SUMMARY

SARS‐CoV‐2, the virus that causes coronavirus disease (COVID)‐19, has become a persistent global health threat. Individuals who are symptomatic for COVID‐19 frequently exhibit respiratory illness, which is often accompanied by neurological symptoms of anosmia and fatigue. Mounting clinical data also indicate that many COVID‐19 patients display long‐term neurological disorders postinfection such as cognitive decline, which emphasizes the need to further elucidate the effects of COVID‐19 on the central nervous system. In this review article, we summarize an emerging body of literature describing the impact of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection on central nervous system (CNS) health and highlight important areas of future investigation.

Keywords: anosmia, COVID‐19, NeuroCOVID, neuroinflammation, neuroimmunology, olfactory system, SARS‐CoV‐2

1. INTRODUCTION

SARS‐CoV‐2, the virus responsible for the coronavirus disease (COVID)‐19 pandemic, poses a constant threat to global human health. Since its first detection in Wuhan, China in 2019, 1 approximately 500 million documented cases of COVID‐19 have been reported around the globe. The explosive spread of SARS‐CoV‐2 and the failure to contain the virus through isolation policies can be owed to SARS‐CoV‐2’s efficient airborne transmissibility and its ability to replicate in hosts without generating symptoms. For the majority of COVID‐19 cases today, the infected individual is either asymptomatic or experiences mild symptoms consisting of anosmia (loss of smell), fever, fatigue, headache, cough, muscle aches, and loss of appetite. 2 , 3 However, for certain vulnerable populations, SARS‐CoV‐2 infection can spiral into a severe disease that is accompanied by an acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). If left untreated, severe COVID‐19 can be deadly, and predictive models estimate that SARS‐CoV‐2 infection is implicated in 18.2 million deaths worldwide. 4

Although SARS‐CoV‐2 is often described as a respiratory virus, COVID‐19 is best described as a multifaceted inflammatory syndrome. SARS‐CoV‐2 and its sarbecoronavirus relatives are notorious for instigating uncontrolled inflammation in their host, commonly referred to as “cytokine storms.” The structural and accessory proteins of SARS‐CoV‐2 are potent stimulators of the host’s innate immune system, 5 and this overstimulation can lead to chronic inflammation in a variety of organs including the brain. At present, there is mounting evidence that severe COVID‐19 can damage the central nervous system (neuro‐COVID), which is congruent with the growing public concern that survivors of severe COVID‐19 have an increased risk of developing neurological disorders. Following infection, many COVID‐19 patients describe experiencing “brain‐fog.” Emerging clinical data indicate that COVID‐19 survivors display postacute [neurological] sequalae of COVID‐19 (neuro‐PASC) such as prolonged anosmia, depression, memory loss, and cognitive decline. 6

There is currently a substantial gap in our knowledge of how COVID‐19 damages the central nervous system (CNS). It is unclear whether the SARS‐CoV‐2 virus itself is directly causing damage in the CNS or whether the host’s immune response to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection is inadvertently causing damage in the CNS through inflammatory processes. Therefore, this review will highlight several recent studies that have attempted to elucidate the acute and long‐term effects of COVID‐19 on the CNS.

2. BACKGROUND

2.1. The emergence and evolution of SARS‐CoV‐2

Due to their high zoonotic potential, coronaviruses frequently overcome species barriers through natural selection in the animal host and sporadically spillover into the global human population. The seven coronaviruses known to infect humans are all within the alpha‐coronavirus and beta‐coronavirus genera. 7 Viruses belonging to the Sarbecoronavirus (e.g., SARS‐CoV and SARS‐CoV‐2) or Merbecoronavirus (e.g., MERS‐CoV) subgenera can cause severe disease in humans, while seasonal viruses in the Embecoronavirus (e.g., HCoV‐OC43 and HCoV‐HKU1), Duvinacoronavirus (e.g., HCoV‐229E), and Setracoronavirus (e.g., HCoV‐NL63) subgenera often cause mild “common cold” symptoms in humans. 7 , 8 Five of the seven human‐infecting coronaviruses are hypothesized to be bat‐derived, and the transmission of these bat coronaviruses to humans seems to be dependent on an intermediate host (e.g., bovine, camels, camelids, and civets). 9 Asian horseshoe bats harbor the vast majority of known sarbecoronaviruses, but sarbecoronavirus‐infected horseshoe bats have also been detected in Slovenia 10 and Kenya. 11 Sarbecoronaviruses are all derived from a common ancestor that utilizes the mammalian angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor for entry into host cells. 12 , 13 , 14 Today, SARS‐like virus clades in Asia and the BtKY72 virus in Kenya utilize ACE2, while a new HKU3‐related sarbecoronavirus clade has become independent of ACE2. 14 The severe disease associated with sarbecoronavirus infections in humans does not seem to be related to the exploitation of the ACE2 receptor because the mild HCoV‐NL63 alphacoronavirus also binds ACE2. 15 , 16

The emergence of a highly transmissible sarbecoronavirus with pandemic‐potential was not unexpected but anticipated for years. SARS‐like sarbecoronaviruses gained the ability to bind to the ACE2 receptors of two potential intermediate hosts, civets, and rodents 14 , 17 , 18 , 19 ; both of which were actively traded in Wuhan wet markets. 20 Moreover, between 2013 and 2019, a crescendo of metadata collected by the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV) and Dr. Ralph S. Baric and colleagues contended that Asian horseshoe bat‐derived SARS‐like viruses 21 , 22 were already capable of efficiently binding and infecting through the human ACE2 receptor. 18 , 23 , 24 , 25 SARS seropositivity surveillance by WIV in 2018 hints that a SARS‐like virus may already have been circulating in villages adjacent to bat‐populated caves in the Yunnan province in China, 26 suggesting a regular human exposure to a possible precursor to SARS‐CoV‐2. 27

SARS‐CoV‐2 likely emerged through either bat‐to‐human transmission or bat‐to‐pangolin‐to‐human transmission. 7 The RaTG13 and RpYN06 SARS‐like viruses isolated from Chinese horseshoe bats have, respectively, 96.2% and 94.5% nucleotide sequence homology to ancestral SARS‐CoV‐2, but their ACE2 receptor‐binding residues are vastly different from SARS‐CoV‐2. 1 , 8 , 28 On the contrary, although pangolin‐derived SARS‐like sarbecoronaviruses isolated in the Guandong province of China have only 85.5% to 92.4% nucleotide sequence similarity to ancestral SARS‐CoV‐2, their receptor‐binding domain sequence and structure is nearly identical to ancestral SARS‐CoV‐2 29 , 30 and can engage human ACE2 with a higher affinity than ancestral SARS‐CoV‐2. 31 The residues on human ACE2 that are contacted by SARS‐CoV‐2 are quite different from pangolin ACE2, 14 suggesting that the similarity of receptor‐binding domains of pangolin‐derived SARS‐like viruses and SARS‐CoV‐2 is not the result of ACE2‐driven natural selection but the divergence from a common ancestor.

While the discovery of new bat‐derived and pangolin‐derived sarbecoronaviruses has partially filled the gaps in our knowledge of how a SARS‐like virus evolved into SARS‐CoV‐2, the de novo addition of a polybasic site (RRRAR, also referred to as S1/S2) into the SARS‐CoV‐2 spike protein is peculiar. 8 The presence of a polybasic cleavage site on the virus protein that interacts with the host receptor is the rate‐limiting step for whether or not a coronavirus (e.g., MERS‐CoV, HCoV‐HKU1, and HCoV‐OC43) or influenza virus becomes highly transmissible. 7 , 8 , 32 Two mutations surrounding this polybasic pocket are blamed for the enhanced transmissibility of the SARS‐CoV‐2 Omicron variant compared to previous variants of concern. 33 Without this polybasic site, SARS‐CoV‐2 is unable to spread airborne and its disease is attenuated in animal models. 34 , 35 Such a polybasic site has never been detected in pangolin‐derived sarbecoronaviruses thus far, which may explain why pangolin‐derived sarbecoronaviruses fail to be transmitted through aerosol and replicate efficiently in other mammalian hosts. 36 Therefore, the natural acquisition of SARS‐CoV‐2’s polybasic site remains a mystery, and the lack of data on SARS‐like sarbecoronavirus carrying this polybasic site leaves room for conspiracies of SARS‐CoV‐2 being initially created in a laboratory setting. 7 , 27

The mutation‐dependent evolutionary plasticity of SARS‐like sarbecoronaviruses binding ACE2 orthologs is remarkable, which explains the high zoonotic capabilities of these viruses. 14 When ancestral SARS‐CoV‐2 first emerged, it could efficiently bind and infect through the ACE2 receptor of non‐human primates, 37 , 38 bats, 39 , 40 mink, 41 , 42 ferrets, 40 , 43 , 44 deer mice, 45 , 46 felines, 47 , 48 canines, 49 , 50 , 51 rabbits, 52 hamsters, 53 , 54 and white‐tailed deer 55 , 56 , 57 (Figure 1). As SARS‐CoV‐2 continues to spread in mammalian populations around the world, the virus has gained mutations in its receptor‐binding domain that have augmented its transmissibility and improved its pan‐ACE2‐binding, while expanding the range of species that it can infect. For example, in 2020, deep mutational scanning of the SARS‐CoV‐2 receptor‐binding domain identified the N501 residue as a constraint for increased pan‐ACE2‐binding affinity. 58 Soon after, the circulating SARS‐CoV‐2 virus naturally gained the N501Y mutation; and its aerosol transmission, human ACE2‐binding affinity, and ability to infect mice and rats was drastically improved 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The expanding species tropism of SARS‐CoV‐2. SARS‐CoV‐2 is derived from zoonotic SARS‐like sarbecoronaviruses which already have the capacity to infect hamsters and human cells. Ancestral SARS‐CoV‐2 gained the furin cleavage site while replicating in an unknown host. Ancestral SARS‐CoV‐2 could infect a variety of species and SARS‐CoV‐2 variants continue to circulate in wild deer and mink. The N501Y mutation on the spike protein expanded the tropism of SARS‐CoV‐2 to mice and rats. Subsequent spike mutations have likely expanded SARS‐CoV‐2 tropism to more species. Figure created in Biorender

SARS‐CoV‐2 variants of concern, such as Delta and Epsilon, have demonstrated that the virus has mutation flexibility to escape from neutralizing antibodies while also enhance transmissibility and infectivity across multiple species. 66 (p202), 60 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 However, due to selective pressures, it seems that the current dominant SARS‐CoV‐2 strain (Omicron variant) sacrificed its replication fitness to evade naturally occurring neutralizing antibodies. 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 Despite its enhanced transmissibility and ACE2 binding affinity, 75 the SARS‐CoV‐2 Omicron variant has attenuated fitness across a variety of human cell lines and animals. 78 , 79 , 80 This loss of fitness by the SARS‐CoV‐2 omicron variant, reported herein as “Omicron,” is due to multiple unfavorable mutations surrounding its spike S2’ site. 80 This is a bizarre strategy by Omicron because efficient cleavage of the S2’ site is crucial for the infectivity of ancestral SARS‐CoV‐2 and the alpha, beta, gamma, and delta variants that preceded Omicron, reported herein as SARS‐CoV‐2(A‐D). Despite these drastic actions by Omicron to evade immune detection through antigenic shifts, a handful of broad‐spectrum neutralizing antibodies and plasma from convalescent and vaccinated individuals can still neutralize Omicron. 71 , 72 , 75

As history has shown us, all previous SARS‐CoV‐2 variants of concern arose to dominance through virus lineages that were separate from the prevailing lineage at the time. 81 Therefore, although the current dominant variant of SARS‐CoV‐2 has impaired fitness and possibly elicits a less severe disease, we should expect future variants of SARS‐CoV‐2 to have unpredictable severity and immune evasion capabilities. 81

2.2. The structure and life cycle of SARS‐CoV‐2

SARS‐CoV‐2 is a positive‐sense RNA, enveloped virus that is studded with glycoproteins called spikes that enable the virus to infect cells through engagement of the mammalian host’s angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor. 82 Recent studies suggest that cellular senescence increases the transcription of ACE2 83 , 84 — a critical predilection that may account for severe COVID‐19 disproportionately affecting older populations. Unlike SARS‐CoV, SARS‐CoV‐2 displays an important polybasic site on the junction of two spike glycoprotein subunits (S1/S2). 85 , 86 , 87 Before a newly made SARS‐CoV‐2 virion undergoes exocytosis from an infected host cell, the mammalian protein furin, a calcium‐dependent serine protease on the Golgi apparatus, precleaves this polybasic site. 85 , 86 , 87 , 88 Furin precleavage of the S1/S2 site reduces the need for SARS‐CoV‐2 to search for proteases on target cells to prime its spike protein for ACE2 attachment 89 (Figure 2B). Once a SARS‐CoV‐2 virion encounters a host cell membrane, co‐factors such as heparan sulfate 90 , 91 and sialic acid, 92 , 93 which are also utilized by herpesviruses, 94 influenza viruses, 95 and other coronaviruses, 96 , 97 aid in viral attachment to ACE2 (Figure 2B). On the surface of the target cell membrane, SARS‐CoV‐2(A‐D) relies upon transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2) on the target cell to cleave the S2’ site of its spike 98 —a strategy also employed by SARS‐CoV 35 , 82 and Influenza A. 99 The co‐expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 makes host cells frequent targets of SARS‐CoV‐2(A‐D) infection, particularly Type II pneumocytes in the alveolar epithelium, multiciliated cells in the nasal respiratory epithelium, and sustentacular cells in the olfactory neuroepithelium. 100 , 101 , 102 If the S1/S2 site of the SARS‐CoV‐2 spike was not precleaved by furin, thereby blocking downstream TMPRSS2 cleavage of the S2’ site, host cathepsins can cut at sites between S1/S2 and S2’ as an alternative to priming the S2 subunit for ACE2 fusion 35 , 88 , 103 , 104 , 105 , 106 (Figure 2A).

FIGURE 2.

The S1/S2 Site and S2’ Site on the SARS‐CoV‐2 Spike Determines the Route of Infection. (A) The SARS‐CoV‐2 spike uses furin or cathepsin B to proteolytically cleave its S1/S2 site and uses TMPRSS2 or cathepsin L to further prime the S2 subunit near the S2’ site. The SARS‐CoV spike solely relies on Cathepsin B for cleavage of its S1/S2 site and is more dependent on Cathepsin L for cleavage of its S2’ site. The SARS‐CoV‐2 Delta variant gained mutations that increased the efficiency of TMPRSS2 cleavage of the S2’ site. Omicron became more reliant on cathepsin L for priming the S2 subunit and acquired 2 mutations upstream of S1/S2 that increase the efficiency of furin cleavage. (B) Ancestral SARS‐CoV‐2 spike is usually cleaved by TMPRSS2 on the plasma membrane, which leads to ACE2‐mediated binding and fusion of the virus membrane with the cell host membrane. Instead of fusing with the membrane, Omicron relies on cathepsin L to prime its S2 subunit before ACE2‐mediated fusion with the endosomal membrane. Figure created in Biorender

To enter a host cell, the receptor‐binding domain of the SARS‐CoV‐2 spike protein binds with ACE2 on the membrane 87 , 107 (Figure 2B). Immediately, the virus either directly fuses with the cell membrane or the virus‐ACE2 complex is endocytosed into the host cell through a β3‐integrin‐dependent process. 108 , 109 Within endosomes, SARS‐CoV‐2 spike proteins, that were not cleaved by TMPRSS2 on the cell membrane, are cleaved by cathepsin L—the primary priming mechanism of pangolin sarbecoronavirus spikes. 103 Although the purpose of these spike cleavage events has not been fully appreciated, recent data suggest that spike cleavage is crucial for evading detection by interferon‐induced transmembrane proteins (IFITM1, IFITM2, and IFITM3) so that the virus can properly fuse with the endosomal membrane. 35 , 108

Although furin‐mediated and TMPRSS2‐mediated cleavage of SARS‐CoV‐2’s spike protein before ACE2‐engagement is a canonical mechanism for SARS‐CoV‐2(A‐D), mounting evidence suggests that SARS‐CoV‐2 might be able to infect lung cells that do not express ACE2. 91 In addition, SARS‐CoV‐2 can exploit the Neuropillin‐1 receptor, 110 , 111 exploit the high‐density lipoprotein scavenger type B receptor, 112 and coat itself in soluble ACE2 and Vasopressin 113 to gain access into cells, but these virus strategies remain to be further investigated. Cryo‐electron microscopy has revealed that the spike protein on Omicron is more compact and stable than SARS‐CoV‐2(A‐D) which is probably a conformational masking strategy to protect the interior receptor‐binding domain from neutralizing antibodies. 75 , 114 As Omicron has mutations surrounding its S2’ site, TMPRSS2‐mediated cleavage of the spike protein is inefficient, and ACE2‐mediated virus entry is markedly decreased in human cells. 80 , 115 The trade‐off is that Omicron is less dependent on TMPRSS2 processing of its spike protein before ACE2 receptor engagement, but now more dependent on cathepsin cleavage of its spike protein and clatherin‐mediated endocytosis for infection. 104 Therefore, Omicron seems to have reverted to its old self and is now more reliant on spike cleavage strategies employed by pangolin sarbecoronaviruses. 103

Once SARS‐CoV‐2 gains access to the cytoplasm of host cells, the release of its large RNA genome into the aqueous space triggers the initiation of a complex program of virus RNA translation. 8 SARS‐CoV‐2 recruits host ribosomes to its 5’ end to translate two open reading frames (ORF), ORF1a and ribosomal‐frameshift‐dependent ORF1b, which constitute most of the genome. 8 The products of translating these ORFs are two long amino acid sequences called pp1a and pp1ab. 116 These two amino acid sequences are then proteolytically cleaved by the virus’ main protease (Mpro) on pp1a, which yields 16 mature non‐structural proteins. 8 Many of these effector proteins will go on to disrupt the splicing, translation, and protein trafficking of the host cell to prevent an antiviral Type I Interferon (IFN‐I) response. 117 , 118 , 119 Meanwhile, the RNA polymerase holozyme, that is formed by RdRp, nsp7, and nsp8, initiates RNA replication in double‐membrane vesicles derived from the endoplasmic reticulum. 89 , 116 The incoming newly synthesized negative‐sense RNA will serve as a template for positive‐sense genomic RNA and complementary positive‐sense subgenomic RNAs. 8 , 89 , 120 The translation of the subgenomic RNAs generates structural (e.g., Spike) and accessory proteins (e.g., ORF3a). 120 These proteins along with nucleocapsid‐enriched positive‐sense genomic RNA are inserted into the ER‐Golgi intermediate compartment to support the assembly and budding of an enveloped SARS‐CoV‐2 virus. 8 , 89 Before lysosomal trafficking and exocytosis of the new virions occurs, 121 the spike protein is precleaved by furin on the Golgi apparatus to prime the virus’ spike for ACE2‐binding. 85 , 86 , 87 Although most virions spread from infected cells through exocytosis, furin‐mediated cleavage of the spike protein also allows SARS‐CoV‐2(A‐D) to fuse infected cells with neighboring host cells to form a multinucleated cell, also known as syncytia. 35 , 122 This was a common dissemination strategy used by SARS‐CoV‐2(A‐D) in the lungs. However, since TMPRSS2 is required for syncytia formation sites, 123 cell‐cell fusion and virus spread by TMPRSS2‐independent Omicron is severely impaired. 115 Therefore, the loss of syncytia induction is another important factor that contributes to the attenuated fitness of Omicron.

2.3. The immune response to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in the lungs

The detailed analyses of nasal lavage fluid, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, and blood samples from innumerable COVID‐19 patients has provided scientists and clinicians with a comprehensive model of the pathogenesis of COVID‐19. Although our model of COVID‐19 is constantly being refined, our fundamental understanding is that aberrant immune signaling in severe COVID‐19 is precipitated by a delay in conventional antiviral responses.

At the beginning of infection, as SARS‐CoV‐2 spreads in the upper and lower respiratory tracts, innate immune sensors (PRRs) on a variety of host cells detect the pathogen‐associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) of SARS‐CoV‐2, triggering robust cytokine production. For instance: the SARS‐CoV‐2 spike protein is sensed by Toll‐Like Receptor 4 (TLR4), 124 , 125 the envelope protein is sensed by TLR2, 126 the nucleocapsid protein is sensed by the NLRP3 inflammasome, 127 and viral RNA is sensed by retinoic acid‐inducible gene‐1 (RIG‐I) 128 and TLR7/8. 129 , 130 Moreover, SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and syncytia of human lung pneumocytes and endothelial cells causes mitochondrial DNA release which stimulates the intracellular cGAS‐STING pathway. 131 , 132 , 133 The stimulation of these PRRs in the lungs sets in motion a cascade of NF‐κB‐dependent signaling that leads to the potent and chronic release of pro‐inflammatory cytokines, including TNFα, IL‐1α, IL‐1β, IL‐6, and IL‐8—all of which are consistently elevated in the blood of hospitalized COVID‐19 patients 134 , 135 , 136 and mice infected with mouse‐adapted SARS‐CoV‐2 (MA10, MA30). 137 , 138 Therefore, there is mounting evidence that the dramatic stimulation of PRRs, especially TLR2, NLRP3, and cGAS‐STING, early in infection is sufficient to drive COVID‐19 immunopathology in the lungs. The inhibition of these PRRs seems to prevent severe disease in SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected laboratory mice and hamsters, indicating that these PRRs are not necessary to mount a successful immune response against SARS‐CoV‐2.

While cellular senescence in the lungs is a common consequence of SARS‐CoV‐2‐induced hyperinflammation, 139 , 140 preexisting cellular senescence is a risk factor for COVID‐19. Besides the putative overexpression of SARS‐CoV‐2 entry factors in aged tissue, 83 , 84 senescent cells have arrested antiviral responses. 83 , 137 , 141 For instance, the overexpression of the lung senescence‐associated Phospholipase A2 Group 2D leads to dendritic cell impairment and poorer clinical outcomes in mice infected with mouse‐adapted SARS‐CoV (MA15) and SARS‐CoV‐2 (MA30). 137 , 141 Senescent cells also have a tendency toward a more pro‐inflammatory cytokine secretion state upon stimulation. Therefore, a positive‐feedback loop of SARS‐CoV‐2 virus‐induced cellular senescence in the lungs can further exacerbate hyperinflammation in aged individuals. 142 Senolytic drugs are now being pursued as promising candidates for globally suppressing aberrant cytokine production in COVID‐19.

It is generally believed that an early, antiviral type I IFN response promotes the clearance of the SARS‐CoV‐2 virus and attenuates SARS‐CoV‐2‐induced hyperinflammation. However, similar to SARS‐CoV and MERS‐CoV, SARS‐CoV‐2 uses a variety of effector proteins to antagonize type I IFN production 143 , 144 , 145 , 146 , 147 and suppress the induction of type I IFN‐stimulated genes. 148 Compared with orthologs from SARS‐CoV and bat‐derived SARS‐like sarbecoronaviruses, SARS‐CoV‐2 effector proteins have become better at suppressing type I IFN induction; the subgenomic RNA expression and efficiency of these effector proteins is increasing with every new variant. 145 , 149 , 150 Meanwhile, we can also be our own worst enemy—a common theme in severe COVID‐19. For instance, Dr. Jean‐Laurent Casanova and colleagues have demonstrated that patients possessing inborn errors in type I IFN‐related signaling or neutralizing autoantibodies against type I IFNs are highly susceptible to severe COVID‐19 pneumonia. 151 , 152 , 153 Moreover, individuals harboring autoantibodies against type I IFNs in the nasal mucosa also have higher SARS‐CoV‐2 viral loads, suggesting that these individuals have the capacity to become SARS‐CoV‐2 super spreaders. 154

Due to the complexity of COVID‐19, there is a fine line between type I IFN‐induced protection and type I IFN‐driven pathology. For instance, depending on the context, the overabundance of type I IFNs or cGAS‐STING activation can prevent or promote mortality in SARS‐CoV‐2(A‐D)‐infected wildtype mice and hamsters, complicating efforts for identifying antiviral therapies for COVID‐19. 131 , 155 , 156 , 157 Unaware of its future value, Dr. Stanley Perlman and colleagues in 2016 provided us with the best demonstration of type I IFN induction being a double‐edged sword during sarbecoronavirus disease. 158 In wildtype mice infected with hypervirulent SARS‐CoV MA15, the administration of type I IFNs 6 hours postinfection prevents mortality, while the administration of type I IFNs 24 hours postinfection leads to widespread mortality. 158 In contrast, mice deficient in the receptor for type I IFNs (IFNAR) were protected from MA15 mortality and had milder disease. 158 Therefore, the timing of an all‐or‐none type I IFN response appears to dictate the severity of sarbecoronavirus disease. 158

As previously described, senescent tissue carries a predilection toward dampened antiviral responses and hyperinflammation upon stimulation. Therefore, it is asserted that aged humans and animals mount a delayed type I IFN response against SARS‐CoV‐2 and that this subsequently sets the stage for an immune imbalance consisting of lymphopenia, monocytosis, and neutrophilia. 137 , 159 , 160 , 161 During late‐stage severe COVID‐19, proliferating neutrophils inundate the lungs and blood. 162 , 163 The vicious release of neutrophil extracellular traps in blood vessels further exacerbates disease by causing rapid thrombosis. 164 Meanwhile, inflammatory monocyte‐derived macrophages (IMMs) flood the lungs and congregate in areas of high virus burden. 137 , 165 , 166 Early data suggest that SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected IMMs and TNFα‐IFN‐γ‐stimulated IMMs undergo pyroptosis, a form of inflammatory cell death that is extremely deleterious for the lungs. 130 , 167 , 168 , 169

Ultimately, this complete dysregulation of the immune response allows SARS‐CoV‐2 to enter the blood—a critical moment because the circulating SARS‐CoV‐2 virus will then have direct access to a variety of organs including the brain. In addition, SARS‐CoV‐2‐induced hyperinflammation in the lungs drives prominent damage in the lungs, including diffuse alveolar damage, thrombosis, and cellular senescence of epithelial and endothelial cells. 139 All of these forms of cellular damage reduce the respiration capacity of the lungs which leads to a dangerous hypoxic state in a variety of organs, especially the brain. 170 , 171

3. SARS‐COV‐2 PREFERENTIALLY TARGETS NON‐NEURONAL CELLS

3.1. SARS‐CoV‐2 infects the olfactory neuroepithelium

The olfactory neuroepithelium is an intimate site where apical, ciliated, glia‐like sustentacular cells interact and communicate with basal bipolar olfactory sensory neurons. The exposed olfactory neuroepithelium that surrounds each ethmoid turbinate is lined with a thin mucus‐rich cilia layer that is sheltered by a dense canopy of olfactory sensory neuron dendrites that are covered in a variety of odorant receptors.

Once airborne infectious SARS‐CoV‐2 virions are inhaled, the SARS‐CoV‐2 virus attempts to infect cells along the nasal respiratory epithelium and olfactory neuroepithelium. 102 , 172 , 173 Sustentacular cells are especially vulnerable to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection because they display TMPRSS2 and ACE2 on their apical surface. 101 , 174 Electron microcopy of the SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected hamster neuroepithelium shows that sustentacular cells lose their cilia as SARS‐CoV‐2 fuses with the cell membrane. 175 Once SARS‐CoV‐2(A‐D) infects the columnar sustentacular cells, the virus gains access to a large portion of cytoplasm that extends into the basal lamina. 173 Upon lysis of the sustentacular cells, virus progeny from the SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected sustentacular cells will then bind to and infect neighboring cells that reside in the olfactory neuroepithelium.

SARS‐CoV‐2(A‐D) infection of sustentacular cells is observed across species, including humans, 172 , 173 , 175 humanized mice, 176 wildtype mice, 137 , 138 and hamsters. 172 , 175 Interestingly, not all sustentacular cells are ACE2‐expressing in mice—ACE2 is only localized to the apical surface of sustentacular cells residing in the NAD(P)H Quinone Dehydrogenase‐rich dorsal ethmoid turbinates. 101 , 174 However, SARS‐CoV‐2(A‐D) infection is observed throughout the ethmoid turbinates of wildtype mice, implying that SARS‐CoV‐2(A‐D) can infect sustentacular cells through an ACE2‐independent pathway.

Olfactory sensory neurons do not express TMPRSS2 or ACE2. 101 , 174 Nevertheless, olfactory sensory neuron infection can occur on occasion. The frequency of olfactory sensory neuron infection seems to be age‐dependent and species‐dependent. SARS‐CoV‐2(A‐D) fails to infect olfactory sensory neurons in adult humans, 173 but SARS‐CoV‐2 readily infects the olfactory sensory neurons of young hamsters 172 , 177 and adult deer mice. 45 The overexpression of Neuropillin‐1, a secondary entry receptor for SARS‐CoV‐2, 110 , 111 in immature olfactory sensory neurons allows SARS‐CoV‐2 to travel along the olfactory nerve and invade the olfactory nerve layer of the olfactory bulb in young hamsters. 172 , 175 Neuropillin‐1 is expressed along the olfactory neuroepithelium of humans, 110 but it remains to be seen whether SARS‐CoV‐2 utilizes the Neuropillin‐1 receptor to infect human olfactory sensory neurons.

If the virus infection extends to the lower layer of the olfactory neuroepithelium, Bowman’s gland cells and horizontal basal cells might also become infected. Bowman’s gland cells, the main producers of mucin along the nasal epithelium, 178 express high levels of TMPRSS2 but low levels of ACE2. 101 , 174 SARS‐CoV‐2(WA1) and Omicron fail to infect the Bowman’s gland in Syrian hamsters, but SARS‐CoV‐2(Delta) gained the ability to infect Bowman’s gland cells. 172 The selective advantage of SARS‐CoV‐2(Delta) in the Bowman’s gland could be due to its improved binding affinity for ACE2 179 and its enhanced exploitation of TMPRSS2 for potentiating its spread among host cells. 80 , 180

Horizontal basal cells are the primary multipotent progenitors of the olfactory epithelium 181 and give rise to sustentacular cells, Bowman’s gland cells, microvillous cells, and globose basal cells which are the direct progenitors of olfactory sensory neurons. 182 Single‐cell RNA‐sequencing and immunofluorescence imaging of human biopsies confirmed that horizontal basal cells are TMPRSS2 and ACE2‐expressing, but it remains unclear whether SARS‐CoV‐2(A‐D) infects horizontal basal cells. 101 , 174

In 2020, a medical group in Germany released their initial evaluations of postmortem olfactory tissue from COVID‐19 patients and showed that, in some instances, SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA can be detected in the human olfactory bulb. 183 They concluded that SARS‐CoV‐2 is neurotropic and can travel along the olfactory nerve to infect the olfactory bulb, 183 as observed in HCoV‐OC43 184 and MHV‐JHM 185 betacoronavirus infections. Upon further exploration, SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA could also be detected in the olfactory bulbs of SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected African Green monkeys, 37 Rhesus monkeys, 186 and Syrian hamsters. 175 These reports conflicted with data showing that the mammalian olfactory bulb parenchyma was devoid of ACE2 and TMPRSS2. 101 , 174 However, the discovery of Neuropillin‐1 as a secondary receptor for SARS‐CoV‐2 renewed theories of neuronal anterograde transport of SARS‐CoV‐2 to the olfactory bulb. 110 , 111 To obtain definitive proof of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in the human olfactory bulb parenchyma, Khan and coworkers performed spatial transcriptomics on human olfactory bulbs to holistically detect SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA and pinpoint its location in the tissue. 173 On the contrary, they discovered that SARS‐CoV‐2 was only localized to blood vessels and the leptomeninges, and virus was not detected in the parenchyma. 173 The detection of SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA in the human olfactory bulb is most likely due to the virus remaining attached to endothelium. 146 In sum, SARS‐CoV‐2 efficiently infects the olfactory neuroepithelium but not the olfactory bulb of the olfactory system.

3.2. SARS‐CoV‐2 infects the cerebrovasculature and choroid plexus

Neurological complications and cognitive impairments arising during severe COVID‐19 have led to a great deal of speculation regarding the neurotropism and neuroinvasiveness of SARS‐CoV‐2 in the brain. When SARS‐CoV‐2 viremia occurs in severe COVID‐19, the circulating virus has access to a variety of organs including the brain. SARS‐CoV‐2(A‐D) is frequently detected in postmortem brains of older COVID‐19 patients. 170 , 183 , 187 As in humans, low levels of SARS‐CoV‐2(A‐D) can be detected on occasion in the brains of non‐human primates 37 , 186 and ferrets. 40 , 43 SARS‐CoV‐2(A‐D) RNA is plentiful in the brains of young hamsters 36 , 53 , 175 but has yet to be detected in the brains of infected standard laboratory adult mice 137 , 138 , 188 and adult hamsters. 53 Further research is needed to assess whether SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA can be detected in the brains of aged rodents to recapitulate human disease.

Despite the frequency of viral RNA detected in the human brain, SARS‐CoV‐2 is only localized to blood vessels and fails to invade the brain parenchyma, according to immunohistochemistry and spatial transcriptomics of human samples. 146 , 170 , 173 , 183 , 189 , 190 These observations are consistent with the localization of ACE2 and Neuropillin‐1 along blood vessels of mouse and human brains, but not the parenchyma, 101 , 146 , 174 implying that the requirements needed for efficient SARS‐CoV‐2 infection only exist at this site. However, pericytes are the vascular cell that highly express ACE2, 101 , 146 , 191 and they remain hidden from SARS‐CoV‐2 behind the tight blood‐brain barrier. Endothelial cells do not express ACE2 and have a low expression of Neuropillin‐1. 146 , 187 TMPRSS2 is also not detected along the cerebrovasculature.

Undeterred by these contradictions, Wenzel and coworkers brought forth direct evidence that SARS‐CoV‐2 infects brain endothelial cells and facilitates their death. 146 The main protease (Mpro) of SARS‐CoV‐2 cleaves endothelial cells’ nuclear factor (NF)‐kB essential modulator (NEMO), an essential protein for cell survival in an inflammatory environment. 146 , 192 While the inhibition of NEMO is part of a concerted effort by multiple SARS‐CoV‐2 proteins to prevent RIG‐I‐mediated NF‐kB induction, 193 , 194 the loss of NF‐κB has the unintended consequence of sensitizing cells for TNFα‐induced, RIPK1‐mediated cell death. 146 , 192 In the inflamed intestines, this loss of NF‐kB and subsequent cell apoptosis compromises barrier integrity, 192 and the same holds true with the blood‐brain barrier. 146 As a result, the SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected blood vessels collapse, forming empty basement membranes, known as string vessels, throughout the brains of SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected hamsters and COVID‐19 patients. 146 String vessel formation caused by NEMO inhibition instigates cortical astrogliosis. 146 Recently, Yang and coworkers showed that inflammatory astrocytes account for approximately 80% of the differentially expressed genes in the frontal cortex of COVID‐19 patients 189 —SARS‐CoV‐2‐induced string vessel formation is a likely contributor to this phenotype. To perturb SARS‐CoV‐2‐induced string vessels and possibly suppress thrombotic events and inflammatory astrocytes in the COVID‐19 brain, Pfizer’s FDA‐approved Mpro inhibitor, Paxlovid, is a promising preventative. 195

To identify the vulnerable cell types beyond the brain endothelium that SARS‐CoV‐2 has the capacity to infect, multiple laboratories have set out to create human cortical organoid models of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Despite their efforts, each laboratory’s conclusion contradicts the next, 196 , 197 , 198 and it is most likely that SARS‐CoV‐2 tropism is extremely low in cells residing in the parenchyma. 196 , 199 , 200 However, laboratories utilizing SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected brain organoids have reached agreement on the identity of one vulnerable cell population in the brain: choroid plexus epithelial cells. 196 , 199 , 201 This comes as no surprise because SARS‐CoV‐2 infects and replicates in a variety of epithelium.

The choroid plexus, a cerebrospinal fluid‐secreting tissue, could be an important site of SARS‐CoV‐2 dissemination in the central nervous system during severe COVID‐19. SARS‐CoV‐2 is occasionally observed within the capillaries of the human choroid plexus. 189 , 202 Human choroid plexus organoid models show that SARS‐CoV‐2 infects the choroid plexus epithelium, which leads to syncytia formation, the loss of homeostatic barrier integrity and ion transport, and the upregulation of signaling pathways involved in cell death and inflammatory cytokine production. 196 , 199 , 201 A subset of apolipoprotein‐producing mature choroid plexus cells express high levels of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and are especially vulnerable to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. 201 These apolipoprotein‐producing choroid plexus cells increase their expression of ACE2, APOJ (Clusterin), and APOE as the virus infects and damages the organoid epithelium. 201 Neurons and glia expressing APOE4 are especially vulnerable to SARS‐CoV‐2 in vitro, and this might also be the case with choroid plexus epithelial cells. 203 Although it is unclear how APOE is aiding in virus entry, a human‐SARS‐CoV‐2 protein interactome developed from HEK‐293T cells illuminated lipoprotein metabolic machinery as the primary target of SARS‐CoV‐2’s spike protein. 204 Moreover, the presence of high‐density lipoproteins and the high‐density lipoprotein scavenger receptor type B enhances SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in lung cells. 112 Flaviviruses, such as the Hepatitis C Virus, form structures with lipoproteins called lipoviroparticles that aid in virus spread and entry into host cells. 205 The possibility that SARS‐CoV‐2 has gained the ability to use lipoproteins produced by the choroid plexus as Trojan horse lipoviroparticles should be taken seriously. 206

There have been some unusual cases of SARS‐CoV‐2 being detected in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients experiencing meningitis and encephalitis. 207 , 208 , 209 , 210 Although organoid models do not exactly phenocopy human disease, the studies discussed in this subsection of the review indicate that choroid plexus epithelial cells might release SARS‐CoV‐2 into the cerebrospinal fluid through rampant virus shedding and syncytia formation. Future research is needed to characterize the unusual role lipoproteins may have in facilitating SARS‐CoV‐2 spread along the blood vessels and choroid plexus of the brain.

4. THE HOST’S NEUROIMMUNE RESPONSE IN THE OLFACTORY SYSTEM DURING SARS‐COV‐2 INFECTION

4.1. SARS‐CoV‐2 infection downregulates homeostatic olfaction‐related gene expression

SARS‐CoV‐2‐induced anosmia has renewed interest in the neuroscience community to further elucidate the complex processes that are required for olfaction. Gradually, we are beginning to understand that the olfactory system has dynamic neuroimmune underpinnings, and SARS‐CoV‐2 has exposed its ON‐OFF switch.

When SARS‐CoV‐2(A‐D) begins infecting cells along the olfactory neuroepithelium of humans and hamsters, there is a widespread downregulation in the expression of thousands of homeostatic olfaction‐related genes. 211 For instance, even in areas with negligible virus, the gene expression of adenylyl cyclase 3, an important enzyme for odorant receptor signal transduction and specialization, 212 is shut off during SARS‐CoV‐2(A‐D) infection. 211 Genes encoding olfactory sensory neuron receptors are also downregulated in humans and hamsters during SARS‐CoV‐2(A‐D) infection 211 (Figure 3). Olfactory sensory neuron receptor expression returns to normal in anosmic patients postinfection, 213 which indicates that receptor loss is probably not the culprit in SARS‐CoV‐2‐induced anosmia. 213 Instead, sustentacular cells, the primary targets of SARS‐CoV‐2(A‐D) in the olfactory neuroepithelium, have dysregulated gene expression in anosmic patients postinfection. 213 After months recovering from SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, human sustentacular cells overwhelmingly express genes related to antigen presentation and interferon signaling. 213 With the discovery that SARS‐CoV‐2 can persist in the human olfactory mucosa for months postinfection, 175 it is possible that sustentacular cells express this antiviral phenotype in response to an underlying, chronic infection.

FIGURE 3.

SARS‐CoV‐2 infection stimulates the expression of antiviral genes, while downregulating homeostatic genes, in the olfactory neuroepithelium of rodents. As SARS‐CoV‐2 infects and replicates within ACE2‐expressing sustentacular cells, gene expression of homeostatic sustentacular cell markers decreases. In response to the growing SARS‐CoV‐2 virus burden, expression of inflammasome‐related genes, including AIM2, NLRP3, RIPK3, and ZBP1, is potentiated. As sloughing and inflammation accelerates, the expression of homeostatic olfactory receptors is suppressed. During the recovery phase, elevated levels of IFN‐γ and cytotoxic granules persist in olfactory epithelium, which could be indicative of an IFN‐γ CD8+ population that is also observed in the olfactory neuroepithelium of COVID‐19 patients following infection. The overexpression of CXCL10, an IFN‐γ‐inducible chemokine, supports histological evidence of a large macrophage population inundating the ethmoid turbinates. Figure created in Biorender

4.2. Immune cells migrate to the SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected olfactory neuroepithelium

SARS‐CoV‐2(A‐D) infection of the olfactory neuroepithelium causes an influx of a variety of immune cells into the ethmoid turbinates. In the olfactory neuroepithelium and lamina propria, resident macrophages survey the environment to recognize and neutralize pathogens. 214 In the incipient stages of SARS‐CoV‐2(A‐D) infection, levels of macrophage chemoattractants, including CCL5 and CXCL10, become elevated in the ethmoid turbinates of hamsters 177 , 211 (Figure 3). As the infection of the ethmoid turbinates progresses, an increasing number of Iba1+ macrophages infiltrate the neuroepithelium and swarm the sites of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection 172 , 175 , 215 , 216 (Figure 4). This robust macrophage response in the olfactory neuroepithelium is consistent with the high levels of Macrophage Inflammatory Protein‐1 Alpha (MIP‐1a) detected in the ethmoid turbinates of SARS‐CoV‐2(A‐D)‐infected hamsters. 177 The increased presence of granulocytes in the human nasal cavity 217 and myeloperoxidase‐containing cells in the hamster ethmoid turbinates has also been detected during acute infection 216 (Figure 4). Elevated CD4+ cell counts in the nasopharyngeal swabs of COVID‐19 patients 217 and increased gene expression of CD3, CD4, and CD86 in the ethmoid turbinates of SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected hamsters suggests that activated CD4+ T cells flood the ethmoid turbinates to aid in the clearance of SARS‐CoV‐2. 211 Mass cytometry of human nasopharyngeal swabs and RNA‐sequencing of the hamster ethmoid turbinates has confirmed that a large population of CD8+ T cells and Natural killer (NK) cells inundate the neuroepithelium during peak infection. 211 , 217 Cytotoxic factors, such as Perforin and Granzymes, are highly expressed in the SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected hamster olfactory neuroepithelium (Figure 3), suggesting that CD8+ T cells and NK cells are potentially involved in the eradication of SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected cells 211 (Figure 4). Nasal brushing of former COVID‐19 patients shows that a large IFN‐γ+ CD8+ T cell population can remain in the nasal mucosa at least 2‐16 months postinfection. 213 , 217

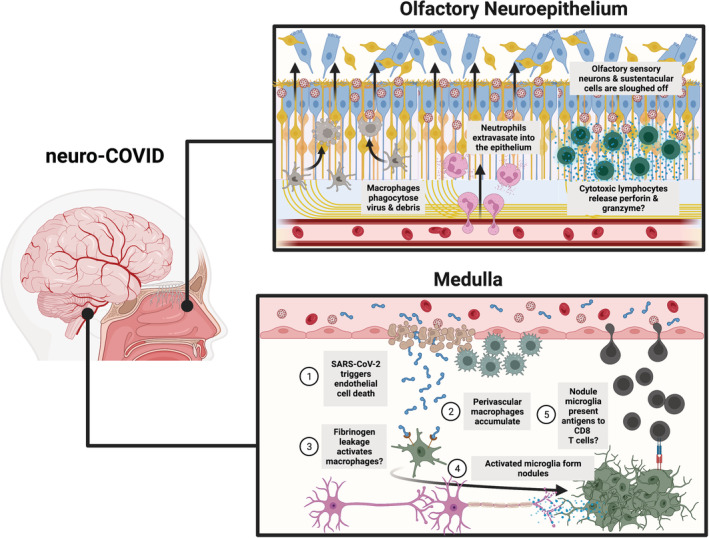

FIGURE 4.

SARS‐CoV‐2 infection along barriers of the nervous system yields an aberrant neuroimmune response. A working model of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection along the olfactory neuroepithelium (top): As SARS‐CoV‐2 rapidly infects ACE2‐expressing sustentacular cells, macrophages phagocytose extracellular virions and debris, and neutrophils extravasate into the neuroepithelium. Cytotoxic lymphocytes also migrate to the neuroepithelium, presumably to release perforin and granzyme, and remain in the neuroepithelium for months postinfection. A working model of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection along the blood‐brain barrier (BBB) of the medulla (bottom): SARS‐CoV‐2 infects endothelial cells and triggers RIPK1‐mediated cell death, thus damaging the integrity of the BBB. Fibrinogen then supposedly leaks into the parenchyma, which could lead to perivascular macrophage and microglia activation and subsequent microglia nodule‐mediated axon damage. Microglia in nodules present unidentified antigens to infiltrating CD8+ T cells. Figure created in Biorender

Overall, due to insufficient studies characterizing the identities of immune cells in the ethmoid turbinates, there is a major gap in our knowledge of how the immune response to nasal SARS‐CoV‐2 infection is orchestrated and whether these immune activities are detrimental to the surrounding nervous system milieu. Filling this gap in knowledge will ultimately pave the way for designing next‐generation intranasal vaccines against SARS‐CoV‐2 to prevent its spread and the anosmia that it causes.

4.3. Sloughing of the olfactory neuroepithelium during SARS‐CoV‐2 infection

As SARS‐CoV‐2(A‐D) continues to infect host cells along the olfactory neuroepithelium of humans and rodents, the structure of the neuroepithelium is destabilized which facilitates the sloughing (i.e., desquamation) of infected and non‐infected cells into the nasal lumen. 172 , 175 , 177 , 215 During SARS‐CoV‐2(A‐D) infection, olfactory sensory neurons and sustentacular cells are released into the luminal space.

Similar to the process of anoikis in the intestinal epithelium, apoptosis only occurs after the detachment of the cell from the olfactory neuroepithelium. 175 , 216 This sloughing of the olfactory neuroepithelium occurs through an unknown mechanism that appears to be neutrophil‐mediated. 216 Treatment with a Cathepsin C inhibitor reduced the amount of cells expulsed into the nasal lumen following SARS‐CoV‐2(Beta) intranasal inoculation of Syrian golden hamsters. 216 It seems likely that the sloughing of the olfactory neuroepithelium is a protective mechanism to clear pathogens from the ethmoid turbinates. However, Cathepsin C inhibition and suppression of sloughing limited SARS‐CoV‐2 spread along the olfactory neuroepithelium. 216 Therefore, the sloughing of infected cells could instead aid in spreading infectious virions to non‐infected sites of respiratory epithelium and olfactory epithelium. In theory, SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected sloughed cells could also travel from the nasal cavity to the larynx via “post‐nasal drip,” providing SARS‐CoV‐2 access to highly vulnerable, ACE2‐expressing acini and duct cells in the salivary gland mucosa. 218

We have yet to fully understand the extent of the sloughing in the olfactory neuroepithelium during SARS‐CoV‐2(A‐D) infection and how much of this phenomenon contributes to SARS‐CoV‐2‐induced anosmia. Olfactory sensory neurons are one of the cell types that are sloughed into the lumen so the loss of these neurons may alter normal olfaction. A study with SARS‐CoV‐2(WA1)‐infected Syrian hamsters asserts that the sloughing of the olfactory neuroepithelium thickness along the ethmoid turbinates negatively correlates with olfactory function, according to a buried food test. 219 The intensity of sloughing along the olfactory neuroepithelium could be a measure to predict the duration of prolonged anosmia following infection.

If the vast majority of cells along the olfactory neuroepithelium are sloughed off, horizontal basal cells will need more time to multiply and give rise to an intact, multilayered olfactory neuroepithelium that supports normal olfaction. It is unknown whether horizontal basal cells are also sloughed into the lumen during infection. If the death or sloughing of horizontal basal cell does occur as observed in dichlorobenzonitrile poisoning, 220 this would further delay and possibly prevent the regeneration of the olfactory neuroepithelium.

The expulsion of the olfactory neuroepithelium has been observed in healthy 221 and cyclophosphamide‐immunosuppressed hamsters 222 infected with SARS‐CoV, demonstrating that this is a phenotype that is conserved across sarbecoronavirus infections. In contrast, sloughing of the olfactory neuroepithelium is not observed during Omicron infection in rodents which is most likely due to the lack of efficient Omicron replication in the ethmoid turbinates. 78 , 80 , 172 Although the frequency of anosmia among COVID‐19 patients infected with Omicron is slightly reduced, anosmia is still a common symptom for patients infected with Omicron indicating that sloughing cannot be the only factor that contributes to SARS‐CoV‐2‐induced anosmia. 3

4.4. The repair of the olfactory neuroepithelium during SARS‐CoV‐2 infection

When the olfactory neuroepithelium is damaged by a pathogen, toxin, or physical trauma, horizontal basal cells are needed to regenerate the many layers of the epithelium. Within 18 hours postinjury in the murine olfactory neuroepithelium, horizontal basal cells downregulate their p63‐controlled dormancy state and become activated, proliferative stem cells. 223 , 224 Within 4 days postinfection, a large population of active, Ki67‐cycling horizontal basal cells is observed in the olfactory neuroepithelium of SARS‐CoV‐2(A‐D)‐infected hamsters. 172 Moreover, the expression of horizontal basal cell markers is upregulated in the ethmoid turbinates of hamsters during early acute SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. 211 It is unknown how early horizontal basal cells start self‐renewing during SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in humans. Regeneration following SARS‐CoV‐2 infection could vary by species. According to tongue biopsies of COVID‐19 patients, the stem cell layer of the fungiform papillae taste cells can have reduced cell mitosis for at least 6‐weeks postinfection, contributing to the prolonged loss of taste that COVID‐19 patients experience. 225 Therefore, it is possible that horizontal basal cell proliferation is hindered for weeks post‐SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in humans.

Chronic rhinosinusitis experiments suggest that the regenerative capacity of horizontal basal cells is silenced by chronic inflammation. 226 , 227 NF‐κB‐activation of horizontal basal cells causes these cells to release pro‐inflammatory factors such as CXCL10 to support the local proliferation of macrophages and T cells. 227 Pro‐inflammatory factors such as CXCL10 and immune cells including granulocytes and resident memory T cells remain elevated in the human nasal cavity months after SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. 175 , 217 Therefore, it is quite possible that the proliferative capacity of horizontal basal cells is suppressed by chronic inflammation postinfection thus abrogating the regeneration of the olfactory neuroepithelium. This phenomenon could be a major cause of prolonged SARS‐CoV‐2‐induced anosmia.

SARS‐CoV‐2 infection of sustentacular cells and their subsequent desquamation from the neuroepithelium could have a negative impact on the horizontal basal cells’ capacity to regenerate olfactory sensory neurons. The olfactory neuroepithelium has an olfactory sensory neuron‐independent Jagged1‐notch1 fail‐safe mechanism in place to facilitate the replenishment of sustentacular cells following injury or ablation. 228 However, to our knowledge, all identified mechanisms for the replenishment of olfactory sensory neurons following injury are sustentacular cell dependent. In theory, as the somas and dendrites of olfactory sensory neurons are sloughed off following damage to the neuroepithelium, extracellular ATP levels rise in the nasal lumen. 229 , 230 , 231 Sustentacular cells detect this increase in extracellular ATP via their purinergic receptors. 232 According to bulk RNA‐sequencing, active SARS‐CoV‐2 infection of the hamster olfactory neuroepithelium promotes the overexpression of P2RY1, P2RY2, P2RY6, P2RY12, P2RY13, and P2RY14. 211 Once these purinergic receptors are activated on sustentacular cells, the cell membrane becomes hyperpolarized by the release of calcium from intracellular reserves and the influx of potassium. 233 , 234 , 235 As a result, neighboring sustentacular cells synchronize their hyperpolarization oscillations through gap junctions to generate the secretion of neurotrophic neuropeptide Y. 231 , 233 , 234 Activation of neuropeptide Y receptors on horizontal basal cells evokes p44/42 ERK‐mediated differentiation of horizontal basal cells into immature olfactory sensory neurons. 236 , 237 , 238 The gene encoding neuropeptide Y is one of the most downregulated genes in the nasal neuroepithelium of SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected hamsters. 211 Therefore, as SARS‐CoV‐2 infection causes rampant sloughing of sustentacular cells, the restoration of the neuropeptide Y‐secreting sustentacular cell population might be required before horizontal basal cells can start replenishing the olfactory sensory neuron population during recovery. Hinderance to any of these regenerative processes might explain the low olfactory sensory neuron to sustentacular cell ratio in the olfactory epithelium of anosmic COVID‐19 patients postinfection. 213

4.5. SARS‐CoV‐2‐induced anosmia across species

Approximately 70% of SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected, PCR‐positive individuals self‐report anosmia. 239 Quantitative olfactometry on former COVID‐19 patients determined that olfactory dysfunction persists in approximately 60% of individuals for at least 6 months postinfection. 240 Many research groups claim that SARS‐CoV‐2‐induced anosmia can be recapitulated in humanized mice, hamsters, and zebrafish, but these assertions should be taken with caution. For instance, zebrafish inoculated with the SARS‐CoV‐2 Spike receptor‐binding domain display “impaired olfaction,” according to a food odor choice test. 241 However, this behavior impairment is likely the result of global neurological deficits. There is mounting evidence that the SARS‐CoV‐2 Spike protein’s receptor‐binding domain has sequence homology with neurotoxins 242 and causes rampant neurotoxicity in aquatic life. 241 , 243

Meanwhile, the buried food test has been relied upon to study SARS‐CoV‐2‐induced anosmia with rodent models. SARS‐CoV‐2(A‐D)‐infected humanized mice and hamsters have exhibited “decreased olfactory function” by finding buried food less often during infection. 175 , 176 , 219 However, the buried food test has major caveats and there are problems with how the behavior test was performed in these studies. To aid the field in developing an animal model for SARS‐CoV‐2‐induced anosmia, here are some guidelines that should be followed to increase the validity and reliability of buried food tests for assessing SARS‐CoV‐2‐induced anosmia.

First, as rodents perform the buried food test daily for 3 weeks, their latency to find the buried food drastically decreases from a latency of ~200 to ~50 s. 244 This is evidence that olfaction sensitivity or memory recall for a specific odor stimulus increases over time. To account for this confounding variable, experimenters should repeat the buried food test daily in naïve mice until their latency to find the buried food plateaus. 244 Once the latency to find the buried food has plateaued during the training phase, SARS‐CoV‐2 inoculation can occur to observe changes in food finding.

Second, decreased food retrieval during SARS‐CoV‐2 infection can be due to sickness behavior. The lack of appetite or activity during SARS‐CoV‐2 infection could alter the food finding abilities of rodents. To partially account for this confounding variable, the movement of the mice in the buried food test arena should be quantified. Mock‐infected mice can be treated with pharmacological agents (e.g., methimazole) to transiently impair olfaction without sickness behavior, thus serving as appropriate positive controls in the experiment. 244

Overall, due to the intensive labor required for training animals for reliable olfaction‐related behavior tests in a biosafety level 3 laboratory, it is recommended that the field shifts toward quantitative olfactometry. Plethysmography of odor‐evoked sniffing would be a more reliable method for measuring olfaction in SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected rodents even if they are presenting with sickness behavior and reduced appetite.

5. THE HOST’S NEUROIMMUNE RESPONSE IN THE BRAIN DURING SARS‐COV‐2 INFECTION

5.1. SARS‐CoV‐2 infection promotes antiviral activity along the cerebrovasculature and choroid plexus

Recent studies utilizing single‐nucleus RNA‐sequencing and spatial transcriptomics suggest that robust interferon‐related signaling is occurring along the blood‐brain barrier (BBB) of COVID‐19 patients. 189 , 245 IFITM1 and IFITM2 expression is upregulated along the blood vessels of the frontal cortex, 245 while IFITM3 is highly upregulated in cortical astrocytes and in all types of cells residing in the choroid plexus of COVID‐19 patient brains. 189 Although IFITM activity constrains the successful entry of pseudotyped SARS‐CoV 35 , 246 and MERS‐CoV 247 in vitro, bat‐derived SARS‐like viruses and SARS‐CoV‐2 can partially evade IFITM detection in the endosome through TMPRSS2‐dependent processes. 35 , 248 , 249 , 250 Upon further exploration, it was discovered that the accumulation of IFITM3 on the plasma membrane promotes, rather than restricts, SARS‐CoV‐2 infection of host cells in vitro. 250 Hence, enhanced IFITM activity along the barriers of the brain might decrease the frequency of SARS‐CoV‐2‐endosome fusion but increase the frequency of SARS‐CoV‐2‐plasma membrane fusion on the blood‐brain barrier. An overexpression of genes related to antigen processing and major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC I) antigen presentation is also observed in the neurovascular unit during severe COVID‐19, 245 which is most likely the result of both IFN‐γ stimulation 251 and SARS‐CoV‐2 directly infecting endothelial cells. 146

As the choroid plexus is a vulnerable location for SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, it should come as no surprise that monocytes/macrophages account for a significant fraction of total cells in the choroid plexus of COVID‐19 patients compared with control patients. 252 It is unclear whether this large monocyte/macrophage population in the choroid plexus is further infiltrating the surrounding periventricular parenchyma during COVID‐19. Markers of macrophage activation, complement signaling, and oxidative stress are upregulated in the choroid plexus 189 —all of which are common immune processes observed in SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected tissues. Meanwhile, the cellular fraction of mesenchymal cells is also highly elevated in the choroid plexus of COVID‐19 patients. 189 , 252 Throughout life, choroid plexus mesenchymal cells express colony‐stimulating factor 1 (CSF‐1), which is an important signal for macrophage/microglia survival in the brain. 253 Further research is needed to determine whether CSF‐1‐producing mesenchymal cells are crucial for the preservation of CSF1R+ macrophage populations and macrophage‐mediated antiviral activity in the choroid plexus.

5.2. Microglia nodules form in the brain parenchyma during severe COVID‐19

To date, there is a lack of evidence that SARS‐CoV‐2(A‐D) invades the brain parenchyma. Instead, the nidus of SARS‐CoV‐2(A‐D) infection in the CNS is localized to the cerebrovasculature. Large populations of perivascular macrophages and T cells are frequently observed congregating around blood vessels to presumably prevent further infection in the brains of COVID‐19 patients. 170 , 187 , 189 , 190 , 254

However, the most intense pro‐inflammatory activity in the COVID‐19 brain occurs in the parenchyma. Microgliosis, perivascular macrophage accumulation, and microglia aggregates, known as nodules, are frequently observed in the brain parenchyma of patients who succumb to COVID‐19 170 , 187 , 190 (Figure 4). In line with these findings, microglia in the frontal cortex exhibit a variety of differentially expressed genes, including those associated with antigen presentation, 189 iron storage, 189 and NK cell‐mediated cytotoxicity. 252

The formation of microglia nodules in the COVID‐19 brain has received growing attention because nodules are associated with axon damage in viral encephalitis, 255 , 256 , 257 multiple sclerosis, 258 , 259 , 260 Rasmussen encephalitis, 261 , 262 and aging white matter. 263 Despite the close proximity of the olfactory bulb to the SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected and inflamed olfactory neuroepithelium, few microglia nodules are found there. 190 Instead, caudal locations of the human COVID‐19 brain, especially the medulla and pons, are burdened with microglia nodules. 170 , 190 Whether it is the direct result of SARS‐CoV‐2 killing endothelial cells or the indirect result of chronic systemic inflammation, the BBB loses its integrity and neurovascular leakage of fibrinogen, a liver‐derived protein, is observed in the brain parenchyma of COVID‐19 patients. 190 , 254 The buildup of fibrinogen in the parenchyma may contribute to the clustering of activated perivascular macrophages and microglia in the tissue 264 (Figure 4). In addition, the increased BBB permeability allows CD8+ T cells to infiltrate the brain parenchyma. 190 If the pathogenesis of COVID‐19 microglia nodules mimics other encephalitides featuring nodules, the infiltrating CD8+ T cells will migrate to pre‐formed microglia nodules. 261 Within the microglia nodules of the medulla, a heterogenous population of CD8+ T cells display phenotypic markers of activated effector T cells, cytotoxic T cells, proliferating T cells, and exhausted T cells. 190 It is hypothesized that intimate and extensive crosstalk between microglia and infiltrating CD8+ T cells is occurring at these sites. For instance, the high density of MHC II+ microglia and PD‐L1+ microglia within these nodules suggests that microglia are presenting antigens while actively regulating the responses of the CD8+ T cells. 190 In chronic active multiple sclerosis lesions, HLA‐DR+ microglia nodules are co‐localized with amyloid‐precursor protein (APP) deposits, which is indicative of axonal injury following demyelination. 260 Surprisingly, abnormal APP deposits were observed in the brains of COVID‐19 patients with high microglia nodule burden. 190 To date, no histopathological features of demyelination have been observed in the COVID‐19 brain. Yet, if microglia‐mediated demyelination or axonal injury is happening in the COVID‐19 brain, the observed neurovascular leakage of fibrinogen in COVID‐19 will prevent any remyelination efforts. Fibrinogen inhibits oligodendrocyte progenitor cell (OPC) differentiation and suppresses remyelination by activating the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling pathway. 265

Further investigation will be needed to illuminate the mechanistic role of microglia nodules in the COVID‐19 brain. From the limited number of postmortem examinations of brains from COVID‐19 patients, it is difficult to ascertain if microglia nodules are localized to only the white matter, as observed in autoimmune diseases, 258 , 262 or if microglia take on a diffuse patterning, as is often observed in viral encephalitis. 257 In addition, should microglia nodules prove to have a pathogenic role in the COVID‐19 brain, Triggering Receptor Expressed on Myeloid Cells 2 (TREM2)‐antagonizing therapies could be a promising treatment because microglia nodule formation requires TREM2‐mediated phagocytosis. 263 , 266 Most of all, it is crucial to uncover which antigens are being presented by microglia to CD8+ T‐cells in the nodules; self‐antigens would be indicative of an attack‐on‐self, whereas SARS‐CoV‐2 antigens would suggest an overprotective immune response.

5.3. Evidence of a complex innate and adaptive immune response in the central nervous system of neuro‐PASC patients

Some survivors of COVID‐19 experience persistent neuro‐PASC (postacute sequalae of SARS) for many months postinfection. Although the immune response in the CSF does not mirror the brain, the extraction of CSF from these COVID‐19 survivors provides us with insights into the immune processes occurring in the CSF‐secreting areas of the brain (choroid plexus and interstitial tissue) following infection. Our first set of clues came from Heming and co‐workers: similar to the widespread T cell exhaustion detected in the blood of COVID‐19 patients, 267 , 268 neuro‐PASC patients have an expanded population of “exhausted” CD4+ T cells in their CSF compared to control patients with virus encephalitis. 269 Exhausted T cells are frequently associated with inadequate clearance of chronic infections, but all neuro‐PASC CSF samples in the study were negative for SARS‐CoV‐2. 269 The CSF of neuro‐PASC patients also exhibit greater proportions of border‐associated macrophages, microglia, and Clec10ahi granulocytes than control patients with virus encephalitis. 269

IL‐12 plays a pivotal and non‐redundant role in generating IFN‐γ‐producing NK cells and priming CD4+ and CD8+ T cells for adaptive immune responses in the brain, especially during Toxoplasma gondii infection. 270 CSF levels of IL‐12 are elevated in neuro‐PASC patients, while the IL‐12R receptor is highly expressed in the surrounding CD4+ and CD8+ T cell CSF populations of neuro‐PASC patients. 271 , 272 Despite a robust NK cell activation state in the blood of COVID‐19 patients during infection, 273 NK cells from the CSF of patients with neuro‐PASC have enhanced expression of genes associated with NK cell‐mediated cytotoxicity, antigen presentation, and chemoattraction, compared to plasma NK cells from the same neuro‐PASC patients. 271 Since SARS‐CoV‐2 infection of host cells can yield cellular senescence, it is plausible that these NK cells are eliminating senescent cells in the brain—a special NK cell activity that occurs during normal brain aging. 274 It remains unclear which cells are secreting IL‐12 in the CNS and what the motive might be for IL‐12 polarizing NK, CD4+, and CD8+ T cell responses in the CNS during neuro‐PASC.

Meanwhile, there is mounting evidence of a highly active adaptive immune response in the CSF of neuro‐PASC patients. Consistent with the high number of infiltrating B cells in the parenchyma of patients with fatal COVID‐19, 190 an increased frequency of B cells also exists in the CSF of neuro‐PASC patients. 271 Some IgG antibodies produced by these B cells in neuro‐PASC patients exhibit anti‐neural reactivity, 271 so more studies are needed to determine whether neuro‐PASC has autoimmune underpinnings.

6. CONCLUSION

The prevailing theory is that an overactive pro‐inflammatory immune response, during a hypoxic state, drives neuroinflammation and damage in the CNS of hospitalized COVID‐19 patients. The blood of hospitalized COVID‐19 patients is filled with pro‐inflammatory cytokines, and this dysregulated immune profile persists for months postinfection. 275 Building on this premise, high neurofilament light‐chain levels in the serum and CSF of hospitalized COVID‐19 patients are positively correlated with disease severity, suggesting that axonal injury occurs in tandem with global hyperinflammation during COVID‐19. 276 , 277 , 278 As a result, 6 months following hospital discharge, hospitalized COVID‐19 patients have an excess burden of ~60 per 1,000 persons with chronic fatigue and an excess burden of ~40 per 1,000 persons with memory problems, compared to PCR‐negative hospitalized patients. 279 The inability to recover from these neuro‐PASC complications for many previously hospitalized patients suggests that COVID‐19‐associated hyperinflammation and hypoxia have sowed the seeds for an underlying disease. Based on the current findings outlined in this review and the increased frequency of neuro‐PASC symptoms occurring in older individuals, 280 it is plausible that SARS‐CoV‐2 can exacerbate or trigger Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) in older patients.

COVID‐19 and AD share common traits. For instance, the orbitofrontal cortex and the entorhinal cortex within the parahippocampal gyrus have been identified through autopsies and positron emission tomography scanning of brains as two of the initial sites of early AD, consisting of phosphorylated tau tangles and beta‐amyloid (Aβ) aggregates. 281 , 282 , 283 The presence of tau and Aβ in the orbitofrontal cortex and parahippocampal gyrus positively correlate with gray matter loss in those areas in early AD. 284 Similarly, magnetic resonance imaging of brains from 785 UK Biobank participants revealed that, following SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, COVID‐19 patients have reduced gray matter thickness in their orbitofrontal cortex and parahippocampal gyrus. 285 Another common trait between COVID‐19 and AD is the APOE4 allele, which may support SARS‐CoV‐2 tropism. Two copies of the APOE4 allele raise an individual’s risk of developing AD 286 and severe COVID‐19. 287 Most of all, anosmia, a common symptom of COVID‐19, enhances the risk of a person carrying the APOE4 allele to develop AD. 288

Another major takeaway from this review is that bat‐derived sarbecoronaviruses, which have a high frequency of crossing the species barrier and an uncanny ability to adapt to new hosts without sacrificing virulence factors, are a constant threat to the global human population. 18 , 289 We now know that bat‐derived sarbecoronaviruses are already poised for human emergence again. 290 In addition, SARS‐CoV‐2 has established a new natural reservoir for sarbecoronaviruses in a variety of species. Because SARS‐CoV‐2 is neurotropic in the olfactory systems of wild rodent species, there is now the worry that sarbecoronaviruses will become increasingly acquainted with the mammalian nervous system. Therefore, with no pan‐sarbecoronavirus vaccine in sight, there is a considerable need to further investigate how SARS‐CoV‐2 damages the peripheral olfactory system and central nervous system to prepare for future sarbecoronavirus pandemics and the potential neuro‐PASC epidemics that follow.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed to the writing, review, and editing of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We apologize to authors whose work could not be referenced in this review due to space limitations. Graphical illustrations were made using BioRender (https://biorender.com/). This work was supported by grants from the Manning Family Foundation (awarded to W.A.P.), Ivy Foundation (awarded to W.A.P.), Henske Family (awarded to W.A.P.), NIH R01 AI124214 (awarded to W.A.P.), NIH R01 NS106383 (awarded to J.R.L.), The Alzheimer’s Association AARG‐18‐566113 (awarded to J.R.L.), and The Owens Family Foundation (awarded to J.R.L.). N.R.N. was supported by the Global Biothreats Training Grant (NIH T32 AI055432‐19).

Natale NR, Lukens JR, Petri WA. The nervous system during COVID‐19: Caught in the crossfire. Immunol Rev. 2022;00:1‐22. doi: 10.1111/imr.13114

*This article introduces a series of reviews covering Neuroimmunology appearing in Volume 311 of Immunological Reviews.

Contributor Information

John R. Lukens, Email: jrl7n@virginia.edu.

William A. Petri, Jr, Email: wap3g@virginia.edu.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Not applicable

REFERENCES

- 1. Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579(7798):270‐273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Merad M, Blish CA, Sallusto F, Iwasaki A. The immunology and immunopathology of COVID‐19. Science. 2022;375(6585):1122‐1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Whitaker M, Elliott J, Bodinier B, et al. Variant‐specific symptoms of COVID‐19 among 1,542,510 people in England. Published online May 23, 2022:2022.05.21.22275368. 10.1101/2022.05.21.22275368 [DOI]

- 4. Wang H, Paulson KR, Pease SA, et al. Estimating excess mortality due to the COVID‐19 pandemic: a systematic analysis of COVID‐19‐related mortality, 2020–21. Lancet. 2022;399(10334):1513‐1536. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02796-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Paludan SR, Mogensen TH. Innate immunological pathways in COVID‐19 pathogenesis. Sci Immunol. 2022;7(67):eabm5505. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abm5505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Spudich S, Nath A. Nervous system consequences of COVID‐19. Science. 2022;375(6578):267‐269. doi: 10.1126/science.abm2052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Andersen KG, Rambaut A, Lipkin WI, Holmes EC, Garry RF. The proximal origin of SARS‐CoV‐2. Nat Med. 2020;26(4):450‐452. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0820-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. V’kovski P, Kratzel A, Steiner S, Stalder H, Thiel V. Coronavirus biology and replication: implications for SARS‐CoV‐2. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021;19(3):155‐170. doi: 10.1038/s41579-020-00468-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cui J, Li F, Shi ZL. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17(3):181‐192. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0118-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rihtarič D, Hostnik P, Steyer A, Grom J, Toplak I. Identification of SARS‐like coronaviruses in horseshoe bats (Rhinolophus hipposideros) in Slovenia. Arch Virol. 2010;155(4):507‐514. doi: 10.1007/s00705-010-0612-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tong S, Conrardy C, Ruone S, et al. Detection of Novel SARS‐like and Other Coronaviruses in Bats from Kenya. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15(3):482‐485. doi: 10.3201/eid1503.081013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li F, Li W, Farzan M, Harrison SC. Structure of SARS Coronavirus Spike Receptor‐Binding Domain Complexed with Receptor. Science. 2005;309(5742):1864‐1868. doi: 10.1126/science.1116480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Luo CM, Wang N, Yang XL, et al. Discovery of novel bat coronaviruses in South China that use the same receptor as middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Virol. 2018;92(13):e00116‐e00118. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00116-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Starr TN, Zepeda SK, Walls AC, et al. ACE2 binding is an ancestral and evolvable trait of sarbecoviruses. Nature. 2022;603(7903):913‐918. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04464-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hofmann H, Pyrc K, van der Hoek L, Geier M, Berkhout B, Pöhlmann S. Human coronavirus NL63 employs the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus receptor for cellular entry. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;102(22):7988‐7993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409465102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wu K, Li W, Peng G, Li F. Crystal structure of NL63 respiratory coronavirus receptor‐binding domain complexed with its human receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106(47):19970‐19974. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908837106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Guan Y, Zheng BJ, He YQ, et al. Isolation and characterization of viruses related to the SARS coronavirus from animals in Southern China. Science. 2003;302(5643):276‐278. doi: 10.1126/science.1087139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Menachery VD, Yount BL, Debbink K, et al. A SARS‐like cluster of circulating bat coronaviruses shows potential for human emergence. Nat Med. 2015;21(12):1508‐1513. doi: 10.1038/nm.3985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Song HD, Tu CC, Zhang GW, et al. Cross‐host evolution of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus in palm civet and human. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;102(7):2430‐2435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409608102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Xiao X, Newman C, Buesching CD, Macdonald DW, Zhou ZM. Animal sales from Wuhan wet markets immediately prior to the COVID‐19 pandemic. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):11898. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-91470-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. He B, Zhang Y, Xu L, et al. Identification of diverse alphacoronaviruses and genomic characterization of a novel severe acute respiratory syndrome‐like coronavirus from bats in China. J Virol. 2014;88(12):7070‐7082. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00631-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li W, Shi Z, Yu M, et al. Bats are natural reservoirs of SARS‐Like coronaviruses. Science. 2005;310(5748):676‐679. doi: 10.1126/science.1118391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ge XY, Li JL, Yang XL, et al. Isolation and characterization of a bat SARS‐like coronavirus that uses the ACE2 receptor. Nature. 2013;503(7477):535‐538. doi: 10.1038/nature12711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hu B, Zeng LP, Yang XL, et al. Discovery of a rich gene pool of bat SARS‐related coronaviruses provides new insights into the origin of SARS coronavirus. Drosten C, ed. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13(11):e1006698. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yang XL, Hu B, Wang B, et al. Isolation and Characterization of a Novel Bat Coronavirus Closely Related to the Direct Progenitor of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus. J Virol. 2016;90(6):3253‐3256. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02582-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang N, Li SY, Yang XL, et al. Serological evidence of bat SARS‐related coronavirus infection in humans. China Virol Sin. 2018;33(1):104‐107. doi: 10.1007/s12250-018-0012-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Holmes EC, Goldstein SA, Rasmussen AL, et al. The origins of SARS‐CoV‐2: A critical review. Cell. 2021;184(19):4848‐4856. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.08.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhou H, Ji J, Chen X, et al. Identification of novel bat coronaviruses sheds light on the evolutionary origins of SARS‐CoV‐2 and related viruses. Cell. 2021;184(17):4380‐4391.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lam TTY, Jia N, Zhang YW, et al. Identifying SARS‐CoV‐2‐related coronaviruses in Malayan pangolins. Nature. 2020;583(7815):282‐285. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2169-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wrobel AG, Benton DJ, Xu P, et al. Structure and binding properties of Pangolin‐CoV spike glycoprotein inform the evolution of SARS‐CoV‐2. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):837. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21006-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wacharapluesadee S, Tan CW, Maneeorn P, et al. Evidence for SARS‐CoV‐2 related coronaviruses circulating in bats and pangolins in Southeast Asia. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):972. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21240-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]