Abstract

In Salmonella dublin, rpoS encodes an alternative sigma factor of the RNA polymerase that activates a variety of stationary-phase-induced genes, including some virulence-associated genes. In this work, we studied the regulation and transcriptional organization of rpoS during growth. We found two transcripts, 2.3 and 1.6 kb in length, that represent the complete rpoS sequence. The 2.3-kb transcript is a polycistronic message that also includes the upstream nlpD gene. It is driven by a weak promoter with increasing activity when cells enter early stationary growth. The 1.6-kb message includes 566 bp upstream of the rpoS start codon. It is transcribed from a strong ς70 RNA polymerase-dependent promoter which is independent of growth. The decay of this transcript decreases substantially in early stationary growth, resulting in a significant net increase in rpoS mRNA levels. These levels are approximately 10-fold higher than the levels of the 2.3-kb mRNA, indicating that the 1.6-kb message is mainly responsible for RpoS upregulation. In addition to the 2.3- and 1.6-kb transcripts, two smaller 1.0- and 0.4-kb RNA species are produced from the nlpD-rpoS locus. They do not allow translation of full-length RpoS; hence their significance for rpoS regulation remains unclear. We conclude that of four transcripts arising from the nlpD-rpoS locus, only one plays a significant role in rpoS expression in S. dublin. Its upregulation when cells enter stationary growth is due primarily to an increase in transcript stability.

Many bacteria adapt to changing growth conditions by using alternative sigma factors that mediate the expression of particular sets of genes. In enteric bacteria such as Escherichia coli and Salmonella, Shigella, and Yersinia spp., ς70 is the housekeeping sigma factor responsible for the transcription from the majority of the promoters (13). During transition to the stationary growth phase, RpoS is produced as an alternative sigma factor, also known as ςS or ς38 (30, 31). RpoS rapidly triggers the expression of a variety of genes which enhance the viability under various stress conditions (reviewed in references 14, 24, and 25). In virulent, nontyphoid Salmonella, RpoS was also found to be responsible for the expression of the Salmonella plasmid virulence (spv) genes (6, 10, 12, 17).

Most studies concerning the regulation of rpoS itself were carried out in E. coli, where the expression of rpoS is induced during the transition from exponential to stationary growth phase (22). At least two promoters controlling rpoS transcription have been identified. The major promoter is located in the coding region of the nlpD gene upstream of rpoS, whereas the second promoter is upstream of the nlpD gene, resulting in a polycistronic transcript of nlpD and rpoS (20, 35). Whereas transcription from the rpoS main promoter was found to be induced during transition to stationary phase, nlpD expression was not induced during growth (21, 22). The cellular concentrations of RpoS are further controlled at the translational and posttranslational levels by mechanisms involving several protein factors (2, 4, 5, 28, 29, 36) as well as some nonprotein regulatory factors (15, 20, 22).

In this study, we determined the DNA sequence upstream of rpoS in Salmonella dublin Lane and studied the regulation of rpoS expression throughout growth of batch cultures. Although the sequence including the corresponding nlpD gene was found to be very similar to that of E. coli, we identified some distinct differences between the two species in the control of rpoS expression. Northern and immunoblot analyses and mRNA decay assays revealed that the initiation of rpoS expression in the late exponential growth phase is due primarily to an increase in mRNA stability.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

The strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. S. dublin Lane is a clinical blood isolate which contains the virulence plasmid pSDL2. S. dublin LD842 is the pSDL2-cured avirulent derivative of S. dublin Lane (7). CC1002 and CC1003 are rpoS mutants of S. dublin Lane and LD842, respectively (6). E. coli TB1 (2) and SK383 (37) were used for cloning and plasmid constructions. To transform S. dublin, plasmids were first passed through the restriction-deficient S. typhimurium LB5000 (9).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Characteristics | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| TB1 | JM83 hsdR (rK−mK+) | 3 |

| SK383 | dam-4 | 37 |

| S. typhimurium LB5000 | rLT− rSA− rSB− | 9 |

| S. dublin | ||

| CC1002 | rpoS mutant of S. dublin Lane | 6 |

| CC1003 | rpoS mutant of S. dublin LD842 | 6 |

| Lane | Wild type, contains the virulence plasmid pSDL2 | 11 |

| LD842 | Plasmid-cured S. dublin Lane | 7 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBB4 | pTrc99a containing the 1,069-bp BclI-BspHI region upstream of rpoS | This work |

| pRSP70 | pRS551 containing a 389-bp RsaI fragment carrying the rpoS promoter | This work |

| pRSNL | pRS551 containing a 477-bp PCR fragment carrying the nlpD promoter | This work |

Bacterial cultures were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth. When required, appropriate antibiotics were added to the following final concentrations: penicillin G, 200 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 20 μg/ml; and tetracycline 2 μg/ml. To ensure that the bacteria were in exponential growth, overnight cultures were diluted 1:100 in fresh LB medium and incubated at 37°C with vigorously shaking (300 rpm). After 1 h, the cultures were diluted again 1:100. The growth of the bacterial cultures was monitored by measuring the optical density at 600 nm (OD600).

DNA manipulations.

Plasmid clone analysis, cleavage with restriction endonucleases, agarose gel electrophoresis, ligations, and transformations were performed according to standard methods (32). For DNA sequencing, a T7 sequencing kit (Pharmacia) and [α-35S]thio-dATP (>1,000 Ci/mmol; Amersham) were used. Sequencing of the complementary strand was performed to confirm all sequences.

Plasmids.

The plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. pBB4 is a pTrc99a (1) derivative which carries a 1,069-bp BclI-BspHI fragment containing the first 23 bp of the S. dublin rpoS coding region and the upstream region of the rpoS gene. pRSP70 is a pRS551-based (33) transcriptional fusion of a 389-bp RsaI fragment containing the putative rpoS promoter and the transcriptional start site with the lacZ gene. A 477-bp-long fragment containing the putative promoter, the translational start site, and the first 358 bp of the Salmonella nlpD gene was amplified by PCR using the primers 5′-TTTCCTGGTTATTCCGGTGG-3′ and 5′-GTACTGCCACCCGTATAGC-3′. Cloning of this fragment into pRS551 resulted in the transcriptional fusion vector pRSNL.

RNA preparation and Northern blotting.

Total RNA from samples of about 109 cells was isolated as described earlier (18, 23). The RNA was precipitated overnight with ethanol, and the pellet was stored at −80°C until further use. Prior to electrophoresis the RNA pellet was dissolved in 5 μl of 25 mM EDTA–0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 25 μl of electrophoresis sample buffer (50% deionized formamide, 16% formaldehyde, and 7% glycerol in 20 mM MOPS–5 mM sodium acetate–1 mM EDTA) was added. The samples were normalized to equal amounts of total RNA. After heating for 15 min at 65°C, the samples were electrophoresed on horizontal denaturing formaldehyde-agarose gels and transferred to a Nytran N nylon membrane (Schleicher & Schuell). The probes were randomly labeled by using a Rediprime kit (Amersham). The membranes were manipulated according to the Rapid-hyb buffer protocol (Amersham).

Primer extension.

The oligonucleotides used as primers were 5′-CTTTCAGCGTATTCTGAC-3′ (complementary to the 5′ end of the rpoS gene) and 5′-CCTGTTGTTCCCGGACCAGC-3′ plus 5′-GTTGGTGCCGTTACAGGCGC-3′ (complementary to regions 185 and 482 bp upstream of the rpoS start codon). From each primer, a fragment of approximately 300 bp was run on the gels. The primers (10 pmol) were labeled by using a 5′-end labeling kit (Amersham), precipitated, and resuspended in 4 μl of sterile H2O. The RNA was resuspended in 4 μl of sterile H2O and mixed with the labeled primers; 5× annealing buffer (2 M NaCl, 5 mM PIPES [pH 7.0]) was added, and the mixture was heated to 100°C for 3 min, incubated for 5 min at 65°C, and then slowly cooled to 42°C; 40 μl of 1.25× avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase buffer containing 1 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate and 10 U of avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase was added, and the mixture was incubated for 1 h at 42°C. The reaction was stopped by addition of 5 μl of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 6.0) and 150 μl of cold ethanol; the pellet was washed and dissolved in 2 μl of 0.1 M NaOH. Finally 4 μl of formaldehyde stop and loading buffer (Pharmacia) was added, and the samples were loaded on 8% polyacrylamide–7 M urea or 6% Long Ranger–7 M urea (FMC Bioproducts) sequencing gels.

Determination of the rpoS mRNA half-life.

Rifampin, a potent inhibitor of RNA synthesis, was added to a final concentration of 300 μg per ml of cell culture. The cells were incubated at 37°C with vigorous shaking; after 3, 6, 9, and 12 min, samples of about 109 cells were taken and total RNA was prepared as described above. The samples were stored at −80°C until used for Northern blot analysis. The experiments were performed two to four times.

Protein analysis by immunoblotting.

Specific polyclonal antibodies against S. dublin RpoS were kindly provided by A. El-Gedaily. The specificity of the antibodies was tested by immunoblot analysis of whole-cell extracts of the S. dublin rpoS mutant strain CC1002 as a control (8). Western immunoblotting was performed as previously described (19). Proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (10 to 15% polyacrylamide) and transferred electrophoretically to nitrocellulose membranes. The samples were standardized to equal amounts of total protein. All samples were prepared under reducing conditions. After transfer to nitrocellulose membranes, nonspecific antibody binding was blocked by incubation in 4% (wt/vol) dried milk in Tris-buffered saline (pH 7.5) containing 0.05% (vol/vol) Tween 20. The blots were probed with rabbit polyclonal antibodies against RpoS. Binding of the primary antibody was detected by using horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibodies and enhanced chemiluminescence detection reagents (Amersham) followed by exposure to a radiographic film. The intensities of the protein bands were determined by densitometry (model GS-700 densitometer [Bio-Rad]; Molecular Analyst software). To construct the figures, the blots were scanned with Adobe Photoshop 3.0 software.

β-Galactosidase activity.

The standard procedure described by Miller (26) was used for quantitative measurements of β-galactosidase activity. Each experiment was performed at least three times on different days.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence determined has been deposited in the EMBL nucleotide sequence database under accession no. AJ006131.

RESULTS

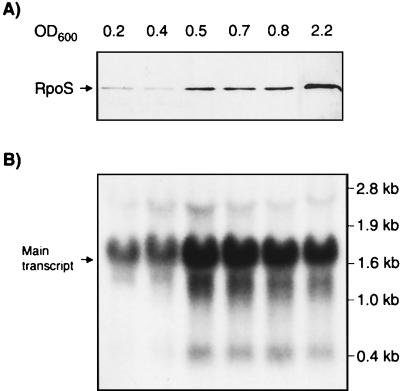

Cellular content of RpoS during growth.

We first established that RpoS concentrations increase in S. dublin when bacteria enter stationary phase. S. dublin had been grown to different OD600 values, and equal protein amounts of whole-cell extracts were analyzed by immunoblotting using specific anti-RpoS antibodies (Fig. 1A). The course of RpoS expression was characterized by (i) a low initial baseline in early logarithmic growth until an OD600 of 0.4, (ii) a sharp 10-fold rise between OD600 of 0.4 and 0.5, (iii) a plateau until an OD600 of 0.8, and (iv) a final approximately threefold rise at an OD600 of 2.2. These data clearly confirm that RpoS synthesis in S. dublin is growth regulated and suggest that at least two events at OD600 of approximately 0.4 to 0.5 and 0.8 to 2.2 result in significant increase of RpoS levels.

FIG. 1.

Comparison of the levels of RpoS protein (A) and rpoS mRNA (B) along the growth curve. Arrows mark the protein and mRNA main band, respectively. The samples were standardized to equal amounts of total cellular protein and total RNA, respectively.

Determination of the rpoS upstream sequence in S. dublin Lane.

The 1.5-kb upstream region of the rpoS coding region of S. dublin was sequenced and found to be very similar to the DNA sequence of E. coli that contained the nlpD gene. Sequence analysis revealed an 1,131-bp open reading frame oriented in the same direction as rpoS and an intergenic region of 350 bp. The deduced sequence of 377 amino acids revealed 88% identity to NlpD of E. coli. The signal sequence at the N terminus, the lipidation consensus sequence, and the 206 C-terminal amino acids of S. dublin and E. coli were conserved. Significant variations were found after the signal sequence between amino acid residues 62 and 93. In E. coli, this region has a high content of proline and glutamine arranged in characteristic repeats (16). In S. dublin Lane, no significant repeats were detected, although the content of prolines and glutamines was comparable to that in the E. coli protein. Interestingly, the putative nlpD promoter region of S. dublin was substantially different from that of E. coli by the absence of a typical −10 consensus sequence in the Salmonella promoter region (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

(A) Comparison of the nlpD promoter regions of S. dublin and E. coli (21). The two transcriptional start sites in E. coli and the translational start site are shaded; the −10 and −35 regions of the two promoters determined in E. coli are underlined; the corresponding sequences in S. dublin are marked. The −10 region of the promoter P1 is absent in S. dublin. (B) Determination of the 5′ end of the 1.6-kb main transcript by primer extension. The arrow shows the transcriptional start site. The −10 and −35 regions of the putative ς70 RNA polymerase-dependent promoter are also marked. Lanes A, C, G, and T represent the sequencing ladder using the same primer as used for the primer extension reaction.

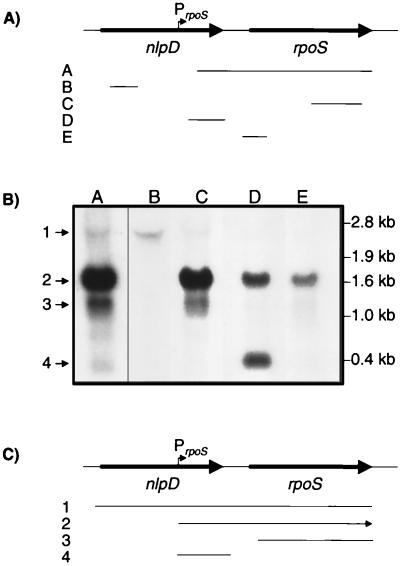

Mapping of the rpoS mRNA in S. dublin Lane.

To analyze the rpoS mRNA, we extracted total RNA from S. dublin Lane that had been grown to early stationary phase. The RNA was separated by electrophoresis and blotted on a membrane, and the blots were probed with an rpoS-specific probe that encompassed the complete rpoS gene including the 350-bp upstream region that overlaps the 3′ end of the nlpD gene. We identified four different bands with lengths of approximately 2.3, 1.6, 1.0, and 0.4 kb. To map these bands, we used four new probes corresponding to different regions of the rpoS mRNA (Fig. 3). The signal of the 2.3-kb transcript was fairly weak. It was found to be a polycistronic message including nlpD and rpoS. The most intense signal was provided by the 1.6-kb band, which corresponded to the complete rpoS gene including a large upstream segment. The precise transcriptional start of this message was identified by primer extension at 566 bp upstream of the ATG start codon of rpoS (Fig. 2B). The start site was at the same position as the start in E. coli and was preceded by a typical ς70 RNA polymerase-dependent promoter consensus sequence (22, 35). The remaining 1.0- and 0.4-kb bands encompassed only fragments of the rpoS main mRNA and do not allow translation of full-length RpoS. Thus, only the nlpD and rpoS promoters of the 2.3- and 1.6-kb mRNAs, respectively, control transcription of a complete rpoS message.

FIG. 3.

Mapping of the different rpoS mRNA transcripts. (A) The probes (A to E) used for the mapping. (B) Band patterns with the different probes. Lanes A to E correspond to probes A to E; bands 1 to 4 corresponds to the 2.3-, 1.6-, 1.0-, and 0.4-kb transcripts. (After longer exposure, the 2.3-kb band was also visualized in lanes D and E.) (C) Alignment of the identified transcripts to the DNA sequence. The arrowhead defines the 3′ end of the 1.6-kb main transcript.

Cellular levels of rpoS mRNA during growth.

To evaluate the role of rpoS transcription during the course of RpoS expression, we determined the amount of the specific rpoS mRNA along the growth curve. The mRNA from aliquots of approximately 109 cells at OD600 of 0.2, 0.4, 0.5, 0.7, 0.8, and 2.2 was extracted, and the 2.3- and 1.6-kb rpoS bands were analyzed by densitometry. We found that the 1.6- and 2.3-kb messages followed the same course, with intensities at a stable ratio of approximately 10:1 throughout the growth cycle. This clearly indicated that the 1.6-kb transcript is mainly responsible for RpoS production. It was remarkable that even in early exponential growth significant amounts of rpoS mRNA were present (Fig. 1B). Between an OD600 of 0.4 and 0.5 we observed a significant (approximately threefold) increase. During continued growth the rpoS mRNA level decreased slightly, and in late stationary phase it had declined to about two-thirds of the maximum level. The distinct peak of mRNA at an OD600 of 0.5 corresponds well with the cellular RpoS, indicating that at this growth stage the sharp increase of RpoS is basically the result of increased transcription. At an OD600 of 2.2, however, the levels of rpoS mRNA and RpoS proteins diverge, indicating that at that stage, RpoS is regulated mainly translationally or posttranslationally.

Analysis of nlpD and rpoS promoter activity.

Next, we analyzed the activities of the rpoS and nlpD promoters, which are responsible for generation of the 1.6- and 2.3-kb transcripts, respectively. The transcriptional lacZ fusion vectors pRSP70 and pRSNL, containing 389- and 477-bp fragments from the upstream regions of rpoS and nlpD, respectively, were transferred into S. dublin Lane, and β-galactosidase levels were determined at time points along the growth curve (Fig. 4). The activity pattern of the nlpD promoter was found to be growth phase dependent. After a twofold increase at an OD600 of 0.4 to 0.5, a gradual decrease during prolonged growth was observed. The β-galactosidase levels from the rpoS 1.6-kb transcript promoter were approximately 5- to 10-fold higher and, in contrast to the 2.3-kb transcript, were found to be constant throughout the whole cycle. Even in the very early exponential phase, we found high levels of activity (approximately 20,000 Miller units) that remained constant until late stationary phase. This finding was verified by Northern blot analysis using a probe complementary to the lacZ mRNA (data not shown), confirming that the rate of transcription was not growth phase dependent. Whereas the nlpD promoter activity corresponds well with the 2.3-kb mRNA levels, there exists an obvious discrepancy between the activity of the rpoS promoter and the amount of 1.6-kb message, indicating that the cellular level of this transcript is posttranscriptionally regulated.

FIG. 4.

Transcriptional activities of the nlpD and rpoS promoters. The activities were monitored by measuring the β-galactosidase activities from the transcriptional lacZ fusion vectors pRSNL (■) and pRSP70 (⧫), respectively, and are presented as percentages of the basal transcription level during early exponential phase. The dashed line represents the OD600 during growth. Each measurement was performed at least three times.

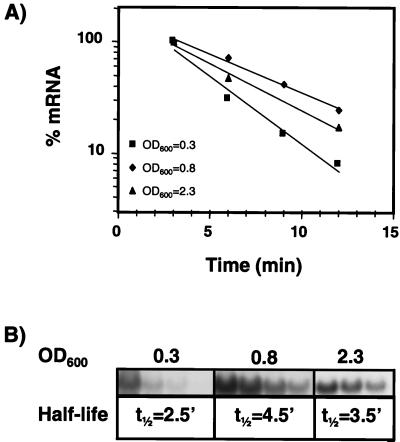

rpoS mRNA was stabilized during stationary phase.

Since the transcriptional activity at the rpoS promoter was not upregulated at an OD600 of 0.4, we postulated that the rise of rpoS mRNA was due to a decreased decay. To examine the stability of the rpoS mRNA during the growth curve, we determined the half-life of the mRNA at different growth phases. Rifampin, a potent inhibitor of RNA synthesis in bacterial cells, was added to cultures at OD600 of 0.3, 0.8, and 2.3. Total RNA was prepared at different time points after rifampin addition and analyzed by quantitative Northern blot analysis (Fig. 5). We found an approximately twofold increase in the stability of the rpoS mRNA between an OD600 of 0.3 and 0.8, with half-lives of 2.5 and 4.5 min, respectively. At an OD600 of 2.3, the half-life decreased to 3.5 min.

FIG. 5.

Stability of the rpoS mRNA main transcript along the growth curve. The half-life of the 1.6-kb rpoS mRNA was measured at OD600 0.3, 0.8, and 2.3. (A) Relative amounts of rpoS mRNA after addition of rifampin depicted on a semilogarithmic graph. (B) Calculated half-lives (in minutes) and a typical Northern blot. Each experiment was carried out two to four times.

DISCUSSION

In this work, we studied the regulation of rpoS transcription in S. dublin. We identified four distinct rpoS-specific transcripts 2.3, 1.6, 1.0, and 0.4 kb in size that were mapped within the nlpD-rpoS locus. Only the 2.3- and 1.6-kb messages encompassed the complete rpoS gene. The 2.3-kb transcript was a polycistronic message that included nlpD upstream of rpoS, whereas the 1.6-kb transcript contained a 566-bp upstream segment in addition to rpoS. The smaller 1.0- and 0.4-kb RNA fragments did not allow generation of a complete RpoS protein. They align with a part of the rpoS coding region and the untranslated rpoS upstream region, respectively.

The finding of 2.3- and 1.6-kb messages that allow transcription of a full-length RpoS indicates that rpoS transcription in S. dublin is controlled by two different promoter regions. Both transcript levels peak substantially during late exponential growth at an OD600 of 0.4 to 0.5 (Fig. 1B). This upregulation is accompanied by a significant increase in cellular RpoS concentrations, indicating that the increase of rpoS-specific mRNA available for translation is the pivotal regulatory event at this point of growth. After the peak at OD600 0.4 to 0.5, the mRNA levels of both 2.3- and 1.6-kb transcripts decreased continuously until late stationary phase. Although the courses of the net levels of the 2.3- and 1.6-kb mRNAs were very similar along the growth curve, we surprisingly found that the two promoters are regulated differently. Transcription from the promoter region upstream of nlpD was found to be growth regulated. In accordance with the course of the 2.3-kb mRNA, transcriptional activity increased about twofold during late exponential phase and then returned gradually to the baseline level (Fig. 4). Growth dependence was corroborated by the observation that in an rpoS mutant growth regulation was abolished, and this suggested further the presence of a positive autoregulation. In contrast, the transcriptional rate from the rpoS promoter producing the 1.6-kb transcript was found to be growth independent. A high and constant promoter activity was measured throughout the growth cycle, consistent with the finding of a transcriptional start that is preceded by a typical ς70 RNA polymerase-dependent promoter consensus sequence (Fig. 2B). Hence, the significant increase of the 1.6-kb mRNA levels in late exponential phase can be explained only by posttranscriptional regulation. We found a substantial rise in mRNA stability that occurred together with the sharp rise of mRNA, increasing the mRNA half-life from 2.5 to 4.5 min. The molecular mechanism of this increased stability is not known. Possibly the unusually long untranslated upstream region of the 1.6-kb transcript plays a significant role; however, experimental evidence for this is lacking.

Although the nlpD-rpoS nucleotide sequences of E. coli and S. dublin are very closely related, we discovered significant differences in rpoS regulation between the two species. First, the relative contributions of the 2.3- and 1.6-kb messages to rpoS expression differed significantly from the findings reported for E. coli. Whereas in E. coli transcription from the nlpD promoter contributes up to 40% to rpoS expression (20, 21), we found only a minor portion (10%) arising from the nlpD promoter in S. dublin (Fig. 1B). This lower activity might be explained by the finding that the −10 region of one of the two nlpD promoters in E. coli was virtually absent in S. dublin. Second, the rpoS promoter responsible for the 1.6-kb main message showed high transcriptional activity even during early exponential growth. In contrast to E. coli (20), no significant induction of the transcription rate was observed when the cells entered the stationary phase. Third, nlpD, which is known in E. coli to be a growth-independent regulated gene (21), was found to be induced significantly during transition into stationary growth in S. dublin. This might be due to the differences that we found in the sequence upstream of the translational start site. Fourth, the smaller 1.0- and 0.4-kb RNAs have not been described for E. coli. Their possible function for rpoS regulation in S. dublin remains unclear. It is conceivable that they represent stable degradation products of the 1.6-kb transcript from an endonucleolytic cleavage or are transcribed autonomously and function as regulatory RNA (27, 34).

Although E. coli and S. dublin are closely related species, they differ significantly in terms of pathogenicity and the ability to survive in specific hosts. Therefore, differences in regulation of rpoS expression are not unexpected, particularly since RpoS plays a significant role in the regulation of Salmonella virulence (6, 10, 12, 17). Our study emphasizes that based on homologous DNA sequences alone, we must not anticipate that even closely related species have identical regulatory pathways.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank P. Vermeij and M. Kertesz for their interest and critical reading of the manuscript. We thank T. Leisinger, in whose laboratories this work was carried out.

Financial support was provided by the Swiss National Research Foundation (grant 32-039342.93 to M.K.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Amann E, Ochs B, Abel K-J. Tightly regulated tac promoter vectors useful for the expression of unfused and fused proteins in Escherichia coli. Gene. 1988;69:301–315. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90440-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bearson S M D, Benjamin W H, Jr, Swords W E, Foster J W. Acid shock induction of RpoS is mediated by the mouse virulence gene mviA of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2572–2579. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.9.2572-2579.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bethesda Research Laboratories. E. coli TB1 host for pUC plasmids. Focus. 1984;6:4–7. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown L, Elliott T. Efficient translation of the RpoS sigma factor in Salmonella typhimurium requires host factor I, an RNA-binding protein encoded by the hfq gene. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3763–3770. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.13.3763-3770.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown L, Elliott T. Mutations that increase expression of the rpoS gene and decrease its dependence on hfq function in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:656–662. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.3.656-662.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen C-Y, Buchmeier N A, Libby S, Fang F C, Krause M, Guiney D G. Central regulatory role for the RpoS sigma factor in expression of Salmonella dublin plasmid virulence genes. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5303–5309. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.18.5303-5309.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chikami G K, Fierer J, Guiney D G. Plasmid-mediated virulence in Salmonella dublin demonstrated by use of a Tn5-oriT construct. Infect Immun. 1985;50:420–424. doi: 10.1128/iai.50.2.420-424.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Gedaily A. Regulation and subcellular location of the plasmid encoded virulence (Spv) proteins in wild-type Salmonella dublin. Ph.D. thesis. Zurich, Switzerland: University of Zurich; 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fang F C, Krause M, Roudier C, Guiney D G. Growth regulation of a Salmonella plasmid gene essential for virulence. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:6783–6789. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.21.6783-6789.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fang F C, Libby S J, Buchmeier N A, Loewen P C, Switala J, Harwood J, Guiney D G. The alternative ς factor KatF (RpoS) regulates Salmonella virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:11978–11982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.11978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fierer J, Fleming W. Distinctive biochemical features of Salmonella dublin isolated in California. J Clin Microbiol. 1983;17:552–554. doi: 10.1128/jcm.17.3.552-554.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heiskanen P, Taira S, Rhen M. Role of rpoS in the regulation of Salmonella plasmid virulence (spv) genes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;123:125–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Helmann J D, Chamberlin M J. Structure and function of bacterial sigma factors. Annu Rev Biochem. 1988;57:839–872. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.57.070188.004203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hengge-Aronis R. Back to log phase: ςS as a global regulator in the osmotic control of gene expression in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:887–893. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.511405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huisman G W, Kolter R. Sensing starvation: a homoserine lactone-dependent signaling pathway in Escherichia coli. Science. 1994;265:537–539. doi: 10.1126/science.7545940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ichikawa J K, Li C, Fu J, Clarke S. A gene at 59 minutes on the Escherichia coli chromosome encodes a lipoprotein with unusual amino acid repeat sequences. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1630–1638. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.6.1630-1638.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kowarz L, Coynault C, Robbe-Saule V, Norel F. The Salmonella typhimurium katF (rpoS) gene: cloning, nucleotide sequence, and regulation of spvR and spvABCD virulence plasmid genes. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6852–6860. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.22.6852-6860.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krause M, Fang F C, Guiney D G. Regulation of plasmid virulence gene expression in Salmonella dublin involves an unusual operon structure. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4482–4489. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.13.4482-4489.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krause M, Fang F C, El-Gedaily A, Libby S, Guiney D G. Mutational analysis of SpvR binding to DNA in the regulation of the Salmonella plasmid virulence operon. Plasmid. 1995;34:37–47. doi: 10.1006/plas.1995.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lange R, Fischer D, Hengge-Aronis R. Identification of transcriptional start sites and the role of ppGpp in the expression of rpoS, the structural gene for the ς38 subunit of RNA polymerase in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4676–4680. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.16.4676-4680.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lange R, Hengge-Aronis R. The nlpD gene is located in an operon with rpoS on the Escherichia coli chromosome and encodes a novel lipoprotein with a potential function in cell wall formation. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:733–743. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lange R, Hengge-Aronis R. The cellular concentration of the ς38 subunit of RNA-polymerase in Escherichia coli is controlled at the levels of transcription, translation and protein stability. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1600–1612. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.13.1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laoide B M, Ullmann A. Virulence dependent and independent regulation of the Bordetella pertussis cya operon. EMBO J. 1990;9:999–1005. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08202.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee I, Lin J, Hall H K, Bearson B, Foster J W. The stationary-phase sigma factor ςS (RpoS) is required for a sustained acid tolerance response in virulent Salmonella typhimurium. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:155–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17010155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loewen P C, Hengge-Aronis R. The role of the sigma factor ςS (KatF) in bacterial global regulation. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1994;48:53–80. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.000413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mudd E A, Krisch H M, Higgins C F. RNase E, an endoribonuclease, has a general role in the chemical decay of Escherichia coli mRNA: evidence that rne and ams are the same genetic locus. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:2127–2135. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muffler A, Fischer D, Hengge-Aronis R. The RNA-binding protein HF-I, known as a host factor for phage Qβ RNA replication, is essential for rpoS translation in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1143–1151. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.9.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muffler A, Fischer D, Altuvia S, Storz G, Hengge-Aronis R. The response regulator RssB controls stability of the ςS subunit of RNA polymerase in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 1996;15:1333–1339. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mulvey M R, Loewen P C. Nucleotide sequence of katF of Escherichia coli suggests KatF is a novel ς transcription factor. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:9979–9991. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.23.9979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prince R W, Xu Y, Libby S J, Fang F C. Cloning and sequencing of the gene encoding the RpoS (KatF) ς factor from Salmonella typhimurium 14028s. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1219:198–200. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(94)90271-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simons R W, Houman F, Kleckner N. Improved single and multicopy lac-based cloning vectors for protein and operon fusions. Gene. 1987;53:85–96. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90095-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sledjeski D D, Gupta A, Gottesman S. The small RNA, DsrA, is essential for the low temperature expression of RpoS during exponential growth in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 1996;15:3993–4000. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takayanagi Y, Tanaka K, Takahashi H. Structure of the 5′ upstream region and the regulation of the rpoS gene of Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;243:525–531. doi: 10.1007/BF00284200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zgurskaya H I, Keyhan M, Matin A. The ςS level in starving Escherichia coli cells increases solely as a result of its increased stability, despite decreased synthesis. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:643–651. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3961742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zieg J, Maples V F, Kushner S R. Recombination levels of Escherichia coli K-12 mutants deficient in various replication, recombination, or repair genes. J Bacteriol. 1978;134:958–966. doi: 10.1128/jb.134.3.958-966.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]