Abstract

Aim and Objectives:

The aim of the study is to compare the outcome in children born with long-gap esophageal atresia following reverse gastric tube esophagoplasty (RGTE) with or without the lower esophageal stump as a “fundoplication” wrap.

Materials and Methods:

All children who underwent RGTE between 2008 and 2018 were retrospectively analyzed. Patients in whom the lower esophagus (LE) had been excised as is done routinely in RGTE (Group 1) were compared with those where the LE was wrapped partially or completely around the intraabdominal neo-esophagus (Group 2). Both vagal nerves were preserved to the extent possible. Complications and final outcome, including weight and height centiles were assessed. Follow-up upper gastrointestinal contrast study and reflux scans were studied.

Results:

Nineteen patients (mean age: 15.78 ± 5.02 months [range 10–30 months] at RGTE) were studied; nine in Group 1 and ten in Group 2. Both groups had similar early postoperative complications as well as the requirement of dilatation for anastomotic stricture. Dysphagia for solids was noticed in two patients with complete lower esophageal wrap (n = 4), one requiring removal. More patients in Group 2 had absent reflux (n = 7) compared to Group 1 (n = 3) (P = 0.118). At a mean follow-up period of 45.75 ± 18.77 months (14–84 months), Group 2 children reached better height and weight percentiles compared to Group 1.

Conclusion:

We have described a novel method of using the LE as a “fundoplication” wrap following RGTE. Vagi should be preserved. Those with complete esophageal wrap may develop dysphagia to solids and this is, therefore, not recommended. Lower esophageal wrap patients appeared to have a better outcome in terms of growth and less reflux.

KEYWORDS: Esophageal atresia, esophagoplasty, gastroesophageal reflux, lower esophagus, reverse gastric tube

INTRODUCTION

Many techniques are employed for esophageal replacement after an initial esophagostomy and gastrostomy for pure esophageal atresia (EA) or long gap EA. Reverse gastric tube esophagoplasty (RGTE) is a popular method as it retains part of the stomach for reservoir function and has been shown to have good long-term results.[1,2,3] However, a careful search of the literature showed that no specific surgical technique has been described to reduce regurgitation of feeds or gastroesophageal reflux (GER) in these patients. The remnant stomach is small and utilizing it for fundoplication is not always feasible. The lower esophagus (LE) is usually excised. In this study, we have used the remnant esophageal stump for fundoplication in some patients and compared the results with those who had a conventional RGTE. Any reduction in regurgitation of feeds, acid reflux, and respiratory complications were studied. To the best of our knowledge, this technique has not been described in the literature before.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a retrospective study conducted in a pediatric surgical tertiary care centre on patients who had undergone RGTE between 2008 and 2018 after obtaining Institute ethical clearance (NK/4584/RS/500). We used the LE as a ‘fundoplication’ wrap in the second half of the study if its length was at least 3 cm. We compared the results of patients who underwent conventional RGTE, i.e., with excision of LE (Group 1) with those who underwent RGTE with lower esophageal wrap (Group 2). Patients with pure EA, long gap EA with tracheo-esophageal fistula (EATEF), and EATEF with major leak who had undergone diversion in the neonatal period, i.e., cervical esophagostomy and gastrostomy were included in the study. Patients who underwent fundal tube esophagoplasty or esophageal replacement with colon and those requiring esophagoplasty for corrosive stricture were excluded from the study. In the neonatal period, after the initial procedure, early feeding through the gastrostomy tube and sham feeding were started before discharge. A water-soluble contrast study was performed through the gastrostomy tube to assess the stomach size after 6 months of age. Complete hemogram, renal function tests, plain radiograph of the chest, ultrasonography of the kidney, ureter, and bladder and echocardiography were performed in all patients. Written informed consent was obtained from parents before RGTE.

Operative procedure

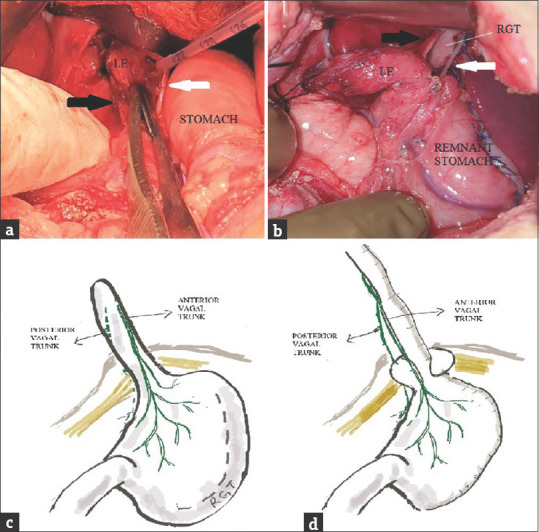

The RGTE was performed as described in standard textbooks. Hand sewn polyglactin sutures were inserted in two layers for the creation of tube and closure of the remaining stomach. During mobilization of the LE, the anterior and posterior vagal trunks were identified at the hiatus. They were lifted off the LE but maintained continuity distally as they entered the surface of the stomach along the lesser curvature [Figure 1]. By blind finger dissection, posterior mediastinal tunnel was created and the gastric tube pulled through. In a two-staged procedure esophageal anastomosis was performed after 2–3 months. The preference was to do a primary anastomosis.

Figure 1.

Intraoperative photograph showing intact anterior (white arrow) and posterior (black arrow) vagal trunks (a): At the time of initial dissection in the esophageal hiatus and their relationship to the lower esophagus and (b): After tunneling of reverse gastric tube through the esophageal hiatus. Diagram showing anatomical location of vagal nerves (c): Before dissection and (d): After tunneling of reverse gastric tube through the hiatus and placement of lower esophageal stump wrap

Depending on its length, the LE was wrapped partially or completely around the intra-abdominal gastric tube just below the Hiatus and fixed with interrupted seromuscular sutures. An appropriate size nasogastric tube was inserted and the hiatus narrowed with interrupted silk sutures. The esophageal wrap was also sutured to the crura and a feeding jejunostomy created. No drains were placed in the abdomen.

In single-stage procedure, it was preferred to electively ventilate for a few days. A chest radiograph was performed postoperatively to rule out pneumothorax or drainable collection. Patients received enteral feeds through the jejunostomy tube from the 2nd postoperative day. The nasogastric tube and neck drain were removed depending upon the output. If there was no salivary leak in the neck and the neo-esophagus was found to be normal on contrast study, oral feeds were commenced. These were gradually increased in amount with the advice to give small frequent feeds in the initial postoperative months. All patients were kept indefinitely on proton pump inhibitors and advised to sleep in a propped-up position.

An upper gastrointestinal tract study was done in the follow-up to assess anastomotic stricture, gastric tube stricture, diverticulum, remnant stomach size, and its drainage. Reflux scan using 99mTc labeled sulfur colloid was also performed at least 1 year after the procedure.

Age at surgery, intraoperative and postoperative complications, the requirement of postoperative ventilation, time to full oral feeds, need for esophageal dilatation, and complaints of the patients in the last follow-up at least 1 year after surgery were compared between the two groups. Height and weight measured at the last follow-up were converted to percentiles and were calculated as per current recommendations of the Indian Academy of Pediatrics for boys and girls above and below 5 years of age.

Statistical analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA, version 17.0 for Windows) was used. Medians and interquartile ranges were used to summarize ordinal scales and variables with nonnormal distributions. Means and standard deviations or medians and interquartile ranges were used to summarize continuous variables. Comparison of quantitative variables between the study groups was done using the Mann–Whitney U-test for independent samples. For comparing categorical data, the Pearson Chi-square test was performed. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The demographic details of the two groups are shown in Table 1 and were comparable. Procedure details at the time of RGTE and early interventions are mentioned in Table 2 with no statistically significant difference. During RGTE, dense adhesions were noted between the anterior abdominal wall, stomach, and liver in two patients in Group 1 and 4 in Group 2.

Table 1.

Demographic data of children with esophageal atresia who underwent reverse gastric tube esophagoplasty

| Procedure | Group 1 | Group 2 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 9 | 10 | 19 |

| Male: female | 9:0 | 3:7 | 2.2:1 |

| PEA | 4 | 7 | 11 |

| LG-EATEF | 4 | 2 | 8 |

| Age (months) at the time of surgery, mean±SD (range) (median) | 15±4.33 (11-23) (12) | 16.5±5.72 (10-30) (14) | 15.78±5.02 (10-30) (14) |

| Weight (kg) at the time of surgery, mean±SD (range) | 9.7±1.63 (7.4-12) | 9.95±1.12 (9-12.4) | 9.83±1.354 (7.4-12.4) |

| Associated anomalies | |||

| Cardiac | PFO (n=1) | PFO, L-R shunt (n=1) Large PDA, VSD, operated (n=2) |

3 |

| Genitourinary | Unilateral UDT with bilateral hernia (n=1) | Bilateral Grade V VUR (n=1) | 2 |

| Head | Craniosynostosis (with subglottic stenosis) (n=1) | Nil | 1 |

L-R: Left to right, PDA: Patent ductus arteriosus, PEA: Pure esophageal atresia, PFO: Patent foramen ovale, SD: Standard deviation, UDT: Undescended testes, VSD: Ventricular septal defect, VUR: Vesico ureteric reflux, LG-EATEF: Long gap esophageal atresia with tracheo-esophageal fistula

Table 2.

Procedure details and early postoperative complications in Group 1 and 2 patients

| Procedure | Group 1 (n=9) | Group 2 (n=10) | Total (n=19) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stages | |||

| Single stage | 7 | 9 | 16 |

| Two-stage | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Route taken by tube | |||

| Retrosternal | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Trans-hiatal | 7 | 9 | 16 |

| Length of gastric tube created in cm (mean) | 13-15 (13.4) | 12-16 (14.75) | 12-16 (14.2) |

| Length of lower esophagus in cm (mean) | 0.5-6 (3.2) | 3-6 (4.3) | 1-6 (4) |

| Early postoperative complications | |||

| Thoracic leak requiring chest tube drainage | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Leak of saliva from neck drain | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| Dysphagia | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Bradycardia/tachycardia/arrhythmia/hypertension | 0/3/0/0# | 2/5/1/1* | 10* |

#Data insufficient, *Some patients had >1 problem

The lower esophageal stump could be easily mobilized into the abdomen in all the patients. Depending on the length of the LE, a complete or partial wrap was performed over the RGTE just below the crura in Group 2 patients.

Three patients underwent two-stage procedure, with closure of esophageal ends being done 2–9 months (median 5 months) after the first surgery [Table 2]. In Group 1, after the first stage, one had significant bleed requiring more than one transfusion on day 6 followed by reflux of feed from the upper end of the neo esophagus from day 13. In the second patient, the upper end of the neo esophagus had completely stenosed and required mobilization before closure during the second stage. In single-stage procedure in Group 1, one patient required additional right-sided thoracotomy for excision of remnant esophageal tract.

In patients who underwent 2 stage procedure, all could be extubated after surgery whereas in single-stage, only 3 of 7 in Group 1 and 4 of 9 in Group 2 were extubated. The remaining were extubated between the 2nd and 5th postoperative day.

In Group 2, one patient developed bradycardia of 54/min on day 3 and on further investigation was found to have multifocal atrial tachycardia and partial atrioventricular block. He was otherwise hemodynamically stable and had been extubated on day 2. Echo was found normal and heart rate normalized without medication by day 6. This child is now 9-years-old with no complaints in the interim period. Another infant had bradycardia on table during tunneling and also in the immediate 2 days after surgery which spontaneously resolved. Five patients had tachycardia of 120–170 min for 7–10 days postoperatively. All these patients also had fever and/or respiratory complaints during this period, two requiring chest tube insertion. Among them, one had transient raised blood pressure on day 5 which was managed conservatively. Another child had prolonged QT interval requiring correction of mild hypokalemia. No specific medication was advised as the child was stable. He had a history of prolonged ventilation, oxygen dependency, and seizures during the first neonatal admission for gastrostomy and esophagostomy. Subsequently, a large patent ductus arteriosus was closed during the same admission. He is currently 6-years-old and doing well.

Postoperative salivary leak from neck drain was noted in three children in Group 1 lasting 10–14 days. One child without any salivary leak had early dysphagia requiring neck exploration and dilatation of anastomotic stricture 1 month after surgery. In Group 2, four patients had salivary leak lasting for 4 days to 3 weeks. Glycopyrrolate at 0.2 mg tid was given in two patients in Group 2 and was found to be useful in partially reducing the leak.

All patients were started on jejunostomy feeds 2–3 days after surgery. Patients who had undergone two-stage procedure, tended to accept semi-solids, and solids within 7–10 days of closure of esophageal ends whereas those after single-stage surgery were mostly on oral liquid diet with some jejunostomy feed supplementation at the time of discharge. Mean hospital stay was 18 days. Time to attain full solid diet (mean 4.68 ± 4.93 months) was less in Group 1 (3.53 ± 3.54 months) compared to Group 2 (5.83 ± 6.14 months).

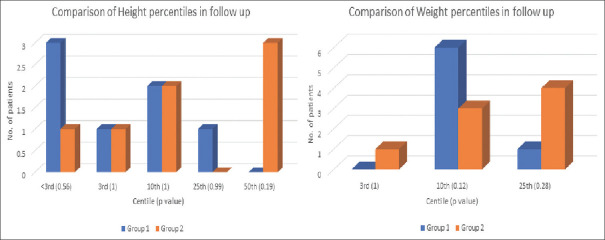

Esophageal dilatation was required in several patients in the first 1–2 years after surgery and was similar in both groups [Table 3]. The indications were prophylactic (n = 2), dysphagia for solids (n = 5), anastomotic stricture (n = 2), foreign body/food bolus impaction (n = 1), and prolonged salivary leak (n = 1). Four patients, two in each group, underwent excision of gastrostomy fistula and gastrostomy site granuloma. One patient in Group 2 required removal of complete lower esophageal wrap 1 year after surgery for dysphagia for solids not responding to dilatation. GER scan results were compared between the groups at least 2 years after surgery and was found to be less in Group 2 but did not attain statistical significance. Two patients one in each group who had reflux in the first 1 year after surgery were seen to have no reflux at the 2-year or more postoperative study. Although not attaining statistical significance, the height and weight centiles at the last follow-up were slightly better in Group 2 compared to Group 1 [Figure 2]. All children (n = 15) who were >3.5 years age were going to age-appropriate class although schooling was affected initially in most due to hospital visits for dilatation.

Table 3.

Long-term follow-up of Group 1 and 2 patients

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up period (months), mean±SD (range) (median) | 45.37±23.24 (14-84) (43.5) | 46.1±14.64 (32-72) (41) | 45.75±18.77 (14-84) (41) |

| Age at the last follow-up (years), mean±SD (range) | 5.7±2.01 (2-8) | 5.8±1.46 (4-8) | 5.75±1.7 (2-8) |

| Procedures in the first 1-2 years after surgery | |||

| Number of esophageal dilatations per patient | |||

| Nil | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| 1-2 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| 3-7 | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| ≥8 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Other procedures | |||

| Excision of gastrostomy fistula/granuloma | 1/1 | 1/1 | 2/2 |

| Removal of complete lower esophageal wrap | NA | 1 | 1 |

| Complaints at the last follow-up | |||

| No complaints | 5 | 5 | 10 |

| Occasional dysphagia for solids | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Cough at night/postprandial | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Persistent dysphagia for solids and regurgitation | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Occasional regurgitation of feeds or in the supine position | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Reflux on GER milk scan | |||

| Absent | 3 | 7 | 10 (P=0.118) |

| Low grade | 4 | 1 | 5 (P=0.282) |

| High grade | 1 | 0 | 1 (P=1) |

| NA | 1 | 2 | 3 |

GER: Gastroesophageal reflux, NA: Not available, SD: Standard deviation

Figure 2.

Comparison of height and weight percentiles between Group 1 and 2 patients at the last follow-up

DISCUSSION

Esophageal replacement is a major procedure associated with considerable morbidity in the initial few months after surgery. Fundal tube esophagoplasty[4] and Scharli's technique[5] utilize the LE and retain an intraabdominal stomach remnant. In the RGTE also, almost half of the stomach is retained providing a good reservoir capacity. The remnant stomach remains in the normal location. The mediastinal space occupied by a gastric tube is considerably less than that of a whole stomach or colon. The pyloric end of the gastric tube which anastomoses with the upper esophagus produces less acid and more mucous and should reduce chances of anastomotic stricture.

Inspite of these advantages, postoperative complications such as regurgitation of feeds, cough, dysphagia, and poor weight gain are common after RGTE. The left gastroepiploic artery is not as robust as the right gastroepiploic artery and this can predispose to stricture. There is a longer suture line in the mediastinum compared to a fundal tube esophagoplasty and it is important that the suturing is done in two layers meticulously to eliminate thoracic leakage. Randolph in a series with 34 patients in a 30-year experience noted that two-third of patients required 1–6 dilatations, with two requiring surgical revision of a tight stricture. Two patients had perforation of the thoracic tube during dilatation for stricture, of whom one did not survive.[6] In our study also, two-third of cases required one or more dilatations. These occurred at the esophageal anastomosis at the neck and improved with serial dilatations. No patient required surgical resection of the stricture although children who had undergone two-stage procedure were noted to have stenosis of the upper end of neo-esophagus requiring local mobilization at the time of esophago-esophageal anastomosis. Schettini and Pinus in their series also noted fistula and esophageal stenosis which responded to endoscopic dilatations.[7] A uniform diameter of the RGTE can be created by placing an appropriate size of red rubber catheter within. Problems of vascularity can also occur due to a wrongly placed initial gastrostomy.

In the thorax, the vagal nerves form the esophageal plexus behind the esophagus. From them, the anterior and posterior vagal trunks emerge and travel on the surface of the LE into the abdomen through the esophageal hiatus [Figure 1]. Branches arise in the lesser omentum and are motor to the smooth muscles and secretomotor to the glands of the stomach. Both the vagal nerves can be left intact in an RGTE by careful hiatal dissection. This can avoid problems of vagotomy such as diarrhea, delayed gastric emptying, atrophic gastritis, and consequent anemia.[8]

Choudhury et al. have highlighted the changes in heart rate amongst 24 patients undergoing esophageal substitution procedures performed during a 15-year period.[9] Nineteen patients underwent gastric pull-up and in 17 where the posterior mediastinal route was used, there was tachycardia in ten and bradycardia in two during mediastinal dissection and manipulation. Three deaths in their early experience were attributed to uncontrolled tachyarrhythmia. Intraoperative arrhythmias mostly occur due to irritation of the atria, vagal stimulation, or severe hypotension during mediastinal dissection and occasionally due to injury to the cardiac autonomic nerves. Pain, fever, or electrolyte disturbances such as hypokalemia are the common reasons for arrhythmias postoperatively. Most are transient and subside with appropriate treatment of the cause. If persistent and associated with hemodynamic instability, specific drug treatment should be instituted. Prolonged QT interval in the postoperative period can occur because of certain drugs such as erythromycin, azythromycin, antiarrhythmic drugs, ondansetron or electrolyte disturbances such as hypokalemia, hypocalcemia, and hypomagnesemia. The treatment depends upon the cause. If there is no known cause, beta-blockers can be given to prevent life-threatening arrhythmias. We did not require to start specific medications for any of our patients. In general, sustained changes in heart rate are rare after gastric tube replacement as they occupy less mediastinal space compared to gastric pull through.

Short and long-term outcomes after gastric tube esophagoplasty are limited compared to gastric or colonic pull through. Liu et al. in a metanalysis found that respiratory problems and early strictures were higher following gastric tubes (29.6%, 48.1%, respectively) compared to colon replacement (14.3%, 15.2%, respectively).[10] Reflux was also shown to be 48.1% in gastric tubes compared to gastric pull-up (16.5%) or colon replacement (13.7%). However, the data included only 27 patients with gastric tube pull through compared to 335 patients of colon replacement, and 127 of gastric pull through. In a long-term review of 44 patients managed for long gap EA, Lee et al. noted that GER was present in nearly all patients whether they underwent delayed primary anastomosis or esophageal replacement with greater curvature gastric tube.[11] No specific method has been described in the literature to reduce reflux following any esophagoplasty procedure. Following RGTE, Randolph noted that several patients reported reflux up the tube, two undergoing further surgery for the same including a partial fundic wrap later on.[12] In RGTE and gastric pull-up, the LE is excised. We have used the LE as a wrap at the gastro-neoesophageal junction in Group 2 patients. The distal esophagus in EA is not diseased unlike children with caustic stricture. Predisposition to Barrett's esophagus or esophageal carcinoma should also be less in the LE. Moreover, as it stays in continuity with the stomach contents, it is not completely disused. Our study has shown a lesser incidence of reflux on 99mTc reflux scans in children who had an additional lower esophageal wrap although it did not attain statistical significance. The remnant neo esophageal tube in the abdomen should also reduce regurgitation of feeds by the effect of intra-abdominal pressure with the lower esophageal wrap around it further enhancing the anti-reflux mechanism. Our procedure also helps in retaining the entire remaining stomach as a reservoir and not wasted partially for a Thal fundoplication. The length of the LE was variable and tended to be less in those who had undergone diversion for postoperative EA repair leak. We performed a wrap with the LE if the length was at least 3 cm. Those who had a longer length, i.e., 5–6 cm underwent a full loose wrap without compromising the left gastroepiploic vessel. However, we noted that two patients with a full wrap developed intermittent dysphagia to solids, one of whom responded to dilatation while the other required its excision. We, therefore, do not recommend a full wrap.

In the initial few months after RGTE, a majority of patients did not gain weight which slowly improved a year after surgery. This may be related to dysphagia, dysmotility, reflux, cough, etc., and multiple hospital visits. Once the issues mainly related to anastomotic stricture are sorted out, there is an improvement in the overall wellbeing of the child. The increase in the size of the stomach remnant with time also probably helps in the feeling of satiety and reduction in regurgitation which may never be achieved with a gastric pull-up. Children also learn to eat small frequent feeds with time.

Growth and overall quality of life are said to be similar in the long-term in patients who have undergone colonic bypass or gastric tube replacement.[13] In our study, although not statistically significant, the height and weight centiles at the last follow-up were slightly better in those with a lower esophageal wrap compared to conventional RGTE.

This study had its limitations. It was a retrospective study and not randomized. The number of patients was less in both groups partly because many patients were lost to follow-up after an initial esophagostomy and gastrostomy. In the first half of the study period, several patients underwent fundal tube esophagoplasty and therefore could not be included. The route taken by the RGTE and the procedure being conducted as a single or staged one was variable. The surgeon's preference based on their experience, the clinical situation, and intraoperative findings played a role in making these decisions. While these differences may contribute to intraoperative and early postoperative complications, this should not affect overall results in the short or long term. The number of patients undergoing staged procedures or retrosternal route for the tube was also significantly less as compared to single-stage and posterior mediastinal route. We also included only children with EA who are known to behave slightly differently from those who have undergone RGTE for corrosive stricture.[14]

Patients underwent a full or partial wrap with the LE depending upon its length. The future growth of this LE and any stasis within its lumen causing ulceration has to be considered although such a complication has not been noted so far. There is a concern that food particles may get impacted in the blind esophageal pouch. The pouch is fixed circumferentially in a nondependant position at the junction of neo esophagus and remnant stomach, in a transverse plane. Because of the nature of its location, if at all, some fluid content may go into the pouch which is very likely to move back into the stomach. In that way, it is very similar to any standard partial or complete fundoplication wrap. In one patient where the LE was excised later for dysphagia, no impacted food material was found within the lumen.

CONCLUSION

The use of the lower esophageal wrap as a fundoplication technique method has not been described before in the literature to the best of our knowledge and so could be considered as novel. Although not statistically significant, patients had better height and weight centiles in the follow-up period as well as less reflux on radionuclide scans. The technique could be useful in colon replacement esophagoplasty to reduce GER and ulceration due to the inability of the colon to withstand acid. Although rare, late complications are known to occur after RGTE.[15,16] Further long-term follow-up is therefore required in these children as they progress to adulthood. The true benefit will be known if larger number of patients undergo the procedure.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gavriliu D, Georgescu L. Esofagoplastie directacu material gastric. Rev Stiint Med. 1951;3:33–6. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heimlich HJ, Winfield J. The use of a gastric tube to replace or bypass the esophagus. Surgery. 1955;37:549–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burrington JD, Stephens CA. Esophageal replacement with a gastric tube in infants and children. J Pediatr Surg. 1968;3:24–52. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(68)90007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rao KL, Menon P, Samujh R, Chowdhary SK, Mahajan JK. Fundal tube esophagoplasty for esophageal reconstruction in atresia. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:1723–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2003.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schärli AF. Esophageal reconstruction by elongation of the lesser gastric curvature. Pediatr Surg Int. 1996;11:214–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00178419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Randolph JG. The reversed gastric tube for esophageal replacement in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 1996;11:221–3. doi: 10.1007/BF00178421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schettini ST, Pinus J. Gastric-tube esophagoplasty in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 1998;14:144–50. doi: 10.1007/s003830050466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Last RJ. Central nervous system. In: McMinn RM, editor. Last's Anatomy. 9th ed. Singapore: Longman Group Limited; 1995. pp. 577–642. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choudhury SR, Yadav PS, Khan NA, Shah S, Debnath PR, Kumar V, et al. Pediatric esophageal substitution by gastric pull-up and gastric tube. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2016;21:110–4. doi: 10.4103/0971-9261.182582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu J, Yang Y, Zheng C, Dong R, Zheng S. Surgical outcomes of different approaches to esophageal replacement in long-gap esophageal atresia: A systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e6942. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000006942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee HQ, Hawley A, Doak J, Nightingale MG, Hutson JM. Long-gap oesophageal atresia: Comparison of delayed primary anastomosis and oesophageal replacement with gastric tube. J Pediatr Surg. 2014;49:1762–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson KD, Noblett H, Belsey R, Randolph JG. Long-term follow-up of children with colon and gastric tube interposition for esophageal atresia. Surgery. 1992;111:131–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindahl H, Louhimo I, Virkola K. Colon interposition or gastric tube? J Pediatr Surg. 1983;18:57–63. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(83)80274-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta L, Bhatnagar V, Gupta AK, Kumar R. Long-term follow-up of patients with esophageal replacement by reversed gastric tube. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2011;21:88–93. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1267240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ashburn JH, Meyers MO, Phillips JD. Surgical treatment of esophagogastric dysfunction forty years after reverse gastric tube esophagoplasty for congenital esophageal anomaly. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46:399–401. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sitges AC, Sánchez-Ortega JM, Sitges AS. Late complications of reversed gastric tube oesophagoplasty. Thorax. 1986;41:61–5. doi: 10.1136/thx.41.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]