Abstract

A substantial fraction of common metabolites contains carboxyl functional groups. Their 13C isotopomer analysis by NMR is hampered by the low sensitivity of the 13C nucleus, slow longitudinal relaxation for lack of an attached proton, and the relatively low chemical shift dispersion of carboxylates. Chemoselective (CS) derivatization is a means of tagging compounds in a complex mixture via a specific functional group. 15N1-cholamine has been shown to be a useful CS agent for carboxylates, producing a peptide bond that can be detected via 15N-attached H with high sensitivity in HSQC experiments.1 Here we report an improved method of derivatization and show how 13C-enrichment at the carboxylate and/or adjacent carbon can be determined via one and two bond coupling of the carbons adjacent to the cholamine 15N atom in the derivatives. We have applied the method to the determination of 13C isotopomer distribution in the extracts of A549 cell culture and liver tissue from a patient-derived xenograft mouse.

Keywords: stable isotope-resolved metabolomics, Nuclear Magnetic Resonance, smart isotope tag, 15N1-cholamine, carboxyl groups, 13C6-glucose

Metabolomics-based approaches provide a powerful means for getting a holistic understanding of metabolic processes and are leading to advanced diagnostics and therapeutics.2,3 Low-molecular weight metabolites (≤ 1500 Da)4,5 can also be measured and evaluated as indicators of normal physiologic or pathologic processes, pharmacologic responses to treatment, etc.6 In particular, metabolomics coupled with stable isotope tracing (e.g. stable isotope-resolved metabolomics or SIRM) enables rigorous pathway reconstruction and flux analysis to answer key mechanistic questions in systems biology and biochemistry.7-9

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR) and mass spectrometry (MS) are the two leading analytical platforms used for metabolomics. Both tools enables the determination of stable isotope labeling patterns (positional isotopomers and mass isotopologues), which provides a deep and dynamic view of metabolic processes in cells, tissues, whole animals, and even humans.4,10,11 NMR is particularly suited for rigorous metabolite identification and reliable analysis of positional isotopomer distributions9, which constitute two of the biggest challenge in metabolomics.12,13 However, the complexity of biological extracts leads to overlapping resonances in one-dimensional (1D) NMR and thus to ambiguous peak assignment.14,15 This is exacerbated by stable isotope enrichment which causes additional peak splitting. This problem can be at least in part resolved by higher dimensional NMR experiments, particularly by exploiting the isotope editing abilities of NMR.7,16

To better achieve unambiguous metabolite assignment and reduce spectral crowding, stable isotope labeled CS probes have been developed to tag given functional groups for NMR analysis.1,17-19 In particular, the labeled CS derivatives are readily amenable for two-dimensional (2D) NMR analysis, which provides superior resolution and rigor for metabolite determination.20-22 These isotope tagging methods also have the dual advantage of enhancing detection by MS to facilitate structural determination via molecular formulae in addition to NMR properties17 Moreover, low-abundance and/or labile metabolites can be enriched or stabilized for quantitative analysis.23

Our group has previously developed aminooxy probes that react with keto functional groups and simultaneously introduce 15N into metabolites to enable NMR detection by 15N-edited methods.17 As carboxyl groups have no attached protons, they are detected directly by 13C NMR or indirectly by long-range couplings, which compromises sensitivity. Carboxylate carbons also have long T1 values, which further compromises sensitivity in direct detection. Tayyari et al.1 have developed the use of 15N1-cholamine to derivatize carboxyl groups to form a peptide bond (Scheme S1). This CS tag introduces a permanent positive charge into the molecule, which improves the ionization efficiency in MS analysis while enabling sensitive NMR detection at slightly acidic pH via one-bond coupling of 15N to the attached proton (HN). In 1H{15N}-HSQC (heteronuclear single quantum coherence) experiments, only the carboxylate derivatives are detected in very complex mixture of metabolites such as crude cell or tissue extracts. We have adapted this method for more sensitive determination of 13C enrichment at carboxylates by 15N-edited NMR. Here we report such application on determining 13C enrichment at the carboxylates and adjacent carbon of metabolites using 1H{15N}-HSQC and HNCO in crude extracts of cells and tissues with 10-20 mg wet weight or less. We also improved the derivatization efficiency, which contributed toward enhanced sensitivity of detection.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Chemicals and Reagents

[15N1]-cholamine bromide hydrobromide salt (15N1-cholamine) was obtained from the Metabolite Standards Synthesis Center (SRI International).24 4-(4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)-4-methylmorpholinium chloride (DMTMM) was purchased from ACROS organics (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The following metabolite standards and reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich: isoleucine, leucine, valine, alanine, glutamate, glutamine, aspartate, glycine, phenylalanine, histidine, tyrosine, tryptophan, serine, threonine, cysteine, cystine, N-acetyl-aspartate (N-AcAsp), formate, fumarate, 3-phosphoglycerate (3-PG), citrate, malate, alpha-ketoglutarate (α-KG), succinate, pyruvate, acetate, lactate, hydrochloric acid (HCl) and sodium hydroxide (NaOH). [U-13C]-pyruvate, [U-13C]-lactate, 1-13C-acetate, 2-13C-acetate and 1,2-13C2-acetate were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Andover, MA). Reduced glutathione (GSH) and oxidized glutathione (GSSG) were purchased from ACROS Organics (Thermo Fisher). 18 MΩ water was obtained using an ultrapure water system (Barnstead, Dubuque, IA).

Standard mixture

The standard mixture consisted of a set of metabolites summarized in Table S1. Individual standard stocks solutions were prepared and mixed to a final concentration of 3.88 mM. The mixture was then reacted with 15N1-cholamine in the presence of the catalyst DMMTM and analyzed by NMR for assignment purposes.

Four different isotopomers of acetate at 1 mM each (ca. 100% 13C enrichment in the three 13C isotopomers) were reacted with 15N-Cholamine in different combinations for illustrating the chemical shift coupling : 12C112C2-, 13C112C2-, 12C113C2-, and 13C113C2-acetate. The total amount of CO groups in the mixture were estimated for the reaction with 15N1-cholamine as described below. For quantitative analysis, the relative amount of each isotopomer present in the reaction mixture was determined by 1D 1H NMR using a relaxation delay of 15 s.

Biological samples

Human lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with dialyzed FBS (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and 10 mM [13C6]-glucose for 24 h at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. When the cells reached 70% confluence, the medium was aspirated and the cells were washed three times with ice-cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS) followed by subsequent quenching with cold acetonitrile (CH3CN) to halt metabolic activity and addition of nanopure water (CH3CN:H2O at 2:1.5 (V/V)) to facilitate cell scraping and collection.

The liver was dissected from a PDX mouse fed with regular glucose or [13C6]-glucose for 18 h, snap frozen and pulverized in liquid nitrogen into < 10 μm particles using a Spex freezer mill (Spex SamplePrep, Inc., Metuchen, NJ) to maximize extraction efficiency while maintaining biochemical integrity. Metabolites were subsequently extracted from liver tissue powder as described previously25,26 using CH3CN:H2O:CHCl3 (2: 1.5:1 volume ratio). The aqueous phase (polar metabolites) and organic phase (non-polar metabolites) were isolated and concentrated with either lyophilization (FTS Flexi-Dry, Stone Ridge, NY) or evaporation in a Speedvac device (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany), respectively.

Optimization of cholamine adduct formation

We initially derivatized standards with cholamine (Table S1) using the method described by Tayyari et al. 1 and found that the reaction did not always reach completion even after 4 hours. We thus optimized the reaction conditions as follows. The reaction mixtures were made by mixing the substrates (carboxyl-containing compounds), 15N1-cholamine and DMTMM at molar ratios of 1:15:60 in H2O. For cell or tissue extracts, the total amount of carboxylates was estimated from 1D 1H NMR spectrum by quantifying the peak areas of all amino and organic acids present, while the CS reagents were added at twice this estimated value to ensure complete reaction. The reaction was initiated by adjusting the pH of the mixture to 8 and kept at 60 °C for 2 h in a dry bath. Two more doses of DMTMM (half of the initial amount each) were added 30 min and 1 h after the reaction was initiated to compensate for DMTMM degradation due to its instability in water.27 These provisions helped achieve a complete reaction. The reaction mixture was then lyophilized for at least 24 h to remove all solvent while concentrating the sample. Samples were reconstituted in 117 μL of H2O and 13 μL of D2O containing 0.5 mM of 2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonate (DSS) as internal standard. The mixtures were then acidified to pH 4-5 to ensure protonation of the 15N amide group and minimize chemical exchange before transferring to 3 mm Shigemi tubes for NMR analysis.

NMR spectroscopy

All NMR spectra were recorded at 288 K on a Bruker Avance III 16.45 T spectrometer (Bruker BioSpin, USA) operating at 700.20 MHz for 1H frequency and equipped with a 5 mm cryogenically cooled HCNP inverse quad probe. For each sample, two 1D spectra were recorded: 1) 1D 1H spectra were acquired using the zgpr pulse sequence with presaturation of the water resonance using 25 Hz bandwidth, 256 transients, a 15 ppm spectral width, a 4.0 s relaxation delay, and a 2.0 s acquisition time corresponding to 44640 data points. Under these conditions, the magnetization recovers > 95 %. 1H spectra were zero-filled to 128 K data points and apodized with 1 Hz exponential function. 2) 1D 1H{15N}-HSQC spectra were recorded using hsqcetf3gpsi pulse sequence with a 10 ppm spectral width, 1024 transients, a 1.75 s relaxation delay, and a 0.25 s acquisition time, during which adiabatic decoupling was applied. The spectra were processed with zero-filling to 16 K data points and apodized with a cosine squared function as well as a 4 Hz exponential line broadening. The samples were further characterized using additional 15N-edited experiments including high-resolution 2D 1H{15N}-HSQC, which were collected with 3500 complex points in the direct dimension over a 10 ppm spectral width and 2048 points in the indirect dimension with a 50 ppm spectral width. The FIDs were linear predicted once and zero-filled to 8192 and 4096 complex data points in direct and indirect dimensions, respectively, yielding a resolution of 0.85 Hz/point in both 1H and 15N dimension. The transmitter frequency offsets were set at 110 ppm in the 15N dimension and 4.7 ppm in the 1H dimension.

To verify the simultaneous presence of 13C and 15N in the cholamine adducts, both 2D H(N)CO and HN(CO) spectra were recorded using the 3D HNCO pulse sequence (hncogp3d with Waltz65 composite decoupling) by choosing the corresponding dimensions. In this experiment the magnetization transfer is HN-15N-13CO and then reversed to 1H for detection.28 A total of 16 transients per increment were collected in the 1H dimension with a 0.1 s acquisition time, corresponding to 2048 complex points, and 128 increments were recorded in the indirect dimension. The recycle time was set to 1.1 s. The 1H, 15N and 13C carrier frequencies were set at 4.7 ppm, 117 ppm and 173 ppm, with spectral widths of 14 ppm, 65 ppm and 35 ppm, respectively. Both HNCO spectra were processed with zero-filling to 4 K data points and apodized with cosine square function and a 1 Hz exponential function in the direct dimension. All NMR data were acquired using TOPSPIN 3.5 (Bruker BioSpin, USA) and processed and analyzed with MestReNova software (MNova 10.0, Spain). 1H and 13C chemical shifts were referenced using DSS as internal reference. 15N was referenced to the amide 15N chemical shift of the formate adduct (123.93 ppm) as reported previously.1

NMR assignments and quantifications

Chemical shifts in 1D 1H and 1D 1H{15N}-HSQC spectra of the standard derivatives were assigned based on previous literature reports1,18 and our own data. These assignments were in turn used to assign the derivatives in cell and tissue extracts recorded under identical experimental conditions. The 1D assignments were further validated by 2D 1H{15N}-HSQC and HNCO experiments with 1H and 15N referenced to formate adduct at 8.05 and 123.93 ppm, respectively. To confirm the 13C splitting patterns and isotopomer distributions, 2D 1H{15N}-HSQC spectra of several standards labeled at different positions were recorded.

All NMR integrations and quantifications were done using the MestReNova software. For 1D spectra, global deconvolution was applied on those peaks of interest and peak area information was extracted for quantification. Concentrations of metabolites were calculated by calibrating against the known concentration of internal standard DSS. For 2D 1H{15N}-HSQC spectra, the base-planes were carefully phased and corrected with 3rd order Bernstein polynomials, and the volume was manually integrated for each peak in the spectrum. For each individual peak in a group, an elliptical shape integration region was selected and applied to encompass each individual peak. The edges were placed carefully at the lowest point on the projection where the peaks overlap. Volumes in regions not containing peaks were used for assessing signal to noise ratio and baseline artefacts. All peak volumes from each metabolite were summed up and ratios between different metabolite adducts were calculated accordingly. This approach has been previously applied to 2D 1H TOCSY spectra that accurately reproduced the expected natural abundance of standards.29 We cross-checked the integration accuracy and precision using both unlabeled samples (i.e. 13C present at the known natural abundance of 1.107 %) and by comparison with independent integration in 1D proton spectra where possible as shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1:

2D 1H{15N}-HSQC quantification of a mixture of 13C-acetate isotopomers.

| Mixtures of acetate isotopomers a | Reaction ratios b | Ratios determined by 2D 1H{15N} HSQC c |

|---|---|---|

| 13CH312COOH + 12CH313COOH | 1:1.24 | 1:1.28 |

| 12CH312COOH + 13CH312COOH + 12CH313COOH | 1:1:1 | 1:1:1.14 |

| 12CH312COOH+13CH313COOH | 1:1 | 1:1.21 |

| 12CH313COOH + 13CH313COOH | 1:1.2 | 1:1.3 |

Isotopomer mixtures were derivatized with 15N-cholamine and analyzed as described in the Methods.

Isotopomer ratios used for derivatization as determined by methyl peaks quantified in 1D NMR

Isotopomer ratios determined by volume integration of cross-peaks in the high-resolution 1H{15N}-HSQC spectrum; estimated errors on volume integration were < 10%

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Optimization of the 15N1-cholamine tagging reaction

We first optimized the 15N1-cholamine tagging reaction for carboxylate-containing metabolites. The very high concentration of DMTMM used in the previous report1 makes reaction mixtures very salty, which not only is incompatible with direct infusion MS, but also compromises detection by NMR.

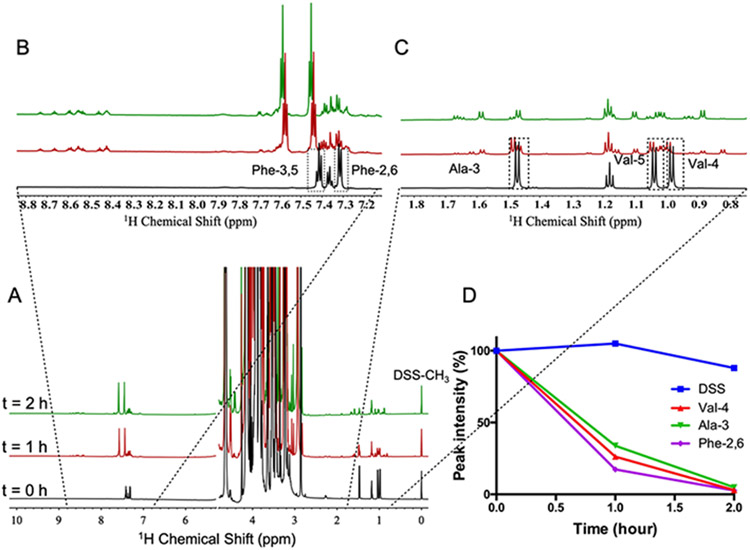

We systematically varied the ratios of 15N1-cholamine and DMTMM at different temperatures, pH values, and reaction times. The formation of the derivatives was monitored by 1D 1H{15N}-HSQC and 1D 1H NMR as the chemical shifts of the organic and amino acids changed upon forming a peptide bond. Since the unreacted and derivatized metabolites have resolved chemical shifts, the reaction efficiency can be readily determined as shown in Figure 1A-C. We found that optimal conditions were achieved at ratios of carboxylates: 15N1-cholamine: DMTMM = 1:15:60. We also enhanced the reaction rate and obtained a more complete reaction by increasing the pH from 71 to 8 and the temperature from room temperature to 60 °C as well as with two extra doses of DMTMM at 30 min and 1 hour to drive the reaction. The quantification of the starting mixture (alanine, valine, glycine, and phenylalanine) and their corresponding adducts was performed by integrating non-overlapping signals at three time points (0 h, 1 h and 2 h). The time course of the reaction based on the NMR data showed that under these conditions the reaction was essentially complete for all of the standards measured, with a fractional conversion of > 95% at 2 h (Figure 1D). For all subsequent analyses, we used this optimized reaction conditions of carboxylate: 15N1-cholamine: DMTMM ratios at 1: 15: 60, pH 8, 60 °C for 2 h.

Figure 1: Time course of 15N1-cholamine tagging reaction in a mixture of amino acids.

A mixture of Ala, Val, Gly, Phe (1 mM each compound) was reacted with 15N-cholamine in ratios of 1: 15: 60 at 60 °C in H2O. The formation of the peptide derivatives was monitored at three time points (0 h, 1 h and 2 h). (A) 1D 1H-NMR spectra (δ 10 – 0 ppm) were recorded at 16.45 T and processed as described in the Experimental Section. (B, C) Expansion of A, representing the aromatic/peptide region (B) and methyl regions (C), where the unmodified amino acids were marked with dashed boxes. D) Changes in the peak intensities of the unmodified amino acids during the reaction with 15N-cholamine with respect to the original

NMR characterization of 15N1-cholamine tagged standard mixture using the optimized method

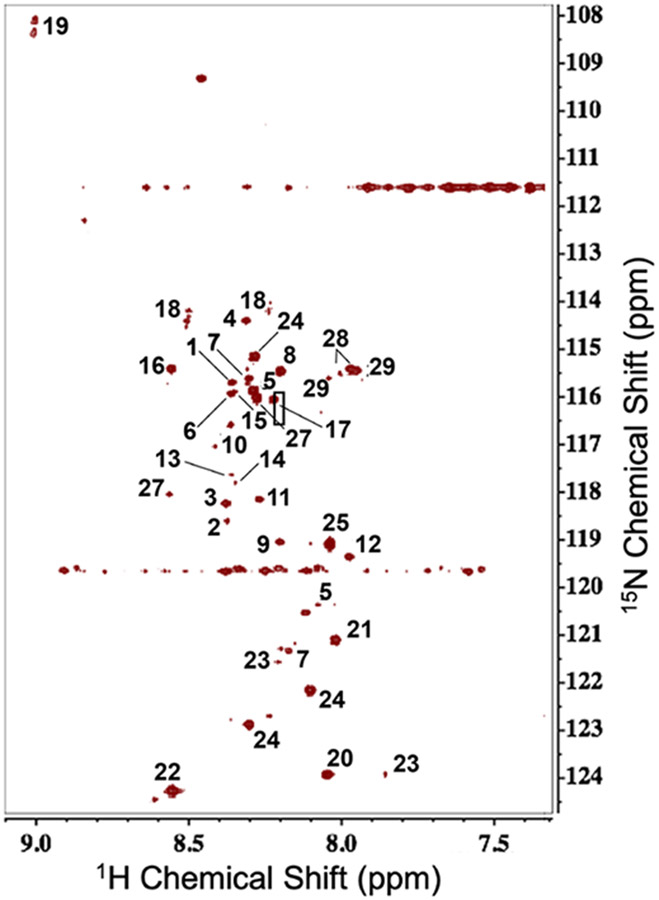

A set of 29 carboxylate-containing metabolites frequently found in polar extracts of cells and tissues (Table S1) was subjected to the optimized reaction with 15N1-cholamine for chemical shift assignments of the derivatives. A 2D 1H{15N}-HSQC spectrum of this mixture was recorded after 2 h of reaction at 60 °C and is shown in Figure 2. Each cross-peak in the spectrum corresponded to a unique peptide group, the product of the reaction between the carboxylate and 15N1-cholamine (cf. Scheme S1). Therefore, metabolites with one carboxylate should show a unique peak in the spectrum, whereas those metabolites containing two or more carboxylates, can show additional peaks depending on the molecular symmetry.1 However, in some cases, two sets of cross-peaks were observed for a single carboxylate-containing metabolite, such as lactate, which is likely due to the formation of cis and trans peptide isomers (Table S1; Figure 2, peaks 18).

Figure 2. 2D 1H{15N}-HSQC spectrum of 15N1-cholamine derivatives of 29 standards mixture.

The standard mixture was reacted for 2 h at 60° with 15N1-cholamine and DMTMM in ratios of 1: 15: 60 in H2O as described in the Experimental Section. The spectrum was recorded at 16.45 T and processed as described in the Experimental Section. Assignment of carboxyl-containing metabolites mixture tagged with 15N1-cholamine: 1. Leu, 2. Ile, 3. Val, 4. Ala, 5. Glu, 6. Gln, 7. Asp, 8. Gly, 9. Phe, 10. His, 11. Tyr, 12. Trp, 13. Ser, 14. Thr, 15. Cys, 16. Cystine, 17. N-acetyl-Asp, 18. Lactate, 19. Pyruvate, 20. Formate, 21. Acetate, 22. Fumarate, 23. Citrate, 24. Malate, 25. Succinate, 26. α-KG, 27. 3-phosphoglycerate, 28. GSH, 29.

We also noted that the 15N resonances of those peptide adducts with COO- adjacent to NH3+-, CH- or OH- groups resonated in the 114 - 119 ppm region, whereas those COO- groups next to the CH2,3- groups resonated in the 120 - 124 ppm region. This distinguishes the C1 and C5 carboxylates for glutamate, for example, where the C1 and C5 adducts showed 1H/15N peptide shifts at 8.30/115.85 and at 8.08/120.39 ppm, respectively (Figure 2, peak 5). The optimized procedure recapitulates the results reported by Tayyari et al. 1

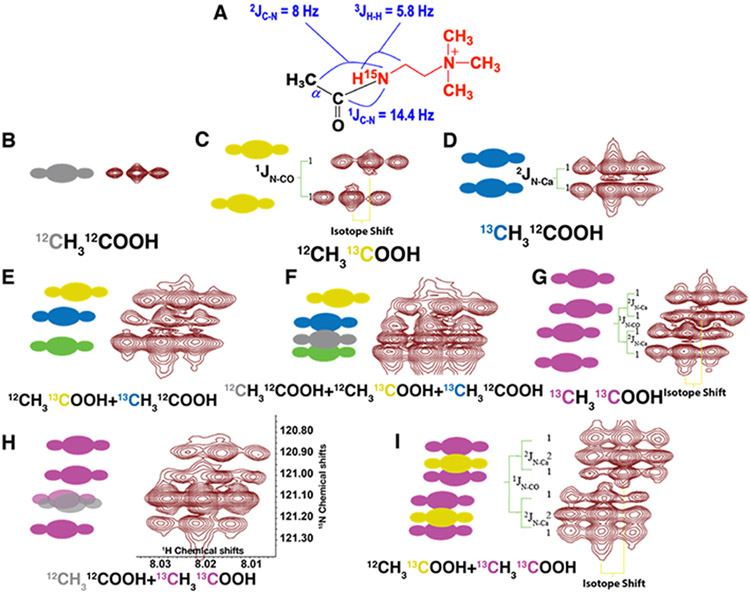

Determination of 13C enrichment at carboxylates and adjacent carbons

To demonstrate the detection of 13C enrichment in carboxylates after the CS derivatization, different 13C-acetate isotopomer standards were reacted with 15N1-cholamine to form the peptide adducts (Figure 3A), and high-resolution 1H{15N}-HSQC spectra were recorded. Figure 3 shows the observed splitting patterns for the different isotopomers, along with the patterns expected using the measured 1,2JCN values and isotope shifts. In the 1H dimension, the resonances appear as triplets owing to coupling of 15N proton to the neighboring methylene protons (Figure 3B-I). In the 15N dimension, the presence of 13C splits the 15N resonance into different patterns depending on the 13C isotopomers. In the singly 13C labeled acetate spectra, the coupling constant measured for the 1JNCO (14.4 Hz) (Fig. 3C) was larger than that for the 2JNCA (8 Hz) (Figure 3D), which agrees with the general coupling ranges of 14 - 16 Hz and 7 - 9 Hz, respectively.30,31 When both carbon atoms are 13C enriched (Figure 3G, Figure S1C), the splitting pattern in the 15N dimension became a doublet of doublets, which is distinct from the two overlapping doublets that arose from a mixture of 13C-1 and 13C-2 acetate adducts (Figure 3E, and Figure S1B). A perfectly aligned doublet is expected in the 15N dimension of the 1H{15N}-HSQC spectrum for the 15N1-cholamine adduct of acetate labeled at either 13CO or 13CA, i.e. two non-overlapping doublets (Figure S1A). However, in practice, both 1H and 15N chemical shifts were perturbed by the 13C labeling (3.8 Hz for 13CO, two bonds and 0.5 Hz for 13CA, three bonds) (Figure S1B), such that the two doublet halves at the lower field in the 15N dimension overlapped, resulting in an apparent three-peak instead of the expected four-peak pattern (Figure 3E; Figure S1B). This isotope-dependent shift is consistent with 13C-1H versus 13C-2H shifts in sp3 hybridization,29,32 although the detailed mechanism is not known. Also, due to this apparent isotope shift, the labeled acetate adducts peaks did not appear centered on the unlabeled peak in the splitting patterns, but moved down-field in the 15N dimension (Figures 3F, H). Furthermore, in the mixture of the doubly 13C-labeled and unlabeled acetate adducts (Figure 3H), one of the peaks from the doublet of doublets overlapped with the unlabeled peaks due to the isotope shift. An even more complicated splitting pattern resulted from the combination of singly 13CO and doubly 13C-labeled acetates, i.e. a doublet of doublets superimposed on a doublet pattern (Figure 3I). Based on the coupling constants and isotope shift, the peak patterns in the 2D 1H{15N}-HSQC spectra of 15N1-cholamine adducts of a mixture of 13C-acetate isotopomers were readily assigned.

Figure 3. Simulated and observed cross-peak splitting patterns in 2D 1H{15N}-HSQC spectra of different mixtures of acetate isotopomers.

A) Structure of the product of acetate reacted with 15N-cholamine showing the different coupling constants between 13C-15N and 1HN-1H. B-I) Side by side comparison of the simulated and observed peak patterns of different acetate isotopomer mixtures. The following peak patterns are evident in the 15N dimension: 12CH312CO2- a singlet (B), 12CH313CO2- a doublet with 1JCN = 14.4 Hz (C), 13CH312CO2- a doublet with 2JCN = 8 Hz (D), 12CH313CO2- + 13CH312CO2- two overlapping doublets or an apparent triplet (E), 12CH313CO2- + 13CH312CO2- + 12CH312CO2- an apparent triplet plus singlet (F), 13CH313CO2- a doublet of doublet (G); 12CH312CO2- + 13CH313CO2- a doublet of doublet plus overlapping singlet (H), and 12CH313CO2- + 13CH313CO2- a doublet of doublet plus a doublet (I). Different colors indicate different 13C label positions in the acetate isotopomers: Gray, 12C; Yellow, 13CO; Blue, 13CA; Purple, 13CO-13CA; Green, overlapping of yellow and blue peaks. Pixels are scaled to the coupling constants to accurately represent the splitting patterns. The chemical shift scales in both dimensions are shown in panel H, which is the same for all panels.

Once assigned, the ratio of the different isotopomers could be determined by volume integration as described in the Experimental Section. To test the reliability of the quantification, we recorded high-resolution 2D 1H{15N}-HSQC spectra of mixtures of 13C acetate isotopomer adducts with known concentrations.

We first verified the relative abundances of individual acetate species present in each mixture by 1D 1H NMR before the reaction started. After completion of the reaction, the relative abundances of the cholamine adducts of the acetate isotopomers were determined from the 2D 1H{15N}-HSQC spectra. For the unlabeled acetate adduct, the total volume of the three component peaks (due to the splitting by the cholamine CH2) were integrated. For 13C-labeled adducts that showed 13C-15N splitting in the 15N dimension, all component peaks of each triplet were integrated and added together. However, due to the isotope shifts, as explained in Figures 3 and S1, there were overlapping triplets in certain combinations of the isotopomer mixtures. For example, in Figure 3E, the bottom triplet was the sum of two overlapping triplets each derived from the 13C1-2 or 13C1-1 isotopomers of acetate. We determined the volume ratio of these triplets to be 1: 0.78: 1.84 and the ratio of the top two triplets were used to determine the ratio of the isotopomer adducts. We found that the volume ratio for 13C1-1- and 13C1-2-acetate was 1:1.28, which compares well with the expected ratio of 1:1.24 determined by 1D 1H NMR before reaction with cholamine (cf. Table 1). For quantifying the mixture of unlabeled and 13C2-acetate (Figure 3H), the volume of the third triplet (16.6 units) was resulted from overlap of the unlabeled acetate adduct with one of the doubly labeled adducts. The unlabeled species was thus estimated using the total volume of the third triplet after subtracting the average of the other three (3.85 ± 0.19 units), corresponding to a ratio of 13C2- to unlabeled acetate of 1.21 ± 0.1, or a mole fraction of the labeled species of 0.55 ± 0.02. In the 13C2-acetate + 13C1-1-acetate adduct mixture (Figure 3I), the ratio of the two species was 1:1.2 before the reaction and 1:1.3 after the reaction, as determined from the 2D 1H{15N}-HSQC spectrum in good agreement with the expected ratio (Table 1). Overall, the isotopomer ratios in the mixtures determined from the high-resolution 2D 1H{15N}-HSQC spectra agreed well with the expected ratios (Table 1). Thus, the CS adduct analysis by NMR not only detected 13C labeling at the carboxylates and the neighboring carbon, but also quantified their fractional enrichments.

Confirmation of 13C1 enrichment in 15N1-cholamine adducts by HNCO

The HNCO triple resonance experiment detects the interactions among 1H, 15N, and 13CO in a peptide bond so that a signal is observed only when a 13C-enriched carboxylate reacted with 15N-cholamine.

For this experiment, a mixture of 13C labeled and unlabeled standards comprising [13C]-lactate, [13C]-pyruvate, serine, glutamate, citrate, GSSG and formate (as reference compound) was reacted with 15N-cholamine under optimized conditions as described above. The resulting solution was first analyzed by 2D 1H{15N}-HSQC to confirm the successful reaction with 15N1-cholamine (Figure S2). Both sets of cross-peaks of the [13C]-lactate adduct (peaks 18) showed a doublet of doublets pattern in the 15N dimension, with splittings of 1JN-CO = 16.45 Hz and 2JN-Ca = 8.70 Hz, respectively (Figure S2 B, D), indicating 13C labeling at both C1 and C2 positions. For pyruvate, in addition to the two peaks previously reported by Tayyari et al. 1 (Figure S2 C), we observed a major cross-peak at around 9.00 ppm for 1H and 108.14 ppm for 15N (Figure S2, peak 19).

The sample was then analyzed by HNCO, where only the first increment of the HN or HCO plane were acquired. Figure S3 shows both the H(N)CO plane (Figure S3A) and HN(CO) (Figure S3B) planes of the 15N adducts of the standards. As expected, only the cross-peaks of [13C3]-lactate and [13C3]-pyruvate adducts showed up in both planes with each arising from the 13C-15N one-bond coupling and their proton and nitrogen chemical shifts agreeing with those in the 1H{15N}-HSQC spectrum. Table S2 showed the assigned carboxylate chemical shifts in the H(N)CO (Figure S3A) and HN(CO) (Figure S3B) spectra. These represent direct evidence for 13C labeling at the C1 position of the reacted carboxylates and the chemical shifts of either proton or nitrogen matched those in the HSQC spectra.

Application to 13C-carboxylate isotopomer analysis of cell and tissue extracts

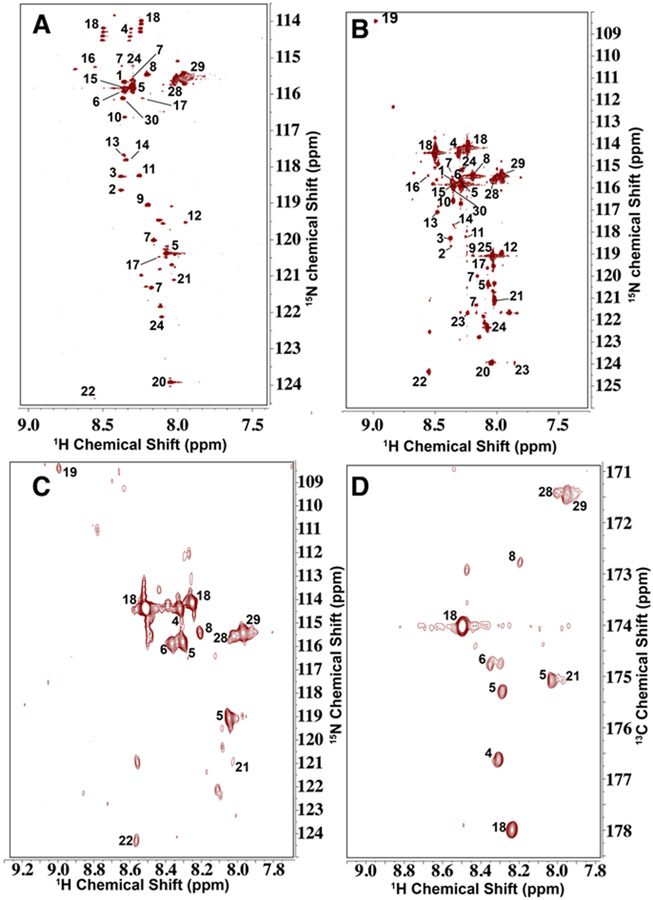

We applied the optimized method to polar extracts of A549 cells grown in [13C6]-glucose (Figure 4A) and liver tissue (Figure 4B, Fig. S5) dissected from a PDX mouse fed on a [13C6]-glucose-based liquid diet 26 to analyze their carboxylate-containing metabolites content and 13C-isotopomer distributions. In the 2D 1H{15N}-HSQC spectra, we observed 25 and 28 metabolites in A549 and liver, respectively, the assignments of which are shown in Table S1. From the 15N splitting patterns, we confirmed that the A549 cell extract were enriched in 13C at the carboxylate (C1) and/or the next neighboring carbon (C2) for lactate (18), alanine (4), glycine (8), and glutamate (5) and the mouse liver tissue extract was 13C enriched at the same positions for lactate (18), alanine (4), glutamate (5), and GSH/GSSG (28, 29).

Figure 4. Analysis of 15N1-cholamine tagged carboxyl groups in human lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells and mouse PDX liver tissue extracts.

[13C6]-glucose treatment, polar extraction, and NMR experiment setups were as described in the Experimental Section. A) High resolution 2D 1H{15N}-HSQC spectrum of 15N1-cholamine derivatized extract of A549 cells cultured in [13C6]-glucose enriched DMEM media. Peak assignments are shown in Table S1. Ala (4), lactate (18), Glu (5), and Gly (8) peaks showed signature splitting patterns in the N dimension, which confirms 13C labeling at the carboxylate (C1) and/or the neighboring carbon (C2) in these metabolites. B) High resolution 2D 1H{15N}-HSQC spectrum of 15N1-cholamine derivatized extract of PDX mouse liver tissue after liquid diet administration of 13C6-glucose. Lactate, alanine, glutamate, glutamine, GSH/GSSG showed 13C enrichment in the N dimension. C) The first increment of HNCO experiment in the HCO plane of the PDX mouse liver tissue extract reacted with 15N1-cholamine. It confirmed 13C labeling at the carboxylate group of these metabolites . D) The first increment of HNCO experiment in the HN plane of the PDX mouse liver tissue extract reacted with 15N1-cholamine, confirming 15N labeling in these metabolites.

In addition, 2D H(N)CO and HN(CO) spectra were recorded for both derivatized extracts of A549 cells and mouse liver tissue (Figure S4 A, B and Figure 4 C, D) to further verify the assignment of the labeled compounds shown in Table 2. The H(N)CO assignments also confirmed those for HN(CO) (Table 2) and the corresponding 2D 1H{15N}-HSQC (Figure 4A). In addition, some of the 13C enriched metabolites not easily observed due to the dispersion of signals in the nitrogen dimension of the HSQC spectra can be found in the HNCO spectra, such as glycine, acetate (Table S3).

13C quantification of labeled metabolites in the polar extracts of A549 cells and mouse liver

For accurate determination of 13C fractional enrichment in the carboxylates of A549 metabolites in Fig. 4A, high-resolution 2D 1H{15N}-HSQC spectra were acquired for peak volume integration using the MNova software. From the corresponding 1D 1H NMR spectrum (data not shown), the 13C enrichment in alanine and lactate was estimated as 78% and 70% respectively, based on the central and 13C satellites of the methyl resonances. As the peak pattern of their 13C satellites indicate uniform labeling in both metabolites (consistent with their transformation from [13C6]-glucose via glycolysis), the 1D 1H data provided an indirect estimate of the 13C enrichment at the carboxylates.9 The 13C enrichment in carboxylates from the 2D 1H{15N}-HSQC experiment were determined to be 80% for Ala and 90% for lactate. The enrichment for alanine is in good agreement between the two methods. The discrepancy for lactate is most likely due to the coincidence of the 12C-methyl resonances of lactate and threonine at 1.32 ppm in A549 extracts 33 at neutral pH. Threonine is an essential amino acid in mammalian cells and cannot be labeled from [13C6]-glucose, thus leading to an underestimation of the 13C enrichment of lactate from the 1D 1H spectrum. There was no such interference in the 2D 1H{15N}-HSQC spectrum, which provides a more accurate and direct estimate of the enrichment at C-1 and C-2 of lactate, which is expected to be comparable to that of Ala as they share the common precursor pyruvate.

The same method of quantification was also applied to the mouse liver extracts. The 2D HSQC spectra showed 47% 13C labeling in lactate and 57% in alanine, which is consistent with the overall labeling levels determined by 1D proton spectrum previously reported for this method of administration.26

Moreover, the method afforded more rigorous assignment of metabolite isotopomers. Although 13C-edited NMR methods for indirect detection of carboxylates such as 1H{13C}-HMBC are available without the need for derivatization, they are less sensitive due to the smaller magnetization transfer via > one-bond J coupling and more difficult in data interpretation due to complex 13C spin topologies.

CONCLUSIONS

The 15N-cholamine-based chemoselective derivatization coupled with 15N-edited NMR analysis provides a sensitive and robust means for determining carboxylate-containing metabolites in complex mixtures. Using a standard mixture of 29 metabolites, we have improved the method by optimizing the derivatization conditions including cholamine to catalyst ratio, temperature, and pH to achieve >95% efficiency. By applying the method to mixtures of 13C-acetate isotopomers, we demonstrated the value of this method for determining isotopomer distribution of acetate with 13C enriched at the carboxylate and/or neighboring carbon by high-resolution 1H{15N}-HSQC. We have also applied the method to determine the isotopomer distribution of 13C-labeled metabolites in extracts of < 10 mg wet weight (or 1 mg dry mass) of cells and mouse tissue, which is impractical by direct 13C detection methods. Thus the present method adds to the arsenal of NMR methods for profiling stable isotope-enriched isotopomers, which is crucial to reconstructing metabolic networks for gaining systems biochemical understanding of biological systems.7-9,16

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health 5R01ES022191-04, 3R01ES022191-04S1, 1U24DK097215-01A1, P01 CA163223-01A1 and 1P20GM121327-01. We thank Dr. Timothy Scott for the mouse sample preparation and Yan Zhang for preparing the A549 cells.

The data obtained in this study will be accessible at the NIH Common Fund’s NMDR (supported by NIH grant U01-DK097430) website, the Metabolomics Workbench, https://www.metabolomicsworkbench.org

Abbreviations:

- CS

chemoselective

- DMTMM

4-(4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)-4-methylmorpholinium chloride

- 2D, 3D

two, three dimensional

- DSS

2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonate

- FID

free induction decay

- HSQC

Heteronuclear Single Quantum Coherence

- PDX

patient-derived xenografts

- SIRM

stable isotope-resolved metabolomics

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supporting Information. Scheme S1: reaction of cholamine with carboxylates. Figure S1: Isotope shift effect on 1H{15N}-HSQC peak patterns of 15N1-cholamine derivatized acetate; Figure S2: 13C labeled isotopomers in high-resolution 1H{15N}-HSQC spectrum of 15N1-cholamine adducts of 7 standards; Figure S3: 2D HNCO experiment for detecting 13C enrichment of carboxylates; Figure S4: 2D HNCO analysis of derivatized extract of [13C6]-glucose-treated A459 cells confirmed 13C labeling in metabolite carboxylate group. Figure S5: 2D 15N-HSQC spectrum with 1D projections of both dimensions.

Table S1 NMR 1H, 13C and 15N assignments.

REFERENCES

- (1).Tayyari F; Gowda GA; Gu H; Raftery D (2013). "15N-cholamine--a smart isotope tag for combining NMR- and MS-based metabolite profiling." Anal Chem 85(18): 8715–8721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Nicholson JK; Holmes E; Wilson ID (2005). "Gut microorganisms, mammalian metabolism and personalized health care." Nature reviews. Microbiology 3(5): 431–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Fan TW; Lorkiewicz PK; Sellers K; Moseley HN; Higashi RM; Lane AN (2012). "Stable isotope-resolved metabolomics and applications for drug development." Pharmacology & therapeutics 133(3): 366–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Bingol K; Bruschweiler R (2014). "Multidimensional approaches to NMR-based metabolomics." Anal Chem 86(1): 47–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Viant MR; Kurland IJ; Jones MR; Dunn WB (2017). "How close are we to complete annotation of metabolomes?" Current opinion in chemical biology 36: 64–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Buyse M; Sargent DJ; Grothey A; Matheson A; de Gramont A (2010). "Biomarkers and surrogate end points--the challenge of statistical validation." Nature reviews. Clinical oncology 7(6): 309–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Lane AN; Fan TW-M (2017). "NMR-based Stable Isotope Resolved Metabolomics in systems biochemistry." Arch. Biochem. Biophys 628: 123–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Bruntz RC; Higashi RM; Lane AN; Fan TW-M (2017). "Exploring Cancer Metabolism using Stable Isotope Resolved Metabolomics (SIRM)." J. Biol. Chem 292: 11601–11609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Fan TW-M; Lane AN (2016). "Applications of NMR to Systems Biochemistry." Prog. NMR Spectrosc 92: 18–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Newgard CB (2017). "Metabolomics and Metabolic Diseases: Where Do We Stand?" Cell Metab 25(1): 43–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Sellers K; Fox MP; Bousamra M; Slone S; Higashi RM; Miller DM; Wang Y; Yan J; Yuneva MO; Deshpande R; Lane AN; Fan TW-M (2015). "Pyruvate carboxylase is critical for non-small-cell lung cancer proliferation." J. Clin. Invest 125(2): 687–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Pontoizeau C; Herrmann T; Toulhoat P; Elena-Herrmann B; Emsley L (2010). "Targeted projection NMR spectroscopy for unambiguous metabolic profiling of complex mixtures." Magn Reson Chem 48(9): 727–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Fan TW-M; Lane AN In Methodologies for Metabolomics: Experimental Strategies and Techniques, Lutz N; Sweedler JV; Weevers RA, Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Misawa T; Wei F; Kikuchi J (2016). "Application of Two-Dimensional Nuclear Magnetic Resonance for Signal Enhancement by Spectral Integration Using a Large Data Set of Metabolic Mixtures." Anal Chem 88(12): 6130–6134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Nagana Gowda GA; Raftery D (2017). "Recent Advances in NMR-Based Metabolomics." Anal Chem 89(1): 490–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Fan TWM; Lane AN (2011). "NMR-based stable isotope resolved metabolomics in systems biochemistry." Journal of biomolecular NMR 49(3-4): 267–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Lane AN; Arumugam S; Lorkiewicz PK; Higashi RM; Laulhe S; Nantz MH; Moseley HN; Fan TW (2015). "Chemoselective detection and discrimination of carbonyl-containing compounds in metabolite mixtures by 1H-detected 15N nuclear magnetic resonance." Magn Reson Chem 53(5): 337–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Ye T; Mo H; Shanaiah N; Gowda GA; Zhang S; Raftery D (2009). "Chemoselective 15N tag for sensitive and high-resolution nuclear magnetic resonance profiling of the carboxyl-containing metabolome." Anal Chem 81(12): 4882–4888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Carlson EE; Cravatt BF (2007). "Chemoselective probes for metabolite enrichment and profiling." Nature methods 4(5): 429–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Fan TW-M (1996). "Metabolite profiling by one- and two-dimensional NMR analysis of complex mixtures." Progress in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy 28: 161–219. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Fan TW-M; Lane AN (2008). "Structure-based profiling of Metabolites and Isotopomers by NMR." Progress in NMR Spectroscopy 52: 69–117. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Guennec AL; Giraudeau P; Caldarelli S (2014). "Evaluation of fast 2D NMR for metabolomics." Anal Chem 86(12): 5946–5954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Lane AN; Arumugam S; Lorkiewicz PK; Higashi RM; Laulhé S; Nantz MH; Moseley HNB; Fan TWM (2015). "Chemoselective detection and discrimination of carbonyl-containing compounds in metabolite mixtures by 1H-detected 15N nuclear magnetic resonance." Magnetic Resonance in Chemistry 53: 337–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Szeto J; Lemoine R; Nguyen R; Olson LL; Tanga MJ (2017). "Synthesis of [(15) N]-Cholamine Bromide Hydrobromide." Journal of labelled compounds & radiopharmaceuticals 61, 391–394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Fan TW; Lane AN; Higashi RM; Yan J (2011). "Stable isotope resolved metabolomics of lung cancer in a SCID mouse model." Metabolomics 7: 257–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Sun RC; Fan TW; Deng P; Higashi RM; Lane AN; Le AT; Scott TL; Sun Q; Warmoes MO; Yang Y (2017). "Noninvasive liquid diet delivery of stable isotopes into mouse models for deep metabolic network tracing." Nat Commun 8(1): 1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Rydergren S Chemical Modifications of Hyaluronan using DMTMM-Activated Amidation. Independent thesis Advanced level, Uppsala Universitet, Uppsala, Sweden, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- (28).Kay LE; Ikura M; Tschudin R; Bax A (2011). "Three-dimensional triple-resonance NMR Spectroscopy of isotopically enriched proteins. 1990." J Magn Reson 213(2): 423–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Lane AN; Fan TW-M (2007). "Quantification and identification of isotopomer distributions of metabolites in crude cell extracts using 1H TOCSY." Metabolomics 3(2): 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Heikkinen S; Permi P; Kilpeläinen I (2001). "Methods for the Measurement of 1JNCa and 2JNCa from a Simplified 2D 13Ca-Coupled 15N SE–HSQC Spectrum." J.Magnetic Resonance 148: 53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Niu C; Bertrand RD; Shindo H; Cohen JS (1979). "Cross-peptide bond 13C--15N coupling constants by 13C and J cross-polarization 15N NMR." Journal of biochemical and biophysical methods 1(3): 135–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Coxon B (2005). "Deuterium isotope effects in carbohydrates revisited. Cryoprobe studies of the anomerization and NH to ND deuterium isotope induced 13C NMR chemical shifts of acetamidodeoxy and aminodeoxy sugars." Carbohydrate Research 340: 1714–1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Fan T; Bandura L; Higashi R; Lane A (2005). "Metabolomics-edited transcriptomics analysis of Se anticancer action in human lung cancer cells." Metabolomics 1: 325–339 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.