18 Among adults aged 18 years and older, influenza vaccination coverage during the 2019 to 2020 flu season was 53% among non‐Hispanic White persons as opposed to only 41% among non‐Hispanic Black individuals. 18 As a result, the CDC has worked to address this disparity among racial and ethnic groups by developing customized outreach to minoritized communities. These outreach efforts have included providing additional funding to state immunization programs with a specific focus on minoritized groups, and conducting research to uncover the root causes of the disproportionate influenza‐related hospitalizations. 18 While similar financial efforts have been placed towards mitigating lower COVID‐19 vaccination rates among minoritized groups, trustworthiness in health care and scientific entities as well as education about the vaccines and the developmental process from reliable resources, are of the utmost importance. 10

4. INEQUITABLE COVID‐19 VACCINATION ACCESS AND ALLOCATION WITHIN BLACK COMMUNITIES

In concert with hesitancy, inequitable COVIID‐19 vaccine allocation and access impacted COVID‐19 uptake within Black communities. The inaccessibility of the COVID‐19 vaccines within Black communities began during the initial stages of the COVID‐19 immunization rollout planning. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) suggested a phased COVID‐19 vaccine rollout plan as the demand for vaccines exceeded the supply of the national COVID‐19 vaccination program. 19 , 20 Vaccines were prioritized for individuals aged 75 years or older; however, the average life expectancy for Black Americans is reported as 72 years old. 21 To this, many Black individuals were excluded despite their increased likelihood of severe COVID‐19 illness and disproportionate‐related mortality risks. 22 , 23 , 24

This exclusion exists in tandem with additional hurdles that impact COVID‐19 vaccine access. The lack of access to technology, resultant of the digital divide recognized across minoritized communities, had exposed the difficulties in locating vaccination sites and navigating vaccination registration web pages. 25 , 26 Further, vaccination schedules often concluded during early evening hours, which served as a disadvantage to Black individuals as the wages of their essential occupations are typically paid hourly, which may preclude them from the autonomy of adjusting their work schedules to complete vaccination appointments. 11 , 27 Vaccination opportunities that are inaccessible by public transportation were an additional factor that may have negatively impacted uptake, as Black individuals are more likely to be reliant on mass transit modalities. 28 , 29

5. A PROPOSED FRAMEWORK FOR LEVERAGING BLACK PHARMACISTS TO PROMOTE EQUITY IN COVID‐19 UPTAKE WITHIN BLACK COMMUNITIES

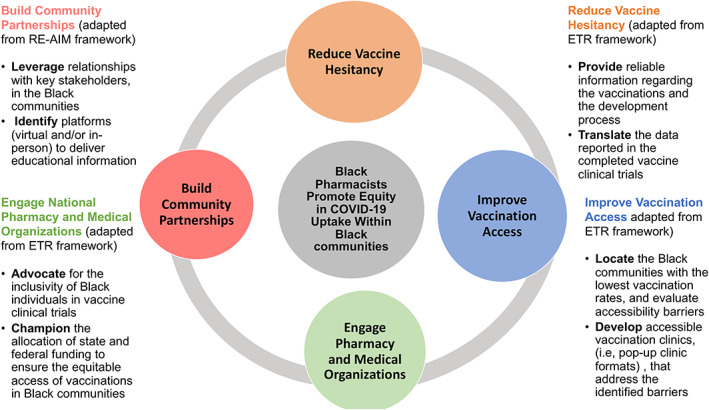

Various frameworks have been developed and applied to support health equity approaches in clinical practice. The science and justice health equity framework (HEF) developed by ETR—a national non‐profit organization with a mission to advance health equity through education, training, and research—describes the need for minoritized communities to have fair access to resources and opportunities in order to have positive health outcomes. 30 The framework also explains that systems of power which include policies, practices, and processes have a direct impact on fair health care access. It further states that relationships and networks, that may include trusted and familiar health care professionals, potentially have a place in promoting health equity. Additionally, the implementation science framework, reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, maintenance (RE‐AIM), focuses on the need for the engagement and inclusion of community stakeholders in the sustainability of health equity interventions. 31 Despite the insights that these frameworks provide, neither explicitly describes the role or influence that clinicians, specifically pharmacists, have in promoting health and vaccine equity, particularly within Black communities. The framework proposed in Figure 1 incorporates applicable aspects of RE‐AIM and ETR frameworks—with the gaps that Black pharmacists have been shown to fill within Black populations—to describe the unique influence that Black pharmacists have on promoting COVID‐19 equity in COVID‐19 within Black communities.

FIGURE 1.

Black pharmacists promote equity in COVID‐19 vaccine uptake within the Black communities framework. 7 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 COVID‐19, coronavirus disease 2019; RE‐AIM, reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, maintenance framework

6. REDUCTION OF VACCINE HESITANCY THROUGH COMMUNITY PARTNERSHIPS

The impact that Black pharmacists have had on the delivery of COVID‐19 vaccine‐related education to reduce hesitancy within Black communities has been documented through several public health efforts. 7 , 32 Moreover, community‐based partnerships, that include Black pharmacists and influential Black community figures such as faith leaders or members of Black Greek organizations, have been shown to promote trusting relationships and positively influence vaccine uptake. 7 , 32 , 33 , 34 These partnerships, led by community leaders, have relied on the trusting infrastructure that they have cultivated to engage their respective Black community members in conversations designed to increase COVID‐19 vaccine confidence and uptake. 7 , 32 , 33 , 34

Further, the Pharmacy Initiative Leaders (PILs Connect Inc.), a nonprofit organization dedicated to empowering underrepresented pharmacy professionals, hosted a series of webinars aimed towards thwarting COVID‐19 vaccine misinformation. 35 , 36 These webinars were presented on an accessible virtual platform, promoted by several Black faith organizations, and held open to the public. The information sessions were led by a panel of five Black female pharmacists with specialized training in infectious diseases and provided a comprehensive overview of the COVID‐19 vaccines, outlined federal efforts for equitable distribution of the vaccines, and offered an opportunity for attendees to discuss their fears and concerns regarding the vaccines. To date, the posted videos have amassed over 1000 views on YouTube. 35 , 36 Jointly, these examples provide context on how community‐engaged partnerships, that include Black pharmacists, can be leveraged to reduce hesitancy and guide decision‐making surrounding the vaccines.

7. ENGAGEMENT OF NATIONAL PHARMACY AND MEDICAL ORGANIZATIONS

National pharmacy organizations have also incorporated their Black membership in their COVID‐19 educational and trustworthy messaging efforts within Black communities. The National Pharmaceutical Association (NPhA), a pharmacy organization dedicated to amplifying racially and ethnically minoritized pharmacists, collaborated with the National Medical Association (NMA) to evaluate COVID‐19 vaccines for safety and efficacy. 37 Members of NPhA then gave informational webinars to educate minoritized communities about COVID‐19 and the benefits of vaccination. 37 Additionally, several Black pharmacists, who were appointed members of the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists (SIDP) Diversity, Equity, Inclusion Committee, served as authors of a manuscript that provided insight into vaccine hesitancy amongst Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) and offered recommendations for an upward mobility of immunization uptake. 6 Also, the American Pharmacists Association (APhA) has hosted several webinars catered towards addressing vaccine hesitancy and the development of sustainable outreach strategies to increase vaccine uptake within minoritized communities. These webinars, in addition to the APhA Vaccine Confidence Learning Collaborative, have included Black pharmacists as participants and have relied heavily on their intimate connections, experiences, and insights to address vaccine uptake within Black communities. 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 Furthermore, the annual meetings of several national organizations, including APhA and NPhA, have offered several live educational sessions led by Black pharmacists discussing the importance of culturally competent education in addressing racial and ethnic disparities in adult immunizations. 42 , 43 The summation of these efforts showcase how Black pharmacists have continued to serve as experts on national platforms targeted towards increasing education and trustworthy messaging within Black communities regarding the COVID‐19 vaccines.

8. IMPROVEMENT OF COVID‐19 VACCINE ACCESS THROUGH ADVOCACY AND COMMUNITY OUTREACH

Black pharmacists have championed national advocacy efforts to bring awareness to the lack of vaccine access within minoritized communities. The NPhA, in partnership with SIDP, addressed the need for equitable access of vaccinations in Black communities. The organizations collaboratively penned a letter to federal government officials highlighting health inequities across minoritized groups, and provided explicit details on the efforts of pharmacists to reduce vaccination disparities. 44 The letter further expressed NPhA's strong opposition to the age restriction of the COVID‐19 vaccination roll‐out plan, as Black individuals aged 60 and older were shown to be heavily impacted by the COVID‐19 pandemic. The NPhA also penned a call to action that described the socialization and traumatization experienced by racially and ethnically minoritized groups and amplified the unique health care needs, including vaccination access, of these groups amid the COVID‐19 pandemic. 37

Further, Black pharmacists have created concentrated processes to overcome the barriers to vaccine access within Black communities highlighting their vitality as agents of change in public health, beyond the traditional community pharmacy immunization setting. 7 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 To this, Loma Linda University's partnership with several faith organizations, which began in January 2021 and is ongoing, resulted in an overwhelming representation of Black vaccines at a community vaccination clinic conducted at a familiar urban location. The clinic utilized a paper‐based registration form to avoid technology barriers and a Black pharmacist served as the lead clinician to cement the trusting relationship between the university and the community at large. 7 The lead pharmacist went on to conduct additional community vaccination clinics and incorporated creative tactics such as evening clinics to target individuals with scheduling conflicts due to employment to optimize equitable vaccination access. Overall, in these clinics, 83.7% of the vaccine attendees were Black persons, drastically differing from the non‐community vaccination clinic comparative approach, in which only 3% of the vaccines were Black individuals. 45 The methods and outcomes of this vaccination effort have been presented both nationally and internationally. 46 , 47 Mirroring this effort, Black pharmacists continue to create mobile vaccination clinics and other accessible community immunization modalities to serve urban and rural areas heavily populated by Black individuals. 39 , 48

Notably, Historically Black College and Universities (HBCUs) have utilized the COVID‐19 pandemic as a learning tool for future pharmacists on health care inequities and the placement of pharmacists in mitigating public health disparities. Howard University in Washington D.C. has mobilized their pharmacy students and clinical residents to provide vaccinations within inner‐city neighborhoods populated by minoritized individuals of lower socioeconomic statuses. 49 Further, Xavier University in Louisiana has commenced research, funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), centered on uncovering the root causes of vaccine hesitancy. The research, done in partnership with faith organizations, centers on the students of Xavier University's College of Pharmacy providing trustworthy COVID‐19 vaccination information and accessible options for the immunization of Black communities within the New Orleans, Louisiana area. 50 Ultimately, these described actions that include advocacy for the equitable allocation of the COVID‐19 immunizations as well as the creation of community vaccination initiatives, have served as sustainable mechanisms for creating access to the immunizations that Black individuals would not be privy to otherwise.

9. CONCLUSION

As trusted health care professionals, pharmacists are imperative in rectifying health care inequities recognized among minoritized communities. While structural and systemic racism have contributed largely to health care inequities observed in Black communities, Black pharmacists have worked to narrow these equity gaps. Using the proposed framework which includes building community partnerships, reducing vaccine hesitancy, engaging national professional organizations, and developing innovative vaccination strategies, Black pharmacists have shown the utility of their placement within Black communities during the COVID‐19 pandemic. They have also used their lived experiences to advocate on national platforms for the adequate inclusion of Black individuals in vaccine clinical trials and the urgent need for the equitable placement of preventive measures, including vaccinations, within Black communities. Perhaps the most important, Black pharmacists and historically Black institutions have created learning opportunities and models for professional students to engage in these equitable vaccination efforts, thus, identifying their role in mitigating health disparities. The COVID‐19 pandemic continues to have negative effects in Black communities, and Black pharmacists will be integral in altering these outcomes.

FUNDING INFORMATION

There was no external funding received for this research.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

J. A. M. has received an honorarium from Shionogi. The other authors have no conflicts of interest.

Abdul‐Mutakabbir JC, Simiyu B, Walker RE, Christian RL, Dayo Y, Maxam M. Leveraging Black pharmacists to promote equity in COVID‐19 vaccine uptake within Black communities: A framework for researchers and clinicians. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2022;5(8):887‐893. doi: 10.1002/jac5.1669

REFERENCES

- 1. COVID Data Tracker . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. December 2021. Available from: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#datatracker-home

- 2. CDC . Cases, data, and surveillance [Internet]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020 [cited 2021 Dec 17]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html

- 3. Kennedy BR, Mathis CC, Woods AK. African Americans and their distrust of the health care system: Healthcare for diverse populations. J Cult Divers. 2007;14(2):56–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Khazanchi R, Evans CT, Marcelin JR. Racism, not race, drives inequity across the COVID‐19 continuum. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2019933. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19933 PubMed PMID: 32975568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Warren RC, Forrow L, Hodge DA, Truog RD. Trustworthiness before trust – COVID‐19 vaccine trials and the Black community. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(22):e121. 10.1056/NEJMp2030033 PubMed PMID: 33064382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Marcelin JR, Swartz TH, Bernice F, et al. Addressing and inspiring vaccine confidence in Black, indigenous, and people of color during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8(9):ofab417. 10.1093/ofid/ofab417 PubMed PMID: 34580644; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8385873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Abdul‐Mutakabbir JC, Casey S, Jews V, et al. A three‐tiered approach to address barriers to COVID‐19 vaccine delivery in the Black community. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9(6):e749–e750. 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00099-1 PubMed PMID: 33713634; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7946412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. CDC . COVID‐19 vaccinations in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020 [cited 2021 Dec 24]. Available from: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker

- 9. 2019 National Pharmacist Workforce Study . American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. [cited 2021 Dec 23]. Available from: https://www.aacp.org/article/2019-national-pharmacist-workforce-study

- 10. Anthony C. How black pharmacists are closing the cultural gap in health care. NBC News. [cited 2022 Apr 6]. Available from: https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/how-black-pharmacists-are-closing-cultural-gap-health-care-n1021186

- 11. Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agenor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453–1463. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X PubMed PMID: 28402827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hill L, Artiga S, Haldar S. Key facts on health and health care by race and ethnicity – Health coverage and access to and use of care. KFF. Kaiser Family Foundation. Available from: https://www.kff.org/report‐section/key‐facts‐on‐health‐and‐health‐care‐by‐race‐and‐ethnicity‐health‐coverage‐and‐access‐to‐and‐use‐of‐care/

- 13. MacDonald NE, SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy . Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4161–4164. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036 PMID: 25896383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Park J. Historical origins of the Tuskegee experiment: The dilemma of public health in the United States. Uisahak. 2017;26(3):545–578. 10.13081/kjmh.2017.26.545 PubMed PMID: 29311536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Skloot R. The immortal life of Henrietta Lacks. New York: Crown Publishers, 2010. x, 369 p., 8 p. of plates p. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ko L. Unwanted sterilization and eugenics programs in the United States. PBS. Public Broadcasting Station [cited 2022 Apr 6]. Available from: https://www.pbs.org/independentlens/blog/unwanted-sterilization-and-eugenics-programs-in-the-united-states/

- 17. Hostetter M, Klein S. Understanding and ameliorating medical mistrust among Black Americans. The Commonwealth Fund. 2021 [cited 2022 Apr 6]. Available from: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/newsletter‐article/2021/jan/medical‐mistrust‐among‐black‐americans

- 18. CDC . Flu disparities among racial and ethnic minority groups. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021 [cited 2021 Dec 17]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/highrisk/disparities-racial-ethnic-minority-groups.html

- 19. Dooling K, McClung N, Chamberland M, et al. The advisory committee on immunization practices' interim recommendation for allocating initial supplies of COVID‐19 vaccine – United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(49):1857–1859. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6949e1 PubMed PMID: 33301429; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7737687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Committee on Equitable Allocation of Vaccine for the Novel Coronavirus . Framework for equitable allocation of COVID‐19 vaccine. In: Kahn B, Brown L, Foege W, Gayle H, editors. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health). [cited 2021 Dec 17]. Available from:. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US), 2020. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562672/. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Arias E, Tejada‐Vera B, Ahmad F. Provisional life expectancy estimates for January through June, 2020. National Center for Health Statistics (U.S.). 2021 [cited 2021 Dec 17]. Available from: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/100392

- 22. Wang Q, Berger NA, Xu R. Analyses of risk, racial disparity, and outcomes among US patients with cancer and COVID‐19 infection. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(2):220–227. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.6178 PubMed PMID: 33300956; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7729584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID‐19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2052–2059. 10.1001/jama.2020.6775 PubMed PMID: 32320003; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7177629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cunningham TJ, Croft JB, Liu Y, Lu H, Eke PI, Giles WH. Vital signs: Racial disparities in age‐specific mortality among Blacks or African Americans – United States, 1999–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(17):444–456. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6617e1 PubMed PMID: 28472021; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5687082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Corbie‐Smith G. Vaccine hesitancy is a scapegoat for structural racism. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2(3):e210434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Michaels IH, Pirani S, Carrascal A. Disparities in internet access and COVID‐19 vaccination in New York City. Prev Chronic Dis. 2021;18:E83. 10.5888/pcd18.210143. Available from:, https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2021/21_0143.htm. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bailey ZD, Feldman JM, Bassett MT. How structural racism works – Racist policies as a root cause of U.S. racial health inequities. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(8):768–773. 10.1056/NEJMms2025396 PubMed PMID: 33326717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Anderson M. Who relies on public transit in the U.S. Pew Research Center. [cited 2021 Dec 17]. 10.7759/cureus.24865. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/04/07/who-relies-on-public-transit-in-the-u-s/ [DOI]

- 29. Johnson A. Lack of health services and transportation impede access to vaccine in communities of color. The Washington Post. 2021 [cited 2022 Apr 6]. Available from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2021/02/13/covid-racial-ethnic-disparities/

- 30. Peterson A, Charles V, Yeung D, Coyle K. The health equity framework: A science‐ and justice‐based model for public health researchers and practitioners. Health Promot Pract. 2021;22(6):741–746. 10.1177/1524839920950730 PubMed PMID: 32814445; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8564233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shelton RC, Chambers DA, Glasgow RE. An extension of RE‐AIM to enhance sustainability: Addressing dynamic context and promoting health equity over time. Front Public Health. 2020;8:134. 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Peteet B, Belliard JC, Abdul‐Mutakabbir J, Casey S, Simmons K. Community‐academic partnerships to reduce COVID‐19 vaccine hesitancy in minoritized communities. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;34:100834. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fact vs fiction: fighting COVID‐19. Las Vegas Alumnae Chapter of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc. [cited 2021 Dec17]. Available from: https://lvacdst.org/events/fact-vs-fiction-fighting-covid-19/

- 34. Pharmacy, sorority, nurses team up for COVID‐19 vaccination event. WSOC TV. 2021 [cited 2021 Dec 17]. Available from: https://www.wsoctv.com/community/family‐focus/pharmacy‐sorority‐nurses‐team‐up‐covid‐19‐vaccination‐event/4I4MROFELBCQRCEYWVUIBKUOOQ/

- 35. CandID Conversations Vol. 2: frequently asked questions. [cited 2021 Dec 17]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T9iJp8r5I0c

- 36. CandID Conversations: COVID‐19 vaccine hesitancy in the Black community. [cited 2021 Dec 17]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L5so1F50nxY

- 37. Riley AC, Campbell H, Butler L, Wisseh C, Nonyel NP, Shaw TE. Socialized and traumatized: Pharmacists, underserved patients, and the COVID‐19 vaccine. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2021;61(6):e2–e5. 10.1016/j.japh.2021.05.020 PubMed PMID: 34147364; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8166458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. APhA Vaccine Confident . American Pharmacists Association. [cited 2022 Apr 7], 10.3310/BCFV2964. Available from: https://vaccineconfident.pharmacist.com/ [DOI]

- 39. Collins S. Philadelphia area pharmacist goes extra mile to reach underserved community. APhA Vaccine Confident. American Pharmacists Association. 2021 [cited 2022 Apr 7]. Available from: https://vaccineconfident.pharmacist.com/Share/Success‐Stories/Articles/Philadelphia‐Area‐Pharmacist‐Goes‐Extra‐Mile‐to‐Reach‐Underserved‐Community

- 40. COVID vaccinations: The patient who came back. 2021 [cited 2022 Apr 7]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DYcZSccS2mw

- 41. Open forum webinars . APhA. American Pharmacists Association. [cited 2022 Apr 7]. Available from: https://www.pharmacist.com/Practice/COVID‐19/Open‐Forum‐Webinars#:~:text=Addressing%20the%20COVID%2D19%20Crisis,by%20APhA%20President%20Sandra%20Leal

- 42. APhA 2022 annual meeting and exposition . U.S. Pharmacist. [cited 2022 Apr 7]. 10.3310/BCFV2964. Available from: https://www.uspharmacist.com/conferences/apha2022?wc_mid=6220:694704&wc_rid=6220:14321325 [DOI]

- 43. 2021 NPhA/SNPhA virtual convention. National Pharmaceutical Association. [cited 2022 Apr 7]. Available from: https://nationalpharmaceuticalassociation.org/event-4311016

- 44. Pharmacy organizations advocate for vaccine equity. Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. [cited 2021 Dec 17]. Available from: https://sidp.org/Pharmacy-Organizations-Advocate-for-Vaccine-Equity/

- 45. Abdul‐Mutakabbir J, Bouchard J, McCreary E. The VaxScene, a review of the COVID‐19 vaccine landscape in the US with a focus on equitable distribution and vaccine hesitancy. (Breakpoints – The SIDP Podcast). Available from: https://podcastaddict.com/episode/128612391

- 46. Abdul‐Mutakabbir J, Casey S, Jews V, et al. The utility of community‐academic partnerships in promoting the equitable delivery of COVID‐19 vaccines in Black communities. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8(suppl 1):S339. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Abdul‐Mutakabbir J. A multifaceted approach to provide the equitable delivery of COVID‐19 vaccines in the Black community. The European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 31st Annual Conference;2021 July 9‐12; Wien, Austria. 10.1016/j.lana.2022.100263. [DOI]

- 48. Khawaja N. Pharmacist helps people of color get access to COVID tests. Spectrum News. Charter Communications. 2022 [cited 2022 Apr 7]. Available from: https://spectrumlocalnews.com/nc/charlotte/news/2022/01/27/pharmacist‐is‐helping‐black‐and‐latino‐communities‐get‐access‐to‐covid‐19‐rapid‐tests‐and‐the‐vaccine

- 49. Don't miss your shot COVID‐19 mass vaccination event. Howard University College of Pharmacy. [cited 2021 Dec 17]. Available from: https://pharmacy.howard.edu/articles/dont‐miss‐your‐shot‐covid‐19‐mass‐vaccination‐event

- 50. Xavier University of Louisiana's College of Pharmacy research presented to President Biden's administration. Xavier University of Louisiana. 2021 [cited 2022 Apr 7]. Available from: https://www.xula.edu/news/2021/02/xavier‐university‐of‐louisianas‐college‐of‐pharmacy‐research‐presented‐to‐president‐bidens‐administration.html