Abstract

Background:

Duodenal and pyloric web (DW/PW) can present at any age, symptoms depend upon the location of the web along with the presence and size of the opening in the web. The surgical management is not straightforward always. Here, in this study, we aim to assess clinical characteristics, management, and outcome of children with DW/PW.

Materials and Methodology:

This was a retrospective study from 2005 to 2019, and data were collected from record registers. All children of DW/PW presented between this duration were included in this study.

Results:

A total of 45 patients (age range = 1 day to 11 years) included in the study, 40 had DW while 5 had PW. Seven patients were diagnosed antenatally and 20 patients had associated congenital anomalies. Most patients presented with vomiting either bilious or nonbilious. Plain X-ray was sufficient for the diagnosis in 60% of patients, the rest diagnosed on contrast study. The web excision and pyloroplasty were done for PW. The web excision and Heineke-Mikulicz type enteroplasty was the preferred surgery for DW but some patients were required Kimura's duodeno-duodenostomy. For postoperative nutrition, enteral feeding was established through the placement of a feeding tube beyond anastomosis. Ten patients died due to septicemia and associated anomalies. Four patients had a minor leak which was managed by conservative means. Four patients required redo surgery, adhesive obstruction was the most common indication. During follow-up, all 35 patients were doing well with no major complaints.

Conclusion:

DW/PW has different presentations as compared to other intestinal atresia and can present at any age. A contrast study confirms the diagnosis when plain X-ray is inconclusive. Associated anomalies and septicemia are the poor prognostic indicators. Postoperative enteral feeding helps in maintaining adequate nutrition and improves the outcome even in children with a minor anastomotic leak.

KEYWORDS: Congenital web, duodenal atresia, duodenal web, intestinal atresia, pyloric atresia, pyloric web

INTRODUCTION

Intestinal atresias are divided into three types, depending upon the nature of the defect. In Type I atresia, there is no apparent discontinuity of the bowel wall and it could be because of stenosis, complete web, web with a central hole, or a windsock type of deformity. The proposed embryo-pathogenesis of duodenal and pyloric atresia (DA/PA) is an abnormality in recanalization which is different from other intestinal atresia where the proposed etiology is a vascular insult.[1,2] The timing of presentation varied according to the degree of obstruction, can present during the newborn period if it is completely obstructed, or can present later in life if the web contains a central opening and creates a partial obstruction.[3] Here, we are discussing the different presentations of the DW/(pyloric web [PW]) along with its management and review of pertinent literature.

MATERIALS AND METHODOLOGY

It was a retrospective study from January 2005 to December 2019; data were collected from record registers maintained by the department. Ethical clearance was taken from the Institutional Ethics Committee (NK/6550/474). All children of DW/PW presented between this duration were included in this study. Patients with incomplete data not underwent surgery and more than 12 years old were not included in the study.

Neonates with complaints of vomiting (bilious/nonbilious) and feed intolerance were presented in the emergency department. After clinical examination and stabilization, an X-ray abdomen was performed along with routine blood investigations. If X-ray was suggestive of a single- or double-bubble sign with absent/paucity of gas in the distal bowel, the child was admitted to a pediatric surgical newborn intensive care unit with a provisional diagnosis of DA/PA.

In cases, where patients were presented late or X-ray was inconclusive, (upper gastrointestinal [UGI]) contrast study was done to confirm the diagnosis. Once the child became hemodynamically stable, the child was taken up for exploratory laparotomy. The abdomen was opened through the right upper transverse incision. In cases of obvious discrepancy between proximal and distal bowel or clear indentation of the web from outside, the bowel was opened vertically at the level of the web which includes 2 cm proximal and 2 cm distal bowel. The web was excised from the lateral, anterior, and posterior side, the medial part remained untouched, particularly in cases of DW at the second part to avoid injury to the ampulla, and the bowel was closed transversely. In some cases, Kimura's diamond-shaped duodeno-duodenostomy was done. In cases where the level of obstruction was not visible from outside, a small gastrotomy was done and Foley's catheter was pushed through it toward the duodenojejunal junction, and then inflated with 2 ml saline and retracted back to know the level of obstruction. For postoperative feeding either a nasojejunal (N-J) tube was placed or feeding jejunostomy (F-J), which could be done separately from jejunal opening or as a trans-gastric trans-anastomotic (TGFJ) F-J.

Postoperatively, usually from day 2 feeding was started from N-J or F-J tube, and gradually it was increased according to nasogastric (N-G) aspirate quantity and nature, abdominal distension, and stool pattern. Once N-G aspirate became gastric in nature or minimal in quantity, the child was started on N-G feed and if tolerated then shifted to oral feeds. The child was discharged once tolerated full oral feeds. During follow-up along with routine evaluation, the child was assessed for feed intolerance, vomiting, and weight gain as well as evaluated for associated anomalies.

RESULTS

A total of 196 patients were enrolled in the study, including 103 DA, 84 malrotations, and 9 cases of PA. A total of 45 patients were fulfilled the inclusion criteria. The epidemiological characteristics, the associated anomalies, and the clinical presentation were as presented in Tables 1-3, respectively. The operative finding, surgical procedures, complications, and outcomes are shown in Table 4. The mean time taken to achieve full oral feed was 9 days (range 7–12 days) in survivors, and the mean hospital stay was 13 days (range 9–18 days). The mean follow-up duration was 2 years (range 6 months to 5 years) and during follow-up, most of the patients were doing well, tolerating feed, gaining weight, and without any major issues related to PW/DW surgery.

Table 1.

Epidemiological characteristics of children with duodenal and pyloric web

| Level of web | Age range | Median age/mean age | Male:female ratio | Associated. anomalies (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DW-1 (10) | 2 days-10 months | 5 days/36 days | 7:3 | 7 |

| DW-2 (22) (including WS=2) | 1 day-11 years | 13 days/9 months | 8:3 | 9 |

| DW-3 (5) | 1 day-1 year | 10 days/65 days | 2:3 | 2 |

| DW-4 (3) | 1 day-1 year | 8 days/17 days | 2:1 | 0 |

| PW (5) | 2 days-4 months | 8 days/29 days | 3:2 | 2 |

DW: Duodenal web 1,2,3,4: parts of the duodenum, WS: Windsock type of web, PW: Pyloric web

Table 3.

Clinical presentation of children with duodenal and pyloric web

| Diagnosis | AD | BV | NBV | Feed intolerance | FTT | Other | Diagnostic investigation | Previous surgery intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DW-1 (10) | 2 | - | 9 | 1 | ARM+excessive salivation Respiratory distress Septicemia |

X-ray (9) Contrast study (1) |

HDSC+ esophagostomy+ gastrostomy | |

| DW 2 (22) | 2 | 12 | 10 | 5 | 3 | Excessive salivation Septicemia ARM (2) |

Xray (10) Contrast study (11) Contrast study+UGIE (1) |

UGIE+multiple endoscopic dilatations |

| DW 3 (5) | 2 | 5 | - | 2 | 1 | Excessive salivation Respiratory distress |

X-ray (3) Contrast study (2) |

Ladd’s procedure |

| DW 4 (3) | -- | 3 | - | X-ray (2) Contrast study (1) |

||||

| PW (5) | 1 | - | 5 | 1 | 1 | X-ray (4) Contrast study (1) |

DW: Duodenal web 1,2,3,4: Parts of the duodenum, PW: Pyloric web, AD: antenatally diagnosed, BV: Bilious vomiting, NBV: Nonbilious vomiting, FTT=Failure to thrive, ARM: Anorectal malformation, HDSC: High divided sigmoid colostomy, UGIE: Upper gastro intestinal endoscopy

Table 4.

Surgical procedure and follow up of children with duodenal and pyloric web

| Diagnosis | Surgical procedure | Additional surgery | For postoperative feeding | Redo surgery | Mortality/LAMA | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DW 1 | WE+duodenoplasty (9) Kimura D-D (1) |

Ladd’s procedure (1) | N-J (5) TGFJ (3) FJ (1) Gastrostomy (1) |

Adhesive obstruction=1 | DS+CHD (2) Sepsis (1) |

GER (1) |

| DW 2 | Duodenoplasty (17) Kimura D-D (5) |

Ladd’s procedure (3) TEF repair (1) |

N-J (13) TGFJ (5) FJ (4) |

Adhesive obstruction=1 Perforation due to FJ tip=1 |

Sepsis (3) | Poor weight gain (2) |

| DW 3 | Duodenoplasty=3 Kimura D-D=1 D-Janastomosis=1 |

TEF repair (1) | N-J (3) TGFJ (1) FJ (1) |

Residual web required revision | Sepsis (1) | Nil |

| DW 4 | Duodenoplasty=3 | Nil | N-J (3) | - | Sepsis (1) | Nil |

| PW | WE+pyloroplasty=5 | J-J for atresia | N-J (4) TGFJ (1) |

- | Sepsis (1) LAMA=1 |

GER (1) |

DW: Duodenal web 1,2,3,4: Parts of the duodenum, PW: Pyloric Web, WE: Web excision, D-D: Duodenoduodenostomy, D-J: Duodeno-jejunal anastomosis, TEF: Tracheoesophageal fistula, J-J: Jejuno-jejunalanastomosis, N-J: Naso-jejunal tube, TGFJ: Trans gastric feeding jejunostomy, FJ: Feeding jejunostomy, LAMA: Leave against medical advice, GER: Gastroesophageal reflux, DS: Down syndrome, CHD: Congenital heart disease

Table 2.

Associated anomalies in duodenal and pyloric web

| Anomalies (number of patients=20) | Type of obstruction |

|---|---|

| Renal duplication (1) | DW |

| Malrotation (6) | DW |

| ARM (3) | DW |

| EATEF (2) | DW |

| Annular pancreas (2) | DW |

| Pure EA (1) | DW |

| Cardiac anomaly (6) | DW (5) |

| PW (1) | |

| Down syndrome (3) | DW |

| MIA (2) | DW (1) |

| PW (1) |

DW: Duodenal web, PW: Pyloric web, ARM: Anorectal malformation, EATEF: Esophageal atresia trachea-esophageal fistula, EA: Esophageal atresia, MIA: Multiple intestinal atresia

DISCUSSION

Intestinal obstruction is a common pediatric/neonatal surgical emergency. The incidence of intestinal atresia is approximately 1:4000 live births.[4] Duodenal web (DW) is uncommon, the second part of the duodenum is the most common location (85%–90% of cases), followed by the third and fourth parts of the duodenum.[5,6] PA constitutes approximately 1% of all intestinal atresias, and its incidence is approximately 1 in 100,000. PA varies from a membranous diaphragm to a complete disjunction at the pyloric level.[7] In our study, we evaluated a significant number of patients as our institute serves the 32 million population of north India and is the only tertiary referral institute for pediatric surgery in the region with a birth rate of 16.5/1000 population.[8]

The PA/DA can be diagnosed antenatally (AD) on ultrasonography (USG) with the dilated stomach, single/double bubble appearance, and polyhydramnios.[9,10] In our study, seven patients were AD.

The age of presentation for congenital DW/PW varies widely and depends upon the presence of an aperture in the web and its size. Rarely, associated anomalies take precedence or attention leads to delay in the diagnosis of DW/PW. In our study, one child was operated on for pure esophageal atresia (no gas shadow in the abdomen) so underwent esophagostomy and gastrostomy. During the postoperative period, the child was not tolerating feed then a contrast study was done which was suggestive of duodenal obstruction. Another child was operated on for malrotation but postoperatively did not tolerate feed. So a UGI contrast study was done and duodenal obstruction was diagnosed. In both the above-mentioned cases, DW could have been diagnosed at first surgery if the bowel was checked for luminal patency; routinely we do examine the whole bowel for continuity but luminal patency we check only if there is suspicion of web or presence of another atresia. Interestingly, one child was referred at 2 years of age from pediatric gastroenterology after multiple attempts of endoscopic dilatation of the DW for 1 year.

Multiple associated disorders such as Down syndrome, cardiac anomalies, malrotation of the gut, vertebral defect, and renal anomalies have been described with DW/PW.[11] In our study, malrotation and cardiac anomalies were the most common, around 50% of patients had one or more associated anomalies. However, this number may be higher as all patients did not undergo 2D echo, USG abdomen/KUB, etc.

The usual presentation in the new-born period is vomiting and feed intolerance. Web at the pylorus and DW 1 (web at the first part of the duodenum) always present with nonbilious vomiting (NBV) while DW 3 and DW 4 (web at the third part and the fourth part of the duodenum) always present with bilious vomiting (BV). Only the DW 2 (web at the second part of the duodenum) can present with either BV or NBV depending on whether the web is preampullary or postampullary. In our study, out of 22 patients of DW 2 (including 2 windsock type of web), 12 and 10 presented with BV and NBV, respectively.

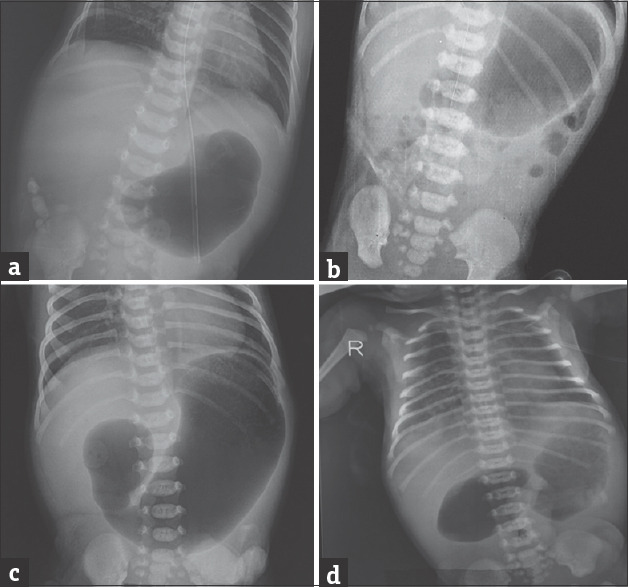

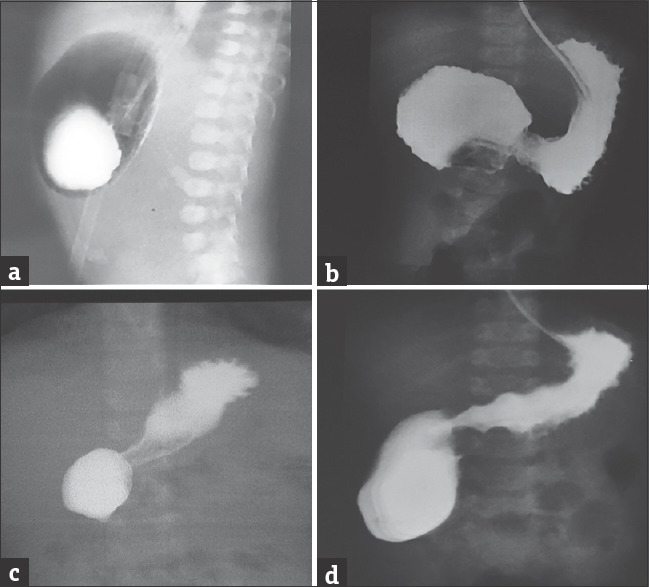

Often, the diagnosis can be made by plain abdominal X-ray, especially when there is a complete web, i.e.without a central hole, it will show a single bubble or double bubble for PW and DW, respectively [Figure 1]. In cases of PW/DW with a central hole along with dilated stomach/duodenum, the distal intestine also shows some gas pattern [Figure 1]. In the remaining cases, the UGI contrast study is diagnostic of the web. In our study, more than 60% of patients diagnosed on plain X-ray abdomen, the rest required contrast study [Figure 2].

Figure 1.

Showing plain X-ray abdomen with a single large bubble suggestive of pyloric atresia (a and b), distal gas pattern (b) indicates web with hole and double bubble sign (c and d) in cases of duodenal atresia

Figure 2.

Showing oral contrast study in case of pyloric atresia (a), atresia in the first part of the duodenum (b), and web with a central hole in the second part (c and d) of the duodenum as suggested by the distal gas pattern

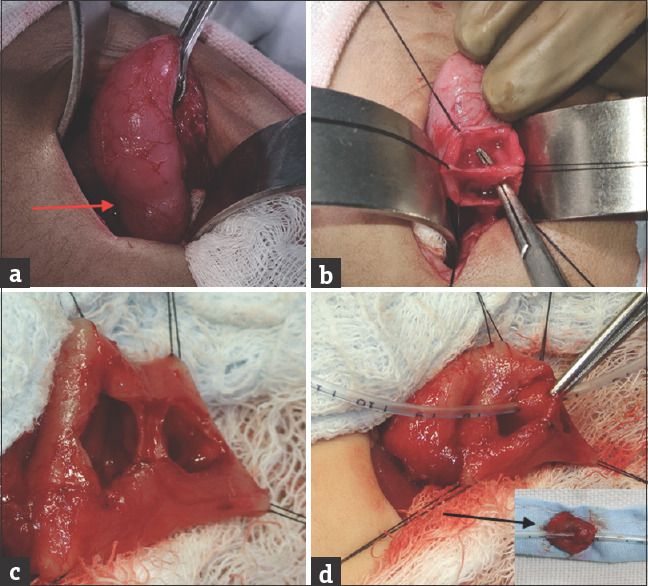

The surgical procedure is not the same for all types of intestinal atresia and depends upon intraoperative findings, i.e., the visible discrepancy between proximal and distal bowel, severity of discrepancy, visible indentation of the web [Figure 3], need of gastrotomy to locate the level of obstruction, and associated abnormalities like the annular pancreas and multiple intestinal atresias (MIAs). Our preferred approach was lateral longitudinal enterotomy and web excision [Figure 3] it prevents injury to the medial wall structure, especially in DW2, requires the closure of the anterior wall only and avoids circumferential suturing of the bowel so less chance of a leak, and lastly needs less operative time. In cases of high discrepancy between proximal dilated and distal narrow segments or associated with the annular pancreas, Kimura's diamond-shaped duodeno-duodenostomy was the procedure of choice.

Figure 3.

Showing intraoperative image of indentation at the level of obstruction (red arrow) in case of the duodenal web (a) at the second part, a vertical incision, and duodenotomy with delineation of web and its central hole (b). Duodenal web appearance at the first part (c) with its central hole (d) and its complete excision (inset, black arrow)

Postoperative nutrition is always an issue for these babies. The dilated proximal segment can take a few days to weeks for the return of adequate peristalsis and so till then oral feed cannot be given. In this time duration, either total parenteral nutrition or enteral nutrition beyond anastomosis should be given. The TPN is costly and with its complications. Hence, in our patients, we always provided enteral nutrition through a feeding tube, which bypasses the anastomosis either in the form of N-J, F-J, or TGFJ.

Our preferred approach was the placement of the N-J tube and its tip was kept at least 20 cm beyond the DJ flexure. In cases where we had done gastrotomy to diagnose the level of obstruction through Foley's catheter, we placed TGFJ through the same gastrotomy site. In cases where more intestinal anastomosis was done distally or it was not possible to place IFT well beyond the anastomosis, separate feeding jejunostomy (F-J) was done.

In our study, four patients had a minor anastomotic leak which was managed by glove drain placement (if not placed intraoperatively), NG aspiration, and continuation of enteral feed. All patients responded well to conservative management.

The mortality was 22% in our study and most of our patients (80%) had died of septicemia. Sarin et al. also reported 4 mortality in 18 patients of the DW.[11] Ilce et al. described 15 patients with PA, out of which 9 were web, and mortality for the PW subgroup was 55%.[7] In our study, septicemia occurred in preterm babies, patients with associated congenital anomalies (like TEF and ARM), and in patients who underwent multiple surgeries. Some patients had septicemia at the time of presentation and others were acquired it during their prolonged hospital stay. Two patients, one with Down syndrome and another with Ebstein anomaly died due to cardiac reasons. One patient of PW with MIA underwent pyloroplasty and intestinal atresia repair with an ileostomy. The postoperative period was stormy and parents refused to continue the further treatment.

During follow-up along with DW/PW-related issues, associated malformations should be managed properly. In our study, some patients required additional surgery for associated malformation like ureteric reimplantation in a renal duplex system with VUR, esophageal substitution by gastric tube in case of pure esophageal atresia, and ano-rectoplasty for ARM.

CONCLUSION

Clinical characteristics of DW/PW are varied as well as different from other types of intestinal atresia. UGI contrast study confirms the diagnosis where plain X-ray is uncertain. Associated anomalies and septicemia are the major poor prognostic indicators. Continuation of postoperative enteral feeding improves the outcome even in children with a minor anastomotic leak.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Grosfeld JL, Rescorla FJ. Duodenal atresia and stenosis. In: Gray SW, Skandalakis JE, editors. Embryology for Surgeons: The Embryological Basis for the Treatment of Congenital Defects. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1986. pp. 33–8. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bawazir OA, Al-Salem AH. Congenital pyloric atresia: Clinical features, diagnosis, associated anomalies, management and outcome. Ann Pediatr Surg. 2017;13:188–93. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitul AR. Congenital neonatal intestinal obstruction. J Neonatal Surg. 2016;5:41. doi: 10.21699/jns.v5i4.472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Juang D, Snyder CL. Neonatal bowel obstruction. Surg Clin North Am. 2012;92:685. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.AlGhannam R, Yousef YA. Delayed presentation of a duodenal web. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep. 2015;12:530–3. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beeks A, Gosche J, Giles H, Nowicki M. Endoscopic dilation and partial resection of a duodenal web in an infant. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48:378–81. doi: 10.1097/mpg.0b013e31818c600f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ilce Z, Erdogan E, Kara C, Celayir S, Sarimurat N, Senyüz OF, et al. Pyloric atresia: 15-year review from a single institution. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:1581–4. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(03)00565-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. [Last accessed on 2021 Mar 11]. Available from: http://niti.gov.in/content/birth-rate .

- 9.Pariente G, Landau D, Aviram M, Hershkovitz R. Prenatal diagnosis of a rare sonographic appearance of duodenal atresia. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31:1829–33. doi: 10.7863/jum.2012.31.11.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu DC, Voss SD, Javid PJ, Jennings RW, Weldon CB. In utero diagnosis of congenital pyloric atresia in a single twin using MRI and ultrasound. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44:e21–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarin YK, Sharma A, Sinha S, Deshpande VP. Duodenal webs: An experience with 18 patients. J Neonatal Surg. 2012;1:20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]