1. INTRODUCTION

Olfactory dysfunction (OD) is one of the most common symptoms of acute and long COVID‐19. 1 , 2 Qualitative OD frequently accompanies or follows quantitative olfactory loss. 3 Few studies to date have combined both qualitative and quantitative evaluation of OD. 4 The aim of this study was to estimate the prevalence of qualitative OD and evaluate its functional impact in post–COVID‐19 patients by combining a validated questionnaire 5 and a comprehensive olfactory psychophysical evaluation.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

All patients referred to the Ear Nose and Throat outpatient clinic of the Trieste University Hospital for smell and taste disorders from February 2021 to June 2021 were screened. Inclusion criteria were: (1) age ≥18 years; (2) self‐reported OD occurring concurrently with COVID‐19 and persisting for at least 6 months; and (3) severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)‐CoV‐2 infection confirmed by reverse transcript‐polymerase chain reaction. Exclusion criteria were previous sinonasal surgery or neurologic/psychiatric disorders. Demographic and clinical data were collected through standardized questions. Self‐reported OD was evaluated using the 22‐item Sino‐Nasal Outcome Test (SNOT‐22) item “sense of smell or taste,” as described elsewhere. 6 Patients were asked, “Do you smell odors differently compared with previous experiences?” and “Do you smell odors in the absence of an apparent source?” at any time since SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and at the point of evaluation to identify parosmia and phantosmia, with answers reported as a binary outcome of yes or no. The timing of onset was self‐reported.

The presence of qualitative OD was also investigated through a structured questionnaire consisting of 4 questions, as described by Landis et al. 7 Using this instrument, each question is scored 1 to 4, summed, and then converted to a percentage, termed Score A, according to the formula: [(Sum − 4) / 12] × 100). A score of <100% indicates the presence of at least one symptom of qualitative OD. Based on Score A, 3 scoring categories were described: low (< 50%), indicating more severe qualitative OD; medium (50%‐84%); and high (≥85%), indicating less severe or absent (100%) qualitative dysfunction. Patients also completed a second set of 4 questions focusing on the functional impact of the olfactory distortion, reporting changed eating behavior, weight loss, avoidance of public places (each answered yes or no), and how many odors elicited the parosmia (almost every odor vs selected odors only) (see supplementary material for further details).

Orthonasal and retronasal olfactory function were measured using the extended Sniffin′ Sticks test (Burghart, Holms, Germany) and 20 powdered tasteless aromas (Givaudan Schweiz, Dubendorf, Switzerland), respectively, as described elsewhere 8 (see supplementary material for further details).

2.1. Statistics

Categorical and continuous variables are reported as percentage and median (interquartile range [IQR]) values, respectively. Differences in percentages and medians were evaluated through the Fisher exact test and Kruskal‐Wallis test. Correlations between scores were evaluated using the Spearman correlation coefficient.

3. RESULTS

Of the 183 patients screened, 105 met the inclusion criteria. Seven patients were excluded due to an incomplete evaluation, leaving 98 participants. Patients were evaluated at a median of 389 days (IQR, 343‐405) from the onset of self‐reported olfactory loss. On psychophysical testing, 15 (15.3%) patients were anosmic, 56 (57.1%) hyposmic, and 27 (27.6%) normosmic (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of 98 patients with COVID‐9–related long‐term olfactory dysfunction

| Characteristics | n | Prevalence (95% CI a ), % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Men | 30 | 30.6 (21.7‐40.7) | ||

| Women | 68 | 69.4 (59.3‐78.3) | ||

| Age, years | ||||

| <40 | 33 | 33.7 (24.4‐43.9) | ||

| 40‐49 | 23 | 23.5 (15.5‐33.1) | ||

| ≥50 | 42 | 42.9 (32.9‐53.3) | ||

| Tobacco smoking | ||||

| Never | 73 | 74.5 (64.7‐82.8) | ||

| Ever | 25 | 25.5 (17.2‐35.3) | ||

| Comorbidity b | ||||

| No | 65 | 66.3 (56.1‐75.6) | ||

| Yes | 33 | 33.7 (24.4‐43.9) | ||

| BMI | ||||

| <18.5 | 3 | 3.1 (0.6‐8.7) | ||

| 18.5‐24.9 | 53 | 54.1 (43.7‐64.2) | ||

| 25‐29.9 | 24 | 24.5 (16.4‐34.2) | ||

| ≥30 | 18 | 18.4 (11.3‐27.5) | ||

| Self‐reported smell or taste impairment (SNOT‐22 item) | ||||

| 1 = Very mild | 30 | 30.6 (21.7‐40.7) | ||

| 2 = Mild or slight | 10 | 10.2 (5.0‐18.0) | ||

| 3 = Moderate | 12 | 12.2 (6.5‐20.4) | ||

| 4 = Severe | 14 | 14.3 (8.0‐22.8) | ||

| 5 = As bad as it can be | 32 | 32.7 (23.5‐42.9) | ||

| Self‐reported qualitative OD at any time | ||||

| Parosmia or phantosmia | 53 | 54.1 (43.7‐64.2) | ||

| Parosmia | 38 | 38.8 (29.1‐49.2) | ||

| Phantosmia | 32 | 32.7 (23.5‐42.9) | ||

| Self‐reported qualitative OD at time of psychophysical evaluation | ||||

| Parosmia or phantosmia | 35 | 35.7 (26.3‐46.0) | ||

| Parosmia | 29 | 29.6 (20.8‐39.7) | ||

| Phantosmia | 20 | 20.4 (12.9‐29.7) | ||

| Presence of qualitative OD based on structured questionnaire score <100% | ||||

| Score A < 100% | 82 | 83.7 (74.8‐90.4) | ||

| Score A categories at time of psychophysical evaluation | ||||

| <50% (low) | 23 | 23.5 (15.5‐33.1) | ||

| 50%‐84% (medium) | 56 | 57.1 (46.7‐67.1) | ||

| ≥85% (high) | 19 | 19.4 (12.1‐28.6) | ||

| TDI categories | ||||

| ≤16.0 | 15 | 15.3 (8.8‐24.0) | ||

| 16.25‐30.50 | 56 | 57.1 (46.8‐67.1) | ||

| ≥30.75 | 27 | 27.6 (19.0‐37.5) | ||

| Score A | p Value c | |||

| <50% | 50%‐84% | ≥85% | ||

| Orthonasal evaluation | ||||

| Threshold (range, 1‐16) | 4 (2‐8) | 5 (2‐8) | 4 (2‐8) | p = 0.9731 |

| Discriminant (range, 0‐16) | 9 (9‐12) | 10 (7‐11) | 11 (9‐12) | p = 0.3723 |

| Identification (range, 0‐16) | 10 (9‐12) | 10 (7‐13) | 12 (10‐13) | p = 0.1810 |

| TDI (range, 1‐48) | 26 (20‐30) | 25 (17‐34) | 27 (23‐31) | p = 0.5778 |

| Retronasal identification score (range, 0‐20) | 15 (10‐17) | 15 (9‐17) | 17 (15‐19) | p = 0.0385 |

Abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; COVID‐19 = coronavirus disease‐2019; OD = olfactory dysfunction; SNOT‐22 = 22‐item Sino‐Nasal Outcome Test; TDI = threshold, discrimination, identification.

95% confidence intervals were calculated using Clopper‐Pearson method.

Comorbidity includes obesity (BMI, ≥30), diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, chronic respiratory disease, active cancer, renal disease, and liver disease.

Kruskal‐Wallis test.

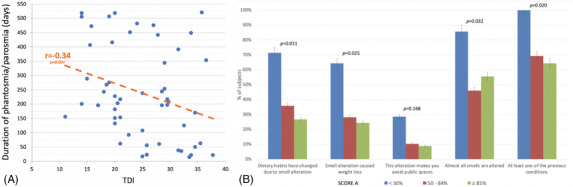

Fifty‐three (54.1%) and 35 patients (35.7%) self‐reported qualitative OD at any time and at the time of psychophysical evaluation, respectively. Parosmia and phantosmia arose at a median interval of 27 (range, 0‐297) days and 50 (range, 0‐271) days, respectively, from the quantitative OD onset. No differences in median threshold, discrimination, identification (TDI) scores were observed between patients who never complained of qualitative OD, those who recovered, and those who still complained of qualitative OD (p = 0.335). Among patients reporting parosmia or phantosmia at any time, more severe quantitatively measured OD was correlated with longer qualitative OD (r = −0.34, p < 0.001; Fig. 1A). In particular, the median for qualitative OD duration was 406 days in anosmic, 217 days in hyposmic, and 62 days in normosmic participants (p = 0.030).

FIGURE 1.

(A) Correlation between duration of phantosmia and/or parosmia and TDI in all patients who self‐reported qualitative olfactory dysfunction. (B) Functional impact of parosmia in 98 COVID‐19 patients as demonstrated by percentage of subjects assigned to each item by Score A category. TDI = threshold, discrimination, identification.

Based on the structured questionnaire, 82 patients (83.7%) reported at least 1 symptom of qualitative OD (Table 1). Scores were not significantly affected by sex or age. The presence of at least 1 symptom of qualitative OD was observed in 100%, 82.1%, and 77.8% of anosmic, hyposmic, and normosmic patients, respectively (p = 0.149). A significantly (p = 0.0385) lower retronasal identification score was observed in subjects with Score A <50%, whereas no differences were found for the orthonasal identification subtest (Table 1). A Score A of <50% was significantly associated with an increased functional impact compared with a Score A of ≥85%, including changes in dietary habits and weight loss (Fig. 1B).

4. DISCUSSION

The focus on quantitative loss in the early stages of the pandemic and the increasing dependence on psychophysical testing may lead to neglect of qualitative OD. In the present series, the prevalence of qualitative OD when assessed with a structured questionnaire was higher than the prevalence of quantitative OD, with 78% of patients classified as normosmic reporting qualitative OD. This is perhaps higher than expected and suggests that the questionnaire is highly sensitive, but also suggests that studies based on TDI tests alone may underestimate the true prevalence of OD. 5

We observed that patients with a Score A of <85% had a significantly lower retronasal identification score and a tendency for a lower orthonasal identification score than those reporting less severe qualitative dysfunction. This suggests that a distortion in the perception of odors can compromise identification skills more than discrimination and threshold and that Score A is a more sensitive assessment of qualitative OD. Parosmia and phantosmia arose at a median interval of 27 and 50 days from the onset of the quantitative OD. Patients were evaluated with a median follow‐up of >12 months, at which point only one third of patients who developed parosmia had recovered. This is consistent with findings by Reden et al, who evaluated a cohort of patients with mixed underlying etiologies for their OD, with 29% reporting improvement in parosmia after a period of 12 months. 6 The authors identified a strong association between the severity of parosmia and its functional impact. Specifically, patients with more severe qualitative OD reported having changed their dietary habits, which resulted in weight loss. These observations highlight the importance of carefully assessing subjects with post–COVID‐19 OD. 9

Our study has some limitations. A psychophysical assessment at baseline was not conducted, and therefore it was not possible to estimate the prognostic value of the qualitative alterations on olfactory loss recovery rate. Limitations in statistical power may be responsible for the lack of an association between TDI, orthonasal identification score, and Score A. Furthermore, the inclusion of patients with ongoing parosmia may have introduced information bias in the correlation between duration of parosmia and TDI. However, this potential bias is unlikely because median TDI was similar between patients who did and did not recover. Dietary changes and weight loss were self‐reported; a more objective assessment of these important aspects would be desirable. Recall bias may limit reliability regarding the onset of qualitative OD. Finally, there is selection bias in recruiting only patients referred to outpatients with OD for >6 months. There may be lower rates of parosmia in subjects with earlier recovery or in patients with mild OD who were not referred.

5. CONCLUSION

COVID‐19–related qualitative OD is a frequent finding, even in subjects with normal olfactory function on psychophysical tests. Structured questionnaires, specific to qualitative OD, should be routinely used as TDI tests alone can underestimate the prevalence of persistent COVID‐19–related OD. Patients with distorted perception of odors showed lower retronasal identification abilities. Qualitative OD can affect dietary habits and lead to weight loss.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Concept and design were provided by P.B.‐R. and G.T. All authors participated in acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data in addition to providing critical revision and intellectual content. Drafting of the manuscript was done by P.B.‐R. and L.A.V. Statistical analysis was performed by P.B.‐R. The study was supervised by P.B.‐R., C.H., L.A.V., and G.T. P.B.‐R. and G.T. had full access to all study data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Friuli Venezia Giulia Region (CEUR‐OS156).

Supporting information

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Professor Dr Thomas Hummel for critical review of the manuscript and his valuable comments. We also thank Dr Jerry Polesel for statistical consulting help. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not‐for‐profit sectors.

Boscolo‐Rizzo P, Hopkins C, Menini A, et al. Parosmia assessment with structured questions and its functional impact in patients with long‐term COVID‐19–related olfactory dysfunction. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2022;1‐5. 10.1002/alr.23054

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- 1. Vaira LA, Deiana G, Fois AG, et al. Objective evaluation of anosmia and ageusia in COVID‐19 patients: single‐center experience on 72 cases. Head Neck. 2020;42:1252‐1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boscolo‐Rizzo P, Guida F, Polesel J, et al. Sequelae in adults at 12 months after mild‐to‐moderate coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 9, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Walker A, Kelly C, Pottinger G, et al. Parosmia‐a common consequence of covid‐19. BMJ. 2022;377:e069860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Parker JK, Kelly CE, Gane SB. Insights into the molecular triggers of parosmia based on gas chromatography olfactometry. Commun Med. 2022;2:1‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Liu DT, Welge‐Lussen A, Besser G, Mueller CA, Renner B. Assessment of odor hedonic perception: the Sniffin'sticks parosmia test (SSParoT). Sci Rep. 2020;22:18019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Reden J, Maroldt H, Fritz A, et al. A study on the prognostic significance of qualitative olfactory dysfunction. Head Neck Surg. 2007;264:139‐144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Landis BN, Frasnelli J, Croy I, et al. Evaluating the clinical usefulness of structured questions in parosmia assessment. Laryngoscope. 2010;120:1707‐1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Boscolo‐Rizzo P, Hummel T, Hopkins C, et al. High prevalence of long‐term olfactory, gustatory, and chemesthesis dysfunction in post‐COVID‐19 patients: a matched case‐control study with one‐year follow‐up using a comprehensive psychophysical evaluation. Rhinology. 2021;59:517‐527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vaira LA, Gessa C, Deiana G, et al. The effects of persistent olfactory and gustatory dysfunctions on quality of life in long‐COVID‐19 patients. Life. 2022;12:141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.