Abstract

The type 1 pilin encoded by fim is present in both Escherichia coli and Salmonella natural isolates, but several lines of evidence indicate that similarities at the fim locus may be an example of independent acquisition rather than common ancestry. For example, the fim gene cluster is found at different chromosomal locations and with distinct gene orders in these closely related species. In this work we examined the fim gene cluster of Salmonella, the genes of which show high nucleotide sequence divergence from their E. coli counterparts, as well as a different G+C content and codon usage. DNA hybridization analysis revealed that, among the salmonellae, the fim gene cluster is present in all isolates of S. enterica but is absent from S. bongori. Molecular phylogenetic analyses of the fimA and fimI genes yield an estimate of phylogeny that is in satisfactory congruence with housekeeping and other virulence genes examined in this species. In contrast, phylogenetic analyses of the fimZ, fimY, and fimW genes indicate that horizontal transfer of this region has occurred more than once. There is also size variation in the fimZ, fimY, and fimW intergenic regions in the 3′ region, and these genes are absent in isolate S2983 of subspecies IIIa. Interestingly, the G+C contents of the fimZ, fimY, and fimW genes are less than 46%, which is considerably lower than those of the other six genes of the fim cluster. This study demonstrates that horizontal transmission of all or part of the same gene cluster can occur repeatedly, with the result that different regions of a single gene cluster may have different evolutionary histories.

Salmonella enterica is an important intracellular pathogen of reptiles, birds, and mammals and is increasingly important as a food-borne pathogen of humans. Salmonella requires the presence of at least 60 genes for virulence (19). Many of the virulence genes found in Salmonella are associated with pathogenicity islands, which are large chromosomal regions containing virulence genes that are acquired by horizontal DNA transfer and recombination (19, 37). Analysis of the acquisition and evolution of virulence factors is essential to determine the significance of each factor in the disease process and to understand the emergence of isolates with new disease and host specificities.

The population genetic structure of the salmonellae has been well established by DNA hybridization analysis, multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, and nucleotide sequence data analysis (6–8, 15, 30, 44, 50). The genus Salmonella consists of two species: S. bongori (formerly subspecies V) and S. enterica, which is further subdivided into seven subspecies designated I, II, IIIa, IIIb, IV, VI, and VII (6, 7, 32, 44). S. bongori is the most divergent lineage of Salmonella, and, along with most of the subspecies of S. enterica, it is recovered mainly from cold-blooded animals. There are over 2,300 serovars within the genus Salmonella, but 99% of human-pathogenic serovars belong to S. enterica subspecies I (42). A population genetic framework can be utilized to analyze the history of important traits such as disease factors and the role they play in host expansion and adaptation.

Pilin adhesins are important virulence determinants that are essential colonization factors and usually have antigenic properties. Present in most pathogenic bacterial isolates, fimbrial adhesins facilitate the binding of bacteria to eukaryotic cells, which is the first step in the pathogenic process (20, 37, 41). Salmonella produces at least nine fimbrial types (3, 13), of which those encoded in the fim and agf gene clusters are present in both Salmonella and Escherichia coli (1, 11, 15, 17, 23). In the two species S. enterica and E. coli, the type 1 pilin encoded by fim mediates mannose-sensitive hemagglutination and plays a key role in pathogenesis and enterobacterial communicability (2, 5, 16, 39). In E. coli K-12, the fim operon is located at 98 min (48), whereas in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, the fim operon is located at 14 min (12, 32, 46). The organization of the fim genes also differs between the species (Fig. 1). These observations suggest that the fim gene cluster may have been independently acquired in E. coli and S. enterica.

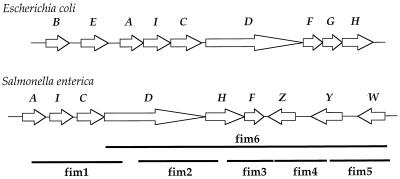

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the organization of the fim type 1 pilin gene clusters from E. coli K-12 and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium. Each gene is shown as an open arrow, scaled to size. The black bars indicate the positions of the probes (fim1 to fim6) used in DNA hybridization analysis.

We determined the nucleotide sequence similarity, the G+C content, and the codon adaptation index (CAI) (51) of each gene of fim from both Salmonella and E. coli. The fim nucleotide sequence is highly divergent between these closely related species, and there are markedly different G+C contents and CAIs. These results also suggest that fim was independently acquired in the two species. To determine a possible origin of the fim cluster, isolates from a number of enteric genera were examined. Three isolates of Citrobacter and Shigella gave a strong positive hybridization signal with a DNA probe covering much of the fim region (fim6). To further investigate the history of the fim region, we carried out a more detailed analysis of three fim genes among natural isolates of Salmonella. We found that the fim gene cluster varies in length within and among subspecies of S. enterica and that the fim region appears to be absent in isolates of S. bongori. Next, we sequenced the fimA and fimI genes from the 5′ region and the fimZ gene from the 3′ region of the gene cluster from diverse Salmonella isolates. Molecular phylogenetic analysis indicates that the 5′ region of the fim gene cluster has been evolving at a rate similar to those of other chromosomal genes in Salmonella. However, comparative sequence analysis of the fimZ gene from the 3′ region of the gene cluster suggests multiple episodes of horizontal DNA transfer among Salmonella isolates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Salmonella reference collection C (SARC) was examined for the presence of the fim locus (7). SARC contains 80 strains representing S. bongori (13 isolates) and all seven subspecies of S. enterica, designated I (11 isolates), II (14 isolates), IIIa (4 isolates), IIIb (4 isolates), IV (21 isolates), VI (9 isolates), and VII (4 isolates). A subsample of 16 strains of SARC that includes two representatives of each of the eight lineages was selected for PCR analysis and nucleotide sequencing. In addition, isolates of several other genera were examined for the presence of fim by DNA hybridization analysis (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains

| Species | Strain(s) | No. of isolates | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shigella boydii | ATCC 8700 | 1 | Type strain |

| Shigella flexnerii | ATCC 29903 | 1 | Type strain |

| Shigella sonnei | ATCC 29930 | 1 | Type strain |

| Escherichia coli | ECOR collection | 8 | Natural isolates |

| Escherichia blattae | ATCC 29907 | 1 | Natural isolate |

| Escherichia fergusonii | ATCC 35469 | 1 | Clinical isolate |

| Escherichia hermanii | ATCC 33650 | 1 | Clinical isolate |

| Citrobacter freundii | ATCC 33821 | 1 | Clinical isolate |

| Citrobacter diversus | Unknown | 1 | Unknown |

| Citrobacter amalonaticus | ATCC 25407 | 1 | Clinical isolate |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | ATCC 13883 | 1 | Natural isolate |

| Klebsiella oxytoca | ATCC 13182 | 1 | Clinical isolate |

| Klebsiella planticola | ATCC 33531 | 1 | Natural isolate |

| Yersina enterocolitica | ATCC 23715 | 1 | Clinical isolate |

| Salmonella enterica | SARC collection | 67 | Natural isolates |

| Salmonella bongori | SARC collection | 13 | Natural isolates |

PCR amplification.

Primers for PCR amplification and DNA sequencing were designed from the published sequence of the fim gene cluster from S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (accession no. L19338). PCR products were purified by using the Qiaquick PCR purification kit. Six pairs of primers were used to amplify six regions along the fim cluster ranging in size from 911 to 6,386 bp (Table 2 and Fig. 1).

TABLE 2.

PCR primers used to amplify probes for the fim cluster of Salmonella

| Primera | Nucleotide sequence | Positionb | Product size (bp) | Probe |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| fimA1 | 5′-GCCGACAGGATGCCGAAACC-3′ | 117 | 2,970 | fim1 |

| fimD2 | 5′-CGTGAGAAGAACAATAAAGC-3′ | 3966 | ||

| fimD3 | 5′-AGGGCGTAGCAGTAGCAA-3′ | 4929 | 1,013 | fim2 |

| fimH2 | 5′-GCGCCCAGAAGGTAGTCA-3′ | 5924 | ||

| fimH1 | 5′-TCGCTGGCGTATCTTATC-3′ | 5962 | 1,100 | fim3 |

| fimF2 | 5′-AGCATTGCCGTTGTTGTC-3′ | 7044 | ||

| fimZ1 | 5′-GTGAAGGCCAAGTTTAGA-3′ | 7251 | 1,500 | fim4 |

| fimY2 | 5′-ACACAGTTTATCCGTATG-3′ | 8733 | ||

| fimY1 | 5′-CTTAAACGGCGGTGTCTT-3′ | 9121 | 1,064 | fim5 |

| fimW2 | 5′-GCGTCTGGCGAATCAATG-3′ | 10167 | ||

| fimD1 | 5′-AATAACGGAGCCTGGAACTA-3′ | 3637 | 6,386 | fim6 |

| fimW4 | 5′-TAAATGCGATAAAGAAAAGC-3′ | 10003 |

Odd numbers indicate forward primers; even numbers indicate reverse primers.

Nucleotide positions of the first and last nucleotides in the amplified fragment, with numbering from the 5′ end of the gene cluster.

DNA hybridization.

The six fim fragments produced by PCR amplification (Table 2) were prepared for use as nonradioactive probes by labeling with fluorescein-conjugated nucleotides and, after hybridization, were detected with the ECL system (Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.). Total genomic DNA from each bacterial isolate was extracted by using the G-nome DNA isolation kit from Bio101 (Vista, Calif.). DNA was digested with EcoRI, and the fragments were separated by electrophoresis in 0.6% agarose. The fragments were transferred to nylon membranes for hybridization at 60°C (high stringency) and 55°C (low stringency).

Nucleotide sequencing.

A total of 14 isolates from SARC were examined for nucleotide variation at three loci, fimA, fimI, and fimZ. In addition to the sample of 14 SARC strains, 3 host-adapted serovars of subspecies I were examined for nucleotide sequence polymorphism at the fimA and fimI loci; these were strains S1208 (serovar Enteritidis), S1280 (serovar Dublin), and S4993 (serovar Gallinarum). DNA sequencing of PCR-amplified DNA was performed with an Applied Biosystems 370A DNA sequencer according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Both dye-terminator and dye-primer chemistries were used.

Statistical analysis.

DNA sequence data were assembled and edited with Sequencer programs. Phylogenetic analysis was performed with the programs Molecular Evolutionary Genetic Analysis (version 1.0) (24) and Molecular Evolutionary Analysis (Etsuko Moriyama, Yale University). Statistical tests for recombination based on polymorphic synonymous sites were performed by the methods of Stephens (52) and Sawyer (49) for the detection of nonrandom clustering of polymorphic sites.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequences of the fim genes described in this paper have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession no. AF083899 to AF083912.

RESULTS

Gene organization.

The fim operon includes nine open reading frames: fimA, fimI, fimC, fimD, fimH, fimF, fimZ, fimY, and fimW. The fimZ, fimY, and fimW genes are transcribed in the direction opposite from that of the other genes in the cluster (Fig. 1); these genes also have unusually large intergenic regions relative to the other genes in the fim cluster and also relative to intergenic regions in enteric bacteria. In S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, the fimZ-fimY intergenic region is 604 bp and the fimY-fimW intergenic region is 492 bp. PCR analysis indicated size differences in the fimY-fimW intergenic region among subspecies of Salmonella. Isolates of subspecies II, IIIa, and IIIb gave a PCR product from the fimY-fimW intergenic region that was approximately 500 bp larger than that obtained from isolates of subspecies I. One isolate of subspecies VI (S2995) gave a PCR product approximately 1,500 bp larger than that expected, whereas isolate S3057 gave a product 200 bp smaller, relative to other isolates of subspecies I. Furthermore, the fimZ, fimY, and fimW genes have G+C contents of 46, 41, and 42%, respectively, which are low relative to the overall 50 to 52% G+C content of the Salmonella chromosome (Table 3). The other six fim genes (fimA, fimI, fimC, fimD, fimH, and fimF) have G+C contents in the range of 50 to 55%.

TABLE 3.

Nucleotide sequence identities, G+C contents, and CAIs of the fim genes in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium and E. coli K-12

| Gene | % Nucleotide sequence identitya | % G+C

|

CAI

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. enterica | E. coli | S. enterica | E. coli | ||

| fimB | NAb | NA | 43 | NA | 0.19 |

| fimE | NA | NA | 47 | NA | 0.23 |

| fimA | 66 | 54 | 51 | 0.36 | 0.40 |

| fimI | NA | 53 | 49 | 0.21 | 0.17 |

| fimC | 65 | 50 | 44 | 0.26 | 0.21 |

| fimD | 69 | 55 | 49 | 0.26 | 0.23 |

| fimH/fimF | 66 | 52 | 49 | 0.25 | 0.23 |

| fimF/fimG | 65 | 55 | 52 | 0.30 | 0.23 |

| fimZ/fimH | NA | 46 | 50 | 0.20 | 0.24 |

| fimY | NA | 41 | NA | 0.20 | NA |

| fimW | NA | 42 | NA | 0.25 | NA |

Comparison between Salmonella and E. coli fim genes.

NA, not applicable.

DNA hybridization.

Six DNA probes (denoted fim1, fim2, fim3, fim4, fim5, and fim6) were used to determine the presence of the fim operon among natural isolates of Salmonella (Table 2 and Fig. 1). The probes fim1, fim2, and fim3 gave a strong positive hybridization signal with 14 isolates of S. enterica. However, no signal was obtained with the S. bongori isolates examined (Table 4). Probes fim4 and fim5 gave a positive hybridization signal with only 13 of the 14 S. enterica isolates; the exception, subspecies IIIa isolate S2983, gave no detectable hybridization signal, and we concluded that the fimZ, fimY, and fimW genes are probably absent from this isolate. The probe fim6, which encompasses fimD through fimW (a 6,386-bp segment of the cluster), was used to probe an additional 11 S. bongori isolates; 3 of these strains gave a weak positive hybridization signal. Among isolates of several other genera, the fim6 probe hybridized with the three Shigella and Citrobacter isolates (Table 1).

TABLE 4.

Presence of the fim genes among Salmonella isolates

| Species or subspecies | Isolate | Hybridizationa with DNA probe:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fim1 | fim2 | fim3 | fim4 | fim5 | fim6 | ||

| S. enterica subspecies | |||||||

| I | S3333 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| S4194 | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| II | S2985 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| S2993 | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| VI | S2995 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| S3057 | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| IIIb | S2978 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| S2979 | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| IV | S3015 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| S3027 | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| VII | S3013 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| S3014 | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| IIIa | S2980 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| S2983 | + | + | + | + | − | − | |

| S. bongori | S3041 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| S3044 | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

+, positive hybridization signal; −, indicates no hybridization signal.

Nucleotide sequence polymorphisms.

Among the fim genes, nucleotide sequence divergence between E. coli and Salmonella was on average greater than 35% (Table 3). For each of 14 SARC strains and 3 additional isolates of subspecies I, the sequence of a 675-bp region encompassing partial sequences of fimA and fimI was determined. We found some size variation in the intergenic region of the fimA and fimI genes with respect to the reference sequence; all strains had a 2- or 3-bp deletion, except for strain S4194, which matched the reference sequence. Strain S3333 also had a 3-bp deletion in the 3′ coding sequence of fimA. Among the 17 Salmonella isolates examined in this region, there were a total of 150 polymorphic sites: 92 polymorphic sites were within the 486-bp region of the fimA gene, including 22 amino acid replacements, and 23 polymorphic sites were within the 114-bp region of fimI sequenced, including 15 amino acid replacements. The remaining 35 polymorphic sites were located in the 75-bp fimA-fimI intergenic region (Table 5). Comparison of the nucleotide sequence of the fimI gene with that from the published sequence of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (accession no. L19338) implied that the start codon should probably be placed 13 codons upstream of the annotated start position, since the annotated start methionine has an amino acid replacement in five isolates. Nucleotide sequence analysis of a 504-bp region of the fimZ gene among 10 SARC isolates gave 91 polymorphic sites, including 25 amino acid replacements (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Nucleotide sequence polymorphism among the fimA, fimI, and fimZ genes from natural isolates of S. enterica

| Region | No. of bp (% of region) | No. of polymorphic:

|

kS (mean ± SD) | kN (mean ± SD) | kN/kS ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleotides | Amino acids | |||||

| fimA | 486 (87) | 92 | 22 | 0.24 ± 0.03 | 0.02 ± 0.005 | 0.08 |

| Intergenic | 75 (100) | 35 | NAa | NA | NA | NA |

| fimI | 114 (24) | 23 | 15 | 0.0006 ± 0.0002 | 0.0007 ± 0.0003 | 1.2 |

| fimZ | 504 (95) | 91 | 25 | 0.26 ± 0.03 | 0.03 ± 0.005 | 0.11 |

NA, not applicable.

Synonymous and nonsynonymous substitutions.

For fimA and fimI we estimated the number of synonymous (silent) substitutions per 100 synonymous sites (kS) and the number of nonsynonymous (amino acid replacement) substitutions per 100 nonsynonymous sites (kN) (33, 34). Overall there appears to be a strong selective constraint against amino acid replacement at the fimA locus, given that the nonsynonymous rate kN (0.019 ± 0.005) is 10-fold smaller than the synonymous rate kS (0.241 ± 0.03) (Table 5). However, at the fimI locus, kN = 0.07 ± 0.03 whereas kS = 0.06 ± 0.02, which suggests that there is less constraint for amino acid replacement in this region or perhaps some form of positive selection. The fimZ gene showed levels of synonymous and nonsynonymous site variation similar to those of the fimA gene (Table 5).

Spatial distribution of polymorphic sites.

Figures 2 and 3 show the distribution of polymorphic sites along the fimA, fimI, and fimZ genes. To identify nonrandom clustering of polymorphic sites, which can be indicative of intragenic recombination, we examined the distribution of polymorphic sites relative to the phylogenetic partitions they support, using the statistical method developed by Stephens (52). If there is no intragenic recombination, then the polymorphic sites supporting a particular phylogenetic partition are expected to be randomly distributed along a sequence. For the fimAI region, the Stephens test identified 45 phylogenetic partitions, 40 of which were not statistically significant. Analyses of the remaining five independent phylogenetic partitions with significant P values (P ≤ 0.05, corrected for multiple tests as described in reference 52) are shown in Table 6. All five partitions had significantly long segments of monomorphic sites, but none showed statistically significant nonrandom clustering of polymorphic sites.

FIG. 2.

Distribution of polymorphic nucleotide sites in the fimA-fimI coding region among 14 SARC isolates of S. enterica. Numbers at the left are strain designations; those across the top are nucleotide positions along the gene. Dots indicate nucleotide identity. Only variable positions are shown.

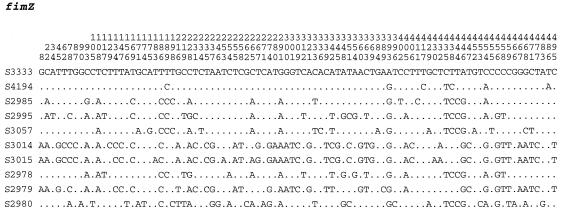

FIG. 3.

Distribution of polymorphic nucleotide sites in the fimZ gene among 10 SARC isolates of S. enterica. Numbers at the left are strain designations; those across the top are nucleotide positions along the gene. Dots indicate nucleotide identity. Only variable positions are shown.

TABLE 6.

Statistically significant partitions identified by Stephens test for nonrandom clustering of polymorphic sites in the fimA, fimI, and fimZ genesa

| Partition | Isolates compared | s | d0 | P(d < d0) | g0 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fimAI | ||||||

| 1 | Subspecies IV and VII versus others | 24 | 660 | 0.87 | 95 | 0.030 |

| 2 | Subspecies IIIb versus others | 13 | 612 | 0.63 | 193 | 0.014 |

| 3 | Subspecies I versus others | 7 | 371 | 0.10 | 227 | 0.008 |

| 4 | S2993 and subspecies IIIa versus others | 17 | 618 | 0.55 | 169 | 0.007 |

| 5 | S2985 versus others | 3 | 206 | 0.22 | 173 | 0.005 |

| fimZ | ||||||

| 1 | S3014, S3015, and S2979 versus others | 17 | 487 | 0.87 | 89 | 0.045 |

| 2 | S3014 and S3015 versus others | 7 | 370 | 0.40 | 180 | 0.034 |

| 3 | S2980 versus others | 11 | 393 | 0.26 | 125 | 0.030 |

| 4 | S2995 and S2978 versus others | 3 | 237 | 0.45 | 195 | 0.004 |

| 5 | S3015 versus others | 3 | 247 | 0.48 | 177 | 0.004 |

| 6 | S3014, S3015, S2979, and S2980 versus others | 3 | 222 | 0.40 | 185 | 0.005 |

Symbols: s, number of polymorphic sites; d0, observed distance between the two terminal polymorphic sites; g0, length of longest segment with consecutive nonpolymorphic sites; P, probability that at least one of s − 1 random, independently observed segments is at least as long as g0.

Analysis of the distribution of polymorphic sites among the fimZ gene sequences identified 36 distinctive phylogenetic partitions, 30 of which were not statistically significant. Six partitions had significantly long segments of monomorphic sites, but none had statistically significant clustering of polymorphic sites (Table 6).

Phylogenetic analysis.

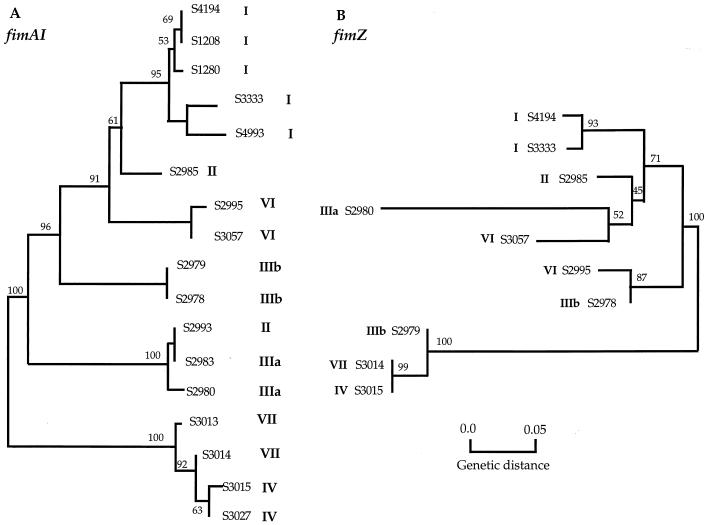

Neighbor-joining trees were constructed for each gene (48). The gene trees presented in Fig. 4 are based on synonymous sites only, and the bootstrap values from 1,000 resampled trees are indicated by the numbers along the branches. Consistent with the analysis of polymorphic clusters, an evolutionary tree based on the fimAI sequences gave a topology generally similar to that of trees based on housekeeping and other virulence genes (Fig. 4A). The fimAI sequences of strains of the same subspecies are generally much more similar to each other than they are to the sequences of other subspecies, with the single exception of strain S2993, in which the fimAI sequence has a greater resemblance to the fimAI sequence of subspecies IIIa. The sequences from subspecies IV and VII are the most divergent. Nucleotide sequences from five S. enterica subspecies I host-adapted serovars show very similar patterns of nucleotide and amino acid polymorphism, with serovars Choleraesuis and Dublin clustering as a group and serovars Gallinarum, Paratyphi, and Typhi clustering as a group (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

Evolutionary relationships based on synonymous site variation in the fimA, fimI, and fimZ genes. The neighbor-joining method was used to construct the trees (48), using the Jukes-Cantor correction for multiple hits (21). The SARC Salmonella strains are indicated by numbers, and the subspecies are indicated by roman numerals. Bootstrap values based on 1,000 computer-generated trees are indicated at the nodes. The genetic distance is the Jukes-Cantor distance (21).

Analysis of the phylogenetic tree for the fimZ gene presented in Fig. 4B shows that it is not congruent with the tree based on fimAI nucleotide sequence data or with gene trees based on nucleotide sequence data of several other chromosomal genes (6, 7, 8, 31, 50). The differences between the gene trees are consistent with the phylogenetic partitions identified by the Stephens test (52), suggesting horizontal transfer and recombination of the fimZ region among isolates. For example, strain S2980 (subspecies IIIa) is placed with isolate S3057 of subspecies VI; similarly, isolate S2995 of subspecies VI clusters with isolate S2978 of subspecies IIIb, and isolate S2979 of subspecies IIIb clusters with subspecies VII and IV.

DISCUSSION

The acquisition and evolution of specific DNA segments in individual lineages constitute one probable mechanism of strain diversification and host expansion in Salmonella, various strains of which can cause a number of diseases in a variety of species. It has been proposed that the E. coli and Salmonella genomes contain up to 15% horizontally transferred DNA (27, 38, 54, 55) and that some of the exogenous DNA in these species includes genes encoding phenotypes that distinguish the two species, such as genes that provide novel pili, surface polysaccharides and proteins, and the biosynthesis and/or degradation of nutrients that confer the ability to explore and invade new ecological niches (25, 28). Evidence for the horizontal transfer of DNA into bacterial species has been adduced from analysis of the phylogenetic relationships, the G+C contents, and the codon usage patterns of the chromosomal regions of interest. The base composition is relatively uniform over most of the bacterial chromosome, and it also correlated with phylogeny because the G+C contents of closely related lineages tend to be quite similar. As a consequence, chromosomal regions or genes having an anomalous G+C content or codon usage are inferred to have been acquired recently by horizontal transfer from a distantly related species (26, 38). When phylogenetic trees based on different chromosomal regions give contradictory branch topologies, this may also be evidence of horizontal transfer of DNA.

The type 1 pilin operon fim in S. enterica and E. coli mediates mannose-sensitive hemagglutination (40); despite the otherwise similar genetic maps of these closely related species, the fim operon is found at 98 min on the E. coli chromosome and at 14 min on the S. enterica chromosome (12). The gene order within the fim gene cluster also differs between the two species (Fig. 1). These differences may reflect independent acquisition of this region in the two species. On the other hand, a chromosomal inversion could also account for the different locations of the fim cluster (45). Our analysis of nucleotide sequence divergence, G+C content, and CAI favors the hypothesis that the fim gene cluster was acquired independently in E. coli and Salmonella (Table 3). There is considerable sequence divergence at the fim locus between the two species, with less than 65% identity at the nucleotide sequence level and less than 70% identity at the amino acid sequence level. Furthermore, the fim genes in Salmonella have higher G+C contents and CAIs than the E. coli fim genes (Table 3). By contrast, nucleotide sequence comparison of E. coli and Salmonella genes typically shows greater than 85% nucleotide identity.

Comparative nucleotide sequence analysis of the fimA and fimI genes from Salmonella natural isolates indicates that this region has been evolving at a rate similar to those of other housekeeping and virulence genes of Salmonella. The nucleotide divergence of the region in different isolates suggests that the fim gene cluster was present in the most recent common ancestor of all S. enterica. Our previous analysis (10) of the fimA gene from E. coli showed that the fimA gene was hypervariable among natural isolates. An accelerated divergence in different regions of the fimA gene suggested some form of positive selection at this locus in E. coli, with the sequence hypervariability perhaps playing a role in antigenic diversity (10). The different fimA variability in the two species may reflect differences in selection pressure on the type 1 pilin.

The phylogenetic relationships based on the fimA and fimI loci for Salmonella subspecies IV and VII are similar to those for other virulence loci, which indicates shared ancestry for the virulence genes (6–8, 31, 50). With respect to the virulence gene clusters, the isolates of S. enterica subspecies IV and VII are poorly differentiated from each other, whereas they are quite distinctive with respect to the nucleotide sequences of housekeeping genes or multilocus enzyme electrophoresis. The discrepancy strongly suggests that subspecies IV and VII are mosaic in structure, with large regions of the chromosome having different evolutionary histories.

Molecular phylogenetic analysis of the fimZ gene, present in the 3′ region of the gene cluster, unexpectedly yielded an estimated gene tree that is not congruent with the phylogenetic relationships based on the fimA and fimI genes (Fig. 4A). The estimate is also incongruent with any other chromosomal region for which nucleotide sequence data are available (Fig. 5). The inconsistency of the branching pattern of the tree strongly suggests horizontal transfer and recombination of the fimZ region among isolates of Salmonella. The clustering of isolates of subspecies IIIa and VI, of IIIb and VI, and of IIIb and VII indicates the anomalous similarities in fimZ among the subspecies (Fig. 4B). Horizontal transfer and recombination of the entire fimZ region are demonstrated by comparative nucleotide sequence analysis of the 5′ and 3′ halves of fimZ, which yield similar phylogenetic trees. The horizontal transfer, the large intergenic regions, and the low G+C content of genes in this region indicate that the fimZ, fimY, and fimW genes have a very different evolutionary history from genes in the rest of the operon. They may even have been acquired subsequent to the acquisition of fimAIDEHF genes. In any case, horizontal DNA transfer and recombination appear to have played an important role in the evolutionary history of this gene cluster, and the fim operon affords insight into how gene clusters may have been formed during the evolution of a species with different functional regions obtained from diverse sources. The function of the fimZ, fimY, and fimW genes is unknown, but they are thought to be involved in regulation.

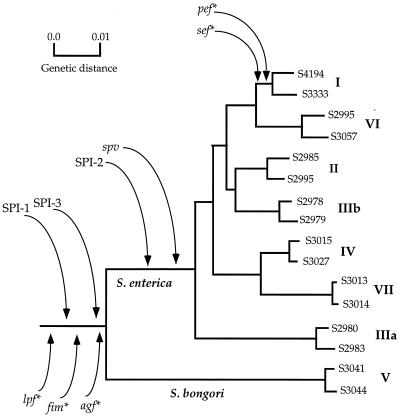

FIG. 5.

Proposed evolutionary history of horizontal transmission of certain pathogenic determinants into Salmonella. Phylogenetic relationships of the Salmonella subspecies are based on nucleotide sequence data from five housekeeping genes (7). The proposed times of horizontal transmission (arrows) are consistent with the presence in all lineages of Salmonella of the pathogenicity islands SPI-1 (8, 31) and SPI-2 (37), as well as of the pilin gene clusters agf, lpf, and fim (reference 1 and this study). The proposed times for SPI-3 (4) and spv (9) are consistent with their presence in all lineages of Salmonella except S. bongori. The proposed times for the pef and sef (1) gene clusters are consistent with their presence only in isolates of S. enterica subspecies I. The pilin gene clusters are indicated by asterisks.

Examination of isolates representing several related enteric genera for the presence of the fim gene cluster can provide clues to the evolutionary history of the fim region. The presence of the region of interest in all related lineages suggests its presence in the most recent common ancestor, whereas the absence from related lineages is most parsimoniously attributed to horizontal transfer rather than to independent deletions in several lineages. DNA hybridization analysis showed that the fim gene cluster was present in three isolates of Shigella and three species of Citrobacter. The presence of sequences related to fim in several isolates of Shigella is not surprising, since multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, DNA hybridization, and DNA sequence analysis have all demonstrated that Shigella and E. coli are conspecific (35, 43). Shigella is therefore generally recognized as a human-adapted pathogenic variety of E. coli, which is itself a close relative of Salmonella (22, 53). In contrast, Citrobacter is considered a heterogeneous assemblage of strains (29) that are only distantly related to E. coli and Salmonella (29). The presence of fim in all three divergent Citrobacter species suggests that fim may be ancestral to this group, but additional studies will be necessary to test this hypothesis.

S. enterica and E. coli diverged from a common ancestor approximately 100 million years ago (14, 36). E. coli evolved as a commensal and opportunistic pathogen of mammals and birds, whereas the lineage ancestral to Salmonella remained associated with reptiles, the primary host of S. bongori and S. enterica subspecies IIIa, IV, and VII (the subspecies that are monophasic in flagellar expression). The ability to colonize host cells via acquisition of host colonization factors (pilin and flagella), as well as the acquisition of mechanisms to avoid host defense systems, may have been important factors in the expansion of the ecological niche of Salmonella to warm-blooded vertebrates. However, Salmonella is an intracellular pathogen, rather than a commensal like E. coli, and this niche requires chromosomal regions necessary for host cell invasion and survival. Consistent with this evolutionary scenario are the observations regarding the ancestry of the Salmonella pathogenic islands (SPIs) (Fig. 5). Three SPIs have been identified to date, and we and others have previously shown that SPI-1 (the inv/spa locus), SPI-2 (the spi locus), and SPI-3 (the selC locus) are present in all lineages of S. enterica and have evolved in a pattern and at an average rate similar to those of the average housekeeping gene (4, 6–8, 18, 31, 37). Interestingly, the spv region of the Salmonella virulence plasmid, which is essential in nontyphoid serovars for causing systemic infection, is present in most Salmonella lineages (9). The pathogenic lifestyle is therefore assumed to be an ancient phenotype in Salmonella. The inferences are that the chromosomal regions containing these gene clusters were present in the most recent common ancestor of all contemporary lineages of the salmonellae (Fig. 5) and that these virulence regions allowed the salmonellae to invade niches that remained inaccessible to its closest relatives.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bäumler A J, Gilde A J, Tsolis R M, van der Velden A W M, Ahmer B M M, Heffron F. Contribution of horizontal gene transfer and deletion events to development of distinctive patterns of fimbrial operons during evolution of Salmonella serotypes. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:317–322. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.2.317-322.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bäumler A J, Tsolis R M, Heffron F. Fimbrial adhesins of Salmonella typhimurium. Role in bacterial interaction with epithelial cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1997;412:149–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bäumler A J, Heffron F. Identification and sequence analysis of lpfABCDE, a putative fimbrial operon of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2087–2097. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.8.2087-2097.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanc-Potard A-B, Groisman E A. The Salmonella selC locus contains a pathogenicity island mediating intramacrophage survival. EMBO J. 1997;16:5376–5385. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.17.5376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bloch C A, Stocker B A, Orndorff P E. A key role for type 1 pili in enterobacterial communicability. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:697–701. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyd E F, Nelson K, Whittam T S, Selander R K. Molecular genetic basis of allelic polymorphism in malate dehydrogenase (mdh) in natural isolates of Escherichia coli and Salmonella. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1280–1284. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.4.1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyd E F, Wang F-S, Whittam T S, Selander R K. Molecular genetic relationships of the salmonellae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:804–808. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.3.804-808.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyd E F, Li J, Ochman H, Selander R K. Comparative genetics of the inv/spa invasion gene complex of Salmonella enterica. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1985–1991. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.6.1985-1991.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyd E F, Hartl D L. Salmonella virulence plasmid: modular acquisition of the spv virulence region by an F plasmid in S. enterica subspecies I and insertion into the chromosome of subspecies II, IIIa, IV, and VII isolates. Genetics. 1998;149:1183–1190. doi: 10.1093/genetics/149.3.1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyd E F, Hartl D L. Diversifying selection governs sequence polymorphism in the major adhesin proteins, FimA, PapA, and SfaA of Escherichia coli. J Mol Evol. 1998;47:258–267. doi: 10.1007/pl00006383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clegg S, Swenson D L. Fimbriae adhesion: genetics, biogenesis, and vaccines. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1994. pp. 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collinson S K, Liu S-L, Clouthier S C, Banser P A, Doran J L, Sanderson K E, Kay W W. The location of four fimbrin-encoding genes, agfA, fimA, sefA and sefD, on the Salmonella enteriditis and/or S. typhimurium XbaI-BlnI genomic restriction maps. Gene. 1996;169:75–80. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00763-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crosa J H, Brenner D J, Ewing W H, Falkow S. Molecular relationships among the salmonellae. J Bacteriol. 1973;115:307–315. doi: 10.1128/jb.115.1.307-315.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doolittle R F, Feng D F, Tsang S, Cho G, Little E. Determining the divergence times of the major kingdoms of living organisms with a protein clock. Science. 1996;271:470–477. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5248.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duguid J P, Campbell I. Antigens of the type-1 fimbriae of salmonellae and other enterobacteria. J Med Microbiol. 1969;4:535–553. doi: 10.1099/00222615-2-4-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ewen S W, Naughton P J, Grant G, Sojka M, Allen-Vercoe E, Bardocz S, Thorns C J, Pusztai A. Salmonella enterica var Typhimurium and Salmonella enterica var. Enteriditis express type 1 fimbriae in the rat in vivo. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1997;18:185–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1997.tb01044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feutrier J, Kay W W, Trust T J. Purification and characterization of fimbriae from Salmonella enteritidis. J Bacteriol. 1986;168:221–227. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.1.221-227.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Groisman E A, Ochman H. Pathogenicity islands: bacterial evolution in quantum leaps. Cell. 1996;87:791–794. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81985-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Groisman E A, Ochman H. How Salmonella became a pathogen. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:343–349. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01099-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hacker J. Role of fimbrial adhesins in the pathogenesis of Escherichia coli infections. Can J Microbiol. 1992;38:720–727. doi: 10.1139/m92-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jukes T H, Cantor C R. Evolution of protein molecules. In: Munro H N, editor. Mammalian protein metabolism. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1969. pp. 21–132. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karaolis D K, Lan R R, Reeves P R. Sequence variation in Shigella sonnei, a pathogenic clone of Escherichia coli, over four continents and 41 years. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:796–802. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.3.796-802.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klemm P. Fimbrial adhesions of Escherichia coli. Rev Infect Dis. 1985;73:321–340. doi: 10.1093/clinids/7.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M. Molecular evolutionary genetic analysis MEGA. University Park: Pennsylvania State University; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawrence J G. Selfish operons and speciation by gene transfer. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:355–359. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lawrence J G, Ochman H. Amelioration of bacterial genomes: rates of change and exchange. J Mol Evol. 1997;44:383–397. doi: 10.1007/pl00006158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lawrence J G, Ochman H. Molecular archaeology of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:383–397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lawrence J G, Roth J R. Selfish operons: horizontal transfer may drive the evolution of gene clusters. Genetics. 1996;143:1843–1860. doi: 10.1093/genetics/143.4.1843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lawrence J G, Hartl D L, Ochman H. Molecular considerations in the evolution of bacterial genes. J Mol Evol. 1991;33:241–250. doi: 10.1007/BF02100675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Le Minor L M, Popoff M Y, Laurent B, Hermant D. Individualisation d’une septième sous-espèce de Salmonella: S. choleraesuis subsp. indica. subsp. nov. Ann Microbiol (Paris) 1986;137B:211–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li J, Ochman H, Groisman E A, Boyd E F, Solomon F, Nelson K, Selander R K. Relationship between evolutionary rate and cellular location among the Inv/Spa invasion proteins of Salmonella enterica. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7252–7256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lockman H A, Curtiss R. Isolation and characterization of conditional adherent and nontype 1 fimbriated Salmonella typhimurium mutants. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:933–945. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nei M, Gojobori T. Simple methods for estimating the numbers of synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions. Mol Biol Evol. 1986;3:418–426. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nei M, Jin L. Variances of the average numbers of nucleotide substitutions within and between populations. Mol Biol Evol. 1989;6:290–300. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ochman H, Whittam T S, Caugant C A, Selander R K. Enzyme polymorphism and genetic population structure of Escherichia coli and Shigella. J Gen Microbiol. 1983;129:2715–2726. doi: 10.1099/00221287-129-9-2715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ochman H, Wilson A C. Evolution in bacteria: evidence for a universal substitution rate in cellular genomes. J Mol Evol. 1987;26:74–86. doi: 10.1007/BF02111283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ochman H, Groisman E A. Distribution of pathogenicity islands in Salmonella. Infect Immun. 1996;64:5410–5412. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5410-5412.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ochman H, Lawrence J G. Phylogenetics and the amelioration of bacterial genomes. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingram J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 2723–2729. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Orndorff P E, Bloch C A. The role of type 1 pili in the pathogenesis of Escherichia coli infections: a short review and some new ideas. Microb Pathog. 1990;9:75–79. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(90)90081-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ørskov I, Ørskov F. Serology of Escherichia coli fimbriae. Prog Allergy. 1983;33:80–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ørskov I, Ørskov F. Escherichia coli in extraintestinal infections. J Hyg. 1985;95:551–575. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400060678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Popoff M Y, Le Minor L. Antigenic formulas of the Salmonella serovars. 5th ed. Paris, France: WHO Collaborating Center for Reference on Salmonella, Institut Pasteur; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pupo G M, Karaolis D K R, Lan R, Reeves P R. Evolutionary relationships among pathogenic and nonpathogenic Escherichia coli strains from multilocus enzyme electrophoresis and mdh sequence studies. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2685–2692. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2685-2692.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reeves M W, Evins G M, Heiba A A, Pliikaytis B D, Farmer J J., III Clonal nature of Salmonella typhi and its genetic relatedness to other salmonellae as shown by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, and proposal of Salmonella bongori comb. nov. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:311–320. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.2.313-320.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rossolini G M, Muscas P, Chiesurin A, Satta G. fimA-folD gene linkage in Salmonella identifies a putative junctional site of chromosomal rearrangement in the enterobacterial genome. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;119:321–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sanderson K E, Hessel A, Rudd K E. Genetic map of Salmonella typhimurium, edition VIII. Microbiol Rev. 1995;592:241–303. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.2.241-303.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sanderson K E, Roth J R. Linkage map of Salmonella typhimurium, edition VII. Microbiol Rev. 1988;52:485–532. doi: 10.1128/mr.52.4.485-532.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sawyer S A. Statistical tests for detecting gene conversion. Mol Biol Evol. 1989;6:526–538. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Selander R K, Li J, Boyd E F, Wang F-S, Nelson K. DNA sequence analysis of the genetic structure of populations of Salmonella enterica and Escherichia coli. In: Priest F G, Ramos-Cormenzana A, Tindall B J, editors. Bacterial diversity and systematics. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1994. pp. 17–49. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sharp P M, Li W H. The codon adaptation index—a measure of directional synonymous codon usage bias, and its potential applications. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:1281–1295. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.3.1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stephens J C. Statistical methods of DNA sequence analysis: detection of intragenic recombination or gene conversion. Mol Biol Evol. 1985;2:539–556. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stevenson G, Neal B, Lui D, Hobbs M, Packer N H, Batley M, Redmond J W, Linquist L, Reeves P R. Structure of the O antigen of Escherichia coli K-12 and the sequence of its rfb gene cluster. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4144–4156. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.13.4144-4156.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Whittam T S, Ake S. Genetic polymorphisms and recombination in natural populations of Escherichia coli. In: Takahata N, Clark A G, editors. Mechanisms of molecular evolution. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates; 1993. pp. 223–245. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Whittam T S. Genetic variation and evolutionary processes in natural populations of Escherichia coli. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 2708–2720. [Google Scholar]